Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: information for parents

Updated 16 February 2026

Applies to England

1. Overview

This information will be useful if your baby is suspected of having congenital diaphragmatic hernia following your 20-week scan (sometimes referred to as the mid-pregnancy scan). it will help you and your health professionals to talk through the next stages of your and your baby’s care. This information should support, but not replace, discussions you have with health professionals.

Finding out there may be a problem with your baby’s development can be worrying. It is important to remember you are not alone.

We will refer you to a specialist team who will do their best to:

- provide more accurate information about your baby’s condition and treatment

- answer your questions

- help you plan the next steps

2. About congenital diaphragmatic hernia

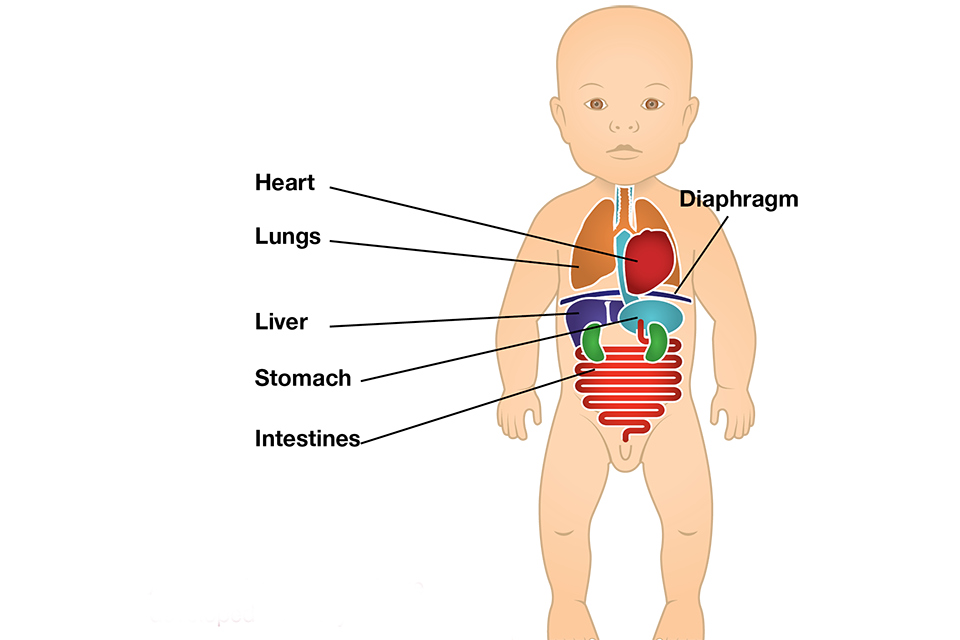

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia is a condition where the baby’s diaphragm does not form as it should. The diaphragm is a thin sheet of muscle that helps us breathe. It also keeps the heart and lungs separate from the organs in the abdomen (tummy).

An illustration of a baby with its organs in the usual places.

A baby whose organs have developed as expected

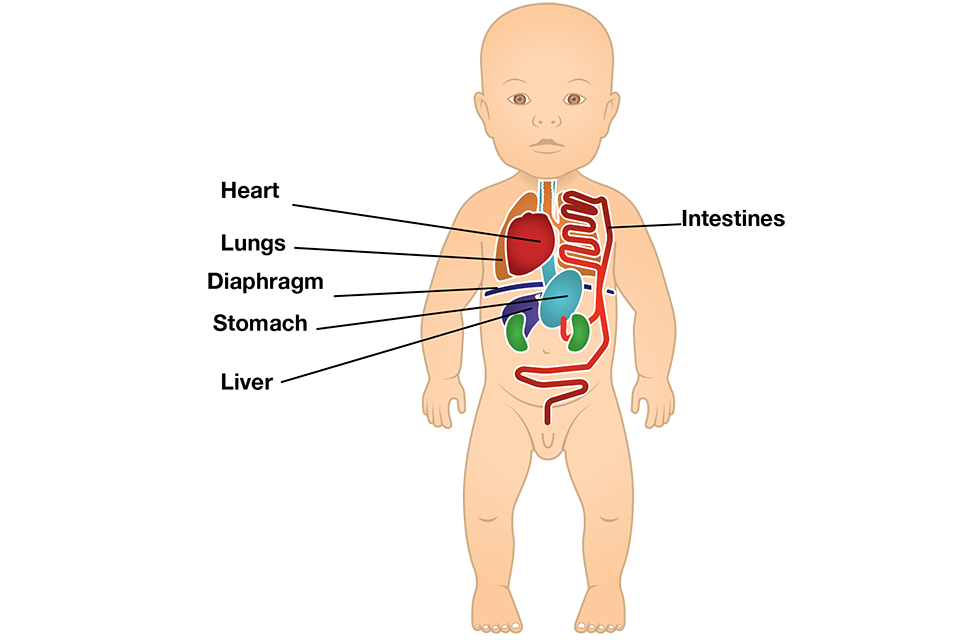

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia happens very early in the baby’s development. The lungs have less space so they cannot grow and develop properly.

In some babies with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia the organs in the abdomen, such as the stomach, bowels and liver, go through the hole in the diaphragm. This is called a hernia. These organs take up space where the lungs and heart should be, and this means the lungs do not grow as expected.

An illustration of a baby with its organs in unusual places due to a congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

A baby with congenital diaphragmatic hernia

Many babies with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia will also have a problem called pulmonary hypertension, caused by high blood pressure in the lungs. This might mean the heart cannot pump blood into the lungs. This makes it more difficult for the lungs to take in oxygen. Organs need oxygen to work. Not getting enough oxygen causes serious problems.

The baby’s lungs do not need to work in the womb because the baby gets oxygen from the mother’s bloodstream through the placenta. After birth, the baby’s lungs need to supply the body with oxygen. If the lungs are small or not developed as expected they may not work properly.

2.1 Causes

We do not know exactly what causes Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. It is not caused by something you have or have not done. It is sometimes linked to other medical conditions, like those affecting your baby’s chromosomes (genetic information) and heart. You will be able to discuss your individual circumstances with a specialist team.

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia happens in about 4 babies out of every 10,000 (0.04%).

3. How we find congenital diaphragmatic hernia

We screen for Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia at the ’20-week scan’ (between 18+0 to 20+6 weeks of pregnancy). Sometimes we notice it during a later scan or after the baby is born.

4. Follow-up tests and appointments

As the result of the scan suggests your baby has Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia, we are referring you to a team of experts in caring for pregnant mothers and their babies before they are born. They may be based at the hospital where you are currently receiving antenatal care, or in a different hospital. You will need a second scan to find out for sure if your baby has the condition. The specialist team will be able to confirm if your baby has Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and what this might mean.

It may be useful to write any questions down that you want to ask before you see the specialist team.

The specialist team may offer you extra tests, such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis.

5. Treatment

The team looking after you and your baby will involve specialists such as neonatologists and paediatric surgeons, who will help care for your baby. They will talk to you about the condition, possible complications, treatment and how you can prepare for the birth of your baby.

Babies with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia will need specialised medical attention in a unit that is experienced in caring for babies with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia to help with their breathing. Babies with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia will also need an operation after they are born. This is usually to close the hernia and can be performed once your baby is well enough.

The length of time your baby needs to spend in hospital depends on the baby and varies from weeks to month. This depends on things like the kind of operation your baby needs, the recovery time, if there are any complications or associated conditions, how your baby is feeding and whether they need any extra help with their breathing. The specialist team will be able to give you more information depending on your individual circumstances.

6. Longer term health

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia is a wide and varied condition. It can be straightforward to treat, or complicated (and more serious) if there are other health issues as well. About 5 in 10 (50%) babies born with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia will survive. The chance of them doing well depends on how the lungs have developed and if they have any other conditions. The possible outlook for you and your baby will depend on your individual circumstances. The specialist team will support you whatever the situation.

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia can sometimes be linked with other conditions such as Down’s syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome, Patau’s syndrome or heart conditions. This happens in up to 1 in 10 (10%) cases.

The specialist team looking after your baby will do their best to:

- answer your questions

- help you plan the next steps

7. Next steps and choices

You can talk to the team caring for you during your pregnancy about your baby’s Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and your options. These will include continuing with your pregnancy or ending your pregnancy. You might want to learn more about Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. It can be helpful to speak to a support organisation with experience of helping parents in this situation.

If you decide to continue with your pregnancy, the specialist team will help you:

- plan your care and the birth of your baby

- prepare to take your baby home

If you decide to end your pregnancy, you will be given information about what this involves and how you will be supported. You should be offered a choice of where and how to end your pregnancy and be given support that is individual to you and your family.

Only you know what the best decision for you and your family is. Whatever decision you make, your healthcare professionals will support you.

8. Future pregnancies

If you decide to have another baby, they are unlikely to have Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia.

For women who have a baby with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia there is a 2 in 100 (2%) chance of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia in another pregnancy.

9. More information

Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC) is a national charity that supports people making decisions about screening and diagnosis and whether or not to continue a pregnancy.

The Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Charity (CDH UK) is a registered charity which offers information and advice to patients, families, clinicians and other organisations on CDH (including eventration) from diagnosis to childhood and beyond.

NHS.UK has a complete guide to conditions, symptoms and treatments, including what to do and when to get help.

Find out how NHS England uses and protects your screening information.

Find out how to opt out of screening.