Automatic Enrolment evaluation report 2019

Updated 12 May 2020

Executive summary

Background

The independent Pension Commission was set up to try to address long term retirement saving in the UK. Subsequently, to support the millions of people not saving enough for retirement, the Government introduced legislation in Pensions Acts from 2007, with the aim of increasing private pension saving in the UK. In 2012 automatic enrolment was introduced as part of a wider set of pension reforms designed to ensure that the UK has a pension system that enables individuals to save towards achieving the lifestyle they aspire to in retirement, while minimising the implementation challenges for employers and the pensions industry.

The reforms require employers to process automatic enrolment of eligible workers into a qualifying workplace pension scheme and make a minimum contribution. Workers are eligible provided they: are aged at least 22 and under State Pension age (SPa); earn over £10,000 per year in 2019/20 terms (these thresholds are reviewed annually); normally work in the UK and do not currently participate in a qualifying workplace pension scheme.

The automatic enrolment duties were staged in between October 2012 and February 2018 by employer size, starting with the largest employers. Since October 2017, all businesses employing someone for the very first time have to provide a workplace pension from the first day of their service.

In 2018, the first of two planned minimum contribution increases was implemented. Before April 2018, total minimum contributions were two per cent of a band of workers’ earnings, of which at least one per cent came from the employer. This rose to five per cent in April 2018, of which at least two per cent came from the employer. In 2019, the second planned increase was implemented. In April 2019, total minimum contributions rose to eight per cent of which at least three per cent must come from the employer.

Evaluation Strategy

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is committed to evaluating fully the effects of the workplace pension reforms, as set out in its evaluation strategy[footnote 1], which was refreshed in 2017. Evaluation reports have been published annually since 2013, following a baseline report in 2012 which described the landscape before the implementation of automatic enrolment[footnote 2]. This report brings together the latest evidence, including evidence published within the last 12 months and new analysis conducted for the report, showing what has happened since automatic enrolment began. In line with the evaluation strategy, this is the last report we are planning to publish on an annual basis now that employer staging and the phased increases to minimum contribution rates (i.e. ‘implementation’) have been delivered.

Key findings

Existing evidence

Since the start of automatic enrolment in 2012, more than 10.2 million workers have been automatically enrolled, and over 1.6 million employers have met their duties, with 709,000 workers having been automatically re-enrolled and 342,855 employers having met their re-enrolment duties by the end of 2019[footnote 3]. As of the end of March 2019, National Employment Savings Trust (Nest) membership stood at 7.9 million members, with over 720,000 employers.

Levels of awareness and understanding of automatic enrolment are high. In particular, at least 91 per cent of micro, small and medium-sized employers were aware of each individual ongoing duty in relation to automatic enrolment[footnote 4].

Whilst there were some concerns (mainly in 2013) amongst large employers that ongoing administration tasks relating to automatic enrolment could become a burden, attitudes became increasingly positive as rollout progressed and employers became used to the new processes. Most employers interviewed in 2016 and 2018 found the cost and time burden involved with implementing automatic enrolment to be lower than they had initially anticipated[footnote 5] [footnote 6].

Employers were typically aware of both the April 2018 and April 2019 increases in contributions. Generally, employers said that they were confident about being able to pay these new rates which they perceived as a small proportion of their overall costs.

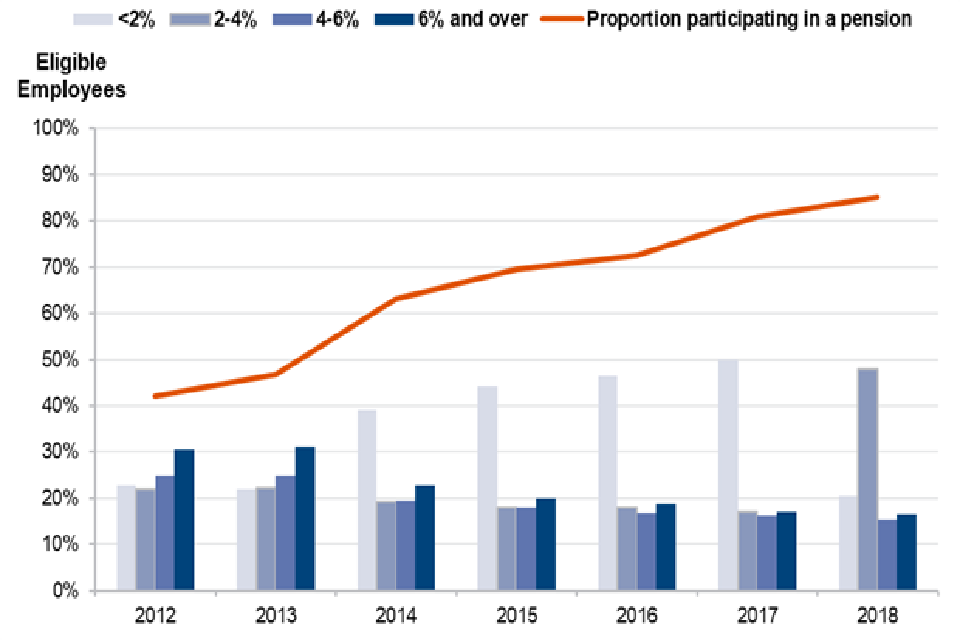

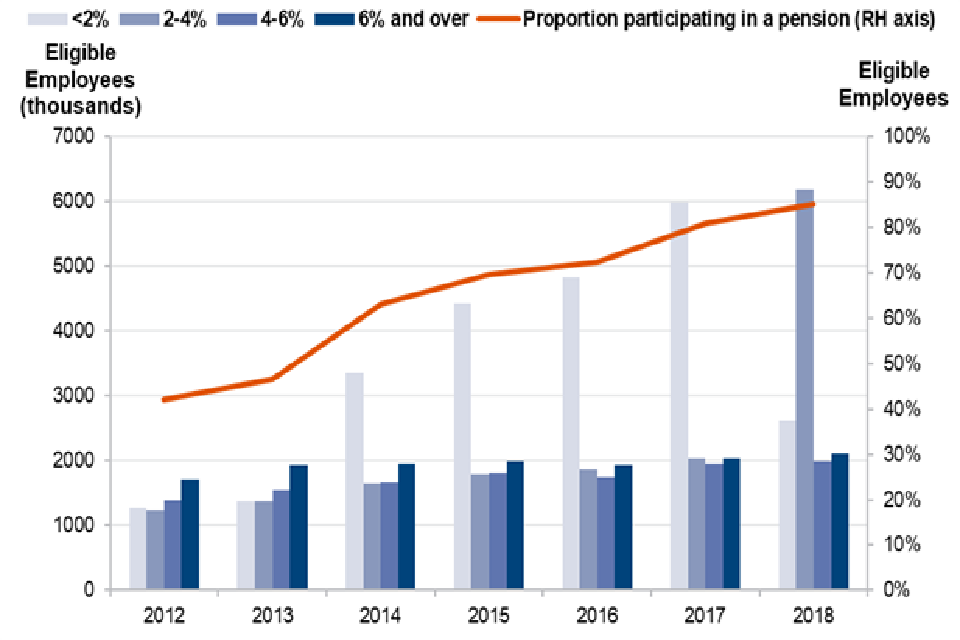

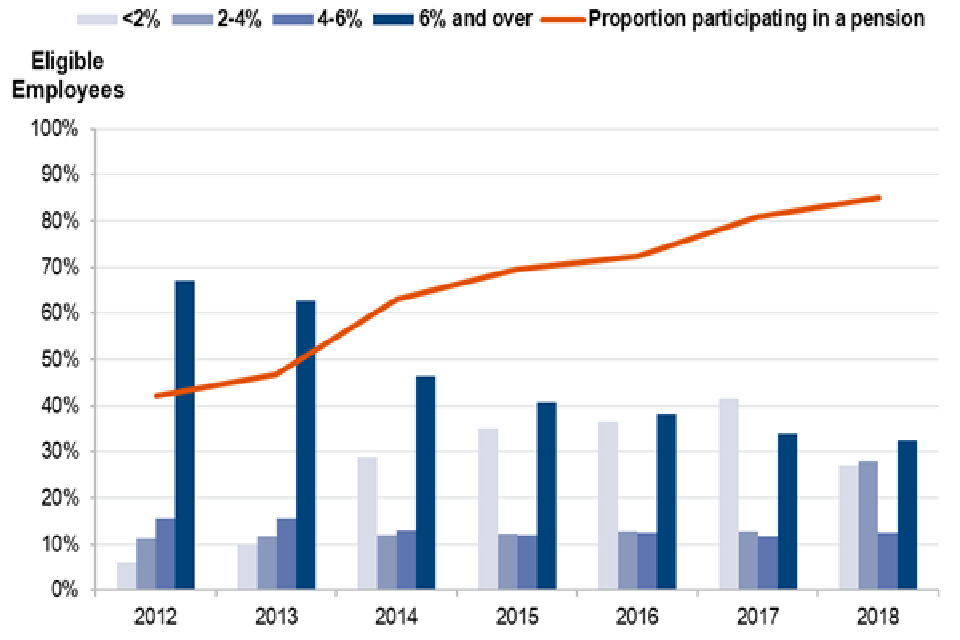

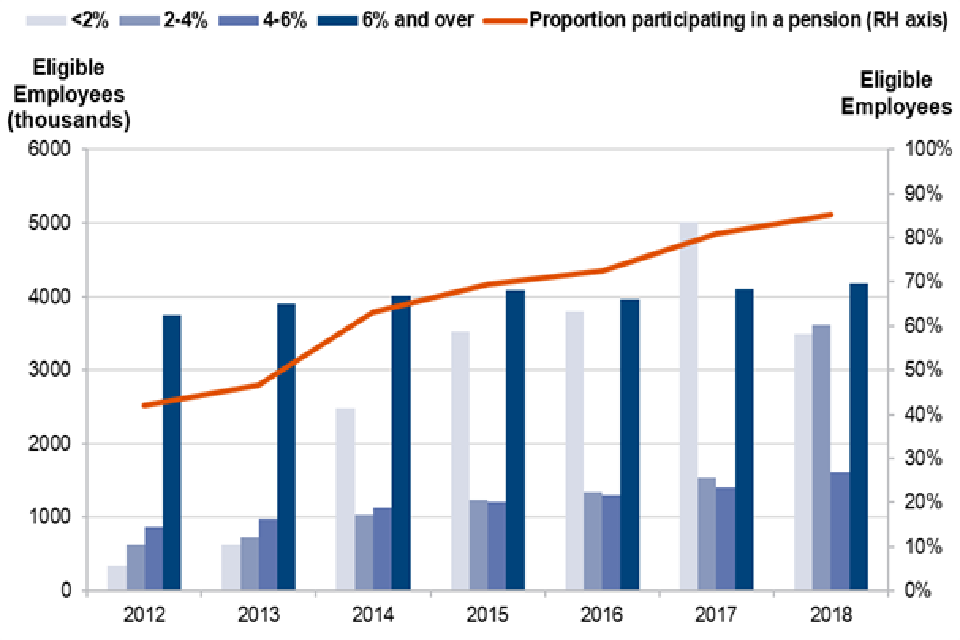

Data collected up to 2018 found that the number of eligible employees participating in a workplace pension has increased to 18.7 million (87 per cent), up from 10.7 million (55 per cent) in 2012[footnote 7].

The annual total amount saved on behalf of eligible employees across both sectors (public and private) stands at £90.4 billion in 2018, which is an increase of £7 billion from 2017. Annual total amounts increased in both public and private sectors from 2017. The public sector increased by around £2.5 billion and the private sector by £4.5 billion.

New analysis within this report

In 2019, the majority (62 per cent) of private sector employers currently had some form of workplace pension provision, up from 47 per cent in 2017. These organisations employed 94 per cent of all private sector employees.

In 2019, less than four in ten private sector employers (39 per cent) stated that the introduction of automatic enrolment had resulted in an increase in the total pension contributions that their organisation had to make[footnote 8]. However substantial variation existed by employer size.

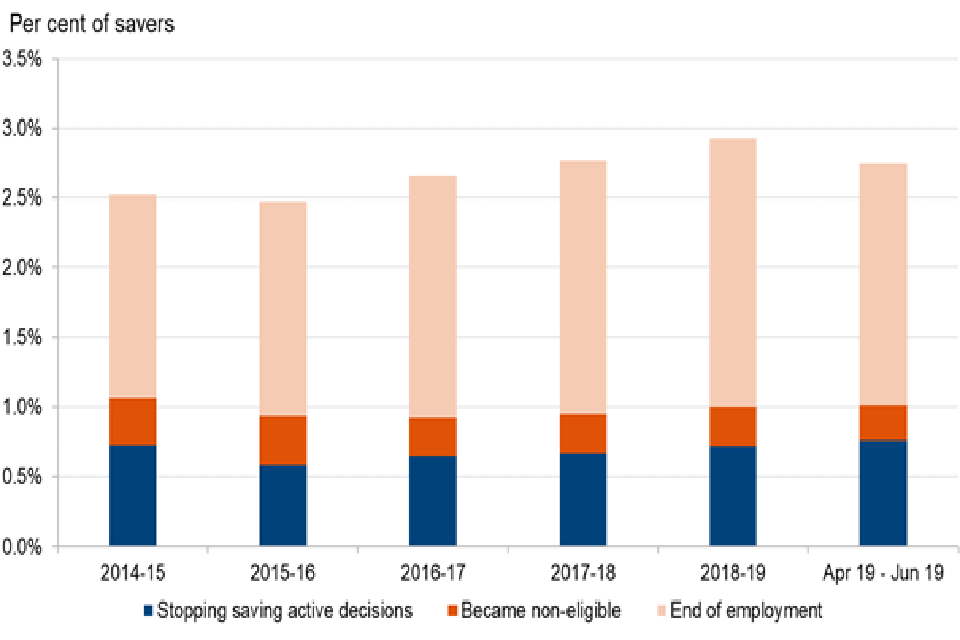

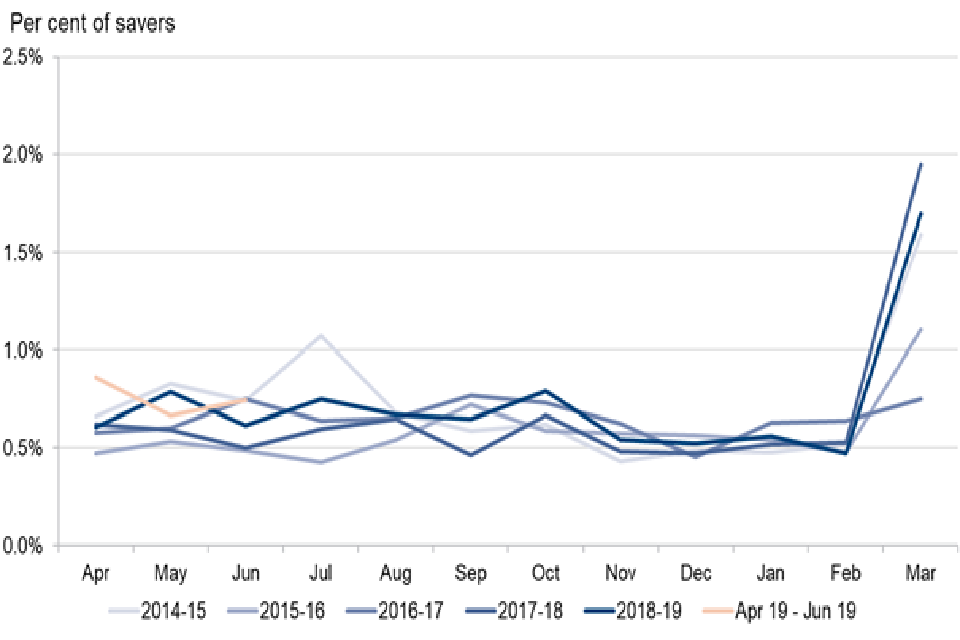

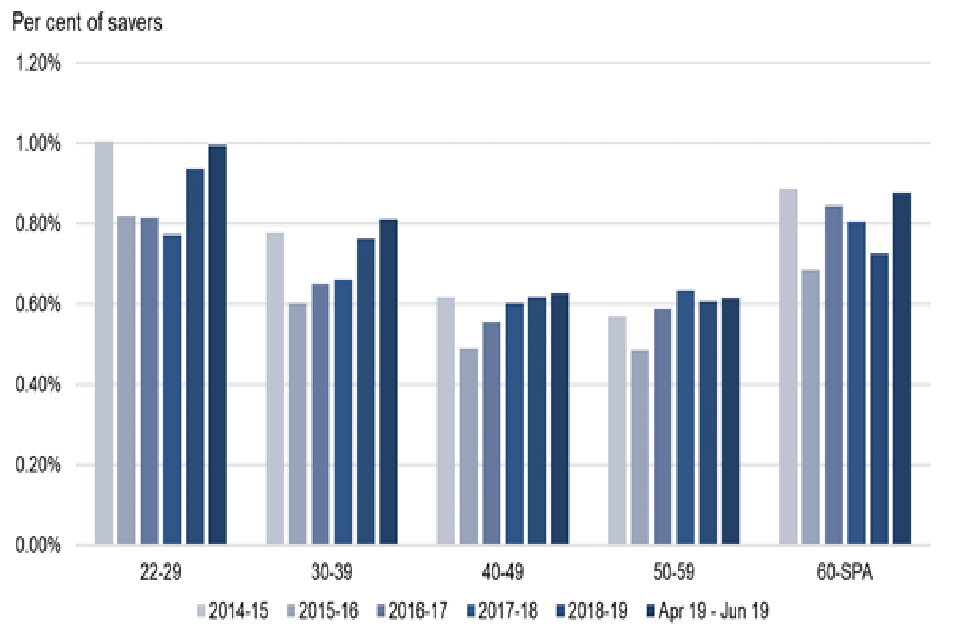

The proportion of workplace pension savers who made an active decision to stop saving (including opt-out and cessation) shows a slight increase from the 2018/19 financial year to the first quarter of the 2019/20 financial year (0.72 to 0.76 per cent), following the second increase of the automatic enrolment minimum contribution rates. Despite this small increase, the overall rate remains low.

From April 2018 onwards, the period in which the increases to minimum contribution rates took place, those aged 22 to 29 and 30 to 39 saw the largest increases in their active decision stopping saving rates (0.23 percentage points and 0.15 percentage points respectively). These increases are modest but notable relative to other age groups where the changes observed are negligible.

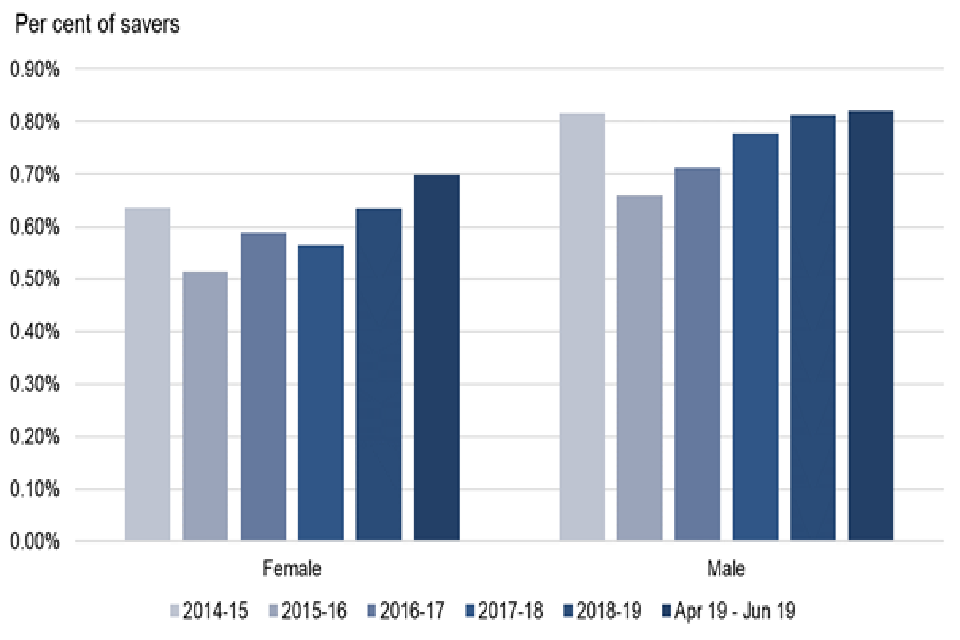

Between April 2014 and June 2019, the average active decision stopping saving rate was slightly higher for males (0.76 per cent) than for females (0.59 per cent). Throughout the implementation period of automatic enrolment, the cohort opt-out rate has remained consistently low. Overall, among employers with a scheme used for automatic enrolment, nine per cent of employees who were automatically enrolled in the 2018/19 financial year (prior to the April 2019 minimum contribution rate increase) decided to opt out within one month. This rate remained at the same level as in 2016/17.

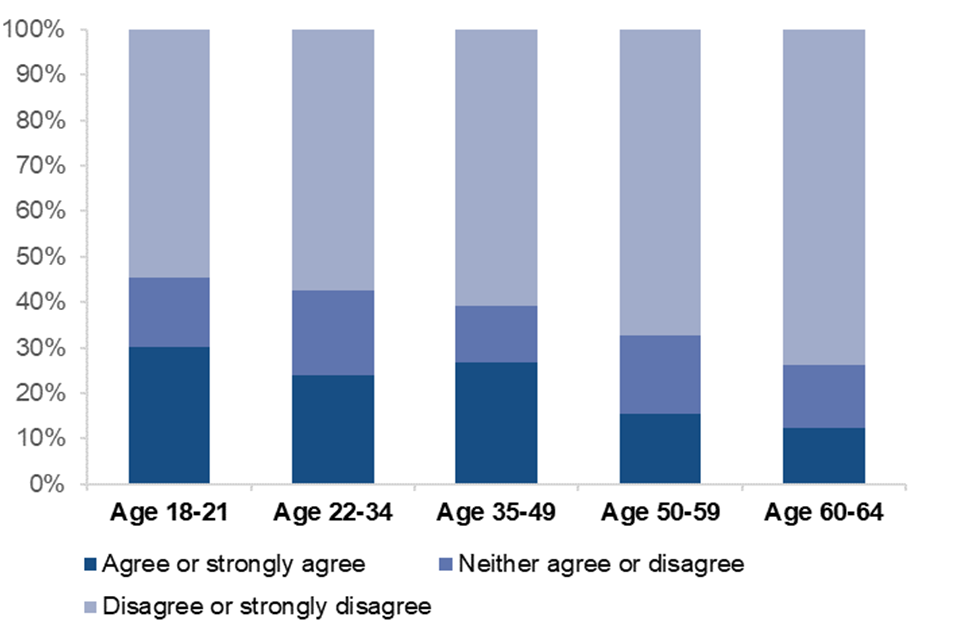

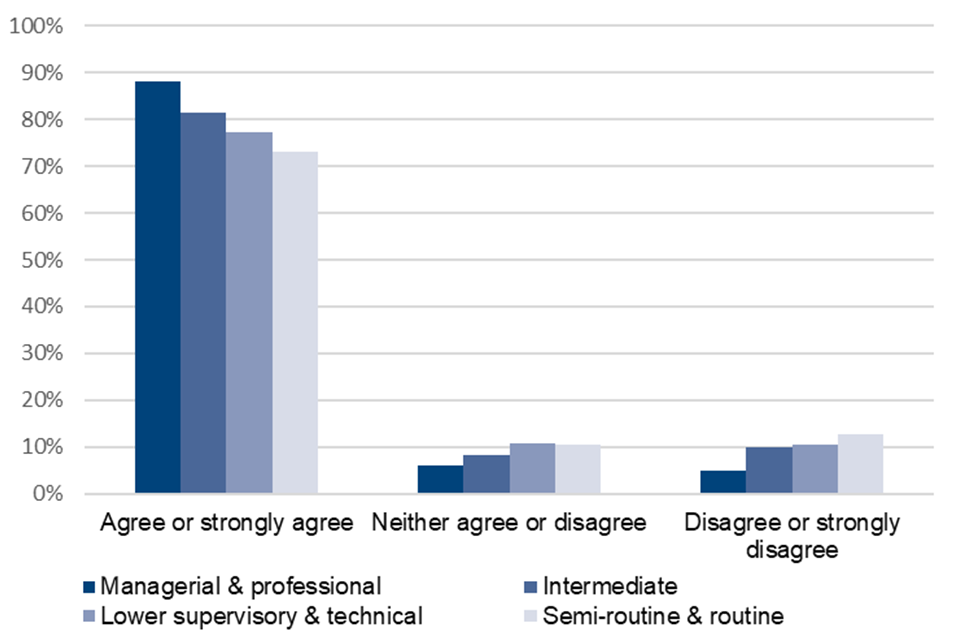

Findings from the DWP’s communications tracking research (April 2019 wave) found that the majority of individuals interviewed viewed automatic enrolment as a good thing for them personally (79 per cent); agreed saving into a workplace pension was normal for them (77 per cent); and knew where to go if they wanted to find more about workplace pensions (75 per cent). Evidence from the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey indicates that “social norming” of workplace pensions has occurred across all eligible age groups and occupational classifications.

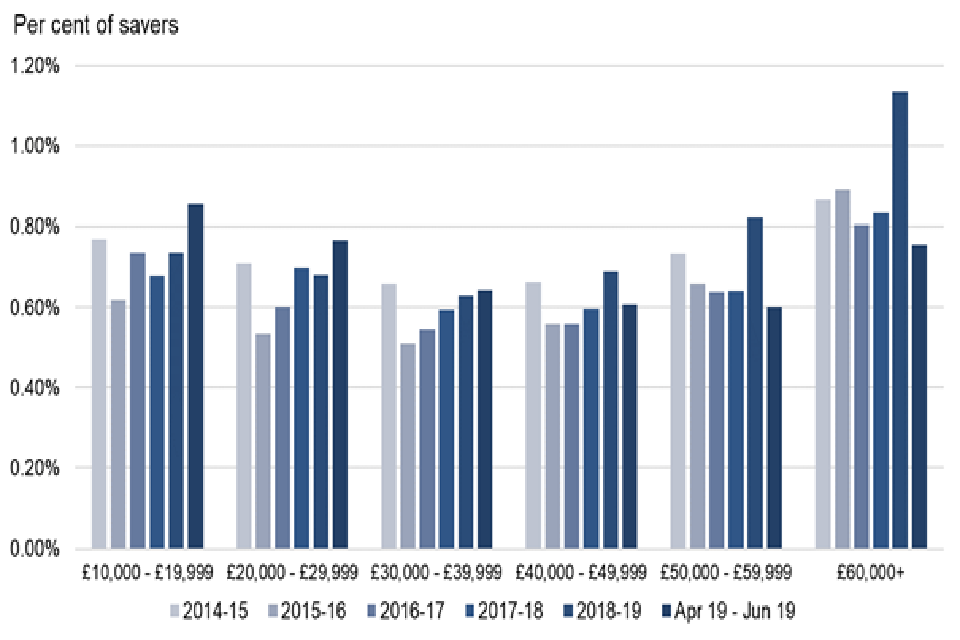

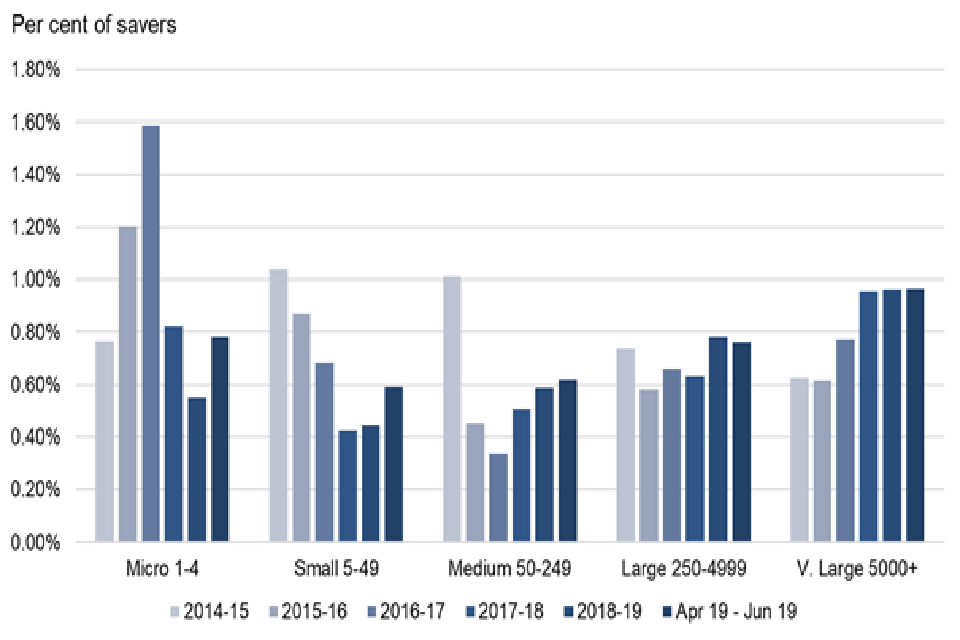

Eligible employees in the private sector with total contributions above the 2018 minimum are more likely to belong to older age brackets, have higher earnings and work for larger employers. However, the dominance of these groups among employees with total contributions above the 2018 minimum has lessened in recent years. The share of those belonging to younger age brackets, with lower earnings and working for smaller employers has increased significantly over time.

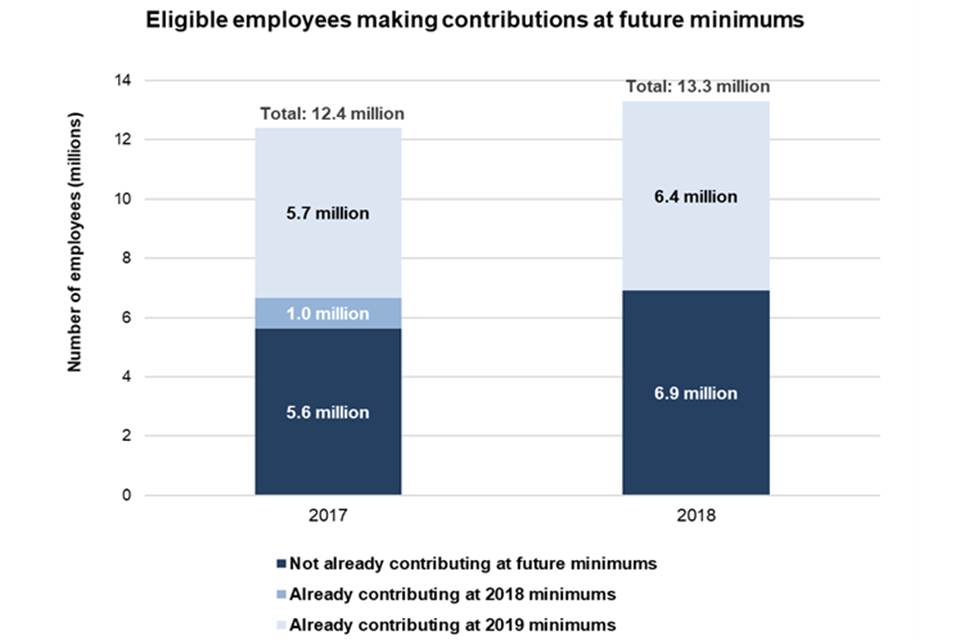

In April 2018, the number of eligible private-sector employees who were making contributions sufficient to meet the 2019 minimum requirements had risen to approximately 6.4 million. A further 6.9 million may have needed to increase contributions to meet the 2019 minimum requirements.

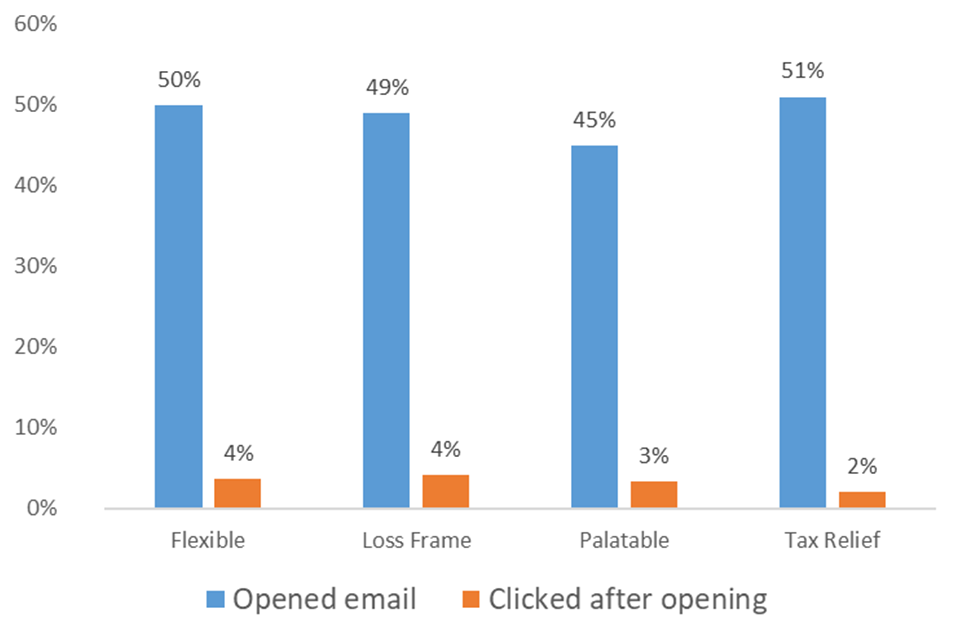

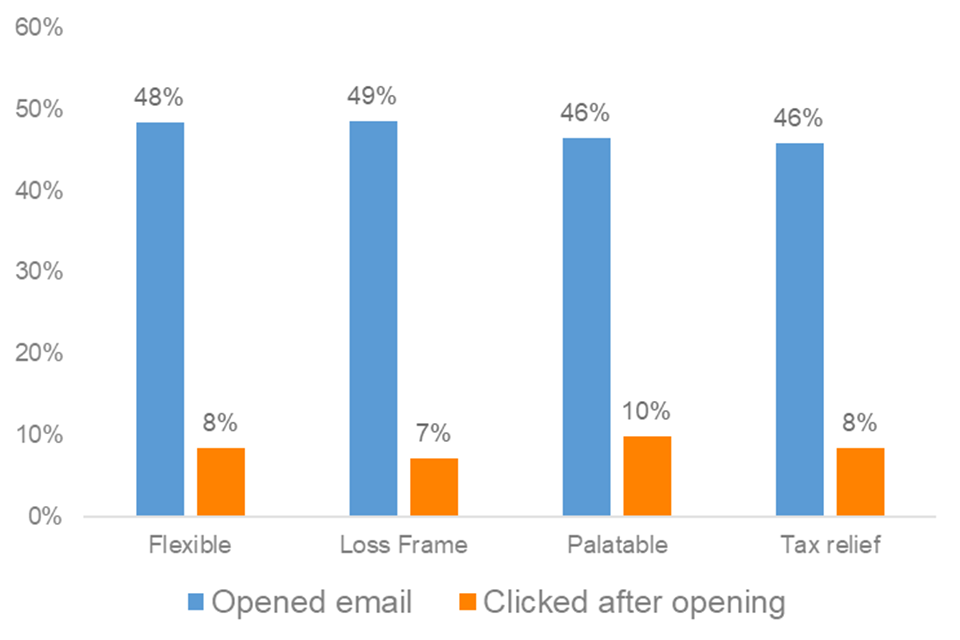

An update is also provided on DWP work with partners to encourage long-term saving behaviours amongst the self-employed, who are not covered by automatic enrolment. Initial findings from messaging trials suggest that initial ‘open’ rates of messages are relatively high in comparison with analogous industry marketing emails. However, the percentage of recipients engaging further by then logging into their accounts is lower than expected.

Next Steps

In line with the evaluation strategy, this is the last report we are planning to publish on an annual basis now that the implementation period for automatic enrolment is over (employer staging and the phased increases in minimum contributions have been delivered) and the policy has moved into steady-state.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many contributors to this report from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), The Pensions Regulator (TPR), and HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC). We would like to thank the National Employment Savings Trust (Nest) for their helpful comments throughout.

We would also like to thank the cross-Government steering group that includes representatives from DWP, TPR, Her Majesty’s (HM) Treasury and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for their support in producing this report.

The Authors

Matt Tapley – Senior Research Officer, Department for Work and Pensions

Rob Hardcastle – Senior Research Officer, Department for Work and Pensions

Maisey Hodges – Government Social Research Placement Student, Department for Work and Pensions

Annette Joseph – Senior Information Officer, Department for Work and Pensions

Nicolas Kreitmair – Assistant Economist, Department for Work and Pensions

Mycroft Leitch – Economist Placement Student, Department for Work and Pensions

Thomas Lloyd – Senior Scientific Officer, Department for Work and Pensions

Fiona Lynch – Senior Statistical Officer, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs

Lorraine Pearson – Principal Research Officer, Department for Work and Pensions

James Rees – Principal Scientific Officer, Department for Work and Pensions

Verite Savage – Government Social Research Placement Student, Department for Work and Pensions

Emily Severn – Research Officer, Department for Work and Pensions

Glossary of terms

Active member – Individuals currently contributing to a pension scheme, or having contributions made on their behalf.

Automatic enrolment – In 2008, the Government introduced a law designed to help people save more for their retirement. This requires, from 2012, all employers to enrol their eligible jobholders into a workplace pension scheme if they are not already in one. In order to preserve individual responsibility for the decision to save, workers have the right to opt out of the scheme.

Career average – A Defined Benefit (DB) scheme that gives individuals a pension based on their salary times the accrual rate in each year of their working life. Entitlements that are built up each year are revalued in line with inflation or earnings.

Ceasing active membership – If an eligible jobholder chooses to stop paying into an automatic enrolment scheme after the end of the opt-out period, they are said to cease active membership.

Cessation – When a worker has ceased active membership.

Contract-based pensions – Pensions where the legal contract is between the individual and the pension provider, usually an insurance company. Also known as personal pensions.

Contributions – The amount (often expressed as a percentage of earnings) that a worker and/or employer pays into a pension.

Defined Benefit (DB) – A type of occupational pension scheme. In a DB scheme the amount the member gets at retirement is based on various factors, but is predetermined (defined). These could include how long they have been a member of the pension scheme and earnings. Examples of DB pension schemes include final salary or career average earnings-related pension schemes. In most schemes, some of the pension can be taken as a tax-free lump sum. The rest is then received as regular income, which might be taxable.

Defined Contribution (DC) – A type of pension scheme. In a DC scheme a member’s pension pot is put into various investments such as shares (shares are a stake in a company). The amount in the pension pot at retirement is based on how much is paid in and how well the investments have performed. The pension can usually be accessed from age 55. These are also known as ‘money purchase’ schemes.

Duties start date – An employer’s automatic enrolment duties begin on the day an employers’ first member of staff starts working for them. This is referred to as their ‘Duties Start Date’.

Eligible jobholder – A worker (sometimes referred to as an employee) who is ‘eligible’ for automatic enrolment. An eligible jobholder must be aged at least 22 but under State Pension age, earn above the earnings trigger for automatic enrolment, and work or usually work in the UK and not already be a member of a qualifying pension scheme.

Employer size – Employer size is determined by the number of employees. For the purpose of staging dates, The Pensions Regulator categorises employer size based on number of employees in Pay As You Earn (PAYE) schemes as follows:

Micro = 1 to 4 employees Small = 5 to 49 employees Medium = 50 to 249 employees Large = 250+ employees

If any alternative definitions of employer size are used, they will be defined in the report.

Entitled worker – A worker who is aged at least 16 and under 75; works, or ordinarily works, in the UK; and earns below the lower earnings level of qualifying earnings (£6,136 for the 2019/20 tax year). Entitled workers are not eligible for automatic enrolment, although they can choose to join a workplace pension. Their employer is not required to make a contribution if they do so.

Group Personal Pension (GPP) – A type of personal pension scheme set up by an employer on behalf of its workers. Although the scheme is arranged by the employer, each pension contract is between the pension provider and the worker. The employer may also pay into the scheme, adding money to each worker’s pension pot.

Group Stakeholder Pension – An arrangement made for the employees of a particular employer, or group of employers, to participate in a stakeholder pension on a group basis. This is a collective arrangement only; the contract is between the individual and the pension provider, normally an insurance company.

Group self-invested personal pension (GSIPP) – A personal pension in which the policy holder rather than the pension company chooses the investments. GSIPPs allow members to invest in a wide range of assets, including commercial property and individual shares.

Hybrid pension scheme – A private pension scheme which is neither purely a DB nor DC arrangement. Typically a hybrid scheme is a DB scheme, which includes elements of DC pension design.

Levelling down – Strategies employers might use to reduce the generosity of contributions or outcomes for existing pension scheme members.

Lower Earnings Limit (LEL) – Under automatic enrolment individuals and their employers must contribute above a certain minimum amount. That minimum amount is based on a band of earnings – between the Lower Earnings Limit (LEL) and the Upper Earnings Limit (UEL). Where an individual earns over the trigger of £10,000 and they are aged between 22 and State Pension age (SPA), they will automatically be enrolled into a pension and pay contributions on at least this band of earnings. The 2019/20 levels for the LEL and UEL are £6,136 and £50,000 respectively, reviewed annually.

Master trust – A multi-employer trust-based pension scheme, which is promoted to and used by a range of unconnected employers.

National Employment Savings Trust (Nest) – A multi-employer trust-based workplace pension scheme, established by legislation, to support automatic enrolment and ensure that all employers have access to a quality, low-cost pension scheme with which to meet the employer duties.

Non-eligible jobholder – A worker who is not eligible for automatic enrolment but can choose to ‘opt in’ to an automatic enrolment scheme and will be entitled to a mandatory employer contribution should they do so. Non-eligible jobholders are in either of the following two categories: a worker who is aged at least 16 and under 75 and earns above the lower earnings level of qualifying earnings but below the earnings trigger for automatic enrolment; or is aged at least 16 but under 22, or between State Pension age and under 75; and earns above the earnings trigger for automatic enrolment.

Occupational pension scheme – A type of workplace pension organised by an employer (or on behalf of a group of employers) to provide benefits for employees on their retirement and for their dependants on their death. In the private sector, occupational schemes are trust-based. Types of occupational scheme include DB, DC and hybrid schemes.

Opt in – If a worker is not eligible for automatic enrolment, for example a non-eligible jobholder or entitled worker, they can ask their employer to become a member of the pension scheme. If the employer receives such a request then they must put the worker into the pension scheme and, in the case of the non-eligible jobholder, pay contributions to the scheme on their behalf.

Opt out – Where a jobholder has been automatically enrolled, they can choose to ‘opt out’ of a pension scheme. This has the effect of undoing active membership, as if the worker had never been a member of a scheme on that occasion. It can only happen within a specific time period, known as the ‘opt-out period’.

Opt-out period – A jobholder who becomes an active member of a pension scheme under the automatic enrolment provisions has a period of one calendar month during which they can opt out and get a full refund of any contributions made. This ‘opt-out period’ starts from whichever date is the later of the date active membership was achieved or the date they received a letter from their employer with their enrolment information. After this opt-out period a jobholder can still choose to leave the scheme at any time, but will not usually get a refund of contributions. These will instead be held in their pension until they retire. A jobholder cannot opt out before the opt-out period starts (i.e. they cannot opt out before they have been automatically enrolled).

PAYE – PAYE is the system that HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) uses to collect Income Tax and National Insurance contributions from employees. They are deducted throughout the tax year based on employees’ earnings and then paid to HMRC.

Pension provider – An organisation, often a life assurance or asset management company, that offers financial products and services relating to retirement income.

Pension scheme – A legal arrangement offering benefits to members.

Personal pension (PP) – An arrangement where the pension is set up directly between an individual and a pension provider. This could be set up by an employer (see Group Personal Pension) or by an individual (sometimes referred to as an Individual Personal Pension). The individual pays regular monthly amounts or a lump sum to the pension provider who will invest it on the individual’s behalf. The fund is usually run by financial organisations such as insurance companies or asset managers. Personal pensions are a form of DC pension. See also Contract-based pensions.

Planned contribution increases – The Government set a minimum level of contributions that have to be put into a pension scheme by a worker and an employer, and within that has set a minimum level for the employer contribution:

| Date effective | Employer minimum contribution | Employee contribution (if employer pays minimum) | Minimum total contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up until 5 April 2018 | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| 6 April 2018 to 5 April 2019 | 2% | 3% | 5% |

| 6 April 2019 onwards | 3% | 5% | 8% |

The state contributes to the worker’s pension through tax relief, typically at their marginal tax rate.

Postponement – An additional flexibility for an employer that allows them to choose to postpone automatic enrolment for a period of their choice of up to three months. Postponement can only be used for a worker on the employer’s staging date; the first day of worker’s employment; or on the date a worker employed by them meets the criteria to be an eligible jobholder. If an employer chooses to use postponement, they must provide written notice of this to their workers. This is also called ‘deferral’.

Protected groups – Under the Equality Act 2010, protected groups share a particular characteristic against which it is illegal to discriminate.

Qualifying scheme – To be a qualifying scheme for automatic enrolment, a pension scheme must meet certain minimum requirements, which differ according to the type of pension scheme. DC scheme requirements are based on the contribution rate and require a minimum total contribution based on qualifying earnings, of which a specified amount must come from the employer. The minimum requirements for DB schemes are based on the benefits a jobholder is entitled to under the scheme. Hybrid pension schemes contain elements of DB and DC and, depending on what type of hybrid they are, will have to meet either the same, or a modified version of, the minimum requirements for DB or DC pension schemes or a combination of both.

Real Time Information (RTI) – Under RTI, information about tax and other deductions (including employee pension contributions) under the PAYE system is transmitted to HMRC by the employer every time an employee is paid.

Re-enrolment – Every three years, staff who were automatically enrolled but opted out of or ceased active membership of a pension scheme more than 12 months before an employer’s re-enrolment date must be automatically re-enrolled into the scheme. Again, they have the choice to opt out. This is intended to prompt them to revisit their initial decision to opt out.

Staging – Refers to the staggered introduction of the employer duties, starting with the largest employers, based on PAYE scheme size, in October 2012, to the smallest in 2017. New PAYE schemes from April 2012 staged last, in 2017 and 2018. Staging has now completed, following the last staging date in February 2018.

Staging date – The date on which an employer was required to begin automatic enrolment. This date was determined by the total number of employees in an employer’s largest PAYE scheme on 1 April 2012.

Stakeholder pension – A type of personal pension arrangement introduced in April 2001 which could be taken out by an individual or facilitated by an employer. Where an employer had five or more staff and offered no occupational pension and an employee earned over the lower earnings limit, the provision of access to a stakeholder scheme, with contributions deducted from payroll, was compulsory. Stakeholder pensions are usually a contract-based pension scheme, subject to government regulations, which limited charges and allowed individuals flexibility about contributions and transfers, introduced in April 2001. These ceased to be mandatory after the workplace pension reforms were introduced.

State Pension age (SPA) – The earliest age at which an individual can claim their State Pension.

The Pensions Regulator (TPR) – Referred to as ‘the regulator’ and is the UK regulator of workplace pension schemes, including limited aspects of workplace personal pensions. It is responsible for ensuring employers are aware of their duties relating to automatic enrolment, how to comply with them and enforcing compliance. It uses a programme of targeted communications and a range of information to help employers understand what they need to do and by when. TPR is also responsible for regulating occupational pension schemes, including Master Trusts.

Trust-based pensions – Pension schemes set up under trust law by one or more employers for the benefit of workers. In a trust-based scheme a board of trustees is set up to run the scheme. Trustees are accountable for making decisions about the way the scheme is run, although they may delegate some of the everyday tasks to a third party. See also occupational pension scheme and master trust.

Upper Earnings Limit (UEL) – Under automatic enrolment individuals and their employers must make contributions above a certain minimum amount. That minimum amount is based on a band of earnings – between the Lower Earnings Limit (LEL) and the Upper Earnings Limit (UEL). Where an individual earns over the trigger of £10,000 and they are aged between 22 and State Pension age (SPA), they will automatically be enrolled into a pension and pay contributions on this band of earnings. The 2019/20 levels for the LEL and UEL are £6,136 and £50,000 respectively, reviewed annually.

Waiting period – A type of postponement, where new workers or newly eligible workers may have their automatic enrolment delayed for up to three months.

Worker – An employee or individual who has a contract to provide work or services personally and is not undertaking the work as part of their own business.

Workplace pensions – Any pension scheme provided as part of an arrangement made for the employees of a particular employer.

Workplace pension reforms – The reforms introduced as part of the Pensions Acts 2007 and 2008 (and updated as part of the Pensions Act 2011 and 2014). Starting in 2012, the reforms include a duty on employers to automatically enrol all eligible jobholders into a qualifying workplace pension scheme.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The independent Pension Commission was set up to try to address long term retirement saving in the UK. Subsequently, to support the millions of people not saving enough for retirement, the Government introduced legislation in Pensions Acts from 2007, with the aim of increasing private pension saving in the UK. In 2012 automatic enrolment was introduced as part of a wider set of pension reforms designed to ensure that the UK has a pension system that enables individuals to save towards achieving the lifestyle they aspire to in retirement, while minimising the implementation challenges for employers and the pensions industry.

The reforms require employers to process automatic enrolment of eligible workers into a qualifying workplace pension scheme and make a minimum contribution. Workers are eligible provided they: are aged at least 22 and under State Pension age (SPa); earn over £10,000 per year in 2019/20 terms (these thresholds are reviewed annually); normally work in the UK and do not currently participate in a qualifying workplace pension scheme.

The automatic enrolment duties were staged in between October 2012 and February 2018 by employer size, starting with the largest employers. Since October 2017, all businesses employing someone for the very first time have to provide a workplace pension from the first day of their service.

In 2018, the first of two planned minimum contribution increases was implemented. Before April 2018, total minimum contributions were two per cent of a band of workers’ earnings, of which at least one per cent came from the employer. This rose to five per cent in April 2018, of which at least two per cent came from the employer. In 2019, the second planned increase was implemented. In April 2019, total minimum contributions rose to eight per cent of which at least three per cent must come from the employer.

1.2. Evaluation strategy

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is committed to fully evaluating the effects of the workplace pension reforms, as set out in its evaluation strategy[footnote 9], which was refreshed in 2017. Evaluation reports have been published annually since 2013, following a baseline report in 2012 which described the landscape before the implementation of automatic enrolment[footnote 10]. This report brings together the latest evidence showing what has happened since automatic enrolment began. In line with the evaluation strategy, this is the last report we are planning to publish on an annual basis now that employer staging and the phased increases to minimum contribution rates (i.e. ‘implementation’) have been delivered.

It is important to note that owing to time lags and data availability, the latest research and analysis in this report will capture different stages of automatic enrolment implementation (for example, analysis may fall before or after the planned minimum contribution increases in April 2018 and April 2019). The data source underlying the research and analysis presented and the period being captured is noted in the supporting commentary. The DWP’s biennial Employers’ Pension Provision (EPP) survey[footnote 11] is an important source of evidence throughout the report. Headlines from the recently conducted 2019 EPP survey, for which a full report is planned for publication in 2020, are included where possible[footnote 12]. However, in other cases, EPP 2017 remains our most recent source of evidence at this stage.

1.3. Report structure

The structure of this year’s report is as follows:

- delivery of reforms (Chapter 2)

- employers’ implementation of reforms (Chapter 3)

- impact of automatic enrolment on individuals and saving (Chapter 4)

- wider impact of automatic enrolment and developments to the pensions landscape (Chapter 5)

- conclusion (Chapter 6)

2. Delivery of reforms

This chapter encompasses key findings from research and analysis on the delivery of the National Employment Savings Trust (Nest); The Pensions Regulator (TPR)’s compliance regime; and DWP and the Regulator’s communication strategies in relation to automatic enrolment. This relates to the following evaluation strategy question:

Do established delivery mechanisms support automatic enrolment objectives? (EQ1)

Summary

Existing evidence

-

since the start of automatic enrolment in 2012, more than 10.2 million workers have been automatically enrolled, and over 1.6 million employers have met their duties, with 709,000 workers having been automatically re-enrolled and 342,855 employers having met their re-enrolment duties by the end of 2019

-

as of the end of March 2019, National Employment Savings Trust (Nest) membership stood at 7.9 million members, with over 720,000 employers

2.1. Role of The Pensions Regulator

The role of The Pensions Regulator (TPR) is to maximise compliance with the employer duties and safeguards set out in legislation, using a risk-based approach to deter, prevent or address non-compliance. It is also the UK regulator of workplace pension schemes, including limited aspects of workplace personal pensions.

2.1.1. Communicating reforms to employers and their advisers

TPR aims to help employers understand what they need to do, and when, in order to meet their automatic enrolment duties. TPR operate a communications strategy based on direct engagement with employers, and through their advisers, which involves writing (via emails and letters) at key intervals. Previously, this would have been during the roll out of automatic enrolment to different sized employers in relation to the date that their automatic enrolment duties start, and more recently, to inform them of the planned April 2019 minimum contribution increase[footnote 13].

In TPR’s Winter 2019 Ongoing Duties Survey[footnote 14], employers were asked how they first became aware of the planned increase in minimum contributions in April 2019. A wide range of sources were mentioned but the most common were emails or letters from TPR (36 per cent of micro employers, 42 per cent of small employers and 32 per cent of medium employers).

For all new employers, TPR sends them an information pack containing details of their duties start date and declaration of compliance deadline, based upon the first day of employment of their first worker. This pack contains guidance on how to complete their automatic enrolment duties, with links to relevant online tools and information on the TPR website.

TPR’s Adviser Engagement 2019 report surveyed relevant advisers operating in the automatic enrolment market (accountants, bookkeepers, payroll administrators, and independent financial advisers)[footnote 15]. The research found that the TPR website was the most widely used active channel by accountants (91 per cent), payroll administrators (94 per cent) and bookkeepers (85 per cent). An active channel is a source an adviser would use if they needed specific information or assistance about automatic enrolment. TPR’s website was also the most heavily relied upon channel by these advisers (between 56 per cent to 60 per cent).

Advisers were also asked about the channels through which they received information about automatic enrolment. 88 per cent of accountants, 94 per cent of payroll administrators and 85 per cent of bookkeepers received client-specific emails or letters from TPR (that either came direct to the adviser or were forwarded to the adviser by their client). In terms of advisers’ reliance on these channels, to ensure they had the information on automatic enrolment they needed, the majority of accountants (52 per cent), payroll administrators (61 per cent) and bookkeepers (59 per cent) reported that they relied heavily on client-specific emails and letters from TPR.

2.1.2. Declarations of compliance

TPR publishes monthly information about the number of employers who have complied with their duties by completing their declaration of compliance and reporting on the number of eligible jobholders automatically enrolled[footnote 16]. Since July 2012, up to the end of December 2019, 1,609,947 employers had declared their compliance with the duties, with over 10.2 million workers automatically enrolled. Similarly, 342,855 employers had confirmed that they had completed their re-declaration of compliance, with 709,000 workers having been automatically re-enrolled.

The data also show that 12.11 million workers were not automatically enrolled because they were already active members of a qualifying workplace pension scheme or had Defined Benefit (DB) or hybrid scheme transitional arrangements applied to them. A further 9.6 million workers were not automatically enrolled as they did not meet either the earnings or age criteria at the time (e.g. a worker who earned over £10,000 per year, but was aged under 22 years old would not be automatically enrolled).

Additional detailed analysis of declaration of compliance data is available in the regulator’s 2019 ‘Automatic enrolment: commentary and analysis’ report[footnote 17].

2.1.3. Enforcement

TPR’s approach is to tell employers what they must do to comply with the law in the first instance, but where it encounters non-compliance, TPR uses its powers to ensure that employers comply with their legal obligations. Its approach to maximising compliance is set out in its compliance and enforcement strategy[footnote 18] and policy[footnote 19].

TPR publishes information on a quarterly basis about its cases and the powers it has used relating to automatic enrolment and associated employer duties[footnote 20]. From July 2012 to the end of September 2019, the regulator had concluded 319,720 cases investigating possible non-compliance by employers. Between July and September 2019, TPR continued to use its powers: in Q2 2019/20 it served 11,202 compliance notices, with most employers subsequently complying when given this prompt to remind them of their duties.

Since the start of the year, TPR has carried out country-wide inspections or ‘spot checks’. Employers are identified through data and intelligence analysis and scheduled for either desk-based investigation or an inspection in person at their place of business. In the first quarter of 2019/20, 74 per cent of spot checks revealed breaches of pensions legislation, with 76 per cent of these resulting in enforcement action[footnote 21].

Between April 2018 - March 2019, TPR used its formal powers on 128,807 occasions. The proportion of formal notices has increased significantly due to TPR transitioning from enforcing against medium employers to the higher-volume small and micro employers. More information can be found in the 2019 ‘Automatic enrolment: Commentary and analysis’ report[footnote 22].

2.1.4. Employer forecast

During the rollout of automatic enrolment, TPR were largely focused on compliance amongst large volumes of staged employers, and re-enrolment for the largest employers. Following the end of the policy’s implementation period, the focus shifted to the steady volumes of new employers, and the re-enrolment of staged employers.

All employers will still be subject to some duties even if they do not employ eligible staff, such as needing to provide information to their employees and declaring their compliance with TPR. If their staff ask to join or opt in to a pension scheme, they will need to meet their request. They should also monitor the age and earnings of their staff and enrol any future workers who are eligible, or existing ones that later trigger eligibility (e.g. when a 21 year-old turns 22).

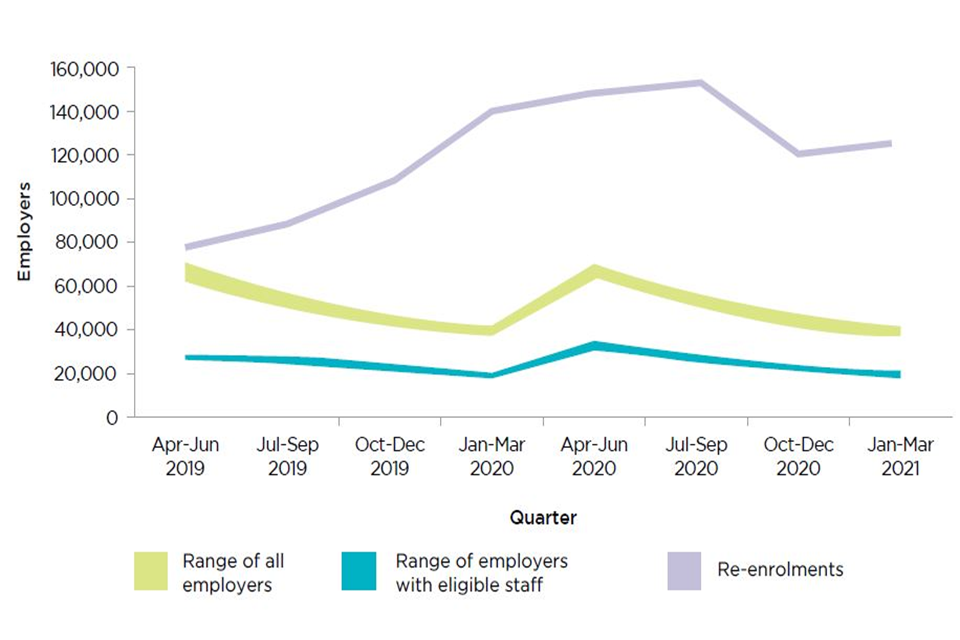

TPR included a forecast of employers who are expected to have automatic enrolment duties to the end of 2020/21 in its 2019 ‘Automatic enrolment: Commentary and analysis’ report[footnote 23]. This is a forecast, so the data is presented as a range of the number of employers who are due to reach their duties start date and have eligible jobholders to automatically enrol based on a lower and upper estimate, as illustrated by Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 - Quarterly forecast of employers due to comply with automatic enrolment

Source: TPR forecast from “Automatic enrolment: Commentary and analysis: April 2018 – March 2019”.

The forecast is, by its nature, uncertain and does not account for future economic factors, threshold changes or the effect of the National Living Wage, to give a few examples. It also does not account for cases where employers may come into existence or cease to exist as a result of changes to financial or legal status.

2.2. Communicating reforms to individuals

To assist the delivery of the reforms, DWP has delivered advertising campaigns to raise awareness and understanding of automatic enrolment among individuals and employers. Launching in 2012, the campaigns have aimed to build awareness of workplace pensions amongst employees and help employers recognise their responsibilities. Campaign activity has continued to evolve through employer staging and the planned increases in minimum contribution levels.

Over the last few years, wider pensions campaigns have been aligned under a single ‘Get to know your pension’ branding, ensuring clear links between Workplace Pensions messaging and wider retirement planning nudges. The latest iteration of the campaign, using the “You Work, Your Pension Works” creative approach, launched in October 2017 and is planned to run through until Summer 2020.

Messages for individuals are benefits led, reminding employees that a workplace pension is like having another you, at work, helping you earn money for when you retire. Campaign activity runs across multiple channels including television, video on demand, radio, digital and social media. This included a media partnership with the Channel 4 programme Gogglebox, to support the second planned increase in minimum contributions.

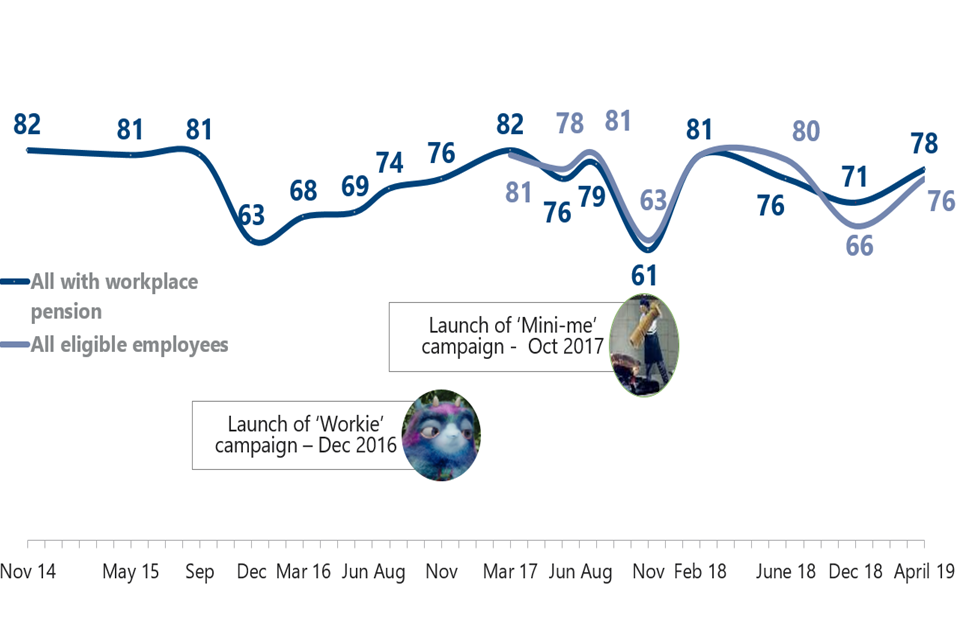

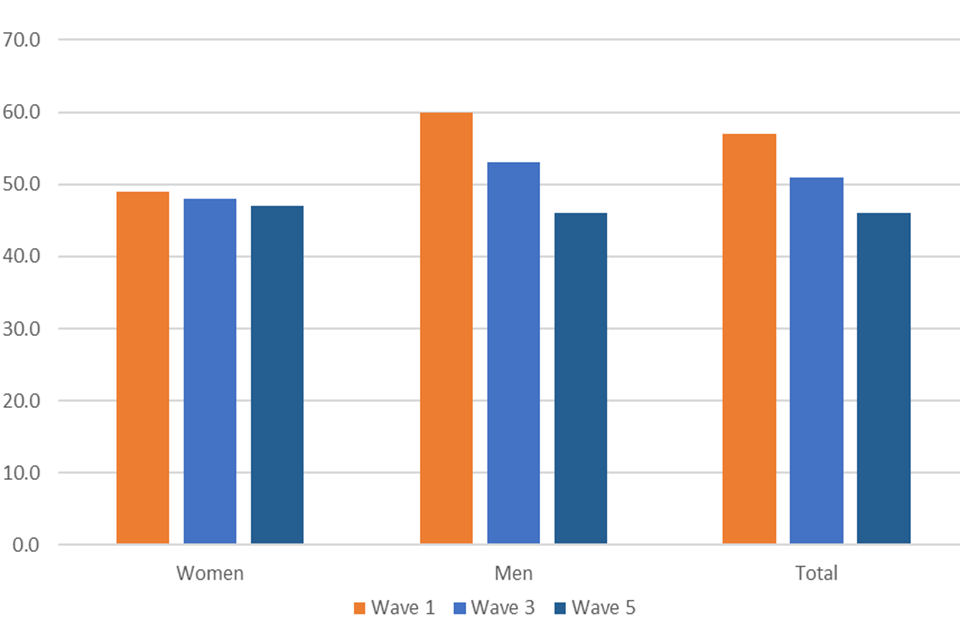

DWP monitors campaign activity through a communications tracking survey, measuring awareness, positivity, social norms and intention. The most recent wave (April 2019) showed that overall campaign recognition was 76 per cent and broadly consistent with previous waves (Figure 2.2)[footnote 24].

Figure 2.2 - Awareness of DWP communications campaign activity, Nov 2014 – Apr 2019

Source: Workplace Pension: research into saving for retirement, communications tracker (2014 – 2019).

Results from the communications tracker survey are covered in more detail in section 4.4.

2.3. Nest

The National Employment Savings Trust (Nest) is a workplace pension scheme established in 2010 with a primary purpose to support the introduction of automatic enrolment. It is a trustee-governed automatic enrolment qualifying scheme. In 2011, Nest began on a voluntary basis in preparation for the first wave of employer duties from September 2012. It is subject to a Public Service Obligation (PSO) to accept all employers wanting to join the scheme to fulfil their automatic enrolment duties.

The Nest Corporation’s annual report for 2018/19[footnote 25] outlined what Nest had achieved over the year from April 2018 to the end of March 2019. Significant results over the year as of March 31st 2019 included:

- Nest’s membership had risen to 7.9 million members and over 720,000 employers, compared to 6.4 million members and 616,000 employers at the time of the 2017/18 Nest annual report[footnote 26].

- at the end of March 2019, Nest managed around £5.7 billion in assets, compared to approximately £2.7 billion at the end of March 2018.

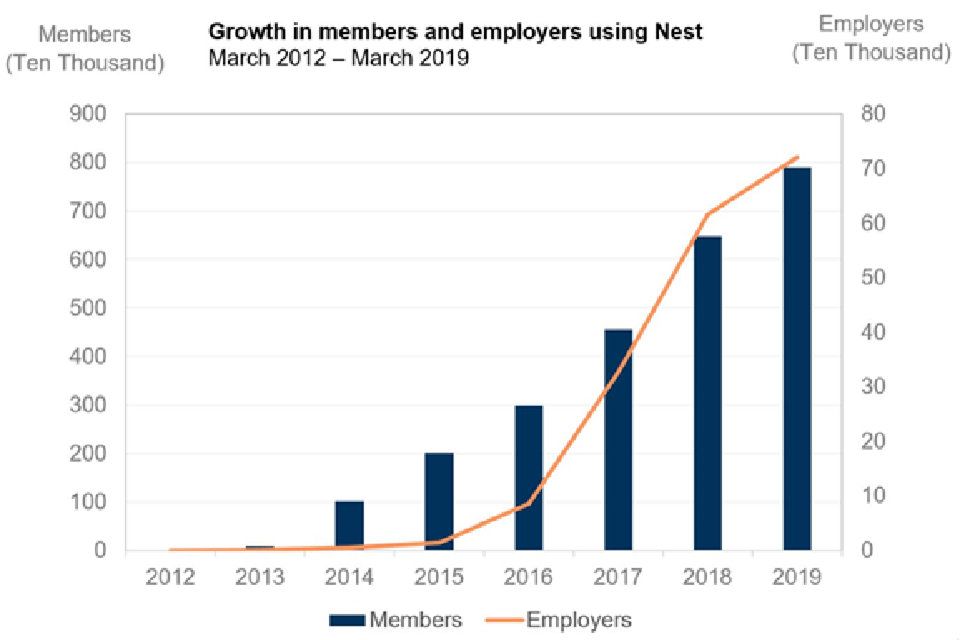

Figure 2.3 illustrates the growth in membership and the number of employers using Nest since 2012.

Source: Nest administrative data from Nest Corporation’s Annual Report and Accounts (2012 – 2019).

As at November 2019, Nest’s membership had further risen to over 8.6 million members and 770,000 employers. Their assets under management had also increased reaching over £8.5 billion.

3. Employers’ implementation of reforms

This chapter examines how employers have responded to the requirement to implement automatic enrolment. This relates to the following evaluation strategy questions:

Do employers know about, understand and comply with their employer duties? (EQ2) To what extent is delivery achieved with minimal employer burden? (EQ5)

Summary

Existing evidence

-

levels of awareness and understanding of automatic enrolment are high. In particular, at least 91 per cent of micro, small and medium-sized employers were aware of each individual ongoing duty in relation to automatic enrolment

-

employers were typically aware of both the April 2018 and April 2019 increases in contributions, and had relatively neutral attitudes towards the rise

-

virtually all medium and large employers (97 per cent and 99 per cent respectively), and the vast majority of small employers (84 per cent), stated that they had automatically enrolled employees into a qualifying pension scheme by late 2017

-

whilst there were early concerns amongst large employers that ongoing administration tasks relating to automatic enrolment could become a burden, attitudes became increasingly positive as rollout progressed and employers became used to the new processes. Most employers interviewed in 2016 and 2018 found the cost and time burden involved with implementing automatic enrolment to be lower than they had initially anticipated

New analysis within this report

-

in 2019, the majority (62 per cent) of private sector employers currently had some form of workplace pension provision, up from 47 per cent in 2017. These organisations employed 94 per cent of all private sector employees

-

in 2019, less than four in ten private sector employers (39 per cent) stated that the introduction of automatic enrolment had resulted in an increase in the total pension contributions that their organisation had to make. However substantial variation existed by employer size

3.1. Employer awareness, understanding and activity

3.1.1. Initial automatic enrolment duties

Automatic enrolment began in October 2012 with the largest employers (250 or more employees) and then continued in a series of stages of decreasing employer sizes until its complete roll out in 2018. Since 2018, the only organisations with initial automatic enrolment duties are ‘newborn’ employers. During the staged rollout of the policy, DWP commissioned a series of qualitative research studies to explore views and experiences of automatic enrolment amongst employers who were implementing the policy at various stages.

Most recently, interim findings from DWP qualitative research with ‘newborn’ employers suggest that individuals responsible for implementing automatic enrolment had typically been aware of the requirement due to their seniority within their current company and previous companies[footnote 27]. These individuals would often hold Human Resources responsibilities.

This research interviewed two groups of ‘newborn’ employers: those who took on their first workers between 2012 and 2017 who were required to implement automatic enrolment by February 2018, and ‘instantaneous newborn’ employers (employers who were required to implement automatic enrolment immediately from October 2017 onwards).

In instantaneous newborns, prior experience of automatic enrolment implementation was even more common. The person responsible for setting it up had usually been employed at a previous workplace when automatic enrolment was introduced. Some employers also mentioned having heard about automatic enrolment in the media ahead of setting it up at their current workplace.

3.1.2. Ongoing automatic enrolment duties

Micro, small and medium employers’ awareness and understanding of their ongoing automatic enrolment duties was assessed in a recent TPR-commissioned report[footnote 28]. There are five ongoing duties for employers (in addition to re-enrolment), which are as follows:

- keeping records of all automatic enrolment activities

- monitoring the ages and earnings of new and existing staff every time they are paid to check whether they are eligible to join the pension scheme

- enrolling staff and informing them as they become eligible to join the pension scheme

- managing requests to join or leave the pension scheme

- paying contributions into the employees’ pension scheme (at the legal minimum contribution rates)

Key findings from the Winter 2019 report included[footnote 29]:

- at least 91 per cent of employers across all three sizes were aware of each of the five individual ongoing duties in relation to automatic enrolment

- as in previous surveys[footnote 30], the majority of employers (82 per cent of micro, 87 per cent of small and 93 per cent of medium) did not report any difficulty keeping up with their ongoing duties. 63 per cent of micro, 63 per cent of small and 70 per cent of medium found them less onerous than expected. Furthermore, almost all the employers were confident that their organisation was fully compliant with its ongoing duties (ranging from 98 per cent to 100 per cent)

- 81 per cent of micro and 91 per cent of small employers interviewed, all of which were in their re-enrolment window at the time, were aware of the re-enrolment requirement

- 74 per cent of micro employers knew that minimum contributions would increase again (in April 2019), compared with 87 per cent of small and 94 per cent of medium employers. This was an increase from the awareness levels seen in Summer 2018 for micro employers (+10 percentage points)

- since TPR’s Summer 2018 report[footnote 31], there were no changes in the percentage of employers who thought the increases in minimum contribution levels in April 2019 were a good idea (54 per cent of micro, 59 per cent of small employers and 75 per cent of medium)

- over half of micro (54 per cent) and small employers (52 per cent) disagreed they would find it difficult to afford the increase minimum employer contributions. 65 per cent of medium employers disagreed, a 10 percentage point increase from Summer 2018

Similar findings were reported in the interim report of DWP’s Automatic enrolment: qualitative research with newborn employers:

- those with an ongoing relationship with an intermediary often asked them to take on the monthly administration of automatic enrolment as part of that relationship, but in rare cases employers were also willing to pay an ad hoc fee for consultative support with understanding their duties and choosing a provider

- employers were typically aware of both the previous April 2018 and the future (at the time of interview) April 2019 increases in contributions, and felt relatively neutral about the rise. Generally, employers said that they were confident about being able to pay these new rates and were relaxed about the cost, which they perceived as a small proportion of their overall costs

- employers were occasionally somewhat concerned about the impact of pension contributions upon general cash flow; though did not typically identify any specific cut-backs that they felt they needed to make in order to afford the ongoing cost of administering automatic enrolment.

3.1.3. Extent of employers’ pension provision

The DWP’s Employers’ Pension Provision (EPP) survey measures the extent and nature of pension provision among private sector employers in Great Britain.

EPP 2017 found that virtually all medium and large employers (97 per cent and 99 per cent respectively), and the vast majority of small employers (84 per cent), stated that they had automatically enrolled employees into a qualifying pension scheme by the time of fieldwork for the survey[footnote 32]. Micro employers were less likely to have automatically enrolled staff (31 per cent), reflecting that only around two-fifths (42 per cent) of micro employers stated they had passed their staging date at the time of interview for the 2017 survey.

Following the last employer staging date in February 2018, all employers are legally obliged to automatically enrol their eligible jobholders into a workplace pension scheme if they are not already in one. The 2019 EPP survey, to be published later in 2020, found that the majority (62 per cent) of private sector employers currently have some form of workplace pension provision (Table 3.1). The proportion of private sector employers with some form of workplace pension provision has risen significantly since the introduction of automatic enrolment. In 2013, this stood at 19 per cent, increasing to just under half (47 per cent) in 2017. A further 15 percentage point increase is observed between 2017 and 2019. In 2019, organisations who have some form of workplace pension provision employed 94 per cent of all private sector employees.

Table 3.1 - Workplace pension provision, by size of organisation, 2013, 2017 and 2019

Private sector employees

| Pension provision | 2013 (%) | 2017 (%) | 2019 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any workplace pension scheme | 19 | 47 | 62 |

| Size of organisation: Micro (1-4 employees) | 9 | 35 | 51 |

| Size of organisation: Small (5-49 employees) | 41 | 89 | 97 |

| Size of organisation: Medium (50-249 employees) | 80 | 98 | 98 |

| Size of organisation: Large (250+ employees) | 96 | 99 | 99 |

Employees working for such employers

| Pension provision | 2013 (%) | 2017 (%) | 2019 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any workplace pension scheme | 76 | 91 | 94 |

| Size of organisation: Micro (1-4 employees) | 8 | 43 | 61 |

| Size of organisation: Small (5-49 employees) | 51 | 92 | 97 |

| Size of organisation: Medium (50-249 employees) | 83 | 98 | 98 |

| Size of organisation: Large (250+ employees) | 99 | 100 | 100 |

Base: All private sector employers as indicated by row headings. Unweighted base for estimates for all employers is 2,948 in 2019, 2,713 in 2017 and 3,043 in 2013.

Note: In 2017 and 2019, ‘Any workplace pension provision’ refers to the provision of an occupational scheme, a GPP scheme, a workplace-based SHP scheme, access to the NEST scheme or access to a Master Trust scheme (other than NEST). It thus excludes contributions to personal pensions. Access to a Master Trust scheme other than NEST is not included in the 2013 figures as this information is not available in the 2013 data.

Source: Employers’ Pension Provision survey 2019.

Splitting the results by employer size, in 2019, 99 per cent of large employers, 98 per cent of medium, 97 per cent of small and 51 per cent of micro employers provided a workplace pension scheme. Since EPP 2017, substantial increases in pension scheme provision have taken place amongst small employers (8 percentage points) and micro employers (16 percentage points). The proportion of medium and large employers providing a workplace pension scheme to their employees has remained almost universal since 2017.

3.1.4. Employers going beyond the minimum requirements

The minimum contribution rate required for employers has increased over time. Initially employers were required to contribute a minimum of one per cent on a band of qualifying earnings, with this increasing to two per cent in April 2018 and to three per cent in April 2019.

EPP 2017 asked employers whether they were phasing in the level of contributions at the time, or whether they were already contributing at least three per cent[footnote 33]. In two-thirds (66 per cent) of schemes used for automatic enrolment, contributions were being phased in, while in around one quarter (24 per cent) of such schemes, employers were contributing at least three per cent from the start. For around one in ten schemes (11 per cent) respondents did not know whether they were phasing in contributions or not. Contributing at least three per cent from the start was more common among micro (30 per cent) and large employers (35 per cent) than small (17 per cent) and medium employers (26 per cent). The most common reason for contributing at least three per cent from the start was that employers wanted to offer a better option for their employees, applying to 44 per cent of such schemes.

DWP’s survey with small and micro employers, conducted at approximately the same time as EPP 2017, found that 21 per cent of these employers offered more than the then-minimum contribution of one per cent[footnote 34].

3.1.5. Pension scheme choice

DWP research with ‘newborn’ (new) employers in 2018 explored the drivers of employers’ decision making when selecting a pension scheme for automatic enrolment[footnote 35]. Whilst previous jobs meant some employers in the study had been involved in selecting a provider before, most were selecting the first pension scheme ever to be offered at their workplace. The research found that these employers often had little knowledge of the providers offering automatic enrolment schemes, or of the differences between providers. This was also a common finding for the small and micro employers interviewed in 2016 as part of research study published the following year[footnote 36].

It was common for newborn employers to spend only a little time researching providers and to consider only one provider seriously. While some employers explained they had considered two or three providers, these were the exception. Employers’ limited research into available providers was typically due to a cautious attitude to compliance, and willingness to follow what they saw as an authoritative recommendation.

The typical decision-making process followed by newborn employers was to choose Nest in the first instance, unless they were prompted to do otherwise by some external factor. Where employers considered an alternative provider to Nest, this was usually triggered by a recommendation from a third party. Research with small and micro employers in 2017 indicated similar approaches. Most of these employers governed their selection of a pension scheme around the schemes ease of set up and use as well as its reliability, often choosing the “safest option” which was seen to be Nest.

Making decisions around which qualifying scheme to enrol members into was slightly less simple for larger employers who staged earlier because some of them already had some kind of pension scheme in place prior to automatic enrolment[footnote 37]. For those employers DWP spoke to staging in 2014 - which were predominantly medium sized - most set up a new pension scheme for automatic enrolment[footnote 38]. Some of these employers used advisers to review other providers, however if the employer took responsibility for reviewing this themselves, the majority tended to describe only looking at new master trusts (e.g. Nest, Now Pensions, The Peoples Pension).

The DWP survey with small and micro employers in 2017 found that 90 per cent of these employers had sought advice or guidance on choosing their new workplace pension scheme[footnote 39]. Most commonly, they approached an accountant or financial services firm (49 per cent), TPR (28 per cent), pension providers (27 per cent), payroll providers (22 per cent), Independent Financial Advisers (IFAs) (18 per cent) or pensions advisers (12 per cent). Nest was the most popular pension provider amongst small and micro employers (chosen by 58 per cent), followed by The People’s Pension (11 per cent) and a range of other providers (each chosen by three per cent of employers or fewer).

3.2. Employer burden and responses

3.2.1. Administrative costs

Recent TPR research[footnote 40] investigated the ongoing financial and time costs of automatic enrolment. Over three-quarters of micro (78 per cent), small (77 per cent) and medium (83 per cent) employers had not incurred any additional ongoing costs in meeting their duties (beyond their staff’s time). For the minority who did pay for support, the median monthly cost varied from £15 for micro employers, £50 for small employers and £100 for medium employers. Both the proportion of employers incurring no additional costs and the median costs for those who paid for support have shown no significant change since the TPR survey of employers in Summer 2018.

The most recent evidence on initial costs of automatic enrolment remains the 2017 EPP survey[footnote 41]. EPP 2017 found that just over half (52 per cent) of employers reported that the introduction of automatic enrolment had resulted in an increase in administrative costs. Around two-fifths (44 per cent) of employers stated that administrative costs had not increased, while the remaining four per cent said that they did not know. Micro employers were less likely to report that administrative costs had increased compared with larger employers; 46 per cent of micro employers reported an increase in administrative costs compared with 62 per cent of large employers.

In 2017, small and micro employers (the group that were then staging) were asked how much it cost to implement automatic enrolment in a separate DWP survey[footnote 42]. The median level of cost reported was £400: £200 for micro employers (one to four employees) and £500 for small employers with up to 29 employees.Around a third (35 per cent) of micro employers and one fifth (20 per cent) of small employers reported zero cost to implement automatic enrolment.

3.2.2. Contribution costs

Evidence from DWP’s series of qualitative research studies on automatic enrolment suggest that employers’ attitudes towards contribution costs have remained fairly consistent throughout the policy’s implementation period.

Generally, large employers interviewed in 2013 felt relatively able to accommodate the employer contribution costs[footnote 43]. However, for those with large workforces who were not previously enrolled in a workplace pension, the cost of ongoing employer contributions was sometimes substantial enough for them to want to delay taking on that cost for as long as possible.

Research with employers staging in 2014[footnote 44], and with small and micro employers in 2016[footnote 45] found that some employers anticipated they’d need to think about measures to reduce costs as employer contributions rose. Employer contributions could also be seen to represent more of a financial burden for smaller organisations. However, such concerns were rare among newborn employers interviewed in 2018: these employers did not typically identify any specific cut-backs that they were planning to make in order to afford the cost of administering automatic enrolment in future[footnote 46].

Newborn employers were typically aware of both the previous April 2018 and the future April 2019 increases in contributions, and generally said that they were confident about being able to pay these new rates.

The 2019 EPP survey found that less than four in ten private sector employers (39 per cent) stated that the introduction of automatic enrolment had resulted in an increase in the total pension contributions that their organisation had to make[footnote 47]. Significant variation existed by employer size. In 2019, 27 per cent of micro employers reported experiencing an increase in total pension contributions, compared with 78 per cent of small employers, 83 per cent of medium employers and 82 per cent of large employers.

3.2.3. Responses to costs incurred through implementing automatic enrolment

EPP 2019 investigated what actions employers had taken to absorb increased contribution costs, if they reported that these costs had increased as a result of automatic enrolment. The most common action reported was that these costs had been absorbed as part of other overheads (68 per cent). The next most common responses were that employers had: taken a reduction in profits (52 per cent) or increased prices (13 per cent). Only seven per cent of employers who reported experiencing increased costs as a result of automatic enrolment said they had implemented lower wage increases, six per cent said they had changed an existing pension scheme and five per cent reported restructuring or reducing their workforce to absorb these costs. Just one per cent of employers had reduced contribution levels for existing members prior to the reforms. 15 per cent of employers reported adopting none of the stated actions to absorb increased contribution costs.

Overall, the most common actions employers report taking have remained at similar levels since the 2017 EPP survey. Table 3.2 shows employers’ strategies to absorb increases in total pension contributions, by size of organisation in 2019.

Table 3.2 - Employers’ strategies to absorb increase in total pension contributions, by organisation size (per cent)

Size of organisation (employees)

| Employers’ strategies | Micro (1-4) (%) | Small (5-49) (%) | Medium (50-249) (%) | Large (250+) (%) | All private sector employers reporting an increase in contributions (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbed as part of other overheads | 68 | 68 | 64 | 61 | 68 |

| Reduction in profits | 52 | 54 | 51 | 41 | 52 |

| Increased prices | 10 | 17 | 18 | 14 | 13 |

| Lower wage increases | 3 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 7 |

| Changed existing pension scheme | 4 | 7 | 15 | 12 | 6 |

| Re-structured/reduced workforce | 3 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Reduced contribution levels for existing members prior to reform | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| None of these | 16 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 15 |

| Unweighted base | 187 | 909 | 362 | 669 | 2,127 |

Source: Employers’ Pension Provision survey 2019.

3.2.4. Employer views and attitudes on the level of burden

The previously mentioned series of DWP qualitative research studies conducted with employers throughout the implementation of automatic enrolment included asking questions about any associated burdens employers may face.

Early qualitative research with large employers[footnote 48] indicated that ongoing administration could become a burden for employers when they were required to identify and process large numbers of new workers on a regular basis. However, research conducted in 2014[footnote 49] found that employers implementing at the time commonly expected the administrative tasks to get quicker and easier as they became more accomplished at running these processes. Some employers who had initially perceived implementing automatic enrolment to be complex and time-consuming indicated a change in their attitudes since completing the process, becoming more favourable to the idea now the pension was in place.

A 2016 study of small and micro employers[footnote 50] suggested that most employers found the cost and time burden involved with implementing automatic enrolment to be lower than they had initially anticipated, a view echoed by newborn employers in a 2018 study[footnote 51]. In 2018, newborn employers typically measured the amount of time given over to complying with their duties in hours, rather than days or weeks and were rare to express any concern about the expected burden to be placed on them by the ongoing administration of automatic enrolment.

A recent TPR survey[footnote 52] found that the majority of employers (82% of micro, 87% of small and 93% of medium) did not report any difficulty keeping up with their ongoing duties. Since the survey begun in Winter 2017, this proportion has remained in excess of 80% across all employer sizes. In the latest survey, around two-thirds of employers (63% of micro, 63% of small and 70% of medium) also said that they found their duties less onerous than expected.

4. Impact of automatic enrolment on individuals and saving

This chapter looks at the impact that automatic enrolment has had on individuals and the amount being saved in workplace pensions. This relates to the following evaluation strategy questions:

Has automatic enrolment increased the number of individuals saving in workplace pensions, and if so, how? (EQ3)

Has automatic enrolment increased the amount being saved in workplace pensions, and if so, how? (EQ4)

Summary

Existing evidence

-

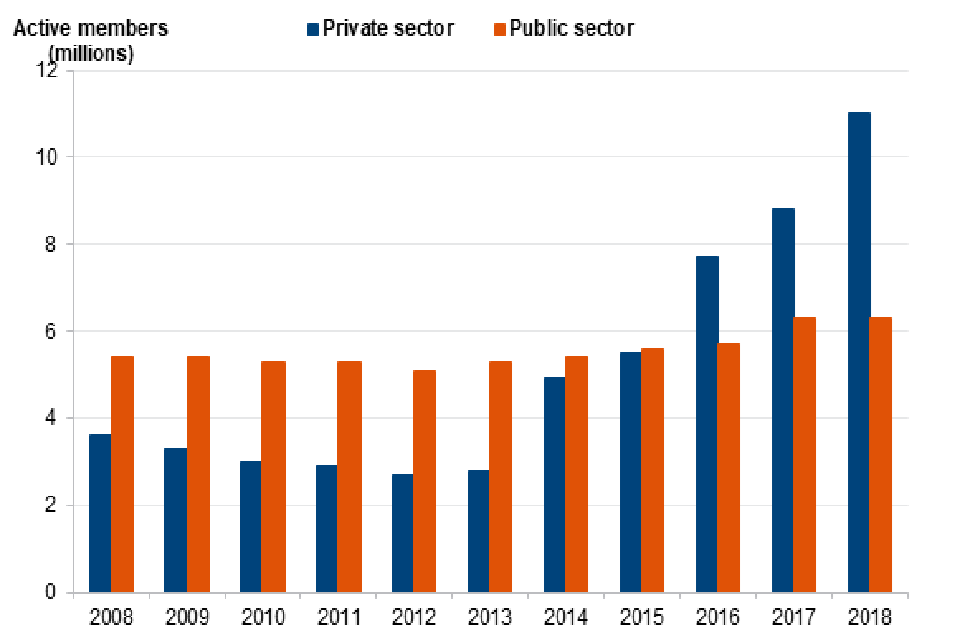

data collected up to 2018 found that the number of eligible employees participating in a workplace pension has increased to 18.7 million (87 per cent), up from 10.7 million (55 per cent) in 2012

-

the annual total amount saved on behalf of eligible employees across both sectors stands at £90.4 billion in 2018, which is an increase of £7 billion from 2017. Annual total amounts increased in both public and private sectors from 2017. The public sector increased by around £2.5 billion and the private sector by £4.5 billion

New analysis within this report

-

the proportion of workplace pension savers who made an active decision to stop saving (including opt-out and cessation) shows a slight increase from the 2018/19 financial year to the first quarter of the 2019/20 financial year (0.72 to 0.76 per cent), following the second increase of the automatic enrolment minimum contribution rates. Despite this slight increase, the overall rate remains low

-

from April 2018 onwards, the period in which the increases to minimum contribution rates took place, the largest increases in rates of stopping saving (due to active decisions) were observed among those aged 22 to 29 and 30 to 39 (0.23 percentage points and 0.15 percentage points respectively). These increases are modest but notable relative to other age groups where the changes observed are negligible

-

between April 2014 and June 2019, the average active decision stopping saving rate was slightly higher for males (0.76 per cent) than for females (0.59 per cent)

-

throughout the implementation period of automatic enrolment, the cohort opt-out rate has remained consistently low. Overall, among employers with a scheme used for automatic enrolment, nine per cent of employees who were automatically enrolled in the 2018/19 financial year (prior to the April 2019 minimum contribution rate increase) decided to opt out within one month. This rate remained at the same level as in 2016/17

-

findings from the DWP’s communications tracking research (April 2019 wave) found that the majority of individuals interviewed viewed automatic enrolment as a good thing for them personally (79 per cent); agreed saving into a workplace pension was normal for them (77 per cent); and knew where to go if they wanted to find more about workplace pensions (75 per cent)

-

evidence from the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey indicates that “social norming” of workplace pensions has occurred across all eligible age groups and occupational classifications<

-

in 2018, the number of employees contributing two per cent or above to a workplace pension (as a proportion of their reported pensionable pay) was almost 10.3 million following the first increase in the minimum contribution rates in April 2018. In 2017, this number stood at approximately 6 million

-

eligible employees in the private sector with total contributions above the 2018 minimum are more likely to belong to older age brackets, have higher earnings and work for larger employers. However, the proportion belonging to younger age brackets, with lower earnings and working for smaller employers has increased significantly over time

-

in April 2018, the number of employees receiving employer contributions of two per cent or above (as a proportion of their reported pensionable pay) increased to over 9.4 million after the first increase in the minimum contribution rates in April 2018. In 2017, this number stood at approximately 7 million

-

in April 2018, the number of eligible private-sector employees who were making contributions sufficient to meet the 2019 minimum requirements had risen to approximately 6.4 million. A further 6.9 million may have needed to increase contributions to meet the 2019 minimum requirements

4.1. Trends in workplace pension participation

This section looks at measures indicating the effects of automatic enrolment on increasing the number of savers participating in workplace pensions. The Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) analysis of the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) data estimates the pension participation trends of eligible employees[footnote 53], [footnote 54] over time. This is broken down according to public and private sector, employer size, employee earnings, and certain protected groups (gender, age, disability and ethnicity)[footnote 55]. The DWP Family Resources Survey (FRS)[footnote 56] provides specific characteristic breakdowns that are not accounted for by ASHE.

Together these annual surveys can monitor shifts in workplace pension participation since the reforms were introduced. The most recent ASHE data including pension information[footnote 57] were collected with reference to April 2018, showing significant increases in participation and pension saving. The FRS data were collected throughout the 2017/2018 financial year. Therefore any potential impact of automatic enrolment may be lessened, in the FRS data, because not all employees will have been automatically enrolled at the time due to the staged implementation approach[footnote 58].

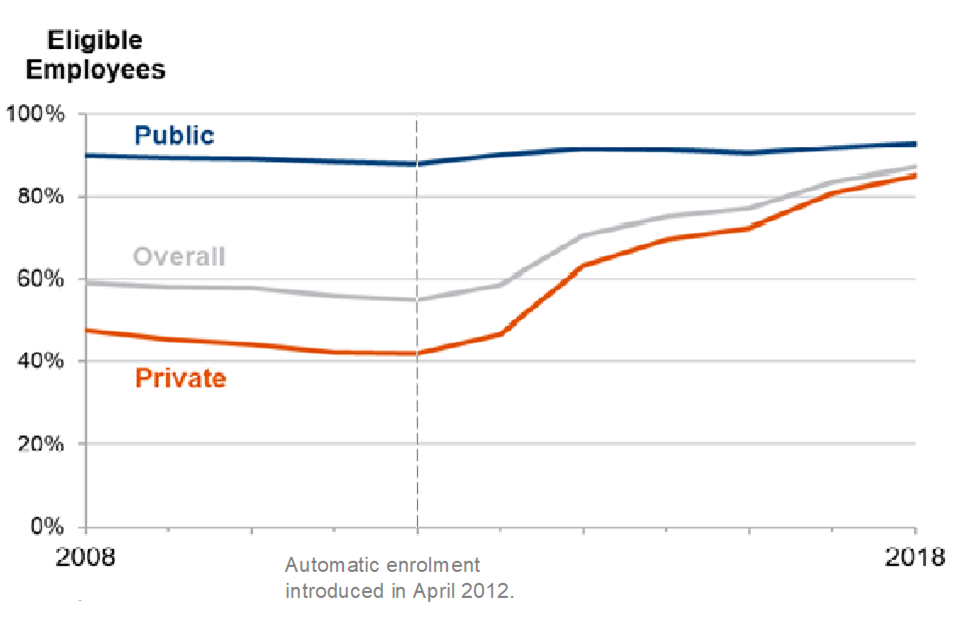

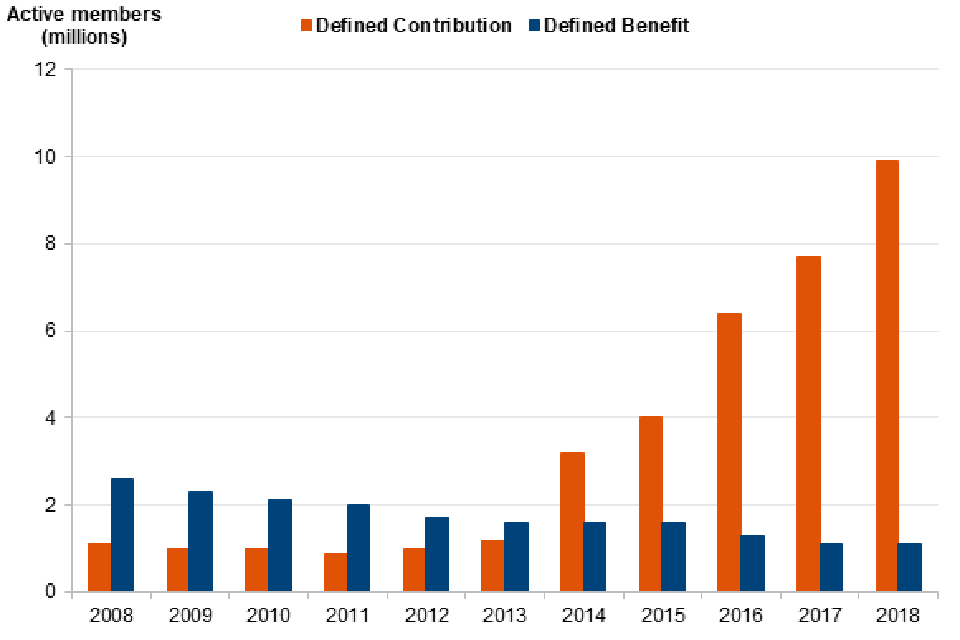

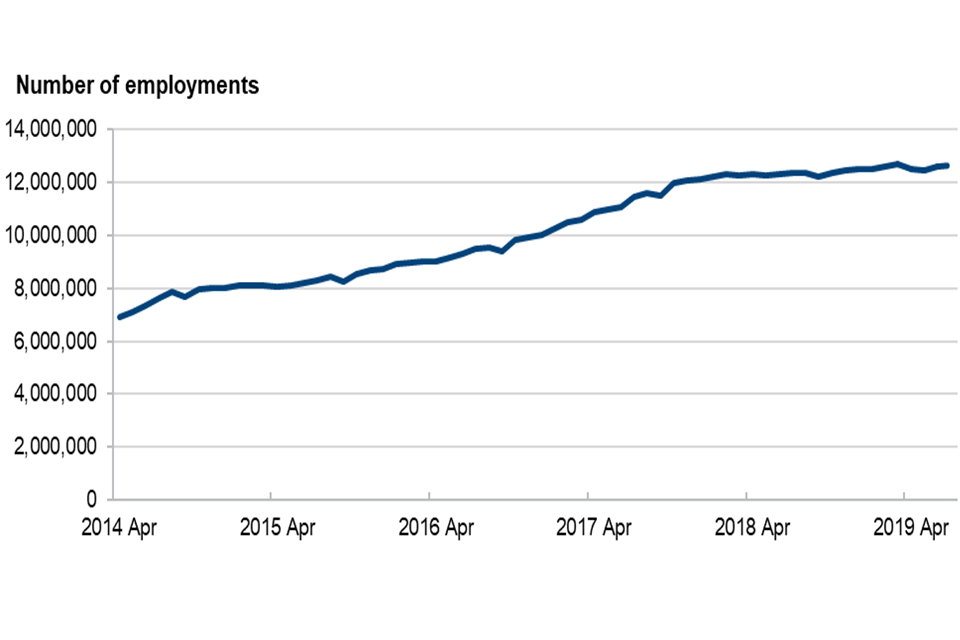

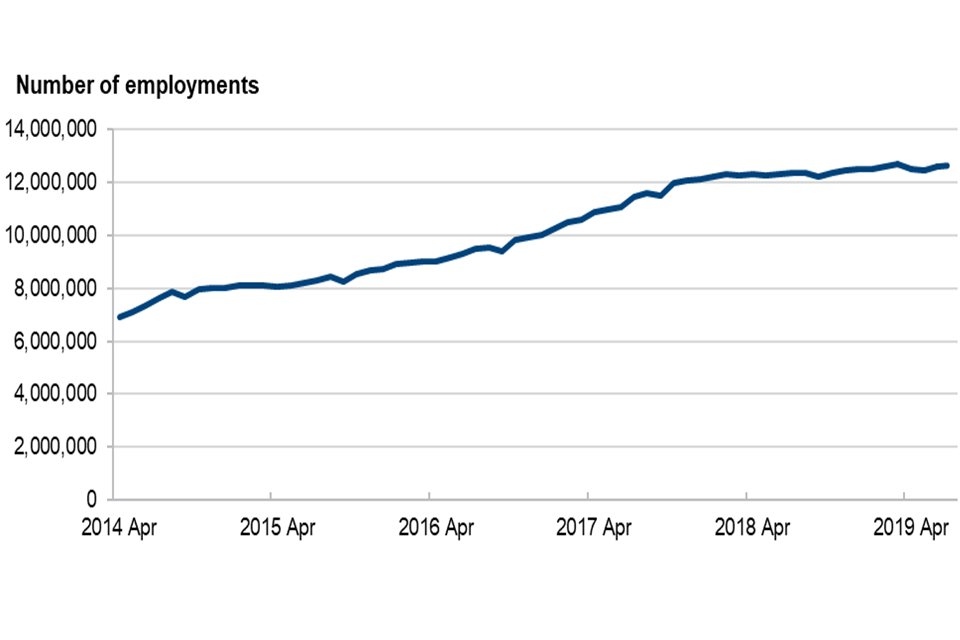

4.1.1. Overall number of savers

Between 2008 and 2012 there was a general downward trend in workplace pension participation, from 59 per cent (11.8 million eligible employees) to 55 per cent (10.7 million). However, since the reforms there has been a significant increase in the number of eligible employees participating in a workplace pension, up to 87 per cent (18.7 million) in 2018. Figure 4.1 illustrates trends in workplace pension participation for eligible employees by sector over time. Public sector pension participation remained high in 2018 at 93 per cent (4.9 million employees), an increase of five percentage points since 2012. Within the private sector, participation has increased by 43 percentage points since 2012, up to 85 per cent of eligible employees participating (13.9 million) in 2018.

Figure 4.1 - Eligible employees participating in workplace pensions, by sector

Source: DWP estimates derived from the ONS ASHE, GB, 2008–2018.

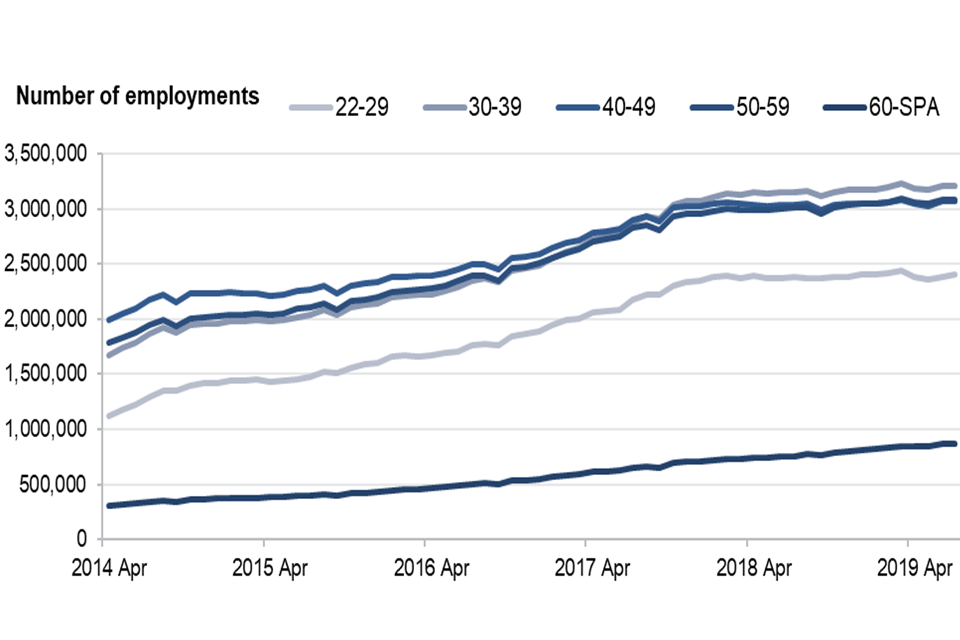

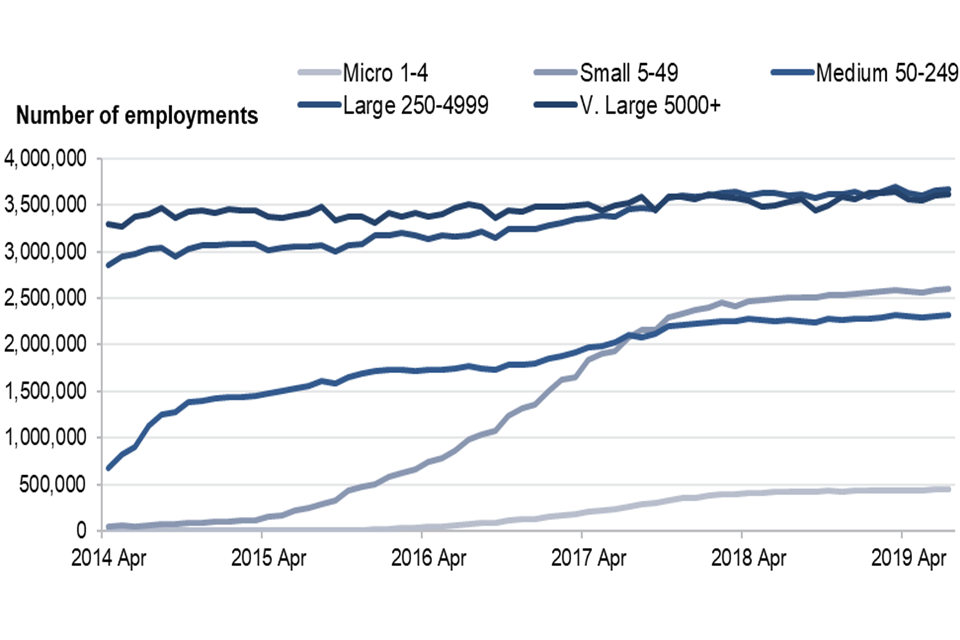

4.1.2. Employer size

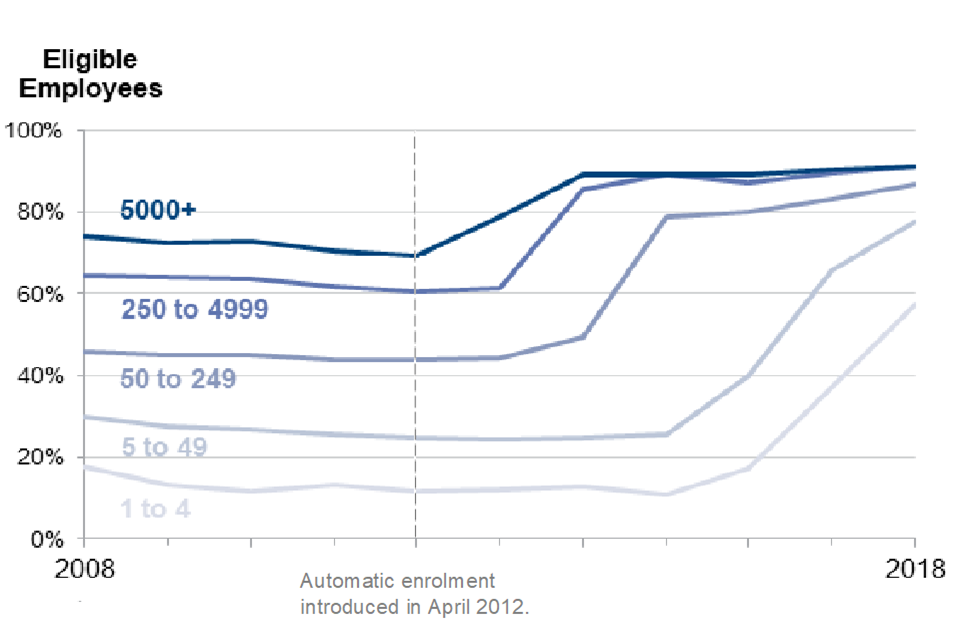

Figure 4.2 displays the proportion of eligible employees participating in workplace pension schemes by employer size. In 2018, the largest employers (5,000 or more employees) and second largest employers (250 to 4,999 employees) had the highest participation rate at 91 per cent, compared with 58 per cent for micro employers (one to four employees). This may historically be explained by the high proportions of employees working for large public sector employers where participation rates have always been high, whereas, the more recent increases correspond with the staged implementation of automatic enrolment which began with large employers.

Figure 4.2 - Eligible employees participating in workplace pensions, by employer size

Source: DWP estimates derived from the ONS ASHE, GB, 2008–2018.

Overall, participation amongst eligible employees in 2018 was 87 per cent for those with 50 to 249 employees and 78 per cent for those with five to 49 employees (an increase of 13 percentage points since 2017). Increases in participation clearly align with the staging profile for implementing automatic enrolment, with the largest increases in participation from 2016 to 2018 being amongst the small and micro employers, who were undergoing staging during this period.

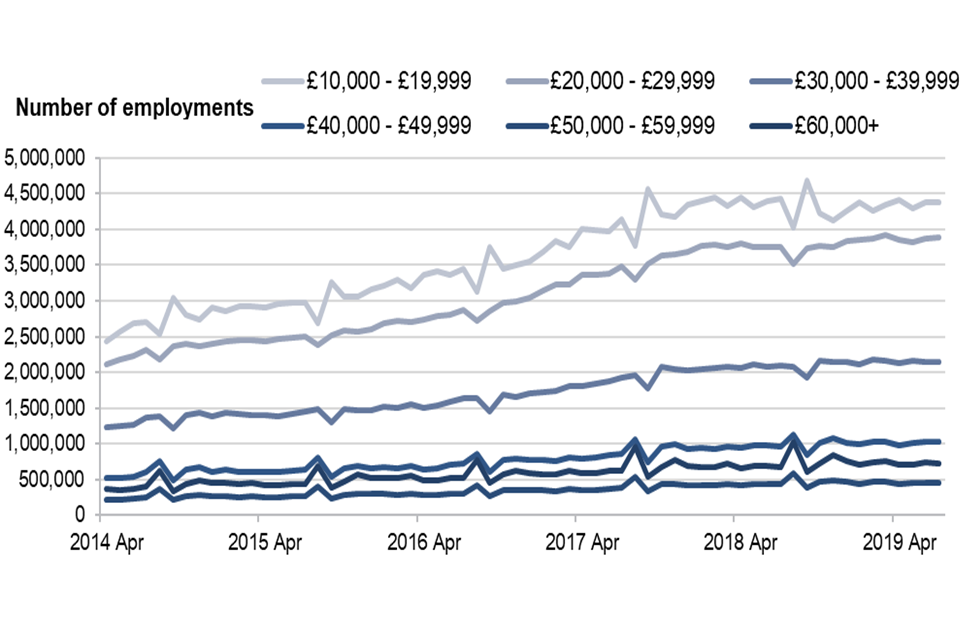

4.1.3. Earnings

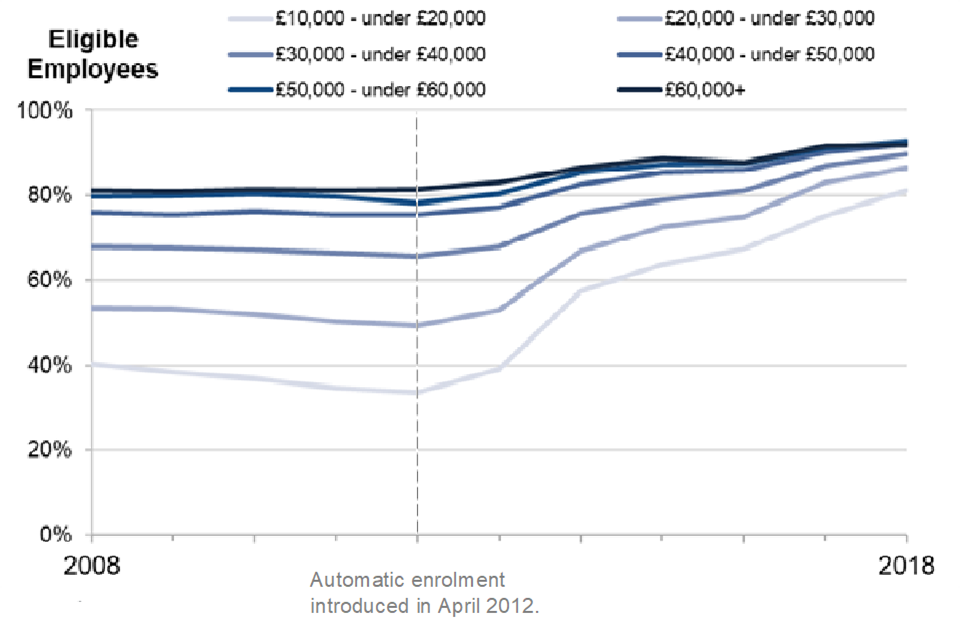

Figure 4.3 shows the relationship between pension participation and earnings. Those who earn £50,000 to £60,000 have the highest participation levels at 93 per cent, with participation being high in the upper income brackets of £40,000 to £50,000 as well as £60,000+ at 92 per cent in 2018. However, the introduction of automatic enrolment has seen larger increases in participation amongst lower earners. For example, those earning between £10,000 (the level of the earnings trigger for automatic enrolment from 2014/15 to present for 2019/2020) and £20,000 had a workplace pension participation rate of 81 per cent as of 2018, an increase of 47 percentage points since 2012. As a result, the differences in participation rates between earning bands have narrowed since 2012.

Figure 4.3 - Eligible employees participating in workplace pensions, by gross annual earnings

Source: DWP estimates derived from the ONS ASHE, GB, 2008–2018.

4.1.4. Gender

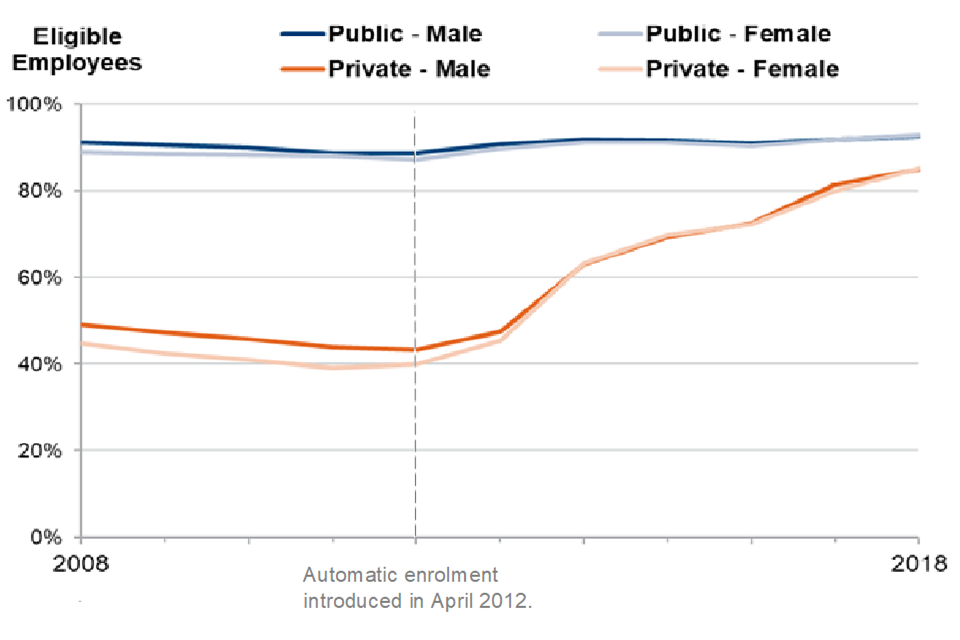

Figure 4.4 illustrates pension participation by gender and sector. Overall, women have higher participation rates than men (88 per cent compared to 86 per cent)[footnote 59]. In the public sector in 2018, participation was 93 per cent for both men and women.

Figure 4.4 - Eligible employees participating in workplace pensions, by gender and sector

Source: DWP estimates derived from the ONS ASHE, GB, 2008–2018.

Since the introduction of automatic enrolment, the private sector has seen the largest increases in participation, and in 2018 women and men had equal participation rates at 85 per cent. This represents an increase of 42 percentage points for males and 45 percentage points for females since 2012.

4.1.5. Age

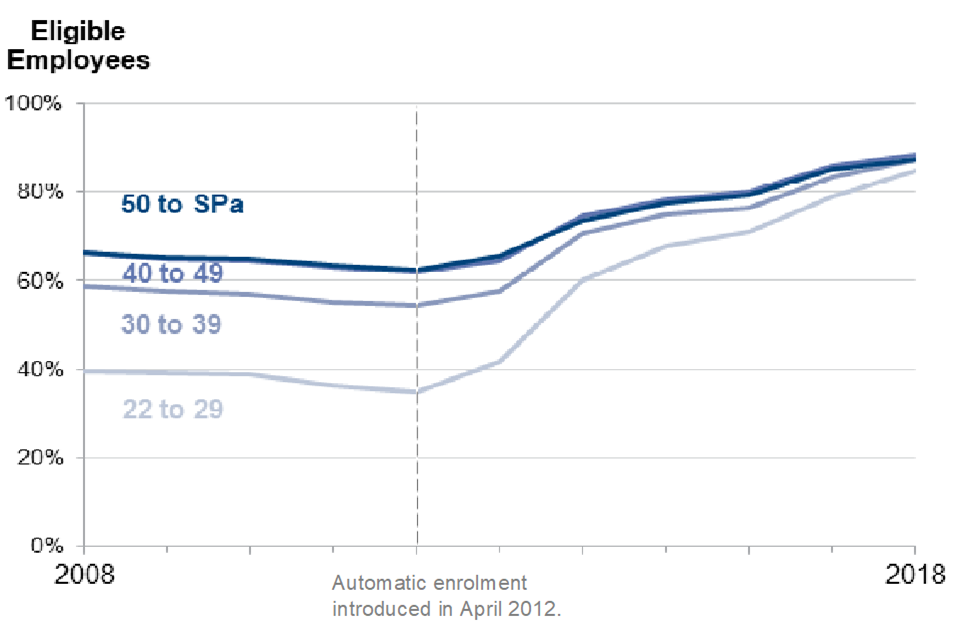

Figure 4.5 shows pension participation of eligible employees by age group. Overall, participation remained the highest for older employees, although in recent years there have been significant increases in participation amongst younger age bands, and as a result, substantial convergence in participation levels between age bands.

Figure 4.5 - Eligible employees participating in workplace pensions, by age band

Source: DWP estimates derived from the ONS ASHE, GB, 2008–2018.

The largest increase between 2012 and 2018 was in the youngest age band; those aged 22 to 29 saw a 50 percentage point increase in participation to 85 per cent. All other age groups also saw an increase over the same period; participation for those aged 30 to 39 increased by 33 percentage points to 87 per cent; for those aged 40 to 49 there was a 26 percentage point increase to 88 per cent; and for those aged between 50 and State Pension age (SPA) participation increased by 25 percentage points to 87 per cent.

4.1.6. Economic status

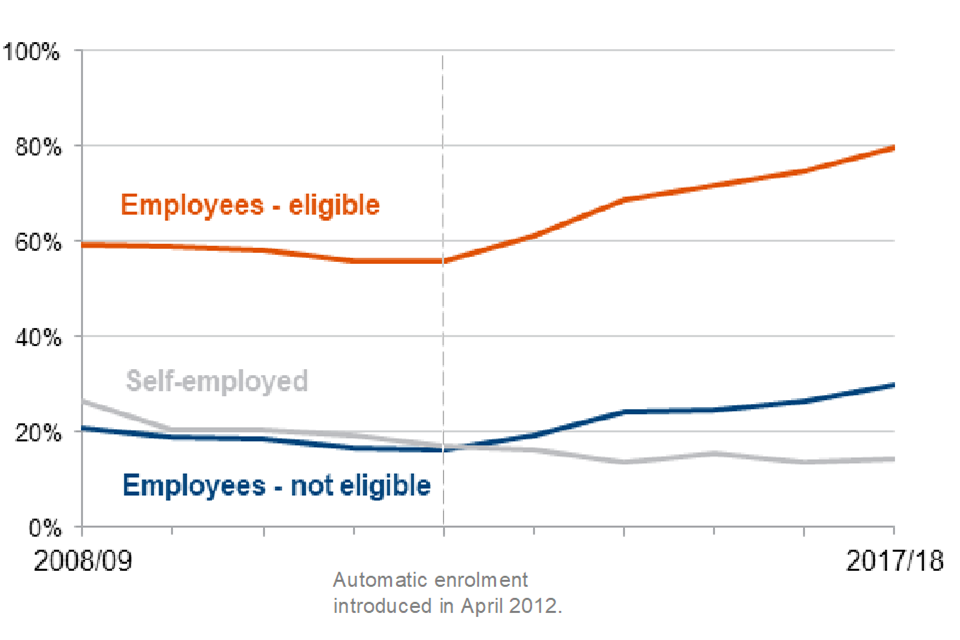

Figure 4.6 shows changes to pension participation for eligible employees compared to non-eligible employees and the self-employed. Participation of eligible employees increased from 56 per cent in 2012/13 to 80 per cent in 2017/18, reversing the decline in participation seen prior to automatic enrolment.

Figure 4.6 - Participation in all pensions, by economic status

Source: Modelled analysis derived from the FRS, UK, 2008/09 to 2017/18

Participation of non-eligible employees has increased from 16 per cent in 2012/13 to 30 per cent in 2017/18. In contrast, participation of self-employed workers has declined by 12 percentage points since 2008/09, falling to 15 per cent in 2017/18[footnote 60]. Self-employed workers are not captured by automatic enrolment[footnote 61]. Other categories remained relatively stable, with participation of unemployed and inactive workers extremely low as would be expected.

4.1.7. Disability

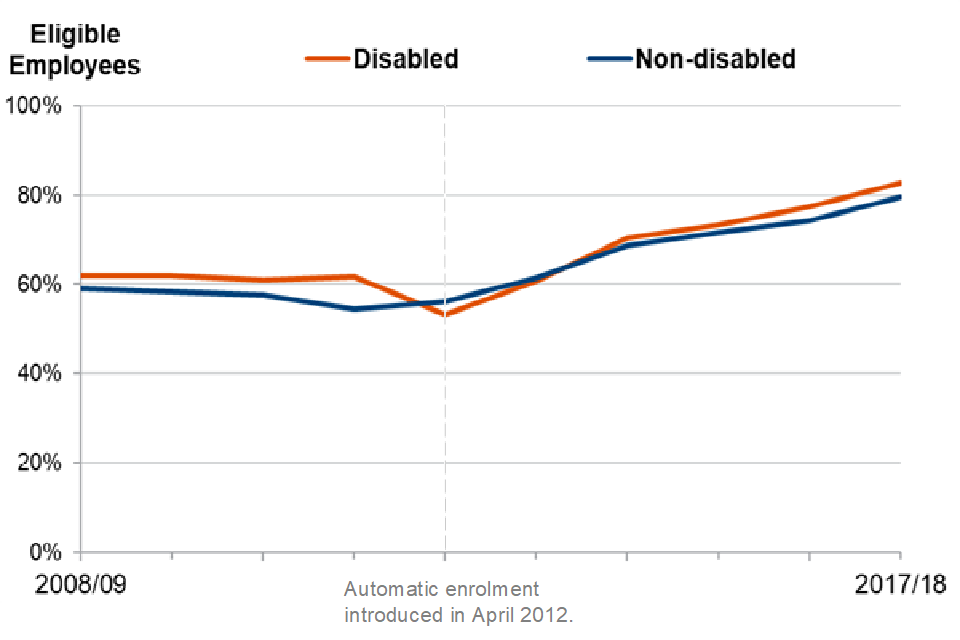

Figure 4.7 shows trends in pension participation for disabled and non-disabled employees. In 2017/18 there was a small difference between these groups: the participation rate for disabled employees was 83 per cent (an increase of 30 percentage points from 2012/13), and 80 per cent for non-disabled employees (an increase of 24 percentage points from 2012/13).

Figure 4.7 – Eligible employees participating in workplace pensions, by disability

Source: Modelled analysis derived from the FRS, UK, 2008/09 to 2017/18.

Note: Impairment types changed 2012/13 - caution needed.

4.1.8. Ethnicity

This presents trends in the pension participation rate by ethnic group. The White ethnic group still had the highest participation rate of 76 per cent in 2015/16-2017/18, this was in line with the overall participation rate of 76 per cent across all groups over this three-year period. Between the 2011/12-2013/14 period and 2015/16-2017/18 there were large increases amongst all ethnic groups. The Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic group showed the largest increase from 36 per cent to 60 per cent (24 percentage point increase). In comparison the lowest increase over the same period occurred in the Mixed ethnic group. This group saw a 17 percentage point increase from 53 per cent to 70 per cent.

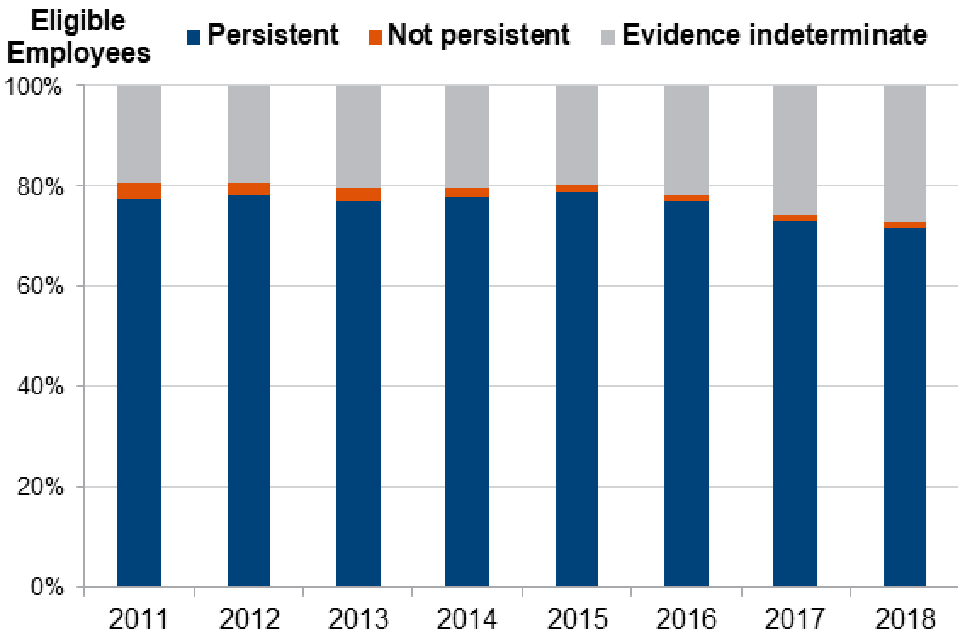

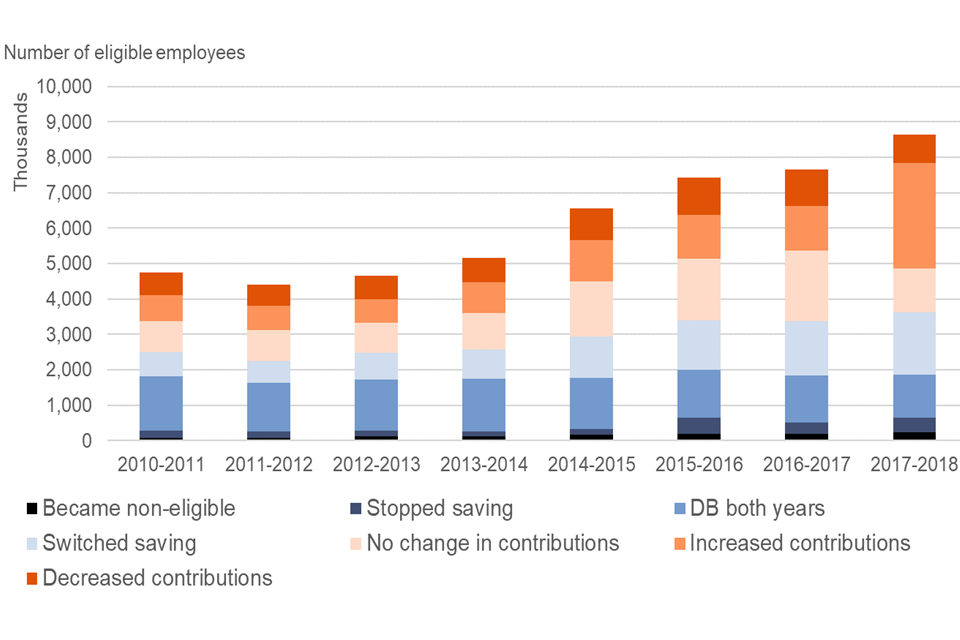

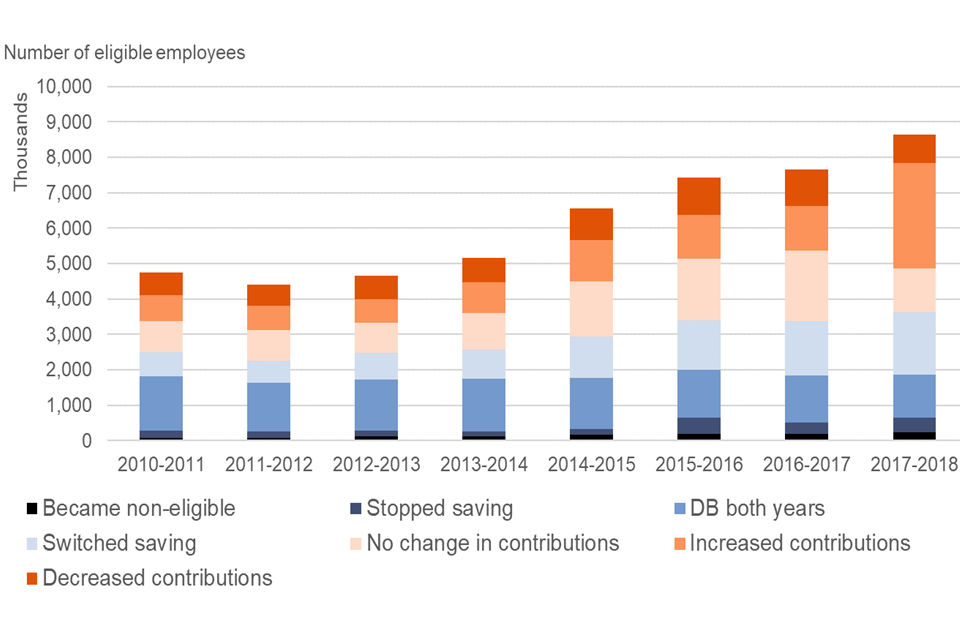

4.1.9. Persistency of saving