50,000 Nurses Programme: delivery update

Published 7 March 2022

Applies to England

Introduction

In 2019, the government committed to increasing the numbers of registered nurses in the NHS in England by 50,000 by the end of the Parliament. This update sets out more detail about the programme, including:

- progress so far

- plans for meeting the target

- uncertainties, risks and mitigations

- next steps

It also sets out the definition, scope and timing of the target.

The figures in this update set out the planning assumptions for how the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), working with national partners, intends to achieve the target. The numbers should not be taken as precise estimates, as contributing factors will change over the remainder of the programme: they are planning assumptions against which an iterative programme will adapt as more information becomes available.

This uncertainty and flexibility is reflected in the ranges for each recruitment route. While these represent our current high, central and low estimates and therefore illustrate our plausible range at this stage, they are subject to change. As such, we have also included information on mitigation plans if particular components of the programme do not impact as hoped, or if unanticipated risks arise.

This update is also intended to serve as our response to the Public Accounts Committee (PAC), who requested more information on how the 50,000 target is expected to be met. The conclusion from the PAC was that “We are not convinced that the department has plans for how the NHS will secure 50,000 more nurses by 2025”.[footnote 1]

Overview of the programme

The 50,000 Nurses Programme is overseen by a programme board chaired by the Minister of State for Health, Ed Argar. It includes senior membership from DHSC, NHS England/Improvement (NHSEI), Health Education England (HEE) and HM Treasury. It meets every 2 months to monitor progress, identify issues and intervene where necessary. The programme is split into 3 broad areas – domestic recruitment, international recruitment and retention of existing staff.

Definition and timing

The 50,000 target is based on the following.

Definition

All nurses working in the NHS in England, including in GP settings are included in the target. This covers all NHS providers across acute, community, mental health and ambulance settings. It does not include non-NHS providers, including social care providers and social enterprises, though we would expect these sectors to benefit indirectly as the numbers of nurses trained increases overall. For GP settings, it covers all nurses employed in general practice. While there are other nurses working across the health and care system, we have chosen this definition so we can track the number of nurses working in the NHS via an NHS digital published dataset with a long time series.

What counts

The programme has adopted full-time equivalent (FTE) nurses as its core currency. This means that if a nurse works part time, they will count as less than one nurse (with the number depending on the degree to which they are part time). As some nurses work part time, the programme will need more than 50,000 additional nurse headcount to meet the 50,000 target.

What does not count

While nursing associates are a career progression to become a registered nurse they do not count towards the 50,000 target. Additionally, midwives, allied health professions and health visitors are not part of the registered nurse expansion work.

Timing

The baseline for the target is numbers of FTE nurses in the NHS as of 30 September 2019, reflecting the timing of the manifesto commitment in the 2019 General Election. The programme is committed to meeting the target by 31 March 2024.

Therefore, by 31 March 2024, the government is working to ensure there are at least an additional 50,000 FTE nurses in place in NHS providers and GP settings, compared to September 2019. Given lags in when data is available, confirmation of whether the target has been achieved will be in May or June 2024.

Information on progress on the target is available via public data releases. The most recent data is published by NHS Digital.[footnote 2] To achieve the target, the NHS will need to recruit more than 50,000 FTE nurses. This is because between September 2019 and March 2024, we expect significant numbers of nurses to leave the workforce, either temporarily (for example, for maternity, for career breaks or because they are transferring to providers not covered by the target), or permanently (for example, retirement). The numbers required are set out in more detail below.

Overview of the target

As of September 2019, there were 300,904 FTE nurses working across NHS providers and GP settings (excluding health visitors). This is made up of:

- 284,552 FTE nurses in NHS providers

- 16,352 in GP settings[footnote 3]

This means that by 31 March 2024, the programme is aiming to ensure at least 350,904 FTE nurses are employed across the NHS.

As of December 2021, 27,003 more FTE nurses are working in the NHS than in September 2019, giving a total of 327,907 FTE.[footnote 4] This places the programme well on the way to meeting the target, although much remains to be done and there are significant risks and uncertainties.

Breakdown of numbers into workstreams

Three overall workstreams contribute to the 50,000 target:

- domestic recruitment – this includes:

- preregistration undergraduate and postgraduate students

- reducing preregistration nurse attrition

- degree nurse apprentices

- conversions from nursing associates and assistant practitioners to registered nurses

- nurse return to practice

- international recruitment: bringing in overseas-trained nurses to the NHS from abroad

- retention: encouraging existing nursing staff to stay in the NHS, and reducing the leaver rate

Each of these workstreams is anticipated to make a significant contribution to the 50,000 target, but there is some uncertainty within each about how each will perform over the timeframe of the programme. While the programme has made assumptions about the anticipated impact of each workstream, the outcomes from each carry inherent risk. Therefore, the programme has developed ranges for how many nurses each workstream is expected to deliver, as set out below.

Table 1: actual and projected additional FTE nurses by workstream, 2019 to 2020 to 2023 to 2024

| Cumulative trajectories | September 2019 to March 2020 (actual) | 2020 to 2021 (actual) | 2021 to 2022 (projected) | 2022 to 2023 (projected) | 2023 to 2024 (projected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | 8,000 | 21,000 | 35,000 to 36,000 | 50,000 to 54,000 | 68,000 to 75,000 |

| International | 8,000 | 19,000 | 28,000 to 33,000 | 39,000 to 46,000 | 51,000 to 57,000 |

| Retention | 1,000 | 4,000 | 3,000 to 5,000 | 2,000 to 7,000 | 3,000 to 9,000 |

| Wider labour market | 6,000 | 12,000 | 18,000 to 18,000 | 23,000 to 23,000 | 29,000 to 29,000 |

| NHS leavers | -13,000 | -31,000 | -51,000 to -51,000 | -72,000 to -71,000 | -93,000 to -91,000 |

| Other movement | -1,000 | -4,000 | -9,000 to -8,000 | -13,000 to -12,000 | -17,000 to -16,000 |

| Total | 9,000 | 20,000 | 24,000 to 33,000 | 30,000 to 46,000 | 42,000 to 61,000 |

In the table above:

- all figures are cumulative from the start of the programme

- figures for 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 are now finalised, so no ranges are included

- figures for 2019 to 2020 are from the end of September 2019 to the end of March 2020. All other figures, both actual and projected, are for full financial years

- ‘domestic’, ‘international’ and ‘retention’ refer to the 3 main workstreams. ‘Domestic’ refers to domestically trained nurses, with no further breakdown of domestic routes provided. All are anticipated to provide net contributions to the target

- ‘wider labour market’ includes nurses joining from elsewhere in the labour market. This includes those coming in from other provision that is not included in the target, for example social care, non-NHS community provision or private provision. This is expected to make a net contribution to the target

- ‘NHS leavers’ is the total number of nurses leaving the NHS, and as such is taking away from the target. This includes retirements, as well as people moving to roles in health and social care outside of NHS providers

- ‘other movement’ covers:

- nurses who leave for and return from parental or carer’s leave

- nurses increasing or reducing the hours they work (so changing the headcount-FTE conversation)

- nurses moving into non-nursing roles within the NHS, for example management roles

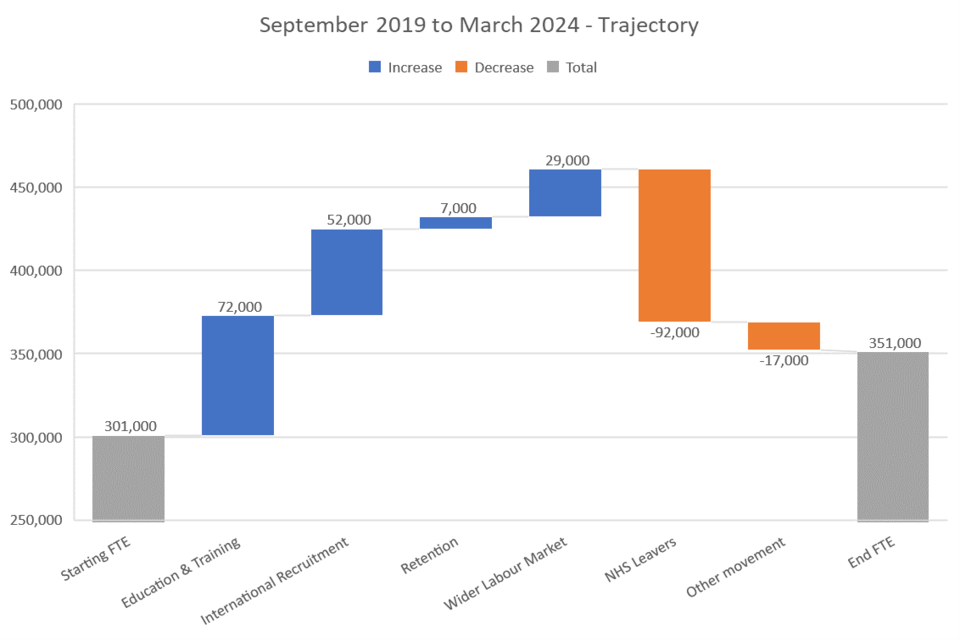

We currently estimate that by March 2024, the programme will have delivered between 42,000 and 61,000 additional FTE nurses, based on current plans. The central scenarios within the overall range are set out in chart 1. Please note that while these are the central scenarios, the ranges set out in table 1 are a better reflection of how the programme is anticipated to progress over time given the prevailing uncertainties. Chart 1 is therefore used for illustrative purposes to set out how the joiners and leavers add up to at least 50,000. Plans have been developed for how to respond if the risks around meeting the target materialise, to ensure the target will be met.

Chart 1: expected flow of FTE nurses, September 2019 to March 2024

Chart 1 describes how nurses will enter the NHS workforce as part of the 50,000 Nurses Programme. There are significant increases coming from education and training (72,000), international recruitment (52,000), retention (7,000) and wider labour market (29,000). Decreases will come from NHS leavers (-92,000) and other movement (-17,000). The starting number of full-time equivalent nurses was 301,000 and the aim is to get this to 351,000.

The central scenario has an additional 51,000 nurses across the workforce by March 2024, compared with September 2019 (note that numbers may not add precisely due to rounding). As such, the programme is currently on target to deliver at least an additional 50,000 nurses by March 2024, though there are plausible scenarios where, based on current plans, the programme could fall short. Plans for responding to such scenarios are covered in the following section.

Annex A sets out more detail on exactly how the overall numbers can be broken down into the main workstreams.

While there are no regional targets as part of the overall 50,000 Nurses Programme, we have included a breakdown of progress so far by region. This is set out in Annex B.

Uncertainty and risk

The figures above set out best estimates at this stage, based on the information currently available. They are based on a set of assumptions across each of the workstreams. In some cases, these assumptions are very well founded and drawn from significant precedent (for example, the proportion of undergraduate nursing students who go on to work in the NHS).

Other assumptions are more uncertain due to a lack of data or precedent (for example, the numbers of nurses who may choose to leave the profession over the coming period as a result of the impact of the pandemic). Therefore, we have brought together all of the available information to generate ranges around each central scenario for each workstream, as set out in table 1.

Domestic supply

The programme has robust data and information available relating to people who have started across the various courses that provide routes in to nursing, including undergraduate and postgraduate courses, nursing apprenticeships and conversion courses from nursing associates or assistant practitioners. Data shows that 2019 and 2020 saw strong enrolment on preregistration nurse courses; these students will count towards the 50,000 target, assuming they graduate and join the NHS. In addition, there were just over 2,050 postgraduate nursing students who started their studies in 2021 to 2022 who will count towards the March 2024 target end date.

However, what is less certain at this stage is how many will complete their courses and go on to employment that is covered by the target. Reasons for this include:

- attrition (the proportion of students leaving courses)

- delays to becoming nurses (some students may choose to have a break after studies before embarking on their career)

- where newly qualified nurses will choose to be employed (not all nursing roles are covered by the target, for example social care, private healthcare and non-NHS community service providers)

- conversion from headcount to FTE (not all newly qualified nurses will work full time)

For some of these assumptions, for example where newly qualified nurses tend to be employed or the conversion from headcount to FTE, the programme has good information based on history. For others, such as attrition, the unprecedented nature of the pandemic and the impact it has had on student nurses is less certain. In response, work is ongoing to support students and apprentices through their studies, which has been well received. However, while it reduces the risk of higher attrition, it does not remove it, so there remains some uncertainty about overall numbers coming through this route.

International

DHSC and NHSEI have provided trusts with part of the funding required for international recruitment, enabling trusts to recruit nurses and help those nurses to settle. As such, it is more straightforward to predict international recruitment numbers than it is for other workstreams across the programme.

The variation in figures from the low to the high scenario represents trusts’ ability to continue to expand international recruitment of nurses, available supply of nurses overseas (supply in more specialist areas such as mental health is more challenging) and funding available.

While the pandemic has disrupted some of the international flows of nurses into the country, this challenge proved to be both temporary and surmountable. Flexible policy solutions were introduced to ensure nurses could still travel, while maintaining effective quarantine arrangements, and while some countries restricted health staff leaving early in the pandemic, this has since eased. As such, the programme does not anticipate major future issues on international recruitment for the rest of the programme, though it does remain a possibility and is kept under constant review.

Retention

Retention is the most significant area of uncertainty across the programme. It is also the area of greatest complexity, with a multitude of contributory factors. Some of these, such as working conditions, are within the control of the NHS. Others, such as the attractiveness of outside careers, are not. While for domestic training and international recruitment there is relative certainty about the numbers of people who are starting training courses or travelling to England to work, for retention performance is determined by the individual decisions of around 350,000 individual nurses. Further, there are confounding factors that make accurate predictions of leaver rates difficult to judge.

The first of these factors is the pandemic. The last 21 months have been some of the most challenging in the history of the NHS, and many staff have been placed under sustained and severe pressure which will have an impact on their attachment to nursing. While a wide range of measures to support staff were put in place during the pandemic, some staff will reassess their longer-term careers in light of the challenges they have faced, or reassess their lifestyle and decide that a career in the NHS is no longer for them.

The leaver rate has been low since the start of the pandemic. While the general trend in leaver rates over recent years has been downwards, partly as a result of the retention programme run by NHSEI, they were at historic low levels in 2020 to 2021. In part, this will be due to some staff postponing leaving decisions, including career change and retirement, to help with the NHS pandemic response. These people may well leave during the remainder of the programme, which would temporarily increase the leaver rate. For others, despite the pressures that it brought, the pandemic may well have strengthened their attachment to the NHS by highlighting the extraordinary public value that it has brought to individual patients and to society as a whole.

There is also the outcome of the McCloud remedy, which allows some staff to retire on more favourable terms than was previously anticipated to be the case. This is an unknown quantity, as it is difficult to predict individual responses to the judgement. It is anticipated that in the short term, and during the remainder of the programme, this could serve to temporarily increase the leaver rate.

DHSC and NHSEI are looking to address these uncertainties to encourage nurses, as well as all other staff groups, to remain in the NHS. This includes through:

- health and wellbeing initiatives, including self-help apps, tools and guidance for managers to support their teams

- expansion of occupational health and mental health support, including the introduction of 40 mental health and wellbeing hubs

- expansion of flexible working

- greater focus on career development

However, some nurses will leave and, given the unprecedented nature of the factors causing the uncertainty, there is significant variation around the anticipated impacts.

Dealing with the uncertainty and risk

While the programme is currently on target to achieve 50,000 additional nurses, there are plausible planning scenarios where it could fall short. As such, it is important to have a plan for what can be done to respond in such an event.

It takes time to train a nurse:

- undergraduate nurses typically take 3 years to qualify

- postgraduate nurses typically take 2 years to qualify

- nursing associates and assistant practitioners typically take 2 years to convert to a nurse

- nurse degree apprentices typically take 4 years to qualify

As such, if the programme needed to respond rapidly to changing circumstances that risk falling short of the target, training new domestic nurses is not a viable route to do so. Instead, the programme would need to consider:

- further action to improve retention (noting that it is an area of significant uncertainty itself)

- international recruitment (it takes 3 to 9 months to bring in an international nurse, on average)

- return to practice (though numbers here are limited)

- reducing attrition from student courses

Of these, the route that offers the greatest certainty and flexibility is international recruitment. As part of the programme, DHSC and NHSEI have therefore developed plans to expand international recruitment at short notice, should it be required.

Annex A: data and definitions

The overall 50,000 target will be assessed against published NHS Digital statistics. However, the published statistics do not show flows from different routes. In order to break down the headline figures, further analysis has been carried out on data from the Electronic Staff Record (ESR), which includes some assumptions about which nurses that enter or leave the NHS are assigned to which flows. This annex sets out the key assumptions.

The projections in this document are produced by HEE, NHSEI and DHSC. This modelling rolls forward existing trends in leavers and joiners for different professions, with the assumed impact of additional interventions added in. The scope of the analysis is based on:

- profession: nurses in Hospital and Community Health Services (HCHS) and GP settings. This excludes health visitors and registered midwives

- geography: NHS trusts, clinical commissioning groups and primary care only (though primary care is not on ESR). Exclusions include commissioning support units, arm’s-length bodies and independent community interest companies

- status: active assignment, acting up, internal secondment only

Different types of flows contribute towards nurse stock change, as described in chart 1 and table 1. Although data shows nurses joining the NHS, it does not directly measure where they join from. Because of this, a number of assumptions have been made to establish an appropriate approximation. Joiners and leavers to the NHS nurse workforce are assigned to one of the following flows:

-

Education and training: this aims to capture newly qualified joiners directly from education. Within this analysis, staff are counted in this flow if they are new to ESR, have a UK nationality, and join at the lowest spine point of band 5 of the NHS Agenda for Change pay scale.

-

International recruitment: this aims to count nurses who have moved to the UK and are employed in their first NHS job in England. In the analysis this flow includes both:

- nurses joining from outside the NHS with overseas (non-UK) nationality

- nurses with non-UK nationality who were on another non-nursing subset occupation code and then moved to a nursing occupation code at the lowest spine point of Agenda for Change band 5. These are included because many international recruits briefly work as healthcare assistants before their nursing registration is confirmed

-

Wider labour market: nurses are assigned to this flow if they are joining from outside the NHS with UK/unknown nationality and are not at the lowest pay banding spine point. We assume these will be ‘experienced hires’ from the wider labour market including nurses joining from private providers.

-

NHS leavers: numbers leaving the NHS, that is not appearing on ESR in the next relevant time period. The numbers in chart 1 and table 1 are based upon the expected number of NHS leavers assuming the leaver rates are at 2019 levels. This attempts to forecast NHS leavers in the absence of the retention programme.

-

Retention: this is the expected number of additional nurses who will remain in the NHS due to the retention programme.

-

Other movement: a net flow which includes:

- nurses leaving active duty to go on maternity leave (these will not be included in NHS Digital Statistics)

- nurses who remain in the NHS but move to non-nurse occupations (for example, nurses who become managers)

- the impact of nurses who reduce their hours of work (so their corresponding FTE falls)

- increases in nurse numbers returning from maternity leave or increases in working hours (these increases are netted off the other falls)

Primary care data

Nurses within GP settings excluding trainee nurses are included within the scope of the 50,000 target. The data available on nurses in GP settings is not as rich as the data on nurses in NHS trusts, and is collected via a different method and source. This means the flows in and out of the GP nurse workforce cannot be modelled in the same level of detail. Given that the number of nurses in GP settings is relatively small compared to the number in NHS trusts, this is unlikely to change the overall conclusions of this analysis.[footnote 5]

Annex B: regional breakdown of progress

The table below sets out how nursing numbers have changed since September 2019, the start of the 50,000 nurses period, for each of the NHS regions. Please note that the regional breakdown is only available until November 2021, whereas the national figures quoted in the main body are available for December 2021. As such, while the figures are similar, they will not directly correspond.

| HCHS and GP nurses | September 2019 | November 2021 | Change September 2019 to November 2021 | Percentage change September 2019 to November 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East of England | 28,654 | 31,516 | 2,862 | 10.0% |

| London | 54,036 | 58,363 | 4,326 | 8.0% |

| Midlands | 55,532 | 60,196 | 4,664 | 8.4% |

| North East and Yorkshire | 49,935 | 53,641 | 3,706 | 7.4% |

| North West | 46,070 | 50,277 | 4,207 | 9.1% |

| South East | 38,887 | 43,677 | 4,790 | 12.3% |

| South West | 27,789 | 30,396 | 2,607 | 9.4% |

| Total | 300,904 | 328,065 | 27,162 | 9.0% |

-

In July 2020, the Public Accounts Committee conducted a review of the nursing workforce. The NHS nursing workforce report was published on 23 September 2020. ↩

-

NHS workforce statistics. The relevant data file is the ’NHS Workforce Statistics, England Provisional Statistics’, which contains a row showing ‘Nurses in HCHS and GP settings (excluding Health Visitors)’. This is the definition against which the target is being measured. ↩

-

NHS workforce statistics. The relevant data file is the ’NHS Workforce Statistics, England Provisional Statistics’, which contains a row showing ‘Nurses in HCHS and GP settings (excluding Health Visitors)’. This is the definition against which the target is measured. ↩

-

NHS nurse numbers tend to fall from March to August, and then see increases through September and October as student nurses enter the labour market. ↩

-

See more information on the General Practice Workforce collection, including NHS Digital work reviewing its methodology. ↩