A First Hand Account of VJ Day by Vic Knibb

Second World War veteran Sergeant Vic Knibb, 90, tells us his story of serving in the Far East, what VJ Day means to him and why geese, not dogs, are man’s best friends.

Vic Knibb Profile Picture

Vic Knibb on his time in Burma

“I joined the Home Guard at the age of 16 and signed up to the Army in Derby in early 1943. I was 18.

In early 1944 I boarded a troopship at Liverpool docks, destination unknown. It wasn’t until we reached the Suez Canal that we realised we were heading towards India.

On our arrival in Bombay I saw bananas for the very first time and it wasn’t long before I was trading cigarettes for them! We were quickly transported to a transit camp called Deolali. You’ll probably recognise the name from the famous phrase “gone doolally” or “doolally tap”. People said if you spent too much time there you lost your mind a bit. It was an unpleasant place. Thankfully we were only there for a month before we caught a train to Calcutta.

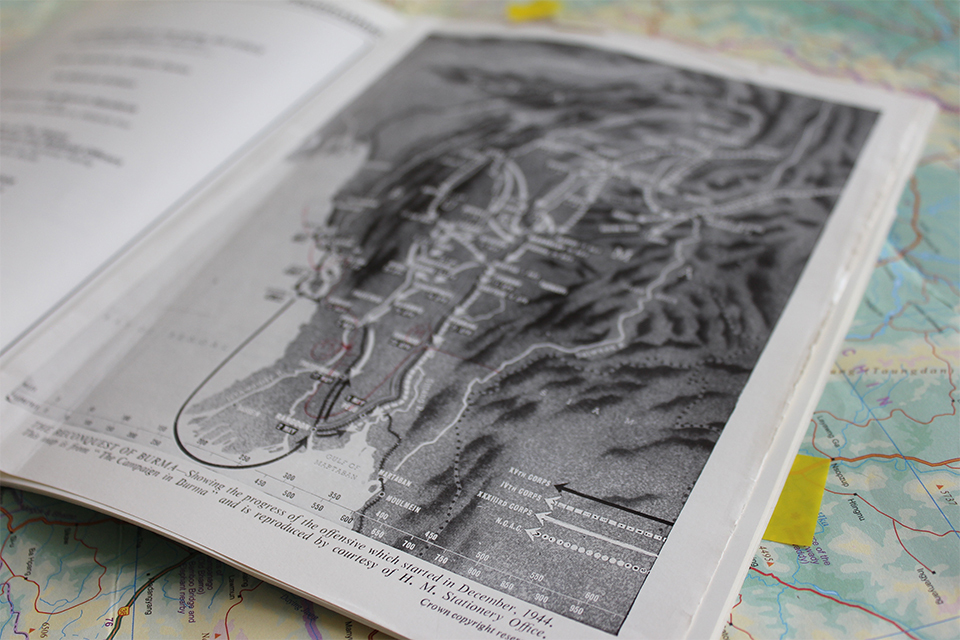

A map of Myanmar (formerly Burma).

From Calcutta we moved on to Imphal. There I found out I was joining the Royal West Kent Regiment. Later I was told they’d just fought in the Battle of Kohima, one of the bloodiest and most important battles fought in the Far East. At Imphal I won a week of leave in Calcutta at a sports day event. There I stayed in a Museum and was hosted by a local British family who kindly took me under their wing. There was a swimming pool at their house, which was quite something! I was used to having to look after myself so it was nice to be taken care of.

After I re-joined my Batallion we headed through the mountains into North Burma towards Mandalay and served at the Battle of Meiktila (January – March 1945).

Finding food, water and somewhere safe to sleep were the most important things for us. Learning to adapt to the conditions was important. From checking water supplies for dead bodies to finding villages that kept geese (they were useful intruder alarms and helped us to get a good night’s sleep), we did our best to stay alive.

From Mandalay we continued to fight our way down to Rangoon for the next five months.

We’d often divert off the roads into villages to check for any Japanese in retreat. It became clear the main difference between us was that they were happy to die. This was disconcerting when they were running at you with grenades in their hand, content with blowing you and themselves up. We wanted to live.

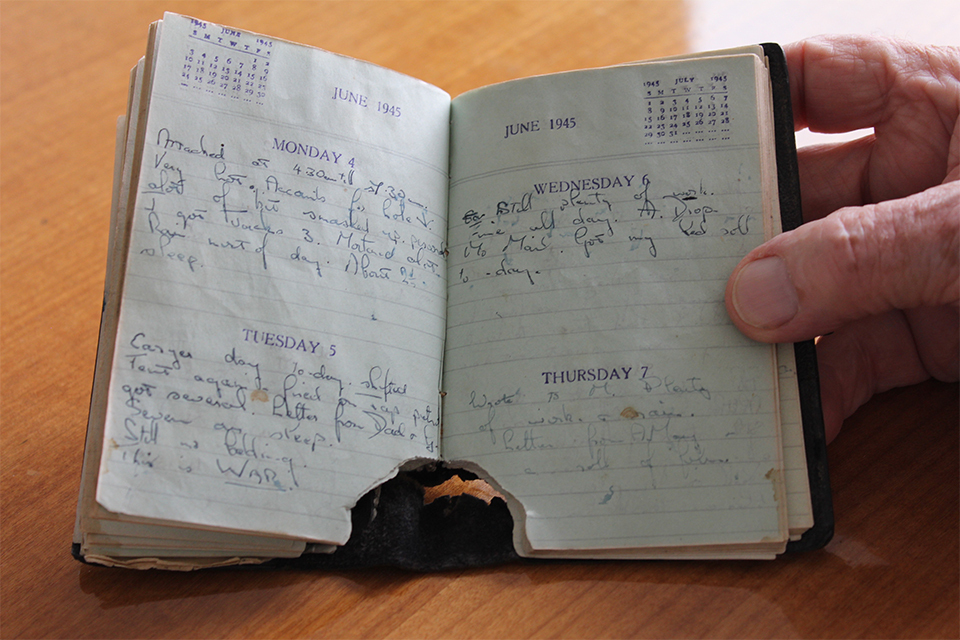

Vic wrote in his diary on a daily basis. The chunk missing is from a bullet fired at him when he came into contact with the Japanese.

Many of my fellow soldiers fell by injury or illness. I was one of the fit ones but by the time we reached the South I was covered in sores. I’d been living off half rations for 2 ½ months. By the time we reached Rangoon I’d developed jaundice. A few of us snuck out one night to find supplies and we bumped into a doctor. He took one look at me and said “you’re off to the hospital” - I refused. Instead I went to sleep and the doctor ended up scratching the yellow pus out of my hand, elbow, neck and knee. He gave me some medicine and with food and ammunitions we headed back to the Battalion.

In Rangoon we were told the war was over and that was that. We had nothing to celebrate. We kind of just wandered about looking for food.

We were always thinking about food. A memory that sticks with me is one night whilst manning the Rangoon docks I smelt bread. I shouted up to the ship “Have you got bread up there?” a man replied with “of course” I replied, “Give us a loaf”. It was one of the finest bits of food I’ve ever had, a hot, white loaf of fresh bread thrown down from the ship. I hadn’t had bread for two and a half years. We didn’t have it out there. It was fantastic.

The Japanese surrendered on August 14 1945 and it was announced by Imperial Japan on 15 August and the surrender was formally signed on September 2. When the Japanese arrived to formally surrender in Burma I was selected to man the Japanese peace talks. I had to take the sword off the fifth Japanese solider off the plane. I spent the next few days manning the conference room and made sure I was well presented. My memory of the conference is limited, I imagine our brains were focussing on getting fed and rested.

People often ask me if I was relieved at the end of the war? The sense of relief came slowly for us. We were worried about what was going to happen to us. Fighting a war was all some of us knew. I found it difficult. I started labouring but I was 21/22, had no training and wasn’t used to working. It was a difficult time of my life when I came back.

Vic's beret and his service medals.

Nowadays VJ Day means a lot to me. There are 37,850 dead young men from across the Commonwealth in Burma. I’ve been to their cemeteries. The loss of life was huge and the ferocity of the fighting was grave. VJ Day is our chance to remember those that didn’t make it back. After all without them we may not be here today.”

More information about how veterans and descendants can register to attend the events in London for VJ Day 70 can be found here.