Online Advertising Programme consultation

Updated 25 July 2023

This consultation document was published on 9 March 2022.

Ministerial foreword

Julia Lopez MP

Advertising is at the heart of the digital economy. It is a key revenue source for many online businesses, underpinning the provision of key services that are positively transforming people’s lives and helping consumers discover valuable new products and services at remarkable speed. The UK advertising sector is leading the way, creating more accessible and low cost routes for businesses to engage with customers, and continues to be the largest market in Europe for advertising.

As digital technologies continue to underpin our economy, society and daily lives, we have committed to ensuring that the rules governing them keep pace, while driving sustainable growth and unlocking innovation. These technologies have served as an incredible catalyst for change - not least during the COVID-19 pandemic where the public has relied on them more than ever before - but also in the way that they boost prosperity and productivity across the economy.

The advertising landscape is dynamic and increasingly focused on digital channels. Regulating online advertising, and the internet, is challenging because of the speed with which it changes. Online advertising remains the fastest growing area of advertising globally, having grown exponentially over the last decade. While this brings significant benefits to businesses and consumers, it also carries risks and potentially damaging consequences, including illegal fraudulent adverts and legal but harmful adverts such as those which mislead and target vulnerable groups.

The Online Advertising Programme will review the regulatory framework of paid-for online advertising to tackle the evident lack of transparency and accountability across the whole supply chain. It will consider how we can build on the existing self-regulatory framework, by strengthening the mechanisms currently in place and those being developed, to equip our regulators to meet the challenges of the online sphere, whilst maintaining this government’s pro-innovation and proportionate approach to digital regulation. We want to ensure that regulators have good sight of what is happening across the vast, complex, often opaque and automated supply chain, where highly personalised adverts are being delivered at speed and scale.

This review will work in conjunction with the measures being introduced through the forthcoming Online Safety Bill, as well as those this government is developing to address competition and data protection issues across the online landscape. Seeking to complement the online safety legislation being implemented to regulate user-generated content, the Online Advertising Programme will look specifically at paid-for online advertising to ensure holistic cover across the online content that can create harm for consumers and businesses alike. While the Online Safety Bill will introduce a standalone measure for in-scope services to tackle the urgent issue of fraudulent advertising, this Programme will ensure that other organisations across the supply chain play a role in reducing the prevalence and impact of fraud, in addition to the spectrum of wider illegal and legal harms created by online advertising.

Market participants across the online advertising ecosystem, from advertisers to publishers and all those in between, have a collective responsibility to tackle the harms created to our society, particularly young and vulnerable people. The government wants to move away from a model which focuses on holding advertisers accountable, to deliver a holistic, cross-sector approach which looks at the roles of each actor in the ecosystem and how they can facilitate the minimisation of harm. Our goal is to unpick the intricacies in the market to develop a regime that enables each actor to contribute to this objective, and ultimately create a more sustainable system which people can trust.

This consultation presents an opportunity to build on the UK’s leading position in the international digital market and make our creative industries as globally competitive as possible.

Julia Lopez MP

Minister of State for Media, Data and Digital Infrastructure

Executive summary

In 2019, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport announced that it would consider how online advertising is regulated in the UK. In 2020, we ran a call for evidence focusing on online content and placement standards, before carrying out a formal consultation. The purpose of this consultation on the government’s Online Advertising Programme (OAP) is to set out the government’s understanding of the online advertising ecosystem and highlight some of the priority areas of concern. The document also sets out a number of options for reform that the government is considering, and on which we would be keen to hear your views.

This government is pro-innovation and recognises that digital technologies play a significant role in our economy and society. However, as they underpin more of our daily lives, we need to ensure that appropriate governance is put in place that keeps pace with the speed of growth across digital markets. The digital landscape has grown relatively organically over the past decade or so, in which time online advertising has transformed the way in which most adverts are disseminated. Through the OAP, the government seeks to review the overall regulatory architecture of online advertising to ensure that regulators have the right powers and tools at their disposal to regulate and minimise existing and arising harms. This is consistent with the approach that the government is taking in a number of other related areas such as online safety, cyber security, data policy and digital competition.

This Online Advertising Programme intends to complement the government’s work to establish a pro-competition regime for digital markets. There will also be significant interactions between the Online Advertising Programme and the government’s Online Safety Bill in relation to tackling fraudulent paid-for advertising. The OAP plans to build on this work by seeking to provide a holistic review of the whole ecosystem for online advertising, examining the role of actors across the supply chain in creating a transparent and accountable market. We will continually examine the interdependencies and overlaps between this review and other regulatory initiatives across government and industry to ensure consistency and coherence in our approach, in line with the government’s Plan for Digital Regulation published in July 2021.

Online advertising has emerged rapidly and has come to dominate advertising globally, creating opportunities not only for businesses but also for consumers. Through this evolution, online advertising has also come to play a critical role in the monetisation of the internet and the ability of consumers to access myriad online services - from search to social media to online news provision - for free. It has fundamentally redrawn how businesses and consumers interact and is a key driver in the digital economy, generating vast flows of revenue. In this role, it provides affordable, scalable and targeted advertising for relatively little investment, enabling small and independent businesses throughout the UK to find audiences cheaply and efficiently.

Rapid growth has, however, presented challenges for the regulation that governs online advertising. As a result, a spectrum of both legal and illegal harms have arisen which are impacting on the trust in and sustainability of the market. These current, new and emerging harms have wide-reaching impacts, which have in turn reduced consumer confidence in online advertising. A recent study has shown that trust in advertising has fallen dramatically over the last few decades, with 70% of people in the UK having stated that they do not trust a lot of what they see on social platforms, including posts from brands. This lack of trust in turn threatens to undermine the overall sustainability of the market.

The harms that we have identified can broadly be divided into harmful content of adverts and harmful placement or targeting of adverts - and this harm can be further exacerbated when harmful content is targeted at vulnerable groups. Although targeting can bring benefits for both businesses and consumers as more relevant advertising is served, it also carries risks and highlights concerns regarding how data is being used. Responses to the 2020 call for evidence showed that consumers are finding some advertising practices intrusive, with some feeling that they are ‘stalked’ around the internet. Consumer groups such as Which? and Money Mental Health have also highlighted that targeting can hone in on vulnerable individuals based on algorithmic technologies.

The prevalence of harmful content and targeting is driven by the complexity of online advertising market dynamics, including the presence of two core factors: a lack of transparency and a lack of accountability. Transparency issues are driven by the opaque, complex and automated nature of the online supply chain, which, alongside the scale, speed and targeted nature of online advertising dissemination, makes it difficult for businesses, the public or regulators to understand who is viewing which type of advert, when, and with what impact. This is compounded by the issue of accountability in the online supply chain, where many of the actors involved in distributing advertising content are not consistently held to account under existing regulatory frameworks.

Platforms and intermediaries generally have their own governing principles, terms of service and community guidelines. While they do have certain obligations under consumer law - for example, under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 (CPRs) - there are often limited obligations on them to share information relating to monitoring, performance and propriety, and these are not standardised practice across industry. Whilst recognising the advancements made by those actors across the ecosystem who strive to achieve better industry standards, community accreditations and guidelines often do not have full industry participation and are not independently verified or enforced by an external regulatory body. Many larger platforms also offer ‘self-service’ advertising buying services, which can require little vetting for advertisers and create a low bar to entry for new players in the market. As a result, bad actors often operate with relative impunity, using online advertising as a means to perpetrate fraud or advertise other illegal or legal but harmful products and services, with limited oversight.

At present, online advertising is not subject to the same level of regulation as other media such as TV and radio. Whereas in broadcast advertising, licences can be revoked where there are serious breaches there are no equivalent sanctions for those that host harmful content online. The vast majority of TV and radio adverts are also pre-cleared before they are broadcast, whereas for online advertising the absence of a broadly equivalent body means that harmful adverts may be served before they have a chance of being rejected.

The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) has taken on an important role in developing innovative approaches to the regulation of advertising, which for the majority of advertising online holds advertisers primarily responsible for the creative content, media placement and audience targeting of their ads. The ASA also places responsibilities on others involved in preparing or publishing marketing communications, such as agencies, publishers and other service suppliers, to comply with their UK Code of Non-Broadcast Advertising and Direct & Promotional Marketing (the ‘CAP Code’). This secondary responsibility recognises that whilst parties involved in preparing or publishing adverts have a role to play in tackling irresponsible adverts, there are limited circumstances in which online service providers are held by the ASA to exercise primary control over the creative content and audience targeting of adverts. It is clear, however, that transparency and accountability needs to be spread across the supply chain, so that intermediaries, platforms, and publishers in the open display market can also play a greater role in the regulation of online advertising, which helps monetise their services.

We have outlined a number of options for the level of regulatory oversight that could be applied across the supply chain in order to bind in other actors and ensure that we improve transparency and accountability in the ecosystem. The level of regulatory oversight that could be implemented ranges from a continuation of the self-regulatory framework through to full statutory regulation. A self-regulatory approach would involve relying on the ASA’s existing framework enforced through their codes, including the new Online Platforms and Networks Standards (OPNS) proposal that they are developing to bring consistency to the way in which actors in the supply chain are held accountable.

Should the evidence gathered through the course of this consultation demonstrate that the current self-regulatory approach is not sufficient and the regulator requires stronger powers of enforcement, we could seek to strengthen the statutory backstop for advertising regulation. In addition to the formal backstop arrangements the ASA already has in place with a range of statutory regulators and, separately, the powers already exercised by statutory regulators in relation to online advertising, this would introduce a statutory regulator to backstop additional areas of the ASA’s codes. This would involve a co-regulation arrangement in which the statutory regulator could delegate the writing and maintenance of codes to the industry self-regulator, with sign off required for any code changes. In the case of a statutory regulator backstopping the self-regulatory code, stronger regulatory powers (such as bans and fines) would likely only be applied in certain circumstances, for example to repeat offenders or those involved in disseminating illegal harms such as fraud.

We also ask for views from respondents on a full statutory approach. This would involve appointing a statutory regulator to introduce measures designed to increase transparency and accountability across some or all actors in the ecosystem. This would empower the statutory regulator to either build on the existing codes in use or design new codes for the actors in scope, and where they would be responsible for regulating all aspects of the codes (rather than just repeat offenders or more serious breaches). Chapter 6 sets out these three options for levels of regulatory oversight which would dictate how prescriptive a regulator could be in holding different players to account.

In order to build on the measures already in place for advertisers, we suggest further proposals that could be implemented to complement the existing CAP Code. We also seek to consult on new measures to hold intermediaries, platforms, and open display publishers to account, which may be implemented through a code like the OPNS, or through either the backstopped or full statutory approaches detailed in chapter 6. These measures are designed to improve transparency and accountability throughout the system and we would welcome views from respondents on their expected impact, both in terms of benefits and costs.

The Online Advertising Programme aims to maintain the UK advertising sector’s world-leading position by building a robust, coherent and agile regulatory framework that is equipped with the right tools to increase transparency and accountability across the supply chain. By looking at this issue, the government intends to lower the risk of both existing and novel online advertising harms that may arise in future. We see developing effective regulation as a means of improving trust in this critical market, which will in turn protect its overall sustainability. This will have benefits for business as well as consumers.

1. The scope of the programme and context for online advertising reform

1.1 Wider digital regulation landscape and upcoming reform

This government is pro-innovation and recognises the value that digital and creative economies add both socially and economically. However, as digital technologies underpin more and more of our economy, society and daily lives, we need to ensure that the rules governing them keep pace. We are cognisant of the complexities and interdependencies in considering the regulation of online entities, and that no single intervention will address all issues.

In the Plan for Digital Regulation, the government set out its vision to drive prosperity through a coherent, pro-innovation approach to the regulation of digital technologies, while minimising harms to the economy, security and society. Within this, the government specifically committed to help keep the UK safe and secure online. This means that citizens are empowered to be safe online, and can trust they are protected from online harms beyond their control, and that consumers can trust that they are treated fairly, and have choice over the services they access.

The approach we are taking in the Online Advertising Programme (OAP) reflects the vision set out in the government’s Plan for Digital Regulation, and will ensure that proposals for reform encourage the use of tech as an engine for growth in order to drive prosperity and create competitive and dynamic digital markets.

Throughout the development of the OAP, we will continually examine the interdependencies and overlaps between online advertising and other digital regulatory initiatives. We are committed to ensuring that we do not duplicate these efforts, but instead achieve forward-looking and coherent regulatory outcomes. We aim to create a regulatory framework that can deal with the problems we face today, with the flexibility to adapt to new threats and opportunities as they develop in the future. We also recognise this is a global marketplace and issues related to online advertising are not unique to the UK. The UK wants to lead the way in creating a new rulebook for digital technologies which is effective, agile and pro-innovation.

In addition to existing digital regulation that is relevant to online advertising, there are other regulatory interventions in the pipeline that will likely have an impact on the online advertising ecosystem. These include reforms to tackle harmful content online, promote competition in digital markets, deliver a new data protection regime and ensure regulators working across the digital landscape deliver a coherent, innovation-friendly digital regulation approach.

1.1.1 The Online Safety Bill

The forthcoming Online Safety Bill will introduce statutory requirements on services that enable users to share content and interact with each other, as well as for search services to protect their users from harm, while protecting freedom of expression. Companies will have duties to take action to minimise the proliferation of illegal content and activity online and ensure that children who use their services are not exposed to harmful or inappropriate content. The biggest tech companies will also have duties on legal content that may be harmful to adults. This regulation will be enforced by the Office of Communications (Ofcom).

Both the Online Safety Bill and the OAP seek to build on the government’s Plan for Digital Regulation by working to ensure that individuals are protected from illegal and legal but harmful online content. Paid-for advertising is largely out of scope of the Online Safety Bill, which has been designed to regulate user-generated content on user-to-user services and search services. It involves additional companies to those the government is regulating via the Online Safety Bill, with paid-for online advertising disseminated via distinct channels compared to user generated content. Moreover, many of the harms associated with advertising differ from those being regulated within the Online Safety Bill. The Online Safety Bill is therefore not the right vehicle by which to regulate the many and varied services involved in the online advertising ecosystem, including ad tech[footnote 1] and intermediaries.

However, in light of the need for urgent action to address the issue of fraudulent advertising, the government has decided to introduce a standalone duty to tackle fraudulent advertising in the Online Safety Bill. The duty will increase protections for consumers by requiring high-reach and high-risk services that are already in scope of the Online Safety Bill, as well as the largest search engines, to put in place proportionate systems and processes to prevent (or “minimise”, in the case of search services) individuals from encountering fraudulent advertising on their service. Ofcom will set out further details on how services can meet their duties in codes of practice. Additionally, all companies in scope of the Online Safety Bill will need to take action to tackle fraud, where it is facilitated through user-generated content or via search results.

This decision also responds to recommendations from the Joint Committee scrutinising the draft Online Safety Bill to tackle fraudulent advertising, and the duty will go a long way toward protecting consumers online and preventing criminals from accessing paid-for advertising services. The duty is designed as a standalone measure, and paves the way for additional, complementary work through the OAP to look at the role of the entire ecosystem in relation to fraud, as well as other harms caused by online advertising.

In relation to fraud, the OAP will build on the duty in the Online Safety Bill, seeking to address whether other actors in the supply chain, such as intermediaries, have the power and capability to do more. The OAP will focus on the role of ad tech intermediaries in onboarding criminal advertisers and facilitating the dissemination of fraudulent content through use of the targeting tools available in the open display market. This will ensure that we close down vulnerabilities and add defences across the supply chain, leaving no space for criminals to profit.

The launch of this consultation coincides with the introduction of the Online Safety Bill to Parliament, following a period of pre-legislative scrutiny. This is to demonstrate that the government views these two programmes as complementary, and acknowledges the significant interactions between them. While the focus of the Online Safety Bill is largely the harm created by user generated content, the OAP will examine and seek to address the harm created by online advertising. In this way, there will be a coherent legislative framework that meets the aims of the Plan for Digital Regulation regarding keeping the UK safe and secure online, driving competition and innovation in the online advertising market, and promoting plurality of online content, which is a crucial element in a flourishing democratic society.

1.1.2 The new pro-competition regime for digital markets

Work on the OAP will also complement the government’s work to establish a new pro-competition regime for digital markets. This follows recommendations set out in the Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) 2020 online platforms and digital advertising market study. The new regime will promote competition and competitive outcomes, and as such competition issues are out of scope for the OAP.

In July 2021, the government set out its proposals for a new pro-competition regime for digital markets in a public consultation. The regime will drive a more vibrant and innovative economy across the UK, overseen by a new Digital Markets Unit (DMU) within the CMA. This unit will have the bespoke regulatory toolkit required to address the unique issues arising from digital markets.

The regime will apply to firms designated with ‘Strategic Market Status’ in a given activity, via an evidence-based assessment of their market power. Its core objective will be to promote competition in digital markets for the benefit of consumers and it will be empowered to tackle both the underlying sources of market power and its consequences. Firms who are subject to the regime will be required to comply with new conduct requirements, and the DMU will have the ability to design iterative pro-competitive interventions to tackle the sources of harm in these markets.

The DMU is currently operating on a non-statutory basis, ahead of the government placing the regime on a statutory footing as soon as parliamentary time allows. It will then be for the CMA, as an independent regulator, to determine how to utilise its powers. The new rules will benefit businesses who rely on powerful tech firms including, in some circumstances, advertisers.

1.1.3 Data protection reform

As the government sets out in its National Data Strategy, published in 2020, data is a huge strategic asset and is the driving force of modern economies. The government recently set out its plans for a new pro-growth, innovation friendly data protection regime in the ‘Data: A New Direction’ public consultation (2021). The proposals look to build on key elements of the current UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR), such as principles around data processing, people’s data rights and mechanisms for supervision and enforcement, but will aim to reduce the burdens on organisations and businesses and ensure better data sharing between public bodies. The government is currently considering the responses to the consultation and will respond in spring 2022. Given the importance of data in aiding the targeting practices used in online advertising, data protection policy developments will be important to consider as we develop the OAP.

1.1.4 The Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum

The Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (‘the Forum’) is a forum for regulators working across the digital landscape and is currently made up of the CMA, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), Ofcom, and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The Forum’s inaugural work plan for 2021/22 outlined three core priority areas:

- developing strategic projects on industry and technological developments, including digital advertising technologies, algorithmic processing, and end-to-end encryption

- identifying opportunities for join-up in regulatory approaches across priority areas, e.g. data protection and competition including the Age Appropriate Design Code, Video-Sharing Platform (VSP) regulations and Online Harms

- building the skills and capabilities of the Forum members

The Forum intends to work closely with the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), Payment Systems Regulator (PSR), the Intellectual Property Office (IPO), the Gambling Commission and other agencies as appropriate. As outlined in the Plan for Digital Regulation, the government sees the Forum as an important step forward in our ability to deliver a more coherent and innovation-friendly approach to digital regulation. We will engage the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum in ensuring regulatory reforms relating to the online advertising market are coherent and effective.

1.2 Scope and purpose of the Online Advertising Programme

Within the wider context of digital regulation set out above, the OAP will examine the full spectrum of consumer and industry harms associated with all forms of paid-for advertising online. Online advertising is the use of online services to deliver paid-for marketing content. Advertising is paid-for when the placement is in part determined by systems or processes (human or automated) that are agreed between the parties entering into the contract relating to the advertising, and/or when the provider of the service receives any monetary or non-monetary considerations for the advertisement.[footnote 2] [footnote 3]

The harms associated with paid-for online advertising, which span both legal but harmful and illegal harms, across content, placement and targeting, are set out in the taxonomy of harms in chapter 3.

The OAP’s overall objective is to determine whether the current regulatory regime is sufficiently equipped to tackle the challenges posed by the rapid technological developments in online advertising. The OAP will ensure that the regulatory framework for online advertising builds trust and tackles the underlying drivers of harm in online advertising. The OAP will also consider the role and responsibilities of all actors involved in the supply chain of online advertising. The desired outcome is that regulators are given the appropriate powers and tools to effectively address issues in the online advertising ecosystem holistically and to take action on specific issues without the need for isolated intervention from the government.

The government will seek to develop a coherent, comprehensive advertising regulatory framework for all actors across the advertising supply chain. This focus will complement the government’s wider reforms on competition, data protection and user-generated content, ensuring that the online advertising market which is at the heart of our digital economy can continue to thrive. To fulfil this aim, our overarching principles for the OAP are to:

-

Support a thriving online advertising sector by increasing trust and reducing harms to UK internet users.

-

Tackle and improve the underlying drivers of harm in online advertising, including a lack of transparency and accountability, by considering the role of all actors in the supply chain.

-

Develop coherent and proportionate regulation that takes the complexity of the online advertising ecosystem into account and enables effective regulation for current as well as new and emerging harms.

-

Address the online advertising ecosystem holistically, only taking further action in specific types of advertising where evidence suggests the framework will not deliver effective protection.

-

Complement related regulatory action already underway, including the CMA’s new Digital Markets Unit (DMU) which will oversee the new pro-competition regime, the FCA’s work in relation to financial promotions, the ICO’s work on data protection and privacy, and the Gambling Act review.

-

Build on existing industry initiatives designed to address issues in online advertising, where they are delivering effective protections.

1.2.1 Market categories of online advertising in scope

We have set out below the market categories of online advertising that we are aware of which advertisers use to reach consumers, and that are within scope of this consultation. We have built on the CMA’s market study into online platforms and digital advertising to inform our understanding of these market categories. Broadly, the online advertising market can be broken into the five key market categories outlined in the table below, with additional explanatory descriptions provided in annex A.

Figure 1: Market categories of online advertising

| Market category | Supply chain | Type of advert | Example hosts of type of advert |

|---|---|---|---|

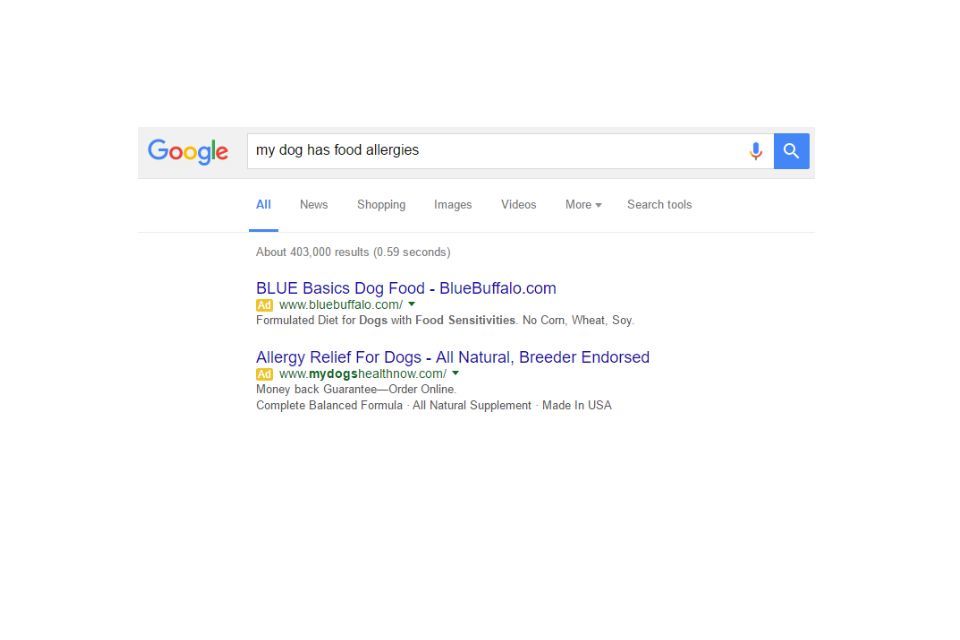

| Search | Usually purchased directly from search providers through owned and operated environments | ● Paid-for listings in search results, such as sponsored links or promotional listings. | Google, Bing |

| Social Display | Usually purchased directly from social media providers through owned and operated environments | ● Range of advertising formats on social media platforms. ● Paid-for online video advertising, such as video adverts served before, during or after films, programmes or other non-advertising content on videos or video sharing sites. ● Paid-for online social media advertising, such as in-feed advertising on social media. |

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, TikTok, Snapchat, Youtube |

| Open Display | Purchased through open display, or bought directly from publishers. Some platforms also offer services to place advertising on third party publishing sites | ● Paid-for banner ads on news websites and apps, swipe to buy. ● Paid-for in-game advertising, such as banner ads in games apps. ● Paid-for newsletter advertising, such as banner ads in a cookery newsletter. ● Paid-for advertising on internet served video-on-demand services ● Banner and video ads provided as part of the electronic programme guides and home screens of internet enabled TV sets. |

The Guardian, Reach, Mail Online, ITV (including ITV Hub), Sky, Buzzfeed |

| Classified | Purchased directly from platform or publisher | ● Paid-for listings on price comparison or aggregator services, such as sponsored listings on food delivery, recruitment, property, cars and services. | Gumtree, AutoTrader, Zoopla, Monster. |

| Content marketing, sponsorship and influencer marketing | Procured through contracts with influencers, or arranged directly with the publisher | ● Sponsored content on publisher or platform services, including paid promotion on creators’ social media posts ● Paid-for influencer marketing, such as influencer posts paid for/sponsored by an advertiser ● Paid-for product specific sponsorship ● Paid-for advertorials ● Paid-for advergames |

Social media influencers, publishers or platforms who host sponsored editorial content |

These market categories do not include unpaid advertising. This is to exclude from scope so-called ‘owned media’, which is any online property owned and controlled, usually by a brand. For owned media the brand exerts full editorial control and ownership over content, such as a blog, website or social media channels. It should be noted that the ASA regulates advertisements and other marketing communications by or from companies, organisations or sole traders on their own websites, or in other non-paid-for space online under their control, that are directly connected with the supply or transfer of goods, services, opportunities and gifts, or which consist of direct solicitations of donations as part of their own fund-raising activities.

However, we do intend to include influencer advertising in-scope of the OAP where payment has been made, either directly or in-kind, to an influencer in order to advertise a brand’s products and services. Recognising that as user-generated content, provisions in the forthcoming Online Safety Bill will also apply to influencers, the OAP will seek to consider whether there are any important gaps in coverage either from the forthcoming Online Safety Bill or other existing regulatory requirements, such as in relation to advertiser disclosure.

Consultation question 1

Do you agree with the categories of online advertising we have included in scope for the purposes of this consultation?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

Do you think the scope should be expanded or reduced? Please explain.

Consultation question 2

Do you agree with the market categories of online advertising that we have identified in this consultation?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

Do you think the scope should be expanded or reduced? Please explain.

1.2.2 Actors in scope

The OAP will look at the whole online advertising ecosystem in order to capture all the players in the supply chain that have the power and capability to do more to combat harmful advertising. We will consider the role played by each of the actors in the various supply chains, which includes:

- Advertisers (brands):[footnote 4] Individuals, businesses, organisations which direct the content of a message within an online advertisement, directly or indirectly, in order to influence choice, opinion, or behaviour. Typically advertisers work alongside media buying agencies or creative agencies to develop and shape their message in order to produce the intended outcome (e.g. greater engagement/sales). Some advertising agencies are vertically integrated and have their own proprietary ad tech.

-

Intermediaries:[footnote 5] Businesses and/or services which connect buyers and sellers (e.g through programmatic trading), facilitate transactions, and leverage data to provide buyers with targeting options for online advertising.[footnote 6]

- Ad tech:[footnote 7] Used to refer to all ad tech intermediaries, including DSPs, SSPs and ad servers (see below).

- Ad servers:[footnote 8] Publisher ad servers manage the publisher’s inventory and provide the decision logic underlying the final choice of which ad to serve. Advertiser ad servers are used by advertisers and media agencies to store the ads, deliver them to publishers, keep track of this activity and assess the impact of their campaigns by tracking conversions.

- Demand-side platforms (DSPs):[footnote 9] Provide a platform that allows advertisers and media agencies to buy advertising inventory from many sources. DSPs bid on impressions based on the buyer’s objectives and on data about the final user.

- Supply-side platforms (SSP):[footnote 10] Provide the technology to automate the sale of digital inventory. They allow real-time auctions by connecting to multiple DSPs, collecting bids from them and performing the function of exchanges. They can also facilitate more direct deals between publishers and advertisers.

- Online platforms:[footnote 11] Ad-funded platforms seeking to attract consumers by offering their core services for free. To promote their ad services they combine the attention of their consumers with contextual or personal information/data they have collected to serve advertising. Such platforms include (but are not limited to) search engines and social media sites.[footnote 12] These platforms may also serve advertising to other publishers. We include within this definition ad-funded Video-Sharing Platforms (VSPs).

- Open display publishers: Attract audiences through providing content and opportunities for advertising placement.

- Internet served Video-on-Demand (VOD) services: VOD services or On-Demand Programme Services (ODPS) which serve adverts to audiences via the internet.

By exploring how to ensure that all actors in the supply chain take an active role in minimising harms, we are seeking to ensure that the impacts of a coordinated approach can be more significant than focusing on one part of the supply chain, while ensuring that any regulatory burdens are minimised and fairly shared across the ecosystem. In doing so, we aim to create more space for trust in advertising to grow, with ultimate benefits for the sustainability of the market.

To clarify the relationship on fraudulent advertising between the Online Safety Bill and the OAP, we have set out in the box below the actors in the supply chain who will be held accountable through the forthcoming Online Safety Bill, with those who are in scope for the OAP. As per the actors in scope listed above, we take a broad view of intermediaries, and the actors listed in the table below are exemplary of the groups of intermediary organisations in scope, not exhaustive.

| Actor | In scope of OSB | In scope of OAP |

|---|---|---|

| Advertisers (including agencies) | No | Yes |

| Ad servers (Intermediary) | No | Yes |

| Demand-side platforms (Intermediary) | No | Yes |

| Supply-side platforms (Intermediary) | No | Yes |

| Platforms | Yes | Yes |

| Publishers (other hosts of online ads) | No | Yes |

Consultation question 3

Do you agree with the range of actors that we have included in the scope of this consultation?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

Do you think the range should be expanded or reduced? Please explain.

1.2.3 Harms in scope

The OAP will focus on the harms directed towards or experienced by consumers, both intentionally by bad actors in the system (such as fraudulent adverts, adverts for illegal activities and adverts that cause serious or widespread offence), or unintentionally. We will also be considering harms to advertisers and industry, including brand safety concerns driven by the placement of advertising next to inappropriate or harmful content, as well as the potential for advertising to fund harmful content (such as sites carrying misinformation or disinformation). Chapter 3, which includes a full taxonomy of harms, provides further detail on the various harms we are seeking to cover as part of this work. We welcome responses that provide evidence and suggest remedies that are not already adequately addressed by existing regulatory mechanisms to tackle the full spectrum of different harms associated with online advertising.

1.2.4 Issues out of scope

The following issues are out of scope of the OAP:

- Privacy issues - the ICO is examining the use of ad tech in the targeting of adverts to consumers through programmatic advertising.

- Whilst the use of data is relevant for targeting methods, data policy is out of scope for this consultation and is being considered through the separate consultation: Data: a new direction.

- User-generated content (except where it is also paid-for advertising) - this will be covered by the forthcoming Online Safety Bill.

- Political advertising - this has not been subject to advertising Codes since 1999. The government believes that having political advertising vetted or censored would have a chilling effect on free speech.

- Competition issues - this will be dealt with by the new pro-competition regime for digital markets.

2. The online advertising market

2.1 The value of advertising

Advertising contributes to the economic, social and cultural life of the UK. The UK has a thriving advertising market, with a total industry turnover of £40 billion in 2019 (for more information see the Annual data on size and growth within the UK non-financial business sectors as measured by the Annual Business Survey). It generated £17 billion in Gross Value Added and exported £4 billion in services in 2019. Whilst initially hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, the industry has made a remarkable comeback and profits are on track to be greater than initially predicted in 2021. An Advertising Association expenditure report forecast that the UK ad spend would total £29.3 billion in 2021, a year-on-year increase of 24.8%. Of this, online advertising spending in the UK was £16.47 billion in 2020, including £8.37 billion in search advertising, £6.31 billion in display advertising, and £0.98 billion in classified advertising (see section 1.2.2 for a definition of the different market categories).

Aside from the economic contribution of the industry, the sector makes a significant contribution to our social and cultural life, drawing in a wealth of creative talent. Employment in the UK was estimated at around 201,000 in 2020, with the sector bringing in a host of international workers, and many global agencies headquartered in the UK.

Advertising spend across all channels in the UK was £23.9 million in 2019, up 31% from 2012 (figure 2). Online advertising has come to sit at the heart of the digital economy and spending has steadily grown over the period to reach £14.3 million in 2019, a huge increase of 144% since 2012. The advertising market is dynamic and businesses have moved towards the channels that are giving them access to large audiences and demonstrating positive returns on investment. This has meant advertising has moved away from some channels with TV, print and direct mail seeing decreased spending over the period.

Figure 2: UK Advertising expenditure by channel, 2012-2019

Advertising Expenditure by channel (£m)

| Year | Cinema | Radio | Out of Home | Direct mail | TV | Online | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | £232m | £595m | £1,044m | £2,022m | £3,787m | £4,708m | £5,862m | £18,250m |

| 2013 | £194m | £564m | £1,039m | £2,007m | £3,359m | £4,741m | £6,569m | £18,437m |

| 2014 | £203m | £595m | £1,054m | £1,950m | £3,063m | £4,928m | £7,584m | £19, 377m |

| 2015 | £246m | £612m | £1,094m | £1,977m | £2,729m | £5,264m | £8,913m | £20,835m |

| 2016 | £258m | £635m | £1,158m | £1,785m | £2,348m | £5,216m | £10,382m | £21,782m |

| 2017 | £260m | £644m | £1,144m | £1,753m | £1,938m | £4,897m | £11,553m | £22,189m |

| 2018 | £254m | £668m | £1,209m | £2,022m | £1,720m | £4,941m | £11,987m | £22,801m |

| 2019 | £313m | £653m | £1,301m | £1,385m | £1,536m | £4,478m | £14,285m | £23,951m |

Online advertising is the fastest growing area of advertising globally. Global investment in ad spend is predicted to be in the region of $700 billion by the end of 2022, with digital advertising contributing to around half of that figure. The UK is the largest market in Europe for advertising and fourth largest in the world by ad spend. A significant boost to the UK’s advertising industry has been its strong position in the development of advertising technology, which has attracted over £1 billion in investment since 2013.[footnote 13]

The rise of online advertising to become the dominant modern advertising medium reflects the significant shift seen in consumer consumption habits (and therefore eyeballs) over the last decade from traditional media, such as newspapers and TV, to online formats. Over four fifths of the adult population used the internet in 2021[footnote 14], with the average time spent online per week increasing from 14 hours to just under 25 hours from 2010 to 2020.

With the growth in internet consumption, advertising has become the primary source of revenue for many online businesses and underpins the provision of key online services such as search and social media. These services are positively transforming people’s lives, many of which we increasingly find hard to imagine living without. However, access to these services for consumers generally means the acceptance of advertising that is targeted at them, sitting alongside the content they enjoy. For businesses, online advertising offers high levels of personalisation and efficiency in reaching audiences, which is cost effective as well as convenient to both advertisers and consumers. It can help consumers to discover valuable new goods, interests and services, creating more accessible and low cost routes for businesses to engage with their audiences.

While online advertising offers many benefits for businesses and consumers, it is worth noting that the CMA’s study of platforms funded by digital advertising found that the largest platforms, Google and Facebook, and the incumbency advantages that these firms enjoy, caused a number of serious issues for other firms and consumers. The CMA found that ‘weak competition in search and social media leads to reduced innovation and choice and to consumers giving up more data than they would like’. The summary box in the market study final report states that ‘weak competition in digital advertising increases the prices of goods and services across the economy and undermines the ability of newspapers and others to produce valuable content, to the detriment of broader society’. These dynamics may therefore be eroding cost efficiency that could be enjoyed by a wide range of businesses in the marketplace.

This increased share in the advertising market enjoyed by online advertising, coupled with the related revolution in business practices that has accompanied it, has placed increasing pressure on the regulatory framework for advertising - originally designed in the offline era - to remain effective and relevant.

2.2 The online advertising ecosystem and market dynamics

The online advertising market is a continually evolving, dynamic market, with fast paced innovation in business practices. We recognise that an accurate and up-to-date view of the market dynamics within online advertising is critical to effectively assessing the appropriateness, proportionality, relevance and impact of potential interventions that could be taken to reform the regulatory framework. We use a range of terminology throughout this document, with a glossary set out at annex B.

In its most simplified form, the online advertising system involves businesses that want to advertise first designing a campaign, often working with advertising creative agencies and media buying agencies.

- Advertisers, working with their buyers, form the ‘demand’ side of the market and will then purchase advertising space in order to reach their desired audiences.

- Advertising space is provided by platforms and publishers, who form the ‘supply’ side of the market and can sell access to their audiences in order to fund their businesses.

- Between these sides of the market, advertising intermediaries may operate to facilitate transactions, leverage data or provide other services. The range of intermediaries between advertisers and publishers are sometimes referred to as ‘ad tech’ or the ‘ad tech stack’. Online advertising can be highly targeted to specific consumer interests using audience data and real-time automated systems provided by these intermediaries or platforms.

Online advertising provides a number of different ways for reaching consumers, with advertisers often using a combination of these supply chains to reach audiences. Each market category (set out in chapter 1) provides advertisers with a vehicle to advertise their services or products with consumers.

There are two primary channels through which advertisers can purchase advertising space online:

(i) buying space directly from ad-funded platforms who offer an integrated ad buying service - these systems are sometimes referred to as ‘owned and operated’ systems or ‘walled gardens’; or

(ii) through the open display market, whose supply chain matches advertisers’ buying specifications at one end, with advertising space across a range of open display publishers at the other.

2.2.1 Programmatic advertising

Programmatic advertising is the use of automated systems and processes to buy and sell inventory. This technology is in widespread use across the online advertising ecosystem. Selling advertising programmatically means that the selection, pricing and delivery of adverts to selected audiences are organised through automated computerised algorithms. The selection and targeting of audiences in programmatic systems are heavily reliant on the use of data (this can be a combination of personal and contextual data) by platforms and intermediaries, in order to personalise advertising.

Although some businesses and advertisers traditionally choose to make direct deals for display advertising, programmatic technology is used to support a variety of online transactions and continues to be popular given the level of sophistication it can offer. Advertisers want to maximise their return on investment, and targeting specific niches of potential consumers through the use of programmatic technology is one way to make sure that they are efficient.

Practices surrounding the use of data in programmatic advertising have been changing in recent years following new rules governing the use of cookies, which have influenced trends towards an increasing use of contextual data over personal data. Other innovations in the industry are likely to have further implications, such as those designed to offer an alternative to cookie-based approaches. Though data driven programmatic systems sit at the heart of most transactions today, the online advertising ecosystem is not static and market practices change over time.

Programmatic technology has opened up advertising markets to SME advertisers in a way that was not available to them before, enabling them to effectively target advertising cheaply and efficiently - offering them an alternative to advertising bought through platforms. At the other end of the supply chain, publishers of any size can also sell inventory programmatically, enabling them to reach a greater range of advertisers.

2.2.2 Online advertising supply chains

This section sets out the supply chains that form the primary channels advertisers use to reach consumers.

Platforms and the ‘Owned and Operated’ or ‘Walled Garden’ model

Most of the larger, ad-funded platforms, including Google and Facebook/Meta (who according to the CMA’s Online platforms and digital advertising market study made up around 80% of the online advertising market in 2019), operate closed supply chains. These services deliver a variety of marketing channels and targeting services in-house. In such a system, the platform owns the relationship with both the audience and advertiser, with no other party (other than potentially a media agency) involved in the buying and selling of its advertising inventory. Such a business model is also sometimes referred to as a ‘walled garden’ or ‘owned and operated’ system.

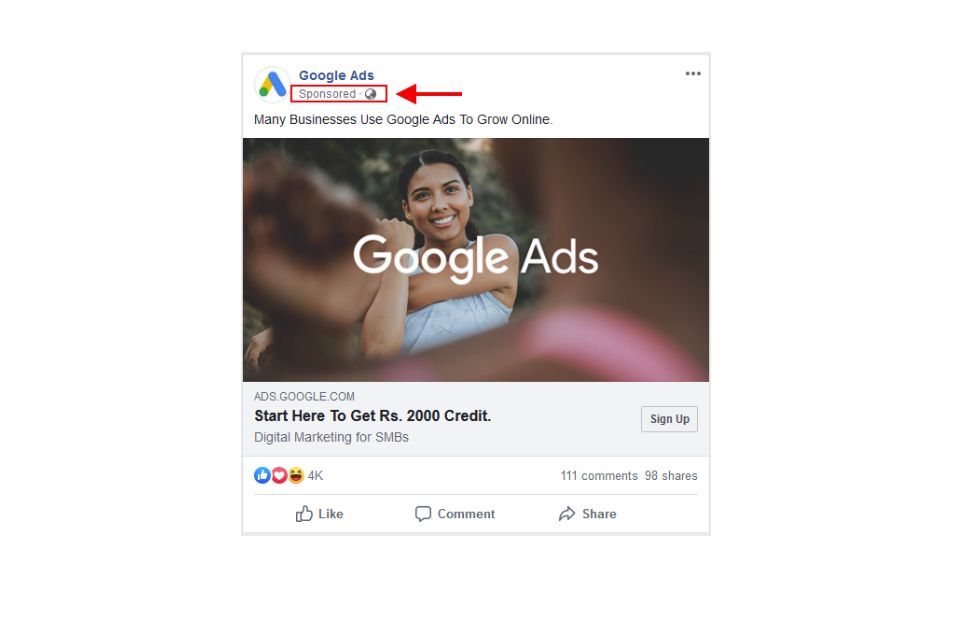

Some platforms, including both Google and Facebook/Meta, offer advertiser ‘self-service’ options, which means smaller operators can directly purchase advertising with little friction, creating a low bar to entry. High market share, ownership of key technologies in-house, and strong user data assets, lead to larger platforms such as Google and Facebook/Meta having more bargaining power. The CMA’s market study found that typically publishers are unable to negotiate the terms of their relationship with Google and Facebook.[footnote 15]

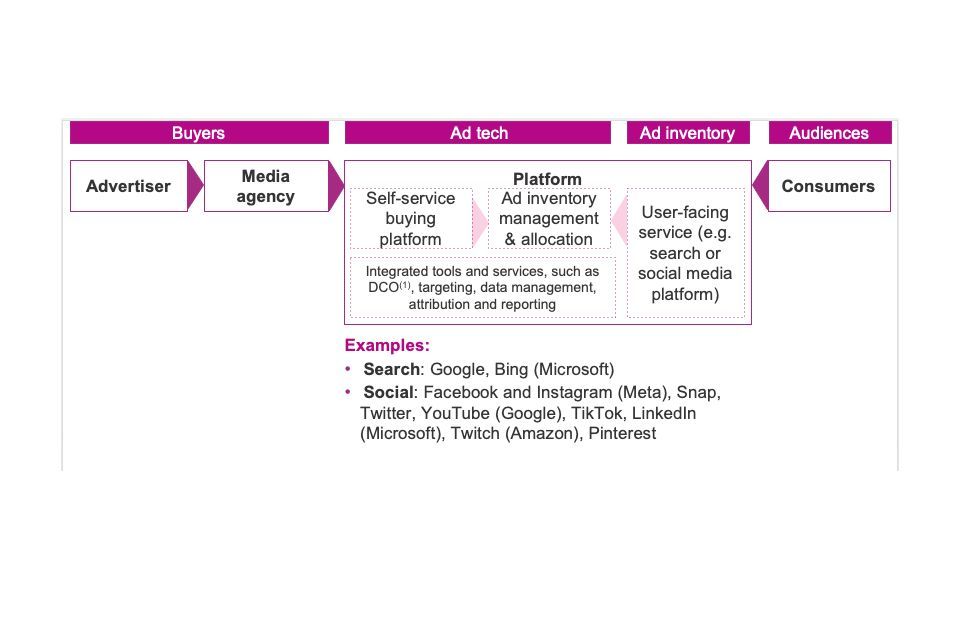

The below diagram (figure 3) offers a simplified view of the process used by platforms to serve advertising to users in a ‘walled garden’ or owned and operated system.

Figure 3: Owned and operated platform supply chain (simplified)

Figure 3: Owned and operated platform supply chain (simplified)

1. DCO = dynamic content optimisation.

2. This diagram simplifies the supply chain. In some cases, advertisers interface directly with platforms, without using a media agency. In some cases, advertisers or media agencies use tools such as Smartly.io to manage campaigns on platforms. In some cases, publishers distribute content on platforms in return for a share of advertising revenue and/or the right to sell advertising on their content.

3. Buying channels and platforms, and tools and services differ between platforms.

Open display markets

The main alternative vehicle for buying online advertising inventory to owned and operated systems is the open display market. Open display is a sector of the market that uses programmatic selling/buying through an intermediated model and is often used to connect advertisers to a range of online publishers, including news publishers. Advertising intermediaries, or the ‘ad tech’ industry, have evolved to meet the needs of these main groups of actors, advertisers and publishers. Advertisers exist on what is called the demand side: they are interested in reaching online audiences with their message. Publishers then exist on the supply side, operating websites or apps and seeking to monetise their services through selling advertising inventory.

The open display market is made up of a complex chain of businesses providing specific functions within the advertising supply chain.

On the demand side, the main participants include media agencies, advertiser ad servers, and demand-side platforms (DSPs). Advertiser ad servers are used by advertisers and media agencies to store information about ads and advertising campaigns, as well as to deliver, track and analyse campaigns. A DSP is a platform that allows advertisers and agencies to purchase targeted ad impressions from many different sources through a single interface. Real time bidding is typically used to execute this process.

On the supply side, the main participants include supply-side platforms (SSPs) and publisher ad servers. SSPs provide the technology for publishers to sell ad impressions through a range of external platforms (for example DSPs), allowing them to sell all of their inventory through a single interface. They can also be used for more direct deals between publishers and advertisers. Recently, SSPs and ad exchanges have largely merged to the point where these terms are often used interchangeably. Based on the bids received from different SSPs, and the direct deals agreed between publishers and advertisers, publisher ad servers manage publishers’ inventory and the final decision on displaying online advertising content to users.

The industry also includes further market participants involved in the provision and management of data, targeting practices and analytics in online advertising including data suppliers, data management platforms (DMPs), and measurement and verification providers.

Options for purchasing advertising space range from use of the full programmatic supply chain through to direct contracts between advertisers and some publishers. Some publishers are also expanding their own capability to offer more tailored direct services to advertisers, including more advanced audience targeting. This may in turn be leading, in some cases, to increased use of direct contracts, which can bypass some of the open display supply chain. The CMA market study concluded that open display comprises around 32% of display expenditure online.

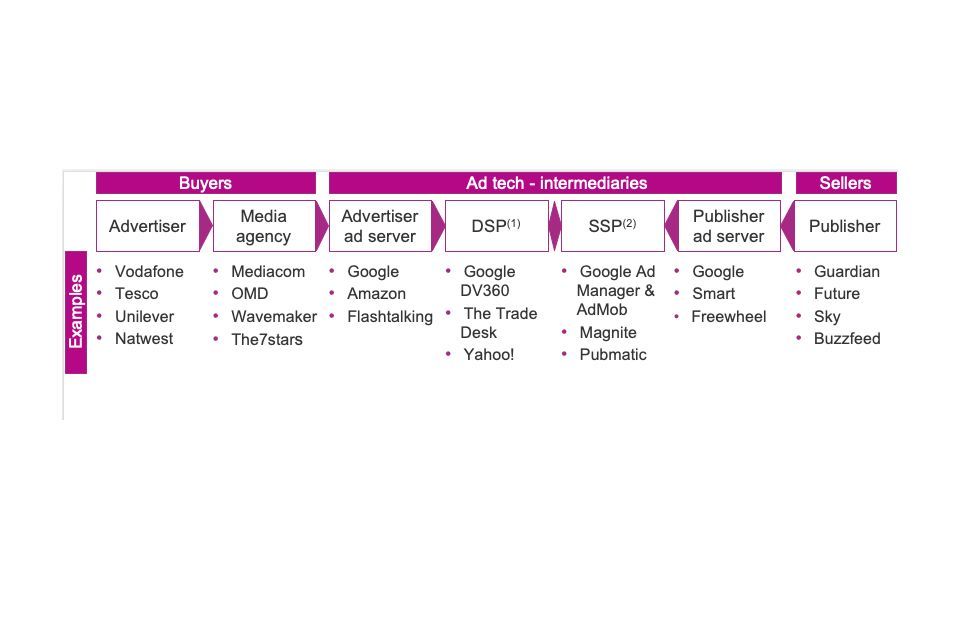

The below diagram (figure 4) provides a simplified illustration of the online open display supply chain, including the intermediaries involved in dissemination through this method.

Figure 4: Programmatic open display supply chain (simplified)

Figure 4: Programmatic open display supply chain (simplified)

1. DSP: demand-side platform.

2. SSP: supply-side platform.

3. Some ad tech competitors operate at multiple levels of the supply chain (e.g. Google, Amazon, Yahoo!).

4. This diagram simplifies the supply chain. Not all categories of ad tech vendors are shown, such as header bidding solutions and ad networks. In some cases, advertisers interface directly with ad tech vendors, without using a media agency. Some publishers sell ad inventory directly, involving manual orders or the use of an automated buying platform, without DSP and SSP involvement.

5. The ad tech ecosystem and roles are rapidly evolving.

Publishers in the open display market

We seek to draw a distinction between publishers in the open display market, such as online news publishers, and platforms operating owned and operated systems. Platforms tend to oversee the process of matching adverts to advertising space, whereas publishers are at the receiving end of the open display supply chain, and thus may have less control over what is advertised in their inventory. There is also a key difference in the scale, reach and resources available to these players which means we would expect any regulation in relation to their role to be proportionate. Open display publishers often rely on advertising for their financial sustainability and declining ad revenue has led some publishers to develop alternative business models. Many publishers apply controls over the quality and content of advertising on their sites due to reputational damage risks.

The CMA market study identified that some publishers of online content rely on large digital platforms, such as Google and Facebook’s user-facing services, to host content or for referrals of traffic to their online properties, which they can then monetise by displaying advertising to these visitors. They concluded that those publishers face an imbalance of bargaining power with Google and Facebook, which disadvantages their businesses in a number of ways including restrictions on their ability to control their own content and data, to manage traffic to their websites and to target advertising.

Online advertising buying services, such as media agencies

Most larger brands secure the services of media agencies to help them develop and deliver advertising strategies for the products and services that they wish to advertise. Advertising campaigns are generally complex and will involve buying advertising content over a range of channels both on and offline. Whilst it is possible for brands and advertisers to buy advertising space direct from both ad funded platforms and/or publishers, larger brands may use the services of a media buying agency whose job it is to procure relevant advertising space from across the online advertising ecosystem, in line with the agreed buying strategy for the brand’s products and/or services.

In addition to this, some agencies have developed their own proprietary tools and can therefore offer a range of services to their clients, such as data aggregation, offering clients some services which were previously provided by intermediaries. In this way, some agencies’ roles in delivering advertising have become more complex and vertically integrated.

Whilst media agencies play a key role online, in recent years it has also become common for brands to establish direct relationships, particularly with the ad funded platforms, meaning that media buying agencies do not always intermediate all transactions online. We understand this has had a consequential effect for the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) funding levy, which is collected by the Advertising Standards Board of Finance (Asbof), primarily from media agencies. The increase in brands and advertisers buying advertising space direct from platforms, and thereby escaping the levy, has only been partly offset by financial contributions by some platforms, including Google and Meta. It is also the case that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) who may not have complex, multi-channel buying strategies, are less likely to use media agencies.

New developments

In recent years, we have seen changes surrounding the use of data online, such as the introduction of new policies by big tech companies to limit the targeting of users. For example, in the place of cookies (which are being phased out on Chrome and have already been removed by default from Safari and Firefox), Google aims to implement replacement technologies, and its ‘Privacy Sandbox’ is testing approaches. This will still allow websites to show targeted adverts, while reducing the amount of information users share.

In the same vein, Apple’s new privacy measures include turning off the “identifier for advertisers” (IDFA) used for tracking by default. This means Apple users will have to grant apps explicit permission to use it and will thus likely significantly reduce the data available to third parties. In addition, the Meta group has recently announced that it will be removing some of its controversial targeting services (such as political affiliation, religion and sexual orientation).

Taken together, these changes may have a significant impact on the way online advertising is targeted, and are not without considerable competition concerns.[footnote 16] We are also aware of growth in new online media and advertising formats, including in-game, live influencer and voice, amongst others. As these formats grow, the advertising supply chain is expected to evolve further, and we will continue to consider these market changes as we develop the OAP.

Implications for reform

Understanding the way in which advertising space is typically purchased and disseminated online, and the different services that can be used within the online advertising ecosystem to reach audiences, is key to successfully considering appropriate regulatory solutions. Those regulatory solutions will need to successfully reflect the main market dynamics, such as the size, role, reach and resources available to the different players, the technologies they use and the activities in operation across all routes to market. We also recognise that such solutions will need to be proportionate for market participants of all sizes and flexible enough to respond to market changes.

Consultation question 4

Do you agree that we have captured the main market dynamics and described the main supply chains to consider?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

Please explain your answer.

Consultation question 5

Do you agree that we have described the main recent technological developments in online advertising in this section (section 2.2.2)?

a) Yes

b) No

c) Don’t know

Please explain your answer.

3. Harms caused by online advertising

3.1 Summary of the problem

As set out in the previous chapters, the online advertising industry has experienced rapid growth as online media consumption has increased. However, the size and growth of the sector has led to concerns about potential harms to consumers, firms and wider society.

Building on the call for evidence and research commissioned by DCMS over the past few years, we consider that there are a range of harms that can be attributed to online advertising which require urgent consideration to combat.

We propose these harms can largely be divided into two key areas:

a) the content of adverts; and

b) the targeting or placement of adverts.

We also recognise that harm can be exacerbated through the combination of the content of an advert and its targeting or placement, and that the risk of harm, particularly where content of an advert is combined with how it is targeted, can be greater for some groups than it is for others.

3.2 Call for evidence and previous commissioned research

3.2.1 Commissioned research

DCMS commissioned Plum Consulting to produce two reports on the online advertising landscape. A summary of these reports is set out below.

Online advertising in the UK (2019)

The study explored the structure of the online advertising sector and the movement of data, content and money through the online advertising supply chain. The report took stock of the UK’s online ad market and drew implications for consumers, society and the economy. Key findings from the report included:

- Census Given the current programmatic advertising market structure and practices, it is not possible to develop robust, independently verified, census-level data for the share of advertiser investment received by publishers or intermediaries.

-

Potential harms Harms could be broken down into three broad categories:

- Individual harms - potential impacts on individual firms and consumers which could include brand risk and inappropriate advertising.

- Societal harms - practices which may be detrimental to society as a whole, such as discriminatory advertising through targeting.

- Economic harms - potential harms that may arise from lack of competition or inefficiencies within the sector. - Social media placement Placing advertising within content, social or product feeds accounted for 92% of UK ‘native advertising’ (advertising which integrated into the surrounding content in a non-interruptive manner) expenditure in 2017.

- Targeting of online advertising: Increasingly, advertisers are creating profiles of their customers encompassing multiple data points, such as demographics and behaviour. They then seek to target “lookalike” audiences online.

Mapping online advertising issues, and industry and regulatory initiatives (2020)

The overarching findings from the 2020 report were that without an adequate regulatory system, consumers will not be sufficiently protected from the harms associated with online advertising. In addition, without regulation across industry it potentially leaves a gap for unregulated individuals and firms, and this is a significant area for improvement.

In order to tackle this issue effectively, Plum cited the below key areas as requiring intervention:

- A lack of a coherent consumer protection framework for online advertising issues. Intermediaries and online platforms do have certain obligations under consumer law – for example, the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 (CPRs) apply to platform operators where they act as traders and are engaged in commercial practices (as defined by that legislation). However, in general, there is room for a more coordinated and clearly signposted mechanism for consumers to report inappropriate ads and seek redress. The issue is compounded by overlaps in regulatory structure and responsibilities, which makes enforcement potentially difficult and time consuming. Also, the nature and causes of some of these harms often go beyond online advertising, underlining the need for closer coordination to improve regulatory effectiveness.

- Better data for monitoring purposes. Outside of the ASA, there is no independent measure for the effectiveness of the self-regulatory system. Without a requirement for organisations to share data there will continue to be an issue around transparency and accountability. The ASA does not have information gathering powers (as there is no underpinning legislation for this), meaning any cooperation from industry is based on goodwill.

- Limited regulatory oversight of online platforms. Currently, the ASA’s self-regulatory system for non-broadcast advertising primarily applies to advertisers with limited application to other actors in the supply chain. Whilst others - e.g. online platforms - have their own standards and codes to adhere to, there is no single regulatory body or organisation that is specifically responsible for ensuring these issues are enforced effectively or reporting on whether they are sufficiently tackling the issues they seek to address.

- Limitations of the incentive-based system. Incentives and sanctions for a small minority of ‘bad’ actors who operate with criminal intent do not act as a strong enough deterrent. They are capable of making sure ‘good’ actors such as legitimate companies and sole traders stay in line, but for those looking to commit fraud and other illegal activity, there is not a strong enough sanction for them to comply.

- Underdeveloped guidance on the potential issues associated with targeting. Current guidance is predominantly focused on children - the report suggests that we need to consider this further including the development of guidance for other vulnerable groups.

- Limited scope and reach of consumer awareness and public education initiatives. Whilst there is work being done in this space (by government and industry), there is still a lot of work to develop in this area to ensure consumers are equipped with the tools to be safe online.

3.2.2 Call for evidence on online advertising

As the second Plum report was being developed, DCMS also held a call for evidence on online advertising in 2020. Many of the responses received supported the conclusions of the Plum report, demonstrating a consistency in the issues requiring intervention. We asked ten questions as part of the call for evidence, which can be broadly categorised under the themes listed below. This summary outlines the views provided by the 50 respondents.

The extent to which consumers are exposed to harm by the content and placement of online advertising

The biggest concern raised by respondents to the call for evidence related to fraudulent advertising (including scams), with others citing concerns around legal but harmful advertising themes in advertising, such as body image. These were particularly highlighted by consumer and civil society groups who raised concerns about, for instance, the exposure of young audiences to adverts for products and services like diet pills and plastic surgery. Misleading adverts were also listed as being of concern, but to a lesser extent. Lastly, respondents raised concerns that there was evidence of advertising being used to fund misinformation, with one respondent noting that fake news sites in Europe could be earning in the region of $75 million of advertising per year.

Respondents also commented on the use of data and targeting in online advertising, stating that some practices around the personalisation of adverts were causing harm. One trade association highlighted that 86% of consumers wanted to have greater control over their data and 88% wanted to have greater transparency on how their data is used to ‘follow them around the internet’, and child safety groups raised concerns that influencers directly target audiences with posts which aren’t fully disclosed as ads. Many cited experiences of consumers who felt that the ads being targeted at them were very personal and invasive, for example those struggling with mental health issues.

The discrepancies between broadcast and online advertising regulation including the lack of a 9pm watershed equivalent for online advertising were noted by respondents. Although the 9pm watershed was viewed as imperfect, respondents did feel it was effective in providing a degree of insulation from adult TV content and advertising which was lacking in an online sphere.

The effectiveness of the current governance and regulatory framework for online advertising

The majority of stakeholders (59%) called for significant regulatory reform, with many saying the current regulatory system was insufficient. In particular they highlighted a lack of compliance to regulations due to inadequacy of funding and effective enforcement powers. Respondents reported there was a lack of transparency in the online advertising ecosystem. Respondents reported a lack of accountability for actors besides advertisers in the system, including the role of platforms and intermediaries. To combat this respondents encouraged further government intervention through further commissioned research or by looking to introduce more stringent regulation.

Respondents overall did not feel that the industry’s current initiatives went far enough, leading to a concern around a fundamental lack of trust in online advertising. Concerns regarding unethical targeting were highlighted by respondents who felt that personalised adverts followed them around the internet and that categorising or targeting in online advertising felt overly personal and invasive.This caused several stakeholders to flag the increased risk of invasive targeting of vulnerable people, such as people suffering from mental health conditions.

Respondents also flagged concerns surrounding the damage which online advertising could cause to other forms of media through broadcast discrepancy and to a lesser extent damage to the press sector.

The regulatory reform respondents want to see

A significant proportion of respondents said they favoured ‘beefing up’ the regulatory system and providing regulators with better funding and greater powers for enforcement. Responses suggested that the current standards and regulations in place were not doing enough to protect individuals. Whilst respondents pointed to the potential risks of harm associated with the use of data and targeting, they also pointed to how such technology could help form part of the solution - for example, by targeting harmful content away from vulnerable individuals.

The call for evidence responses overall indicate that the primary concern for the majority of respondents was a fundamental lack of trust in online advertising. There were several driving factors behind this broken trust, including that of a regulatory framework which needs to be strengthened as well as a lack of accountability and transparency across the board. Due to the lack of transparency in the system, there were substantive evidence gaps and it was not straightforward to unpick the dynamics at play in this market.

The chart below (figure 5) represents harms reported by respondents to the call for evidence. The most reported harms were offensive / harmful ads, malicious ads and ads for fraudulent goods and services.

Figure 5: Breakdown of harms reported by respondents to the 2020 call for evidence

Call for Evidence: harms reported (% of respondents)

| Harms | No. of respondents | % of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Malicious Ads / Scams | 16 | 31% |

| Offensive / harmful ads | 14 | 27% |

| Ads for illegal, restricted, counterfeit or fraudulent goods/services | 11 | 22% |

| Brand Safety | 9 | 18% |

| Ad fraud | 8 | 16% |

| Mis/disinformation | 6 | 12% |

| Misleading ads | 5 | 10% |

| Fake endorsement | 3 | 6% |

| Non-identified ads | 3 | 6% |

| Ad blocking | 3 | 6% |

| Bombardment | 3 | 6% |

| Fragmented consumer reporting | 3 | 6% |

| Keyword blocklisting | 1 | 2% |

The chart below (figure 6) sets out how different stakeholder groups viewed the current regulatory framework at the time of the 2020 call for evidence. Given the number of respondents, and that regulatory and market developments since then are not reflected, we are seeking to update this assessment in this consultation.

Figure 6: Assessment of the self-regulatory system by stakeholder group

| Organisation Type | Poor | Neutral | Good | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broadcasters | 66.6% | 33.3% | 0 | 100% |

| Consumers Groups | 83.3% | 16.6% | 0 | 100% |

| Online platforms | 16.6% | 16.6% | 66.6% | 100% |

| Publishers | 33.3% | 33.3% | 33.3% | 100% |

| Advertisers | 60% | 0 | 40% | 100% |

| Regulators/industry | 60% | 20% | 20% | 100% |

| Child Safety Groups | 25% | 75% | 0 | 100% |

| Research bodies/academics | 25% | 75% | 0 | 100% |

| Rightsholders | 0 | 100% | 0 | 100% |

| Individuals/businesses | 100% | 0 | 0 | 100% |

3.3 Taxonomy of harms caused by online advertising

The proposed taxonomy of harms below includes a spectrum of harmful online content and placement which we understand to be caused by or exacerbated through online advertising. These range from high-profile illegal content, to those harms which are legal but can still be harmful. The harms apply to both consumers and to industry.

We consider the full taxonomy of harms to fall into scope for consideration and potential action under the OAP. This is intended to be a comprehensive taxonomy and the government welcomes feedback on whether there are any categories of harm that are not included and should be considered as part of the OAP.

Figure 7: Taxonomy of harms in scope of the consultation

| Legality/ Illegality | Category of Harm | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|