New Plan for Immigration: policy statement (accessible)

Updated 29 March 2022

Foreword

The UK has a proud history of being open to the world. Global Britain will continue in that tradition.

Our society is enriched by legal immigration. We are a better country for it.

We recognise the contribution of those who have come to the UK lawfully and helped build our public services, businesses, culture and communities and we always will.

We also take pride in fulfilling our moral responsibility to support refugees fleeing peril around the world.

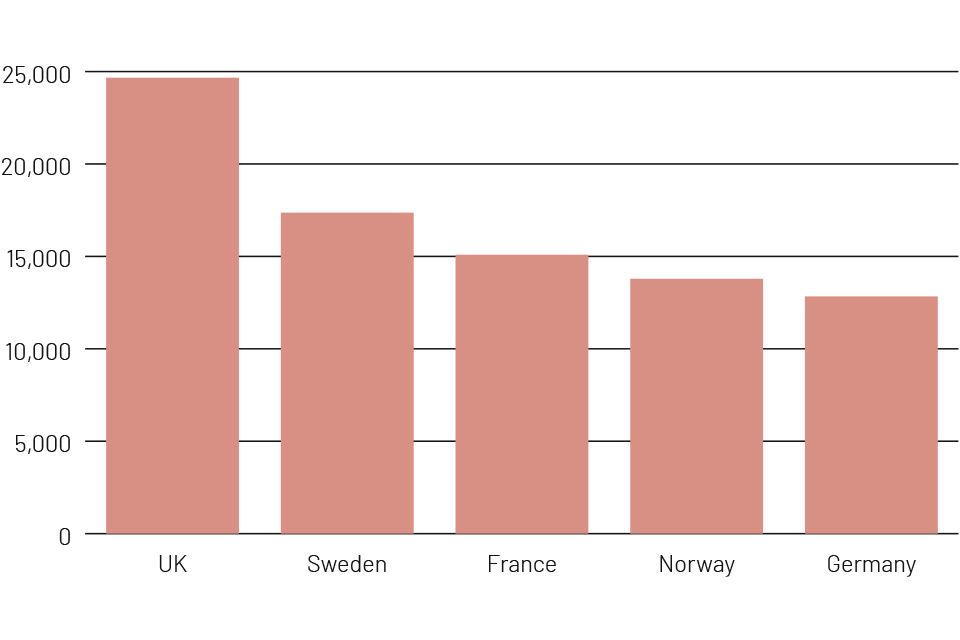

Since 2015, we have resettled almost 25,000 men, women and children seeking refuge from cruel circumstances across the world - more than any other European country.[footnote 1]

This year we have extended support to British National (Overseas) status holders and their family members threatened by draconian security laws in Hong Kong, creating a new pathway to citizenship for over 5 million people.[footnote 2]

And we continue to play our part as the third highest contributor of overseas development aid in the world.[footnote 3]

Behind each statistic lies the story of a person or a family who can look forward to a better future because of the generosity of the British people. We celebrate that.

But these humanitarian measures do not stand alone.

They are part of our overall approach to asylum and immigration.

And to sustain them, that system – all of it – must be a fair one.

This Government promised to regain sovereignty and we have made immigration and asylum policy a priority.

We have taken back control of our legal immigration system by ending free movement and introducing a new points-based immigration system.

The UK now decides who comes to our country based on the skills people have to offer, not where their passport is from.

That is how we are addressing the need for clear controls on legal immigration.

But to properly control our borders we must address the challenge of illegal immigration too.

This Government will address that challenge for the first time in over two decades through comprehensive reform of our asylum system.

Illegal immigration is facilitated by serious organised criminals exploiting people and profiting from human misery.

It is counter to our national interest because the same criminal gangs and networks are also responsible for other illicit activity ranging from drug and firearms trafficking, to serious violent crimes.

And if left unchecked, illegal immigration puts unsustainable pressures on public services.

It is also counter to our moral interest, as it means people are put in the hands of ruthless criminals who endanger life by facilitating illegal entry via unsafe means like small boats, refrigerated lorries or sealed shipping containers.

Families and young children have lost their lives at sea, in lorries and in shipping containers, having put their trust in the hands of criminals.

The way to stop these deaths is to stop the trade in people that causes them.

This is not a challenge unique to the UK, but now we have left the European Union, Global Britain has a responsibility to act and address the problems that have been neglected for too long.

At the heart of our New Plan for Immigration is a simple principle: fairness. Access to the UK’s asylum system should be based on need, not on the ability to pay people smugglers.

If you illegally enter the UK via a safe country in which you could have claimed asylum, you are not seeking refuge from imminent peril - as is the intended purpose of the asylum system - but are picking the UK as a preferred destination over others.

We have a generous asylum system that offers protection to the most vulnerable via defined legal routes. But this system is collapsing under the pressures of what are in effect parallel illegal routes to asylum, facilitated by criminals smuggling people into the UK.

The existence of these parallel routes is deeply unfair as it advantages those with the means to pay traffickers over vulnerable people who cannot.

And because the capacity of our asylum system is not unlimited, the presence of economic migrants - which these illegal routes introduce into the asylum system - inhibits our ability to properly support others in genuine need of protection.

This is particularly true in our court system where we are seeing repeated unmeritorious appeals and claims, often made at the very last minute, which can delay the removal of those – including Foreign National Offenders – with no right to reside in the UK. This can waste significant judicial resources, resulting in delays to the assessment of genuine claims which is to the detriment of vulnerable people.

The British people are fair and generous when it comes to helping those in need. But persistent failure to properly enforce our laws and immigration rules, and the reality of a system that is open to gaming and criminal exploitation, risks eroding public support for the asylum system and those that genuinely need access to it.

We are therefore compelled to act and have three major objectives with these reforms:

Firstly, to increase the fairness and efficacy of our system so that we can better protect and support those in genuine need of asylum.

Secondly, to deter illegal entry into the UK, thereby breaking the business model of people smuggling networks and protecting the lives of those they endanger.

Thirdly, to remove more easily from the UK those with no right to be here.

To deliver against these objectives our New Plan for Immigration will make big changes, building a new system that is fair but firm.

We will continue to encourage asylum via safe and legal routes, strengthening our support by offering an enhanced integration package to those arriving in this manner and immediate indefinite leave to remain in the UK for resettled refugees.

At the same time, this plan will mark a step-change in Government’s posture as we toughen our stance against illegal entry and the criminals that endanger life by enabling it. We will take steps to discourage asylum claims via illegal routes, as other countries such as Denmark have recently succeeded in doing.

We will increase the maximum sentence for illegally entering the UK and introduce life sentences for those facilitating illegal entry.

The use of hotels to accommodate arrivals will end and we will bring forward plans to expand the Government’s asylum estate to accommodate and process asylum seekers including for return to a safe country.

For the first time, whether you enter the UK legally or illegally will have an impact on how your asylum claim progresses, and on your status in the UK if that claim is successful. Those who prevail with claims having entered illegally will receive a new temporary protection status rather than an automatic right to settle, will be regularly reassessed for removal from the UK, will have limited family reunion rights and will have no recourse to public funds except in cases of destitution.

To tackle the practice of making multiple and sequential (often last minute and unmeritorious) claims and appeals which frequently frustrate removal from the UK, we will introduce a ‘one-stop’ process to require all rights-based claims to be brought and considered together in a single assessment upfront.

We will also introduce a robust approach to age assessment to ensure we safeguard against adults claiming to be children.

Through these and many other measures in this package, we are determined to bring lasting change to the system so that it is fair to everyone.

An asylum system that helps the most vulnerable and is not openly gamed by economic migrants or exploited by people smugglers.

One that upholds our reputation as a country where criminality is not rewarded, but which is a haven for those in need.

Not all of this will happen quickly. We will need to stick to the course and see this New Plan for Immigration through.

But this Government promised to take a common-sense approach to controlling immigration – both legal and illegal.

And we will deliver on that promise.

Rt Hon Priti Patel, MPSecretary of State for the Home Department

Chapter 1: Overview of current system

International context

The illegal migration we see is part of a larger global issue. This is not a challenge unique to the UK.

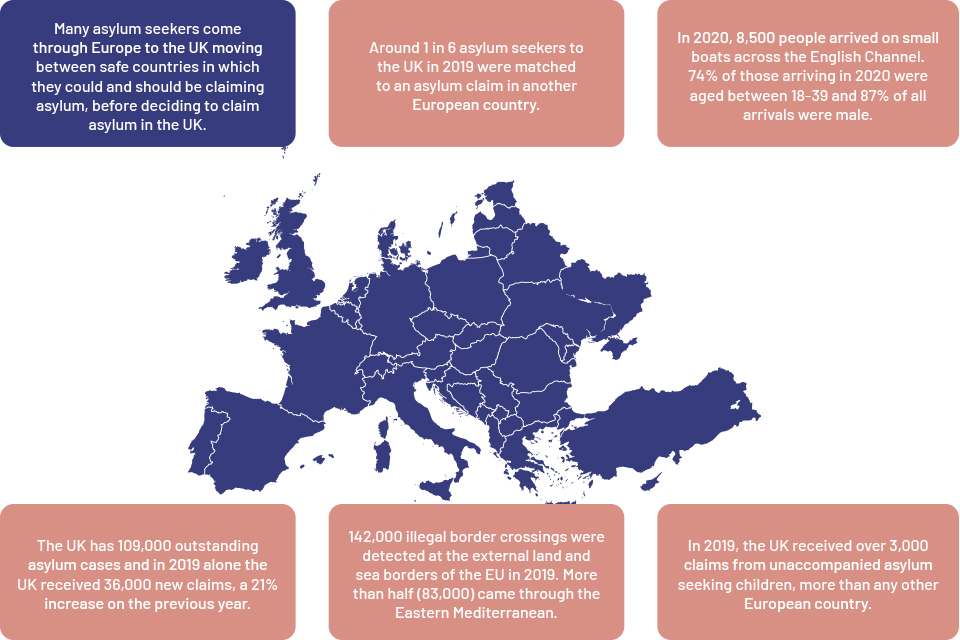

Many asylum seekers arrive via safe countries. Some match a claim elsewhere. In 2020 8500 people arrived on small boats. 142000 illegal border crossings were detected in the EU in 2019. In 2019 the UK received over 3000 claims from unaccompanied children

Resettlement

Global Britain has a proud history of helping those facing persecution, oppression and tyranny. We stand by our moral obligations to help civilians fleeing peril.

Top 5 European countries for arrivals via resettlement schemes 2015-2019

UK nearly 25000, Sweden 17500, France 15000, Norway 14000, Germany 13000

-

The UK accepted more refugees through planned resettlement schemes than any other country in Europe in the period 2015-2019 - the fourth highest number globally after the USA, Canada and Australia. The UK has resettled almost 25,000 men, women and children in those 5 years. Around half of those resettled were children. This includes refugees resettled through the vulnerable persons resettlement scheme.

-

The UK has also welcomed 29,000 people through the refugee family reunion scheme between 2015 and 2019. More than half of these were children.

-

The UK has recently introduced a new pathway to citizenship for British National Overseas (BN(O)) status holders and their family members facing draconian new security laws in Hong Kong. An estimated 5.4 million people are eligible for this scheme.

Access to the UK’s asylum system should be based on genuine need, not on the ability to enter illegally by paying people smugglers.

Protecting the UK border

Illegal migration causes significant harm and endangers the lives of those undertaking dangerous journeys.

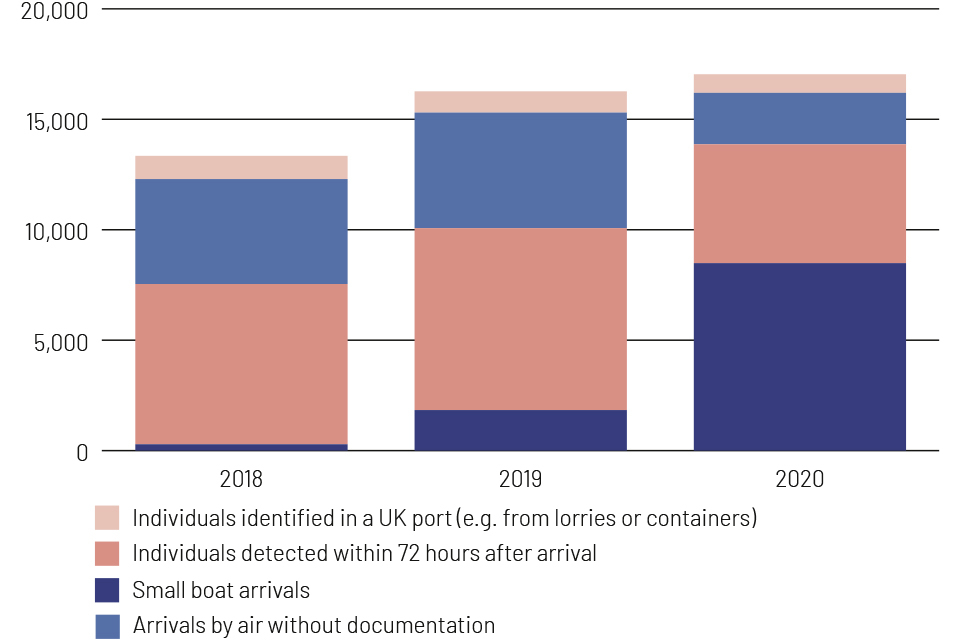

Detected irregular arrivals to the UK, by mode of entry, January 2018 to December 2020

Total increased from 13000 in 2018 to 17000 in 2020. As other routes have decreased the number using small boats has increased from under 1000 to over 8000

-

In 2019, 32,000 illegal attempts to enter the UK illegally were prevented in Northern France. 16,000 illegal arrivals were detected in the UK.

-

In the summer of 2020, the number of people crossing the English Channel in small boats reached record levels, with 8,500 people arriving this way that year. Other routes declined in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

-

74% of those arriving by small boat in 2020 were aged between 18-39 and 87% of all small boat arrivals were male.

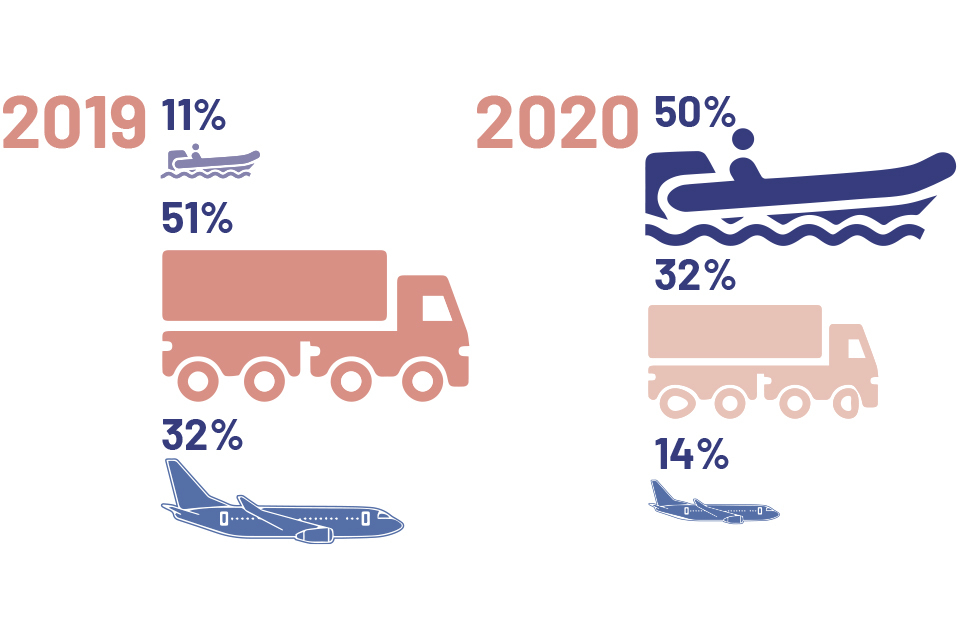

2019: small boats 11%, lorries 51%, air 32%. 2020 small boats 50%, lorries 32%, air 14%

People have died making these dangerous and unnecessary journeys.

Asylum system

The rapid intake of asylum claims has outstripped any ability to make asylum decisions quickly meaning caseloads are growing to unsustainable levels.

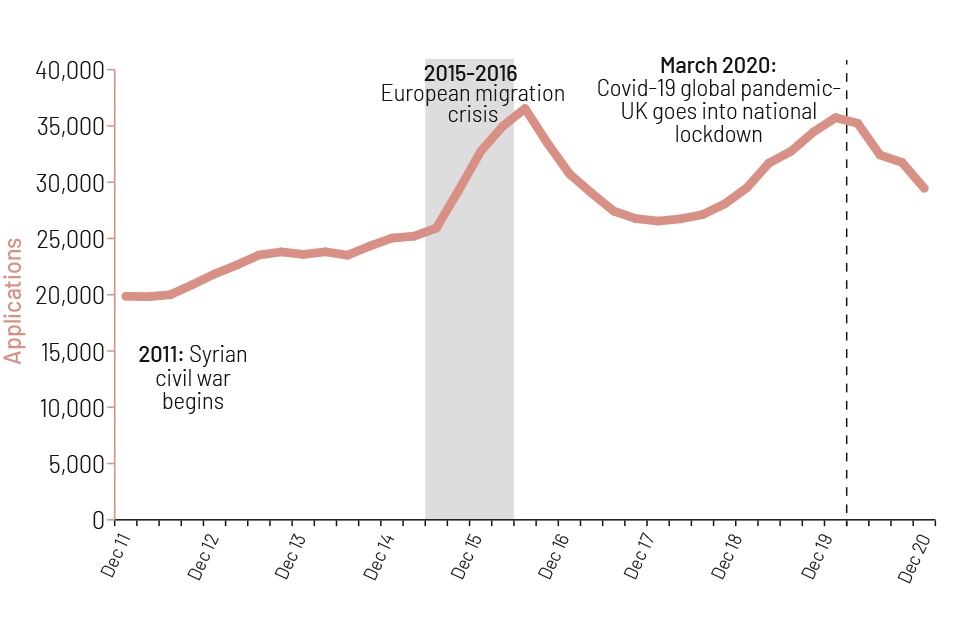

Asylum applications in the UK

applications rose from 20000 to 25000 between 2011 and 2015, to over 35000 by 2016, down to 26000 by 2018 and up to 35000 by 2020

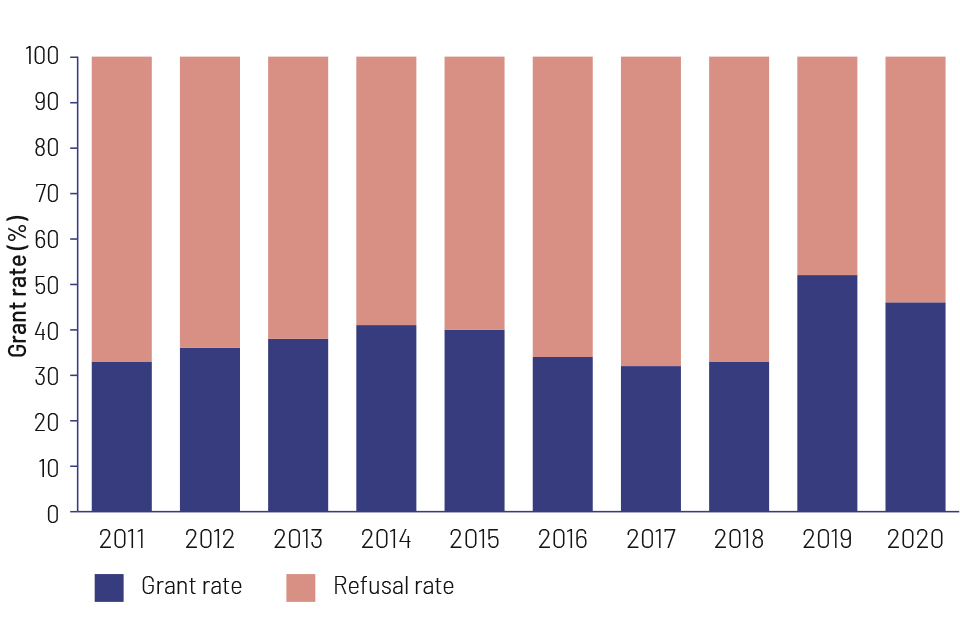

Grant and refusal rate for asylum claims

initial grant rate rose from 32% to 40% between 2011 and 2014, dropped to 30% by 2017, rose to over 50% by 2019 then fell to 45%

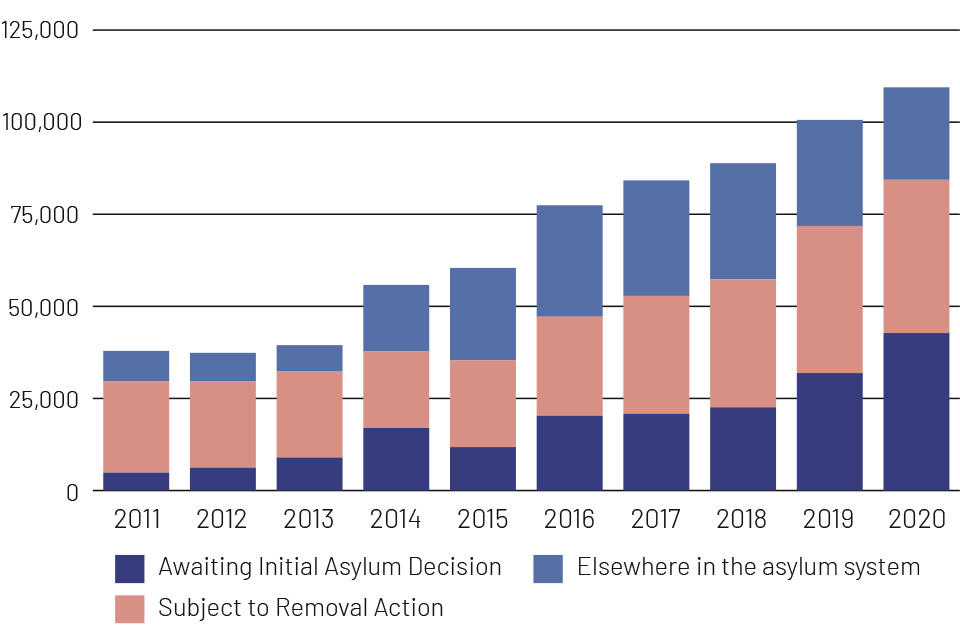

Asylum caseload at the end of June (2011-2020)

cases awaiting an initial decision have grown from 5000 in 2011 to 40000 in 2020, pushing total unresolved cases to 109000

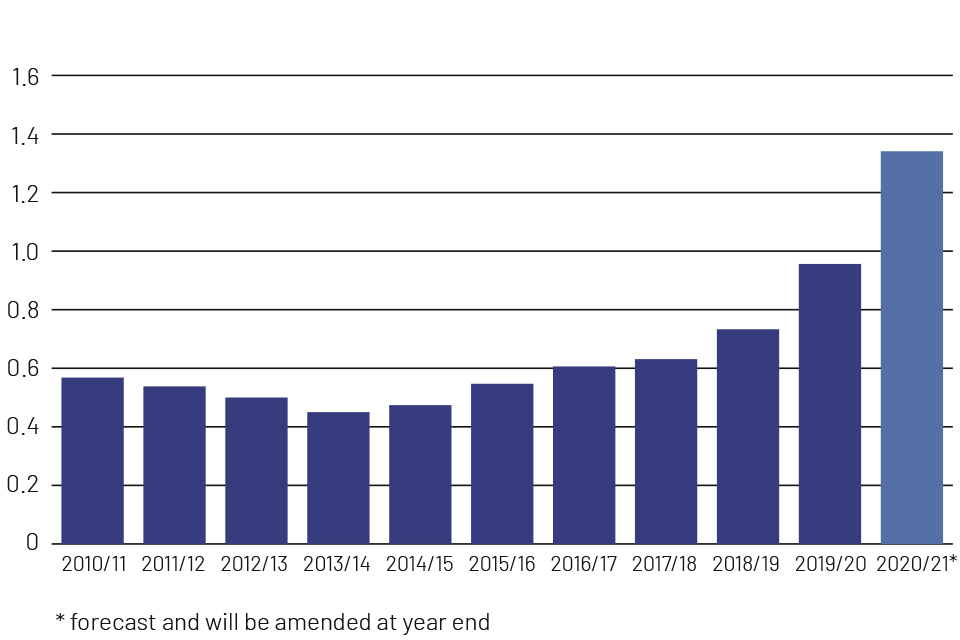

Cost of the asylum system to the taxpayer (£billions)

nearly 600 million in 2010/11, down to 450 million in 2013/14, rising to 1.35 billion in 2020/21

-

There are 109,000 asylum claims in the asylum system and the number of those awaiting initial decision rose to 52,000 by the end of 2020. Almost 73% of these claims have been in the asylum system for over one year.

-

Before the Covid-19 pandemic began, asylum applications were rising – increasing by 35% between 2017 and 2019.

-

In the year ending September 2019, 62% of UK asylum claims were made by those entering illegally - for example by small boats, lorries or without visas.

-

64,000 people are currently receiving asylum support - mostly through accommodation with cash or other in-kind support to cover essential living needs.

-

The asylum system is costing the taxpayer over £1 billion, the highest amount in over two decades.

Our asylum system is too easily exploited by people smugglers and does little to disincentivise individuals from attempting to enter the UK illegally.

Appeals

Justice is being delayed for those with genuine and important claims and valuable judicial and court resources are being wasted.

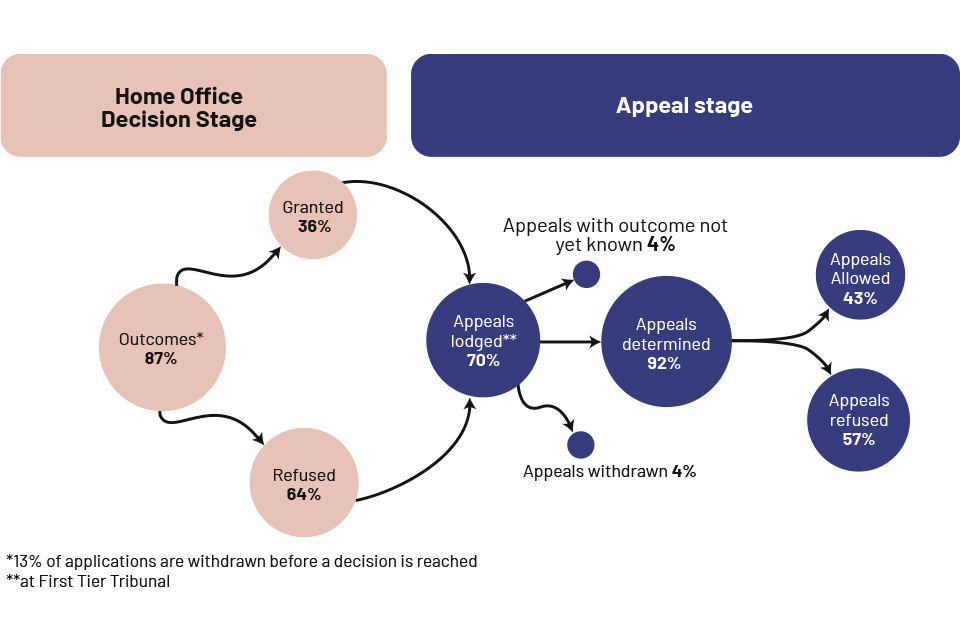

Asylum Appeals

A study of asylum appeals between 2016-2018

87% have outcome, 36% grant, 64% refuse. 70% lodge appeal. 92% of appeals determined. 43% allowed, 57% refused.

-

Nearly all of those refused asylum at initial decision go on to appeal to an Asylum and Immigration Tribunal.

-

Around half (46%) of asylum claims received in 2016-2018 in the UK were rejected following consideration of their case by the Home Office and subsequent review by the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal.

-

In 2019, 9,000 appeals were lodged following an initial asylum claim. Of those determined over the same period, 56% were dismissed.

Judicial Reviews

-

Last year, around 8,000 immigration Judicial Reviews were lodged against the Home Office, 6,500 of which were at the Upper Tribunal.

-

Of the approximate 6,000 cases determined on paper, 90% were dismissed or refused and out of these dismissals 17% were classified as “Totally Without Merit” by the court.

-

Of the decisions which reached permission hearing, around two thirds were dismissed. A similar proportion of Judicial Reviews were dismissed by a judge at substantive hearing.

The courts are becoming overwhelmed by repeated unmeritorious claims, often made at the last minute and justice is being delayed for those with genuine and important claims.

Returns

Our ability to enforce immigration laws is being impeded, contributing to a downward trend in the number of people, including Foreign National Offenders, being removed from the UK.

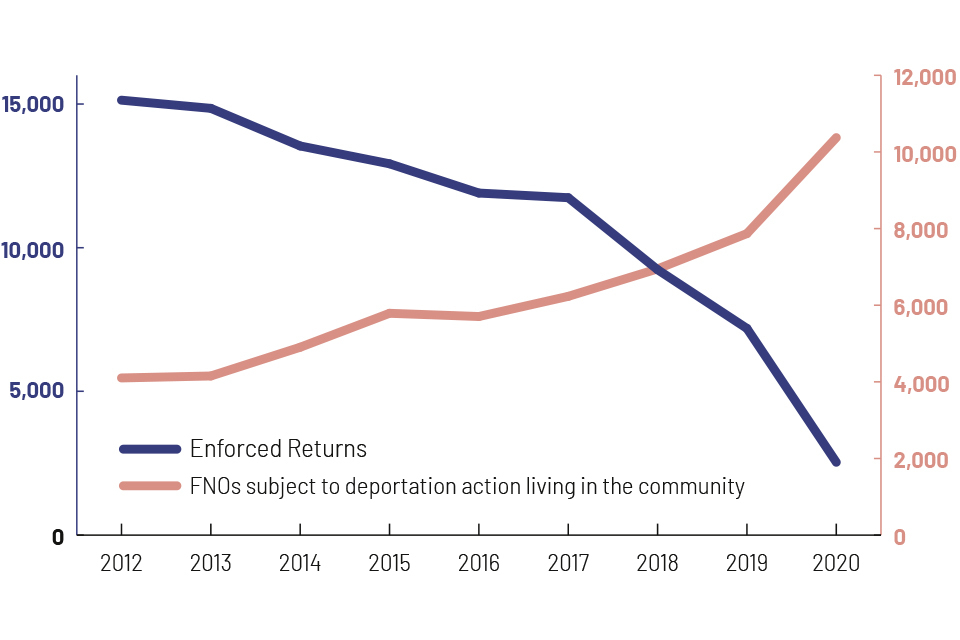

Numbers of enforced returns and Foreign National Offenders (FNOs)subject to deportation action living in UK communities

enforced returns down from 15000 in 2012 to 2000 in 2020. FNOs living in the community up from 5000 to over 10000

-

As of 2020, there are 10,000 Foreign National Offenders who have been released back into the community because they cannot be returned to their country of origin.

-

In 2019, new claims, legal challenges or other issues were raised by 73% of people who had been detained within the UK following immigration offences. This resulted in release from detention in 94% of cases instead of removal from the UK.

-

Very few of these claims amounted to a valid reason to remain in the UK. For all issues raised during detention in 2017, 83% were ultimately unsuccessful.

-

Around 42,000 failed asylum seekers are still living in the UK despite having their asylum claim refused.

Repeated legal challenges (often made at the last minute and which often transpire to be unfounded) have meant the UK has found it increasingly difficult to remove those with no right to remain in the UK, including Foreign National Offenders.

For information on statistical sources and referencing please see following chapters.

Chapter 2: Protecting those Fleeing Persecution, Oppression and Tyranny

The UK and this Government has a proud record of helping those facing persecution, oppression and tyranny and we stand by our moral and legal obligations to help innocent civilians fleeing cruelty from around the world.

As well as committing £10 billion to Official Development Assistance (ODA) each year - the second highest in Europe and third highest in the world – the UK is a world leader in refugee resettlement.[footnote 4] Safe and legal routes to the UK for those in need are well established and have helped many thousands of people in need make the UK their home.

-

Resettlement: We have around 25,000 refugees from 2015 to 2019 – more than any other European country. Around half of those resettled were children;[footnote 5]

-

Family Reunion: We have welcomed more than 29,000 close relatives through refugee family reunion in the last 5 years, around half of whom were children;[footnote 6]

-

British National (Overseas): We have introduced a new pathway to citizenship for British National (Overseas) status holders and their family members who are facing draconian new security laws in Hong Kong. More than 5 million people are eligible for this immigration route and an estimated 320,000 people may come to the UK over the next 5 years.[footnote 7]

While we cannot help all the estimated 80 million people displaced worldwide, Global Britain will continue to show global leadership welcoming those most in need.[footnote 8] We will maintain clear, well-defined routes for refugees in need of protection, ensuring refugees have the freedom to succeed, ability to integrate and contribute fully to society when they arrive in the UK.

To achieve this, we will strengthen the safe and legal ways in which people can enter the UK. We will:

-

Maintain our long-term commitment to resettle refugees from around the globe, including ensuring persecuted minorities are represented;

-

Grant resettled refugees immediate indefinite leave to remain on arrival in the UK so that they benefit from full rights and entitlements when they arrive;

-

Review the refugee family reunion routes available to refugees who have arrived through safe and legal routes;

-

Ensure resettlement programmes are responsive to emerging international crises – so refugees at immediate risk can be resettled more quickly;

-

Work to ensure more resettled refugees can enter the UK through community sponsorship, encouraging stronger partnerships between local government and community groups;

-

Introduce a new means for the Home Secretary to help people in extreme need of safety whilst still in their country of origin in life-threatening circumstances;

-

Enhance support provided to refugees to help them integrate into UK society and become self-sufficient more quickly;

-

Review support for refugees to access employment in the UK through our points-based immigration system where they qualify.

Resettlement Schemes

We will continue our proud record of welcoming and resettling refugees in the UK.

Over the last 5 years UK resettlement efforts have been focused where need has been greatest, resettling people from countries hosting large numbers of refugees including Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey following the Syrian conflict. So we can continue to help those most in need, now and in the future, we will build on our successful partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) by broadening the scope of the UK’s protection offer and operating a scheme which is accessible to people from more countries across the world.

This refined approach will prioritise resettling refugees, including children, from regions of conflict, rather than those who are already in safe European countries. We will also look at the range of people accessing resettlement schemes including the potential for people to achieve better integration outcomes in the UK.

Under these new plans, refugees who are resettled into the UK will benefit from full rights and entitlements through immediate indefinite leave to remain, providing them with the certainty and stability they need to build their life here.

We will also ensure our resettlement offer encompasses persecuted refugees from a broader range of minority groups (including, for example, Christians in some parts of the world). We know that across the globe there are minority groups that are systematically persecuted for their gender, religion or belief and we want to ensure our resettlement offer properly reflects these groups. We will strengthen our engagement with global charities and international partners to ensure that minority groups facing persecution are able to be referred so their case can be considered for resettlement in the UK more easily.

The UK’s commitment to resettling refugees will continue to be a multi-year commitment with numbers subject to ongoing review guided by circumstances and capacity at any given time.

Family Reunion Rights

We want to ensure that refugees who enter through safe and legal routes can reunite with close family members. We are already committed, through duties in the Immigration and Social Security Co-ordination (EU Withdrawal) Act 2020, to review legal routes to the UK from the EU for protection claimants, including to publicly consult on the family reunion of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. This commitment is fulfilled by the consultation accompanying this policy statement.

We will now also review the refugee family reunion routes available to refugees who have arrived through safe and legal routes. Specifically, we will consider whether there is a case for unmarried dependent children under the age of 21 (rather than just 18) to join their parents, where both parents are refugees living in the UK.

New Humanitarian Routes

We know that there are people facing persecution and threats to their life in their country of origin because of their gender, religion or cultural belief.

We want to build a more flexible system that can respond quickly and appropriately to those who are at very high risk and in need of support from around the globe.

We will therefore explore improving our systems to enable the Home Secretary to swiftly offer discretionary assistance to people still in their country of origin, allowing them to enter the UK in specific and compelling circumstances. Such cases would be exceptional and where the person’s life is at direct risk.

Support for Refugee Integration

Refugees in the UK should have access to the tools they need to become fully independent, provide for themselves and their families and contribute to the economic and cultural life of the UK. We want to ensure there is effective support so that refugees can integrate and become self-sufficient once they make the UK their home.

Previous resettlement schemes, specifically targeted at the most vulnerable, saw employment rates of only 5% after the first year. For refugees more generally, the employment gap, compared to the rest of the UK population, is over 30 percentage points. It can take over a decade for this gap to close.[footnote 9]

We will therefore develop tailored and flexible employment support arrangements to refugees arriving to help accelerate their progress as they adjust to life in the UK.

We have already committed £14 million for a cross-government Refugee Transitions Outcomes Fund to offer greater support to refugees with a focus on employment and getting people into work. Building on this programme and other schemes available, we will develop a package of tailored support such as language training, skills development and work placements to help refugees build their lives in the UK. Because proficiency in the English language is so important for refugees to successfully integrate into local communities and enter the workplace, we will improve the offer of English language teaching.

We also want a higher proportion of refugees to be supported by Community Sponsorship groups and will work with civil society and communities to encourage the growth of the Community Sponsorship scheme. Community Sponsorship enables local volunteer groups including charities and faith groups, to directly welcome and support refugees, helping with accommodation and integration support.

Access to Work for Refugees in the UK

There are many displaced people who could qualify for entry to the UK under the points-based immigration system but require additional support or signposting to apply. These people are highly skilled, can speak English and are able to secure a job offer. We will work with international partners to consider how best to support people to access existing immigration routes where they qualify for them, underlining that there is, and will continue to be, a safe and legal route to employment and ultimately settlement in the UK.

Resettlement: In Practice

A family was resettled by a community sponsor group, having fled from conflict in Syria. To help the family integrate into the UK, they were supported by the sponsor group to find school places, register with a GP, learn English and find employment. Just a few years later, the family are speaking fluent English, their children are in school and the parents are working and helping vulnerable people within their community. This demonstrates the importance of the UK’s world class resettlement programme.

In another case, a resettled refugee was supported to become self-sufficient through an employment support programme. They received training from the employment support group and now manage a local store in their community. As these stories highlight, many refugees are already contributing to their local communities.

The intended reforms aim to build on these successes, supporting more resettled refugees on the path to self-sufficiency.

Chapter 3: Ending Anomalies and Delivering Fairness in British Nationality Law

As we build on our proud record of helping those in need from around the world, it is right that we take this opportunity to correct historical anomalies which have existed for too long at home in British Nationality law.

British Nationality Law has not changed significantly since 1983, and some of the provisions are now outdated.

The reforms we will make to British Nationality law will finally address historical anomalies, which will impact hundreds of people annually, including:

-

Introducing new registration provisions for children of British Overseas Territories Citizen (BOTC) to acquire citizenship more easily;

-

Fixing the injustice which prevents a child from acquiring their father’s citizenship if their mother was married to someone else;

-

Introducing a new discretionary adult registration route to give the Home Secretary an ability to grant citizenship in compelling and exceptional circumstances where there has been historical unfairness beyond a person’s control;

-

Creating further flexibility to waive residence requirements for naturalisation in exceptional cases. This will mean Windrush victims are not prevented from qualifying for British Citizenship because they were not able to return to the UK to meet the residence requirements through no fault of their own.

Ending Anomalies in British Nationality Provisions

Until 1 January 1983, women could not pass on British nationality to a child born outside the UK and its then territories. Similarly, until 1 July 2006, children born to British unmarried fathers could not acquire British nationality through their father. While new registration provisions were introduced to rectify these issues for British citizens, they were not applied to children of British Overseas Territories Citizens. This is an injustice so we will now right this wrong and create new registration routes for the affected children of British Overseas Territory Citizens to acquire both British Overseas Territory and British Citizenship.

We will make necessary changes in law so that children entitled to British Citizenship through their biological father (while their mother was married to someone else at the time of their birth) have an entitlement to register for British citizenship, rather than simply relying on a discretionary route to do so.

To help address other cases which seem unjust but do not meet all necessary criteria, we will introduce a new discretionary adult registration route (which already exists for children) so that the Home Secretary can grant citizenship in compelling cases, which would otherwise result in an unfair outcome.

We will also introduce further flexibility to waive residence requirements for naturalisation in exceptional cases. This will help individuals, including members of the Windrush Generation (who were not able to meet the residence requirements to qualify for British Citizenship through no fault of their own), to obtain British citizenship more quickly.

We will also take the opportunity to close a nationality provision loophole which was intended to help those who are genuinely stateless. Under current nationality law a child can acquire British Citizenship under statelessness provisions where they were born in the UK, have lived here for 5 years and have never had another nationality. Recently we have seen an increasing number of parents choosing not to register their child by their own nationality despite being able to do so. In 2015, 10 statelessness applications were received, but this has now grown to over 1,000 per year.

We will now stop this route from being abused by tightening the requirements and actions parents are required to follow before their children are able to benefit from statelessness provisions.

It is right that genuinely stateless children who were born in the UK should be able to acquire British Citizenship, but it cannot be right that others can abuse the system and purposefully not register their children in their own nationality.[footnote 10]

Nationality Anomalies: case studies

A person who was born outside of the UK and Overseas Territories had a non-British father and a mother born in a British overseas territory pre-1983. When the individual was born, women were unable to pass on citizenship to their children, meaning that the individual did not automatically become a British Overseas Territories citizen or British citizen.

In another case, a person was born outside of the UK and overseas territories before 2006. The person’s mother was not British; their father was born in a British overseas territory. The parents were not married. Had the mother been married to the father at the time of the person’s birth, then that individual would have become a British Overseas Territories citizen and British citizen.

The intended reforms would help to resolve inconsistencies in the UK’s Nationality laws, and the impact of this on families.

Chapter 4: Disrupting Criminal Networks and Reforming the Asylum System

Illegal immigration runs counter to our national interest because the same criminal networks responsible for people smuggling are also responsible for other illicit activity ranging from drug and firearms trading to serious violent crimes. If left unchecked, illegal immigration puts unsustainable pressures on public services.

It is also counter to our moral interest as it means people are put in the hands of ruthless criminals who endanger life by facilitating illegal entry via unsafe means like small boats, refrigerated lorries, or sealed shipping containers.

Our asylum system is too easily exploited by people smugglers and does little to disincentivise individuals from attempting to enter the UK illegally.

Because of the various ways in which people with no right to be in the UK can frustrate their removal by filing an asylum claim, the system creates perverse incentives for economic migrants to pay criminals to facilitate dangerous and illegal journeys into the UK and then claim asylum on arrival.

It is unfair that genuinely vulnerable people who have played by the rules and accessed the asylum system via legal routes find themselves in the same position as those who have entered the UK illegally.

The rapid intake of asylum claims into the outdated system has outstripped any ability to make asylum decisions quickly, for the courts to process appeals quickly or for the Government to enforce removal of those with no right to remain in the UK.

This has led to asylum casework growing to unsustainable levels.

There are currently over 109,000 asylum cases in the system. 52,000 cases were awaiting an initial decision at the end of 2020, around 5,200 have an asylum appeal outstanding and approximately 41,600 cases are subject to removal action.[footnote 11]

Successful removals of those with no right to remain in the UK are at the lowest level since 2004. This can be partly attributed to repeated legal protection claims (often without merit and made at the last minute) despite the individual having plenty of opportunities to raise these claims earlier.[footnote 12]

2019 saw the highest level of asylum claims (36,000) since the 2015 migration crisis, with a 21% increase in asylum claims compared with the previous year.[footnote 13] For the year ending September 2019, more than 60% of those claims were from people who are thought to have entered the UK illegally, many of whom passed through safe European countries before making unnecessary and dangerous journeys – including by small boat – to reach the UK.[footnote 14]

In 2020, there were around 15,600 recorded attempted crossings in small boats resulting in around 8,500 arrivals to the UK, all of whom had travelled through France and other EU countries – manifestly safe countries with well-functioning asylum systems.[footnote 15]

To protect life and ensure access to our asylum system is preserved for the most vulnerable, we must break the business model of criminal networks behind illegal immigration and overhaul the UK’s decades old domestic asylum framework. To do so we will take forward reforms to:

-

Ensure those who arrive in the UK, having passed through safe countries, or who have a connection to a safe country where they could have claimed asylum, will be considered inadmissible to the UK’s asylum system;

-

Seek rapid removal of inadmissible cases to the safe country from which they embarked or to another safe third country;

-

Introduce a new temporary protection status with less generous entitlements and limited family reunion rights for people who are inadmissible but cannot be returned to their country of origin (as it would breach international obligations) or to another safe country;

-

Bring forward plans to expand the Government’s asylum estate. These plans will include proposals for reception centres to provide basic accommodation while processing the claims of asylum seekers;

-

Make it possible for asylum claims to be processed outside the UK and in another country by amending sections 77 and 78 of the Nationality Immigration and Asylum Act 2002;

-

Reduce the criminality threshold so that those who have been convicted and sentenced to at least 12 months’ imprisonment, and constitute a danger to the community in the UK, can have their refugee status revoked and be considered for removal from the UK (in line with UK Borders Act 2007 provisions);

-

Support improved decision-making by setting a clearer and higher standard for testing whether an individual has a well-founded fear of persecution, consistent with the Refugee Convention;

-

Create a robust approach to age assessment to ensure we act as swiftly as possible to safeguard against adults claiming to be children and can use new scientific methods to improve abilities to accurately assess age.

Inadmissible Claims and Removal

At the heart of our New Plan for Immigration is a simple principle: fairness. Access to the UK’s asylum system should be based on need, not on the ability to pay people smugglers.

An asylum system should not reward those who enter the UK illegally while other vulnerable people, including women and children, are pushed aside.

We will therefore introduce a new approach. For the first time how somebody arrives in the UK will impact on how their asylum claim progresses, and on their status in the UK if that claim is successful.

Anyone who arrives into the UK illegally - where they could reasonably have claimed asylum in another safe country – will be considered inadmissible to the asylum system, consistent with the Refugee Convention. We will clarify key elements of the Refugee Convention in UK law.

Contingent on securing returns agreements, we will seek to rapidly return inadmissible asylum seekers to the safe country of most recent embarkation.

We will also pursue agreements to effect removals to alternative safe third countries.

We have already taken steps to enshrine these principles in new immigration rules and will now place them on a statutory footing through legislation. This includes ineligibility for EEA nationals (and others from designated safe countries) to claim asylum in the UK, save for exceptional circumstances.

A safe country is one in general where there is no real risk of persecution or harm to individuals sent there, and which will not refoule such individuals. We will introduce a rebuttable presumption that we can return individuals to all EEA member states and other designated safe countries (likely to include countries such as Canada, the USA and New Zealand).

We will continue to pursue returns agreements and arrangements with our international partners as part of future migration partnerships. Every country has an obligation to control its borders, accept and allow entry of its own nationals and to act responsibly to help prevent loss of life and prevent criminal gangs from making a profit from illegal immigration.

We will also amend sections 77 and 78 of the Nationality Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 so that it is possible to move asylum seekers from the UK while their asylum claim, or appeal is pending.

This will keep the option open, if required in the future, to develop the capacity for offshore asylum processing - in line with our international obligations.

Reception Centres and Accommodation

Those deemed inadmissible will be served with a notification upon arrival that the UK will seek to return them to a safe country.

To help speed up processing of claims and the removal of people who do not have a legitimate need to claim asylum in the UK, we plan to introduce new asylum reception centres to provide basic accommodation and process claims. We will also maintain the facility to detain people where removal is possible within a reasonable timescale. The use of hotels to accommodate new arrivals who have entered the UK illegally will end.

The reception centre model, as used in many European countries including Denmark and Switzerland, would provide basic accommodation in line with our statutory obligations, and allow for decisions and any appeals following substantive rejection of an asylum claim to be processed fairly and quickly onsite. We will set in legislation a new fast-track appeals process - with safeguards to ensure procedural fairness.

We will also look to make fuller use of existing immigration bail powers, which provide for residence conditions, reporting arrangements and monitoring.

Temporary Protection Status

If an inadmissible person cannot be removed to another country, we will be obliged to process their claim. If they did not come to the UK directly, did not claim without delay, or did not show good cause for their illegal presence, we will consider them for temporary protection.

Temporary protection status will be for a temporary period, no longer than 30 months, after which individuals will be reassessed for return to their country of origin or removal to another safe country. Temporary protection status will not include an automatic right to settle in the UK, family reunion rights will be restricted and there will be no recourse to public funds except in cases of destitution.

People granted temporary protection status will be expected to leave the UK as soon as they are able to or as soon as they can be returned or removed.

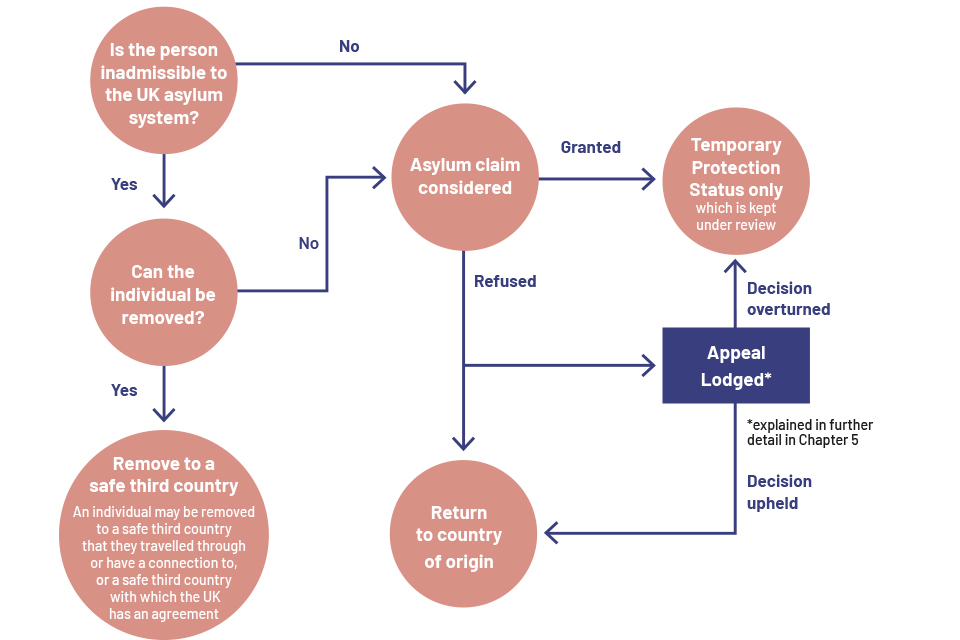

New typical asylum process for individuals who arrive in the UK: at a glance

This chart is for illustrative purposes only, the details at each stage have not been depicted.

if person is admissible their claim is considered and may be granted temporary protection. if inadmissible this will only happen if they can't be removed.

Strengthening Well-Founded Fear of Persecution Test

We want to ensure victims of persecution are properly protected while at the same time making it harder for unmeritorious claims to succeed.

We will therefore consult on a clear test against which any asylum claim can be assessed, putting in place a more rigorous standard for testing the “well-founded fear of persecution” a person must meet.

This test will have two elements. The first element is that the person is who they say they are and that they are experiencing genuine fear of persecution. This will have to be proven to the standard of “balance of probabilities” and will include a credibility assessment, considering all the relevant evidence. This includes consideration of opportunities the person had to claim asylum in other countries. If previous opportunities to make a claim have not been taken, or if a claim is contradictory, that could impact on the credibility of a person’s testimony.

The second element will consider whether the claimant is likely to face persecution if they return to their country of origin. This will need to be proven to the standard of “reasonable likelihood”. If a person claims a persecution risk as a result of being part of a group, they will have to establish that the group is suffering from systematic and widespread persecution. Alternatively, the person who claimed will have to establish a risk that is personal and individual to them.

We will also clarify in statute the definition of “persecution” to make clear the requirements for qualifying for protection, in line with the Refugee Convention.

Assessing Age Appropriately

The Government is committed to protecting children and vulnerable people. But we cannot allow adults to claim to be children. In 2019, the UK received more asylum claims from unaccompanied children than any other European country, including Greece and Italy. Since 2015, the UK has received, on average, more than 3,000 unaccompanied asylum-seeking children per year. Where age was disputed and resolved from 2016-2020, 54% were found to be adults.[footnote 16]

On average, the Home Office provides £46,000 each year to Local Authorities to look after each unaccompanied asylum-seeking child.[footnote 17] We cannot take lightly the very serious safeguarding risks if people over 18 are treated as children and placed in settings, including schools, with children. As well as the obvious safeguarding risks, it also reduces the resources available to help other children.

The UK is one of the only countries in Europe not to use scientific age assessment methods to help determine a person’s age when they arrive into the country. Various scientific methods are used to assess age in, among others, Sweden, Norway, France, Germany and the Netherlands.

We will therefore strengthen and clarify the framework for determining the age of people seeking asylum. We will:

-

Bring forward plans to introduce a new National Age Assessment Board (NAAB) to set out the criteria, process and requirements to be followed to assess age, including using the most up to date scientific technology. Such new age assessment criteria, once proposed by the NAAB, will be set out in secondary legislation. NAAB functions may include acting as a first point of review for any Local Authority age assessment decision and carrying out direct age assessments itself where required or where invited to do so by a Local Authority;

-

Legislate so that front-line immigration officers and other staff who are not social workers are able to make reasonable initial assessments of age. Currently, an individual will be treated as an adult where their physical appearance and demeanour strongly suggests they are ‘over 25 years of age’. We are exploring changing this to ‘significantly over 18 years of age’. Social workers will be able to make straightforward under/over 18 decisions with additional safeguards;

-

Consider creating a requirement on Local Authorities to either undertake full age assessments or refer to people to the NAAB for assessment where they have reason to believe that someone’s age is being incorrectly given, in line with existing safeguarding obligations;

-

Consult on creating a fast-track statutory appeal right against age assessment decisions of the NAAB to avoid excessive judicial review litigation.

Age Assessment: In practice

The current legal process to assess age is highly subjective and often subject to prolonged and expensive legal disputes. Adult claimants can take advantage of a fragmented system to pass themselves off as children, benefitting from additional protections properly reserved for the most vulnerable.

As a result, many adults claim to be children. In some cases, multiple assessments are required before confirming whether an individual is a child or not. The cost of repeated assessments and legal challenges can exceed thousands of pounds of public money. The result is prolonged uncertainty over many months, sometimes years, for the person to be assessed.

Conversely, we have examples of adults freely entering the UK care and school system, being accommodated and educated with vulnerable children.

Our reforms will overhaul the end-to-end process for determining the age of claimants whose age is uncertain, making it more consistent and robust from the outset, whilst harnessing new scientific technologies alongside existing methods. The assessments made will be decisive with any challenge being swiftly and conclusively resolved through a fast-track appeals process.

Chapter 5: Streamlining Asylum Claims and Appeals

We are seeing repeated unmeritorious claims, sometimes made at the very last minute, which frequently frustrate the removal of people with no right to be in the UK – including the removal of Foreign National Offenders (FNOs).

Justice is being delayed for those with genuine and important claims while valuable judicial and court resources are being wasted. We must re-wire the asylum system to ensure that it properly serves vulnerable people in need of protection and that our generosity is not exploited by those with no legitimate claims.

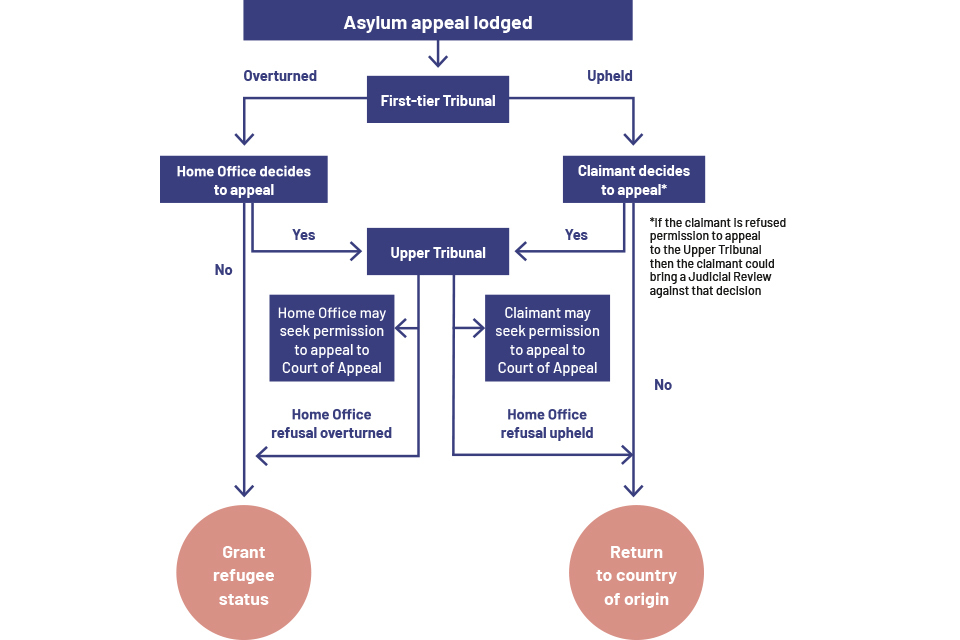

Currently if a person’s asylum claim is rejected, they have an automatic right to appeal the decision by referring it to the First Tier Immigration and Asylum Tribunal. Nearly everyone who has their asylum claim rejected chooses to make this appeal. If the decision is upheld the person claiming asylum has a further route of appeal to the Upper Tribunal. If at that point they are not satisfied with the result, a decision can be appealed again at the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court. It is possible for a person, having exhausted all the above processes, to then bring a fresh new claim, in effect, starting the whole appeal process again.

It is also possible for someone to judicially review a Home Office decision - and they frequently do - at various points in the process, including just before they are about to board a plane for removal.

Simplified typical asylum appeals process: at a glance

This chart is for illustrative purposes only, the details at each stage have not been depicted.

first appeal heard at first-tier tribunal, second appeal at upper tribunal, third at court of appeal

The reality is the system is more complex - people often bring multiple separate claims and subsequent appeals. People also frequently judicially review decisions often at the last minute.

In 2019, there were 8,000 judicial reviews against Home Office immigration and asylum decisions. Judges concluded 6,063 cases on paper, of which 90% were dismissed or refused, with around 17% being deemed by the judge to be “Totally Without Merit”.[footnote 18]

This volume of cases takes up judicial time at all levels. There are many examples of illegal migrants, those without status and Foreign National Offenders, bringing claim after claim of different kinds over a period of years, which are often eventually dismissed. In the meantime, by delaying removal, an individual can acquire additional rights to remain in the UK, such as through marriage or parenting a child.

Last year, over 60 FNOs with no right to remain in the UK were identified for deportation to Jamaica due to serious criminality including offences such as murder, rape and child sexual exploitation. These individuals had extensive opportunity throughout the deportation process to raise any reasons to challenge the deportation action. In the days prior to the deportation flight, following a number of last-minute applications, only 13 FNOs were deported. This meant that the deportation of a very large proportion of cases, including FNOs with more serious convictions, had to be deferred. This is not an exceptional example and occurs on many removal flights.

In one case, a criminal subject to deportation, very late in the process (just before their removal), was able to make three sequential and separate claims to remain in the UK. This included two appeals, which were found to be without merit, and a last-minute asylum claim. The result was that removal from the UK was postponed and delayed.

Repeated claims: In Practice

A person who originally entered on a visa and was granted indefinite leave to remain was subsequently convicted of a serious crime leading to a sentence of over 12 months’ imprisonment. As a result, following the 2007 Borders Act, a Deportation Order was issued. Their subsequent appeal was dismissed by the court. Following the refusal by the court, they made a number of applications across several years to stop the deportation action. These included repeated further applications for asylum and repeated applications for judicial review. All of these applications were refused.

Due to the multiple, often late legal challenges, the individual’s scheduled removal from the UK had to be cancelled on numerous occasions.

Under the changes that this Government intends to make, an improved one-stop process will require further asylum or human rights grounds to be brought together upfront and there will be mechanisms for quickly disposing of unmeritorious claims, allowing for cases to reach their conclusion more swiftly.

In 2019, new claims, legal challenges, or other issues were raised by 73% of people who had been detained within the UK following immigration offences, resulting in release from detention in 94% of cases instead of removal from the UK.[footnote 19]

On full evaluation, very few of these claims amounted to a valid reason to remain in the UK. For issues raised during detention in 2017, 83% were ultimately unsuccessful.[footnote 20]

The number of further submissions applications made by people who are ‘Appeal Rights Exhausted’ (ARE), which means they have no further grounds on which to appeal their original decision, remains high. Whilst further submissions may be based on changes of circumstances since the original claim or appeal, this is not always the case. We want to ensure that people are able to bring all relevant evidence upfront and reduce the ability for claimants to draw out the process by introducing new elements to their claims and launching appeals, meaning they are kept within the system for extended periods of time.

The current appeals system can take years to complete an asylum appeal. As of May 2020, 32% of asylum appeals lodged in 2019 and 9% of appeals lodged in 2018 did not have a known outcome.[footnote 21]

We want to ensure the asylum and appeals system is faster and fairer. Our end-to-end reforms will aim to reduce the extent to which people can frustrate removals through sequential or unmeritorious claims, appeals or legal action, while maintaining fairness, ensuring access to justice and upholding the rule of law. This will achieve efficiencies in the system as a whole - decreasing the costs of unnecessary litigation and failed removal actions for the taxpayer and freeing up valuable judicial resources.

It is right that protection claims which are refused can be challenged, with appropriate oversight by the courts. But it is not right that taxpayers are picking up the bill for sequential unmeritorious claims and appeals, which can frustrate removal of those with no right to be in the UK, and where relevant evidence could have been adduced at the beginning of the appeals process. Our analysis of claims made by those detained and facing deportation indicates that the majority of these claims are unfounded; it is not fair on those with genuine and important claims who are having to wait longer as a consequence.[footnote 22]

We will therefore bring forward a suite of changes to:

-

Develop a “good faith” requirement setting out principles for people and their representatives when dealing with public authorities and the courts, such as not providing misleading information or bringing evidence late where it was reasonable to do so earlier;

-

Introduce an expanded ‘one-stop’ process to ensure that asylum, human rights claims, referrals as a potential victim of modern slavery and any other protection matters are made and considered together, ahead of any appeal hearing. This requires people and their representatives to present their case honestly and comprehensively – setting out full details and evidence to the Home Office and not adding more claims later which could have been made at the start;

-

Provide more generous access to advice, including legal advice, to support people to raise issues, provide evidence as early as possible and avoid last minute claims;

-

Introduce an expedited process for claims and appeals made from detention, providing access to justice while quickly disposing of any unmeritorious claims;

-

Provide a quicker process for judges to take decisions on claims which the Home Office refuse without the right of appeal, reducing delays and costs from judicial reviews;

-

Introduce a new system for creating a panel of pre-approved experts (e.g. medical experts) who report to the court, or require experts to be jointly agreed by parties;

-

Expand the fixed recoverable costs regime to cover immigration judicial reviews (JRs) and encourage the increased use of wasted costs orders in asylum and immigration matters;

-

Introduce a new fast-track appeal process. This will be for cases that are deemed to be manifestly unfounded or new claims, made late. This will include late referrals for modern slavery insofar as they prevent removal or deportation.

Good Faith Requirement

Anyone bringing a claim or a challenge in the courts and their representatives will be required to act in good faith at all times. This means bringing any claims as soon as possible, telling the truth and leaving the UK when they have no right to remain. Failure to act in Good Faith may be considered when the Home Office or judge assess the credibility of someone’s claim, particularly in the context of repeat or unmeritorious claims brought at the point of removal action.

If someone has not acted in Good Faith this should impact the credibility of their claim and testimony both in Home Office decision making and by the courts in any subsequent appeals.

‘One-stop’ Process

A new ‘one-stop’ process will require people to raise all protection-related issues upfront and have these considered together and ahead of an appeal hearing where applicable.

This includes grounds for asylum, human rights or referral as a potential victim of modern slavery. People who claim for any form of protection will be issued with a ‘one-stop’ notice, requiring them to bring forward all relevant matters in one go at the start of the process.

We will introduce new powers that will mean decision makers, including judges, should give minimal weight to evidence that a person brings after they have been through the ‘one-stop’ process, unless there is good reason.

This new process will not bar genuine claims from being considered but it will mean that the credibility of the individual and the weight of their evidence will be considered in light of their previous opportunities to present that evidence.

Appeals against protection or human rights decisions will be to the First Tier Tribunal and then the Upper Tribunal as now and will include modern slavery matters insofar as they prevent removal or deportation. We also want to ensure quicker processes for judges to review refusal decisions by the Home Office when no in-country right of appeal is given. This is intended to provide quick access to an appeal right for meritorious cases, whilst swiftly disposing of unmeritorious claims.

Legal Advice

In order to increase the effectiveness of the ‘one stop’ process and ensure fair access to justice we will consider how access to advice can be improved at different points in the process. This includes ensuring that those prioritised for removal from the UK have access to a new legal advice offer. This new advice offer will support people to bring their claims in one go, when they are notified about removal action, rather than bringing late claims shortly before scheduled removal or sequentially over an extended period of time.

Expedited Appeals

The Government has already taken several steps to streamline the operation of immigration appeals. The Immigration and Asylum Chamber Reform Project seeks to deliver an efficient and transparent service for users of the First-tier Tribunal Immigration and Asylum Chamber (FtTIAC) that is simple, fair and accessible for everyone. Appeals will be progressed online where appropriate and the process will ensure issues are narrowed in a case before the hearing.

For cases that do proceed to a final hearing, hearings will be shorter and more focused. This more efficient appeals system will ensure better value for the taxpayer, free up valuable judicial time and capacity while also preventing unmeritorious appeals that can be a way of preventing removal.

Expedited Appeals from Detention

We want to reinstate an accelerated appeal process that is fast enough to enable claims to be dealt with from detention while ensuring that a person who is detained has fair access to justice. We propose to introduce clear timescales for concluding the process, but it will need to provide safeguards to allow cases to be adjourned or transferred out of the accelerated process when it is in the interests of justice to do so. We will ensure in statute that this process is established.

Fixed Recoverable Costs and Wasted Cost Orders

Most judicial reviews lodged in England and Wales are immigration-related and involve considerable legal costs for the parties and the taxpayer.[footnote 23] In the cases which the Home Office ultimately wins, it is rarely able to recover costs. As part of our measures to promote fairness, certainty and balance to the way in which costs are incurred in these cases, we are considering extending ‘Fixed Recoverable Costs’ to apply to immigration-related judicial reviews. Such a system would specify the amount in legal costs that the winning party can recover from the losing party. By setting this out in advance, both sides will benefit from a greater degree of certainty about the potential cost and risks attached to contesting a case.

We are also considering introducing reforms to encourage the use of Wasted Cost Orders (WCO) in immigration and asylum matters by the court. To achieve this, we propose to introduce a duty on the Immigration and Asylum Chambers of the First-tier Tribunal and Upper Tribunal (FtTIAC) to consider applying a WCO in response to specified events or behaviours, including failure to follow the directions of the court, or promoting a case that is bound to fail. While the grant of a WCO is at the sole discretion of the judge we are considering introducing a presumption in favour of making one. In addition, as WCOs only cover the costs of the parties to the claim, we are also considering introducing a mechanism to cover the court’s costs.

Expert Evidence for Court Proceedings

We want to establish a quicker and higher-quality system of expert evidence to assist the discharge of justice.

At present, a very small number of medical and other experts act in a high proportion of cases where expert witness evidence is provided to the court and are used to produce evidence to corroborate the claimant’s case. We wish to ensure greater confidence in the system by putting the independence of the experts beyond question. We will therefore consider introducing a new system for creating a panel of pre-approved experts (e.g. medical experts) who report to the court or require experts to be jointly agreed by the parties. We want to ensure we are able to support the court with expert, accredited independent witnesses who can provide information so that judges are able to make decisions on cases with the best available information.

The Removals System: In Practice

An individual who was granted Indefinite Leave to Remain in the United Kingdom had that leave revoked following persistent offending leading to a high number of convictions with sentences over 12 months in prison. The individual was subject to a Deportation Order, removing them to their country of origin. This decision was upheld by the courts. On the day that the individual was due to be removed they made an asylum claim, and once that was refused, the individual raised matters to indicate they were a potential victim of modern slavery relating to incidents a number of years prior to their arrival in the UK.

This was referred to the National Referral Mechanism, which is the UK system for identifying and supporting victims of modern slavery. Given the current thresholds and the time taken to make final decisions on these cases (currently an average of c.12 months), the individual was released from detention and removal action was postponed. Following release from detention this individual subsequently absconded and went on to commit further offences.

Chapter 6: Supporting Victims of Modern Slavery

The UK’s response to the evil of modern slavery is world-leading.

The 2015 Modern Slavery Act, pioneered by former Prime Minister, the Rt Hon Theresa May MP, was the first of its kind in Europe.

The Government remains committed to ensuring the police and the courts have the necessary powers to bring perpetrators of modern slavery to justice, while giving victims the support they need to rebuild their lives.

However, over recent years we have seen an alarming increase in the number of illegal migrants, including Foreign National Offenders (FNOs) and those who pose a national security risk to our country, seeking modern slavery referrals – enabling them to avoid immigration detention and frustrate removal from our country.

When the Single Competent Authority, (which operates the National Referral Mechanism (NRM)), has deemed there are Reasonable Grounds (RG) to believe an individual is a victim of modern slavery, they are protected from removal from the UK pending a final decision on their case. Current decision-making times mean this protection from removal is often in place for over 12 months.

While they are protected from removal, they are also entitled to support, until a final Conclusive Grounds (CG) decision is made about whether the individual is a confirmed victim of modern slavery. Protection from removal, compounded by the fact the threshold for an RG decision is low, means release from immigration detention is very likely, resulting in rising abuse of the NRM.

NRM referrals more than doubled between 2017 and 2019 from 5,141 to 10,627.[footnote 24] In 2019, of those referred into the NRM after being detained within the UK (totalling 1,949), 89% received a positive RG decision and 98% were released.[footnote 25] More recently, child rapists, people who pose a threat to national security and illegal migrants who have travelled to the UK from safe countries have sought modern slavery referrals, which have prevented and delayed their removal or deportation.

Given our expectation that referrals will continue to rise, we must act now to reform the system and we will therefore consult on measures to:

-

Identify victims as quickly as possible and enhance the support they receive, while distinguishing more effectively between genuine and vexatious accounts of modern slavery and enabling the removal of serious criminals and people who are a threat to the public and UK national security;

-

Improve the training given to First Responders, who are responsible for referring victims into the NRM;

-

Clarify the definition of “public order” to enable the UK to withhold protections afforded by the NRM where there is a link to serious criminality or a serious risk to UK national security;

-

Strengthen our operational processes for considering Reasonable Grounds decisions and consult on clarifying the Reasonable Grounds threshold to ensure decision-makers can properly test any concerns that an individual is attempting to misuse the system;

-

Fulfil our obligations under the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (ECAT) to continue to identify and protect genuine victims.

Training for First Responders

It is important that First Responders - including Local Authorities, the police and immigration officers - have the training they need to enable them to quickly identify genuine victims and to assess whether an account of modern slavery is credible. We have already launched a new training package to support First Responders in their duties, which covers the issues they should consider when deciding whether to make a referral to the NRM. We will further strengthen the support given to the First Responders working across the immigration system to reinforce their understanding of the indicators of modern slavery whilst also ensuring they are able to assess and raise any concerns about credibility. We want to ensure genuine victims are identified as early as possible and are given the support they need.

Public Order Grounds Exemption

The UK is a signatory of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (ECAT), which sets out our international obligations to identify and support victims of modern slavery. Article 13 provides for a recovery and reflection period to be given to potential victims of modern slavery for a minimum of 30 days, during which they are protected from removal. ECAT contains an exception “if grounds of public order prevent it or if it is found that victim status is being claimed improperly”. However, ECAT does not define such grounds, and the lack of a clear domestic policy on what constitutes this has inhibited deployment of this exemption in the UK. This is resulting in individuals who have committed acts of serious criminality or who may pose a threat to UK national security evading detention and removal from the UK.

We will therefore consult on a definition of “public order grounds” to enable protections of the NRM to be withheld in certain cases and allow removal to occur. We will consult on a draft definition, the focus of which is serious criminality (specifically, where there is a prison sentence of 12 months or more) or risks to national security. The expectation will be that a decision to apply the exemption would be issued alongside the RG decision where relevant, ensuring a recovery period is not granted to an individual inappropriately. However, it could be made later if information comes to light suggesting an exemption applies.

This will bring the UK in line with other ECAT signatories. For example, Germany states that a recovery period need not apply if the continued stay of the foreign national would be detrimental to public safety and order or other substantial national interests.

A new Reasonable Grounds Test and Credibility

ECAT also states that support should be provided where a signatory finds “reasonable grounds to believe” that an individual has been a victim of trafficking. However, the test for an RG decision in the UK, as set out in the Modern Slavery Act 2015, is that we have “reasonable grounds to believe that a person may be a victim” and in the Statutory Guidance published under Section 49 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 is “I suspect but cannot prove” that the person is a victim of modern slavery – a lower threshold.

We will therefore consult on amending the Modern Slavery Act 2015 definition to “reasonable grounds to believe that a person is a victim” and will also consult on amending the Statutory Guidance definition to make clear that the test applied in practice will be “reasonable grounds to believe, based on objective factors but falling short of conclusive proof, that a person is a victim of modern slavery”.

We will also confirm for the first time in legislation that the balance of probabilities is the right threshold for the Conclusive Grounds (CG) decision. ECAT provides for a two-stage identification process to confirm whether or not someone is a victim of modern slavery, and it has been upheld in the courts that the final CG decision should be made on the balance of probabilities.

For both decision points, we will make clear in associated guidance that the threshold will not be met on the basis of an unsubstantiated claim. In making both RG and CG decisions, we will consider providing for a more careful analysis of credibility, including carefully considering the implications of contradictions and previous opportunities to have raised modern slavery matters. It will be expected that any modern slavery issues which have a bearing on immigration status should be raised as part of a ‘one-stop’ process where relevant.

We will also consult on seeking bilateral or multilateral agreements with safe, ECAT-signatory countries which would enable the removal of victims of modern slavery ensuring their needs are met in the country to which they are removed in line with our obligations under ECAT.

Providing Victims of Modern Slavery with Increased Support

As well as acting to prevent abuse of the NRM, it is also right that we consider options to improve the assistance we provide to victims of modern slavery.

For some victims, certainty over their immigration status is a crucial enabler to their recovery and to assisting the police in prosecuting their exploiters.

We will make clear, for the first time in legislation, that confirmed victims with long-term recovery needs linked to their modern slavery exploitation may be eligible for a grant of temporary leave to remain (subject to any public order exemption) to assist their recovery, building on our end-to-end needs-based approach to supporting victims. We will also make clear that temporary leave to remain may be available to victims who are helping the police with prosecutions and bringing their exploiters to justice.

When Parliamentary time allows, we will also clarify our international obligations to victims in UK law to ensure victims are safeguarded and supported based on their individual modern slavery related recovery needs and ensure robust, effective and meaningful decision-making. This will include provisions to enable flexibility in future delivery models.

We will continue to strengthen the criminal justice system response to modern slavery and will be providing further funding to drive forward work to increase prosecutions and build policing capability to investigate and respond to organised immigration crime. A key focus of this work will be ensuring that victims of modern slavery receive the support they need to engage in the criminal justice system to ensure that perpetrators face justice. We are considering testing a new approach which would involve embedding specialist workers within police forces to support victims and law enforcement officers on investigations.

To prevent people from being drawn into this terrible crime, we will also consider establishing a modern slavery prevention fund. This will bolster our efforts to eradicate modern slavery by supporting interventions by non-governmental organisations and key practitioners to tackle this heinous crime at its source.

We will also ensure that modern slavery victims receive ready access to specific mental health support to help them recover from their experiences of exploitation. We are already putting in place an enhanced needs-based assessment that will ensure that victims receive holistic support and assistance to aid recovery, including private counselling and mental health support where appropriate.

From January to September 2020, there were 1,041 NRM[footnote 26] referrals for exploitation linked to county lines, which is over 6 times the number of referrals received in the same period in 2017. 89% (925) of these referrals were for UK nationals (including dual nationals) and the vast majority were for males who were exploited as children. We will improve our support for child victims of modern slavery, including those involved in county lines and other types of exploitation. We are already rolling out the Independent Child Trafficking Guardians (ICTGs) service, which provides advice and support for trafficked children, irrespective of nationality, and who can advocate on a child’s behalf. The delivery model includes a Regional Practice Co-ordinator (RPC), who offers expert advice to professionals working directly with trafficked children, including county lines cases, on how best to safeguard and support children in their care.

We will also pilot a new way of identifying child victims of modern slavery, which will enable decisions to be taken within existing safeguarding structures by local authorities, police and health workers, who have a duty to work together to safeguard and promote the welfare of all children. This approach will enable decisions about whether a child is a victim of modern slavery, including through county lines exploitation, to be made by those involved in their care. It will ensure the decisions made are closely aligned with the provision of local needs-based support and any law enforcement response.

Finally, we will review the Government’s pioneering 2014 Modern Slavery Strategy in order to develop a revised strategic approach that builds upon the considerable progress we have made to date, adapting to the evolving nature of these terrible crimes. This will allow us to identify victims at the earliest opportunity and to ensure that support and protection is focused on those who need it most.

Abuse of Modern Slavery Protections: An Example

An individual who had entered the UK illegally was convicted of a string of offences, including drugs supply. The individual was sentenced to several years in prison and under the 2007 Borders Act was subsequently deported from the UK.

Within a few months, the individual returned to the UK in breach of the deportation order and was encountered by the police. The individual was deported from the UK again but subsequently returned and made a protection claim. The protection claim was refused and the individual was detained in preparation for removal. Whilst in detention the individual raised matters indicating they may be a victim of modern slavery and was referred into the National Referral Mechanism (NRM). The individual’s account met the Reasonable Grounds (RG) threshold and a positive decision was made. Due to the positive RG decision, the individual was released from detention and is still in the UK, receiving protections under the NRM.

Chapter 7: Disrupting Criminal Networks Behind People Smuggling

Illegal immigration is facilitated by serious organised criminals exploiting people and profiting from human misery. The same criminal gangs and networks are also responsible for other illicit activity ranging from drug and firearms trafficking to modern slavery and serious violent crimes.

We are already working extensively with our partners in Europe, especially France and Belgium, to prevent migrants attempting to make their way illegally to the UK. This includes work funded through overseas development aid and activities of law enforcement and intelligence partners including the National Crime Agency (NCA). We will continue to work with them and all operational partners and agencies to tackle the upstream causes of illegal immigration.

The criminals that facilitate dangerous and illegal journeys into the UK endanger the lives of those that undertake them. They also endanger the lives of emergency service workers and Border Force officers who are called out to respond to them.

It is unacceptable that people seeking to enter our country illegally, including those who have crossed the Channel by small boat, are not appropriately penalised for breaking the law. Tougher penalties would also deter some people from undertaking these dangerous journeys altogether, especially where they originate from manifestly safe European countries with well-functioning asylum systems like France.

Last year, a young family including children lost their lives at sea trying to cross the Channel by small boat. In 2019, 39 people lost their life attempting to enter the country in a sealed refrigerated cargo container.

It is unacceptable that the criminals responsible for people smuggling are not always adequately penalised for their harmful and life-endangering actions.

To stop the deaths, we must break the business model of the people smugglers. To do so we must better deter illegal migration and strengthen the protection of our borders. We will therefore:

-

Introduce tougher criminal offences for those attempting to enter the UK illegally including raising the penalty for illegal entry;

-

Widen existing powers to tackle those facilitating illegal immigration, through acts like piloting small boats, including raising the maximum sentence for facilitation to life imprisonment;

-