Digital identity and attributes consultation

Updated 3 February 2023

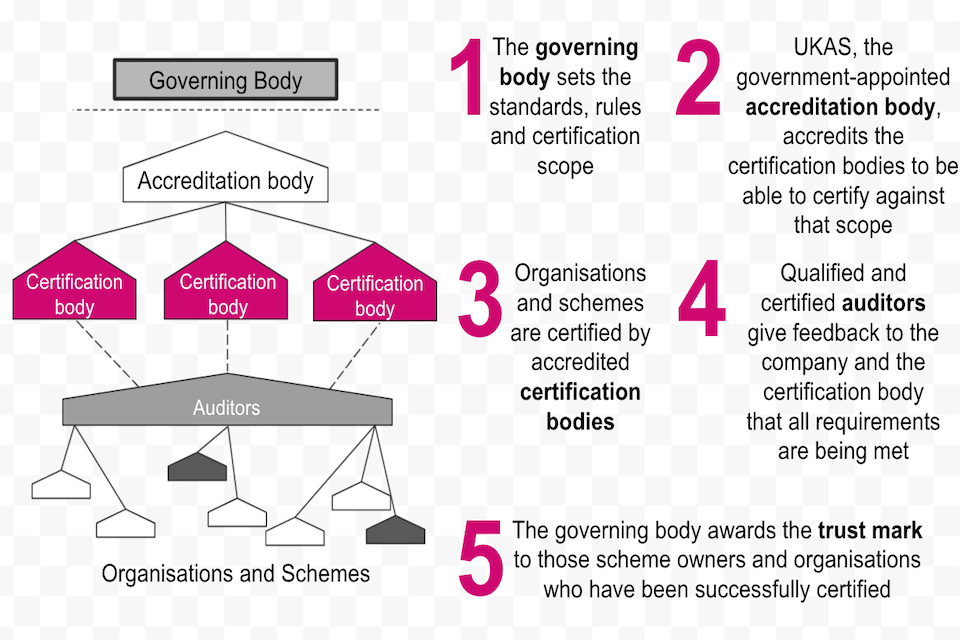

This consultation has concluded. The government response to the digital identity and attributes consultation was published in March 2022.

Ministerial foreword

A picture of Matt Warman MP, Minister for Digital Infrastructure, standing outside the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

A picture of Julia Lopez MP, Minister of State for Media, Data, and Digital Infrastructure at the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport.

Our economy is becoming increasingly digital. Use of data is driving innovation and boosting productivity. This government is committed to harnessing the power of responsible data use, enhancing growth, and ensuring that data works for everyone — this was set out in the National Data Strategy.

Digital use of personal identity information can be part of this journey. If someone wants to prove who they are when starting a job, moving house, or transacting online, they ought to have the tools do so quickly and securely in a digital manner, as an option alongside using the physical documents we are most familiar with.

Too often, people in the UK have to use a combination of paper documents issued by government, local authorities and the private sector — and a mixture of offline and online routes — when they need to prove something about themselves. And they have to repeat the process for each new transaction.

Online authentication, identity and eligibility solutions can increase security, ease of use and accessibility to public services. They are central to transforming the delivery and efficiency of public services and people’s ability to operate confidently in an increasingly digital economy. It is estimated that widespread use of digital identity products would be worth around £800m per year to the UK economy. Widespread use of digital identity products could also help to reduce the record levels of abuse of personal data and impersonation to commit fraud in the UK, with over 220,000 cases reported in 2019.

The government is committed to realising the benefits of digital identity, without creating ID cards. Earlier this year we published a draft of the UK digital identity and attributes trust framework. This document sets out what rules and standards are needed to protect people’s sensitive identity data when used digitally. We will put in place the necessary framework and tools so that digital identity products enhance privacy, transparency, confidence and inclusion, and that users are able to control their data, in line with the principles published in the 2019 Call for Evidence response. We are also developing and piloting a new ‘One Login for Government’ system that will make it easier for everyone to access government services, with users only having to provide data to prove their identity once, and protecting privacy throughout.

It’s vital that we move quickly to keep pace with our international partners. We want people to be able to interact securely across borders and we want to ensure our businesses can compete globally; enabling the use of secure digital identity products is key to these ambitions.

We promised to follow up on other aspects of our Digital Identity Call for Evidence at pace, and this consultation does that now, seeking views on three key issues.

Firstly, to support the trust framework there will need to be a responsible and trusted governance system in place which can oversee digital identity and attribute use and make sure organisations comply with the rules contained within the trust framework. We are using this consultation to solicit views on the exact scope and remit of this governing body. As the consultation makes clear, it will be vital to ensure that this body works closely with other regulators that have oversight of digital services, and supports our wider goals of establishing a coherent regulatory landscape that unlocks innovation and growth.

Secondly, to unlock the benefits digital identities can bring, we need to make it possible to digitally check authoritative government-held data. We need the digital equivalent of checking data sources such as a passport. That’s why we are also consulting on how to allow trusted organisations to make these checks.

Finally, we want to firmly establish the legal validity of digital identities and attributes, to build confidence that they can be as good as the physical proofs of identity with which we are familiar.

We continue to work in an open and transparent way, building on the feedback we receive. Industry, civil society, international and academic stakeholders have been vital to the creation of this consultation, and the trust framework. For these tools to deliver the economic, security and privacy benefits for the UK, they need to be trusted — by business, by regulators and most importantly by people. That is why it is so important we get this right.

We look forward to hearing your views on these latest proposals.

Matt Warman

Minister for Digital Infrastructure, Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

Julia Lopez

Parliamentary Secretary, Cabinet Office

How to respond to this consultation

This consultation has concluded. The government response to the digital identity and attributes consultation was published in March 2022.

1. Introduction

1.0.0.1 When you want to prove something about yourself — your age, your nationality, or who you are — you may instinctively turn to a government issued identity document such as a passport. These physical documents are issued following extensive checks and identity checking processes are centred on them.

1.0.0.2 However, by being physical documents they are inherently limited. If you are required to send your passport in the post it could get lost, or you may incur costs to send it via special delivery. If you need to scan a document, the image may be blurry or not of the appropriate file size. You may not keep certificates proving your qualifications to hand.

1.0.0.3 Current identity checking methods can also be costly for business. It takes time and effort to process these documents manually.

1.0.0.4 Digital access to the attributes these documents contain can solve these issues. It can also have benefits such as improving inclusion. If you do not have a passport, perhaps another government service can validate your age. There are also opportunities for data minimisation by disclosing only that information which is required (for example, that you’re over 18), rather than full disclosure of your data, including your date of birth, name, or address.

1.0.0.5 This consultation sets out our policy aims and where we think legislation can help grow digital identity and attribute use in line with the government’s principles developed from the Call for Evidence.

A principles-based approach to digital identity and attributes

| 1) Privacy - When personal data is accessed people should have confidence that there are measures in place to ensure their confidentiality and privacy; for instance, a supermarket checking a shopper’s age, a lawyer overseeing the sale of a house or someone applying to take out a loan. |

| 2) Transparency - When an individual’s identity data is checked through use of digital identity and attribute products, they must be able to understand what was checked, by who, why and when; for example, being able to see how your bank uses your data through digital identity solutions. |

| 3) Inclusivity - People who want or need a digital identity should be able to obtain one; for example, not having documentation such as a passport or driving licence should not be a barrier to having a digital identity. |

| 4) Interoperability - There needs to be agreed technical and operating standards across the UK’s economy to define what good quality digital identity products look like. |

| 5) Proportionality - User needs and other considerations such as privacy and security should be balanced so digital identity can be used with confidence across the economy. |

| 6) Good governance - Digital identity and attribute standards should be linked to government policy and law. Any future regulation will be clear, coherent and align with the government’s wider strategic approach to digital regulation. For example, firms verifying your identity will need to comply with laws around how they access and store data. |

1.1 Background

1.1.0.1 In 2019 the government opened a Call for Evidence seeking views on how digital identity could support individuals to prove things about themselves digitally where they usually relied on paper processes. The overwhelming majority of responses supported increasing the use of digital identity across the economy.

1.1.0.2 Respondents identified several benefits including increased service options, greater security and the ability to prove entitlement or eligibility in a privacy friendly way.

1.1.0.3 The Government’s formal response to the Call for Evidence, published in September 2020 outlined several areas where government leadership could enable businesses and individuals across the economy to use digital identities securely and with more confidence.

1.1.0.4 As part of our commitment to growing digital identity and attribute use across the economy, we are running a pilot to test how to unlock government held data in a privacy friendly way.

The Document Checking Service (DCS) Pilot, a joint initiative between the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, the Government Digital Service and HM Passport Office, allows non-public sector organisations to check if a British passport is valid or not. The pilot was set up to:

- test the industry demand for checking information given by a user against government-held data sources

- understand the different ways that organisations could use digital passport checks

- test the technical design that would make these checks possible

- capture consumer interest and experience of these checks, and perception of this use of passport data

- understand if this is commercially viable, for the government and the organisations taking part

The pilot allows participating organisations to send a user’s passport details — with the user’s consent — to the DCS and receive back a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response, depending on if the passport is valid or not. No organisations are given direct access to government-held data. Participating organisations had to undergo a rigorous application process and must make checks for the purpose of reducing crime.

1.1.0.5 In February 2021 a first, draft version of the UK digital identity and attributes trust framework was published. The trust framework is a set of requirements for creating good quality digital identity products which ensure people’s data and privacy are protected. An update to the document will be published soon and will contain/has been published and contains details on certification, among other updates.

The trust framework is designed to be an evolving set of requirements to build and maintain trust in digital identities in the UK, and to support an ambition for UK digital identities to be trusted overseas in the future. The development process for the trust framework included researching other international efforts to develop and deliver digital identity models and frameworks in both the public and private sector.

We have liaised with international teams across the UK government including foreign affairs, economic, finance, and trade teams, and engaged with other governments and international partners. DCMS continues to research and benchmark the development of its digital identity policy and strategy against broader international efforts as we iterate the trust framework, governance framework and legislative model.

1.2 Proposal

1.2.0.1 Private sector digital identity providers already exist and individuals interact with digital identity in lots of formats already, such as when logging into online banking. However, for products to be useful across a range of services, organisations need a digital way to check the attributes held in authoritative government-held data for eligibility and identity purposes.

An attribute is a piece of information that describes something about a person or an organisation.

- ‘George has passed his driving test’ is an attribute of George

An eligibility check asks whether a particular person or organisation has a particular attribute.

- Is this person over eighteen years old? Calculated from ‘date of birth’ attribute

- Is this person eligible to drive? Answered by ‘passed driving test’ attribute

An identity check asks who a person or organisation is.

- Are you this particular natural or legal person? Determined to an agreed level of assurance from a variety of attributes

Examples

- When buying alcohol you only need to undergo an eligibility check. What matters is that you are over eighteen — who you are is immaterial.

- When opening a bank account, however, you will need to undergo eligibility checks — are you of sufficient age, for example — as well as an identity check.

1.2.0.2 Digital checking will reduce friction in transactions, and speed up instances where eligibility or identity is checked via paper certification, such as during the home buying process. The current home buying process can be delayed due to the need to prove identity multiple times, potentially to different standards. It also requires individuals to pay fees to have documents like a passport officially certified.

1.2.0.3 Access to government-held data is just one part of realising the benefits from digital identity for individuals and organisations. We also need to ensure there are robust and standardised protections for privacy, for security, and to build confidence in digital identity and attribute products. We are doing this both via the trust framework and also in our vision for a governing body which will continue to set standards as technology changes.

1.2.0.4 This consultation explains our thinking on the legislative measures and policy interventions needed to create an enabling digital identity and attributes framework in the UK. It has three parts:

1.2.1 Creating a digital identity governance framework

1.2.1.1 This section describes a possible model of governance which will meet the needs of all parties. The aim of the proposal is to balance proportionate regulation with security, consumer protection and trust, according to the scale of digital identity use.

1.2.2 Enabling a legal gateway between public and private sector organisations for data checking

1.2.2.1 This section sets out our intent for a permissive legal power to allow digital identities in the UK to be built on a greater range of trusted datasets and for government-held attributes to be checked for eligibility, identity, and validation purposes. Organisations making such checks must have a correct lawful basis under the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to do so.

1.2.3 Establishing the validity of digital identities and attributes

1.2.3.1 This section proposes how we could build confidence in the legal validity of digital identities and attributes alongside the physical proofs of identity that businesses and individuals already trust, as part of our commitment to increase choice and confidence.

1.2.3.2 We welcome your feedback on this consultation exercise.

2. Creating a digital identity governance framework

2.0.0.1 The government is committed to creating a clear legal framework for digital identity and attribute use that enables businesses to innovate and allows people to access the goods and services they want with ease. Effective governance will build a trusted ecosystem for the safe use of digital identities across the economy and, through that trust, will drive innovation and growth in the UK economy. Good governance will ensure the digital identity and attribute principles are upheld.

2.0.0.2 For these reasons we are proposing the following high level objectives for governance

- Create value in a manner that is proportionally beneficial to all stakeholders

- Foster innovation by ensuring that requirements are proportionate to enable market entry and growth

- Enable interoperability to ensure optimal outcomes from the perspective of the end-user/data subject

- Enable inclusion by promoting inclusive and accessible solutions especially for end-users

- Maximise trust by ensuring personal data privacy through adherence to required standards

- Carry out the above objectives in a way that is both financially and functionally sustainable.

2.0.0.3 The governance framework we envisage will create regulatory functions within an existing regulator and will need to be set out in legislation. Placing these functions within an existing regulator ensures the regulator has the experience, status and powers to give sufficient oversight and offers economies of scale by reducing costs associated with setting up a brand new stand-alone regulator.

2.0.0.4 We envisage a tiered system wherein individual organisations can be part of this governance framework by being certified against the trust framework or they can join as part of a sector-specific scheme. The role of schemes was first set out in the draft version of the trust framework. We will be asking questions throughout this consultation about what responsibilities should be delegated to the operators of these schemes.

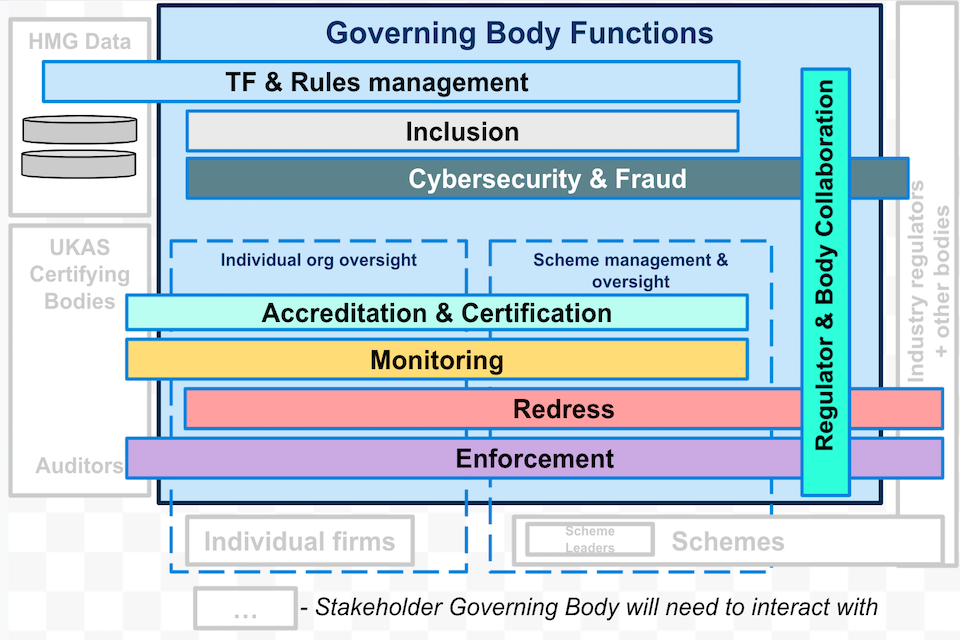

2.0.0.5 We want the governing body to do the following, however there are different ways these could be achieved, and we will ask questions about this in subsequent sections:

- Ongoing management of the trust framework. The governing body will run the trust framework and update its requirements to ensure they remain fit for purpose as technology evolves.

- Set up and provide oversight of accreditation and certification processes so qualifying organisations prove compliance with a trust mark. Organisations will need to prove that they are trustworthy and capable, and do this by demonstrating that they abide by the trust framework requirements. The governing body will set up a certification framework and appoint an authority to accredit certifying bodies who will then assess and certify participants of the trust framework.

- Monitor compliance and performance. Auditor’s working for accredited certification bodies will monitor organisations’ and schemes’ compliance to the requirements of the trust framework, reporting into the governing body. The governing body will need to monitor the performance of the certification framework.

- Oversee member organisations and the management of schemes. The governing body will need to oversee individual member organisations and scheme owners to ensure both are maintaining the standards of the trust framework.

- Promote consumer protection by managing enforcement, complaints, and redress. If something goes wrong which can’t be resolved either within the scheme or organisation’s usual complaints processes or by contract law — or if a trust framework member does not follow the specified requirements — then the governing body will intervene, and in serious cases remove the trust mark. Where an issue is covered by existing regulatory duties the body may operate a triage function and signpost organisations and citizens to other regulators as appropriate.

- Collaborate with stakeholders and other regulators. The governing body will need to collaborate with cross-sector and industry regulators; national and international bodies; security and fraud groups; privacy groups; and government departments.

- Maximise cybersecurity and minimise fraud. The governing body will use requirements in the trust framework and collaboration with law enforcement and regulators to maximise cybersecurity and minimise fraud. It will work with trust framework participants to increase the prevention of incidents and promote swift action to tackle suspicious activity.

- Promote and encourage inclusion. The governing body will aim to ensure that the activities within the UK’s digital identity ecosystem promote inclusivity by building additional inclusion considerations into the trust framework and its certification processes, and act if it identifies certain groups being excluded from digital activities or services without justification.

A chart showing how the governance framework will operate, as described in the previous paragraphs 2.0.0.1 to 2.0.0.5.

2.1 The governing body

2.1.0.1 We are seeking views in this consultation on which regulator should house the governing body for digital identity as no decision has yet been made. Consultation responses will help inform that decision.

2.1.0.2 We believe that there is benefit to empowering a single regulator to undertake all of the governance functions outlined above. To split the functions between bodies would complicate the regulatory landscape and confuse people and organisations as to who they should go to. Any regulator which is to take on the governance functions should already carry out some of the required regulatory functions outlined below.

2.1.0.3 Housing these functions within an existing regulator would also avoid the steep costs associated with creating a new regulator, providing value to the taxpayer, and allow for greater flexibility as the digital identity market grows.

2.1.0.4 To ensure the governing body is transparent it will be required to publish reports on its progress and actions and on the performance of the digital identity market against the trust framework rules and standards, and may be commissioned by the government to produce one-off reports in areas of interest.

2.1.0.5 This regulator will of course need to collaborate with other relevant regulators, such as the FCA and Ofcom, and agree regulatory practices with other industry regulators who use digital identities within their sectors. The government is currently exploring how they can support and strengthen collaboration between the key digital regulators to address such interactions, building on evidence recently supplied by the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum.

2.1.0.6 Digital identity governance will need to operate across the economy as well as be used within sector based industries, such as financial services or home buying & conveyancing. Pan-economy harms regulators can operate across the economy to enforce measures which protect citizens and mitigate harms. Examples of regulators like this include the Information Commissioner’s Office, the Competition and Markets Authority and the Equalities and Human Rights Commission. Sector focused regulators operate in specific areas of the economy or areas of activity, examples of this are the Planning Inspectorate, the Health and Safety Executive and the new Digital Markets Unit (DMU) which will be created within the CMA to operationalise the future pro-competition regime for digital markets.

2.1.0.7 As the programme of reform is delivered, appropriate government approval processes, including in relation to arm’s-length bodies, will be followed.

- Do you agree an existing regulator is best placed to house digital identity governance, or should a new body be created?

- Which regulator do you think should house digital identity governance?

- What is your opinion on the governance functions we have identified as being required: is anything missed or not needed, in your view?

2.2 Trust framework, standards and rules management

2.2.0.1 In February 2021 DCMS published a first, draft version of the UK digital identity and attribute trust framework. Its second draft has been published/will be published and contains details on the certification process, among other updates. The trust framework, once finalised, will lay out a set of requirements organisations must follow in order to join. The framework includes requirements on areas such as:

- creating and using digital identities

- how organisations should handle and protect personal data

- what security and encryption standards must be followed

- how user accounts should be managed

- how to protect against fraud and misuse

2.2.1 Setting standards and legal requirements

2.2.1.1 As our digital world continues to evolve we expect that the requirements within the trust framework will need periodic refreshing and updating to ensure they keep pace with external changes, trends, and technical and service innovation. The need for this to be reactive and flexible means we do not propose to enshrine these requirements directly in legislation. Instead we propose that the governing body is given a legal responsibility to own and run the trust framework and any associated guidance incorporated into it.

2.2.1.2 We also propose that related government-owned guidance, including Good Practice Guide (GPG) 44 and GPG 45, should be fully incorporated into the trust framework.

2.2.1.3 We propose that updates to standards, requirements or associated guidance will not necessarily need to be made by the governing body itself. The governing body may arrange for the updates to be made by others, whilst remaining in overall oversight and ownership.

4.What is your opinion on the governing body owning the trust framework as outlined, and does the identity of the governing body affect your opinion?

5.Is there any other guidance that you propose could be incorporated into the trust framework?

2.2.2 Scope of the trust framework

2.2.2.1 Governance will only apply to those operating within the trust framework, and membership of the trust framework will be voluntary. However, only organisations with accredited certification against the trust framework will be granted permission to use a trust mark to prove their product or service meets government-recognised requirements for digital identity.

2.2.2.2 In section 3.1, we also propose that certification against the trust framework should be a requirement before organisations make checks against government-held data through the proposed legal gateway.

2.2.3 Collaboration with interested parties

2.2.3.1 As mentioned, the governing body will also need to update and refresh the trust framework as technology and security practices change. We envisage the governing body managing this process, even if the technicalities of such a refresh are delegated. We also expect the governing body to consult with interested parties, regulators, and advisory groups, including the government itself, on any updates to standards.

2.2.3.2 To ensure that the rules and standards outlined in the trust framework remain relevant, up to date, and in line with international standards, we envisage the governing body will set up advisory groups to help support it in its role; these groups will advise the regulator at senior executive or board level and may include representation from industry, scheme owners, privacy, civil society and consumer groups. These advisory groups will be in addition to any consultations on updates to the trust framework and its requirements.

6.How do we fairly represent the interests of civil society and public and private sectors when refreshing trust framework requirements?

7.Are there any other advisory groups that should be set up in addition to those suggested?

2.3 Accreditation & certification

Accreditation is the formal recognition by an independent body that a certification body operates according to recognised standards. Accreditation demonstrates to the marketplace that certification bodies are technically competent to audit and certify activity in accordance with the requirements of national and international standards and regulations.

Certification is the provision by an independent, accredited body of written assurance (a certificate) that the product, service or system in question meets specific requirements. The independent assurance is undertaken by an accredited certification body.

2.3.0.1 There needs to be a robust means for organisations to prove that they follow the rules and standards as set out in the trust framework, and thus can be trusted by people. Accredited certification is the standard way to achieve this. In the context of the trust framework, accredited certification means that an organisation has been independently assessed as meeting the requirements set out in the trust framework.

A chart showing how the certification framework will operate, as described in section 2.3

2.3.0.2 We are planning for the governing body to own this certification framework. We are also planning to appoint the UK Accreditation Service (UKAS) to accredit certifying bodies using ISO 17065:2012 (Conformity assessment — Requirements for bodies certifying products, processes and services) to manage the certification process. UKAS will set out an open application process through which interested certification bodies can apply in due course.

2.3.0.3 We will soon publish further details about certification in an update to the trust framework and assess the approach through robust testing.

2.3.1 Trust mark and trusted list

2.3.1.1 Upon successful certification, the governing body will award a ‘trust mark’ to certified scheme owners , scheme members and individual organisations. This trust mark will signify to members of the public and other organisations that products and services which display the trust mark have been audited to confirm they follow the trust framework requirements.

2.3.1.2 The governing body will also be required to publish a register of trust framework participants showing the certification status, any membership of scheme(s), and when the trust mark was awarded. The register will be kept up to date, available on the governing body’s website, and be available to anyone who wants to view it. This register would be particularly useful for consumer protection purposes by allowing relying parties and citizens to assure themselves of valid trust framework membership and trust mark status, similar to that for Qualified Trust Service Providers under the UK eIDAS Regulations. Under these Regulations a list is published and maintained of qualified trust service providers who are organisations providing qualified trust services and that have been granted qualified status by the ICO.

2.3.2 Fees and funding

2.3.2.1 The governing body will also be empowered to collect fees from trust framework members and scheme owners to support and go towards covering the costs of its functions. There could be a one-off entrance fee for first joining the trust framework, and/or an ongoing annual membership fee. The costs behind this are still being considered.

- How should the government ensure that any fees do not become a barrier to entry for organisations while maintaining value for money for the taxpayer?

2.4 Monitoring compliance & performance

2.4.0.1 To ensure organisations and schemes are meeting the trust framework requirements, the governing body will have the legal responsibility for confirming their continued compliance post-certification. The governing body will need to oversee and manage a monitoring system for trust framework members. This will assess continued adherence of organisations and schemes to the trust framework.

2.4.0.2 In line with the standard approach to certification elsewhere, we believe that the governing body should delegate the operational aspects of this power to accredited certification bodies employing suitably qualified certified auditors, accredited as set out in the previous section. This choice will lower the time investment required for the governing body while also allowing for high quality monitoring. To maintain an appropriate level of oversight, the governing body will put in place reporting arrangements with the certification bodies to ensure it is kept abreast of high level information about certification body activities.

2.4.0.3 Costs for these audits will be borne by the trust framework organisation being audited through a contractual relationship with their chosen certification body. This is in addition to any fees paid directly to the governing body to join the framework.

2.5 Oversight/Management of organisations/schemes

Information about schemes

Organisations can use the UK digital identity and attributes trust framework:

- by themselves as a single organisation

- as part of a ‘scheme’

A scheme is made up of different organisations who agree to follow a specific set of rules around the use of digital identities and attributes. These organisations might work in the same sector, industry or region, which means they will build products and services for similar types of users. A scheme can help organisations work together more effectively by making it easier for them to share information. They can do this by adding additional requirements to the rules of the trust framework which will only be applicable to that scheme.

A scheme is created and run by a scheme owner. The scheme owner sets the rules of the scheme. This is known as a ‘scheme specification’ and must be based on the rules of the trust framework. It could include:

- what roles are available in the scheme

- how members should work together

- how members should process data about their users

- how members can work to create interoperability between schemes

There are a number of schemes currently in development in the UK. These will operate in a range of sectors like financial services, the employment sector, and age verification amongst others.

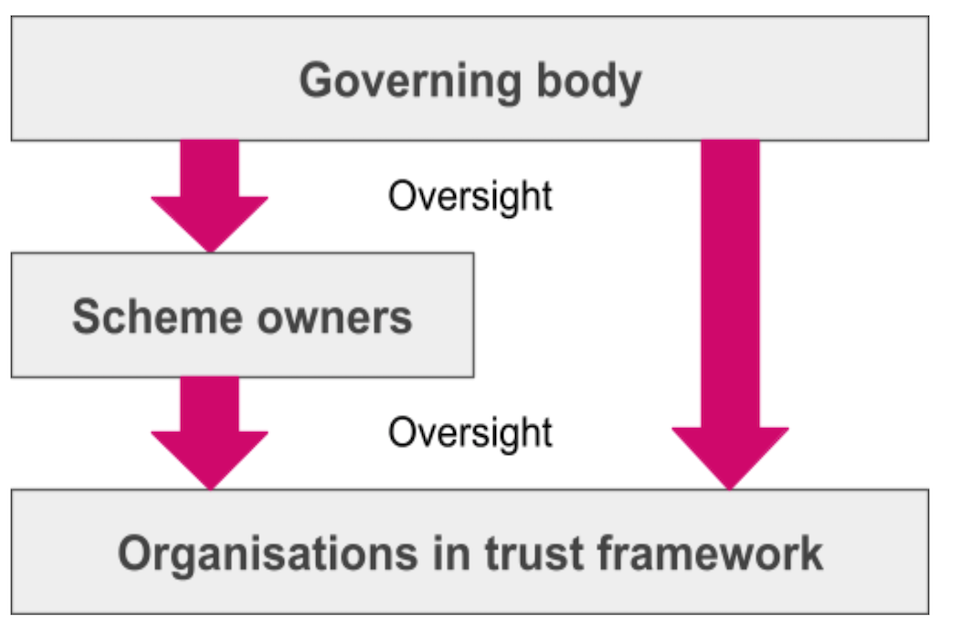

2.5.0.1 We envisage that the governing body will take a two-layered approach to governance. We expect that scheme owners will provide governance of their scheme and solve any internal problems which arise. The governing body will then oversee these scheme owners to ensure their role is performed satisfactorily. If the scheme owner cannot provide a resolution then the issue will be escalated to the governing body. The governing body will also oversee directly any individual organisations who are not part of a scheme, ensuring their compliance with the trust framework. This two-layered approach will ensure the governance model can react flexibly to the market developing. Allowing organisations to join both directly and via a scheme will enable the market to develop at pace and best meet the needs of those using the trust framework. The approach will be kept under review as the ecosystem matures.

A chart showing how oversight of the scheme will work, with the governing body having oversight of the scheme owners, and the scheme owners and governing body having oversight of organisations in the trust framework.

2.5.0.2 Through its role in certification and awarding of the trust mark, the governing body will have approval over scheme creation by certifying scheme owners. Depending on the nature and maturity of a scheme, and developing policy around the trust framework, a scheme may also become accredited in its own right through developing an accredited certification scheme.

9.Do you agree with this two-layered approach to oversight where oversight is provided by the governing body and scheme owners?

2.5.0.3 The governing body will have responsibility for the safe growth and development of the digital identity ecosystem. However, the presence of schemes and scheme owners may affect how the governing body oversees organisations. The governing body will need to ensure that there are no compromises to how the trust framework requirements are being met by industry, but some responsibility for certification and monitoring may sit with the scheme owner. The governing body will have responsibility for ensuring scheme owners and schemes are complying with the standards and principles of the trust framework.

2.6 Complaints, redress and enforcement

2.6.0.1 The UK government will empower the governing body to ensure that the right rules and processes are in place to limit instances in which things go wrong and to maintain the security of the digital identity ecosystem. But it would be unrealistic to expect to completely eliminate the risk of criminal activity or the misguided actions of individual organisations.

2.6.0.2 This section looks at what should happen when things do go wrong.

2.6.0.3 For example, an identity or attribute service provider could provide inaccurate data due to issues in how the provider has captured a person’s data or linked (bound) it to that person. An attribute service provider may have breached the trust framework rules by not checking when the data was last updated before providing it. This inaccuracy may cause that person to be denied access to a relying service through no fault of their own.

2.6.0.4 Identity or attribute service providers could also fail to implement appropriate security measures, leading to a third party gaining unauthorised access to personal data. Such breaches could cause significant harm or distress to the people whose data has been exposed.

2.6.1 Complaints

2.6.1.1 As with all responsible service providers, trust framework organisations should have a clear route for individuals to make a complaint if things go wrong. The complaints process should respond swiftly and diligently to requests on areas such as data rectification. Indeed, there is already a statutory requirement to respond to a request for rectification within one calendar month under data protection legislation, with possible extensions if the request is complex or multiple requests have been received.

2.6.1.2 Where there is a scheme under the trust framework, it is expected the scheme owner should put in place their own complaints and resolution process to provide redress for individuals, either in addition to or instead of what is done at the level of individual organisations.

2.6.1.3 However, it is recognised that as the governing body is responsible for ensuring trust in the framework, there needs to be an option to escalate a complaint when it has not been satisfactorily resolved, or when the complaint involves multiple actors within the trust framework. To give both individuals and organisations transparency, there will need to be clear rules to define what qualifies as a complaint which can be escalated and what the possible outcomes will be if it is upheld. These details will be worked through once the policy to redress and enforcement have been finalised post-outcome of the consultation.

2.6.1.4 To reduce burden on the governing body, proof will likely be required that resolution has been sought through lower-level governance processes first. The governing body will also need to be able to gain access to the information it needs to investigate who is in the wrong when such complaints are made.

10.Do you agree the governing body should be an escalation point for complaints which cannot be resolved at organisational or scheme level?

2.6.1.5 If a complaint is upheld, the governing body will need to take appropriate action related to redress and enforcement, as detailed below.

2.6.2 Redress for individuals

2.6.2.1 Redress for individuals refers to the process by which individuals can seek compensation, through a claim, for a harm that has been inflicted upon them by one of the actors in the digital identity ecosystem.

2.6.2.2 When something goes wrong and a trust framework organisation is at fault, it is likely to be covered by the UK General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and Data Protection Act 2018 in the majority of circumstances. We therefore do not plan on creating any new offences relating to digital identity.

2.6.2.3 Outside of new offences, there is still a case for considering additional redress routes for consumers in a digital identity context - although given the close links to data protection, they would need to be cautiously implemented or risk creating confusion for consumers. At the moment, an individual can make a complaint to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) when they think their data has been misused. The ICO may take enforcement action but individuals will not receive any financial compensation without going through the courts. It should be noted that whichever regulator is selected as the governing body for digital identity, their complaints process will need to have a clear relationship to the ICO’s existing complaints process. This will be worked through once a regulator has been chosen.

2.6.2.4 We recognised that if something goes wrong with a digital identity, it has the potential to cause more harm than the misuse of data in other contexts. For example, it could prevent access to a critical service or block an important transaction. There is also the psychological impact of having identity-related data misused. An easier route to financial compensation could therefore be justified when a trust framework organisation has broken the rules and significant harm has been caused.

2.6.2.5 One option for implementing this is for organisations to be compelled to provide compensation to individuals under certain circumstances when responding to an escalated complaint. Depending on the existing set-up of the selected regulator, it could take the form of an ombudsman-like service provided in-house by the governing body, or through a relationship between the governing body and an independent ombudsman.

Example: Financial Ombudsman Service

The Financial Ombudsman Service is a free (for consumers) and easy-to-use service that settles complaints between consumers and businesses that provide financial services. They aim to resolve disputes fairly and impartially.

If a financial business and a customer can’t resolve a complaint themselves, they will give an unbiased answer about what has happened. If they decide someone has been treated unfairly, they will use legal powers to put things right.

All businesses that are covered by the service and are regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority pay an annual levy to contribute to their costs. Businesses may also have to pay an individual case fee when they handle a complaint about them.

2.6.2.6 An alternative is for industry to set up its own dispute resolution mechanism(s). This could take the form of optional but encouraged schemes for industry to set up on their own terms; an analogous example being the Removal Industry Ombudsman Scheme, which provides participating members with an independent dispute resolution service if their own procedures fail. A more interventionist approach could be to mandate trust framework organisations to join an industry-led scheme, with the governing body approving the terms of such schemes. An existing example of this is the requirement in the Housing Act 2004 for landlords and letting agents on assured shorthold tenancies to use a government-approved tenancy deposit scheme.

Example: ATOL protection

Air Travel Organiser’s Licence, more commonly known as ATOL, is a UK financial protection scheme covering most air package holidays. The scheme is run by the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).

The scheme exists to protect consumers if their travel organiser ceases trading, helping those already abroad minimise disruption to their holiday and providing compensation to those who have not yet travelled.

Travel businesses demonstrate they are covered by the ATOL scheme by displaying the ATOL logo on their website alongside their unique license number. The CAA also maintains a searchable list of ATOL holders — containing business name, website, and license number — so consumers can verify the authenticity of the logo.

Compensation is funded by the Air Travel Trust Fund, which in turn is funded by ATOL Protection Contributions. This is a charge of £2.50 per passenger, payable by ATOL holders, not passengers themselves.

2.6.2.7 A third approach would be for the trust framework to include contract terms for trust framework organisations to include in their terms and conditions (T&Cs) with consumers. These could be mandated T&Cs or, more flexibly, principles for contract terms. The latter could be supplemented with standard T&Cs to make it easier for organisations to implement, in a similar way to standard contractual clauses in data protection. Such T&Cs could include a commitment to pay compensation to consumers under certain defined scenarios, or a broader principles-based requirement to provide effective redress. This option could offer a quicker means to redress than a dispute resolution mechanism which will involve intermediary organisations.

2.6.2.8 Lastly, the governing body could reserve the right to impose one of these options at a later date when digital identity solutions become more advanced and used at scale. This would give us the opportunity to more fully assess the harm consumers may face in future and ensure the right course of action is taken. To ensure this is considered in good time, we could legislate for a full review to take place by a certain date.

2.6.2.9 Any additional redress routes need to be carefully considered. The trust framework will not be mandatory and relies on organisations recognising the value of joining. Too much risk and burden for organisations will result in reduced uptake and the redress routes won’t apply. Consumers will also fail to benefit from the security-centred requirements of the trust framework if organisations choose to not participate. Therefore intervention must meet a clear and well-defined need.

11.Do you think there needs to be additional redress routes for consumers using products under the trust framework?

If yes, which one or more of the following?:

- an ombudsman service

- industry-led dispute resolution mechanism (encouraged or mandated)

- set contract terms between organisations and consumers

- something else

If no, do you think the governing body should reserve the right to impose an additional route once the ecosystem is more fully developed?

2.6.2.10 We believe that, where there are redress pathways in existing regulators, the governing body should act to signpost organisations and individuals to these. This should be done using agreed mechanisms such as memorandums of understanding to ascertain where to signpost. This option would reduce costs for the governing body, lower regulatory burden on organisations, and avoid duplication of regulatory functions.

2.6.2.11 This approach has the advantage of alerting the relevant industry regulator that there has been an issue and may mean that there is not a need for a large resourced redress function within the digital identity governing body - although the governing body will need to triage cases and is likely to occasionally get involved in complex cases.

2.6.2.12 For example, under data protection legislation a person is able to enforce a failure by a data controller to comply with their obligations under data protection legislation by either bringing a complaint to the ICO or through bringing a claim against the controller directly.

12.Do you see any challenges to this approach of signposting to existing redress pathways?

2.6.3 Identity repair

2.6.3.1 Aside from financial compensation, the other key means for redress is ‘repairing’ identities quickly and effectively when there are errors. As above, individuals already have some rights under data protection legislation, which includes the right for individuals to have their personal data rectified, or completed if incomplete. Organisations must respond within one calendar month to these requests from individuals.

2.6.3.2 Under the trust framework, consumers could find this wait time is too long if the error is preventing service access. Where data is held in multiple sources, it may also become difficult for consumers to unpick where an error has occurred and who to contact to get it rectified. We are therefore considering what system-wide options we have for making it easier for individuals and organisations to maintain data accuracy. This could include rules and guidance in the trust framework, or governance processes between trust framework organisations. The options are likely to be separate to the complaints procedure described above, as they would offer a quicker route to redress for individuals without the need for escalation.

2.6.3.3 For example, a ‘no wrong door’ policy could mean that organisations could be required to assist consumers in finding where their data contains errors, rather than leaving it to the consumer to contact multiple organisations.

13.How should we enhance the ‘right to rectification’ for trust framework products and services?

2.6.4 Enforcement

2.6.4.1 Following monitoring and oversight, if the governing body finds that members or schemes are not complying with the rules of the trust framework then it will need to take punitive action.

2.6.4.2 At a minimum, the governing body should be able to expel or suspend non-compliant members from the trust framework and remove the trust mark from them. This may prevent organisations from making future checks against government-held data until they have been re-certified against the trust framework. The organisation who has had the trust mark removed will also be compelled to inform customers and clients of this fact. There may also be requirements to delete all data held which was collected during the infringement period/all data ever collected, or offer to transfer a customer’s data to a new provider, depending on the nature and severity of the case and the customer’s wishes. Other trust framework participants will also be informed of enforcement measures taken.

Regulating data protection

The Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018) sets out the data protection framework in the United Kingdom. The act sets out the enforcement tools that the Information Commissioner’s Office can use to regulate organisations processing personal data.

The DPA 2018 gives the ICO powers to issue:

- Information notices (section 142), which are issued to require an organisation to provide information to the ICO to assist with investigations.

- Assessment notices (section146), which are issued when the ICO wishes to use additional measures to carry out its responsibilities examples include entering premises to observe processing or interview staff

- Enforcement notices (section 149), which are issued when the ICO is satisfied that an organisation has failed to meet its compliance obligations.

- Penalty notices (section 155), which set out additional penalties including fines for serious breaches of data protection rules.

Organisations who wish to appeal the issuing of a notice can do so to the first-tier tribunal.

2.6.4.3 We recognise that these powers need to be proportionate to the level of end-user risk entailed. If the potential punishment facing companies is too great then it may disincentive companies who are interested in being involved in the digital identity market. An additional mechanism that may strike an appropriate balance would be escalation to other regulators, such as the ICO, the FCA and Ofcom. This could be established via memorandums of understanding between regulators as necessary.

14.Should the governing body be granted any of the following additional enforcement powers where there is non-compliance to trust framework requirements?

- Monetary fines

- Enforced compensation payments to affected consumers

- Restricting processing and/or provision of digital identity services

- Issue reprimand notices for minor offences with persistent reprimands requiring further investigation

15.Should the governing body publish all enforcement action undertaken for transparency and consumer awareness?

2.7 Security & Fraud

2.7.0.1 A strong and successful digital identity ecosystem offers opportunities to mitigate against many types of cybercrime and fraud. For example, if a person does not need to carry a passport to prove their identity then the opportunities for the document to be lost or stolen are reduced. To minimise digital risks, it is essential that the governing body should hold accountability for ensuring a robust approach to managing security and fraud. Part of its responsibilities will include ownership of the trust framework, which reflects the current best practice for managing all aspects of risks and security including cyber security and fraud.

2.7.0.2 However, just as digital identity and attribute use can be a tool for increasing security and minimising identity misuse, it will also inevitably be a target for those with nefarious intentions and therefore it is essential that the governing body takes proactive action to limit these activities, over and above detailing requirements and standards to prevent fraud and crime within the trust framework.

2.7.1 Information sharing

2.7.1.1 We envisage that the governing body hold accountability for implementing information sharing structures with and between trust framework participants and key stakeholders to maximise security and minimise fraud. The aim is to enable the detection and prevention of fraud and security incidents.

2.7.1.2 The work needed to set up effective information sharing structures for this purpose is significant, but we propose it is essential to developing and maintaining trust in the ecosystem. Some information sharing initiatives are already in existence, such as the National Cyber Security Centre’s Cyber Security Information Sharing Partnership, and where appropriate we will look to use these or learn from them. We recognise that while the governing body may be accountable for ensuring such structures are in place, it will likely be more appropriate to delegate responsibility for the operational requirements to another organisation/s.

2.7.1.3 In addition to the information sharing structures with and between trust framework participants, the governing body will engage and collaborate with relevant bodies across law enforcement, security, government, and industry organisations to stay up to date with threats and inform trust framework participants as appropriate.

2.7.1.4 We believe this approach will allow the governing body to:

- be responsible for ensuring fraud, security, and information assurance best practice among trust framework members, in addition to the requirements it mandates through the trust framework

- facilitate the sharing of fraud, threat, and risk information that could potentially impact members of the trust framework

16.What framework-level fraud and security management initiatives should be put in place?

2.8 Inclusion

2.8.0.1 Inclusion is at the heart of our policy making for digital identity. Not everyone will have a digital identity. This could be from personal choice. Or from digital exclusion, for example through lack of confidence and digital skills, or not having compatible devices (e.g. smartphone). Digital identity use will not be mandatory and people will retain the option to use available paper documentation.

2.8.0.2 Digital identity products will help empower people who may currently find it difficult to prove something about themselves. For example, if someone can’t afford traditional identity documents, they may benefit from being able to choose to use a digital identity product based on other data or on a ‘vouch’ (a declaration from someone that knows the user), as set out in the trust framework.

2.8.0.3 Multiple user research projects along with extensive conversations with subject matter experts across government and industry have indicated that an in-person option for digital identity creation will encourage a more inclusive digital identity market.

Example: In-person digital identity service

The Post Office is expanding its digital identity services. It will allow people to easily create digital identities face-to-face with a postmaster. This is an example of how a person with limited digital skills or lack of digital infrastructure will be able to set up a digital identity, to help them access services more smoothly.

17.How else can we encourage more inclusive digital identities?

2.8.1 Exclusion report

2.8.1.1 We want the governing body to help encourage organisations to be as inclusive as possible. When live, the trust framework will also have requirements which will encourage organisations to develop inclusive services. All organisations and schemes will be required to produce an annual exclusion report as part of being certified against the trust framework.

2.8.1.2 We recognise that there are many scenarios and situations where despite the best effort, exclusion is unavoidable. For example, an organisation which only focuses on scanning passport chips excludes those without a passport, but this exclusion is justified as being integral to the organisation’s product. If an organisation is unable to justify why they are excluding certain users, they must outline what they are doing to mitigate this.

2.8.1.3 Exclusion is easier to measure than inclusion and can describe how and what is excluded and why. It is possible to determine from a service why something shouldn’t have been excluded.

2.8.1.4 The exclusion report could include:

- Evidence of demographic research or customer analysis, including specific figures (but no personal data)

- Which demographics have been, or are likely to be, excluded from using the organisation’s product or service and an explanation of why this has happened or could happen

- The option to show extra steps an organisation is taking to improve inclusion and evidence to support this

2.8.1.5 An exclusion report is not intended as something that has a negative impact on the view of a service, nor is it intended to create overhead for a participant to produce. In the main, we would expect that the information provided is something that is readily available from a participating service’s internal metrics or key performance indicators (KPIs).

2.8.1.6 There are positive benefits in collecting this information:

- It will help the trust framework to improve inclusion over time

- It will help us identify if different technologies need to be considered to remove barriers to inclusion

- It helps us to decide if we are asking for the wrong evidence from individuals in a way which creates barriers to inclusion

- It helps us improve the overall digital identity landscape by recognising barriers and finding ways to break these down

- It gives us a way to have some measurement about what areas exclude potential users of a service

- It may help us decide if we need to change the list of people who can vouch for an individual

2.8.1.7 The governing body will extract data from these reports and share the findings with government where appropriate. It will also make recommendations for the improvement of inclusion under the trust framework, working together with scheme owners. It will identify any failure to meet this requirement. Such failures could result in enforcement measures taking place, as described above.

18.What are the advantages and disadvantages with this exclusion report approach?

19.What would you expect the exclusion report to include?

3 Enabling a legal gateway between public and private sector organisations for data checking

3.0.0.1 Proving entitlement or service eligibility via paper checks does not transfer neatly into the digital space. Digital identity and attribute products often require digital checks to be performed for them to realise their full potential. They can streamline and speed up processes and help with remote verification.

3.0.0.2 Digital checks enhance people’s privacy. Instead of showing an organisation a physical document containing a range of personal information, a digital check allows a person to only disclose what data is strictly necessary to allow access to a given service.

3.0.0.3 For example, instead of sharing household income, a person can share if their household income meets the threshold. Instead of sharing their personal address, a person could share that they live in a certain catchment area.

3.0.0.4 Government-held data is seen as authoritative and so checks made against it often hold more weight than that from other sources. There are a wide range of data sets held by the government, and checks against these could enable digital identity products to be built on a more inclusive footing.

3.0.0.5 We propose creating a legal gateway that will create a power for government departments and agencies to confirm personal data with organisations for eligibility, identity or validation checking purposes.

3.0.0.6 This power would not place a requirement on government data holders to allow checks against the data they hold. It would instead provide them with the power to do so, if they see fit.

3.1 Protecting privacy and individuals

3.1.0.1 UK data protection rules will provide individuals with protection when identity attributes are checked. Both parties, government and the organisation making checks, will need to have a suitable lawful basis for doing so.

3.1.0.2 Additionally, only trusted organisations should be able to request such checks against government-held data. There needs to be clear governance around any new legal gateway with industry or we risk damaging public trust. We propose that the trust framework and supporting certification and governance functions will provide a robust mechanism for delivering this trust, supported by contractual relationships with the government. This would also have the advantage of streamlining processes so that individual government departments do not have to complete their own checks on organisations to ensure they will handle data securely, alleviating the burden for government and organisations.

20.Should membership of the trust framework be a prerequisite for an organisation to make eligibility or identity checks against government-held data?

3.1.0.3 To further protect privacy, private sector organisations will not have direct access to government-held datasets and data minimisation practices will be part of any check. This means that the minimal level of personal information will be provided to complete the check. A way of doing this was demonstrated in the DCS pilot, as outlined in the introduction.

3.1.0.4 We intend for digital identity checks to simplify access to services by providing a quick and easy way to check a person is eligible. However, a service should not be denied solely on the outcome of a digital government check. That is, someone who is eligible for a service should not be denied access to it purely on the basis of a digital check against government-held data; there should be alternative methods for them to prove their eligibility, if required. These alternative methods may be similar to those employed today.

21.Should a requirement to allow an alternative pathway for those who fail a digital check be set out in legislation or by the governing body in standards?

3.2 How data could be checked

3.2.0.1 Our starting position is that attribute checks are best made via so-called ‘yes’/’no’ attribute checking. This is where an organisation requesting a check must assert a piece of information such as the data subject’s date of birth, then the government dataholder receiving the request responds ‘yes’ if the date of birth matches their record and ‘no’ if it does not. This matches the approach taken for the DCS pilot, as outlined in the introduction.

3.2.0.2 However, there may be cases where this would prevent appropriate checks being made and stifle innovation. For example, as part of a credit check it is easy to imagine a person asking HMRC to provide the tax band they have reached — something which the individual may be confused about if they have held several jobs within one tax year. This would not be covered by ‘yes’/’no’ attribute checking. Another example may be to allow ‘fuzzy matching’ for addresses, so if someone mistyped just one part of their address, the check could indicate a partial match.

3.2.0.3 If other styles of disclosure were allowed, such as those in the examples, we would still consider ‘yes’/’no’ attribute checking to be best practice to be used in the majority of cases.

22.Should disclosure be restricted to a “yes/no’’ answer or should we allow more detailed responses if appropriate?

Codes of Practice

Part 5 of the Digital Economy Act 2017 gives government powers to share personal information between Government Departments to improve public services. To ensure that data is shared correctly the Digital Economy Act 2017 established the rules for information sharing in Code of Practices which act as a practical guide for officials to follow before any information is shared.

3.2.0.4 A code of practice could reaffirm the obligations organisations must meet when checking information. A code of practice for digital identity is one way to ensure individuals are protected and organisations meet their privacy and transparency requirements. A code of practice for using government attributes could be set out in the trust framework or established in primary legislation.

23.Would a code of practice be helpful to ensure officials and organisations understand how to correctly check information?

3.2.0.5 We are considering allowing for the onward transfer of government-confirmed attributes. This would mean, for example, that if a person got their passport information digitally checked once, this positive check could be reused later without the need to reconfirm for a set period of time depending on the use case.

3.2.0.6 Of course, some data is time limited and some checks must be very time limited, such as right to work checks, and so may require a new check. We believe it should be for the data controllers to decide to what extent onward transfer should be allowed, and for bodies that produce guidance for use cases, such as the Joint Money Laundering Steering Group and the Disclosure and Barring Service,to determine what checks are appropriate in their sector.

24.What are the advantages or disadvantages of allowing the onward transfer of government-confirmed attributes, as set out?

4 Establishing the validity of digital identities and attributes

4.0.0.1 In the response to the Call for Evidence, we undertook to remove any unnecessary legal blockers to the use of digital identities and digital attributes. Just as we are committed to not making digital identities compulsory in the UK, we want to ensure that people are not forced to use traditional identity documents, if these are not strictly required, because of historic guidance which requires physical features, such as presentation of a holographic image.

The sale of alcohol (Licensing Act 2003) is a commonly cited blocker to digital identity use. The Home Office is currently running regulatory sandbox trials of age verification technology to find the most appropriate way forward in this area.

4.1 Opportunities to enable the use of digital identities

4.1.0.1 We believe that if digital identity products are overseen by a trusted governance system and built on the solid foundation of authoritative government-held data then then Departments whose business processes are predicated on identity verification (examples of which are discussed in the following paragraphs) will feel confident to update their guidance. We will of course work with those Departments to assist in this.

4.1.0.2 There are potential opportunities to enable the wider use of digital identities in the Disclosure & Barring Service (DBS) checks, which do not currently allow for digital checking methods, and within the Home Office Right to Work and Right to Rent Schemes, where their system of checks can be developed to enable the use of digital identities beyond their own internal services.

4.1.0.3 The Home Office has already implemented digital checks in the Right to Work and Right to Rent Schemes with the introduction of the Home Office online right to work and right to rent checking services. These services allow an individual to prove their right to work or rent digitally, by providing time limited access to the relevant information. This includes the individual’s name and facial image and can therefore be used for identity verification purposes. These services can be used by individuals who have been given access to a digital version of their UK immigration status (an eVisa), or those with a valid Biometric Residence Permit or Card.

4.1.0.4 The online services work on the basis of the individual first viewing their information which is to be shared. The individual can then share service specific information with the employer or landlord. The service is secure, free to use and enables checks to be carried out remotely via video call as the information is provided in real time directly from Home Office systems.

4.1.0.5 The Home Office is currently exploring options to allow digital right to work and rent checks for those who are not in scope to use the online checking services, for example British and Irish Nationals. However, the Home Office is clear any adopted technologies must adhere to the security and integrity requirements of the Schemes. The introduction of a governance and trust framework clearly presents opportunities in this area.

4.1.0.6 In the financial services sector we are working to ensure alignment with influential guidance such as that produced by the Joint Money Laundering Steering Group and the Financial Action Task Force, to increase organisation’s confidence in using digital identity verification methods.

4.2 Building confidence

4.2.0.1 As technology changes traditional non digital processes, there may be corporate aversion to embracing new technologies. Some organisations are still hesitant to use e-signatures, for example, despite a Law Commission report confirming that they are as legally binding as wet signatures in the majority of circumstances.

4.2.0.2 To avoid this issue, we are proposing that we introduce a statutory presumption affirming that digital identities and digital attributes can be as valid as physical forms of identification or traditional identity documents.

4.2.0.3 In addition we plan to make it clear in legislation that government-held data checked in digital form is equivalent to that currently provided in paper documentation, like passports. However, as set out in the previous section, we do not intend that a digital check should be the sole basis on which a service could be denied. That is, there should be alternative methods for someone to prove their identity. It should be noted that, for international travel, passports will still be required for the foreseeable future.

4.2.0.4 We believe that this measure, when combined with the other measures we are consulting on, will give guidance and regulatory bodies the confidence required to include digital identity solutions in their guidance, and give organisations more surety about their use of digital identities.

25.Would it be helpful to affirm in legislation that digital identities and digital attributes can be as valid as physical forms of identification, or traditional identity documents?

Summary of questions

Creating a digital identity governance framework

-

Do you agree an existing regulator is best placed to house digital identity governance, or should a new body be created?

-

Which regulator do you think should house digital identity governance?

-

What is your opinion on the governance functions we have identified as being required: is anything missed or not needed, in your view?

-

What is your opinion on the governing body owning the trust framework as outlined, and does the identity of the governing body affect your opinion?

-

Is there any other guidance that you propose could be incorporated into the trust framework?

-

How do we fairly represent the interests of civil society and public and private sectors when refreshing trust framework requirements?

-

Are there any other advisory groups that should be set up in addition to those suggested?

-

How should the government ensure that any fees do not become a barrier to entry for organisations while maintaining value for money for the taxpayer?

-

Do you agree with this two-layered approach to oversight where oversight is provided by the governing body and scheme owners?

-

Do you agree the governing body should be an escalation point for complaints which cannot be resolved at organisational or scheme level?

-

Do you think there needs to be additional redress routes for consumers using products under the trust framework?

If yes, which one or more of the following?:

a. an ombudsman service

b. industry-led dispute resolution mechanism (encouraged or mandated)

c. set contract terms between organisations and consumers

d. something else

If no, do you think the governing body should reserve the right to impose an additional route once the ecosystem is more fully developed?

12.Do you see any challenges to this approach of signposting to existing redress pathways?

13.How should we enhance the ‘right to rectification’ for trust framework products and services?

14.Should the governing body be granted any of the following additional enforcement powers where there is non-compliance to trust framework requirements?

a. Monetary fines

b. Enforced compensation payments to affected consumers

c. Restricting processing and/or provision of digital identity services

d. Issue reprimand notices for minor offences with persistent reprimands requiring further investigation

15.Should the governing body publish all enforcement action undertaken for transparency and consumer awareness?

16.What framework-level fraud and security management initiatives should be put in place?

17.How else can we encourage more inclusive digital identities?

18.What are the advantages and disadvantages with this exclusion report approach?

19.What would you expect the exclusion report to include?

Enabling a legal gateway between public and private sector organisations for data checking

20.Should membership of the trust framework be a prerequisite for an organisation to make eligibility or identity checks against government-held data?

21.Should a requirement to allow an alternative pathway for those who fail a digital check be set out in legislation or by the governing body in standards?

22.Should disclosure be restricted to a “yes/no’’ answer or should we allow more detailed responses if appropriate?

23.Would a code of practice be helpful to ensure officials and organisations understand how to correctly check information?

24.What are the advantages or disadvantages of allowing the onward transfer of government-confirmed attributes, as set out?

Establishing the validity of digital identities and attributes

25.Would it be helpful to affirm in legislation that digital identities and digital attributes can be as valid as physical forms of identification, or traditional identity documents?