Consultation on contingency arrangements for the award of GCSE, AS, A level, Project and AEA qualifications in 2022

Updated 11 November 2021

Introduction

Background and objectives

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted education throughout the previous two academic years. The government has been clear that it is committed to exams going ahead in summer 2022, but in light of the uncertainty around the continuing impact of the pandemic during the current academic year it is necessary to ensure that contingency plans are in place in case exams cannot take place safely or fairly. The Department for Education (DfE) and the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) therefore consulted on the approach that would be used to determine Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs) for GCSE, AS, A level, Project, and AEA qualifications if exams could not take place in summer 2022. The consultation aimed to collect the opinions of relevant stakeholders (e.g. students, teachers, exam boards, and so on), including on the guidance needed by centres to prepare for such a scenario and areas where improvements should be made to elements of the 2021 TAGs process.

Responses to the consultation will help inform the arrangements for the TAGs process should summer 2022 exams be cancelled. The consultation was available online for 14 days and received 664 responses. It gathered views on the following proposals:

- The type, volume, and timing of the production of the evidence that would be used to inform TAGs.

- The support that should be given by the exam boards to teachers determining TAGs.

- Contingency arrangements for private candidates.

- Quality assurance within schools and colleges (internal quality assurance) and undertaken by the exam boards (external quality assurance).

- The appeals process if a student believed something had gone wrong when their grade was determined.

- The potential impact of the proposals on persons who share protected characteristics (equalities impact assessment) and the potential impact of implementing the proposals in terms of additional costs and burdens (regulatory impact assessment).

Approach to analysis

The consultation was available to be completed through an online form from 30 September 2021 until 13 October 2021. The consultation included 30 questions covering the proposals for TAGs as a contingency in case summer 2022 exams had to be cancelled. The questions were:

- (i) quantitative, having a format of either a 5-point scale (meaning, Strongly agree, Agree, Neither agree nor disagree, Disagree, Strongly disagree) or two-option questions (Yes/No)

- (ii) qualitative, open-ended questions where respondents could provide comments on the proposals

Respondents were invited to self-identify the group to which they belonged. For the main analysis of the responses to the quantitative questions, we grouped the original unverified respondent types into six categories:

- Education or training providers (including academy chains, private training providers as well as schools and colleges).

- Exam boards or awarding organisations.

- Parents or carers.

- School and college staff (including exams officers or managers, senior leadership team members and teachers).

- Students (including private candidates).

- Other (including awarding organisation employees responding in a personal capacity, employers, consultants, local authorities, other representative or interest groups, governors, examiners, universities, Higher Education Institutions, or other respondents).

Six respondents self-identified as “Awarding body or exam board”. The four organisations recognised by Ofqual to offer GCSE, AS and A level qualifications are referred to as exam boards: AQA, WJEC, Pearson Edexcel and OCR. However, there are many more awarding bodies offering other qualifications.

Throughout the analyses presented in this report, the answers to quantitative questions are summarised in bar charts, presenting frequencies of responses broken down by respondent groups as listed above. The Appendix section includes analytical tables of the responses to the quantitative questions aggregated over all respondent types.

We read all responses to the qualitative questions in full. For these questions, we have presented the key themes that emerged from respondents’ answers. We have also included a selection of comments from respondents, some of which have been edited to correct spelling or grammatical errors and to keep respondents’ identities anonymous, though we have been careful to ensure any such changes do not alter the meaning of the comments.

Respondents could submit their final response without having replied to all questions. Many respondents skipped the qualitative questions or replied with “I don’t know” or “No comment”. These answers are included in the total number of responses presented in the document.

A small number of responses to the consultation were not submitted through the online form but summarised in a document submitted to Ofqual. Therefore, their responses are not captured in the quantitative questions, but they are reflected in the qualitative ones.

The report is organised into the following sections: (i) Evidence used to assess students’ performance; (ii) A national approach; (iii) Contingency arrangements for private candidates; (iv) Quality assurance; (v) Appeals; (vi) Equalities impact assessment; and (vii) Regulatory impact assessment.

The questions are presented in the same order as in the consultation document.

Profiles of respondents

In the following table, we present the number of respondents by respondent type.

| Respondent type | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Education or training provider | 59 |

| Awarding body or exam board | 6 |

| Parent or carer | 90 |

| School and college staff | 404 |

| Student | 59 |

| Other | 46 |

| Total number of respondents | 664 |

Over-arching themes

Several themes were suggested by respondents across multiple questions. To avoid duplicating analysis, these themes are summarised below.

First, a number of respondents emphasised the importance of clear and timely communication around the decision to implement contingency plans if exams were not able to take place. This included establishing the level of disruption required before implementing TAGs nationally as well as providing sufficient notice ahead of implementing contingency arrangements. For these respondents, clear communication would help reduce the workload and anxiety of teachers and students, especially the pressure from preparing for both exams and TAGs.

Second, many respondents suggested that exam boards should take a greater role in any TAG process that was implemented in 2022, compared to the 2021 arrangements. These respondents believed that exam fees should be proportional to the level of services provided, and that regular exam fees would not be justified if exams did not go ahead. To address this, respondents mentioned they would like exam boards to refund a greater level of fees than in 2021 if exams were cancelled or provide additional support through exam papers or question banks, moderation and/or marking, among other services.

Third, respondents stated that any TAG process in 2022 should follow the process from 2021 as closely as possible, as this would minimise potential confusion among teachers, students and parents and reduce the amount of time teachers and other staff would need to prepare during the year.

Finally, a small proportion of respondents called for exams to go ahead irrespective of underlying circumstances, as these respondents felt exams were the best way to assess student knowledge and it would be difficult to ensure the fairness and consistency of TAGs across the country. In addition, they believed that the time required for contingency planning would take away from teaching time that had already been disrupted by COVID-19. Some of these respondents suggested that additional health and safety measures could be put into place during exams to reduce the potential spread of COVID-19.

The evidence used to assess students’ performance

Questions covered in this section

This section of the consultation focuses on draft guidance proposed on how teachers should assess students to generate evidence to be used to determine TAGs if needed. The guidance aims to address concerns raised about the variable amounts and types of evidence on which 2021 TAGs were based, to enable teachers to collect evidence at points in the year that work best for them and their students, and to minimise burden.

Q1. How helpful do you think this guidance will be for teachers who will be making decisions on how to collect evidence to support TAGs as a contingency if exams are cancelled in 2022?

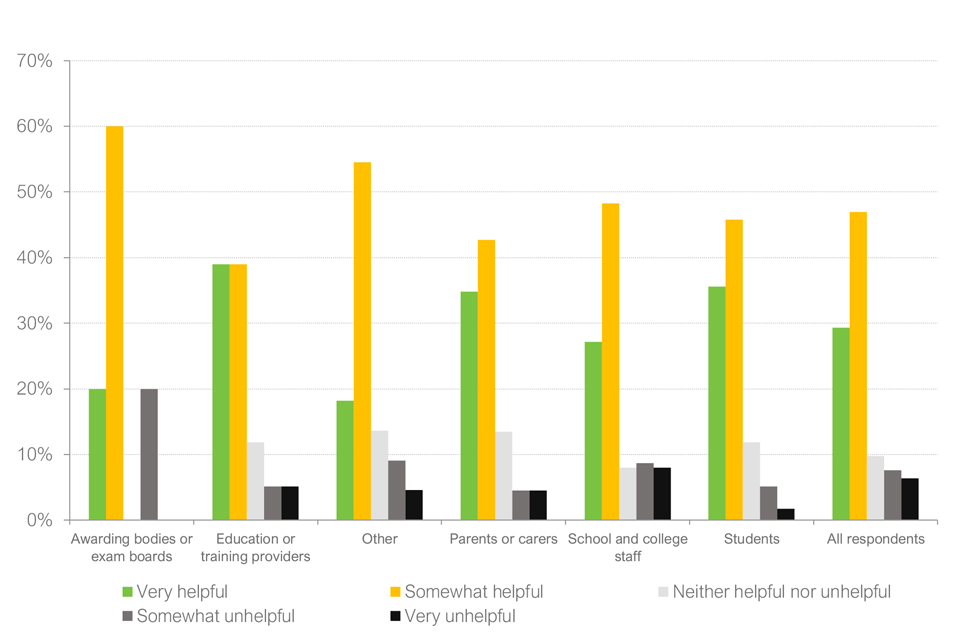

Bar chart showing responses to question 1.

Most respondents thought the guidance would be helpful for teachers, with 29% finding it very helpful and 47% finding it somewhat helpful across all respondent types. Ten per cent of respondents thought the guidance was neither helpful nor unhelpful, and 14% of respondents thought it would be somewhat or very unhelpful. Across respondent types, students had the highest proportion of respondents who thought the guidance would be somewhat or very helpful (81%), and 75% of school and college staff thought the guidance would be somewhat or very helpful.

Q2. Are there any parts of the guidance which you think could be improved?

There were 347 responses to this question. However, only 48% of respondents (167) provided an explicit answer to which parts of the guidance should be improved. Many of these respondents specifically mentioned two or more parts of the guidance. Among these respondents, the most cited parts of the guidance were sections B (67), C (39), G (38), and L (36).

A large number of respondents wanted clearer and more prescriptive guidelines for assessment arrangements. Respondents, in particular teachers, requested new assessment samples and grading parameters as well as guidance around the conditions in which assessments should take place and the quantity of evidence required.

While teachers are advised against over-assessment, a specific number of pieces of evidence could be advised. Otherwise, there is a tendency to collect as much evidence as possible in order to provide evidence for the best grades. (Teacher)

There must be clarity about what an acceptable level of control should be - e.g., if classroom level of control is acceptable, then groups within a cohort taking the same subject may sit assessments at different times, meaning certain students will go into the assessment not knowing the content, whereas classes who take the same assessment later will be aware (from talking to peers) of the content to expect. (Senior leadership team)

Students’ ability to perform at their best develops over time. It would be unfair to use data from the autumn term in preference to assessments given in the summer term. So surely it is fairer to students if we assess them at the end of the course. (Senior leadership team)

Some respondents expressed concern that the guidance would increase workloads for teachers, including the need for teachers to create, mark and moderate assessments and the potential difficulties assigning grades that accurately reflect students’ performances.

The implication of this is that there will be a massive spike in teacher workload, which is already very high. We are stretched enough as it is, without having up to three mock exam periods over the course of the year. We would struggle to create three new, secure papers which could be used. (Teacher)

The workload for staff is potentially huge. If additional assessment points are to be used, the exam boards should provide materials, mark, and moderate. The burden of setting papers, marking, and moderating papers, within school, is unworkable, given the fact that schools are operating normally with all other year groups (Education or training provider)

There was also concern around guidelines about communicating grades to students, as these respondents believed that it was important for students to be aware of their own understanding to better facilitate further learning.

According to the guidance, marks can be given to the students but not TAGs. What about mock exam grades? The students need these mock exam grades to inform their understanding of the level they are working at. More guidance about how we can communicate these to students without ‘telling them their TAG’ is necessary. (Teacher)

Some teachers asked for specific guidelines for subjects with a higher proportion of NEA (non-exam assessment).

In the case of music, it would be helpful to have guidance for performance in the case of illness or inability to access instruments due to COVID-19 restrictions. (Student)

Be specific about the extent to which NEA can be used to influence TAGs if this contingency is needed. Would it be the normal ratio (75:25)? What would happen if only the NEA could be completed? (Senior leadership team)

Finally, some respondents believed the guidance was not sufficiently clear for SEND students, private candidates, or students needing to isolate due to COVID-19.

A SEND pupil should not be at a disadvantage because their setting cannot provide their normal exam access arrangements through this academic year for example, cost of extra invigilators. Additional support must be in place for SEND pupils who currently stand to lose out compared to their peers based on the current guidance. (Parent or carer)

For private candidates, it needs to be clear on whether tutor/DLP evidence will be accepted. It also needs to include specific provision for whether remote assessments will be acceptable in an exam cancellation situation or not. Tailoring assessments is not feasible for private candidates who will be studying at different timescales and will have different content coverage to what is happening at a school. Centres will either not have enough experience of the specs to sensibly do this or will be too overwhelmed with all the different combinations for it to be a reasonable workload. (Parent or carer)

The idea that students would need to have work accessed by a teacher throughout the course would be unfair on students learning at home who would not have the same easy access to a teacher. (Student – private, home-educated of any age)

Q3. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the guidance set out above would reduce pressure on students, compared to the arrangements for TAGs in 2021?

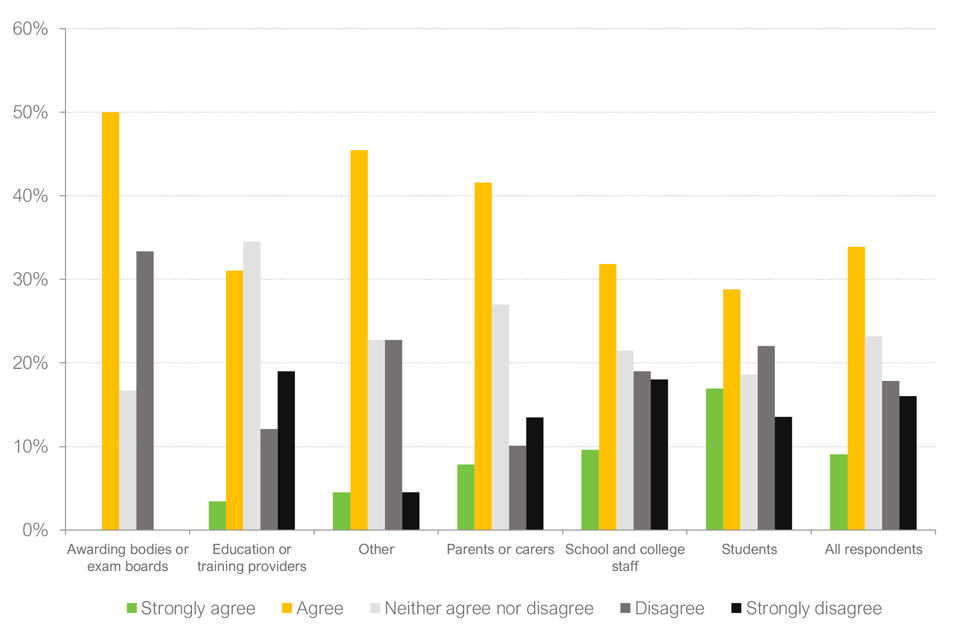

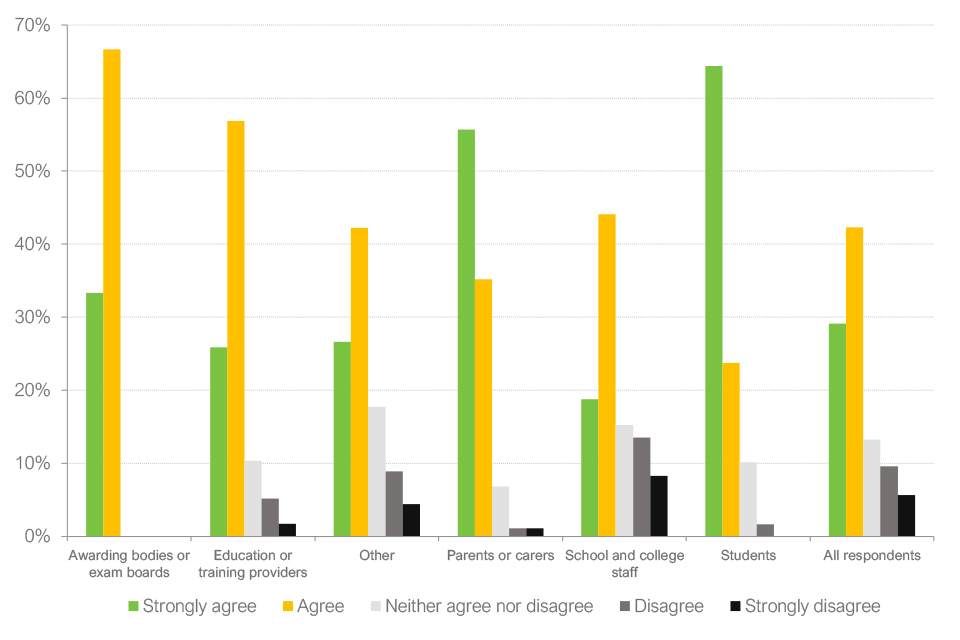

Bar chart showing responses to question 3.

Respondents were divided on whether the guidance would reduce pressure on students, with 43% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing and 34% disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Twenty-three per cent of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, other respondents had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (50%), followed by parents or carers (49%). School and college staff were the most likely to disagree or strongly disagree (37% of respondents). Nearly half of students agreed or strongly agreed with the proposal (46%), though 36% disagreed or strongly disagreed.

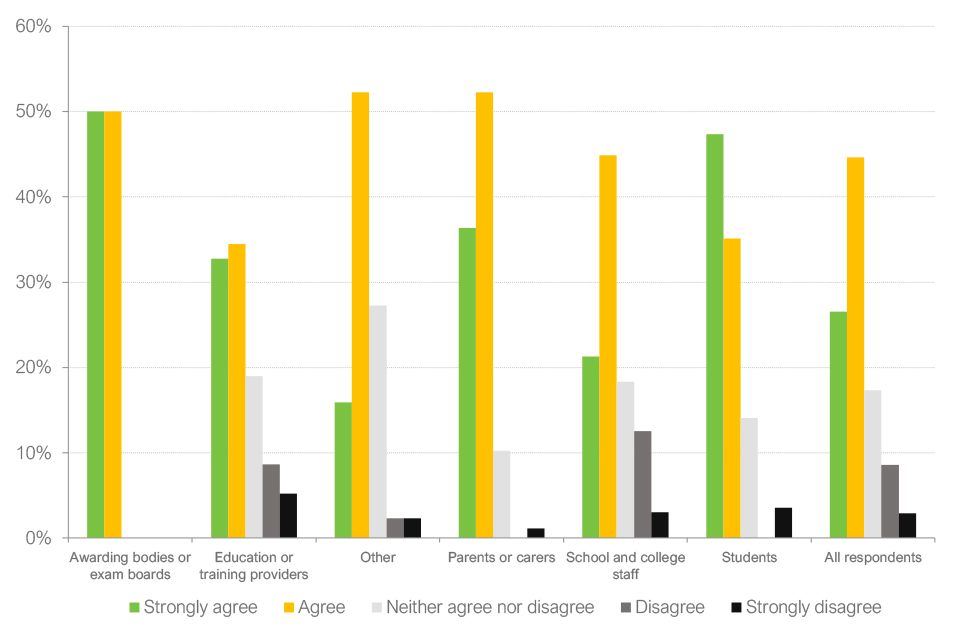

Q4. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the guidance set out above would reduce teacher workload, compared to the arrangements for TAGs in 2021?

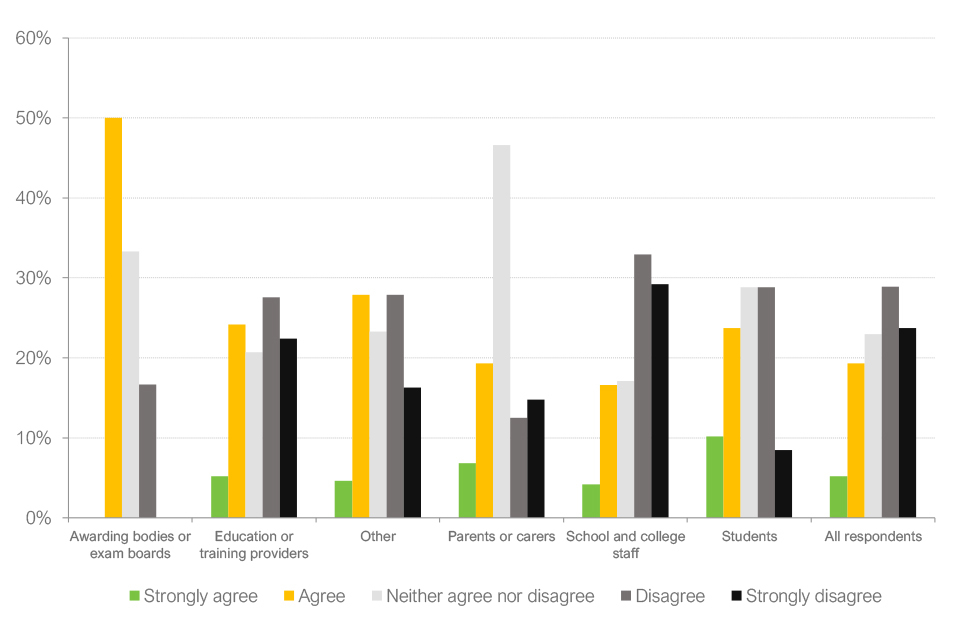

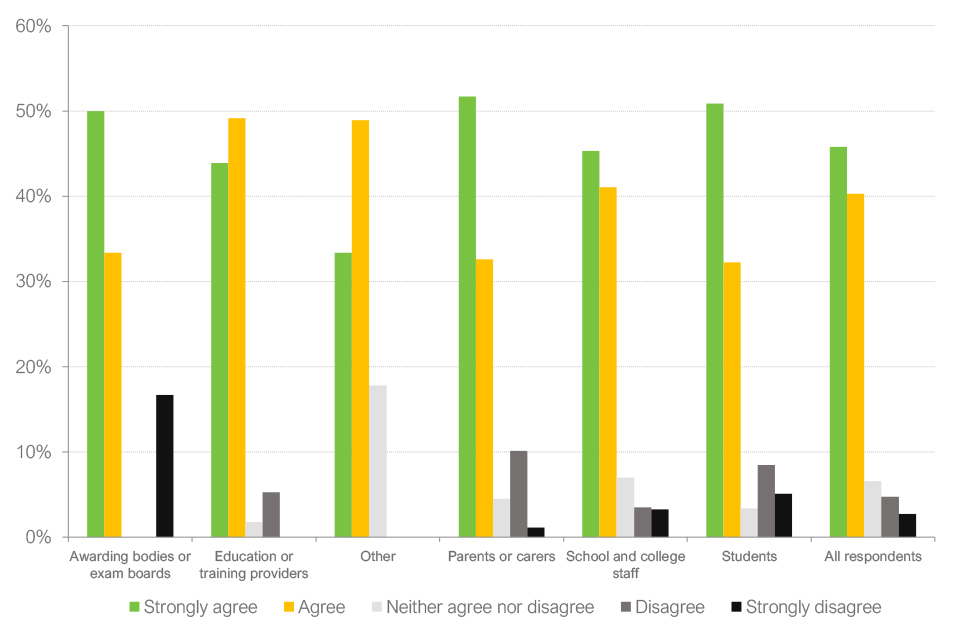

Bar chart showing responses to question 4.

A majority of respondents disagreed that the guidance would reduce teacher workload, with 53% of respondents disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Twenty-four per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed, and 23% of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, awarding bodies or exam boards had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (50%), followed by students (34%) and other respondents (33%). School and college staff were the most likely to disagree or strongly disagree (62% of respondents).

Q5. Do you have any comments on the support exam boards should provide to teachers determining TAGs should they be needed in 2022?

There were 345 responses to this question. The main theme was that exam boards should be heavily involved in 2022 if TAGs have to be used. Specifically, many respondents believed that exam boards should produce the assessments and mark them (or otherwise reimburse schools and colleges for services not provided).

Exam boards should be making provisions to set and mark exam papers - or should be paying teachers for the time they are putting into making and marking additional exam papers. (Teacher)

If TAGs are needed, exam boards should provide partial reimbursements of exam fees, to mitigate against the additional workload for teachers. (Teacher)

If exam boards are not responsible for marking, some respondents stated that exam boards should at least provide adequate guidance and exemplar material to facilitate the TAG process. This would help, in part, to mitigate the increased workload for both teachers and students that a TAG would involve.

It would be helpful if exam boards share assessment materials with guidance on how these should be used (and marked). (Senior leadership team)

Exam boards should provide exam papers with clear boundaries for giving grades. They should specify the content and provide formulae sheets and grade boundaries for schools to apply. If centres choose to adapt the papers or leave out difficult content, the board should give them options on how to adapt the grade boundaries. (Teacher)

Exam boards should provide exemplar materials of student work to see objective guidance with the mark scheme applied. (Teacher)

Exam boards should provide exam papers which can be used to assess throughout the year on a variety of topics to inform teacher judgements with mark schemes (Parent or carer)

In addition, respondents expressed the need for exam boards to provide new assessment material. According to these respondents, if teachers only had access to existing assessment material, they would not have sufficient material to provide TAGs. These respondents noted that as students could also access to past material, this would compromise the integrity of the assessments, creating inequalities with those that did not access the relevant material.

Exam papers should be provided to schools containing new questions. If past paper questions are used again, this would unfairly disadvantage students who had not seen those questions compared to those that had. (Teacher)

Provide a range of new (not recycled) papers/questions so that we can avoid the danger of pupils just learning mark schemes by rote or guessing what paper is going to come up because they have done all the other papers available for that unit. (Senior leadership team)

Some respondents also indicated a concern for consistency and fairness in marking assessments used to determine TAGs. To support this aim, these respondents suggested joint webinars or use of representative samples from multiple assessment periods.

Exam boards should provide webinars/training to support teachers and hopefully allow for more consistency across schools than I believe happened in 2021. (Parent or carer)

Exam boards should take a representative sample from each assessment period to moderate the quality of marking and grading. This will ensure that students achieving the same grade at different centres are performing to a similar standard. (Teacher)

A national programme of standardisation in each subject should be implemented to ensure judgements are valid - sampling in more subjects (pre- and post-exams) will also reduce errors in grading and judgement. (Senior leadership team)

Q6. To what extent do you agree or disagree that if exams are cancelled exam boards should not be required to continue moderation of NEA?

Bar chart showing responses to question 6.

Respondents were divided on not requiring exam boards to continue moderation of NEA if exams are cancelled, with 43% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing that exam boards should not be required to continue moderation of NEA and 36% disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Twenty-one per cent of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, students had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (57% of respondents). School and college staff were the most likely to disagree or strongly disagree (42% of respondents). Three exam boards recognised to offer GCSE, AS and A levels agreed or strongly agreed that exam boards should not be required to continue moderation of NEA, and one disagreed.

Q7. Do you have any other comments about the evidence which should be used to assess students’ performance?

There were 286 responses to this question. As with the previous question, many respondents requested new assessment material to help determine TAGs. In addition, some respondents called for the addition of a more formal assessment process, to make the process rigorous and fair.

Be more rigorous and prescriptive, i.e., all students should sit at least one unseen paper in exam conditions.(Senior leadership team)

More than 50% of assessments should be set in ‘high control’ and assessments set in ‘high control’ should have a higher weighting on the final mark. Schools should be able to provide three hours of formal assessment as evidence in their TAGs. (Senior leadership team)

Similarly, to maintain the rigour of assessments, some respondents said exam boards should take a greater role in moderating assessments or calibrating grades.

Exam boards should provide a service where anonymous TAG data from students can be reviewed, and a grade awarded by the exam board to allow calibration. (Senior leadership team)

Exam boards should carry out moderation of NEA remotely. Otherwise, there is an incentive not to complete the work, and this impacts student learning. (Exams officer or manager)

Boards should pay examiners to moderate TAG assessments to ensure standards are met uniformly. (Education or training provider)

On the other hand, some respondents suggested a flexible, continuous assessment scheme, combining results from assessments, class participation and completion of coursework. According to these respondents, a flexible scheme would provide a more accurate picture of student ability and help compensate for learning disruption caused by COVID-19. Respondents also emphasised the importance of maintaining teacher autonomy and taking into account differences between subjects.

In the absence of exams, the only realistic way to proceed would be to mirror the 2020 process and trust teachers to reach a ‘most likely outcome’ grade decision. It may look fairer to say grades are based on assessments, but in reality, the playing field is not level and it is a huge workload for schools as well as very stressful for students for no real advantage. (Senior leadership team)

I believe that students should be assessed on work from throughout the year to give a more representative idea of their overall academic ability and to take the pressure off a few examinations. (Student)

Centres should be allowed to make different decisions for different subjects depending on their characteristics and the characteristics of the final exams. Where there are topic-based subjects, assessments on different topics at the point at which they are taught make sense. For subjects where the exams are more synoptic and where the assessment objectives require combinations of topics, it is not reasonable to be forced to use assessments from earlier in the course. (Exams officer or manager)

Teachers should be trusted to make a professional judgement based on their knowledge of each student rather than subjecting students to numerous assessments and the teachers to an unmanageable avalanche of paperwork. (Teacher)

A national approach

Questions covered in this section

This section of the consultation focuses on the proposal considering the decision to cancel exams and apply contingency arrangements at a national level across England should it be necessary for 2022.

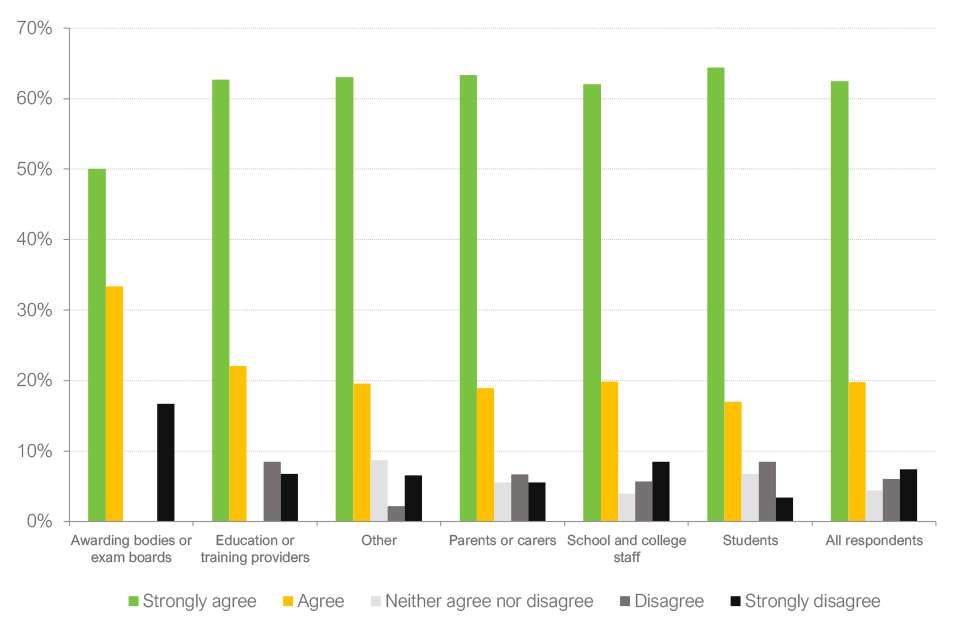

Q8. To what extent do you agree or disagree that if it proves necessary to cancel exams and implement TAGs in some parts of the country, exams should be cancelled for all students and the TAGs approach should be implemented nationally?

Bar chart showing responses to question 8.

Most respondents agreed that if it proves necessary to cancel exams and implement TAGs in some parts of the country, exams should be cancelled for all students and the TAGs approach should be implemented nationally, with 62% of respondents strongly agreeing and 21% agreeing across all respondent types. Thirteen per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 4% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, education or training providers had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (85% of respondents).

Q9. Do you have any other comments about the proposal for a national approach?

There were 291 responses to this question. Most respondents agreed with a national approach based on the principles of fairness and consistency, especially considering the importance of grades to students’ future opportunities in higher education and employment.

If there turns out to be a huge discrepancy of results across the country based on which areas implemented TAGs, it would put the exam boards in a very difficult position and students/parents would implement more complaints and challenges on results. (Teacher)

It has to be a national decision - you cannot have parts of the country using TAGs and other exams as this would be unfair to students (and later on to employers, etc). (Exams officer or manager)

It would create huge discrepancies were the approach not national. All students should be assessed in the same way and working by county/town rather than nationally could create huge comparative differences in the way in which students are assessed. (Teacher)

You cannot have a localised approach for a system that impacts children nationally for entrance into universities and colleges. (Parent or carer)

Most respondents who disagreed with the proposal did not specifically explain their reasoning. Instead, they expressed a preference for exams (with contingency arrangements for students who could not sit for exams) or an approach combining TAGs with exams. A small number of respondents suggested alternate solutions in which only students in certain regions of the UK would use TAGs.

Moderate TAGs from parts of the UK who do have to close for exams, once a benchmark is set by the national exams which are sat by other students in other ‘non-cancelled’ parts of the UK. (Teacher)

I understand the need for a contingency plan if schools have suffered a lot of disruption but separate provision for this scenario for those schools affected would hopefully ensure that the majority of schools sit exams and are therefore tested in the same way and those who are unable to do this have some special allowance - perhaps something along the lines of the usual special considerations given to students who are ill for exams. (Teacher)

There should be a threshold. For instance, an individual school suffering severe disruption (meaning exams could not be held) should not lead to the cancellation of exams across the country - it should be dealt with under special considerations, which may need extensions to allow for this. (Parent or carer)

Contingency arrangements for private candidates

Questions covered in this section

This section of the consultation focuses on the proposed guidance for contingency arrangements set out for private candidates, including 1) that private candidates should discuss arrangements to complete the required assessments with exam centres and take them into account when choosing the centre(s) at which they wish to register to take their exams, 2) DfE and Ofqual will work with centres and private candidates to support students to find opportunities to generate evidence required for a TAG, and 3) the same proposed guidance would apply to how private candidates were assessed, except that private candidates could undertake their assessments in a more concentrated period.

Q10. Do you have any comments on how arrangements from 2021 could be improved in order to better provide access to TAGs for private candidates?

There were 193 responses to this question. As with other questions, a number of issues raised have been covered under the section above on over-arching themes, including the need for early decisions and guidance both for centres and for private candidates. Other than these issues, the largest category of responses related to fairness, with concerns raised about potential unfairness both in favour of and against private candidates.

The proposals are likely to adversely impact private candidates (where provision of TAGs may prove impossible) – such candidates may disproportionately come from disadvantaged backgrounds. Experience over the last two years has shown it is difficult for private candidates to attain TAGs. (Other representative or interest group)

Evidence for private candidates for the last two years has not been rigorous or valid as teachers had no school-based exams/tests on which to determine a grade. The proposal for all private candidates to take internal exams at a school is the only way to ensure there is no bias or unfairness in the marking of these assessments. (Teacher)

The second largest category of responses related to the various difficulties for centres of providing TAGs to private candidates. This concern was frequently raised by exams officers or managers.

The extra work required for centres to ascertain the topics that had been studied, tailor specific assessments and then the additional marking involved is expecting too much. (Exams officer or manager)

While conducting assessments is fairly straightforward, the process of marking and awarding TAGs for private candidates in a short period after the assessments puts significant pressure on centre staff. (Exams officer or manager)

Focusing more specifically on the proposed arrangements, a number of responses noted approval of the proposals. The most frequently mentioned recommendation was that private candidates should register early with a centre rather than midway through an academic year.

Allow and publicise that private candidates would need to contact organisations like ourselves earlier in the year to allocate a tutor in order to start the assessment process, even if their education is taking place elsewhere.(Teacher)

Private candidates tend to apply to centres in late December / January. It is important not to expect schools and colleges to then provide numerous opportunities for these candidates to come in and sit assessments. (Exams officer or manager)

This is another good example of why it cannot work to ask schools/colleges to have three sets of assessment (e.g., November, January, April/May). By the time some private candidates have confirmed exam entries (normally February), they would have missed two of the key assessment sessions. (Senior leadership team)

A related suggestion (particularly from exams officers or managers) was that this could alternatively be a service provided by exam boards or specific centres designed to support private candidates.

As a centre that supported some private candidates to receive TAGs this summer, it was not a level playing field. The exam boards should be made responsible to set and mark assessments so all private candidates have access to the qualifications they have been studying for. (Exams officer or manager)

Private candidates could take extra exams (administered by exam boards) at different times in the year and let the exam board work out the final grades.” (School or college)

Centres which specialise in private candidates should be promoted. Arrangements should be made to allow private candidates to sit assessments, and centres should be permitted to set a schedule of assessments which private candidates must sit. (Exams officer or manager)

There should be a central body to offer this for private candidates. (Parent or carer)

There were mixed views regarding the proposal of private candidates having their assessments less spread out across the year. Some of this has been covered above under perceptions of fairness and the difficulty for centres to provide TAGs for private candidates with less time to assess their ability, both of which were associated with a preference for a larger spread of assessments across the year than the proposed period. There were also a number of responses noting the practical benefits of having the flexibility for assessments to be spread less over the year for private candidates.

Stakeholder feedback suggests that private candidates do not follow consistent patterns of study (with each other or with what might be considered standard practices in more typical educational settings). To enable broader access to TAGs for private candidates (than was facilitated in 2021), arrangements would need to afford greater flexibility in respect of assessment mode, frequency, and content. (Awarding body or exam board)

Private candidates are a diverse group and the contingency arrangements need to allow sufficient flexibility to enable as many private candidates as possible to obtain an appropriate grade in the event that exams are cancelled. For some private candidates, for example those who are home educated or have studied independently, the opportunity to sit assessments towards the end of their study within a more concentrated time frame may be an appropriate option. However, for other private candidates, such as those who have studied with a distance learning provider, it may be more appropriate for their grade to be based on assessments taken throughout the year. (Awarding body or exam board)

Quality assurance

Questions covered in this section

This section of the consultation focuses on the proposal that 1) schools and colleges should only develop centre policies for the awarding of TAGs if exams are cancelled, 2) exam boards should be proactive in engaging with schools and colleges to ensure they understand the 2022 TAG requirements, in the same way as they did in 2021, 3) schools and colleges should submit their policies to the exam boards for scrutiny, and 4) centres should keep original records of the work that might be used to contribute to TAGs and that centres should be ready to explain and/or review their TAGs when required to do so by an exam board. The precise way in which quality assurance of TAGs would operate, if necessary, in 2022 would be set out in detail only once any decision to cancel exams was taken.

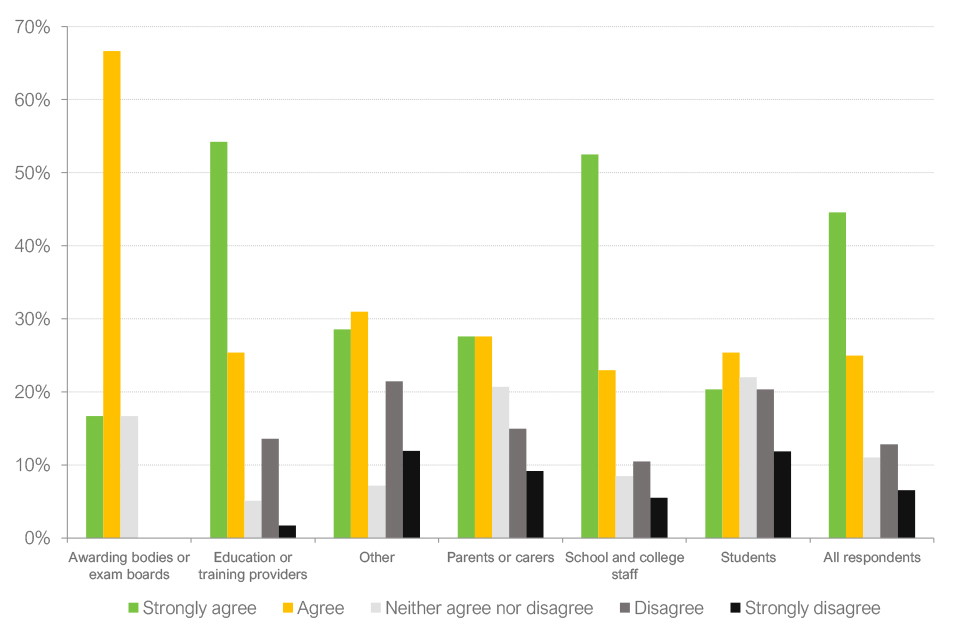

Q11. To what extent do you agree or disagree that schools and colleges should only be required to develop centre policies for determining TAGs if exams are cancelled in summer 2022?

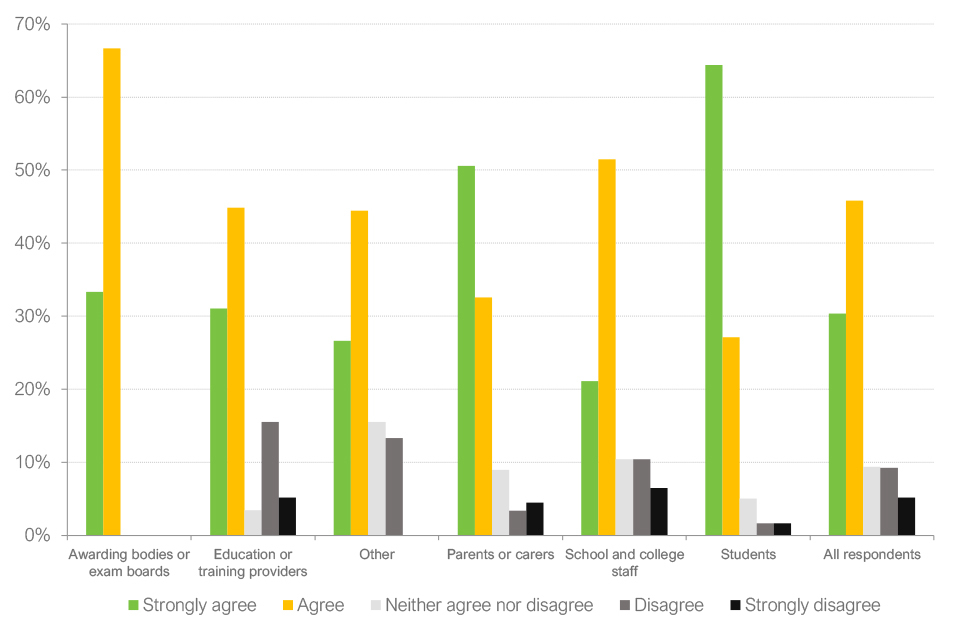

Bar chart showing responses to question 11.

Most respondents agreed that schools and colleges should only be required to develop centre policies for determining TAGs if exams are cancelled for summer 2022, with 45% of respondents strongly agreeing and 25% agreeing across all respondent types. Twenty per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 11% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, awarding bodies or exam boards had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (83% of respondents), followed by education or training providers (80%) and school and college staff (75%). Other respondents were most likely to disagree (33% of respondents), followed by students (32%).

Q12. Do you have any comments on how schools and colleges should quality assure TAGs in 2022 (should they be needed)?

There were 331 responses to this question. The most common theme suggested by respondents, in particular teachers, was that previous arrangements set out in 2021 should be followed to reduce burdens. Respondents agreed on the need for clear, prescriptive guidance set externally by exam boards as well as a strict moderation process within exam centres to uphold fairness.

I believe what we had in 2021 should continue for 2022 in order to minimise disruption and maximise teacher understanding of the processes. (Teacher)

Schools should be able to use previous arrangements unless substantive changes were required to outcomes at that centre. (Senior leadership team)

The guidance needs to be clear in terms of content and timelines well ahead of proposed exams. (Parent or carer)

An internal system of marking and moderating should be in place to ensure that schools are ready to submit accurate evidence for their candidates. (Teacher)

A similar approach to this year, with a clear internal policy and process, including, for example, multiple reviewers for TAGs, second marking, internal checks and so on would be effective. (Education or training provider)

Some respondents suggested a larger role for external review by exam boards to minimise the potential for bias in the quality assurance process, while other respondents expressed a preference for moderation at the local, regional or school-trust level.

There should be more external scrutiny based on the pattern of exam results over the last few years so if the results for an exam centre have, in relation to other centres and the national figure, massively differed then they should be scrutinised further in 2022. (Senior leadership team)

It is not possible to quality assure without bias unless an independent authority is involved, and the amount of work is massive. Exam boards must do external quality assurance. Schools should have to provide the question paper and the answer booklets to a moderator. (Exams officer or manager).

The internal assessments that students undertake should be moderated internally first, and then by at least one other school within the local authority. There should be an Ofqual-provided pro-forma for this process to ensure that schools are not inflating grades. (Academy chain)

Quality assurance should be carried out between local schools to moderate each other. (Teacher)

Q13. Do you have any comments on how the exam boards should quality assure TAGs in 2022 (should they be needed)?

There were 325 responses to this question. One common theme was the importance of wider sampling and increased moderation as part of exam boards’ quality assurance processes, with some respondents mentioning that exam boards should specifically examine schools with unusually high grades.

Wider sampling is required to ensure that centres are operating on a level playing field. As someone who was involved in the process this year, I saw significantly different approaches to the determination of TAGs. (Teacher)

There should be a greater degree of sampling and checking of marks. There should be a sampling of this information, especially from schools that have seen a significant rise in results since 2019. (Senior leadership team)

Moderate schools which have an abnormally high- or low-grade average in both subjects and in general. The abnormality should be calculated on the average of the previous 5 years’ grades awarded to students. (Student)

As discussed in the section on over-arching themes, a number of respondents expressed a desire for greater involvement by exam boards in the moderation and quality assurance process, while other respondents were satisfied with the previous year’s process and favoured consistency with 2021.

Finally, a small number of respondents suggested additional steps exam boards could take during the quality assurance process, including remote attendance at moderation meetings, unannounced moderation visits, marking by tutors from different centres, or keeping track of online teaching time.

Q14. Do you have any other comments about how TAGs should be quality assured in 2022 (should they be needed)?

There were 138 responses to this question, many of which did not directly address the quality assurance process. Respondents frequently emphasised the need for standardisation in procedures and practices as well as materials used for teacher training and assessment. Respondents suggested this would ensure fairness and comparability across the country and across different years, which was seen as especially important for private candidates.

There needs to be standardisation of processes and gradings. Not doing so fails all students. It particularly fails private candidates who are necessarily disadvantaged by a TAG process where knowledge of students by teachers comes into play. Marking of set questions however should be able to be done to an agreed standard. Adaptation can come when translating marks into grades; private candidate will at least know that the marking has been reliable if it is done by exam boards to agreed standards. (Parent or carer)

It is not possible to quality assure TAGs unless the evidence is standardised. (Teacher)

The key is providing a consistent standard of quality assurance and this can only come from the exam boards. (Senior leadership team)

As with the previous question, a number of respondents also indicated a concern around the potential for “grade inflation”, which these respondents believed should be addressed through more detailed reviews of centres exhibiting high grade variation.

If over/under marking is identified, centres should be required to re-review TAGs for the whole cohort. If this approach is developed and communicated in good time it should help ensure fair marking. (Parent or carer)

Appeals

Questions covered in this section

This section of the consultation focuses on the proposal that the 2021 arrangements for the appeals process should be carried forward without further changes if TAGs need to be implemented again in 2022. Based on this approach, a student would appeal to their school or college in the first instance, which would consider whether it made a procedural or administrative error. If the student remained concerned after this stage 1 appeal, their school or college would submit an appeal to the exam board on the student’s behalf. If an error was found, it would be corrected, adjusting the outcome of the teacher assessment up or down as necessary. In addition, the consultation proposed that provision should be made for appeals where a student’s higher education place depends on the outcome of the appeal to be prioritised by the exam board, and the final stage of the appeal process should be with Ofqual for consideration under the Examination Procedure Review Service (EPRS).

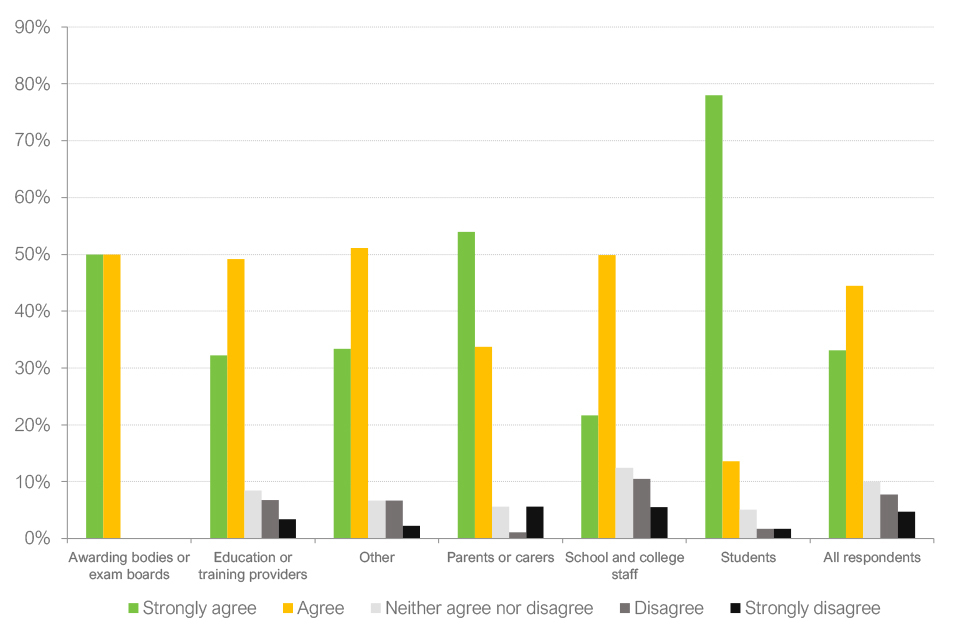

Q15. To what extent do you agree or disagree that students should be able to appeal if TAGs are used in 2022?

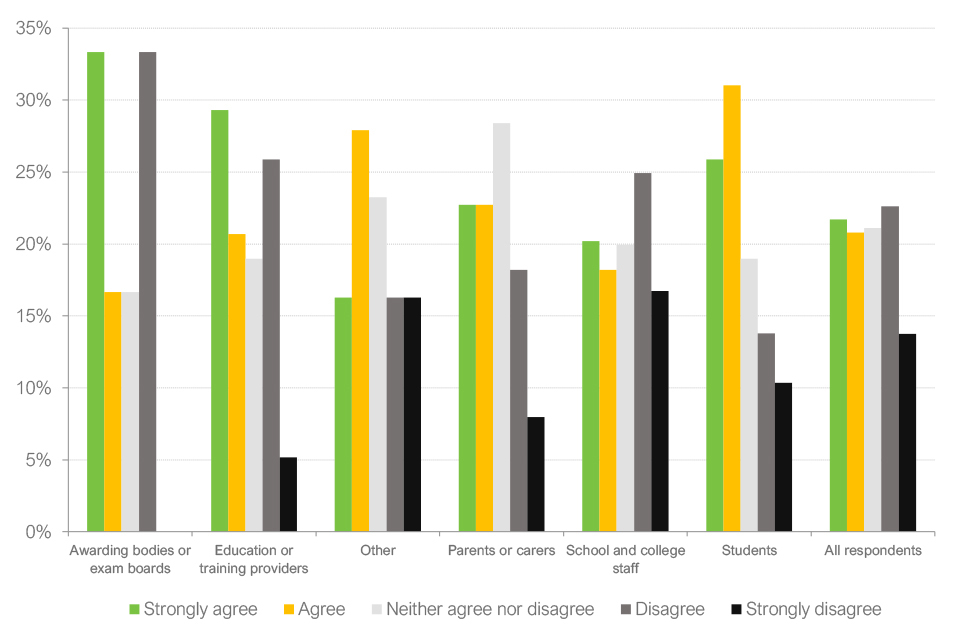

Bar chart showing responses to question 15.

Most respondents agreed that students should be able to appeal if TAGs are used in 2022, with 33% of respondents strongly agreeing and 44% agreeing across all respondent types. Twelve per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 10% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, students had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (92% of respondents), followed by parents or carers (88%). School and college staff were the most likely to disagree (16% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed).

Q16. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the grounds for appeal should cover: a) administrative and procedural errors, b) errors of academic judgement in determining the evidence used to determine a TAG?

Bar chart showing responses to question 16.

Most respondents agreed that the grounds for appeal should cover a) administrative and procedural errors, and b) errors of academic judgement in determining the evidence used to determine a TAG, with 32% of respondents strongly agreeing and 38% agreeing across all respondent types. Eighteen per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 12% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, students had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (92% of respondents), followed by parents or carers (91%). School and college staff were the most likely to disagree (25% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed).

Q17. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the grounds for appeal should cover: a) administrative and procedural errors, b) errors of academic judgement in the determination of the TAG itself?

Bar chart showing responses to question 17.

Most respondents agreed that the grounds for appeal should cover a) administrative and procedural errors, and b) errors of academic judgement in the determination of the TAG itself, with 29% of respondents strongly agreeing and 42% agreeing across all respondent types. 15% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 13% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, parents or carers were most likely to agree or strongly agree (91%), followed by students (88%). School and college staff were the most likely to disagree (22% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed).

Q18. To what extent do you agree or disagree that appeals should first be considered by the student’s school or college which would check for any administrative or procedural errors?

Bar chart showing responses to question 18.

Most respondents agreed that appeals should first be considered by the student’s school or college which would check for any administrative or procedural errors, with 46% of respondents strongly agreeing and 40% agreeing across all respondent types. Eight per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 7% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, education or training providers had the highest proportion of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing (93% of respondents), followed by school and college staff (86%). Students were most likely to disagree (14% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed).

Q19. To what extent do you agree or disagree that if a student remained concerned after an appeal to their school or college, the school or college would submit an appeal to the exam board on the student’s behalf?

Bar chart showing responses to question 19.

Most respondents agreed that if a student remained concerned after an appeal to their school or college, the school or college would submit an appeal to the exam board on the student’s behalf, with 30% of respondents strongly agreeing and 46% agreeing across all respondent types. Fourteen per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 9% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, students were most likely to agree or strongly agree (92% of respondents). Education or training providers were most likely to disagree (21% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed).

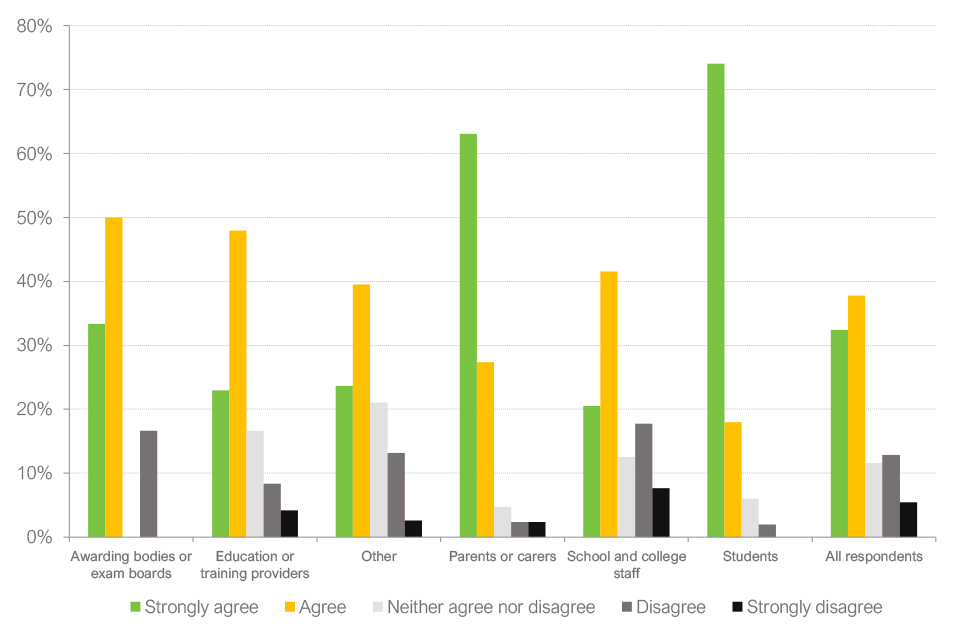

Q20. To what extent do you agree or disagree that a student’s result could go down as well as up following an appeal?

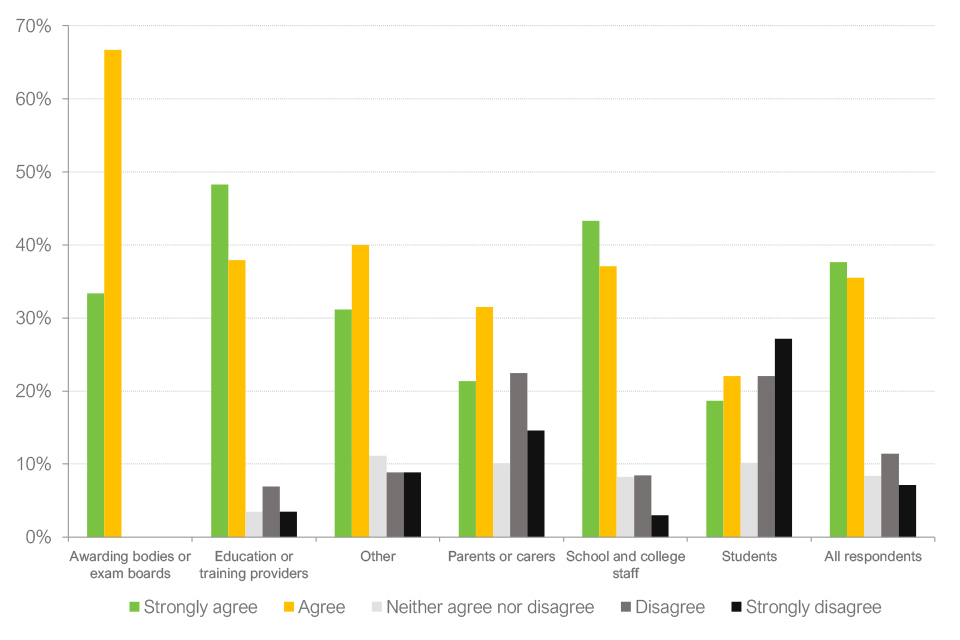

Bar chart showing responses to question 20.

Most respondents agreed that a student’s result could go down as well as up following an appeal, with 38% of respondents strongly agreeing and 36% agreeing across all respondent types. Eighteen per cent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 8% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, education or training providers were most likely to agree or strongly agree (86% of respondents). Students were most likely to disagree (49% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed), followed by parents or carers (37%).

Q21. To what extent do you agree or disagree that a student who had completed the appeal process could apply to Ofqual’s Examination Procedural Review Service which would check that the exam board had followed the correct procedure when issuing the grade and considering an appeal?

Bar chart showing responses to question 21.

Most respondents agreed that a student who had completed the appeal process could apply to Ofqual’s Examination Procedural Review Service, with 27% of respondents strongly agreeing and 45% agreeing across all respondent types. 12% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 17% neither agreed nor disagreed. Across respondent types, parents or carers were most likely to agree or strongly agree (89% of respondents). School and college staff were most likely to disagree (16% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed).

Q22. Do you have any other comments about appeal arrangements if TAGs are used in 2022?

There were 187 responses to this question. One common theme was the overall level of satisfaction with the appeals system used in 2021, and respondents noted the importance of students having the option to appeal to ensure transparency and fairness.

The appeals arrangements in 2021 seemed fair and fit for purpose - communication between departments, schools, and students (and their parents and carers) provided a strong reasoning and rationale for the decisions made. (Teacher)

It was really good that pupils knew they had the right to appeal and I think it felt they had a chance to have grades checked if they were not happy with the response from the centre. (Senior leadership team)

Some respondents suggested changes to the basis of appeal, in particular teachers’ academic judgement, as they thought this would reduce confidence in the system and in teachers’ abilities. These respondents believed that only appeals on administrative or procedural errors should be allowed.

If the government believes that ‘teacher assessment should be at the heart’ of the awarding process, it needs to protect the integrity of teacher assessment by sending a strong statement that questioning a teacher’s judgement, unless based on evidence of discrimination, will not be reasonable grounds for appeal. (Other respondent)

To allow appeals based on ‘academic judgement’ would undermine the whole process (and indeed teachers). (Teacher)

In addition, respondents agreed that the burden of reviewing appeals after stage 1 should be taken up by exam boards, as school and college staff had already shouldered a significant workload due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some respondents, in particular teachers, suggested that exam boards should be solely responsible for the appeals process as this would reduce strain on relationships between teachers and students and that exam boards would be better suited to ensuring consistency and fairness in appeals.

The impact of the protracted appeals process on schools, teaching and administrative and support staff in 2021 was staggering. This is a huge additional workload for schools and does not give them the buffer usually offered by exam boards. Whilst it seems appropriate that a school can check in the first instance for administrative errors, this should be the limit of the centre review stage. > (Senior leadership team)

If appeals are to be upheld at all, I think they should be conducted through the exam boards. I do not believe that a teacher needs the stress of seeing their professional judgement called into question. (Teacher)

The appeals process questions teachers’ professionalism and undermines the relationships teachers work hard to build up. Students should always have the right to appeal, but the appeal should be to the exam board and not the school or the teacher. (Teacher)

Respondents also believed that stricter requirements were needed for appeals to reduce the number of appeals not based on a valid reason (as they thought that students might choose to appeal because they had the option to do so, increasing the overall workload and slowing down the process for all students). Alternatively, respondents suggested that making an appeal could involve a fee that would be later returned to the applicant if the appeal was successful.

Students should have to provide all grounds for an appeal before appealing to the centre, even if the centre is not permitted to consider these grounds in the stage 1 appeal, and not change their grounds at a later stage if the initial grounds are rejected. If students have no grounds, centres should be permitted to reject the appeal. (Exams officer or manager)

The absence of a fee in 2021 led to a large number of speculative appeals, the vast majority of which were rejected by the exam boards at stage 2. Stage 2 appeals should not be free, although successful appeals ought to be refundable. (Senior leadership team)

Appealing exam grades in a ‘normal year’ has a financial cost to the complainant. This helps to ensure that appeals are based on legitimate concern and not just on a feeling of dissatisfaction with the outcome. There is no guarantee that with the intention to work to normalise future grade profile, schools will not be inundated with ‘free’ appeals in 2022. (Teacher)

Equalities impact assessment

Questions covered in this section

In developing the proposals included in the consultation, there was consideration of the impact that the proposals might have on students because of their protected characteristics. In this section of the consultation, respondents were asked whether the proposed contingency arrangements may lead to direct or indirect discrimination, and the extent to which they have the potential to advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations. Respondents were asked if they agreed with the impacts identified by DfE and Ofqual, whether there were other impacts not identified, and whether there were additional ways to mitigate these impacts.

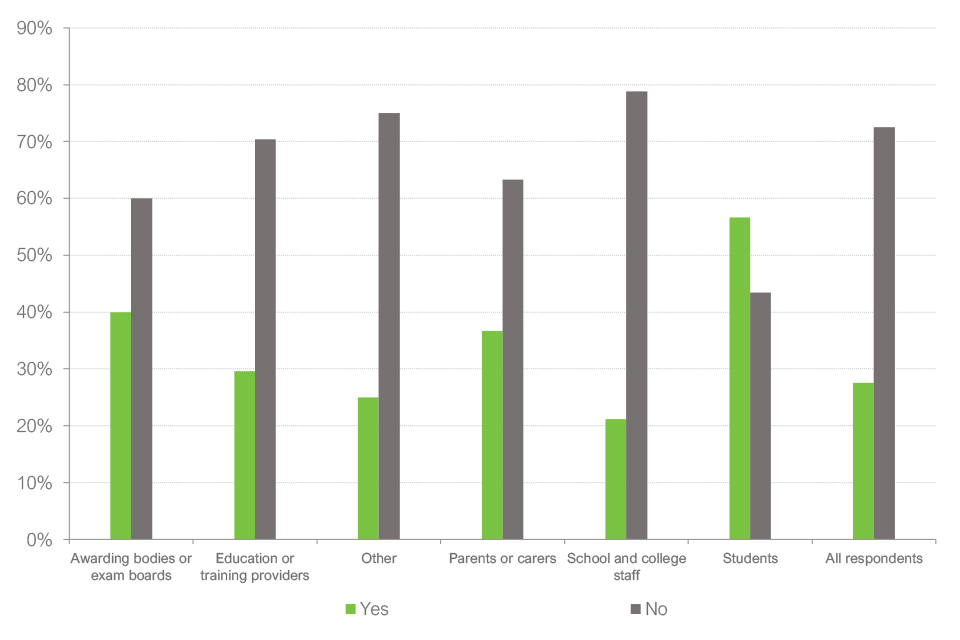

Q23. Do you believe the proposed arrangements (any or all) would have a positive impact on particular groups of students because of their protected characteristics?

Bar chart showing responses to question 23.

Most respondents disagreed that the proposed arrangements would have a positive impact on particular groups of students because of their protected characteristics, with 28% of respondents answering “yes” and 82% answering “no”. Across respondent types, students were the only respondent type for which more than half of respondents answered “yes” (57%). School and college staff were most likely to answer “no” (79% of respondents), followed by other respondents (75%).

Q24. If you have answered ‘yes’ please explain your reason for each proposed arrangement you have in mind.

There were 88 responses to this question, although only 61 respondents in this group answered “yes” to the previous question and few responses directly addressed the question. Some respondents mentioned negative impacts, which are discussed under question 26.

Several respondents mentioned that the 2021 TAGs system was fair and worked well to help close the gaps for students with protected characteristics.

A good system is blind to particular characteristics and has checks in it to ensure objectivity. The TAG 2021 system worked well in this regard. The principles that no single person could determine a TAG and that evidence of a QA system needed to be manifest were good. So too was the option for students to appeal. (Senior leadership team)

For each group there was a narrowing of performances gaps in 2021 suggesting that the TAGs policy with regards groups with protected characteristics was the correct on. (School or college)

Other respondents mentioned that spreading out the assessment period helped students who observed religious holidays, SEND learners, students who experience anxiety when taking formal exams, or other students disadvantaged by the normal examination schedule.

Exam time is a short period that sometimes coincides with religious festivals and so on that does disadvantage some students. TAGs would allow assessment over a longer period of time. It would also benefit students who get anxious around exam time and because it can be spaced out longer, centres will be able to provide further support. (Teacher)

For some students, NEA and TAGs would provide an opportunity to show attainment over a period of time as opposed to a particular day. The chaotic lives some students are forced to lead could seriously impact their result on any given (exam) day. This system would seem fairer to all. (Teacher)

I think spreading the grading across assessments over time would assist an autistic child like my son who may struggle to understand what he needs to do to organise himself with timings, understanding what material to cover, understanding how to cover it, and understanding how to ask for support. (Parent)

SEND learners are positively impacted, as the difficulties of time management, self-prompting and extended writing are often reduced in TAGs based on having shorter assessments. (Teacher)

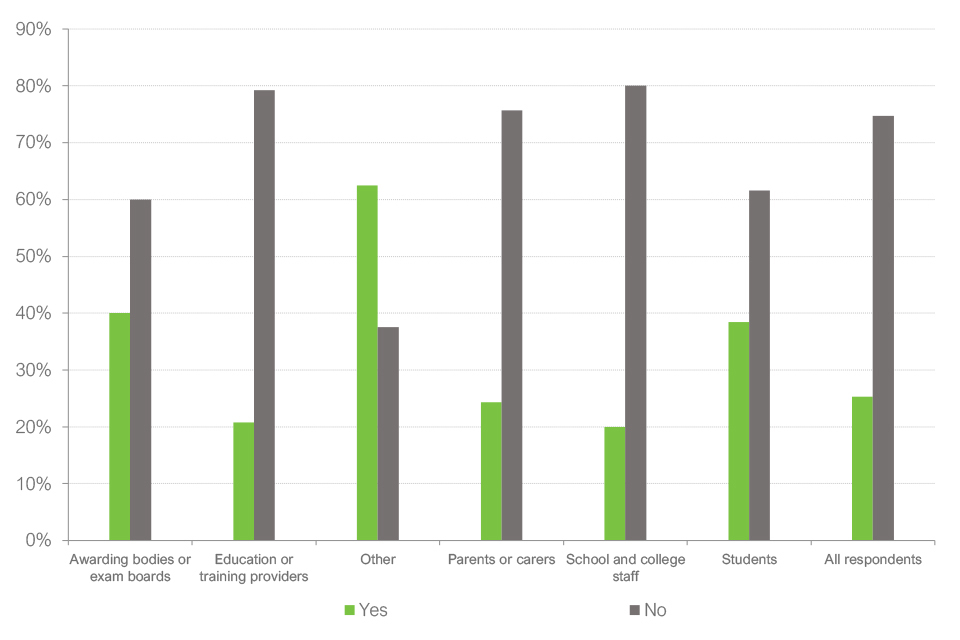

Q25. Do you believe the proposed arrangements (any or all) would have a negative impact on particular groups of students because of their protected characteristics?

Most respondents disagreed that the proposed arrangements would have a negative impact on particular groups of students because of their protected characteristics, with 25% of respondents answering “yes” and 75% answering “no”. Across respondent types, other respondents were the only respondent type for which more than half of respondents answered “yes” (63%). School and college staff were most likely to answer “no” (80% of respondents), followed by education or training providers (79%). Two exam boards recognised to offer GCSE, AS and A levels agreed or strongly agreed that the proposed arrangements would have a negative impact on particular groups of students because of their protected characteristics, one disagreed, and one did not answer the question.

Q26. If you have answered ‘yes’ please explain your reason and suggest how the negative impact could be removed or reduced for each proposed arrangement you have in mind.

Bar chart showing responses to question 25.

There were 115 responses to this question, though only 104 respondents in this group answered “yes” to the previous question and many respondents did not directly address the question or refer specifically to protected characteristics.

Some respondents noted that the transition from exams to TAGs might prove jarring for SEND learners, who may not have sufficient time to adjust depending on the timing of the announcement, and access arrangements for regular assessments might reinforce a sense of social isolation and being “different” from peers.

“SEND children may not like the changes from exams to ‘other exams’ and are not fully prepared for it in the way they are with exams.” (Parent or carer)

Other respondents raised potential concerns that students who had lost the most learning time due to COVID-19 pandemic disruptions, which respondents believed were disproportionately ethnic minority students, would continue to miss more time under the TAGs process.

We are particularly concerned about the effect of potential over-testing on disadvantaged students and those who have missed out on the most education over the course of the pandemic. These students, who are disproportionately ethnic minority and working class, but not exclusively, would particularly benefit from as much mainstream curriculum delivery time as possible this year such that they have the maximum level of content knowledge given the disruption to their education. (Other respondent)

Most respondents mentioned potential impacts on groups of students, but their comments did not relate directly to protected characteristics. For example, some respondents noted that students who experience anxiety or other mental health issues might find it more stressful if assessments are spread throughout the year instead of being contained to one exam season.

Students who experience anxiety/mental health issues will feel scrutinised for every assessment rather than just the exam season. This will lead to an increase in the number of students unable to function at school/non-attenders and burn out. (Teacher)

Those suffering from depression or have other educational needs find TAGs very stressful. They would find the usual exam process stressful - but that is usually over and done with quickly and doesn’t consume and feed anxiety over a protracted period. (Other respondent)

Respondents also mentioned that private candidates would be impacted due to increased difficulties finding exam centres willing to accommodate them. According to these respondents, the reduced number of available exam centres would lead to an increased financial burden due to travel expenses as well as higher stress levels around uncertainty of arrangements.

Private candidates would be negatively impacted because of their lack of pre-existing relationships with exam centres, and they would be assessed in a vacuum compared with students in schools and colleges. (Exams office or manager)

Private candidates with SEND will be negatively affected, primarily by the increased difficulty in finding exam centres that are able to accommodate these arrangements. This will lead to increased costs and stressful travel arrangements which may be so onerous as to mean private candidates with SEND simply do not access qualifications this year. (Parent or carer)

Very few respondents suggested how the negative impact could be removed or reduced. One potential solution raised was robust (and potentially blind) moderation of evidence to reduce unconscious bias.

A mitigation which could have a significant effect on reducing the impact of unconscious bias would be comprehensive blind moderation of grading evidence against the grades suggested. If Ofqual and DfE are serious about their duty to eliminate discrimination, then ensuring samples of grades from all centres in all subjects at the centre are blind-moderated against evidence of performance would be a huge step towards doing so. (Other representative body)

The most effective way to address unconscious bias would be to ensure that there is robust, external moderation of grades via the exam boards. This would also help to ease some of the pressure on teachers, while giving more confidence in the grades to employers and other further study destinations. (Other representative body)

Another proposed solution would be finding ways to connect private candidates with exam centres who are able to meet their needs, providing financial support to students as needed.

It is incumbent on all in the system to find mechanisms for supporting and encouraging centres to cater for the needs of such candidates. We would also recommend that the possibility of providing centres who agree to support private candidates are provided with modest financial support for doing so. (Awarding body or exam board)

Regulatory impact assessment

Questions covered in this section

This section of the consultation asked respondents if there were additional activities associated with delivering the proposed contingency arrangements that had not been identified in the consultation, if there were additional costs incurred by the proposed contingency arrangements and if there were alternative approaches to reduce burden and costs.

Q27. Are there additional burdens associated with the delivery of the proposed arrangements on which we are consulting that we have not identified above? If yes, what are they?

There were 270 responses to this question. Respondents mentioned a number of different burdens, with the predominant theme across all respondent types being increased workloads for teachers and other staff through the need to take on the responsibilities for creating, marking and moderating exams. Similarly, many teachers noted that it was difficult for centres to plan for both exams and TAGs, and the need to prepare for both placed additional pressure on teachers and other staff.

Teachers do not normally moderate internal assessments and mock examinations. Preparing for possible TAGs will generate increased workload in this regard. (Teacher)

The entire contingency process is an additional burden upon centres and staff. The process involves setting, marking and grading papers, deciding upon TAGs and uploading these, internal QA, associated administration, the retention and sorting of evidence and administration of results and appeals. This is an enormous extra burden upon school staff. (Senior leadership team)

Schools are currently operating two systems: One with the exams happening and one with TAGs. This uncertainty is placing a burden of work and responsibility upon staff and students. (Teacher)

Some respondents believed that delivery of the proposed arrangements would impact available teaching time due to the need for frequent assessments.

The proposed contingency has the potential to place enormous workload burdens on staff and to significantly reduce teaching time. This places assessment as more important than teaching; something that is fundamentally at odds with our core purpose. (Academy chain)

The main issue is time. Developing and applying a robust and thorough TAG process places a heavy burden on centres in terms of additional workload when teachers are busy trying to finish subject content. (Senior leadership team)

Teachers need time to mark all of this, therefore you will be cutting down on teaching time - like in 2021 - where the deadline was so soon in the term that we had to assess regularly over a long stretch of time. (Teacher)

Senior leadership team respondents also noted that there would be potentially significant logistical costs to retaining, storing, and disposing evidence for TAGs (due to the confidential nature of the documents).

The retention and disposal of evidence introduces considerable cost to the school as it is confidential waste and needs to be disposed as such. (Senior leadership team)

Workload associated with gathering physical evidence and storing this in files in preparation of the moderation process or appeals. (Senior leadership team)

Q28. What additional costs do you expect you would incur through implementing the proposed arrangements on which we are consulting?

There were 225 responses to this question. For respondents of all types, the most frequent cost cited was the impact on teacher and staff workload, with school and college staff mentioning in particular the financial costs of centres taking on the additional responsibilities of TAGs. These include costs of external invigilators, staffing costs to support different access arrangements and the appeals process, as well as cover for assessment moderation.

If required, cover for colleagues to attend moderation. (Academy chain)

More external invigilators to ensure TAGs are based on assessments that meet the government’s requirement that TAGs be of exam standard. (Teacher)

Possible increased staffing costs, particularly if there is an increased volume of assessments - such as supporting different access arrangements. (Senior leadership team)

Similarly, teachers and senior leadership team members raised the potential time costs of making contingency arrangements, with potential spill over effects on learning time for students. Respondents pointed out that teachers needed to carry out much of the TAG process (other than grading and appeals) before the decision to implement contingency plans would be announced if exams were not able to take place.

Huge ‘opportunity cost’ in terms of the time spent by staff on contingency arrangements which may have been spent on many other teaching and learning or development activities. (Senior leadership team)

Time - the burden placed on staff to complete this process again is hugely unfair on staff well-being, their family and friends. (Teacher)

The hard work (except grading) has to be done before we might know if it is necessary e.g. preparing suitably secure papers, high quality marking and moderation and the copying and storage of material. (Senior leadership team)

Teachers and senior leadership team members also mentioned the costs of printing and photocopying exam papers, although some respondents noted that these costs would be incurred even if exams were not cancelled.

Many extra photocopying costs putting pressure on budgets. (Teacher)

Photocopying costs will be part of both scenarios. These pale into insignificance when compared to the teacher time spent on preparing, marking and standardising TAG assessments. (Senior leadership team)

Several respondents, especially teachers, brought up the role of exam boards, including questioning the need to pay exam fees if exams were cancelled. These respondents proposed that exam boards offer discounts or refunds to compensate centres, as they did when exams were cancelled in 2020 and 2021.

One exam board stated that costs would depend on the timing of any decision to use TAGs, with greater preparation costs (such as technology and staffing) incurred the closer to exams the decision was made.

This would partly depend on when it is anticipated that any decision to use TAGs is made. If it does not happen until April, for example, we probably would have had to incur some technology costs and started some recruitment, just in case. So this would be a preparation cost that may not then be required. The closer you get to the exams before making a decision, the higher the preparation costs which may or may not then be required. (Awarding body or exam board)

Another exam board brought up the costs of supporting teachers throughout the TAG process, in addition to the costs of quality assurance, system development and a potential autumn exam series.

There will be costs associated with providing teachers with support in the implementation of strategies to collect evidence, the use of existing assessment materials, and the marking of these. Should the contingencies be required, we anticipate additional costs such as quality assuring centre approaches, policies, and the outcomes of their assessments (the scale of this will be related to the level of sampling required), potential additional costs in system development, and costs associated with a potential autumn series. (Awarding body or exam board)

An exam board also highlighted the sunk costs of producing assessment material that could no longer be used if the decision to move to TAGs took place after advance information was provided for summer 2022 exams.

Costs associated with the production of guidance for centres about contingency arrangements, along with preparation of systems and processes alongside preparing for a normal series in 2022. In addition, there would be costs in relation to the assessment materials for the summer 2022 series if the decision to move to a contingency TAG process was made after 7 February, when centres will have been provided with the advance information notices for the summer 2022 assessments. It would not be possible for exam boards to use those assessment materials for a future series, unless it was deemed suitable for the advance information to have been provided so far in advance of an autumn 2022 series, or the summer 2023 series. (Awarding body or exam board)

Q29. What costs would you save?

There were 170 responses to this question, with two common themes raised by respondents. First, a significant number of respondents, in particular senior leadership team members, said that they would potentially save on the costs of invigilation for summer exams, though some caveated that centres might need external invigilators to run high-quality internal assessments or would have to compensate invigilators even if they did not use them, to maintain a working relationship.

Some invigilation costs would be saved, although last year we ran our own internal assessments with invigilators to ensure fairness and high-control environments. (Senior leadership team)

Staffing is the main cost and this would not disappear. We would save a little on invigilators, although if the contingency is a late decision (after February) then we would feel obliged to pay our invigilators a proportion of their ‘lost’ income in order to retain their services. (Senior leadership team)

Second, respondents stated that exam boards should lower their fees if summer 2022 exams were cancelled, as they believed exam fees in normal years would not be proportionate to the services provided by exam boards if exams were cancelled.

If exams are not provided, schools should not be paying exam boards. (Teacher)

I would like to think exam boards would reduce their fees by a fair and reasonable amount should these circumstances arise this year. (Senior leadership team)

Exam boards should not be asking for exam fees as there would be no external marking of papers.” (Parent or carer)

Out of the four exam boards recognised to offer GCSE, AS and A levels, two set out several key costs that might be saved, including printing and logistics costs associated with exam distribution, staff costs for scanning exam papers, examiner marking fees, and possible re-use of content. They also acknowledged that savings would depend on the timing of the decision to cancel exams.

If exams do not go ahead, we anticipate that assessment materials developed for exams could be carried forward for a future year, but this may not be the case if advance information notices have already been published. Savings would depend on the timing of the implementation of any contingencies. Cost savings if exams do not go ahead depend on the timing of the implementation of contingencies but could include: the printing and the logistics costs associated with exam paper, examiner marking and moderator fees, and electronic scanning and cost of exam answer booklets. (Awarding body or exam board)

If exams are cancelled, the key costs where we would see savings are: print and distribution costs, temporary labour costs associated with scanning of exam papers/assessment process, content (possible re-use), and examiner marking fees. However, it should be noted, the extent of the saving will be determined by the timing of the exam cancellation and what costs have been incurred or committed at that point. (Awarding body or exam board)

One exam board acknowledged there would be cost savings but did not specify where the savings would occur, and another did not answer the question.

Q30. We would welcome your views on how we could reduce burden and costs while achieving the same aims.

There were 156 responses to this question. The majority of responses focused on the role of exam boards, in particular what level of service provided could be considered fair or justified if exams were cancelled. To address this issue of fairness, some suggested that exam boards should help mark exams and produce exam materials (such as question banks or mark schemes that teachers could draw on for their assessments).

It would be far more economical to fund the exam boards to produce new, optional assessment materials for use in the three suggested formal assessments over the year, than requiring centres to produce their own assessments themselves or from past papers. (Other respondent)

Exam boards producing assessment materials with mark schemes would be fairer and reduce the burden on teachers. (Teacher)

Centrally provided resources that are marked externally would be the most significant way to save costs. (Academy chain)

Exam boards should produce topic-focused papers with mark schemes and generate grade boundaries. (Teacher)

Other respondents suggested that exam boards should adjust their fees based on the level of responsibilities shouldered by centres.

Exam board fees need to be addressed in a situation where the burden of assessment falls to the teaching staff. (Senior leadership team)

Put pressure on the exam boards to provide the service for which they are paid. (Teacher)

Teachers, schools and colleges, and exam boards also emphasised it was important to confirm early on if summer 2022 exams would proceed or not. This would provide sufficient time for effective planning and help reduce unnecessary spending as well as teacher/student workload.

Earlier confirmation of the decision whether to run the exams or not is critical. The sooner a decision is reached, the more beneficial it will be from a cost saving perspective (e.g. reduced printing costs) and it will provide more time for the exam boards to create an efficient process to support delivery of the alternative arrangements. (Awarding body to exam board)

It is essential to inform schools early about whether exams will be cancelled or not. This is the only way to reduce burden on teacher workload. (Teacher)

Appendix

Table A1. Number of respondents by type

| Respondent type | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Academy chain | 16 |

| Awarding body or exam board | 6 |

| Consultant | 3 |

| Employer | 3 |

| Examiner | 2 |

| Exams officer or manager | 42 |

| Governor | 3 |

| Local Authority | 4 |

| Parent or carer | 90 |

| Private training provider | 3 |

| Senior Leadership Team | 126 |

| School or college | 37 |

| Student | 53 |

| Student (private, home-educated of any age) | 7 |

| Teacher (responding in a personal capacity) | 236 |

| University or higher education institution | 4 |

| Other | 16 |

| Other representative or interest group | 13 |

| Total number of respondents | 664 |

Breakdown of the responses for each question

How helpful do you think this guidance will be for teachers who will be making decisions on how to collect evidence to support TAGs as a contingency if exams are cancelled in 2022?

| Responses | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Very helpful | 193 | 29% |

| Somewhat helpful | 309 | 47% |

| Neither helpful nor unhelpful | 64 | 10% |

| Somewhat unhelpful | 50 | 8% |

| Very unhelpful | 42 | 6% |

| Total responses | 658 |

To what extent do you agree or disagree that the guidance set out above would reduce pressure on students, compared to the arrangements for TAGs in 2021?

| Responses | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 60 | 9% |

| Agree | 224 | 34% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 153 | 23% |

| Disagree | 118 | 18% |

| Strongly disagree | 106 | 16% |

| Total responses | 661 |