Tax gaps: Methodological annex

Updated 19 June 2025

Chapter A: Introduction

Methodology

A1. This document provides further details of the data and methodology used to produce estimates of the tax gap published in ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’.

A2. There are numerous methodological approaches to measuring tax gaps. The tax gap is the difference between the amount of tax that should, in theory, be paid to HMRC (‘theoretical tax liability’), and the amount that is actually paid.

A3. Top-down methods use external independent data sources to estimate total consumption of taxable products to calculate the total theoretical liabilities. An example of this is the VAT gap.

A4. Bottom-up methods include a number of techniques:

- random enquiry programmes — these involve undertaking compliance checks for a randomly selected sample of customers and scaling up the findings from the sampled cases to the relevant whole population.

- statistical methods — unlike random enquiry programmes these use risk-based compliance checks that are not representative of the whole population, and require statistical methods to scale up the results to the whole population

- population surveys — we use results from a bespoke research survey to estimate part of the hidden economy tax gap

- management information — these methods use management information such as:

- risk registers (a list of identified tax risks, together with information such as estimated value, nature and status)

- data extracted from accounting systems

- other databases or systems used to manage HMRC’s business

A5. The total tax gap is estimated using established statistical and illustrative methods. Illustrative methodologies, formerly called experimental methodologies, are used to produce estimates where there is no direct measurement data. For these tax gap components, we use the best available data and simple models to build an estimate of the tax gap.

A6. We employ the most appropriate methodology for each tax gap component, based on the factors listed below:

- availability of quality HMRC data

- availability of quality independent data

- structure of the tax regime

- cost and impact for both HMRC and taxpayers

- level of granularity required

A7. Generally, following good international practice, we use ‘top-down’ methodologies for indirect taxes and ‘bottom-up’ methodologies for direct taxes. The tax gap estimates may, however, also be produced by compiling the results from a combination of two or more methods.

Methods used to estimate the tax gap

A8. Table A.1 below shows the general methodological approach used to estimate each tax gap component.

Table A.1 Tax gap methodologies

| Top-down | Bottom-up (management information) | Bottom-up (statistical and survey) | Bottom-up (random enquiries) | Illustrative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol duties | Alcohol duties | PAYE mid-sized businesses | PAYE small businesses | PAYE large businesses |

| VAT all businesses | Hidden economy | Hidden economy | SA business and non-business | SA large partnerships |

| Tobacco duties | — | CT mid-sized businesses | CT small businesses | Stamp taxes |

| — | — | CT large businesses | Diesel duties | Other excise |

| — | — | Inheritance Tax | — | Other remaining taxes |

| — | — | Avoidance | — | — |

Notes for Table A.1

-

Alcohol duty gaps are produced using both top-down and bottom-up methodologies.

-

Hidden economy tax gaps for ghosts and moonlighters are produced using bottom-up management information and bottom-up statistical and survey methodologies.

A9. Figure A.1 below shows a summary of the tax gap by methodology. A degree of assumption and judgement has been applied to attribute some elements of the tax gap to methodology types, especially where a combination of methods is used.

Figure A.1 Tax gap by methodology (£ billion)

| Methodology | Total |

|---|---|

| Bottom-up (management information) | 1.7 |

| Bottom-up (random enquiries) | 23.0 |

| Bottom-up (statistical and survey) | 5.1 |

| Illustrative | 5.9 |

| Top-down | 11.0 |

A10. Over time, we have tried to estimate more of the tax gap using an established top-down or bottom-up methodology and rely less on illustrative methods. This is difficult to show on a comparable basis as the tax gap for earlier years is often revised between editions either when methodological improvements are made or the underlying data is updated — and the overall value of the gap changes over time.

A11. Table A.2 sets out the proportions of the total tax gap classed as established or illustrative in the last 6 editions of ‘Measuring tax gaps’. This shows 87% of the tax gap is estimated using established methods in ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’ compared to 76% in the 2019 edition.

A12. The proportion of the tax gap based on established methodologies has increased from 86% to 87% since ‘Measuring tax gaps 2024 edition’.

Table A.2 Share of total tax gap by established and illustrative methodologies in ‘Measuring tax gaps’ editions

| Measuring tax gaps edition | Illustrative methodology | Established methodology |

|---|---|---|

| MTG19 | 24% | 76% |

| MTG20 | 15% | 85% |

| MTG21 | 14% | 86% |

| MTG22 | 21% | 79% |

| MTG23 | 16% | 84% |

| MTG24 | 14% | 86% |

| MTG25 | 13% | 87% |

Tax gap development programme

A13. As official statistics, our tax gap estimates are produced with the highest levels of quality assurance and adhere to the Code of Practice for Statistics framework. This code assures objectivity and integrity — providing the framework to ensure that statistics are trustworthy, good quality, and valuable. It also provides producers of official statistics with the detailed practices they must commit to when producing and releasing official statistics.

A14. To ensure our statistics continue to be trustworthy, good quality and valuable we have a continuous development programme. As part of this we publish:

- a summary of the improvements to the estimates introduced in the current edition of ‘Measuring tax gaps’ publication

- a high-level summary of development priorities to improve the tax gap estimates in future editions of the ‘Measuring tax gaps’ publication.

A15. HMRC have a continuous programme of development to improve and strengthen our tax gap estimates. However, not all tax gap methodologies can be improved due to limited data availability and the balancing of costs to produce the data against the value they add to the estimates. HMRC has limited resource to produce statistics. We also have to maintain and assure the quality of existing estimates, including when there are changes to data sources.

A16. The following list provides a summary of methodological and data improvements introduced in ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’.

-

An improvement to the methodology used to estimate the non-payment tax gap for Corporation Tax, and Income Tax, NICs, and Capital Gains Tax in Self Assessment and PAYE, for tax years since 2018 to 2019. The new methodology is an estimate of eventual non-payment attributable to the year of tax debt creation. This aligns to the VAT non-payment methodology introduced in ‘Measuring tax gaps 2023 edition’.

-

A new established methodology to estimate the tax gap for avoidance in Income Tax, NICs, and Capital Gains Tax for tax years since 2014 to 2015.

-

An improvement to the methodology used to forecast compliance yield from open cases for the large businesses Corporation Tax gap estimate.

A17. ‘In Measuring tax gaps editions’ 2022 and 2023, HMRC announced that it would be publishing an estimate of the tax gap arising from non-compliance by UK residents failing to declare their offshore income where this had been identified through data received from other fiscal authorities through Automatic Exchange of Information. On 24 October 2024 HMRC published the first assessment of Undisclosed Foreign Income (UFI) in Self Assessment from UK residents in the tax year 2018 to 2019

Priorities ahead of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2026 edition’

A18. The following list provides a high-level summary of planned developments. Future dates are estimates and depend on resource availability. Priorities may change and not everything we try to develop will always succeed.

- Review the presentation of the information in the publication and consistency over time.

High-level summary of longer-term development priorities

-

Publish a stand-alone customs duty gap. HMRC continues to explore new approaches to develop a robust methodology as due to the inherent complexity of a customs tax gap multiple data elements need to be explored. Development of a customs duty gap is a priority for HMRC and it remains HMRC’s plan to publish a stand-alone customs duty gap in the future.

-

Assess the feasibility of extending the published estimate of the tax gap arising from undisclosed foreign income, including engaging with academics.

-

Improve the assessment of the tax gap arising from wealthy taxpayers.

Chapter B: Accuracy and reliability

B1. Our tax gap estimates are official statistics produced to the highest levels of quality and adhere to the UK Statistics Authority’s Code of Practice for Statistics framework. This framework ensures statistics are trustworthy, good quality, valuable and provides producers of official statistics with the detailed practices they must commit to when producing and releasing official statistics.

B2. A Measuring tax gaps quality report accompanies this statistical release, providing information about the quality of outputs as set out by the Code of Practice for Statistics.

B3. The figures presented in the ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’ are our best estimates based on the information available, but there are sources of uncertainty and potential error. For this reason, it is best to focus on the trend in the results rather than the absolute numbers when interpreting findings.

Accuracy

B4. Accuracy refers to the closeness of estimates to the true values they are intended to measure. Due to the methodologies used, uncertainty is an inherent aspect of all tax gap estimates. Uncertainty relates to a range of possible factors that can affect the accuracy of a statistic, including the impact of measurement or sampling error (related to sample surveys) and all other sources of bias and variance that exist in a data source.

Reliability

B5. Reliability refers to the closeness of estimated values with subsequent estimates. The methodologies used to estimate tax gaps are subject to regular review and can change from year to year due to improvements in methodologies and data updates. These can result in revisions to any of the previously published estimates. Estimates are made on a like-for-like basis each year to enable users to interpret trends. Where data sources change over time, every effort has been made to ensure consistency in the time series, but this is another potential source of uncertainty.

Uncertainty

B6. Statistical uncertainty is caused by two factors:

- sampling error — errors that arise because the estimates rely on information collected from a sample, rather than from the whole population; sampling error can lead to year-on-year fluctuations in the tax gap estimates that do not reflect true changes in the size of the tax gap

- bias or non-sampling error — systematic errors where the modelling assumptions or errors in the data lead to estimates that are consistently either too low or too high.

B7. Where possible, HMRC has estimated the likely impact of sampling errors by calculating statistical confidence intervals. These give margins of error within which we would expect the true value lies 95% of the time, if there were no systematic errors. They provide an indication of the extent to which changes in the estimates between years can be confidently interpreted as true changes. They do not take account of systematic errors that might lead the central estimate to be too low or too high over the whole series.

B8. Systematic error is less straightforward to deal with, as it is not defined by statistical assessments that allow for easy interpretation. In order to give an indication of the effect of these biases, HMRC presents the tax gaps for alcohol and tobacco as ranges. For beer and tobacco these are constructed as the range between upper and lower bounds, representing the degree of uncertainty associated with those systematic biases for which upper and lower bounds can be derived.

Tax gap uncertainty assessment

B9. To show the uncertainty of tax gap estimates in a systematic and transparent way, we assign an overall uncertainty rating for each tax gap component in Table 1.1 ranging from ‘very low’ to ‘very high’. Table B.1 provides a guide on the interpretation of the meaning of the overall uncertainty ratings.

Table B.1 Overall uncertainty rating guide

| Overall uncertainty rating | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Very low | Very high confidence that the estimate is close to the actual |

| Low | High confidence that the estimate is close to the actual |

| Medium | The estimate is likely to be close to the actual but there is a possibility that it is different |

| High | Low confidence that the estimate is close to the actual |

| Very high | Very low confidence in the estimate — the actual is likely to be markedly different |

B10. To determine the uncertainty ratings of each tax gap component, we assess the uncertainty arising from each of three sources: the model scope, the methodology used and the data underpinning the estimate.

B11. In assessing model scope, we evaluate each estimate’s methodology against relevant criteria including:

- capture of the appropriate tax base

- coverage of the entire potential taxpayer population within model scope

- accounting for all potential forms of non-compliance

- no overlap between any two components of the tax regime

Table B.2 provides a guide on the interpretation of the uncertainty rating for model scope.

| Overall uncertainty rating | Model scope |

|---|---|

| Very low | Accounts for whole potential tax base and population. Accounts for all potential forms of non-compliance. No overlap with other estimates. |

| Low | Accounts for the large majority of the tax base and population. Accounts for the large majority of potential forms of non-compliance. No overlap with other estimates. |

| Medium | Accounts for most of the tax base and population. Accounts for most potential forms of non-compliance. No overlap with other estimates. |

| High | Missing some of the tax base and population. Some forms of non-compliance are risks not being accounted for. Some potential for overlap with other estimates. |

| Very high | Almost all the tax base and population are missing and almost no risks are being accounted for. Likely overlap with other estimates. |

B12. In assessing the methodology used we assess each estimate’s methodology against relevant criteria including:

- complexity and challenges of the model including the quality and impact of assumptions

- bias in the method, sampling errors (related to sample surveys), or reliability issues

- model volatility, margin of error, ranges and confidence

- external risks that may affect the outcome but are not taken into consideration within the model

Table B.3 provides a guide on the interpretation of the uncertainty rating for methodology.

| Overall uncertainty rating | Model methodology |

|---|---|

| Very low | Few or no sensitive assumptions. It is logical and straight forward with no complex analytical challenges. Model risks are robustly mitigated. |

| Low | Some sensitive assumptions and the model is logical and straightforward with few complex analytical challenges. Model risks are mitigated. |

| Medium | Some sensitive assumptions and challenges. The model is analytically complex with multiple stages. Some external risks with most unlikely and with good risk mitigation. |

| High | Multiple sensitive and unverifiable assumptions. Model may be too analytically complex or simplistic. Many risks, some of which have weak mitigation in place. |

| Very high | Assumption based sensitive model, most of which are unverifiable. Many risks with no strong mitigation. |

B13. In assessing the data underpinning the estimate, for both HMRC and third-party data, we evaluate each estimate’s methodology against relevant criteria including:

- data suitability for purpose

- understanding of data

- sensitivity analysis

Table B.4 provides a guide to the interpretation of the uncertainty rating for data.

| Overall uncertainty rating | Model data |

|---|---|

| Very low | High quality and assured data used throughout (no projecting, no non-detection multiplier uplifts). Completely understood data and highly suitable for use in tax gaps. |

| Low | High quality data (small amount of unsensitive projecting/non-detection multiplier uplifts). Mostly understood data and suitable for use in tax gaps. |

| Medium | Not complete data (a lot of assumptions but all logical and verifiable). Some data not fully understood but still acceptable for use in tax gaps with some caveats. |

| High | Little suitable data and of poor quality. Most of the data is not properly understood, many caveats but no alternative. |

| Very high | No suitable data, what is available is not well understood and is of low quality. |

B14. Table B.5 below shows the uncertainty rating for the tax year 2023 to 2024 for each tax gap component; by model scope, methodology used and data underpinning the estimate, and overall uncertainty rating. The overall uncertainty rating takes into account the relative importance of each uncertainty source for each tax gap estimate component.

Table B.5: Tax gap model uncertainty ratings, 2023 to 2024

| Tax gap model | Scope | Methodology | Data | Overall uncertainty rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporation Tax — mid-sized businesses | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Corporation Tax — small businesses | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Corporation Tax — large businesses | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Alcohol duties — spirits duties | Low | High | High | High |

| Tobacco duties — hand-rolling tobacco duty | Very Low | High | Very High | High |

| Hydrocarbon oils duty | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Alcohol duties — beer duty | Low | High | High | High |

| Other excise duties | Very high | High | High | Very high |

| Tobacco duties — cigarette duty | Very Low | High | Very High | High |

| Self Assessment — non-business taxpayers | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Self Assessment — business taxpayers | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| PAYE — mid-sized business | High | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| PAYE — small business | High | Medium | Low | Medium |

| Self Assessment — large partnerships | Very high | Very high | High | Very high |

| Income Tax, NICs, CGT hidden economy — moonlighters | High | High | High | High |

| Income Tax, NICs, CGT hidden economy — ghosts | Very high | High | Very high | Very high |

| PAYE — large business | High | Very High | Very High | Very high |

| Income Tax, NICs, CGT — avoidance | High | High | High | High |

| Inheritance Tax | High | High | High | High |

| Other taxes, levies and duties | Very high | High | Very high | Very high |

| Landfill Tax | High | Very high | High | High |

| Stamp Duty Reserve Tax | High | Very high | Very high | Very high |

| Stamp Duty Land Tax | Medium | High | High | High |

| VAT | Very Low | Medium | High | Medium |

Notes for Table B.5

-

‘Other excise duties’ includes betting and gaming duties, cider and perry duties, spirit-based ready-to-drink duties and wine duties.

-

Ghosts are individuals whose entire income is unknown to HMRC.

-

Moonlighters are individuals who are known to HMRC in relation to part of their income but have other sources of income that HMRC does not know about.

-

‘Other taxes, levies and duties’ includes Aggregates Levy, Air Passenger Duty, Customs Duty, Climate Change Levy, Digital Services Tax, Insurance Premium Tax, Plastic Packaging Tax and Soft Drinks Industry Levy.

VAT

B15. The theoretical VAT liability and the top-down VAT gap derived from it are broad measures, subject to a degree of uncertainty. They are based on analysis of survey and other data and include several assumptions and adjustments which add both random and systematic variation to the estimates. There is also a small element of forecasting in some of the spending data, which introduces further variation.

B16. It is not possible to produce a precise confidence interval for the VAT revenue loss estimates. The theoretical VAT liability estimate is constructed largely from Office for National Statistics (ONS) National Accounts data which are derived, in the main, from sample surveys and are thus subject to both sampling and non-sampling errors. The ONS does not publish error margins for the relevant input series and so it is not possible to construct an estimate of the impact of these errors on the theoretical VAT liability.

B17. The VAT gap is updated and revised as and when new data become available, or new methodologies are developed. HMRC publishes a revised historical VAT gap series once a year in the ‘Measuring tax gaps’ publication, incorporating both new and updated data and methodological improvements together. The VAT gap preliminary estimate for tax year 2023 to 2024 was published at Autumn Budget 2024 and a second estimate was published alongside Spring Statement 2025.

Excise duties

Systematic biases

B18. Systematic biases are explicitly considered for beer and tobacco products, with results presented as a range to represent the degree of uncertainty. These ranges are discussed in Annex E for beer and Annex F for tobacco products.

B19. No account is presently made for systematic biases in the spirits and diesel estimates.

Random variation

B20. While the upper and lower estimates for beer and tobacco will contain random variation, the resulting confidence intervals are not shown in this document as these estimates are used to represent the uncertainty around our central estimate.

B21. For spirits, an assessment of the effect of random variation is included using error margins. These are estimated by combining the random errors (where available) from all data sources used to calculate total consumption. These approximate to 95% confidence intervals, which is standard across statistical analysis.

B22. For diesel, an assessment of the effect of random variation is included using the error margins resulting from the data used to estimate illicit consumption.

B23. The central estimate for spirits may not necessarily be halfway between the upper and lower bounds as these bounds are confidence intervals, which may not be symmetric about the central estimate. As we do not have appropriate confidence intervals for the beer or tobacco tax gaps, the central estimate is calculated as the mid-point between the upper and lower estimates.

Direct taxes

Systematic biases

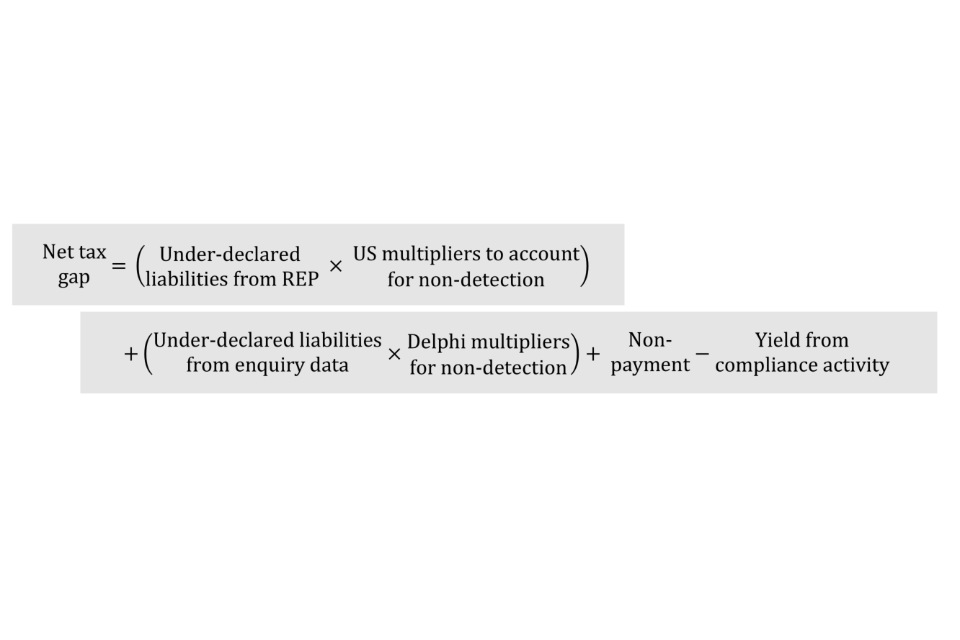

B24. For direct tax gap estimates based on random enquiries, adjustments are made to account for under-declarations of liabilities that are not detected. More information about our approach to non-detection multipliers can be found in HMRC’s working paper ‘Non-detection multipliers for measuring tax gaps’. HMRC continues to undertake analysis to define suitable ranges for other systematic biases in the direct tax estimates.

B25. Direct tax gaps that rely on management information methods measure known components separately. There are also unknown factors that are not fully identified, leading to additional unmeasured losses.

Random variation

B26. Direct tax estimates derived from random enquiries will be subject to random sampling errors — 95% confidence intervals have been calculated for these estimates using standard statistical techniques. These are included as the upper and lower estimates for estimates derived from random enquiries, where the range has been adjusted for non-detection.

Chapter C: Tax gap and compliance yield

C1. Tax gap estimates are calculated net of compliance yield — that is, they reflect the tax gap remaining after HMRC compliance activity.

C2. The cash expected element of compliance yield represents additional tax liabilities due which arise from checks into past non-compliance. Cash expected is tax gap closing and is part of the tax gap calculation for some but not all of the tax gap components. Whilst the tax gap reflects a single tax year, some compliance cases can cover multiple tax years. As a result the year in which cash expected is generated and recorded as compliance yield (and paid) is not always the same as the year to which liabilities relate. Therefore, in a given tax gap year, it is possible that the amount of compliance yield HMRC secures might increase while the percentage tax gap remains unchanged.

C3. HMRC publishes a detailed breakdown of compliance revenues within HMRC’s annual report and accounts. This differs in coverage and timing from the compliance information presented in ‘Measuring tax gaps’. A technical note explains how the methodology for measuring compliance yield in HMRC’s annual report and accounts differs from the methodology for how compliance yield is reflected in the tax gap estimates.

C4. To estimate the tax gap, some methodologies specifically use the cash expected element of compliance yield in the tax gap calculation:

| Tax gap component | Compliance yield |

|---|---|

| Self Assessment | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.1 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. |

| Self Assessment for business taxpayers | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.4 ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. |

| Self Assessment for non-business taxpayers | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.6 ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. |

| Self Assessment for large partnerships | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.8 ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. |

| Self Assessment (excluding large partnerships) | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.9 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025edition’. |

| PAYE | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.11 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. This will represent both actual compliance yield (for closed cases) and estimates of compliance yield (for tax cases which are still under enquiry). |

| PAYE (small businesses) | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.13 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. |

| PAYE (mid-sized businesses) | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.15 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. This will represent both actual compliance yield (for closed cases) and estimates of compliance yield (for tax cases which are still under enquiry). |

| PAYE (large businesses) | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 4.16 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. |

| Corporation Tax | Deducted from gross tax gap; compliance yield series shown in Table 5.1 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. This will represent both actual compliance yield (for closed cases) and estimates of compliance yield (for tax cases which are still under enquiry). |

| Corporation Tax (small businesses) | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 5.2 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. |

| Corporation Tax (mid-sized businesses) | Deducted from gross tax gap; actual compliance yield series shown in Table 5.4 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. This will represent both actual compliance yield (for closed cases) and estimates of compliance yield (for tax cases which are still under enquiry). |

| Corporation Tax (large businesses) | Deducted from gross tax gap; compliance yield series shown in Table 5.5 of ‘Measuring tax gaps 2025 edition’. This will represent both actual compliance yield (for closed cases) and estimates of compliance yield (for tax cases which are still under enquiry). |

| Diesel | Deducted from gross tax gap. |

| Landfill Tax | Deducted from gross tax gap. |

C5. There is a lag in finalising all enquiries relating to a year of liability and our general methodology reflects this. It estimates the value of non-compliance in the liabilities generated each year and subtracts the amount of compliance yield recovered by HMRC in the relevant year. This is a simplified method that does not attempt to assign compliance yield to the year in which the tax liability arose, and it works well when compliance yield from year to year is relatively constant.

C6. Compliance yield for Self Assessment was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022. To preserve validity of assumptions and consistency in the time series, we have adjusted the Self Assessment compliance yield; we allocate the drop in the amount of compliance yield in 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022 and recovered by HMRC to the year of liability. This change is only applied to Self Assessment where there is a material difference on the estimates, and our underlying methodology remains the same. No further adjustments have been applied to compliance yield data for 2022 to 2023 onwards.

C7. For mid-sized businesses PAYE and for mid-sized businesses and large businesses Corporation Tax gaps the established bottom-up statistical methodologies assign compliance yield to the year of liability. As identified risks can take many years to resolve it is necessary to forecast the expected compliance yield from open cases.

C8. In the following components of the tax gap, we either use an estimate of compliance yield as part of the calculation or do not take into account compliance yield:

| Tax gap component | Compliance yield |

|---|---|

| Avoidance (Income Tax, NICs, and Capital Gains Tax) | Compliance yield for open cases is estimated from previous trends in compliance yield for closed cases. |

| Hidden economy — ghosts | Does not currently take account of compliance yield. |

| Hidden economy — moonlighters | Does not currently take account of compliance yield. |

C9. In the remaining components of the tax gap we use a top-down method of calculation, looking at the difference between total theoretical liabilities and tax receipts. Although compliance yield is not explicitly included in these calculations it is reflected as part of tax receipts:

| Tax gap component | Compliance yield |

|---|---|

| VAT | Not explicitly used; but is reflected in receipts. |

| Tobacco duties | Not explicitly used; but is reflected in receipts. |

| Beer and spirit duties | Not explicitly used; but is reflected in receipts. |

Chapter D: Value Added Tax

VAT gap

General methodology

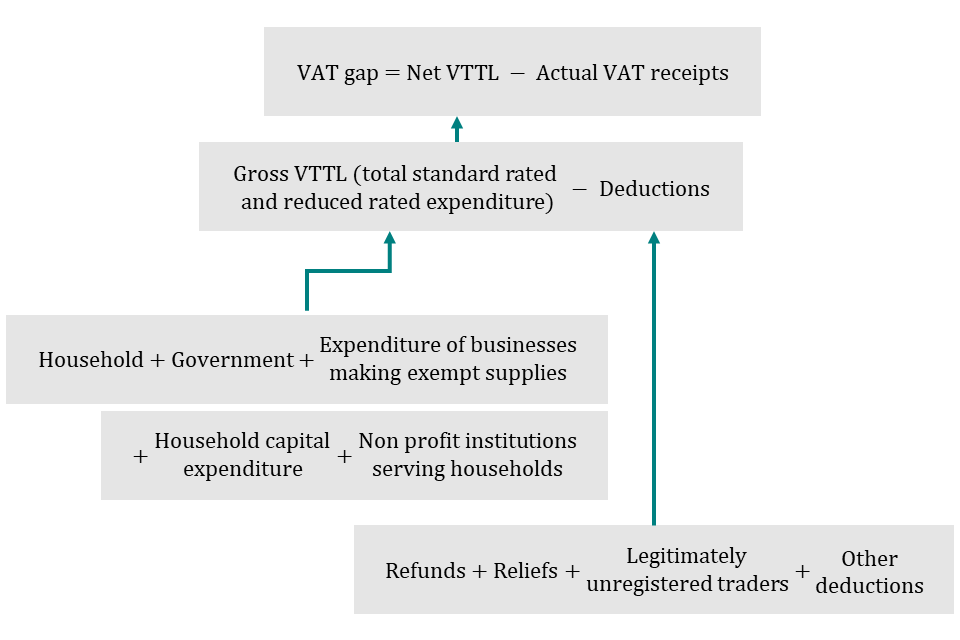

D1. The VAT gap is measured by estimating the total consumption of taxable goods and services to calculate the net VAT total theoretical liability; the VAT gap is the difference between the net VAT total theoretical liability and the VAT received. The VAT gap methodology uses a ‘top-down’ approach which involves:

- gathering data detailing the total amount of expenditure in the economy that is subject to VAT, primarily from the Office for National Statistics

- applying the rate of VAT on the Office for National Statistics’ expenditure data based on commodity breakdowns to derive the gross VAT total theoretical liability

- subtracting any legitimate refunds occurring through schemes and reliefs, to arrive at the net VAT total theoretical liability

- subtracting actual VAT receipts from the net VAT total theoretical liability

- leaving the residual element — the VAT gap, which includes, for example, error, evasion and debt

D2. The VAT total theoretical liability is the amount of VAT that should be collected in theory. This means applying the rate of VAT on that expenditure where VAT should be payable, assuming that there is no fraud, avoidance, or losses due to error or non-compliance.

D3. The VAT total theoretical liability includes irrecoverable VAT, which is the VAT paid on ‘finally taxed expenditure’ which cannot be reclaimed, for example by those not registered for VAT.

D4. The expenditure data series used in the calculation are mainly constituents of National Accounts macroeconomic aggregates. All National Accounts data used to construct VAT total theoretical liability estimates are consistent with the Office for National Statistics’s Blue Book 2024.

D5. More information about the consumer expenditure data sources can be found on the Office for National Statistics website.

Calculation of gross VAT total theoretical liability

D6. The gross VAT total theoretical liability is calculated by multiplying the total amount of expenditure in the economy (also known as VAT-able expenditure) by the appropriate VAT rates.

D7. For each of the expenditure sectors, the total expenditure is split according to the different VAT treatments: zero rated, standard rated, reduced rated, and exempt. For the purposes of calculating the gross VAT total theoretical liability, only the standard and reduced rated expenditure are used.

D8. There were COVID-19 policy measures introduced in 2020 to 2021 which changed the VAT treatments applied to particular types of expenditure. In 2020 to 2021, for example, a zero rate was applied to personal protective equipment expenditure aimed at helping to control the spread of coronavirus. In both 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022 reduced rates were also applied to the hospitality sector, holiday accommodation and attractions. No COVID-19 policy measures were introduced beyond the financial year 2021 to 2022.

D9. The total VAT-able expenditure for each sector is combined to represent an overall annual figure for the economy.

D10. To derive the amount of VAT within the VAT-able expenditure, it is necessary to multiply the expenditure by the VAT fraction (the ratio of the VAT charged on the VAT-able expenditure to the total expenditure). The annual gross VAT total theoretical liability is therefore calculated by multiplying the annual expenditure figure for the economy by the respective VAT fraction.

D11. A number of streams of expenditure contribute to the tax base, with most VAT deriving from consumers’ expenditure (that is, household consumption). The main expenditure categories that comprehensively cover VAT liabilities are:

- household consumption

- non-profit institutions serving households

- government capital and current expenditure - capital and current expenditure from the VAT traders in the VAT exempt sector

- housing capital expenditure

Input tax adjustments

D12. Net VAT liability is the difference between VAT due on taxable supplies made by registered traders (‘output tax’), and VAT recoverable by traders on supplies made to them (‘input tax’).

D13. VAT liability for the relevant categories can be estimated directly from Office for National Statistics’s National Accounts data, with the one exception of the VAT exempt sector. Businesses making outputs that are exempt from VAT are generally not permitted to reclaim all the VAT on inputs associated with their exempt outputs. To make an adjustment for this irrecoverable input tax, a separate HMRC survey is used to ascertain the proportion of purchases on which VAT cannot be reclaimed.

D14. A further adjustment is made for expenditure by businesses which are legitimately not registered for VAT and, as such, cannot recover their input tax. This adjustment uses a combination of data from the Department for Business and Trade and HMRC information on the distribution of business turnover below the VAT threshold to estimate relevant expenditure. This adjustment is made as part of the ‘Deductions’, detailed in the following section.

D15. Because the calculation of irrecoverable input tax is complex, the level of uncertainty around input tax adjustments is larger than for the other elements.

Deductions

D16. The sum of the VAT liability arising from each of the expenditure categories listed in paragraph D11 gives an estimate of the gross VAT total theoretical liability in each year. However, there are several legitimate reasons why part of this theoretical VAT is not actually collected. These can be grouped into 3 broad categories:

- VAT refunds

- expenditure of traders legitimately not registered for VAT

- other deductions

D17. VAT refunds are made primarily to government departments, NHS Trusts and regional health authorities for specified contracted out services acquired for non-business purposes. A number of other categories of expenditure cannot be separately identified in the overall VAT total theoretical liability calculation, for which VAT can be refunded. The value of these refunds is taken directly from audited HMRC accounts data.

D18. Traders who trade below the VAT threshold can legitimately exclude VAT on their sales. Expenditure on the output of these businesses will have been picked up in the total theoretical liability. To adjust for this, an estimate of relevant expenditure is made using a combination of Department for Business and Trade data and HMRC information on the distribution of business turnover below the VAT threshold.

D19. Other deductions will capture other legitimate schemes and reliefs.

Net VAT receipts

D20. Figures for actual receipts of VAT are taken from HMRC’s published tax receipts figures. The receipts are adjusted to reflect timing effects within each tax year, before being used in the model. A summary of HMRC’s tax receipts can be found on GOV.UK.

D21. For the tax years 2019 to 2020 through to 2022 to 2023 the receipts figure includes an adjustment for the payments which were deferred in 2020 under the VAT Payments Deferral Scheme, and those later further deferred under the VAT Deferral New Payment Scheme. This adjustment ensures that all payments (those already received and those expected to be paid) in respect of liabilities related to these years are properly captured in the VAT gap estimates.

VAT gap

D22. Finally, subtracting the net VAT receipts from the net VAT total theoretical liability gives the VAT gap. The percentage gap is calculated by dividing the VAT gap by the net VAT total theoretical liability. Receipts for the tax year (April to March) are compared with the total theoretical liability for the calendar year, assuming an average 3-month lag between an economic activity and the payment of the corresponding VAT to HMRC. Calculations for VAT total theoretical liability and net VAT total theoretical liability assume a 3-month lag between expenditure and actual VAT receipts. Hence, calendar year expenditure data equates to tax year receipts.

D23. The detailed calculations used to construct the estimated VAT total theoretical liability are continuously reviewed to identify improvements to the methodology. Also, the National Accounts data used to construct the VAT total theoretical liability is subject to updates and revisions by the Office for National Statistics throughout the year as final data becomes available.

D24. In summary, the VAT gap is calculated by subtracting actual VAT receipts from the net VAT total theoretical liability. The net VAT total theoretical liability is calculated by subtracting legitimate deductions from the gross VAT total theoretical liability. Legitimate deductions (as described in D16 to D19) are calculated by adding up refunds, reliefs, theoretical VAT paid to legitimately unregistered traders, and other deductions. The method for calculating Gross VAT total theoretical liability is described in D6 to D10.

Non-payment

D25. Alongside the VAT gap estimate, the VAT gap due to non-payment is also estimated.

D26. Non-payment is an estimate of eventual VAT non-payment attributable to the year of tax debt creation. More information on the non-payment methodology can be found in Chapter L Tax gap by behaviour and customer group.

Chapter E: Alcohol

Spirits and beer (upper bound) estimate

Overview

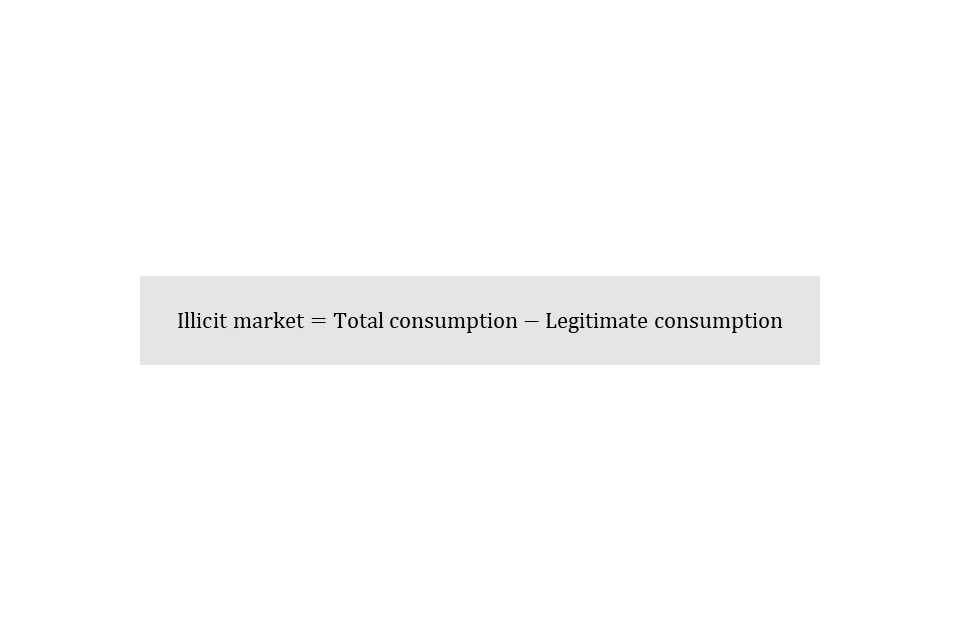

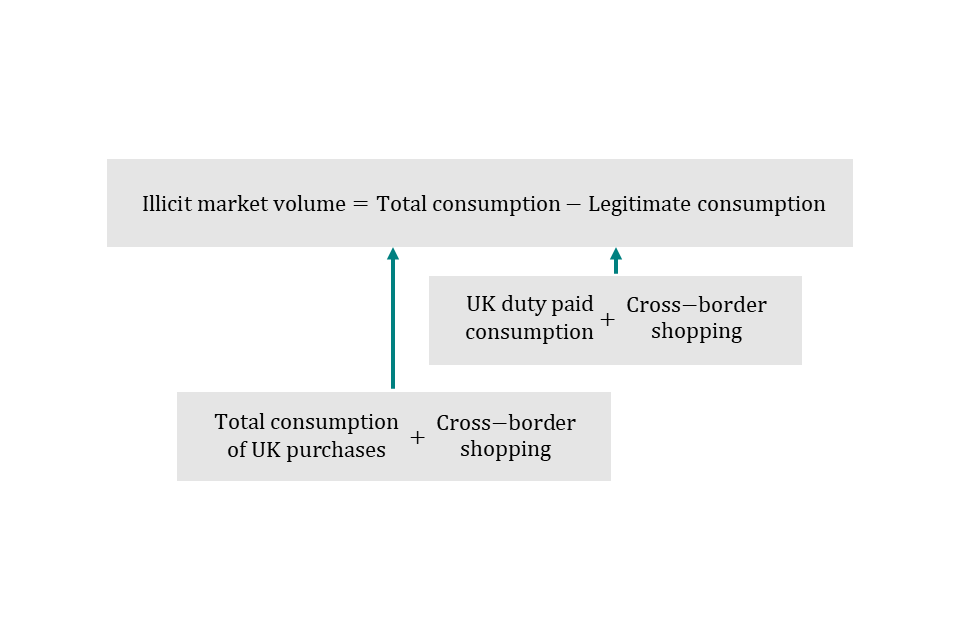

E1. The estimates of the tax gap for spirits and the beer upper bound are produced using a top-down methodology. The estimate is produced by first estimating the volume of total consumption, and then subtracting legitimate consumption, with the residual being the illicit market, from which we derive the tax gap.

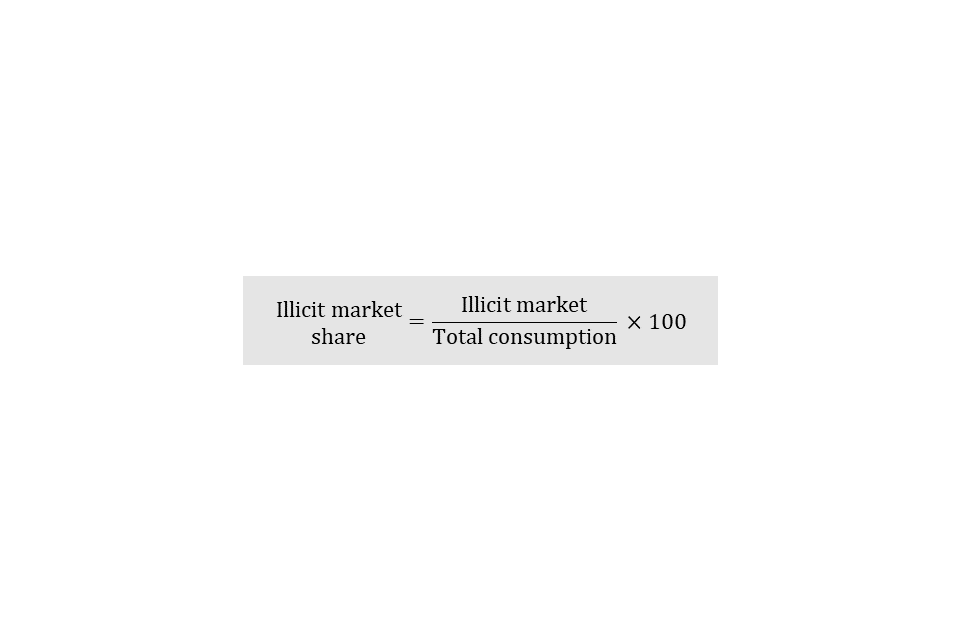

E2. This residual is then turned into an estimate of the proportion of the total market that is supplied through the illicit market by dividing illicit market volume by total consumption volume and then multiplying by 100 to convert it into a percentage. This is termed the illicit market share.

E3. Revenue losses associated with the illicit market are then estimated by combining the illicit market share with data on price, excise duties rates and VAT rates.

E4. Although the spirits and the beer upper bound estimates are calculated using the same underlying methodology there are differences, the three main ones being:

-

the spirits tax gap estimate uses one methodology and is produced with confidence intervals, whilst beer has two methodologies: an upper and a lower bound estimate which are averaged to produce an implied midpoint central estimate

- the spirits and beer estimates use different methods to calculate the uplift factors

- a rolling average is applied to the spirits total consumption estimate to account for the volatility observed

E5. Details of the methodology, including differences, for the estimation of the spirits and beer (upper bound) tax gap are provided in the next sections, followed by the lower bound beer tax gap.

Estimating total consumption

E6. The consumption of spirits or beer bought in the United Kingdom (UK) is estimated using the Living Costs and Food Survey (LCF) from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). LCF estimates are weighted by the ONS to adjust for survey non-response.

E7. Since the LCF only covers purchases within the UK, cross-border and duty-free shopping is added to the consumption of spirits/beer bought in the UK to give total consumption.

Total consumption of UK purchases

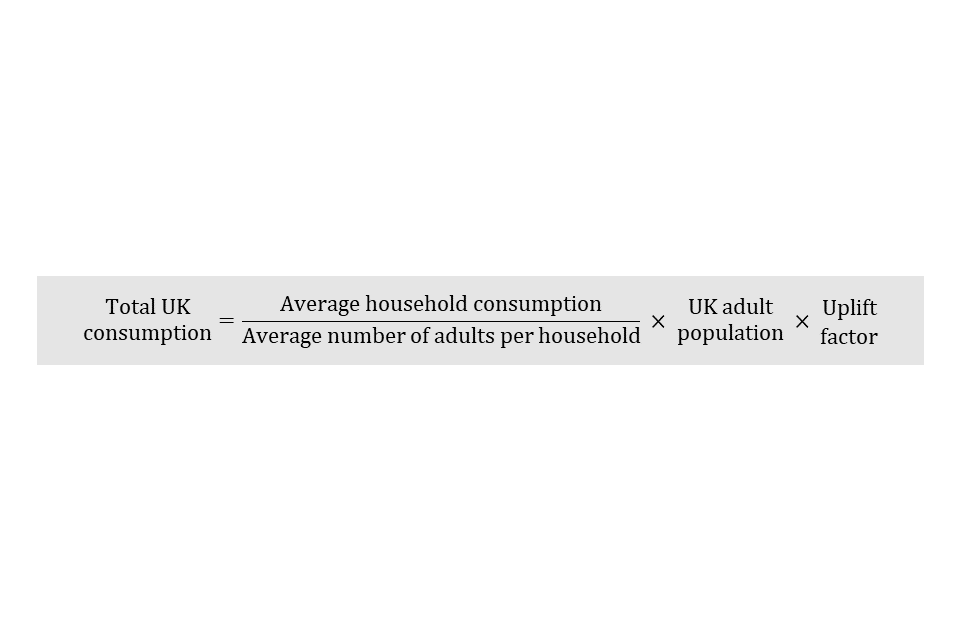

E8. The consumption of UK purchased goods in any given year is calculated using the following:

- estimates of household on-licence (consumed at the point of sale, for example, in a pub or restaurant) and off-licence (consumed off the premises, for example from a supermarket) expenditure on spirits/beer from the LCF

- the average number of people in a household estimated from the LCF

- data on average alcohol prices provided by the ONS

- estimates of the UK adult population (ages 18 or over) from the ONS

- uplift factors calculated independently for on-licence and off-licence sectors

E9. Average adult consumption is estimated by dividing average household consumption by the average number of adults in a household. This is then converted into total UK consumption by multiplying by the UK adult population and then applying an uplift factor.

Living Costs and Food Survey

E10. The average weekly expenditure on spirits and beer for UK households is estimated using the LCF. Households participating in the surveys are asked to record their expenditure on alcohol under the relevant specific category of drink (that is wine, spirits, beer, etc.). There is an additional category for recording drinks purchased as part of a ‘round’ of drinks, which will be referred to as ‘other drinks’.

E11. Some of the ‘other drinks’ purchased will be spirits or beer. The calculation for consumption therefore includes a proportion of ‘other drinks’ purchases.

E12. The average weekly expenditure per household is converted to the volume consumed by that household using the average price of spirits/beer. This is then scaled up to an annual figure.

E13. The average consumption of spirits/beer per household is then converted to the average per person, by dividing by the average number of adults in a household. This is scaled up to the UK adult population.

E14. Most under-age drinking is taken into account in the alcohol models. We assume that adults buy most of the alcohol consumed by minors. This under-age alcohol expenditure is therefore included in the adults’ alcohol consumption and is measured by the survey.

E15. Due to the relatively small sample size in the LCF, the average weekly expenditure for spirits or beer is heavily influenced by extreme expenditure values in the data. Outliers in the data have been capped at the 99th percentile.

Cross-border and duty-free shopping

E16. Duty-free is included in the cross-border shopping calculation. Estimates of consumption of goods purchased as cross-border shopping are based on figures produced from the International Passenger Survey (IPS). This provides estimates of the volume of spirits and beer an average adult traveller brings into the country, separately for air and sea passengers. The IPS figures are weighted by the ONS, scaling up the survey data to represent the total cross-border shopping entering the UK.

E17. An estimate of the volume of duty-free spirits/beer brought into the country is calculated in the same way, using passengers coming from outside the European Union (EU).

E18. This estimate, however, does not cover sales made on-board ferries, so commercially provided data about deliveries of spirits/beer to ferries are used to supplement the cross-border shopping estimate, and provide a complete figure.

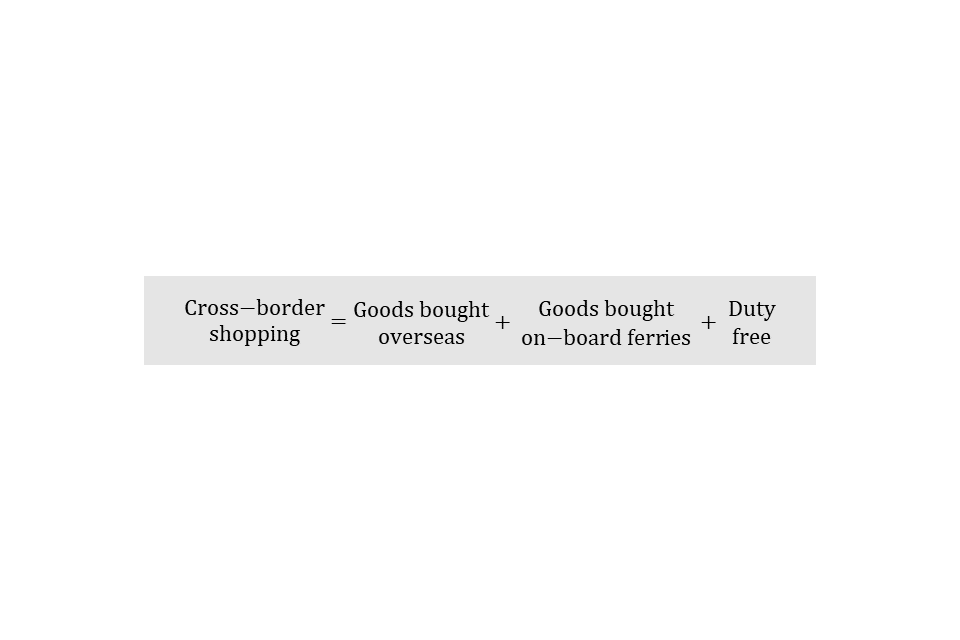

E19. Cross-border shopping is estimated as goods bought overseas, plus goods bought on-board ferries, plus duty-free.

E20. The IPS was suspended during COVID-19 and coverage does not cover all ports. As a result, 2020 to 2021 is projected using a 3-year average of alcohol spending abroad (from 2017, 2018 and 2019 IPS data). This is applied to IPS data on visitor numbers and spending in this period.

From 2021 to 2022 onwards, estimates were adjusted using passenger numbers from the Department for Transport. This account for ports where the IPS had not yet restarted.

Estimates for goods bought on ferries in 2023 to 2024 are based on the average sales from 2022 to 2023. This is due to limited commercial data for earlier years.

Estimating legitimate consumption

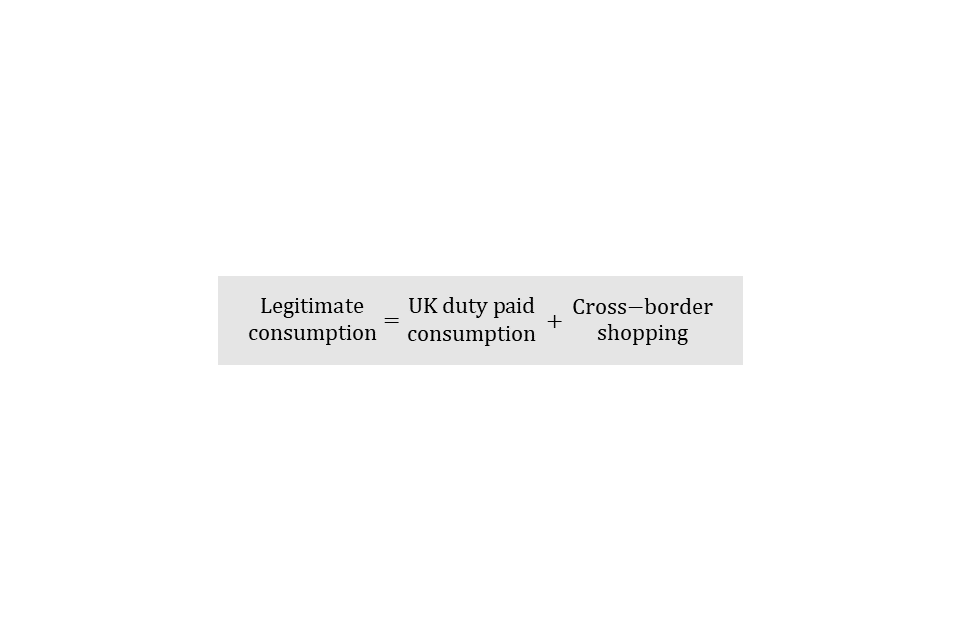

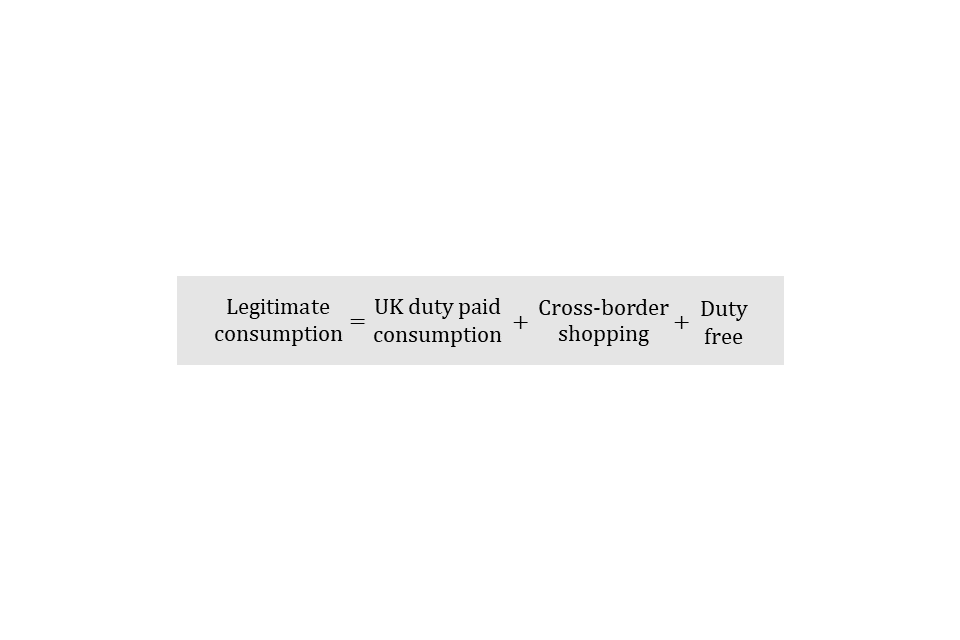

E21. Legitimate consumption is calculated as UK duty paid consumption plus cross-border shopping.

E22. Estimates of UK duty paid consumption are taken directly from returns to HMRC of the volumes of spirits/beer on which duty has been paid. Duty is payable once alcoholic goods are released onto the UK market for consumption. Amounts released are referred to as ‘clearances’. For spirits the volumes of ready-to-drink products have been removed from spirits clearances in order to obtain figures for spirits only.

E23. Cross-border shopping is calculated in the same way as for total consumption: goods bought overseas, plus goods bought on-board ferries, plus duty-free.

Estimating the illicit market

E24. Total consumption is the sum of cross-border shopping (as defined in E19) and total consumption of UK purchases (as defined in E9). The illicit market volume is calculated by subtracting legitimate consumption (as defined in E21) from total consumption.

Conversion to monetary losses

E25. Revenue losses associated with the illicit market are then estimated by combining the illicit market share information with price data, duties rates and VAT rate information. The duty portion is calculated as illicit market volume, multiplied by spirits/beer duty rates. This is summed with the VAT portion, which is calculated as illicit volume, multiplied by average price, multiplied by the VAT fraction.

E26. Data on average spirits/beer prices is derived from data provided by the ONS. The prices used in the model are weighted across on-licence and off-licence and for different types of spirits/beer.

E27. The VAT fraction is the portion of the retail price that is VAT — for example, a 20% VAT rate is equivalent to a one-sixth VAT fraction. VAT fractions are calculated annually to capture changes in the VAT rate. This method assumes that VAT is also lost on all purchases. As, in some cases, the final illicit product is sold in legitimate outlets this may not always be the case, and this will be an overestimate of revenue losses.

E28. For the spirits calculation, spirits duty is converted into bulk duty liabilities based on the assumption that spirit’s strength is constant at 38%.

Spirits uplift factor

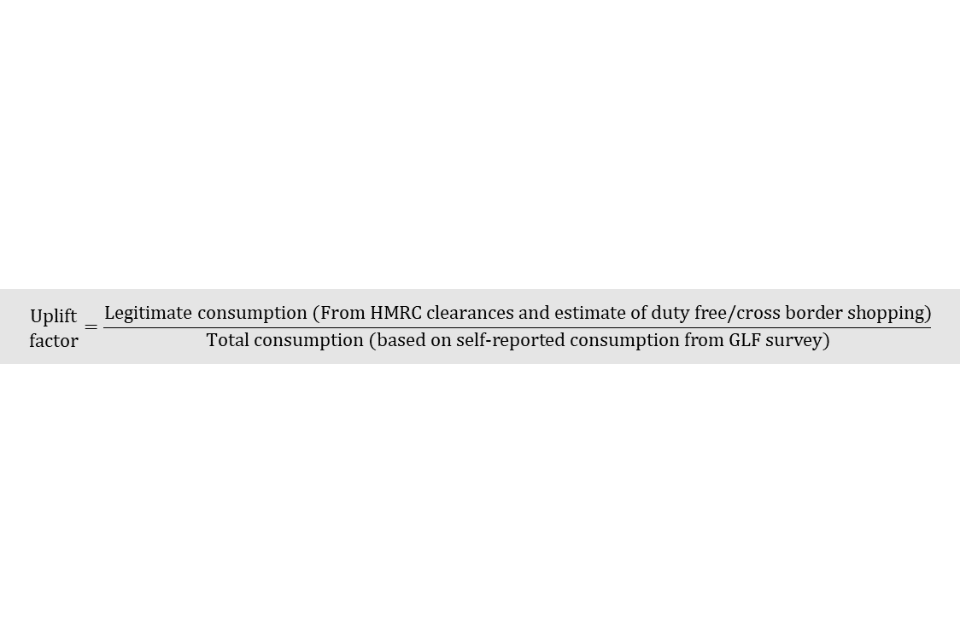

E29. The LCF data for alcohol are subject to under-reporting, they may under-represent certain sub-populations with a high average alcohol consumption, and do not cover the full extent of the alcohol market so an uplift factor is necessary to correct for these biases. This uplift factor is calculated by taking estimates of consumption from the LCF in the base year and comparing these with independent estimates of total consumption.

E30. To do this we take a year in which there is believed to be little or no illicit market and use HMRC clearance data as a true indication of total consumption. In order to reduce sampling error, the uplift factor is derived by taking the average of 3 years of data from the base years: 1990 to 1991, 1991 to 1992 and 1992 to 1993.

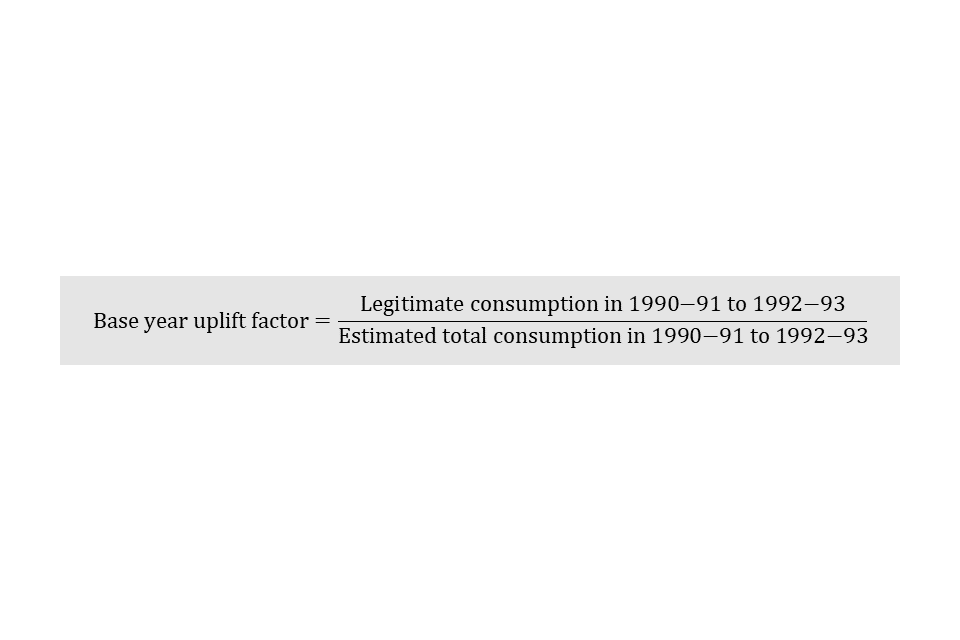

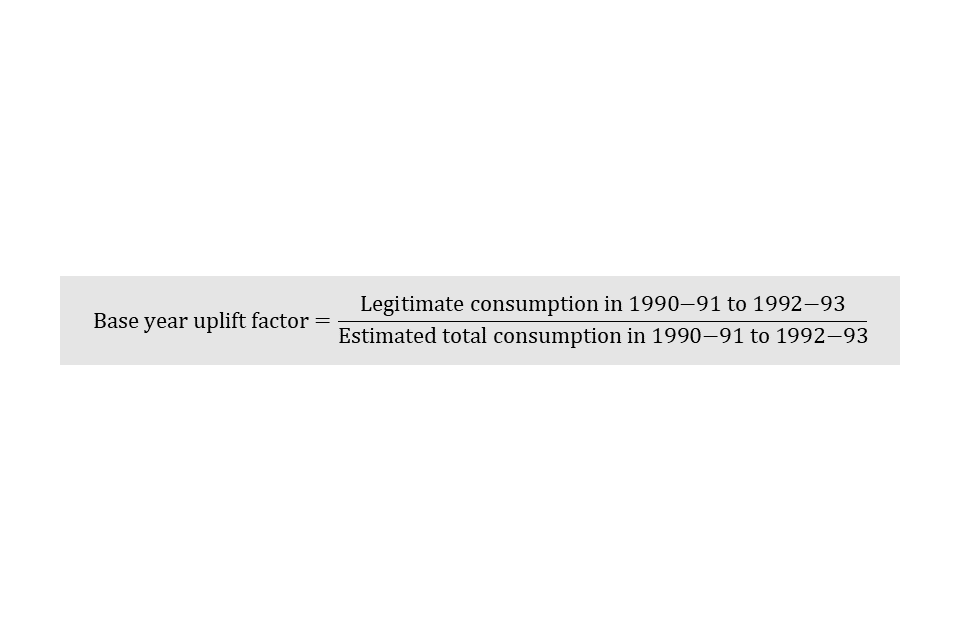

E31. Separate uplift factors are calculated for on-licence and off-licence markets, and the formula is defined as legitimate consumption in the base years, divided by estimated total consumption in the base years.

E32. The uplift factors for on-licence and off-licence are 3.5 and 2.0 respectively.

Beer Uplift factor

E33. The basis for this uplift factor is the same as for spirits, an average of the 3 base years is used where there is assumed to be no illicit market. However, due to the variation in price between draught and packaged beer, a different uplift factor to spirits is required.

E34. To calculate uplift factors for draught and packaged beer, LCF data is split between on-licence and off-licence markets and then into draught and packaged beer. This uses market shares estimated from the ONS and British Beer and Pub Association (BBPA) data.

E35. The base year uplift factors are defined as legitimate consumption in the base years, divided by estimated total consumption in the base years.

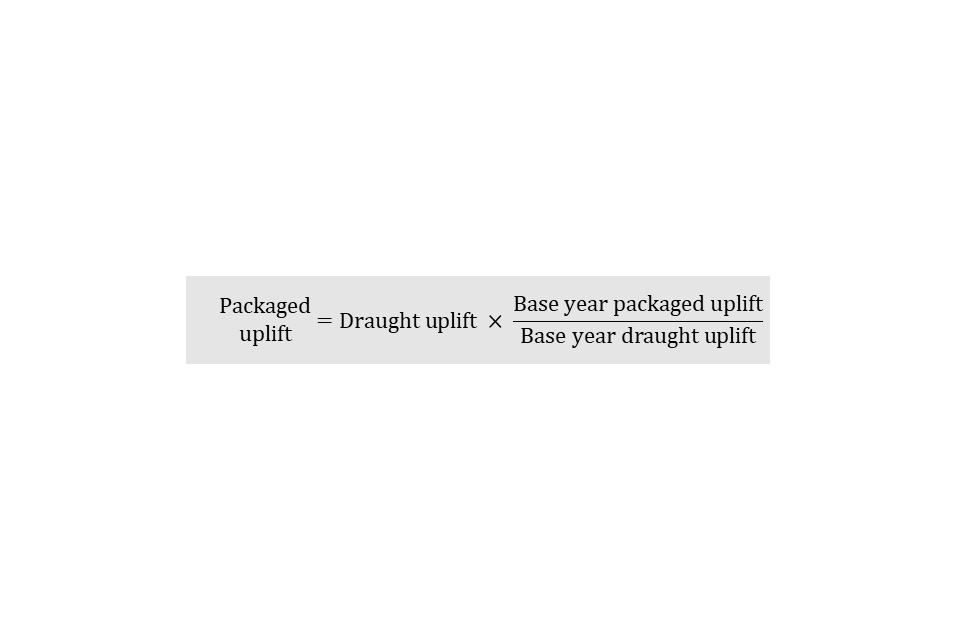

E36. An additional uplift for packaged beer is calculated, which varies year-on-year. This assumes that there is no or a negligible illicit market in draught beer, whereby consumption is equal to clearances in every year. The draught beer uplift and base year uplifts are combined to compute the packaged beer uplift. This is achieved by multiplying the draught uplift in the year of estimation by the ratio of packaged to draught uplifts in the base years.

E37. Since 2020 to 2021, the packaged beer uplift factor has been projected based on an average of the previous 3 years, resulting in an uplift between 2.8 and 3.0. This is due to model sensitivities around the methodology for calculating the uplift factor.

Removing spirit-based ready-to-drinks

E38. Spirit-based ready-to-drinks (RTDs) are packaged beverages that are sold in a prepared form, ready for consumption, such as alcopops.

E39. The LCF expenditure data for spirits includes expenditure on RTDs.

E40. RTDs are currently included in the ‘other excise duties’ estimates, so are removed from the spirits tax gap to avoid double counting. To remove RTDs, we estimate the proportion of total expenditure attributable to ready-to-drinks using data on expenditure from the ONS, and total pure alcohol clearances on spirits and RTDs from HMRC clearances.

Upper and lower confidence intervals in the spirits estimate

E41. The variation in the LCF is used to construct 95% confidence intervals around the central estimate. They indicate the potential size of chance fluctuations in the estimate due to sampling error. They do not take into account systematic error from the model assumptions in the central estimate.

Smoothing spirits total consumption

E42. The number of LCF responses reporting spirits expenditure is small relative to the survey’s sample size and so estimated average household expenditure can vary substantially between years. A 3-year rolling average is applied to the final total consumption estimate for spirits to reduce this volatility and make the tax gap trend clearer.

E43. The spirits tax gap estimate since the tax years 2020 to 2021 has been projected based on the illicit market share for 2019 to 2020. This is due to data from recent years producing unreliable estimates.

Beer lower estimate

Overview

E44. The beer tax gap lower estimate is produced using a bottom-up methodology. This means estimates of the illicit market are made directly, by estimating the fraud components that make up the illicit market. The following types of illicit beer are included in the lower estimate:

- diversion of UK-produced beer

- drawback fraud

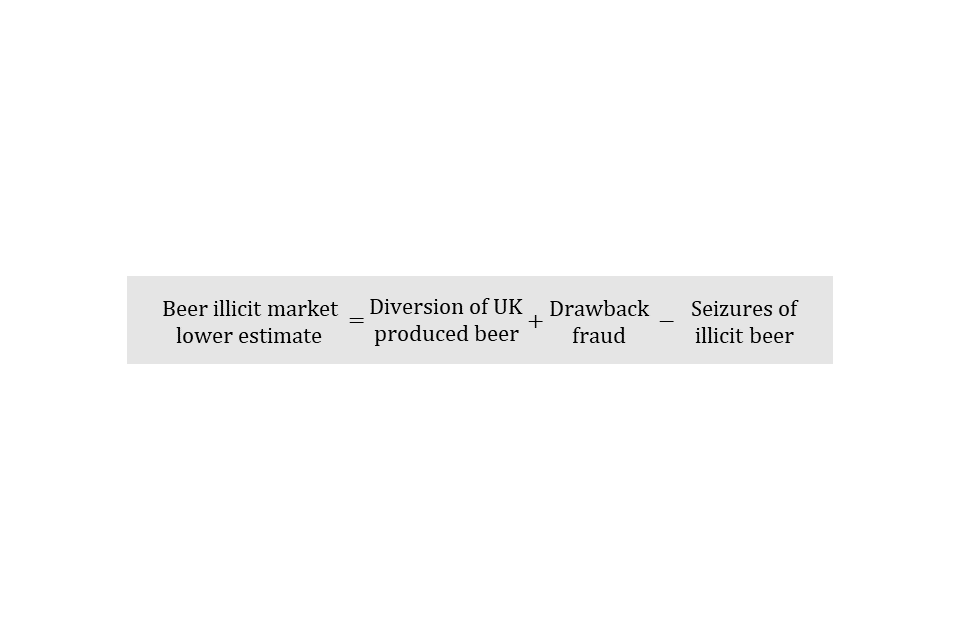

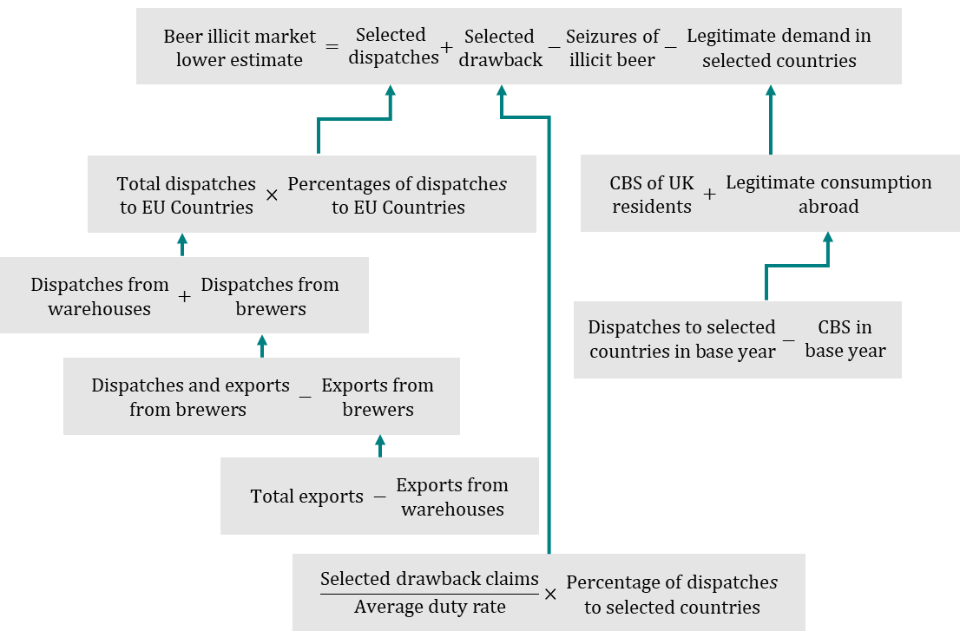

E45. Some of this illicit beer is recovered through HMRC compliance activity, so this is subtracted to give the net tax gap. The tax gap estimate is defined as diversion of UK produced beer, plus drawback fraud, minus seizures of illicit beer.

E46. A number of beer fraud channels are not included in this methodology as we are currently unable to estimate them. This is one of the reasons it is a lower bounding estimate. These include:

- smuggled beer

- diversion of foreign produced beer

- counterfeit beer

- any other fraud we do not know about

Diversion of UK-produced beer

E47. Diversion fraud occurs when beer is moved in duty suspense to the EU and is subsequently diverted back into the UK under the cover of false documentation. The taxes are not declared on the beer and the illicit product enters the UK market.

E48. We estimate that diversion fraud is equal to the amount of beer moved in duty suspense from the UK to certain EU member states, minus legitimate demand for UK branded beer in those countries. That is, we assume that any UK beer which is not feeding demand abroad will be diverted back to the UK illicit market.

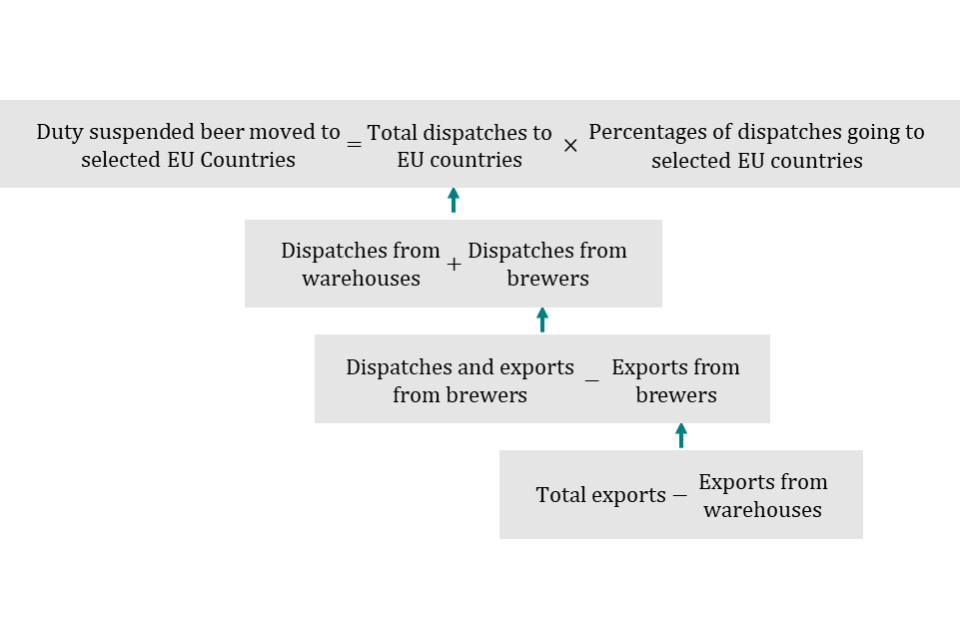

E49. The total amount of beer moved in duty suspense from the UK to the EU includes dispatches from both excise warehouses and brewers. Dispatches from excise warehouses are taken directly from Excise Warehouse Returns (W1 form). Dispatches from brewers are estimated using data from Beer Duty Returns (EX46 form). Total beer dispatches are calculated by summing warehouse and brewer dispatches.

E50. Brewers return data is used for dispatches (movements to EU countries) and exports (movements to non-EU countries) and it cannot be disaggregated. So, to estimate dispatches from brewers, we subtract an estimate of exports from brewers.

E51. Exports from brewers are estimated as total exports, from Customs Handling of Import and Export Freight (CHIEF), minus exports from Excise Warehouse Returns (W1 form).

E52. To preserve the lower bounding nature of this estimate, we only include dispatches to certain EU countries. These countries have been selected based on a number of factors, including: proximity to the UK; the differential in price; operational indications of risk and patterns of supply.

E53. The estimate of beer dispatches, described in paragraphs E48 and E50, cannot be broken down to recipient country. Therefore, we use an alternative data source, UK trade data, which does include a breakdown by country. The proportion of beer dispatched to the selected EU countries is taken from UK trade data and applied to the estimated total dispatches to produce an estimate for dispatches to these selected EU countries.

E54. UK trade data is not used to directly estimate dispatches to these countries as it does not include certain types of movements. More detail is provided on this in paragraph E68.

E55. To summarise, total duty suspended beer moved to selected EU countries is calculated as the product of the percentage of dispatches going to selected EU countries (as defined in E53) and total dispatches to EU countries. Total dispatches to EU countries are defined as the sum of dispatches from warehouses and brewers. Dispatches from brewers must be calculated by subtracting the difference between total exports and warehouse exports from total dispatches and exports from brewers.

Drawback fraud

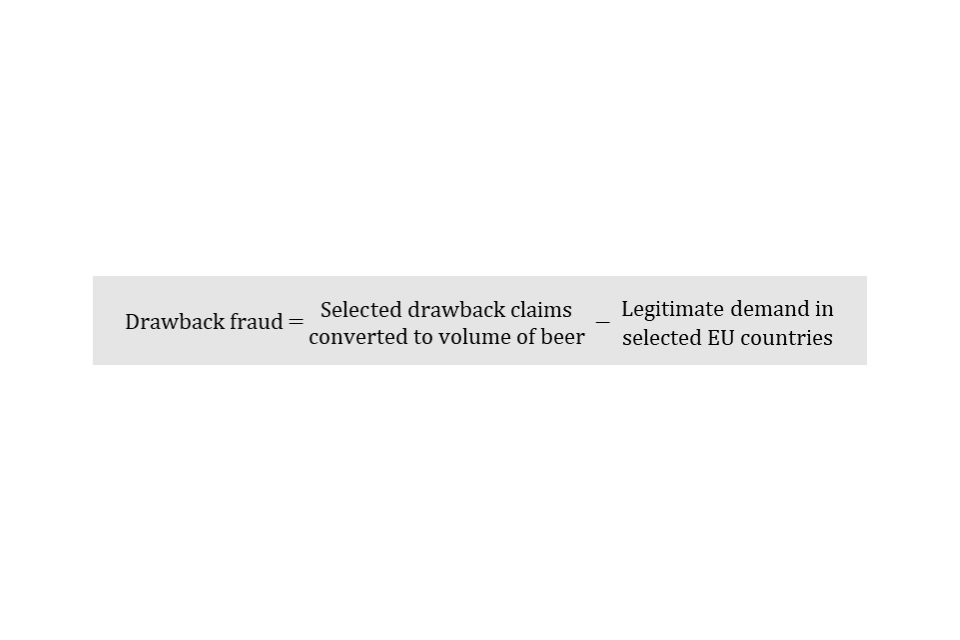

E56. Drawback fraud occurs when goods are moved to the EU and the duty is reclaimed via drawback (a refund of UK beer or spirits duty). Duty is then paid at the lower rate in the destination country and the goods are illicitly returned to the UK.

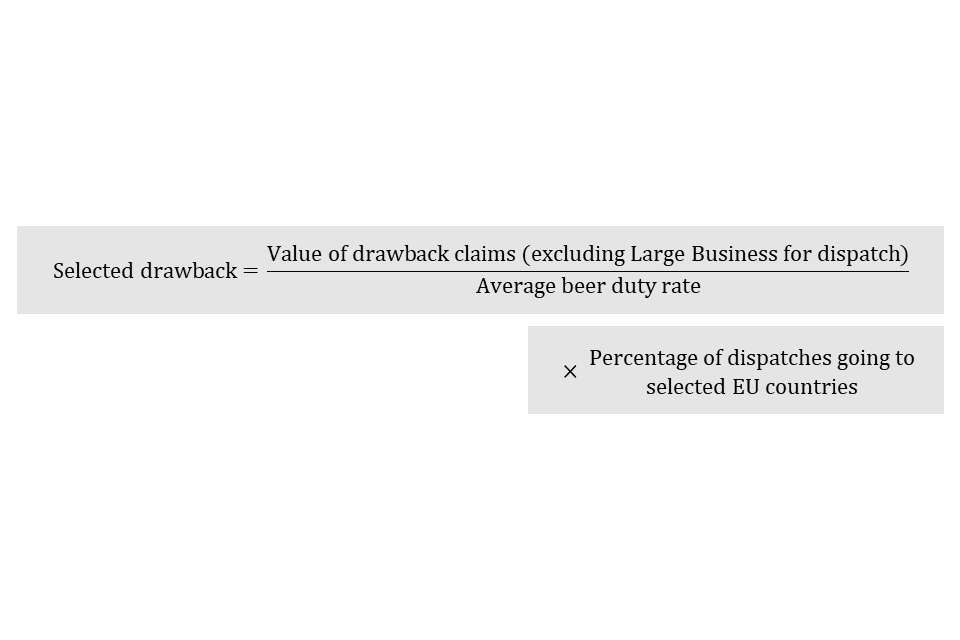

E57. To estimate drawback fraud, we estimate the volume of beer corresponding to certain drawback claims, then subtract the legitimate demand for beer in the selected destination countries.

E58. To preserve the lower bounding nature of this estimate, we only include drawback if it is claimed for dispatch by a business not part of HMRC Large Business. The value of these drawback claims is converted to volume of beer by dividing by the average duty rate for beer.

E59. The volume is then adjusted using the proportion of dispatches going to the selected EU countries. This gives an estimate of the amount of beer going to the selected countries with drawback claimed by small and medium sized enterprises.

Legitimate demand in selected EU countries

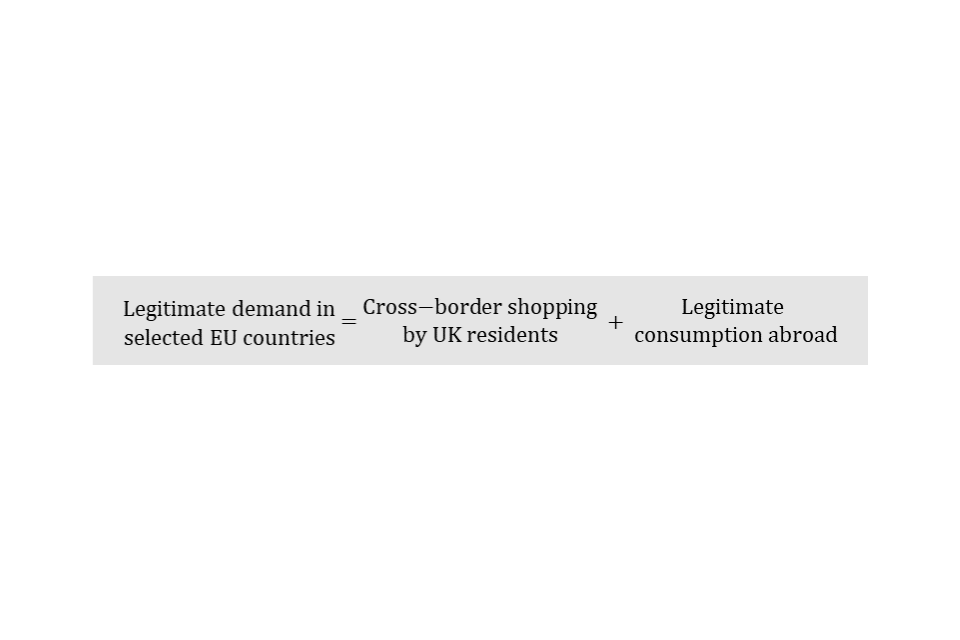

E60. Some of the beer moved to the selected EU countries will be supplying legitimate demand within those countries, rather than being diverted to the UK illicit market. We make one overall estimate of legitimate demand in the selected EU countries and subtract it from the sum of selected beer dispatches and selected beer for drawback.

E61. We have purposely overestimated legitimate demand by only accounting for the riskiest countries, which produces an underestimate of the illicit market, in order to maintain the lower bounding nature of the tax gap estimate.

E62. The estimate of legitimate demand in other countries sums cross-border shopping bought by UK residents and legitimate consumption abroad. The latter may include:

- consumption by UK expatriates

- consumption by UK residents while abroad

- consumption by foreign nationals

- beer in transit to other countries

E63. Cross-border shopping is estimated using data from the IPS. More detail is provided in paragraph E16. Only passengers from the selected EU countries are included.

Legitimate consumption of UK produced beer abroad

E64. We could not find reliable data on legitimate consumption of UK produced beer abroad. So, we estimate it based on the assumption that in a certain year, when the illicit market upper estimate was low, there was negligible illicit activity meaning all dispatches to the selected EU countries were consumed legitimately. This is likely to provide an overestimate of legitimate consumption abroad, as there would likely be some level of fraud in these years. This supports the methodology being a lower estimate of the tax gap.

E65. For stability, an average of 2 years is used: 2000 to 2001 and 2001 to 2002. We refer to these 2 years as the ‘base year’.

E66. Brewers return data is not available for years prior to 2007. Consequently, we use an alternative data source, UK trade data, to estimate dispatches in the base year.

E67. In the base year we assume that all dispatches supply either cross-border shopping by UK residents or legitimate consumption abroad. We subtract an estimate of cross-border shopping in the base year from dispatches in the base year; the remainder is assumed to be legitimate consumption abroad.

E68. We believe that UK trade data may underestimate beer dispatches in the base year as it does not record certain types of beer movement. These include:

- goods in transit

- deliveries to embassies

- deliveries to Navy, Army, and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI)

E69. Additionally, as the threshold for recording goods on UK trade data is relatively high, beer may have a higher proportion of small traders than other commodities. This may mean the standard adjustment applied to UK trade data to account for small traders may be too low for beer.

E70. To account for these concerns, we uplift the UK trade data. There is very little evidence to indicate the actual scale of uplift required. Comparison with our calculated dispatches in later years led us to apply a factor of 2. Again, the high level of this adjustment may result in this being an overestimate of legitimate demand. This is in keeping with the lower bounding methodology for the tax gap, as higher legitimate demand would see a lower estimate for the illicit market.

Illicit market lower estimate

E71. To summarise, the beer illicit market lower estimate is calculated by summing selected dispatches (as defined in E55) and selected drawback (as defined in E58 and E59), before subtracting seizures of illicit beer and legitimate demand in selected countries. Legitimate demand in selected countries is defined as cross-border shopping (CBS) of UK residents plus legitimate consumption abroad (as defined in E67).

E72. Since the tax year 2016 to 2017, the beer illicit market lower estimate has been projected to better reflect changes in fraud. This is calculated by keeping the gross tax gap constant, whilst using operational intelligence as a proxy to capture the impact of changes in the illicit market.

Implied mid-point estimate

E73. The implied mid-point estimate is calculated as the average of the upper and lower estimates. It is only intended as an indicator of long-term trend — the true tax gap could lie anywhere within the bounds.

E74. The bounds do not take account of any systematic tendency to over- or under-estimate the size of the tax gap that might arise from the modelling assumptions.

Wine central estimate

E75. We have not estimated the illicit market share for wine due to the unavailability of a key commercial data source previously used to estimate the wine tax gap. We therefore include wine within our tax gap estimate for ‘Other excise duties’, which is based on an illustrative method. See ‘Chapter J: Other taxes’.

Chapter F: Tobacco

Overview

F1. The estimate of the tax gap for tobacco is produced using a top-down methodology. We estimate the volume of total consumption, and then subtract legitimate consumption. The residual is the estimated illicit market, from which we derive the tax gap.

F2. The proportion of the total market that is supplied through the illicit market is determined by dividing illicit market volume by total consumption volume. This is termed the illicit market share.

F3. Revenue losses associated with the illicit market are then estimated by combining the illicit market share with the related market prices, excise duty rate and VAT rate.

Methodology

F4. The estimates of the illicit market for cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco are produced using a top-down methodology, as described in paragraphs F1 to F3. Adding both elements together gives an estimate for the overall tobacco tax gap.

F5. The methodology used for all tax years excluding 2020 to 2021 to 2022 to 2024 is based on the descriptions set out in the ‘total consumption’ section below. The calculations of legitimate consumption apply to all years.

F6. For the three tax years from 2020 to 2021 up to 2022 to 2023 the Office for National Statistics temporarily removed tobacco consumption questions from their Opinions and Lifestyle Survey used to calculate total consumption. These questions have been introduced again from tax year 2023 to 2024. We have projected these missing years using linear interpolation of the illicit market share in the tax years 2019 to 2020 and 2023 to 2024.F7. To account for a change in the survey design, we adjust consumption data for tax years 2018 to 2019 and 2019 to 2020. This model adjusts data from the tax year 2018 to 2019 to tax year 2019 to 2020 based on time series discontinuity analysis produced by the Office of National Statistics and an uplift factor based on AB testing of question design. We apply this uplift to average daily consumption survey data.

Total consumption

F8. The total consumption in any given year is calculated using the following:

-

estimates of prevalence (proportion of the population that smoke from the General Lifestyle Survey, the Opinions and Lifestyle Survey and Health Survey for England)

- estimates of consumption per smoker from the General Lifestyle Survey, the Opinions and Lifestyle Survey and Health Survey for England

- estimates of the adult population (ages 16 or over) from the Office for National Statistics

- an uplift factor to account for under-reporting of self-declared tobacco consumption

F9. The estimate of total UK cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco consumption for each year is a product of the estimates of cigarette and hand-rolling tobacco smoking prevalence and consumption per smoker for declared and undeclared smokers.

F10. . We uplift estimated consumption figures to account for survey non-declaration using medical evidence collected during Health Survey for England.

Uplift factor

F11. Separately to account for under-declaration of tobacco consumption, we apply an uplift factor calculated by taking estimates of total consumption from the General Lifestyle Survey in a base year. In cigarettes the base year is 1996 to 1997, and in hand-rolling tobacco it is an average of 3 years, 1983 to 1986. Estimates of total consumption in base years are compared with consumption of actual clearances to HMRC and an estimate of legitimately purchased cigarettes from abroad.

F12. The uplift factors for the cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco estimates are 1.5 and 1.1 respectively.

Upper and lower bounds for total consumption

F13. The uncertainties in the survey data used to create these estimates mean that it is not possible, with sufficient accuracy, to produce a single point estimate of total consumption. However, due to the methodology we use, it is difficult to produce confidence intervals. Instead, we use the survey data to produce an upper bound and lower bound for total consumption. This allows us to produce a range for total consumption that takes account of the uncertainty in the underlying data.

F14. The one difference between the upper and lower bound calculations is the treatment of dual smokers. Dual smokers are individuals who consume both cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco. In the upper bound calculation, the majority of the dual smokers are considered to be cigarette smokers. In the lower bound estimate, we assume that the majority smoke hand-rolling tobacco. This is explained further in the following tables and sections.

Table F.1 Cigarettes upper and hand-rolling tobacco lower bound assumptions

| Allocation of total tobacco consumption for estimates | Allocation of total tobacco consumption for estimates | |

|---|---|---|

| Opinions and Lifestyle Survey Options | Cigarette upper bound assumption | Hand-rolling tobacco lower bound assumption |

| Cigarettes only | 100% | 0% |

| Dual smokers: cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco, but mainly cigarettes | 99% | 1% |

| Dual smokers: cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco, but mainly hand-rolling tobacco | 49% | 51% |

| Hand-rolling tobacco only | 0% | 100% |

Table F.2 Cigarettes lower and hand-rolling tobacco upper bound assumptions

| Allocation of total tobacco consumption for estimates | Allocation of total tobacco consumption for estimates | |

|---|---|---|

| Opinions and Lifestyle Survey Options | Cigarette lower bound assumption | hand-rolling tobacco upper bound assumption |

| Cigarettes only | 100% | 0% |

| Dual smokers: cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco, but mainly cigarettes | 51% | 49% |

| Dual smokers: cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco, but mainly hand-rolling tobacco | 1% | 99% |

| Hand-rolling tobacco only | 0% | 100% |

F15. The upper bound of total cigarette or hand-rolling tobacco consumption is calculated firstly by estimating consumption levels from smokers who only smoked cigarettes or hand-rolling tobacco. This is added together with a maximum consumption of cigarettes or hand-rolling tobacco that could be smoked by dual smokers.

F16. The lower bound of total cigarette or hand-rolling tobacco consumption is calculated firstly by estimating consumption levels from smokers who only smoked cigarettes or hand-rolling tobacco. This is added together with a minimum consumption of cigarettes or hand-rolling tobacco that could be smoked by dual smokers.

F17. Tobacco tax gap estimates up to and including quarter 3 of 2011 to 2012 use the General Lifestyle Survey as the base estimate for tobacco consumption. These estimates are supplemented with Opinions and Lifestyle Survey data on dual smokers where this is added/subtracted to obtain the upper and lower bounds. All years from quarter 4 of 2011 to 2012 are based on Opinions and Lifestyle Survey data only.

Legitimate consumption

F18. Estimates of legitimate consumption include:

- UK duty paid consumption

- Cross-border and duty-free shopping

UK duty paid consumption

F19. Estimates of UK duty paid consumption are taken directly from tax returns to HMRC (clearance data) on the volumes of cigarettes and hand-rolling tobacco on which duty has been paid, along with the actual amounts of money.

Cross-border and duty-free shopping

F20. Estimates of consumption of goods purchased as cross-border shopping are based on data from the International Passenger Survey (IPS). This provides estimates of the number of cigarettes and/or hand-rolling tobacco that an average adult traveller brings into the country, separately for air and sea passengers. The IPS figures are weighted by the Office of National Statistics, scaling up the survey data to represent the total cross-border shopping entering the UK.

F21. This estimate, however, does not cover sales made on-board ferries. Commercially provided data about deliveries of cigarettes to ferries is used to supplement the cross-border shopping estimate.

F22. Duty-free cigarettes/hand-rolling tobacco brought into the UK are also estimated from the IPS, using passengers coming back from outside the EU.

F23. Legitimate consumption is estimated as UK duty paid consumption, plus cross-border shopping, plus duty-free.

F24. The IPS was suspended during COVID-19 and coverage does not cover all ports. As a result, 2020 to 2021 is projected using a 3-year average of tobacco spending abroad (from 2017, 2018 and 2019 IPS data). This is applied to IPS data on visitor numbers and spending in this period. From 2021 to 2022 onwards, estimates were adjusted using passenger numbers from the Department for Transport. This account for ports where the IPS had not yet restarted. Estimates for goods bought on ferries in 2023 to 2024 are based on the average sales from 2022 to 2023. This is due to limited commercial data for earlier years.

Conversion to monetary losses

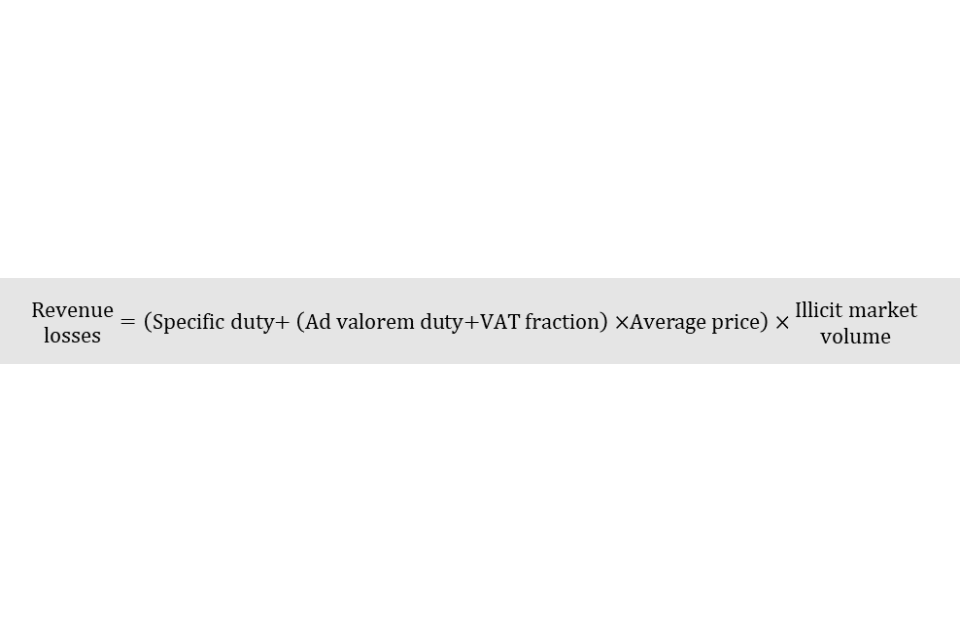

F25. All calculations to this point have been made on volumes of cigarettes or hand-rolling tobacco. Revenue losses associated with the illicit market are then estimated by combining the illicit market share information with price data, duty, and VAT rate information. Volumes are converted to estimates of revenue losses by multiplying by the sum of specific duty and ad valorem liabilities. Ad valorem liabilities are calculated as average price multiplied by the sum of ad valorem duty and the VAT fraction.

F26. The average price is taken as the weighted average price of all cigarettes or hand-rolling tobacco that were UK duty paid. The weighted average price is calculated by weighting the retail price of each product by the share of clearances in the cigarette or hand-rolling tobacco market.

F27. The VAT fraction is the proportion of the retail price that is VAT — for example, a 20% VAT rate is equivalent to a one-sixth VAT fraction. VAT fractions are calculated annually to capture changes in the VAT rate. This method assumes that VAT is also lost on all purchases. In some cases, the final illicit product is sold in legitimate outlets where VAT is paid, so this method results in an overestimate of revenue losses.

Summary of cigarette methodology

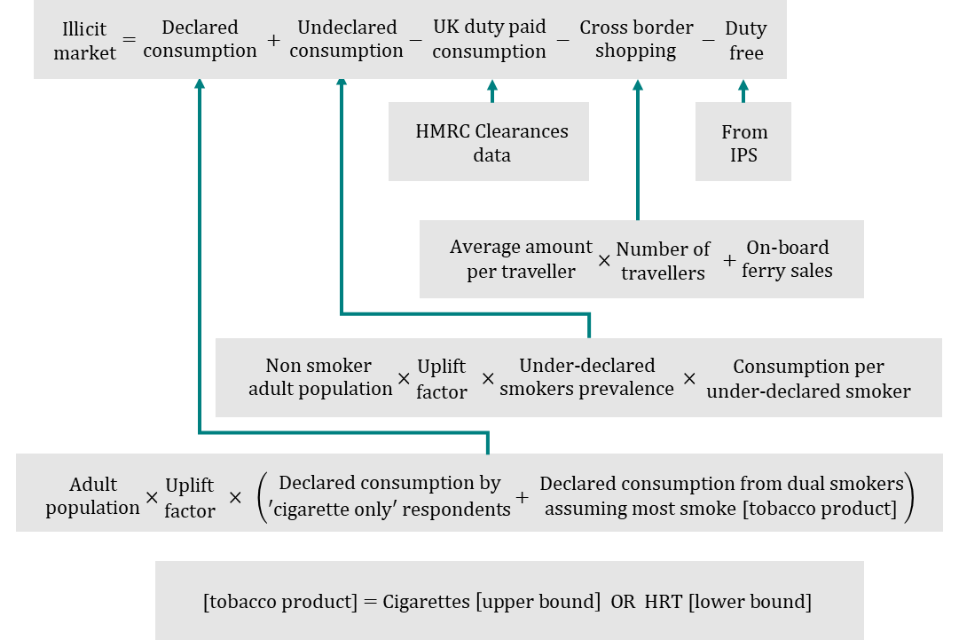

F28. In summary, the illicit market for cigarettes is calculated as the sum of declared and undeclared consumption, minus legitimate consumption.

F29. Declared consumption is defined as the total adult population multiplied by the uplift factor, multiplied by the sum of declared consumption by cigarettes and dual smokers. The upper bound assumes most dual smokers smoke cigarettes, whilst the lower bound assumes most smoke hand-rolling tobacco. Undeclared consumption is defined as the product of the non-smoker population, the uplift factor, the under-declared smokers’ prevalence, and the consumption per under-declared smoker.

F30. Legitimate consumption is defined as UK duty paid consumption (from HMRC clearance data), plus cross-border shopping (the sum of on-board ferry sales and the average amount per traveller, multiplied by the number of travellers), plus duty-free (from the International Passenger Survey).

Summary of hand-rolling tobacco methodology

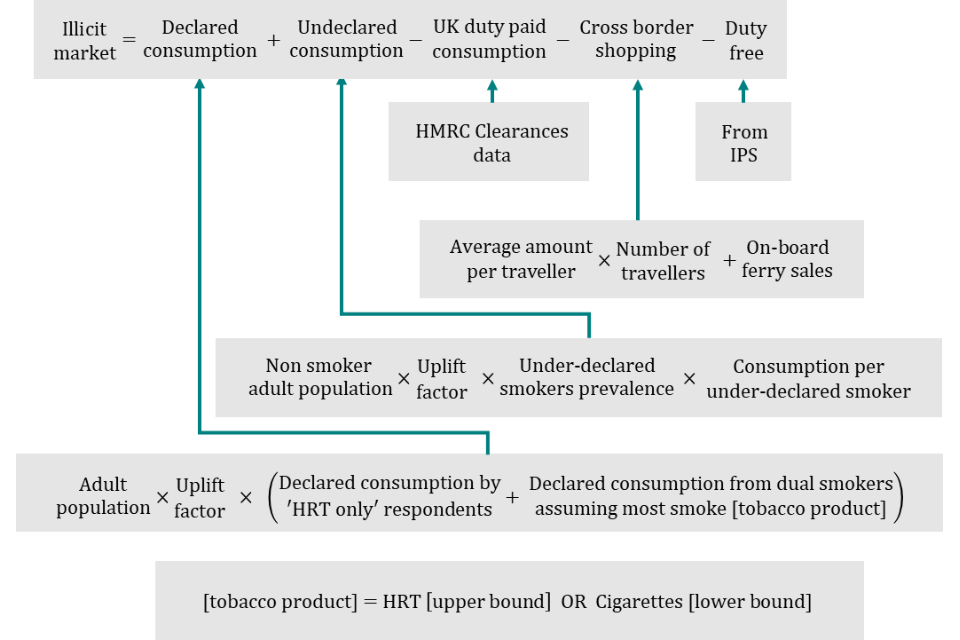

F31. In summary, the illicit market for hand-rolling tobacco is calculated as the sum of declared and undeclared consumption, minus legitimate consumption.

F32. Declared consumption is defined as the total adult population multiplied by the uplift factor, multiplied by the sum of declared consumption by hand-rolling tobacco and dual smokers. The upper bound assumes most dual smokers smoke hand-rolling tobacco, whilst the lower bound assumes most smoke cigarettes. Undeclared consumption is defined as the product of the non-smoker population, the uplift factor, the under-declared smokers’ prevalence, and the consumption per under-declared smoker.

F33. Legitimate consumption is defined as UK duty paid consumption (from HMRC clearance data), plus cross-border shopping (the sum of on-board ferry sales and the average amount per traveller, multiplied by the number of travellers), plus duty-free (from the International Passenger Survey).

Chapter G: Hydrocarbon oils (fuel duty)

G1. The hydrocarbon oils duty gap is estimated using a combination of established top-down and bottom-up methodologies based on fuel consumption data and a random enquiry programme for the use of illicit diesel. The methodologies outlined in this chapter will refer to the diesel tax gap.

G2. The misuse of other fuels (for example, petrol) has been excluded on the basis that this is believed to be negligible, the scale of which is not currently quantifiable. Other fuel duties do however form a part of hydrocarbon oils duty total theoretical liabilities.

Methodology

G3. A bottom-up methodology is used to estimate the diesel tax gap from the tax year 2016 to 2017 onwards based on random enquiry programme data. The Great Britain (GB) and Northern Ireland (NI) diesel tax gaps are calculated separately but the methodologies are identical.

G4. Figures prior to 2016 to 2017 are calculated using a top-down methodology based on fuel consumption data. This methodology was no longer fit for purpose from the tax year 2013 to 2014 as it was not sensitive enough to accurately measure the low tax gap. This meant the estimates for 2013 to 2014 were rolled forward for 2014 to 2015 and 2015 to 2016 before a bottom-up approach was introduced in 2016 to 2017.

G5. Since previous years are based on a top-down methodology, figures from 2016 to 2017 onwards are not directly comparable to these.

G6. The methodology below describes the bottom-up approach used from 2016 to 2017.

G7. Summary of methodology:

- legitimate consumption is based on the returns that HMRC receives from the volumes of diesel on which duties have been paid (HMRC clearances)

- illicit consumption is estimated using the proportion of vehicles found to be misusing rebated fuel (fuel taxed at a reduced rate) in random sample surveys conducted by HMRC in 2017, 2020 and 2023

- revenue losses (gross tax gap) associated with illicit consumption are estimated using average retail prices, duty rates and VAT rates

- the net tax gap is then calculated as the gross tax gap minus compliance yield.

Estimating total consumption

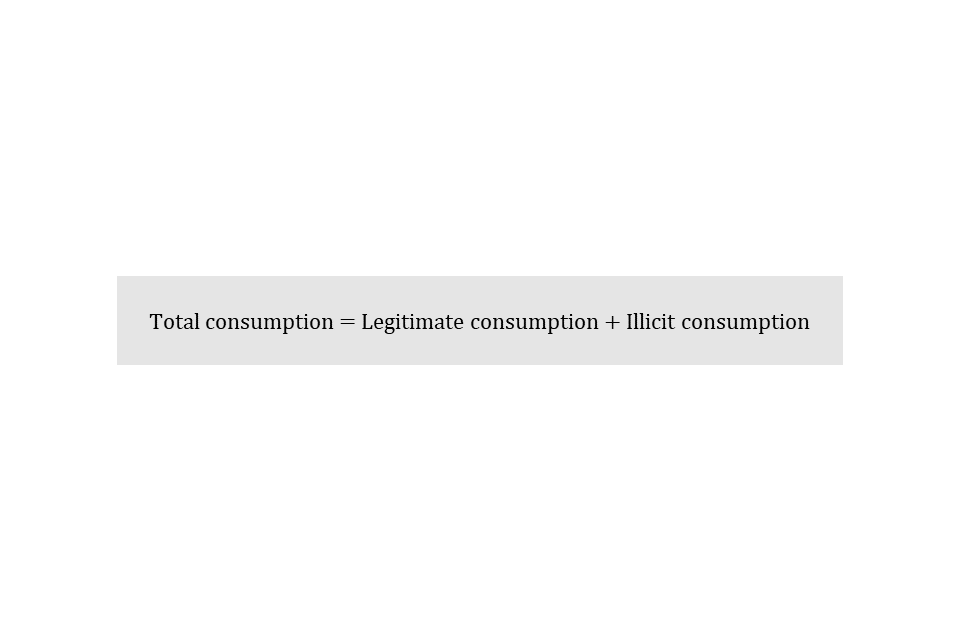

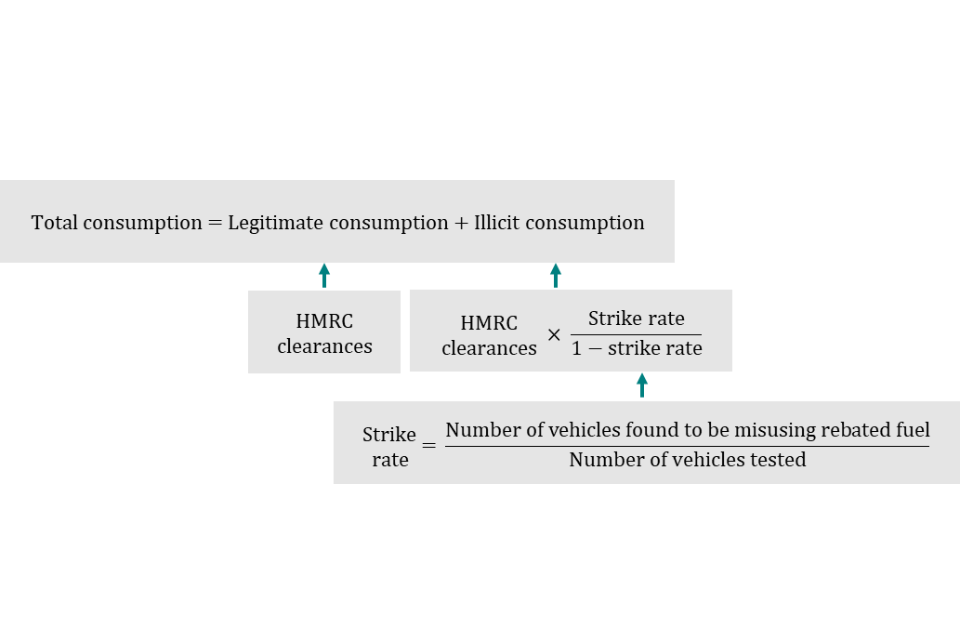

G8. Total consumption is calculated as legitimate consumption plus illicit consumption.

G9. HMRC conducted random surveys in April to June 2017, January to March 2020 and September to November 2023, where vehicles were stopped at the roadside and tested for illicit diesel. In all surveys, a stratified sample of 1,900 vehicles across the UK (1,500 in GB and 400 in NI) was used. The sample was stratified by vehicle type and region to ensure the results were representative of all vehicles across the UK.

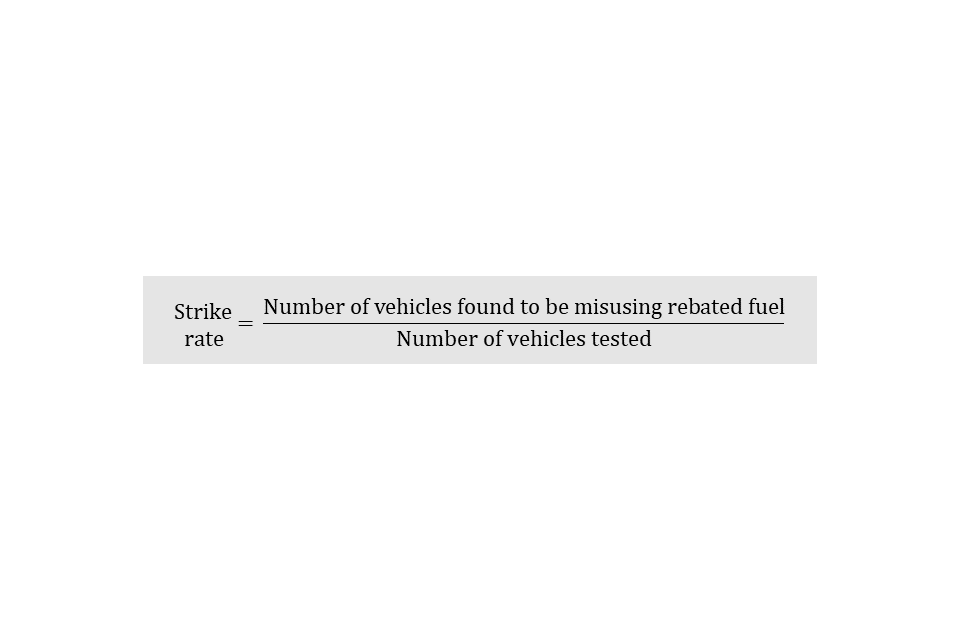

G10. The proportion of vehicles found to be misusing rebated fuel in each survey is referred to as the strike rate. This is calculated by taking the number of vehicles found to be misusing rebated fuel divided by the number of vehicles tested. The strike rate is used as an estimate of the proportion of vehicles misusing rebated fuel in the UK.