How many people are detained or returned?

Published 26 May 2022

Back to ‘Immigration statistics, year ending March 2022’ content page.

This is not the latest release. View latest release.

Data on immigration detention relate to the year ending March 2022 and most comparisons are with the year ending March 2020 (two years previous, reflecting a comparison with the period prior to the Covid-pandemic). All data include dependents, unless indicated otherwise.

Data on returns relate to 2021, to allow more time for returns to be recorded on the system and ensure the published figures are an accurate representation of the number of returns. Most comparisons are with 2019 (two years previous, reflecting a comparison with the period prior to the Covid-pandemic). All data include dependents, unless indicated otherwise.

See the user guide for more details.

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic. A range of restrictions were implemented in many parts of the world, and the first UK lockdown measures were announced on 23 March 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the UK immigration system, both in terms of restricting migrant movements to and from the UK and the impact on operational capacity. Year ending comparisons that follow will include impacts resulting from the restrictions put in place during this period of the pandemic.

This section contains data on:

- Individuals detained under Immigration Act powers

- Returns of people who do not have any legal right to stay in the UK

1. Immigration detention

1.1 People entering immigration detention

25,282 people entered immigration detention in the year ending March 2022, almost double the previous year (when there was a large fall following the COVID-19 outbreak) and 9% higher than pre-pandemic levels in the year ending March 2020 (23,118). The profile of detainees and their length of detention has changed. Since the pandemic, an increasing proportion of those entering detention have been recent clandestine arrivals detained for short periods in order to confirm their identity and provide initial support on arrival, with most subsequently entering the regular asylum system.

There has been a general downward trend in the number of people entering detention since the peak in 2015, as shown in Figure 1, when over 32,000 people entered detention.

Figure 1: People entering immigration detention in the UK, year ending March 2013 to year ending March 2022

Source: Immigration detention - Det_D01

Iranians were the most common nationality entering detention in the latest year, accounting for 18% of the total, or 4,507 entrants, close to two and a half times pre-pandemic levels in the year ending March 2020. Albanians were the next most common with 4,253 entrants, 25% higher than the year ending March 2020. The top 10 nationalities entering detention are mainly the same nationalities as the recent clandestine arrivals to the UK via small boats (as reported in the Irregular Migration to the UK, year ending March 2022, Home Office report), emphasising the role immigration detention has played in managing these new arrivals. The majority of other nationalities, however, remain below pre-pandemic levels.

1.2 People in immigration detention

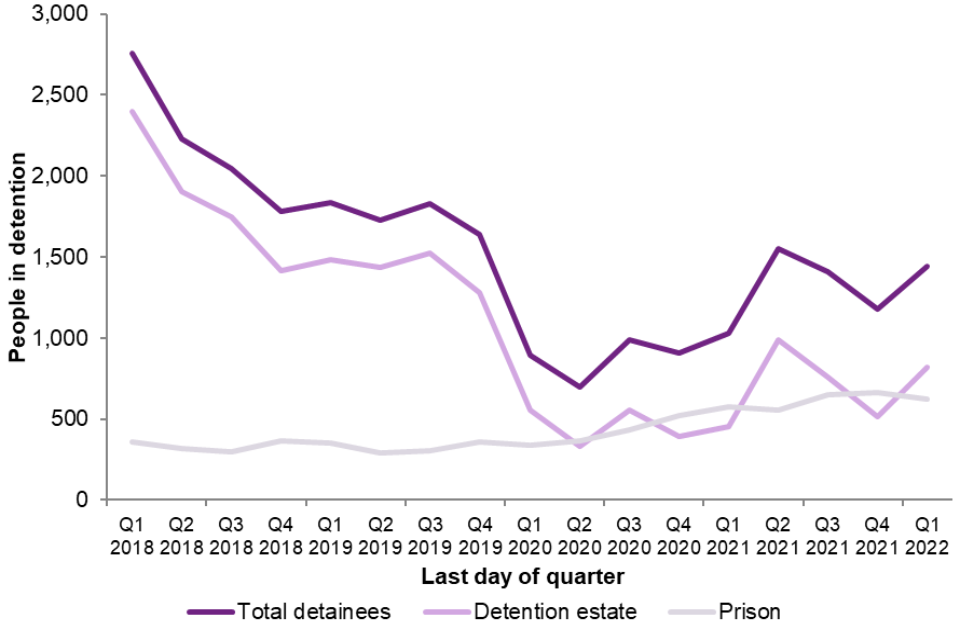

At the end of March 2022, there were 1,440 people in immigration detention (including those detained under immigration powers in prison), more than double at the end of June 2020 (698) when the impact of the pandemic was most pronounced, but 12% fewer than pre-pandemic levels at the end of December 2019 (1,637).

Figure 2 shows the number detained in the detention estate fell immediately following the pandemic and has remained below pre-pandemic levels since (819 at the end of March 2022 compared with 1,278 at end of December 2019, before the pandemic). The number of people detained in prisons under immigration powers increased by 73% from 359 before the pandemic at the end of December 2019 to 621 at the end of March 2022. This may reflect difficulties in securing returns due to the global travel restrictions caused by the pandemic, as well as challenges around releasing some foreign national offenders (FNOs) into the community.

The number of people in detention relate to a specific point in time and are subject to daily fluctuations. For example, if there were a large number of clandestine arrivals who had to be brought into detention just before the end of the period, the number of people in detention may be higher than if the same arrivals occurred several weeks before the end of the period or a few days later.

Figure 2: People detained under immigration powers in the UK, by place of detention, as at the last day of the quarter, 2018 Q1 to 2022 Q11,2

Source: Immigration detention - Det_D02

Notes:

- The ‘detention estate’ comprises Immigration Removal Centers (IRC), Short Term Holding Facilities (STHF) and Pre-departure Accommodation (PDA). It excludes those who are detained under Immigration powers in prisons.

- 2019 Q4 is the last data point before the pandemic with 2020 Q1 being immediately following the first UK lockdown.

1.3 People leaving immigration detention

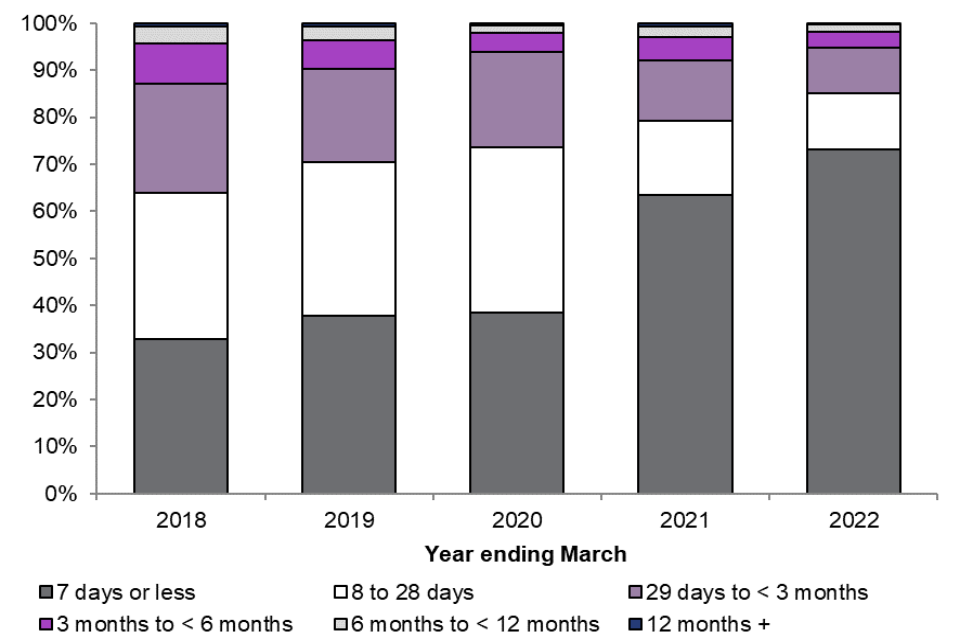

Figure 3 shows that an increasing proportion of people who were detained spent short periods in detention, with almost three quarters (73%) of those who left detention in the year ending March 2022 detained for seven days or less. This is a higher proportion than the 63% in the year ending March 2021 and the 39% in the year ending March 2020. The change is in part due to an increasing proportion of detainees being detained for short periods on arrival to the UK before being bailed (85% of those leaving detention in the year ending March 2022 were bailed) with the most common reason being an asylum (or other) application being raised. Combined with falling returns, this has led to a fall in the proportion of detainees being returned from detention; 14% (3,447) in the year ending March 2022, down from 35% (8,327) in the year ending March 2020 and 64% (16,577) in 2010.

Figure 3: People leaving immigration detention, by length of detention1,2, year ending March 2018 to year ending March 2022

Source: Immigration detention - Det_D03

Notes:

- Data from July 2017 includes those leaving detention through HM Prisons. Data are not directly comparable with previous years. See the user guide for more details.

- ’ < ‘ means ‘less than’.

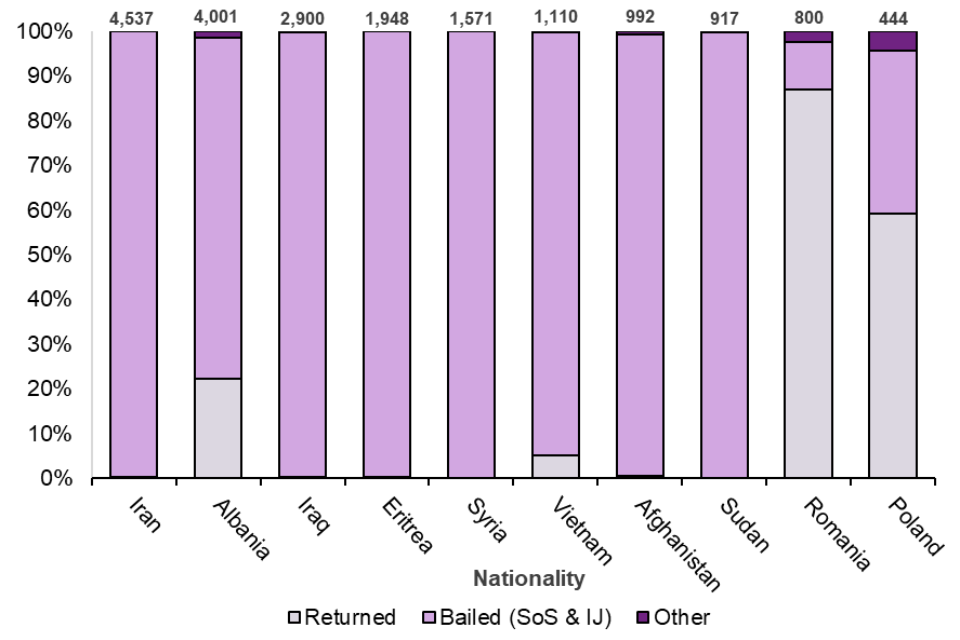

Figure 4 shows that among the top 10 nationalities leaving detention in the year ending March 2022, the majority were bailed. Of the top 10, only Albanian, Romanian and Polish nationals saw notable numbers of returns.

Figure 4: Top 10 nationalities leaving detention by reason for leaving1,2, year ending March 2022

Source: Immigration detention - Det_D03

Notes:

- Bailed (SOS & IJ) Secretary of State & Immigration Judge.

- Other reasons for leaving detention include being sectioned under the Mental Health Act, entering criminal detention, being granted leave to enter or remain in the UK, and detained in error. See the user guide for more details.

2. Returns

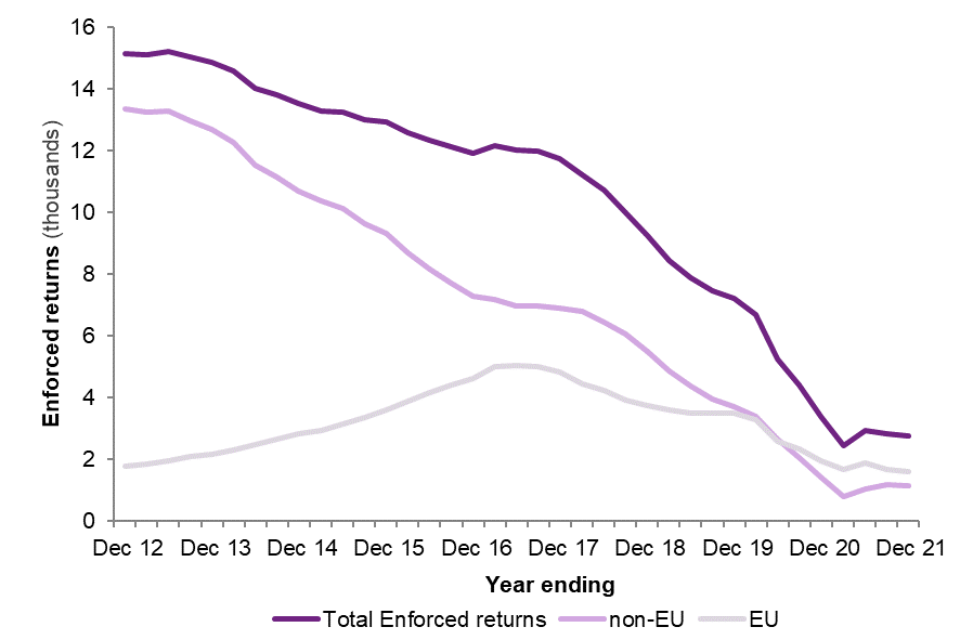

In 2021, enforced returns from the UK decreased to 2,761, 18% fewer than the previous year and 62% fewer than in 2019. The vast majority of enforced returns in the latest year were of Foreign National Offenders (FNOs) and a majority were EU nationals.

Enforced returns have been declining since the peak in 2012 with the recent sharp fall related to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, as Figure 5 shows. The number of enforced returns were very low during quarters that coincided with lockdowns starting in late March 2020 and early January 2021 (362 and 429). Numbers have increased to around 780 per quarter, however this is still below pre-pandemic levels in 2019 (which saw around 1,800 returns per quarter).

In 2021, there were 6,747 voluntary returns. Voluntary returns are showing signs of recovery following the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, being 36% higher than in 2020. However, the figures are 46% lower compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019, continuing a downward trend since 2015.

There were 18,416 passengers who were refused entry at port and subsequently departed (‘port returns’) in 2021, an increase of 82% compared with the previous year (10,127). The number of port returns in 2020 Q2 fell significantly as very few passengers arrived in the UK immediately following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of port returns has increased as more passengers began to arrive to the UK, with levels now similar to those pre-pandemic in 2019 (18,464).

Although port returns are now at a similar level to 2019, the nationality make up has changed. Prior to leaving the EU, port returns of EU nationals in 2020 accounted for 17% of all port returns; however, they now account for 68%. This change is due to an increase in the number of port returns of EU nationals as well as a decrease in non-EU nationals which fell during the pandemic and remain below pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 5: Returns from the UK, by type of return1, 2012 to 2021

Source: Returns - Ret_D01

Notes:

- ‘Voluntary returns’ include ‘other verified returns’ which are subject to upward revision (particularly for the last 12 months) as in some cases it can take time to identify people who have left the UK without informing the Home Office.

The longer-term fall in returns is due to a number of factors, including tighter screening of passengers prior to travel and changes in visa processes and regimes. The majority of enforced returns occur from detention. As reported in ‘Issues raised by people facing return in immigration detention’, (Home Office, 2021), 73% of people detained within the UK following immigration offences in 2019 were recorded as having raised one or more ‘issues’ that may have prevented their return. These issues could include an asylum claim, legal challenge, or a claim to be a potential victim of modern slavery or human trafficking. This proportion was up from 63% of detainees in 2017.

Figure 6 shows that between 2016 and 2019, enforced returns of both EU and non-EU nationals were declining (continuing a longer declining trend for non-EU nationals since 2012). Enforced returns of both EU and non-EU nationals continued to fall following the COVID-19 pandemic, with returns of non-EU nationals falling below the number of EU national returns.

Figure 6: Enforced returns from the UK, for EU and non-EU nationals, 2012 to 2021

Source: Returns - Ret_D01

The top four nationalities were all European (three from the EU) and accounted for around two thirds of enforced returns in 2021 – these were nationals of Albania (25%), Romania (24%), Poland (10%), and Lithuania (9%).

All four of these nationalities, and the vast majority of other nationalities, saw decreases in enforced returns in 2021, compared with pre-pandemic in 2019.

2.1 Returns of foreign national offenders (FNOs)

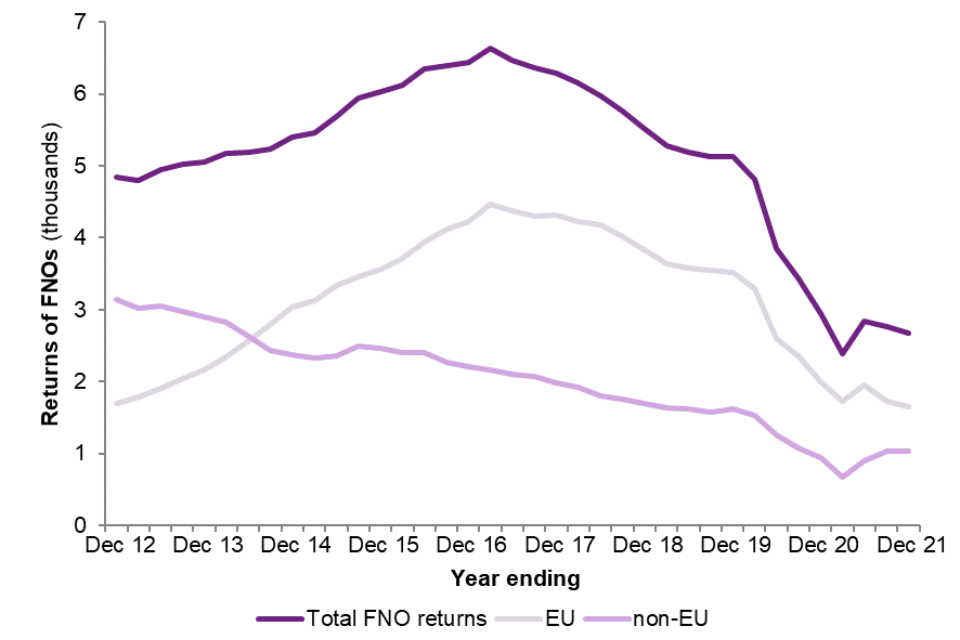

In 2021, there were 2,673 FNOs returned from the UK, of which 61% were EU nationals (1,642) and 39% were non-EU nationals (1,031). FNO figures are a subset of the total returns figures and in 2021 constitute the vast majority of total enforced returns and 28% of enforced and voluntary returns combined.

This figure of 2,673 FNO returns is 9% lower than in 2020 and 48% lower than in 2019, before the pandemic began. Figure 7 shows that FNO returns have shown an overall downward trend since 2016, following a steady increase before this due to more FNOs from the EU being returned in that period.

Figure 7: Returns of FNOs1 from the UK, for EU and non-EU nationals, 2012 to 2021

Source: Returns - Ret_D03

Notes:

- An FNO is someone who is not a British citizen and is, or was, convicted in the UK of any criminal offence, or convicted abroad for a serious criminal offence.

2.2 Asylum related returns

Asylum related returns accounted for only 3% of total returns in 2021.

In 2021, there were 806 returns of people who had previously claimed asylum in the UK (see section 3.2 below for the definition of an asylum-related return). This is 49% fewer than in the previous year (1,587) and 76% fewer than prior to the pandemic in 2019 (3,332). This continues a downward trend since 2010, when there were 10,663 asylum-related returns. This sharp fall over the decade differs from non-asylum related returns, which were relatively stable until 2016, declined until 2020 and have risen in 2021.

3. About the statistics

3.1 Immigration detention

The statistics in this section show the number of entries into, and departures from, detention for those held solely under immigration powers. One individual may enter or leave detention multiple times in a given period and will therefore have been counted multiple times in the statistics. Statistics on foreign nationals held in prison for criminal offences are published by the Ministry of Justice in ‘Offender management statistics quarterly’.

The detention estate comprises immigration removal centres (IRC), short-term holding facilities (STHF) and pre-departure accommodation (PDA).

Data on those entering detention, by place of detention, relate to the place of initial detention. An individual who moves from one part of the detention estate to another will not have been counted as entering any subsequent place of detention. The data, therefore, do not show the total number of people who entered each part of the detention estate.

Data on those in detention relate to those in detention on the last day of the quarter. It is therefore subject to daily fluctuations and can depend on how many people entered detention just before the end of the period.

Data on those leaving detention, by place of detention, relate to the place of detention immediately prior to being released. An individual who moves from one part of the detention estate to another has not been counted as leaving each part of the detention estate. The data, therefore, do not show the total number of people who left each part of the detention estate.

From July 2017, data on detention of immigration detainees in prisons are included in the immigration detention figures. Previously, individuals who were detained in prison would have been recorded in the data upon entering the detention estate through an IRC, STHF or PDA; now they are recorded upon entering immigration detention within prison. As a result, the length of detention of those entering prison prior to July 2017 will be recorded from the point at which they entered an IRC, STHF or PDA. Time spent in prison under immigration powers prior to entering an IRC, STHF or PDA is not included in the length of detention figures prior to July 2017.

For those entering detention from July 2017, the length of detention will include time spent in prison under immigration powers prior to entering an IRC, STHF or PDA. Data from 2017 Q3 onwards are therefore not directly comparable with earlier data. Further details of these changes can be found in the user guide.

Following the introduction of the new Immigration Bail in Schedule 10 of the Immigration Bill 2016, the reason for leaving detention ‘Bailed (SoS)’ replaced the existing powers of ‘granted temporary admission/release’ from 15 January 2018, and ‘Bailed (Immigration Judge)’ replaced Bailed’ to differentiate from ‘Bailed (SoS)’. See the user guide for more details of this change.

Data on the number of children entering detention is subject to change. This will be a result of further evidence of an individual’s age coming to light, such as an age assessment.

Data on deaths in detention include any death of an individual while detained under immigration powers in an IRC, STHF, PDA, under escort, or after leaving detention if the death was as a result of an incident occurring while detained or where there is some credible information that the death might have resulted from their period of detention and the Home Office has been informed. The annual data for 2020 are included in table Det_05b in the Detention summary tables. Further details can be found in the user guide.

3.2 Returns

Data on returns are published a quarter behind to allow more time for returns (particularly ‘other verified returns’) to be entered on the system prior to publication, ensuring that the published data is an accurate representation of the number of returns. We routinely revise the previous eight quarters of data as part of each quarterly release. Therefore, data for the most recent 8 quarters should be considered provisional. Further details on the revisions can be found in the returns section of the user guide.

The statistics in this section show the number of returns from the UK. One individual may have been returned more than once in a given period and, if that was the case, would be counted more than once in the statistics.

The Home Office seeks to return people who do not have a legal right to stay in the UK. This includes people who:

-

enter, or attempt to enter, the UK illegally (including people entering clandestinely and by means of deception on entry)

-

are subject to deportation action; for example, due to a serious criminal conviction

-

overstay their period of legal right to remain in the UK

-

breach their conditions of leave

-

have been refused asylum

The term ‘deportations’ refers to a legally-defined subset of returns, which are enforced either following a criminal conviction, or when it is judged that a person’s removal from the UK is conducive to the public good. The published statistics refer to enforced returns which include deportations, as well as cases where a person has breached UK immigration laws, and those removed under other administrative and illegal entry powers that have declined to leave voluntarily. Figures on deportations, which are a subset of enforced returns, are not separately available.

Data on voluntary returns are subject to upward revision, so comparisons over time should be made with caution. In some cases, individuals who have been told to leave the UK will not notify the Home Office of their departure from the UK. In such cases, it can take some time for the Home Office to become aware of such a departure and update the system. As a result, data for more recent periods will initially undercount the total number of returns. ‘Other verified returns’ are particularly affected by this.

Asylum-related returns relate to cases where there has been an asylum claim at some stage prior to the return. This will include asylum seekers whose asylum claims have been refused and who have exhausted any rights of appeal, those returned under third-country provisions, as well as those granted asylum/protection but removed for other reasons (such as criminality).

Data on the number of people returned from the UK from detention in the ‘immigration detention’ tables include those who were refused entry at port in the UK who were subsequently detained and then departed the UK. Data on those returned from detention in the ‘returns’ tables do not include those refused entry at port, and so figures will be lower.

Prior to the UK leaving the EU, certain individuals applying for international protection (asylum) could be returned from the UK to the relevant EU member state that was deemed responsible for examining the application, under the Dublin Regulation. Data on returns, and requests for transfer out of the UK under the Dublin Regulation, by article and country of transfer, are available from the Asylum data tables. Strengthened inadmissibility rules came into effect on 1 January 2021, following the UK’s departure from the EU. Data on cases dealt with under the inadmissibility rules, for January 2021 to March 2022, can be found in the How many people do we grant asylum or protection to? section. Further details on the Dublin Regulation and inadmissibility rules are set out in the user guide.

EU nationals may be returned for abusing or not exercising Treaty rights, or deported on public policy grounds (such as criminality).

Eurostat publishes a range of enforcement data from EU member states. These data can be used to make international comparisons.

3.3 Windrush Scheme

The Windrush generation refers to people from Caribbean countries who were invited by the British government between 1948 and 1971 to migrate to the UK as it faced a labour shortage due to the destruction caused by World War II. Not all of these migrants have documentation confirming their immigration status and, therefore, some may have been dealt with under immigration powers.

Data relating to the Windrush compensation scheme are published as part of the Home Office Transparency data.

4. Data tables

Data referred to here can be found in the following tables:

We welcome your feedback

If you have any comments or suggestions for the development of this report, please provide feedback by emailing MigrationStatsEnquiries@homeoffice.gov.uk. Please include the words ‘PUBLICATION FEEDBACK’ in the subject of your email.

We’re always looking to improve the accessibility of our documents. If you find any problems or have any feedback relating to accessibility, please email us.

See section 7 of the ‘About this release’ section for more details.