Making the law easier for users: the role of statutes

Richard Heaton gave a talk at the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies on common law and statute law.

There is an ambition, expressed variously throughout history, for all our laws to be written down, in one place, with clarity and elegance. What could be better than that?

I want to explore that ideal and ask: is that still our ambition? Should it be? And if for whatever reason we decide to settle for less, for a piecemeal, uncodified law: what does that mean for the user? And what can we do, all of us, to make sense of the hybrid, piecemeal law which is our inheritance?

To start, I could go immediately to Justinian, or to Napoleon – and I will mention those excellent emperors later. But because we’re at the University of London, and because this is his part of town, I want to start instead with Jeremy Bentham.

Bentham’s passion for codification

Bentham wasn’t a great fan of the common law and its judge-made tradition. Dog law, he called it:

It is the … judges …. that make the common law. Do you know how they make it? Just as a man makes laws for his dog. When your dog does anything you want to break him of, you wait till he does it, and then beat him for it.

This is the way you make laws for your dog: and this is the way the judges make law for you and me. They won’t tell a man beforehand what it is he should not do … they lie by till he has done something which they say he should not have done, and then they hang him for it. (Jeremy Bentham ‘Truth versus Ashurst’ 1792)

Let’s look a bit more closely at what Bentham was calling for. What would Bentham’s legal world look like?

He wrote that he would like to see common law turned into statute. And then what applies to everyone should be put into “one great book” – rather engagingly he added as an aside that, “(it need not be a very great one)”. And law that applies only to certain categories of people should be put into, “so many little books, so that every man should have what belongs to him apart, without being loaded with what does not belong to him”.

Reading Bentham, you are fired up by this wonderful longing for an ideal of statute law: law that gives the subject certainty, in advance, about the consequences of their actions. Bentham’s view was that this kind of law was more principled than, and ought to be desired, valued and respected above, “dog-law”.

Now, dog-law is an amusing 18th century caricature, but there is something about Bentham and his passion for codification that has fed directly into the guiding principles of modern drafters of statute law: the principles of certainty, and clarity, and making law accessible to all. It is still a rallying cry.

But let’s pause, and ask ourselves how far we have got, in this country, towards the Benthamite ideal?

We retain, two centuries after he wrote, a vibrant source of judge-made law, sitting alongside a vast stock of statute law, to which we add, each year, perhaps half a million words. In truth, England and Wales is a hybrid jurisdiction – as, I might add, is Scotland. We still look to the judges to develop some or all of the rules of contract, and tort, and remedies, and legal personality, and what it means to hold property on trust, and public law, and much more. Then there are some areas of law which are almost entirely statutory.

Replacing common law

And for the most part, we have areas of law where statute sits on top of or alongside common law. Drafters and legally trained readers are used to the mental to and fro this requires. Take the Defamation Act 2013, for example. Section 1 says, “A statement is not defamatory unless its publication has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the reputation of the claimant.” (Defamation Act 2013 s.1(1))

In order to understand that, you have to know what it means for a statement to be defamatory, and the significance of that. So while the zeal to simplify remains inspiring, the truth is that the idea of replacing the entire common law with a statutory code – and implicitly with a different judicial tradition – has not been taken up. We have neither replaced the common law altogether; nor, where we have replaced it, have we removed the judges’ responsibility for interpreting statutes and, where necessary, for developing the law.

So, why did this mission fail? Was Bentham right to put statute law on a pedestal? Can we do without dog-law and should we be trying to?

(At this point, the room was asked whether they favoured replacing the common law of contract and tort with a statutory code. The overwhelming majority of the room were against.)

You can look at the question of statutory constitution in a vacuum – in an imaginary country with a blank constitution. But I will try to answer it from where we all stand in our democracy, with our mixture of case law and statutes. Is Bentham’s ideal realisable? Not in this country, I think. I will give you three reasons. The first is simply that it takes a very large amount of time and effort.

Exercises in codification

Exercises in codification, or even simply consolidation or restatement, have tended to take years and years. The Law Commission commissioned a Contract Code; work carried on from 1966 to 1972 but the fruits of that labour were only published in 1993 – and then in Italy. (Harvey McGregor ‘Contract Code drawn up on behalf of the English Law Commission’ Milan – Giuffre Editore 1993)

Or take the Tax Law Rewrite Project. Its remit was to restate tax law so it fell short of a codification but still was similar enough to be a useful illustration of the scale that a codification project can assume. It ran from 1996 to 2007, involved tax officials and drafters and consultative committees, at a cost of a few million pounds a year. It certainly re-wrote some parts of the tax code and it was a brilliant test-bed for innovative drafting techniques. But codifying is long, hard work.

That takes me on to the second reason: democracy. Codification requires someone to step into the judges’ shoes as lawmaker – on a very large scale. That person, in our system, would of course be Parliament. So how would Parliament go about this task? What would it need to do the job? None of us, I think, would much like the idea of Parliament being asked to rubber-stamp a comprehensive new law of the land. So we would want the lawmaker to play an active part; and surely the public too; but is that realistic, and how would progress be made?

And note that we would be asking lawmakers to bring great and conscientious scrutiny to a project which would essentially be restating rather than changing the law. For the most part, that’s not how lawmakers would see their role: Parliamentarians, whether on the government front bench or elsewhere, are generally in politics to reform the law, not to restate it.

So, what if the Benthamite project sets out not just to restate the law, but to improve it? To change it at the margins, or to adjust some of the balances that it strikes between competing interests? In our pluralist democracy, there’s no area of law that would not be contested vigorously. It is easy to imagine the scale of the Parliamentary attention required to enact a Benthamite code. And if that time and attention were not forthcoming – if Parliamentary engagement could somehow be avoided – well, we should all be a bit worried for our democracy.

Remember, the best examples of a comprehensive code getting off the ground tend not to be in democracies. Take the code of Roman law. It was produced by Tribonian, an official under the Emperor Justinian. He codified three centuries of imperial judgements, reducing the volume of the law by 95%. And its descendant was of course the Napoleonic Code – another grand project enjoying imperial patronage and unencumbered by a lively democracy.

We have touched on resources and democracy. And so I come to the third reason why I suspect Benthamite codification is not realisable here. In the areas left to the common and uncodified law, we are probably quite well served by the tradition of judicial precedent as it has evolved. And if we were to codify, we would be losing a subtle ability for the law to adapt to changing circumstances.

Because a codifier approaching an area of common law, with perhaps a century of accumulated case-law, has a number of options:

- You can legislate in principle. This might be hugely attractive in some areas: and it holds the prospect of the law reducing in size and increasing in intelligibility. But you need to have a clear idea of who’s responsible for filling in the detail: the judges? Or a subordinate lawmaker? Or the administration? Or the academy? And you should work out what you lose by reducing certainty. Who will lose out? What will it cost them?

- Or you can either legislate to capture all the decided detail. In which case, you have frozen the development of the law in a particular time and place. This is a particular danger in a field of common law that is not well developed. What if the law of negligence had been codified before, say, contributory negligence had arrived? Or take “legitimate expectation” in public law: what if Parliament had tried to codify it in 2005?

- Or you can try and anticipate all future factual circumstances, and provide the definitive answer to each of them. In which case, you have a very considerable task on your hands – and you might reflect that the common law’s habit of deciding the law case-by-case, and not biting off more than it can chew, is quite sensible.

The common law operates by mapping out rules ever more precisely, on the facts of particular cases as they arise. Statute has to accommodate the hard cases by predicting them and providing for them in advance. It is why statute law can be so hard and gruelling to make and one reason why it ends up so complex.

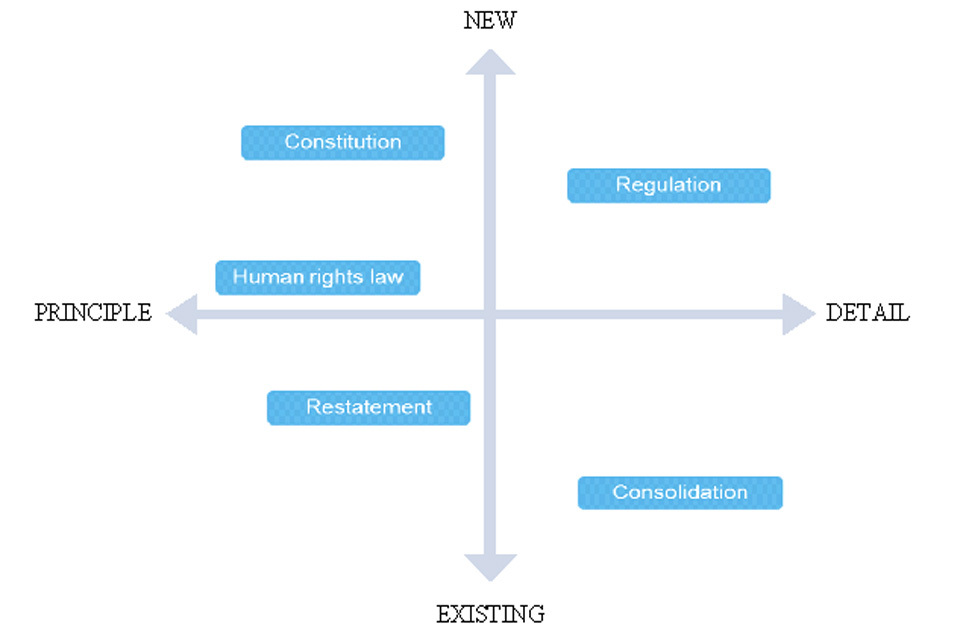

Let me illustrate this with a simple 2 x 2, and imagine plotting grand legislative projects onto it. A codifying impulse might start in the bottom left: to restate the law in principle.

Illustration to show why statute law can be complex

But there is a drive to capture points that are already to be found in existing case-law or regulation, which pushes the exercise to the bottom right. And then there may be a desire to fill in gaps, or close loopholes; and the project migrates to the top right quadrant, which is where dense new regulation is to be found. In the top left, incidentally, we might find the constitution of a new nation: bold, declaratory and containing principles rather than details. We rarely find ourselves legislating in this quadrant, though perhaps the Human Rights Act is an example.

That is not to say that common law can never be codified. Plenty of statutes replace bits of common law with a statutory restatement. The Companies Act 2006 did this for directors’ duties, for example. Other statutes simply abolish parts of judge-made law, such as particular common law offences or defences.

And sometimes the common law has got into such a state that a statutory new broom is required – and the Law Commission are experts in that particular type of legislative intervention. I might also add that codifications bringing clarity to whole sections of the law are tremendous, and notable, achievements. But perhaps we can begin to see why the grand usurping of common law by statute hasn’t happened – either here or in the other common law countries. We have a hybrid system, and it looks like it will stay that way.

Good law should be accessible

I want to come back to that curious state of affairs in a while, but first let’s greet the user. You might find this a strange word to use in the context of law and law-making. After all, isn’t the point of law to allocate rights and responsibilities and to ensure justice? “User” sounds a bit modish, a bit consumerist.

Well, I make no apology for talking about the user, though I’d equally settle for ‘citizen’. Here’s why.

In Lord Bingham’s words, the rule of law requires that “the law must be accessible and so far as possible intelligible, clear and predictable”. For legislative drafters, and for the government’s online publishers, this is a fundamental part of our mission.

Because legislation must not just do the job in theory: it must work in practice. So writing it clearly, and publishing it in a way that is clear and helpful to the reader, is a vibrant responsibility. If people cannot understand what legislation requires them to do, that is simply not fair – and if they just ignore it, we are in a worse position than if we had never made law in the first place.

That is a not an abstract fear: many a regulator knows that there are areas of regulation that they struggle to enforce. Every business (especially every small business) has in the back of their mind the thought that there are probably statutory duties they don’t know about. And we can hardly claim to respect the rule of law if the citizen’s prevailing view of the law is that it is too difficult, too obscure, that it isn’t really for them.

The other reason for thinking hard about the user is that people are using legislation – reading, searching, accessing, downloading – in a way that has never happened before. Between 2 and 3 million people log on to the legislation.gov.uk website every month and there are getting on for half a billion page downloads a year. Those are our users; and those of us involved in law-making are publicly accountable in quite a new way.

So we take this seriously, and you might have heard me or one of my colleagues at Parliamentary Counsel or the National Archives or the Government Legal Service or indeed the government’s policy profession talk about ‘good law’.

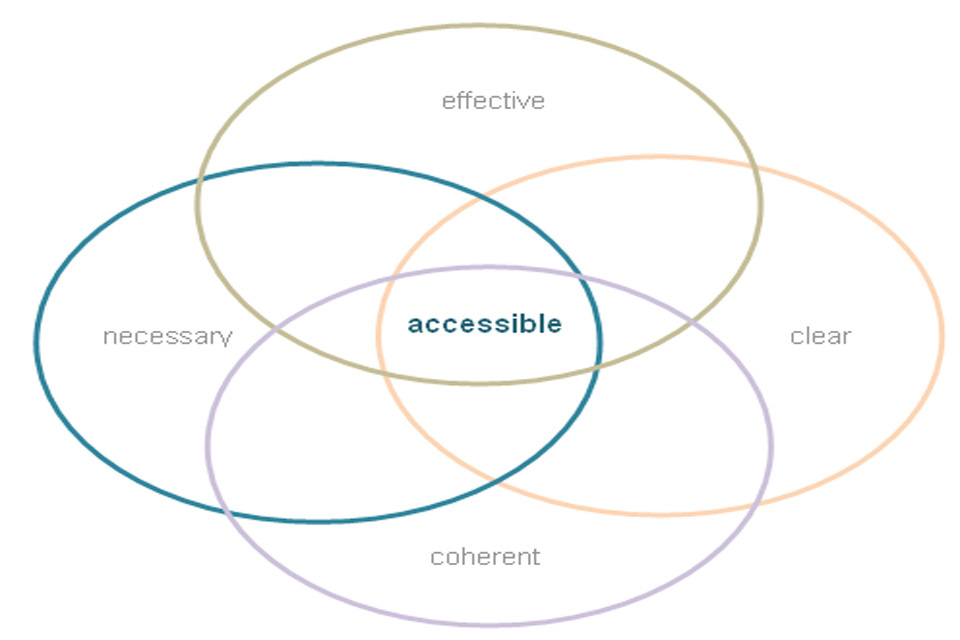

Diagram showing that good law should be accessible

It’s an appeal to everyone interested in the promoting and making and publishing of law to come together with a shared objective of making legislation work well for the users of today and tomorrow.

We think that good law is necessary, clear, coherent, effective and accessible. And broadly, it has taken us into four areas of work:

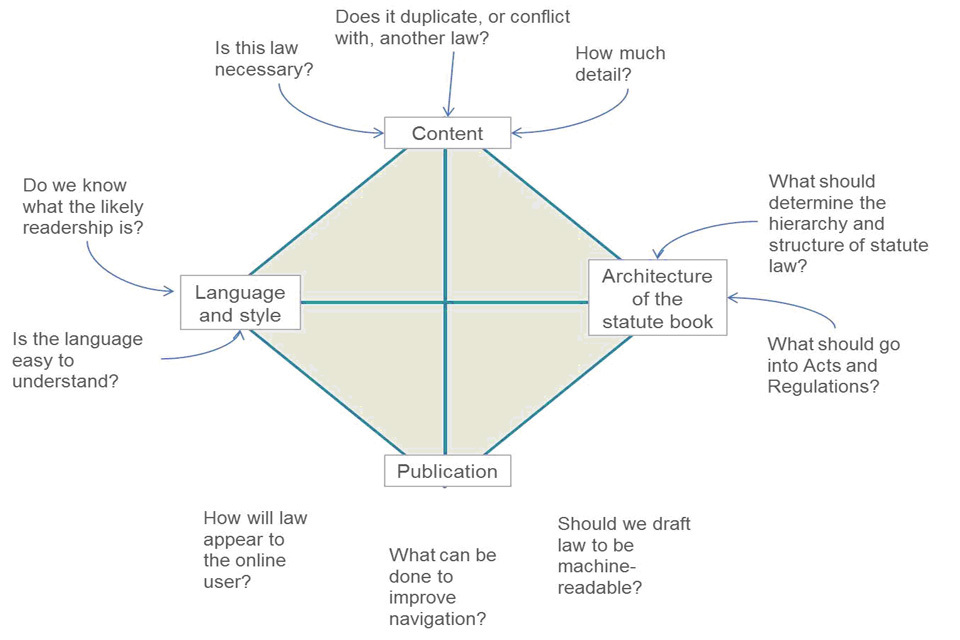

Diagram showing the four areas of work for good law

The content of law (how much law, how much detail, alternatives to legislation); drafting and language; the way in which law is published and presented to readers; and the architecture of the statute book itself.

What are we doing to get there? Well for one thing, we are finding things out about our audience – who they are and why they read legislation: Non-lawyers using it for work; members of the public worried about their rights; lawyers and law librarians. We are finding out what they find difficult about legislation. We are looking at what we can do in response.

We know that finding legislation in an up-to-date version is a particular problem; the National Archives with the help of expert participation from the commercial law publishers are within reach of a perpetually up-to-date legislation.gov.uk.

And we are working on a single web-based software platform so that drafters and publishers (and potentially readers) all use the same open source tools and the same legislative database. For all sorts of reasons, that has not been the case to date; if we achieve it, I think it will transform the usability of statute law.

Common law fused with statute law

But let’s go back to our inheritance of common law fused with statute law. Even if we are content to stick with our mixture of judge-made law and legislation, and I don’t think we need to be too apologetic about it, let’s ask what this hybrid system looks like for the user.

Well, the poor reader is perhaps rather like someone who sets sail in a boat. He has been handed some nautical charts which seem to map out most of the route (though they’re rather heavily amended). But he’s also been told that some rocks (he’s not sure which) aren’t marked on the charts. However, he’s given some data about shipwrecks, and perhaps he’ll be able to work out the rest from that. Immediately, the charts are unreliable; and as for the data, well where to start?

Now of course, you might say, it’s not as bad as all that. We are talking about the raw material of law. What the citizen needs (you might say) is help not with the raw material but with a distillation of law as it applies to that particular person or situation. Or practical help and advice. Or clear communications from regulators and law enforcement agencies about what is needed to comply and what the penalties for non-compliance are.

And I buy all that – up to a point. But three comments: first, I do not think we should assume that law must always require an intermediary. That seems too defeatist. Second, it’s the intermediaries who need help as much as anyone else. And third, whether we like it or not, people are looking at the law themselves – as I described earlier. We can’t ignore them: as public servants, we need to be where they are, and to see if we can help them.

Making judge-made law more accessible to the user is not an area where I can claim any professional expertise or competence. It clearly requires different techniques to the ones we are adopting on the statutory side. Organisations like Law for All, and BAILII, and the law reporters, and commercial publishers: they all do good work in bringing case law to the public. There’s a wealth of subscription services and digests available. And it’s not the job of Parliamentary Counsel of all people to wade in here.

But I’m interested in one aspect: the ghostly absence of case law to a reader of statute law. How does the reader even know that the common law is there? Should we do anything to convey the totality of the law to that reader? Or, to put it another way, in our information age, do we need to re-think how the law is presented to citizens? This, I feel, is a challenge both for government and for civil society more generally.

Government’s role

So, what can we do, in government? Should we publish authoritative statements of the common law? Clearly not: the nature of common law means that this would be impossible. And anyway, there’s a constitutional barrier: as every government lawyer knows from their first week at work, no minister or civil servant can offer an authoritative statement of the law: that is something only a judge can do.

But ok, says the user, this is getting interesting. “Government is offering me a definitive, up to date account of something that looks like law. But at the same time, government says it cannot do the same for other parts of the law; indeed, it says it’s not allowed to do that”. Now, this is an inconsistency we can all explain, as I have tried to do – but it’s something we should be mindful of. After all, for the user, law is law is law. And clear and accessible law is not a principle that should bend with the distinction between one type of law and another.

So let’s return to our dilemma. What can the law drafter do, to help the wider picture? Here are some techniques we can use. One is to use the language of the statute itself, to alert the reader to the presence of common law beyond the page. The drafter is generally cautious here: the instinct is not to add words that are merely explanatory, because legislation is supposed to enact law. Providing a précis of some part of the common law carries risk. What if it’s an incorrect précis? Could it inadvertently change the law? What if the common law changes? But that is one tool.

Where the statute is changing the common law in some way, or trying to influence its development, there’s more scope for explanatory words explaining what you’re trying to do. Here’s an example of statute using common law language to help the reader understand what’s going on. It’s from the Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013:

- (2) The following do not apply in relation to a new trust –

a) the first part of the rule known as the rule in Howe v. Earl of Dartmouth (which requires certain residuary personal estate to be sold)

b) the second part of that rule (which withholds from a life tenant income arising from certain investments and compensates the life tenant with payments of interest)

c) the rule known as the rule in Re Earl of Chesterfield’s Trusts (which requires the proceeds of the conversion of certain investments to be apportioned between capital and income)

d) the rule known as the rule in Allhusen v. Whittell (which requires a contribution to be made from income for the purpose of paying a deceased person’s debts, legacies and annuities) (Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013 s. 1 (2))

The next tool is the use of explanatory material, lying outside the statute itself. Explanatory notes that departments publish alongside Bills are widely used by Parliamentarians (a small but important readership I’ve not yet mentioned).

We think that advocates and judges use them as well, if a case turns on the intention behind a new piece of legislation. We know that explanatory notes are of varying quality, and we are about to conclude a review of their style and content and format. Showing the reader the legal, and indeed the political, context for the new law is certainly something these documents can help with.

Bringing law to citizens

Is there a role for editorial content on legislation.gov.uk? After all, this is becoming the key portal for citizens accessing the law. But it’s principally a site for publishing authoritative texts, not a site for legal commentary. Perhaps the biggest contribution it can make to the wider “whole law” picture is that all its legislative data will not only be complete and up to date but also open source and available. In that way, anyone looking to provide a complete guide to any area of the law will be able to incorporate legislation data into commentary and editorial.

And just as legislation can be seen as a dataset that can be arranged to meet a user’s needs, so can the body of case-law. It’s an aspiration of the legislation.gov.uk team to be able to mash the legislation database with the law report database, so that the reader will at least be alerted to those words and phrases that have been discussed in case law. In the same way, HMRC are looking at how GOV.UK can help the reader step from the massive suite of tax guidance (80,000 pieces) to the relevant legislation, and back again.

One of the other features of the information age is the power of aggregated data combined with patterns of usage. If the publishers of legislation.gov.uk know what people have looked at after they’ve looked at section 1 of the Defamation Act, would that be a useful thing to share with readers? Or should the site be designed not simply from Parliament’s point of view (i.e. in chronological order) but to fit better with known patterns of usage? If we are to succeed in making the law more accessible to users, these are sorts of ideas we need to be adopting.

I don’t pretend to have all the answers to the question of how we bring law to citizens. Still less does government have all the necessary levers at its disposal – for good constitutional reasons. So I will end with a challenge to everyone in the public realm, or in civil society, who in some way cares about the rule of law and about the citizen’s experience of law. What can be done – what can you do – to make law as a whole more accessible and clearer to the people it serves and protects?