Youth Employment Initiative – Impact Evaluation

Published 2 March 2022

DWP research report no. 1011

A report of research carried out by Ecorys UK on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2022

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence

Or write to the:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published March 2022

ISBN 978-1-78659-360-3

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Acknowledgements

This report was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The evaluation was part-funded by European Social Fund (ESF) technical assistance. We would like to thank Nicholas Campbell and Benjamin Ashton in DWP’s ESF Evaluation Team for their guidance and contributions throughout the project.

We would also like to thank all the staff and participants who gave up their time to take part in the study. Without them of course, the research would not have been possible.

Authors’ credits

This report was authored by Ian Atkinson and Matthew Cutmore of Ecorys UK. Ecorys UK are experienced in conducting research into European programmes aimed at supporting individuals into employment and bringing about social inclusion. They have contributed to a number of studies for the DWP, other UK Government Departments and the European Commission around these themes.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Counterfactual impact evaluation (CIE) | CIE is a type of impact evaluation using a counterfactual analysis approach. Counterfactual analysis compares the real observed outcomes of an intervention with the outcomes that would have been achieved had the intervention not been in place (the counterfactual). A CIE can involve use of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) methodology, also referred to as an ‘experiment’, or quasi-experimental methods that seek to mimic an experiment, often through construction of a comparison group to compare outcomes with the treatment group receiving an intervention. The CIE for the Youth Employment Initiative impact evaluation uses a quasi-experimental approach. |

| Difference in differences (DiD) | DiD analysis is an impact evaluation technique, seeking to estimate the effect of a treatment on an outcome of interest through assessing change over time in an outcome for a treatment group relative to the average change over time for a control/comparison group. |

| European Social Fund (ESF) | The ESF is the European Union’s (EUs) main financial instrument for supporting jobs, helping people get better jobs and ensuring fairer job opportunities for EU citizens. The European Commission works with countries to set the ESF’s priorities and determine how it spends its resources. |

| (ESF) Managing Authority (MA) | The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) assumes the role of the ESF Managing Authority for England. It has overall responsibility for administering and managing the ESF and reporting to the European Commission. |

| (ESF) Operational Programme (OP) | Operational Programmes describe the priorities for ESF activities and their objectives at national or regional levels within the European Union[footnote 1]. |

| Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) | LEPs are voluntary partnerships of local authorities and businesses with responsibility for deciding on general economic priorities at the local level. |

| European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) Sub-Committee | Each LEP area has a sub-committee that provides implementation advice to the Managing Authorities for the ESIF Growth Programme in England. Their role is to advise Managing Authorities on local growth conditions and priorities with regard to project call specifications, funding applications and implementation. |

| Monitoring Information (MI) | Data that is collected regularly by YEI providers following a set template. All data is forwarded to DWP, which collates and analyses the information. |

| Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics (NUTS) | NUTS areas are geographical territories identified through a standard developed and regulated by the EU in order to reference the sub-division of countries for statistical purposes. |

| Propensity score matching (PSM) | PSM is a statistical technique used to estimate the impact of an intervention on a set of specific outcomes. It mimics an experimental research design by comparing outcomes for a treatment group and a statistically generated comparison group, which is similar to the treatment group in its composition. |

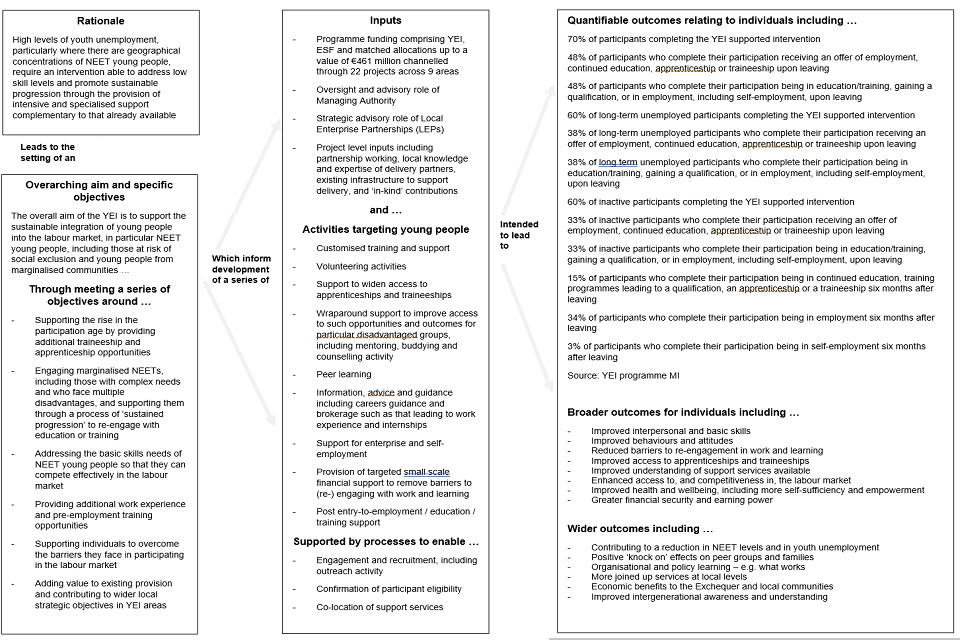

| Theory of change | Theory of change is an evaluation methodology drawing on work developed in the United States to evaluate community and social programmes. The approach involves identifying the logic behind an intervention in terms of its rationale and aim, key objectives, inputs, activities and short, medium and long term outcomes and testing this ‘intervention logic’ through a range of evaluative methods. |

Executive summary

Introduction

This summary presents the findings of an impact evaluation of the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI), undertaken by Ecorys. The YEI represents part of the European Commission’s (EC’s) policy response to the social and economic challenges stemming from the financial crisis of 2007-2008, and is implemented in England as part of the European Social Fund (ESF). The YEI impact evaluation commenced in April 2017 and ran until late 2019. It follows a previous process evaluation published by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) in 2017[footnote 2]. The impact evaluation focuses on examining the effectiveness, efficiency and impact of the YEI.

Methodology

A mixed-method approach was adopted to evaluate the effectiveness, efficiency and impact of the YEI. The findings presented below are drawn from:

- a desk-based review of YEI and related documentation

- secondary analysis of data, including YEI Management Information (MI), results from the separate ESF and YEI Leavers Survey commissioned by DWP, and additional statistical data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS)

- interviews with high-level stakeholders from the ESF Managing Authority (MA)

- primary research across 10 delivery areas, including interviews with YEI provider staff, European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) sub-committee representatives, and YEI participants

- a counterfactual impact evaluation (CIE) strand, comparing outcomes for YEI participants with a comparison group

The evaluation findings also include a cost-benefit analysis (CBA), undertaken by DWP analysts based on the results of the impact evaluation strand.

Key findings

Effectiveness

To date, the YEI has proved generally effective in terms of targeting participants, the delivery models developed to implement provision, and the delivery of provision itself. The programme is broadly on target in terms of anticipated engagement numbers and in respect of the anticipated gender split of participants. Key factors supporting effectiveness in targeting include: effective use of local data and intelligence; use of delivery partners’ existing networks; focusing extensively on outreach activity; developing partnerships with Jobcentre Plus to encourage referrals; and engaging in co-location with other services.

The delivery models developed also appear to be effective. Notable aspects to this include the use of ‘key worker’ roles to provide consistency and an overview of individuals’ support needs, the development of partnerships and referral routes to offer a wide-ranging support offer, and the establishment of effective governance procedures. The available evidence also suggests a positive picture of the effectiveness of YEI delivery itself in terms of the provision on offer and its implementation. The range of support available, and the extent it is tailored to individual needs, are key factors promoting effectiveness.

Several aspects of the YEI support offer consistently emerged as being effective and important. These included: ‘wraparound’ support designed to address individuals’ personal and often deep-seated challenges and barriers, commonly facilitated through a key worker role; short, sharp interventions to address a small employment need or gap in a young person’s CV; English and Mathematics provision, a lack of competence and qualifications in respect of which was seen as a key barrier to finding work; training linked to employment route-ways; and community-based activities and volunteering, such elements being key in reducing isolation and increasing confidence as part of moving towards employment.

While the majority of YEI delivery and provision can be assessed as effective, in particular contexts or for particular participants some elements appeared to be less so. For example, more structured provision in a classroom setting was cited as discouraging the engagement of young people in some cases, potentially due to prior negative experiences at school.

The positive overall impression of effectiveness was also apparent when considering the quality of the employment and training offers participants received. The YEI Leavers Survey provided the main evidence for this assessment. Nine in ten respondents accessing traineeships felt that their traineeship would improve their chances of getting a job. In terms of job offers, around half of the 45 per cent of respondents reporting that they were in work six-months after leaving the YEI were on a permanent employment contract and a further 14 per cent on a contract lasting 12 months or more. This suggests the majority of jobs gained by YEI leavers were fairly stable and long term. Finally, almost two-thirds of YEI leavers receiving job offers between starting on the programme and six months after leaving rated the quality of offers received as either ‘very good’ (27 per cent) or ‘good’ (35 per cent). Less than one in ten rated their offers as either ‘poor’ or very poor’.

Efficiency

The available evidence suggests that organisations delivering the YEI are concerned with ensuring efficiency and hence, ultimately, offering value-for-money. Common examples given by provider representatives of how they sought to ensure efficient delivery included: close control of staffing numbers; ensuring appropriate caseloads; focusing on staff progression, retention and training to reduce recruitment costs; reducing transaction costs between delivery partners; and reducing overheads where possible. Other examples included reducing costs through re-use and recycling, using account holder discounts when purchasing provision and courses, and avoiding overlaps or duplication with other provision available locally.

While the general impression was one of efficient delivery, there are limitations to assessing the efficiency of specific types of YEI provision and activities. There is a lack of data to facilitate such assessment, with providers not generally identifying costs and throughput of individual activities (in terms of numbers participating). In addition, it was evident that the inter-related nature of many YEI activities naturally makes such data gathering and assessment problematic.

Accepting these limitations, work around personal development, such as building confidence, was seen as intensive though ultimately cost-effective when balanced against the positive effects this was often seen as having for young people. Short courses leading to required qualifications were also cited from this perspective, in that a relatively small outlay could fill a gap in a CV and unlock opportunities.

The case study research was used to identify aspects that promoted or hindered efficiency. A focus on unit costs in developing provision was widely cited as a factor supporting efficiency. This was noted by provider representatives as resulting from DWP as the ESF MA requesting details of such costs in the application process. Effective partnership working and governance also evidently plays a key role in enhancing efficiency, whether through ensuring that the particular skills and organisational capacities can be efficiently deployed, or that performance can be managed by the lead partner to promote efficiency across delivery partnerships.

Impact

Evidence shows that the YEI is having a positive impact on the employment prospects of participants. Compared to a similar comparison group constructed from administrative data, results from the CIE show that, on average, YEI participants were in employment for an additional 56 days in the twelve months following support. Effects on likelihood of claiming benefits are less clear, with there being no statistically significant effect on the likelihood of claiming Jobseekers’ Allowance (JSA) or Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) following YEI support. As explained in the main report, it was not possible to provide estimates on the likelihood of claiming Universal Credit (UC) due to data limitations in the context of UC roll-out during the YEI’s delivery period.

At the overall programme level, a CBA based on the results of the CIE and conducted by DWP analysts estimates that while the programme has a social return in the range of £1.50 to £1.55 per £1 spent, the fiscal return is in the range of £0.13 to £0.17 per £1 spent[footnote 3]. It is acknowledged, however, that these are likely to be underestimates with the true value for money being higher.

The positive estimates of employment impacts generated by the CIE are mirrored by the evidence available from the MI data and ESF Leavers Survey. While the former shows that just under a third of participants are recorded as entering employment immediately on leaving the programme, on the basis of respondents’ self-reporting the Leavers Survey indicates that just under one in two are in employment six months after leaving. Taking account of the YEI client group, for whom the evidence indicates labour market disadvantage and multiple barriers to work are common, the mutually reinforcing evidence around employment impacts from the CIE, MI and survey data can be considered very positive.

The MI data also enables an assessment by gender and disadvantaged status, using the definitions of disadvantage given in the ESF guidance. The data shows little variation in employment outcomes by gender. However, positive employment outcomes are considerably lower for participants recorded as having an additional labour market disadvantage (in addition to being NEET), compared to those for whom a disadvantage is not recorded. Amongst those with a disadvantage, just over a quarter (26 per cent) were recorded as entering employment on leaving the YEI, with the equivalent figure for those with no disadvantage being just over a third (37 per cent).

Evidence of education and training impacts is also available from the MI data and the Leavers Survey. As at September 2019, the MI showed that just under one in five YEI leavers moved into education or training, with just under one in ten gaining a qualification on leaving. Similar evidence is available from the YEI Leavers Survey, with 16 per cent of respondents reporting that they were in education or training at the six-month point after leaving. When adding respondents in training or education six months after leaving to those reporting that they were in work at this point (45 per cent), the survey evidence presents a very positive impression of just under two-thirds of participants achieving positive destinations in the period after support. For a programme seeking to reduce numbers of young people not in employment, education or training (NEET), this is further evidence of the key aims of the YEI being met to a considerable extent.

As well as the ‘harder’ impacts evident from the YEI in terms of entry into work or learning, evidence suggests that the programme frequently has a wide range of beneficial ‘softer’ impacts, such as enhancing self-confidence. Consistent proportions of around four-fifths of respondents to the Leavers Survey, for example, reported that the YEI had helped with a range of such outcomes, including communication skills, self-confidence around work, ability to do things independently, motivation to find a job or do more training, and team working. Similarly, improved confidence, aspirations and motivation emerged as particularly strong and consistent themes in participants’ discussions of the impact of support during case study interviews.

A range of new or enhanced skills resulting from engagement with the YEI were also frequently cited by participants, including improved leadership skills, employability skills, skills around budgeting and managing finances, enterprise skills, and subject-based skills, including those related to Mathematics and English. The case study evidence also indicated that such softer outcomes are central to the achievement of broader YEI impacts, for example around reducing barriers to, and entering, work and learning. As such, they help explain, and reinforce, the positive impacts discussed above around levels of re-entry to employment and learning amongst the NEET young people supported through the YEI.

In addition to impacts on YEI participants, evidence indicates that the programme is having a number of broader impacts. The clearest and most consistent involve beneficial impacts for provider organisations. These include improved delivery systems and structures gained from insights from working with partners, enhanced ability in terms of delivering ESF-funded provision, and the development of new links and relationships with agencies and organisations working to support young people. Evidence around impacts on employers and local communities was more anecdotal and piecemeal, though still positive in cases where concrete examples were offered.

Finally, it was also evident that the experience of designing and delivering the YEI has generated broader ‘learning’ impacts. Typically, these were described in terms of helping to inform or crystallise policy insights, and/or as providing lessons for employability and skills initiatives targeted at young people. Specific examples included insights on the importance and frequent necessity of addressing mental health in the context of employability support, the need to focus more on young people further from the labour market as youth employment rates improve, and the potential gap that will be left following the end of the YEI, along with the implication that similar provision is likely to continue to be required in future.

Conclusion

Evidence across the different evaluation strands presents a positive impression of the effectiveness, efficiency and impacts generated by the YEI. This demonstrates that interventions of this type, specifically focused on targeting and supporting NEET young people, can be effective and lead to a range of positive outcomes. The support on offer is clearly welcomed by young people, with the flexibility and wraparound elements being central to participants’ engagement with the YEI and the positive results they gain from it.

Looking at the theory of change developed to structure the assessment of the programme, it is apparent that the majority of intended outcomes can be assessed as being achieved or exceeded. In particular, results in relation to the core aim of the programme, around supporting young people to (re-)enter employment, education or training, hence contributing to a reduction in NEET levels, can be viewed as very positive. In addition, evidence indicates that the YEI had a positive effect on many of the broader, intermediate outcomes likely to have contributed to these ultimate impacts, particularly in terms of enhanced confidence and interpersonal skills, alongside reduced labour market barriers. The relative success of the programme is also notable in light of the nature of the YEI client group, suggesting learning can usefully be drawn for future initiatives aimed at reducing NEET levels.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of an impact evaluation of the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI), undertaken by Ecorys on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The evaluation adopted a mixed-method approach, combining qualitative case study research with a counterfactual impact evaluation (CIE), supplemented by cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and examination of additional secondary data sources. This impact evaluation follows on from a previous process evaluation of the YEI, published by DWP in 2017. This introduction provides an overview of the YEI before briefly detailing the aims, objectives, and methodology for the evaluation. Subsequent chapters examine the range of evidence gathered to assess and make judgements on the YEI’s effectiveness, efficiency and impact respectively.

1.1. Youth Employment Initiative overview

The YEI forms part of the European Commission’s response to high levels of youth unemployment in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Designed to complement other national and ESF provision, the YEI provides support to those under the age of 25, or 29 in some cases, residing in European Union (EU) regions particularly affected by youth unemployment[footnote 4]. Reflecting this geographical targeting, 90 per cent of YEI funding is channelled to regions where the youth unemployment rate in 2012 was higher than 25 per cent, or where youth unemployment was more than 20 per cent but had increased by more than 30 per cent in 2012. YEI provision typically includes support to access apprenticeships, traineeships, job placements and further education, amongst other employability assistance combined with wrap-around support for participants.

As reflected in the ESF Operational Programme (OP) 2014-2020 for England, the overall objective of the YEI is to support the sustainable integration of young people into the labour market, in particular those not in employment, education or training including young people at risk of social exclusion and young people from marginalised communities. The specific objectives of the YEI are:

- “To support the rise in the participation age by providing additional traineeship and apprenticeship opportunities for 15-29 year old NEETs in YEI areas, with a particular focus on 15-19 year old NEETs.

- To engage marginalised 15-29 year old NEETs in YEI areas and support them to re-engage with education or training, with a particular focus on 15-19 year olds.

- To address the basic skills needs of 15-29 year old NEETs in YEI areas so that they can compete effectively in the labour market.

- To provide additional work experience and pre-employment training opportunities to 15-29 year old NEETs in YEI areas, with a particular focus on those aged over 18.

- To support 15-29 year old lone parents who are NEET in YEI areas to overcome the barriers they face in participating in the labour market (including childcare).[footnote 5]”

The OP emphasises that support for NEET young people is already available through a variety of other provision, and that the YEI should be additional and complementary to existing measures – for example, through providing more intensive support[footnote 6].

The YEI in England is being delivered through 24 projects spread across the areas eligible for funding under the initiative. The projects are led by a mixture of public, private and voluntary and community sector (VCS) organisations, with these lead organisations typically working with a range of delivery partners to support young people. As anticipated in the OP, YEI projects deliver a range of support to young people with the aim of assisting them into employment, education or training. This includes providing access to training and qualifications, volunteering activities, support to access apprenticeships, ‘wraparound’ support aimed at building confidence and softer skills required for employment, enhanced careers advice and guidance, and working with employers to broker work placements and facilitate employment opportunities for young people.

Further detail on the support offer and delivery models adopted by YEI providers can be found in the previous process evaluation of the initiative[footnote 7].

1.2. Evaluation aims and objectives

The overall purpose of the evaluation was to provide an assessment of effectiveness, efficiency and impact in respect of the YEI. Within this, three main aims of the evaluation were specified as follows:

- To assess the extent to which the YEI has achieved its objectives (Sustainable integration into the labour market of young people not in employment, education or training, including those at risk of social exclusion and young people from marginalised communities)

- To evaluate how efficient the YEI has been (in terms of achieving its objectives at the minimum cost and without duplicating existing provision) and which elements of the programme were most cost-effective

- To gather evidence on the impact of the YEI and the extent to which observed outcomes can be considered an effect of the programme.

More broadly, the evaluation also aimed to explore what works well or less well in supporting young people into quality and sustainable employment, education or training. Given the focus on assessing the YEI’s impact, the study also sought to identify the effect of the support given on generating the key intended results of the YEI, notably supporting individuals to enter employment, education or training, as well as on a series of ‘softer outcomes’. These include, for example, increased confidence, reduced barriers to engagement in work or learning, and improved wellbeing.

In line with the theory of change developed for the initiative in the context of the previous YEI process evaluation[footnote 8], the research also aimed to assess the YEI’s effect on some broader outcomes. These included outcomes for the organisations delivering the provision, effects on encouraging more joined-up services at local levels, and any impacts on local communities that could be discerned. A diagram summarising this theory of change is included at Appendix A for reference.

1.2.1. Research questions

The aims and focus of the evaluation outlined above are reflected in a series of research questions included in the specification for the study developed by DWP. These reflect the evaluation criteria of effectiveness, efficiency and impact as follows:

Effectiveness

- How and to what extent did YEI achieve its objective of sustainable integration of young people into the labour market?

- How and to what extent did YEI contribute to addressing the problem of NEETs?

- Were YEI funds spent on those most in need of support? Were the specific target groups reached as planned?

- Which types of interventions were the most effective, for which groups and in which contexts?

- Which kinds of support were applied to which sub-groups (e.g. young people leaving education without a qualification, unemployed graduates etc.)? Were they relevant to the specific needs of the participants?

- What does the evidence suggest about ‘what works’ to help disadvantaged groups move closer to the labour market?

- What was the quality of the offers received by the participants? (collected through the ESF and YEI Leavers Survey)[footnote 9]

- Were there any barriers to effective implementation of the YEI programme?

- Which projects displayed best practice and how can this be shared?

Efficiency

- What were the unit costs per type of operation and per target group?

- Which types of operations were the most efficient and cost-effective?

- What are the direct and indirect benefits and costs to projects? Individuals? Local stakeholders such as employers?

Impact

- What is the impact of the YEI support for young unemployed people on their future employment chances? How big is the effect of the YEI support on entering the labour market? What would have been individuals’ employment status in the absence of the support?

- What was the contribution of the YEI to changes in the youth employment/ unemployment/activity rates in the geographical areas covered by the YEI?

- Which specific elements of the intervention contributed to the impact observed?

- What were the unintended effects of the intervention (if any) and how significant were they?

- Were there any structural impacts (new partnerships between public/private/voluntary sectors, changes in education system, vocational training system, Public Employment Services)?

- Was YEI responsible for broader outcomes for individuals, including:

- improved interpersonal and basic skills

- improved attitudes and behaviours

- reduced barriers to re-engaging in work and learning

- improved access to apprenticeships and traineeships

- improved understanding of support services available

- enhanced access to and competitiveness in the labour market

- improved health and wellbeing including more self-sufficiency and empowerment

- greater financial security and earning power

- Did YEI lead to wider outcomes such as:

- Positive ‘knock-on effects’ on peer groups/families, such as improved attitudes or reduced barriers to re-engaging in work and learning

- Organisational and policy learning – e.g. ‘what works’

- Economic benefits to the Exchequer and local communities

- Improved inter-generational awareness/understanding

1.3. Evaluation methodology

In summary, the mixed-method approach to the evaluation encompassed:

- A desk-based review of YEI and related documentation

- Secondary analysis of YEI MI data[footnote 10] and additional contextual statistical data (e.g. that available from the Office for National Statistics (ONS))

- Secondary analysis of data from the ESF and YEI Leavers Survey

- Six interviews with high level stakeholders, principally from the ESF Managing Authority (MA), to explore and understand the programme context

- Primary, case-study based, qualitative research across 10 YEI delivery areas conducted in late 2017 (including c.10 interviews in each area with a range of stakeholders including YEI lead provider staff, YEI delivery partner staff, YEI participants, and European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) sub-committee representatives)

- A CIE, comparing outcomes for the YEI treatment group to a statistically generated comparison group, using propensity score matching and difference-in-difference techniques drawing on YEI MI and administrative datasets.

- A CBA estimating the return on investment offered by the YEI, informed by the results of the above CIE but undertaken in-house by DWP using existing cost-benefit analysis modelling tools.

Evidence informing this final report is drawn from all research strands outlined above, with evidence from each strand being synthesised to generate the overall findings and conclusions presented. The first evaluation criterion addressed, that of effectiveness, is primarily informed by the qualitative case study and interview research, supplemented by use of evidence from the YEI MI and Leavers Survey. Insights into efficiency were primarily generated by the case study research, with some reflections on the results of the CBA also informing the analysis. Findings concerning the impact of the YEI draw on the CIE and CBA in respect of employment impacts, with the YEI MI and Leavers Survey also informing this along with other impacts including those relating to entry into education and training. The qualitative case study research was also used to explore ‘softer’ impacts, such as those on participants’ confidence, as well as some of the broader outcomes of the programme, including those on providers delivering support.

1.3.1. Limitations to the study approach

The initial design for the CIE element of the evaluation aimed to use administrative datasets relating to education, firstly to construct a statistically similar comparison group against which to compare the impact of support for a ‘treatment’ group of YEI participants, and, secondly, to include education and training outcomes, as well as employment outcomes, in the estimates produced concerning the YEI’s impact. However, anticipated access to these datasets proved not to be possible in the evaluation timescale.

As a consequence, some adaptations to the CIE model and approach were required. Specifically, lack of access to education datasets restricted the CIE analysis to employment outcomes, rather than including education and training outcomes as was initially felt to be possible. Lack of available education data also limited the amount of variables, notably those relating to educational history and qualifications, available for the construction of a comparison group to compare against YEI participants. However, as explained in more detail in the technical annex accompanying this report, we believe the lack of these variables would have had a limited effect on the employment estimates generated.

It should also be noted that full data from the YEI MI and Leavers Survey, covering the whole delivery lifetime of the programme, is not yet available. The YEI is still being delivered and hence the MI available is restricted to validated data available at the point of drafting this report. Findings from the Leavers Survey, being conducted by IFF Research on behalf of DWP, are likewise based only on fieldwork waves completed and available at the time of reporting. It should be recognised that these figures are subject to change by the time the YEI programme is finished. However, both the MI and survey sources cover the majority of the programme delivery period. Additionally, the Leavers Survey is based on a relatively large sample size of 2,213 respondents, while the MI data captures 73,935 YEI participations.

Data availability and the final research design also affected how far it was possible to address a small number of the research questions detailed above in section 1.2.1. In particular, the questions below, developed in light of the European Commission’s guidance on YEI evaluation, were not possible to address fully in light of the MI being collected and available for analysis, along with the final evaluation design adopted. Brief explanations for this are included next to the questions concerned.

- What were the unit costs per type of operation and per target group? (This was not possible to address due to this data not being collected at the project level, as explained in more detail in the efficiency section of this report).

- What are the direct and indirect benefits and costs to projects? Individuals? Local stakeholders such as employers? (This question was developed before a decision was made not to undertake an enhanced CBA, the potential for which was briefly examined at the outset of the evaluation. Primarily for reasons of comparability with other programmes, it was seen as preferable to use the cost-benefit model available internally to DWP analysts; this does not deal with costs and benefits in a way that would be required to address this question, and data to inform such an assessment was not gathered).

- What was the contribution of the YEI to changes in the youth employment/ unemployment/activity rates in the geographical areas covered by the YEI? (While it is possible to provide overall figures for YEI participants entering employment, presented in the report chapter on impact, it was recognised that using a CIE to estimate additional (net) employment impacts occasioned by the YEI was a more robust approach to estimating the programme’s contribution in this area. As covered in the technical annex to the report, sample sizes available for the YEI treatment group used in the CIE would not be sufficient to generate robust estimates of additional, or net, effects at the NUTS area levels within which the YEI was delivered).

1.4. Report structure

The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

- Chapter two assesses the effectiveness of the YEI in terms of targeting and engaging participants, the delivery of support, and the quality of the employment and training offers received by participants.

- Chapter three examines the efficiency of YEI delivery from the perspective of assessing the extent that inputs, financial or otherwise, translate to outputs and outcomes at the minimum possible cost.

- Chapter four examines the impact of the programme, considering both ‘hard’ impacts on participants in terms of, for example, its employment effects, and ‘softer’ impacts on participants such as confidence. It also assesses a series of broader impacts, including those on providers delivering support, along with estimating the programme’s economic benefits.

- Chapter five concludes the report by presenting some concluding reflections in the results of the evaluation, including revisiting the theory of change developed to help guide and structure the analysis.

A more detailed discussion of the methodological approach to the CIE element of the study is presented in a technical annex accompanying this report.

2. Effectiveness

Assessing the effectiveness of the YEI implies making judgements over whether, and the extent to which, the processes, mechanisms and activities put in place by YEI providers support the objectives of the initiative in terms of helping participants move closer or in to employment, education or training. In line with this focus, this chapter first considers how effective the YEI has been in targeting and engaging participants. It then examines the effectiveness of provision, both in terms of the types of support put in place and how effective they were in moving participants towards, or into, work or learning. Effectiveness is then considered from the perspective of available evidence on the quality of YEI employment and training offers.

2.1. Targeting of participants

Evidence from the sources reviewed for this report indicates that YEI delivery has been relatively effective to date in terms of targeting and engaging NEET young people, including those from specific sub-groups such as those facing labour market disadvantages. As detailed below, a review of programme MI, data from the ESF Leavers Survey, and evidence from the qualitative case study visits to ESF providers indicates that, while targeting and engaging participants has been challenging in some cases (including for some sub-groups), the programme as a whole has been broadly successful in engaging the numbers anticipated to date.

Analysis of programme MI available at September 2019 shows that of the 73,935 participants recorded as joining the programme thus far, two-fifths (40 per cent) are female and three-fifths (60 per cent) are male (Table 2.1). When compared to the targets in the refreshed ESF Operational programme (OP) published in October 2018, wherein the target for female participation is 43 per cent, this shows that the programme is broadly on target in terms of the anticipated gender split of participants. The figure of 73,935 participants engaged to date should be viewed in light of a lag in the submission and validation of programme MI. The real figure will thus be higher than this, though it does illustrate that the programme appears on course to meet the overall YEI participant engagement target until 2023 of 110,480[footnote 11].

Table 2.1 Participation to date by gender

| Gender | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 29,348 | 40% |

| Male | 44,379 | 60% |

| Other/ Undisclosed | 208 | 0% |

| All | 73,935 | 100% |

Source: YEI programme MI as at September 2019

Programme MI can also be used to illustrate the degree to which the YEI is engaging participants targeted by the ESF that experience some form of additional disadvantage (i.e. in addition to being NEET)[footnote 12]. As Table 2.2 shows, of the 73,935 participants joining the programme to date, almost three-quarters (74 per cent) were recorded as fitting one or more of the definitions of disadvantage used for the YEI. Self-reported additional disadvantage by survey respondents, including drugs and alcohol dependency and ex-offenders, was even higher (82 per cent). These findings suggest that YEI projects are successfully targeting and engaging NEET young people who face additional, and potentially multiple, disadvantages in respect of accessing the labour market.

Table 2.2 Participation to date: disadvantage / no disadvantage recorded

| Recorded | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| No disadvantage recorded | 19,358 | 26% |

| Disadvantage recorded | 54,577 | 74% |

| All | 73,935 | 100% |

Source: YEI programme MI as at September 2019

Further insights around the effectiveness of the YEI in targeting those facing labour market disadvantage are available from the YEI Leavers Survey, along with the qualitative case study research undertaken in late 2017. The survey data reveals that, at the point of engagement with support, just over two-fifths (41 per cent) reported living in a household where nobody worked, while nearly one in four (23 per cent) reported having a physical or mental health condition expected to last twelve months or more. In addition, more than a quarter of respondents (27 per cent) reported being from an ethnic minority background[footnote 13].

This suggests that the programme is engaging considerable proportions of participants falling into several of the main categories of disadvantage targeted by the YEI, including those living in a jobless household, having a disability, or coming from an ethnic minority background.

While smaller proportions or respondents were from groups facing other labour market disadvantages, such as having childcare or caring responsibilities or being homeless, the survey data does indicate that such groups are also being engaged onto provision. Specifically, 14 per cent of respondents reported that they had childcare responsibilities when joining the provision[footnote 14], six per cent that they had caring responsibilities on joining, and three per cent reported they were either homeless or living in hostel accommodation when joining.

It is also worth noting in this context that the YEI Leavers Survey suggests that the programme is engaging and supporting a significant proportion of the long-term unemployed (defined as being out of work for six months or more). Of those respondents stating that they were unemployed on joining YEI provision, more than half (53 per cent) reported being out of work for more than six months or never having had a job. In turn, this indicates that the objective of targeting harder to reach young people, or those more marginalised and/or isolated in other terms, is likely to be being fulfilled.

Evidence from the case study visits provides some insights into the reasons behind the broadly effective picture of targeting and engagement suggested by the MI and survey data. Firstly, it was apparent that most lead YEI providers are using local data and intelligence to help with targeting, including reviewing data on an ongoing basis to track changes in NEET levels / youth unemployment. Other common approaches reported to aid targeting and engagement included use of delivery partners’ existing networks, focusing extensively on outreach activity, developing partnerships with Jobcentre Plus to encourage referrals, and engaging in co-location with other services. This latter approach is considered in more detail in the following section on YEI delivery models.

Referrals from Jobcentre Plus appeared to vary in terms of their prevalence across the areas visited, in part due to differences in levels of engagement on the part of local Jobcentre Plus offices. In some cases, local labour market conditions also potentially appeared to play a role. Some provider interviewees felt that falls in youth unemployment had reduced the numbers of Jobcentre Plus referrals, while increasing the necessity of outreach activity to engage those not in contact with such services.

In respect of such activity, having a high street presence was reported to have encouraged self-referrals, including parents bringing young people in. Such an approach, along with word of mouth from peers having positive experiences of provision, was reported as particularly important in engaging NEET young people who are more disengaged from mainstream services – those sometimes referred to as ‘hidden NEETs’. At the same time, several interviewees acknowledged that this group, along with economically inactive NEET young people and lone parents, has proved more challenging to identify and engage. As one YEI provider representative explained:

The issue has been around finding the young people who are economically inactive … We already recognise that they can be quite challenging to reach because they might not necessarily engage with the traditional means of targeting them… so essentially it requires a more innovative and, quite frankly, a tenacious approach. (YEI delivery staff representative)

In respect of lone parents, it was similarly noted by a provider representative that it

…takes time to build up trust and they have more complex barriers.” As discussed in section 2.2, co-location with services supporting (young) parents was seen as an effective response to challenges around engaging this sub-group.

Effectively targeting more ‘hidden’ NEETs was likewise cited as important in a context of falling youth unemployment; to ensure good engagement levels several projects reported having to focus more on this group than anticipated. In turn, several interviewees advanced the perspective that the YEI was engaging those further from the labour market in many cases, with participants from this group often requiring more intensive and longer periods of support. Specific challenges related to this were also cited: for example, accessing and sharing data on inactive young people and ‘hidden NEETs’. While seen as challenges to effective delivery, such issues were generally not viewed as notably compromising the effectiveness of targeting and engagement. Again, co-location to facilitate data and intelligence sharing was seen as a helpful solution in this context.

Finally, it is worth noting that identifying marginalised young people was often seen as less of a challenge than getting them to positively engage with provision and maintain that engagement, suggesting that this group might be ‘harder to support’ rather than ‘hard to reach’ or ‘hard to find’. Linked to this, the voluntary nature of the YEI was seen as promoting engagement amongst more marginalised young people, and encouraging that to be maintained, rather than hindering it. Several provider representatives positively contrasted the YEI with programmes mandating attendance from this perspective. Similarly, participants interviewed also welcomed the voluntary nature of the provision and felt that this had encouraged, rather than discouraged, them to engage with the programme and maintain this.

2.2. Enablers and barriers to YEI delivery

Part of assessing effectiveness involved considering which YEI delivery models, or elements therein, appeared to promote effective support to NEET young people, as well as any aspects that appeared to hinder this. There were few aspects to the design of delivery models that appeared to hinder effectiveness. Conversely, several aspects to delivery models emerged as key to YEI’s effectiveness in supporting those engaged. Evidence for this assessment was drawn from provider and participant perspectives gathered through the project visits, along with the results of the YEI Leavers Survey. Elements reported as key to supporting effective delivery were, in particular:

- The co-location of YEI delivery with other related services supporting young people

- The development of partnerships and referral routes to offer holistic support to young people and address their particular issues

- The establishment of effective governance procedures, including mechanisms to engage and benefit from the input of Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) representatives.

Co-location with other services was frequently referenced as having a number of benefits for effectiveness. As well as supporting the targeting of lone parents as noted above, co-location in children’s centres was cited as effective in supporting joint working with other services, facilitating data sharing and a ‘joined-up approach’, and encouraging and facilitating cross referrals of young people. More broadly, co-location in hubs providing a range of community services was cited as effective in several instances for similar reasons.

In the majority of cases, YEI projects utilised a ‘hub and spoke’ delivery model, enabling a wide support offer to be provided to participants across lead and partner delivery organisations. This approach was widely seen as effective in ensuring that young people could access additional and specialised support as required. Combined with the key worker role adopted by most projects, examined in more detail in the following section, this delivery model was reported as being effective in supplementing dedicated, case managed, support for participants (the ‘hub’) with referral to specialist support as required (the ‘spokes’).

Whether or not the additional and specialised support available was delivered by organisations within the formal YEI delivery partnership appeared less important than ensuring a range of support could be accessed. Thus, in instances where a lead provider alone formed the delivery model, such organisations were still able to refer to specialist support as required. It was noted, however, that including specialist providers within the formal delivery partnership offered the chance for lead providers to manage their delivery partners more closely.

2.3. Effectiveness of YEI provision

In addition to the effectiveness of YEI delivery models, the actual activities and forms of support offered to YEI participants also appear to have been largely effective. Both the case study visits to projects and findings from the YEI Leavers Survey provide a number of insights into the relative effectiveness of different activities and types of support, and the relevance of the support provided in terms of meeting the needs of participants and particular sub-groups within the overall YEI cohort. The range of support available, and the extent it was tailored to individual needs through an ‘action planning’ process, was cited by both YEI participants and provider staff as a key factor in its perceived effectiveness. Equally, the adoption of key worker models, providing dedicated, case managed support to participants, emerged as a consistent theme in discussions of effective types of support.

2.3.1. Effective types of support

Based on evidence gathered from provider staff and participants through the case study visits, many of the activities offered through the YEI appear to be effective. However, their relative importance or effectiveness was acknowledged by provider staff as being likely to vary according to the particular individual being supported, along with other contextual factors such as local labour market conditions. Forms of support most consistently cited as effective by staff tended to mirror those seen as most effective from a participant perspective. In particular, these included:

- The adoption of ‘key worker’ models to provide consistency of support and an overview of case management for each participant.

- ‘Wraparound’ support designed to address individuals’ personal and often deep-seated challenges and barriers to (re-)engaging with work and learning, in particular those relating to confidence, attitudes, and aspirations, along with physical or mental health conditions.

- Short, sharp interventions (usually to address a small employment need/gap in a young person’s CV or qualifications), like a Construction Skills Certification Scheme (CSCS) qualification, which can lead to further enhanced qualifications.

- English and mathematics provision (in terms of these being basic requirements for better jobs, and young people being motivated to get these qualifications in light of this, as evidenced by several interviews with participants)

- Training linked to an employment route-way (for example, in colleges or sector-based work academies; or training that has been delivered with the support of an employer). It was noted that seeing an employment opportunity at the end of a qualification or training is an effective motivator, particularly for young people closer to the labour market.

- Social or community-based activities and volunteering, cited as helping young people to regain/build up their feelings of engagement in the local community and helping the community to change their perceptions of NEET young people.

Amongst the above elements, the key worker role, typically used by projects to facilitate the ‘wraparound’ support delivered, was particularly widely referenced. Depth interviews with YEI participants conducted as part of the case study visits strongly indicated the importance of this aspect of support. Displaying trust and faith in participants as individuals, flexibility in responding to needs, offering support in a sensitive and compassionate way, and working at a pace suited to their needs were common themes expressed in discussing the role played by key workers. The comment of one young person sums up several of these aspects:

To say helpful is an understatement, because [key worker] has got me in touch with new contacts and she is always inspiring… She is approachable, compassionate and always interested. She’s the only one who truly has faith in what I can do. (YEI participant)

While also being seen as effective in many cases, other elements of the YEI offer were seen as more nuanced in their effects and/or as challenging to successfully and consistently offer. Work experience and work placements fall into this category. When suited to participants, and a good match with aspirations achieved, it was apparent that such support could be highly effective in building confidence, adding to individuals’ CVs, making participants believe that they could find work, and, in a number of cases discussed on the case study visits, being key in participants successfully entering employment.

However, in a small number of cases participants’ experience of placements had been less positive, generally due to the placement being different from expectations and/or the individuals concerned struggling with the work environment for a number of reasons. Equally, from a staff perspective, encouraging employers to provide tasters and work experience was seen as challenging in some cases, due to a perceived lack of incentives to facilitate such activities. Despite this, it was apparent that some YEI providers were particularly effective in securing opportunities through, for example, dedicated employer engagement teams. Equally, just over half of YEI Leavers Survey respondents reported that their programme provided a work placement or work experience (51 per cent), suggesting that this form of support was relatively widely available.

Again, while effective in many cases, support to access traineeships and apprenticeships was another area where there was some variation evident in the relative effectiveness of support. Limited numbers of suitable apprenticeships in some contexts was referenced by provider staff as a challenge. Equally, there was a perception from both provider staff and some participants that, in many cases, apprenticeships are more beneficial for the younger age range within the YEI cohort rather than for some older people. For example, it was noted that the latter can have family responsibilities; in this and some other contexts apprenticeships were seen as not paying enough. Conversely, where suitable apprenticeships were available, and young people were interested, a number of examples were given about how young people had been supported and given the confidence to access them, as well as support being provided to identify suitable opportunities in the first instance.

2.3.2. Effectiveness in meeting participant needs

There was a clear consensus amongst all stakeholders interviewed as part of the case studies, including participants, that the range and flexibility of provision was a particular feature of the ‘YEI offer’. These aspects were seen as ensuring that the provision could effectively meet participants’ varied support needs. Linked to the previous discussion of delivery models, tailoring support to individual needs in a flexible way, rather than putting young people through a set support pathway or course, was commonly highlighted as important. Several participants positively contrasted this approach with previous, more structured and less flexible, employability support programmes they had experienced.

Both provider staff and participants also felt that the tailored and flexible approach evident was likely to contribute to the sustainability of any outcomes achieved. As one participant discussed, the support provided by a key worker had enabled him to focus on thinking in terms of a career, rather than just taking the type of low-paid and precarious employment he had previously been used to. Addressing more deep-seated issues putting young people at a labour market disadvantage was also referenced. Many interviewees cited the importance of addressing confidence issues, anxiety, lack of aspirations, and mental or physical health barriers as ‘first order priorities’, before moving onto more employability or learning-focused support. Direct evidence from participants, and examples given by provider staff, suggest such an approach is important, effective, and likely to generate more sustainable effects.

In terms of flexibility, the opportunity to combine elements of financial support with intensive confidence building, and other support focused on breaking down personal barriers to work and training, was highlighted in several contexts. For example, the prevalence of a reluctance to travel for work and training amongst those more isolated and marginalised was frequently discussed as a significant barrier. The ability to offer support to address this, combining financial assistance, for example to buy travel passes, with more ‘hands on’ support, in terms of accompanying young people the first time they travelled a particular route, was seen as both important and effective in meeting the needs of many young people.

Particularly innovative provision was also evident in several cases, with the driver for such innovation again linked by provider staff to the desire to meet young people’s needs, in particular through providing support that was engaging and likely to encourage on-going contact. Examples included training to restore and repair bicycles that young people then kept, training to produce items involving 3-D printing, and using sport as a lever for engagement and as a hook to get young people to engage with employability skills without necessarily recognising it as such.

The apparent effectiveness of the YEI in meeting participant needs appears to be confirmed by the results of the YEI Leavers Survey. Amongst respondents, 89 per cent were satisfied with the guidance and information about the support they would receive and 88 per cent were similarly satisfied with the guidance and feedback received during support, with these elements typically being a core part of the key worker role. The overall satisfaction rate with the support similarly reinforces the impression of effective delivery. Just under half (47 per cent) were ‘very satisfied’ overall whilst a further 38 per cent reported being ‘fairly satisfied’. Less than 1 in 20 respondents were ‘fairly dissatisfied’ (3 per cent) or ‘very dissatisfied’ (3 per cent) with the support received.

Combined with the case study evidence this presents a persuasive case that the nature and delivery of YEI support is, in most cases, effective in addressing the issues and challenges young people face.

The following case study, based on a depth interview with a YEI participant[footnote 15], helps illustrate the range of support provided, the significance of the flexible and tailored approach outlined, and some of the effects this had.

Case study – YEI provision (Gareth)

Gareth left college as he was not enjoying his courses and was signposted to the YEI through a family contact. The idea of adding to his CV was appealing, although he had few expectations. Once Gareth started, he really enjoyed the opportunity to meet new people and to establish new social connections. Gareth was introduced to his 1-1 key worker who helped him with finding an apprenticeship. He spoke of the individual support he received:

It was all done from the point of view of how they can help us. I had an interview with my coach [key worker]. We came up with a plan for how we could move forward towards our goals. It was all based on what we wanted.

The support offer from the YEI included: CV writing support, help with job searches, applications and gaining work placements, and working on the YEI provider’s reception. He was also later supported by his key worker to research, access and ultimately begin an apprenticeship. Gareth noted how the YEI had exceeded his expectations and hopes:

It’s been way better than I expected, I have learned lots of new things… the employability support will help me the most in the future.

For Gareth, the YEI support differed from a number of other employability programmes he had accessed in the past. He said that the YEI had “put him on track” and that “nobody else was able to do that”. Additionally, it was evident that there were softer outcomes that were generated for this participant. In terms of improvements in confidence, overcoming personal challenges and improving wellbeing:

It’s built my confidence, when I first came I was the shyest person – I had anxiety. This has really helped me, my mental health is much better now.

2.3.3. Less effective aspects of support

While the evidence suggests the majority of YEI provision is generally effective, and meets young people’s needs, some forms of provision appeared to be less effective in some instances. More structured provision in a classroom setting was cited as discouraging the engagement of young people in some cases, potentially due to prior negative experiences at school, with this being reflected in the views of some participants interviewed as part of the case study visits. Partly to address this, some providers had experimented with different settings and with combining classroom settings to discuss employability skills with other activities, including sports.

In a minority of cases evident in the context of the case study visits, there was also some evidence of providers ‘holding on’ to young people they had engaged, when provision elsewhere in a partnership or progressing young people onto other support would have been more beneficial. This was reported by lead partners as a problem in a limited number of instances, despite efforts to mitigate it through messages to the partnership and the manner in which contracts and memoranda of understanding detailing expectations had been designed.

2.4. The quality of YEI employment and training offers

In line with the evaluation guidance for the YEI published by the European Commission[footnote 16], a further aspect to assessing effectiveness involves the quality of YEI employment and training offers received by participants. While individual examples of participants accessing what were reported as good quality jobs and apprenticeships were revealed through the case study visits, the best evidence to address effectiveness in this area comes from the YEI Leavers Survey. Overall, this suggests a positive picture in terms of the quality of training offers received and, where applicable, forms of learning that YEI participants were engaged in six-months after leaving. Similarly, most evidence from the Leavers Survey points to a broadly positive picture in terms of the quality of jobs/job-offers received by participants.

Looking at the evidence in more detail, of those respondents to the survey who reported having done a traineeship as part of their YEI provision (19 per cent), 82 per cent reported that the duration of their traineeship was ‘about right’ with only one in ten (10 per cent) feeling that it was too short. Perhaps more importantly in terms of assessing quality, 9 in 10 (89 per cent) felt that their traineeship would improve their chances of getting a job; of this group over half felt that their chances had improved to a ‘large extent’ (53 per cent) and a further 36 per cent felt their chances had improved to ‘a little extent’.

In terms of satisfaction, over half of the respondents accessing a traineeship (54 per cent) were ‘very satisfied’ with it overall in terms of the work experience gained and how they have benefitted since. A further 35 per cent reported being ‘fairly satisfied’, with a minority (7 per cent) being either ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ unsatisfied. Combined with the perceived role of traineeships in supporting them to find work, these high satisfaction levels from participants suggest a positive view of the quality of the traineeships available through the YEI. Data available in respect of those in education or training six months after leaving also appears positive in the sense that, amongst respondents in this position, over four-fifths (83 per cent) reported that this would lead to a nationally recognised qualification.

While the data relating to employment available through the YEI Leavers Survey relates to those respondents in work at the six-month point after leaving provision, and hence respondents may have moved jobs or moved into work after leaving YEI, the findings available can nonetheless be used to draw some conclusions as to the quality of jobs that YEI support helped lead to (either immediately on leaving or soon after). Of the survey respondents in work at the six-month point after leaving (45 per cent of total respondents), half (50 per cent) were on a permanent employment contract and a further 14 per cent on a contract lasting 12 months or more. This suggests the majority of jobs gained by YEI leavers were fairly stable and long term.

However, just under a quarter (24 per cent) of those in work at the six-month point were either on temporary or zero-hours contracts, demonstrating less stable forms of work for a notable minority of YEI leavers. This should, though, be considered in the context of part-time, temporary, and zero hours working in the UK having increased relative to permanent employment in the last few years. In this context, the survey finding that just over seven out of ten participants in work at the six-month point were in full-time jobs (70 per cent) can also be viewed as relatively positive from a job-quality standpoint. Equally, it should be noted that approaching half (46 percent) amongst the 29 per cent in part-time work did not wish to work full-time.

Further positive evidence in terms of job quality can be gained from the nearly six in ten (58 per cent) YEI leavers responding to the survey that had received a job offer between starting on the provision and six months after leaving. Of this group, almost two-thirds (62 per cent) rated the quality of job offers received as either ‘very good’ (27 per cent) or ‘good’ (35 per cent). While a further 26 per cent rated their offers as ‘reasonable’, fewer than one in ten (9 per cent) rated their offers as either ‘poor’ or very poor’. Allied to the above findings on the nature of the jobs accessed, this appears to confirm the impression of generally good quality jobs/job-offers resulting from engagement with the programme.

3. Efficiency

Assessing the YEI’s efficiency requires consideration of the degree to which inputs, financial or otherwise, translate to outputs and outcomes at the minimum possible cost. The extent to which duplication of activity with other provision is also relevant from this perspective. This implies a focus on examining how, and the extent to which, YEI providers have sought to minimise costs and provide value-for-money. In assessing efficiency, this chapter thus examines evidence on provider approaches to value-for-money, along with considering insights that can be gained around the relative efficiency of particular activities and the factors that help or hinder the efficient delivery of support.

3.1. Approaches to ensuring value for money

The impression from the visits to YEI providers was that organisations delivering the YEI are concerned with ensuring efficiency and hence ultimately offering value-for-money. It was noted on several occasions that doing so is part of the general ethos of the organisations concerned, and in their own interest. From this perspective, representatives cited that failing to operate efficiently and/or offer value will result in winning less employability and training contracts, losing money on delivery, and ultimately compromising their organisations’ viability. Most provider representatives were thus able to offer concrete examples of where they had sought to ensure value-for-money through their delivery approach.

While a range of such examples were offered, a number of common themes and groups of related examples emerged. These can be summarised as follows:

- Focusing on reducing internal costs, including:

- Close control of staffing numbers and ensuring appropriate caseloads

- Focusing on staff progression, retention and training to reduce recruitment costs and ensure that staff are delivering as efficiently and effectively as possible

- Reducing transaction costs between delivery partners by developing effective systems of referrals, data sharing, IT solutions, and communication

- Reducing overheads such as accommodation, venue hire costs, and electricity costs where possible

- Reducing costs through re-use and recycling, for example of materials used in activities, with some interviewees linking this to their focus on sustainability as an ESF cross-cutting theme

- Seeking to ensure value in terms of the activities offered, for example by tapping into and/or expanding existing provision to ensure cost-effectiveness, or using account holder discounts when purchasing provision and courses

- Designing activities to ensure value-for-money, including careful consideration of where group work would be an appropriate and efficient solution for example

- Avoiding any overlaps or duplication with other provision locally so as to avoid the potential for the available funds to be wasted

- Lead YEI providers focusing on ensuring value amongst delivery partners, through provision of guidance, development of memoranda of understanding, oversight by finance officers, and, for example, requiring partners to consider and justify particular expenditure, such as that related to supporting transport costs amongst participants.

While typically offering several examples of how value-for-money is promoted, it was also common for provider representatives to reflect on the nature of the YEI target group and the level of support often needed in this context. In particular, interviewees commonly argued that the individualised, wraparound support frequently provided necessarily has a cost attached, and that meeting complex needs can, in some cases, be relatively expensive, even while their delivery overall strives for value-for-money. In some instances, the point was made that delivering what participants need is the core focus, and a strength, of the programme, rather than having to ensure the lowest possible delivery cost in all cases. As one interviewee commented from this perspective, “…this way of working takes longer but the results do come”, while a lead provider representative noted:

…V-f-M is fundamental. We always test the value, ask providers if they can do things at a better price … But we want quality so [there is] a balance to be struck about value and quality. (YEI lead provider representative)

3.2. Efficiency of activities

While the case study visits offered a broadly positive impression of efficiency, there are some limitations to precisely assessing the efficiency of specific types of provision and activities. This relates principally to a lack of data being collected that would facilitate such an assessment, with providers not generally identifying costs and throughput of individual activities (in terms of numbers participating) in this way. In addition, it was evident that the inter-related nature of many YEI activities naturally makes such data gathering and assessment problematic.

Reflecting this, providers generally struggled to identify which specific activities were most beneficial from a cost-effectiveness or efficiency perspective, in part because the nature of the holistic, wraparound support typically offered by the YEI meant it was hard to disentangle individual elements to consider their cost-effectiveness. In addition, a lack of hard data or evidence on which to, reliably, base such an assessment was also frequently referenced.

Where interviewees offered views on the relative cost effectiveness of provision, these tended to relate to those activities seen as having the most effect on the young people supported. Therefore, work around personal development, such as building confidence, was seen as intensive though ultimately cost-effective when balanced against the positive effects this was often seen as having for young people. As noted in the previous chapter, such work was seen as important in generating outcomes in terms of young peoples’ confidence, aspirations, and attitudes, but also in terms of its key role in progressing participants towards work or learning outcomes, and opening the way to more of a direct focus on achieving these.

Short courses leading to required qualifications were also cited from this perspective, in that a relatively small outlay could fill a gap in a participant’s CV and unlock opportunities. The perceived cost effectiveness of such short, sharp interventions was thus stressed in several cases.

In addition, several interviewees made the point that most YEI support could be cost effective in terms of costs avoided. A number of specific examples were cited of individuals securing access to apprenticeships, traineeships or being supported into work who otherwise might engage in criminality or impose other societal costs based on their previous behaviour. Ex-offenders were seen as a particularly relevant client group from this perspective, though it was noted that a number of participants had histories of more low-level anti-social behaviour.

Similarly, the perceived cost-effectiveness of activities was often related to the avoidance of any duplication of provision. In several cases, provider representatives described how they had undertaken mapping of local provision targeting young people in the course of designing their YEI offer, so as to complement and not duplicate this. The stress on avoiding duplication in the YEI guidance, and throughout the bid process, was also seen as supporting this end. Most provider representatives had a high degree of confidence, therefore, that duplication of provision with other non-YEI support for young people was being minimised.

The view of provider representatives was almost universal in terms of arguing that there were not really any forms of provision or specific activities that were inefficient per se. It was noted in a number of cases that delivery organisations are typically very experienced at offering the type of support provided through the YEI; therefore, the perspective was that any activities that did not offer efficiency and value in the past have been discontinued. The point made above concerning the view that the nature of the support, and responding to specific needs, implies a certain level of cost, was also made in this context. From this perspective, while ensuring efficiency and value was seen as important, addressing the particular needs of participants, within reason, was viewed as even more so.

While only limited indications of the relative efficiency of activities can be derived from the available evidence, more specific findings can be offered as to aspects promoting or hindering efficiency. These are covered in the following sub-sections.

3.2.1. Aspects promoting efficiency

Several providers cited a focus on unit costs in developing their provision as a factor supporting efficiency. This was noted as resulting from DWP as the ESF MA requesting details of such costs in the application process. This was felt to have encouraged, as one interviewee put it, a ‘sharp focus’ on costs and hence to promote efficient delivery. Partnership working and effective governance was likewise a key theme in this area. This was seen as aiding efficiency from several perspectives: in terms of ensuring that the particular skills and capacities of organisations within the delivery partnership were efficiently and effectively deployed, that efficient mechanisms could be established – for example in terms of cross referral – and that performance could be managed by the lead partner to promote efficiency. Finally, as noted above, organisational experience and commitments to delivering efficiently were, in themselves, seen as promoting efficiency within YEI delivery.

3.2.2. Challenges to efficiency

While the overall impression was that YEI support was being delivered efficiently, provider representatives and other stakeholders did acknowledge that some elements of the programme posed challenges to this. Although probably only accounting for only a small part of YEI projects’ overheads, interviewees cited revisions in guidance, the data portal, and levels of evidence requirements needed for the Managing Authority’s financial assurance processes as a burden for delivery.