Main report

Published 22 October 2019

Women’s Progression in the Workplace

Laura Jones, Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, Kings College London

October 2019

Executive summary

The central aims of this research were to:

- provide an overview of the gender divide in progression in the workplace

- understand what is known about the barriers and facilitators of women’s progression

- critically review and synthesise the evidence on which organisational policy interventions have been demonstrated to be successful in improving women’s progression in the workplace

- identify possible untested organisational interventions which the evidence suggests could be successful

Progression was interpreted broadly as meaning not only moving up the occupational hierarchy, but also any job change that resulted in better pay, working conditions, responsibility or security.

The research took the form of a rapid evidence assessment of academic literature. Evidence on the extent of the gender divide in progression and the barriers and facilitators was limited to the UK, while evidence on organisational interventions was not geographically limited.

The gender divide in progression

The report looked at 2 key ways to measure progression – wage growth, and movement up a vertical occupational scale. In both cases the gender gap is minimal on labour market entry and widens significantly from the late 20s and early 30s as women’s progression plateaus. Gender differences in part-time work are important explanations for these differences, but a substantial amount remains unexplained.

Another key difference is that women who enter the labour market in low-paid jobs experience ‘sticky floors’ – rarely progressing upwards. By contrast, such jobs are ‘springboards’ for men into higher paid positions. This springboard vs sticky floor dichotomy has worsened over time.

Barriers to progression

This research condensed over 100 studies carried out in the UK between 2000 and 2018 to understand the organisational barriers to women’s progression, as well as any facilitators. Four key groupings of barrier were identified:

-

Processes for progression that open up space for bias. In the absence of clear systems and transparent systems, decisions about pay and promotion are more likely to be made through processes that disadvantage women, including via networks and the process of social cloning, where those in positions of power champion those who are like themselves.

- Hostile or isolating organisational cultures including issues of sexual harassment and stereotyping.

-

The conflict between external responsibilities and current models of working. In many workplaces persistent norms of overwork, expectations of constant availability and excess workloads conflict with unpaid caring responsibilities – the majority of which still fall on women. Unpredictable work demands linked to casualised forms of labour also pose challenges, as do the requirement in some fields of the necessity for geographic mobility to progress.

- Alternative ways of working do not currently offer parity. There continues to be a shortage of quality part-time work and part-time experience offers very little return on experience in terms of wage growth. While there is evidence of an increase in the proportion of female senior part-timers, the evidence suggests this is largely as a result of already senior women negotiating a reduction in hours. Meanwhile, part-timers in lower occupational jobs (most of whom are female) receive low wages with limited opportunities for progression. Evidence from the UK also suggests there is the potential for flexible workers to suffer negative career consequences.

Organisational interventions to support women’s progression

The review uncovered evidence of a range of different types of intervention designed to support women’s progression in the workplace. Some of the key conclusions from this section:

-

Transparency and formalisation are key to reduce gender bias. Interventions to make the processes for promotion and progression standardised and transparent – such as formal career planning, clear salary standards and job ladders - are linked with improved career outcomes for women. This is especially the case when combined with senior oversight and accountability of these processes.

-

Alternative working time policies need to go alongside efforts to reform organisational culture to include them. Flexible and part-time work are important factors helping women to maintain their labour market position following the transition to parenthood, but need to be combined with efforts to reform organisational cultures to truly accommodate them. Alternative working time policies without culture change are not enough and risk embedding gender inequality due to the negative effects these practices have on career progression in contexts where part-time and flexible working are seen as signalling a lack of commitment. Organisations which show ongoing top-down commitment to supporting part-time and flexible workers mitigate some of these barriers. Senior role models who talk openly about balancing work and family life, or who work part-time, are important for reducing flexibility stigma, as are supportive line managers and organisations which train line managers to deal with part-time and flexible workers.

Conclusions and implications for policy

The largest barriers to women’s progression in the workplace continue to arise from a conflict between current ways of organising work and caring responsibilities. Long-hours cultures, expectations of constant availability and a lack of part-time progression are enduring features of modern workplaces.

This suggests that the policy focus should be on reforming organisational cultures away from norms of overwork and supporting the construction of ‘non-extreme’ jobs, which do not require long hours and constant availability as a proxy for commitment, and which support part-time progression at all levels. Alongside policies to support work-life balance should come efforts to reform the deeper structures and workplace processes which encourage long hours.

At the same time, the stigma associated with part-time and flexible work is likely to persist so long as these ways of working continue to be associated with women, while men work long hours.

Policies that encourage and enable men to take on greater childcare responsibilities are thus essential if women are to be able to maximise their potential.

The other main barrier to women’s progression comes from organisational norms and processes that allow gender bias to creep into decision making. When there is a lack of clarity around the standards for recruitment, promotion or pay negotiation decisions are more likely to be made in ways that disadvantage women, whether because people in power seek those who are like them or because who you know is more important than what you know. Organisations should ensure that they have clear standards for promotion and advancement and create mechanism for organisational oversight of these processes.

1. Introduction

This chapter provides a brief overview of the context behind the commissioning of this study as well as of key relevant policy directives.

1.1 Policy context – the gender pay gap

The UK’s overall gender pay gap (GPG), the difference between men and women’s median hourly earnings, is 17.9% (ONS, 2018). Progress towards closing the gap in recent years has been slow, and has occurred against a backdrop of declining real wages, meaning that a narrowing in the GPG has come at the expense of wage growth for both men and women (Olsen and others, 2018).

The government is committed to taking action to close the GPG. Their flagship policy, gender pay reporting, came into force in April 2018 and requires all employers with over 250 employees to publish their GPG. This policy was designed to increase transparency and accountability among employers. The government also recognises that it is important to support employers to understand and tackle the drivers of their GPG. To this end it is working to build the evidence base to understand what employers can do to help reduce their own GPGs.

The GPG is measured as the difference in the average hourly wage of all men and women across the workforce. This means that if there are more women than men in less well-paid jobs within an organisation, and more men in the better paid jobs, the GPG will be bigger. Of the 10,000 employers who had submitted their GPG data to the government by August 2018, over 80% had more women in their lowest paid positions than in their highest paid positions (Government Equalities Office, 2018). While, overall, more women than ever before are employed, they continue to be overrepresented in low paid, part-time and insecure employment (De Henau and others, 2018). Understanding why women continue to outnumber men in less well-paid roles is therefore key to closing the GPG.

Government policy has sought to address barriers to women’s progression opportunities through policies designed to facilitate the reconciliation of work and caring responsibilities. These include the right to request flexible working. Introduced in 2002, this right entitles qualified employees to apply to their employers for a change to their terms and conditions of employment relating to the hours, times and location of work. When introduced, this right applied only to a limited category of employees with parental or caring responsibilities. The Children and Families Act 2014 extended the right to all employees with 26 weeks’ continuous employment (Pyper, 2018). Other initiatives have more directly targeted employers, including a focus on increasing the number of women on boards following the Hampton-Alexander Review and the compulsory GPG reporting.

Enabling women to fulfil their full potential in the workplace is not simply a consideration of equality. Research carried out by the Women and Work Commission estimates that the under- utilisation of women’s skills costs the UK economy between 1.3 and 2% of GDP every year (Women and Equalities Committee, 2016).

1.2 The GPG: drivers and protective factors

Analysing data from the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Survey (UKHLS) relating to 2014/15, Olsen and others (2018) model the predictors of the GPG, referring to those predictors that increase the GPG as ‘drivers’, and those that decrease it as ‘protective factors’.

Figure 1 presents the results of this analysis along with an explanation underlying each of the drivers and protective factors.

Figure 1: Main drivers and protective factors of the pay gap in the UK

Drivers:

- Occupational segregation (19%, £0.31) – The types of job that women tend to do are less well paid than the types of jobs that men do.

- Industrial sector (29%, £0.47) – The sectors of the economy that women tend to work in are less well paid than the sectors that men work in.

- Unobserved factors (35%, £0.57) – Part of the GPG cannot be explained by the data we have — but factors could include discrimination, harassment, preferences, and choices (constrained or otherwise).

- Labour market history (56%, £0.91) – Differences in the ways men and women participate in the labour market: 12.7% is accounted for by the fact that women tend to have more years spent out of the labour market and undertaking unpaid care work than men, and 43.6% is accounted for by the fact that women tend to have fewer years of full-time work experience than men.

Protective factors:

- Part-time employment history (-20%, -£0.33) – The different types of part-time jobs that men and women do – women who work part-time tend to have higher quality jobs than men who work part-time.

- Institutional factors (-16%, -£0.26) – Women tend to benefit from workplace factors such as public sector employment, union membership, firm size and job tenure

- Education (-4%, -£0.06) – On average, women have slightly more years of education than men, and more highly educated women have

Source: Olsen et al (2018)

1.3 About the research

In order to understand more about the barriers preventing women’s progression in the workplace, and how best to support employers to remove these barriers, the government Equalities Office (GEO) commissioned the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership to undertake a rapid evidence assessment (REA) on this topic. The review was commissioned in June 2018 and considered evidence up until August 2018.

1.3.1 Research aims and questions

The aim of this research was to provide an overview of the gender divide in progression in the workplace in the UK, an understanding of the barriers and facilitators of women’s progression, and a critical overview of organisational policies that employers can implement to successfully remove these barriers.

There are various different ways of measuring progression. In this report progression is interpreted broadly as meaning not only moving up the occupational hierarchy, but also any job change that results in better pay, working conditions, responsibility or security. The focus of the research is, therefore, loosely on what is termed vertical segregation – that is the ‘concentration of women and men in different grades, levels of responsibility or positions’ (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2019).

The main objectives of this research were to:

- establish the extent of the gender divide in progression in the workplace as identified in the UK literature

- understand what is known about the barriers and facilitators to women’s progression in the workplace

- critically review and synthesise the evidence on which organisational policy interventions have been demonstrated to be successful in improving women’s progression in the workplace

- identify possible untested organisational interventions which the evidence suggests could be successful

1.3.2 Research approach

To provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on this topic in a short time-frame, a rapid evidence assessment (REA) approach was adopted (for further details please see the appendix). The search was limited to peer-reviewed papers readily accessible online in English. After a series of scoping searches produced a large number of hits, a decision was made to limit the evidence for objectives 1 and 2 to UK based studies, while leaving the evidence for objectives 3 and 4 geographically unlimited. The search was time limited to return only literature published from 2000 until August 2018. For objectives 1 and 2 this still produced a large number of relevant papers and so all located literature published between 2010 and 2018 was read and then literature focusing on under-researched groups or occupations published prior to 2010 was prioritised.

Search terms were developed iteratively through a series of scoping exercises and agreed with the GEO prior to running the final searches. Searches were supplemented by ‘pearl-growing techniques’, including following up on the references of key texts, and papers subsequently referencing them. A set of agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria was drawn up, including an assessment of the quality of the methodology.

Through this approach, 175 articles were identified for inclusion.

1.4 Report structure

This report contains findings synthesised from the REA on the gender divide in progression in the workplace.

Chapter 2 sets out findings on the extent of gender divide in progression in the workplace. It considers 2 different ways of capturing progression. Section 2.1 looks at progression to higher pay and the role of parenthood and part-time work in explaining gender differences. Section 2.2 looks at progression up the occupational hierarchy, the explanatory role of part-time work in explaining gender differences and the gender divide in progression out of initial ‘bad’ jobs.

Chapter 3 contextualises the national data presented in chapter 3 by synthesising findings from mainly qualitative firm or occupation level studies on the barriers preventing women’s progression, as well as any identified facilitators. The evidence for this chapter was limited to studies conducted in the UK. These barriers and facilitators are grouped into 4 main categories. Section 3.1 looks at organisational norms and processes, Section 3.2 looks at hostile or isolating organisational cultures, Section 3.3 looks at the conflict between caring responsibilities and current models of working. Section 3.4 synthesises evidence on the current difficulties that alternative working patterns offer in terms of career progression. Finally, Section 3.5 links the findings of this chapter to broader labour market trends.

Chapter 4 provides a critical synthesis of evidence from studies which tested interventions to improve women’s progression in the workplace. The evidence for this chapter was broadened to include studies conducted in any country which addressed barriers identified in the UK context.

Chapter 5 concludes the report with a discussion of key findings and their implications.

2. The gender divide in workplace progression

For the purposes of this report we interpreted progression broadly, as meaning not only moving up the occupational hierarchy, but also any job change that resulted in better pay, working conditions, responsibility or security.

Because inter-occupational hierarchies are not comparable across occupations, progression can be difficult to capture quantitatively in a way that enables broad comparisons. In this section we look at 2 different ways of capturing progression: progression to higher pay (2.1) and progression up a ranked occupational hierarchy (2.2). This section is based on studies which analyse nationally representative survey data.

2.1 The gender divide in wage progression

2.1.1 A steady upward trajectory for men, a plateau in their late 20s for women

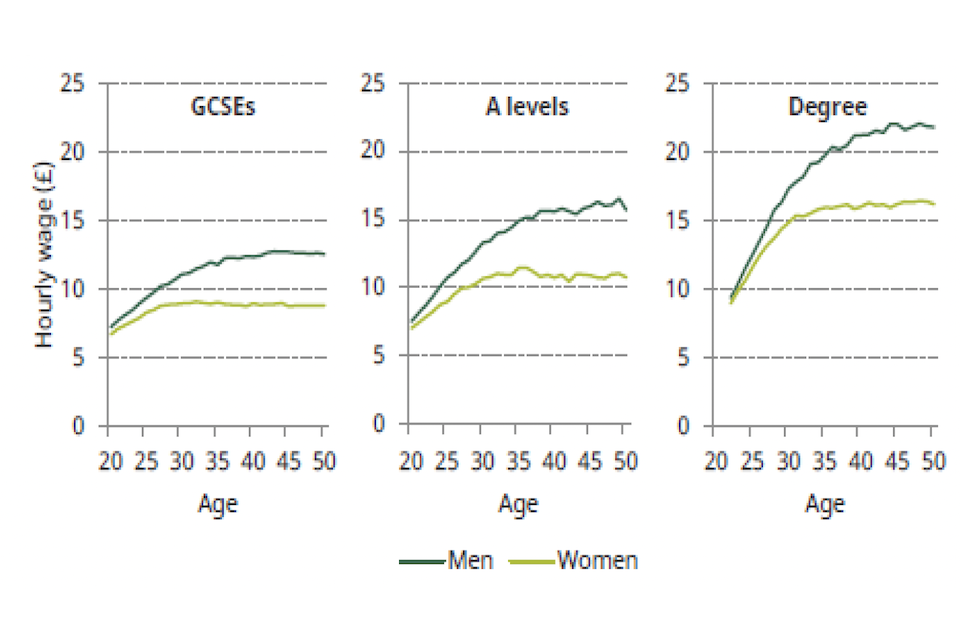

Costa Dias et al (2018) use data from the Labour Force Survey, British Household Panel Survey and Understanding Society from 1991 to 2015 to study the gender differences in wages over the life- course (figure 2). There is a very low gender wage gap on labour market entry. The gap widens gradually but significantly from the late 20s and early 30s, driven by the fact that men’s wages grow rapidly at this point, whereas women’s stagnate.

Figure 2. Mean hourly wages across the life cycle by gender and education

Source: LFS data presented in (Costa Dias and others, 2018)

2.1.2 Parenthood leads to a rapid increase in the gender wage gap

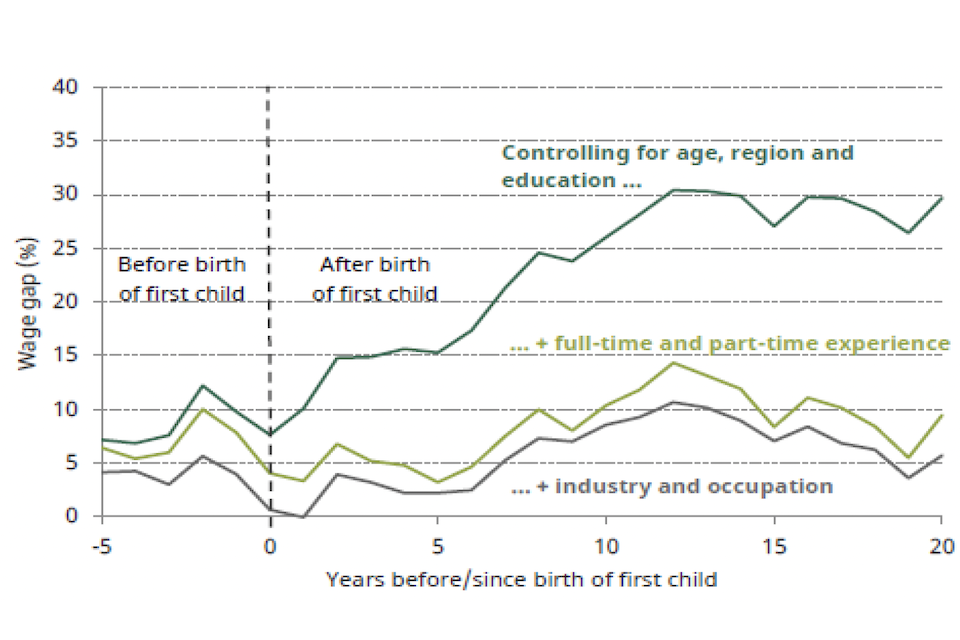

Using the same data, Costa Dias and others (2018) model gender differences in wage progression in years since the birth of the first child, including controls for industry and occupation and differences in full and part-time labour market experience (Figure 3). They find that a substantial wage gap exists before childbirth (about 10% overall and slightly less when industry and occupation are taken into account), but that the gap increases rapidly after the birth of a woman’s first child.

Figure 3. Gender wage gap by time to/since birth of first child, controlling for association between wages and other characteristics

Source: BHPS 1991 to x2008 and Understanding Society 2009 to 2015 presented in (Costa Dias and others, 2018)

2.1.3 Parenthood leads to part-time work for women and part-time work shuts down wage progression

As demonstrated by Figure 3, gender differences in full and part-time experience account for a large amount of the gender differences in wage progression– contributing far more than industry and occupation.

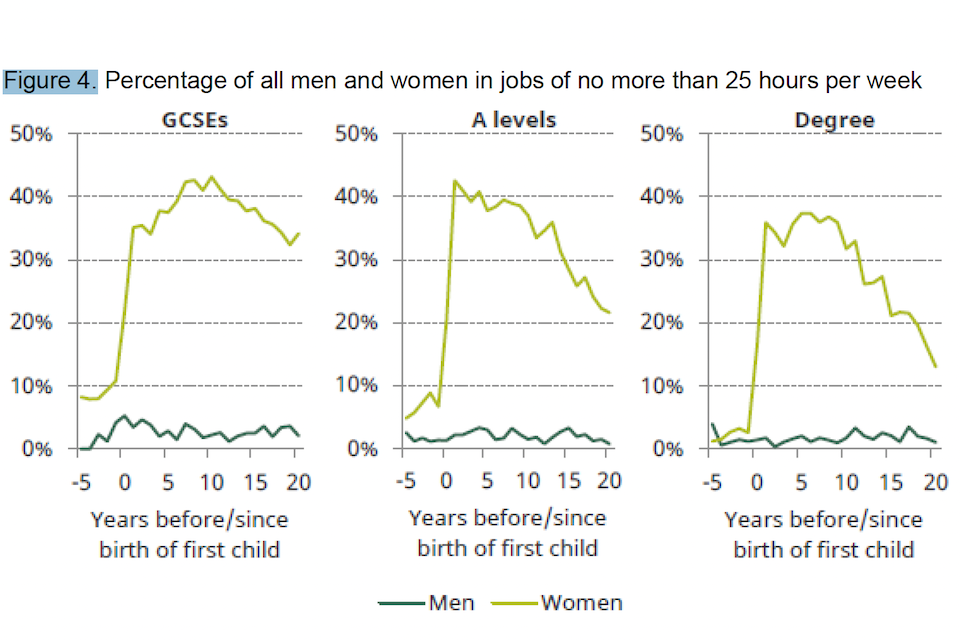

Figure 4 shows how the percentage of men and women working in part-time jobs (less than 25 hours) changes in the period around the birth of the first child. Prior to parenthood, there are only small differences in the rates of part-time work among men and women. When the first child arrives, a large proportion of women transition to part-time work, while there is barely any effect on men’s working patterns. Women with less education are more likely to persist in part-time work as their child grows up.

Figure 4. Percentage of all men and women in jobs of no more than 25 hours per week

Source: BHPS 1991 to 2008 and Understanding Society 2009 to 2015 presented in (Costa Dias and others, 2018)

Costa Dias and others’ analysis suggests that part-time workers are significantly disadvantaged with regards to wage progression compared to full-time workers. This disadvantage goes over and above what one might expect if part-time work offered pro rata the same return on experience as full-time work. While the average full-time worker would expect to see wage growth year on year due to her increased experience, they find that part-time workers experience virtually no growth.

Gender differences in rates of part-time and full-time work account for about half of the widening of the gender wage gap in the first 20 years of a family’s first child’s life.

Greater opportunity costs for highly educated women

Part-time working shuts down wage progression for women, regardless of education level but, because highly educated women would have seen the most wage progression if they remained in full-time work, this effect has a larger impact on highly educated women’s wage growth. A graduate who had worked for 7 years before childbirth would, on average, have seen her hourly wage rise by 6% from an additional year of full-time experience, compared to 3% for a woman with a GCSE level education. However, switching to part-time work would, on average, lead to negligible progression for both (Costa Dias and others, 2018).

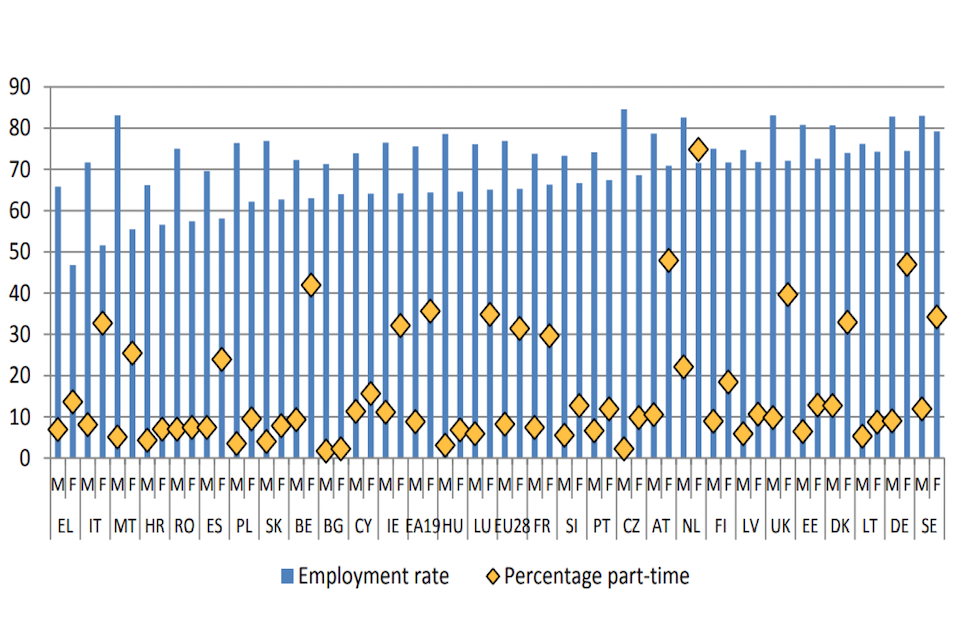

The UK has one of the highest rates of part-time work in the EU

The UK labour market is characterised by a high proportion of women working part-time. As shown by Figure 5, among European countries the UK has one of the highest proportions of female part-time workers as a share of its total working female population.

Figure 5. Employment rate of the population aged 20 to 64 and percentage of part-time workers by gender in 2016

Source: Eurostat, LFS presented in (European Commission, 2017)

2.1.4 Women report higher work intensities while receiving lower wage growth

If men experience higher wage growth than women in the same occupation, then perhaps women are compensated by having lower work intensities. Lindley’s (2016) analysis of national data from the Skills Employment Survey finds that the opposite is, in fact, the case - women report higher work intensities – working at high speed – than men in the same occupation, while simultaneously seeing lower pay growth. These differences are insignificant on labour market entry but emerge subsequently.

This suggests that the relatively slow growth in female wages compared to male wages within the same occupation is not compensated by women having lower work intensities, and conversely that working very hard and working at high speed are not associated with compensation by higher pay.

2.1.5 A significant portion of the gender gap in wage progression remains unexplained

While gender differences in the accumulation of experience and other forms of human capital are able to account for some of the gender gap in wage progression, a substantial amount remains unexplained.

Manning and Swaffield (2008) consider not only human capital explanations of the gender gap in progression – including gender differences in occupation, training, labour market participation, and part-time work - but also explanations based on gender differences in job mobility or psychological attitudes – for example, towards risk taking, competition and self-esteem. They find that, of the overall wage gap observed 10 years after labour market entry, human capital explanations can explain about half, and differences in job mobility and psychological explanations only a small amount. A large gap remains meaning that ‘although men and women have similar earnings when entering the labour market, the women will be something like 8% behind the men 10 years later even if they have been in continuous full-time employment, have had no children, do not want any and have the same personality as a man.’ (p.1018)

Using more up to date data Costa Dias and others (2018) similarly report that ‘by the time the first-born child is 20, the difference in the hourly wages between men and women is about 30%. Of that gap, around one-quarter already existed when the first child arrived. Of the remaining three-quarters around half is due to factors other than the differences in rates of part-time and full-time paid employment after childbirth.’ (p.3)

As demonstrated in Figure 3 differences in occupation and industry are only able to account for a small amount of this gap.

2.1.6 The differences appear to be within firms rather than between them

One candidate factor to explain the remaining difference in wage growth between men and women is that women and men are likely to be sorted into more or less productive firms. If men tend to work in more productive firms then this might account for some of their higher wage growth (Costa Dias and others, 2018). Using linked employer-employee data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings 2002 to 2016, Jewell and others (2019) ask whether the gender wage gap is driven by the sorting of men and women into different firms (and therefore the relative wage premiums that certain firms pay), after controlling for occupations, tenure and other influencing factors. They find that only a tiny fraction of the gender wage gap can be attributed to the allocation of men and women between different firms and occupations, concluding that ‘the clear majority of what explains the pay gap shows up within firms.’ (p.17)

2.2 The gender divide in occupational attainment

An alternative method of measuring for career progression is provided by Bukodi and others (2012). They construct a vertical ranking of occupations by first coding all occupations in an individual’s history against the 1990 Standard Occupational Coding frame (SOC90). This provides 77 occupational codes which they rank according to the average hourly pay within that occupation. Finally, they convert the ranking into scores between 1 and 100 which represent the relative positions of that occupation within the occupational distribution.

2.2.1 Men reach higher levels of occupational attainment than women, but the gap has narrowed over time

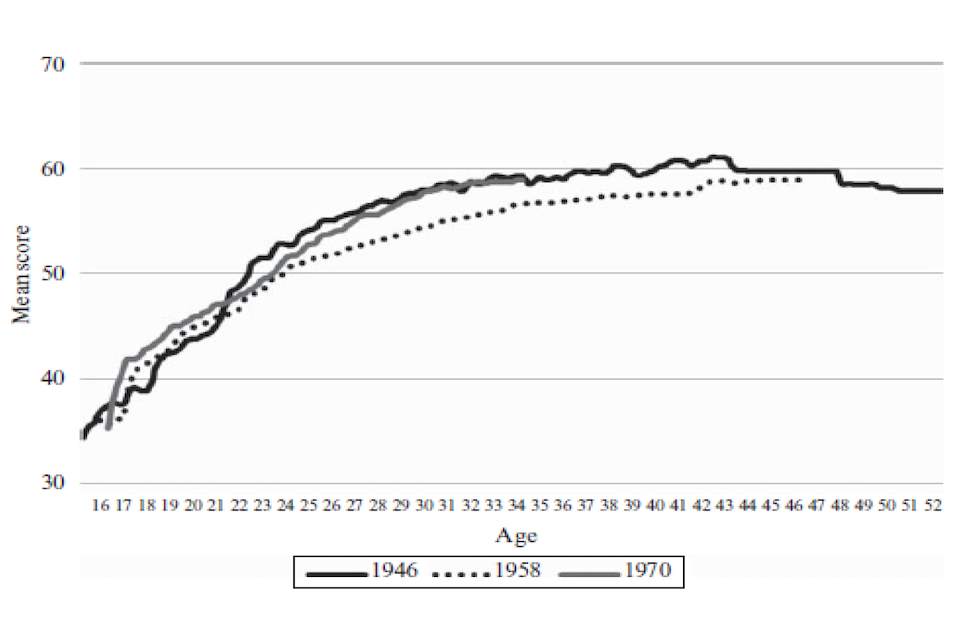

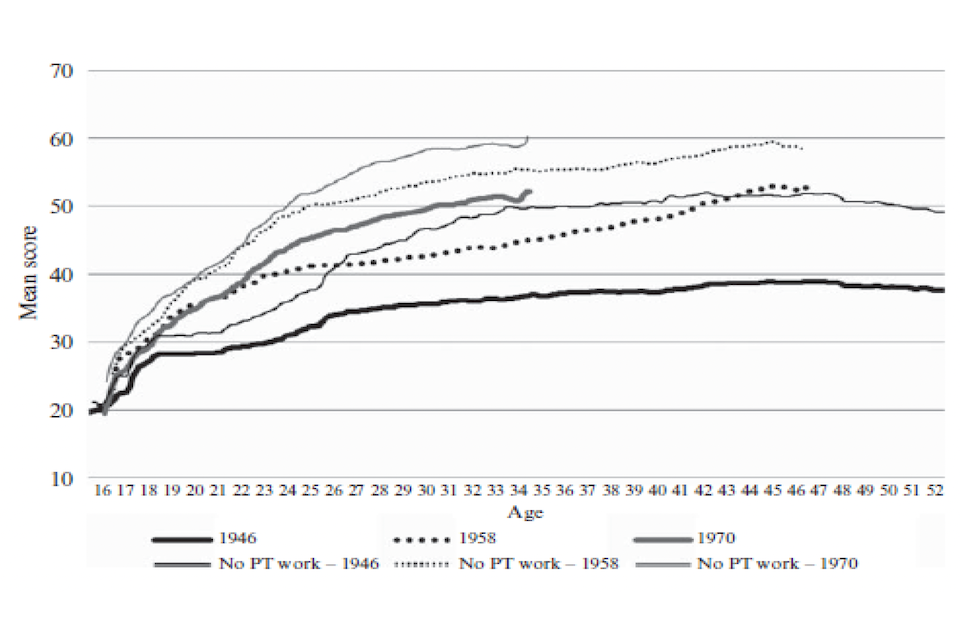

Using the ranking system described above, Bukodi and others (2012) compare the occupational mobility of men and women across 3 different birth cohorts - 1946, 1958 and 1970. Figure 6 shows the career progression over the life course for all men and Figure 7 shows the same for all women, and for those women who never worked part-time. They find that men reach higher levels of attainment than women in each cohort but that the divide has narrowed over time.

Figure 6. Men’s mean occupational earnings scores across age by cohort

Source: Bukodi and others (2012)

Figure 7. Women’s mean occupational earnings scores across age by cohort

Source: Bukodi and others (2012)

2.2.2 Part-time work is an important explanation of the differences between men and women in occupational attainment

Figure 7 demonstrates that women’s part-time work is an important explanation of the remaining gender differences in occupational attainment. Among the cohort born in the 1970s, women who had never worked part-time reach career levels very similar to men.

2.2.3 Badly paid jobs are sticky floors for women, springboards for men

Using the same vertical occupational scale, Bukodi and others (2012) analyse how first job on labour market entry affects later occupational attainment. They ask whether workers who enter the labour market in the lowest occupational level are able to use their initial job as a springboard into a better paid job, or whether they remain stuck in sticky floors. Their findings suggest that bad jobs are springboards for men, but sticky floors for women. While, initially, men and women move out of the lowest occupational category at similar rates, thereafter their trajectories differ. Men are more likely to experience a steady upward trajectory, whereas women’s trajectories stall and they are much more likely than men to experience subsequent downward mobility back to their original level.

Stewart (2009) similarly finds that single mothers who enter low-skilled employment experience very slow wage progression. While many leave employment again, those who remain rarely progress beyond low pay, suggesting that more needs to be done to foster wage progression among low paid workers.

The sticky floor/springboard gender divide has worsened over time

While Bukodi and others (2012) find that, overall, women’s occupational attainment has become more similar to men’s over time, this gender divide between springboards for men and sticky floors for women has deepened. They attribute this to an increasing polarisation of employment and occupational structures coupled with uncertainties about labour market conditions. Qualitative work explored further in Sections 3.3 to 3.4 suggests that some of this stickiness can be attributed to structural barriers to progression for women with caring responsibilities, including the demand for geographic mobility or longer working hours at higher occupational levels (Rainbird, 2007).

3. Barriers and facilitators

This section is based on evidence from 100 studies which were located in response to objective 2 (see appendix for a full outline of the search strategy). The search was limited to studies carried out in the UK and all relevant study designs were considered. Initial searches were limited to studies published after 2000. This produced a large number of relevant results and so those published post-2010, or those focusing on under-studied groups were prioritised.

The evidence that this section is based on is largely qualitative, drawn from interviews or ethnographies. Collectively, it provides the perspectives of hundreds of women and their colleagues from a diverse range of occupations and sectors. It thus helps to contextualise the national data set out in Section 2, providing an insight into the processes which create and sustain the observed differences in progression.

While it is difficult for qualitative studies to definitively prove cause and effect, or to generalise from findings observed in one firm or sector to another it provides an overview of the sorts of barriers that employers might encounter. Where pertinent, we have indicated the context from which the study was drawn. Where the source evidence permits, we also note where any barriers interact with other dimensions of identify such as ethnicity and class.

This section presents the findings from those studies. Section 3.1 explores organisational processes, Section 3.2 looks at organisational cultures, Section 3.3 explores the challenges of reconciling caring responsibilities with current working practices and 3.4 sets out the current difficulties of combining alternative working practices with career progression.

3.1 Organisational processes for progression that open up space for bias

This section provides an overview of how the organisational processes which govern workplace progression either generate gender differences or increase the likelihood that such differences will arise.

Women are disadvantaged by organisations which lack formality and transparency with regards to the criteria for recruitment, promotion or pay negotiation (3.1.1). In the absence of such criteria decisions on pay and promotion are more likely to be made via a process of social cloning, whereby those in a position of power champion those like them (3.1.2). In both informal and formal environments progression often happens via male-dominated social networks which women find difficult to access (3.1.3). The presence of an organisational sponsor was identified as a key facilitator to overcome some of these barriers (3.1.4).

3.1.1 Informality and lack of transparency leaves the way open for progression via processes that disadvantage women

Informality and an associated lack of transparency with regards to the criteria for recruitment, promotion or pay negotiation were identified as key organisational barriers to gender equality. As will be explored in the following sections, in the absence of clear systems advancement to more senior roles and higher pay grades can occur via processes that disadvantage women.

This barrier was located both in research on specific professions and sectors, including television (Leung and others, 2015), law (Tomlinson and others, 2013) and academia (Burkinshaw and others, 2018), as well as in more wide-ranging studies. In Corby and Stanworth’s (2009) study of 80 working women employed in 40 organisations, they find that nearly every private sector organisation lacked a structured pay system and, consequently, pay was determined opaquely, often by reference to what an individual had earned previously. This opacity, combined with an institutional culture that mandated against discussing pay with colleagues, left women with no way of knowing whether they were being paid the same as comparatively employed men.

Knowledge workers – those who (like lawyers, academics or television professionals) are required to ‘think for a living’, may be particularly likely to be exposed to this sort of informality, as employers seek ‘someone they can trust’ and where that trust is established in advance via contacts and reputation (Eikhof and Warhurst, 2013, Leung and others, 2015). Eikhof and Warhurst (2013) argue that, in certain industries, such as the television and wider creative industries, informality is not accidental, but a central part of a flexible, project-based model of production in which the majority of staff are freelancers, and recruitment and advancement happen primarily via personal networks. This increases the likelihood of advancement via social cloning, which is explored further in the next section.

3.1.2 Women are disadvantaged when those in positions of power seek those who look like themselves

Studies in the financial services sector (Atkinson, 2011), academia (White and others, 2012; Bagilhole, 2016; Shepherd, 2017) and among consultants (Kumra, 2010) identify occasions when promotion happens via a process of social cloning, whereby those in positions of authority seek to champion and promote those who are similar to themselves. This similarity can take many forms, including in terms of career path (White and others, 2012) or styles of leadership (Kumra, 2010; White and others, 2012). Given the male dominated nature of the senior ranks of many organisations, this puts women at a disadvantage, since women are less likely to possess, or be seen to possess, the relevant qualifications of the archetypal candidate.

This process of social cloning is made easier in informal systems where hiring and promotion are done by networks, or via trust relationships based on “affect and tacit judgements such as ‘he’s a good bloke’”(Leung and others, 2015).

Women are expected to fulfil a male-centred definition of merit, but may be penalised when they do

Perhaps unsurprisingly in these contexts, women report perceiving that they need to ‘behave like men to get on’ – to meet the qualifications of the archetypal candidate, which is defined by relationship to a male-centred definition of merit (Tomlinson and others, 2013; Charles, 2014; Woodfield, 2016). This is especially the case in environments (such as politics) where success, or occupational identity are closely tied to an ‘an aggressive, confrontational masculinity’ (Charles, 2014), but interestingly was also found in studies of feminized professions such as teaching, where headship was seen as requiring ‘tough and coercive’ qualities, something that was felt to be anathema to the female teachers (Smith, 2011a).

Peters and others (2017) investigate how this (lack of) fit between women’s perceptions of their own attributes and those of a successful leader affect their ambition and intention to persist in a career. They asked 62 female police officers to rate themselves on a series of character traits, while also asking them to rate how senior officers fared on those same traits. They found that, on average, female officers rated a mismatch between their own character traits (for example, collaborative and sociable) and those of senior officers (decisive, assertive, arrogant). This lack of fit was a significant predictor of a reduced level of ambition and higher propensity to exit the workforce.

There was some evidence from British organisations, too, of a well-documented concept from social psychology – the double bind. Women are seen as lacking the agentic qualities needed to be good leaders, but are penalised by others when they do, since these contradict the expected feminine qualities of warmth and helpfulness (Carli and Eagly, 2016). A study of female IT workers found that women perceived that when they demonstrated agentic traits modelled by their managers, such as being ‘forthright’, this was unfavourably received (Kirton and Robertson, 2018).

As will be explored further in Section 3.3.1, in some cases behaving like men means minimizing the visibility of family life (Tomlinson and others, 2013). For the black and ethnic minority lawyers interviewed by Tomlinson and others (2013) it also meant playing down other differences, such as by avoiding involvement in BME networks.

Work typically done by women can be devalued in terms of career capital

When progression is linked to social cloning the work that is typically associated with men is related to higher career capital. Conversely, work that is typically associated with women is devalued in terms of future returns on career progression. So that, for example, female academics reported higher levels of teaching and pastoral care for their students, activities that contributed little towards status and future promotion (Bagilhole, 2016). Similarly, the women working in trade unions studied by Guillaume and Pochic (2011) were over-represented in certain types of role where they were responsible for social activities, equalities or health and safety, while the roles typically held by men, such as grievance handling or contract negotiation were seen as being the most prestigious.

In some studies women reported being pushed towards or held in devalued roles by colleagues who perceived them as fitting with their gender-stereotypical skillsets (Moreau and others, 2007; Scholarios and Taylor, 2010; Bagilhole, 2016; Kirton and Robertson, 2018). In one study of call- centre workers the call-centre managers described female workers as being better at dealing with difficult customers. The researchers observed that this meant they were less likely than their male peers to be moved from customer-facing roles to more challenging or specialised positions (Scholarios and Taylor, 2010). Similarly female IT workers described being assigned to roles that involved ‘nagging the men’ to meet project deadlines, while a male manager in the same organisation described valuing his female staff’s ability to stop men from ‘taking lumps out of each other’ (Kirton and Robertson, 2018). In these situations ‘feminine skills end up being a catch-22 for women’ (Kirton and Robertson, 2018), in so far as they lead women to be herded into internal roles that offer lower career capital.

3.1.3 Women are disadvantaged when progression happens via social networks, which they find difficult to access

A large number of studies identified the key power that networks play in determining career advancement, along with women’s relative lack of access to these networks, as barrier to women’s career advancement (Miller and Clark, 2008; Tonge, 2008; Kumra, 2010; Pritchard, 2010; Atkinson, 2011; White and others, 2012; Eikhof and Warhurst, 2013; Tomlinson and others, 2013; Cahusac and Kanji, 2014; Wilson, 2014; Savigny, 2014; Leung and others, 2015; Bagilhole, 2016; Wright, 2016; Burkinshaw and others, 2018; Kirton and Robertson, 2018). Networks play a role not just in deciding pay and promotion but in allocating work assignments (Fearfull and Kamenou, 2006) which may play an important role in the build-up of subsequent career capital and, therefore, later progression.

Promotion via ‘grace and favour appointments’ (Burkinshaw and others, 2018) or based on ‘who you know’ (Wilson, 2014) is problematic, since women find it harder to gain access to the relevant male-dominated networks (Wilson, 2014), with ethnic minority women facing an additional hurdle of gaining access to primarily white networks (Fearfull and Kamenou, 2006).

Women can also be excluded due to the nature or location of the networking activity – for example, networking organised around sporting events (Tomlinson and others, 2013; Wilson, 2014) – or being held in a club ‘which still has rooms that women aren’t even allowed in’ (Tomlinson and others, 2013, p. 255). Timing is also a key issue, with the requirement for socialising and networking in the evening after already long working hours a barrier to those with caring responsibilities (Tonge, 2008; Pritchard, 2010; Atkinson, 2011; Cahusac and Kanji, 2014; Leung and others, 2015).

In some industries career networking is tied up with geographic mobility – for example, academic conferences – which similarly poses difficulties for those with caring responsibilities (Pritchard, 2010). Networking events centred around drinking were cited as challenging for some of the Muslim lawyers interviewed by (Tomlinson and others, 2013).

Networks may play an especially important role in informal environments which lack clear standards for career or pay progression and where the lack of transparency considerably obscures the proverbial ‘old boys networks’ (Eikhof and Warhurst, 2013). However, networks may also be used to make decisions about pay and promotion in contradiction of formal procedures (Kirton and Robertson, 2018). In certain occupations, such as law, extensive networking is a necessary pre-cursor to ‘rainmaking’ – bringing in and effectively managing the client relationships that are a key criterion for promotion (Tomlinson and others, 2013).

While the majority of studies that identified this barrier focused on professional women, a study of women working in the construction industry found similarly that in manual trades networks are sites of information exchange, important for the gaining of new skills and progression (Wright, 2016).

3.1.4 A champion or mentor can counteract some of this disadvantage

In some of the studies we located, women described how they had benefited from informal mentorship by senior figures within their own organisation, both female (Guillaume and Pochic, 2011; Norman, 2014) and male (White and others, 2012). Within these studies the description of the mentoring relationship went beyond providing advice to actively sponsoring their careers and was, in some cases, specifically designed to counter some of the effects of social cloning described in the preceding sections.

3.2 Hostile or isolating organisational cultures

This section looks at barriers that can arise for women working certain organisational cultures including isolation and lack of role models (3.2.1) and sexism and sexual harassment (3.2.2). Support networks are helpful for easing isolation (3.2.3).

3.2.1 Isolation and lack of role models can lead to a lack of confidence

Within male-dominated organisational cultures such as construction and sports coaching, social isolation was a problem for female study participants (Norman, 2014; Worrall and others, 2010). In some cases this was cited as leading to a lack of confidence that caused women to self-select out of working towards more senior roles (Norman, 2014).

3.2.2 Sexism, sexual harassment and bullying

A more severe issue associated with male-dominated organisational cultures was that of sexism and, in many cases, sexual harassment and bullying. Women working in construction (Worrall and others, 2010), finance (Wilson, 2014), retail managers (Broadbridge, 2007) and as pilots (McCarthy and others, 2015) described cultures in which sexist assessments of their competence from co-workers or clients affected self-esteem and their ability to progress. Fearfull and Kamenou (2006) and Umolu (2014) both note that, for ethnic minority women, racist or religious stereotypes sit alongside gender stereotypes so that, for example, a manager of Nigerian descent described being mistaken for the caterer (Umolu, 2014).

At the more extreme ends were cultures in which sexual harassment was common, with respondents feeling they had to turn a blind eye (Tomlinson and others, 2013) or even where the viewing of pornography at work and corporate entertaining involving the sex industry was part of organisational culture (Atkinson, 2011). Corby and Stanworth (2009) found that while some women had exited organisations in situations where bullying and sexual harassment had become intolerable, much more common was a resigned acceptance – ‘In short, they considered that a woman-hostile culture was a price worth paying for working in a predominantly male environment, especially where they were able to progress into managerial roles.’ (ibid, p.175)

3.2.3 Support networks can help in easing isolation

Some studies described the importance of wider support networks of colleagues for either easing the isolation felt within male-dominated working cultures (Wright, 2016; Papafilippou and Bentley, 2017) or providing emotional support in professions (such as medicine) where burn-out is common (Walsh, 2012).

3.3 Conflicts between external responsibilities and current models of working

As is suggested by the findings in Section 2, the majority of our studies cited the conflict between current models of working and caring responsibilities as being a significant barrier to women’s progression. This section explores the conflict in more detail.

Women continue to take on disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care – three-quarters of mothers say they have primary responsibility for childcare in the home, and women make up 58% of carers for the old or disabled (Women and Equalities Committee, 2016). Time use data from 2000 and 2015 analysed by the ONS finds that, while fathers with pre-school children are increasing the time they spend on care, mothers provided 74% of total childcare time in 2015 (ONS, 2017). Women also continue to perform the majority of housework (Wheatley and Wu, 2014). Ethnic minority women may face additional hurdles as work-life difficulties can be accentuated by cultural and religious expectations (Kamenou, 2008).

Working hours in the UK are long. On average, full-time employees in the UK work 42.3 hours per week, the highest number in the EU, against an Europe wide average of 40.3 (Eurostat, 2018).

Women’s progression and labour market participation is jeopardised not only by their inability to work long hours, but also by their partner’s long hours. Research with longitudinal data from the USA finds that having a partner who works long hours significantly increases a woman’s likelihood of leaving the labour market, although the reverse is not true (Cha, 2010). Analysis of BHPS data from the UK finds that women report greater levels of dissatisfaction with performing unpaid care and housework when the uneven division is linked to long working hours in their partners (Wheatley and Wu, 2014).

There is still evidence of direct discrimination against women with caring responsibilities (Section 3.3.1). However, more commonly we found evidence of prevailing organisational norms of overwork and expectations of constant availability as a proxy for commitment and merit. In many cases this expectation of constant availability stems not from the nature of work but from specific working practices and ideas of what makes a ‘committed worker’ (3.3.2). Unpredictable work demands linked to casualised forms of labour also pose a challenge for those with caring responsibilities (3.3.3) as do demands for geographic mobility in order to progress (3.3.4). Women find it hard to access training opportunities if they conflict (or are perceived to conflict) with caring responsibilities (3.3.5). Women’s working hours are affected by levels of pay and the UK’s high childcare costs (3.3.6) Access to childcare, alternative ways of working, flexible partners and changes to working time norms were found to be facilitators (3.3.7).

3.3.1 There is still evidence of direct discrimination against women with children regarding promotions

In a number of studies women described having to play down their caring responsibilities in order to avoid stigmatisation (Callan, 2007; Kumra, 2010; Tomlinson and others, 2013; Cahusac and Kanji, 2014). As one consultant put it ‘I think it’s definitely a requirement to show great commitment to the firm, which means not having children or, if you do have children, keeping extremely quiet about that.’ (Kumra, 2010, p. 235).

Examples of direct discrimination against women with caring responsibility were also cited, including claims that women were classed as less of an asset if they had children, and subsequently passed over for promotion (Walsh, 2012), or women being told they would not be offered a promotion as their children meant they were unable to be likely to leave and seek a better offer elsewhere (Savigny, 2014).

3.3.2 Women are disadvantaged where progression is linked to overwork and presenteeism

Much more common than direct discrimination, and the dominant theme in the studies we located, was of a conflict between organisational norms of overwork and boundless availability, and caring responsibilities (Dean, 2007; Moreau and others, 2007; Lyonette and Crompton, 2008; Miller and Clark, 2008; Corby and Stanworth, 2009; Broadbridge, 2010; Kumra, 2010; Scholarios and Taylor, 2010; Tomlinson and Durbin, 2010a; Vinnicombe and others, 2010; Worrall and others, 2010; Ford and Collinson, 2011; Ozbilgin and others, 2011; Smith and Elliott, 2012; Walsh, 2012; Tomlinson and others, 2013; Wattis and James, 2013; Cahusac and Kanji, 2014; Michielsens and others, 2014; Charlesworth and others, 2015; Jefferson and others, 2015; Munro and others, 2015; Papafilippou and Bentley, 2017; Budjanovcanin, 2018; Kirton and Robertson, 2018). Although the majority of these studies focused on professional and managerial occupations, similar themes were also found in studies of low-income parents (Dean, 2007), call-centre workers (Scholarios and Taylor, 2010), retail shop managers (Smith and Elliott, 2012) and service industry workers (Tomlinson, 2007).

In many cases ‘all hours working cultures’ (Ozbilgin and others, 2011) were bound up with occupational identities, so that succeeding in that occupation was seen as fundamentally at odds with outside caring responsibilities. This was demonstrated through the widespread acceptance of (un)spoken professional codes of conduct such as ‘the firm expected all or nothing’ (Vinnicombe and others, 2010, p. 180), ‘patients first, family second’ (Ozbilgin and others, 2011, p. 1591) or ‘paid care work trumps unpaid care work’ (Charlesworth and others, 2015, p. 608).

Conversely, anything less than ‘maximum flexibility’ - always being available for the organisation and the client, customer, patient, or the service user - is seen as demonstrating a lack of commitment either to the organisation or to one’s career (Kumra, 2010; Ozbilgin and others, 2011; Walsh, 2012; Tomlinson and others, 2013; Michielsens and others, 2014; Charlesworth and others, 2015; Jefferson and others, 2015; Munro and others, 2015; Kirton and Robertson, 2018).

Long working hours were viewed critically by the authors and subjects of the studies as being less down to the demands of the work than a proxy for commitment and merit. As such, in many workplaces opportunities for promotion are equated with the ability to demonstrate this unrestricted availability, and a culture of presenteeism (Tomlinson, 2007; Lyonette and Crompton, 2008; Corby and Stanworth, 2009; Atkinson, 2011; Crompton and Lyonette, 2011; Guillaume and Pochic, 2011; Tomlinson and others, 2013; Papafilippou and Bentley, 2017).

In other occupations, such as teaching or public sector management, excessively long hours were linked less with organisational pressures of presenteeism and more with an excess workload linked to the re-organisation of work around the principles of managerialism and modernization (Miller, 2009; Conley and Jenkins, 2011; Burkinshaw and others, 2018). In these workplaces top-down targets created an unbearable workload.

Although, in these examples, both male and female employees were subject to the same pressures, the fact that women continue to carry out the majority of unpaid care reduces their ability to work the long hours in evenings and weekends necessary to complete the work.

The pressure to work excessively long hours is linked with unsupportive line managers, not only in professional jobs in the private sector (Kirton and Robertson, 2018), but also in organisations in the public and voluntary sectors who ostensibly subscribe to work-life balance ideals and offer lower remuneration (Dean, 2007). Managers who failed to understand caring responsibilities expected workers to be able to cope with unexpected and spontaneous demands on their time (Wattis and James, 2013). In some cases superficially supportive line managers expressed sympathy with the difficulty that the conflict between caring responsibilities and long hours/maximum flexibility organisational culture created for women, but did not perceive a personal responsibility to find a solution (Kirton and Robertson, 2018). In this view the conflict between caring and work was a wider societal one, and not something produced by a certain and specific way of organising work.

3.3.3 Women are disadvantaged by unpredictable work demands

For some workers, particularly the low-paid, the unpredictability of work demands is built into their contracts of employment. Indeed, lower level workers are the group with the least autonomy over work time (Warren and Lyonette, 2018). In the last quarter of 2017 901,000 people were estimated to be on a zero-hour contract – 55% of these people are women. In total 2.7% of women in employment are on zero hours contracts (De Henau and others, 2018).

TUC research with zero-hours workers found that 51% have had shifts cancelled at less than 24 hours’ notice, and 73% had been offered work at less than 24 hours’ notice (Trades Union Congress, 2017), making it extremely difficult to make childcare arrangements. This precarity was borne out in the qualitative studies of low-paid retail workers and of retail store managers who had demands made on their time at short notice (Backett-Milburn and others, 2008; Smith and Elliott, 2012), while the complex and changing shift patterns of call centre workers lead to interference with family life (Scholarios and Taylor, 2010). Many respondents in Backett-Milburn and others’ (2008) study of low-paid women working in food retail commented that, were it not for the support of family members providing childcare, they would be unable to afford to continue working in their jobs.

Precarity of work and the unpredictability of hours also extend to freelance and contract workers. This was particularly notable in the television industry where women with children described the impossibility of obtaining childcare due to the unpredictable flow of work. This may go some way towards explaining the low retention rate of women in the film and television industries (Leung and others, 2015). In academia, where the use of short-term contracts is increasingly common, some women felt it necessary to delay pregnancy until they had secured a permanent contract (Pritchard, 2010).

3.3.4 Women are disadvantaged by the need for geographic mobility to progress

In a number of careers, constant geographic mobility is either a requirement of the job – for example, pilots, (McCarthy and others, 2015), politicians (Charles, 2014) – or key in building up the required career capital for progression – for example, academics (Shepherd, 2017; Miller-Friedmann and others, 2018) – and is difficult for those with domestic and caring responsibilities. This is not just an issue for professional women.

Harris et al (2007) found that the requirement for managers to transfer to another store meant that career progression would have caused problems for part-time working retail shop floor staff, for whom proximity to home and childcare are major considerations.

3.3.5 Women are disadvantaged when training opportunities are inaccessible to those with caring responsibilities

Some women reported difficulty in accessing training and development opportunities. Sometimes this took the form of direct bias. Women reported that comparable men were encouraged to attend training courses with a view to promotion, whilst they were unable to access them (Atkinson, 2011). In other cases, managers perceived development programmes as being too demanding for women with families (Kirton and Robertson, 2018). Despite the 2000 EU Part-Time work directive giving part-time workers the right to equal treatment, there was some evidence of part-time workers being denied access to training opportunities (Tomlinson, 2007).

In other cases, female workers were unable to take up training and development opportunities due the necessity to participate outside of (already long) working hours, creating a conflict with caring responsibilities (Kirton and Robertson, 2018). Part-time workers described being expected to attend training events held at times when they were not working, or in locations that presented additional family commitment issues (Harris and others, 2007).

3.3.6 High childcare costs mean that the ability to outsource care work is strongly linked to pay

In contrast to many EU and OECD countries the majority of childcare in the UK is provided by the private sector, and costs are high (Lyonette, 2015; ONS, 2018). In 2019, the average cost of childcare in a nursery for a child under 2 was £127 for 25 hours a week (£6,600 a year) and £242 for 50 hours a week (£12,600 a year) (Coleman and Cottell, 2019).

Due to the high cost of childcare in the UK the ability to reconcile work and caring responsibilities by outsourcing care work is dependent on pay. In a study by Charlesworth and others (2015) among relatively low paid social service workers, both workers and managers cited the low pay as a reason why those with caring responsibilities were unable to ‘afford’ to work in social services.

Backett-Milburn and others’ (2008) study of low paid women working in food retail produced similar findings, with many women commenting that, were it not for the support of family members providing childcare, they would be unable to afford to continue working in their jobs.

As a result of this, lower paid women with pre-school children are more likely than other women to reduce their hours of work, whilst simultaneously relying on informal provision of care from relatives (Lyonette, 2015). The 2018 Childcare and Early Years Survey of Parents in England reported that among mothers working part-time, almost a third (30%) said they would increase their hours if there were no barriers to doing so, while just over half of non-working mothers said that if they could access good quality childcare which was convenient, reliable and affordable, they would prefer to go out to work (Department for Education, 2018a).

As previously noted, the UK has one of the highest proportions of female part-time workers as a share of its total working female population (Eurostat, 2018). Recent evaluations of the extension of the early years entitlement in England, from 15 hours to 30 hours a week for 38 weeks of the year for 3 and 4 year olds with working parents, indicate that reforms to increase the affordability of childcare have a positive relationship to the number of hours that mothers work: over a quarter (26%) of mothers reported that they had increased their work hours since receiving the extended hours, with the proportion reporting impacts on parental work greater for families in the lower income group than for those in the higher income group (Department for Education, 2018b).

3.3.7 Facilitators

Changes in working time norms can reduce the conflict between work and caring responsibilities

Although rare we did find one example of a top-down commitment to gender equality leading to a change in working time norms. Charles (2014)’s study of the National Assembly for Wales described how a support for positive measures meant that the Assembly now sits only during school term time, its plenary sessions finish by 17.30, and Assembly members are only expected to be present 3 days a week.

Access to alternative ways of working are key in reconciling work and caring responsibilities

Studies frequently cited the availability and acceptability of part-time work and flexible work as key in enabling women to reconcile work and caring responsibilities (Broadbridge and Parsons, 2005; Backett-Milburn and others, 2008; Carmichael and others, 2008; Miller and Clark, 2008; Walsh, 2012; Wattis and James, 2013; Woolnough and Redshaw, 2016). Studies among low-paid workers in particular mentioned the flexibility to fit work around childcare responsibilities as a key factor in their employment choices (Backett-Milburn and others, 2008; Broadbridge and Parsons, 2005), although it is essential to make a distinction between employee-driven flexibility, where workers are able to organise work around caring responsibilities, and precarious employer-driven flexibility which leads to interference with family life (Backett-Milburn and others, 2008; Scholarios and Taylor, 2010; Smith and Elliott, 2012).

For professional women access to part-time or flexible work was cited as a factor in enabling their retention in the workplace (Wattis and James, 2013; Woolnough and Redshaw, 2016). As is explored further in Sections 3.4.4 to 3.4.5 the evidence suggests that alternative ways of working currently play a bigger role in enabling women’s retention in the workplace than their progression.

Flexible partners help in reconciling work and caring responsibilities

Both men and women mentioned a flexible partner as important in helping them to reconcile work and family life. Professional men described the support they received from ‘understanding wives’ (Jefferson and others, 2015; Kirton and Robertson, 2018). Equally female respondents in the study cited supportive partners, and especially partners who worked part-time or flexibly as key in enabling their progression (Lyonette and Crompton, 2008; Woolnough and Redshaw, 2016).

Access to childcare

Access to childcare is an essential factor enabling women to combine work and caring responsibilities. Due to the high cost of childcare among low paid workers support from family members is important in enabling them to ‘afford’ to work (Backett-Milburn and others, 2008). Among professional mothers, satisfaction with either family support or private nurseries is important in enabling women to combined motherhood with family life (Woolnough and Redshaw, 2016).

3.4 Alternative ways of working do not currently offer parity

Alternative ways of working, including part-time and flexible work, are currently proposed as 2 key solutions to overcome the conflict between current ways of working and caring responsibilities described in the previous section. In 2017, 41% of women in employment were working part-time, compared to 13% of men (ONS, 2019). An increasing number of workers are also making use of flexible working arrangements – a term which encompasses a wide range of arrangements allowing workers to work more flexibly, including flexitime – a worker’s ability to control their schedules, and teleworking – a worker’s ability to choose where to work freely – for example, being able to work from home (Chung, 2017).

This section presents evidence from the literature on access to these alternative ways of working and their relationship to women’s career progression. Access to alternative arrangements is still limited. There continues to be a shortage of quality part-time work and, while there are increasing numbers of part-timers in senior positions, lower-level part-time workers remain crowded into jobs that offer poor wages and restricted opportunities for progression (3.4.1). Similarly, there is some evidence that flexible working policies are predominately offered to high-skilled workers. Under the current law the success of flexible working requests are dependent on an employee’s bargaining positions, meaning they are not available to less ‘valuable’ employees (3.4.2). Sections 3.4 to 3.5 consider the evidence on the effect that taking advantage of alternative ways of working has on career progression. Without changes to underlying organisational cultures, and while such working practices are taken up only by women, they risk embedding gender inequality in contexts where full-time workers are the norm, and part-time and flexible working is seen as signalling a lack of commitment (3.4.3). Clear evidence demonstrates the negative effect of part-time working on career progression (3.4.4) and emerging qualitative evidence suggests that flexible working may similarly have negative consequences (3.4.5). A final consequence of implementing alternative working time policies without changing underlying organizational cultures is that they can lead to an intensification and extensification of work (3.4.6). Alternative working roles models and supportive managers, as well as workplaces that help managers to deal with part-time and flexible workers were found to be facilitators (3.4.7).

3.4.1 Access to quality part-time work is still restricted

There continues to be an issue with the availability and quality of part-time jobs in the UK (Warren and Lyonette, 2018). This can lead to women reducing their hours of employment and, whilst they almost always return to a job with the same occupational status as the one they left, over time this leads to a reduced likelihood of progression at work (Harkness and others, 2019). Harkness et al (2019) found that fewer than 1 in 5 of all new mothers follow a full-time career after maternity leave and, among those who were working full-time prior to childbirth, a majority either stop working or move to part-time work. Five years after childbirth the chance of having occupationally upgraded is far lower for women than men: while 26% of men have moved to a job with a higher occupational status, for women this figure is just 13% (ibid). Using a different measure of occupational downgrading, Dex and Bukodi (2012) find that women at the top-level of the occupational hierarchy and ‘high-flyers’ in male dominated organisations are most at risk of downgrading during the move from full time to part-time work.

This risk of occupational downgrading is greatly reduced if women are able to access part-time work with the same employer (Connolly and Gregory, 2008; Dex and Bukodi, 2012) but their chance of progressing is also lower compared to those who move to a new employer (Harkness and others 2019). Recent cohorts of women having children since the passage of the EU part-time workers directive appear to have benefited from a legislative environment providing greater protection for part-timers and increased flexibility (Bukodi and others, 2012). However, it remains the case that there is a scarcity of senior or ‘quality’ roles available on a part-time basis (Lyonette, 2015), greatly reducing opportunities for part-timers progression.

In some professions, most notably medicine, women segregate into parts of the profession where part-time working is more accessible. The over-representation of women in general practice, and under-representation in hospital medicine is attributable to the high percentage of part-time women in general practice (Taylor and others, 2009). Similarly, Tomlinson et al (2013) find that a significant number of female lawyers migrate towards specialisms such as employment, estates and trusts and family law which offer better work-life balance.

There are widening differences in the quality of part-time work by occupational class

National data examined by Warren and Lyonette (2018) found evidence of widening inequalities in the quality of part-time work by occupational class. There is an increase of part-timers in senior level jobs, and those women are moving closer to their peers in terms of job quality. However, post-recession lower-level part-time workers face enduring disadvantage, crowded into jobs that offer poor wages and restricted opportunities for progression.

This confirms a divide observed by Tomlinson (2006a) between ‘optimal’ and ‘restrictive’ part-time jobs. In her study of mothers working in the hospitality industry she observed that ‘restrictive’ part- time jobs, while providing women some control over their shifts, offered little prospects of promotion. By contrast ‘optimal’ part-time jobs tended to be held by those who had already developed their careers, and thus were in a stronger position to negotiate part-time work and preserve occupational status. This suggests that part-time work can currently contribute more towards maintaining women’s labour market position than towards progression, something explored more in Sections 3.4.4 to 3.4.5.

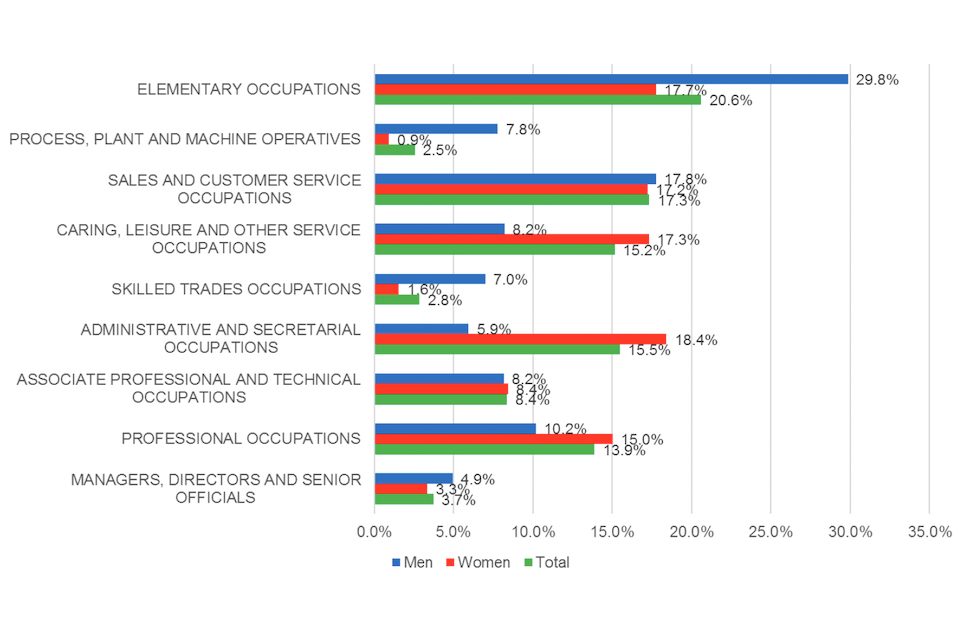

Part-time workers remain concentrated in certain occupations

Research carried out (Tomlinson and others, 2009, 2005) for the Women and Work Commission found that when women transition to part-time work, they crowd into 5 low skill, low pay occupations, ‘the 5 Cs’ - caring, cleaning, clerical, catering and customer service work. Data from the 2018 Labour Force Survey shown in figure 8 confirms that the 5 Cs continue to account for 70% of part- time jobs. While there has been an increase in the number of part-time professional jobs, only 3.7% of managerial workers are part-time.

Figure 8: Occupational distribution of part-time workers

Source: Analysis of LFS by (Tomlinson, 2018)

3.4.2 There is still limited access to flexible working

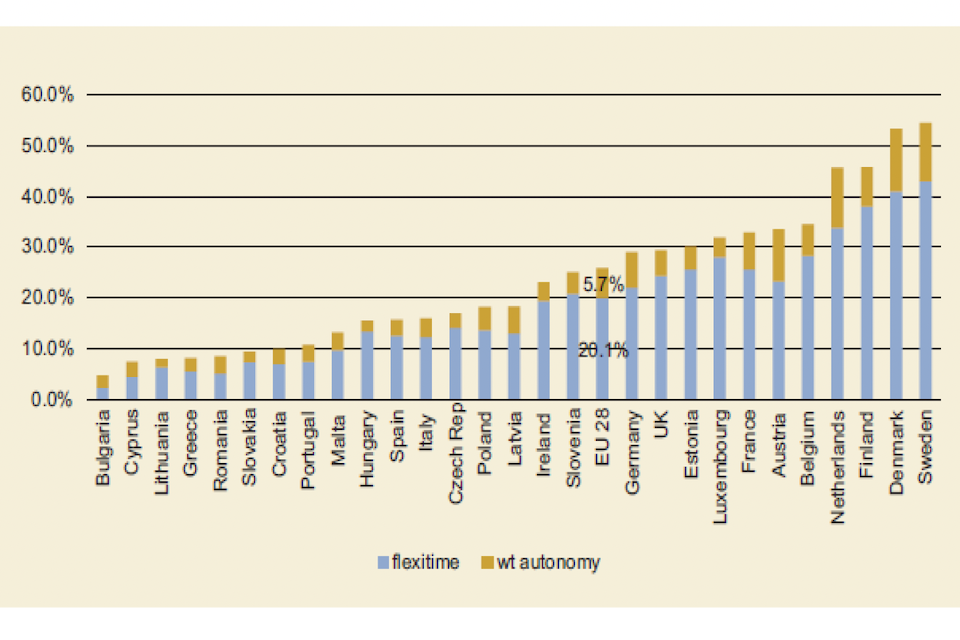

All employees with 26 weeks’ continuous service with their employer have the right to request Flexible Working; however, there is a disparity in how that is adopted in practice. In 2015, approximately a quarter of workers had access to flexitime – the ability to control their schedules - while just under 10% had complete autonomy over their working hours and schedules, slightly above the EU average, but well behind Sweden and Denmark, as shown in figure 9 (Chung, 2017).

Figure 9: The proportion of workers across 28 European countries with access to flexible schedules in 2015

Source: (Chung, 2017)

Flexible working may be less available to lower-skilled workers:

There is some evidence from Europe-wide data to suggest that flexible working is predominantly available to high-skilled workers. Managers, professionals and those in supervisory roles are more likely to have access to flexible schedules, with parental status making very little difference (Chung, 2017). This is supported by data from the Skills and Employment Survey Series, which finds that lower-level workers are the group with the least autonomy over the start and finish times of their work (Warren and Lyonette, 2018).

These quantitative findings are complemented by data we located from qualitative studies. Charlesworth and others’ (2015) study of social care workers found a lack of flexibility around 12-hour shift patterns, while a retail store manager (Smith and Elliott, 2012) observed that flexible working and job share policies were available to the human resources staff within their organisation but not to them. In general, most low-paid women work in small and medium sized enterprises where there are fewer formal family friendly policies and flexibility, where available, is on an informal basis (Backett-Milburn and others, 2008) However, there was also evidence of flexibility being less available at senior levels, something that went hand in hand with long-hours organisational cultures (Broadbridge, 2007; Vinnicombe and others, 2010).

Access to flexible working is often more available in policy than in practice

The literature points to a well-documented implementation gap, with organisations ostensibly committed to flexible working but not providing it in practice (Budjanovcanin, 2018). One key element of this is the gatekeeping of access by managers, with successful policy use highly dependent on their discretion (Callan, 2007; Backett-Milburn and others, 2008; Atkinson, 2011; Budjanovcanin, 2018; Michielsens and others, 2014). A recent study found that, while half of employers in the private sector had written policies on flexible working, 74% of those did not have any written procedure to help managers deal with the request, indicating that most requests are being dealt with on a case by case basis, leaving room for a large amount of managerial discretion (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2014).

Managers, in turn, felt constrained by policies that, if fully implemented, they feared would hinder their ability to meet targets (Callan, 2007; Michielsens and others, 2014), indicating the importance of top down support from senior management, as well as line managers, if flexible working policies are to be successfully implemented.

While some requests for flexible working are successful, a weakness of the current law cited in the located studies is that the success of requests depends on the employee’s bargaining position, meaning that flexible working is not available to less ‘valuable’ employees (Atkinson, 2016).

3.4.3 Employees making use of alternative ways of working are marginalized

We found evidence in the studies we located of the marginalisation of part-time and flexible workers – a phenomenon produced by a mismatch between these ways of working and organisational cultures which equate commitment with the ability to work long hours; and which assume that those who make use of these schemes do not want to develop their careers.

The traditional full-time career path is seen as the norm

In many workplaces, career paths and, by extension, access to senior grades are constructed with full-time workers as the norm, automatically excluding part-time workers (Tomlinson, 2007). One consequence of this is that part-time workers have difficulty in accessing training opportunities, something that is particularly important for women in occupations such as the medical profession, with strict career paths dependent on completion of certain training (Miller and Clark, 2008).

Part-time and flexible workers seen as difficult and time-consuming to manage

A second consequence is that part-time and flexible workers are seen as difficult and time- consuming to manage, making decision makers reluctant to recruit for, or grant request for part- time hours (Conley and Jenkins, 2011). Since, as is discussed further in Section 3.4.6, the negotiation of part-time work often leads to reduced hours without a consequent reduction in work-load, part-time working can lead to resentment among co-workers who may feel they have to pick up the slack (Teasdale, 2013; Jefferson and others, 2015). Analysis of national data found that, in 2011, more than a third of workers believe that working flexibly creates more work for others, with men almost twice as likely to believe this than women (Chung, 2017).

Alternative working is seen as signalling a lack of commitment

Part-time and flexible working conflict with organisational cultures that demand long hours as evidence of commitment (Corby and Stanworth, 2009) or that understand professionalism as ‘patients first, family second’ (Munro and others, 2015; Ozbilgin and others, 2011). For this reason, flexible and part-time ways of working can be associated with a lack of commitment, professionalism, or seriousness about one’s career (Callan, 2007; Kornberger and others, 2010; Tomlinson and Durbin, 2010a; Ozbilgin and others, 2011; Tomlinson and others, 2013; Munro and others, 2015; Gascoigne and Kelliher, 2018), something which has serious consequences for future progression.

3.4.3 Part-time working has a detrimental effect on career progression

As demonstrated in Section 2.1.3, there is clear evidence that part-time work shuts down wage progression, offering extremely poor return on experience, and restricted possibilities for promotion (Connolly and Gregory, 2008; Dex and Bukodi, 2012; Costa Dias and others, 2018; Warren and Lyonette, 2018). Analysing data from the BHPS and Understanding Society (Costa Dias and others, 2018) show that the effect of part-time experience on women’s wage progression is negligible. This effect is particularly large for more highly educated women, who would otherwise have seen the most progression had they continued in full-time work.

Using national data, Warren and Lyonette (2018) find that, despite increases of part-timers in senior level jobs, there is a part-time penalty in perceived possibilities for promotion. In 2012, almost a quarter of part-timers reported no chance of promotion (as against 17% of full-time workers). While lower part-time workers were the group most likely to have no chance of promotion at all, the part-time/ full-time promotion chances gap was widest among higher-level workers. This suggests that even if there are increasing levels of ‘retention’ of part-time workers in highly skilled jobs – valued employees who previously worked full-time before managing to negotiate a reduction in hours - their opportunities for further progression are severely constrained.