Understanding and using smart technical assistance, April 2025

Published 12 May 2025

Alan Whaites, FCDO, Centre of Expertise, Democratic Governance.[footnote 1] April 2025

International co-operation can often include the provision of technical assistance (TA) by a development partner. In some instances TA is intended to supplement local capacity (eg in small state systems), or to fill short-term needs in already high performing organisations. Elsewhere the aim is to support partners to grow their own capacity.[footnote 2] This capacity building role is seen across areas such as service delivery, climate adaption or the promotion of economic growth. This note focuses on the use of technical assistance in its capacity building role, it discusses changes in thinking on TA and sets out how to:

- use diagnostic tools to build shared ownership with counterparts and to improve the design of technical assistance

- adopt 4 principles for ‘smart’ technical assistance that guide technical advisers towards capacity building approaches

- combine technical assistance with additional forms of support, including peer to peer, triangular co-operation and using results-based tools

Moving away from traditional technical assistance

Technical assistance (TA) is a shorthand term for provision of additional skilled human resources to a partner,[footnote 3] this can take many forms such as embedded local or international staff. Other versions include visits from advisers who provide training or short bursts of support.

The genesis of TA owed much to ‘modernisation’ ideas, these assumed that the constraints to development were resource ‘gaps’, such as lack of equipment, or lack of skills and competencies among a partner organisation’s staff. It was believed that filling these gaps would bring partner systems closer to those of donor countries. Implicit was a belief that capacity could be built through a demonstration effect, showing how things ‘should’ be done. The model often included a one-to-one counterpart: once the TA had left then her/his skills would remain through a designated person and the gap would be closed.

Critiques of these TA models have existed for decades.[footnote 4] One concern is sustainability. TA frequently supplement (simply act as additional staff) or even displace local capacity by doing tasks for counterparts. For example, an externally provided economist might draft the new investment strategy, rather than enable others to do so, this can lead to dependence on external skills. Critics argue that TA are disincentivised from transferring skills because this would remove the need for their own roles.[footnote 5] They point to a significant TA ‘industry’ with a need to sustain work and often framed around conventional models of aid.[footnote 6]

A further critique emerged as ‘modernisation’ ideas declined. Questions arose as to whether transferring ‘skills and competencies’ is sufficient. Organisations face challenges in many dimensions: leadership, planning, accountability, performance culture, behaviours,[footnote 7] poor systems, vision etc. Merely working with one member of staff, or a small group, could not address these wider problems. This critique highlighted capability blockages such as ‘collective action problems’ where champions of reform struggle to gain traction internally. A technocrat in the Ministry of Finance might know the tax reforms that are needed, and TA might help them to set this out, but ultimately powerful blockers elsewhere can stifle change.

A further problem was reliance on perceptions or simple outputs to monitor progress (eg was a training session ‘valued’, or a new strategy written). None of these necessarily speak to change in the level of capacity within the organisation, (eg the skills of staff may not have been baselined and retested). These efforts might face challenges given the desire of counterparts to keep TA (if dependency has arisen), leading to optimistic assertions of the benefits.

Why diagnostics have changed thinking on technical assistance

Requirements for TA are often identified through requests from counterparts, sometimes driven by frustrated reformers who simply want staff they believe can ‘deliver’. However, this ‘demand’ driven nature of TA can, on occasion, also open the door for agreement to undertake some form of functional or institutional analysis,[footnote 8] which requires partner buy-in and ownership. Ideally such analysis would be ongoing (undertaken regularly) to help inform changes in support.

‘Functional’ analysis originally derived from ‘time and motion’ studies which evaluated whether processes were being undertaken efficiently. Gradually lessons from ‘organisational development’ theory were adopted, assessing whether the ‘form’ of organisations matched their ‘functions’. Some methodologies have increasingly looked at leadership and behaviours, the FCDO guidance [footnote 9] ensures that a review captures both the formal structures and systems of a partner, and also the underlying factors, norms and behaviours that can shape operations.

Diagnostic tools use a range of techniques such as ‘process mapping’ to identify how work is done, and where major blockages or problems occur. They dig into the reality of an organisation’s operation and assess the quality of its outputs so that changes can be monitored. They consider the views of those involved – at all levels.[footnote 10] A diagnostic not only looks at whether a partner has produced a plan to increase girls’ education, but how it was produced, whether it is evidenced, feasible, costed, communicated, prioritised and championed (and identifies the reasons behind the level of quality achieved). As a result, a diagnostic will challenge the assumptions of development partners. It reveals the deeper story beneath what is observable in regular discussions and programme meetings, or from wider received wisdom.

Robust and ongoing diagnostics change the TA dynamic in 3 ways:

First, they help to ensure a shared understanding of problems and challenges between the counterpart organisation and the development partner. A politically informed diagnostic will also help to unpack the context issues faced by the organisation.

Second, if organisational culture or processes are a problem then dialogue can take place with counterparts to agree that TA will also address those issues, this is called Smart TA,[footnote 11] or a process of reform can be agreed for which the offer of TA is an incentive.

Third, it provides baselines that rely less on subjective perceptions, for example repeating a process mapping exercise can identify whether blockages have reduced (either in terms of formal requirements or delays due to organisational culture). Assessments of the quality of outputs also facilitate re-evaluations over time. This ongoing approach to analysis facilitates more adaptive and iterative approaches to support.

So, what is smart technical assistance?

Smart TA responds to a shared vision between the supporting and counterpart organisations. It builds on approaches developed by providers such as the UK’s NSGI and can only operate as part of a collaborative partnership.

It follows 4 basic principles:

1. Rooted in diagnostics

Smart TA is usually only feasible following some form of institutional analysis, this builds ownership and identifies underlying organisational challenges. It is made clear to a smart TA adviser that the monitoring and evaluation of their work will depend on tracking real change, made possible through the diagnostic. This doesn’t preclude useful TA work being done without diagnostics, but fully Smart TA would be difficult to achieve.

2. An organisational view

Wider change is prioritised beyond one-to-one relationships. Smart TA carries responsibilities linked to issues of organisational culture, values, behaviour, or the prevalent processes of a partner. A typical deliverable will be the improvement of a process or a system. Smart TA is therefore more likely to ‘counterpart’ a team (or indeed a system) in a partner agency, not just one individual. This will include building trust to offer difficult advice and valuing both partner feedback and also the insights from effective monitoring.

3. Constructively political

Organisational politics are never used to foster dependency, instead Smart TA thinks and works politically to help broker agreements and build consensus. Their approach adapts to changing conditions and maintains a focus on improved processes, behaviours and greater capacity. This usually means working in a ‘team’ dynamic with other TA. It will include influencing colleagues and their behaviour (for example promoting collaborative working). This will also involve solving any communication issues, both internally and with development partners.

4. Success, not failure, is rewarded

Smart TA knows that dependency, or a failure to enable reform, are not routes to further contracts to fill ‘gaps’. As a result, Smart TA can’t just write a better girls’ education strategy, in order to succeed the partner’s capacity to do this must change. Supporting this increased capacity will testify to the impact of Smart TA and the value of their work (it will also make the resulting strategy both more realistically achievable, and more owned by the institution itself).

Smarter technical assistance as strategic action on agriculture

In an African context an implementer used Smarter TA not only to build skills and address systems issues, but also to take a big picture view of support to reform. Their willingness to think about reform as a process of change, not just outputs, and to be constructively political were key. When working on reform of agriculture subsidies they:

- identified information asymmetries with the government and international community and solved them where it was to the advantage of reform

- choreographed donor diplomacy at key moments, advising on who to speak to, when, and with what messages

- identified the need for specialist skills, such as a media agency that would support further reform

- built coalitions and networks to maintain a constituency for reform across a wide range of stakeholders, this encouraged others to shift the balance of power around an issue

The process of achieving Smart TA will often be non-linear and involve multiple approaches. Some TA will evolve into Smart TA on their own initiative, or partners will request traditional TA and development partners will use this to gradually build a smarter approach. TA might also be included as one element of a wider ‘systems reform’ initiative that can allow ‘smart’ elements to be promoted through other instruments, such as financial aid.

As a result, the way that ‘smart’ approaches work within a wider dynamic is key. For example, as one expert points out [footnote 12]:

There is a need to keep in mind the balance required for investing in ‘system capacity’ (functionality, performance, accessibility, and reliability) and ‘people capacity’ (skills, competencies, and confidence). The two go hand in hand, for example the potential of e-governance can only be realised if we support people to deliver it.

For this to be effective development partners also need to address their own traditional challenges such as weak organisational memory, uneven management of TA providers or being driven by simple output-based results. Development partners will need to see TA in more flexible and adaptive ways, recognising that moving it along the spectrum of approaches towards ‘Smart TA’ will rely on a strong partnership with the counterpart, and potentially a patient approach.

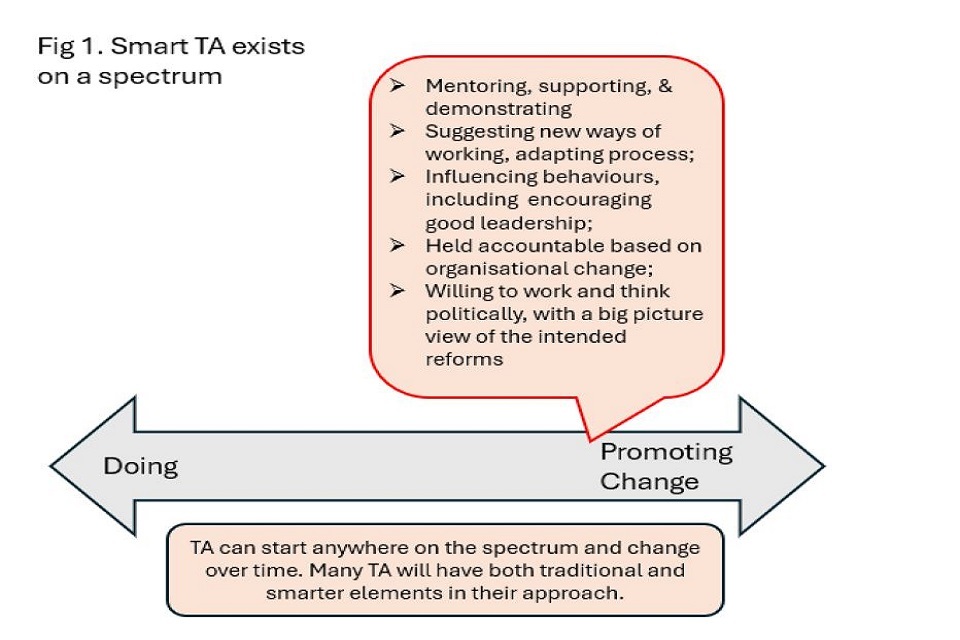

Figure 1: Smart technical assistance exists on a spectrum

Adding to technical assistance

TA is a default modality partly because it is frequently requested by counterparts, however there are complementary options to consider. One of these is the use of peer to peer techniques (P2P – aka practitioner to practitioner). Some development partners have promoted peer to peer, for example the UK has linked counterparts to UK institutions to offer mentoring and experience. South to south or triangular co-operation is also an important option, experience from within a region may be particularly apt for the counterpart body. Regional bodies may also help to facilitate P2P.[footnote 13]

A further option is to focus on incentive-based programmes for existing staff, this can include competitive entry training schemes with incentives such as overseas travel. These programmes are not easy to design and deliver, there are pitfalls particularly if staffing is based on patronage, and promotion based on tenure. Also difficult to do, but potentially beneficial, are support to local training academies and curricula (including online courses). Results based techniques can additionally increase the attention leaders give to capacity building. Local government initiatives pioneered by UNCDF varied organisational budgets based on performance, this focused attention on achieving key metrics, including issues of process and behaviours.

Conclusion

Getting more capacity building value from TA depends on understanding the challenges faced by the counterpart organisation, and this is best done through diagnostics. However, good diagnostics can only go so far, the resulting TA must be qualified and must understand their role in relation to systems and organisational culture.

Throughout the process communication with counterparts is key. Counterparts will be the first to understand problems with TA and may have early insights into issues with individual advisers. Smart TA approaches enable donors to support partners with adaptive programming, using techniques such as ‘Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA)’, or ‘Issues-based Approaches (IBA)’. These are easier if an effective and collaborative diagnostic process is undertaken, and are more likely to deliver change if any resulting TA operates on a non-traditional basis.

-

This document is intended for use as a technical guide, any views expressed are those of the author and do not represent FCDO or UK Government policy. Special thanks to Graham Teskey and Sam Waldock for their inputs, and to Bianca Jinga, Tia Raappana, Matt Carter, Egbert Pos, Richard Butterworth and Verena Fritz for advice/comments on this note. ↩

-

For an explanation of ‘capacity’ vs ‘capability’ see the FCDO guide to institutional analysis. ↩

-

For the formal OECD definition see: Technical Co-operation ↩

-

For example, see: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/315011468173399144/pdf/SWP586000Manag0e0lessons0of0success.pdf (PDF, 7 MB) ↩

-

Studies of TA often implicitly focus on traditional models, see: K4D (PDF, 428 KB), however a comprehensive review of approaches, including some proposals for reforming TA can be found here (PDF, 1.2 MB). ↩

-

Equally, a focus on individuals can mean that newly trained staff leave for higher paid jobs elsewhere. ↩

-

Several models for understanding organisational behaviour exist, a popular one is COM-B, https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/organizational-behavior/the-com-b-model-for-behavior-change ↩

-

Functional, organisation and institutional analysis are the study of organisations and how they operate, several methodologies exist and some are summarised in the FCDO guide, this form of analysis is distinct from other tools such as ‘PEA’ which can be useful to understand related issues, such as the authorising environment. ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/understanding-institutional-analysis ↩

-

For useful insights on this see: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/981311547566282423/pdf/133754-WP-World-Bank-Moving-Further-On-Civil-Service-Reforms.pdf (PDF, 9.5 MB) ↩

-

These approaches fit well with models of institutional support adopting techniques such as ‘Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation – PDIA’. Andrews, M., Pritchett, L. and Woolcock, M. (2012) Escaping Capability Traps through Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA), Centre for Global Development, Working Paper 299. ↩

-

Graham Teskey, peer review of this note. ↩

-

For a discussion of these issues see: https://issuu.com/undppublicserv/docs/eip-nsgi ↩