The Future Cohort Study: understanding Universal Credit’s future in-work claimant group

Published 1 July 2021

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit The Open Government Licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

This document/publication is also available on our website at Research at DWP.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published July 2021.

ISBN 978-1-78659-341-2

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) or any other government department.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the people who gave their time to participate in this research. We would also like to thank Amanda Langdon, Tanya Saunders, Peter Harrison-Evans and Kate Warner at DWP for their valuable input throughout this research programme.

The Authors

This report was authored by researchers at the Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute:

Trinh Tu, Head of Employment, Welfare and Skills, Ipsos MORI

Joanna Crossfield, Research Director, Ipsos MORI

Yasmin White, Research Manager, Ipsos MORI

Jamie Douglas, Graduate Research Executive, Ipsos MORI

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Future Cohort | Current tax credit and Housing Benefit claimants who, based on their current individual and household income, would fall into the ‘Light Touch’ group in Universal Credit (UC) if moved across to UC today. |

| In-work progression | This refers to increasing hours, increasing pay, or gaining new skills/qualifications, or a combination of these, in a current or new job. |

| ‘Light Touch’ group | Group made up of claimants who are in work but on low pay – likely to be working part-time, at or near the National Minimum Wage or National Living Wage. |

| Pull factor | Something which allows, encourages or facilitates progression in work. |

| Push factor | Something which prevents, discourages or impedes progression in work. |

| Work Coaches | Front line Department for Work and Pensions staff based in Jobcentres. Their main role is to support benefit participants into work by challenging, motivating, providing personalised advice and using knowledge of local labour markets. |

List of Abbreviations

AET: Administrative Earnings Threshold

CATI: Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing

CET: Conditionality Earnings Threshold

CTC: Child Tax Credit

DWP: Department for Work and Pensions

ESA: Employment and Support Allowance

ESOL: English as a Second Language

HB: Housing Benefit

JCP: Jobcentre Plus

JSA: Jobseeker’s Allowance

RCT: Randomised Controlled Trial

UC: Universal Credit

WTC: Working Tax Credit

Executive Summary

This report presents findings from quantitative and qualitative research undertaken on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) into the composition and characteristics of the “future cohort”. These are the current tax credit and Housing Benefit claimants who, based on their individual and household income, would fall into the ‘Light Touch’ group in Universal Credit (UC) if moved across to UC today. The ‘Light Touch’ group is made up of claimants who are in work but on low pay – likely to be working part-time, at or near the National Minimum Wage or National Living Wage.

The purpose of this study was to anticipate the likely composition of the ‘Light Touch’ group once the migration of tax credit and Housing Benefit claimants to UC is complete, thereby informing the development of DWP’s services to support these claimants to progress in work. The report explores claimants’ household and employment circumstances, their attitudes towards work and progression, including perceived barriers and enablers, and their needs and preferences around different types of support.

Research design

This research comprised a quantitative telephone survey conducted between April and September 2019 with 3,114 in-work claimants[footnote 1] who were in receipt of Working Tax Credits, Child Tax Credits and/or Housing Benefit. The survey was followed by 60 qualitative depth interviews with individuals (including some paired interviews with both the claimant and their partner) and 11 focus groups.

The quantitative data was used to conduct a segmentation analysis – a statistical technique to group respondents who are similar to one another into discrete segments. This will support DWP to develop tailored services to effectively meet the needs of different groups.

A summary of the findings from the quantitative and qualitative strands of research is presented below.

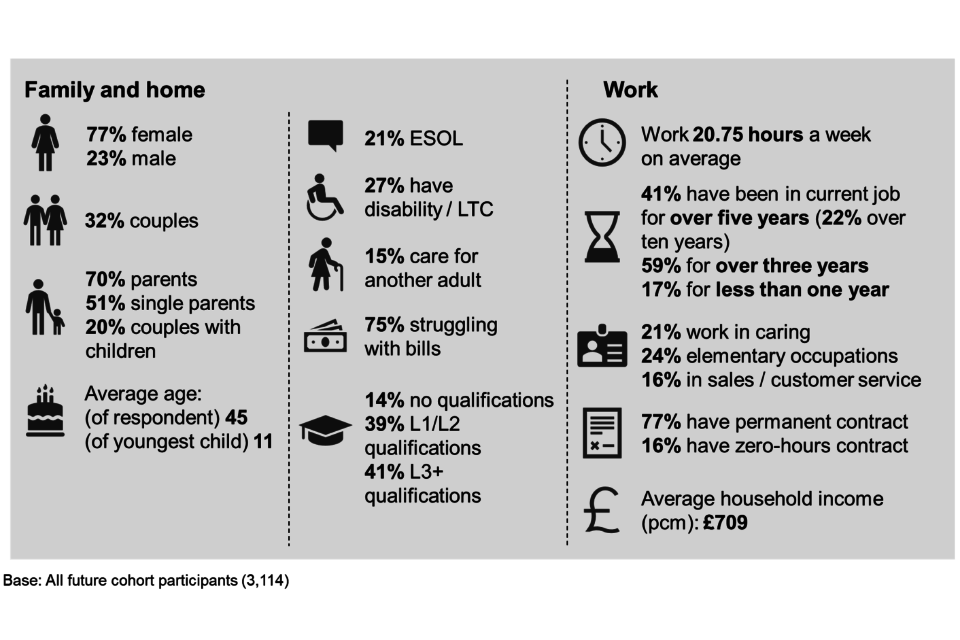

Composition and characteristics of the future cohort

The future cohort is made up largely of women (77%) and parents (70%). Single parents are the largest group (51%), followed by couples with children (20%). Singles or couples without children make up 30% of the future cohort. The average age of individuals in the future cohort is those aged 45. The average age of singles or couples without children is slightly older at 47.5.

Among half of parents (50%), their youngest child is aged between 3 and 11 and for a quarter (23%) their youngest child is at or approaching secondary education. The average age of the youngest child is 11. Lone parents are more likely than couples to have children already in secondary education, with an average age of 12 and 10 respectively, for the youngest child. Where the respondent lives with a partner, 58% of partners are not in work. This type of household is more common among older respondents, aged 45 and over (65% of partners are not in work), and couples without any dependent children (70%).

A quarter (27%) of the future cohort say they are limited in their day-to-day activities because of a health condition or disability. Health conditions or disabilities are more common among men than women (36% compared with 24%), and older claimants (20% of under-35s rising to 40% of those aged over 60).

One fifth (18%) are from an ethnic minority and a similar proportion (21%) have English as a second language. The majority of respondents who have English as a second language classify themselves as from an ethnic minority (59%).

Overall key characteristics of the future cohort

" "

Work, income and skills

Many of the future cohort are in stable employment: 4 in 10 (41%) have been in their current job for over 5 years, and a similar proportion (42%) have been in their role for between one and 5 years. Respondents with no qualifications are more likely to have been in the same job for more than 5 years (48%). Three-quarters of future cohort respondents (77%) have a permanent contract compared to 16% on a zero-hours contract and 4% on a temporary/fixed term or seasonal contract.

Respondents work an average of 21 hours per week. Lone parents work slightly more hours than parents in couples on average: 21 hours compared with 20 hours. Average household earned income is £709 per month. A quarter (26%) have monthly earnings of less than £500 and 16% more than £1,000. Average earnings are highest among couples with children (£888), then couples without children (£696), then lone parents (£685) and lowest among lone adults without children (£586).

Among couples with children, there is a positive relationship between average household earnings and age of the youngest child: £796 where youngest child is aged 16 and over; £790 where youngest child is aged 12-15 and £700 where the youngest child is aged between 4 and 11.

Three-quarters (75%) of the future cohort report at least some difficulty with keeping up with their bills and other financial commitments. Parents are more likely to report financial difficulties than single adults (77% compared with 71%).

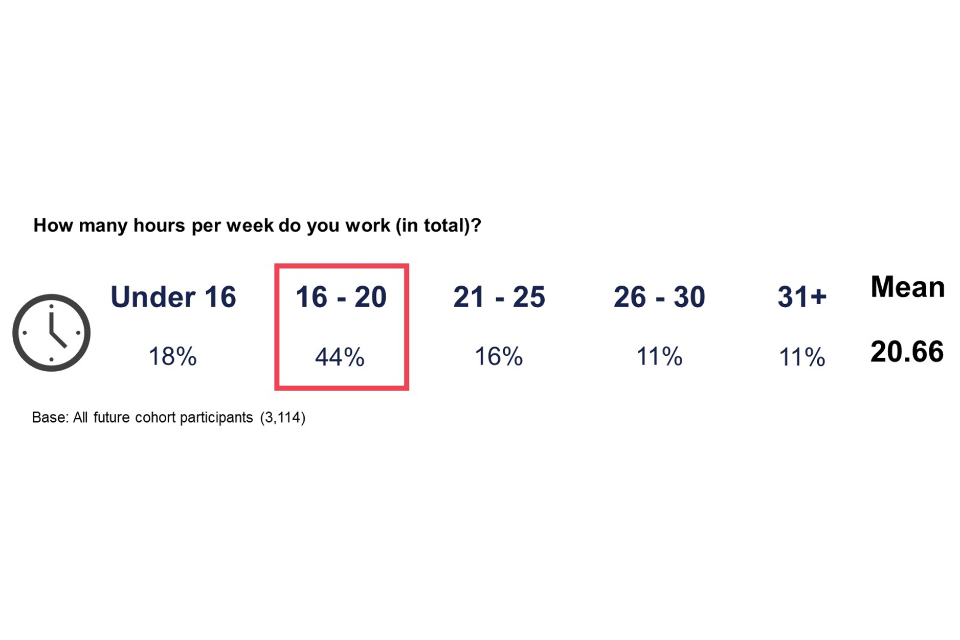

Finally, there is a wide variation in the qualification levels held by the cohort. The most common qualifications are levels 2 and 3 (21% and 25% respectively) but there is also a significant minority (17%) with a degree or above. Conversely, a third only hold a level 1 qualification (18%) or have no formal qualification at all (14%). Respondents with a health condition or disability are most likely to have a degree or higher (39%) but they are also most likely to have no qualifications (25%).

Attitudes towards current role and barriers to progression

The majority of the future cohort are satisfied with the work that they do. Eight in ten (81%) report feeling satisfied with their job overall. Satisfaction is highest with work-life balance (80%) and the number of hours worked (79%). Two-thirds are satisfied with their pay and training opportunities (64% and 66% respectively) and over half (56%) with opportunities for career development.

Reflecting the high overall satisfaction, two-thirds (64%) of respondents strongly agree that their biggest priority is keeping their current job rather than looking to get further at work.

When asked if anything made it difficult to progress in their current job or get a new job, nearly 8 in 10 (81%) of the future cohort reported at least one barrier: 35% mention one barrier to progression, 29% mention 2 barriers, and 17% mention 3 or more barriers. The types of barriers faced by the future cohort are diverse but a common theme among them is the need to balance work with caring responsibilities and health conditions – reflecting the high representation of parents and people with a long-term health condition or disability. These barriers restrict the number of hours that respondents feel they can work and the types of jobs they can consider.

Respondents in the qualitative research, particularly those with children, valued the stability of their current role, and were nervous about making changes (for example, getting a new job) which they felt could upset the balance of work and wider care/family responsibilities.

Motivation, capability and opportunity to progress

To support the design of in-work services a number of the questions in the quantitative survey were structured around the ‘COM-B’ behaviour change model (Michie et al. 2011[footnote 2]). This model identifies 3 fundamental drivers of behaviour (B): capability (C), opportunity (O) and motivation (M).

Considering motivation, the survey found that while the majority of the future cohort are satisfied with their current job, many are also taking steps to explore or pave the way for progression. Around 7 in 10 (72%) report taking at least one action to progress in the past 12 months, most commonly taking a training course (34%) or speaking to their manager about progression opportunities (32%). Lone parents and parents with young children are also more likely than average to have taken steps to progress, while respondents without children were more likely not to have taken any actions (35% compared with 26% of parents).

Motivation to increase pay the next 12 months is strong with 72% saying it is important for them to increase their pay. However, fewer say they want to increase their hours (42%) or get a new job (37%). Furthermore, 3 in 5 (58%) said they would find it difficult to increase their hours if they were offered. The groups more likely to struggle to increase their hours include lone parents, parents with children in primary education, and those with a health condition or disability.

In the qualitative research, parenting and childcare emerged as an important theme which influenced motivation to progress. There were examples of parents being held back from increasing their hours because of a lack of good quality, accessible and/or affordable childcare. However, parents’ considerations went beyond the practical and financial aspects of childcare. In particular, values in relation to parenting were widely discussed. Parents who emphasised the importance of teaching children about work and financial independence reported that this acted to motivate them to progress in work. However, those who felt that spending time with their children was the more important part of their role as a parent were reluctant to increase their hours. This was particularly the case for lone parents and/or those with young children.

In terms of capability, the majority of the future cohort express confidence in their ability to find progression opportunities (74%) and apply for a new job (63%). However, nearly half (47%) feel they first need to improve their skills and qualifications. Those lacking confidence tend to be older (aged 45 or over), without children, with a health condition or disability and without any formal qualification. Participants in the qualitative research cited a lack of up-to-date skills such as IT skills inhibiting their confidence to apply for jobs with progression opportunities. This was more common among older participants and those who had been in the same job for a long period of time.

When asked about opportunities to progress in the local labour market respondents were generally pessimistic. Three in five (61%) agree that the “jobs on offer do not pay enough to make working more hours financially worthwhile”, and more than half (54%) agree that “there just aren’t enough full-time vacancies for everyone at the moment”. Participants in the qualitative research also expressed doubts over the availability of permanent jobs with better pay or hours. There was a general impression that most vacancies were for zero-hours contracts, and a consensus that it was not worthwhile to trade their current stability for potentially more, but variable, hours.

Segmentation

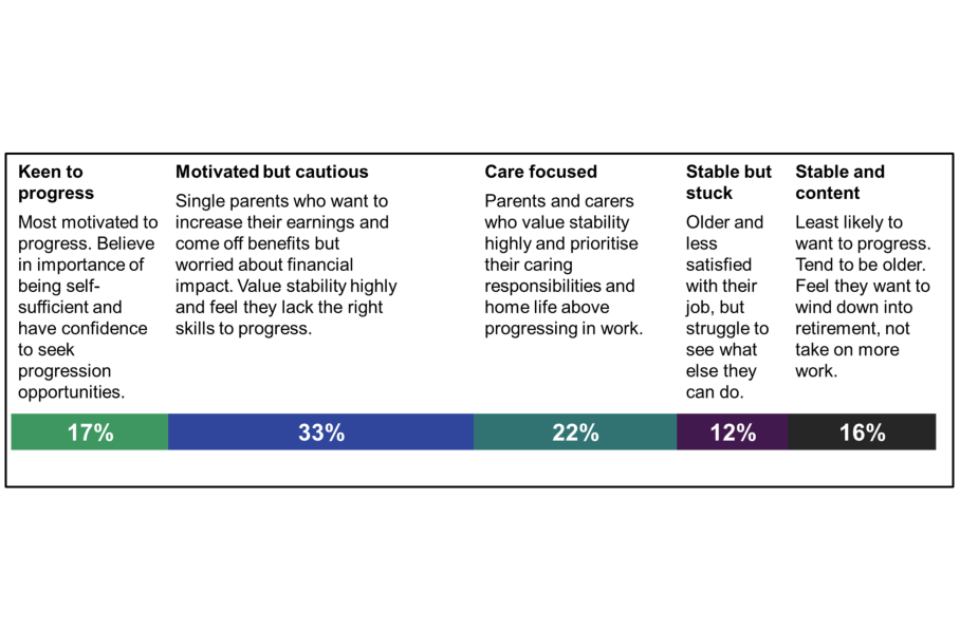

The segmentation analysis produced 5 discrete groups of the future cohort claimants, based on their attitudes and behaviour with respect to in-work progression. The 5 groups and their prevalence are: ‘Keen to progress’ (17%), ‘Motivated but cautious’ (33%), ‘Care focused’ (22%), ‘Stable but stuck’ (12%) and ‘Stable and content’ (16%).

The ‘Keen to progress’ group is the most gender balanced segment (49% are male and 51% female). Unlike the other segments, the majority (68%) live with a partner, either with children (45%) or without children (23%). Compared with other segments, ‘Keen to progress’ respondents have higher qualification levels; almost half (46%) qualified to level 3 or above, however they are also more likely than other segments to be in zero-hours or temporary contracts (28%). Motivation to progress is high in this group; 88% have, for example, taken some action to progress in the past year, and 69% say they want to increase their hours over the next 12 months.

The ‘Motivated but cautious’ group is made up entirely of lone parents and is predominantly female (93%). They are more likely than average to have a child over the age of 16 (33%, compared with 27%). They have a younger age profile (56% are under 45 years old) and are more likely than other segments to say they struggle financially. This group consists of lone parents who want to increase their earnings and come off benefits but are concerned that changes to their work patterns could negatively impact their finances and stability. This group feel they need to develop their skills and qualifications before they are able to progress.

‘Care focused’ claimants are predominantly female (86%), and more than three-quarters have dependent children (54% are lone parents, and 24% live with a partner and children). A quarter (25%) have caring responsibilities for another adult, the highest of any segment. This group work the fewest hours on average (19 hours), and the vast majority say their home life would suffer if they increased their hours (88%). This group value stability, and prioritise their caring responsibilities above progressing in work.

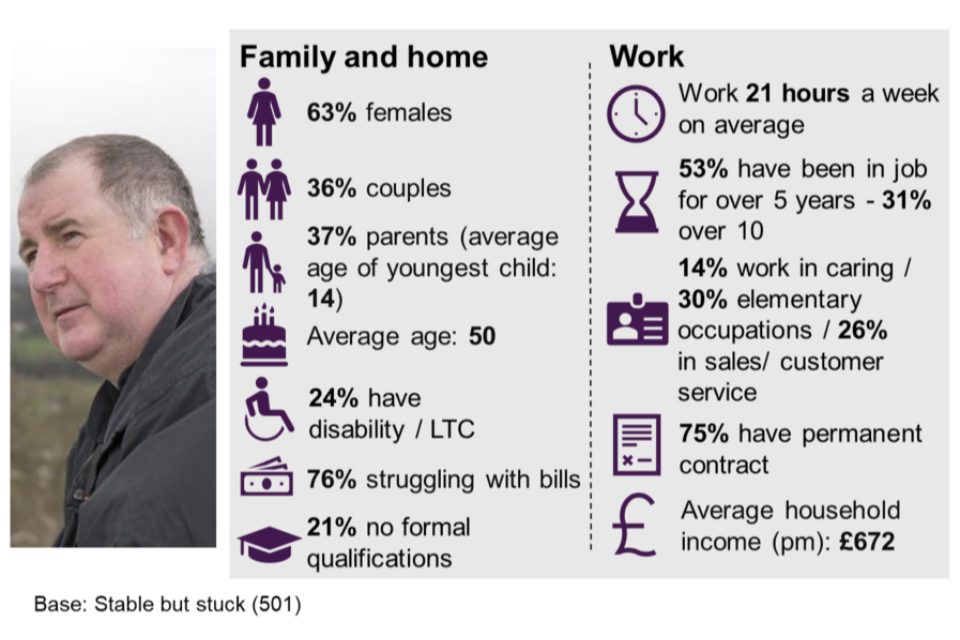

The ‘Stable but stuck’ segment has the second highest proportion of male claimants (37%) and older claimants: 72% are aged 45 or over, including 20% aged over 60. This group have mostly been in their job for more than 5 years (53%). This group are also more likely to have a long-term health condition or disability (40%) and no qualifications (21%), both of which impact on capability to progress. Respondents in this segment tend to be more dissatisfied with their job (17%, compared with the average, 10%) but they often don’t know how, or lack confidence, to progress (38% disagree that they feel confident applying for a new job, compared to the average, 26%).

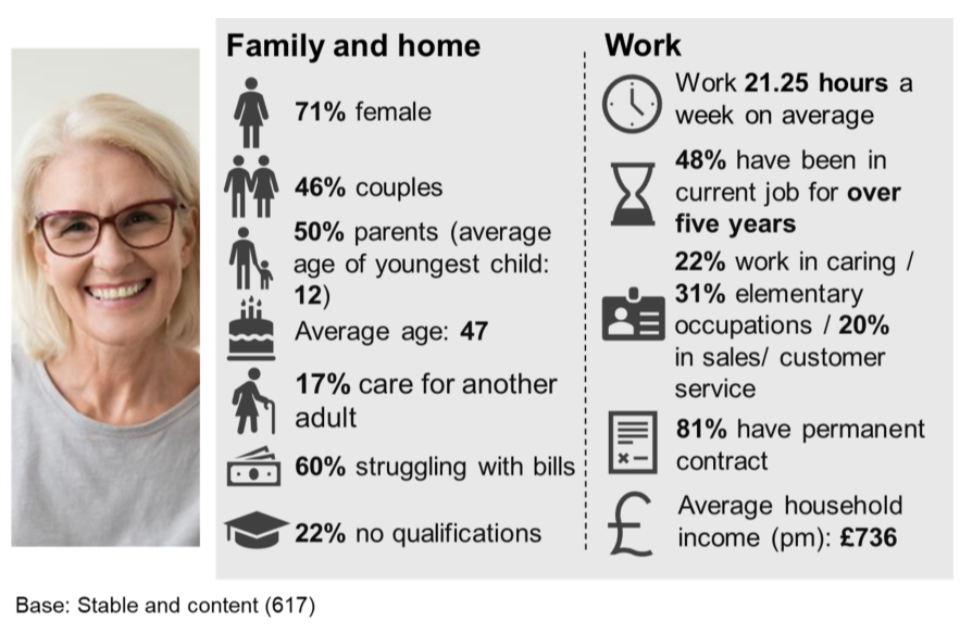

The majority of the ‘Stable and content’ group are female (71%), and they too have an older age profile: 63% are 45 and over. Qualification levels tend to be lower than other segments (22% have no formal qualifications), but they are less likely than other segments to say they struggle financially (60%). ‘Stable and content’ respondents are the most likely to have a permanent contract in their job (81%). This group are the least likely to see progression as important; 78% do not feel it is important for them to increase their hours and almost all (97%) say that they are satisfied with their current job.

Support needs and preferences

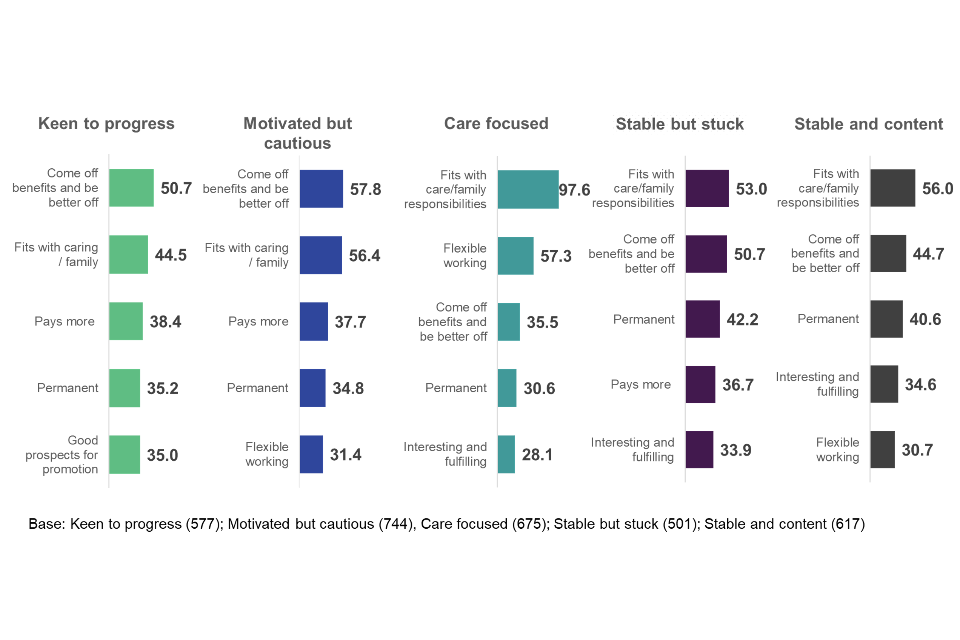

Survey respondents were asked about their preferences surrounding progression, which involved them ranking different features of a job in terms of how much it would encourage them to progress. When considering the relative value of these different job features, respondents across the sample as a whole are most likely to value “a role which fits with my caring or family responsibilities and/or health condition”. However, for the ‘Keen to progress’ and ‘Motivated but cautious’ segments “a role that pays enough for me to come off benefits or tax credits completely and be better-off” is ranked the most highly.

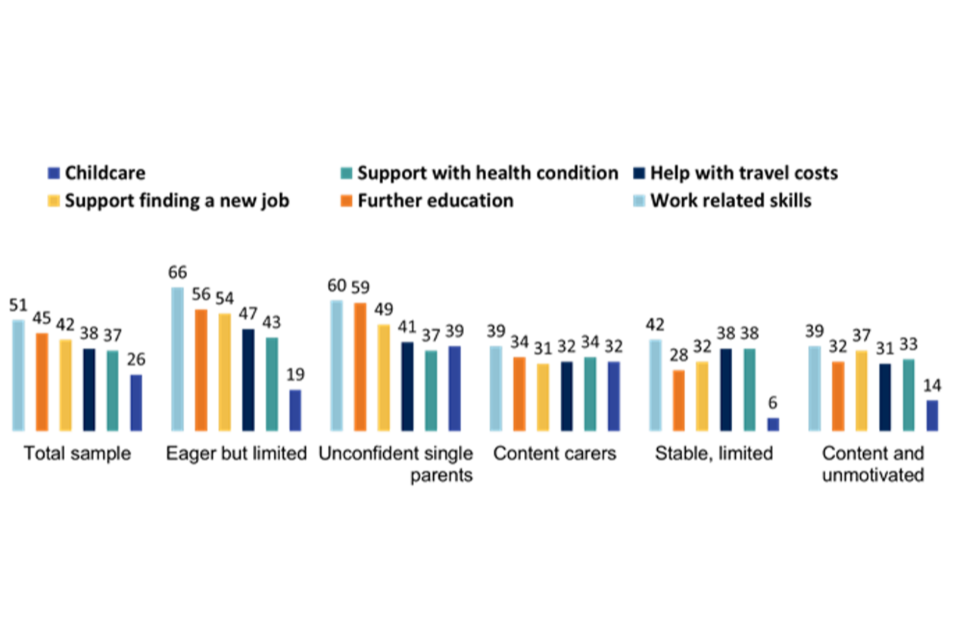

When asked what support they would like to help them progress, respondents identified support and training with work-related skills (51%), support to pursue further or higher education (45%) and support and training on finding or getting a new job (42%). Respondents are most likely to say they would like their employer to support them to progress in work (61%), while fewer respondents wanted support from online sources (40%), friends or family (36%) or Jobcentre Plus (JCP) (34%).

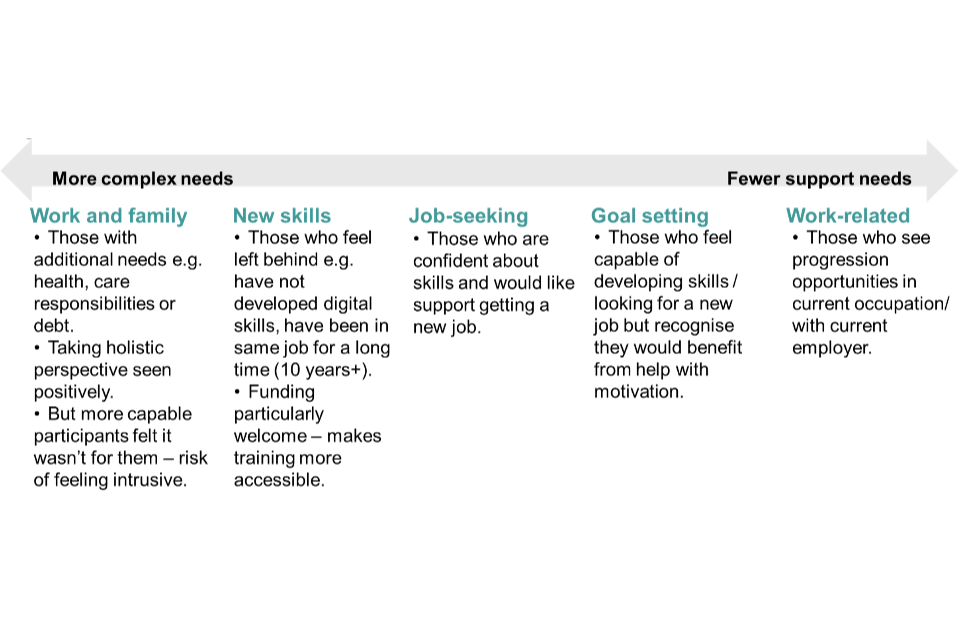

The qualitative research found that the type of intervention which best suited participants depended on their needs, current work status and attitudes towards progression. Participants with more complex needs such as health, debt or family circumstances were most open to holistic support including funding for childcare or debt. Those with lower existing skills felt that JCP was an appropriate provider, but those with higher skills or qualifications were more reluctant to visit a JCP and preferred a private employment agency or accredited training provider. Participants who were happy in their job and could see progression opportunities with their current employer preferred to get training in this way.

How participants wanted support to be provided was related to the content. They felt that online was suitable for factual based content. For support relating to personal experiences or soft skills, participants preferred face-to-face support.

Overall, the future cohort has a diverse range of support needs, and this reflects the high variance in the barriers to progression faced by this group. These findings underscore the need for tailored support which can adapt to varying circumstances and requirements.

1. Background and methodology

1.1. Policy context and existing evidence

Welfare reform is a key government commitment, to make the welfare system fit for the 21st Century: fairer, simpler, providing a transitional support system in times of need, whilst protecting the most vulnerable and being affordable to the taxpayer. The aim is to reduce dependency on the benefits system; increase conditionality and activation policies; make work pay and increase incentives to work. Universal Credit is an essential component, replacing the majority of income-related working age benefits, or “legacy” benefits (Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA), Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), Income Support (IS), Housing Benefit (HB)), and tax credits with a single monthly payment based on real-time information on earnings.

Over the next few years existing legacy benefit and tax credit claimants will be gradually moved over to Universal Credit, with ‘Full Service’ for all claimants established by 2024. DWP currently estimates that out of 7 million households claiming UC, at least 3 million will have someone in paid work.

Of this in work group, just over one million individuals are projected to fall into the ‘Light Touch’ group. ‘Light Touch’ claimants are those who are in work and have individual and household earnings falling between lower and upper earnings thresholds (the Administrative Earnings Threshold (AET) and Conditionality Earnings Threshold (CET) respectively). The level at which these income thresholds are set mean that those in the Light Touch group are generally working part-time and earning close to the National Minimum Wage or National Living Wage. Those earning above the CET fall into the ‘Working Enough’ group.

Increased numbers of in-work claimants represents a significant change to DWP’s customer base and as a result DWP is looking to develop services to support these claimants, with a particular focus on helping them to increase their earnings and progress in their careers. DWP has taken steps to build the evidence base around progression support in UC, through 3 small (‘Proof of Concept’) pilots[footnote 3] running between 2014 and 2016, and a large-scale national Randomised Controlled Trial (In-Work Progression RCT)[footnote 4].

The RCT focused on 30,000 claimants entering the ‘Light Touch’ group between 2015 and 2018, and findings from its evaluation were published in 2018 and 2019. The evaluation found that the RCT produced small, but significant, impacts on earnings for the groups receiving the highest frequency intervention, indicating that active labour market policies can be effective for in-work UC claimants. This added to earlier evidence on progression support from the previous benefit system, such as the Employment Retention and Advancement trial.[footnote 5]

While the RCT provided substantial evaluative evidence on the impact of in-work support on participants, the size, composition and characteristics of the ‘Light Touch’ group are set to change substantially as more people move over to UC. For example, on the RCT many participants had just entered work after a period on JSA, but as the ‘Light Touch’ group grows many more will have been working prior to moving onto UC and in receipt of in-work benefits, particularly Working Tax Credits (WTC) and Child Tax Credits (CTC).

This study aims to bridge the evidence gap between what is already known about current in-work UC claimants, and what has been, until this point, little known about the ultimate composition of the ‘Light Touch’ group. This will support DWP to develop and test more targeted interventions based on the circumstances, needs and preferences of the future ‘Light Touch’ cohort.

To do this the research focuses on exploring the characteristics and circumstances of current tax credit and HB claimants who would fall into the ‘Light Touch’ group if they moved over to UC today (those whose earnings falling between the AET and CET). This group represents the vast majority of claimants who will make up the ‘Light Touch’ cohort once the move to UC is complete. For the rest of this report we will refer to this group of tax credit and HB claimants – the focus of this research – as the future cohort.

1.2. Research objectives

This research aimed to help DWP better understand the current Working Tax Credits, Child Tax Credits and Housing Benefit population who, based on current earnings, will comprise the vast majority of the ‘Light Touch’ claimant group when moved across to UC.

The specific objectives of the research were to:

- understand the likely composition and characteristics of the future cohort

- understand the range of barriers and enablers to progression and the support needs of the future cohort

- assess awareness of, and reaction to, in-work support and understand how this might influence behaviour

- inform the development of effective and targeted interventions to support progression

For the purposes of this study, progression is defined as increasing pay, working hours, or activities such as training which could help respondents progress in work in the future.

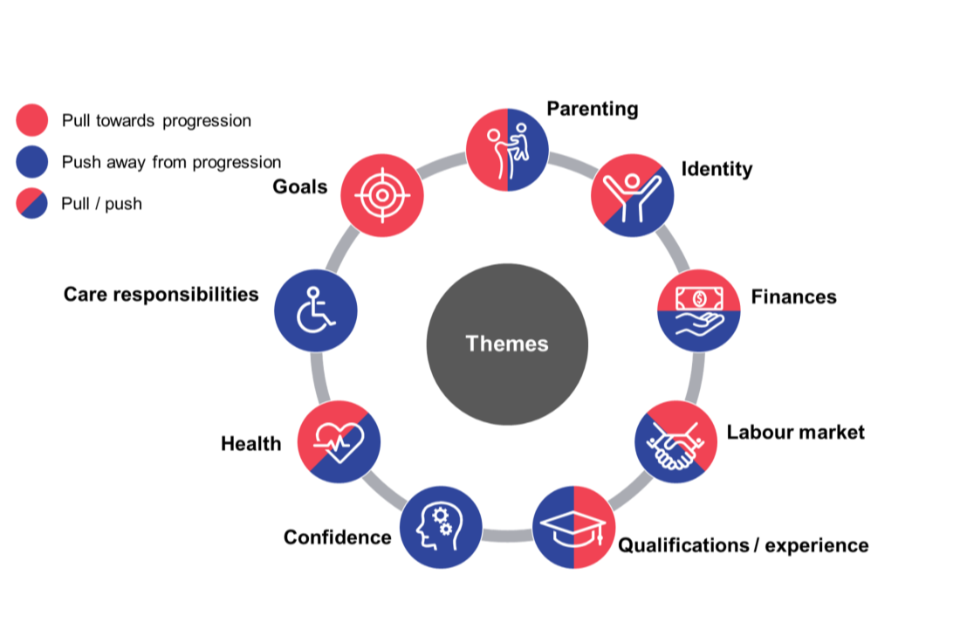

A key output from this research is a segmentation of the future cohort based on their attitudes, behaviours and capabilities to progress in work. To meet this requirement, many of the research questions were structured around the COM-B behaviour change model (Michie et al. 2011[footnote 6]). This model identifies 3 fundamental drivers of behaviour (B): capability (C), opportunity (O) and motivation (M):

- capability: an individuals’ psychological and physical ability to carry out a behaviour or activity, for example, their skills, qualifications and health (this is covered in section 3.1.2)

- opportunity: external factors which make a particular behaviour or activity possible, for example, progression opportunities with their current employer and in the wider labour market (this is covered in section 3.1.3)

- motivation: reflective and automatic thought processes which affect decision making, for example current job satisfaction and future aspirations and goals (this is covered in section 3.1.1)

1.3. Research design

This research comprised 2 strands, summarised below and set out in detail in Appendix A.

1.3.1. Quantitative research

Quantitative research comprised a survey of claimants who were in work and in receipt of one or more of: Housing Benefit, Child Tax Credits or Working Tax Credits and whose earnings were between the AET and CET. Tax credit claimants were selected from Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs’ (HMRC’s) claimant database and Housing Benefit claimants from DWP’s claimant database[footnote 7]. The sample was selected to be representative of DWP’s forecast for the future cohort in December 2023 (in terms of household composition, earnings and benefit type).

Fieldwork began on the 24 April 2019 and ended on the 30 September 2019. Fieldwork was conducted by Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI). The survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Interviews were conducted with 3,114 future cohort respondents.

1.3.2. Qualitative research

Qualitative research comprised depth individual interviews, paired interviews and focus group discussions with a sample of claimants who had taken part in the quantitative survey.

In depth interviews

The main focus of these interviews was to understand claimants’ household and financial circumstances, household attitudes towards progression and their support needs[footnote 8].

Eighty-three people took part in follow-up face-to-face depth interviews lasting one hour each comprising 37 individual depth interviews and 23 paired interviews. Paired interviews were held between the main participants and their partner or another close family member. All lead participants were in work at the time of the interview. Participants were purposively selected from the survey sample to ensure a broad spread of age, gender, ethnicity and educational qualifications as well as diversity of employment history such as length of time in role and contract type. Full details of the quotas achieved are included in Appendix A.

Fieldwork took place in a number of locations across England, Wales and Scotland between the 10 September 2019 and 15 October 2019.

Focus groups

The purpose of the focus groups was to understand claimants’ support needs and their reactions to different support options[footnote 9].

Eleven focus groups were held; 3 in London, 2 in Manchester, 2 in Leeds, 2 in Glasgow and 2 in Birmingham. Each focus group consisted of between 2 and 6 people (39 participants in total). As with the in-depth interviews, participants were screened to ensure they were in work and in receipt of tax credits and/or Housing Benefit. Quotas were also set to ensure a good representation by age and gender (see Appendix A for further details).

Fieldwork took place between the 15 October 2019 and 24 October 2019.

1.3.3. Interpreting the findings in this report

This research presents a snapshot of WTC, CTC and HB claimants, whose income falls between the AET and CET. This cohort would make up the vast majority of the ‘Light Touch’ group if moved over to UC today. However, the authors and DWP acknowledge that this will not be fully representative of future in-work claimants as a whole, as the research sample does not contain claimants who are currently in UC ‘Light Touch’, as well as claimants who are also working but earning above the CET or below the AET.

The survey data were weighted by gender, age and presence of children based on DWP’s forecast for the size and composition of the future cohort group in December 2023. A detailed breakdown of the weighting profile is included in Appendix A.

Only statistically significant findings from the survey have been reported in the commentary (although charts and tables may include non-statistically significant differences)[footnote 10]. All tables and charts report weighted data but include the unweighted base.

The survey results are subject to margins of error, which vary depending on the number of respondents answering each question and pattern of responses. Where figures do not add to 100%, this is due to rounding or because the question allows for more than one response.

Qualitative research is detailed and exploratory. It offers insights into people’s opinions, feelings and behaviours. All participant data presented should be treated as the opinions and views of the individuals interviewed. Quotations and case studies from the qualitative research have been included to provide rich, detailed accounts, as given by participants.

Qualitative research is not intended to provide quantifiable conclusions from a statistically representative sample. Furthermore, owing to the sample size and the purposive nature with which it was drawn, qualitative findings cannot be considered representative of the views of the future cohort population as a whole. Instead, this research was designed to explore the breadth of views and experiences, in order to develop a deeper understanding of attitudes towards progression and support preferences.

2. Composition and characteristics

This chapter covers the characteristics and circumstances of the future cohort to provide context for interpreting the findings in later chapters. It also introduces the segment groups that form part of the analysis. Findings in this chapter are from the quantitative survey only.

Chapter summary

" "

Demographics

- around three-quarters of the future cohort are female (77%)

- the average age is 45

- around a quarter (27%) say that they have a health condition or disability that limits their ability to carry out day to day activities

Household composition

- seven in 10 (70%) have dependent children and half (51%) are lone parent households

- female respondents are more likely to be lone parents (61%, compared with 16% of males)

- where the respondent lives with a partner, 58% of partners are out of work

Employment

- on average, respondents work 21 hours per week, with 15% working less than 16 hours per week and 11% working more than 30 hours per week

- 9% of respondents have more than one job

- whilst most respondents (77%) have a permanent work contract in their sole or main job, suggesting a high level of stability, a fifth are in more precarious work - 16% have a zero-hours contract and 4% have a temporary/fixed term or seasonal contract

- around 4 in 10 (41%) have been in their current job for over 5 years

- the average household earned income is £709 per month. Around 1 in 4 households (26%) earn less than £500 per month, while 16% earn more than £1,000

Education and English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL)

- around half of the future cohort have qualifications equivalent to level 2 or below (53%), whilst 1 in 6 have qualifications equivalent to degree level or above (17%). One in 7 (14%) have no formal qualifications

- one in 5 respondents (21%) say that English is their second language

2.1. Demographics and household composition

Around three-quarters of the future cohort are female (77%) and a quarter (23%) are male. The average age is 45. For female respondents the average age is 44, whilst for male respondents it is 46. Figure 2.1 provides a breakdown by age band.

Figure 2.1: Respondent age

| Age | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Under 35 | 17% |

| 35 to 44 | 30% |

| 45 to 60 | 46% |

| Over 60 | 6% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

Around a quarter of future cohort respondents (27%) say that they have a health condition or disability that substantially limits their ability to carry out normal day to day activities. Of these, 37% consider themselves to be disabled (equivalent to 10% of all respondents). Nearly three-quarters (72%) of those who consider themselves to be disabled receive Personal Independence Payments.

Men are more likely than women to say they have a limiting health condition or disability (36% compared with 24%), and this also increases with age (20% of under-35s rising to 40% of those aged over 60).

Four in 5 future cohort respondents describe themselves as having a white ethnic background (80%), while 18% say they are from an ethnic minority. Details are shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Ethnic background

| Ethnic background | Percentage |

|---|---|

| White | 80% |

| Mixed | 3% |

| Black | 7% |

| Asian | 6% |

| Other | 2% |

| Do not know or refused | 2% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

Around 1 in 5 respondents (21%) say that English is their second language. This applies to 12% of white respondents and 59% of respondents from an ethnic minority. Men are more likely than women to say that English is their second language (31% compared with 18%).

2.1.1. Household composition and caring responsibilities

Around half of the future cohort are lone parents with children aged under 16 (51%). A full breakdown of household composition is provided in Figure 2.3. Overall, 70% of respondents live with dependent children. Six in 10 female respondents are lone parents (61%), compared with only 16% of male respondents.

Figure 2.3: Household composition[footnote 11]

| Household composition | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Single adults with children | 51% |

| Couples with children | 20% |

| Single adults without children | 18% |

| Couples without children | 12% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

Among those with children, 50% have one child, 34% have 2, 12% 3 and 4% have 4 or more. Half have a youngest child below secondary school age. Details on the age of the youngest child are shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: Age of youngest child[footnote 12]

| Age | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 3 to 11 | 50% |

| 12 to 15 | 23% |

| 16 or over | 27% |

Base: All future cohort participants who are living with dependent children (1,594)

Lone parents’ youngest child is on average older than the youngest child of couples with children (12 years old compared with 10 years old).

Among those with children, almost half (45%) look after their children themselves and do not use childcare. A similar proportion (42%) use informal childcare, most commonly family members. Just over a third (36%) use formal childcare[footnote 13], most commonly breakfast or after school clubs/activities (see Figure 2.5). Compared with the average, respondents with children aged 12 to 15 were more likely to not use any form of childcare (70%), whereas those with children aged 3 to 11 were more likely to use informal childcare, such as family members (38%) and breakfast or after-school clubs (32%).

Figure 2.5: Types of childcare

| Types of childcare | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Family member | 33% |

| Breakfast club or after school clubs/activities | 24% |

| Ex-husband/wife/partner | 14% |

| Friend or neighbour | 11% |

| Nursery, playgroup, or pre-school | 9% |

| Holiday club or scheme | 9% |

| Childminder/nanny/au pair in our home or somewhere else | 4% |

| Other | 2% |

| No, cared for by me (or me and my partner) | 45% |

Base: All future cohort participants with younger children aged under 6 (1,594)

30% of the future cohort do not have children. Four in 10 (41%) have a partner and 6 in 10 (59%) are single. This group are older than the future cohort on average and have a mean age of 47.5 compared with 43.3 for those with children.

In total, 15% of the future cohort have caring responsibilities for people other than their children; specifically, 6% care for a parent, 5% for their partner and 5% for other family members. Older respondents are more likely to have caring responsibilities (18% of those aged 45 or over, compared with 12% of those aged under 45). Men and women are equally likely to report caring responsibilities. Couples without children are particularly likely to have caring responsibilities (36%), most commonly for their partner (24%).

2.1.2. Partner’s work status

Where the respondent lives with a partner (32% of cases), 29% of partners are in paid employment and 13% are self-employed. More than half of partners (58%) are not in paid employment (see Figure 2.6).

Three-quarters of partners in work (76%) have a permanent or open-ended job or contract with a fixed or minimum number of hours per week, while 17% are on a zero-hours contract (see Figure 2.13).

Figure 2.6: Partner work status and contract type

Which of the following best describes your partners’ employment status at the moment?

| Partner work status | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Self employed | 13% |

| Working for an employer in paid employment | 29% |

| Not working in paid employment | 58% |

Base: All future cohort participants with a partner (1,035)

Which of the following best describes their contract?

| Contract type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Permanent or open ended contract | 76% |

| Temporary/fixed term contract | 5% |

| Zero hours contract | 17% |

| Other | 3% |

Base: All future cohort participants with a partner in work (383)

Female respondents are more likely than male respondents to have a partner who is working (52% compared with 28%). The partner is also more likely to be in work where the couple have children (49%) than where they have no children (30%). The use of childcare also varies: where the partner is in work, around half (51%) use childcare, particularly informal childcare (38%). However, where the partner is not in work, only 38% use childcare and this is more likely to be formal (30%) than informal (23%).

The partner is less likely to be working among older respondents. 65% of those aged 45 or over have a non-working partner compared with 49% of those under 45. In addition, 7 in 10 (70%) of those who are in a couple without children have a non-working partner. Those with no qualifications (81%) are the most likely to have a non-working partner, compared with 50% of those with level 3 or higher qualifications. Respondents from an ethnic minority (67%) are also more likely to have a non-working partner than white respondents (55%).

2.1.3. Tenure and financial management

Just over a quarter of respondents (28%) own their home (with partial or full ownership) while the majority (69%) rent their home, either from a local authority (25%), private landlord (24%) or Housing Association (18%).

The majority of the future cohort have some difficulty keeping up with their bills and financial commitments (75%). This includes 10% who say they are falling behind with payments, 17% who are keeping up but find it a constant struggle, and 49% who keep up but struggle from time to time. Just under a quarter (23%) say they keep up without difficulty (see Figure 2.7).

Home owners are more likely than renters to say they keep up without difficulty (30% compared with 19%) and are less likely to say they are falling behind with payments (4% compared with 12%).

Figure 2.7: Ability to keep up with bills

| Thinking about the last 2 months, which of the following statements describes best how well you have been keeping up with your bills and commitments? | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Keeping up – no difficulty | 23% |

| Keeping up – struggle from time to time | 49% |

| Keeping up – constant struggle | 17% |

| Falling behind – some bills | 6% |

| Falling behind – many bills | 4% |

| No bills or commitments | 1% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

2.1.4. Internet use

The vast majority of respondents have access to the internet; 4% do not use or have access to the internet at all. Respondents are most likely to connect to the internet through a smartphone (80%), while more than half use a laptop or desktop computer, either at home (54%) or at work (29%). One in 6 (17%) only access the internet through a smartphone (see Figure 2.8), which may have implications for the types of activity they carry out online and the types of support that may be needed.

Older respondents are more likely to have no internet access at all (21% of those aged over 60), while younger respondents are more likely to access the internet only through a smartphone (24% of those aged under 35). Respondents without formal qualifications are particularly likely either to lack internet access at all (15%) or to go online solely through a smartphone (25%).

Figure 2.8: Ways of connecting to the internet

| Which, if any, of the following do you use to connect to the internet | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Smartphone | 80% |

| Laptop/desktop computer at home | 54% |

| Tablet | 35% |

| Laptop/desktop computer at work | 29% |

| Smart TV | 29% |

| Video game console | 19% |

| Do not use or have access to internet | 4% |

| Only smartphone | 17% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

2.2. Work, income and skills

Nine in 10 (90%) have one job and work on average 20.66 hours per week. Hours worked are slightly higher among men (22 per week) than women (20). There are indications of high levels of stability within the future cohort: most have a permanent contract and 4 in 10 have been in their current role for over 5 years. Work history further demonstrates these high levels of stability: a fifth have worked solidly since leaving school and among those who have had time out of the labour market, the most common reasons are maternity or paternity leave or to care for a child. However, there are a substantial minority who are in more insecure or unstable work, a fifth have a zero-hours or fixed term contract. Across all contract types, the future cohort are most likely to be working in low-skilled occupations, which may limit their scope for progression.

2.2.1. Current employment

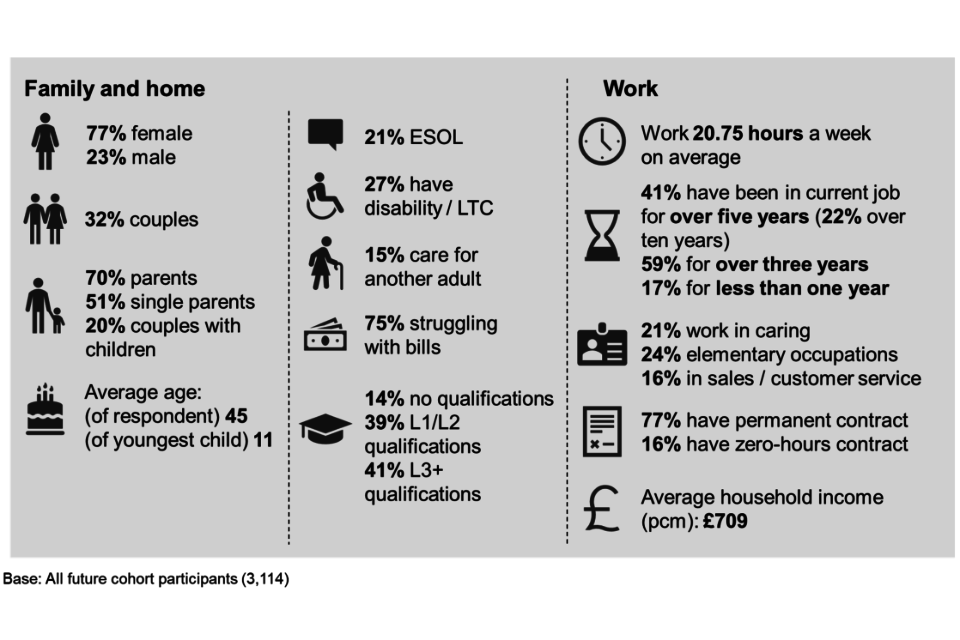

Nine in 10 (91%) of the future cohort have one job and on average, respondents work 21 hours per week in their main or sole job, with 15% working less than 16 hours per week and 44% working between 16 and 20 hours per week. One in nine (11%) work more than 30 hours per week (see Figure 2.9)[footnote 14].

Hours worked in their main job tend to be higher for men than women (22 compared with 20 hours per week on average). Those without children work slightly more hours than those with children (21.2 hours compared with 20.4). Among parents, hours increase with the age of the youngest child (average of 19 hours per week where the youngest child is aged 4 to 11, rising to 22 hours per week where the youngest child is 16 or over). There are no differences in the hours worked by those with a working or non-working partner.

Figure 2.9: Hours worked per week (in main job)

" "

9% of the future cohort have more than one job. Among those with more than one job they work an average of 12 hours per week in their second job. Combining both their main job and other roles, the average number of hours worked per week is 22.

The reasons why respondents have more than one job are: not being able to get enough hours in one job (53%), because jobs do not pay enough to have one job only (29%), needing or wanting the flexibility (27%) and liking the variety (20%). There is no difference in the proportion of men and women who have more than one job, but those aged 45 and over are more likely than under 45s to have more than one job.

Respondents are most likely to work in elementary occupations (27%), in caring, leisure or other service jobs (24%) or in sales or customer service roles (21%). The main industries are health and social work (23%), wholesale and retail trade (19%) and education (16%) (see Figure 2.10). Overall, respondents are mostly in low-skilled work, which may limit their scope for progression in the absence of further skills development. Indeed, the survey data suggests a link between occupation, hours worked and qualifications, with more highly qualified respondents tending to work more hours per week in more skilled occupations.

Figure 2.10: Occupation and Industry

| Occupation | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Elementary | 27% |

| Caring, leisure and other service | 24% |

| Sales and customer service | 21% |

| Adminstrative and secretarial | 10% |

| Skilled trade | 4% |

| Associate professional and technical | 3% |

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 3% |

| Industry | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Health and social work | 23% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 19% |

| Education | 16% |

| Accommodation and food services | 10% |

| Administration and support | 9% |

| Manufacturing | 6% |

| Transportation and storage | 4% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

Most respondents (77%) have a permanent or open-ended job or a contract with a fixed or minimum number of hours per week, indicating that they are in stable employment. However, a substantial minority are in more unstable work. One in six (16%) have a zero-hours contract or a job with no specified minimum number of hours each week, and 4% have a temporary or fixed term or seasonal contract with a specified end date and regular or minimum number of hours (Figure 2.11).

Women are more likely than men to have a permanent contract (79% compared with 69%). Respondents from an ethnic minority (67%) and those who speak English as a second language (69%) are less likely to have a permanent contract.

Four in 10 respondents (41%) have been in their current role for over 5 years and a similar proportion (42%) have been in their job for between one and 5 years. One in 6 (17%) have been in their job for less than a year (Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.11: Contract type and length of time in current job

| Contract type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Permanent contract | 77 |

| Zero hours | 16 |

| Temporary | 4 |

| Length of time | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Less than 6 months | 7 |

| 6 months to one year | 10 |

| 1 to 5 years | 42 |

| Over 5 years | 41 |

Base: All future cohort participants

2.2.2. Income

The average household income from employment earnings is £709 per month. Around 1 in 4 (26%) have a monthly earned income of less than £500 per month, while 16% have a monthly income of more than £1,000. The cumulative distribution of household income is illustrated in Figure 2.12.

Figure 2.12: Household income per month

| Household income per month | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Under £500 | 26% |

| £500 to £749 | 36% |

| £750 to £999 | 23% |

| Over £1,000 | 16% |

Base: All Light Touch participants (3,114)

Where respondents live with a partner who is also in work, the average household earned income is £1,098 per month, higher than where the partner is not in work (£611). Among couples with children, there is a positive relationship between average household earnings and age of the youngest child: £796 where youngest child is aged 16 and over; £790 where youngest child is aged 12 to 15 and £700 where the youngest child is aged 4 to 11. Earned income is higher among those with older children: £796 where youngest child is aged 16+ and £790 where youngest child is aged 12 to 15, compared with £700 where youngest child is aged 4 to 11.

Qualification levels also have an impact on average earned income. Those qualified to level 3 or above have an average earned income of £748 compared with £695 among those qualified to level 2 or below, and £628 for those with no qualifications. Those who have been in their current role for more than 5 years also have a higher than average earned monthly income (£737).

2.2.3. Work history

The majority of the future cohort have spent most of the time since they left full-time education in work. This includes 1 in 5 (20%) who have worked solidly without a break, and a further 59% who have worked solidly with one or two breaks. The remainder have either spent as much time working as not working (14%) or have spent most of the time not working (8%).

The most common reasons for breaks in employment are maternity or paternity leave (39%), while 23% have taken time off to care for a child or someone else, and 16% have taken time off for health reasons.

2.2.4. Education

Just over half (53%) of the future cohort respondents have qualifications equivalent to level 2 or below (53%), including 14% that have no formal qualifications. One in 6 respondents are qualified to degree level or above (17%), as shown in Figure 2.13.

Men are more likely than women to have no qualifications (22% compared with 12%) and older respondents are also much more likely not to have any qualifications (19% of those aged 45 and over compared with 9% of under 45s). Respondents who have English as a second language are more likely to have a degree (24%) than those who have English as their first language (15%). This variation is likely to lead to different expectations and requirements for support and the types of job they may be interested in. Variation in expectations requirements for support is discussed further in the qualitative findings (chapter 3.2.5).

Figure 2.13: Highest qualification level[footnote 15]

" "

Qualification levels are related to current work status. Those with level 3 or higher qualifications work more hours on average per week (21.38) than those with level 2 qualifications or below (20.22). They are also more likely to work in more skilled occupations, such as human health and social work (28%) and education (22%) than those with level 2 and below qualifications who are more likely to work in wholesale and retail (22%) or those with no qualifications who are most likely to work in administrative and support roles (16%).

Respondents who report themselves as having a disability are most likely to have level 3 qualifications or higher (42%), a third (35%) have level 2 qualifications or lower and a quarter (25%) have no qualifications.

2.3. Segmentation

A key objective of the research was to differentiate the future cohort according to their capability, motivation, beliefs about opportunity in the labour market, together with their support preferences in relation to in-work progression[footnote 16]. A segmentation analysis was conducted using a statistical technique known as Latent Class Analysis (see Appendix A). The segmentation identified 5 groups of respondents, each sharing similar attitudes, behaviours and capability with respondents within their segment but being distinctly different to respondents outside their segment.

At this stage, it is important to re-iterate that the segments were modelled to differ on a range of circumstances, attitudes and behaviours. The segments are intended only to show broad characteristics, and as a result no claimant will ever conform perfectly to the segmentation typology, but they will still be closer in their characteristics to one of these groups rather than the others. Fuller technical details of the segmentation approach used can be found in Appendix A including details of the questions used for the analysis.

Figure 2.14 shows the proportions of each segment group, as well as a brief summary.

Figure 2.14: Summary of segment groups

" "

The remainder of this chapter provides a short summary of the characteristics of each segment, before providing a detailed exploration of their demographics, and household and employment arrangements. To compare segment statistics with the future cohort as a whole please refer to the chart the Chapter Summary. Subsequent chapters describe the attitudes, motivations and support needs which define each segment.

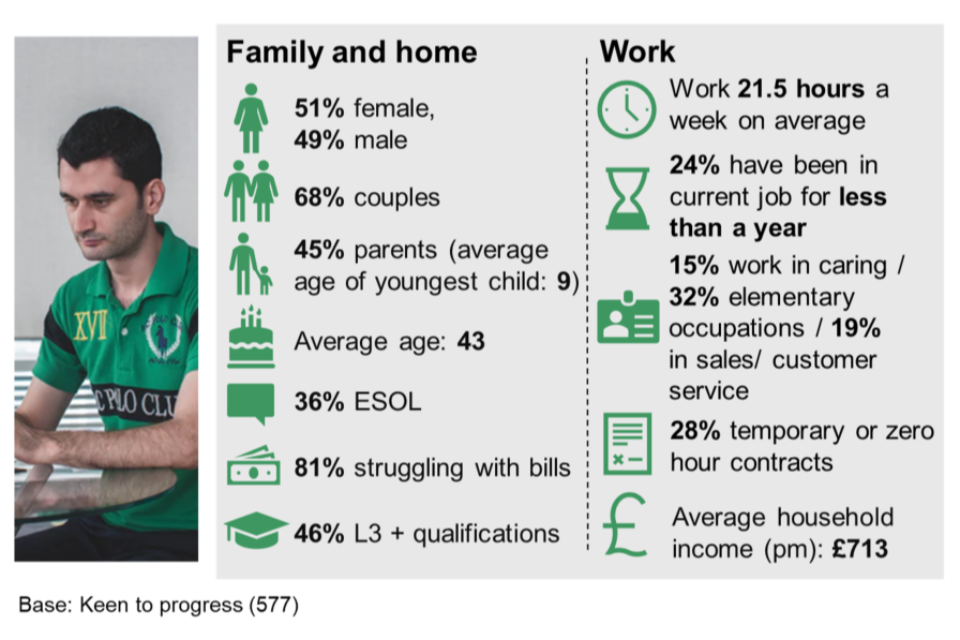

2.3.1. ‘Keen to progress’ segment

The ‘Keen to progress’ segment (Figure 2.15) make up 17% of the total sample of the future cohort. This group demonstrated the highest motivation to progress. They strongly believe in the importance of being self-sufficient and are confident in seeking progression opportunities.

Figure 2.15: ‘Keen to progress’ segment: key characteristics

" "

This is the most gender balanced segment (49% are male and 51% female). Unlike the other segments, the majority (68%) live with a partner, either with children (45%) or without children (23%). The age profile is similar to the total sample of the future cohort.

Compared with other segments, ‘Keen to progress’ respondents have higher qualification levels, with almost half (46%) qualified to level 3 or above. Respondents in this segment are the most likely to speak English as a second language (36%) and to be from an ethnic minority (37%).

Respondents in this group work the highest number of hours per week on average (21.6 hours). They are the most likely to have a temporary or zero-hours contract (28%) and to have started their job in the last year (24%). A high proportion in this group rent their home (75%) and are the most likely of all segments to say they struggle financially (81%).

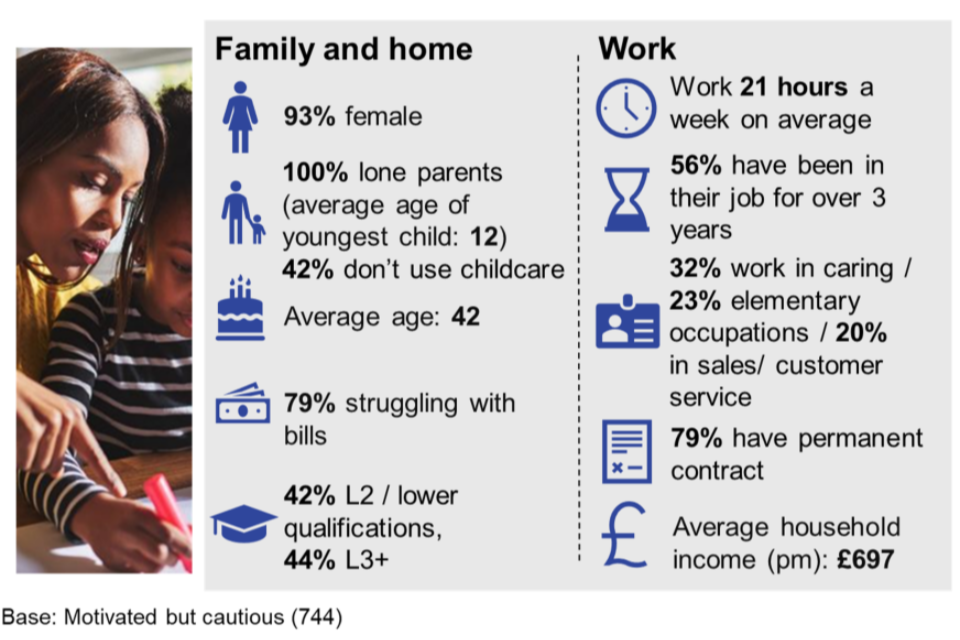

2.3.2. ‘Motivated but cautious’ segment

The ‘Motivated but cautious’ group is the largest of the segments (Figure 2.16), making up a third (33%) of the total sample of the future cohort. This group consists of lone parents who want to increase their earnings and come off benefits but are concerned that changes to their work patterns could negatively impact their finances and stability. This group feel they need to develop their skills and qualifications before they are able to progress.

Figure 2.16: ‘Motivated but cautious’ segment: key characteristics

" "

All respondents in this segment are lone parents and the vast majority are female (93%). They have a young age profile (56% are aged under 45).

Employment details are similar to the future cohort overall: they work 21 hours per week on average and around 4 in 5 (79%) have a permanent contract.

Compared with the average, ‘Motivated but cautious’ respondents are more likely to speak English as a second language (25%) and are less likely to have a limiting health condition or disability (18%). A high proportion in this group rent their home (73%) and they are more likely than the future cohort as a whole to say they struggle financially (79%).

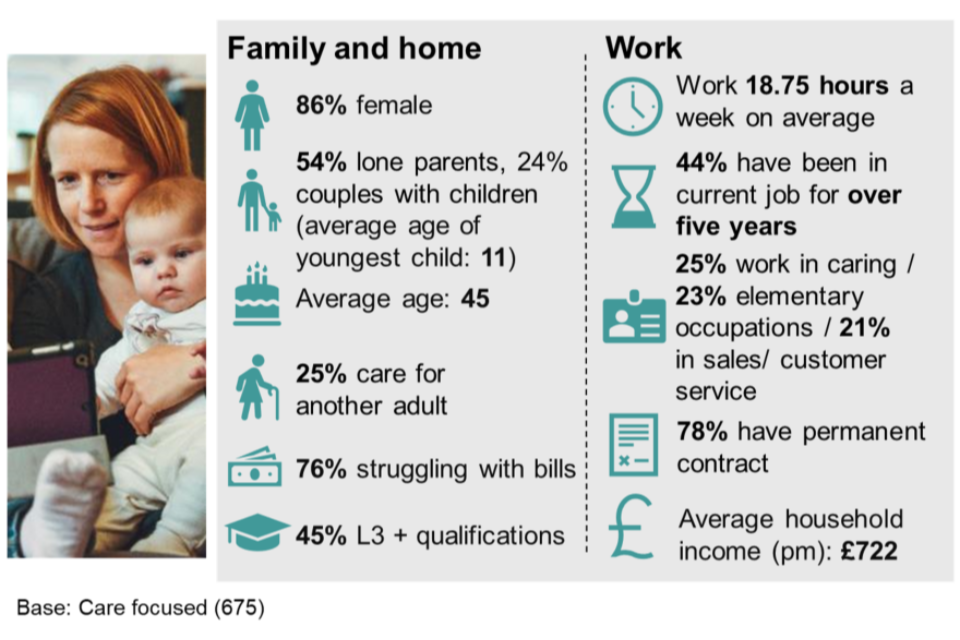

2.3.3. ‘Care focused’ segment

The ‘Care focused’ (Figure 2.17) group makes up 22% of the total sample of the future cohort. This group value stability and prioritise their caring responsibilities above progressing in work.

Figure 2.17: ‘Care focused’ segment: key characteristics

" "

They are predominantly female (86%), and more than three-quarters have dependent children (54% are lone parents, and 24% live with a partner and children). A quarter (25%) have caring responsibilities other than for children, the highest of any segment.

They work the lowest number of hours of any segment (average of 18.8). Compared with other segments, ‘Care focused’ respondents are most likely to own their home (37%).

2.3.4. ‘Stable but stuck’ segment

The ‘Stable but stuck’ segment (Figure 2.18) is the smallest, making up 12% of the total sample of the future cohort. This segment is older than average and they feel less satisfied with their job but are uncertain about what they could do to progress in work.

Figure 2.18: ‘Stable but stuck’ segment: key characteristics

" "

More than a third are male (37%), and they are older than average: 72% are aged 45 or over, including 20% aged over 60. This segment is the least likely to have dependent children (37%), and almost half are single adults without children (46%). Among those who have a partner, nearly 7 in 10 (68%) are not working, higher than the other segments.

Among those with children, use of childcare is much lower than other segments (61% do not use childcare); this is likely to reflect the age of their children (84% have a youngest child aged 12 or over).

Over half (53%) of ‘Stable but stuck’ respondents have been in their job for more than 5 years.

Compared with other segments, ‘Stable but stuck’ respondents are the most likely to have a limiting health condition or disability (40%). Their qualification levels also tend to be lower than other segments (21% have no formal qualifications).

2.3.5. ‘Stable and content’ segment

The ‘Stable and content’ segment (Figure 2.19) makes up 16% of the total sample of the future cohort. This group are the least likely to want to progress in work and are particularly likely to be reluctant to take on more hours.

Figure 2.19: ‘Stable and content’ segment: key characteristics

The majority (71%) are female, and they are older compared with the average: 13% are aged over 60 and over a third (37%) are aged under 45. Almost half (47%) live with a partner, higher than most other segments, and half (50%) have dependent children.

Qualification levels tend to be lower than other segments (22% have no formal qualifications), but they are less likely than other segments to struggle financially (60%). ‘Stable and content’ respondents are the most likely to have a permanent contract in their job (81%).

3. Attitudes towards progression

This chapter focuses on the attitudes of the future cohort towards progression in work, examining their barriers, motivation, capability and opportunities for progression. For the purposes of this study progression was defined as increasing hours or pay, or activity which could help respondents to improve their ability to progress in work in the future, such as training. Findings from the quantitative survey are presented first – at the overall level and for the different segments, followed by findings from the qualitative research.

Chapter summary

Attitudes towards current job

- respondents had high levels of satisfaction with their current job, though more so with the lifestyle elements such as work-life balance and hours than pay and opportunities for career development

Barriers to progression

- when asked if there is anything that makes it difficult for them to progress in their current job, the barriers mentioned by the future cohort are diverse, with 65% reporting at least one barrier, but no single barrier being mentioned by more than 15% of respondents. This illustrates the diverse needs among this group. The most commonly mentioned barriers are a lack of opportunities to gain promotion (15%), caring responsibilities (14%), their health (10%)

- as far as new jobs are concerned, barriers the future cohort mention are caring responsibilities (17%), their health (11%), lack of skills or qualifications (11%) and their age (8%)

- combining the 2 questions, around a third (35%) mention one barrier to progression in a new or existing job, 29% mention 2 barriers, and 17% mention 3 or more barriers

Motivation

- seven in 10 (72%) say it is important for them to increase their pay over the next 12 months and three-quarters (74%) agree that becoming self-sufficient and not receiving benefits or tax credits to top up their earnings is important, suggesting that there is widespread motivation to increase earnings

- however, respondents are less likely to say it is important for them to increase their hours (42%) or get a new job (37%). This is possibly because nearly 7 in 10 respondents (68%) agree that if they worked more hours, their home life would suffer, and 58% agree that it would be difficult for them to increase the hours they work, even if they were offered more hours. This illustrates that for this cohort any progression is likely to need to fit with their wider family commitments

- there is also a strong drive for stability, which could act as a counterbalance to motivation to progress. Over 8 in 10 (83%) agree that their biggest priority is keeping their current job rather than looking to get further at work

Capability

- self-perceived capability to progress suggests high confidence levels in ability to explore the labour market, but less confidence in skills. Around 7 in 10 (72%) say they have taken some kind of action related to progression in the past 12 months, most commonly taking a training course (34%) or speaking to their manager about progression opportunities (32%)

- respondents express fairly high levels of knowledge about their capability to progress in work; for example, 74% agree they know where to look for opportunities to progress in their work or career, and 63% agree that they feel confident about applying for a new job

- however, another 47% agree that they need to improve their skills and qualifications before they can get further at work (compared with 37% who disagree)

Opportunity

- there is broad agreement that there are limited job opportunities available that offer progression. Three in five (61%) agree that ‘jobs on offer do not pay enough to make working more hours financially worthwhile’, while more than half (54%) agree that ‘there just aren’t enough full-time vacancies for everyone at the moment’

3.1. Quantitative findings

3.1.1. Attitudes towards current job

The main reasons why respondents say they are in their current job are because they enjoy the work (37%), it fits around their childcare responsibilities (20%), they have the right skills or experience (14%), it offers a good work/life balance (12%), gives good pay (13%) or because it was the only job they could get (10%).

Figure 3.1 shows the answers given by at least 5% of respondents.

Figure 3.1: Reasons for being in current job

| Reasons for being in current job | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Enjoy the work/working with that team | 37% |

| Fits with my childcare responsibilities | 20% |

| Right skills/experience | 14% |

| Pay is good/the hours offer the money I need to support myself financially | 13% |

| Good work/life balance | 12% |

| Only job I could find | 10% |

| Accessible/close to home | 8% |

| Flexible working | 7% |

| Been there a long time | 5% |

| Health-related reasons | 5% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

These reasons for doing a particular job illustrate that motivation (enjoyment), capability (fits with childcare, having the right skills) and opportunity (the only job I could find, accessibility) are all important in determining job choices. For progression opportunities to appeal, they will also have to suit the future cohorts across these 3 domains.

Women are more likely to say they do their job because they enjoy it than men (38% compared with 31%). Men are more likely to report that they do the job they do due to their skills and experience (18%), compared with women (13%). Respondents on temporary and zero-hours contracts are also more likely to state this (21% and 18% respectively, compared with the average, 14%).

Although for all groups enjoyment is the most common reason why they do their job, lone parents are more likely that to say they do their job because it fits in with childcare responsibilities (30% compared with 20% overall).

Respondents were asked to what extent they were satisfied with various aspects of their job (or specifically their main job if they have more than one) (see Figure 3.2). Eight in ten future cohort respondents (81%) are satisfied with their job overall, and this includes 48% who are very satisfied. The ‘Stable and content’ segment (97%) and ‘Care focused’ (85%) are more likely than average to say they are satisfied with their job overall. One in ten (10%) are dissatisfied, higher among respondents from ethnic minorities (15%). These high levels of satisfaction indicate that the future cohort may be reluctant to seek changes to their job role.

Figure 3.2: Satisfaction with current job

| Aspect of job | Somewhat satisfied | Very satisfied | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job overall | 33% | 48% | 81% |

| Number of hours worked per week | 33% | 46% | 79% |

| The commute to and from work | 23% | 63% | 86% |

| Training opportunities available | 27% | 39% | 66% |

| Opportunities for career development | 28% | 29% | 57% |

| Work life balance | 34% | 46% | 80% |

| Pay, including benefits/tax credits | 40% | 24% | 64% |

| Childcare arrangements when at work | 19% | 51% | 70% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

When looking at specific aspects of work, satisfaction tends to be higher with lifestyle measures (such as hours, work-life balance and travel to work) than with progression and pay. Specifically:

- 8 in 10 (80%) are satisfied with their work-life balance. Whilst there are few differences among sub-groups on these satisfaction measures, those who have been in their job for more than 5 years are most satisfied with their work-life balance (83%). Those with children (82%) are also more satisfied with their work-life balance than those without (78%)

- a similar proportion (79%) are satisfied with the number of hours they work. Again, there are few differences, but those with no qualifications are more likely to be satisfied with the hours they work (84%). Those working under 16 hours a week (22% compared with 13% overall) and men are more likely to be dissatisfied (18% compared with 12% of women)

- over 8 in 10 (86%) are satisfied with their commute to and from work

- among those who have children, 7 in 10 (70%) are satisfied with their childcare arrangements whilst at work. Those with a non-working partner were most likely to be satisfied with this (78%)

- over 6 in 10 (64%) are satisfied with their pay (including their benefits or tax credits), with 24% dissatisfied. Those with qualifications below level 2 and those who had been in their job for less than 6 months were more likely to say they were satisfied with their pay (69% and 71% respectively). Those with level 3 or higher qualifications are more likely to be dissatisfied with their pay (29%) as are those with a non-working partner (24% compared with 17% of those with a working partner) and lone parents (26%)

- two-thirds (66%) are satisfied with the training opportunities available to them; just over half (56%) are satisfied with their opportunities for career development, with 24% dissatisfied. Those under the age of 35 or with no qualifications were more likely than average to be satisfied with their opportunities for career development (both 62%)

3.1.2. Barriers to progression

Number of barriers

Around half of respondents (49%) mention one barrier to progressing in their current job, while 11% give 2 barriers and 5% mention 3 or more. A third (34%) of respondents say they have no barriers to progression in their current job. In terms of getting a new job with better progression opportunities, 28% have no barriers, 53% have one barrier, 13% have 2 and 4% have 3 or more barriers.

Combining the 2 questions, 19% state they have no barriers, around a third (35%) mention one barrier to progression in a new or existing job, 29% mention 2 barriers and 17% mention 3 or more barriers. Figure 3.4 shows the number of barriers respondents report to progressing in either their current job and new job.

Overall, respondents with qualifications at Level 3 and above are more likely say they have 2 or more barriers (51%), when compared to those qualified to level 2 or below (45%) and those with no qualifications (34%). Those with a youngest child aged 12-15 are more like to report more than 3 barriers to progressing in a current or future job (23%, compared with 19% of those with children overall).

Types of barriers

Among the future cohort, perceptions of barriers to progression were highly diverse (figure 3.3). When asked if there is anything that makes it difficult for them to progress in their current job, the future cohort mention lack of opportunities to gain promotion (15%), caring responsibilities (14%), their health (10%), lack of opportunities for training and development (9%), lack of opportunities to increase pay or hours (8%) and not wanting to progress (8%). This reflects the diversity of this cohort in terms of education, skills, age and household composition and suggests that interventions will benefit from being tailored to these diverse needs.

Grouping the barriers helps clearer patterns of support needs to emerge. Overall, 37% mention ‘personal’ barriers (such as health or lack of skills), while 31% refer to ‘external’ barriers (lack of jobs or opportunities) and 7% mention ‘financial barriers’ such as not being able to afford training; not being able to afford to move to an area with more opportunities; having to pay more for childcare; debt or concern about losing benefits.

The main reasons respondents give as to why it is difficult for them to get a new job with better progression opportunities are again highly diverse, with no one barrier accounting for the majority. The most common barriers cited by respondents were their caring responsibilities (17%), their health (11%), lack of skills or qualifications (11%) and their age (8%). Nearly 3 in 10 (28%) say they have no barriers to getting a new job. As far as new jobs are concerned, ‘personal’ barriers feature prominently (56%), to a greater extent than ‘external’ or ‘financial’ barriers (15% and 8% respectively). Women are more likely to report financial barriers to getting a new job (13%) whereas men cite external barriers (18%).

Figure 3.3: Barriers to progression

| Barriers to progressing in current job | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Lack of opportunities for promotion | 15% |

| Caring responsibilities | 14% |

| Health | 10% |

| Lack of training/development opportunities | 9% |

| Lack of opportunities to increase pay/hours | 8% |

| Do not want to progress | 8% |

| Childcare costs | 4% |

| Lack of skills | 4% |

| None | 34% |

| Barriers to progressing in new job | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Caring responsibilities | 17% |

| Health | 11% |

| Lack of skills | 11% |

| Do not want to progress | 9% |

| Age | 8% |

| Travel costs | 5% |

| Childcare costs | 4% |

| Insufficient full-time jobs | 4% |

| None | 28% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

Combining the answers to both questions (barriers to progression in current job, and barriers to getting a new job with better progression opportunities), a quarter of respondents (24%) mention caring responsibilities as a barrier to progression, while 16% mention lack of promotion opportunities, 14% their health, 13% their lack of skills or qualifications and 11% the lack of opportunities for training or development.

One in 5 (19%) respondents say they have no barriers to either progressing in their current or a new job. Men (22%), those aged 45 or over (20%), those without children (21%) and without qualifications (25%) are most likely to say they have no barriers either to progressing in their current or a new job.

Barriers to progression: segments

The key finding relating to barriers is that respondents report a varied range of them; there is no one barrier which emerges as being experienced by the majority. This is also true within the segments, further illustrating the diversity of support needs among the future cohort. However, there is also some variability around barriers between as well as within the segments, these are as follows:

- ‘keen to progress’ respondents are more likely to cite a ‘lack of skills/qualifications’ (19%, compared with the average, 13%) and a ‘lack of opportunities for training or development’ (14% compared with the average, 11%) as barriers.

- ‘motivated but cautious’ are more likely than average to say there are a ‘lack of opportunities to gain a promotion’ at their employer (20% compared with 15% overall). This segment is more likely than average to work in ‘Caring and Personal Service’ occupations (29% compared with the average, 21%), and this may reflect that the more limited opportunities for progression in this sector

- ‘care focused’ are more likely to cite ‘caring responsibilities’ (29%) and childcare costs (7%) as being barriers. This reflects the priorities of this group, who are more likely to say they would find it difficult to work more hours or that this would negatively affect their home life

- ‘stable but stuck’ respondents are more likely than other respondents to mention their health (21%) as a barrier.

- ‘stable and content’ are the most likely to mention no barriers (in either their current job or a new job, 36%). This reflects the high job satisfaction among this segment and low motivation to progress. They may not see barriers to progression because they have little interest in doing so

3.1.3. Motivation to progress in work

This section examines respondents’ motivation to progress in work, firstly for the future cohort sample overall followed by analysis for each of the 5 segments.

Respondents are generally very satisfied with their current job(s), particularly with the number of hours they work and their work-life balance. Subsequently, whilst many would like to increase their pay, fewer want to increase the number of hours they work or change job. Few benefits are attached to working more hours or full-time whilst increasing the hours worked is seen as having a negative effect on home life and being difficult to accommodate.

Respondents who have been in their job for longer are more likely to have high satisfaction, as well as being less likely to think that increasing their hours or pay is important. Conversely, those who have moved jobs most recently appear to be more interested in progression opportunities. Household composition also influences motivation: those with younger children prioritise family life and those with older children are more open to increasing the number of hours they work.

Attitudes towards progression

Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with a number of statements about work (see Figure 3.4). Over 8 in 10 (83%) agree that their biggest priority is keeping their current job rather than looking to get further at work. This focus suggests there will be lower motivation to seek or take-up new opportunities among this group.

In terms of pay, 7 in 10 of the future cohort (72%) say it is important for them to increase their pay over the next 12 months. A similar proportion (74%) agree that “becoming self-sufficient and not receiving benefits or tax credits to top up their earnings” is important. A smaller proportion, 4 in 10 (40%) agree that “I don’t need to work more hours or earn more money because I get by okay on what I currently earn”, and respondents are more likely to disagree with this statement than agree with it (48%). This confirms that an increase in pay would be important for the future cohort. At the same time, 7 in 10 (70%) agree that “earning more would impact my benefits or tax credits”.

However, less importance is placed on increasing the number of hours worked. Four in ten (42%) say it is important to increase their hours in their current job. Respondents are as likely to disagree (43%) as agree (40%) that they would be happier and more fulfilled if they were working more hours, and they are more likely to disagree than agree that people who work full-time earn more respect (49% compared with 38%). More specifically, over two-thirds of respondents (68%) agree that if they worked more hours, their home life would suffer, and 58% agree that it would be difficult for them to increase the hours they work, even if they were offered more hours.

Getting a new job has least importance for this group. A quarter say this is very important for them to achieve this in the next 12 months and 37% that it is very or somewhat important. This suggests that progression in their current job will be most attractive to this audience.

Figure 3.4: Importance of changes to current work

| Change | Fairly important | Very important | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase hours in current job | 18% | 24% | 42% |

| Increase pay in current job | 26% | 46% | 72% |

| Get a new job | 13% | 24% | 37% |

Base: All future cohort participants (3,114)

Actions taken to progress

When asked what actions they had taken in relation to progression in the past 12 months, around 7 in 10 (72%) say they have taken some kind of action, most commonly starting or completing a training course (34%) or speaking to their manager about progression opportunities (32%). Full details are shown in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5: Actions taken in relation to progression

| Action taken | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Started or completed a training course(s) to improve your qualifications skills | 34% |

| Talked about progression opportunities with your manager | 32% |