The CASLO Research Programme

Published 18 November 2024

Applies to England

Authors

Paul E. Newton, Milja Curcin, Latoya Clarke, and Astera Brylka, from Ofqual’s Standards, Research, and Analysis Directorate.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all of our colleagues within Ofqual who have supported the CASLO research programme in so many ways.

The CASLO Research Programme

This report is part of a series that arose from Ofqual’s 2020 to 2024 programme of research into the CASLO approach:

1. The CASLO Research Programme: Overview of research projects conducted between 2020 and 2024.

2. The CASLO Approach: A design template for many vocational and technical qualifications in England.

3. How ‘CASLO’ Qualifications Work. (This was published in February 2022.)

4. Origins and Evolution of the CASLO Approach in England: The importance of outcomes and mastery when designing vocational and technical qualifications.

5. Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report A): A taxonomy of potential problems.

6. Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report B): Views from awarding organisations.

7. Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report C): Views from qualification stakeholders.

8. Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report D): Properties of qualifications from the CASLO research programme.

9. Understanding Qualification Design: Insights from the 2020 to 2024 CASLO qualification research programme.

Introduction

Over the past few years, Ofqual has invested in a programme of research into what we now refer to as the ‘CASLO’ approach to qualification design. This document is the first in a series of reports that present our findings and conclusions. It sets the scene for the remaining reports by explaining: why we embarked upon the programme, how we decided what it ought to include, and how its different strands fit together. Our programme includes 4 distinct strands:

1. descriptive – to explain what we mean by the CASLO approach to qualification design and, therefore, what we mean by a CASLO qualification

2. functional – to describe how CASLO qualifications work (in contrast to the more widely recognised family of ‘classical’ qualifications that are designed differently)

3. historical – to understand the origins and evolution of the CASLO approach within the landscape of Vocational and Technical Qualifications (VTQs) in England

4. critical – to consider criticisms that have been levelled at the CASLO approach

The purpose of the present report is simply to provide an overview of each of these strands (and the reports that arose from them). We will begin with a brief description of the CASLO approach, followed by an explanation of the nature and structure of our research programme.

The CASLO approach

The CASLO approach is a high-level template for designing qualifications. It became increasingly popular as a basis for designing VTQs in England during the 1980s and (especially) into the 1990s. We contrast it with the classical approach to qualification design, which lies at the heart of most traditional tests, exams, and qualifications in England and overseas.[footnote 1]

Traditionally, the classical approach to qualification design revolved around the idea of a syllabus content list: a document that explained the content that examiners were likely to cover in the exams that they produced. The exam syllabus provided a basis for teachers to decide what students needed to be taught. Classical exams tend to involve tasks that students respond to under controlled conditions, with task performances evaluated by examiners using mark schemes. The grade that a student is awarded depends on the total number of marks that they achieve across all of the component tasks. So, the grade standard, within a classical qualification, represents an overall level of attainment in the syllabus content area.

The CASLO approach to qualification design is different because it revolves around the idea of a set of required learning outcomes. These learning outcomes tend to look like this:

-

be able to provide a colouring service (taken from a hairdressing qualification)

-

understand health and safety legislation in a learning environment (taken from a teaching assistant qualification)

-

understand methods for generating ideas within a brief (taken from a creative practice qualification)

Each unit from a CASLO qualification represents a coherent grouping of learning outcomes, often numbering around 4 or 5 (sometimes more, sometimes less).

Intended learning outcomes are merely implied by syllabus content lists within classical qualifications, with no expectation that students ought to achieve each and every one of them. Yet, this is exactly the intention behind CASLO qualifications. Students are not deemed to have passed a unit from a CASLO qualification until they have achieved each and every one of its required learning outcomes.

Nature

We identified the 3 core characteristics that are shared by all qualifications within the CASLO family as follows:

1. unit content is specified in terms of learning outcomes (whereas classical qualification content is specified in terms of topics that need to be taught)

2. the unit standard is specified via assessment criteria for each learning outcome (whereas classical qualification standards are holistic, based on mark totals)

3. to pass each unit, a learner must acquire all of the specified learning outcomes, which we refer to as the mastery requirement (whereas classical qualifications do not make requirements concerning specific learning outcomes)

This also suggests that CASLO qualifications tend to be segmented into units, which is true, although the idea of a single-unit CASLO qualification is entirely legitimate.

Until just recently, this family had no distinguishing name. We decided to call them ‘CASLO’ qualifications because they are all designed to Confirm the Acquisition of Specified Learning Outcomes.

Prevalence

The historical strand of our research programme explains in considerable detail how and why the CASLO approach rose to prominence during the 1980s and 1990s. The first CASLO qualifications of national prominence were National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs), although General National Vocational Qualifications (GNVQs) followed closely behind. The approach was soon adopted within a variety of qualifications, including Business and Technician Education Council (BTEC) awards.[footnote 2]

The approach spread to other VTQs during the 1990s and 2000s. Importantly, toward the end of the 2000s, the approach was specified as a design requirement for all units (and qualifications) that were to be accredited to a new framework for regulating VTQs, the Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF). Ultimately, the vast majority of regulated qualifications in England were accredited to this framework, from which we can infer that, by the mid-2010s, the vast majority of regulated qualifications adopted the CASLO approach (the vast majority, but not all, of these being vocational and technical ones).

Status

Being located at the heart of both the NVQ framework and the QCF, it is fair to say that the CASLO approach remained the default, government-sanctioned approach to designing VTQs from the 1980s through to the mid-2010s. However, a number of official policy reviews during the early-2010s began to change this, as they foregrounded concerns with the approach, and with the QCF more generally. Ofqual withdrew the QCF in 2015, meaning that the CASLO approach was no longer a regulatory requirement for any qualification in England. Indeed, policies began to be introduced that (either implicitly or explicitly) proscribed the approach. In short, by the late 2010s, the approach appeared largely to have fallen out of favour with policy makers.

Our CASLO journey

Our research programme emerged organically during the late-2010s. In 2017, Ofqual published a report that explored what we meant by validity and how awarding organisations might develop validation arguments to defend the technical quality and social value of their qualifications (Newton, 2017). This emphasised the idea of building validity into qualifications, by design, and the related idea of framing qualification validation as an interrogation of design logic and design efficacy. This way of thinking about validity and validation raised questions concerning how qualifications (and the features and processes built into them) are supposed to work.

In 2018, an attempt to understand how grading works for VTQs led to a detailed, desk-based analysis of recent policies and current practices in the area (Newton, 2018). Our report identified a wide variety of divergent practices, especially within a substantial subset of the qualifications that we sampled, which adopted what we now refer to as the CASLO approach to qualification design. This raised deeper questions concerning how qualifications of this sort are supposed to work.

What became immediately apparent was that the literature on qualifications of this sort was extremely limited. By way of contrast, the technical literature on the classical approach to qualification design is extensive, international, and dates back over a century. Yet, locating a technical literature for the CASLO approach proved to be tricky. The relevant literature is perhaps most closely linked to work on criterion-referencing, from the 1970s onwards, although even this corpus is fairly niche, and it is strongly skewed towards North American concerns. The literature is also linked to work on outcome-based education and training, and to mastery learning, although these are often discussed more from a curriculum perspective than from a qualification one. And, again, this literature is primarily North American.[footnote 3]

In England, reports on the CASLO approach began to be published in education and training journals during the 1980s and 1990s. Yet, although this comprises a reasonably sized corpus of work, it tends to revolve around the (problematic) introduction of a small number of CASLO qualifications, notably NVQs and GNVQs. So, it is unclear the extent to which insights from this literature might generalise to the many and varied CASLO qualifications of the present day.

Significantly, we failed to identify technical handbooks on CASLO qualification design, which might otherwise constitute the obvious first port of call for anyone wanting to understand how qualifications of this sort are supposed to work. We located a variety of regulatory documents, which typically specified how qualifications of this sort were expected to be implemented. Yet, these documents made no attempt to explain the underlying design logic of CASLO qualifications, let alone their underlying theory. We concluded that VTQs in England – particularly those that adopt the CASLO approach – are extremely poorly documented, theorised, and researched. We decided to help rectify that situation.

Our rationale

The fact that the CASLO approach appeared largely to have fallen out of favour with policy makers by the late-2010s made 2019 a good year to take stock of it. Ofqual had withdrawn the QCF in 2015 – meaning that the approach was no longer a regulatory requirement for any qualification in England – yet we still regulated a very large number of CASLO qualifications. To regulate them as effectively as possible, particularly in the wake of policy reviews that had been critical of the QCF, we concluded that it was important to understand the CASLO approach in as much detail as possible. We therefore decided to establish a project to investigate the approach, on the assumption that the better our sector understands it:

-

the better our policy making will be

-

the better our regulatory practices will be, and

-

the better our qualification design, development, and delivery will be

Our first project

We began planning an exploratory investigation into how CASLO qualifications work in 2019, although work did not actually begin in earnest until 2020, only for progress to be interrupted by the onset of COVID-19. We selected a sample of CASLO qualifications from our register, to include a wide variety of contexts and approaches, and we adopted a 2-pronged approach to studying them, which included:

1. a desk-based review of documentation related to each qualification (including qualification specifications, centre handbooks, student guides, and so on)

2. interviews with officers from the awarding organisation responsible for the qualification

We set out to explore the principles and practices associated with CASLO qualifications through the window of quality assurance. As the project evolved, we came to articulate our central research question like this: how is it possible for an awarding organisation to remain fully accountable for each CASLO qualification that it awards despite devolving substantial responsibility for assessment processes to centres? This recognised that most CASLO qualifications tended to be based upon a continuous (or phased) assessment model, of a sort that raised quite different quality assurance challenges from centre-based assessment under the classical approach.

Recognising that CASLO qualifications are less well documented, theorised, and researched than classical qualifications, we contrasted them directly in this initial project. Our intention was to understand both how and why CASLO qualifications seemed to operate so differently from classical ones.

Although this project ended before we began planning our broader programme, we consider it to be a key part of it, constituting the functional strand. It is therefore important to note that report 2 was published in 2022, while the remaining reports were published 2 years later. The later reports develop and extend many of the ideas that were introduced in the initial one.[footnote 4]

Our research programme

Having completed our first project, it was clear that we still had a lot of territory to cover to put us in the position of comprehensively understanding the CASLO approach. For instance, we still needed to understand:

- how and why the approach had been introduced in the first place, as well as how and why it had become so dominant

- the nature of the criticisms that had been levelled against the approach within the academic literature, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s

- whether awarding organisations recognised criticisms of this sort in relation to their current CASLO qualifications, and if so then what mitigations they put in place to address them

While aspiring to a comprehensive understanding of the approach, we recognised that even a substantial research programme could only take us so far. The following section explains some of the challenges encountered when researching the CASLO approach, and how we dealt with them. It helps to explain the sorts of questions that we were able to address through our programme of research (and the sorts of questions that would need to be put on ice).

Our investigative approach

These are some of the challenges that had become apparent to us by the end of our first project:

-

many of those who were responsible for introducing the CASLO approach to England retired some time ago, so firsthand accounts are hard to come by

-

there are very few accounts that go into detail concerning the reasons why the CASLO approach was introduced, which may be linked to the fact that those who introduced it tended to be practitioners (rather than scholars) who were more focused on implementing the approach than rationalising or justifying it

-

much of the academic literature related to the CASLO approach seems to have arisen in response to the imposition of NVQs and GNVQs by government-sponsored agencies, which may help to explain why it also seems to be quite skewed against the approach

-

although there is an extensive corpus of scholarly work on NVQs and GNVQs, much of this work does not focus on the CASLO approach, per se, so even locating ‘the literature’ on the CASLO approach is tricky

-

the CASLO qualification family is extremely broad and divergent, which means that some qualifications operate very differently from others, while others operate similarly but in very different settings, both of which make it hard to reach general conclusions concerning the approach

-

because of this divergence, the idiosyncrasies of how individual CASLO qualifications work need to be unpicked in detail whenever the approach is under investigation, which makes it hard to include many CASLO qualifications within the scope of a single research project

Level of analysis

Beyond these pragmatic challenges, we also realised that we faced a more esoteric challenge, which invited us to consider whether we were ultimately researching:

1. a method for judging attainment (like a test)

2. an assessment model (like continuous centre-based assessment)

3. a type of qualification (like a GCSE)

4. a qualification model (like the classical approach)

We noted that some of the policy discussions that we had been involved in previously had a tendency to compare classical and CASLO qualifications primarily on the basis of assessment-related features, including the fact that:

-

CASLO qualifications judge attainment on a criterion-by-criterion basis whereas classical qualifications judge attainment in terms of the accumulation of numerical marks – and these different approaches to judging attainment make certain forms of quality assurance more or less viable

-

CASLO qualifications tend to be based upon continuous (or phased) assessment approaches whereas classical qualifications can more easily accommodate assessment approaches that are entirely terminal – and these different assessment models are differently vulnerable to malpractice

Although CASLO-related policy discussions often focus upon assessment-related matters, it is important to recognise that the CASLO approach is not fundamentally a method for judging attainment, nor even a model of assessment. Nor is it a type of qualification, because the CASLO family includes a wide variety of quite differently conceived qualification types. So, it is best described as a qualification model.

What the CASLO approach provides – which is true of all outcome-based approaches – is an explicit and comprehensive foundation for planning curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment. So, its implications for developing learning programmes are just as important as its implications for developing assessment procedures. Moreover, its core characteristics also have implications for pedagogy, as mastery certification necessitates mastery teaching and learning.

Reflecting on qualification design at this level of analysis invites us to ask questions like: given the purposes and cohorts that a particular qualification needs to serve, and the contexts within which it will need to operate, are those goals most likely to be achieved by adopting the CASLO approach or by adopting a more classical one? In fact, we almost never explore research questions framed at this level of analysis – the qualification model level – which makes the present programme very unusual.

Level of investigation

Although an analysis of this sort ultimately aspires to draw comparisons at the qualification model level, this depends on a great deal of groundwork having already been completed. Given the deficit of documentation, theorisation, and research related to the CASLO approach, we are still firmly in the territory of preparing that groundwork rather than conducting a comparative study. As such, the current programme is not evaluative, in the sense of pitting the CASLO approach against the classical approach, or even in the sense of evaluating the CASLO approach independently (in terms of the particular goals that it tends to prioritise). Instead, the research programme is descriptive and analytical, in the sense of describing the CASLO approach, both independently and in relation to the classical approach.

Reflecting the foundational nature of this research, our programme is oriented, in particular, toward understanding in as much detail as possible the reasons why a designer might want to adopt the CASLO approach in the first place. This means understanding the goals that are (allegedly) best achieved by adopting the CASLO approach, and the features and processes that (allegedly) best secure this. Only once we are clear on these basic presumptions can we begin to plan more sophisticated investigations and evaluations.

A plan of action

As already noted, we began planning our research programme having already completed what we now refer to as the functional strand, which set out to understand how CASLO qualifications work. So, in our report on this strand, we started to describe and to explain the CASLO approach in some detail. We continued describing and explaining the approach across the subsequent strands too. So, we decided to draw all of these insights together within a distinct descriptive strand.

Owing to the limited amount of documentation related to the origins of the CASLO approach in England – and to the almost complete absence of documentation related to its evolution – we decided that we needed to reconstruct the story of the CASLO approach as a point of reference for future policy discussions. Hence the historical strand.

We initially envisaged conducting a thorough literature review related to the CASLO approach, tracking down relevant articles by searching for references to prominent CASLO qualifications in relevant databases and libraries (including reports within academic journals, reports from the grey literature, book chapters, and so on). We anticipated that these prominent qualifications would include NVQs, GNVQs, and BTECs, in particular. We found:

-

a very large number of articles on NVQs, some of which focused specifically on issues related to the CASLO approach

-

a large number of articles on GNVQs, many of which focused specifically on issues related to the CASLO approach

-

very few medium- to large-scale evaluations of either NVQs or BTECs (but many conceptual critiques)

-

a very large number of articles on BTECs, but only a few that focused specifically on issues related to the CASLO approach

-

a small number of articles related to Technology Education Council (TEC) and Business Education Council (BEC) awards, which discussed precursors to the CASLO approach

-

a small number of articles on other CASLO qualifications providing information relevant to the CASLO approach

Reading many of these articles, and reflecting on how to synthesise their insights, we reached 2 important conclusions. First, the CASLO qualification literature is dominated by articles on NVQs and GNVQs, both of which were fairly idiosyncratic (for example, NVQs were based on an unusual competence model, and GNVQs were based on an unusual grading model, both of which were strongly criticised). Bear in mind that CASLO qualification design evolved over time in response to criticisms of these trailblazing qualifications. This makes it hard to generalise conclusions from the literature to current CASLO qualifications. Second, as noted earlier, the CASLO qualification literature is (understandably) dominated by critique of NVQ and GNVQ theory and practice. This makes it hard to be confident in the completeness of the story that it tells.

For these reasons, we decided to change tack. Instead of attempting to construct a conventional literature review, we decided to use the literature to develop an elaborated taxonomy of potential problems associated with the CASLO approach, derived from an analysis of criticisms identified within the literature. This became the first report in our critical strand.

Finally, we decided that it was important to establish how present day awarding organisations responded to criticism of this sort. So, we used our taxonomy of potential problems as a foundation for conversations with awarding organisations (and wider stakeholders) concerning the technical quality and social value of their current CASLO qualifications. We wanted to establish the extent to which they recognised the sorts of problems identified in the literature (on NVQs and GNVQs) as potential problems for their own qualifications. If they did, then we wanted to hear what mitigations they put in place to counter them. This resulted in a further 3 reports within the critical strand.

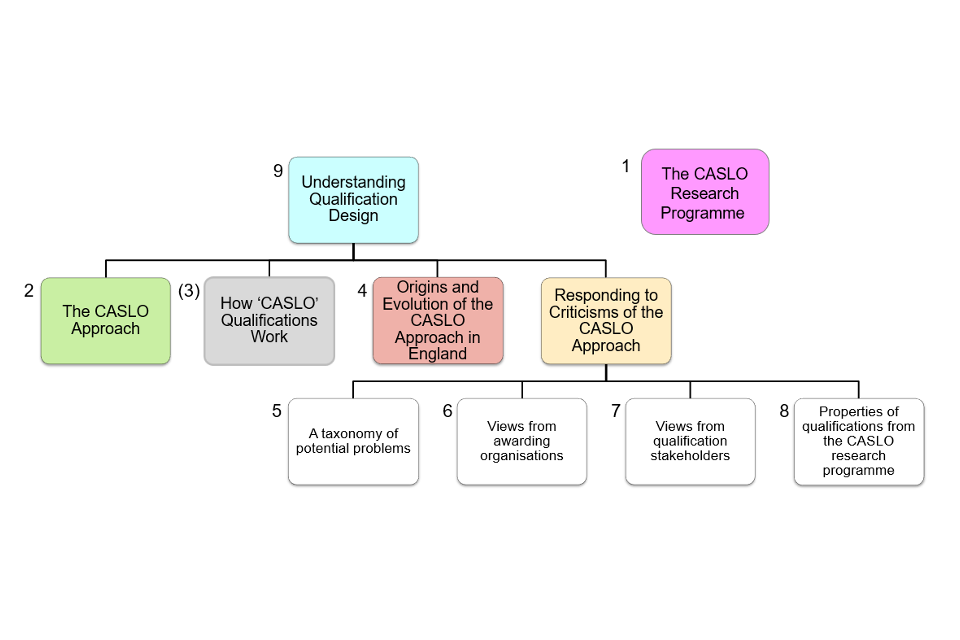

Figure 1. Reports arising from the CASLO research programme. A nested structure of programme reports, culminating in report 9.

The strands and reports

The following subsections explain the reporting structure for the programme, which is illustrated in Figure 1.

Overview

Report 1 The CASLO Research Programme: Overview of research projects conducted between 2020 and 2024

This is the present report, which simply provides an overview of each of the main strands from our research programme (and the reports that arose from them).

Descriptive strand

Report 2 The CASLO Approach: A design template for many vocational and technical qualifications in England

This is a relatively short report, which is intended to provide a full, but succinct, description of the CASLO approach. It draws upon insights from all of the other strands, particularly the historical one. It explains:

-

how (and why) we defined the approach in terms of 3 core characteristics

-

how (and why) the approach evolved, as an antidote to problems associated with the classical approach to qualification design

-

what a typical CASLO qualification looks like in contrast to a typical classical qualification, along a variety of dimensions (assessment, quality assurance, teaching and learning, and so on)

Functional strand

Report 3 How ‘CASLO’ Qualifications Work

This was our first, exploratory foray into researching the CASLO approach. We approached it from a position of having far greater insight into the operation of classically designed qualifications. So, our mode of inquiry proceeded along the lines of: if CASLO qualifications depart from the classical approach [like this], then how do they address [these] associated threats to qualification validity? We described this as a functional analysis because it felt analogous to working out how an electric engine works in contrast to an internal combustion engine or a clockwork one.

We focused specifically upon quality assurance – as a lens through which to view the entire lifecycle of a CASLO qualification – and, as noted earlier, this led to the following research question: how is it possible for an awarding organisation to remain fully accountable for each CASLO qualification that it awards despite devolving substantial responsibility for assessment processes to centres?

We observed that CASLO qualification awarding organisations operate a very different quality assurance model to classical qualification awarding organisations (with respect to their centre-based assessments). We characterised this as a hands-on partnership model – as opposed to a hands-off subcontracting one – and we identified 7 operational principles that underpinned effective quality assurance practices.

Historical strand

Report 4 Origins and Evolution of the CASLO Approach in England: The importance of outcomes and mastery when designing vocational and technical qualifications

VTQs in England have not always been based upon the CASLO approach. Indeed, prior to the 1970s, they tended to be based upon a classical approach to qualification design, like practically oriented versions of the general qualifications that they sat alongside (including O levels and A levels). So, how did the approach become so dominant within the landscape of regulated VTQs by the mid-2010s? Tracing the origins and evolution of the CASLO approach from the 1960s through to the present day, we reached a variety of conclusions, which included:

-

during the late-1980s, the CASLO approach crystallised within the original NVQ model, and soon after within the original GNVQ model

-

the roots of the CASLO approach can be traced further back, however, as qualification bodies increasingly embraced the critical role of outcomes, criteria, and mastery throughout the 1970s, building these features into a variety of VTQs

-

accreditation criteria for the NVQ framework, and subsequently the QCF, resulted in the CASLO approach achieving almost hegemonic status by the mid-2010s

We also concluded that:

-

as a high-level template, the CASLO approach only fixes a few core design features, and therefore provides little more than the foundation for a fully elaborated design template (which would be bespoke to any particular qualification type) – as such, different types of CASLO qualification might well differ significantly in terms of their validity

- the CASLO qualification family includes qualification types that have succeeded, qualification types that have failed, and qualification types that should never have been required to adopt the approach – in short, the approach is neither universally fit for purpose nor universally unfit for purpose

- the CASLO approach is not sacrosanct – despite having achieved almost hegemonic status, there are other ways of designing outcome-based qualifications and other ways of designing mastery-based qualifications – and this invites us to think creatively about the significance of outcomes and mastery when designing VTQs for the future

In fact, this strand led us to all sorts of conclusions related to: the nature of the CASLO approach, its fitness for purpose, and approaches to reforming VTQs more generally.

Critical strand

Report 5 Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report A): A taxonomy of potential problems

Report 6 Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report B): Views from awarding organisations

Report 7 Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report C): Views from qualification stakeholders

Report 8 Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report D): Properties of qualifications from the CASLO research programme

As a design template for many VTQs in England, the CASLO approach has come in for a certain amount of criticism. Indeed, the academic literature related to the CASLO approach tends to be skewed towards critical analysis. Having said that, this corpus of work is also skewed toward the earliest examples of the CASLO approach in England, notably NVQs and GNVQs. As we explain in report 4, these qualifications were poorly rolled out, with insufficient trialling and rushed implementation. They also incorporated features and processes beyond the CASLO approach that were both unusual and problematic.

So, on the one hand, the literature identifies a range of potential problems associated with the CASLO approach, and we need to take these criticisms seriously. On the other hand, it remains unclear the extent to which these criticisms can be generalised to present day CASLO qualifications. To explore this tension, we discussed potential problems identified from the literature with present day awarding organisations, to determine the extent to which they recognised them in the context of their own qualifications and, where they did, what practical steps they put in place to mitigate them.

In Study A, we trawled the academic literature in search of different kinds of criticism of the approach. We then classified these criticisms – in terms of potential problems that might threaten CASLO qualification rollout – within 3 broad categories:

1. potential assessment problems (inaccurate judgements, ineffective standardisation, and so on)

2. potential teaching and learning problems (incoherent teaching programmes, downward pressure on standards, and so on)

3. potential delivery problems (burden, and so on)

In Study B, we used the taxonomy created in study A as a basis for structured interviews with officers from a number of awarding organisations. Having disseminated the rationale for our study to all of the organisations that we regulate, we asked if any would like to take part in the study. To do so, they would need to nominate an ‘exemplar’ CASLO qualification from their qualification suite, that is, one that they believed to be particularly well suited to the CASLO approach for one reason or another. Fourteen awarding organisations volunteered to be part of this study, and we began by collating a wide range of documentary evidence related to the exemplar qualification that they nominated (specifications, handbooks, guides, and suchlike). We then interviewed officers from each of these organisations, asking them directly about each of the potential problems described in the taxonomy. Specifically in relation to their exemplar qualification, we asked:

-

whether they recognised each potential problem as a significant threat

-

if so, then what steps they took to mitigate the threat (or if not, then why not)

Generally speaking, the awarding organisations did recognise most of the potential problems from the literature, and we uncovered a wide range of mitigating strategies. We also uncovered what we described as protective factors, which awarding organisations believed helped to mitigate risks without having to establish discrete controls. For example, where assessment took place within complex, real-life settings, this was often seen as an inbuilt protection against the potential problem of atomised assessment that risked not capturing the essence of holistic competence.

Of course, this study only investigated awarding organisation perceptions of the extent to which the mitigations and protective factors effectively addressed potential problems identified within the literature. It did not evaluate the extent to which they actually were effective. To gain at least some insight into this question, for a subset of 4 (of the largest) qualifications in our sample, we conducted further interviews with qualification stakeholders, including teachers, students, and a small number of users (such as higher education admissions tutors).

In Study C, we simply wanted to triangulate the sorts of things that awarding officers were saying with the sorts of things that stakeholders also said. We were less direct in the questions that we asked our stakeholder groups (as it would not have been viable to ask them about many of the mitigations or protective factors directly). However, the sorts of things that they described (when talking about their experiences of each qualification) did chime with the sorts of things said by awarding organisation officers, which helped to validate what the officers told us.

Finally, Study D was not a distinct investigation, but simply an extended description of a subsample of the qualifications investigated within this strand, intended to illustrate the different ways (sometimes very different ways) in which the high-level CASLO design template can be operationalised.

We reported Studies B to D in substantial detail to help compensate for the lack of published documentation related to the CASLO approach in England. We intended to provide a resource for awarding organisations that wanted to reflect more deeply on how to build validity into their CASLO qualifications by design. Having said that, we do not specifically endorse the approaches adopted by these organisations within their exemplar qualifications (and we are not implying that these qualifications are somehow exemplary). After all, our research has not actually evaluated any of them in any depth. Our reports simply illustrate a variety of approaches that different awarding organisations, working in different contexts, with different learners, have judged to be effective.

Integration

Report 9 Understanding Qualification Design: Insights from the 2020 to 2024 CASLO qualification research programme

Our final report identifies and integrates the most important insights to have emerged from our research programme. Rather than attempting to synthesise findings from the other 8 reports, it develops a theoretical framework for reflecting on the effective design, development, and delivery of CASLO qualifications (specifically) and of outcome-based qualifications (more generally). Report 9 explains:

-

how far we have come in our understanding of the CASLO approach

-

profitable avenues for further research and analysis

Recommended citations

We recommend citing the 9 reports as follows:

Newton, P.E., Curcin, M., Clarke, L. & Brylka, A. (2024). The CASLO Research Programme: Overview of research projects conducted between 2020 and 2024. Ofqual/24/7153. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Newton, P.E., Curcin, M., Clarke, L. & Brylka, A. (2024). The CASLO Approach: A design template for many vocational and technical qualifications in England. Ofqual/24/7159. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Newton, P.E. & Lockyer, C. (2022). How ‘CASLO’ Qualifications Work. Ofqual/22/6895. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Newton, P.E., Clarke, L., Curcin, M. & Brylka, A. (2024). Origins and Evolution of the CASLO Approach in England: The importance of outcomes and mastery when designing vocational and technical qualifications. Ofqual/24/7156. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Newton, P.E., Curcin, M., Clarke, L. & Brylka, A. (2024). Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report A): A taxonomy of potential problems. Ofqual/24/7177. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Curcin, M., Brylka, A., Clarke, L. & Newton, P.E. (2024). Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report B): Views from awarding organisations. Ofqual/24/7162. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Clarke, L., Newton, P.E., Brylka, A. & Curcin, M. (2024). Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report C): Views from qualification stakeholders. Ofqual/24/7163. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Brylka, A., Curcin, M., Clarke, L. & Newton, P.E. (2024). Responding to Criticisms of the CASLO Approach (Report D): Properties of qualifications from the CASLO research programme. Ofqual/24/7164.Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Newton, P.E., Curcin, M., Clarke, L. & Brylka, A. (2024). Understanding Qualification Design: Insights from the 2020 to 2024 CASLO qualification research programme. Ofqual/24/7176. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

References

Newton, P.E. (2017). An Approach to Understanding Validation Arguments. Ofqual/17/6293. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

Newton, P.E. (2018). Grading Vocational & Technical Qualifications: Recent policies and current practices. Ofqual/18/6441/3. Coventry: Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation.

-

We use the term ‘classical’ to indicate that this is the ‘traditional’ or ‘standard’ approach. We do not mean to imply that it is the ‘definitive’ or ‘highest quality’ approach. ↩

-

BTEC is now a trade mark of Pearson Education Limited, but it was originally an organisation in its own right, and it was responsible for introducing BTEC awards during the early 1980s. ↩

-

CASLO qualifications are both outcome-based and mastery-based, although they represent just one approach to designing outcome-based qualifications and one approach to designing mastery-based qualifications. ↩

-

As such, they sometimes differ in how they are expressed, for example, the core characteristics are expressed less technically in the 2024 reports than in the 2022 report. ↩