Spring 2025 Immigration Rules Impact Assessment (Skilled Worker and Care Worker) July 2025 (accessible version)

Updated 9 December 2025

| Title: | Spring 2025 Immigration Rules Impact Assessment (Skilled Worker and Care Worker) – July 2025 |

|---|---|

| Type of measure: | Immigration Rules change |

| Department or agency: | Home Office and Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) |

| IA number: | HO IA 1017 |

| Type of Impact Assessment: | Final |

| RPC reference number: | N/A |

| Contact for enquiries: | Migration and Citizenship Policy, Home Office |

| Date: | 01/07/2025 |

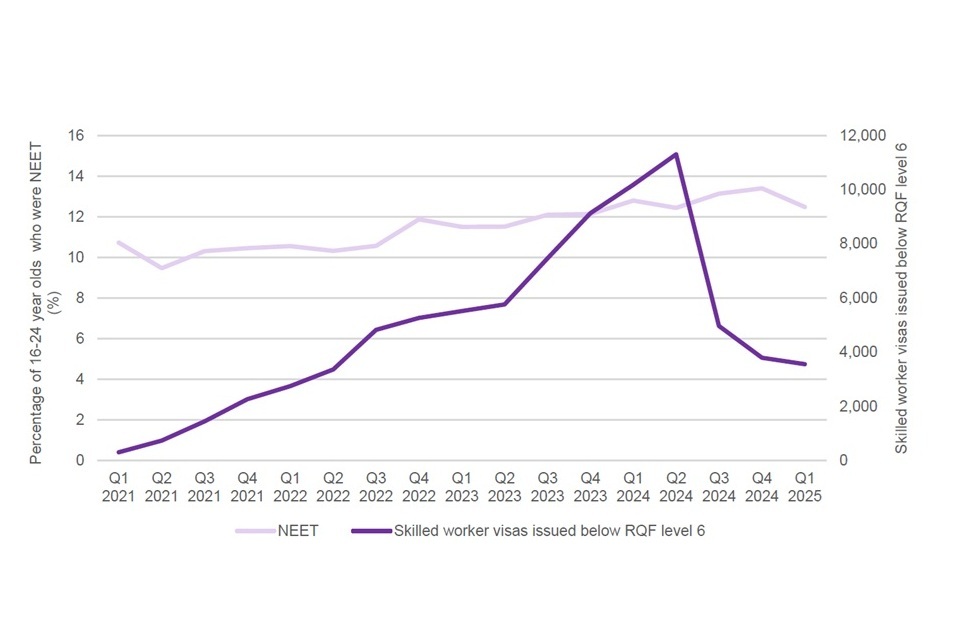

1. Summary of proposal

1. Changes are being made to implement some of the reforms to work visas set out in the white paper, “Restoring control over the immigration system”, published on 12 May 2025[footnote 1]

2. These changes will:

- Increase the skills threshold for occupations eligible for Skilled Worker and Health and Care visas from Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF) level 3 (approximately A-level) to RQF level 6 (graduate level);

- Raise salary threshold and occupational going rate requirements for Skilled Worker, Global Business Mobility and Scale-up visas in line with 2024 ASHE data;

- Close Skilled Worker entry clearance applications for care workers (SOC code 6135) and senior care workers (SOC code 6136), while maintaining in-country switching applications until 22 July 2028;

- Expand the Immigration Salary List (ISL) and introduce a new, interim Temporary Shortage List (TSL), providing time-limited access to the Skilled Worker route for occupations below RQF 6, but with no ability for applicants to bring dependants; and

- Include transitional arrangements, allowing existing Skilled Worker visa holders to continue to extend their visas, bring dependants, change employment and take supplementary employment in occupations below RQF 6, while applying the new rules to applicants from overseas and those applying to switch from other routes. These transitional arrangements will not be in place indefinitely and will be reviewed in due course.

2. Strategic case for proposed regulation

3. Levels of net migration were approximately 200,000 per year throughout most of the 2010s and have risen from 224,000 in the year to June 2019 to a record high of 906,000 in the year ending June 2023 - a four-fold increase in the space of under four years.

4. At the same time as a significant expansion in overall levels of migration, driven particularly by non-EU nationals and their dependants coming to the UK for work and study, the mix of visa holders also changed – shifting increasingly away from higher-skilled migration, and towards lower-skilled migration.

5. The RQF is a system used to categorise qualifications based on their level of difficulty and complexity. Occupations which require an RQF 6 or above skill level are deemed highly skilled (jobs that people generally need at least an undergraduate degree to perform) such as architects, and physiotherapists. Occupations that require lower RQF levels of qualification are generally quicker and easier e to undertake.

6. The Skilled Worker visa introduced in 2020 lowered the skill threshold on the route from RQF 6 down to RQF 3. In August 2020, the Health and Care Worker route was introduced and expanded in February 2022 to include the social care workforce within which roles are generally below RQF 3.

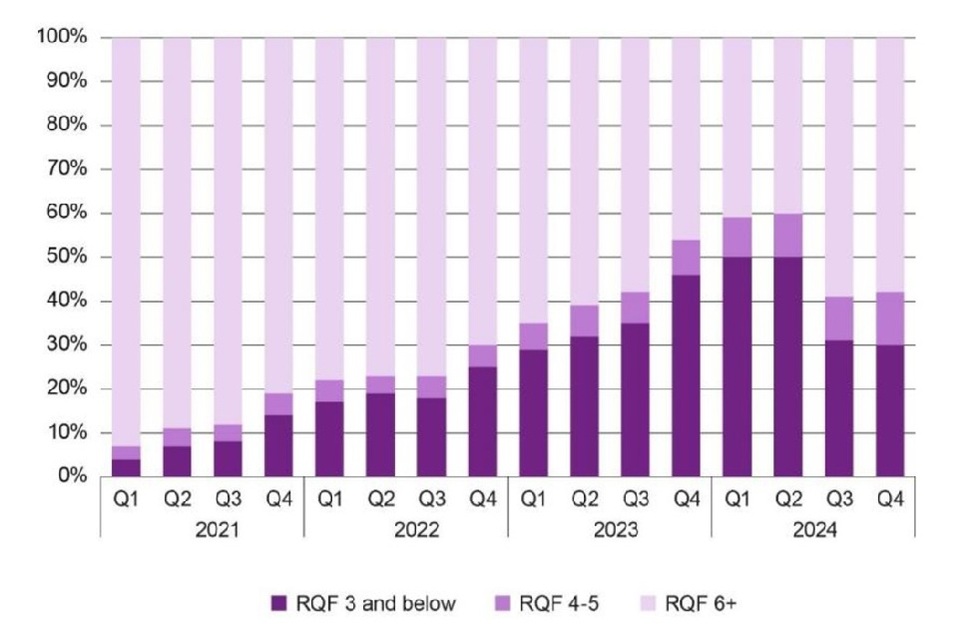

7. In 2022 on the Skilled Worker route, only 16,200 visas were issued to people taking up lower skilled jobs. By 2023, this had increased to 27,900 following increases in people coming to work in food preparation and hospitality occupations. In 2023 a further 105,000 visas were issued to those in social care occupations representing 73 per cent of Health and Care Worker visas issued to main applicants. Figure 1 illustrates the share of skilled worker visas issued in RQF 3 and below, RQF 4 and 5 and RQF 6 and above occupations.

Figure 1: Share of skilled worker visas issued in RQF 3 and below, RQF 4 to 5 and RQF 6 and above occupations

Source: Internal Home Office Analysis

8. Increases to salary thresholds in April 2024 have resulted in a decline in visas across all skill levels - but the average skill level is still lower than any year prior to 2023. Figure 2 illustrates the volume of entry clearance visas issued to skilled workers below and above RQF 6, using data after the changes to salary thresholds in April 2024. The stronger application of the genuine vacancy test for the social care sector from October 2023, based on extensive Home Office engagement with the Department for Health and Social Care, has also led to a decline in social care applications to around 7,800 in 2024, but care workers remain the only occupation eligible to come to the UK to work below RQF 3.

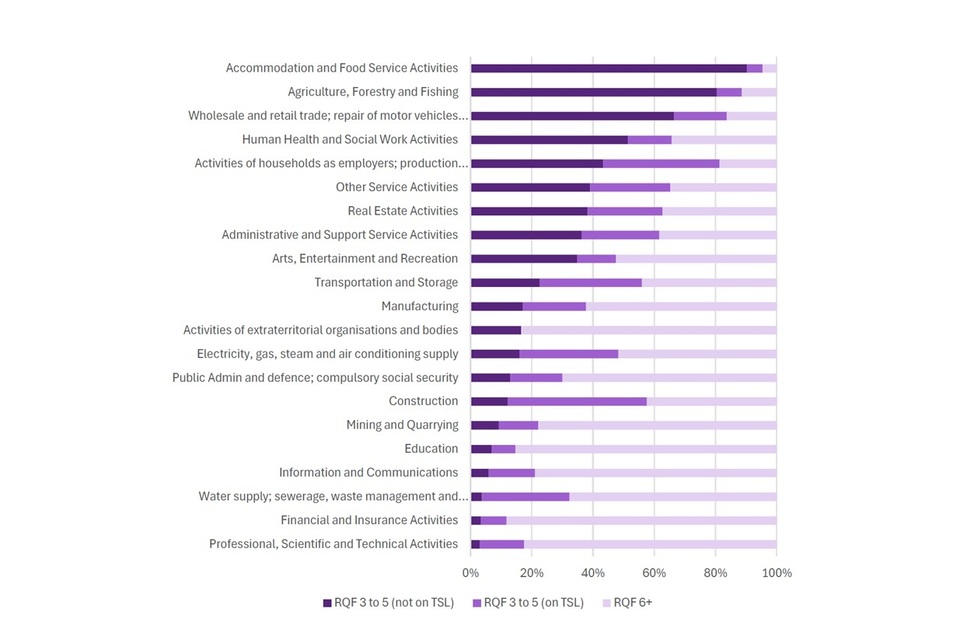

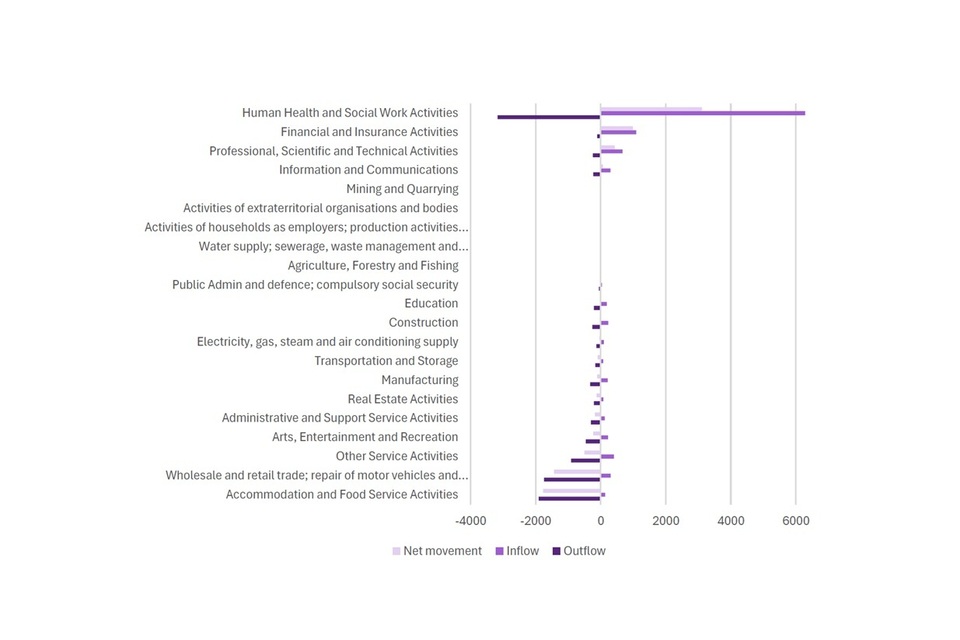

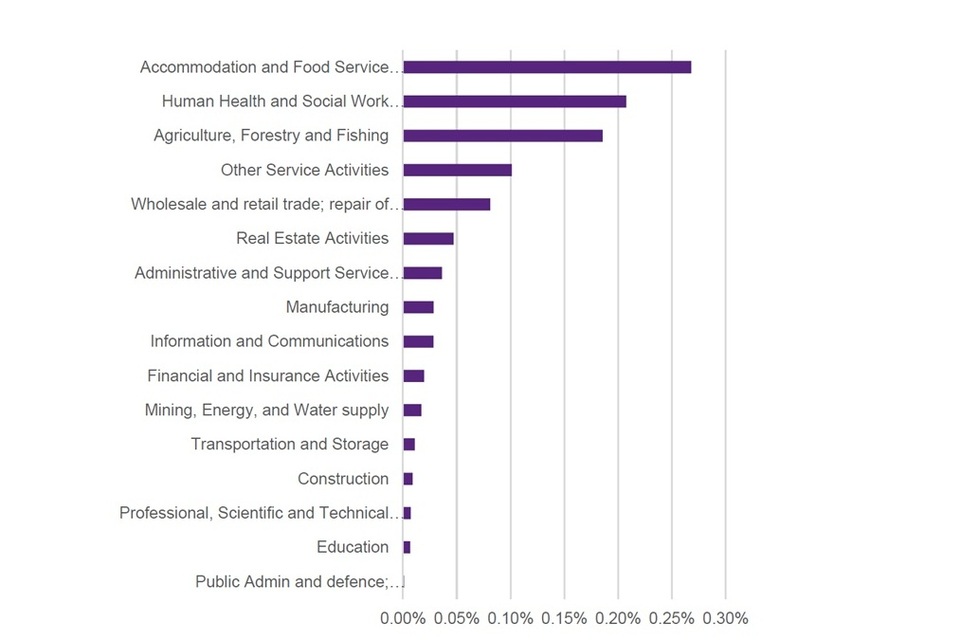

Figure 2: Skilled Workers, April to December 2024 by RQF level group, top 10 UK industries.

Source: Internal Home Office Analysis

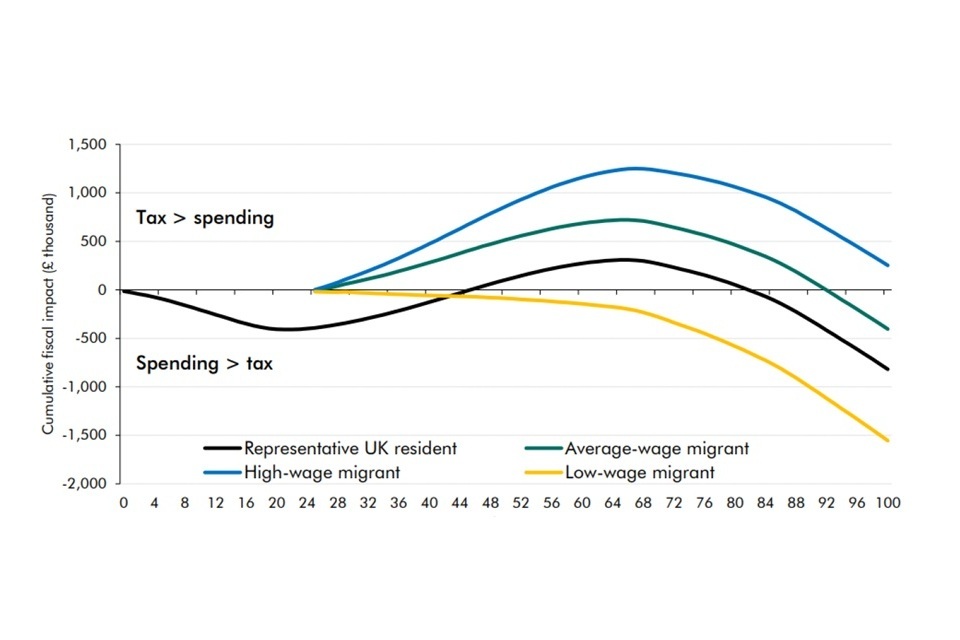

9. Highly skilled migrants can have a significant positive impact on the labour market where they are able to fill skill-shortages, and where they bring a new set of skills to complement UK workers, increasing overall productivity.

10. However, at the same time as overseas recruitment, including of lower skilled workers, rose, labour market participation by UK residents has fallen. The overall employment rate for 16 to 64 year-olds from January to March 2025 of 75.0 per cent is lower than before the COVID-19 pandemic at 75.9 per cent in January to March 2020[footnote 2], reversing the previous long-run trend of declining rates of economic inactivity.

11. In turn the percentage of young people aged 16 to 24 who are not in employment, education or training in January to March 2025 was estimated at 12.5 per cent, up from 10.7 per cent in the same period in 2021 and 11.0 per cent in 2019[footnote 3]. It is this cohort specifically who are more likely to have been employed in lower-skilled jobs. According to the 2021 Census, 96 per cent of 16 to 24 year-olds in employment were working in occupations below RQF 6 level, compared to 73 per cent for the population as a whole.[footnote 4]

12. While there will be many reasons for this trend, including pay and conditions and wider economic conditions, access to the immigration system reduces the incentives to invest in domestic skills and training. Total apprenticeship starts have fallen from 393,000 in 2018/19 to 340,000 in 2023/24.[footnote 5] Total investment in training has fallen in real terms from around £2,200 per employee in 2011 to around £1,800 per employee in 2022.[footnote 6]

13. Against this context, the strategic objectives set out in the white paper for these changes are to:

- Ensure net migration comes down so the system is properly managed and controlled.

- Link the immigration system to skills and training requirements here in the UK so that no industry is allowed to rely solely on immigration to fill its skills shortages.

14. While these changes have a significant impact on the number of people able to come to, and remain in the UK, this should be seen in the context of the record levels of net migration set out in paragraph 3, and a return closer to levels of net migration seen in the decades prior. These impacts are a reduction from this temporary peak, and not a reduction significantly below the historical trend.

15. Whilst the analysis set out in this IA quantifies first order, direct and indirect, impacts associated with the modelled reduction in migration flows, it is the second order effects which drive the rationale for these rule changes. This includes creating an immigration system which provides broader incentives for employers to upskill the domestic workforce rather than importing workers, combined with workforce strategies to strengthen the UK economy and support growth.

16. First order impacts quantified in the appraisal below include the public sector and fiscal impacts associated with the modelled reduction in migration flows, overall representing a negative NPSV. Other unquantifiable first order effects include the impacts on GDP, but also on GDP per capita. Overall, evidence suggests that whilst the modelled reduction in migration flows will have a downward impact on GDP, the impact on GDP per capita is likely to be small in scale, and the direction of impact remains uncertain.

17. As set out above, the wider rationale for changes is to incentivise employers to upskill domestic workers; the impact of which are captured in second order effects as they are not an immediate consequence of the policy. Some academic literature (set out in the analysis and evidence section in more detail), including evidence by Manning et al, suggests high levels of net migration could lead to a reduction in training participation amongst workers, with the effect more pronounced at lower skill levels.[footnote 7] This evidence suggests employers might choose hiring overseas workers as a cost-minimisation strategy, particularly where ready-trained migrant workers exist. Restricting lower skilled migration could therefore provide incentives for employers to invest in the upskilling of the domestic population, with a body of academic literature showing the positive association between investment in training and growth.

18. Whilst the analysis in this IA presents a negative NPSV – associated with the quantifiable first order effects – this must be read in the context of the potentially significant unquantifiable benefits, including the second order effects which drive the rationale for changes.

19. The measures set out in the white paper, part of which are enacted in these immigration rules, form part of a broader government policy to get people back into work, set out in the “Get Britain Working” white paper.[footnote 8] Universal Credit, and legacy benefits, are forecast by the OBR to reach £102 billion a year by 2028/29.[footnote 9] As part of this policy, the government has committed to a Youth Guarantee to support young people into education, employment, or training, and has recently commissioned an independent review into the drivers of the rise in NEETs. The Department for Education has also recently published the post-16 Education and Skills white paper, setting out the government’s strategy on skills. Skills England will play an important role in the newly formed Labour Market Evidence Group, providing advice to the government on filling skills gaps in sectors that are reliant on the immigration system. So, whilst it has not been possible to quantify the second-order labour market impacts in this IA, they form an important part of the overall government strategy to improve labour market outcomes.

20. Sensitivity analysis set out in the Risks and Sensitivity Analysis section suggests that if more than 44% of deterred migrant volumes are replaced by inactive workers under the same assumptions, the package would result in a positive NPSV. This is equivalent to a long-term increase in flow of UK nationals into employment of around 15,000 per year, or around 75,000 over 5 years, out of the current pool of around 1.6 million unemployed people in the UK between February and April 2025.

21. Without government intervention, the business-as-usual scenario would mean that businesses, including the care sector, retain access to lower-skilled migration and increase the risks of not meeting the two strategic objectives above.

22. Further detail on the assessed impact of these changes in meeting these strategic objectives are set out in the Evidence Base section.

3. SMART objectives for intervention

23. As set out above, the strategic objectives set out in the White paper for these changes are to:

- Ensure net migration comes down so the system is properly managed and controlled.

- Link the immigration system to skills and training requirements here in the UK so that no industry is allowed to rely solely on immigration to fill its skills shortages.

24. The first objective will be measurable using the bi-annual ONS publication on Long Term International Migration, the latest of which is currently available for the year ending December 2024.[footnote 10] The policy will be considered successful against the first objective if the overall level of net migration continues to fall.

25. No specific target has been set for this reduction, however this set of policies will need to be considered alongside the wider package of measures in the white paper which will be implemented in due course, many of which will contribute to this objective of reducing net migration.

26. It is more difficult to measure the success of this package of measures against the second objective, given the longer time horizon necessary for these benefits to be realised, and the breadth of the objective across the economy. However, the Labour Market Evidence Group (LME Group), as set out in the White paper, will draw on the best data available about the state of the labour market and the role that different policies should play, rather than always relying on migration. This will enable informed policy decisions to be taken. This evidence produced by this body will provide one important indicator on the success of these measures in achieving this objective.

4. Description of proposed intervention options and explanation of the logical change process whereby this achieves SMART objectives

27. As set out in Section 1, the proposed policy interventions are to:

- Increase the skills threshold for occupations eligible for Skilled Worker and Health and Care visas from RQF level 3 (approximately A-level) to RQF level 6 (graduate level);

- Raise salary threshold and occupational going rate requirements for Skilled Worker, Global Business Mobility and Scale-up visas in line with 2024 ASHE data;

- Close Skilled Worker entry clearance applications for care workers (SOC code 6135) and senior care workers (SOC code 6136), while maintaining in-country switching applications until 22 July 2028;

- Expand the Immigration Salary List (ISL) and introduce a new, interim Temporary Shortage List (TSL), providing time-limited access to the Skilled Worker route for occupations below RQF 6, but with no ability for applicants to bring dependants; and

- Include transitional arrangements, allowing existing Skilled Worker visa holders to continue to extend their visas, bring dependants, change employment and take supplementary employment in occupations below RQF 6, while applying the new rules to applicants from overseas and those applying to switch from other routes. These will not be in place indefinitely and will be subject to review in due course.

28. By their nature, these measures restrict the eligibility requirements for those seeking to come to the UK, thereby directly contributing to the objective of reducing net migration. In turn, by reducing the inflow of RQF 3 to 5 workers to the domestic labour market, the incentive for business to invest in skills and training to fill the resulting shortages increases. Further detail on these channels of impact is set in the Evidence Base section.

5. Summary of long-list and alternatives

29. The government published the Immigration white paper “Restoring Control over the Immigration System” in May 2025.[footnote 11] This paper set out the direction of travel for the Government and was explicit that the measures set out in this IA would be delivered.

30. While significant analysis was undertaken to support the development of the white paper, including consideration of other options, there was no formal long-list appraisal process undertaken as part of this IA following the publication of the white paper.

6. Description of shortlisted policy options carried forward

31. The white paper set out that a new TSL would be created to provide time limited access to the Points-Based immigration system.

32. Requirements for being on the Temporary Shortage List will include having a proper workforce strategy which aims to maximise the use of the UK workforce and includes agreed training and broader plans with skills organisations, including Skills England and the Devolved Governments. The Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) will consider the workforce strategy before providing advice to the Home Secretary, looking at issues such as:

- How far the workforce strategy is underpinned by a skills strategy

- How far it is underpinned by a commitment to work with the Department for Work and Pensions on a domestic labour strategy

- How the sector will manage the risk of exploitation of workers, particularly migrant workers in the sector and

- Whether the strategy is sufficiently ambitious.

33. In the interim, the Immigration Salary List (ISL) will contain occupations that the MAC has recently considered to be in shortage, including those on the current ISL. The ISL is published on gov.uk.[footnote 12]

34. The ISL will be supplemented by the interim Temporary Shortage List (TSL), which is published as part of the Statement of Changes in Immigration Rules at SW 6.1a[footnote 13] and will consist of occupations which meet the following criteria:

- Occupations currently eligible for the Skilled Worker or Health and Care routes, which are at RQF 3 to 5

- Within this, occupations which:

- a. Have a significant proportion of the occupation (50%+) working in any of the eight Industrial Strategy sectors (Advanced Manufacturing, Clean Energy Industries, Creative Industries, Defence, Digital and Technologies, Financial Services, Life Sciences, Professional and Business Services) or Construction, or

- b. Have otherwise been identified by the Department for Business and Trade or HM Treasury as being important to one of these sectors.

35. In this IA, no further assumptions are made on the composition of the TSL, and the interim TSL is assumed to continue throughout the appraisal period. The impacts identified, both quantified and non-quantified, will ultimately depend on the future composition of the TSL.

7. Regulatory scorecard for preferred option

Part A: Overall and stakeholder impacts

| (1) Overall impacts on total welfare | Directional rating | |

|---|---|---|

| Description of overall expected impact |

Note more detailed discussion of quantified impacts and the methods, data and assumptions underpinning them is included in the Evidence Base section. The monetised impacts quantified in the appraisal below include the public sector and fiscal impacts associated with the modelled reduction in migration flows. Overall, this represents a negative NPSV of between -£10.8bn and -£2.2bn over the appraisal period. However, second order impacts encompass how an economy reacts and adjusts to changes more widely. The wider rationale for these changes is to incentivise upskilling of the domestic workforce to support growth. If these changes have an impact on productivity this effect is very important and likely to outweigh many or most other impacts. Within this context, whilst the quantified elements in this IA reflect a negative NPSV, it is plausible that this is outweighed by productivity gains in the longer term due to broader incentives created by these measures. |

Uncertain Based on all impacts (incl. non-monetised) |

| Monetised impacts | As set out above, the monetised impacts represent a negative NPSV of between -£10.8bn and -£2.2bn over the appraisal period, with a central estimate of -£5.4bn. This impact broadly comprises one direct and one indirect impact resulting from the reduction in inflows because of these changes. Specifically: - The direct reduction in public sector revenue (Fees, IHS) equivalent to between -£0.8bn and -£0.5bn over the appraisal period - The indirect reduction in estimated changes in income tax and public service pressures, equivalent to between -£9.5bn and -£1.4bn over the appraisal period Impact assessments are intended to measure the impact on public welfare and are not an official government macroeconomic/fiscal forecast. The fiscal analysis in this IA also does not reflect the methodology used by the OBR, the government’s official economic and fiscal forecaster, to assess the impact of migration on the overall fiscal position of the UK. |

Negative Based on likely £NPSV |

| Non-monetised impacts | Significant non-monetised impacts are considered. These include non-monetised costs to businesses that are expected to occur through the appraisal period, including: - The impacts to business in adjusting to the lower level of inflows As well as non-monetised impacts, primarily to households that might be expected to occur during or beyond the appraisal period, including: - The likelihood of displacement effects and incentives for training and investment resulting in UK nationals filling vacancies - The dynamic fiscal consequences of changes in migrant stock in the long term As these non-monetised impacts represent both costs and benefits, the overall direction of the non-monetised impacts is uncertain. Further detail is set out in the Evidence Base section |

Uncertain |

| Any significant or adverse distributional impacts? | No These changes are not expected to have a disproportionate impact on small to medium businesses, specific households or on specific nations and regions of the UK. There could be an impact on specific households – for example if the labour cost component of care costs increase as a result of changes – but in the context of the overall expected impact on the ASC sector (as discussed in the Evidence Base), this impact is thought to be minimal. Further analysis, particularly on regional impacts, is set out in the Evidence Base section. |

Neutral |

| (2) Expected impacts on businesses | Directional rating | |

|---|---|---|

| Description of overall business impact | While the modelled impact on inflows is expected to be significant, usage of the Skilled Worker route in RQF 3 to 5 occupations represent a relatively small proportion of the total resident workforce. Annual out of country inflows as a share of the overall sector workforce range from around under 0.01 per cent to 0.05 per cent depending on the sector. The labour market is dynamic and, as with any change in environment, markets are expected to adjust and reallocate resources to their most productive use – at least in sectors where output and wages are primarily influenced by market forces. How employers choose to adjust, the relative ease and length of time taken to do so will depend on the specific characteristics of an occupation and firms. These adjustments could include: - Altering the ratio of labour to capital within the firm’s production, such as automating the production line where possible, and substituting capital for labour, - Freezing recruitment, or substituting for domestic inflows into the workforce - Changing production levels. - Changing location of production or outsourcing parts of the production process Each of these adjustments may come with a cost to the firm, either in the form of higher wages, higher up-front investment costs or, in some cases, lower output. While it is not possible to quantify these as the ability of an employer to respond through each of these avenues is highly firm-specific, it is likely this policy represents, at least in the short-term, an overall negative impact on business. The monetised impacts set out below are likely to be small in comparison. |

Negative |

| Monetised impacts | There is a reduction in the liability to pay for a Certificate of Sponsorship to sponsor workers in RQF 3 to 5 occupations and a reduction in the liability to pay the ISC. However, there is also a larger indirect cost for firms who choose to pay higher salaries to meet the higher salary threshold. The quantified impact on business is almost certain to be significantly smaller than the indirect costs to business set out above. |

Negative Based on likely business £NPV |

| Non-monetised impacts | Non-monetised impacts include both the adjustments costs set out above, which are likely significant, as well as any familiarisation costs for firms to the new guidance, which are expected to be minimal. | Negative |

| Any significant or adverse distributional impacts? | None identified While the ability of Small and Medium sized firms to make the type of adjustments set out above may be more limited, they are on average less reliant on the migrant workforce. It is therefore not clear that there will be significant distributional impacts between firm sizes. |

Neutral |

| (3) Expected impacts on households | Directional rating | |

|---|---|---|

| Description of overall household impact | In line with previous Home Office analysis and following recommendations made by the MAC, this IA considers the impact of the proposals on the welfare of the UK resident population; considered to be UK nationals and migrants at the point of application for naturalisation as British Citizens. There are no negative impacts on households identified, either monetised or non-monetised. If these changes to the labour market have an indirect impact on the labour market, through increases in training opportunities, investment and substitution of migrant labour with domestic labour, this may have a positive impact on the resident labour force. Further, any Social and Community Impacts arising from reductions in migrant inflows may have an impact on domestic households. As such, even though the magnitude of these unquantified benefits is uncertain, the lack of any identified costs is likely to result in a positive overall impact on households. These impacts are considered in “Non-monetised Impacts” below and in the Evidence Base section. |

Positive |

| Monetised impacts | No monetised household impacts have been identified. | Neutral Based on likely household £NPV |

| Non-monetised impacts |

Labour Market Displacement and Wage Impacts As set out in the Evidence Base section, and throughout, the wider rationale for these changes is to incentivise upskilling of the domestic workforce to support growth. While there has not been sufficient time for a significant body of evidence to be developed, there is some literature that further explores the link between high net migration and training, with evidence suggesting employers might choose hiring overseas workers as a cost-minimising strategy, particularly where ready trained migrant workers exist, avoiding the need to hire and train the local workforce. In particular, as set out in the Evidence Base section, Manning et al explore the relationship between high levels of net migration and domestic upskilling. If this set of policies have a positive impact on investment, particularly in training, which results in greater opportunities for the domestic workforce, particularly in the context of the rising level of youth unemployment, to find jobs this will have a positive impact on households. Social and Community Impacts Recent Ipsos polling (April 2025) found that 67 per cent of British people surveyed believe immigration levels are too high, with 43 per cent reporting they are ‘much too high’.[footnote 14] Respondents were also more likely to perceive that immigrants have a negative rather than a positive impact on their local community. However, Skilled Workers were viewed more positively than other migrant groups in relation to their impact on local communities, though the specific nature of these impacts was not defined. This distinction is supported by research from the Migration Observatory which found that the British public tends to differentiate between migrant types, with high skilled migrants receiving greater support, although there were some differences in views across the cohort of low skilled migrants, with more positive views towards care workers for older people for example.[footnote 15] The MAC also reviewed evidence on social and community impacts and suggested “there is no evidence that migration has affected crime. There is no evidence that migration has reduced subjective well-being though some suggestion that this varies with attitudes to migration. Overall, there is no evidence that people are less satisfied with their neighbourhoods than in the past.” but also that “the impacts of migration on communities is hard to measure due to their subjective nature which means there is a risk they are ignored“. It is therefore uncertain whether there will be material impacts on social and community cohesion. |

Positive |

| Any significant or adverse distributional impacts? | This will benefit across a broad range of UK households where firms train domestic workers. | Positive |

Part B: Impacts on wider government priorities

| Category | Description of impact | Directional rating |

|---|---|---|

| Business environment: Does the measure impact on the ease of doing business in the UK? |

There is likely to be a cost to business over this appraisal period due to the adjustment costs set out above. However, if these policy proposals result in an increased pool of skilled labour and an increase in overall productivity, this could represent an overall net benefit to business in the long-run. | Neutral |

| International Considerations: Does the measure support international trade and investment? |

There are a number of channels through which immigration may affect trade and, in general, the external literature finds a positive relationship between the stock of migrants and trade However, the expected reduction in migrants in any appraisal year as a result of the preferred option is small compared to the total stock of migrants resident in the UK. Therefore, any trade impacts are be expected to be small. |

Neutral |

| Natural capital and Decarbonisation: Does the measure support commitments to improve the environment and decarbonise? |

No meaningful impacts have been identified. | Neutral |

8. Monitoring and evaluation of preferred option

36. The impact will be monitored by the Home Office, with support as appropriate from other government departments. This will be included as part of ongoing evaluations of the Skilled Worker and Health and Care routes.

37. A first-wave evaluation of the Skilled Worker and Health and Care routes was completed and published in May 2025. The research provided insights into the motivations, experiences, and activities of visa holders and sponsors, and was used to inform White paper proposals. A second-wave evaluation is planned to capture and assess the impact of policy changes and the extent of any post-implementation behavioural shifts.

38. The Home Office also publishes migration statistics quarterly, including for the Skilled Worker and Health and Care routes, and by occupation which will also provide evidence on the impact of these changes on inflows.

39. The Home Office will also maintain open lines of communication with applicants via email and may also receive feedback as part of its normal visa issuing processes, through its public enquiry lines, and through formal correspondence with interested parties.

40. In parallel, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) monitors the adult social care workforce capacity through regular analysis of national workforce data, including information from Skills for Care’s Adult Social Care Workforce Data Set (ASC-WDS), the Capacity Tracker data collection and insight tool, and intelligence from key sector partners. This monitoring helps assess trends in recruitment, retention, and vacancy rates across the sector, and provides contextual evidence on the broader impact of immigration policy changes on the care workforce. Insights from this analysis support ongoing policy development.

9. Minimising administrative and compliance costs for preferred option

41. Administrative and compliance costs as a result of these changes are expected to be negligible. While there may be some small familiarisation costs being placed on Immigration Advisors and Lawyers, no additional compliance burdens are identified for UK businesses or citizens as any costs associated with complying with the Immigration Rules remain unchanged beyond reducing the scope of those eligible for the routes.

10. Main assumptions / sensitivities and economic / analytical risks

42. Further detail on the analysis presented in this IA is set out in the Evidence Base section below. This sets out the methods used to estimate potential impacts of the policy option, outlines the assumptions used and the sources of assumptions, explains the limitation of analysis and where well evidenced quantification of impacts has not proved possible has discussed impacts qualitatively.

43. The monetised impacts quantified in the appraisal below include the public sector and fiscal impacts associated with the modelled reduction in migration flows. The analysis presented for these factors has used ranges to illustrate the impact from varying important assumptions, and explanation of the inherent uncertainty.

44. Despite the use of ranges, the potential future volume of applicants who would have come to the UK in RQF 3 to 5 jobs and to work in care in the absence of these policy changes could reasonably be outside these ranges. Numerous external factors that drive the demand for people to come to the UK could have resulted in significantly more, or fewer, people wishing to come to the UK on these routes, and therefore a significantly larger, or smaller, impact resulting from the policy changes.

45. This impact is compounded by the potential for ineligible applicants to be displaced into other RQF3-5 occupations that remain on the TSL.

46. This IA illustratively assumes that 10 per cent of out of country and 20 per cent of in-country applicants who would have come on ineligible RQF 3-5 occupations find an alternative RQF 3-5 job rather than not come to, or leave, the UK.

47. Sensitivity analysis has been undertaken in the Risks and Sensitivity Analysis section to quantify the impact on the NPSV if a greater (50 per cent for both out of country and in country applicants) or a lower (0 per cent) proportion of applicants are displaced into alternative RQF 3-5 roles.

48. Further, as noted throughout, second order impacts encompass how an economy reacts and adjusts to changes more widely. The wider rationale for these changes is to incentivise upskilling of the domestic workforce to support growth. If these changes have an impact on productivity or on the substitution towards native employment this would be very important and could outweigh many or most other impacts.

49. Within this context, whilst the quantified elements in this IA reflect a negative NPSV in the central case, it is plausible that this is outweighed by productivity gains in the longer term due to broader incentives created by these measures.

50. It is not possible to mitigate this risk in the estimation of the NPSV, but it reflects the largest source of uncertainty. The long-term economic impact of this policy may be significantly different to what it has been possible to quantify and if there is sufficient economic adjustment, the overall economic impact may be positive.

51. However, to address this, sensitivity analysis has been undertaken in the Risks and Sensitivity Analysis section to quantify the impact on the NPSV if the policy changes result in an illustrative increase in employment of UK nationals.

52. Further detail on both the monetised and non-monetised elements, and further discussion on this risk is set out in the Evidence Base section below.

Declaration

| Department: | Home Office |

|---|---|

| Contact details for enquiries: | Migration and Citizenship Policy, Home Office |

| Minister responsible: | Minister Mike Tapp |

I have read the Impact Assessment, and I am satisfied that, given the available evidence, it represents a reasonable view of the likely costs, benefits and impact of the leading options.

Signed:

Date: 8 December 2025

Summary: Analysis and evidence

For Final / Enactment Stage Impact Assessment, please finalise these sections including the full evidence base. For a Consultation Stage Impact Assessment, these sections can be in less detail with evidence gaps highlighted.

| Price base year: | 2025/26 |

| PV base year: | 2025/26 |

Costs (£m)

| 1. Business as usual (baseline) | 2. Do-minimum Option | |

|---|---|---|

| Low | NA – no change in relation to baseline | £7.0 billion |

| High | NA – no change in relation to baseline | £14.4 billion |

| Best | NA – no change in relation to baseline | £9.6 billion |

| Non-Quantified Impacts | N/A | Additional non-quantified costs are likely to be incurred by business in adjusting to the reduction in migrant labour. How employers choose to adjust, the relative ease and length of time taken to do so will depend on the specific characteristics of an occupation and firms |

Benefits (£m)

| 1. Business as usual (baseline) | 2. Do-minimum Option | |

|---|---|---|

| Low | NA – no change in relation to baseline | £4.8 billion |

| High | NA – no change in relation to baseline | £3.7 billion |

| Best | NA – no change in relation to baseline | £4.2 billion |

| Non-Quantified Impacts | N/A | Second order impacts encompass how an economy reacts and adjusts to changes more widely. The wider rationale for these changes is to incentivise upskilling of the domestic workforce to support growth. If these changes have an impact on domestic employment or productivity this effect is very important and could outweigh quantified impacts |

Net present social value (£m)

| 1. Business as usual (baseline) | 2. Do-minimum Option | |

|---|---|---|

| Low | NA – no change in relation to baseline | -£2.2 billion |

| High | NA – no change in relation to baseline | -£10.8 billion |

| Best | NA – no change in relation to baseline | -£5.4 billion |

| 1. Business as usual (baseline) | 2. Do-minimum Option | |

|---|---|---|

| Public sector financial costs | NA – no change in relation to baseline | Public sector financial costs are included in the NPSV as changes to visa fee, IHS and ISC revenue. These are set out in detail in the Evidence Base section. |

| Significant un-quantified benefits and costs | NA – no change in relation to baseline | The wider rationale for changes is to incentivise employers to upskill domestic workers; the impact of which are captured in second order effects as they are not an immediate consequence of the policy. Academic literature (set out in the analysis and evidence section in more detail), including evidence by Manning et al, suggests high levels of net migration could lead to a reduction in training participation amongst workers, with the effect more pronounced at lower skill levels. This evidence suggests employers might choose hiring overseas workers as a cost-minimisation strategy, particularly where ready-trained migrant workers exist. Restricting low skilled migration is therefore likely to provide incentives for employers to invest in the upskilling of the domestic population, with a body of academic literature showing the positive association between investment in training and growth. Whilst the analysis in this IA presents a negative NPSV – associated with the quantifiable first order effects – this must be read in the context of the potentially significant unquantifiable benefits, including the second order effects which drive the rationale for changes. |

| Key risks | NA – no change in relation to baseline | Analysis presented in this IA has set out the methods used to estimate potential impacts of the policy option, outlined assumptions used and the sources of assumptions, explained limitation of analysis and where well evidenced quantification of impacts has not proved possible has discussed impacts qualitatively. Analysis presented has used ranges to illustrate the impact from varying important assumptions such as baseline volumes and elements of fiscal impacts. However there remain two key channels of impact not captured in the range of quantified impacts– that a significant proportion of in-country applicants are displaced onto other routes and that there is a significant increase in domestic employment as a result of any increase in training and investment. While the former remains an unquantified risk, the latter is set out in the sensitivity analysis below. |

| Results of sensitivity analysis | NA – no change in relation to baseline | If 50 per cent of future ineligible inflows are replaced by domestic labour, as a result of increases in training and investment by domestic firms, this would represent an additional benefit of £6.2bn in the central case (5 year PV, 2025/26 prices), not currently included in the NPSV. This would change the overall NPSV to a positive £0.8bn. The tipping point for the NPSV to become positive would assume around 44% of jobs are filled by domestic employment. |

Evidence base

Analytical Framework

1. An analytical framework is used to assess the impact of the first order effects associated with policy changes. As set out above, the analysis must be read in the context of the second order effects, which underpin the rationale for changes, but are unquantifiable. A discussion on these second order effects is included in the wider impacts section.

2. The framework for quantifying first order effects starts by constructing a baseline which estimates potential future migrant flows in the absence of any policy intervention, against which the policy options can be assessed.

3. Policy proposals are then modelled on this baseline to estimate how migrant flows may change as a result. These results are used to assess the population impact, which forms the basis for estimating the wider economic impacts. These principles apply both to where impacts can, and cannot, be quantified. Analysis assumes compliance from both migrants and employers. As such all discussion of flows and impacts do not consider illegal or irregular activity.

4. In line with previous Home Office analysis and following recommendations made by the MAC, this IA considers the impact of the proposals on the welfare of the UK resident population; considered to be UK nationals and migrants at the point of application for naturalisation as British Citizens. Determinants of this impact will include the estimated number of migrants coming to or leaving the UK under the policies, the characteristics of the migrants in scope (for example their age, income and health) and the choices and services available to them when in the UK.

5. Analysis is presented across a 5-year appraisal period from the start of 2025/26 financial year onwards. As noted throughout, it is not possible to quantify the main strategic objective of this set of policies, to upskill domestic workers. Given this limitation is likely to impact the NPSV more in the longer term when these benefits would be realised, a shorter 5-year period has been chosen, with a greater commitment to monitor and evaluate the extent to which this strategic objective is being met.

6. Adjustments are made for the implementation dates of individual policies which may not perfectly align to the financial year. Information is presented in 2025/26 prices and a 3.5 per cent discount rate is applied where appropriate, in line with HM Treasury Green Book guidance[footnote 16]. Where needed, GDP deflators have been used to adjust price years and salary information has been uplifted by real productivity growth.

7. Where necessary, information on the current operation of the Skilled Worker and Health and Care routes (including for Care Workers) is drawn from the 6 month period to March 2025. This is because significant changes were made to these routes in April 2024, and the impact of these changes was not immediate. This 6-month period is therefore likely to best reflect the operation of the routes once the effects of the Spring 2024 immigration rules changes had begun to stabilise, and in the absence of the Spring 2025 rules changes.

8. First order impacts include immediate, both direct and indirect, effects associated with modelled reductions in migration flows. These impacts are quantified in the appraisal under the following categories:

- Labour market impacts – this occurs due to the policies closing the Skilled Worker route to certain occupations and deterring some individuals for whom dependants will no longer be permitted. Sector-specific impacts relative to current workforce volumes are additionally quantified.

- Tax income and public services pressure - these arise from changes in volumes, and the characteristics of the cohort estimated. Changes in volumes result in fewer people residing in the UK, reducing tax income and public services pressure. Increased salaries offered by employers increases tax income. This indirect impact falls to the public sector.

- Fee and Charge revenue and processing cost impacts – these arise from changes in volumes, and the resulting change in visa applications / grants which affect the revenue and processing costs in these areas. This direct impact falls to the public sector.

9. Non-quantified impacts are discussed in the Cost Benefit Analysis section. This includes a discussion on other first-order impacts associated with the reduction in flows that have not been quantified in the appraisal, including impacts on GDP, but also on GDP per capita.

10. The wider rationale for these rule changes is to create an immigration system which provides incentives for employers to upskill the domestic workforce rather than importing workers, combined with workforce strategies to strengthen the UK economy and support growth. Although these are not an immediate consequence of the policy – and are therefore considered second-order impacts materialising throughout but also beyond the appraisal considered in the IA – they are likely to be substantial and are discussed in the wider impacts section. Therefore, whilst the IA sets out an overall negative NPSV, this must be read in the context of the significant unquantifiable benefits, including the second order effects of changes on growth which drives the rationale for changes.

Impact on volumes

Baseline Volumes

11. This section outlines the volume of visas issued under each of the affected routes in the absence of the policy changes. Discussion of estimated volumes within policy scenarios are compared to these counterfactual baselines.

12. The baseline is based on Home Office internal estimates of demand and should be considered as indicative. Estimates around future visa applicants’ behaviour is uncertain. Projections of main applicant and dependant visa demand use recent trends in volumes to estimate future volumes and are revised on an ongoing basis. The Home Office estimate applications up to the end of the 2028/29 financial year and the IA assumes that the baseline volumes remain constant at 2028/29 levels until the end of the appraisal period.

13. These volumes are reduced by 25 per cent in the low scenario and increased by 25 per cent in the high scenario to provide an illustrative range which accounts for uncertainty in future volumes. The MAC highlights that “migration is very susceptible to shock events which are, by their very nature, hard to predict, such as economic cycles, military conflict and policy changes. Changes in migration flows can be subject to extreme short-term fluctuations”.[footnote 17]

14. Grant rates, based on outcomes observed in the 6 months to March 2025 within Home Office management information, are applied to these application projections to estimate granted visa projections. As the grant rate varies considerably by occupation (for example, over the period, 42 per cent of SOC 5434 “Chefs” applications were granted, as compared to 96 per cent of SOC 2133 “IT business analysts”), and the policy primarily affects only a subset of occupations, this calculation is done at the occupation specific level, but estimates are provided in Table E1 below for the routes as a whole.

Table E1. Grant Rates for Skilled Worker visa routes, by previous location (In and Out of Country), October 2024 - March 2025. Main Applicants.

| Route | Grant Rate |

|---|---|

| Out of Country - Skilled Worker | 72% |

| In Country - Skilled Worker | 97% |

| Out of Country - Health & Care | 95% |

| In Country - Health & Care | 82% |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

15. Combining the application demand estimates with the grant rates above, by occupation, Table E2 sets out the baseline annual visas issued by route. The Health and Care figures below do not include those in Care Worker occupations so are additive to the Care and Senior Care Worker volumes presented. Table E2 only considers In-Country visas issued to those switching onto the route, as those extending are assumed not to be affected by the policy changes.

16. The volumes of dependants estimated on the Skilled Worker and Health and Care route are estimated via two steps. The first takes the projected demand estimates for out-of-country dependants, assigning these predominantly to out-of-country main applicants aside from a share assigned to in-country main applicants (capturing out-of-country dependants joining main applicants already in the UK). The second step estimates the dependant ratio for those switching onto the routes from in-country. This ratio is less than the Skilled Worker and Health and Care route averages due to this cohort predominantly switching from the Student and Graduate routes.

Table E2. Baseline visas issued on Skilled Worker visa routes, by previous location (In and Out of Country) and financial year. Central scenario. Main applicants and dependants.

Out of Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | 36,000 | 36,000 | 37,000 | 36,000 |

| Dependant | 37,000 | 38,000 | 39,000 | 38,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | 13,000 | 13,000 | 13,000 | 13,000 |

| Dependant | 26,000 | 26,000 | 27,000 | 26,000 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | 7,000 | 7,000 | 7,000 | 7,000 |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

In Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | 41,000 | 41,000 | 41,000 | 41,000 |

| Dependant | 29,000 | 29,000 | 29,000 | 29,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | 8,000 | 8,000 | 8,000 | 8,000 |

| Dependant | 9,000 | 9,000 | 9,000 | 9,000 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | 21,000 | 21,000 | 21,000 | 21,000 |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

Note: estimates in 2028/29 are flatlined over the remainder of the appraisal period, so for brevity the table presents annual application estimates up until this year. Care and Senior Care Workers are removed from the wider Health and Care estimates

17. Since March 2024, care workers who apply out of country, or switch in country onto the Health and Care route are ineligible to bring dependants.[footnote 18] Existing care workers in the UK, including those applying to extend their stay, remain eligible to bring dependants. As internal insight suggests many existing care workers have continued to bring new out-of-country dependants, it is necessary to apportion the overall dependant volume between care workers and the remaining Health and Care route.

18. In the absence of data matching dependants to occupation, the overall dependant to main applicant ratio for the Health and Care route is applied to existing care workers, with the remaining dependants are assumed to be accompanying the remaining Health and Care occupations. As it will not be possible for new care workers to bring dependants, the volume that have been apportioned to care occupations are not included in the baseline above.

Policy Impact on Volumes

RQF 3 to 5 Restrictions on Skilled Worker and Health and Care

19. The proportion of those on the Skilled Worker and Health and Care routes below the proposed RQF 6 skills threshold are first estimated using Home Office administrative data. Whilst the policy impacts assessed in this wider section (RQF 3 to 5 restrictions, dependant restrictions and raising the salary threshold requirements) all come in concurrently, the RQF 3 to 5 restriction is the most significant policy change and so is modelled first. Table E3 below sets out the share of visas issued on each route between October 2024 and March 2025 estimated to be below RQF 6+, as well as the share of the RQF 3 to 5 visas issued in occupations not on the initial TSL or ISL which are exempt from any restrictions. After December 2026, when RQF 3 to 5 roles on the ISL are removed, the share of visas issued in occupations on the ISL are assumed to be no longer exempt from the restrictions. By combining these figures, Table E3 sets out the share of each route which are assumed to be affected by the policy. For Care and Senior Care workers, 100 per cent of the occupation is assumed to be restricted.

Table E3. Skill-level and proportion not on TSL by occupation for visas issued on Skilled Worker visa routes October 2024 to March 2025. Main Applicants.

| Route | (1) RQF 3 to 5 | (2) RQF 3 to 5 not on TSL or ISL | (3) RQF 3 to 5 not on TSL | (1) * (2) Policy Impact (until end of Dec 2026) | (1) * (3) Policy Impact (Jan 2027 onwards) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out of Country - Skilled Worker | 41% | 53% | 55% | 22% | 23% |

| In Country - Skilled Worker | 55% | 62% | 62% | 34% | 34% |

| Out of Country - Health & Care | 8% | 43% | 93% | 3% | 7% |

| In Country - Health & Care | 62% | 66% | 98% | 41% | 59% |

| Out of Country - Care and Senior Care Workers | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 100% |

| In Country - Care and Senior Care Workers | 100% | 0% | 0% | 100%* (From 2028) | 100%* (From 2028) |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

20. This is applied to the volumes in Table E2 to give an estimate of the flow of migrants estimated to no longer arrive or remain in the UK as a result of the increase in the skills threshold. This analysis assumes any applicant who would otherwise have applied to switch onto the Skilled Worker or Health and Care routes who is now unable to do so leaves the UK.

21. Of those affected by the restrictions, it is likely that some will have sufficient skills to find an alternative RQF 3 to 5 role to come to or remain in the UK. The ONS’s occupation-level assessment of skills substitutability is used to estimate transferability from ineligible RQF 3 to 5 roles to those remaining eligible via the TSL or ISL (until December 2026).[footnote 19] A minimum transferability score of 96 per cent is applied, along with demand constraints on a small number of occupations based on UK median salary data against route thresholds. An estimated 34 per cent of those in now-ineligible roles on the Skilled Worker route and 36 per cent of those in now-ineligible roles on the Health and Care route are assumed to find an eligible job in a different occupation, on a similar salary, and are therefore removed from the analysis. Post-December 2026, when RQF 3 to 5 roles on the ISL are removed, these percentages are respectively 32 per cent and 5 per cent.

22. Of the remaining cohort, an estimate is made of the volume who may switch into care. Table E4 shows the out-of-country restrictions on Care worker occupations are estimated to lead to a reduction in around 7,000 migrants per year in these roles. Assuming sufficient motivation to remain in the UK, an in-country migrant with insufficient skills transferability to displace into an alternative RQF 3 to 5 role (as discussed above) may feasibly displace into a Care worker job until the in-country Care worker restrictions are introduced in 2028. The Skilled Worker route evaluation is used to estimate the proportion who, motivated by a desire to remain in the UK, could prepare for and seek a Care worker job.[footnote 20] The reduction in out-of-country migrants to care roles is viewed as the absolute demand constraint for this specific displacement effect.

23. This adjustment is very uncertain and should be considered illustrative. Sensitivity analysis has therefore been undertaken in the Risks and Sensitivity Analysis section to assess the impact of a greater or lower proportion of applicants displacing into alternative roles.

24. Long term, it is likely that rather than being unable to switch in-country, a proportion of applicants will instead choose not to come to the UK in the first place if they know it is not an option to switch into RQF 3 to 5 or Care or Senior Care employment. This could have a knock-on consequence, particularly on the UK education sector, which is not quantified in this IA.

Table E4. Change in visas issued on Skilled Worker visa routes as a result of the skill level and care worker policy changes, by previous location (In and Out of Country) and financial year. Central scenario. Main applicants and dependants.

Out of Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -5,000 | -7,000 | -8,000 | -7,000 |

| Dependant | -4,000 | -6,000 | -6,000 | -6,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | 200 | 200 | -100 | -100 |

| Dependant | -400 | -1,000 | -1,000 | -1,000 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | -5,000 | -7,000 | -7,000 | -7,000 |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

In Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -6,000 | -9,000 | -9,000 | -9,000 |

| Dependant | -2,000 | -3,000 | -3,000 | -3,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | -200 | -1,000 | -4,000 | -3,000 |

| Dependant | -100 | -500 | -2,000 | -2,000 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | 3,000*** | 5,000*** | 7,000*** | -12,000** |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

Note (1): estimates in 2028/29 are flatlined over the remainder of the appraisal period, so for brevity the table presents annual application estimates up until this year. *The policy is assumed to be implemented from August 2025, and so will only affect seven months of 2025/26 ** As the policy on in-country care workers also commences part-way through 2028/29, this is only a part-year figure. The full annual figure for 2029/30 and beyond is 21,000. Note (2): the substitution effect set out in paragraph 20 is modelled to result in a small volume of care workers moving into RQF 3-5 occupations. As they will not remain in Care and Senior Care, these substituted volumes are considered as reduction in volume in this sector in this table but are captured in subsequent modelling.

Note (3): ***In-country switching is only permitted for Care and Senior Care through to 2028 for those who have worked in the sector for 3 months or more. For the purposes of this modelling no impacts are modelled for in-country switching through to 2028. While some switchers may not be eligible under these rules, behavioural responses are expected where those intending to switch into care or senior care work after the Student or Graduate route will look to secure work for 3 months before they switch so that they can meet new requirements.

Dependant Restrictions on RQF 3 to 5 Skilled Worker and Health and Care occupations

25. The second policy change that is layered on top of this impact the restriction on those in exempt RQF 3 to 5 occupations bringing dependants. The 2025 Home Office Evaluation of the Skilled Worker route is used to estimate the proportion of Skilled Worker route users who bring dependants (40 per cent on the Skilled Worker route and 64 per cent on the Health and Care route) and the proportion of those who brought dependants who may not have come to the UK if they were unable to do so (67 per cent on the Skilled Worker route and 53 per cent on the Health and Care route ).[footnote 21]

26. Combined, this analysis suggests that for every dependant restricted, 0.27 and 0.34 main applicants could be deterred from coming on the Skilled Worker and Health and Care routes respectively. Table E.5 below sets out the additional volume of restricted dependants and deterred main applicants as a result of this policy. These volumes should be considered in addition to those in Table E4.

Table E5. Additional change in visas issued on Skilled Worker visa routes as a result of the RQF 3 to 5 dependants restriction, by previous location (In and Out of Country) and financial year. Central scenario. Main applicants and dependants.

Out of Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -1,000 | -2,000 | -2,000 | -2,000 |

| Dependant | -4,000 | -7,000 | -6,000 | -6,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | -200 | -300 | - | - |

| Dependant | -1,000 | -1,000 | -300 | -300 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

In Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -1,000 | -1,000 | -1,000 | -1,000 |

| Dependant | -3,000 | -4,000 | -4,000 | -4,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | -500 | -1,000 | -100 | -100 |

| Dependant | -1,000 | -2,000 | -200 | -200 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

Note: estimates in 2028/29 are flatlined over the remainder of the appraisal period, so for brevity the table presents annual application estimates up until this year. *The policy is assumed to be implemented from August 2025, and so will only affect seven months of 2025/26. “–“ denotes fewer than 100.

Raising the salary threshold requirements for Skilled Worker routes

27. Finally, the estimated impact of the increase in salary threshold is assessed. To allow for the impacts in this IA to be considered together, this impact is considered on a baseline where the policy impacts in Tables E4 and E5 have already been removed from the baseline in Table E2. This policy therefore only affects the sub-set of remaining RQF 6+ (or those on the TSL, or ISL until December 2026) occupations who are paid below the new minimum salary threshold.

28. As with previous updates of underlying salary data,[footnote 22] salary thresholds are updated using the methodology previously outlined by the MAC.[footnote 23] Using ASHE 2024 data, the general salary threshold for the Skilled worker route would increase seven per cent from £38,700 to £41,700 and seven per cent for the Health and Care route, from £29,000 to £31,300. The going rates for each occupation, as well as the implied salary floor would also increase in line with the ASHE 2024 data and will be published alongside the Immigration Rules. Unlike the increase to the skill threshold, these changes will also apply to those already on the routes, extending their visas.

29. Approximately 16 per cent of the remaining Skilled Worker and 21 per cent of the remaining Health and Care visas issued across both In and Out of country were estimated to be paid a salary below the revised thresholds up until December 2026 (with exemption for ISL roles), and 12 per cent and 19 per cent respectively thereafter (with ISL roles no longer exempt from the policies).

30. The impact of raising the salary thresholds in considered using a methodology consistent with that used in the 2024 Spring Immigration Rules.[footnote 24] This methodology is set out in detail in the 2024 IA but in summary, the total change in the cost of employment (salary costs and non-salary costs such as National Insurance Contributions and Employer Pension Contributions) required to meet new thresholds is estimated, and then applied to published research into the price elasticity of labour demand to estimate a change in demand for labour on the relevant visa routes.[footnote 25]

31. The impacts of the policy package can therefore be separated out into:

- a. The reduction in volumes of migrant workers coming to the UK as a result of the increase in salaries,

- b. The remaining flow of migrant workers who will receive salary increases.

32. As the reductions in volumes are relatively small as compared to the other measures, impacts are grouped in Table E6 below by route and are combined for In and Out of Country. The remaining volumes of Main Applicants set out in the same table are expected to receive a salary increase up to the new minimum.

Table E6. Estimated reduction in annual applications as a result of the increase in salary thresholds, by cohort and financial year. Central scenario. Main applicants and dependants.

Reduction in Inflows

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -1,100 | -1,600 | -1,600 | -1,600 |

| Dependant | -500 | -700 | -700 | -700 | |

| Health & Care | Main | -1,200 | -1,600 | -1,000 | -1,000 |

| Dependant | -700 | -900 | -600 | -600 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Volumes assumed to raise salaries to meet higher threshold

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | 23,000 | 33,000 | 32,000 | 31,000 |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Health & Care | Main | 26,000 | 35,000 | 19,000 | 18,000 |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

Note: estimates in 2028/29 are flatlined over the remainder of the appraisal period, so for brevity the table presents annual application estimates up until this year.

*Care and Senior Care Worker volumes have been removed from the Skilled Worker – Health and Care volumes.

33. The increase in salary thresholds will also affect those on the Global Business Mobility route, where salaries are higher and less clustered around the minimum, and the Scale Up route, where overall volumes are low. As a result, it is the impact of the increase in the salary thresholds on these routes is likely to be small, and therefore no further analysis has been undertaken in this IA.

Overall combined impact on volumes

34. Tables E4, E5 and E6 represent the impact of the policy proposals against the baseline in Table E2. A summary table, E7 below, combines these individual impacts together to represent the overall impact of the policies in this IA. Together, from 2028/29 onwards this represents a reduction of 27,000 inflows annually, and a reduction of around 33,000 in country switchers annually.

Table E7. Total change in visas issued on Skilled Worker visa routes as a result of all policy proposals combined, by previous location (In and Out of Country) and financial year. Central scenario. Main applicants and dependants.

Out of Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -7,000 | -10,000 | -10,000 | -10,000 |

| Dependant | -6,000 | -8,000 | -9,000 | -8,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | -200 | -300 | -400 | -300 |

| Dependant | -1,000 | -2,000 | -2,000 | -2,000 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | -5,000 | -7,000 | -7,000 | -7,000 |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

In Country

| Cohort | Main Applicant / Dependant | 2025/26* | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 Onwards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -7,000 | -11,000 | -11,000 | -11,000 |

| Dependant | -2,000 | -4,000 | -4,000 | -4,000 | |

| Health & Care | Main | -2,000 | -3,000 | -4,000 | -4,000 |

| Dependant | -1,000 | -1,000 | -2,000 | -2,000 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | 3,000 | 5,000 | 7,000 | -12,000** |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

Note: estimates in 2028/29 are flatlined over the remainder of the appraisal period, so for brevity the table presents annual application estimates up until this year. ** As the policy on in-country care workers also commences part-way through 2028/29, this is only a part-year figure. The full annual figure for 2029/30 and beyond is 21,000.

Care and Senior Care Worker volumes have been removed from the Health & Care volumes. Out of country estimates of volumes affected do not match the illustrative estimates set out in the Technical Annex to the white paper this reflects more recent data and grant rates, and a wider set of exempt occupations modelled.

35. To assess the impact on the stock of people who are no longer in the country, as well as the impact on net migration, further analysis needs to be undertaken to estimate what the outflow profile would have been of those who are no longer able to come.

36. Table E.8 below uses internal analysis of Home Office Migrant Journey data to estimate the outflow profile of those who have come on the Skilled Worker route based on 2014-2019 arrivals. As the Health and Care route, and access for Care Workers specifically have been open for fewer than five years, the outflow profile of Skilled Workers is used for all routes in this IA. This is a limitation and may over or underestimate the rate at which those on the Health and Care route may choose to remain in the UK longer term.

Table E8. Outflow profile of Skilled Worker visas based on 2014- 2019 arrivals, Main applicants and dependants.

| Months | 0 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | 72 | 84 | 96 | 108 | 120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker Leave Rate | 0% | 0% | 5.7% | 8.7% | 3.4% | 7.3% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

Source: Internal analysis of Home Office Migrant Journey

Note: Those who remain in the UK beyond 120 months are assumed to remain indefinitely

37. Tables E.9 and E.10 use this outflow profile to set out the resultant change in the stock of migrants who are no longer in the UK and the net migration impact of these policies respectively. Estimates of the high and low stock and net migration impacts are set out in Annex A.

38. Table E.9 reflects the cumulative number of people who are assumed not to be present in the UK by year. For example, in year one, this impact is equivalent to the flow of people who are restricted from coming. By year 5, this represents the sum of all of the people who were restricted from coming but removing any who would have otherwise already left the UK had they been able to come. This is used to estimate the fiscal impact of people not working and consuming public services in the UK

Table E9. Stock of people not in the UK as a result of the policy restrictions, financial year, thousands, main applicants and dependants.

| Cohort | Main / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 | 2029/30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -14 | -35 | -55 | -73 | -91 |

| Dependant | -8 | -20 | -31 | -42 | -52 | |

| Health and Care | Main | -2 | -5 | -10 | -13 | -16 |

| Dependant | -2 | -5 | -8 | -11 | -14 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | -2 | -4 | -4 | -22 | -50 |

| Dependant | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis. Stock not set out for the final part-year of the appraisal period as not comparable to previous years, but is included in NPSV calculations

39. Table E.10 reflects the net flow of people into and out of the UK. Unlike E.9 only the restricted inflows in that year are considered, and any people who would otherwise have left from any previous year are removed. For example, in year one, this impact is also equivalent to the flow of people who are restricted from coming. However, by year 5 this represents only the flow of people in year 5 restricted from coming but removing any people from previous years who choose to leave in year 5 (for example those restricted from coming in year 3 but would otherwise have left two years later). This is used to estimate the net migration impact.

Table E10. Net Migration impact as a result of the policy restrictions, financial year, thousands, main applicants and dependants. Note this table is in three parts, with total impacts in the final part.

Table E10.1 - Impact of out-of-country migrants

Change in inflows onto skilled worker routes

| Out of Country | Main / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 | 2029/30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -7 | -10 | -10 | -10 | -10 |

| Dependant | -6 | -8 | -9 | -8 | -8 | |

| Health and Care | Main | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dependant | -1 | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | -5 | -7 | -7 | -7 | -7 |

| Total | -19 | -27 | -28 | -27 | -27 |

Change in outflows from those who would have been on skilled worker routes

| Out of Country | Main / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 | 2029/30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -3 |

| Dependant | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | -3 | |

| Health and Care | Main | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dependant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | -2 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | -1 | -4 | -9 | |

| Net migration | ||||||

| Total | -19 | -27 | -27 | -23 | -19 |

Table E10.2 - Impact on in-country migrants

Change in inflows onto skilled worker routes

| In Country | Main / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 | 2029/30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -7 | -11 | -11 | -11 | -11 |

| Dependant | -2 | -4 | -4 | -4 | -4 | |

| Health and Care | Main | -2 | -3 | -4 | -4 | -3 |

| Dependant | -1 | -1 | -2 | -2 | -2 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | 3 | 5 | 7 | -12 | -21 |

| Total | -9 | -14 | -14 | -33 | -41 |

Change in outflows from those who would have been on skilled worker routes

| In Country | Main / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 | 2029/30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -4 |

| Dependant | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | -1 | |

| Health and Care | Main | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 |

| Dependant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | -4 | |

| Net migration | ||||||

| Total | -9 | -14 | -14 | -31 | -37 |

Table E10.3 - Total combined impact (out-of-country and in-country)

Net migration impact

| Total | Main / Dependant | 2025/26 | 2026/27 | 2027/28 | 2028/29 | 2029/30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skilled Worker | Main | -14 | -21 | -20 | -18 | -14 |

| Dependant | -8 | -12 | -13 | -10 | -8 | |

| Health and Care | Main | -2 | -3 | -4 | -4 | -2 |

| Dependant | -2 | -3 | -4 | -4 | -3 | |

| Care and Senior Care Workers | Main | -2 | -2 | 0 | -19 | -27 |

| Total | -27 | -40 | -40 | -53 | -54 |

Source: Internal Home Office analysis

*2035/36 reports on a partial year, covering 1st April 2035 to 22nd July 2035

40. Table E.10.3 shows that the overall net migration impact of this package of policies is around -40,000 in 2027/28, rising to -54,000 in 2029/30 after restrictions on in-country care workers are introduced during the 2028/29 appraisal year. The equivalent net migration impact tables for the high and low scenarios are set out in Annex A.

Place-Based Analysis

41. The policies appraised in this Impact Assessment (IA) have no specific geographical dimension however the following analysis considers the potential place-based impacts of the proposals.

42. Home Office administrative data provides information on the region of the sponsor of those on the Skilled Worker route. Whilst this may not align to the migrant’s location in all cases, for example if a sponsor may operate multiple work locations around the UK, it provides an insight into the potential geographical implications of the policies.

43. Looking at this data for the period October 2024 to March 2025, the proportion of migrant workers assigned to sponsors in each region is multiplied by the estimated reduction in annual out of country applications in the central scenario in Table E7 to provide an estimate of the annual reduction in migrant workers by region. This is compared to ONS data on the stock of employees by region in January to March 2025 to discern the extent to which each UK nation and region may be impacted by the policies.

44. Table E11 sets out this place-based analysis. This place-based analysis suggests that for the Skilled Worker route, around half of all workers were employed by an employer based in London and the South East, with under 15 per cent based outside of England. While those on the Health and Care route were more evenly distributed across England, with concentrations in the North West and the West Midlands, there was a similar under 15 per cent based outside of England.

45. When considering the impact of the policies as a share of the stock of employees in each region, the most significantly affected area was London at 0.11 per cent with the remaining nations and regions of the UK at a similar level of between 0.02 per cent and 0.07 per cent. Even when considering the combined impact of the policy proposals on inflows over the 5-year appraisal period, this would not represent 1 per cent of total employment in London, and below this level across the rest of the country.