SPI-B: Insights on celebrations and observances during COVID-19, 29 October 2020

Updated 26 October 2021

Background

Restrictions put in place to manage infection rates during the COVID-19 pandemic have impacted a number of celebrations and observances including St Patrick’s Day, Isra and Mi’raj, Mothering Sunday, Passover, Good Friday, Easter, Eid ul Adha, Rosh Hashana, and more. Some celebrations and observances were the focus of targeted guidance in advance[footnote 1], while others such as Eid ul Adha, were disrupted at short notice due to rising local infection levels[footnote 2]. COVID-19 will continue to be a challenge for many months. In light of this, it is important to rethink the nature of celebration and observance during the pandemic to protect and enable the elements of secular and religious celebrations and observances that the UK population holds dear.

Celebrations and observances can be cultural, religious, or a combination of both. Family celebrations and observances entail personalised, repeated, highly stylized, structured behaviours that are symbolic in nature and essential to the reproduction of family ties[footnote 3],[footnote 4],[footnote 5]. Celebrations and observances enable families to create and share joint legacies that draw upon generational dynamics to create personal family histories. Traditions can be very difficult to change because they are created by, and belong to each family, and are passed on from childhood[footnote 6]. The behaviours that combine to form celebrations and observances hold emotional value and significance. Discussions about family traditions, rituals, and bonds, recognises the “…human experience of kinship and within reason, a lot of this discussion is relevant to inform other festivals and celebrations (both religious and non-religious)”[footnote 7].

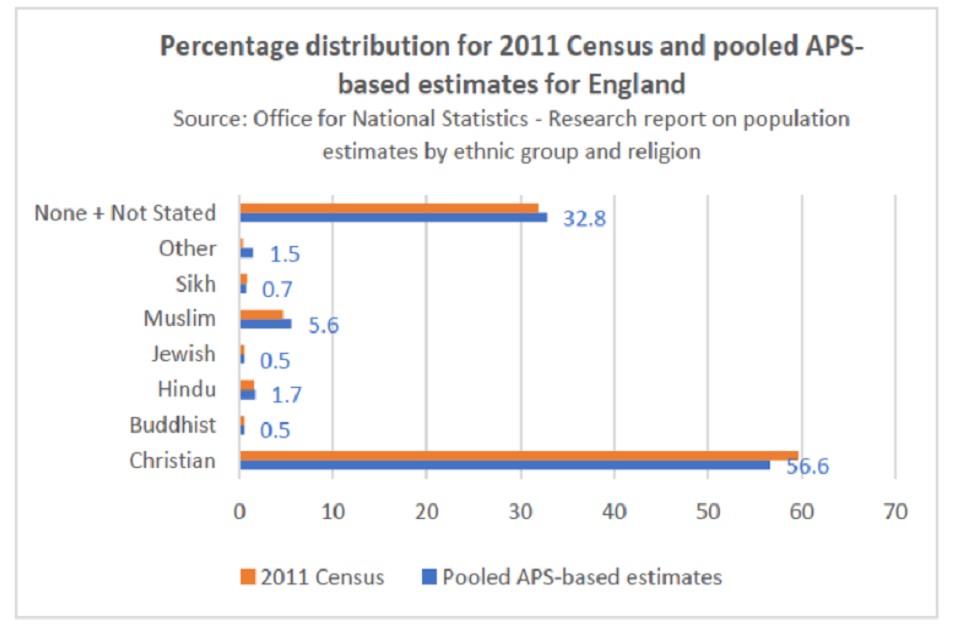

Population estimates provide a proxy indicator of the diversity of religious celebrations and observances in the UK. Figure 1 provides the findings of the Office for National Statistics (ONS) research report on population estimates by ethnic group and religion. This picture is complicated further by variations in traditions and rituals and the values assigned to these practices within and between religious groups. Labels can lead to inaccurate assumptions about practices and preferences, too. Among those who identify as Christian, a 2017 survey of 8,150 Great British adults found that only 28% identify as “an active Christian who follows Jesus”[footnote 8]. Beyond this, over 30% of the population have identified themselves as non-religious or opted not to share their religious affiliation if they have one.

Irrespective of their belief system, a significant proportion of the UK population stands to be impacted by COVID-19 restrictions on their secular and religious celebrations and observances. People are already changing their holiday, celebration, and observance plans in response to the risk of COVID-19 and restrictions put in place to manage this risk. This work can assist planners and members of the public in their decision-making and help them navigate the social, spiritual, practical, and moral dilemmas that arise when altering life-long traditions and rituals. The pragmatic responses of faith and non-faith groups to the challenges of funeral rituals during the first wave suggests that there is a greater deal of adaptability than might at first be expected. This is because for both secular and non-secular celebrations it is the essentials of a ritual that are most valued rather than outwards forms [footnote 9], [footnote 10], [footnote 11], [footnote 12], [footnote 13].

Figure 1: Distribution of religions at the national level for England (2019 versus 2011) [footnote 14]

Distribution of religions at the national level for England 2019 versus 2011.

This report will provide insight into the behavioural risks of forthcoming celebrations and observances by:

i) Identifying the general behaviours related to UK celebrations and observances;

ii) Considering possible alternative behaviours to enable UK celebrations and observances;

iii) Reflecting upon enablers and barriers to these alternatives;

iv) Recommending risk communication interventions to support and reinforce the need for alternative behaviours;

v) Applying the guidance contained in this report to a Christmas case-study

Christmas has been chosen as a case study for a number of reasons. Whether you adopt a secular or religious approach, Christmas acts as a major kinship event - ‘a time to share food and be together with family (Mason and Muir, 2013), and a time to stop working, travel home and decorate cities and houses (Kasser and Sheldon, 2002)’ [footnote 15]. The holiday, religious, kinship activities that take place during the Christmas season result in wide-scale behaviour change across the UK. Polling evidence indicates that people are already making alterations to their Christmas plans and behaviours [footnote 16] and forming views about freedoms and restrictions during the Christmas holidays[footnote 17]. Identifying behavioural and communication principles relevant to this time of year will assist planners in identifying methods and opportunities to co-create a suite of measures that protect and enable existing traditions whilst defining new practices that recognise and celebrate pre-existing cultural norms. The colder months also have the potential to present increased risks of transmission, as gatherings move indoors and ventilation is decreased in homes and public buildings. This, combined with anticipated seasonal pressures on the health system through the winter flu season, suggests that there is a need for particular consideration of the impact of celebrations over the next few months.

General behaviours related to celebrations and observances

Many behaviours will be similar for multiple celebrations and observances, while others will be associated with specific events only[footnote 18]. For example, we are likely to see:

-

Increased travel, including more frequent local trips and journeys over greater distances: Many of the celebration and observance-related activities, such as shopping for food and gifts, will take place in the days and weeks prior to a significant event[footnote 19]. For example, while Diwali celebrations span several weeks, days 3 to 5 of the celebration involve visiting with friends and family to share company, food, and prayers. Some celebrations and observances require family members to travel great distances in private and public transport to be together. Family gatherings help define Passover and Christmas celebrations and observances and observances, too. Levels of travel increase closer to the events, themselves. This was illustrated by the 4.3 billion miles travelled (average 449 miles each) by members of the UK public during the 2019 Christmas holiday. The majority of this travel fell on the 18, 19, and 20 of December[footnote 20]. Holiday travel presents unique challenges during COVID-19. In addition to the increased risk of transmitting the virus, travel may entail passage between or through areas with different levels of COVID-19 restrictions when many others are trying to make similar journeys over a constrained period of time.

-

Gathering in homes, outdoors, and at celebration and observance-specific events: Members of the public attend religious services, holiday performances, and other events during celebration and observance periods in non-COVID-19 times. Many of these interactions are with family and friends, while others involve engagement with a larger community (for example bonfires and fireworks, seasonal performances). Some celebration and observance-specific events take place across a number of days or weeks in the run-up to the significant event, itself (for example school plays, turning on communal light displays). For example, Diwali celebrations in the City of Leicester last for over two weeks in non-COVID-19 times. Fairs, local craft displays, the switching on of lights, traditional dance and music programmes, and fireworks mark this occasion.

-

Other celebration and observance events involve staying with friends and family overnight, or across a number of days. This is a concern as overnight or extended visits increase the potential for overcrowding within homes. A previous SPI-B and EMG report argued that overcrowding is known to be a driver of infection through increased risk of droplet and aerosol transmission compounded by shared facilities, inadequate ventilation, extended duration and proximity to others (for example room sharing)[footnote 21],[footnote 22]. Celebrations and observances also create the potential for increased interaction with at risk groups and mixing between generations. Previous SPI-B and EMG work identified a “High level of mortality risk within a home containing vulnerable household members” including those associated with intimate social relationships (families), among other factors[footnote 23],[footnote 24]. Additional interactions occur when sharing food and drink, exchanging gifts, hugging, singing, or praying with family, friends, and neighbours.

-

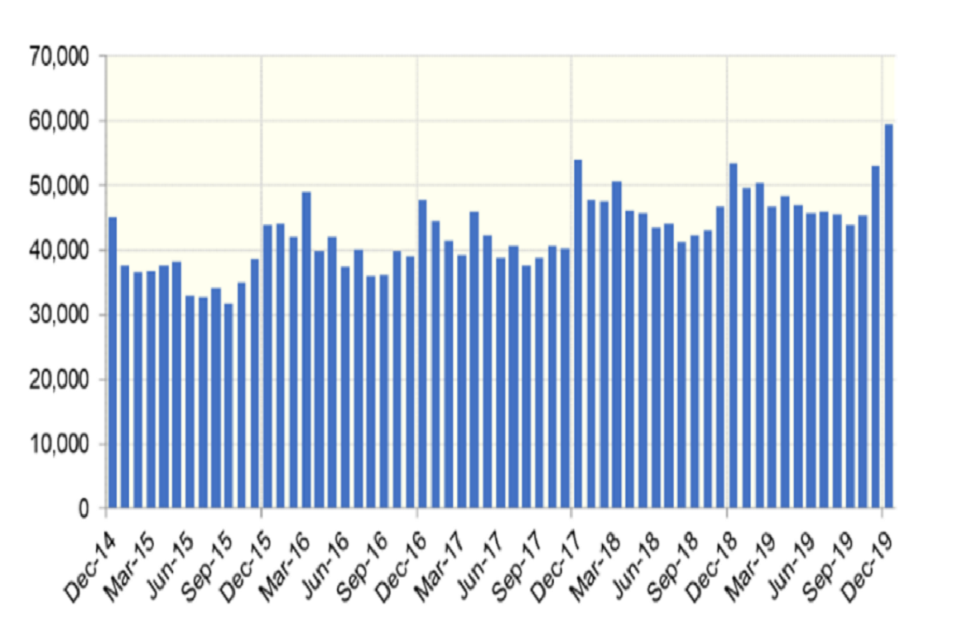

Increased engagement with health services: Christmas and the New Year have the potential to put pressure on the NHS. The clearest indicator of additional stress on the NHS can be seen in the weekly totals of ‘calls offered’ peak at Christmas week, and daily totals show additional non-weekend peaks on Christmas or New Year for the NHS 111 service (Figure 2). However, concerns about additional pressure on Ambulance and A&E departments[footnote 25] over the Christmas holidays are more difficult to support with the data[footnote 26],[footnote 27].

Figure 2: Calls offered per day to NHS 111, England, 2014 to 2019[footnote 28]

Calls offered per day to NHS 111, England, 2014 to 2019.

-

Charitable sector data provides stronger evidence of a significant increase in demands for mental health services over the Christmas holidays. A recent YouGov survey[footnote 29] of 2,193 British adults found that over two in five Brits report feelings of stress, and about one in four reported struggling with anxiety or depression during the Christmas season. Several respondents reported that Christmas has a fairly (19%) or very (7%) negative impact on their mental health. The Samaritans report that they responded to over 4.3 million requests for help[footnote 30] in 2018 and 2019[footnote 31], including 300,000 (6.9%) of these during the Christmas period between 1 December 2018 to 1 January 2019[footnote 32]. This may be only the tip of the iceberg with a MIND report finding that a third of people (36%) are too embarrassed to admit that they are lonely at Christmas[footnote 33].

-

Singing: Carol singing, choirs, live music, and live theatre performances form important traditions for some celebrations and observances. The process of singing together is essential to the creation of a sense of collectivity and group identity for many people[footnote 34],[footnote 35]. There is evidence that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can be transmitted in a performance setting if there are infectious individuals present amongst the audience or performers[footnote 36]. Less is known about singing in informal environments, or in outdoor settings. Additional work is required to understand the value of these activities and to identify appropriate alternative behaviours capable of addressing the risk of infection from aerosols.[footnote 37]

-

Sharing food and drink is highly likely to form an important, value-laden part of many celebrations and observances. To share food is to embody community and family psychosocial connections. Such exchanges do not just reflect existing ties but make a sense of belonging and of being at home[footnote 38],[footnote 39]. Work is needed to understand the risks of sharing food and drink during COVID-19. Without this, communication and interventions should address the issues of proximity and duration of visits when food and drink is shared.

What are the behaviours of interest that we are concerned about?

The simple response is that behaviours that increase interactions between households also increase the risk of infection. Environmental conditions (such as ventilation) and behaviours (such as social distancing, good hand hygiene) can help individuals, groups, communities, and organisations decrease the risk of infection, but all interactions beyond the household level will hold some level of risk.

If we accept that interactions will occur, socially distanced outdoor gatherings are less risky than socially distanced indoor gatherings due to ventilation and other environmental factors (such as the ability to maintain distance, UV lighting). Behaviours of concern are behaviours that increase interaction between households and individuals, occur indoors, occur for a longer period of time, and make it difficult to maintain social distancing.

What this means in practice for celebrations and observances will vary, with some combinations of behaviours being riskier than others. For example, sharing food and drink with members of another household who are staying overnight is likely to be riskier than attending a local bonfire or fireworks event with another household. Indoor interactions during colder months are likely to be riskier than during warmer months due to decreased household or public indoor ventilation when doors and windows are closed to the elements. Similarly, indoor and outdoor UV light is likely to be reduced during the winter months [footnote 40].

Interventions based on assumptions about the value assigned to different celebratory and observance practices are highly likely to be less effective than those based on collaboration and co-design with communities and religious groups. The risk of potential infection associated with each behaviour or combination of behaviours must also be understood in terms of the value that individuals and groups place upon these aspects of celebration.

Further Work

Identifying the behaviours that are of concern in their own right, or in combination will require a multi-disciplinary approach. A collaborative effort will provide greater insight and certainty into the questions:

1) What are the key behavioural risks of the forthcoming celebration season?

2) What are the levels of risk associated with alternative behaviours?

3) How much can alternative behaviours decrease the risk of infection?

Additional qualitative and quantitative work is needed to identify the value of celebratory behaviours to members of the public, community, and religious groups. Some behaviours have religious significance, others will reinforce cultural values, and others will be important for maintaining family connections and mental health. This work could provide insight into the value and symbolism associated with each behaviour, combination of behaviours, and events.

For example, a greater understanding of the risk of infection associated with traditional celebratory and observance behaviours, combinations of behaviours (for example visiting and sharing food), and the level of risk associated with potential substitution behaviours will aid the development of evidence-based, realistic scenarios for restrictions and advice for celebrations and observances of all types.

The ease or challenge of changing or maintaining these well-defined behaviours during celebrations and observances can be better assessed by understanding the value that they bring to the essence of the celebrations and observances. Some of this information can be undertaken through a Task and Finish group approach.

Modelling is needed to develop insight about the risky or less risky behaviours traditionally associated with these celebrations and observances. The Environmental Modelling Group can provide insight into the risk of infection from the settings in which events are likely to take place. SPI-B can draw upon their expertise in individual and group behaviour, household transmission, collective behaviours, travel to and from events, alternative behaviours, and communication to provide a more detailed, scenario-based analysis.

As a first step, however, we are able to provide insight into communication challenges and enablers for possible alternative behaviours and messaging about celebrations and observances during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.

Alternative behaviours

Alternative behaviours are needed to decrease the risk of infection throughout periods of celebration during COVID-19. Modelling of contact scenarios for Passover and Easter holidays suggest that even very short, temporary increases in contact rates lead to permanent increases in the infection rate and a significant increase in hospital admissions[footnote 41]. Vierlboeck, Nilchiani and Edwards (2020) argued that a temporary, sustained increase of contact rate for just three consecutive days may result in an increase of infection rate up to 40%, with the potential to double fatality in the long term[footnote 42].

Families and groups considering temporary exceptions to public health guidance around social distancing, hand washing, and reduced contact over the holidays must be made aware of the risk of infection. This messaging should be accompanied by information about the risk of traditional behaviours, opportunities to create and engage in alternative forms of celebration, and the effectiveness of decreasing infection risks by changing behaviour.

COVID-19 restrictions on celebrations and observances do not have to create an all or nothing approach. It is important to recognise that some celebration and observance behaviours can still take place during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the first two days of Diwali celebrations entail cleaning the house, shopping, buying new clothes, decorating the house with lights, and purchasing gifts. Many of the shopping activities can move online, and families can consider creating their own fireworks displays, making traditional gifts, listening to traditional music, and watching traditional dance at home. Many Hindu celebrations for example use virtual mediums already[footnote 43],[footnote 44]. They may also engage in more intimate household or family group prayers[footnote 45].

Alternative behaviours can take place alongside traditional behaviours. Alternative celebrations and observances have already been encouraged and used during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, a variety of adaptations to Eid celebrations and observances were seen around the world. Some were socially distanced, others involved outdoor prayers, shorter ceremonies, cancellations and adaptations to the ritual distribution of meat to communities, and more[footnote 46],[footnote 47]. Open house traditions involving feasts were cancelled. Adaptive behaviours developed to enable celebration in spite of the restrictions included: sending presents online, scheduling family meals at the same time in order to sit down and eat or enjoy the meal during a phone or video call, wearing traditional clothing, and finding ways to make the atmosphere in the home feel more celebratory[footnote 48].

Looking ahead, Diwali and Christmas alternatives may include connecting with friends and family via video calls or in a socially distanced manner, sending gifts through the post rather than delivering them in person, and creating and sharing hampers of seasonal food that do not require entry into the home to exchange. New Zealand is planning to spread their usual two-day Diwali celebration across three weeks to better enable small community events and avoid mass gatherings[footnote 49]. Similarly, Passover activities, such as family meals and children searching the home for leaven may need to be shared through video calls. Video calls can also enable Seder plate meals, story-telling, and singing. Christmas dinner, stories, and opening of gifts may also be separate, but shared experiences through the use of technology[footnote 50].

A recent SPI-B report identifying positive strategies for sustaining adherence[footnote 51] to infection control behaviours argues that it is important to promote and support positive alternatives whenever activities that are valued are restricted. This will help to reduce the negative emotions and undesirable replacement behaviours that some experience and develop when people are forced to stop or suppress a behaviour that they value. For example, actively proposing and supporting less risky behaviours when a social interaction needs to be avoided could mean reimagining and enabling the activity to take place outdoors but socially distanced (for example fireworks or doorstep celebration to replace indoor celebrations), online, or at a later date (such as when the family can gather safely)[footnote 52].

In order to identify and enable alternative celebratory and observance behaviour we must:

-

Identify alternative behaviours through co-design and consultation. SPI-B defined co-production as the processes and activities by which specific outputs, whether policy, guidance or tools, are created between those traditionally viewed as the ‘decision-makers’ and those groups traditionally viewed as ‘subjected’ to those outputs[footnote 53],[footnote 54]. Whether it is achieved over the course of a few hours, weeks, or months, co-production can generate more effective approaches, solutions, and outcomes. Co-production that is embedded at a local level, fit for purpose, supportive of procedural justice, is equity-generating, and evaluated for effectiveness will go a long way to preventing the development of interventions and substitution behaviours that lack relevance or public acceptability[footnote 55].

-

Such co-production does not necessarily take a long period of time, but could be carried out in a swift fashion if the right partners are identified from the start. It would be important to find local experts who are specialists in celebrations both secular and religious. Local experts are people who sit across several social nodes and networks, who therefore have more in-depth knowledge of a range of positions within various regional, faith and non-faith communities. For festivities and observances it would be helpful to identify first religious experts, but also secular ones. Secular experts could include Humanists UK, local council community officers, but also celebration ‘influencers’ such as well-known chefs or lifestyle journalists, who are used to altering the ways people interact. Suggestions for novel ways to celebrate could also be sought from the general public in a social listening exercise on virtual platforms fronted by key public figures[footnote 56].

-

Behaviour is influenced by habits, and habits can be difficult to break. Behaviour can also be influenced by the people around us or the social groups we identify with. As such, social habits such as hugging or shaking hands can be replaced by lower risk alternative habits grounded in accepted values and norms. For example, a recent SPI-B report on sustaining adherence to infection control behaviours argued, “It is helpful to explain that we are not showing less care for others by avoiding hugging, but rather that we express our care in a time of pandemic by not endangering the health of loved ones or fellow group members by hugging them”[footnote 57].

-

The most powerful alternatives will be grounded in traditional forms of celebration and observance. Alternative behaviours should not be framed as changing norms. Attempts to identify and ‘assign’ new behaviours may be viewed as interfering with ‘our’ culture and identity. Rather, alternative behaviours must draw upon and refer to existing norms and create opportunities for discussing what they mean in changed times. For example, what does the core tenet of ‘Goodwill to all people’ mean? Is this meaning the same or different during a period of pandemic? Can alternative behaviours enable individuals and groups to translate ‘Goodwill to all people’ into behaviours that help, protect, and nurture others? The value assigned to different aspects of and behaviours associated with celebrations and observances, as well as the form, acceptability, and value of traditional alternative behaviours must be identified through the process of co-design.

-

Alternative behaviours and the values assigned to these behaviours cannot be assumed. They must be identified and created in partnership with communities and religious organisations to provide attractive, less risky alternatives to celebrations and observances during the COVID-19 pandemic[footnote 58],[footnote 59]. Identifying or creating behaviours that are consonant with group norms is key[footnote 60].

-

Where possible, identify ways to move celebrations and observances outside. The Environmental and Modelling Group (EMG) argued that, “Aerosol transmission risk is considered to be very low outdoors due to high dilution of virus carrying aerosols and UV inactivation of the virus”[footnote 61]. Promoting outdoor activities provides an important opportunity for celebrations and observances to take place, given the lower risk of transmission during socially distanced outdoor activities. Permitting and supporting outdoor activities will be particularly important for those who are unable or unwilling to engage with online alternatives. For example, New Year’s Eve fireworks or doorstep celebrations (similar to the Thursday clap during lockdown) could also be encouraged as a substitute for indoor parties. It may be possible to identify opportunities for creating excitement around decorating buildings and homes in a community, switching on lights, supporting small businesses with hot drinks stalls placed along a celebration trail, or creating socially distanced versions of traditional activities. For example, ‘The Big Neighbourhood Pumpkin Trail’ is a local or online initiative enabling neighbourhoods to decorate their houses and windows with pumpkins for Halloween. Children and families can walk around local areas finding and counting pumpkins and receive treats for the number of pumpkins spotted, rather than going house to house during COVID-19[footnote 62]. Adaptations including outdoor prayer during Eid have already taken place. If well-managed, these outdoor substitutions could be an opportunity to demonstrate it is possible to do things differently but achieve a similar level of excitement to more traditional activities.

-

Identify safe ways to include family and friends in indoor celebrations and observances. The risk of transmission indoors must be communicated clearly. Explanations can be adapted for a holiday context. The EMG also argued, “Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is most strongly associated with close and prolonged contact in indoor environments. The highest risks of transmission are in crowded spaces over extended periods (high confidence)[footnote 63]. The importance of physical distancing in decreasing the likelihood of infection should be a focus, with additional mitigation measures (for example face coverings, minimising duration of exposure) required in situations where 2 metre face-to-face distancing is not possible[footnote 64].

-

Environmental changes within the home can enable and encourage people to engage in low risk behaviours if individuals from outside of the household enter the home. Suggestions from SPI-B report “Positive strategies for sustaining health adherence to infection control and behaviours” can translate into the home environment during celebrations and observances and beyond. “For example, providing sanitising facilities at the entrance to their home, organising seating in the home to support social distancing from visitors, or putting masks in all their coats and bags so there will always be one when they go out”[footnote 65].

Enabling alternative celebrations and observances

Several enablers to support alternative behaviours or less risky approaches to celebration exist. Some of these involve practical steps to manage and open up access, while others are value-based. In particular, it may be valuable to draw on the sense of community identity that has developed during the pandemic and the growth of street and neighbourhood level mutual aid groups[footnote 66]. It will also be important to draw on other neighbourhood organisations (for example churches and other faith organisations) and expertise (such as local historians) in order to plan, organise and promote alternative events that reinvent and reinvigorate local traditions[footnote 67].

Enabling outdoor events:

Guidance from previous reports on mass gatherings and large events are relevant when considering how to enable celebrations and observances to take place in an altered context[footnote 68],[footnote 69]. If larger events such as Christmas markets, or more formal lights festivals are to go ahead, organisers can control access to a location (ticket only) in such a way as social distancing and other well-defined behaviours can be maintained. Broadcasting and finding other ways to participate in such events remotely would be examples of alternatives, which could be promoted, for those who couldn’t get tickets but want to participate. Postponement is another option. If some part of the event can take place, be broadcast or otherwise shared widely, the wider national participation could be postponed for a later time for some celebrations and observances[footnote 70].

Smaller, local events can also be time-tabled on a community or neighbourhood level. For example, creating time-tables for Christmas carollers to visit streets or neighbourhoods instead of going house-to-house, or identifying and communicating a time for everyone to come outside to ring bells (for example The Christmas Eve Jingle) in order to ring in the New Year in a Covid-safe way may create a shared experience and sense of collective celebration. The Christmas Eve Jingle echoes the Clap for Carers activities of March and April that increased street-based collectivity and enabled people to feel involved but be relatively safe. Outdoor activities are already being adapted and arranged by communities and shared on social media. More formal alternatives have also been organised, with mosque leaders organising outdoor prayers during Eid.

Challenges, such as foul weather, lack of private and social outdoor spaces, and variations in local tier restrictions can create inequalities. These must be addressed if alternative outdoor events are going to be attractive, acceptable, and inclusive. This may entail investment in outdoor canopies and tents, licenses for pop-up stalls and performances, and messaging about sensitivity to those in the community who do not want to or cannot take part.

Enabling lower risk home visits:

Research into acceptable and feasible methods of infection control within the home confirms that social distancing from friends and family is not easy, but that acceptable methods of reducing risk can be supported[footnote 71]. Examples include replacing physical contact with distanced greetings (for example hand on heart)[footnote 72]; limiting the number of visitors at one time and the duration of their visit (this allows space to socially distance, limits the time for viral load build-up and provides an opportunity to air and clean the home before another visitor arrives); and restricting visitors to those who have avoided risky contacts for 2 weeks before their visit.

Provide support with ‘how to have conversations’ guides about planning celebrations and observances that deviate from cultural norms. For example, use language that reinforces the goal of protective behaviours (for example modify the way we do this year’s celebration to have many more together), provide concrete examples of how families can stagger visitors, or engage in virtual celebrations and observances that retain the values associated with each tradition. Guidance that enables the new norms in the home during and beyond celebrations and observances is needed.

Challenges such as a lack of private or communal space inside the household, shared bathrooms and sleeping quarters, communal access (for example lifts), and more must be considered when developing guidance for household celebrations and observances.

Enabling communities:

Embrace the processes of co-design and engagement with communities and local actors. On-going community engagement is required as acceptability of alternative celebratory activities or potential barriers may change over time. Having regular engagement, feedback and insight at this level will identify new and emerging challenges that may not have been apparent or existed at earlier stages of community engagement and co-design activities.

Provide financial investment to facilitate substitution behaviours. This could include free Wi-Fi to households to better enable online engagements, but could also include gestures of goodwill such as free hot-drinks when substituting indoor celebrations and observances with outdoor activities. Consider investing in canopies and tents if outdoor celebrations and observances are being encouraged.

Many of these celebrations and observances last for several days. It is very important for community leaders and government officials to role model adherence to guidance as individual’s may be less willing to make this sacrifice if there is a perception that not everyone is adapting activities.

Enabling celebration within pre-established groups:

Consider enabling celebrations within pre-existing groups, such as classroom bubbles, nursing home bubbles, and offices. This may decrease the need to take celebrations out into the community. Households could be advised to form restricted social bubbles with two or more households leading up to and involving the celebratory period. These regular connections with smaller groups of essential people could be less risky than meeting multiple members of multiple households in a single burst. It might be worth revising social bubble rules for festive periods to allow a wider range of permanent connections to other households than under the current Tier 2 and 3 rules. These are at present only for forms of emergency care[footnote 73]. This extension of existing social bubble rules is likely to create a high legitimacy for government interventions as the government will be seen to care about what people most care about during celebrations—their connection to friends and family[footnote 74]. Accompanied by clear public health messaging about how to stay safe when interacting this could be an effective policy.

Barriers to alternative celebrations and observances

Challenges that prevent parts of the community from participating in the alternative celebrations must be addressed. These include, but are not limited to:

The digital divide

The digital divide is already posing challenges for education, combatting isolation and loneliness, and delivery of healthcare. Similarly, a lack of physical or skills-based access to basic digital equipment and access to the Internet could potentially exclude some of the more vulnerable or ‘at-risk’ groups such as older people and some members of minority ethnic groups from taking part in the celebratory alternative behaviours. Where this holds true, there is potential to draw on Community Champions to facilitate alternative celebrations in a community setting (for example to promote outdoor activities) and facilitate skills (for example conversational, planning) to make alternative arrangements.[footnote 75] Community Champions in some areas now have extensive social media and other local communication networks. However, it is also true that the places that are most disadvantaged have the least capacity of volunteers.

Perceived lack of relevance in messaging

For messaging to have any effect, it is necessary that people see it as of relevance to themselves[footnote 76]. There are a number of factors which may undermine the perceived self-relevance of messages on COVID-19 behaviours and therefore undermine their impact. If people believe non-compliance is associated mainly with other groups and with the activities of others. For instance, there is anecdotal evidence from the police that people associate domestic non-compliance with young people and large house parties and hence consider that their own more modest violation of the rules is insignificant.

Another factor is that people think of familiar people and spaces as relatively safe and therefore allow them to relax their guard, for instance by decreasing social distancing[footnote 77],[footnote 78],[footnote 79]. This undermines adherence in domestic and intimate settings. In some instances, the risk of celebrating with more vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, may be perceived as justified if the opportunity is believed to be the final chance to celebrate with them.

Protection of specific celebrations or observances

Celebration and observance amnesties must be approached with caution and, if capable of increasing infection rate should be avoided. Celebration and observation amnesties also have the potential to increase community tension and decrease social cohesion.

In addition to the impact on social cohesion, there is risk of discrediting previous guidance and any future guidance in the event of an amnesty. Guidance that changes overnight may diminish the perception of risk. If guidelines are relaxed for some festivals, some may reason that this can be applied to other celebrations, using the same logic that was applied to the amnesty when associating same level of importance and values on other celebrations. For some, this could include non-religious events such as weddings and anniversaries. This is why it may be better to mitigate through social bubble policies of regular interaction over the festive season for all rather than a one off amnesty for a single continuous period of limitless interaction over 2 or 3 days. These regular interactions permitted within social bubbles over a three week or would benefit all groups in the UK, and disadvantaged and minority groups the most since they are most dependent on these social interactions[footnote 80].

Enforcement

One of the primary challenges of celebrations will be enforcement. Enforcement of celebration behaviours in private homes is almost impossible. Additionally, enforcement of outdoor activities becomes an issue of public assembly - a protected right under the ECHR. The covers all forms of gathering including celebration, religion, protest. There should be a coordinated approach to how to enable assembly, expression and belief under conditions of the pandemic. It will be very difficult to adopt a blanket approach to enforcement as activities that are allowed will vary with increased and decreased rates of infection.

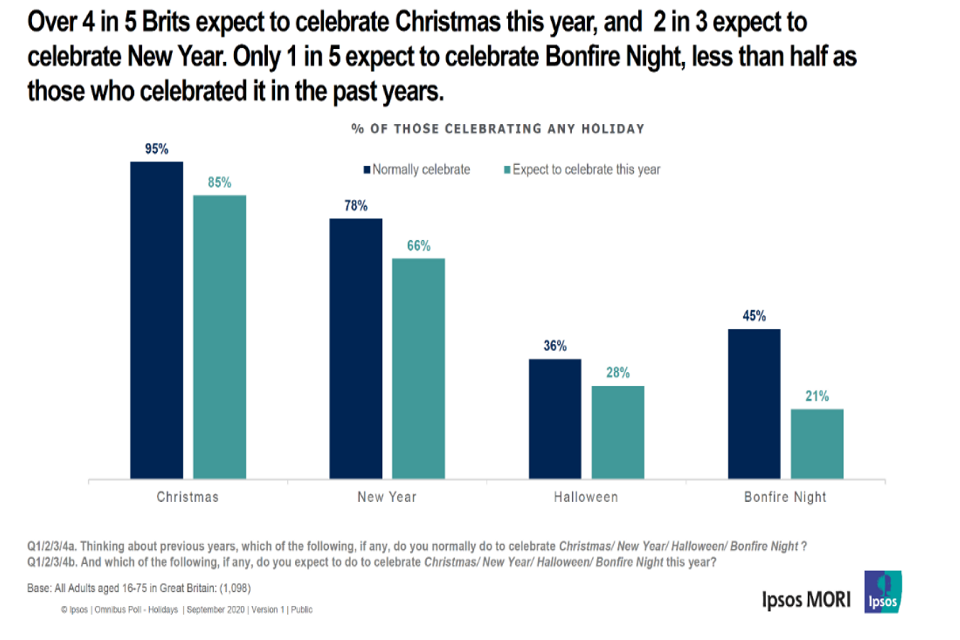

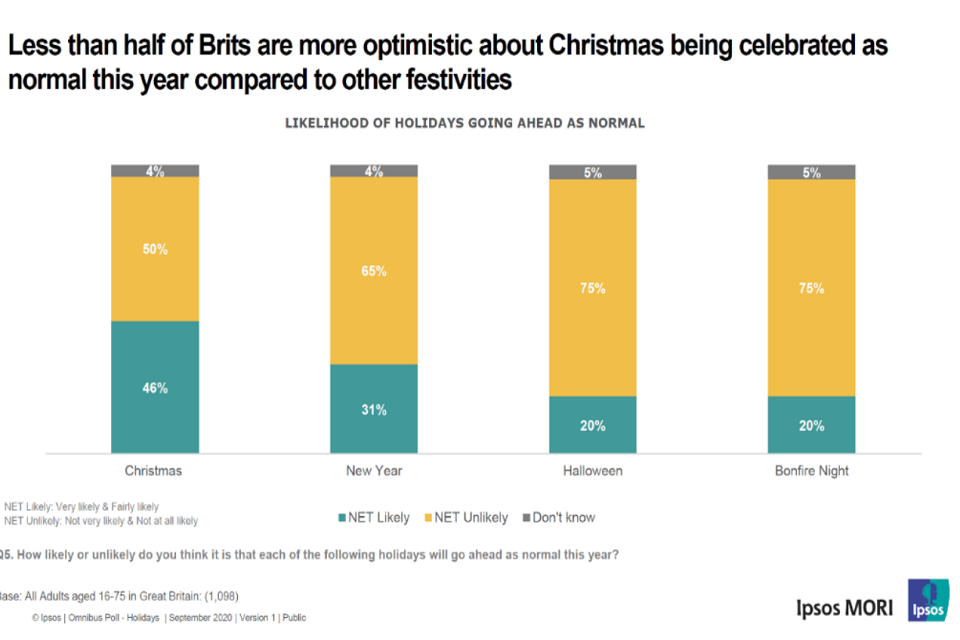

When thinking about enforcement, it is important to recognise that celebrations will vary in magnitude of the risk. For example, Halloween is a different order of magnitude to Christmas and New Year in light of the number of people interested in taking part in each celebration. A recent Ipsos MORI poll into public perceptions of holidays in 2020[footnote 81] highlights variations in intended participation. The risks and restrictions associated with COVID-19 have already decreased the UK public appetite for celebrations (See Figure 3)[footnote 82]. Christmas and New Year still feature strongly in UK public celebratory expectations, with Halloween and Bonfire Night celebrations decreasing further.

Additionally, while 3 in 5 respondents taking part in a MORI survey[footnote 83] reported that they do not intend to celebrate Bonfire Night this year [footnote 84], the combination of darkening nights, availability of fireworks, and a sense of frustration in some cities will pose challenges for police, especially in areas where enforcement of all kinds is already challenging.

Figure 3: Variation in Intended Celebration

Variation in Intended Celebration. Over 4 in 5 Brits expect to celebrate Christmas this year, and 2 in 3 expect to celebrate New Year. Only 1 in 5 expect to celebrate Bonfire Night, less than half as those who celebrated it in the past years,

It is possible that the biggest danger being presented by Bonfire Night and more generally in the week prior to and after 5 November is the public expression of growing frustrations with COVID-19 related restrictions. The incident in Harehills, Leeds, last November is a useful analogy[footnote 85]. Nine police officers were hurt by fireworks and missiles when trying to close down an unlicensed street firework party staged by Slovakian Roma. Fifteen were arrested. It is notable that on this occasion, community mediators were unable to quell the disturbance, which lasted for several hours. This area of Leeds is already positing a challenge in terms of Covid enforcement, so trouble should be anticipated there. However, it provides an example of what could occur in many urban areas.

Transmission of the virus is the primary risk associated with celebrations and observations when transmission rates are high. Other risks (for example social unrest) may become greater if transmission rates are under control and declining when a celebration is supposed to occur. The danger is that ‘celebrations’ become sites of resistance - which has been the case historically; ‘carnivals’ as ‘quiet riots’. Consideration and support must be given to young people who may face a decision to remain at or return from university during the holidays. They will need guidance to enable them to weigh up the risks of transmission to their loved ones and balance this with a desire to see their family over the holidays. This also applies to young adult children working away who will be expecting to return home to parents in their late 40s or 50s whom they may not perceive at risk and who may not see themselves at risk.

Christmas will be extremely difficult in terms of managing legitimacy if families cannot get together. Enforcement issues will be different at New Year where house parties may be prolific.

Communication

A number of sources point to a growing distrust of the government and their measures since the beginning of the pandemic, particularly among certain sections of the country.[footnote 86] This goes beyond the small but active libertarian minority who oppose all the health protection measures,[footnote 87] and includes both Leavers and Remainers,[footnote 88] and the wider population.[footnote 89] Therefore, a key issue is how to communicate any new measures or restrictions in a way that the public will listen to. The communication source should be considered (for example how is the message best communicated other than by a government source?). It may be possible for new community champions networks to be used to communicate measures in the areas where volunteering has been extensive. Although care must be taken that all communities, especially minority and disadvantaged ones are involved in the communications. This could perhaps be best achieved through a combination of GPs, local public health officer and community champion YouTube webinars along with the use of local radio and TV station debates.

Messaging about celebrations and observances

Steps can be taken to encourage adherence to restrictions while allowing for public “celebration” in some form:

Move away from focusing on ‘winter festivities’ to consider the behaviours, enablers, and challenges associated with celebrations throughout the year

There are shared practices across different celebrations and many of the values associated with these are similar, for example time to reflect, have fun, spend time with loved ones. There is an opportunity to draw on these similarities when sharing messages about enabling celebrations, particularly Christmas which some community members will compare with Eid being disrupted the night before.

As a way of increasing social cohesion, messaging could draw on similarities between faiths. For example, Judaism, Christianity and Islam and are Abrahamic faiths with shared history (for example religious texts for Muslims include the Bible and Torah) and so the importance of the religious aspect of Christmas will be recognised. Local religious leaders of all faiths could share messages reminding communities about the religious importance of Christmas and identify it as a positive sign that gives hope to all faiths through the collective identity of faith. In contrast, Christmas also has non-religious elements that others can relate to and using multiple credible sources (not only faith leaders) the cultural elements of festivities that people can relate to or might participate in should also explicitly target minority ethnic groups. For example, turning Christmas lights on is for everyone, Christmas meals as part of cultural celebrations, how to enjoy time off over Christmas holidays with family in a COVID-secure way. Creating a shared norm grounded in traditional norms for the ways in which community leaders, communities, and households manage the majority of these behaviours during COVID-19 will leave room for some of the more detailed messaging about event-specific behaviour related to some celebrations.

Promote shared values

Messaging should promote the values that have been retained, highlighting what celebrations are designed to achieve while managing risk and ‘protecting’ things or people that are important to them (for example community, NHS, individual, family). To achieve this, messaging needs to clearly state which risks are being managed by alternative behaviours (for example socially distant but still connected - if virtual celebratory meals are being promoted). Shifting communications and language towards discussions of how we protect what is important to us when gathering (and not just celebrating) will facilitate continuity in norm recognition. Once again, this creates links with the protected rights of public assembly and covers all forms of gathering including celebration, religion, protest, and more, and lends itself to discussions of how to enable assembly, expression and belief under conditions of the pandemic.

It is important to note that activities such as Bonfire Night and Halloween attract crowds but are not really celebrations in the same way as Christmas or Diwali. The crowd dynamics and bonds connecting members of crowds differ considerably.

Co-design and Engagement

Co-production that is embedded at a local level, fit for purpose, supportive of procedural justice and is equity-generating, and evaluated for effectiveness will go a long way to preventing the development of interventions and substitution behaviours that lack relevance or public acceptability[footnote 90].

Messaging about celebrations will need to be tailored to increase reach and accessibility for different communities. Using the principles of co-design, messages should be developed that include the identities and social and cultural norms of the target community and should be pre-tested, particularly when translating key guidance to ensure the message has been translated appropriately using language that retains cultural context and meaning, and is delivered using credible sources within the community.

Co-design can go a long way in identifying and developing approaches to realising shared values. For example, greater involvement of local mutual aid groups and neighbourhood groups could better enable communities to join together to promote a shared value. For example, a slogan such as ‘No-one lonely this Christmas’ could be considered as having the potential to create activities where people ensure no-one in their community is alone, that everyone receives cards and seasonal food, that opportunities for involved in communal activities are accessible by all, and by providing help where necessary in order to make this a reality.

Another example that applies to all celebrations focuses on the development of a shared understanding of the role of ‘Covid Marshals’. Who are they? What ‘enforcement’ role might they play in terms of promoting self-regulation and adherence within communities, particularly those more marginalised communities? These communal obligations – to the extent that they stress communal identity – can be powerfully motivating.

Transparency

Transparency is a basic principle of effective risk communication.

It is important to acknowledge past abrupt disruptions and the anger that resulted from this. Explain the context. This could include context from the time these decisions were made regarding uncertainty, lack of data, rising infection rates or lack of experience around lockdown and celebrations that led to the disruption (What we knew).

Explain clearly the current situation or context. This could include additional data, clear increases or decreases in infection rate, additional knowledge about the virus and transmission, increased testing capacity) (What we know). Try to establish what will be done for all COVID-19 constrained celebrations in the future by tying the actions to infection rates. Set a framework going forward if infection rates (for example local; national) reach a particular level, then expect these restrictions or easings (such as What we will do).

Communicate likely scenarios in advance:

Individuals and groups are more likely to follow plans if they plan ahead. Additionally, individuals and groups are more likely to have the ability to adapt their plans if they know that changes will be needed in advance. If the authorities believe that a restricted Christmas is a real possibility, they should say so now. Sensitivity is required and clear messaging is needed to ensure that members of the public are not left feeling that the entire celebration or observance event is cancelled. Celebrations and observances are made up of combinations of traditions, rituals, and practices. Some of these will still be possible, while others will require less risky alternatives to be identified and enabled. Consideration must be given to the ability of different communities to engage in the alternative behaviours (for example the digital divide).

This will give individuals, households, and communities additional time to co-create substitution events and behaviours. It will also avoid disappointment and wasted effort on the part of those who stick to their original, traditional preparations if they are cancelled closer to the event. Advanced notice of curtailments may also enable companies to increase their capacity to deal with online deliveries for gifts and food. Forbes (2007) argues for the benefits of conscious decision-making about what adds value to Christmas celebrations. This needs to occur before the festive period begins[footnote 91].

Communicate the Do’s as well as the Don’ts[footnote 92]

It may be that, at the moment, many things that people will be doing are ‘out of bounds’, BUT if there is something that people CAN do, we should identify that and produce ‘can do’ guidance. This makes room for conversations about enablement and facilitation.

Acknowledge and communicate variations in rules clearly for all celebrations

There needs to be clarity in the guidelines for secular and religious celebrations and observances as multiple guidelines (local versus national) are leading to some confusion. This will be exacerbated if there are short-term exceptions in place for certain celebrations and observances. This could lead to confusion about when guidelines are or are not applicable and where in terms of regional variations.

When applied to gatherings, people compare one type of gathering to another. ‘Why can I gather in that context (work) but not in another (family). Office Christmas parties are just one example of where the rules may be interpreted to allow gathering beyond the rules. The rule of 6 does not apply in a work environment, so office parties and parties at some restaurants may be perceived as being allowed on the basis of a ‘business meeting’, while families are unable to celebrate with loved ones. This adds to the sense of the illegitimacy of the guidance or rules and hence lack of adherence.

In conclusion, an effective communication campaign or approach to enabling a combination of traditional and alternative behaviours during celebrations and observances that maintain values and norms will focus on:

- Celebrations throughout the year, rather than just one celebration for one group.

- The promotion of shared values

- Co-design and engagement

- Transparency

- Pro-active communication of likely scenarios

- Do’s as well as the Don’ts

- Acknowledging and clarifying variations in rules to maintain legitimacy

What does this mean for Christmas?

Research shows that ‘Christmas has moved from being perceived as a religious holiday, to more of a commercial and consumption driven event’[footnote 93]. Christmas creates important opportunities to acknowledge and strengthen significant social bonds[footnote 94]. In some cases, Christmas provides the only opportunity in the year to recognise and reconfirm kinship ties. Taken together, Christmas and New Year create a shared holiday period that enables people to reflect on their year and think about the future[footnote 95].

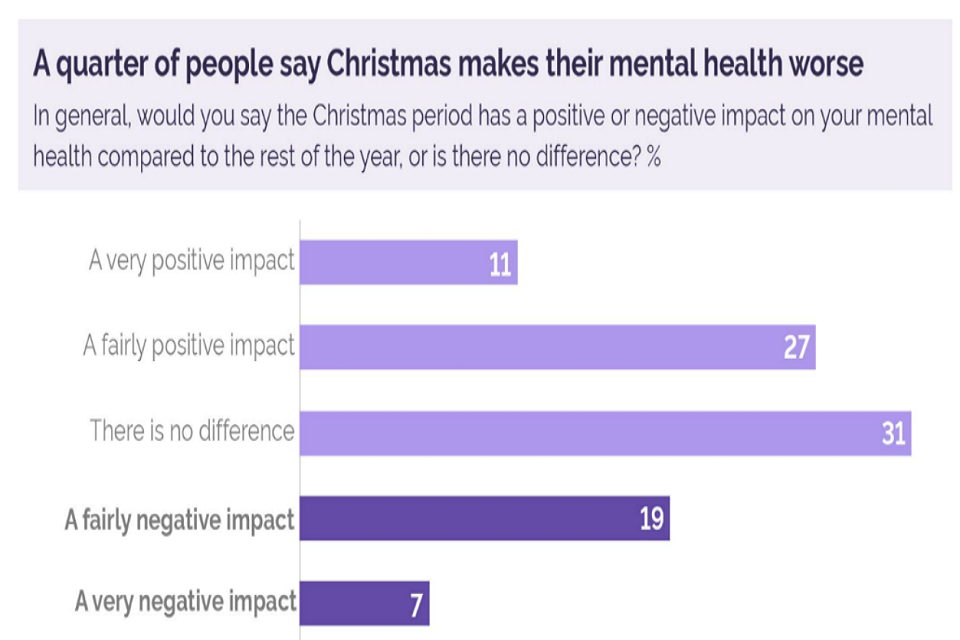

Christmas produces mixed responses amongst the UK population. Many people report that Christmas has a fairly (27%) or very (11%) positive impact, with over one third reporting that it doesn’t make a difference to their mental health.

A quarter of the population report finding Christmas more challenging than the rest of the year, with 26% reporting fairly or very negative impacts on their mental health (Figure 4). Younger people are more likely to find Christmas uplifting, with over half of 18 to 24 year olds reporting better mental health in December, though this effect decreases with age[footnote 96]. An AGE UK study found that Christmas was the loneliest time of the year for over 1.5 million people.

The range of mixed experiences suggests that the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions over the Christmas holidays will produce mixed responses. Some people may feel relieved that they do not have to engage with the stress of cooking large meals, organising gift exchanges, entertaining guests, and more. Some will have their only opportunity to strengthen friendships and kinship ties disrupted. Others will feel lonely irrespective of whether Christmas is celebrated in the usual way, or not. Finally, others will feel disappointed and angry that such a meaningful part of their lives has been disrupted.

Figure 4: Mental health impacts of Christmas in the UK

Mental health impacts of Christmas in the UK. A quarter of people say Christmas makes their mental health worse.

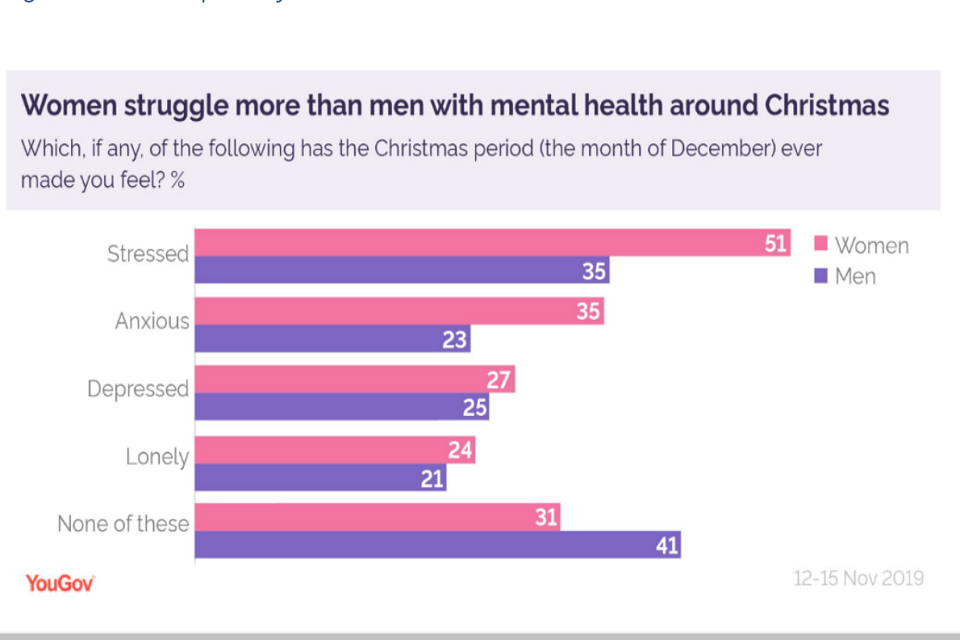

Christmas is especially tough on women’s mental health. While women are only four percent more likely to say Christmas affects them negatively, the difference is more glaring when it comes to stress and anxiety. While only 35% of men have felt stressed around Christmas, for women the figure is 51%. Over a third of women also say they have felt anxious, whereas less than a quarter of men say the same[footnote 97] (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The Impact of Christmas on Mental Health in Men and Women

The Impact of Christmas on Mental Health in Men and Women. Women struggle more than men with mental health around Christmas.

In spite of this, 63% of respondents reported that they are looking forward to Christmas ‘A great deal or a fair amount’ in comparison to 32% who reported that they are not[footnote 98], even in the face of COVID-19. Additionally, 51% of respondents believe that they will enjoy Christmas more (11%) or the same as normal (40%) as last year with 39% expecting to enjoy it less[footnote 99]. What do members of the UK public think that a COVID-Christmas will entail?

Behavioural Expectations and Intentions Over Christmas During COVID-19

Celebration and observance behaviours must change to prevent the risk of infection during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is not an all or nothing decision. Alternative behaviours and Christmas restrictions do not mean that traditional behaviours cannot take place. Rather, a combination of traditional and alternative approaches will shape the ways in which we celebrate while the risk of infection continues.

This Covid-Christmas will be characterised by decreases in intention to celebrate, travel, and to mix with friends and family. The British public are almost evenly divided over whether or not Christmas will be celebrated this year[footnote 100] (Figure 6). Figure 3 (above) illustrated a reduction in the number of respondents intending to celebrate Christmas this year (85%), compared to last year (95%). Whether they celebrate or not, they intend to change their behaviour. In fact, they are already changing their behavioural intentions for the holiday season.

Figure 6: Perceived Likelihood of holidays going ahead as normal this year

Perceived Likelihood of holidays going ahead as normal this year. Less than half of Brits are more optimistic about Christmas being celebrated as normal this year compared to other festivities.

The shape of celebrations and observances may change, but the public appetite for Christmas celebration is still high. High levels of intended Christmas celebration do not automatically translate to significant levels of travel or visits with family and friends.

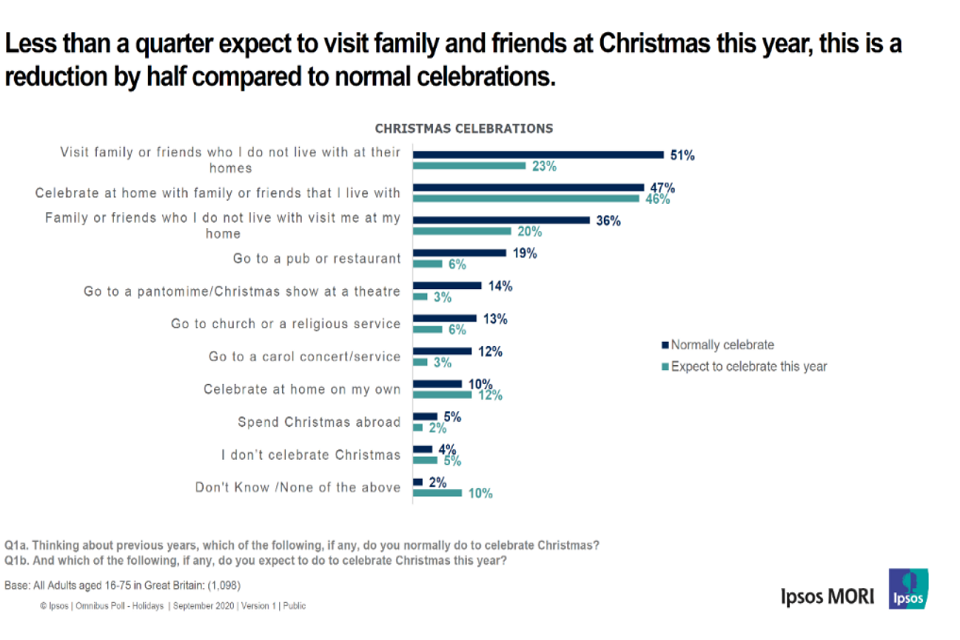

Pre-Covid levels of Christmas travel found that more than half of Britons expected to spend Christmas day in their own home in 2019[footnote 101]. This was especially true for those who were married or in civil partnerships opting to spend Christmas with their partner and or children (86%). Unmarried individuals reported that Christmas would be spent with their parents (67%) or other family members (50%), or friends. In contrast, the September 2020 Ipsos MORI Omnibus Poll noted a significant reduction in intention to visit family and friends at Christmas this year, with only half of British participants who usually celebrate Christmas outside of their home intending to do so this Christmas (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Behavioural intentions over Christmas during COVID-19

Behavioural intentions over Christmas during Covid-19. Less than a quarter expect to visit family and friends at Christmas this year, this is a reduction by half compared to normal celebrations.

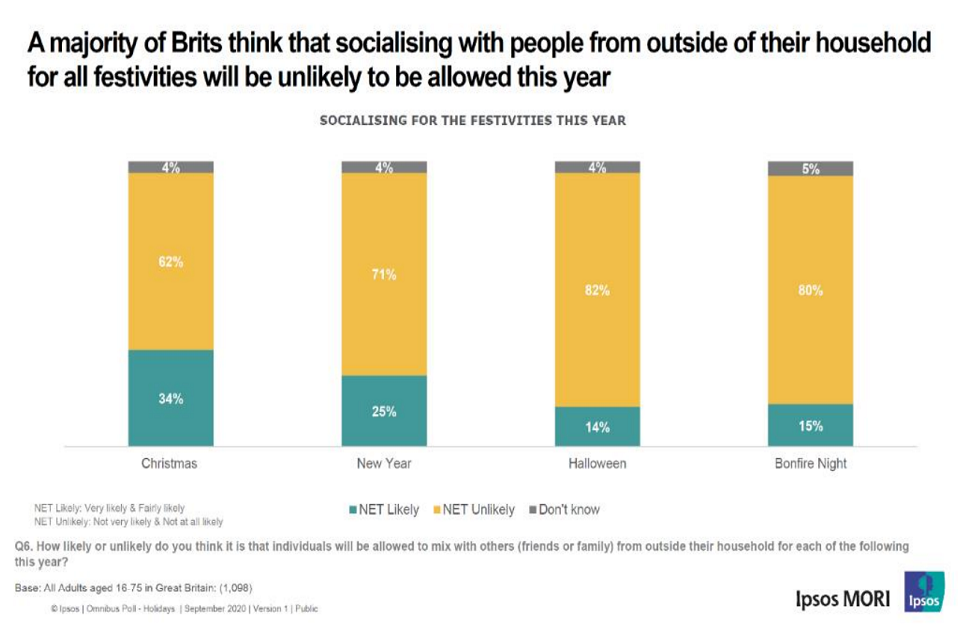

Decreases in intention to have family or friends visit at home, eat out at pubs or restaurants, attend pantomimes, church, and carol concerts were also reported[footnote 102]. Celebrations will take place, but a majority of British respondents reported that they do not think that they will be allowed to socialise with people outside of their social bubbles for all festivities this year[footnote 103] (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Public expectations for socialising outside of the household for festivities

Public expectations for socialising outside of the household for festivities. A majority of Brits think that socialising with people from outside their household for all festivities will be unlikely to be allowed this year.

Enabling Behaviour Change During A COVID-Christmas

People are already changing their plans and intended behaviour for the upcoming Christmas. Members of the public are planning to travel less, visit friends and loved ones less, let fewer non-household members into their home, and attend fewer indoor and outdoor events.

Members of the public are still reporting high levels of intended celebration, continue to look forward to the holiday, and a majority believe that they will enjoy Christmas despite COVID-19 restrictions.

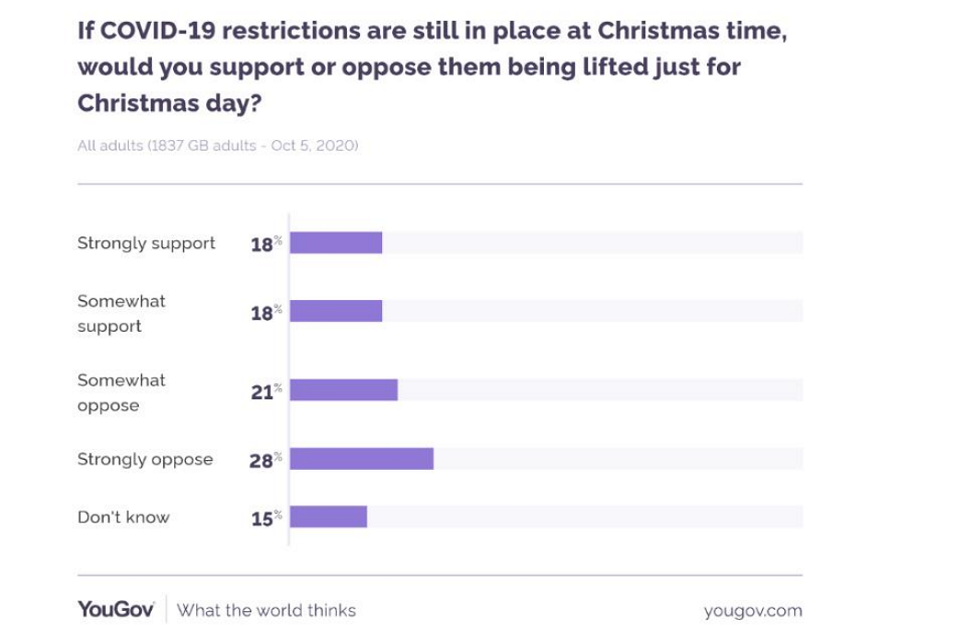

Additionally, as the Christmas advert season will be upon us soon, 54% of YouGov respondents (N=3390 GB Adults) believe that Christmas adverts should acknowledge COVID-19, with a quarter remaining undecided[footnote 104]. In spite of public intentions to change their behaviours over the Christmas holidays, the population is divided on whether or not they support or oppose COVID-19 restrictions being lifted just for Christmas day. A recent YouGov survey of 1837 GB adults found that 36% of respondents somewhat or strongly supported an amnesty, 49% were somewhat or strongly opposed, and 15% were unsure[footnote 105] (Figure 9).

A lack of information around the imposing or lifting of COVID-19 restrictions over the Christmas holidays risks the creation of a Christmas paralysis in public planning, resulting in unsatisfactory and unexciting celebratory options if restrictions are needed.

Figure 9: Support for COVID-19 Restriction Amnesty on Christmas Day

Support for COVID-19 Restriction Amnesty on Christmas Day. 28 per cent of people strongly oppose a Christmas Day amnesty on COVID-19 restrictions.

Public expectations about COVID-19 restrictions over Christmas must be informed sooner, rather than later. Forbes (2007) explains that if we want things to change from a hectic Christmas, we need to sit down before the season starts and choose what kind of Christmas we would like to have, this is more important this year than most, rather than just letting it happen. Conscious decision-making about what adds value to family Christmas needs to occur before the festive period.[footnote 106]

Planning can take place on an individual, family, community, and national level. Conversations should focus on the activities that people can still do, or develop themselves, the importance of continuing with traditions, creating new traditions, spending time as a family, enjoying a slower pace of life. These have the potential to create positive feelings[footnote 107].

For example, some communities are already planning a window advent event, which requires 24 houses to participate in a local area. It also enables children and families to walk around the streets at a safe distance and enjoy the excitement of finding something new[footnote 108]. In this case, old traditions are being translated into new traditions to build community cohesion.

Additional discussions about alternative forms of celebration are needed. These can create opportunities to revive communal rituals and events that have fallen into abeyance as Christmas and other ceremonies become more and more consumerised. As the ‘invention of tradition’ literature shows, new forms are more powerful if they can refer back to something previous[footnote 109],[footnote 110],[footnote 111].

In addition to the challenges to developing, informing, and supporting alternative celebration behaviours, Christmas brings a few unique challenges:

-

The importance of family engagement and religious experience during the Christmas holidays poses a particularly challenging problem for families during the Coronavirus pandemic. Kasser and Sheldon’s (2002) research into personal experiences of Christmas found that higher levels of happiness were reported when family and religious experiences were special, in contrast to lower levels of well-being when events focussed on money and receiving gifts[footnote 112].

-

Women carry the burden of creating and maintaining family traditions and activities at Christmas. These traditions are informed by the preferences of partners and children. “Messaging should be supportive of women adapting traditions and encouraging those around them to share the burden and to be supportive of any alterations to adapt for COVID-19 restrictions”[footnote 113].

-

People who may be willing to accept restrictions, themselves, may be less willing to do things that would distress their children. This can be informed by the perceived moral right to accept hardship for ourselves, but not to impose it on others, especially fragile and vulnerable others. Given the importance of Christmas for children, people may be far more reluctant to abandon old ways. There are opportunities to involve children in the co-design process, enable their creativity, and inspire them to be agents of change for the alternatives they create. Supporting discussions and exercises in schools about creating safe Christmas rituals and enabling neighbourhood competitions for the best idea could be very powerful.

-

It is likely that the mental health burden of the holidays will be felt more acutely by many, especially those who have lost or been separated from loved ones during COVID-19. The mental health impacts of Christmas and the New Year cannot be ignored. While the variable evidence around increased demands on hospital admissions and ambulance responses did not indicate a need to render the Christmas period worthy of a separate approach, the reported negative impacts of Christmas on mental health and well-being, and the demand on mental health services beyond the NHS did. Restrictions and alternative behaviours must be discussed with charitable organisations such as AGE UK, Samaritans, and MIND, among others. Charitable organisations cannot be left out of the equation when finding ways to create meaningful engagements during COVID-19.

-

Short-notice disruption of previous celebrations must be acknowledged when speaking about Christmas allowances or restrictions. What was the context in which these decisions were made (for example infection rate, testing capability, existing rules in place, knowledge of the virus and modes of transmission, NHS capability), how has this changed, and why is Christmas (or any other celebration) being treated in a different way? Moving away from a focus on winter festivities is useful, as it requires communicators to acknowledge similar practices and values across different celebrations.

-

People must be made aware of the risks associated with traditional celebratory and observance activities. They need to be aware of the options open to them in respect to restrictions and freedoms in order to plan. Lack of planning leads to lack of adherence and a less than rewarding holiday season.

-

Prime Minister’s Office Press Release. Coronavirus: Government launches campaign urging people to stay at home this Easter. April 2020. ↩

-

Manchester Evening News. How will Eid celebrations be impacted by the pandemic after coronavirus spikes in Greater Manchester? July 2020. ↩

-

Gardner, Katy, and Ralph Grillo. “Transnational households and ritual: an overview.” Global networks 2.3 (2002): 179-190. ↩

-

Di Leonardo, Micaela. “The female world of cards and holidays: Women, families, and the work of kinship.” Signs: Journal of women in culture and society 12.3 (1987): 440-453. ↩

-

Caplow, Theodore. “Christmas gifts and kin networks.” American sociological review (1982): 383-392. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. Mason J and Muir S (2013). Conjuring up Traditions: Atmospheres, Eras and Family Christmases; Kasser T and Sheldon KM (2002). What Makes for a Merry Christmas?. Journal of Happiness Studies 3, 313-329. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

Savanta: ComRes. Church of England Mapping Survey. September 2017. ↩

-

Bear et al. A Good Death During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK ↩

-

Morphy, Frances. “Soon we will be spending all our time at funerals: Yolngu mortuary rituals in an epoch of constant change.” Returns to the field: multi-temporal research and contemporary anthropology. Indianna University Press, 2015. ↩

-

Fedele, Anna. Looking for Mary Magdalene: Alternative pilgrimage and ritual creativity at Catholic shrines in France. Oxford University Press, 2013. ↩

-

Lourenco, Ines, and Rita Cachado. “Hindu transnational families: transformation and continuity in Diaspora families.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 43.1 (2012): 53-70. ↩

-

Jacobs, Stephen. “Virtually sacred: The performance of asynchronous cyber-rituals in online spaces.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12.3 (2007): 1103-1121 ↩

-

ONS. Research report on population estimates by ethnic group and religion. December 2019. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper. September 2020. ↩

-

Ipsos Mori – Omnibus Poll. Public Perceptions of Holidays in 2020. September 2020. ↩

-

YouGov. If COVID-19 restrictions are still in place at Christmas time, would you support or oppose them being lifted just for Christmas day? October 2020. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

ONS. Festive Analysis: Trends in UK Card Transaction Data [OFF-SEN]. 2020. ↩

-

ONS. RAC travel data. 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B and Environmental Modelling Group. COVID-19 Housing Impacts Report. September 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B. Evidence Review on Housing Impacts. September 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B. Evidence Review on Housing Impacts. September 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B and Environmental Modelling Group. COVID-19 Housing Impacts Report. September 2020. ↩

-

NHS North East Ambulance Service. Public urged to think before they dial 999 over Christmas and New Year. 2018. ↩

-

NHS England. 2015.06.28 A&E Timeseries. June 2015. ↩

-

NHS England. Winter SitRep – Acute Time series 2 December 2019 – 1 March 2020. ↩

-

NHS England. NHS 111 Minimum Data Set, England, December 2019. ↩

-

YouGov. Christmas harms mental health of a quarter of Brits. December 2019. ↩

-

Requests for help came in via phone calls, text messages, face-to-face meetings, e-mails, and letters. ↩

-

Samaritans. Impact Report 2018/2019: Listening today, changing tomorrows. ↩

-

Samaritans. Yule not go lonely for Christmas with Samaritans. December 2019. ↩

-

MIND. Third of people too embarrassed to admit they are lonely at Christmas. December 2017. ↩

-

Datta, Anita. “‘Virtual choirs’ and the simulation of live performance under lockdown.” Social anthropology. (2020). ↩

-

Phelan, Helen. “Practice, ritual and community music: Doing as identity.” International Journal of Community Music 1.2 (2008): 143-158 ↩

-

PHE/EMG. Aerosol and droplet generation from singing, wind instruments and performance. August 2020. ↩

-

Gregson, Watson, Orton, Haddrell, McCarthy, Finnie, Gent N, Donaldson, Shah, Calder, Bzdek, Costello, Reid J (2020). Comparing the Respirable Aerosol Concentrations and Particle Size Distributions Generated by Singing, Speaking and Breathing. Chemrvix pre-print. ↩

-

Ratcliffe, Eleanor, Weston Lyle Baxter, and Nathalie Martin. “Consumption rituals relating to food and drink: A review and research agenda.” Appetite 134 (2019): 86-93. ↩

-

Vandevoordt, Robin. “The politics of food and hospitality: How Syrian refugees in Belgium create a home in hostile environments.” Journal of Refugee Studies 30.4 (2017): 605-621. ↩

-

Environmental Modelling Group. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Mitigating Measures. June 2020. ↩

-

Vierlboeck M, Nilchiani RR and Edwards CM (2020). The Easter and Passover Blip in New York City; C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

Venkatesan, Archana. “Virtual Hinduism: A survey of sources for the study of Hinduism on the world wide web.” Religious Studies Review 32.4 (2006): 230-232. ↩

-

Scheifinger, Heinz. “Om-line Hinduism: World Wide Gods on the Web.” Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 23.3 (2010): 325-345. Scheifinger, Heinz. “Hinduism and cyberspace.” Religion 38.3 (2008): 233-249. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

Teo, A, Nagchoudhury, S, and Hassan, S. (2020). Muslims perform Eid prayers, socially distanced and masked. ↩

-

NHS Wolverhampton Clinical Commissioning Group. Celebrate Eid safely by observing social distancing. May 2020. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B: Positive strategies for sustaining adherence to infection control behaviours, October 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B. Positive strategies for sustaining adherence to infection control behaviours. October 2020. ↩

-

Davies C, Wetherell M, and Barnett E (2006). Citizens at the Centre: Deliberative Participation in Healthcare Decisions; Wright DNM, Corner JL, Hopkinson JB & Foster CL (2006). How to involve cancer patients at the end of life as co-researchers. ↩

-

SPI-B. Principles for co-production of guidance relating to the control of COVID-19. July 2020. Available from the SPI-B Secretariat. ↩

-

SPI-B. Principles for co-production of guidance relating to the control of COVID-19. July 2020. Available from the SPI-B Secretariat. ↩

-

SPI-B. Principles for co-production of guidance relating to the control of COVID-19. July 2020. Available from the SPI-B Secretariat ↩

-

SPI-B. Positive strategies for sustaining adherence to infection control behaviours. October 2020. ↩

-

Maxmen A. How the Fight Against Ebola Tested a Culture’s Traditions. January 2015. ↩

-

Park C. Traditional funeral burial rituals and Ebola outbreaks in West Africa: A narrative review of causes and strategy interventions. Journal of Health and Social Sciences, 2020. ↩

-

Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, and Wetherell M. (1987) Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Turner JC. Social Influence. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1990. ↩

-

Environmental Modelling Group. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Mitigating Measures. June 2020. ↩

-

Facebook. Public Group: The Big Neighbourhood Pumpkin Trail. October 2020. ↩

-

Environmental Modelling Group. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Mitigating Measures. June 2020. ↩

-

Environmental Modelling Group. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Mitigating Measures. June 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B. Positive strategies for sustaining adherence to infection control behaviours. October 2020. ↩

-

Covid-19 Mutual Aid UK. See: https://covidmutualaid.org/. ↩

-

Jackson J, Posch C, Bradford B, Hobson Z, and Kyprianides A. The lockdown and social norms: Why the UK is complying by consent rather than compulsion. LSE BPP, April 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B. Extended paper on behavioural evidence on the reopening of large events and venues. August 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B. Consensus statement on the re-opening of large events and venues. August 2020. ↩

-

GOV.UK. Coronavirus (COVID-19): guidance on the phased return of sport and recreation. May 2020. ↩

-

Ainsworth B, Miller S, Denison-Day J, Stuart B, Groot J, Rice C, Bostock J, Hu X, Morton K, Tolwer, L, Moore M, Willcox M L, Chadborn T, Gold N, Amlot R, Little P, and Yardley L. Current infection control behaviour patterns in the UK, and how they can be improved by ‘Germ Defence’, an online behavioural intervention to reduce the spread of COVID19 in the home. medRxiv pre-print, June 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B: Positive strategies for sustaining adherence to infection control behaviours, October 2020. ↩

-

Bear et al (2020). ‘A Right to Care: the social foundations for recovery from Covid 19’ ↩

-

The Guardian. Lockdown rules won’t be respected if they prioritise business over human relationships. Oct 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B. The role of Community champion networks to increase engagement in the context of COVID-19: Evidence and best practice. October 2020. ↩

-

Petty RE and Wenger Duante T (1998). Attitude change: Multiple roles for persuasion variables. ↩

-

Little KB. Personal Space (1965). Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1(3), 237-247. ↩

-

Novelli D, Drury J, and Reicher S (2010). Come together: Two studies concerning the impact of group relations on personal space. British Journal of Social Psychology, 49(2), 223-226. ↩

-

GOV.UK. SPI-B Insights on public gatherings. 12th March 2020. ↩

-

Bear et al (2020). ‘A Right to Care: the social foundations for recovery from Covid 19’ ↩

-

N= 1,098 adults aged 18-75. ↩

-

Ipsos Mori – Omnibus Poll. Public Perceptions of Holidays in 2020. September 2020. p.2. ↩

-

N= 1,098 adults aged 18-75 ↩

-

Ipsos Mori – Omnibus Poll. Public Perceptions of Holidays in 2020. September 2020. p.10. ↩

-

Yorkshire Evening Post. Everything we know about Harehills road violence on Bonfire Night 2019. November 2019. ↩

-

Maher PJ, MacCarron P, Quayle M. Mapping public health responses with attitude networks: the emergence of opinion‐based groups in the UK’s early COVID‐19 response phase. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2020 59(3): 641-652. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12396 ↩

-

The Independent. Anti-lockdown, anti-vaccine and anti-mask protesters crowd London’s Trafalgar Square. August 2020. ↩

-

Gaskell J, Stoker G, Jennings W, and Devine D (2020). Will getting Brexit done restore political trust? ↩

-

Fancourt D, Bu F, Mak HW, and Steptoe A. (2020). Covid-19 Social Study: Results Release 16 (July 2020). UCL Department of Behavioural Science & Health. ↩

-

SPI-B. Principles for co-production of guidance relating to the control of COVID-19. July 2020. Available from the SPI-B Secretariat. ↩

-

Forbes, B. (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press; C19 National Foresight Group & Nottingham Trent University. National Foresight and Intelligence Briefing Paper [OFF-SEN]. September 2020. ↩

-