Seasonal workers survey results 2024

Updated 16 July 2025

Executive Summary

This document provides a summary of results from a survey of workers who were issued Seasonal Worker visas and came to work in the UK during 2024. The purpose of the survey is to gain insight into workers’ experience to understand what went well and where improvements may be needed. The survey was conducted between 19 December 2024 and 3 March 2025. Further information on the Seasonal Worker visa route can be found here on GOV.UK.

In line with our commitment to continual improvement, the survey questions were updated in 2024. Whilst maintaining comparability with previous surveys as much as possible, the 2024 survey questions incorporated an increased focus on workers’ on-farm experience and finances.

Overall, there were 14,012 responses to the 2024 survey, a 39.4% return rate (similar to the 42.5% response rate in 2023). Almost all survey respondents were from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan in Central Asia (91.5% of all respondents, or 12,825 responses), with Kyrgyzstan having the greatest representation for any single nationality (34.8% of all respondents, 4,879 responses).

Recruitment and pre-arrival costs

Nearly all respondents (94.4%) stated they paid for their visa, whilst 56.7% of respondents reported paying for travel costs to the UK.

Aside from these costs, a small proportion of respondents also stated they incurred other pre-arrival costs, the most reported of these being Migration or Labour Ministry fees (13.3%).

Most respondents stated they paid their costs from their own savings (59.1%), with 27.4% paying their costs through loans from family and friends.

Most respondents (between 79.2% and 88.2%, depending on the topic in question) considered the information provided to them during the recruitment process as accurate. This included information on accommodation costs, pay rates and contract length.

Contracts, pay and hours worked, and duration of work

The survey found that almost all respondents (96.2%) were provided with a contract in a language they could understand (either their first language or a language they were fluent in).

More than nine out of ten respondents (96.2%) stated they were paid for all the work they performed, with 96.7% being provided with at least an average of 32 hours of work per week, and 91.4% working in the UK for over 4 months.

Costs in the UK and on-farm experiences

Responses to the survey indicated that workers on the Seasonal Worker visa route were content with their working and living conditions whilst in the UK, with between 84.0% and 95.2% of respondents answering they were ‘happy’ for each topic, which included accommodation, pay, operator support, and safety.

Apart from essentials (food and accommodation, for example), the most frequently reported costs whilst in the UK were travel to the respondents’ first farm and between farms (42.3%).

Complaints, transfers, and access to healthcare

Over three quarters of respondents (81.8%, or 10,259 responses) stated they knew how to raise a complaint. The majority of respondents (87.2%, or 10,915 responses out of 12,524 who answered this question) stated that while working in the UK they did not have a grievance or feel the need to raise a formal complaint. A small proportion (2.0%, accounting for 245 responses) stated that they had raised a formal complaint.

In terms of transfers, 19.3% of respondents (2,427 responses) stated they had requested a transfer to another farm, with the most significant reasons being the lack of hours on their current farm (38.5% or 929 responses) and to be with friends (22.2% or 535 responses).

When considering access to medical care, only 6.4% of respondents (798 responses) stated they needed medical treatment due to sickness or injury while in the UK.

Overall satisfaction

Almost all respondents (94.2%) reported they had a ‘positive’ or ‘extremely positive’ experience working in the UK, and 96.9% expressed a desire to return to the UK through the Seasonal Worker visa route.

Different experiences by nationality, age, gender and country of work within the UK

The survey identified variation in answers across nationalities. For example, Uzbek respondents most frequently reported having paid Labour or Migration Ministry fees prior to arrival in the UK (43.1% compared with the overall proportion of 13.3% among respondents to that question). Additionally, a lower proportion of respondents from the ‘other’ nationality group (all nationalities other than the four largest source countries for workers: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) reported they were transferred after making a request (36.8% were transferred compared with the overall proportion of 57.7% among respondents to that question).

Survey responses also revealed some differences in experience between age groups. For example, from the youngest analysed age group (18 to 24 years) to the oldest (39 years or older), there was a declining trend in the proportion of respondents who stated their payslip did not clearly explain tax or National Insurance (or both).

Similarly, the results indicate that respondents’ experiences might have varied depending on their gender. For instance, female respondents more frequently reported that their complaints were followed up (75.0% compared with 59.7% of male respondents).

Survey results suggest that respondents’ experiences were also influenced by whether they spent most of their working time in England or in Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales. For example, compared with respondents who primarily worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales, respondents who spent most of their time working in England reported more frequently that they moved farms after making a request to be transferred. Of respondents who primarily worked in England, 59.4% of those who stated they requested a transfer were moved as a result, compared with 45.9% of those who primarily worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales who requested a transfer (see Annex D Table D4).

Comparison with previous worker welfare surveys

The questions for the 2024 survey were updated and, whilst similar to the 2023 survey, there are differences between them which mean direct comparisons are not always possible. However, some broad trends can be identified.

Many areas showed similar results, including the provision of a contract in a language the respondents could understand (96.2% in 2024 versus 94.4% in 2023 and 94.5% in 2022), number of weekly hours of work (96.7% for over 32 hours in 2024 versus 93.9% in 2023, and 94.7% for over 30 hours in 2022), respondents being ‘happy’ with on-farm conditions such as accommodation (93.4% in 2024, compared with 91.2% in 2023 and 88.3% in 2022), and those stating they would work on a UK farm again (96.9% in 2024, compared with 95.0% in 2023 and 91.4% in 2022).

There were also areas which indicated more pronounced improvements. For instance, there was a positive upwards trend in the proportion of respondents who reported they were paid for all the work they did, rising from 85.9% in 2022, to 87.9% in 2023 and 96.2% in 2024. In 2024 a higher proportion of respondents noted that the information they received during recruitment was accurate (84.5% versus 80.4% in 2023) (comparison with 2022 is not possible as the answer options changed slightly between survey years).

Conversely, there were also some downward trends, including a reduction in the proportion of respondents who reported their transfer request was granted, which declined from 64.9% in 2023 to 57.7% in 2024.

The 2023 workers survey report can be found here on GOV.UK for comparison.

Section A – Introduction to the 2024 seasonal workers survey results

This report presents the results of the 2024 seasonal workers survey. The survey questionnaire was distributed on 19 December 2024 to migrant workers with Seasonal Worker visas issued in 2024.

The seasonal workers survey is a monitoring tool used by the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (Defra) to gain insights into the experience and welfare implications of workers on the Seasonal Worker visa route. The survey has been run each year since 2019.

In line with our commitment to continual improvement, the survey questions were updated in 2024 in partnership with industry and NGO (non-governmental organisation) stakeholders, building on revisions made for the 2023 survey. Whilst maintaining comparability with previous surveys as much as possible, development of the 2024 survey included additional clarifying questions and options related to the costs workers incur and their pay (for example, the clarity of the information in their payslips).

As with the workers surveys of previous years, insights and detail from this survey will be used to track the impact of changes made to the visa route’s operation and support future policy development aimed at improving migrant welfare. Data from the 2019 Survey of Workers was published as part of a more comprehensive review. The 2019 survey as well as seasonal workers surveys results for 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023 can be found at Seasonal workers reviews and surveys - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk).

In 2024, the total number of Seasonal Worker visas available for the horticulture sector was 45,000, with an additional 2,000 visas for the poultry sector. Holders of horticulture Seasonal Worker visas are entitled to work for up to 6 months from their time of arrival, whereas holders of poultry Seasonal Worker visas can work for up to 3 months in the poultry sector ahead of peak demand at Christmas.

Official Home Office statistics show that 35,561 Seasonal Worker visas were granted in 2024 (an uplift of 8.5% from 2023). According to data provided to Defra by Seasonal Worker visa route operators, 590 were for poultry.

Between 2023 and 2024, the proportion of Seasonal Worker visa holders who were from Central Asian countries, principally Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, increased by 22% to 27,759 individuals. This represents 78.1% of Seasonal Worker visa holders in 2024. Almost all respondents (98.7%) were working in horticulture with the remaining 1.3% working in the poultry sector, the same split as in the 2023 survey results.

There were six scheme operators licensed to recruit seasonal workers for horticulture during 2024: Pro-Force, Concordia, Fruitful Jobs, HOPS, Agri-HR and Ethero. Pro-Force and a seventh operator, RE Recruitment, were also licensed to recruit for poultry. Scheme operators source and sponsor seasonal workers on behalf of UK growers. A breakdown of the total number of visas issued to seasonal workers by their country of residence can be found in Table 1.

Table 1: Total number of visas issued to seasonal workers in calendar year 2024 (from official Home Office statistics)

(Values were rounded, therefore percentages may not equal 100%)

| Country of residence | Visas issued in 2024 | Percentage of total visas issued in 2024 | Change in percentage of total visas issued, compared to 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kyrgyzstan | 9,842 | 27.7% | +3.3% |

| Uzbekistan | 6,278 | 17.7% | +5.1% |

| Tajikistan | 5,828 | 16.4% | -0.9% |

| Kazakhstan | 5,811 | 16.3% | +1.0% |

| Moldova | 2,040 | 5.7% | -0.8% |

| Kenya | 1,291 | 3.6% | +3.3% |

| Romania | 786 | 2.2% | -1.0% |

| Ukraine | 708 | 2.0% | -5.8% |

| Bulgaria | 673 | 1.9% | -0.8% |

| South Africa | 460 | 1.3% | -0.1% |

| North Macedonia | 351 | 1.0% | -1.7% |

| Turkey | 246 | 0.7% | -0.1% |

| All others | 1,247 | 3.5% | -2.0% |

| Total: | 35,561 | 100.0% |

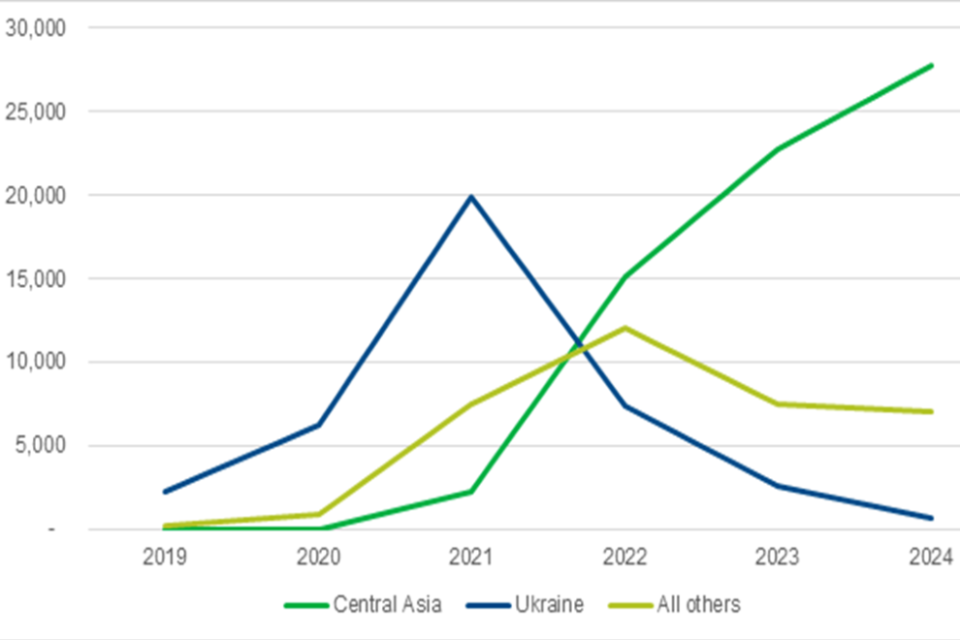

Recruiting workers from the same countries over successive years should improve the safety, certainty and stability of recruitment in those areas, allowing recruiters to make more meaningful connections and establish better relationships in-country. As such, it is common for the same source countries to be used each year. The demographic composition of Seasonal Worker visa holders has, however, changed over the years. During 2022, the visa route gained an expanded visa allocation, but recruitment switched away from being predominantly focussed on Ukrainian and Russian nationals following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Recruitment rapidly pivoted to Central Asian countries (see Figure 1). The Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan were the primary source of seasonal workers between 2022 and 2024.

This shift in countries which are the focus of recruitment is reflected in the demographic composition of survey respondents. For example, 50.2% of respondents to the 2021 survey were from Russia – in 2024, however, Russians made up less than 0.1% of the cohort. In 2022, 15.8% of respondents were from Nepal and Indonesia, while only 0.2% of respondents to the 2024 survey were from Indonesia and none were from Nepal. Respondents from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan accounted for 30.4% of responses in 2021, 73.8% in 2022, 85.9% in 2023, and 91.5% in 2024.

Figure 1: Number of seasonal workers on the visa route from Ukraine, Central Asia versus all other countries, 2019 to 2024

Figure 1: Number of seasonal workers on the visa route from Ukraine, Central Asia versus all other countries, 2019 to 2024.

| Nationality | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Asia | 4 | 16 | 2,231 | 15,142 | 22,752 | 27,759 |

| Ukraine | 2,261 | 6,297 | 19,894 | 7,332 | 2,551 | 708 |

| All others | 228 | 898 | 7,460 | 12,010 | 7,454 | 7,094 |

1. Insights from the seasonal workers survey

The 2024 Survey of Workers was hosted online by survey software Qualtrics. The survey was distributed on Defra’s behalf by all scheme operators who recruited seasonal workers during 2024 and still held a licence by the end of the year.

The annual workers survey collects both quantitative and qualitative data from migrant seasonal workers and provides valuable insights across five dimensions of their welfare:

- Recruitment and pre-arrival costs

- Contracts, pay and hours worked, and duration of work

- Costs in the UK and on-farm experiences

- Complaints, transfers, and access to healthcare

- Overall satisfaction

The 2024 report themes are similar to those from the 2022 and 2023 reports but differ from the themes included in the 2020 and 2021 reports following a greater focus on welfare questions from 2022 onwards.

2. Methodology and analysis

A link to the online Qualtrics-based survey was disseminated between 19 December 2024 and 3 March 2025 by the operators on behalf of Defra to workers that held Seasonal Worker visas for 2024. The survey will, in most cases, have been completed by the worker after they had returned home.

The survey asked a variety of questions on issues such as working experience, accommodation, pay, complaints, and desire to return to the UK for future seasonal work. The survey comprised 30 questions (some with sub-questions), including 2 screening questions and 3 free text fields to gain further detail on respondents’ answers. The questionnaire was translated into 10 languages to make it accessible to most workers on the route.

The survey received 15,379 responses. Analysis was conducted in-house by Defra. Responses were removed for which consent to participate in the study was not provided by the respondent, from participants who did not work on farms in the UK in 2024, and duplicate responses. This left 14,012 completed responses in the final sample, meaning that responses from 39.4% of migrant workers who received Seasonal Worker visas in 2024 are analysed in this report.

The response rate for 2024 was similar to the 2023 response rate (39.4% compared with 42.5%), but much higher than the 12.4% in 2022 and 12.0% in 2021.

The results of the survey are presented as counts and percentages before being broken down by nationality, age, gender, and the country the respondent primarily worked in (either England, or Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales together). These breakdowns are included to identify whether migrants of different demographics, or location of work, have reported different experiences of the UK Seasonal Worker visa route. These results consider the percentage of respondents who selected certain responses which is then compared to the overall proportion of respondents to that question.

For the nationality breakdown, analysis has been limited to responses from countries whose nationals account for more than 5% of the total survey responses (see Table 2), allowing meaningful analysis to be undertaken and conclusions drawn from the results. These are the following countries: Kazakhstan; Kyrgyzstan; Tajikistan; and Uzbekistan. Responses from all ‘other’ Nationality countries are presented as a group.

Analysis was undertaken on free text answers to identify common themes. These were translated into English where necessary. These free text responses were coded thematically to extract and analyse emerging patterns. If an answer in the free text boxes repeated an option present in the first section of these questions, the information was added to the results of the original question.

Respondents did not need to answer all questions, hence the number of responses to each question might differ from each other and from the total number of respondents to the survey as a whole. Similarly, the percentages stated throughout the report relate to the number of responses to the specific question under discussion, rather than to the total number of respondents to the survey. Results have been rounded to a single decimal place, therefore percentages may not equal 100%. Data is represented in tables in the order the answer options were presented to respondents in the survey.

2.1 Limitations of survey

While seasonal migrant workers can be hard to reach as a research population, Defra has made efforts to document the experiences of workers on the Seasonal Worker visa route. This survey provides valuable insight into seasonal workers’ experiences of working in the UK and contributes to the body of literature on the subject of migrant welfare.

The online survey was disseminated to migrant workers via the scheme operators (the recruiters on the route) to reach the maximum number of participants. Respondents submitted their answers on Qualtrics, an online survey tool, which allowed them to contribute their feedback anonymously. Defra downloaded the anonymised results from Qualtrics, ensuring respondents could not be identified by their responses.

There are, however, limitations to collecting the data in this way. Defra could not follow up with survey respondents, for example, to further explore questions raised.

Although workers were provided with assurances around confidentiality, they depend on the scheme’s operators (who distributed the survey) to access work and may therefore have been reluctant to provide negative feedback (or respond to the survey at all) due to a lack of confidence about who can view their responses. It should be noted, however, that the operators do not have access to the raw survey data.

There is also a risk of self-selection bias as participants were free to choose whether to respond to the survey or not. Hence, there is a possibility of overrepresentation of subgroups that had a particularly positive or negative experience working in the UK.

Language barriers can be another limitation, bringing a risk that information is lost in the translation of survey questions into other languages or responses into English. Across the survey, 95.5% of respondents answered a translated version of the survey (94.8% in 2023). The Russian survey translation was the most popular translation used by respondents (66.4%). Only 4.5% of respondents answered the English language version of the survey. A professional translator was used to convert to English a number of the non-English responses from the free text options in questions 24b, 25b(i) and 30 prior to their analysis. They translated responses from 7 languages including Uzbek and Kazakh, while other languages were translated using translation software.

It is possible that the detail sought in the complaints and transfers questions in 2024 may have put off some respondents from answering these questions, or misinterpreting what was being asked.

Finally, due to the way in which the survey is conducted, and its confidential nature, there is a risk that respondents submitted multiple responses to this survey. There are no measures in place to prevent respondents mistakenly submitting multiple responses. The data cleaning process attempts to identify and remove duplicate responses, however it cannot be guaranteed that all duplicates are removed from the dataset.

The survey is designed to capture the experience of seasonal workers on the visa route. Experiences of other seasonal workers (for example, EU workers with Settled or Pre-Settled Status or Ukrainians with extended visas) on farm are not included in this survey.

2.2 Comparisons with previous surveys

This report will make some comparisons with the findings from the 2022 and 2023 Survey of Workers as there were similarities between the themes explored in 2022, 2023 and 2024. When comparison between 2022, 2023 and 2024 responses is undertaken in this report, it is noted where the questions differed between the iterations of the survey. Comparison with the results from pre-2022 surveys would be less meaningful due to changes to the Seasonal Worker visa route since then, and a re-design of the 2022 survey.

3. Respondent characteristics

The survey collected basic demographic information from respondents, including nationality, age, and gender.

3.1 Nationality of survey respondents

Table 2 demonstrates that the largest proportion of survey respondents (91.5%) were from four Central Asian countries (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan). In total they provided 12,825 out of 14,012 responses after data cleansing.

Table 2: Nationality of 2024 survey respondents

| Nationality | Number of respondents | Proportion of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Kyrgyz | 4,879 | 34.8% |

| Uzbek | 3,696 | 26.4% |

| Kazakh | 2,349 | 16.8% |

| Tajik | 1,901 | 13.6% |

| Moldovan | 377 | 2.7% |

| Ukrainian | 201 | 1.4% |

| South African | 132 | 0.9% |

| Kenyan | 83 | 0.6% |

| Romanian | 83 | 0.6% |

| Bulgarian | 82 | 0.6% |

| Macedonian | 82 | 0.6% |

| Azerbaijani | 35 | 0.2% |

| Indonesian | 24 | 0.2% |

| All other | 88 | 0.6% |

| Total: | 14,012 | 100.0% |

3.2 Age of survey respondents

Most respondents to the survey were aged between 25 and 38 years (65.2% – see Table 3).

Table 3: Age group of 2024 survey respondents

| Age group | Number of respondents | Proportion of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 1,841 | 13.3% |

| 25-31 | 4,640 | 33.4% |

| 32-38 | 4,416 | 31.8% |

| 39+ | 2,979 | 21.5% |

| Total: | 13,876 | 100.0% |

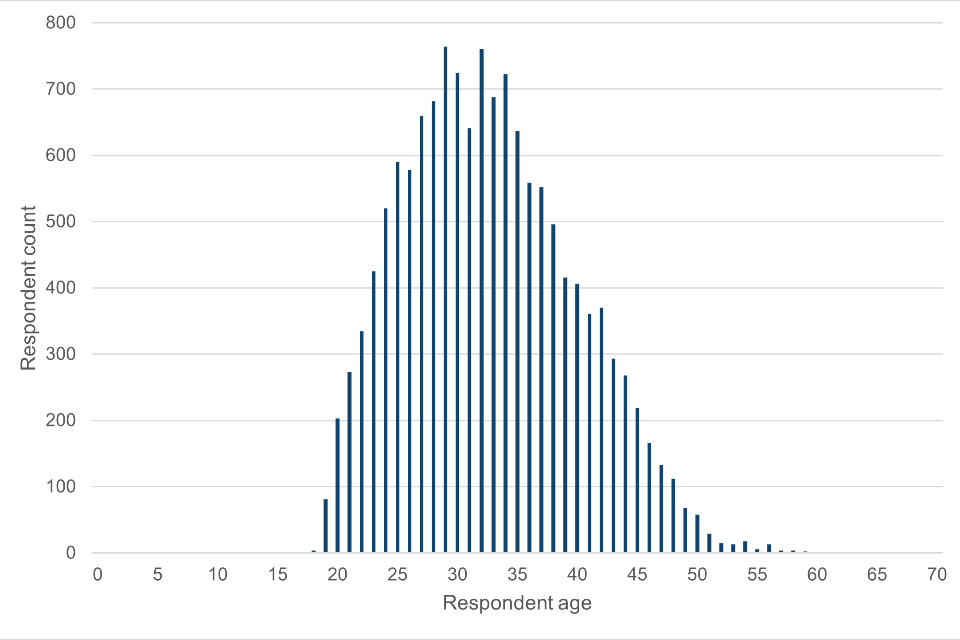

Figure 2: Distribution of respondent age in the 2024 Survey of Workers

Figure 2: Distribution of respondent age in the 2024 Survey of Workers

| Distribution of respondent age in the 2024 Survey of Workers | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 18 | 4 | 0.0% |

| 19 | 81 | 0.6% |

| 20 | 203 | 1.5% |

| 21 | 273 | 2.0% |

| 22 | 335 | 2.4% |

| 23 | 425 | 3.1% |

| 24 | 520 | 3.7% |

| 25 | 590 | 4.3% |

| 26 | 578 | 4.2% |

| 27 | 660 | 4.8% |

| 28 | 682 | 4.9% |

| 29 | 764 | 5.5% |

| 30 | 725 | 5.2% |

| 31 | 641 | 4.6% |

| 32 | 761 | 5.5% |

| 33 | 688 | 5.0% |

| 34 | 723 | 5.2% |

| 35 | 637 | 4.6% |

| 36 | 559 | 4.0% |

| 37 | 552 | 4.0% |

| 38 | 496 | 3.6% |

| 39 | 416 | 3.0% |

| 40 | 406 | 2.9% |

| 41 | 361 | 2.6% |

| 42 | 370 | 2.7% |

| 43 | 293 | 2.1% |

| 44 | 268 | 1.9% |

| 45 | 219 | 1.6% |

| 46 | 166 | 1.2% |

| 47 | 133 | 1.0% |

| 48 | 112 | 0.8% |

| 49 | 68 | 0.5% |

| 50 | 58 | 0.4% |

| 51 | 29 | 0.2% |

| 52 | 15 | 0.1% |

| 53 | 13 | 0.1% |

| 54 | 18 | 0.1% |

| 55 | 6 | 0.0% |

| 56 | 13 | 0.1% |

| 57 | 4 | 0.0% |

| 58 | 4 | 0.0% |

| 59 | 2 | 0.0% |

| 60 | 1 | 0.0% |

| 61 | 1 | 0.0% |

| 62 | 1 | 0.0% |

| 63 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 64 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 65 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 66 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 67 | 1 | 0.0% |

| 68 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 69 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 70 | 1 | 0.0% |

| Total | 13,876 | 100.0% |

Figure 2 shows that the most commonly stated age was 29. Persons aged from 24 to 37 each contained over 500 responses (accounting for 65.4% of respondents). The average (mean) age of survey respondents was 33.

The average age of respondents has increased across the four surveys with reductions in the younger age group and increases in the older age group over the past four years (see Table 4).

Table 4: Age groups of survey respondents in 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024

| Age group | 2021 proportion | 2022 proportion | 2023 proportion | 2024 proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 24 | 23.1% | 16.6% | 16.0% | 13.3% |

| 25 to 31 | 43.3% | 39.7% | 36.4% | 33.4% |

| 32 to 38 | 21.6% | 27.1% | 28.4% | 31.8% |

| more than 39 | 12.1% | 16.6% | 19.2% | 21.5% |

| Total: | 746 | 4,210 | 13,507 | 13,876 |

3.3 Gender of survey respondents

Most respondents to the 2024 seasonal workers survey stated they were male (79.1%), while (20.8%) stated they were female (see Table 5).

Table 5: Gender of 2024 survey respondents

| Gender | Number of respondents | Proportion of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 10,987 | 79.1% |

| Female | 2,897 | 20.8% |

| Other | 0 | 0.0% |

| Prefer not to say | 11 | 0.1% |

| Total | 13,895 | 100.0% |

There was a slight increase in the proportion of female respondents over the last four years (see Table 6).

Table 6: Gender of survey respondents in 2022, 2023 and 2024 (respondents to the survey in 2021 were not asked their gender)

| Gender | 2022 proportion | 2023 proportion | 2024 proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 84.9% | 80.9% | 79.1% |

| Female | 14.9% | 18.9% | 20.8% |

| Other | less than 0.1% | less than 0.1% | 0.0% |

| Prefer not to say | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Total: | 4,225 | 13,554 | 13,895 |

3.4 Country of work of survey respondents

Respondents were given the opportunity to state where in the UK they primarily worked while on the Seasonal Worker visa route (see Table 7).

Table 7: Respondents by country in which they primarily worked

| Country respondent mainly worked in | Number of respondents | Proportion of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| England | 11,715 | 87.3% |

| Scotland | 1,319 | 9.8% |

| Northern Ireland | 327 | 2.4% |

| Wales | 64 | 0.5% |

| Total: | 13,425 | 100.0% |

Given far more respondents worked in England than elsewhere in the UK, respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales were analysed as a single group in comparison to respondents from England.

Section B – Main findings

When reading this section please bear in mind the following:

-

As set out in Section 2.2, some of the results from this section are directly comparable to the 2022 and 2023 iterations of the Survey of Workers but not to reports prior to 2022.

-

Considering overall frequencies and proportions, each theme in this section will consider variations in responses by nationality. The nationality groups analysed in this section are Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, representing 91.5% of survey respondents. The remaining 1,187 respondents (8.5% of all responses) are grouped into an ‘other’ nationality category, of which the majority came from Eastern Europe, Balkan nations, and Ukraine, but also from further afield, including Kenya and South Africa.

-

Variations between respondents of different ages and genders, and variations between respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales as opposed to England, are only commented upon where there were noticeable variations.

4. Recruitment and pre-arrival costs

To investigate the costs workers are incurring, survey respondents were asked how much they paid on things related to their seasonal work before arriving in the UK and how they funded these costs.

To see if workers were clear on what their working and living experience would be like in the UK, the survey asked about the accuracy of the information provided during recruitment on topics including accommodation, working hours, contract length, pay rates, and potential deductions to pay.

4.1 Costs incurred before arriving in the UK

4.1.1 Type of costs incurred

A wide range of options were provided in the survey’s multiple-choice selection (see Figure 3). Visa fees were the cost most frequently selected by respondents at 94.4%, followed by travel costs at 56.7%. The expectation is, however, that almost all seasonal workers will pay for their travel to the UK.

All remaining cost options were selected much less frequently by respondents, with the next most often selected being ‘labour/migration ministry fees’ at 13.3% (an increase on 2023’s 7.6% figure), followed by ‘medical fees’ at 5.1%.

Figure 3: Type of costs incurred before arrival in the UK (respondents were asked to select all that apply)

| Type of costs incurred before arrival in the UK | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment agent/job-finding fee | 217 | 1.7% |

| Training fees | 151 | 1.2% |

| Medical fees | 661 | 5.1% |

| Interview fees | 100 | 0.8% |

| Labour/Migration Ministry fees | 1,744 | 13.3% |

| Uniform cost | 279 | 2.1% |

| Visa | 12,333 | 94.4% |

| Travel to UK | 7,409 | 56.7% |

| Other | 781 | 6.0% |

Variation by nationality

A greater proportion of Uzbek respondents (43.1%), compared to other nationalities, reported having paid fees to ‘labour/migration ministries’ (see Annex A Table A1). Kazakh respondents were the next highest proportion at only 4.3%, in comparison with the overall proportion of 13.3% among respondents to that question. A greater proportion of ‘other’ nationalities and Uzbek respondents stated they paid medical fees, at 13.3% and 11.3% compared with the overall proportion of 5.1% among respondents to that question.

4.1.2 Amount paid in up-front costs

Almost all respondents reported paying less than £1,000 in up-front costs before arriving in the UK (92.1%), with 53.2% of all respondents stating they paid £499 or less (see Figure 4). However, 1.3% of respondents reported they paid over £3,000. These responses were examined in more detail, but there is no clear explanation for these unusual reports of high expenditure.

Figure 4: Amount paid by workers before arrival in the UK

| Amount paid by workers before arrival in the UK | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| £1 to £499 | 6,902 | 53.2% |

| £500 to £999 | 5,049 | 38.9% |

| £1,000 to £2,999 | 858 | 6.6% |

| £3,000 to £4,999 | 45 | 0.3% |

| £5,000 to £9,999 | 51 | 0.4% |

| More than £10,000 | 74 | 0.6% |

| Total | 12,979 | 100.0% |

Variation by nationality

A greater proportion of Tajik respondents reported paying £499 or less, with 59.9% of their cohort selecting that option compared with the overall proportion of 53.2% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A2).

4.2 Funding pre-arrival costs

The survey asked respondents how they funded their pre-arrival costs to understand the prevalence of workers entering debt before arriving in the UK.

Most respondents stated they paid for their trip through their savings (59.1%). A further 34.6% of respondents stated they borrowed the money, mostly from family or friends (see Table 8).

Table 8: How respondents funded their pre-arrival costs

| Funded by | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Savings | 7,508 | 59.1% |

| Loan (family or friends) | 3,483 | 27.4% |

| Formal loan, for example banks | 910 | 7.2% |

| Informal loan, for example money lenders | 249 | 2.0% |

| Recruitment company | 180 | 1.4% |

| Selling possessions | 379 | 3.0% |

| Total | 12,709 | 100.0% |

Variation by nationality

A greater proportion of Kazakh respondents than those of other nationalities stated they covered their pre-arrival costs using a formal loan (22.0% compared with the overall proportion of 7.2% among respondents to that question).

In comparison, Uzbek respondents reported more frequently than other groups that they used savings to fund their recruitment and travel costs (66.0% compared with the overall proportion of 59.1% among respondents to that question). See Annex A Table A3 for full breakdown by nationality.

4.3 Accuracy of information provided during the recruitment process

Most respondents stated the information provided during recruitment was accurate (see Figure 5). The greatest proportion of respondents indicated the information on cost of accommodation was accurate (88.2%), while information on working hours was least frequently stated as accurate (79.2%). There were modest increases in the proportion of respondents stating information was accurate between 2023 and 2024 for each topic (accommodation, working hours etc). See Figures 5 and 6.

When given the opportunity to feed back on anything else about their experience, some respondents further elaborated on the information provided. For example, one respondent wrote:

“There was no problem, the management was very nice, everything was explained clearly, everything was understandable, I was pleased to work on the farm with nice people.”

Figure 5: Accuracy of information provided during recruitment (2024)

| Accuracy of information provided during recruitment (2024) | Accurate | Not accurate | Somewhat accurate | Unsure | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation Condition | 11,275 | 208 | 1637 | 48 | 13,168 |

| Accommodation Cost | 11,617 | 164 | 1,332 | 55 | 13,168 |

| Working Hours | 10,433 | 521 | 2,140 | 74 | 13,168 |

| Contract Length | 11,282 | 445 | 1,366 | 75 | 13,168 |

| Potential deductions to pay | 10,996 | 336 | 1,663 | 173 | 13,168 |

| Pay rates (including if piece rate, how this would be calculated) | 11,309 | 278 | 1,453 | 128 | 13,168 |

| Holiday pay or sick pay entitlements (or both) | 11,014 | 444 | 1,434 | 276 | 13,168 |

Figure 6: Accuracy of information provided, 2023 to 2024 comparison

| Accuracy of information provided, 2023 to 2024 comparison | 2024 Accurate (%) | 2023 Accurate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Accommodation Condition | 85.6% | 80.6% |

| Accommodation Cost | 88.2% | 84.8% |

| Working Hours | 79.2% | 73.3% |

| Contract Length | 85.7% | 83.3% |

| Potential deductions to pay | 83.5% | 78.9% |

| Pay rates (including if piece rate, how this would be calculated) | 85.9% | 81.7% |

| Holiday pay/sick pay entitlements | 83.6% | 79.9% |

Variation by nationality

For most topics, Tajik and Uzbek respondents answered more positively when asked about the accuracy of the information provided to them during recruitment (see Annex A Table A4).

5. Contracts, pay and hours worked, and duration of work

It is important that pay and working conditions are fully understood by migrant workers. The survey asked if contracts were available to them in their first language and, if not, in a language they were fluent in.

To check if migrant workers were paid fairly the survey asked if respondents were paid for all the work they did, and if they received the minimum number of hours of pay per week (32 hours averaged over their pay period). Workers often want to maximise their earning potential, so the survey asked how long they worked in the UK and how long after arriving in the UK they started work. New to the 2024 survey, respondents were also asked about the accuracy of information provided on their payslips.

5.1 Contracts

Most respondents were provided with a contract in their first language (75.2%, or 9,888 respondents – see Table 9), with this proportion increasing from 2023 (62.6% of respondents). Of those 3,266 respondents who stated they were not provided a contract in their first language, 85.0% (2,771 respondents) stated their contract was provided in a language they were fluent in, while the remaining 15.0% (488 respondents) said they did not receive their contract in a language they were fluent in (see Table 10).

Therefore, 3.7% (or 488 out of the 13,154 who answered the initial contract language question) stated they did not receive a contract in either their first language or a language they were fluent in.

Table 9: Contract provided in respondent’s first language

| Contract provided in first language | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 9,888 | 75.2% |

| No | 3,266 | 24.8% |

| Total: | 13,154 | 100.0% |

Table 10: Contract provided in a language the respondent was fluent in

(respondents were asked this question if they answered that their contract was not provided in their first language)

| Contract provided in language fluent in | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 2,771 | 85.0% |

| No | 488 | 15.0% |

| Total: | 3,259 | 100.0% |

5.2 Pay and hours worked

Almost all respondents (96.7%) stated they worked on average for 32 or more hours per week, with 49.6% of respondents stating they worked between 32 to 40 hours, and 35.4% between 41 to 50 hours a week. A smaller proportion (11.6%) stated they worked on average for over 50 hours a week (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Average number of hours worked in a week

| Average number of hours worked in a week | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Under 25 | 62 | 0.5% |

| 25 to 31 | 356 | 2.8% |

| 32 to 40 | 6,270 | 49.6% |

| 41 to 50 | 4,478 | 35.4% |

| 51 to 60 | 1,232 | 9.7% |

| Over 60 | 244 | 1.9% |

| Total | 12,642 | 100.0% |

This year’s survey showed an increase in respondents stating they were paid for all their work (including associated time such as setting up and cleaning), from 87.9% in 2023 to 96.2%.

Respondents who answered that they were not paid for all of the work they did (3.8%) were given the opportunity to explain in more detail what they were not paid for. Analysis of the free text responses showed a range of reasons, the most common being ‘overtime’ and ‘time spent cleaning and garbage collecting’.

When given the opportunity to feed back on anything else about their experience, some respondents further elaborated on their working hours and pay. For example, one respondent wrote:

“According to the contract, the farm was supposed to provide work for 32 hours a week. But in fact, when we worked less than 32 hours, the farm paid for the missing hours from our vacation money.”

Another respondent wrote:

“I like working on the farm. The inside of the greenhouse is warm and dry. We don’t carry heavy loads. We break every 2 hours. The salaries and bonuses are good.”

Variation by country of work in the UK

Survey results indicate that respondents in England more frequently reported working more hours (more than 41 on average per week) than those working in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, at 49.0% compared with 31.6%. Respondents from these countries more frequently reported working between 32 and 40 hours per week (65.0%) compared with 47.7% of respondents who worked in England (see Annex D Table D1 for more detail).

5.3 Length of time in UK before work started

The vast majority of respondents (85.5%) were in the UK for 3 days or less before starting work, with 11.0% waiting for between 4 and 7 days between arriving to the UK and starting work (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Length of time respondents spent in UK before starting work

| Length of time respondents spent in UK before starting work | Count: | Percentage: |

|---|---|---|

| 0-3 days | 10,748 | 85.5% |

| 4-7 days | 1,378 | 11.0% |

| Over 1 week but less than 2 weeks | 289 | 2.3% |

| 2 weeks or more but less than 3 weeks | 71 | 0.6% |

| 3 weeks or more but less than 4 weeks | 28 | 0.2% |

| Over 4 weeks | 59 | 0.5% |

| Total: | 12,573 | 100.0% |

Variation by nationality

A higher proportion of respondents from Tajikistan than other analysed nationality groups reported they had started work in 0 to 3 days after arriving in the UK, at 92.7% of their respondents compared with the overall proportion of 85.5% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A7).

5.4 Duration of work

Almost all respondents to the survey (91.4%) stated they worked in the UK for 4 months or longer, the majority of those stating they worked for 5 months or longer (see Figure 9). There has been an encouraging increase in the proportion of respondents answering they worked for 5 months or longer in recent surveys, increasing from 60.7% in 2022, to 69.5% in 2023 and now 74.7% in 2024.

For most workers, it is preferable to spend as long as their visa allows working in the UK, as this helps improve their earning potential while on the Seasonal Worker visa route. For example, one respondent noted in their free text answer, when asked whether there was anything else about their experience they would like to share, that they wanted the seasonal visa to last longer:

“It is probably very important that the terms of the seasonal visa are extended for a longer period, at least from a year to 2 to 3 years. This would give you the opportunity to earn money and benefit both yourself and the employer.”

Figure 9: Duration of work in the UK

| Duration of work in the UK | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 2 months | 150 | 1.2% |

| 2 months or more, but less than 3 months | 252 | 2.0% |

| 3 months or more, but less than 4 months | 683 | 5.4% |

| 4 months or more, but less than 5 months | 2,111 | 16.7% |

| 5 months or longer | 9,421 | 74.7% |

| Total | 12,617 | 100.0% |

The survey showed, however, that 21.3% of respondents stated they worked for less than their contract specified (see Table 11).

Table 11: Worked for less time than contract specified

| Work for less than contract specified | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 2,682 | 21.3% |

| No | 9,410 | 74.6% |

| Unsure | 514 | 4.1% |

| Total | 12,606 | 100.0% |

Variation by nationality

A greater proportion of respondents from ‘other’ nationalities reported that they had worked for less than 2 months (4.1% compared with the overall proportion of 1.2% among respondents to that question) (see Annex A Table A8).

Tajik respondents were less likely to report not working for the length of their contract (15.2% compared to the overall proportion of 21.3% among respondents to that question) (see Annex Table A9).

5.5 Payslips

Almost all respondents (98.0%) stated that their payslip clearly explained how their pay was calculated (including the hours they worked, bonus pay, deductions and what the deductions were for).

Respondents who stated their payslip did not clearly explain how their pay was calculated were asked what was not clearly explained. ‘Hours’ (83 of 245 responses, or 33.9%) and ‘bonus’ (62 responses, or 25.3%) received the greatest proportions of responses (see Table 12).

Table 12: What respondents stated their payslips did not clearly explain

| What payslips did not clearly explain | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Hours | 83 | 33.9% |

| Pay rate | 35 | 14.3% |

| Bonus | 62 | 25.3% |

| Deductions for accommodation | 24 | 9.8% |

| Tax or National Insurance (or both) | 41 | 16.7% |

| Total | 245 | 100.0% |

Variation by age group

There were different response rates between different age groups when asked what was not clearly explained in their payslip. From younger to older age groups, there was a decreasing proportion of respondents stating the payslip did not clearly explain tax or National Insurance (or both), ranging from 25.8% for those aged 18 to 24 down to 9.1% of those aged 39 and over (see Annex C Table C1).

Variation by gender

Variation was also evident in the responses between male and female respondents. A greater proportion of male respondents stated their payslip did not clearly explain tax or National Insurance, or both (18.9% compared with 8.3% of females) (see Annex B Table B1).

Variation by country of work in the UK

Survey results show that a higher proportion of respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales stated their payslip did not clearly explain their hours, at 43.8% of respondents compared with 29.9% of respondents who worked in England (see Annex D Table D2).

6. Costs in the UK and on-farm experiences

To check migrant workers are not paying undue costs in the UK that unfairly reduce their take-home earnings, the survey asked respondents what they paid for after arriving in the UK. This included a range of potential costs, including travel, tax, accommodation, utility bills, other living essentials and work-related costs.

The survey also asked respondents to describe their experience working in the UK regarding a number of factors, including their accommodation, their supervisors/farm managers, and their access to healthcare.

6.1 Costs incurred after arriving in the UK

Apart from food, the costs respondents most frequently reported paying in the UK were accommodation (42.3%) and travel to the farm when arriving in the UK or to a new farm when transferring farm (42.3%) (see Table 13).

Table 13: Costs after arrival in the UK (respondents were asked to select all that apply, therefore total percentages may not equal 100%)

| Post-arrival cost | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Accommodation cost | 5,246 | 42.3% |

| Travel costs within UK | 4,579 | 37.0% |

| Travel costs to get to farm when arriving in UK/to a new farm | 5,238 | 42.3% |

| Personal protective equipment (equipment your employer says you must wear or use for your safety) | 878 | 7.1% |

| Training fees | 52 | 0.4% |

| Medical fees | 484 | 3.9% |

| Living essentials for example bedding, cooking utensils | 3,416 | 27.6% |

| Utilities, for example electric, gas, water | 2,266 | 18.3% |

| Laundry | 2,002 | 16.2% |

| WiFi | 1,082 | 8.7% |

| Food | 5,410 | 43.7% |

| Tax or National Insurance (or both) | 3,670 | 29.6% |

| Other | 1,119 | 9.0% |

When given the opportunity to provide feedback on anything else about their experience, some respondents further elaborated on the additional costs they incurred for things like utilities, travel and medical care. For example, one respondent wrote:

“It would be nice if the farm would pay for the daily rout [sic.] to the farm or hire transportation. The houses are very cold in the winter and gas is very expensive.”

Another respondent wrote:

“I want to inform you, I had an accident on the farm, I broke my leg, the hospital provided me with the best possible support, but in the end, I received an invoice of 600 INR, which I have to pay, and why me? Am I not insured?”

Variation by nationality

Responses varied between nationalities for the different post-arrival costs. For example, respondents from the ‘other’ nationality group reported more frequently paying for living essentials including bedding and cooking utensils (35.9%) compared with the overall proportion of 27.6% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A11).

Variation by country of work in the UK

Survey results show that a higher proportion of respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales reported having paid for utilities such as electric, gas and water than respondents who worked in England, at 28.6% compared with 16.4%. A greater proportion also reported paying for travel within the UK, at 45.7% compared with 35.7% of respondents who worked in England.

6.2 On-farm experience

The response to questions regarding on-farm experience was generally positive, with between 84.0% and 95.2% of respondents answering that they were ‘happy’ with the listed topics, including accommodation, hours available, and pay (see Figure 10).

The least frequently selected options for the ‘happy’ marking were ‘access to healthcare’, at 84.0% and ‘ability to raise complaints or complaints procedure’ at 84.2%.

In comparison, far fewer respondents stated they were ‘unhappy’ with the listed conditions, ranging from 1.5% of respondents answering they were ‘unhappy’ with ‘safety’ to 5.6% of respondents for ‘ability to raise complaints or complaints procedure’.

Figure 10: Satisfaction across a range of farm conditions

| Satisfaction across a range of farm conditions | Happy | Unhappy | Unsure | Prefer not to say | Total: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation | 93.4% | 3.3% | 2.0% | 1.3% | 100.0% |

| Hours available | 91.4% | 4.2% | 2.9% | 1.5% | 100.0% |

| Pay | 95.0% | 2.1% | 1.7% | 1.1% | 100.0% |

| Information provided | 93.6% | 3.1% | 2.2% | 1.1% | 100.0% |

| Travel to or from farm at the start and end of contract | 90.6% | 4.2% | 3.1% | 2.1% | 100.0% |

| Protective equipment provided | 90.0% | 5.0% | 3.4% | 1.6% | 100.0% |

| Ability to raise complaints or complaints procedure (or both) | 84.2% | 5.6% | 5.6% | 4.6% | 100.0% |

| Farm supervisors and managers | 88.7% | 5.4% | 3.4% | 2.6% | 100.0% |

| Operator support | 91.8% | 3.6% | 3.1% | 1.5% | 100.0% |

| Ability to leave farm for leisure | 92.1% | 2.4% | 2.7% | 2.8% | 100.0% |

| Access to healthcare | 84.0% | 5.1% | 7.6% | 3.3% | 100.0% |

| Safety | 95.2% | 1.5% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 100.0% |

When given the opportunity to provide feedback on anything else about their experience, some respondents elaborated on the state of their accommodation. For example:

“The caravans do not have very good living conditions. It is very cramped, 6 people live in the caravan and the rooms are very small”

“The accommodation and premises in which we lived do not meet sanitary standards, there is mould and leaky windows everywhere, we took money for gas and electricity in cash unofficially, managers and supervisors do not care about the staff.”

Other respondents stated:

“Living conditions are excellent, the attitude of the bosses is respectful, the work process is built competently and tactfully, recreation areas for every taste, I am very pleased with this farm.”

“Thanks to all the employees of the agency for the work provided to us in 2024. I liked everything in the work, the team was excellent, the supervisors were conscientious and friendly.”

Variations by nationality

Respondents from the ‘other’ nationality category less frequently reported that they were ‘happy’ across the range of conditions on farm compared with Central Asian nationals. For example, 82.0% of ‘other’ nationalities answered that they were happy with their personal protective equipment, compared with the overall proportion of 90.0% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A12).

7. Complaints, transfers, and access to health care

If a seasonal worker is unhappy with their employment, or life on farm, it is important they can access a complaints’ process they trust. The survey asked respondents if they knew how to raise a complaint, whether they had raised a formal complaint and, if they had, who they raised it with, what the grievance was about and if it was followed up. The survey also asked respondents who had a grievance but did not raise a formal complaint why they did not do so.

The ability to transfer to another farm is an important option for seasonal workers. The survey asked respondents a number of questions on this topic, such as if they had requested a transfer and why, if their transfer request was accepted and they moved, and if not, why they were not transferred.

The survey also addressed access to healthcare (if required), with questions including whether appropriate treatment was received for any sickness or injury, and if respondents were well supported by their farm and scheme operator.

7.1 Complaints

Slightly more than eight out of ten respondents (81.8% of those who answered this question) stated they knew how to raise a complaint if they were unhappy with their employment or life on the farm. This is an increase from 78.3% in 2023 and 70.7% in 2022, though it should be noted the question in 2022 asked whether they were unhappy with their employment only.

Respondents were also asked whether they had a grievance (other than a transfer request) while working in the UK and if they raised a complaint as a result. Most respondents answered they did not have a grievance (see Table 14).

Table 14: Whether the respondent experienced a grievance

| Whether the respondent experienced a grievance | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, and raised a formal complaint | 245 | 2.0% |

| Yes, had a grievance but did not raise a formal complaint | 1,364 | 10.9% |

| No | 10,915 | 87.2% |

| Total | 12,524 | 100.0% |

Respondents most frequently reported raising a complaint to their supervisor (34.3%, or 81 of 236 responses) or a farm manager (33.5%, or 79 of 236 responses), with all other options receiving a far smaller share of the responses (see Table 15). Only 2 respondents stated they reported their complaint to an official government authority, such as UK Visa & Immigration (UKVI).

Table 15: Who workers raised complaints with

| Complaint raised with | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Supervisor | 81 | 34.3% |

| Farm manager | 79 | 33.5% |

| Operator | 18 | 7.6% |

| A worker support organisation (not the farm or operator) | 12 | 5.1% |

| Embassy or consulate | 0 | 0.0% |

| Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) – (UK government) | 1 | 0.4% |

| UKVI (Home Office, UK government) | 1 | 0.4% |

| Other | 44 | 18.6% |

| Total | 236 | 100.0% |

The greatest proportions of complaints were associated with working, rather than living, conditions. Apart from the ‘other’ category, the most common reason stated by respondents were ‘supervisor or manager’ (14.4%, or 27 responses) closely followed by ‘not enough hours’ (13.4%, or 25 responses). This was followed by ‘working conditions’ and ‘accommodation’ (both with 11.8%, or 22 responses) (see Table 16).

Table 16: Categories and numbers of complaints raised

| Nature of complaint | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Accommodation | 22 | 11.8% |

| Discrimination | 17 | 9.1% |

| Racism | 13 | 7.0% |

| Not enough hours | 25 | 13.4% |

| Pay | 7 | 3.7% |

| Supervisor or manager | 27 | 14.4% |

| Transfers | 8 | 4.3% |

| Working conditions | 22 | 11.8% |

| Other | 46 | 24.6% |

| Total | 187 | 100.0% |

When asked whether their complaint was followed up, 37.0% of respondents (88 responses) answered it was not. Answers to this question show a slightly improving picture over the last few years, with 55.2% (85 respondents out of 154 total responses to the question) in 2022, 58.9% (212 out of 360 responses) in 2023 and 63.0% (150 out of a total 238 responses) in 2024 stating their complaint was followed up.

Those who stated they had a grievance but did not raise a formal complaint (10.9% or 1,364 responses) were asked why they did not do so. The most frequently reported answers were ‘did not believe action would be taken’ at 31.3% (356 responses) and ‘afraid I would lose my job’ at 22.8% (260 responses), accounting for over half of all respondents to that question (see Table 17).

Table 17: Reason respondents who had a grievance did not raise a formal complaint

| Reason complaint was not raised | Responses | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Concerned my employer would find out | 87 | 7.6% |

| Did not know who was responsible for the particular complaint | 167 | 14.7% |

| Afraid I would lose my job | 260 | 22.8% |

| Did not believe action would be taken | 356 | 31.3% |

| Was worried it would have an impact on my right to stay in the UK | 238 | 20.9% |

| Transferred off farm where grievance occurred | 31 | 2.7% |

| Total | 1,139 | 100.0% |

When given the opportunity to feedback on anything else about their experience, some respondents further elaborated on their ability to raise a complaint. For example, one respondent wrote:

“I am unhappy with poor treatment of supervisors and managers. Employer doesn’t want to listen complaints. Farm employees felt discrimination. But they don’t know how to raise complaints and some employees are afraid of losing the placement that’s why they will not raise complaints. Employers should be respectful for all employees but unfortunately, they don’t. We would like to work in UK farms. We came here to help British farmers.”

Variation by nationality

Fewer Tajik respondents stated they raised a complaint with a farm manager, at 16.0% compared with the overall proportion of 33.5% among respondents to that question. Correspondingly, a greater proportion of Tajik respondents answered they had complained to an ‘other’ source, with 36.0% of their response group selecting that answer, compared with the overall proportion of 18.6% among respondents to that question.

There was also variation in the stated nature of their complaint, for example, a greater proportion of Kazakhs stated their complaint was due to a lack of hours (28.6%) compared with the overall proportion of 13.4% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A13).

Additionally, only 36.4% of Kazakh respondents reported that their complaint was followed up, compared with the overall proportion of 63.0% among respondents to that question.

In terms of not complaining when they had a grievance, Uzbeks more frequently reported that they were worried doing so would have an impact on their right to stay in the UK, at 26.8% reporting this compared with the overall proportion of 20.9% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A14).

Variation by age group

There was a slight variation between age groups regarding who respondents complained to. For example, 18- to 24-year-olds were more likely than other age groups to raise their complaint to either a worker support organisation (11.8% of their cohort compared to the overall proportion of 5.1% among respondents to that question) or their operator (14.7% of their cohort compared to the overall proportion of 7.6% among respondents to that question).

Respondents in the 18- to 24-year-old group also reported more frequently that the nature of their complaint was racism, with 22.2% (6 responses out of a total of 27 from their age group to this question) stating this, compared with only 5.1% (3 responses) of 25- to 31-year-olds, 4.7% (3 responses) of 32- to 38-year-olds, and 2.7% (1 response) of respondents aged 39 and over (with the overall proportion being 7.0% among respondents to that question).

In comparison, a greater proportion of respondents in the 39-year-old and above category stated their complaint was about discrimination (16.2% or 6 responses compared with the overall proportion of 9.1% among respondents to that question, a total of 17 responses) and reported less frequently than other age groups that it was due to their supervisor or manager (5.4% or 2 responses compared with the overall proportion of 14.4% among respondents to that question, a total of 27 responses) (see Annex C Table C2).

The 18- to 24-year-old group also reported least frequently that their complaint was followed-up, at 41.2% (14 respondents) compared with the overall proportion of 63.0% among respondents to that question (a total of 150 respondents). The greatest proportion that reported they did not raise their complaint because they were worried it would have an impact on their right to stay in the UK was also the 18- to 24-year-old age group (26.0%, or 34 responses in comparison with the overall proportion of 20.9% among respondents to that question, or 238 respondents) (see Annex C Table C3).

Variation by gender

Complaints by male respondents were more frequently related to not having enough hours of work compared with female respondents (15.2% or 22 responses compared with 7.1% or 3 responses). Additionally, only 59.7% (111 responses) of male respondents stated their complaint was followed up, compared with 75.0% (39 responses) of female respondents.

Variation by country of work in the UK

Respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales reported more frequently that they raised a complaint because they were not receiving enough hours of work (26.3% compared to 11.8%) or because of their working conditions (31.6% compared to 9.9%) than respondents who worked in England (see Annex D Table D3). Respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales also reported less frequently that their complaint was followed-up, at 47.6% compared with 64.4% of respondents who worked in England.

7.2 Transfers

Of the 19.3% of survey respondents who stated they requested a transfer to another farm during their time in the UK, 57.7% were transferred, 38.0% were not and 4.3% had their transfer granted but were unable to move.

The greatest proportion of respondents stated their reason for asking for a transfer was due to a lack of hours on their current farm (see Table 18). The next most frequently stated reason was to be with friends. These results, and the proportion of workers who answered them, are consistent with 2023 survey results.

Table 18: Reason respondents requested a transfer to another farm

| Reason for requesting a transfer | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Not enough hours on current farm | 929 | 38.5% |

| To be with friends | 535 | 22.2% |

| Better conditions on new farm | 213 | 8.8% |

| Poor treatment from supervisor or /others (or both) on current farm | 328 | 13.6% |

| Other | 409 | 16.9% |

| Total: | 2,414 | 100.0% |

Respondents who selected ‘other’ were given the opportunity to explain why they requested a transfer. Most respondents who provided further information stated they requested a transfer either due to the crop season, or their contract, ending. For example:

“The strawberry season was coming to an end, and the apple season was beginning. There were more hours of work.”

“Because my contract with the farm was expiring and I still had time before the end of the visa.”

A small number said it was due to a health reason or because of the working conditions. For example, respondents wrote:

“At our first job, we picked mushrooms. My husband turned out to be allergic to mushrooms.”

“Since we started working in March, it was very cold in the field, so I requested a transfer to a farm in greenhouse conditions.”

Responses on the topic of transfers saw a wide range of opinions about how well the process functions. For example, one respondent stated:

“I was just unlucky with the farm and the fact that I came out of season. Why didn’t I apply for a transfer, because I saw how others were refused, sometimes even in a rude form, and sent home. And many began to say that if you file a complaint or ask for a transfer, for example, then they will inform the farm about the force and they will fire you.”

While another respondent wrote:

“Everything is fine, I saw a lot of places. For 6 months, they gave me a transfer 4 times. I liked everything”

Table 19 shows that, of those who were refused a transfer, ‘no job available’ was by far the most frequently selected answer at 39.3% of respondents. Comparison between previous surveys is not reliable due to rephrasing of the question and options.

Table 19: Reason respondents’ transfer request was not fulfilled

| Reason why transfer was refused | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| No job available | 360 | 39.3% |

| No job available at the farm I wanted to go to | 120 | 13.1% |

| Required on current farm | 83 | 9.1% |

| Visa was about to expire | 16 | 1.7% |

| Additional training requirements made it impractical | 1 | 0.1% |

| Refused and no reason given | 131 | 14.3% |

| No response to the transfer request | 153 | 16.7% |

| Other | 53 | 5.8% |

| Total: | 917 | 100.0% |

Variation by nationality

Kazakh respondents reported more frequently than other analysed nationalities that they requested a transfer at 27.9% compared with the overall proportion of 19.3% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A15).

Reasons for requesting a transfer varied widely. For example, 29.4% of Tajik respondents stated they requested a transfer to be with friends, in comparison with the overall proportion of 22.2% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A16).

Variation by country of work in the UK

Respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales reported less frequently that they were granted a transfer compared with respondents who worked in England (45.9% compared with 59.4%) (see Annex D Table D4).

Respondents from the Devolved Countries reported more frequently that their transfer request was not fulfilled and they received no response to their request (23.0% compared with 14.8% for respondents working in England) (see Annex D Table D5).

7.3 Access to healthcare

A small proportion of respondents indicated that they required medical treatment due to sickness or injury while in the UK (6.4% or 798 respondents out of a total 12,505 responses to this question). Of those respondents who were sick or injured, 62.5% (or 498 respondents) received treatment. This represents a slight decline from the 2023 worker survey findings, where 67.1% of respondents (684 respondents) indicated they had received treatment.

Respondents who stated they did not receive treatment were asked why not. As over half the respondents did not choose any of the specific options presented (‘other’ received 51.5% of the responses), it is difficult to get a full picture of the obstacles facing workers in receiving treatment (see Table 20). From the information that was gathered, the most frequently chosen option was that the respondent could not travel to where they could seek treatment (19.4% or 58 responses).

Table 20: Reason respondents did not receive treatment for sickness or injury

| Reason for not receiving treatment | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| I was not able to travel to where I could seek treatment | 58 | 19.4% |

| I could not afford to take time off work | 23 | 7.7% |

| I was told I had to continue working | 23 | 7.7% |

| I was not able to register with a GP | 33 | 11.0% |

| I could not get an appointment | 8 | 2.7% |

| Other | 154 | 51.5% |

| Total: | 299 | 100.0% |

The majority of respondents (76.9%) indicated they were well supported in accessing and receiving treatment (see Table 21). This is a slight increase from 2023 where 69.8% stated they were well supported.

Table 21: Support in accessing and receiving treatment

| Respondents’ answer to whether they were supported in accessing and receiving treatment | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 613 | 76.9% |

| No, I was not well supported by the farm | 117 | 14.7% |

| No, I was not well supported by my visa sponsor | 7 | 0.9% |

| No, I was not well supported by the farm or my visa sponsor | 60 | 7.5% |

| Total: | 797 | 100.0% |

Variation by nationality

Though similar proportions of the analysed nationalities reported needing medical treatment during their time working in the UK, responses to other questions regarding treatment varied. For example, Tajik respondents reported most frequently that they had received treatment, at 76.2% compared with the overall proportion of 62.5% among respondents to that question.

There was also some variation in the proportion of nationalities reporting they did not receive medical treatment because they were not able to register with a GP. Kyrgyz respondents reported this most frequently at 16.7%, compared with only 4.8% of Kazakh respondents, the nationality that reported this least frequently. The overall proportion was 11.0% among respondents to that question (see Annex A Table A19).

In terms of assistance provided for accessing medical treatment, Kyrgyz respondents reported less frequently than other nationalities that they were well supported (66.7% compared with the overall proportion of 76.9% among respondents to that question) (see Annex A Table A20).

Variation by gender

Female respondents reported more frequently that they were supported in accessing and receiving treatment, at 83.2%, compared with 75.0% of the male respondents.

Variations by age group

The need for medical treatment due to sickness or injury while in the UK was broadly similar across all respondent age groups. However, 18- to 24-year-olds reported less frequently than other age groups that they received treatment (46.8% compared with the overall proportion of 62.5% among respondents to that question). They also reported more frequently that they were not supported by either their farm or their operator in accessing or receiving treatment (12.9% compared with the overall proportion of 7.5% among respondents to that question).

Variation by country of work in the UK

A greater proportion of respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales than those who worked in England reported that they did not receive treatment because they could not travel to where they could seek it (35.1% compared to 16.7%) or because they could not register with a GP (21.6% compared to 9.9%) (see Annex D Table D6).

Respondents who worked in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales also reported less frequently that they were well supported in accessing healthcare (63.2% compared with 79.2% of respondents who worked in England) (see Annex D Table D7).

8. Overall satisfaction

For the welfare of workers and for the business interests of UK farms, it is important to understand seasonal workers’ experiences living and working in the UK. It is vital that seasonal workers have a positive experience whilst in the UK and that they can recommend the UK as a good place to work when they return to their home country.

8.1 Overall experience whilst in the UK

Selecting from multiple choice options, more than nine out of ten respondents (94.2%) stated they would describe their experience working in the UK as either ‘extremely positive’ or ‘positive’. Only 2.0% (251 responses) stated their experience was ‘negative’ and 0.4% (52 responses) stated it was ‘extremely negative’ (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Description of experience working in the UK

| Description of experience working in the UK | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely positive | 6,045 | 47.3% |

| Positive | 5,990 | 46.9% |

| Neither positive or negative | 443 | 3.5% |

| Negative | 251 | 2.0% |

| Extremely negative | 52 | 0.4% |

| Total | 12,781 | 100.0% |

There has been a gradual improvement in this score over the years the survey has been running. In 2022, 85.9% of respondents stated that their overall experience of seasonal work in the UK was either ‘extremely positive’ or ‘positive’, increasing to 91.0% in 2023, then to 94.2% in 2024.

However, when given the opportunity to provide feedback on anything about their experience, some respondents described experiences of suffering discrimination or racism. For example:

“In many farms, the attitude of management towards workers from other countries is racist. Hidden racism was felt from European managers.”

“I would like to say that if the supervisors who work with the workers treated them well, they would all work even better. Some of them act like we’re slaves here.”

Other respondents were more positive about their experiences:

“In my experience, I liked working in the UK, I paid off my debts, I made my family happy, I liked the attitude of the employers, everyone is punctual, I liked the living conditions, I travelled while working in the UK, I saw new cities.”

8.2 Desire to return to the UK to work

Almost all respondents (12,099 responses, or 96.9% of all responses to this question) stated they would like to return to work on a UK farm again (see Figure 12).

1.5% (182 responses) of respondents stated they did not want to return to the UK to work on a farm. When given the opportunity to provide feedback on anything about their time in the UK, one respondent explained they did not believe the effort of getting to the UK was worth the job:

“Although not everything was that bad and I met so many great workers, but I think it’s not worth the effort. As I made somewhere around £6.500 in 6 months (after taxes, living costs, visa and travel cost). Totally not worth it to leave my family for half a year.”

Most respondents who provided additional feedback wrote positively about their time in the UK and their desire to return to work again in future, for example:

“I liked my work in the UK. I have made many friends on the farm, I am satisfied with working on the farm.”

“I like working on the farm. The inside of the greenhouse is warm and dry. We don’t carry heavy loads. We break every 2 hours. The salaries and bonuses are good.”

Figure 12: Desire to return to work on a UK farm

| Desire to return to work on a UK farm | Count: | Percentage: |

|---|---|---|

| I would like to work on a UK farm again | 12,099 | 96.9% |

| I do not want to work on a UK farm again | 113 | 0.9% |

| I have not decided whether I want to work on a UK farm again | 182 | 1.5% |

| Prefer not to say | 87 | 0.7% |

| Total: | 12,481 | 100.0% |

Section C – Discussion and conclusion

The annual Survey of Workers gives participants on the Seasonal Worker visa route the opportunity to share their experiences and reflections of working and living in the UK. Their feedback allows respondents to illustrate what is going well and where improvements could be considered.

The 2024 survey continues the positive findings from the 2023 survey, with the vast majority of workers who come to the UK through the visa route being satisfied with their living and working experience whilst here.

Activity is ongoing in Defra and across the UK government more widely to safeguard workers and improve their wellbeing during their recruitment to the Seasonal Worker visa route and whilst in the UK. The survey has, however, highlighted some areas where further investigation and consideration is warranted. For example, responses to this survey help to identify areas of concern down to farm and recruitment country level, which can facilitate focused corrective efforts.

These issues include payslips. Respondents were specifically asked about payslips for the first time in the 2024 Survey, therefore a comparison of results with past years is not possible. However, responses indicated that the information provided on payslips was not always clear: suggesting more could be done to ensure details about pay are accessible to workers.

Defra’s Seasonal Labour and Worker Welfare team are consulting operators and the Seasonal Workers Scheme Taskforce about how the payslip information can be made clearer for workers on the route. The Taskforce features a vital cross-section of organisations from across the visa route, including growers, NGOs and federation representatives, ensuring a range of opinions and solutions to issues such as payslips can be discussed and actioned appropriately.

Survey responses also indicated that transfers are an issue for respondents. For example, of the 19.3% of total respondents who requested a transfer, over a third (38.0%, 918 responses) were not transferred, with around a third of those (31.0%, 284 responses) receiving either no reason for not being transferred or no response to their request. This represents a small proportion of total respondents to the survey but suggests communications with workers on the subject of transfers could be improved.

Results from the survey also indicate workers don’t always feel comfortable or informed enough to raise a complaint, when they experience issues whilst living and working in the UK.

Defra has shared findings related to complaints with the operators and will work with them to ensure workers are provided with up-to-date information regarding their transfer request, that they feel empowered, supported, and well-informed in situations where they would like to raise a complaint, and that both the complaint and transfer processes work optimally for workers.

Access to medical services was another area where survey responses suggest improvement is needed. Though only a minority of respondents (6.4% of all responses, 798 responses) answered that they required medical treatment whilst working in the UK, of those only 62.5% (498 responses) stated that they received treatment. Equally concerning, almost one quarter (23.1%, 184 responses) of respondents who answered they needed medical treatment whilst in the UK stated that they were not well supported in accessing medical care.

The Seasonal Labour and Worker Welfare team will discuss this issue with worker representation organisations, including the Worker Support Centre (WSC), and operators and growers to understand the issues at play that result in some workers not feeling supported or able to access appropriate healthcare.