Reducing Parental Conflict programme 2018 to 2022: final evaluation report

Updated 6 January 2025

DWP research report no. 1040

A report of research carried out by IFF Research Ltd on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit the National Archives website.

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available at: Research at DWP

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published August 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-559-1

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary: Background and methodology

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) introduced the Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme to address parental conflict, because of the strength of evidence published prior to this programme linking parental conflict to negative outcomes for children. The original programme began in 2018 and was backed by £39m for the period up until March 2021. It was then extended with additional funding through to March 2022. After this, a further phase of funding for the programme was secured until up to 2025[footnote 1].

The aim of the 2018–22 programme was to encourage local authorities across England to integrate services and approaches which address parental conflict in their local provision for families. There was also an aim to build evidence on what works to reduce parental conflict and understand best practice in this area.

To understand the process, experience and effects of the programme, DWP commissioned an evaluation to contribute to the wider evidence base on what works for families to reduce parental conflict. This was to support local authorities and their partners in embedding the reducing parental conflict agenda into their mainstream services.

The evaluation began in December 2018. To date, three reports have been published; this fourth report focuses on several quantitative surveys with parents[footnote 2] and qualitative research with parents and local authorities conducted in 2022, which was the final year of the original programme. This report builds on previously published findings.

There were three core strands to the evaluation, corresponding to three main programme elements:

- intervention delivery: To assess how the provision of evidence-based interventions in 31 local authorities, clustered in 4 geographical areas, is implemented and delivered and the perceived effectiveness of the interventions in reducing parental conflict and improving child outcomes[footnote 3].

- training: To study whether and how the training of practitioners and relationship support professionals had influenced practice on the ground - focusing on the identification of parents in conflict, building the skills and confidence to work with, or refer, parents in conflict and the overall support available.

- local integration: To examine to what extent local authorities across England had integrated elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families, how and with what success.

Evaluation

This is the final report from the commissioned evaluation of the 2018–22 RPC programme. This report focuses primarily on the quantitative surveys with parents that ran between summer 2020 and summer 2022, as well as final qualitative research conducted in 2022. Throughout the report, there are references to previous published findings to provide the full picture.

The following evaluation elements are the primary focus of this report:

- a telephone survey with parents who completed an intervention (hereafter referred to as ‘completers’) conducted around 4 to 6 months after they took part, involving a total of 878 interviews conducted between August 2020 and August 2022.

- a further follow-up telephone survey with completers, conducted around 12 months after they completed in an intervention, involving a total of 374 interviews conducted between May 2021 and August 2022.

- a telephone survey with 192 parents who started but failed to complete an intervention conducted between July 2020 and August 2022.

- a telephone survey with 66 parents who were referred but failed to start an intervention conducted between December 2021 and June 2022.

- a final set of 30 qualitative interviews with completers that were conducted between 7th March and 8th April 2022.

- qualitative case studies across ten local authorities who received the Workforce Development Grant (WDG) and one non-bidding local authority, speaking to a total of 22 interviewees between May and June 2022.

Intervention delivery

The original programme involved testing 8 evidence-based interventions to address parental conflict in 31 local authorities, in four geographical areas (Contract Package Areas). For the purposes of the test, the interventions were rated as high intensity or moderate intensity, based on the typical cost and duration of support provided to parents. Some interventions were for separated parents, some were for intact couples and others for both family types. A key part of the evaluation was to understand the effects of participating in these interventions on parents and their children.

Intervention delivery findings

This section draws on survey findings from parents who completed an intervention, those who started but did not complete an intervention and those who failed to start an intervention, despite being referred. These findings are supplemented with 30 qualitative interviews with completing parents.

- earlier reports published as part of the RPC programme evaluation showed that referral staff and providers of interventions had found initial referral rates to be lower than expected. Reasons included delays in paperwork, lack of knowledge or awareness amongst referral staff and practitioners, and strict eligibility criteria for a couple of specific interventions. However, following initial teething problems, 2,694 parents went on to complete an intervention.

- parents were referred to the sessions through a range of channels, most commonly, parents were referred by Family Support Workers, Health Visitors and Early Help teams. This was similar for parents who did not start or complete the intervention.

- where parents failed to start an intervention, this was most commonly due to issues relating to their (ex) partner, such as the (ex) partner not wanting to go, not thinking it would improve their relationship and ongoing legal proceedings.

- similar reasons were given by parents who started but failed to complete an intervention. However, the most frequently mentioned reason for stopping the sessions was that they felt the sessions were no longer helping.

- despite this, parents who started but did not complete the sessions rated the convenience of the sessions and the quality of facilitators highly. Just under half of parents who did not complete (42%) felt they would be likely to return to an intervention in the future. The qualitative findings also indicated an appetite for future support amongst both ‘non-completers’ and parents who failed to start.

- as reported over the course of the evaluation, both qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys indicated that the experience of parents who completed the sessions was generally positive; they indicated that they learned new information and found discussions helpful.

- the key strengths of the interventions (session content and course facilitator) were consistent across all qualitative research with parents. Furthermore, six months after completing an intervention, almost all parents stated that their facilitator did a good job of explaining things. This tallied with the perceptions of providers of the interventions who praised the content and felt their staff were comfortable in delivering it.

- in qualitative interviews with parents, the key elements leading to successful delivery of the interventions were:

- the approach and demeanour of the practitioner running the intervention;

- tailoring the content to the parents; and

- providing practical tools, exercises and workbooks for parents.

- around half (49%) of parents thought that their relationship had improved 6 months following completion of the intervention. This perceived improvement was sustained at the 12 months after completion point with 52% indicating an improvement.

- in addition, two-thirds (67%) of completing parents felt that the sessions had a positive impact on their children at 6 months after completion and this increased further by six percentage points at 12 months after completion (73%). This shift between the 6-month and 12-month point was solely driven by an increase in among separated parents (from 63% to 71%). Hence separated parents were less likely to see positive change in their children at 6 months after completion but were equally as likely as intact parents to see this by 12 months after completion.

- there were several other differences between intact and separated parents. Intact couples were generally more positive about the interventions than separated parents. In addition, they were more likely to state that the sessions improved their relationship both 6 months after completion and 12 months after completion.

- qualitative interviews with parents in the final year of the evaluation echoed previously reported findings that the perceived effect of the interventions on the interparental relationship varied between families. Most reported that they had learned something and applied it in practice. A few parents reported no or limited impact on their relationship, mainly due to no behaviour change from their (ex) partner or believing that the relationship was beyond repair.

Training

Introduction

A key part of the RPC programme was the training component for practitioners and other staff who work with parents, comprising of four modules and a Train the Trainer session. These covered an understanding of parental conflict and its impacts, recognising parental conflict, working with parents to resolve this and the role of supervising a team addressing parental conflict. Training was initially delivered face-to-face, but following restrictions introduced during the Coronavirus pandemic, the training was moved online from April 2020 and delivered via the Virtual Learning Classroom (VLC).

Training findings

All components of the training evaluation were completed ahead of the third report on implementation[footnote 4] and hence have been reported previously. The key findings from this previous research were:

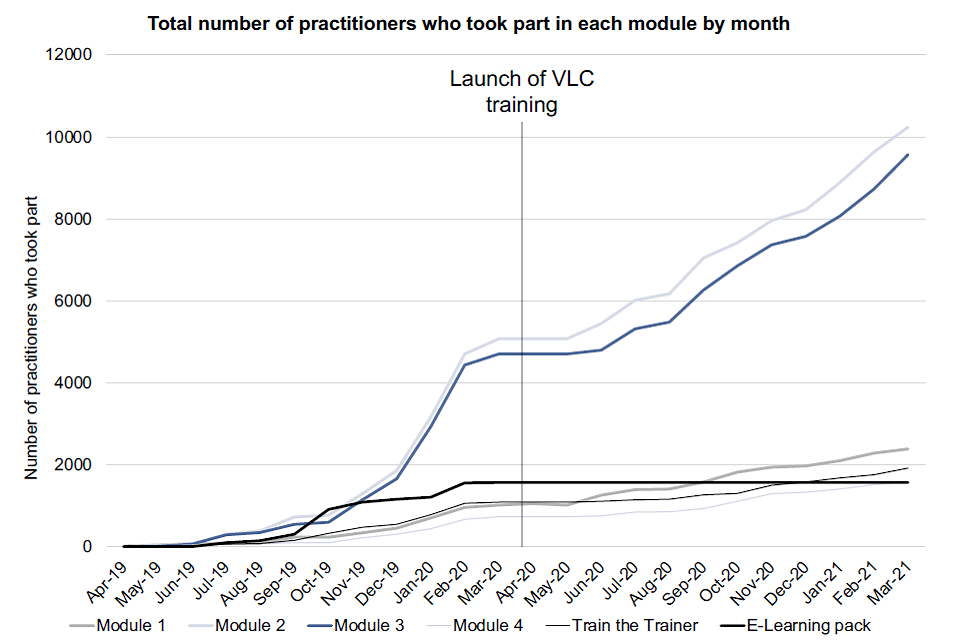

- almost 16,500 practitioners took part in the RPC training between April 2019 and March 2021. Practitioners were evenly split between those attending face-to-face and VLC sessions. Modules 2 (identifying conflict) and 3 (working with parents) had the largest take-up.

- qualitative and quantitative research with practitioners showed the training was well-received. It was felt to be relevant to their work and to provide an appropriate level of detail.

- survey findings showed that most practitioners felt it had significantly improved their knowledge, understanding and ability to address parental conflict (as demonstrated through changes in self-reported ratings on these measures). Most had also applied what they had learned to their day-to-day role. Although most practitioners felt they were applying their skills and knowledge less than they had expected, this could partly be due to the timing given the Coronavirus pandemic.

- overall, the transition to digital delivery of training went well, the number of practitioners taking part in the training remained steady, though each practitioner generally took part in fewer of the four modules after the move to VLC.

- The VLC delivery method worked well for practitioners, with the convenience of this approach highlighted as a strength. However, the format was not generally felt to work as well as the face-to-face format and this was particularly the case for the Train the Trainer module.

Local integration

Introduction

The local integration element of the programme aimed to encourage local areas to consider the evidence base around parental conflict and integrate support for parents in conflict into existing provision.

To support local areas with integration the DWP:

- recruited a team of six Regional Integration Leads (RILs) to promote the agenda and facilitate knowledge sharing and networking[footnote 5]

- provided a Strategic Leadership Support (SLS) grant for local authorities and their partners to use in ways that best suited their aspirations around reducing parental conflict.

- provided a Practitioner Training (PT) grant for local authorities to use to book staff on to courses about reducing parental conflict designed by the DWP.

- encouraged access to information made available on the reducing parental conflict online hub hosted by the Early Intervention Foundation (EIF)[footnote 6]

- offered a Workforce Development Grant (WDG) in 2021/22 with the aim to enable local authorities to have a greater number of staff trained in reducing parental conflict capabilities.

Key integration findings

Key findings from previous integration focused research included:

- prior to the RPC programme, local authorities typically had not thought about tackling parental conflict below levels amounting to domestic abuse.

- the SLS grant was well received by local authorities that appreciated the flexibility it afforded them to use it in the ways that best suited their plans.

- local authorities appreciated the PT’s focus on training as they looked to develop and upskill their staff around RPC. However, they would have preferred to be able to use the funding with their own (local) training provider and/or use the grant to purchase venue space.

- the RILs were a valuable resource in embedding RPC in local authorities, offering support to drive the programme forward and advise on how to spend grant funding.

The new evidence in this report relates to the WDG and how this was used in 2021/22, with findings relating to other integration measures reported previously[footnote 7]:

- the WDG was used by all local authorities, including those that felt their RPC progress had stalled and wanted to re-launch activity, and those that had made significant progress and wanted to drive the agenda further forward.

- local authorities criticised the application process, describing it as involved and time-consuming, and therefore a burden to complete.

- local authorities viewed the WDG positively compared to previous grants, because they found it to be more flexible, allowing them to tailor spending to their specific needs.

- The WDG grant was spent in two key ways: delivering training to practitioners and developing support for parents.

- Without the WDG, the work undertaken would either not have happened at all or would have been on a smaller scale.

- There was an appetite among these local authorities for future funding to continue progress on the reducing parental conflict agenda. Most local authorities were aware of the Local Grant and had already started their application when interviewed in Spring 2022.

Glossary

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Contract Package Area (CPA) | Delivery of RPC interventions took place across 31 local authorities, which were clustered in 4 geographic areas known as Contract Package Areas. These are Westminster, Gateshead, Hertfordshire, and Dorset. |

| Domestic abuse | Imbalance of power or control in a relationship, and one parent may feel fearful of the other. |

| Early Intervention Foundation (EIF) | The Early Intervention Foundation is an independent charity established in 2013 to champion and support the use of effective early intervention to improve the lives of children and young people at risk of experiencing poor outcomes. |

| Frontline Practitioner (FLP) | Local authority colleagues and their partners working with families including those who work for services such as social work, health visiting teams and early years’ services. |

| Parental conflict | Harmful parental conflict behaviours in a relationship which are frequent, intense and poorly resolved can lead to a lack of respect and a lack of resolution. Behaviours such as shouting, becoming withdrawn or slamming doors can be viewed as destructive. Parental conflict is different from domestic abuse. This is because there is not an imbalance of power, neither parent seeks to control the other, and neither parent is fearful of the other. |

| Practitioner Training (PT) grant | The Practitioner Training grant was used to buy spaces for staff in the local authority area to attend bespoke reducing parental conflict training delivered by Knowledge Pool. |

| Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme | The Reducing Parental Conflict programme is the subject of this evaluation. It aims to help avoid the damage that parental conflict causes to children through the provision of evidence-based parental conflict support, training for practitioners working with families and enhancing local authority and partner services. |

| Referral Stage Questionnaire (RSQ) | This is an assessment tool that was developed by subject matter experts to identify the types and levels of conflict parents experience, as well as examining child outcomes. Questions from this were also used in the 6-month and 12-month completing parent surveys. |

| Regional Integration Lead (RIL) | Six RILs in England were seconded from local authorities to DWP. They were available to provide expert advice and support to local authorities and their partners and maximise the opportunities that the programme presents. |

| Strategic Leadership Support (SLS) grant | The SLS grant was used to help local authorities and their partners to raise the profile of parental conflict and fund activities to integrate reducing parental conflict into their provision. |

| Child Maintenance Service (CMS) | Child Maintenance Service assists families with separated parents and ensures an arrangement is in place for how a child’s living costs will be paid when one of the parents does not live with the child. There are two types of arrangements; ‘collect and pay’ where the Child Maintenance Service collects and pays the money and ‘direct pay’ where the CMS help to work out an appropriate amount but the parents make their own payment arrangements. |

| Workforce Development Grant (WDG) | The WDG grant was offered in 2021, to enable local authorities to build Reducing Parental Conflict capability amongst practitioners who come into contact with children and families. This aimed to develop local authorities capabilities and capacity around reducing parental conflict beyond the availability of funding. |

| Local Grant | The Local Grant, which began in April 2022, encourages local authorities to continue to integrate RPC, build the capability of frontline practitioners who support parents and families and improve the overall RPC support offer to families. |

| (Ex) Partner | The term is used throughout the report where findings are in relation to both intact and separated parents regarding their partner or former partner. Therefore, for intact parents who responded, it refers to their current partner, and for separated parents who responded, they are responding in relation to their former partner. |

Chapter 1 Introduction, background, and methodology

This chapter outlines the background to the project and provides an overview of the evaluation methodology.

Context

Parents play a critical role in giving children the experiences and skills they need to succeed. However, studies have found that children who are exposed to parental conflict can be negatively affected in the short and longer term[footnote 8].

Disagreements in relationships are normal and not problematic when both people feel able to handle and resolve them. However, when parents are entrenched in conflict that is frequent, intense, and poorly resolved, it is likely to have a negative impact on the parents and their children. It can impact on children’s early emotional and social development, their educational attainment and later employability – limiting their chances to lead fulfilling, happy lives.

The government wants every child to have the best start in life and reducing harmful levels of conflict between parents – whether they are together or separated – can contribute to this. Sometimes separation can be the best option for a couple, but even then, continued co-operation and communication between parents is better for their children. This is why the DWP introduced the Reducing Parental Conflict programme. Originally backed by up to £39m to March 2021, additional funding was then provided with an extension of the programme secured until March 2022. The programme encouraged local authorities across England to integrate services and approaches which address parental conflict into their local provision for families.

The RPC programme seeks to address parental conflict, not domestic abuse. Where there is domestic abuse there will be an imbalance of power, control, and one parent may feel fearful of the other. If domestic abuse is suspected or identified, a pathway of more specialised support should be offered in place of the RPC programme, and appropriate safeguarding measures implemented.

Evaluation is central to the Reducing Parental Conflict programme. Evidence from the evaluation of the programme will contribute to the wider evidence base on what works for families to reduce parental conflict and will support local authorities and their partners to embed the parental conflict agenda into their services. This is the fourth evaluation report following a series of interim reports, which provides findings on programme implementation at the end of the delivery period.

It is worth noting that further funding has been offered to local authorities called the ‘Local Grant’ following the initial RPC programme. The local integration chapter of this report briefly covers how local authorities felt looking ahead to this. A separate evaluation into the Local Grant launched in December 2022.

Delivery of the Reducing Parental Conflict programme

The programme was designed to increase the support that is available and provided to parents in conflict through different activities:

- intervention delivery: Testing a range of evidence-based interventions in four geographical areas in England that are designed to reduce parental conflict and improve child outcomes.

- training: Provision of training for multi-agency practitioners in all local authorities in England such as Family Support workers, teaching assistants or Police officers to increase understanding of the parental conflict evidence base, enhance their confidence and ability to identify and discuss parental conflict with parents and apply the evidence base in family support practice. Provision for supervisors and managers to support their staff in integrating reducing parental conflict was also delivered.

- local integration: Provision of funding and support to integrate elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families. This included the Workforce Development Grant (WDG) offered in 2021-22.

- a Challenge Fund to test innovative activity, including digital support (which is out of scope of this evaluation)[footnote 9]

- a package of measures, jointly funded with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and Public Health England (PHE) (now known as Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID)) to improve outcomes for children of alcohol dependent parents.

Evaluation

In January 2019, DWP commissioned a large scale, multi-method external evaluation of the programme. This was supported by other strands of analysis conducted by DWP analysts into the effect of the programme on parent relationships.

The external evaluation was largely a process evaluation through which the range of activities supported by the programme were examined to build the evidence base about what works to reduce parental conflict. The aim was to use this evidence to support local authorities and their partners to embed successful elements of parental conflict focused practice and organisation into their services for families.

Mirroring the programme design, the evaluation covered the delivery of interventions, training, and local integration. The main objectives for each element of the evaluation were:

- intervention delivery: To assess how the provision of evidence-based interventions in 31 local authorities, clustered in 4 geographical areas, was implemented and delivered, and the perceptions of impact of the interventions on parental conflict and child outcomes[footnote 10]

- training: To study whether and how the training of practitioners and relationship support professionals had influenced practice on the ground - focusing on the identification of parents in conflict, building the skills and confidence to work with, or refer, parents in conflict and the overall support available.

- local integration: To examine to what extent local authorities across England had integrated elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families, how and with what success.

The table below shows all the different components that have been completed as part of this evaluation. Those in bold have been completed since the previous interim report and so are the focus of this final report. In each section, we provide high level summaries of the findings previously published.

Table 1.1 The RPC programme evaluation elements Integration Training Delivery of interventions

| RPC report | Integration | Training | Delivery of interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covered in ‘Report on early implementation’ | Depth interviews with Regional Integration Leads (wave 1) | Depth interviews with local authority managers and commissioners (includes coverage of SLS) | N/A |

| Covered in ‘Report on early implementation’ | Online survey of local authorities (follow-up 1) | Online survey of practitioners trained (wave 1) | N/A |

| Covered in ‘Report on early implementation’ | Case studies of local authorities (wave 1) | Online survey of practitioners trained (wave 1) | N/A |

| Covered in ‘Second report on implementation’ | Depth interviews with Regional Integration Leads (wave 2) | Depth interviews with practitioners trained | Depth interviews with referral staff (referring parents to interventions) (wave 1 and 2) |

| Covered in ‘Second report on implementation’ | Online survey of local authorities (follow-up 2) and full findings from follow-up 1. | Online survey of practitioners trained (wave 2) | Survey of intervention delivery providers (wave 1 and 2) |

| Covered in ‘Second report on implementation’ | Case studies of local authorities (wave 2), which also includes visits with providers (first 5 case studies) | Online survey of practitioners trained (wave 2) | Survey of intervention delivery providers (wave 1 and 2) |

| Covered in ‘Third report on implementation’ | Best Practice Event with local authorities | Online survey of practitioners trained digitally | Depth interviews with parents who took part in the interventions – Depth interviews with parents who started but did not finish the interventions – Depth interviews with parents who were referred but did not take part in the interventions – Depth interviews with CMS users who took part in the intervention |

| Covered in detail in this final report | Case studies and interviews with local authorities about the additional Workforce Development Grant | Case studies and interviews with local authorities about the additional Workforce Development Grant | Survey of parents (6 months and 12 months after taking part in the intervention) – Survey of non-completing parents – Survey of parents who were referred but did not start an intervention. – Further depth interviews with parents completing an intervention in the final year of the programme |

Methodology

This section provides detail on the approach taken for each of the evaluation elements covered in this report. Further details on the components of the evaluation previously reported on can be found in Annexe 1.

Intervention Delivery

Several different telephone surveys were conducted with parents who had been referred to one of the interventions tested under the 2018–22 programme; including parents who completed one of the RPC interventions (completers), those who had started but not completed an intervention (non-completers) and those who were referred but did not start (did not starts). These surveys covered experiences and perceived impacts of the sessions they attended on their relationships and their children, and reasons why parents failed to start or complete the interventions. To help gauge parents’ experiences of the programme in ‘steady state’ (i.e., when delivery should be at its best), a further 30 qualitative interviews were conducted with completers.

Completer survey (6-month)

A telephone survey of 878 parents who completed[footnote 11] an intervention 6 months after the intervention ended. Survey interviews were completed between 12th August 2020 and 31st August 2022, capturing all completers who had exited their intervention by March 2022. There were some cohorts of parents who took part in sessions up until July 2022, who were not included in the survey.

The response rate to this survey based on the total number of parents who completed an intervention (2,694) was 33%. However, based on the usable records contacted, the response rate was 46%.

A £10 Amazon voucher incentive was offered to completers as a thank you for taking part in the survey.

Completer survey (12-month)

A telephone survey of 374 parents who completed an intervention and responded to the 6-month survey, was conducted around a year after they completed the intervention. This shows a response rate of 14% based on the total population of completers. When based on the number of parents who took part in the 6-month survey and agreed to be recontacted, this represents a response rate of 59%. These surveys were completed between 27th May 2021 and 27th August 2022. As with the 6-month survey, a £10 Amazon voucher incentive was offered to completers as a thank you for taking part in the survey.

Both completer surveys contained a section of relationship measures taken from several academically established tools used to study relationships[footnote 12]. That were also asked of parents in the questionnaire completed ahead of being referred to an intervention, as well as general questions surrounding their experience[footnote 13].

Non-completer survey

A telephone survey of 192 parents who started the intervention sessions but did not complete the full course was conducted. This survey was completed between 22nd July 2020 and 1st August 2022. The response rate was lower than completers at 17%, likely due to lower engagement with the programme, but there was also no incentive offered for this survey.

Did not start survey

A telephone survey of 66 parents who were referred to an RPC intervention but did not start the course was conducted. This survey was completed between 1st December 2021 and 28th June 2022. This element aimed to understand the reasons for parents not starting the interventions, given that the MI data did not hold this information for the majority of parents. Although an incentive payment was offered, engagement with this survey was the lowest of the surveys, with a response rate of 13%. As with the non-completer survey, a lower level of engagement with the programme, given parents did not start the intervention, is likely to have contributed to this. In addition, it is worth flagging that this fieldwork commenced later than the other surveys reducing sample and time available to maximise completes.

According to the MI data collected, the total population of did not start parents could be up to 1,308 parents, leaving the 66 completes a very small proportion of this. In this context, it is unknown how representative this sample is and worth considering the potential non-response bias. Having said this, the survey data is the most reliable source of information available regarding these parents and their reasons for not starting the interventions meaning it gives some indication of the perspectives of this group.

Qualitative interviews with completers

Many qualitative interviews have been conducted with completers for previous reports. An additional 30 qualitative interviews with completers were conducted between 7th March and 8th April 2022. Interviews lasted around 45 minutes. These interviews aimed to gain feedback on the support received from the interventions under the extension to understand how it compared to earlier experience of the interventions. These interviews encompassed a wide range of completers, both intact and separated couples and some using CMS, and others not.

Local integration: Workforce Development Grant (WDG)

Qualitative case studies across ten local authorities who received the Workforce Development Grant (WDG) and one non-bidding local authority, speaking to a total of 22 interviewees between May and June 2022 were conducted. The case studies focused on local authorities’ experience of the WDG. The discussion with the non-bidding local authority explored their decision not to apply for the WDG.

Chapter 2 Intervention delivery

This chapter explores the experiences of parents referred to the interventions tested under the 2018–22 RPC programme. The key findings section summarises findings across the duration of the evaluation. The remainder of the chapter includes more detail on the strands of the evaluation completed in 2022. It covers quantitative findings from those that completed an intervention, based on interviews conducted 6 and 12 months after completion, as well as survey interviews with parents who failed to start or complete an intervention. It focuses on parents’ perceptions of how the sessions they attended went, any potential impacts and why some failed to start or complete the sessions. Findings from the final set of qualitative interviews with completers are also covered showing how these later experiences differ, if at all, from earlier in the programme.

Introduction to intervention delivery

Testing of interventions through the RPC programme aimed to deliver evidence about what works to reduce parental conflict and improve children’s outcomes.

Eight different interventions were tested as part of the programme (further details on these is outlined in Table 2.1). Some of these have a relatively strong evidence base supporting their efficacy in the UK, but not necessarily for all family types or for different delivery methods. Others have been successful in non-UK settings but have not been tested in the UK. These were chosen as, in all cases, the interventions being implemented present significant opportunities for learning. These interventions were designed to be delivered face-to-face but were quickly adapted to be delivered virtually in response to the Coronavirus pandemic.

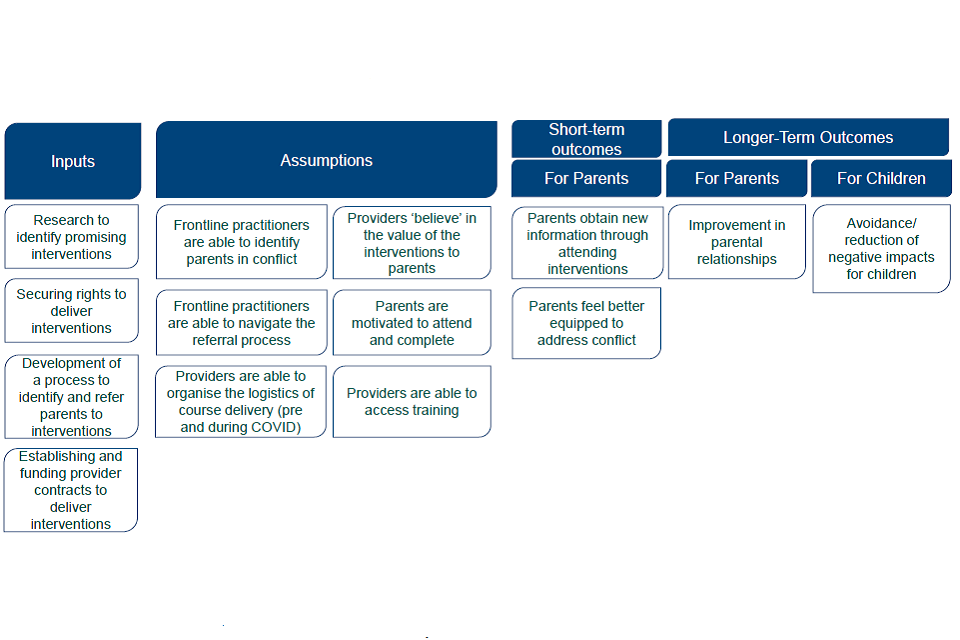

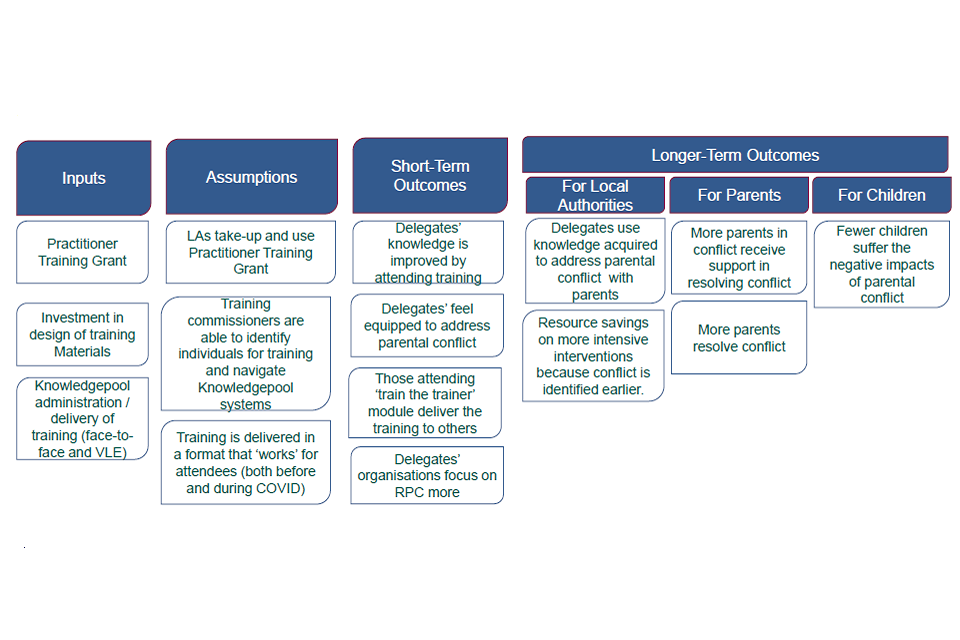

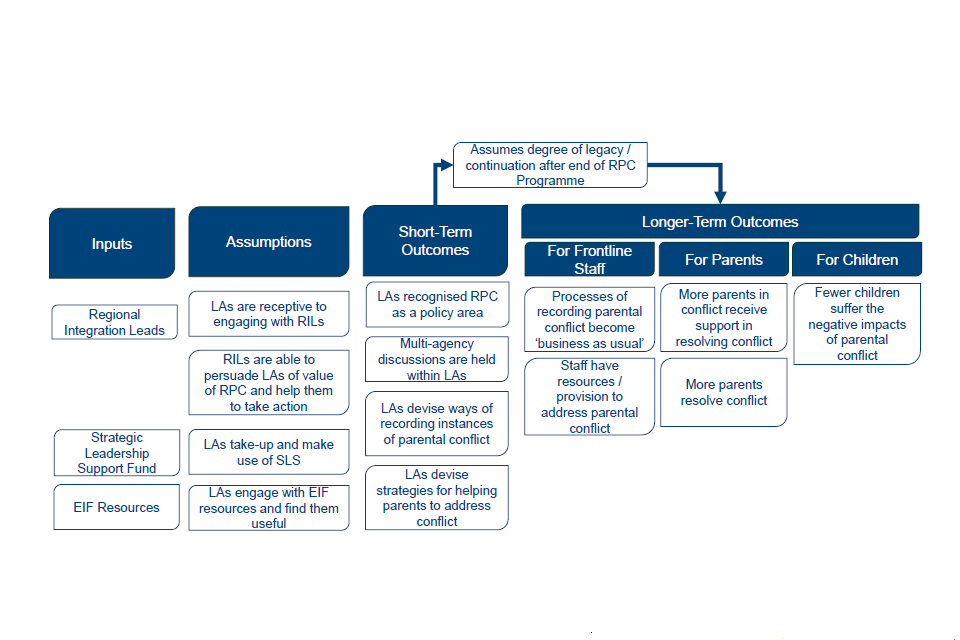

The interventions aimed to achieve a number of short-term and longer-term outcomes for both parents and children as set out in Figure 2.0, based on a number of inputs and assumptions around provider delivery. The research covered in this report explores some of the assumptions and short-term and long-term outcomes in this model.

Figure 2.0 Logic Model for Interventions delivery

Interventions were of either a moderate or high intensity, though this measure was not communicated to parents. Where possible, parents were allocated to an intervention based on the level of conflict in the relationship. However, in some circumstances, parents were referred onto different intensity provision based on other factors such as availability and timings of interventions. The level of conflict in the relationship was identified via an assessment tool developed for the programme by subject matter experts, known as the Referral Stage Questionnaire (RSQ). This was administered to parents by a frontline practitioner working with the family. It consisted of a range of established assessment scales to identify the types and levels of conflict parents were experiencing. It examined the mechanisms through which child outcomes were affected, and the features of an inter-parental relationship that had been shown to impact on children’s outcomes. If either parent scored high for conflict, both parents were offered a high intensity intervention. Flexibility was granted with regards to the intensity of intervention in early 2020, enabling providers to offer parents either high or moderate interventions in certain circumstances, regardless of RSQ outcome.

Some interventions were delivered in a group setting, some as couple sessions and some on an individual basis. Different interventions had differing eligibility, but couples who remained in a relationship as well as those who had separated were eligible for some and existing and expectant parents were also eligible.

The full list of interventions is shown below. Delivery of these interventions continued throughout the Coronavirus pandemic and lockdown with the majority switching to digital delivery over Teams or Zoom.

Table 2.1 Interventions being delivered

| Intervention Name | Brief Description | Method of delivery | Target group | Length of delivery | CPA | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4Rs and 2Ss Family Strengthening Programme | Curriculum-based practice designed to strengthen families, decrease child behavioural problems, and increase engagement in care. It focuses on evidence-informed parts of family life that have been empirically linked to youth conduct difficulties. | Groups of 12-20 parents | Both intact and separated couples with children aged 7-11 | 16 weeks | Hertfordshire | High |

| Family Check-up | This involves 3 stages: an initial interview, family and child assessment, and feedback. The second stage involves the delivery of Everyday Parenting (EDP), which is a behavioural parenting intervention tailored to meet specific needs. | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | Suitable for intact and separated couples, but during this test only 7 separated families completed this intervention | 3-4 sessions of 50-60 minutes | Dorset – Westminster – Gateshead – Hertfordshire – Moderate | |

| Enhanced Triple P | This is a targeted selective intervention, which aims to address family factors that may impact upon and complicate the task of parenting, such as parental mood and partner conflict, and problem child behaviours. | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | For both intact and separated couples 4 modules delivered to families in 3 to 8 individualised consultations (8-12 hours) | Westminster | High | |

| Family Transitions Triple P | Designed as an intensive intervention for parents experiencing difficulties due to separation or divorce, it focuses on developing skills to resolve conflicts with former partners and how to cope positively with stress. | Groups of approximately 8 parents (separated parents are encouraged to attend different sessions) | Separated couples only | 5 sessions lasting 2 hours each | Dorset – Westminster | High |

| Mentalization Based Therapy – Parenting Under Pressure | Aims to help separated or intact couples experiencing high levels of interparental conflict to gain more perspective in order that they can start to put the needs of their children first. It is based on a model which comprises an initial phase of preparation and assessment, meeting with each parent separately. | One practitioner delivers sessions to intact couples. With separated couples each parent completes sessions with a separate practitioner. In rare cases the parents can complete the final session together with both practitioners. | For both intact and separated couples | 10 sessions of therapeutic work | Gateshead – Hertfordshire | High |

| The Incredible Years, including Advanced Programme | The focus is on parents’ and children’s communication and problem-solving skills, knowing how and when to get and give support to family members and recognising feelings and emotions. It’s a group programme, basic is approximately 16 weeks with an additional 8 for advanced. | Group sessions of 12-20 parents | Couples and separated co- parents with children aged 4-12 years | 12-20 sessions as part of the ‘Basic’ course, with an additional 9-11 session for ‘Advanced’ (average of up to 20 weeks) | Dorset –Gateshead | High |

| Parenting When Separated | Drawing on international long-term evidence, it highlights practical steps parents can take to help their children cope and thrive as well as coping successfully themselves, where the parents are preparing for, going through, or have gone through separation or divorce. | Group intervention delivered by 2 practitioners to groups of 12 participants | Separating or separated couples | 6-week course of 2.5-hour sessions | Gateshead – Hertfordshire | Moderate |

| Within My Reach | This is a targeted selective intervention, for low-income single parents, who may or may not be in a relationship. The intervention therefore targets relationship outcomes in general, rather than focusing on parenting or parental conflict. It covers 3 key themes: Building Relationships, Maintaining Relationships and Making Relationship Decisions | Delivered in a group to individuals (not couples) | Separated couples only | 15 sessions, each lasting 1 hour | Dorset – Westminster – | Moderate |

Key findings

Referral stage

- the evaluation explored the nature of the conflict in relationships ahead of being referred to an intervention. Research with parents who attended showed that these parents were experiencing varying levels of conflict. Separated parents, regardless of whether they completed an intervention or not, were most likely to present with high levels of conflict. Interviews conducted in May-June 2021 with Child Maintenance Service (CMS) users showed that this subgroup had experienced very high levels of interparental conflict.

- in addition, parents typically had more than one source of conflict within their relationship. Most commonly these included approaches to parenting, such as disagreements over discipline; financial issues; access and maintenance for separated parents. Intact couples tended to talk in terms of encountering conflict in all aspects of their day-to-day lives.

- earlier stages of the evaluation captured the views of practitioners, referral staff and providers of the interventions, from late 2019, through 2020 into early 2021. Practitioners and referral staff felt confident identifying the signs of parental conflict in order to make a referral, although the lockdown restrictions, curtailing face-to-face interaction with families, made identification more challenging after March 2020.

- however, there was evidence, early on, of some confusion among referral staff about the eligibility of families experiencing domestic abuse, working families, those expecting a child and couples where only one of the parents wanted to take part. This evidence was shared in early implementation stages, and referrals increased, however, providers more often noted this was due to the shift to online delivery, rather than increased clarity amongst referral staff.

- overall, practitioners felt the referral process was straightforward, quick and generally worked well.

- in the earlier stages of the RPC programme, in early 2020, providers experienced lower than expected rates of referral. For some interventions, providers felt this was partly due to a lack of frontline practitioner awareness or insufficient understanding of the intervention for them to adequately explain the intervention to parents or be confident that the referral was appropriate.

- Providers also felt the strict eligibility criteria for some interventions prevented referrals being secured in sufficient volumes. This was particularly the case for 4Rs and 2Ss and Incredible Years Advanced.

- in qualitative interviews across the life of the evaluation, the most common ways parents reported being referred onto the RPC interventions was via Family Support Workers, Health Visitors/Early Help teams and schools. This remained consistent from early qualitative interviews to the latest cohort in 2022. The most common referral channels also appeared consistent whether parents failed to start or complete as well, with family support workers or social workers the most frequently mentioned channels. This consistency suggests that there was little or no influence of referral channel on whether a parent started or completed an intervention.

Attending the interventions

- participation in the intervention was voluntary for all parents. The vast majority of parents who completed an intervention understood that they had a choice about whether to take part. Where parents did not start or complete an intervention, the perception that they had a choice about attending was in line with completing parents, indicating that the perceptions around whether the intervention was mandatory was unlikely to contribute to whether parents attended or completed interventions.

- a small minority of parents who were interviewed (qualitatively) that felt they did not have a choice in taking part, reported feeling pressured by social services or schools to take part.

- those who did not start or complete an intervention generally had a good understanding of the reason why they had been referred and did not feel there was anything else they wished they had known at that point. This was evident during previous qualitative research published in earlier reports, and is substantiated by findings from the quantitative surveys.

- three-quarters (73%) of those who did not start an intervention were keen to take part, however, only a quarter (26%) felt that their (ex) partner was keen. Linked to this, the main reasons given for not starting were reasons relating to their (ex) partner (44%). This highlights the role of the attitude of the (ex) partner in attendance at an intervention.

- however, issues relating to the (ex) partner were not the only reasons for not starting, with around a fifth (21%) of those who did not start stating the (un)suitability of the support as a reason. Other reasons included not feeling like they needed the support, thinking a different kind of support was needed, and not feeling comfortable taking part.

- delivery of most of the interventions was underway before the Coronavirus national lockdown began in March 2020, though most providers started delivery later than planned. This was primarily due to low levels of referrals, with access to intervention training for delivery staff and paperwork also contributing to delays.

- almost all interventions moved to digital delivery through video-conferencing platforms such as Zoom or Teams at the start of the Coronavirus pandemic. This transition was generally considered to have worked well for all interventions and was seen to bring some benefits including more flexibility with timings and increased parent participation.

- in line with this, the survey findings demonstrated that it was most common to take part digitally from home (83% of parents who took part in the 6-month survey) with small proportions taking part face-to-face at home or at a venue. Whether they took part online or face to face, parents were generally positive about the mode of delivery. Most completing parents agreed that the timing (94%) and location (87%) of the sessions were convenient and were able to find suitable childcare (83%). This was echoed in the qualitative interviews where parents tended to be happy with the session timings, duration, and frequency.

- for the majority of families who completed the sessions, both parents took part in an intervention (79%). However, often they attended separate sessions (61% of all completing parents). Separated parents were less likely to attend the sessions with their ex-partner (11%). Generally, parents felt attending the sessions with or without their (ex) partner worked well. However, of those attending alone, 31% would have preferred to take part with their (ex) partner.

- similarly, whether they attended group or one to one sessions, parents were positive about the format, suggesting they were allocated appropriately at the referral stage and/or that the provision worked equally well in both formats. Those in group sessions found it reassuring to hear the perspective of other parents, while those in one-to-one sessions felt they would have been less able to open up in a group setting.

Perceptions of the interventions

- throughout the lifetime of the interventions test (2019–22), parents tended to have positive overall impressions of the sessions they attended, describing them as helpful and feeling they took away valuable lessons for their relationship. Where parents were less positive, it was because they deemed sessions inappropriate to their situation.

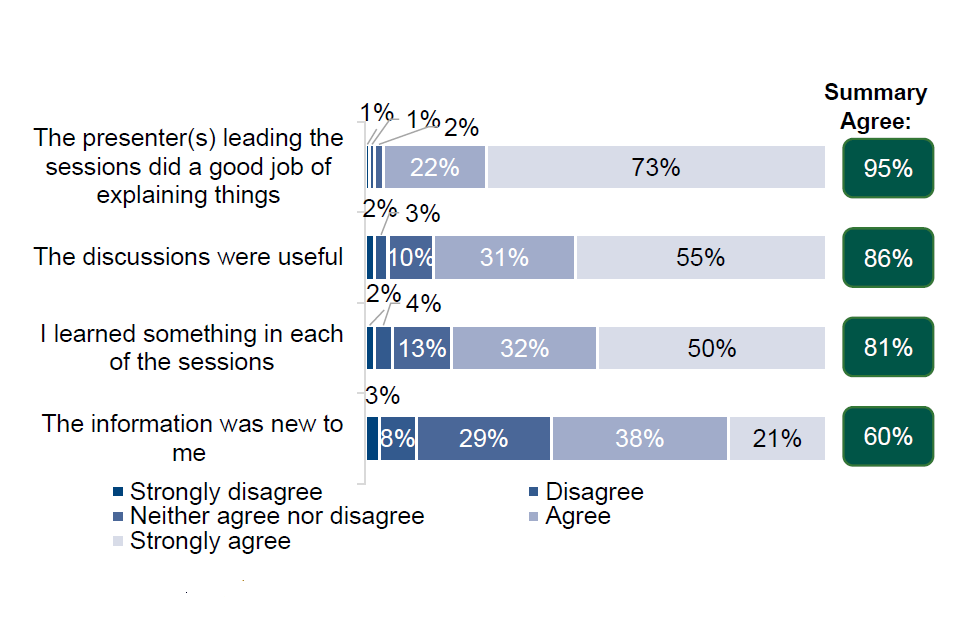

- the main strengths of the interventions were session content and the course facilitator, consistent with earlier qualitative interviews conducted as part of the evaluation. This was echoed by findings from the survey with completing parents 6 months after completion, with the vast majority (95%) stating that the facilitator did a good job of explaining things. Qualitative interviews specifically highlighted that the course facilitators left parents feeling ‘comfortable’, ‘valued’ and able to provide an impartial ear for the issues in their relationship.

- the majority of parents agreed that the discussions were useful (86%) and that they learned something in the sessions (81%) 6 months after completion, though this was more likely for intact parents than separated parents. Qualitative participants further evidenced this, stating that they felt the course content was relevant and insightful, with many parents singling out video content as particularly useful. Parents felt the course content, and discussions within the sessions, gave them valuable insight into both their own and their partners behaviour.

- in line with previous qualitative findings, the survey of parents who did not complete the sessions showed that these parents still had some positive reflections on the sessions they attended. Logistically, three quarters of parents who did not complete the intervention (76%) felt that the sessions were at a convenient time, which was echoed in qualitative interviews with these parents, who mostly felt sessions were convenient, offered at a time, place and in a mode that worked for them. Eight in ten (80%) parents who did not complete the intervention felt that the presenter(s) leading the sessions did a good job of explaining things. Building on previous qualitative findings where parents felt the sessions were delivered by high quality facilitators, who were seen as ‘approachable’ and ‘understanding’, and ultimately provided a ‘safe space’ to discuss difficult issues.

- regarding what parents learnt, the research suggests that parents who failed to complete interventions generally learnt less than parents who completed, though a small minority of parents who did not complete the intervention explained in qualitative interviews that the course content helped them to rethink their role in their relationship.

- in earlier components of the evaluation, providers also praised the content of the interventions and felt their staff were comfortable in delivering them. In particular, they commended the materials and resources they were provided.

- by specific intervention, providers of Parenting When Separated experienced higher rates of parents who did not start or did not complete all sessions. Providers speculated that this was potentially due to the intervention being delivered in a group with other parents, which may have been off-putting for some parents. Providers also felt that Incredible Years Advanced was a particularly long intervention due to the necessity to complete the basic course ahead of this, increasing the number of sessions required. In addition, it did not explicitly address relationships early on, both factors which they felt had led to high drop out and low completion rates.

- criticisms and concerns raised by parents in relation to the interventions they had attended were more evident in qualitative interviews conducted earlier on, rather than in the latter stages in 2022, suggesting that issues were addressed as the programme progressed. Concerns included issues with some of the content of the interventions: in some cases, course content was felt to be either not relatable to their current situation, too general to be helpful or lacking in structure. Parents who did not complete an intervention also highlighted issues with the interventions, such as the content not being suitable for their level of conflict.

- from the experience of parents, it appeared that there were four key elements to delivering the interventions well:

1. The approach and demeanour of the practitioner running the sessions.

2. Tailoring the content, so it was relevant to the specific background and situation of the parents. Some parents facing specific challenges, such as children with learning difficulties or an ex-partner with addiction issues, found interventions ill equipped to address their needs.

3. The use of practical tools and exercises to help parents think in different ways.

4. Providing workbooks so parents had a log of what had been covered and future content. This also allowed them to reflect on the course after the sessions.

- for parents who did not complete the sessions, reasons given in previous qualitative interviews were echoed in the quantitative survey. These centred around the sessions no longer helping (27%) and issues related to (ex) partner (21%) although there were a wide variety of other reasons cited including practical issues with attendance (15%).

- timing of the sessions generally was not viewed as a contributing factor for failing to start the intervention. Six in ten (61%) stated it did not contribute and only one in six (17%) stated it did.

- positively, there was appetite from around half of both non-completing and did not start parents to take part in similar support in the future. In order to understand the impact of the timing of support, parents were asked when it would be best to receive this, and generally non-completer and did not start parents stated this could be provided at any time.

Parents’ perceived impacts of the interventions

- at both 6 months and 12 months after completion point, around half of parents surveyed felt that taking part in the sessions had improved their relationship (49% and 52% respectively). The figure was much higher for intact than separated parents at both stages, with around three quarters of intact parents (72% 6 months after completion and 75% 12 months after) stating that the sessions had improved their relationship. In qualitative interviews conducted prior to 2022, intact parents more commonly cited positive impacts than separated parents, as well as citing a wider range of impacts on their relationship, such as fewer arguments and better communication.

- other groups of parents more likely to agree that their relationship was improved by the sessions included those who took part in the intervention with their (ex) partner, this is likely to be linked to the fact that intact parents were more likely to attend together.

- six months after completion, CMS users, fathers and parents in one CPA were less likely to agree that the sessions improved their relationship, though this stabilised and was in line with other parent groups 12 months after completion.

- further qualitative interviews with completing parents demonstrated a positive impact on them, though to varying degrees. In addition, providers felt they could see the positive impact on the parents they delivered to when they took part in the evaluation in 2021.

- the 2022 cohort of completing parents who took part in the qualitative interviews reported varying levels of impact on their relationship.

- Those who reported a high level of impact found they were able to communicate better with the other parent and appreciate their perspective more, enabling more effective resolution of conflict when it arose. This group included an even mix of separated and intact parents.

- Some parents felt a more modest impact, feeling that there had been some impact, but many old patterns of behaviour persisted. For example, separated parents often felt better able to manage contact with their ex- partner without reporting an improvement to the actual relationship.

- Many parents felt that while they had learned something it had resulted in a perceived limited impact to the relationship. Typically, this was because they felt there had been no subsequent behaviour change from their (ex) partner.

- A few parents reported no perceived impact to their relationship from the sessions. This smaller group, comprised of both separated and intact parents, tended to be united by a belief that the relationship was broken beyond repair, negating the possibility of any impact on their relationship from the sessions.

- parents who felt the sessions had improved the relationship with their (ex) partner were more likely than others to report that their children were less anxious and happier following the sessions.

- previous qualitative research with parents who did not complete an intervention suggested that most felt that the sessions they did attend had little to no impact on their relationship. These parents tended to be separated parents. The lack of perceived impact on the interparental relationship appeared to be due to the high level of conflict within the relationship. These parents tended to report constantly arguing with their ex-partner or not being in contact at all with their ex-partner before the sessions began.

- in terms of the perceived impacts on their children, regardless of impact on their own relationship, completing parents in qualitative interviews over the life of the evaluation felt they had seen some positive changes in their children or children’s behaviour since attending the intervention.

- this was echoed in the quantitative surveys where there was evidence of a positive perceived impact on the children of the completing parents, which increased over time from 6 months after completion (67% had observed a positive impact) to 12 months after completion (73%). This upward shift over time was solely driven by separated parents, who were less likely to report an impact 6 months after completion than intact parents but showed an 8-percentage point increase between 6 and 12 months to bring them in line with intact parents. In the qualitative interviews separated parents reported improved compliance and agreement over access to children. It may be that improved access can make it more likely to see a positive impact on children, as they experience an improvement in their relationship with one or both parents.

Findings explained

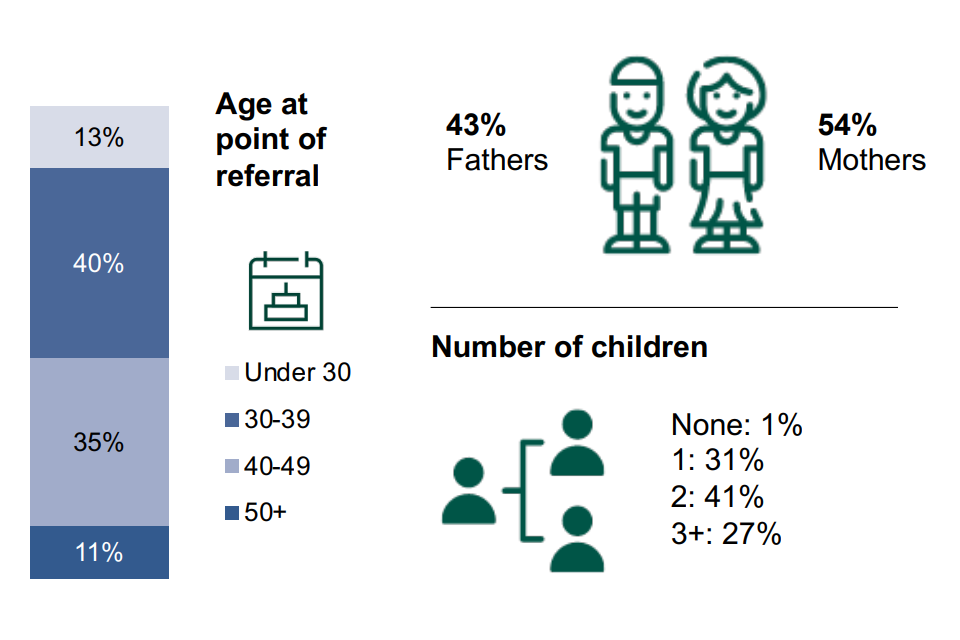

Profile of completing parents

Between 2019 and 2022, a total of 2,694 parents completed one of the interventions offered as part of this component of the 2018–22 RPC programme. Almost 1,000 of these took part in Mentalization Based Therapy, which was by far the most commonly attended intervention. A full breakdown of the population by intervention is shown in Figure 2.1. 4Rs and 2Ss Family Strengthening Programme received no referrals at all. For those that received referrals, Incredible Years Advanced supported the lowest number of parents, with 52 completing this intervention.

Parents who had completed an intervention were contacted both 6 months and 12 months completing an intervention. A total of 878 parents completed the survey conducted 6 months after completing an intervention, with 374 also going on to complete the survey conducted 12 months after completion. For the findings to be representative of the overall population of parents who completed an intervention, the data were weighted to match the population. The variables used in the weighting were: type of intervention, whether one or both parents took part in RPC, work status of the family, gender of parent, age of parent at point of referral and the number of children.

Figure 2.1 shows the profile of parents who completed the interventions. Over a third (35%) of all parents who completed an intervention participated in Mentalization Based Therapy, making it the most dominant intervention within the test. Looking at participating in all the interventions tested, the majority of parents (79%) had both parents in the family take part in an intervention, with 21% participating as the only parent from the family. There was a spread of age and gender among those attending and parents usually had 1 to 2 children.

Figure 2.1 Profile of completing parents

| Programme | Completing parents % |

|---|---|

| Mentalization based therapy: parenting together | 35% |

| Family Transitions Triple P | 16% |

| Parents Plus when Separated Programme | 12% |

| Within my Reach | 10% |

| Enhanced Triple P | 10% |

| Family Check Up | 6% |

| The Incredible Years, including Advanced Programme | 2% |

| Parent status | Completing parents % |

|---|---|

| Both parents working | 38% |

| One parent working | 29% |

| Both parents unemployed | 10% |

| Families with one person on RPC | 21% |

| Unknown | 2% |

Note: From the above table, both parents on RPC totalled 79%.

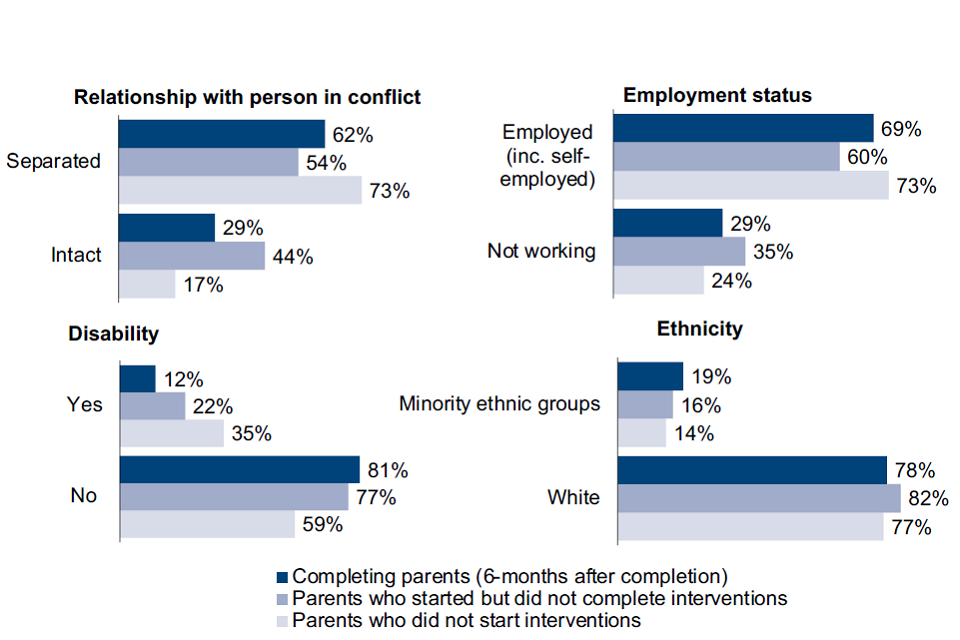

The interventions component of the 2018–22 RPC programme aimed to test support to help both intact and separated couples. Separated couples made up a higher proportion of completing parents (62% at the 6-month point and 69% at the 12-month point). Conversely, 29% of completing parents were in intact couples at the 6-month point and a similar proportion (28%) at the 12-month point[footnote 14].

Between the 6-month and 12-month points, the relationship status of completing parents with the person they were experiencing conflict with generally remained the same. However, of the parents who took part in the 12-month survey, a small proportion (3%) had separated and 1% had got back together.

Six months after completion, around a third (32%) of separated parents were using the Child Maintenance Service (CMS) and a further 30% had agreed their own family-based arrangements. At the 12-month point, similar proportions were using the CMS (31%) and or had family-based arrangements in place (32%). For the majority, this was working well at both the 6-month (77%) and 12-month (76%) points.

At both the 6- and 12-month points, parents had a range of non-financial arrangements in place with their ex-partner, most commonly, having children overnight (64% at 6 months and 62% at 12 months). However, for around a fifth (18% at 6 months and 23% at 12 months) of separated parents, they had no non-financial arrangements in place. This is detailed in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Types of non-financial arrangements in place for separated parents

| Types of non-financial arrangement | 6 months after completion | 12 months after completion |

|---|---|---|

| Has children overnight | 64% | 62% |

| Takes child/ren for days out/treats | 53% | 44% |

| Pays for things like children’s clothes | 44% | 37% |

| Takes child/ren on holiday | 40% | 35 |

| Helps with nursery/ school run | 35% | 32% |

| No – no non-financial arrangements in place | 18% | 23% |

| Has children sometimes but not overnight | 7% | 7% |

Base: All separated completing parents (6 months after completion: 562, 12 months after completion: 261)

The journey to the RPC programme

Referral pathways

Parents first became aware of the programme in a range of ways. Most commonly this was through Family Support Workers, Health Visitors/Early Help teams and schools but also through word of mouth and social media. Sessions tended to be presented as support that would help parents to improve their communication with each other and their children. Research with different cohorts of parents during the life of the programme suggests that this remained consistent throughout delivery.

After becoming aware of the programme and completing the Referral Stage Questionnaire, parents tended to receive further communications about the specific sessions they had been referred to over the phone with the session organisers.

Once parents were told which sessions they would attend, most parents started their sessions within a month. For some it was much quicker, with some only waiting a week. However, some other parents reported waiting several months before they attended their first session.

In line with previously published qualitative findings with completers, parents generally felt that they were given all the information they needed. Other than clarifying whether their (ex) partner would be in attendance they did not tend to have any further questions about the sessions.

Motivations for taking part

Participation in the interventions was voluntary for all parents. Most parents who took part (89% 6 months after completion) felt that they had a choice about whether to take part at the point of referral. This left a small proportion of parents who felt it was mandatory, which varied by parent group and location. The belief that they had a choice about attending was higher for intact parents compared with separated parents (96% compared to 87%).

Agreement that they had a choice about whether to take part at the point of referral was higher among those who had agreed a child maintenance arrangement themselves rather than those who used the CMS or who had no arrangement in place at all (93% compared to 85% and 83% respectively, 6 months after completion).

The proportion of parents who felt they had a choice about taking part was consistent across the interventions, and the number of parents who felt that they did not have a choice was slightly higher amongst parents attending Parenting When Separated (13% compared to 8% overall 6 months after completion). Across contract package areas (CPAs), it was more common for parents in one of the four CPAs to feel they had a choice about taking part (93%) but less common for those in another CPA (81%). This may in part be due to one CPA having more intact parents, who were also more likely to feel that there was a choice in attending. The CPA where it was less common for parents to feel like they had a choice had a greater proportion of parents on Parenting When Separate.

Alongside this, a few separated parents in one CPA mentioned during the qualitative interviews that the involvement of social workers in their case made them feel pressure to take part (although this pressure was not directly applied by social workers themselves, more a perceived pressure), and they were fearful that their refusal to participate could adversely impact their access arrangements.

In the qualitative interviews, parents reported that they felt that attending the sessions was their choice and they reiterated that staff who referred them had made this very clear. In the few cases where parents did not feel they had a choice, they reported feeling pressured by social services or their children’s school. In one instance, a parent reported that their child’s school had (incorrectly) informed them that they could be fined or taken to court if they did not take part in the sessions.

For those who took part in the quantitative survey, those who felt they did not have a choice about taking part were repeatedly more negative about their experience.

The majority of parents expressed in the qualitative interviews that they were keen to try any support that was available and commonly felt optimistic or hopeful when the sessions were first mentioned. This was reflective of a sense of desperation for some kind of solution to the issues many parents faced and was largely true of parents throughout the evaluation period.

In the qualitative interviews, parents that felt less positive prior to the sessions were almost exclusively fathers. These parents either felt that they did not need the support or cited concerns around talking in a group setting or their attendance being recorded by the council.

Experience of the interventions

Overall impressions of the sessions

As in previous stages of the evaluation, parents tended to have a positive overall impression of the sessions. They were often described as ‘helpful’ and left parents feeling like they had learned valuable lessons for their relationship. A few also described really enjoying the sessions themselves, beyond just finding them useful, and came to look forward to attending.

I really enjoyed them and looked forward to them each time they were due.

Mother, Separated, Completer

Parents indicated how they felt about certain aspects of the sessions 6 months after completion and generally these findings were positive. Almost all parents (95%) agreed that the presenter(s) leading the sessions did a good job of explaining things, the majority of parents (86%) agreed that the discussions were useful, and approximately four in five (81%) parents felt that they learnt something in each of the sessions. This is broken down further in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Parents experience of the sessions

Base: All completing parents (6 months after completion: 878)

Other than their views on the presenters leading the sessions, intact parents were more positive than separated parents across all statements relating to their experience of the sessions. This difference was most prominent in the proportion who agreed that the information was new to them (71% of intact parents compared to 56% separated parents).

In the qualitative interviews, a few parents had less positive and occasionally negative overall impressions of the sessions. These parents felt the sessions were not appropriate for them, either in terms of:

- content; feeling that it was aimed at parents earlier on in their relationship;

- format; feeling attending with their ex-partner was not beneficial;

- or because they felt the other parents were from backgrounds different to their own and they could not relate to each other’s situation.

This chimes with the minority view from previous stages of the evaluation, where a few parents outlined less positive overall impressions for similar reasons.

I think it was very useful and good, but I think that it was more for people that are just beginning to want to get married, before getting married.

Mother, Separated, Completer

What worked well?

Session content and structure

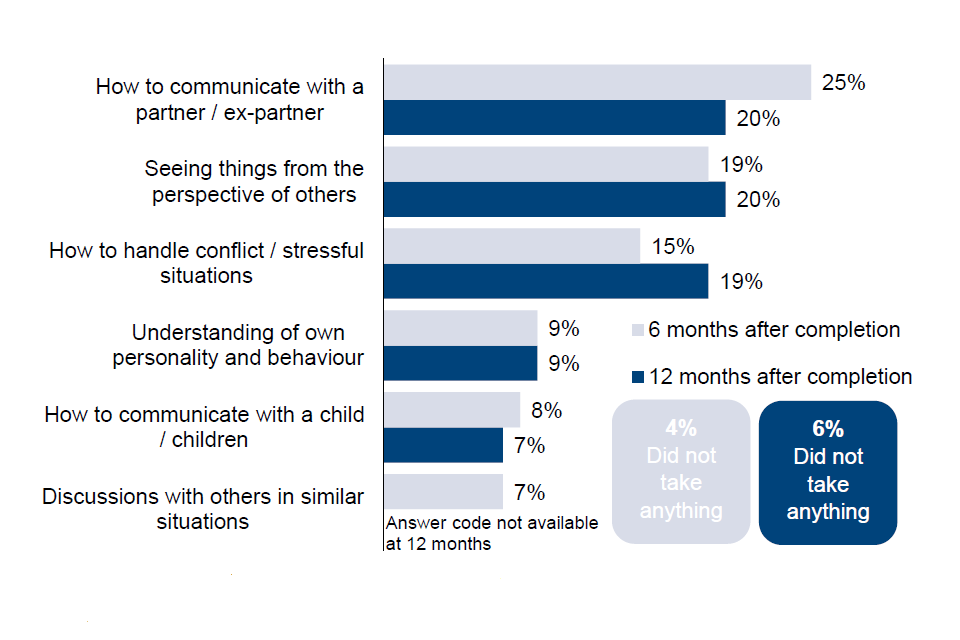

Six months after completing the intervention, it was rare (4%) for parents to feel that they took nothing useful from the sessions. Most commonly, both separated and intact parents felt that learning how to communicate with their (ex) partner was the most useful thing they took from the sessions (25%). Other common ‘most useful elements’ were seeing things from the perspective of others (19%) and how to handle conflict / stressful situations (15%).

Figure 2.4 shows this in more detail with findings from both 6-month and 12-month surveys.

Figure 2.4 The most useful thing taken from the sessions at 6 months and 12 months after interventions

Base: All completing parents (6 months after completion: 878; 12 months after completion: 374)

Between the 6-month and 12-month points, parents’ perception of the most useful elements of the sessions remained similar.

Intact parents were more likely than separated parents to feel that aspects of the session around improving their relationships were the most useful. For example, they were more likely than separated parents to say how to communicate with their (ex) partner (31% compared to 22%) or seeing things from the perspective of others (27% compared to 17%) were the most useful things they took from the programme.

Conversely, separated parents more often valued elements of the sessions that supported them personally; they were more likely than intact parents to think the most useful aspects were discussions with others in similar situations (10% compared to 2%) or the reassurance that they were doing the right thing (5% compared to 1%).

Use of the CMS appeared to correlate with what parents found most useful about the sessions. CMS users were less likely than others (19%) to think how to communicate with their (ex) partners was the most useful thing to take from the sessions at 6 months after completion (although this was still the most commonly mentioned ‘most useful’ element).

One year on from the sessions, just under a third of CMS users felt the most useful thing they took from the sessions was how to handle conflict / stressful situations (29%) making this the most mentioned element for CMS users at this point.

These findings regarding the usefulness of the content were evidenced and expanded on in the qualitative interviews. Parents mostly felt that all the content was useful and relevant to them. Parents found it useful to see videos or hear from other participants about conflict situations that they regularly found themselves in. In some cases, this was useful in that it allowed them to reflect on the ways they communicate in these situations and learn new ways for the future. However, in some instances they just found the discussion reassuring, as it made them feel less alone, knowing that other parents shared their experience.

Parents often found the course content gave them greater insight into their relationships. In some instances, this was helping them to develop a deeper understanding of their (ex) partner’s perspective, while for others this was an understanding of how they approached relationships and some of the challenges this might create. Often this insight arose from discussions with the course facilitator about the session’s content or clips they had seen in videos designed to encourage them to reflect on their own situation.

We would go through the session together so sometimes we would talk about a chapter in the book, pause and discuss a few points that I would raise, or she would raise. And most sessions we watched a video and then would reflect back on what we had watched.

Mother, Separated, Completer

Where parents took part with their partners, they often noted that it was useful to be given a set time and space to talk to their partner without distractions.

Separated parents who took part alone tended to value the session content around mindfulness and making time for themselves. Many came to realise that this was something that they were not doing previously but would benefit from.

Both separated and intact parents taking part in one-to-one sessions felt the content was appropriately tailored to their own circumstances and therefore felt in general that all of the sessions were very useful.

Session facilitators

Most of the parents in qualitative interviews were overwhelmingly positive about the facilitators running the sessions. They commonly felt session leaders did a good job of explaining things, however, most parents put more emphasis on the way session leaders made them feel in the sessions. Parents described how the session leaders made them feel ‘comfortable’, ‘valued’ and that they were doing a ‘good job’ as parents. Overall, they were felt to provide an impartial ear, allowing parents to open up about the issues they faced.

Parents felt able to ask questions and that their session leaders were able and willing to answer them fully.

Relevant session content and facilitator quality were identified as key strengths of the interventions in the earlier qualitative research as well as in the interviews in the final year of the evaluation. However, parents taking part in the final wave of completer interviews placed less emphasis on the workbooks when outlining strengths of the course than was the case in earlier research.

What worked less well?

Session content and structure

In qualitative interviews there was some variation in how parents felt about the balance of information relating to relationships and information relating directly to parenting. Some intact parents in group sessions noted that they would have liked more focus on parenting, which they felt to be the key sources of conflict and the areas where most impact could be felt. Some separated parents felt that more focus on the relationship between themselves and their ex-partner would have been beneficial, feeling that navigating this relationship was the bigger source of conflict and therefore what they wanted the sessions to address.

One parent had used the sessions as a way to get mediation on areas of conflict with their partner and felt that they were left without adequate tools to work through arguments after the sessions ended.

We could have done with a few techniques. It ended and now we don’t have anyone to referee our arguments. It would have been good to have some sessions with practical advice as well.

Father, Separated, Completer

Session facilitators

Some parents did suggest improvements to the approaches of the session leaders, as they felt they could do more to direct the conversation and contain disagreements to allow the sessions to run more efficiently.

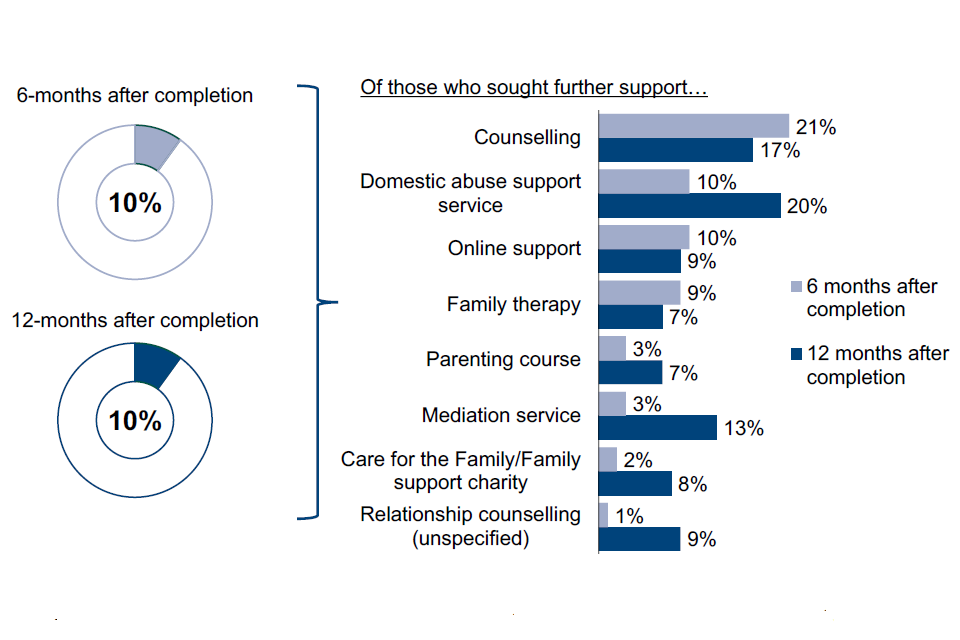

Views on mode of delivery