Reducing Parental Conflict Programme Evaluation: Third report on implementation

Updated 17 April 2023

Applies to England

DWP research report no. 0343

A report of research carried out by IFF research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2022.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence

Or write to the:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our GOV.UK website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published Month April 2022.

ISBN 978-1-78659-385-6

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

Background and methodology

The government wants every child to have the best start in life and reducing harmful levels of conflict between parents - whether they are together or separated - can contribute to this. Sometimes separation can be the best option for a couple, but even then, co-operation and good communication between parents is essential for their children. This is why the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) introduced the Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme. Originally backed by up to £39m until March 2021, with additional funding and an extension of the programme secured until March 2022, the programme is encouraging local authorities across England to integrate services and approaches which address parental conflict in their local provision for families.

Evaluation is central to the RPC programme. Findings from this evaluation will contribute to the wider evidence base on what works for families to reduce parental conflict and will support local authorities and their partners to embed the parental conflict agenda into their services.

This is the third report from the RPC programme evaluation, providing interim findings on implementation from research mostly conducted between January 2021 and December 2021.

The evaluation consists of 3 strands which correspond to 3 programme elements:

- Intervention delivery: To assess how the provision of evidence-based interventions in 31 local authorities, clustered in 4 geographical areas, is implemented and delivered and the impact of the interventions in reducing parental conflict and improving child outcomes.[footnote 1]

- Training: To study whether and how the training of practitioners and relationship support professionals has influenced practice on the ground - focusing on the identification of parents in conflict, building the skills and confidence to work with, or refer, parents in conflict and the overall support available.

- Local integration: To examine to what extent local authorities across England have integrated elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families, how and with what success.

Intervention delivery

Introduction

Eight interventions to address parental conflict were being tested as part of the programme. Interventions were of either a moderate or high intensity and parents were allocated to an intervention based on the level of conflict in their relationship.

Intervention delivery findings

This section draws primarily on data from qualitative interviews with parents who completed interventions, parents who started but did not complete an intervention and those that were referred to an intervention but did not start. Quantitative data references have been taken from an ongoing survey of parents who started but did not complete an intervention.

- Parents starting an intervention displayed varying levels of conflict. Separated parents, regardless of if they completed an intervention or not, were most likely to present with high levels of conflict.

- Typically, parents had more than one source of conflict within their relationship.

- Parents who had completed an intervention were generally positive about the sessions. However, there was evidence that a handful of parents that did not complete an intervention were also positive. These parents commonly thought the sessions had been run well and they were impressed with the practitioners running the sessions, they also appreciated being able to share in a ‘safe space’.

- However, there were some concerns raised by parents that had completed an intervention, as they felt that there were issues with some of the content of the course. The content of the course in some cases was felt to be either not relatable to their current situation, too general to be helpful or lacking in structure. Parents who did not complete an intervention highlighted issues with the interventions, such as the content not being suitable for their level of conflict.

- From the experience of parents, it appeared that there were 4 key elements to delivering the interventions well:

- The approach and demeanour of the practitioner running the sessions.

- Tailoring the content, so it was relevant to the specific background and situation of the parents.

- The use of practical tools and exercises to help parents think in different ways.

- Providing workbooks so parents had a log of what has been covered and future content. This also allowed them to reflect on the course after the sessions.

- Those that had not completed the intervention reported in the survey that they did not complete due to their (ex) partner not wanting to take part in the intervention, or that they felt unable to go without them (25%). This was also reflected in the qualitative interviews, as non-completers and those that did not start often reported resistance from their (ex-) partner as the key reason for not completing the sessions.

- Most parents that completed an intervention felt it had an impact on them. Intact couples seem to have gained the most from the sessions, whereas separated parents tended to feel the intervention had some or a more limited impact.

- However, most parents who did not complete the intervention felt that it had a limited or no impact at all on their relationship. These parents tended to be separated parents. The lack of impact on the relationship appeared to be due to the level of conflict within the relationship. These parents tended to report constantly arguing with their ex-partner or not being in contact at all with their ex-partner before the sessions began.

- Although, positively, most parents (regardless of the impact on themselves) felt they had seen some positive change in their children and their children’s behaviour following the intervention.

Training

Introduction

As part of the RPC programme, the DWP appointed training providers to develop a training package about parental conflict, primarily aimed at practitioners in frontline local authority services. It included modules covering the theoretical context underpinning the programme, identification of, and strategies to address, parental conflict and a specific module targeted at supervisors to enable them to support their colleagues working with parents in conflict. In addition, there was a Train the Trainer workshop intended to build the capacity of those already skilled in training to deliver training about parental conflict and the impacts of it. Following the start of the Coronavirus pandemic, the practitioner training moved online and was delivered via the Virtual Learning Classroom (VLC). The training was previously available in both face-to-face and online formats.

Training findings

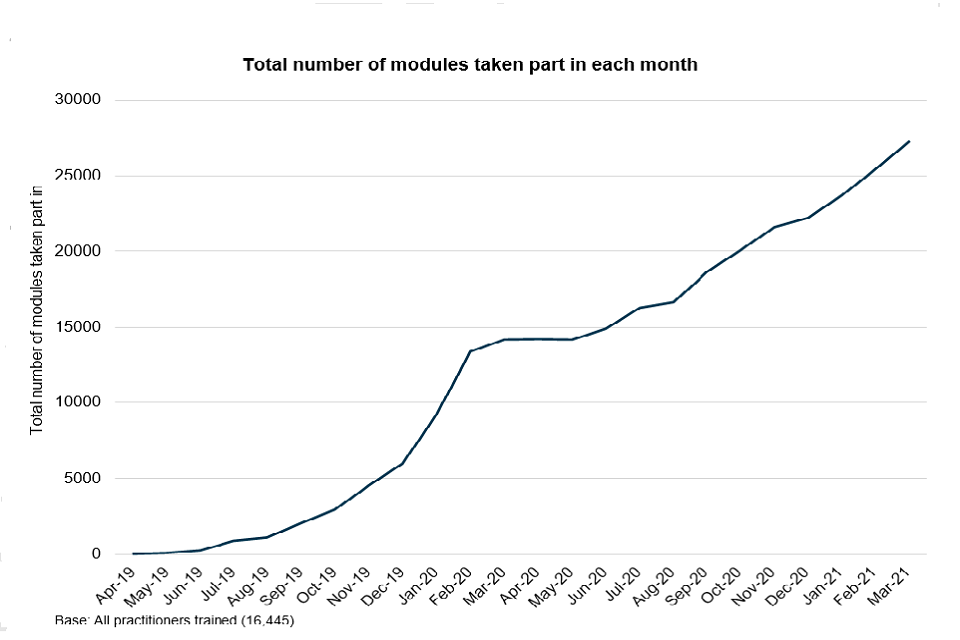

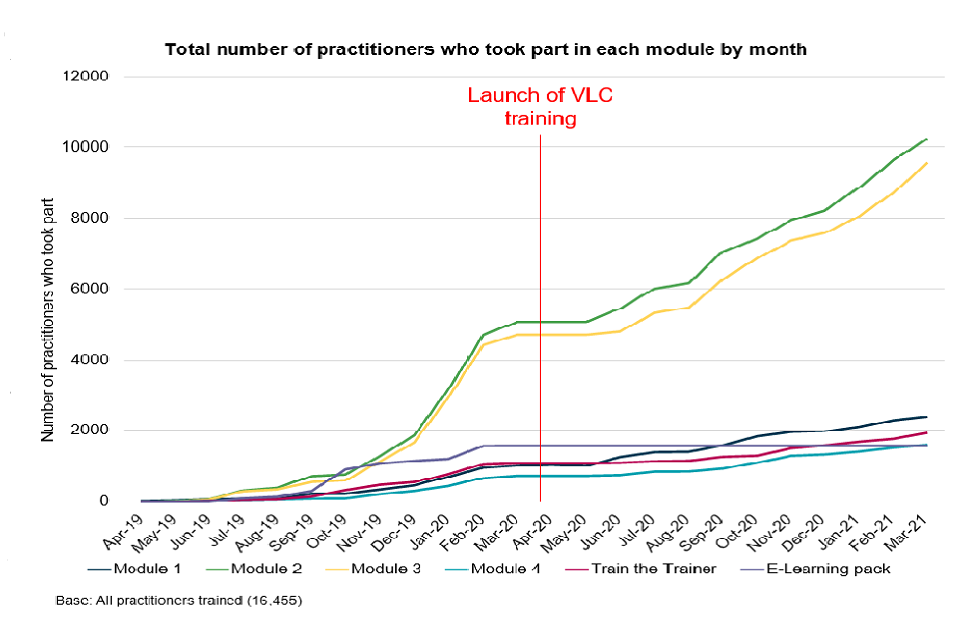

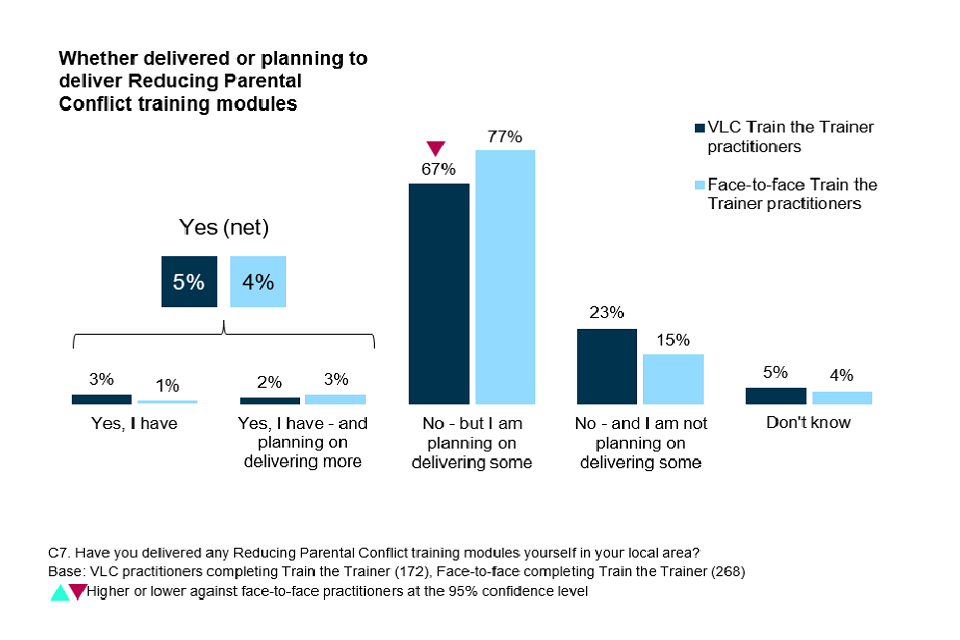

- A total of 7,800 practitioners attended VLC training between April 2020 and March 2021. This was a comparable number to those attending training before the start of the Coronavirus pandemic (8,500).

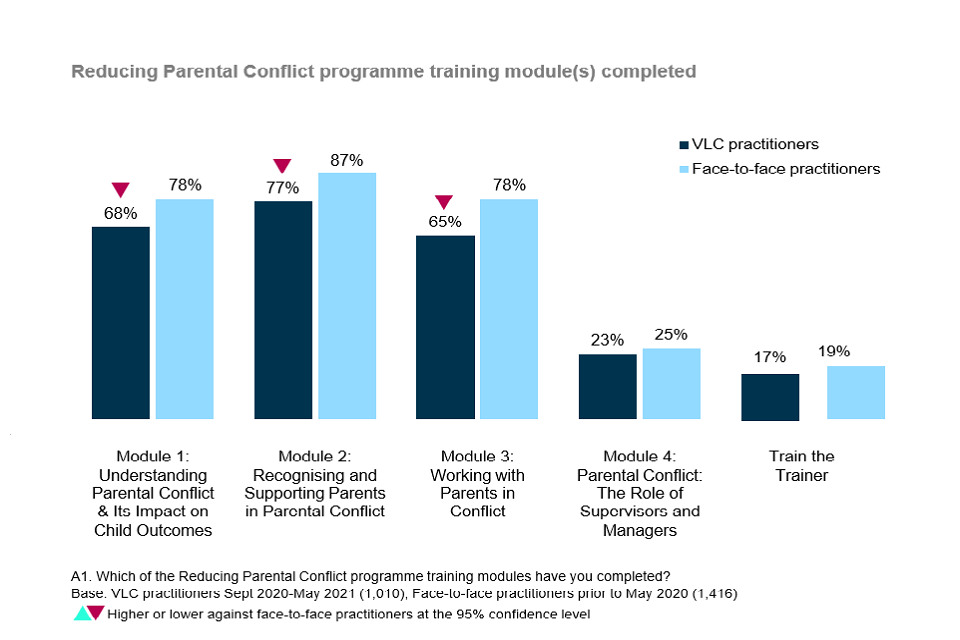

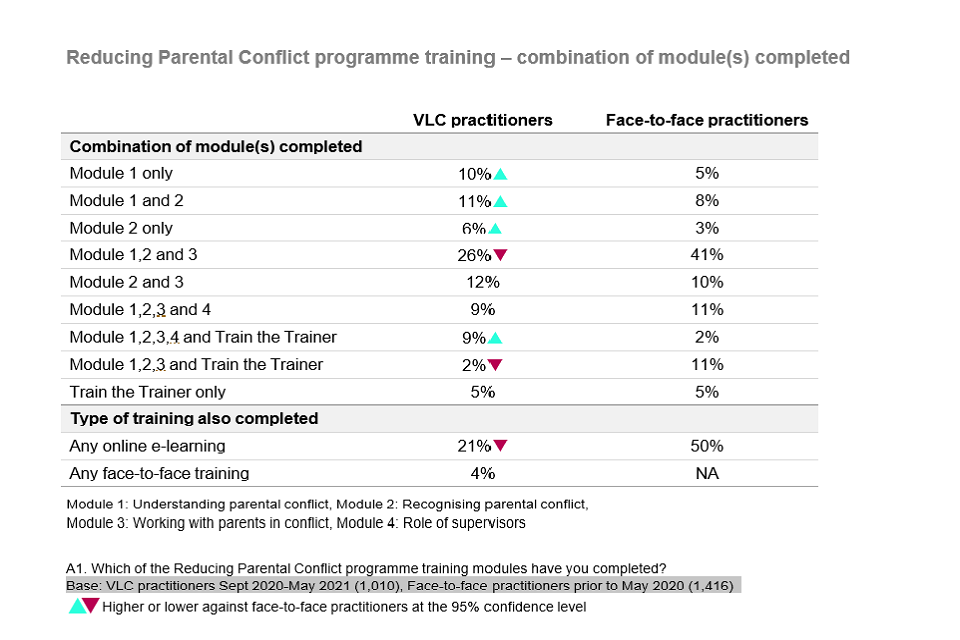

- Practitioners undertaking training through the Virtual Learning Classroom (VLC) took fewer modules than those that completed the training face-to-face. They were also less likely to supplement the training with e-learning.

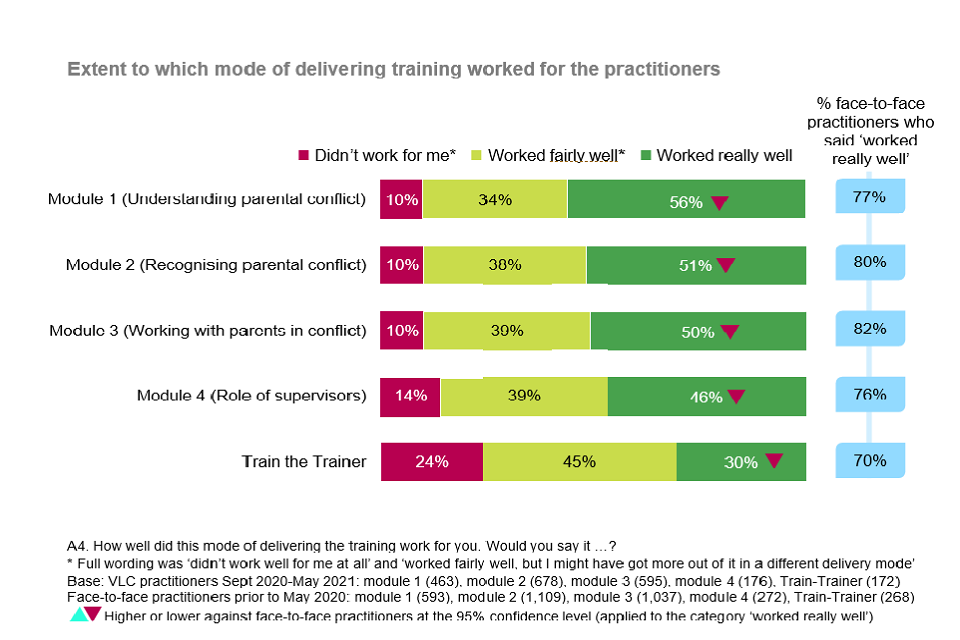

- Some practitioners felt the VLC format worked really well, but generally practitioners felt the VLC mode did not work as well for practitioners as the face-to-face format. This was especially the case for the Train the Trainer module, where over a third (35%) of participants actively said they would be unlikely to engage in the training again in the future.

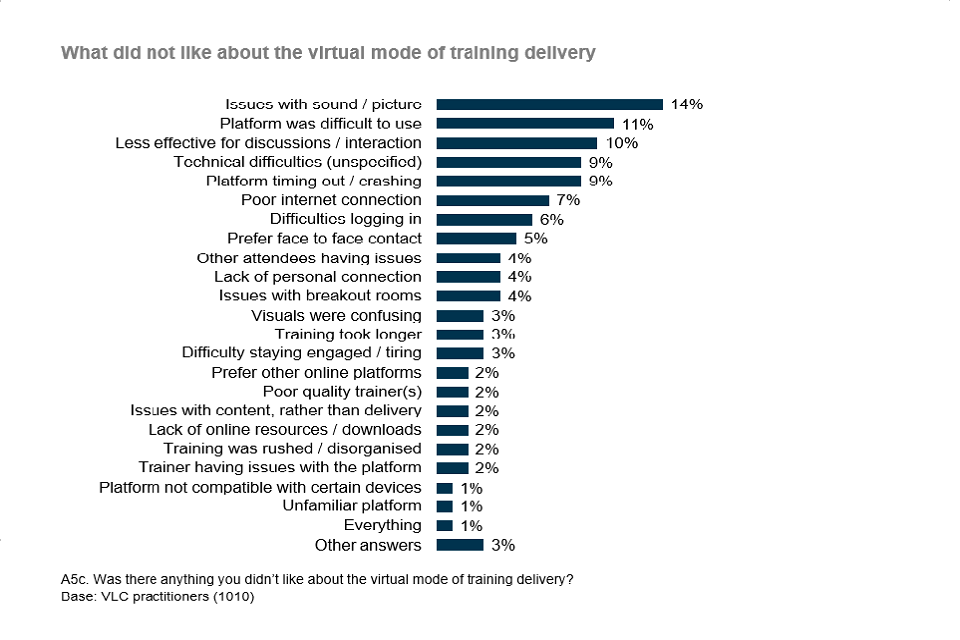

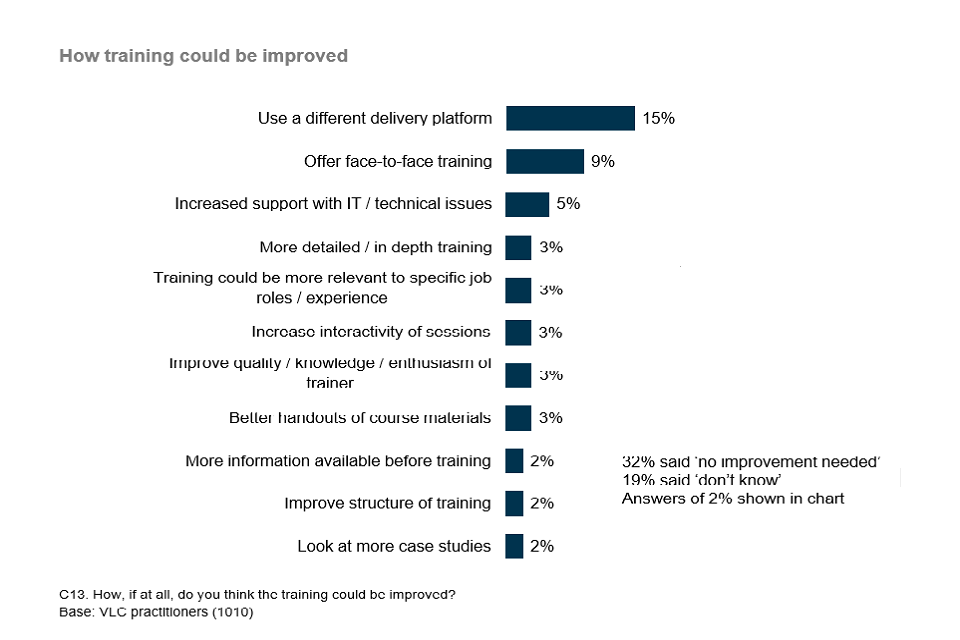

- Practitioners that were not fully satisfied with the mode of delivery wanted a better online platform and more interactive sessions. Although, many wanted the training to be reverted to a face-to-face approach.

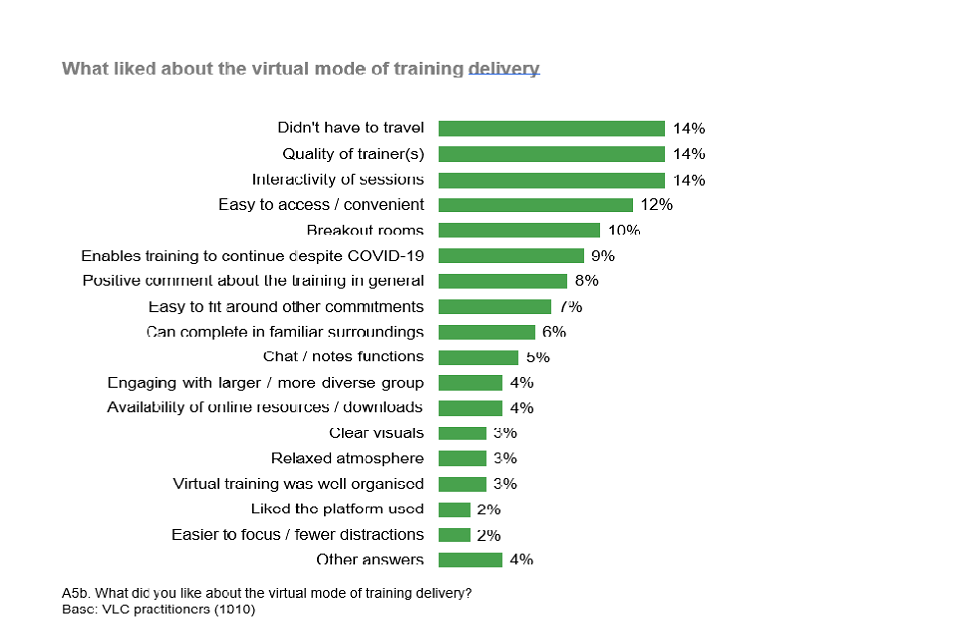

- However, many practitioners acknowledged that the VLC did offer a level of convenience, as they did not have to travel, they could easily fit sessions around other commitments and it fit within Coronavirus pandemic restrictions.

- The content of the VLC training was seen as relevant to practitioners’ work, and most found the training useful. The content and usefulness of some VLC modules were rated more highly than face-to-face delivery.

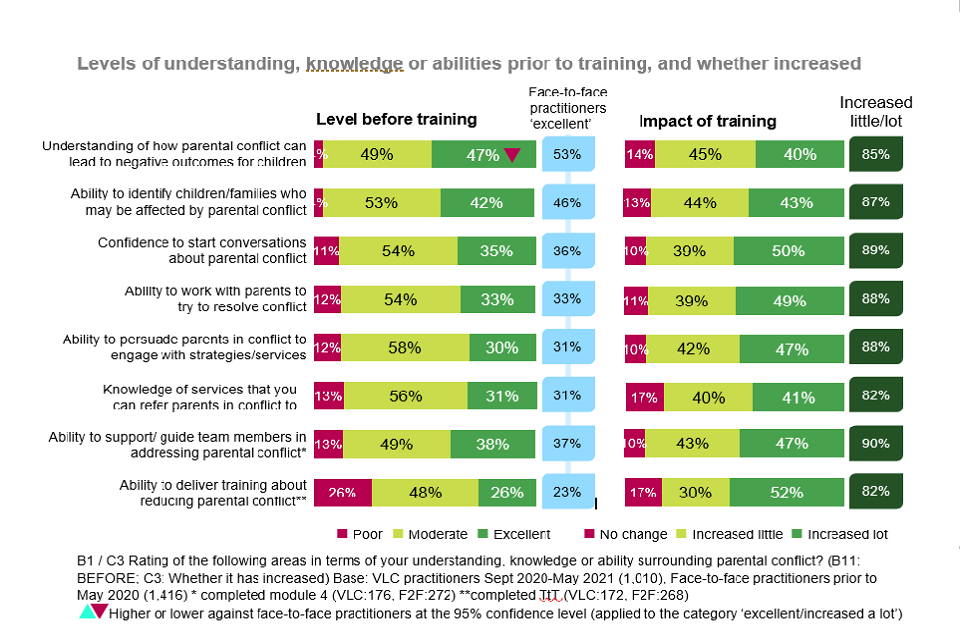

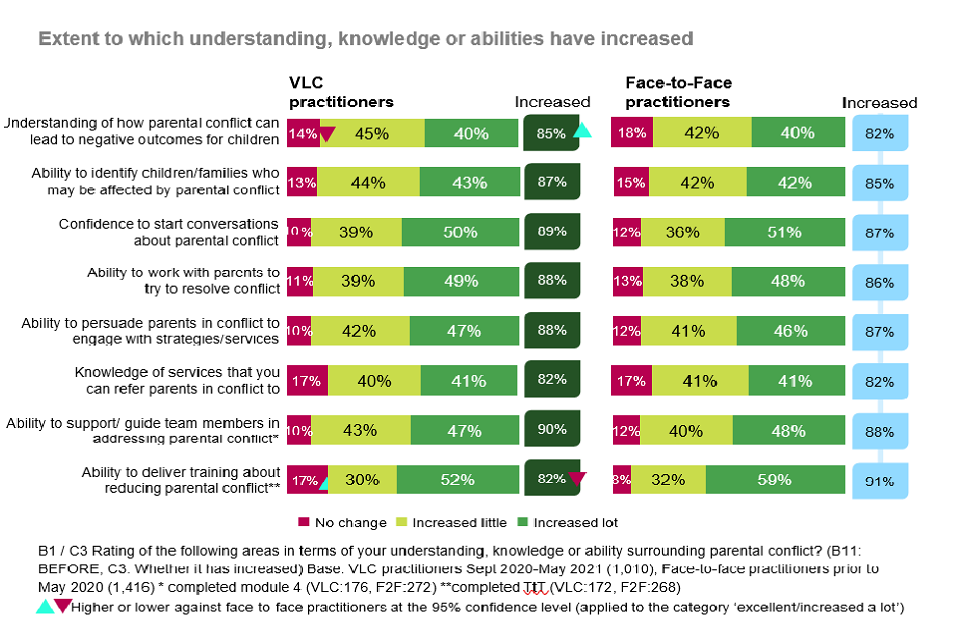

- The VLC training resulted in self-reported improvements in practitioners’ knowledge, understanding and skills around parental conflict. However, there were a few areas where it had less impact: knowledge of services that practitioners could refer parents to, and the ability to deliver training (applicable to the Train the Trainer module).

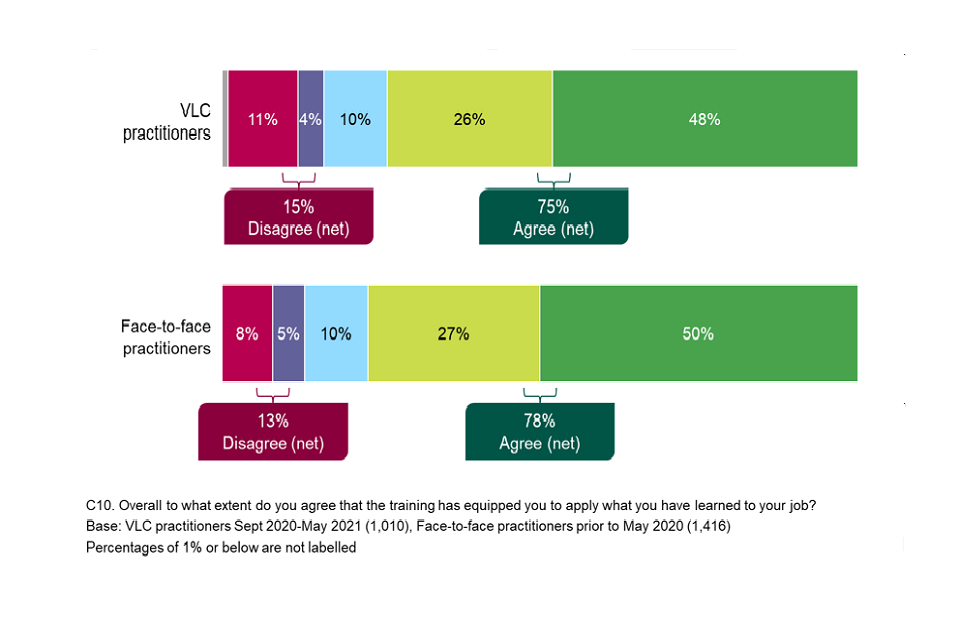

- Most practitioners felt they could apply what they had learnt to their job, although practitioners that had undertaken VLC training were less likely to feel that they could put learning into practice as regularly as those who had completed face-to-face training.

Local integration

Introduction

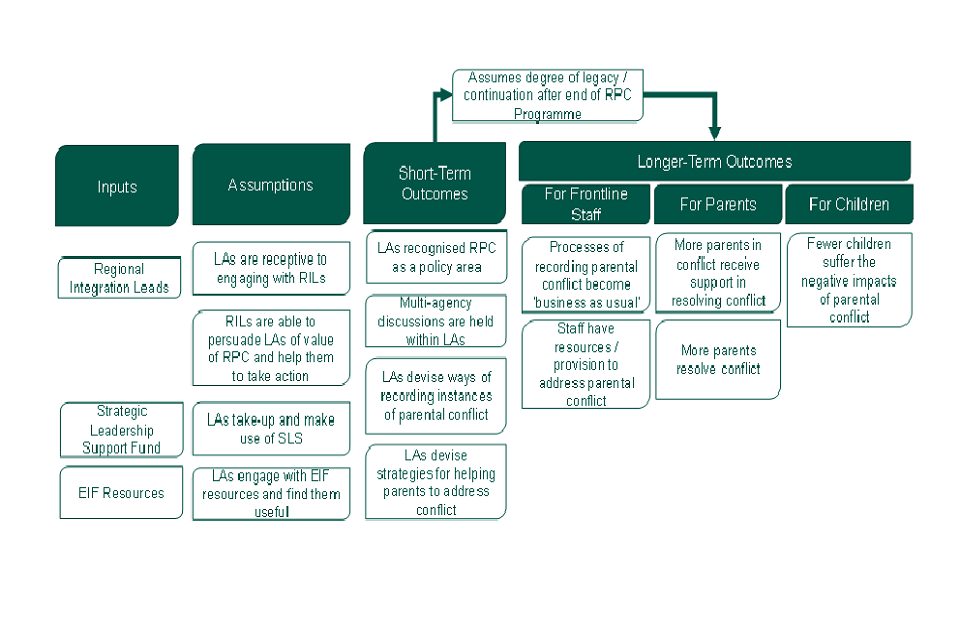

The local integration element of the programme aimed to encourage local areas to consider the evidence base around parental conflict and integrate support for parents in conflict into existing provision.

To support local areas with integration, DWP undertook the following:

- recruited a team of 6 Regional Integration Leads (RILs) to promote the agenda and facilitate knowledge sharing and networking[footnote 2]

- provided a Strategic Leadership Support (SLS) grant for local authorities and their partners to use in ways that best suited their aspirations in respect of reducing parental conflict.

- encouraged access to information made available on the reducing parental conflict online hub hosted by the EIF.[footnote 3]

The evidence provided in this report has come from an online Best Practice Event which was held in December 2021. The Best Practice Event provided a forum for local authorities to discuss what they had achieved to date and how. This related in part to how they had spent the SLS grant provided by DWP.

Local integration findings

- Local authority case studies and conversations amongst local authorities within breakout rooms commonly focused on awareness raising and upskilling practitioners.

- Local authority case studies had created tailored training programmes for their workforce. Local authorities in the breakout sessions also discussed training and mentioned a variety of practitioners that had undertaken training.

- Local authority case studies and conversations amongst local authorities within breakout rooms agreed that multi-agency working was important to the success of the reducing parental conflict agenda.

- Police and health services were commonly noted as key partners to still engage.

- Local authorities in the breakout sessions had developed self-help tools for parents and practitioners. They tended not to have implemented more in-depth provision such as interventions. However, one of the local authority case studies had a six-week intervention on offer for families.

Evaluation

This is the third report from the RPC programme evaluation, providing findings on the research which was mostly conducted in between January 2021 and December 2021.[footnote 4] However, a few research elements were ongoing when the interim 2 report was produced, so these elements have been included within this report.

The following data collections were completed between the production of the second interim report and December 2021 when this report was compiled:

- A total of 1,087 frontline practitioners completed the survey having attended training delivered via the Virtual Learning Classroom (VLC) or via e-learning.

- Thirty in-depth telephone interviews were conducted with parents who had completed an intervention and were currently using the Child Maintenance Service (CMS).

- Forty-eight in-depth telephone interviews with parents who had completed an intervention.

- Twenty in-depth telephone interviews with parents who started an intervention session but did not complete the full course.

- A telephone survey of 152 parents who started the intervention sessions but did not complete the full course. The survey fieldwork is ongoing, but the interviews included within this report were completed between 22nd July 2020 and 16th December 2021.Forty in-depth telephone interviews with parents who were referred to an intervention but did not start the course.

- An online best practice event was held for local authorities. Forty-four attendees joined the online event.

Glossary

| Contract Package Area (CPA) | Delivery of RPC interventions is taking place across 31 local authorities, which are clustered in 4 geographic areas known as Contract Package Areas. These are Westminster, Gateshead, Hertfordshire, and Dorset. |

| Domestic abuse | Imbalance of power or control in a relationship, and one parent may feel fearful of the other. |

| Early Intervention Foundation (EIF) | The Early Intervention Foundation is an independent charity established in 2013 to champion and support the use of effective early intervention to improve the lives of children and young people at risk of experiencing poor outcomes. |

| Frontline Practitioner (FLP) | Local authority colleagues and their partners working with families including those who work for services such as social work, health visiting teams and early years’ services. |

| Parental conflict | Harmful parental conflict behaviours in a relationship which are frequent, intense and poorly resolved can lead to a lack of respect and a lack of resolution. Behaviours such as shouting, becoming withdrawn or slamming doors can be viewed as destructive. Parental conflict is different from domestic abuse. This is because there is not an imbalance of power, neither parent seeks to control the other, and neither parent is fearful of the other. |

| Practitioner Training (PT) grant | The Practitioner Training grant is used to buy spaces for staff in the local authority area to attend bespoke reducing parental conflict training delivered by Knowledgepool. |

| Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme | The Reducing Parental Conflict programme is the subject of this evaluation. It aims to help avoid the damage that parental conflict causes to children through the provision of evidence-based parental conflict support, training for practitioners working with families and enhancing local authority and partner services. |

| Regional Integration Lead (RIL) | There are 6 RILs in England seconded from local authorities to DWP. They are available to provide expert advice and support to local authorities and their partners and maximise the opportunities that the programme presents. |

| Strategic Leadership Support (SLS) grant | The SLS grant is used to help local authorities and their partners to raise the profile of parental conflict and fund activities to integrate reducing parental conflict into their provision. |

Chapter 1 Introduction, background, and methodology

This chapter outlines the background to the project and provides an overview of the evaluation methodology. It also provides details on the elements of the evaluation that have been conducted between January 2021 (when the second interim report was produced) and December 2021. However, a few fieldwork elements were ongoing when the interim 2 report was produced, so these elements have been included within this report.

Context

Parents play a critical role in giving children the experiences and skills they need to succeed. However, studies have found that children who are exposed to parental conflict can be negatively affected in the short and longer terms.[footnote 5]

Disagreements in relationships are normal and not problematic when both people feel able to handle and resolve them. However, when parents are entrenched in conflict that is frequent, intense, and poorly resolved it is likely to have a negative impact on the parents and their children. It can impact on children’s early emotional and social development, their educational attainment and later employability – limiting their chances to lead fulfilling, happy lives.

The government wants every child to have the best start in life and reducing harmful levels of conflict between parents – whether they are together or separated – can contribute to this. Sometimes separation can be the best option for a couple, but even then, continued co-operation and communication between parents is better for their children. This is why DWP introduced the Reducing Parental Conflict programme. Originally backed by up to £39m to March 2021 with additional funding and an extension of the programme secured until March 2022. The programme is encouraging local authorities across England to integrate services and approaches which address parental conflict into their local provision for families.

The RPC programme seeks to address conflict below the threshold of domestic abuse. Where there is domestic abuse there will be an imbalance of power, control and one parent may feel fearful of the other. If domestic abuse is suspected or identified, a pathway of more specialised support should be offered in place of the RPC programme, and appropriate safeguarding measures implemented.

Evaluation is central to the Reducing Parental Conflict programme. Evidence from the evaluation of the programme will contribute to the wider evidence base on what works for families to reduce parental conflict and will support local authorities and their partners to embed the parental conflict agenda into their services.

This is the second evaluation report in the series of interim reports, which provides findings on programme implementation part way through the delivery period.

Delivery of the Reducing Parental Conflict programme

The programme is designed to increase the support that is available and provided to disadvantaged parents in conflict through different elements of activity.

- Intervention delivery: Testing evidence-based interventions that are designed to reduce parental conflict and improve child outcomes.

- Training: Provision of training for multi-agency practitioners such as Family Support workers, teaching assistants or Police officers to increase understanding of the parental conflict evidence base, enhance their confidence and ability to identify and discuss parental conflict with parents and apply the evidence-base in family support practice. Provision for supervisors and managers to support their staff in integrating reducing parental conflict is also being delivered.

- Local integration: Provision of funding and support to integrate elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families.

- A Challenge Fund to test innovative activity, including digital support (which is out of scope of this evaluation).[footnote 6]

- A package of measures, jointly funded with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and Public Health England (PHE) to improve outcomes for children of alcohol dependent parents.

Evaluation

In January 2019 DWP commissioned a large scale, multi-method external evaluation of the programme. DWP analysts will conduct a complementary impact evaluation.

The external evaluation is largely a process evaluation through which the range of activities supported by the programme are being examined to build the evidence base about what works to reduce parental conflict. It is anticipated that this will support local authorities and their partners to embed the parental conflict agenda effectively in their services.

Mirroring the programme design, the evaluation covers the delivery of interventions, training, and local integration. The main objectives for each element of the evaluation are:

- Intervention delivery: To assess how the provision of evidence-based interventions in 31 local authorities, clustered in 4 geographical areas, is implemented and delivered and the impact of the interventions in reducing parental conflict and improving child outcomes.[footnote 7]

- Training: To study whether and how the training of practitioners and relationship support professionals has influenced practice on the ground - focusing on the identification of parents in conflict, building the skills and confidence to work with, or refer, parents in conflict and the overall support available.

- Local integration: To examine to what extent local authorities across England have integrated elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families, how and with what success.

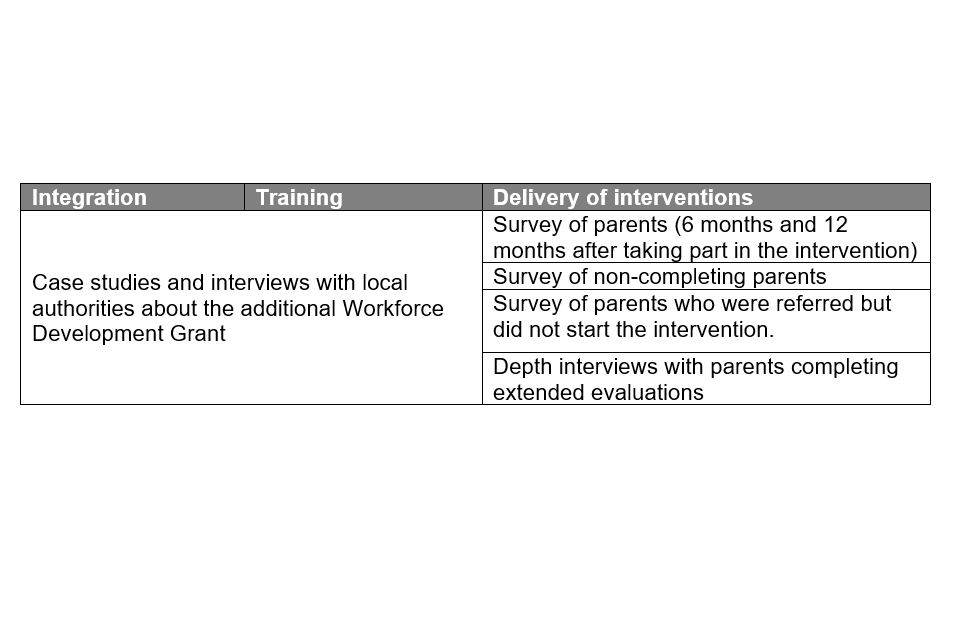

The table below shows the different evaluation components that were ongoing or completed at the time of this report. All elements included in Table 1.1 are discussed in this report.

Table 1.1 The RPC programme evaluation elements completed or ongoing at the time of this report

The evaluation components in Table 1. 2 had not been completed at the time of this report. These elements will be completed and reported on in the future.

Table 1.2 The RPC programme evaluation elements to be completed in the future and included in future reports[footnote 8]

Methodology

This section provides detail on the approach taken for each of the evaluation elements covered in this report.

Virtual Learning Survey

Following the start of the Coronavirus pandemic, practitioner training using the modules developed for the RPC programme moved online (previously it was available in both face-to-face and online formats). Around 8,000 frontline practitioners were contacted between November 2020 and May 2021 as they had registered to complete one of the online modules. A total of 1,087 frontline practitioners completed the survey having attended training delivered via the Virtual Learning Classroom (VLC) or via e-learning.

Intervention Delivery

Several sets of qualitative interviews were conducted among parents who had attended one of the RPC interventions. Interviews lasted around 45 minutes to an hour each and covered experiences and impacts of the intervention sessions and reasons behind parents starting or not starting the sessions.

Qualitative interviews with Child Maintenance Service (CMS) users

Thirty in-depth telephone interviews were conducted in May and June of 2021 with parents who had completed an intervention and were users of the Child Maintenance Service.

Qualitative interviews with completers

Forty-eight in-depth telephone interviews with parents who had completed an intervention were conducted, including a mix of intact couples, and separated parents (some CMS users and some not using CMS). Beginning in February 2020, these interviews continued up until May 2021.

Qualitative interviews with those that did not complete the sessions

Twenty in depth telephone interviews were conducted with parents who started the intervention sessions but did not complete the full course. These interviews took place in October and November 2021.

Qualitative interviews with those that did not start

Forty in-depth telephone interviews with parents who were referred to an intervention but did not start taking part were conducted in June and July 2021.

Non-completer survey

A telephone survey of 152 parents who started the intervention sessions but did not complete the full course was also conducted. The interviews included in this report were completed between 22nd July 2020 and 16th December 2021, although these telephone surveys are ongoing.

Best Practice Event

An online best practice event was held in December 2021 which aimed to showcase reducing parental conflict good practice. The event included four 15 minutes presentations from local authorities with each focussing on a specific stage of the RPC implementation journey aligning with the Early Intervention Foundation (EIF) planning tool which supports the programme. Presentations were followed by a short question and answer session. Participants were then broken out into breakout groups to discuss key themes and topics covered on the day, how these might apply to the work of other local authorities and any other learnings that can be taken away. All local authorities involved in the programme were invited to attend the event. Forty-four attendees joined the online event on the day.

Chapter 2 Intervention delivery

This chapter explores the experiences of parents referred to the interventions being provided as part of the RPC programme. It covers the experiences of parents who completed an intervention; those who began but did not complete an intervention; and those who did not start an intervention, despite being referred onto it.

Introduction to intervention delivery

Testing of interventions through the RPC programme aimed to deliver evidence about what works to reduce parental conflict and improve children’s outcomes.

Eight different interventions were tested as part of the programme (further details on these is outlined in Table 2.1). These were designed to be delivered face-to-face but were quickly adapted to be delivered virtually in response to the Coronavirus pandemic. Some of these had a promising evidence base supporting their efficacy in the UK, but not necessarily for all family types, for disadvantaged families or for different delivery methods. Others had been successful in non-UK settings but had not been tested in the UK. In all cases the interventions being implemented presented significant opportunities for learning.

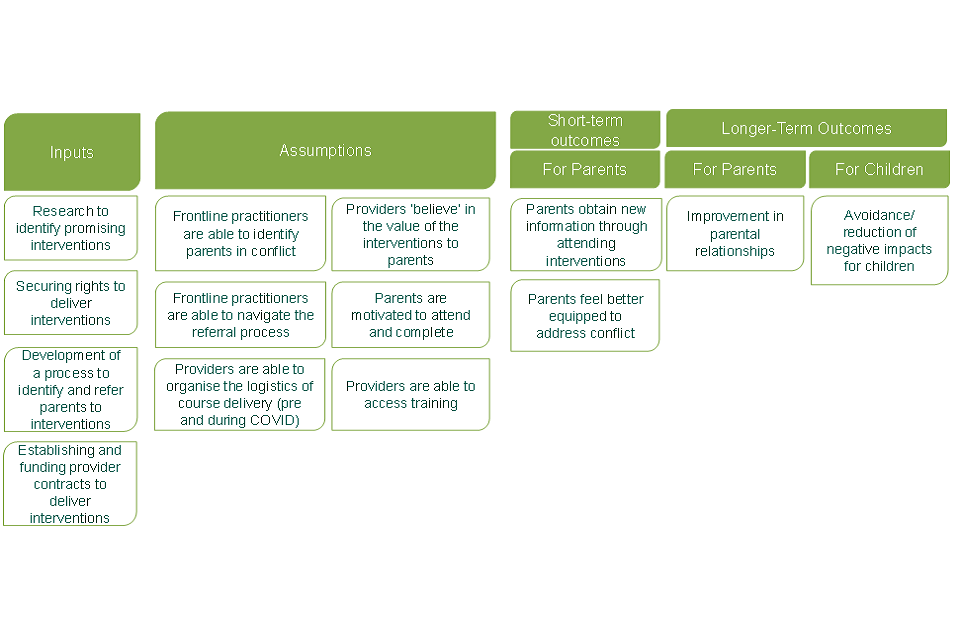

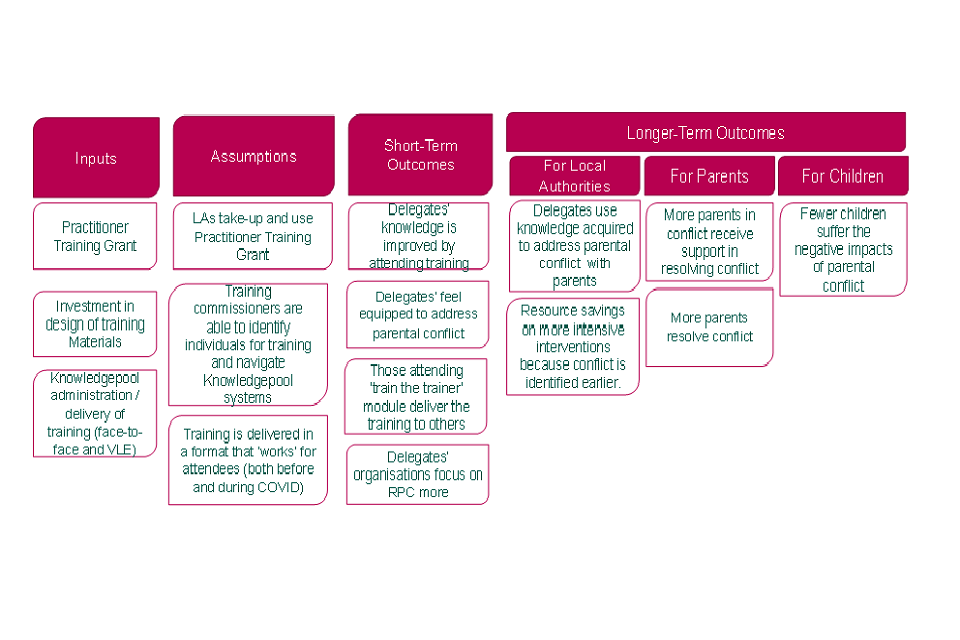

The interventions aimed to achieve a number of short-term and longer-term outcomes for both parents and children as set out in Figure 2.1, based on a number of inputs and assumptions around provider delivery. The research covered in this report explores some of the assumptions and short-term outcomes in this model.

Figure 2.1 Logic Model for Interventions delivery

Interventions were of either a moderate or high intensity. Parents were allocated to an intervention based on the level of conflict in the relationship. This was identified via an assessment tool developed for the programme by subject matter experts and known as the Referral Stage Questionnaire (RSQ). This was administered to parents by a frontline practitioner working with the family. It consisted of a range of established assessment scales to identify the types and levels of conflict parents were experiencing. It examined the mechanisms through which child outcomes were affected, and the features of an inter-parental relationship that had been shown to impact on children’s outcomes. If either parent scored high for conflict, both parents were offered a high intensity intervention. Flexibility was granted with regards to the intensity of intervention in early 2020, enabling providers to offer parents either high or moderate interventions in certain circumstances, regardless of RSQ outcome.

Some interventions were delivered in a group setting, some as couple sessions and some on an individual basis. Couples who remained in a relationship as well as those who had separated were eligible. Existing and expectant parents were eligible.

The full list of interventions is shown below. Delivery of these interventions continued throughout the Coronavirus pandemic and lockdown with the majority switching to digital delivery over Teams or Zoom; this will be covered in more detail later in the chapter.

Table 2.1 Interventions being delivered

| Intervention Name | Brief Description | Method of delivery | Target group | Length of delivery | CPA | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4Rs 2Ss Family Strengthening Programme | Curriculum-based practice designed to strengthen families, decrease child behavioural problems, and increase engagement in care. It focuses on evidence-informed parts of family life that have been empirically linked to youth conduct difficulties. | Groups of 12-20 parents | Both intact and separated couples with children aged 7-11 | 16 weeks | Hertfordshire | High |

| Family Check Up | This involves 3 stages: an initial interview, family and child assessment, and feedback. The second stage involves the delivery of Everyday Parenting (EDP), which is a behavioural parenting intervention tailored to meet specific needs. | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | Both intact and separated couples | 3-4 sessions of 50-60 minutes | Dorset Westminster Gateshead Hertfordshire |

Moderate |

| Enhanced Triple P | This is a targeted selective intervention, which aims to address family factors that may impact upon and complicate the task of parenting, such as parental mood and partner conflict, and problem child behaviours. | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | For both intact and separated couples | 4 modules delivered to families in 3 to 8 individualised consultations (8-12 hours) | Westminster | High |

| Family Transitions Triple P | Designed as an intensive intervention for parents experiencing difficulties as a consequence of separation or divorce, it focuses on developing skills to resolve conflicts with former partners and how to cope positively with stress. | Groups of approximately 8 parents (separated parents are encouraged to attend different sessions) | Separated couples only | 5 sessions lasting 2 hours each | Dorset Westminster |

High |

| Mentalisation Based Therapy – Parenting under pressure | Aims to help couples, whether separated or together, experiencing high levels of inter-parental conflict gain more perspective in order that they can start to put the needs of their children first. It is based on a model which comprises an initial phase of preparation and assessment, meeting with each parent separately. | One practitioner delivers sessions to intact couples. With separated couples each parent completes sessions with a separate practitioner. In rare cases the parents can complete the final session together with both practitioners. | For both intact and separated couples | 10 sessions of therapeutic work | Gateshead Hertfordshire |

High |

| The Incredible Years, including Advanced Programme | The focus is on parents’ and children’s communication and problem-solving skills, knowing how and when to get and give support to family members and recognising feelings and emotions. It’s a group programme, basic is approximately 16 weeks with an additional 8 for advanced. | Group sessions of 12-20 parents | Couples and separated co- parents with children aged 4-12 years | 12-20 sessions as part of the ‘Basic’ course, with an additional 9-11 session for ‘Advanced’ (average of up to 20 weeks) | Dorset Gateshead |

High |

| Parenting when Separated | Drawing on international long-term evidence, it highlights practical steps parents can take to help their children cope and thrive as well as coping successfully themselves, where the parents are preparing for, going through, or have gone through separation or divorce. | Group intervention delivered by 2 practitioners to groups of 12 participants | Separated couples only | 6-week course of 2.5-hour sessions | Gateshead Hertfordshire |

Moderate |

| Within My Reach | This is a targeted selective intervention, for low-income single parents, who may or may not be in a relationship. The intervention therefore targets relationship outcomes in general, rather than focusing on parenting or parental conflict. It covers 3 key themes: Building Relationships, Maintaining Relationships and Making Relationship Decisions | Delivered in a group to individuals (not couples) | Separated couples only | 15 sessions, each lasting 1 hour | Dorset Westminster |

Moderate |

Emerging findings

This section draws primarily on data from qualitative interviews with parents who completed the interventions; parents who were referred to an intervention but did not start; and parents who started an intervention but did not complete it. Where quantitative data is given, this is drawn from the survey of parents who started but did not complete an intervention.

- Parents came to interventions with varying levels of conflict, from no conflict through to accusations of domestic abuse. Separated completers and non-completers were most likely to present with high levels of conflict.

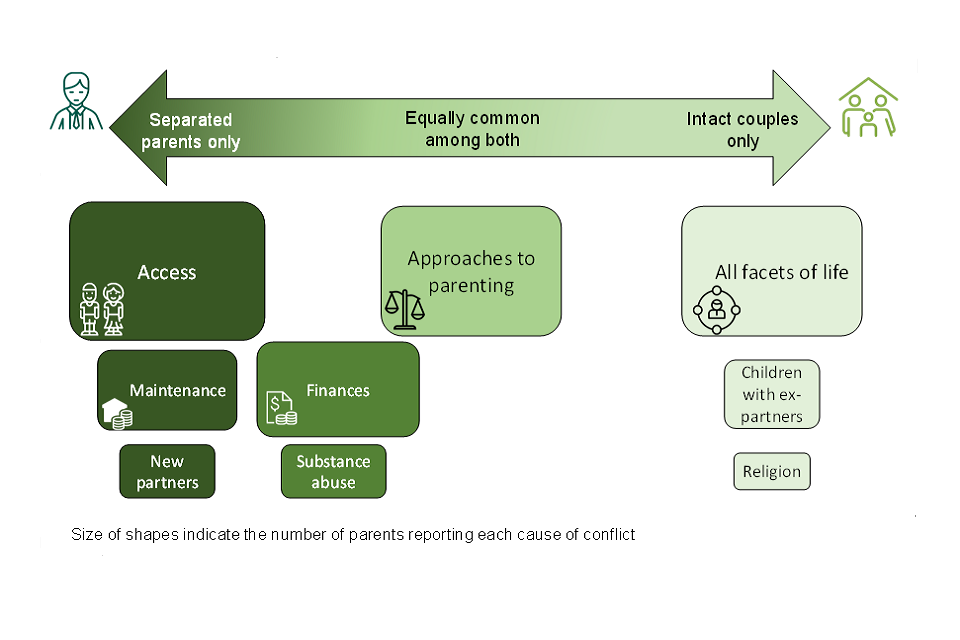

- Parents, typically, did not present with a single cause of conflict but many. These included: approaches to parenting; finances; and access, which tended to be the primary source of conflict for separated parents. Intact couples commonly indicated that they were arguing about most facets of their life.

- Often, parents were motivated to participate by desperation for something to alleviate the conflict with the other parent. This was particularly common for separated completers.

- Some parents were motivated to attend by the impact of their conflict on their children. This group was primarily comprised of completers referred by their child’s school and separated non-completers.

- Generally intact and separated completers were positive about the sessions they took part in, as were some non-completers. Overall positivity about the interventions focussed on sessions being run well; the practitioners running the sessions; and being able to share in a ‘safe space’.

- Completers mentioned the practical tips provided around understanding the other person’s point of view and having a third person’s input to point out how the misunderstanding may be occurring, as particular strengths of the sessions.

- Positivity among non-completers commonly focussed on being able to discuss difficult issues in a safe environment.

- Some parents outlined issues with the course content. For completers, this was with the content of specific interventions that felt unrelatable, too general or lacking in structure. Where non-completers outlined issues with course content, it tended to be because they felt it was not appropriate to their situation. In a small minority of cases, parents (completers and non-completers) mentioned that they felt they had experienced domestic abuse, rather than conflict within the relationship. Intervention providers have safeguarding and procedures in place to appropriately support parents who disclose that they have experienced domestic abuse. However, it is difficult for this piece of research to confirm if the safeguarding and procedures took place in the instances raised by these parents.

- Frustrations with the format focussed on two issues: separated parents who were not getting enough of their ex-partner’s perspective (either because their ex-partner was not attending an intervention, or they were attending separate sessions and felt that the practitioner should be bringing their perspectives to each other more); or some disappointment with online delivery rather than face-to-face sessions.

- Parents who completed the course generally felt positive after the sessions, which was attributed to the sessions providing the ‘safe space’ where parents could openly talk. The small proportion of completers who did not feel positive after the sessions were generally separated parents, and this was due to feeling stressed and emotionally drained after the sessions.

- Non-completers more commonly came away from the sessions feeling less positive. This was typically because they were frustrated that the sessions had not really given them what they needed.

- Non-completers most commonly reported not completing because their (ex) partner did not want them to or they felt unable to go without them (25%). This was reflected in the qualitative interviews, as non-completers and non-starters often reported resistance from their (ex-) partner as the key reason for not completing the sessions, and some non-completers felt the sessions caused additional conflict with their (ex-) partner.

- Practical issues, such as those caused by the pandemic (7%), attending around work (11%), and arranging childcare (9%) were also commonly outlined by both non-completers and non-starters.

- For some non-completers, the sessions were simply not felt to be appropriate, either because the level of conflict in their relationship was too severe or because they faced specialised issues that the sessions could not address. However, some non-completers did not complete because their needs had been met by the sessions they did attend (7%).

- Overall, the interventions had a good impact on most parents, with the greatest positive impact felt by intact couples. Separated parents tended to feel that there had been some impact or a limited amount of impact, whilst most non-completers tended to feel that there had been limited or no impact.

- The extent of the impact appears to be a consequence of the level of conflict within the relationship. Parents who reported limited or no impact were either arguing continuously or they had no contact at all with their ex-partner before sessions began. Those with high impact were either intact or were separated parents not using the child maintenance service (CMS), who were less likely to come with high levels of conflict than those using CMS.

- Most parents (regardless of the impact on themselves) felt they had seen some positive change in their children and their children’s behaviour following the intervention.

Findings explained

The journey to the RPC programme

Levels of conflict

High levels of conflict

The highest levels of conflict, among all groups of parents (completers, non-completers and did not starts), were typically found in separated parents. Many were involved in ongoing legal disputes, while a small minority felt they had experienced domestic abuse, mentioning physical assault, coercive control and stalking. This was most common among (separated) non-completers.

It was really explosive and toxic, a lot of arguments, it wasn’t good at all.

Female, Separated, Completer

He would send me nasty messages, gaslighting me…It was mental abuse, it was put downs.

Female, Separated, Non-Completer

Most non-completer parents were reporting either high levels of conflict or little to no communication.

Little or no communication

Some separated parents came to the sessions at the point where there was little to no communication with their ex-partner except through lawyers or court mandated routes. Often these parents felt that this lack of contact was actually the best route to limiting conflict, as any contact tended to result in arguments.

Moderate to low levels of conflict

A minority of separated parents exhibited low levels of conflict, including relatively civil relationships in some cases with many years of co-parenting behind them.

Intact couples (from all parent groups) tended to be arguing frequently (typically once or twice a week) with shouting, name calling, the silent treatment and periods where they would not communicate at all being reported. Some described them as ‘disagreements’ rather than arguments. These disagreements led to unresolved tension and resentment within the home. In a few cases arguments had become heated enough for police to become involved.

One non-completer reported little or no conflict in their relationship (a factor in them not completing the intervention) but no other non-completers fell into the low level of conflict category.

Causes of conflict

Both separated and intact couples reported a range of causes of conflict. Typically, there was not a single cause but many, and it is worth noting that most intact couples indicated that they were arguing about most facets of their life.

Figure 2.1. Access was the most common cause of conflict among separated parents

Access

Among separated parents, disagreements over access tended to be the primary source of conflict.

Typically, one parent had limited access to the child/children (e.g., once, or twice a week or every other weekend) which caused tension within the relationship. Those who did not mention access as an issue tended to have arrangements with regular and frequent visitation or joint custody of their child/children.

[Our relationship] was pretty bad because I wasn’t seeing the kids as much as I wanted to… there were constant arguments between me and my ex.

Separated, Completer

Maintenance

Parents commonly pointed to maintenance as a source of conflict, typically by separated parents using CMS.

These parents did not typically point to child maintenance as the central source of conflict. It was often an issue for these parents, but it was almost always seen as a secondary issue to access for one of the parents. However, in a few cases child maintenance was a key point of conflict.

Where child maintenance did cause conflict, this was because payments were missed or late, or because the receiving parent felt they were receiving the incorrect amount.

Finances (not including maintenance)

Finances were a common source of conflict among separated parents.

In some cases, this was the result of their ex-partner having run up debt against shared assets which they were reluctant to help address. For others it was a reluctance to financially support their child(ren).

For some separated parents, conflict over finances dated back to when they were together, including issues around hiding money and generating significant debts. One separated parent felt that their ex-partner had used money as means of control over them in their relationship.

He’s caused a lot of debt, financial worry and stress for me in the mortgage of the house I’ve still got.

Female, Separated, Non-Completer

Most separated parents who did not use CMS did not discuss finances as a point of conflict as frequently as CMS users. Where it was cited, it was either a continuation of an issue that began when they were together or along with many other issues. However, it is important to note that the discussion guide for CMS users was more focused on finances due to the emphasis around their use of CMS.

Separated parents who did not start did not mention finances as a point of conflict.

Approaches to parenting

Both separated and intact couples often cited issues around approaches to parenting as a cause of conflict. This included a wide range of issues, varying from the more common issues of how and when to discipline children to more specific issues, such as how to support a child with learning difficulties.

Wanting to turn up and pick her up when he suddenly realised, he wasn’t doing anything that day, regardless of whether I had plans with her or not. Wanting to keep her out late, just things that were not appropriate for her.

Female, Separated, Did Not Start

Substance abuse

Occasionally parents reported conflict caused by substance abuse. This was most common amongst separated parents, but a few intact couples also reported this as an issue.

For most participants that mentioned substance abuse issues, this was their partner abusing alcohol but issues with cocaine, heroin and cannabis were also reported. These parents found their partner / ex-partner exhibited erratic behaviour that made them difficult to rely on and trust as a parent.

Once she drinks that’s it … she just fires on all cylinders.

Male, Separated, Did Not Start

Other

Other issues mentioned by only a few parents included: children from past relationships and how parents related to them; tension with new partners, who could exhibit jealousy or hostility towards their partner’s ex-partner; and religious differences between parents.

Pathways to Child Maintenance Service (CMS)

Among the parents who used the Child Maintenance Service (CMS) to make child maintenance arrangements, there typically existed a gender divide on who paid and who received payments. Fathers were almost always the paying parent and it was most commonly the mother, as the recipient that engaged the CMS. Most parents who paid or received child maintenance through CMS had tried family-based arrangements for a period of time before issues in these pushed them to engage the CMS. The time before these collapsed ranged from a couple of months to several years.

Parents displayed two motivations for engaging the CMS. First was a means for extracting, what one parent felt to be, the correct (higher) amount of child maintenance from the other. This group were frustrated with the payments received from their ex-partner and felt CMS was a route to ensuring they received, what they felt, was a fairer amount.

He was withholding money and hiding money and should have been paying more than he was and it was to make him more consistent.

Female, Separated, Did Not Start

The second motivation was as a way of ensuring distance from their ex-partner and preventing another source of conflict. For these parents, contact with their ex-partner, on any subject, resulted in conflict so removing the need for direct contact over child maintenance payments was seen as an avenue to reducing conflict.

I said we’d do it through child maintenance because I don’t want the hassle, and again it was getting another intermediary between me and him.

Separated, Completer

Parents who were receiving versus those who were paying maintenance tended to present differing views on why the CMS were engaged. The receiving, typically female, parents often presented the case that they engaged the CMS because their partner was underpaying or missing payments. While the paying, typically male, parents claimed that their partners engaged the CMS simply to take more of their money. This highlights the high level of conflict that many came to when they engaged the CMS.

Referral pathways

A wide range of routes into RPC programme interventions were reported by parents, demonstrating the value of raising awareness and providing skills to start conversations about parental conflict among a range of different types of frontline practitioner.

Parents who completed commonly reported referral pathways to the RPC programme beginning with their child’s school. This was typically because their child had mentioned conflict between their parents at school or because of a noticeable change in the child’s behaviour.

[When the school spoke to them] I felt like I was failing at being a parent.

Female, Separated, Completer

However, it was more common for completers who used CMS to find out about the intervention through the court system, possibly reflecting the higher levels of conflict among this group. For some this was either advised by the judge or their legal representative, while for some parents it was through CAFCASS.

Family workers; social services; mental health workers (both adult and child); health visitors; therapists were other routes cited by parents who completed.

For non-completer parents, social and child services were the most common routes for referral. This group tended to be experiencing high levels of conflict, which was picked up on by social workers or child support workers.

Things were toxic when we were referred to the sessions, it was through social services we got referred to the sessions.

Female, Intact, Non-completer

Other non-completers had self-referred. These parents were struggling to address conflict with difficult ex-partners or challenging children and were desperate for some form of support to help them.

A small minority of non-completers also mentioned referrals via the police and nursery staff.

Parents who did not start often struggled to remember how they were referred. Although the most common recollections were that someone from social services referred them. Others recalled a variety of referral pathways - by their doctor, by a judge, by family and children’s support workers and by mental health support workers.

Separated parents who did not start also mentioned their child’s school, children’s workers, and self-referrals after learning about the programme via word of mouth.

It could have been one of the Social Workers, or my doctors or someone from MIND.

Female, Separated, Did Not Start

Motivations for taking part

Discussions around motivations for parents attending demonstrated a clear need for help and support around managing conflict. However, there were some indications of a need to manage expectations about what the course could achieve more carefully.

Alleviating conflict with the other parent

Many parents were desperate for something to help alleviate the conflict and tension with their partner or ex-partner. This was particularly the case for separated completers, for some of whom the tension and conflict with their ex-partner had taken a significant toll on them mentally. Those who had limited access to their children (typically fathers) took part in the hope that it would help increase the access they had to their children. However, a few of those who were in court proceedings were suspicious of their ex-partner’s motivations (typically mothers) and suggested that their ex-partner had only participated to ‘look good’ to the court.

The desperation for something to help their situation was present among many non-completers, including both separated and intact couples. For these parents, their desire to find any support with their challenging circumstances might have been one factor that drove them on to an intervention that ultimately was not suitable.

The wellbeing of their child(ren)

For completers who had been referred through their child’s school, hearing the impact on their children made them realise that the conflict was not just affecting them, and this motivated them to take part in the intervention. A small minority of these parents were sceptical about whether the sessions would actually help but came round once the emphasis on their child’s wellbeing was explained.

Despite not having been referred by their child’s school, a large minority of non-completers also mentioned the impact of the conflict on their child’s wellbeing as motivation for taking part. These, typically separated, parents recognised that the conflict with the other parent was having a significant negative impact on their child.

Developing a positive relationship

Separated completers occasionally outlined a desire to get to a positive place where they could co-parent effectively with their ex-partner and have constructive discussions about their children.

A large minority of intact completers came in with a great deal of positivity about being able to work on their relationship with their partner. For this group, just accessing support with their partner was seen as a positive step. By contrast, most intact non-completers appear to have come to the intervention at a point with such high levels of conflict that they judged their relationship to be in a terminal situation and, in one instance, separated following the intervention.

Specialised issues

A small minority of non-completers came to the intervention with very specific issues they wanted to address. These included communicating with and understanding the perspective of a partner with autism; dealing with a terminal illness diagnosis; an ex-partner with heroin addiction issues; and raising a child with autism.

Experience of the interventions

Overall impressions of the sessions

Generally intact and separated completers were positive about the sessions they took part in, as were some non-completers.

Positivity focussed on the sessions being run well and that the practitioners running the sessions were ‘friendly’, ‘professional’, ‘approachable’, ‘insightful’, ‘understanding’, ‘non-judgemental’, ‘empathetic’, ‘patient’ and ‘kind’. Alongside positivity about the practitioners, parents, in particular non-completers, highlighted the value of a sharing and discussing issues in a ‘safe space’. This view was held by those who attended both group and one-to-one sessions.

The gentleman that we spoke to was very warm and very understanding. He was very nice, and he knew what he was talking about. He didn’t hold back when he was interested; he asked follow up questions and he found our information to be informative.

Female, Intact, Non-Completer

Completers commonly felt that the practitioners tailored the sessions well to their situation and what would be most helpful for them.

However, other parents, including both completers (this was generally separated parents) and non-completers, disagreed and felt that the sessions were not tailored enough and some of the information presented was not relevant to their current situation. In some cases, particularly among non-completers, they had come with some quite specific issues (e.g., a partner’s substance abuse or a child’s learning disability) that practitioners were unable to assist with. There were also a few cases where it was felt that the practitioner did not manage the discussions with their ex-partners well. For example, there was one case where the separated completer felt that the practitioner wasn’t equipped to deal with the level of conflict between them and their ex-partner and allowed the ex-partner to constantly talk over the participant. There was another example of a practitioner not managing conflict in the sessions well where, in some instances, the separated couple would continue arguing after the sessions had finished.

There was a feeling from other parents, including both completers and non-completers, that the information provided through the sessions was not new or information they were previously unaware of. Among a small minority of non-completers this was the result of having been on similar parenting and relationship courses previously. However, in some cases these completers felt that having the sessions enabled them to think differently and be able to put this information into action.

What was good or worked well?

Completers

Many completers felt that practical tips provided in the sessions around understanding the other person’s point of view were very helpful. Parents couldn’t always remember the names of the techniques/ approaches, but the following were mentioned:

- The ‘window of tolerance’.

- A focus on ‘feelings’ rather than ‘facts’.

- Visualisation tasks for example, imagining sitting in a traffic jam and being overtaken, you don’t know the reason for this but there could be a good reason.

If you imagine you’re stuck in traffic and someone overtakes you, you can start ranting and raving, but you never know what that person’s situation is, there might be a good reason for it. That has definitely stayed with me from the day we discussed it.

Female, Separated, Completer

- Self-reflection exercises – e.g., reflecting on old arguments and how you would be perceived and also reflecting back on situations and how you felt and the process/reasoning behind it.

- ‘Love languages’ (intact couples) – helps them to understand when their partner is expressing affection in a way that isn’t immediately obvious to them/ is different to how they would show affection. Completers also mentioned that just having a third person’s input was very helpful, as they helped to point out how the misunderstanding may be occurring. They also mentioned communication approaches being discussed and that this element of the course was very helpful and thought provoking.

It helped having a third person input because I thought I was right, my partner thought she was right, so it was helpful having the third person to say you’re right to an extent, but your partner is right to an extent, and this is why. Just having it explained made life a lot easier.

Male, Intact, Completer

Intact and separated parents stated that better ways of communicating had been covered in terms of how to keep calm and how to listen to the other person before ‘jumping’ into a conversation.

Separated parents also appeared to discuss different forms of contact more and the best ways to approach and manage different forms of communication which parents found extremely helpful. For example:

- Parents were using their children as a means to communicate with each other. Practitioners reiterated that this approach should be avoided as it was not ideal for them, nor their children.

- A small minority of parents mentioned their use of text messages or Whatsapp and how conversations can escalate quickly. Practitioners sometimes recommended that they use other forms of communication which are less instant and will allow time to think through a response, such as email.

- There were also other instances of practitioners recommending that they think of their ex-partner as a work colleague or business partner, so the communications can be more practical and less emotional.

To treat your ex-partner like a co-worker. This does not mean having to have a friendly relationship but a practical or professional relationship.

Female, Separated, Completer

Parents also felt that the workbooks they had been given were very helpful, as they were a helpful log of topics covered and which topics would be coming up in later weeks. A few had also gone back to the workbooks after the sessions had finished to refresh their memories on what they had learnt during the sessions.

One separated parent also recalled a mindfulness exercise which had been very impactful for her. It inspired her to download a mindfulness app after the sessions which she has been using ever since. Another separated parent also mentioned a powerful visualisation exercise about her child’s future and what it would be like if her relationship with her ex-partner does not change.

Figure 2.2. The key elements of a ‘good’ intervention

Non-Completers

Non-completers were, perhaps unsurprisingly given their limited engagement compared to completers, less able to recall specifics of what worked well. Often the strength of the sessions was in creating a ‘safe space’ for discussing difficult issues that they might not have been able to discuss with their partner, in the case of sessions attended by both, or to hear the perspective of people experiencing similar issues, for those who attended group sessions.

The sessions were all about being open and honest. They gave everyone a chance to speak their mind and you knew you had a mediator there.

Male, Intact, Non-Completer

A small minority of non-completers felt the course content helped them to rethink their role in the relationship. These parents found the exercises focussing on how they and their partner should relate to one another gave them insight into the dynamics of a low conflict relationship. For one non-completer parent, this left them with improved expectations of how they should expect to be treated in a relationship.

What worked less well?

Elements of the interventions that worked less well, commonly related to either the content or the format of the intervention. This was true for both completers and non-completers.

Content

For completers, there were frustrations about elements of course content from specific interventions:

- A small minority of separated parents mentioned that the Triple P and Within my Reach videos were not appropriate as they did not show relatable families or relatable situations. One separated parent also felt that the videos were very ‘outdated’ meaning he struggled to take them seriously.

The materials felt disconnected to what it is to be a British parent in the present day, they were Australian, filmed 15-20 years ago.

Male, Separated, Completer

- Others who took part in Triple P, Within my Reach and Family Check-up also mentioned that they felt that the content was sometimes too general and not specific enough to their situation.

- A few separated parents who took part in Mentalization Based Therapy felt that the course lacked structure and the sessions ended up being places for their ex-partner to vent.

Some non-completers also found some of the course content less effective, however the issues outlined were not specific to individual interventions. For this group, course content was simply not seen as relevant to their situation, reflecting their unsuitability for the intervention. For a small minority of this group (consisting of completers and non-completers), this was because they felt they had experienced domestic abuse rather than conflict in the relationship. As such, techniques for reducing conflict with a parent were not applicable to their situation.

When I was invited to do the course, I wasn’t screened properly… the facilitators couldn’t really cope with some of the comments I was making because the other people hadn’t been through the courses I had, and they hadn’t been through domestic abuse

Female, Separated, Non-Completer

For other non-completers, their specific issues, such as an ex-partner with a heroin addiction or challenges related to a child with learning difficulties, meant that the content of the intervention did not address these specific challenges. One non-completer felt that the sessions were aimed at people who had been further along in their relationship when conflict began, whereas she had experienced a swift collapse of the relationship with her ex-partner a short time into their relationship.

Format

For completers, frustrations around the format focussed on two issues:

- Separated parents feeling that the sessions would have been more beneficial if they had some sessions with their ex-partner, or if the professional they were both speaking to could bring some insight from the other partners sessions. Undertaking the sessions in isolation meant it was very difficult for parents to see any progress as their ex-partner’s perspective and progress was unknown.

- Others also felt that the length of the sessions could have been a little more flexible. On some occasions they wanted to carry on as they felt they were having a breakthrough in the session, but they had to stop as the practitioner had other appointments.

Non-completers’ most commonly outlined issues with the format of sessions when discussing elements of the intervention that worked less well. These parents highlighted a few different issues:

- A dislike of the group format. This was because of public speaking apprehension or difficulty opening up in front of strangers, both of which left the respondent feeling unable to fully share.

- Frustrations with the online delivery and a preference for face-to-face sessions. While there was some acknowledgement that this was necessary during the pandemic, virtual delivery was seen as a barrier to building up a rapport with the practitioner.

You get to know somebody better when you’re not sitting in front of a computer screen… I think it’s really hard to try and build up a relationship with somebody when it’s done virtually.

Female, Intact, Non-Completer

- One non-completer felt that the group they attended was too large, which resulted in inconsistent levels of engagement from participants, allowing some to switch off and disengage.

Other

There was a feeling from a small minority of completers that, overall, the sessions didn’t focus enough on parenting and the impacts their relationship was having on their children.

A small minority of non-completers expressed frustrations with the practitioner. They felt that the practitioner stuck too rigidly to the programme, rather than exploring the issues they had. For one parent this was feeling that issues with their child were being side-lined while the focus was on their relationship, for the other it was the inverse, with issues in their relationship marginalised in favour of issues with the child.

Views on mode of delivery

Overall, parents tended to be satisfied with the way in which the reducing parental conflict sessions were run. This was the case across all the modes of intervention, regardless of whether they were one-to-one sessions, group sessions or a mix of one-to-one and group sessions.

In terms of improvements, a handful of parents taking part in one-to-one sessions said they would have appreciated a multi-mode approach, with some group sessions as well as their one-to-one sessions. These parents felt that the group sessions would have provided the opportunity to learn about other peoples’ situations and the opportunity to hear more solution ideas. Parents who took part in group sessions mentioned that this had been a benefit of the group discussion with the interaction giving them additional insight into behaviours and strategies to reduce parental conflict. A few had also kept in touch with fellow group members and continued to support each other after the intervention.

Hearing about how people have dealt with situations differently gives you an insight into how you should be dealing with things.

Male, Separated, Completer

Whilst the interaction in the group sessions was often positive, a small minority of non-completers mentioned that they felt uncomfortable with public speaking and opening-up to strangers. One non-completer also felt that they would have liked a one-to-one session at the end to given them the opportunity to speak openly and directly with her ex-partner and to make a plan to move forward.

In a few instances parents felt that it had been tricky at times to fit the face-to-face sessions around work and childcare, especially when the sessions were not taking place in their home. In one instance, only one parent of an intact couple could attend the sessions as the face-to-face timings did not fit with their partner’s working hours.

Parents who had taken part in the sessions online felt it had been an easy process and it had fitted around their home life very well. Whilst some non-completers mentioned that they would have preferred face-to-face, it was recognised that online via zoom was a necessity due to the Coronavirus pandemic.

How did parents feel after the sessions?

Parents who completed the course generally felt positive after the sessions. This was the case for both intact couples who took part together and for separated parents who took part alone and was generally attributed to the sessions providing the ‘safe space’ where parents could openly talk.

Separated and intact couples who completed the course felt particularly positive because they saw the impact of intervention on their relationship, and because they felt empowered to make a change in their communication approach.

Relieved, less burdened to have been able to talk in a safe space.

Female, Intact, Completer

And it was good to have it. I remember coming out of that session feeling this is definitely going to be a good thing for me, I can feel it.

Male, Separated, Completer

The small proportion of parents who did not feel positive after the sessions (but who completed the course) were generally separated parents, and this was due to feeling stressed and emotionally drained after the sessions.

Quite stressful and emotionally draining - it wasn’t a pleasant experience.

Male, Separated, Completer

Parents who did not complete all the sessions likewise had a mix of positive and less positive emotions. Parents often felt good after the sessions as they welcomed the opportunity of opening-up and talking about their relationship and found it reassuring to see that others were in the same situation as them (and sometimes in a worse situation). A small minority felt validated as they were already implementing some of the suggested techniques, or because the mediator had agreed with their parenting style. Some also felt more empowered having learnt more about how people behave and childhood development.

I never actually had anyone to clearly speak with so it was nice to just talk with someone… (outside of the sessions) I would only talk things through with my husband.

Female, Intact, Non-completer

I felt motivated as I felt that the sessions could help us to get past this rift. It was hard because it was uprooting pain, but it was fairly empowering at the same time.

Female, Separated, Non-completer

I felt fine! I thought, I seriously don’t have a problem, there are some strange people out there!

Female, Intact, Non-completer

In contrast, parents who did not complete the sessions were often less positive and frustrated that the sessions had not really given them what they needed. A small minority of parents mentioned that it was tiring or stressful, with this mainly down to the videos/content not always being enjoyable (with one non-completer saying the session made them revisit an old trauma) or because they had to juggle the sessions and ‘homework’ with other aspects going on in their life.

We felt quite disappointed that we didn’t get the support we were supposed to be receiving so we felt let down.

Female, Intact, Non-completer

We both were of the same opinion that there was nothing covered in the sessions that we benefited from. We didn’t bring anything from the sessions; we don’t have anything in place that we can say, oh we got that from the session.

Female, Intact, Non-completer

Failure to complete or start

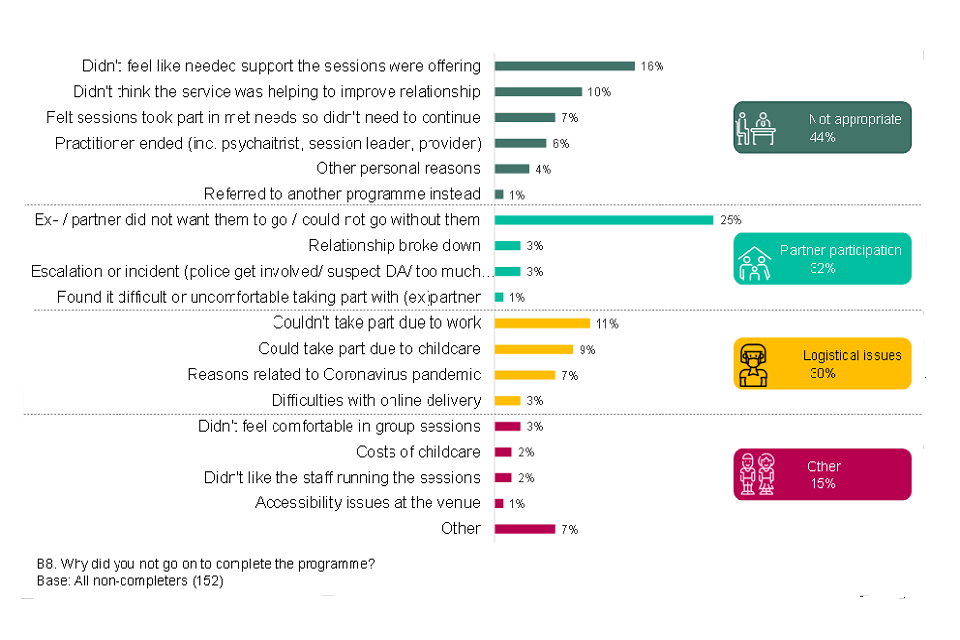

Parents who did not complete the Reducing Parental Conflict course were asked their reasons for this in a survey, with reasons amongst this group and amongst non-starters explored more deeply in the qualitative interviews (please note these qualitative interviews were primarily conducted with separated parents, rather than intact couples).

Both sets of parents gave a broad range of personal and practical reasons for not starting or completing the course. Although of lesser magnitude, some parents dropped-out of the intervention as it was no longer appropriate for their situation.

Figure 2.3 Sessions no longer seeming appropriate were the most common reasons for not completing

Sessions no longer appropriate

For 16% of non-completers, the support that the sessions offered was not deemed necessary. In the qualitative interviews, some had dropped-out as they felt the focus of the sessions was not right for them and their situation. In one instance the parent taking part in the intervention felt that the mediator seemed unable or reluctant to deviate from their set structure to accommodate their needs. One parent felt that the focus was on the children but that their issue was in terms of the parental relationship, whilst another parent wanted less focus on the parental relationship and more focus on learning to communicate effectively with their son, who had autism. In another example, the parent felt the content was skewed to families who had been together for several years, whereas this situation was not relevant to them.

In the end, we refused to actually complete the course because the lady we’d been assigned to do the course with us, she was more focused on the issues we had with my partners son than the issues we had between the 2 of us so we felt that the course wasn’t actually what we’d been told it was about.

Female, Intact, Non-completer

Although less common, non-completers also said they dropped-out because the sessions were no longer suitable for them and their personal situation. In the survey, 6% of non-completers said the practitioner ended it, 4% for other personal reasons, and 1% that they were referred to another programme. During the qualitative interviews, non-completers also reported not finishing the intervention because they were not suitable. For some, this was the result of the suggestion of the practitioner, while others left of their own accord. The reasons why the interventions were felt to be unsuitable tended to be because the level of conflict in their relationship had passed the domestic abuse threshold or because they faced specialised issues in their relationship or life that could not be addressed in the sessions (e.g., serious mental health issues).

They said the course wasn’t right for me because I’m further along the journey, so I said, ‘I get it, I’m going to dilute what the others would get from it… the course should only be for those who are just having difficulties not those who have been through domestic abuse.

Female, Separated, Non-completer

The most common reason why sessions were felt to not be appropriate was that they were not helping to improve the relationship (10%). This issue emerged in the qualitative interviews, where non-completers felt that, because of specialised needs (such as substance abuse issues or a partner / child with autism) or a perception that the level of conflict had become domestic abuse, the sessions were simply not applicable to the issues they faced. In a few instances, some couples who attended together found that the sessions encouraged them to discuss issues that caused conflict with their partner, exacerbating the tension in their relationship.

Positively, there were some instances of parents not completing all sessions because they felt their needs had been met (7%), and stories of separated parents resolving their issues with their ex-partner and even reconciling. In the qualitative interviews, a few of non-completing parents felt they had been through a similar parenting course before and knew much of the content and one was told by the practitioner that, due to the progress already made in the sessions, there was nothing further that could be accomplished in the intervention.

Partner participation obstacles

A quarter (25%) of non-completers stated that the reason they did not complete was because their (ex-) partner did not want them to go, and they felt they needed to attend as a couple (either to get the right outcome, or because they would be ineligible to attend without their partner).

Separated non-starter parents also talked about their (ex-) partner not wanting to engage in the programme, although some also mentioned that they themselves did not want any further contact with their ex-partner. In one instance the ex-partner refused to attend because it was causing conflict with a new partner. In other instances, and for separated parents there had been no relationship for some time or there had been domestic abuse; this meant that learning to work together as a co-parent was not considered to be a viable option. In these cases, the parent often just wanted some strategies for coping with a difficult ex-partner or some specialist support around issues such as substance abuse and mental health.

Well, I said I’m not doing it either then - there’s no point doing it on my own.

Female, Separated, Did Not Start

As well as parents feeling the sessions were not relevant to them, some felt that they were detrimental to their relationship, non-completers said that at times the sessions were causing more conflict with their partner as the issues discussed resulted in subsequent arguments.

Parents felt that the issues they were experiencing were solely caused by their ex-partner rather than themselves, and therefore believed it was their ex-partner who really needed the intervention.

I had a long hard think but said no, I don’t want any kind of relationship (with ex-partner).

Male, Separated, Did Not Start

Because I don’t need to learn how to parent. This might sound like I’m not taking any responsibility for anything but I’m not unreasonable. I don’t stop him seeing my daughter, you know, all I ask is that his behaviour towards me is reasonable. If anyone needed to go on a course, it would be him not me.

Female, Separated, Did Not Start

In some cases, there had been a deterioration in the relationship that stopped parents from completing either because their relationship had broken down (3%) or because there had been an escalation in the conflict (3%). During the qualitative interviews, a few non-completers from intact couples reported that their relationship had ended during or immediately after their involvement in the intervention. For these parents, the sessions had been a final effort to resolve conflict but had come to the conclusion that the relationship could not be salvaged. One non-completer also outlined an escalation in conflict that had resulted in their arrest and removal from the family home, as a result of this they had been unable to complete the sessions.

As shown in Figure 2.3, some non-completers dropped-out because they found it difficult or uncomfortable taking part with their (ex) partner (1%). One parent discovered that their ex-partner had changed their name to their son’s name during a session, this made them feel too embarrassed and upset to keep going.

Logistical issues

As well as personal reasons for not starting or completing the sessions, practical barriers were also raised. As shown by the survey, non-completers often mentioned reasons relating to the Coronavirus pandemic (7%). In the qualitative interviews, some reported that this was due to children being at home during the sessions which meant less freedom and flexibility.

For both non-completers and non-starters, a minority of parents found the timing of the sessions challenging. For example, some parents struggled to find available slots around their working hours and/or at a time when they could arrange childcare (11% and 9% respectively of non-completers, both these issues were also raised by non-starters in the qualitative depth interviews). Others mentioned more ongoing personal issues such as their partner being in hospital, their child experiencing some mental health difficulties, or their ex-partner demanding they have the children at the time of the session.

I couldn’t attend when my ex-partner was able to do her sessions, but it was pointless, we needed to do it together.

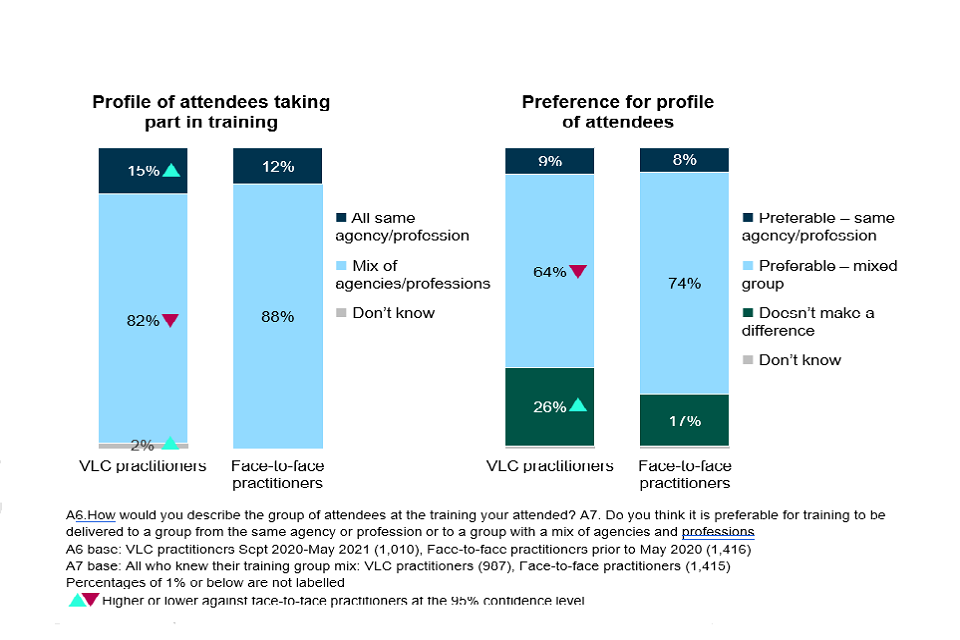

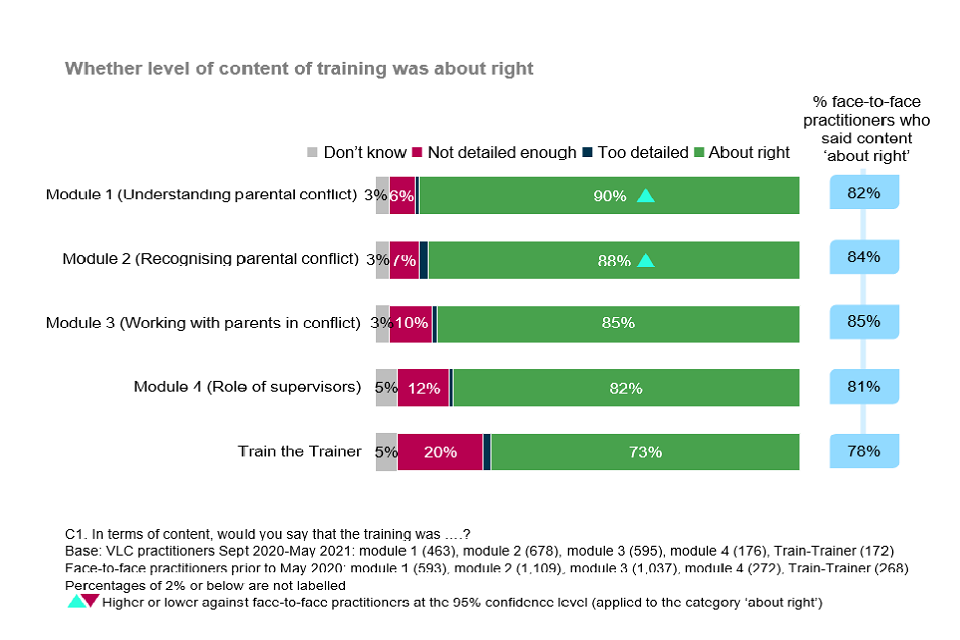

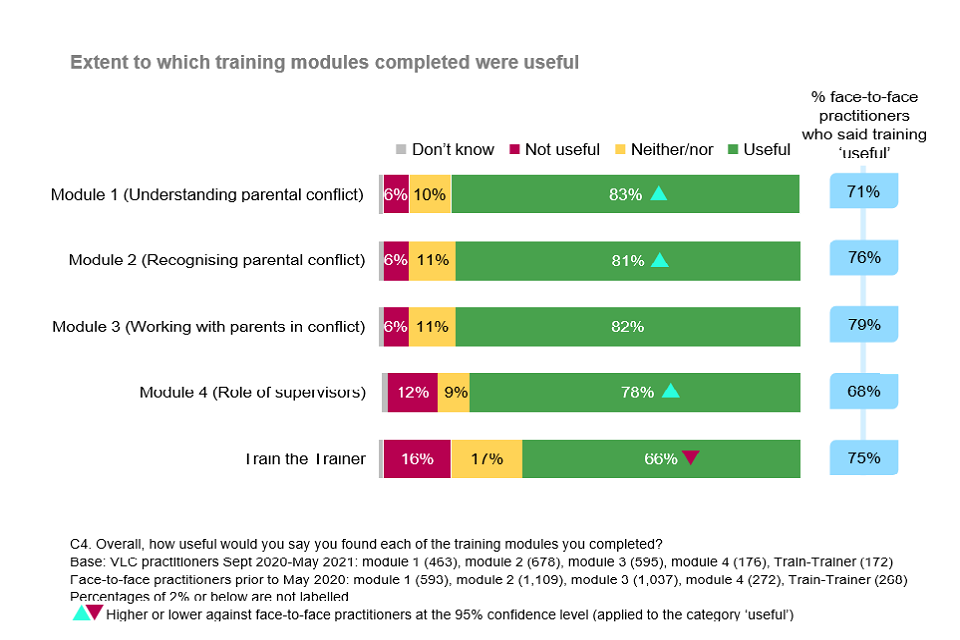

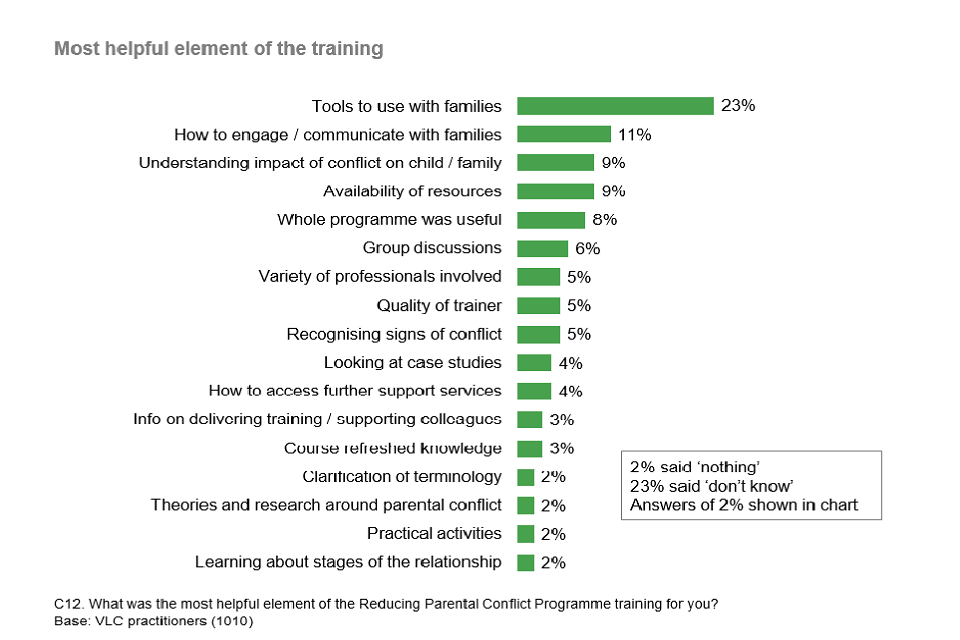

Male, Separated, Non-completer