Race in the workplace: The McGregor-Smith review - report

Published 28 February 2017

Issues faced by businesses in developing Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) talent in the workplace

Every person, regardless of their ethnicity or background, should be able to fulfil their potential at work.

That is the business case as well as the moral case. Diverse organisations that attract and develop individuals from the widest pool of talent consistently perform better.

1. It’s time to unlock talent

The time for talking is over

For decades, successive governments and employers have professed their commitment to racial equality yet vast inequality continues to exist. This has to change now. With 14% of the working age population coming from a Black or Minority Ethnic (BME) background, employers have got to take control and start making the most of talent, whatever their background.

The reward is huge

This should be enough of a wake-up call for any company to realise they can’t ignore this issue any more. However, I know that most companies will only act when they see a reason to do so. It is simply not right that BME representation in some organisations is clustered in the lowest paid positions. So all employers with more than 50 people must set aspirational targets to increase diversity and inclusion throughout their organisations – not just at the bottom. Companies should look at the make-up of the area in which they are recruiting to establish the right target. For instance, the proportion of working age people from a BME background in London and Birmingham is already over 40%, with Manchester not far behind.

“If BME talent is fully utilised, the economy could receive a £24 billion boost.”

Daylight is the best disinfectant

Employers must publish their aspirational targets, be transparent about their progress and be accountable for delivering them. The government must also legislate to make larger businesses publish their ethnicity data by salary band to show progress. This isn’t about naming and shaming. No large business has a truly diverse and inclusive workforce from top to bottom at the moment, but through publishing this data, the best employers will be able to show their successes and encourage others to follow.

We need to stop hiding behind the mantle of ‘unconscious bias’

Much of the bias is structural and a result of a system that benefits a certain group of people. This doesn’t just affect those from a BME background, but women, those with disabilities or anyone who has experienced discrimination based upon preconceived notions of what makes a good employee. Fixing this will involve a critical examination of every stage of the process, from how individuals are recruited to how they are supported to progress and fulfil their potential. The importance of effective mentoring, sponsorship, role models and networks in delivering positive action needs to be understood at all levels of an organisation, with leaders taking responsibility for creating truly inclusive workplaces.

The public sector must use its purchasing power to drive change

Any organisation that is publicly funded must set and publish targets to ensure they are representative of the taxpayers they deliver for. The government should go further and ensure that it is driving behaviour change in the private sector too. Anyone tendering for a public sector contract should have to show what steps they are taking to make their workplaces more inclusive in order to be awarded a contract.

Fully inclusive workplaces are the target

Too many people are uncomfortable talking about race. This has to change. In order to have a truly inclusive environment where everybody can bring their whole self to work, the changes I have recommended must be made. Only then will everyone in the workforce be able to fulfil their potential, increase productivity and deliver the £24 billion of benefits to the UK economy.

2. Foreword

In the UK today we face significant challenges developing our economy in a world that is changing rapidly. Technology in particular is disrupting old industries and creating new ones at an unprecedented pace. For our economy and our businesses to be globally competitive and to thrive, it has never been more important to nurture and utilise all of the talent available to us.

The evidence demonstrates that inclusive organisations, which attract and develop individuals from the widest pool of talent, consistently perform better. That is the business case. But I believe the moral case is just as, if not more, compelling. We should live in a country where every person, regardless of their ethnicity or background, is able to fulfil their potential at work. Sadly, we are still a long way from this.

There is no reason why every organisation in the UK should not have a workforce that proportionately reflects the diversity of the communities in which they operate, at every level. This is what our collective goal should be, and has guided the recommendations I have made in this report.

BME individuals in the UK are both less likely to participate in and then less likely to progress through the workplace, when compared with White individuals. Barriers exist, from entry through to board level, that prevent these individuals from reaching their full potential. This is not only unjust for them, but the ‘lost’ productivity and potential represents a huge missed opportunity for businesses and impacts the economy as a whole. The potential benefit to the UK economy from full representation of BME individuals across the labour market, through improved participation and progression, is estimated to be £24 billion a year, which represents 1.3% of GDP[footnote 1].

As part of this review, we consulted with a wide range of individuals to understand the obstacles to progression and their impacts, as well as identify some of the best practice that is already in place. There are many organisations that are doing really great things. But we found that the obstacles are both significant and varied.

In the UK today, there is a structural, historical bias that favours certain individuals. This does not just stand in the way of ethnic minorities, but women, those with disabilities and others.

Overt racism that we associate with the 1970s does still disgracefully occur, but unconscious bias is much more pervasive and potentially more insidious because of the difficulty in identifying it or calling it out. Race, gender or background should be irrelevant when choosing the right person for a role – few now would disagree with this. But organisations and individuals tend to hire in their own image, whether consciously or not. Those who have most in common with senior managers and decision makers are inherently at an advantage. I have to question how much of this bias is truly ‘unconscious’ and by terming it ‘unconscious’, how much it allows us to hide behind it. Conscious or unconscious, the end result of bias is racial discrimination, which we cannot and should not accept.

There is discrimination and bias at every stage of an individual’s career, and even before it begins. From networks to recruitment and then in the workforce, it is there. BME people are faced with a distinct lack of role models, they are more likely to perceive the workplace as hostile, they are less likely to apply for and be given promotions and they are more likely to be disciplined or judged harshly.

We found that transparency in organisations is crucial. Career ladders, pay and reward guidelines, and how and why people are promoted are often opaque. Perhaps more importantly, many organisations do not even know how they are performing on this issue overall. Until we know where we stand and how we are performing today, it is impossible to define and deliver real progress. No company’s commitment to diversity and inclusion can be taken seriously until it collects, scrutinises and is transparent with its workforce data. This means being honest with themselves about where they are and where they need to get to as well as being honest with the people they employ. That is why I was disappointed that only 74 FTSE 100 companies replied to my call for data and shocked only half of those were able to share any meaningful information. One of the key recommendations I am making is for organisations to publish their data, as well as their long-term, aspirational diversity targets and report against their progress annually. I truly believe that making this information public will motivate organisations to tackle this issue with the determination and sense of urgency it deserves.

It is no surprise that leadership and culture play a key role in creating obstacles while also providing the solutions that enable BME individuals’ success. It is critical that support for building an inclusive business comes from the top – this agenda needs broad executive support, which needs to filter down through organisations. We have also found that mentoring and sponsorship have consistently delivered results and it is incumbent upon all management to play their part in supporting people from all backgrounds.

Language is something that was consistently raised throughout this review as being hugely difficult. Most people today still find it really hard to talk about race and ethnicity, particularly in the workplace. Business leaders need to create inclusive cultures that enable employees to bring their whole selves to work and encourage people to talk openly – these things take time but this is a goal that every business should be working towards. I am recommending that the government produces a comprehensive guide for business on how to talk about race in the workplace.

Whilst there is no doubt that we face a long road ahead and have a lot of work to do before our workplaces are truly equal, there is also much to be positive about. Throughout this report we have highlighted some of the incredible things that are being done by organisations across the UK to create more inclusive workplaces. We already have so many of the solutions to tackle this issue; they just need to be applied more broadly. I encourage all organisations to take this best practice and adapt it for their own workplaces.

While undertaking this review I have met so many people who are deeply passionate about these challenges and are doing amazing things to create change. I would like to thank all of the individuals who contributed to this review and offered their thoughts and wisdom so candidly, on what can be a very difficult topic.

From a personal perspective, I came to Britain when I was 2 years old. Having grown up in an Asian Muslim family, what has struck me the most during this review is that the feelings of exclusion and judgement on the colour of my skin, my underprivileged background and being a woman, were all things I had hoped were in the past. However, I have been saddened to see that it is not the case. Britain has been the only home I know and I believe it is an extraordinary place to live and grow up in, despite the fact that it was very painful at times, because feeling excluded is a very lonely, difficult place to be. I overcame many barriers to achieve what I have done in business, but even today I am seen as someone different. There are so many others like me, who want to see the end of discrimination based on background, race, privilege and gender. Speaking on behalf of so many from a minority background, I can simply say that all we ever wanted was to be seen as an individual, just like anyone else. I can only thank those who saw talent in me, those who looked beyond my colour, background, religion and the fact that I am female. That is how we all need to be and I hope the findings and recommendations in my review help to set the roadmap for change.

3. Next steps

I appreciate that in the UK today there are a multitude of economic challenges, and corporate and political requirements for organisations to deliver against or take into consideration.

To enable senior executives to prioritise the recommendations in this review and achieve greater output in the short term, I have created a roadmap to success. This will help busy leaders to focus on the immediate requirements that will enable them to move positively towards a more diverse workforce, while empowering them to plan for the medium term and the associated economic benefits.

-

Gather data.

-

Take accountability.

-

Raise awareness.

-

Examine recruitment.

-

Change processes.

-

Government support.

A roadmap to success

1. Gather data:

Organisations must gather and monitor the data by:

- setting, then publishing aspirational targets

- publishing data to show how they are progressing

- doing more to encourage employees to disclose their ethnicity

2 Take accountability:

Senior executives must take accountability by:

- ensuring executive sponsorship for key targets

- embedding diversity as a Key Performance Indicator

- participating in reverse mentoring schemes to share experience and improve opportunities

- being open about how they have achieved success, in particular Chairs, CEOs and CFOs in their annual reports

3. Raise awareness:

All employers must raise awareness of diversity issues by:

- ensuring unconscious bias training is undertaken by all employees

- tailoring unconscious bias training to reflect roles – for example, workshops for executives

- establishing inclusive networks

- providing mentoring and sponsorship

4. Examine recruitment:

HR directors must critically examine recruitment processes by:

- rejecting non-diverse shortlists

- challenging educational selection bias

- drafting job specification in a more inclusive way

- introducing diversity to interview panels;

- creating work experience opportunities for everyone, not just the chosen few

5. Change processes:

Responsible teams must change processes to encourage greater diversity by:

- being transparent and fair in reward and recognition

- improving supply chains

- being open about how the career pathway works

6. Government support:

Employers should be supported in making these changes by government. Specifically, government should:

- legislate to make publishing data mandatory

- create a free, online unconscious bias training resource

- develop a guide to talking about race at work

- work with Business in the Community and others to develop an online portal of best practice

- seek out ways to celebrate success – such as a top 100 BME employers list

- write to all institutional funds who have holdings in FTSE companies and ask them for their policies on diversity and inclusion and how they ensure that the representation of BME individuals is considered across the employee base of the companies where they hold investments

While it is for employers to deliver these changes, government must keep their feet to the fire and should consider how opportunities have improved for ethnic minorities in 12 months.

4. Executive summary

The case for action

The headline findings show that:

1 in 8 of the working age population were from a BME background

In 2015, 1 in 8 of the working age population were from a BME background, yet BME individuals make up only 10% of the workforce and hold only 6% of top management positions[footnote 2].

62.8% The employment rate for ethnic minorities

The employment rate for ethnic minorities is only 62.8% compared with an employment rate for White workers of 75.6% – a gap of over 12 percentage points. This gap is even worse for some ethnic groups, for instance the employment rate for those from a Pakistani or Bangladeshi background is only 54.9%[footnote 3].

15.3% BME background underemployment rate

People with a BME background have an underemployment rate of 15.3% compared with 11.5% for White workers[footnote 4]. These people would like to work more hours than they currently do.

All BME groups are more likely to be overqualified than White ethnic groups but White employees are more likely to be promoted than all other groups[footnote 5].

Overview

The potential benefit to the UK economy from full representation of BME individuals across the labour market through improved participation and progression is estimated to be £24 billion a year, which represents 1.3% of GDP.

The underemployment and underpromotion of people from BME backgrounds is not only unfair for the individuals affected, but a wide body of research exists that has established that diverse organisations are more successful. As McKinsey identified in 2015, companies in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversity are 35% more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry medians[footnote 6].

The lost potential and productivity – both from these individuals being more likely to be out of work or working in jobs where they are overqualified (and underutilised) – has a significant impact on the economy as a whole. If the employment rate for ethnic minorities matched that of White people, and BME individuals were in occupations commensurate with their qualifications, the benefits are massive. The potential benefit to the UK economy from full representation of BME individuals across the labour market through improved participation and progression is estimated to be £24 billion a year, which represents 1.3% of GDP.

During the course of this review, we have heard a number of examples of discrimination and outright racism that are illegal and clearly have no place in any 21st century company. Where these are identified, employers need to act fast and ensure that outdated and offensive views or behaviours are not tolerated. However, dealing with explicit discrimination alone will not change the fortunes of the majority of ethnic minorities in the UK. In many organisations, the processes in place, from the point of recruitment through to progression to the very top, remain favourable to a select group of individuals. This bias is referred to as ‘unconscious’, sometimes wrongly, and it is reinforced by outdated processes and behavioural norms that can and must be improved, to create more inclusive working environments that benefit everybody.

This review has identified a number of changes that can be made by employers in the public, private and third sectors to improve diversity within their organisations. Some are easier, some more longterm and fundamental, but these changes will help organisations to recruit a more diverse workforce, take full advantage of their existing talent, and service their customer base more effectively by having a more representative workforce. If implemented, these should result in fairer, more inclusive workplaces, happier staff and ultimately, increases in productivity.

Measuring success

Given the impact ethnic diversity can have on organisational success, it should be given the same prominence as other key performance indicators. To do this, organisations need to establish a baseline picture of where they stand today, set aspirational targets for what they expect their organisations to look like in 5 years’ time, and measure progress against those targets annually. What is more, they must be open with their staff about what they are trying to achieve and how they are performing.

Changing the culture

Improving diversity across an organisation takes time. Aspirational targets provide an essential catalyst for change, but to achieve lasting results, the culture of an organisation has to change. Those from BME backgrounds need to have confidence that they have access to the same opportunities, and feel able to speak up if they find themselves subject to direct or indirect discrimination or bias.

Improving processes

From initial recruitment, to the support an individual gets and their progression opportunities, processes need to be transparent and fair. In many organisations, the well-established processes in place can act as a barrier to ethnic minorities and hinder their progress through an organisation.

Supporting progression

Getting a job is only the first step of the career ladder. For those who have friends or family with experience of particular professions, there can be an advantage that supports them in their development. However, this does not result in a business placing the very best candidates in every role.

Inclusive workplaces

The greatest benefits for an employer will be experienced when diversity is completely embedded and is ‘business as usual’. This means more than simply reaching set targets and changing the processes. It means that everyone in an organisation sees diverse teams as the norm and celebrates the benefits that a truly inclusive workforce can deliver.

The time for talking is over. Now is the time to act.

It will require concerted and sustained effort from all of us but the solutions are already there, if we only choose to apply them. That is why I agreed to carry out this review. The business case is there for all to see. But providing equal opportunities to people of all backgrounds is also, quite simply, the right thing to do. By implementing these recommendations, we have a huge opportunity to both raise the aspirations and achievements of so many talented individuals, and to deliver an enormous boost to the long-term economic position of the UK.

5. The case for action

Over the past 40 years, the makeup of the labour market in the UK has changed dramatically. The proportion of the working age population that come from a BME background is increasing.

In 2016, 14% of the working age population are from a BME background. This is increasing, with the proportion expected to rise to 21% by 2051.

The backdrop

Over the past 40 years, the makeup of the labour market in the UK has changed dramatically. The proportion of the working age population that come from a BME background is increasing. In 2016, 14% of the working age population are from a BME background[footnote 7]. This is increasing, with the proportion expected to rise to 21% by 2051[footnote 8]. However, this is not reflected in the majority of workplaces, with many ethnic minorities concentrated in lower paying jobs. A 2015 study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation identified that a higher proportion of BME individuals tended to work in lower paying occupations such as catering, hairdressing or textiles[footnote 9].

There are also significant differences in labour market outcomes by ethnicity. For instance, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation found that occupations requiring intermediate skills, such as nursing assistants, tended to attract more individuals from an African background, whereas those with a Bangladeshi and Pakistani heritage were more likely to end up in customer service occupations and process, plant and machine occupations[footnote 10]. Some of this may be related to geography as a number of ethnic groups tend to be concentrated in particular cities where there can be more opportunities in certain sectors, although there can be little doubt that insurmountable barriers do hinder certain groups in a number of sectors.

The types of jobs that ethnic minorities find themselves in unsurprisingly impacts on wider income inequality. This is particularly stark for some ethnic groups. For instance, between 2011 to 2015, individuals from a Bangladeshi or Pakistani origin were far more likely to be in low paying work than White workers[footnote 11]. However, there have been some success stories. The income distribution for Black/ African/Caribbean/Black British workers is almost comparable with that for White workers. Likewise, there are now more Indian workers who are in the top earnings decile (top 10%) compared to White workers.

BME individuals also struggle to achieve the same progression opportunities as their White counterparts. 1 in 8 of the working age population are from a BME background, yet only 1 in 10 are in the workplace and only 1 in 16 top management positions are held by an ethnic minority person[footnote 12]. In terms of opportunities for progression 35% of Pakistani, 33% of Indian and 29% of Black Caribbean employees report feeling that they have been overlooked for promotion because of their ethnicity[footnote 13]. Joseph Rowntree Foundation found that BME groups tend to have unequal access to opportunities for development, often because of a lack of clear information on training opportunities or progression routes within their workplaces. This can be made worse if progression relies on opaque or informal processes, if there is a lack of BME role models or mentors at higher levels within their workplaces to provide support and advice, or if there is a gap between equality and diversity policies and practice in the workplace[footnote 14].

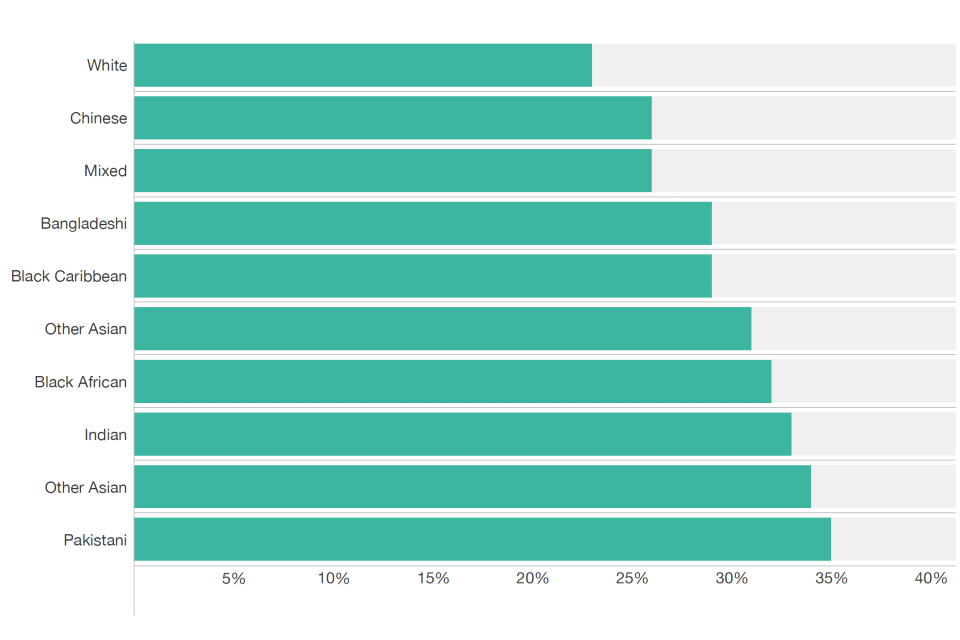

Percentage of employees reporting that they have been overlooked for promotion, by ethnic group[footnote 15]

""

| Ethnic group | % of employees reporting that they have been overlooked for promotion |

|---|---|

| White | 23% |

| Chinese | 26% |

| Mixed | 26% |

| Bangladeshi | 29% |

| Black Caribbean | 29% |

| Other Asian | 31% |

| Black African | 32% |

| Indian | 33% |

| Other Asian | 34% |

| Pakistani | 35% |

Insurmountable barriers

Our call for evidence asked specifically what the obstacles to progression were for those from a BME background. Only a small proportion of individuals believed language skills or a lack of qualifications or formal skills were an issue. The main barrier many individuals felt was standing in their way was the lack of connections to the ‘right people’. For employers and organisations, it was unconscious bias that was identified as the main barrier. However, for all groups, discrimination featured prominently as an obstacle faced by ethnic minorities. More detail on this can be found in the summary of the call for evidence findings at the end of this report.

The economic impact

Businesses that responded to the call for evidence identified a range of business impacts from increased racial diversity in their organisations including attracting staff from a wider talent pool, improved employee engagement, more effective teams, increased innovation and improved understanding of their customer base leading to higher customer satisfaction. Businesses need to recognise the huge opportunity to harness the untapped potential of BME talent. Research by the government on the business case for equality and diversity suggests that diversity of people brings diversity of skills and experience, which in turn can deliver richer creativity, better problem solving and greater flexibility to environmental changes. The potential benefit to the UK economy from full representation of BME individuals across the labour market, through improved participation and progression, is estimated to be £24 billion a year, which represents 1.3% of GDP[footnote 16]. This is a real opportunity that businesses will want to grasp. Every employer in the UK should be seeking to obtain their share by making the changes identified in this report.

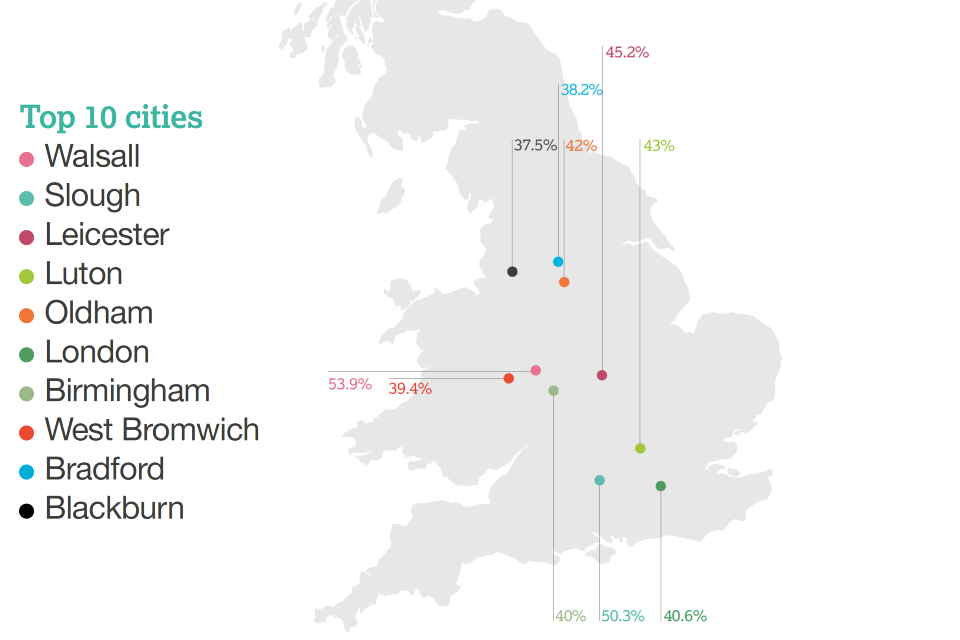

BME working age population by city

The map highlights the top 10 cities in the UK with the highest proportion of working age people from BME backgrounds.

""

| Top 10 cities | % BME |

|---|---|

| Walsall | 53.9% |

| Slough | 50.3% |

| Leicester | 45.2% |

| Luton | 43.0% |

| Oldham | 42.0% |

| London | 40.6% |

| Birmingham | 740.0% |

| West Bromwich | 39.4% |

| Bradford | 38.2% |

| Blackburn | 37.5% |

A full breakdown is in Annex F.

6. Measuring success

Successful businesses recognise the benefits that a more inclusive workforce can bring, through diverse skills, talents and experiences.

For a national organisation, I would expect to see overall targets of 14%

Aspirational targets

Successful businesses recognise the benefits that a more inclusive workforce can bring, through diverse skills, talents and experiences. However, while the business case for greater workforce diversity is strong, it is clear that many employers only take the positive action required when success is weaved into the key performance indicators (KPIs) of both senior management and the organisation as a whole. Most commonly we see these KPIs focus on sales figures or profits, but more recently we have seen KPIs set by companies to try and increase gender diversity at all levels of their organisation. In part this has been driven by the requirement to report the gender pay gap. Some have suggested quotas to ensure that workforces mirror the working age demographic in the UK. However, I have heard from a significant number of employers and individuals during the review that quotas can cause resentment and, in some cases, lead to unintended consequences and unhelpful interventions.

I do not believe that quotas are the answer. However, what we have learned from the debate on gender is that many companies will only take positive action when targets are set. For that reason, I believe that companies should set aspirational diversity targets. It is important that these targets are meaningful and, while challenging, must reflect the reality of the situation. Some of the best examples we have seen of targets being delivered have come from employers who tailor these to local circumstances, allowing regional business managers to take ownership. For instance, where employers are based in areas of low BME density, expecting them to reach 14% of their workforce is unrealistic. However, this works both ways and where employers are located in urban areas with high BME populations such as London, Birmingham or Manchester, aiming for 14% would be neither representative nor ambitious enough. For a national organisation, I would expect to see overall targets of 14%, rising to 20% by 2050 in line with predictions for UK population growth and composition.

Often the story across different levels of an organisation is mixed. Many companies have told us that they have a good story to tell when it comes to entry grades but progression is not proportionate. Organisations should set targets not just for the organisation as a whole, but to ensure that every level of their organisation moves towards being representative of the local working age population. Leaders should use data reporting to inform targeted positive action at those stages where additional intervention is required to increase diversity across the whole of the organisation.

The overall diversity of an organisation is not going to change overnight and so employers should set a realistic timeframe for delivering results. I believe that 5-year targets could be ambitious and realistic for many companies. It is also important that employers are open and transparent about what they are trying to achieve and so should publish progress against their targets. This will show their commitment to improving diversity and allow them to celebrate success. That way, investors can also hold the board to account to deliver the kinds of increased returns that McKinsey identified. There is also a role here for trade unions to work with employers to establish targets and to hold them to account, measuring performance against these targets.

From speaking to a number of employers during this review, I have no doubt that the majority take this issue seriously and will act upon these findings. Many are already setting themselves aspirational targets and holding senior executives to account. Some remain reluctant to publish their results for fear of being seen to have a poor story to tell. However, let us be clear, no one has cracked diversity yet and everyone can improve. This is not a matter of shaming companies with a poor baseline, rather being honest about where they are and where they want to get to.

EY’s BME partner representation is 8% in 2016.

The case I have made for taking diversity seriously is clear and I expect responsible employers will take action. The public sector should lead the way and ensure that targets are set in any organisation that spends taxpayers’ money. I welcome the government targets for the police and armed forces, but this must go further. As employers of millions of people across the UK, all public sector bodies must strive to be representative of the populations they serve. By reflecting the local population, public and private sector organisations can understand the needs of their customers more effectively. While formal targets may not be appropriate for smaller organisations, it is still in their interest to have a diverse workforce. Smaller organisations – particularly those in their early years with ambitions for growth – may find setting informal targets helpful as part of their business planning.

Case study: EY

EY is a professional service firm. We believe that culture change takes time – and we are therefore patient and at the same time impatient to interrupt the status quo. The key for the success of our Inclusive Leadership Programme to date has been the role modelling from our leadership team. The ownership and accountability lies with them and not with a diversity and inclusiveness team. What we mean is:

- our recruitment teams have set targets for recruitment of BMEs at all levels

- our board challenges the proportion of BME senior promotions and challenges whether we achieve our target to admit 10% BME partners every year

- our HR team challenges the representation of BME people on our leadership programmes

- our resourcing team challenges the way work is allocated to our BME team members

- since the inception of the programme our BME partner representation has gone up from 3% in 2012 to 8% in 2016 and more of our BME population are receiving high performance ratings

Recommendation

1. Published, aspirational targets: Listed companies and all businesses and public bodies with more than 50 employees should publish 5-year aspirational targets and report against these annually.

Data reporting

Setting aspirational targets only works if you have robust data to both establish the baseline and measure the impact of positive action. When I wrote to the CEOs of FTSE 100 companies in February 2016, I asked them to provide an anonymised version of their employee ethnicity data to the review team. The request asked for mean and median pay data, the number of employees within £20,000 salary bands and the number of employees in each category of seniority by ethnic group. I believed that understanding how some of the UK’s most prominent firms collect, store and use ethnicity data would provide an insight into best practice and areas for improvement amongst the wider business community. The responses were certainly interesting. Only 74 FTSE 100 companies responded and just over half of those were able to provide data. For the companies that responded, there were wide variations in the type of data that companies collected and the number of people who had completed the ethnicity category.

In my call for evidence I also asked employers of all sizes whether they collected data on the ethnicity of their workforce. All but one of the employer respondents said their organisation did collect data on employee ethnicity. However, many raised the issue of non-disclosure and were struggling to persuade individuals to provide that information.

No employer can honestly say they are improving the ethnic diversity of their workforce unless they know their starting point and can monitor their success over time. Simply stating a commitment to diversity or establishing a race network is not sufficient to drive lasting change. We have seen with the gender pay reporting requirements that where employers are required to collect and publish key data, they will take action. For that reason, I believe it is essential that as well as collecting this data, all large employers must publish their workforce ethnicity data annually. This is already a legal requirement in the US and so is perfectly possible[footnote 17].

Self-reporting rates for ethnicity vary significantly from employer to employer. Low reporting rates in themselves do not constitute a reason not to publish data. However, there can be no doubt that the higher the reporting rates, the more helpful the data is likely to be in measuring success. A number of people who fed into the review suggested that one of the reasons why reporting rates were low was a lack of transparency about why information was being collected. When a new employer asks for your bank details, you know this is so you can be paid and so you fill it in. The same is not true when considering ethnic origin and employers should consider being clearer about why they are collecting the data, how it will be used to measure the delivery of targets and the wider importance of diversity to the organisation. Other positive action should be considered and improving reporting rates should not just be something considered at entry to an organisation, but routinely promoted.

The organisations we have spoken to take diversity seriously and I have no doubt will be keen to lead from the front and begin publishing data. However, to ensure that all companies do this, the government should legislate, much as in the US, where companies employing over 100 people already have to provide this data, broken down by pay bands. This will allow everybody to see how ethnic minority staff are progressing through the organisation. I firmly believe that if organisations start to report publicly on the diversity of their workforce they will take action and we will see significant improvements.

Case study: Lloyds Banking Group

At Lloyds Banking Group we have launched regular communication campaigns, sponsored by senior leadership, to encourage colleagues to complete all personal details (including ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation) on our HR system.

We have been able to link the request to complete personal data with our Group purpose of Helping Britain Prosper through better representing the customers and communities we serve, whilst also improving the workplace for everyone – giving colleagues a positive reason to share this information. At launch we supported the communication campaign by equipping leadership and line managers with a guidance pack, including FAQs, to help them explain to colleagues the positive benefits of Lloyds Banking Group having accurate data around the diversity of our workforce. Since the launch of our communications campaign, we have seen a 4% increase in completion of ethnic origin data across our full employee population, equating to over 3,000 colleagues voluntarily updating their details.

Recommendations

2. Publicly available data: Listed companies and all businesses with more than 50 employees should publish a breakdown of employees by race, ideally by pay band, on their website and in the annual report. All public bodies employing more than 50 people should publish a breakdown of employees by race, ideally by pay band, on GOV.UK and include it in departmental reports.

3. Encourage employees to disclose: All employers should consider taking positive action* to improve reporting rates amongst their workforce. This should include clearly explaining how supplying data will assist the company in increasing diversity overall.

4. Government legislation: Government should legislate to ensure that all listed companies and businesses employing more than 50 people publish workforce data broken down by race and pay band.

*See [footnote 18]

7. Changing the culture

Organisations should be striving to create a genuine culture of openness and inclusion. There are many parallels between changing workplace cultures to be more inclusive and other types of change management programmes.

Culture change

Organisations should be striving to create a genuine culture of openness and inclusion. There are many parallels between changing workplace cultures to be more inclusive and other types of change management programmes. Change management models vary but many contain core elements of: involving staff in key decisions that affect them; ensuring that the vision and reason for change is communicated effectively; ensuring feedback loops are present and open and that there is senior, accountable ownership of the change. All of these elements are a necessary minimum to change workplace cultures around ethnicity. There are many lessons that can be learnt from other types of culture change programmes across organisations and leaders should approach the issue with the same conviction that change is necessary and achievable.

Unconscious bias training

The workplace has moved on significantly since the 1970s. However, there are still examples of outright racism and responses to the call for evidence identified a number of examples of clear discrimination. Two-thirds of BME individuals who responded to the call for evidence reported that they had experienced racial harassment or bullying in the workplace in the last 5 years. Where this happens, employers should act immediately to deal with the situation. Racism and workplace discrimination are illegal and have no place in a 21st century workplace. No employer can hope to cultivate the rewards of a more inclusive workplace if individuals are specifically targeted because of gender, race or religion. What is more, while we talk about unconscious bias in the system, all too often this language is used to excuse processes that are clearly conscious. Any form of discrimination has to be dealt with, and dealt with quickly. Employees need to feel able to report instances of discrimination without recrimination, and have confidence that action will be taken.

Even when overt discrimination is not present, there remains a lingering bias within the system which continues to disadvantage certain groups. Many times this is conscious though, and sometimes unconscious. Where it is conscious, this does not necessarily mean it is actively there to discriminate against ethnic minorities or other disadvantaged groups. For many businesses, senior managers are busy and have not been able to prioritise this issue, focusing on areas where they have had to act, such as gender equality. For some, processes are retained to support the status quo allowing organisations and individuals to continue hiring in their own image. Either way, this needs to change.

We have seen major strides in terms of gender equality thanks to a more open dialogue and an acceptance that more gender diverse teams benefit the business. Everybody has bias to some extent. We all find it easier to relate to those who are most like ourselves or who come from similar backgrounds. It is important that individuals address this fact by undertaking suitable unconscious bias training, even if this simply identifies to an individual where their conscious biases lie. We understand though that this costs money and while larger companies are already investing in this, for smaller companies it is more difficult. There is a role here for representative organisations such as the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) and the Institute of Directors (IOD) and professional bodies such as the Law Society and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales to provide training or support for their members, even at a very basic level. Bias affects all organisations, large and small, so it is important that all have access to training of some form.

However, where individuals are involved directly in the recruitment process or have a leadership role in an organisation, more targeted training should be delivered to ensure that they are fully aware of how bias may affect their decision making, and how to counter it.

Case study: RBS

In 2015, our Executive Committee committed to rolling out unconscious bias training across the bank as part of building the foundation for our Inclusion agenda; specifically, to improve our awareness of how our biases can influence us to make poor decisions.

Across RBS to date, over 40,000 employees have undertaken the training. As a result of the training,

- 96% of participants would recommend the training to a friend

- 97% report that they will ‘do their job differently’

Some of the tangible ways they have been doing this are by:

- revisiting talent and succession plans with a BAME (and gender) focus;

- requiring more diversity on all shortlists (for example, at least one woman or BAME candidate) and consider more non-traditional candidates for certain roles (such as part time, retirees, carers)

- looking more broadly at who they consider – for example, mentoring more diverse groups of people, specifically BAME and female talent

To support our understanding of the impact of the training, we have put mechanisms in place to track and analyse the recruitment and retention of BAME employees.

Recommendations

5. Free unconscious bias resource online: The government should work with organisations such as the CBI, IOD, Recruitment and Employment Confederation and others to ensure that free, online unconscious bias training is available to everyone in the UK.

6. Mandatory unconscious bias training: All employers should ensure that staff at all levels of the organisation undertake unconscious bias training to address lingering behaviours and attitudes that act as a barrier to a more inclusive workplace.

7. Unconscious bias workshops for executives: Senior management teams, executive boards and those with a role in the recruitment process should go further and undertake more detailed training workshops.

Leadership

The setting of targets will only work if individuals are held responsible for delivering them. Culture change needs to be driven from the top, with senior leaders taking personal responsibility and being held accountable for increasing diversity within their organisations. This does not mean simply identifying one executive to lead, but rather embedding these champions throughout an organisation so that everyone can see a clear pathway to accountability.

I have seen a number of examples throughout this review of organisations where hard working and passionate leaders are trying to embed new processes and targets across an organisation but fail because the very top management of the organisation does not support them with meaningful action. Every board in every large organisation should identify a sponsor for all diversity issues. We have heard too many examples of boards only focusing on gender equality given the specific legislation in place and the fact that positive changes are occurring. This must change and all aspects of diversity need to be given equal weight, with senior individuals held to account where organisations fail to change.

It can be easy for senior executives in any organisation, public or private, to become detached from the reality of the ‘shop floor’. There are many examples of successful CEOs returning to the front line regularly to retain an understanding of the day to day business. Similar initiatives, such as reverse mentoring, can be successful in giving senior management more of an idea of what it is like to be an ethnic minority person in their organisation. This gives senior leaders an opportunity to understand the specific pressures and the first-hand knowledge to support positive action. It also works both ways with junior members of staff securing a board-level sponsor for their future career. The positive feedback I have heard leads me to believe that all senior management should consider undertaking reverse mentoring with someone more junior in the organisation.

It is not just senior managers who need to buy in to this culture change though. Everyone with a role in leading teams and setting a vision should have their success measured, in part, through their commitment to diversity. This will empower people at all levels of an organisation to initiate positive action in the knowledge that it is supported by the business.

Individuals can also do a lot to support their own career progression. Forming relationships and building networks across an organisation can be an important way of seizing opportunities and making sure your talents are recognised. This was identified in responses to the call for evidence with 71% of individual respondent citing a lack of connections to the ‘right people’ as a factor in them not progressing at work. Networking and support was also raised by individuals as the most beneficial intervention they had experienced at work to assist progression in their careers.

Recommendations

8. Executive sponsorship: All businesses that employ more than 50 people should identify a board-level sponsor for all diversity issues, including race. This individual should be held to account for the overall delivery of aspirational targets. In order to ensure this happens, Chairs, CEOs and CFOs should reference what steps they are taking to improve diversity in their statements in the annual report.

9. Diversity as a Key Performance Indicator: Employers should ensure that all leaders have a clear diversity objective included in their annual appraisal to make sure that leaders throughout the organisation take positive action seriously.

10. Reverse mentoring: Senior leaders and executive board members should seek out opportunities to undertake reverse mentoring opportunities with individuals from different ethnic backgrounds in more junior roles. This will help to ensure that they better understand the positive impact diversity can have on a company and the barriers to progression faced by these individuals.

8. Improving processes

The number of working age people from ethnic minority backgrounds is increasing and so employers should be looking to ensure that their recruitment processes do not include any barriers to attracting the best BME talent.

Recruitment and promotion

The number of working age people from ethnic minority backgrounds is increasing and so employers should be looking to ensure that their recruitment processes do not include any barriers to attracting the best BME talent. This is even more important following the referendum result in June. With the UK about to embark on a global charm offensive, businesses will want to make sure that they have the best possible opportunities in working with emerging markets. With such a large, well-educated, motivated diaspora of ethnic minority talent, the opportunities are endless – but only if companies address these underlying barriers.

This includes considering the entry requirements for graduate roles and the wider processes such as the drafting of job specifications and the posting of adverts in locations that attract less diverse applications. It is also important that employers establish inclusive processes for the promotion and reward of staff, to ensure that all their employees have access to the same opportunities.

Many larger organisations now use recruitment agencies to source new employees. This is a great opportunity to ensure that a more diverse pool of talent is considered during the recruitment process, and some agencies even specialise in diverse recruitment. Organisations should set their recruitment agencies clear guidelines for the level of diversity required, taking into account local demographics. Employers should also consider whether any of the required skills or qualifications that are included are acting as an unnecessary barrier to some groups. For example, focusing on individuals from particular schools or universities can result in a smaller, less diverse pool of individuals to consider. Employers should ask for long lists and short lists to be provided with unnecessary data removed until the interview stage. This includes the individual’s name, gender, race, educational establishment and, potentially postcode. This will ensure that individuals from more diverse backgrounds have equal chance of gaining an interview, eliminating any unconscious bias. Where lists are not diverse, they should be rejected outright. With such a diverse working age population, there can be no excuses in the majority of roles for a recruitment agency to fail to provide a suitably diverse list of candidates.

For those organisations recruiting directly, it is important to consider the processes that are in place to attract the best people. Using outdated jargon or incomprehensible language in job adverts can deter some individuals from considering an application. The way an organisation is represented both online and at recruitment fairs has an impact on the type of candidates it attracts. Likewise, deciding where to advertise jobs can also influence who applies. What may have worked in the past in terms of identifying the right candidates may not be the case today. For example, many organisations are now actively recruiting from a broader range of universities, and removing UCAS points requirements to increase the diversity of their candidate pool.

Once applications are received, organisations should consider how unconscious biases can be removed. A number of employers, including the Civil Service, have adopted name-blind recruitment practices to improve diversity at interview. However, while nameblind applications can help secure ethnic minorities (and other disadvantaged groups) an interview, I have heard a number of examples of where it potentially led to greater bias in the interview. Contextualised recruitment can be a useful way of focusing on an applicant’s potential, particularly those who may not have had the opportunity to attend a high performing school or university. By taking into account a candidate’s economic background and personal circumstances when looking at academic achievements, employers can identify talent and potential that might otherwise be missed.

The interview process should also be examined in all organisations to ensure it gives every candidate the best opportunity to show off their talents and potential. Being interviewed is not a natural experience and employers should do everything they can to put the interviewee at their ease so they can showcase their talents. Having something in common with someone in the interview panel can help to put individuals at ease and so where panels are used, these should be diverse wherever possible to prevent unconscious bias affecting selection. This will help individuals from an ethnic minority background to feel more comfortable in the interview.

Employers should also look at their rewards systems. We have heard of countless examples of where ethnic minority staff scored lower than the average in performance appraisals. Recent Business in the Community research showed that BME employees are less likely to be rated in the top 2 performance rating categories compared to White employees. Ethnic minority employees are also much less likely to be identified as having high potential[footnote 19]. Where ethnic minorities appear to be less successful in appraisal systems, employers need to investigate why this is happening. Long standing appraisal and rewards systems can often overlook skills, expertise or potential that may be more prevalent among ethnic minority employees, while overvaluing other qualities that may be more traditional, but have less applicability to the modern workplace.

In short, employers of all sizes, in both the public and private sectors, must ensure that the processes they have in place attract, appoint, develop and reward the very best people. Only by addressing outdated practices and systems can employers hope to benefit from the significant pool of talent available to them. In doing so, employers should consider the different barriers that may affect each individual ethnic group. Grouping all BME staff together as one homogeneous group misses key variances between and within ethnic groups. Organisations should strive to understand cultural and social values across all of their staff, including BME individuals. The process of improving inclusion for employers often begins with understanding more about the people that they employ and what values they hold. Businesses will only succeed when individuals can be themselves in an environment that truly values diversity and inclusion.

Case study: EY

EY uses its data-driven approach to get clear insight into the diversity of its workforce. This underpins its proportional promotion process which seeks to advance employees on a representative basis according to the diversity composition of each job level.

For example, with 20% from BME backgrounds at manager level, EY expects 1 in 5 promotions from manager to senior manager to be from ethnic minorities. The process works on a comply or explain basis: if a business unit fails to comply then its HR team asks for feedback from leaders making promotion decisions on why eligible candidates were unsuccessful and, using that feedback, works to understand why the target is not being achieved. It then supports business leaders to put in place actions that will improve the likelihood of success. An example of one such action is a review of work allocation according to diversity; this is because management believes that promotion follows great work experience and stretching projects, and if project work is allocated in an unequal way then promotions will also be skewed.

The point is to make the promotion process as fair as possible by challenging leaders to make decisions based on employees’ skills and potential, rather than their characteristics or background, or on what the traditional model of a leader looks like. Since the process began 2 years ago, promotions have become more representative: by the most senior career stage we now have 8% BME partners compared with 3% in 2011.

In tandem with this process we monitor the distribution of performance ratings by ethnicity, to ensure that both the highest and the lowest performance ratings are distributed in a representative way: where they are not, they are challenged in the same way.

Key to the success so far has been buy-in from leaders who value support in uncovering unconscious bias and sharing good practice amongst those who make promotion and appraisal ratings decisions.

Procurement and supply chains

Organisations both in the public and private sector spend billions of pounds every year tendering for goods and services to support the delivery of their business. Implementing more inclusive processes internally must be replicated in all areas of the business, including the supply chain. No business will succeed if it makes poor procurement decisions, but that does not always mean choosing the cheapest supplier – it must be about value for money with a focus on the return on investment. Responsible businesses that take diversity seriously perform better. We know that. If a bidding company is committed to making its workplace more inclusive, it will perform better, meaning you will get a better product for your money.

However, not enough emphasis is placed on the non-cash elements of the tendering process. In addition, far too many procurement teams choose to hide behind rigid rules and due processes. This has to change. Successful bidders must be able to show their commitment to diversity and inclusion before being considered for large contracts. There are many ways organisations could do this, from recognising the social and economic importance of diverse workforces in their social value policies, to more direct positive action.

This is one area where the public sector should take the lead. Where taxpayers’ money is spent, it should be spent responsibly and in a way that benefits all citizens in the UK. Public sector organisations must seek to drive lasting change through their procurement processes, improving behaviours and helping to reduce inequalities in the labour market. There is much that can be changed now to improve the process. The guidance produced to support public procurement suggests that “involvement of persons from a disadvantaged group in the production process” can be a legitimate consideration when assessing the best price–quality ratio of a bid – this should be actively encouraged. Companies bidding for government contracts must be compelled to show their commitment to diversity and inclusion before being considered for contracts. Going forward, as the government considers how to disentangle itself from a myriad of EU rules on procurement, it must develop a new process – one that drives positive change and works for everyone in the UK.

Recommendations

11. Reject non-diverse lists: When recruiting through a third party or recruitment agency, employers in both the public and private sector should ensure proportional representation on lists. Long and short lists that are not reflective of the local working age population should be rejected.

12. Challenge school and university selection bias: All employers should critically examine entry requirements into their business, focusing on potential achievement and not simply which university or school the individual went to.

13. Use relevant and appropriate language in job specifications: Employers should ensure that job specifications are drafted in plain English and provide an accurate reflection of essential and desirable skills to ensure applications from a wider set of individuals. They should also consider how their organisation is portrayed online and at recruitment fairs to attract a diverse pool of applicants.

14. Diverse interview panels: Larger employers should ensure that the selection and interview process is undertaken by more than one person. Wherever possible, this panel should include individuals from different backgrounds to help eliminate any lingering unconscious bias.

15. Transparent and fair reward and recognition: Employers should ensure that all elements of reward and recognition, from appraisals to bonuses should reflect the racial diversity of the organisation.

16. Diversity in supply chains: All organisations (public and private) should use contracts and supply chains to promote diversity, ensuring that contracts are awarded to bidders who show a real commitment to diversity and inclusion.

9. Supporting progression

Businesses must help to improve social mobility by being more inclusive in whom they give opportunities to.

Transparency within organisations

Businesses must help to improve social mobility by being more inclusive in whom they give opportunities to. As we have seen, the benefits are there for the business in making sure the right people get to the right place within the organisation, taking full advantage of the available talent. However, supporting greater social mobility is also the socially responsible thing to do, improving community cohesion and setting the country up for success in the future.

This starts from the work experience opportunities that a company provides. High quality work experience and internships are particularly helpful in giving young people the opportunity to see what a particular career entails as well as giving them the very basics of how to operate in the workplace. In some sectors, internships are now a vital part of the recruitment process, with employers only hiring individuals who have shown an interest in the business. However, these opportunities have to be available to everyone and not just the select, well-connected few. Unpaid internships are not only often unethical, but they also act as substantial barrier to those without the financial support to undertake them. Likewise, the provision of internships and work experience more generally can be prohibitive when only made available to the select few. Opportunities should be extended beyond the sons and daughters of senior executives, into the schools and universities supplying the future talent pipeline. They should be advertised widely to attract a diverse, talented group of individuals to help support lasting improvements.

Lack of transparency has emerged as a significant theme in discussions with individuals. As we have seen, unnecessary jargon or poor advertising can lead to individuals not being aware of a job opportunity, or even if they are, not actually understanding what the job entails. However, once someone from a BME background does get a job, knowing what the right steps are to progress can be even more of a challenge. While a number of employers have clear induction processes in place, many of these focus on the factual element of the role – what needs to be done, for whom and by when – rather than information on how to succeed in the company.

For many, the career ladder that is so obvious to some is a complete mystery. For them, the pathway to the top is unclear, with confusion over which job to seek out at what point in a career. Certain skills and experience may be particularly valued in senior executives. As a result, many senior executives have had similar career paths which, if followed, could provide opportunities for a more diverse set of individuals. All employers should make their own organisation’s career ladder more transparent during the induction process and beyond to ensure that everyone within the organisation has equal opportunity to succeed. Senior executives should be transparent about their own job history so that those wishing to follow in the footsteps of those who have succeeded can see the pathway that has been followed. Employers should also be clear about how the promotion and reward processes work so that everyone knows what they need to do to excel and progress in their role and organisation.

Case study: Arts Council

The Critical Mass programme at the Royal Court Theatre is aimed at emerging or developing BAME playwrights and creates structured opportunities in creative writing and skills development, along with showcasing their work and linking them with relevant sector agencies and organisations. Previous participants have gone on to have their work performed by professional actors.

Case study: Taylor Bennett Foundation

The PR industry struggles to attract and recruit young people from ethnically diverse backgrounds. According to the 2013 PRCA and PR Week Census only 8% of PR practitioners are non-White. The Foundation is a model for how other industries can engage with the imperative of diversity and the challenge of recruitment.

The Foundation provides 10-week intensive training courses delivered in partnership with top tier PR agencies and businesses. Trainees are paid a training allowance (the equivalent of the minimum wage) plus travel expenses.

As of September 2016, 167 trainees have gone through the programme since launch in 2008.

Over 400 graduates have had the opportunity to attend a full day’s assessment by experienced head-hunters and PR professionals and receive personal feedback on their performance, regardless of their success in securing a place on the programme.

Over 100 organisations have contributed their time or financial support to the programme, typically on a repeat basis.

Recommendations

17. Diversity from work experience level: Employers should seek out opportunities to provide work experience to a more diverse selection of individuals, looking beyond their standard social demographic. This includes stopping the practice of unpaid or unadvertised internships.

18. Transparency on career pathways: All employers should ensure that new entrants to the organisation receive a proper induction. Basic information should be available to all employees about how the career ladder works in the organisation, including pay and reward guidelines and clear information on how promotions work.

19. Explain how success has been achieved: Senior managers should publish their job history internally (in a brief, LinkedIn style profile) so that junior members of the workforce can see what a successful career path looks like.

Network of support

There is no substitute for formal and informal networks. These can provide additional support when applying for jobs or seeking out opportunities as well as giving ethnic minorities a voice at those meetings where career decisions are made. Employers should do everything they can to create an environment where these informal networks can prosper. However, networks need to be more than a simple talking shop and be placed at the heart of any successful organisation.

Some of the best examples I have seen are where networks support the business rather than simply operate as a corporate ‘nice-to-have’. When operated well, networks do not just make individuals feel more welcome in an organisation; they can provide the expertise a company needs to have a competitive advantage in the market place. In addition, networks can provide an organisation with insights to how to address internal issues, such as developing policies for particular festivals or public holidays. Some of the best examples I have seen suggest networks should not be exclusive to particular groups, but open to all who want to do more and understand more about a particular issue. All employers should consider how they can embed professional networks within their organisation so they attract their very best people. That way they will be able to harness this expertise to improve their business outcomes.

As well as the reverse mentoring recommended earlier, more traditional mentoring schemes should be put in place. Alongside effective sponsorship schemes, this can improve career support and ensure that employers are making the most of the talent they have within their organisations. These schemes should be open to everybody, regardless of race or religion, so that the pressures of supporting more junior staff do not fall to the small number of ethnic minorities who have succeeded in reaching positions of leadership.

Case study: Scottish Trades Union (STUC) Congress

The STUC has run a mentoring project in Further and Higher Education in Scotland for BME staff members, to support them to move into more senior positions.

This scheme was designed to support the advancement of BME staff through training and peer mentoring. Core to the success of such schemes, however, is a parallel focus on institutional barriers to advancement and recognition from senior management that within the organisation BME workers are overrepresented in the lower grades. This organisational focus, combined with specific training for managers, training and support for BME workers and a shared desire to change outcomes in the organisation, can produce meaningful change that benefits both workers and employers. Feedback from those who took part showed that:

- 73% reported an increase in personal confidence

- 64% reported increased confidence in their jobs

- 54% felt that participation had helped them develop professionally

Of those who responded to the final monitoring requests (after completion of the project) 60% had applied for new roles at the same FE/HE institution or at another FE/HE institution.

Recommendations

20. Establish inclusive networks: Employers should support the establishment of networks and encourage individuals to participate, working with organisers to find a suitable way of incorporating their objectives into the mission of the company.

21. Provide mentoring and sponsorship: Employers should establish mentoring and sponsorship schemes internally, which are available to anyone who wants them.

10. Inclusive workplaces

It is OK to talk about race. Celebrating the differences between people is what makes the most successful companies succeed, utilising the plethora of skills and experiences at their disposal to greatest effect.

Language

It is OK to talk about race. Celebrating the differences between people is what makes the most successful companies succeed, utilising the plethora of skills and experiences at their disposal to greatest effect. We have seen the workplace change in recent years with gender issues now discussed more freely. I have no doubt that this has helped to move the debate on and deliver improvements for women. For us to succeed in a similar way and address race inequalities requires an approach that embraces open discussion.

Employers should consider the best way to address this in their own organisations. However, there is a role here for representative organisations and professional bodies, supported by government which should produce a basic guide to what the law allows and even encourages. This should outline the benefits of positive action and some examples of what has worked. There have been successes in terms of guides on faith produced by non-governmental groups on issues such as of Judaism and Islam. The Commission for Racial Equality previously produced an equality code of practice which included practical advice for the workplace, such as common language to avoid misunderstanding. A number of employers have suggested that these guides have been helpful in developing their own internal policies and so there is clearly an opportunity here to support businesses who want to do more.

Recommendation

22. A guide to talking about race: Government should work with employer representatives and third sector organisations to develop a simple guide on how to discuss race in the workplace.

Ongoing awareness

It is important that employers who want to take positive action have easy access to the materials and examples they need to make the right decisions. Where employers do take effective positive action, these examples should be shared and the most inclusive employers should be rewarded. To achieve this, there should be a single portal through which examples can be shared and discussed to provide the support that many companies want.

We should also consider the best ways to celebrate and reward those employers who do take positive action and make a change. The Race for Opportunity awards have been running for a number of years and highlight the success of individuals and employers who have improved and promoted race diversity. These awards are important, well respected, and must continue. However, there is scope to build on this success through the publication of a list of the best racially inclusive employers. Stonewall has been successfully doing something similar for a number of years and their lists have become a beacon for many of those in the LGBT community when considering a future career. A similar approach, tied into the Race for Opportunity awards, has the potential to do the same.

Institutional funds also have a role to play in ensuring lasting change, driving change in the FTSE companies they have holdings in. It is important that government understands what these funds are doing now to improve diversity both within their own organisations and the companies they own. This is one element of a wider role for government in ensuring lasting change is embedded across the UK labour market and it is imperative that progress against my recommendations is revisited in 12 months.

Recommendations

23. An online portal of best practice: Government should work with Business in the Community to establish an online portal for employers to source the information and resources they need to take effective positive action.

24. A list of the top 100 BME employers in the UK: Business in the Community should establish a list of the top 100 BME employers, similar to the Stonewall approach for LGBT employers, to identify the best employers in terms of diversity.

25. Requests for diversity policies: Government to write to all institutional funds who have holdings in FTSE companies and ask them for their policies on diversity and inclusion and how they ensure as owners of companies that the representation of BME individuals is considered across the employee base of the companies where they hold investments.

26. One year on review: Government should assess the extent to which the recommendations in this review have been implemented, and take necessary action where required.

11. Conclusion

The time for talking is over. Now is the time to act. It will require concerted and sustained effort from all of us but the solutions are already there, if we only choose to apply them.

That is why I agreed to carry out this review. The business case is there for all to see. But providing equal opportunities to people of all backgrounds is also, quite simply, the right thing to do. By implementing these recommendations, we have a huge opportunity to both raise the aspirations and achievements of so many talented individuals, and also to deliver an enormous boost to the long-term economic position of the UK.

List of recommendations

-

Published, aspirational targets: Listed companies and all businesses and public bodies with more than 50 employees should publish 5-year aspirational targets and report against these annually.

-

Publicly available data: Listed companies and all businesses and public bodies with more than 50 employees should publish a breakdown of employees by race and pay band.

-

Encourage employees to disclose: All employers should take positive action to improve reporting rates amongst their workforce, explaining why supplying data will improve diversity and the business as a whole.

-

Government legislation: Government should legislate to ensure that all listed companies and businesses employing more than 50 people publish workforce data broken down by race and pay band.

-

Free unconscious bias resource online: The Government should create a free, online unconscious bias training resource available to everyone in the UK.

-

Mandatory unconscious bias training: All organisations should ensure that all employees undertake unconscious bias training.

-

Unconscious bias workshops for executives: Senior management teams, executive boards and those with a role in the recruitment process should go further and undertake more comprehensive workshops that tackle bias.

-

Executive sponsorship: All businesses that employ more than 50 people should identify a board-level sponsor for all diversity issues, including race. This individual should be held to account for the overall delivery of aspirational targets. In order to ensure this happens, Chairs, CEOs and CFOs should reference what steps they are taking to improve diversity in their statements in the annual report.

-