Race in the workplace: The McGregor-Smith review - annexes

Published 28 February 2017

These are the annexes to ‘Race in the workplace: The McGregor-Smith review’. Read the main report.

Note: The following footnotes relate to the main report and are included here for completeness [footnote 1], [footnote 2], [footnote 3], [footnote 4], [footnote 5], [footnote 6], [footnote 7], [footnote 8], [footnote 9], [footnote 10], [footnote 11], [footnote 12], [footnote 13], [footnote 14], [footnote 15], [footnote 16], [footnote 17], [footnote 18], [footnote 19].

a. Best practice case studies

It would be wrong to suggest that nothing is being done to improve racial diversity in the workplace. Throughout this review, a number of employers have identified initiatives that they have implemented which have delivered real change in the workplace. Going forward, it will be important that the new online portal becomes a vehicle through which these good examples can be shared. However, as a starter, some case studies are included below to support employers in taking positive action in the workplace.

Case study: University of Birmingham – Improving employment outcomes for students

In 2011 the University of Birmingham ran a project to identify the issues affecting employment outcomes for BME students. This involved in-depth consultation with BME learners through a programme of focus groups and interviews.

The feedback the University received indicated that the students would value access to BME role models and better opportunities for networking, especially as many were the first from their family or community to go to University. Accordingly, the project trialled a mentoring scheme through which local BME role models provided direct, interactive and personal employment support to students. Many of the students who took part left the University to work in the areas of their choice. Their mentors had enabled them to make useful fruitful connections. For example – a student who wanted to be a journalist now works for The Voice in London as a result of the support from her mentor, herself a Sky and BBC journalist from BME background, having helped her publish some online articles in the Guardian. Another worked with a community business mentor and they set up their own IT business.

On the basis of this successful pilot, the University launched a full-scale BME mentoring scheme which gives students the opportunity to meet and network with successful BME business and community leaders from the surrounding area. A peer mentoring programme was also developed for students and eventually, running alongside that, a BME ambassador scheme aimed at supporting BME students’ success and attainment. One result is a network of over 200 BME students meeting reguarly and working to promote race equality in their Schools. For the individual students, the impact seems positive. They meet others they can easily relate to and they have an important role to perform at the University. The University planned to launch an impact and evaluation tool in October 2016 to measure the impact of this work more rigorously.

The study also revealed that BME students felt they were part of visible and cultural minorities and that this impacted their ability to ‘find a voice’. To tackle these issues, a website dedicated to supporting the success of BME students was launched in 2015, with an additional website for academics and staff launched shortly afterwards. These websites host the BME Ambassador Toolkit which was designed as a training resource for students and staff.

In 2016 the University’s Equality Diversity ‘Champions’ who are both academic and non-academic staff, worked with over 200 BME ‘Student Ambassadors’ to better understand the BME student experience and develop an action plan to address any issues. This project is supported by the Higher Education Academy as part of its Strategic Enhancement Programme for Retention and Attainment. The Diversity Champions also engage in dialogue with the student ambassadors in order to facilitate more inclusion in the curriculum and the University generally. The aim in the current academic year is to ensure a more systematic approach to this work. For example, the dialogue has made a positive change in the school of Mathematics. Students produced materials celebrating the work of Mathematicians from different cultures and countries and used them at induction. They also established a race equality group within Maths and held socials and study meetings. They invited speakers from diverse backgrounds to be part of the school’s speaker programme. They elected an equality and diversity representative from the students. In English, American and Canadian studies (EDACS) students informed changes to the first year curriculum, changed the School’s displays to be more inclusive, held film nights, had socials and wrote a blog.

Case study: Russell Group universities – Mentoring and development programmes

iLead is a leadership programme for BME academic, research, technical and professional support staff developed by Imperial College London and run from 2008 to 2011. The course involved 4 modules, delivered over 6 months, including a 2-day residential workshop. The programme focussed on how to develop careers, exploring potential barriers to success and understanding effective leadership and management techniques. A survey of iLead participants revealed that 10 had applied for higher grade jobs internally, 5 succeeded in obtaining positions and 7 indicated they had obtained higher grade positions through promotion or other means, such as secondment. 9 of 11 participants who applied for jobs externally obtained new positions. The success of the iLead programme led to it being a model for a pilot scheme across the Higher Education sector in 2010 called Stellar HE. In 2013 the universities of Birmingham, Nottingham and London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) were all offering Stellar HE to their staff.

Imperial College London now delivers IMPACT (Imperial Positive about Cultural Talent), which was established in 2014. IMPACT is a leadership and personal effectiveness programme for BAME academic and support staff. It is an Institute of Leadership and Management (ILM) accredited programme of 6 workshops run over 6 months. Currently, 27 senior leaders and managers participate as IMPACT mentors. All delegates recieve post-programme coaching from senior managers in order to provide executive-style coaching. Being able to engage with senior managers throughout and after the programme has led to a growth of confidence and morale with IMPACT delegates.

As of June 2016, IMPACT has had 51 BAME delegates, with cohort numbers increasing from 15 delegates to 21 per programme. All senior managers and line managers are held accountable through the delegates’ personal development review meetings which are recorded and sent to the ILM. IMPACT is also being delivered at LSE by the Imperial College’s EDIC team, the programme is entitled CADET.

IMPACT has been shortlisted for Business in the Community’s Race Equality Campaign Awards in 2016, for developing talent.

Case study: NASUWT (teachers’ union) – Example of BME networks/ consultation conference

The National Association of Schoolmasters and Union of Women Teachers (NASUWT) is a TUC-affiliated trade union representing teachers, including head teachers, throughout the United Kingdom.

The NASUWT hosts annually the largest network of BME teachers and head teachers, through its annual programme of consultation conferences. This provides critical information on the experiences of BME teachers.

The NASUWT’s annual BME Teachers’ Consultation Conference, now the largest gathering of its kind in Europe, provides rich data and information on the experiences of BME teachers and head teachers across the UK. Each event consists of a number of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) sessions covering a variety of subjects.

Research commissioned by the NASUWT demonstrates discriminatory practices within Performance Management and Capability processes. For the past 4 to 5 years we have provided CPD on Managing your Performance Management, providing information on understanding the performance management process and strategies for avoiding discriminatory practices. Feedback demonstrates that these sessions have empowered BME teachers to engage constructively in the performance management process, increased awareness of the risks around discrimination and thus supported their career progression. This process has also given us rich information and evidence for discussions with Education Ministers on matters such as performance management. Indeed the NASUWT worked positively with the DfE on providing checklists for avoiding discriminatory practices in pay and performance management processes for all schools.

We evaluate the outcomes and impact of each event by monitoring teachers’ experiences of these consultation conferences. Comments from participants include: ‘this has built my self-esteem as a BME teacher and I now have knowledge of how to tackle workplace bullying’; ‘Challenging and standing up for my rights is one of the things I will take from this conference’; ‘The insight and experiences was very valuable and I realised I’m not the only one who has experienced racism’.

A large proportion of BME teachers are supply teachers or have temporary contracts. They report experiences of prejudice in obtaining full time or permanent work in schools. As a result we work with supply agencies to provide advice on good/nondiscriminatory employment practices process and also provide personal development sessions at these conferences on interview techniques, writing CVs and understanding their employment rights. Many have returned stating that the knowledge they have obtained at these events have been useful in asserting their rights and improving their confidence in seeking employment.

Case study: Lloyds Banking Group – Data initiatives to improve disclosure and diversity champions

At Lloyds Banking Group we have launched regular communication campaigns, sponsored by senior leadership, to encourage colleagues to complete all personal details (including ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation) on our HR system. We have been able to link the request to complete personal data with our Group purpose of Helping Britain Prosper through better representing the customers and communities we serve, whilst also improving the workplace for everyone – giving colleagues a positive reason to share this information. At launch we supported the communication campaign by equipping leadership and line managers with a guidance pack, including FAQs, to help them explain to colleagues the positive benefits of Lloyds Banking Group having accurate data around the diversity of our workforce. Since the launch of our communications campaign we have seen a 4% increase in completion of ethnic origin data across our full employee population, equating to over 3,000 colleagues voluntarily updating their details.

At Lloyds Banking Group we are firmly committed to improving the representation of BAME individuals at all levels, particularly in our senior management population, to better represent the customers and communities we serve. We have invested significant time and resource to analysing our internal data, qualitative and quantitative, to understand the barriers and opportunities for BAME colleagues. We know from this data that we are seeing considerable improvements in hiring and promoting BAME colleagues.

Our Career Development Programme for ethnic minority colleagues receives consistently positive feedback from delegates, and we have been able to show that the promotion rate for colleagues going through the programme is significantly higher than for BAME colleagues who have not been through it.

Appointing ‘diversity champions’ or advocates in each business unit has also been a highly effective strategy, coupled with being able to offer a practical programme of support for BAME colleagues. Our diversity champions have been able to raise the profile of our Inclusion & Diversity ambitions, including the availability of specific development opportunities, across the business.

Case study: University and College Union (UCU) – Engaging with BME staff to understand the obstacles to progression and response to this

UCU has recently conducted a survey of its BME staff in both further and higher education, with a range of questions about their own experiences in the workplace. The survey report, The experiences of Black and Minority Ethnic staff in further and higher education, was published in February 2016 and showed that:

An overwhelming majority (90%) of staff felt they had faced barriers to promotion. Half (50%) said they had not been fully informed of the process for applying for promotion, and three-fifths (59%) reported that senior managers and colleagues had not supported them to progress their career;

- 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said that they had ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ been subject to bullying and harassment from managers, and 68% said the same was true of colleagues;

- nearly four-fifths (78%) of respondents across post-16 education reported they were ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ excluded from decision making;

- four-fifths (82%) of respondents across both sectors said they were subjected to cultural insensitivity

The survey also asked BME staff which measures they felt would be most effective in tackling workplace racism. The measures that received most support were ‘effective sanctions against perpetrators of racism’ (68.3%) and ‘improved support for BME staff’ (61%), as well as ‘training for senior staff’ (56.3%).

To accompany the report, UCU produced a short film, ‘Witness’, detailing some of the issues which BME staff face in the workplace. Many of those interviewed reported experiencing ‘covert’ or ‘subliminal’ examples of racism, and this was identified as being harder to tackle than ‘overt’ racism such as namecalling. Interviewees also suggested that many working in the education sector believe it to be quite a liberal environment which supports equality. However, this belief can actually mean that when people draw attention to what they consider to be racism or discrimination, they are taken less seriously.

In response to the challenges faced by BME staff in higher education, the Equality Challenge Unit has introduced a Race Equality Charter (REC), which aims to change institutional culture. Member institutions develop initiatives and solutions for action, and can apply for a Bronze or Silver REC award, depending on their level of progress.

Case study: Ernst & Young (EY) – Inclusive leadership programme and promotion policies

Educating the wider firm

Our long-term work on building an inclusive culture is vital to the success of our firm’s vision. So having identified the need for intervention, we are implementing an Inclusive Leadership Programme (ILP).

The ILP aims to help our people to understand the impact of their own behaviours and how to change those behaviours to enable individuals to achieve their potential. It covers 3 main areas: unconscious bias (commonly addressed by many organisations); insider/outsider dynamics; and intent/impact.

Culture change takes time – and we are therefore patient, while at the same time impatient to interrupt the status quo. The key for the success of the programme to date has been the role modelling from our leadership team. The ownership and accountability lies with them and not with a diversity and inclusiveness team. What we mean is:

- our board challenges the proportion of BME senior promotions and challenges whether we achieve our target to admit 10% BME partners every year

- our HR team challenges the representation of BME people on our leadership programmes

- our resourcing team challenges the way work is allocated to our BME team members

- our recruitment teams have set targets for recruitment of BME people at all levels

The language of inclusion is starting to be used more widely; especially the concept of insiders and outsiders, affinity and confirmation bias, and the phrase ‘interrupt the status quo’. We are starting to use action planning that starts “I will take Jyoti to the AB meeting on Thursday” rather than “We should take more diverse junior team members to client meetings”.

Since the inception of the ILP, 94% of Partners and just over 1,500 of the manager population and above have undertaken the programme. We have seen an increase in BME representation at each level of the firm. Our BME partner representation has gone up from 3% in 2012 to 8% in 2016 and more of our BME population are receiving high performance ratings.

Still, we are not complacent as there is much work to do, but we are confident that including all of our people in the challenge to change will eventually create a more inclusive culture.

Robust performance appraisal and promotion policies

EY is a professional services firm that uses its data-driven approach to get clear insight into the diversity of its workforce. This underpins its proportional promotion process which seeks to advance employees on a representative basis according to the diversity composition of each job level.

For example, with 20% from BME backgrounds at manager level, EY expects 1 in 5 promotions from manager to senior manager to be from ethnic minorities. The process works on a comply or explain basis; if a business unit fails to comply then its HR teams ask for feedback from leaders making promotion decisions on why eligible candidates were unsuccessful and using that feedback works to understand why the target is not being achieved. It then supports business leaders to put in place actions that will improve the likelihood of success. An example of one such action is a review of work allocation according to diversity; this is because they believe that promotion follows great work experience and stretching projects, and if project work is allocated in an unequal way then promotions will also be skewed.

The point is to make the promotion process as fair as possible by challenging leaders to make decisions based on employees’ skills and potential, rather than their characteristics or background, or on what the traditional model of a leader looks like. Since the process began 2 years ago, promotions have become more representative: by the most senior career stage we now have 8% BME partners compared to 3% in 2011.

In tandem with this process we monitor the distribution of performance ratings by ethnicity, to ensure that both the highest and the lowest performance ratings are distributed in a representative way: where they are not, they are challenged in the same way.

Key to the success so far has been buy-in from leaders who value support in uncovering unconscious bias and sharing good practice amongst those who make promotion and appraisal ratings decisions.

Case study: Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC) – Mentoring and training to support career progression

The STUC believes that the clustering of BME employees in lower grades is a clear area of concern in the Scottish economy. The STUC has been involved in running mentoring and training schemes for BME workers to support career progression in workplaces across Scotland. The STUC Black Workers’ Committee has, with the support of GMB Scotland and Scottish Union Learning, been running ‘Moving into Management’ courses for BME workers in Scotland. The Committee has organised a series of 4 courses that have provided 62 learning places to BME workers across Scotland. These courses have not only focused on providing skills for advancement within the workplace but have also encouraged peer to peer mentoring that allows the outcomes of the course to be pursued even when the course is finished. A key element to the training was a specific focus on racism, and the direct support that was offered around building networks and resilience.

To date the course has proved very popular, with places on the most recent course being filled in a matter of days. They have also been evaluated very well, with many participants finding the learning extremely valuable. From the feedback received we have also heard specific examples of workers gaining promotion as a result of the course and the skills gained from the learning.

The STUC has also run a mentoring project in Further and Higher Education (FE/HE) in Scotland for BME staff members, to support them to move into more senior positions. This scheme was designed to support the advancement of BME staff through training and peer mentoring. Core to the success of such schemes, however, is a parallel focus on institutional barriers to advancement and recognition from senior management that within the organisation BME workers are over-represented in the lower grades.This organisational focus combined with specific training for managers, training and support for BME workers and a shared desire to change outcomes in the organisation, can produce meaningful change that benefits both workers and employers. Feedback from those who took part showed that:

- 73% reported an increase in personal confidence

- 64% reported increased confidence in their jobs

- 54% felt that participation had helped them develop professionally

Of those who responded to the final monitoring requests (after completion of the project) 60% had applied for new roles at the same FE/HE institution or at another FE/HE institution.

Case study: Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) – Unconscious bias training

To help understand the impact of unconscious bias on our people and the organisation, in 2014, RBS undertook unconscious bias testing (across the UK and internationally) around disability, sexual orientation, age, ethnicity and gender leadership. The purpose of this was to understand how unconscious bias was affecting the organsiation and what training we could introduce to help mitigate against it.

From the findings, RBS created a tailored training programme with targeted interventions aimed at each level of the organisation. This programme consisted of a workshop for senior leaders, a webinar for those with managerial responsibilities, and scenario based e-learning for all employees.

In 2015, our Executive Committee was dedicated to rolling out unconscious bias training across the bank as part of building the foundation for our Inclusion agenda; specifically, to improve our awareness of how our biases can influence us to make poor decisions.

Since introducing the training, across RBS to date, over 40,000 employees have undertaken the training. As a result of the training,

- 96% of participants would recommend the training to a friend

- 97% report that they will ‘do their job differently’

Some of the tangible ways they have been doing this are by:

- revisiting talent and succession plans with a BAME (and gender) focus

- requiring more diversity on all shortlists (for example, at least one woman or BAME candidate) and consider more non-traditional candidates for certain roles (for example, part time, retirees, carers)

- looking more broadly at who they consider for example, mentoring more diverse groups of people, specifically BAME and female talent

To support our understanding of the impact of the training, we have put mechanisms in place to track and analyse the recruitment and retention of BAME employees.

We do recognise that there is no magic wand or silver bullet. Therefore, the unconscious bias training is only one element in a wider inclusion programme of work. This training is providing the fundamental foundation for future areas of the Inclusion agenda and is part of a wider range of initiatives across the bank.

The business impact of the Unconscious Bias training

Examples outlined in the feedback received to date demonstrate the impact the unconscious bias training is having: building a stronger pipeline of BAME individuals, improvements in our recruitment and performance management/promotion processes and creating an environment where employees feel they can be themselves. By helping individuals be more aware of their biases, the training is driving positive change across the organisation.

Overall, the feedback shows that the training is affirming how internal reflection and awareness can help people approach their day to day activity differently; helping managers to mitigate their bias in their leadership and have a positive impact on colleague and customer engagement. For example:

Leadership

Strengthening leadership actions and positively influencing decision making – helping leaders become more reflective and considerate in how they lead, the tone they set, and the decisions they make:

- Leaders are more aware of how their behaviours affect the work environment. Leaders are committing to role model an unconscious bias approach, leading by example; being mindful of the language used, making more considered decisions, and challenging inappropriate behaviour.

Transforming the way we build and develop teams using techniques from Determined to Lead (our leadership programme):

- Leaders are reviewing their team’s strengths to provide more stretching development opportunities based on each individual’s needs and ensure each individual has the clarity and capability to complete the required task;

- Openly discussing unconscious bias in team meetings, using techniques from Determined to Lead to embed key messages – for example, looking at individuals’ motivational drivers to help the team learn from each other and work together more effectively, valuing the differences people bring to their teams, and improving coaching techniques to embed the learning.

Recruitment and retention

Changing recruitment practices, reviewing talent development and better performance management:

- revisiting talent and succession plans with a new perspective

- adopting a more joined up approach with their peers to create a plan that is more inclusive of different people

- banning same gender panels, requiring more diversity on all shortlists (for example, at least one woman or BAME candidate), and considering more non-traditional candidates for certain roles (for example, part time, retirees, carers)

- looking more broadly at who they consider talent – for example, mentoring more diverse groups of people, specifically BAME and female talent

Case study: NHS – Actions to drive race equality

NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard

The NHS has a particular responsibility to address race inequality in employment since we now have convincing evidence of the scale of race discrimination, and the impact this has on NHS organisations, staff and patient care. That is why the NHS Equality and Diversity Council, which brings together all major national bodies in the NHS, has for the first time in the history of the NHS supported a contractual requirement to drive race equality in the employment of NHS staff.

The Workforce Race Equality Standard, as of 1 April 2015, is written into the NHS Standard Contract and requires all NHS providers, except the very smallest, to collect, analyse and publish workforce data on the proportions of NHS staff from BME backgrounds across all professions in every grade, including senior grades.

There are also contractual requirements to:

- publish the proportion of Trust Board members from BME backgrounds compared to the proportion of the workforce from such backgrounds

- publish the relative likelihood of BME staff being appointed once shortlisted compared to the likelihood of White staff being appointed once shortlisted; *collect, analyse and publish the relative likelihood of BME staff accessing non-mandatory training, including that which is designed to improve their career opportunities

- the purpose of collecting, analysing and publishing this data is so that NHS providers meet the new contractual requirement to close the gap between the experience and treatment of BME NHS staff and White NHS staff

- in addition, a new assessment framework for Clinical Commissioning Groups will enable them to better monitor this contract. We expect Trust Boards to consider this data and publish action plans on how the gaps identified will be closed. The Care Quality Commission, for the very first time, has included consideration of whether NHS providers are implementing the Workforce Race Equality Standard into its ‘well led’ domain on inspections. This is because healthcare organisations that are failing their BME staff may well be at risk of not being well led organisations.

- the national contractual requirement is to close the gap in treatment and experience against the 9 indicators of the Workforce Race Equality Standard. We expect individual NHS organisations to set local targets on precisely how they will close the gaps identified and they know that these will be monitored and inspected against nationally. We know that some Trusts are developing innovative and effective evidence-based approaches to making sustainable progress because they recognise the benefits to staff and patients of doing so. The contractual and regulatory framework which is now in place seeks to ensure that all NHS providers make such progress.

- the Equality and Diversity Council will, from time to time, be publishing reports on progress made against the NHS staff survey findings, 4 of which helps to form part of the Standard which we expect will focus Board attention. This government is determined to tackle the discrimination against BME staff in the NHS since it not only adversely impacts on staff but on the care provided to patients.

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (BTHFT) employs around 5,500 people. It is a large acute hospital serving a population of over half a million. The population of Bradford is ethnically diverse, with 33% BME population, 27% of whom are from Asian or Asian British heritage. The district has the largest proportion of people of Pakistani ethnic origin (20.3%) in England.

In 2012, the Trust began mapping the comparative success of White and BME shortlisted candidates who were successful in getting jobs. It found that across all posts, White candidates had a 1 in 5 chance of being appointed, while BME candidates had a 1 in 8 chance. At the senior pay bands in the Trust (Bands 8 and 9) BME shortlisted candidates had a 1 in 17 chance of appointment compared with one in 4 for White candidates. This position worsened between April 2012 and March 2013 when no BME shortlisted candidates were appointed in the previous 12 months. At least 4 BME candidates should have been appointed to these Bands, if other things had been equal.

The Trust Board was determined this must change. Equality briefings were devised for all senior managers with responsibility for managing teams, chairing recruitment panels and undertaking disciplinary action, grievance or investigation processes. Briefings include the data outlined above and looked in detail at potential reasons for the disparity in outcomes for White and BME candidates, including looking at conscious and unconscious bias. When no BME people had been appointed at Bands 8 and 9 in 2012 to 2013, further action was taken:

- all posts had to be externally advertised unless organisation change applied

- the Head of Equality or Assistant Director of Human Resources sat on all interview panels for these posts for a trial period to determine whether there was any evidence of discriminatory practice

- the Head of Equality was to contact every BME who had been shortlisted but failed to attend interview to determine whether there were any patterns to non-attendance

The vast majority of the equality briefings took place between April and September 2013. In that time the chance of White and BME people being appointed was exactly the same at 1 in 4 chance. Unfortunately the positive effect was not sustained and the employment chances fell away to one in 14. As a result of the slippage in performance, in February 2015, the Board of Directors set a target for our workforce to be made up of 35% BME staff by September 2025. They monitor the employment position of BME staff in relation to overall staffing numbers, senior manager numbers, promotion and turnover. Every 6 months the Board sees the progress made on the numbers and position of BME people in our workforce. To reinforce the importance the Trust places on this initiative, each Division is performance managed against the targets every 6 months. The first 12 months data is encouraging:

- overall staffing numbers – increased from 24.7% to 26.8%

- senior manager numbers – increased from 7.6% to 10.2%

- turnover – lower numbers of BME leaving than might be expected at 22.3%

Case study: National Union of Teachers – Development programme for BME teachers

Equal Access to Promotion (EAP) is a professional development programme specifically designed to support greater promotion pathways for Black teachers. It is open to school-based Black teachers with middle management/leadership roles and responsibilities who wish to develop their leadership skills and understanding and/or are considering taking on further leadership responsibilities. To be eligible to apply applicants need to be in their fourth to twelfth years of teaching.

The programme has been successful and evaluations were very positive. Teachers confirmed that motivation and confidence building were some of the identified needs the programme had met. They considered EAP to be more relevant to meeting their personal development needs than generic leadership development programmes. Teachers’ comments also confirmed that they consider EAP to be of very high quality in focusing them in the right direction towards career progression.

Teachers rated very highly the provision of a safe, non-judgemental and nurturing environment, which gave them the needed opportunity to learn and practise new skills and capabilities. Teachers also commented positively about the opportunities offered by the programme to network with other colleagues of similar backgrounds and experiences. The programme filled a gap in that they found access to a support group with whom they could share their work and career with positive regard and respect was very comforting and reassuring.

Of all the value added discerned in participants’ comments, the availability of role models and mentors in the form of motivating and inspiring practising Black head teachers and school leaders as facilitators on the programme stood out. Most participants rated this as the most important and unique element of the programme. They found it reassuring that others like them have had to overcome the odds and made it to leadership positions and if they had done it and were available to guide and mentor them, then it would not be an impossible task. It gave them a lot of encouragement and gave a boost to their confidence.

Case study: KPMG – People development

Context – Data and insight

In 2014, KPMG published its diversity target zones to encourage better representation for gender, disability, sexual orientation and ethnicity across the firm and at senior levels. We continue to recognise the commercial, creative and cultural benefits brought about by an inclusive environment and a more diverse workforce.

Within the BAME population, KPMG identified that particular attention needed to be paid to the representation of Black and Mixed colleagues. Our employee data around ethnicity is robust at approximately 94% declaration. We found patterns of difference around the career experiences of Black and Mixed vs. Asian and White colleagues. In publishing its diversity target zone for ethnicity KPMG set a clear focus on increasing our Black and Mixed ethnic diversity at senior levels.

The results of KPMG’s biannual employee survey showed encouraging trends that engagement across all staff groups had improved in comparison with the previous reporting year. BAME employees showed the same or slightly better engagement scores when compared to their White counterparts across a number of indicators – including overall satisfaction with KPMG as an employer, wellbeing, learning and development, and communication.

Specific analysis of the qualitative feedback revealed one clear opportunity for improvement – to enhance career development in a way that impacted on the overall sense of engagement and feeling valued. KPMG co-sponsored the Business in the Community report Race at Work – the largest ever survey on race and employment in the UK – to advance our thinking. Race at Work showed that career achievement was a clear priority for Black employees across the UK.

What KPMG is doing – Developing people

KPMG recognised the value of people development as a way to address both the immediate challenges around engagement and longer-term pipeline aspects of building a diverse workforce. We are building and expanding on our mentoring programmes within a broader set of development activities aimed at linking employee experience, career progress and our target zones for Black and Mixed staff.

KPMG’s diverse talent development programme, GROW, is targeted at manager-to-director grades from our target zone groups (women, LGBT, disabled, and Black and Mixed colleagues). It is designed to deliver stretching personal and professional development to help colleagues embrace their authentic leadership style, with a strong emphasis on mentoring. Participants will be connected with sponsors as part of their transition out of the programme. Mentoring takes the form of peer-to-peer relationships within the programme with the expectation of transferring learning to, and encouraging career conversations with, diverse mentees as an inclusive leadership outcome.

The GROW programme is sponsored by Melanie Richards, Vice-Chairman of KPMG and will see 2 more cohorts commencing during FY17 – bringing the total to 96 participants. At this point in the programme we are making changes to the nomination process to reach a greater proportion of Black and Mixed colleagues.

KPMG is spreading the value of peer mentoring through its African and Caribbean Network (ACN). KPMG has recently completed a cross-organisation peer mentoring partnership for BAME network colleagues with the Department for Transport. This model of mentoring benefits from deeper enquiry, greater challenge from an outside perspective and the exchange of different ‘career content’, including networks, development strategies and resources. The feedback from this programme showed the clear value of the programme to delegates. We are scoping out the second phase of the mentoring partnership with Department for Transport which will extend the Programme to a mixed cohort.

Vitally, these efforts to improve diverse talent development have led to bottom-up change stemming from our ACN. The ACN chair participated on GROW in 2015 to 2016 and is collaborating with KPMG’s Diversity and Inclusion team to lead a programme of activity across attraction, retention, people management and development. Starting with focus groups in July 2016, the ACN secured sponsorship from the Managing Partner and UK People Director to improve the career experiences and outcomes of Black and Mixed staff. Thishas already incuded shifts around our approach to Black and Mixed graduate attraction and agreement to embed reciprocal mentoring with senior partners.

Whilst it is too early to share outcomes from this corporate plan, KPMG is clearly committed to leading on this agenda and we are optimistic that these changes will shift the experiences and outcomes for Black and Mixed colleagues and encourage progress beyond our firm.

Case study: Herbert Smith Freehills – Good practice for publishing statistics

We carry out an annual audit across all diversity strands to monitor our demographics and inclusion indicators. This is done anonymously, which encourages participation and disclosure. The audit is fully supported by senior management. We publish our statistics and the results inform the development of our diversity and inclusion programmes. We have a multiculturalism network which also fully supports the audit. When monitoring, it is important to give people confidence in the purpose of collecting the data, how it will be stored and used and by whom.

From 2012 to 2015, representation of BAME in the firm has increased from 14% to 17%. We have had a particular focus on graduate recruitment (GR) and increasing BAME representation in our Trainee Lawyer population as the basis for building a more diverse talent pipeline. BAME trainees have increased from 18% to 32% as a result of this focus (working with Rare recruitment which specialises in top BAME graduates, hosting GR panel events on multiculturalism, and providing unconscious bias training to GR recruitment partners).

Case study: Arts Council England (via Citizen Space) – Programmes to increase ethnic diversity in specific industries

Critical Mass programme

The Critical Mass programme at the Royal Court Theatre is aimed at emerging or developing BAME playwrights and creates structured opportunities in creative writing and skills development, along with showcasing their work and linking them with relevant sector agencies and organisations. Previous participants have gone on to have their work performed by professional actors.

Inspire programme

The Inspire programme, part funded by Arts Council England was aimed at attracting more BAME curators in museums and galleries. It gave the opportunity for BAME people with some experience in the cultural sector to undertake 2-year work placement opportunities. A number of participants have progressed to Curators.

Change Makers fund

Arts Council England is in the process of delivering the Change Makers fund to increase the diversity of senior leadership in the arts and culture sector. A cohort of BME and disabled potential leaders will undertake a training and leadership programme, hosted by a lead organisation and designed to develop the leadership skills and experience of BME and disabled potential leaders. This programme should assist potential BME leaders in progressing to leadership roles in the sector.

Case study: Taylor Bennett Foundation (TBF) – Industry-specific training courses

The Taylor Bennett Foundation is a registered charity seeking to address the need for greater diversity in PR by finding and preparing talented university graduates from ethnically diverse backgrounds for careers in the communications industry.

The PR industry struggles to attract and recruit young people from ethnically diverse backgrounds. According to the 2013 PRCA and PR Week Census only 8% of PR practitioners are non-White. The Foundation is a model for how other industries can engage with the imperative of diversity and the challenge of recruitment.

The Foundation provides 10-week intensive training courses delivered in partnership with top tier PR agencies and businesses. Trainees are paid a training allowance (the equivalent of the minimum wage) plus travel expenses. As of September 2016, 167 trainees have gone through the programme since launch in 2008.

Over 400 graduates have had the opportunity to attend a full day’s assessment by experienced head-hunters and PR professionals and receive personal feedback on their performance, regardless of their success in securing a place on the programme.

Over 100 organisations have contributed their time or financial support to the programme, typically on a repeat basis. In 2016 the Foundation also launched a 6-month mentoring scheme for BME graduates, partnering them with PR industry mentors and aim to have 100 mentorships completed by December 2017.

Today, alumni of the TBF programme are working in high calibre companies and PR agencies, including: ACCA, Battenhall, the BBC, Brunswick, Deloitte, DiversityInCare, Edelman, Finsbury, FleishmanHillard, FTI Consulting, Golin, Health Education England, ITV, Ketchum, L’Oreal, MHP, Porter Novelli, Tata Group, The Red Consultancy, Thomson Reuters, and Vodafone.

- 75% of alumni are working in PR and 93% are in confirmed employment (whether in PR or elsewhere)

- 76% have had a rise in salary in the last year. The average alumni salary is £26,000 calculated across the range of alumni with between one and 7 years of experience since completing the programme; according to the graduate jobs and information site, Prospects, a typical graduate starting salary in PR is £18,000 to £20,000

- 59% of alumni have taken a new role in the last year, and a marked pay increase can be seen according to years of experience

Case study: PwC – Inclusion and supporting talent

Motivation:

At PwC we are committed to creating an inclusive culture where everyone can reach their full potential, value difference and be themselves at work. For us diverse teams are a business advantage and we want to reflect our clients and the wider world. We have monitored the diversity of our pipelines since 2011 but recognised that if we really want to move the dial on diversity we needed to make some systemic changes to how we attract, retain and promote our people. This also had to cover all aspects of difference, not just gender and, through monitoring our pipelines, we concluded that we needed to work harder at attracting, advancing and retaining ethnic minority talent.

Actions we are taking:

Recruitment

In 2009 BAME students made up only 23% of our overall student intake. So we set ourselves a target for 30% of our student hires to be BAME. We aimed to reach our target in a number of ways:

- Removed UCAS scores as entry criteria for our graduate roles. In May 2015 we were the first large employer to remove UCAS scores as entry criteria for the majority of our graduate roles as a way to broaden access to our profession and make sure we were assessing people on their potential and not their backgrounds.

- Extended the schools and our Back to Schools programme. We combined our schools recruitment and community affairs team to ensure a coordinated approach to our schools outreach programme. We recognised that we needed to target a wider range of schools to raise aspiration about different career options to a more diverse student group and reach a greater number of students.

- Extended the universities we engage with. We’ve also increased the number of UK universities we have a relationship with and now recruit from over 90 universities.

Engagement

The PwC Diversity Career Mentoring programme. We know that a lack of, and access to, role models is a barrier to BAME employees’ career progression so we decided to use our own people to inspire the next generation and provide more visible role models. The PwC Diversity Career Mentoring programme was set up in 2013 to provide university students from diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds with mentors from within the PwC business. The mentors provide students with insight on life at PwC as well as sharing tips and advice on cv writing, job application skills, the firm’s recruitment channels and general guidance on employability skills required for working life.

Sponsorship programme for high potential BAME directors. We know that BAME staff are less likely to have career sponsors, which can impact their allocation to jobs, the roles they have and their career progression. To address this, we started an active sponsorship programme for high potential BAME and female directors and senior managers, called Talent Watch, to ensure that all high potential people are actively sponsored on their career and can address any barriers.

Measurement

We have set ethnicity and gender targets for manager level and above, which provide direction and drive the promotion, recruitment and retention activities that underpin them. This year we have published our targets, and progress against them, in our digital annual report. We believe that greater transparency drives accountability and targets action where it is needed most. Business leaders are also accountable for these targets and for driving change where it is needed.

Our results:

These interventions are producing measurable results, but we recognise that we need to keep up the focus and attention on this important area of diversity to make a sustainable difference.

Recruitment

Our combined efforts are starting to change the profile of our student intake. Since removing UCAS scores we have hired graduates from broader social backgrounds than ever before. In our 2015 student intake of over 1,600, 36% were first generation graduates, 72% attended state school, 11% came from homes eligible for income support and 8% were eligible for school meals. We track the social mobility of our graduate in-take and report it in our digital annual report.

In our 2016 graduate intake, 39% of our joiners are BAME, compared to 21.4% of the UK graduate population. We have also recruited more graduates from non-Russell Group universities. 69% of 2016 graduate intake are from Russell Group Universities, down from 73% in 2014.

Engagement

To date, 70 PwC staff have volunteered to be mentors to our Diversity Mentoring programme and 144 mentees have completed the programme. 6 mentees have gone on to successfully join PwC, working across a range of client facing areas. Others have gone on to pursue professional careers elsewhere. The programme has been so successful that it is now being extended to our regional offices to provide mentors to more people.

b. Literature review

This literature review summarises the key academic evidence and analysis on the progression of BME individuals in the UK labour market. It covers the population of ethnic groups in the UK, the picture for BME groups in the labour market, the pipeline of BME talent from education, the business case for change, the barriers to progression in work experienced by BME individuals and the evidence available on what works.

Ethnic groups in the UK population

14% of the UK population identify as BME[footnote 20]. This is increasing, with the proportion expected to increase to 21% by 2051[footnote 21].

We use Office for National Statistics (ONS) groups to define ethnicity. According to these definitions, and using the latest 2011 Census data, White is the ethnic group with which the majority of people identify – 48.2 million people (86.0% of the population). Within this group, the largest proportion of people identify themselves as being White British – 45.1 million (80.5%), followed by Any Other White – 2.5 million (4.4%). The next largest ethnic group with which people identify is Indian – 1.4 million people (2.5%), followed by Pakistani – 1.1 million (2.0%)[footnote 22]. The level of ethnic diversity in the UK continues to increase over time. All non-White groups in the UK have been growing since 2001[footnote 23]. Projections by the University of Leeds predict large differences in the growth of ethnic minority groups to 2051, with the White British group growing by 4% but the BME share of the population expected to increase to 21%[footnote 24].

What is the picture for Black and Minority Ethnic groups in the UK labour market?

Evidence shows that there is a persistent though decreasing employment gap between BME groups and the White population. The difference between the BME and White employment rates was 12.8 percentage points in 2015[footnote 25]. BME individuals in work tend to be overrepresented in lower paid occupations and sectors, and are underrepresented in higher paid occupations (such as professional and managerial roles)[footnote 26],[footnote 27].

Extensive research now exists pointing to the presence of ethnic inequalities in employment, which have persisted over time. Not only are there disparities in the proportions of people from BME groups getting into work compared with White people (with the consequence that BME individuals are more likely to be unemployed – see next section), but the evidence also points to:

- inequalities in types of occupation, indicating that BME individuals are less able to secure career opportunities aligned to their skills and qualifications

- inequalities in contract types and degrees of job security

- wage differentials and an overrepresentation of BME individuals in low paid jobs

- differences in working hours and in levels of self-employment

- barriers to progression up the career ladder for some ethnic minority groups

Compounding the challenge of identifying and tackling the issues of labour market entry and progression inequalities for BME individuals is the variance in the scale and nature of the problems by ethnic group, gender, region, age, class and migrant status (including whether someone is a first, second or third generation migrant). In addition, it is obvious that BME individuals are not just one group and labour market inequalities vary by ethnic group.

The combination of the factors identified above that determine labour market outcomes makes capturing the whole picture of the challenge very difficult. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the issues facing BME individuals in the labour market in some detail, to account for the wide discrepancies across the BME population.

The employment and unemployment gap

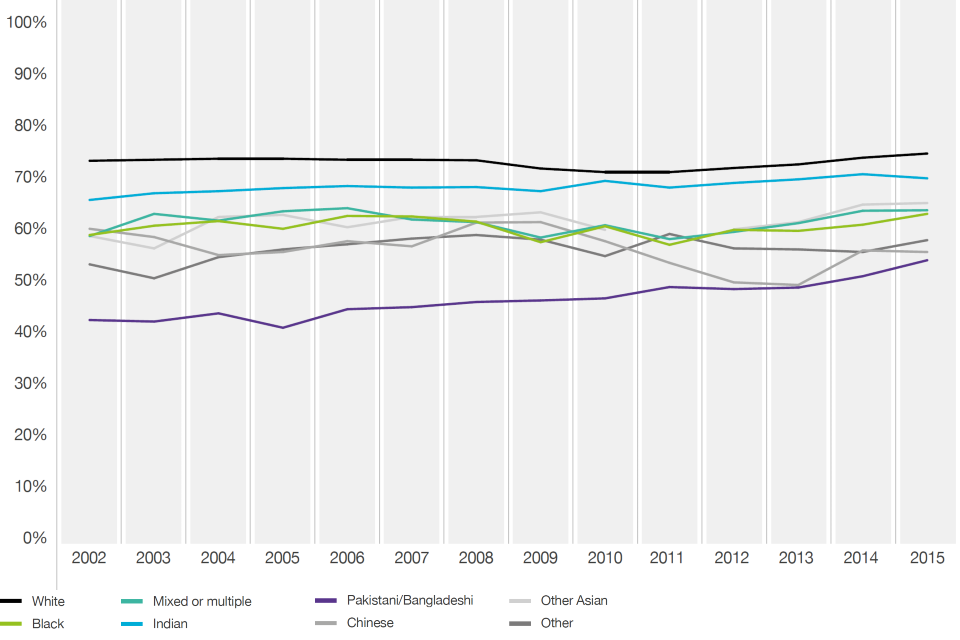

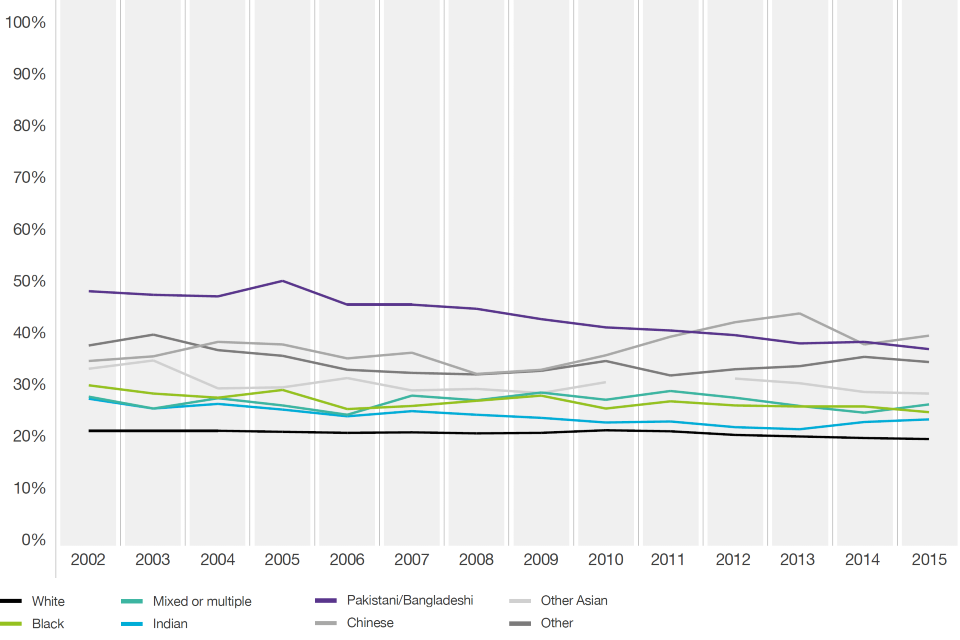

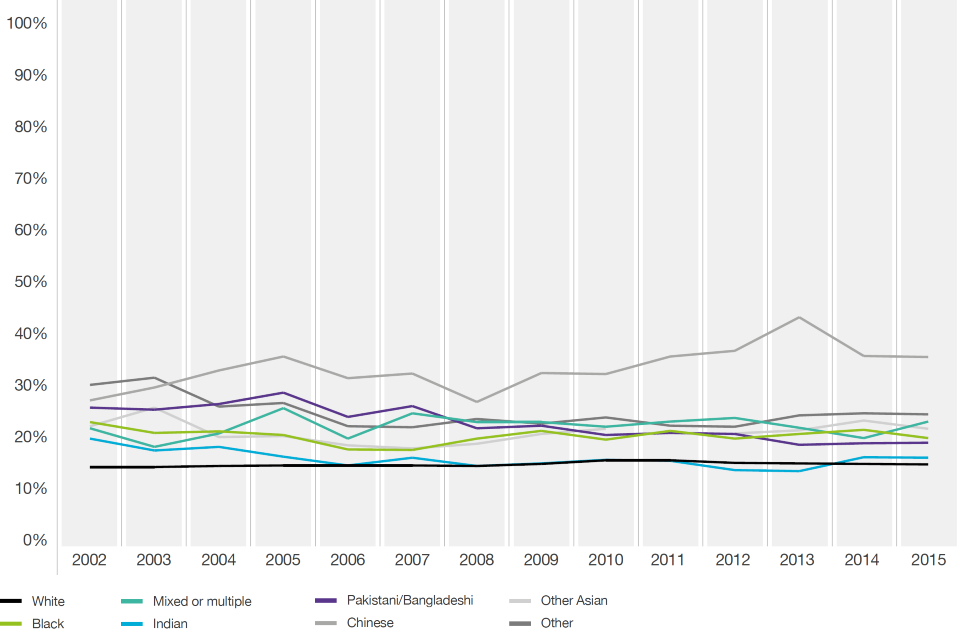

Graph 1: Employment rate by ethnic group, Great Britain, 2002 to 2015. Source: DWP, 2016[footnote 28]

""

| Employment rate by ethnic group | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 74.2% | 74.4% | 74.6% | 74.6% | 74.4% | 74.4% | 74.3% | 72.7% | 72.0% | 72.0% | 72.8% | 73.5% | 74.8% | 75.6% |

| Black | 59.8% | 61.6% | 62.5% | 61.0% | 63.5% | 63.4% | 62.4% | 58.4% | 61.5% | 57.9% | 60.8% | 60.6% | 61.8% | 63.9% |

| Mixed or multiple | 59.6% | 63.9% | 62.6% | 64.4% | 65.0% | 62.8% | 62.3% | 59.3% | 61.7% | 59.0% | 60.4% | 62.1% | 64.5% | 64.6% |

| Indian | 66.6% | 67.9% | 68.3% | 68.9% | 69.3% | 69.0% | 69.1% | 68.3% | 70.3% | 69.0% | 69.9% | 70.6% | 71.6% | 70.8% |

| Pakistani/Bangladeshi | 43.3% | 43.0% | 44.6% | 41.8% | 45.4% | 45.8% | 46.8% | 47.1% | 47.5% | 49.7% | 49.3% | 49.6% | 51.8% | 54.9% |

| Chinese | 61.0% | 59.4% | 55.9% | 56.5% | 58.6% | 57.6% | 62.2% | 62.3% | 58.6% | 54.4% | 50.6% | 50.1% | 56.8% | 56.5% |

| Other Asian | 59.6% | 57.2% | 63.3% | 63.7% | 61.3% | 63.3% | 63.3% | 64.2% | 60.8% | - | 60.9% | 62.3% | 65.7% | 66.0% |

| Other | 54.1% | 51.4% | 55.5% | 57.0% | 58.0% | 59.1% | 59.8% | 58.9% | 55.7% | 60.0% | 57.2% | 57.0% | 56.5% | 58.8% |

Data from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) on the unemployment rate of individuals by ethnic group illustrates not only that BME individuals are more likely to be unemployed, but that the problem has persisted over time and varies significantly by ethnic minority group[footnote 29]. Graph 1 indicates that the employment rate of the White group has continuously been higher than that of any ethnic minority group[footnote 30]. The gap between the BME and White employment rates was 12.8 percentage points in 2015, down from 16.6 percentage points in 2002. Among ethnic groups, Indian individuals tend to have the highest employment rates. In contrast, employment among the Pakistani and Bangladeshi group has been persistently much lower than among all other groups, despite an upward trend in the last 10 years.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s (JRF) research suggests that changes in employment patterns over time could be described as positive for the Indian, and to some extent Chinese, ethnic groups[footnote 31]. However, their key message was still one of enduring ethnic minority disadvantage compared with the White British group. Their further research suggests that existing labour market inequalities are likely to persist in the medium term[footnote 32].

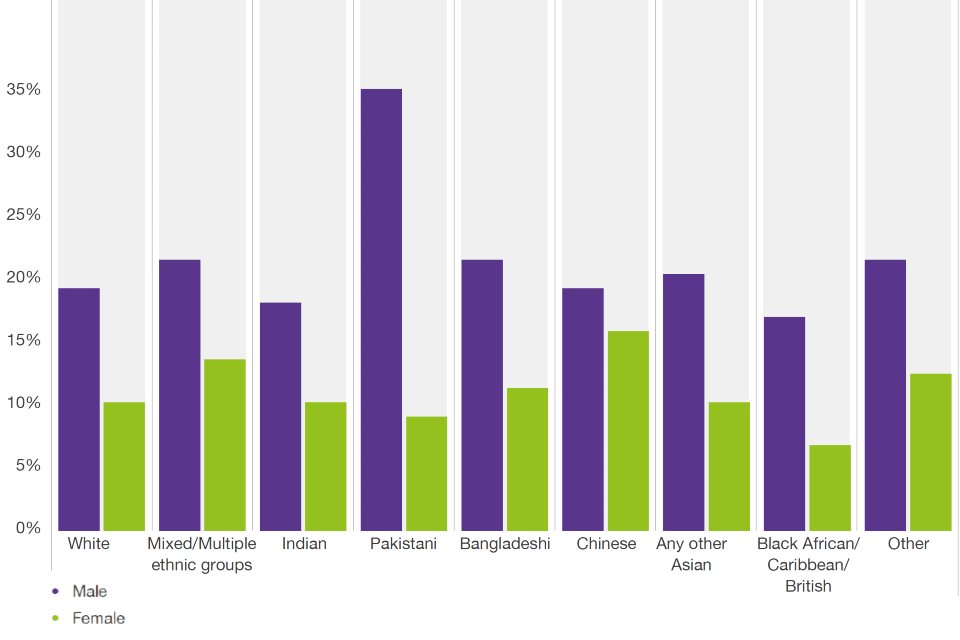

The overall employment rate masks a number of variances within ethnic minority groups by gender and levels of participation. Examples of the key underlying variances include:

- Minority groups are disproportionately affected by youth unemployment, with the unemployment rate of the young Black group (30.3%) more than double that of the young White group (13.3%)[footnote 33]

- There are high rates of unemployment amongst Pakistani/ Bangladeshi women, despite falling in recent years from over 24.0% in 2012 to 15.0% in 2015. It is still significantly higher than the White female unemployment rate of 4.6%[footnote 34]

- Despite falling over the last decade from 51.1% in 2005 to 37.9% in 2015, high levels of economic inactivity remain amongst Pakistani/Bangladeshi groups. Female rates of inactivity are significantly higher than the male rates at 57.2% in 2015[footnote 35]

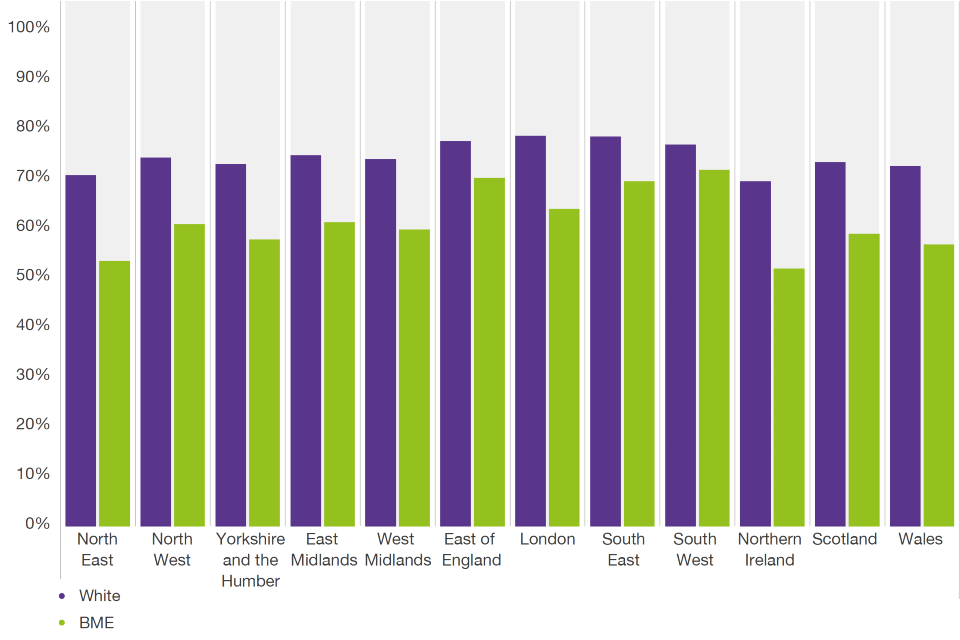

- Employment gaps persist across all regions in the UK, but are particularly high in the North East, Yorkshire and the Humber, Northern Ireland and Wales[footnote 36]

- Research has found that labour force exit and entry probabilities do not differ between Indian, Caribbean and White women. However, Pakistani and Bangladeshi women are less likely to enter and more likely to exit the labour market. In contrast, Black African women have comparatively high re-entry rates[footnote 37];

- Self-employment is an important form of employment for BME men, particularly the Pakistani group, with over 30% of Pakistani men in employment being self-employed. The self-employed are mainly concentrated in sectors such as retail, restaurants and taxi-driving. Self-employment rates are lower for the Chinese and Indian groups. Among women, self-employment rates are significantly lower than the male self-employment rates for all ethnic groups[footnote 38]

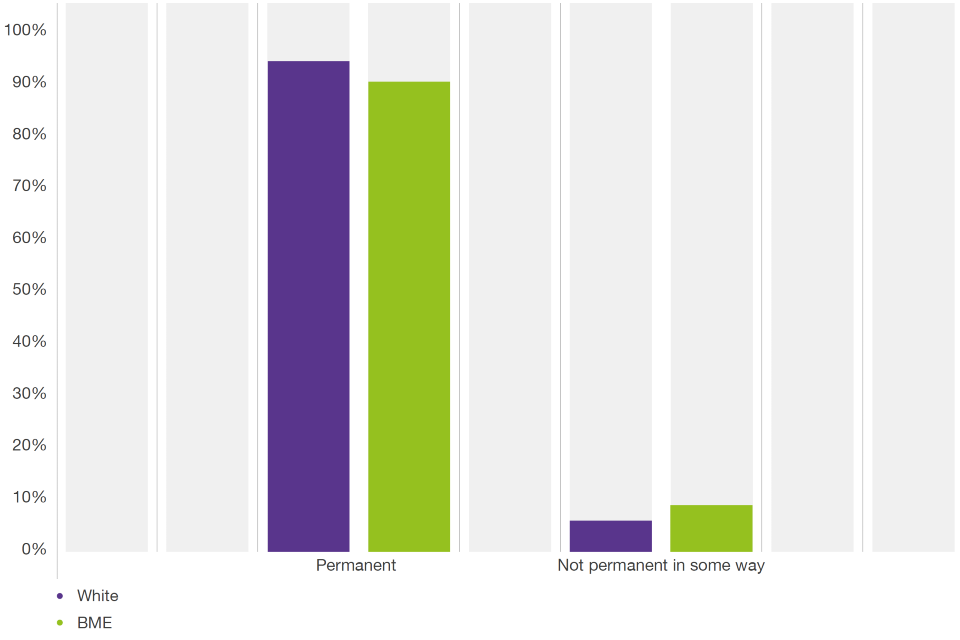

Overrepresentation in lower paid and lower skilled jobs

JRF reports that a higher proportion of BME individuals tend to work in low paying occupations, including sales, catering, elementary personal services, hairdressing, textiles and clothing[footnote 39]. Conversely, they are often underrepresented in higher paid jobs such as building, metalworking and chemical operatives, printing, plant and machine operatives, security and protective services, and in industries where ethnic minorities thrive, such as clerical, secretarial work, cashiers, some communications work, buyers and brokers’ agents[footnote 40]. JRF reports that within occupations there is relatively little inequality between BME and White British people, but nonetheless BME employees are more likely to be the lowest paid within their job type and in the lowest paid types of job. In addition, ethnic minority workers (9%) are more likely to work in temporary employment than White workers (5.5%)[footnote 41].

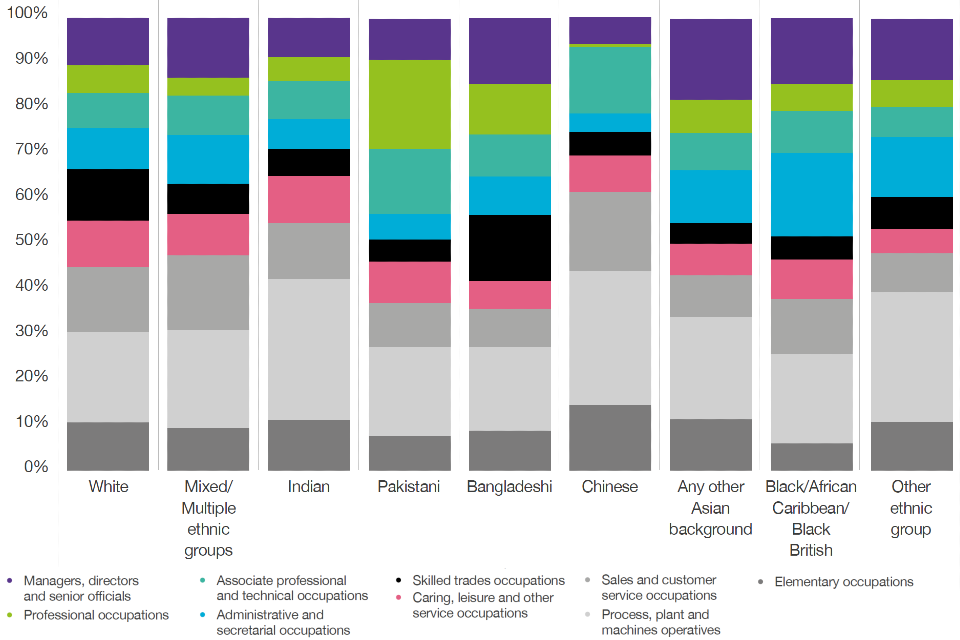

Graph 2: Proportion of individuals in each occupation group, by ethnic group, Quarter 1 2016. Source: ONS Labour Force Survey, 2016[footnote 42]

""

| Proportion of individuals in each occupation group | White | Mixed or multiple | Indian | Pakistani | Bangladeshi | Chinese | Other Asian | Black | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managers, Directors And Senior Officials | 10.5% | 9.3% | 11.1% | 7.6% | 8.7% | 14.3% | 11.2% | 5.8% | 10.6% |

| Professional Occupations | 20.0% | 21.6% | 31.1% | 19.6% | 18.5% | 29.6% | 22.7% | 19.8% | 28.7% |

| Associate Professional And Technical Occupations | 14.4% | 16.6% | 12.4% | 9.7% | 8.5% | 17.6% | 9.1% | 12.2% | 8.6% |

| Administrative And Secretarial Occupations | 10.3% | 9.2% | 10.5% | 9.2% | 6.1% | 8.1% | 7.1% | 8.8% | 5.5% |

| Skilled Trades Occupations | 11.3% | 6.7% | 6.0% | 4.9% | 14.6% | 5.2% | 4.5% | 5.1% | 7.0% |

| Caring, Leisure And Other Service Occupations | 9.2% | 10.7% | 6.5% | 5.7% | 8.5% | 4.1% | 11.7% | 18.4% | 13.3% |

| Sales And Customer Service Occupations | 7.7% | 8.7% | 8.5% | 14.4% | 9.3% | 14.7% | 8.3% | 9.3% | 6.6% |

| Process, Plant And Machine Operatives | 6.1% | 4.0% | 5.3% | 19.7% | 11.1% | 0.7% | 7.3% | 6.0% | 6.0% |

| Elementary Occupations | 10.6% | 13.3% | 8.7% | 9.1% | 14.7% | 5.9% | 18.0% | 14.6% | 13.6% |

A further study by JRF reports that employed BME individuals from some ethnic minority groups are more likely to work in certain occupation types, making the distribution of BME groups unequal across occupational types[footnote 43].

Graph 2 illustrates that whilst some ethnic groups have a high proportion of employed individuals working in managerial and professional occupations, including the Chinese (43%) and Indian (42%) groups, other groups such as the Bangladeshi group(27%) have the lowest proportion of its workforce in these roles. In addition, within highly paid sectors Chinese and Indian groups actually face a larger wage gap than BME individuals in the low paying sectors, which indicates that within these sectors these individuals struggle to reach the most highly paid positions[footnote 44].

Conversely, certain ethnic groups are disproportionately represented in elementary occupations and process, plant and machine operatives, such as the Pakistani (29%) and Bangladeshi (26%) groups, compared with only 17% of the White group working in these occupations. In addition, JRF notes that intermediate skills occupations are generally dominated by particular ethnic groups. For instance, the African group has the largest share in personal service occupations such as hairdressing and beauty, the Bangladeshi and Pakistani group has the largest shares in sales and customer service occupations, and process, plant and machine occupations (for example, textile, plastics and metalworking machine operatives) are most common for the Pakistani group.

Where the occupations dominated by certain BME groups are low-skilled, this could be a sign of difficulty in getting other forms of employment or a stereotyping of BME individuals into particular jobs. Whilst strong representation in managerial and professional roles might be seen as a story of success for some BME groups, JRF points out that managerial roles could also indicate self-employment[footnote 45].

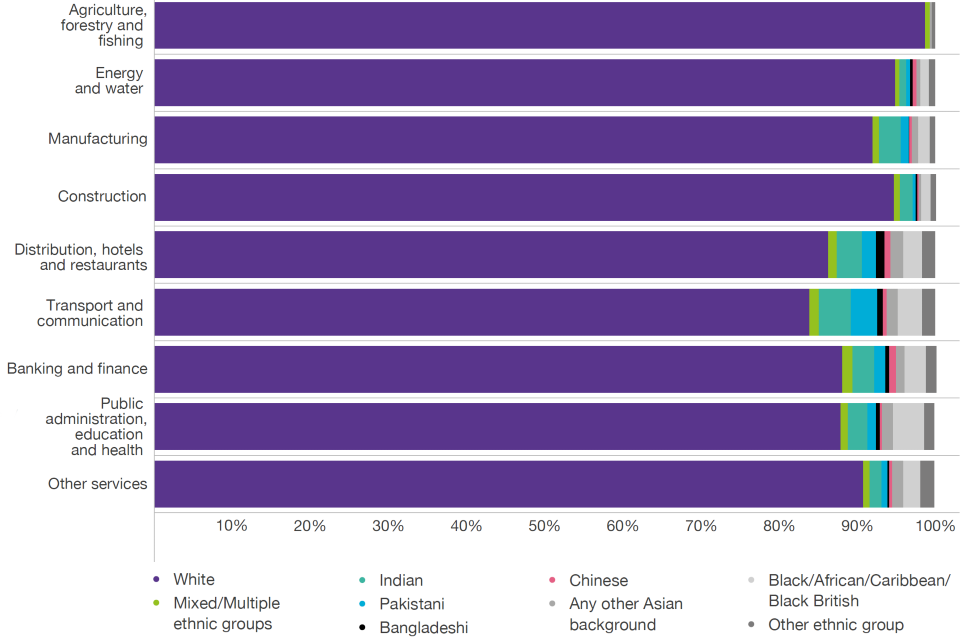

Graph 3: Proportion of individuals in each sector, by ethnic group, Quarter 1 2016. Source: ONS Labour Force Survey, 2016[footnote 46]

""

| Proportion of individuals in each sector | White | Mixed or multiple | Indian | Pakistani | Bangladeshi | Chinese | Other Asian | Black | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 98.7% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.4% |

| Energy and water | 94.9% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 1.1% | 0.8% |

| Manufacturing | 92.0% | 0.8% | 2.8% | 1.0% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 1.5% | 0.7% |

| Construction | 94.7% | 0.8% | 1.6% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 1.2% | 0.7% |

| Distribution, hotels and restaurants | 86.3% | 1.1% | 3.2% | 1.8% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.6% | 2.4% | 1.7% |

| Transport and communication | 83.9% | 1.2% | 4.1% | 3.4% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 1.4% | 3.1% | 1.7% |

| Banking and finance | 88.1% | 1.3% | 2.8% | 1.4% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 1.1% | 2.7% | 1.4% |

| Public admin, education and health | 87.9% | 0.9% | 2.5% | 1.1% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 1.4% | 4.0% | 1.3% |

| Other services | 90.8% | 0.8% | 1.5% | 0.8% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 1.4% | 2.2% | 1.8% |

Similarly, it is interesting to examine how ethnic minorities are distributed across sectors. Graph 3 looks at ethnic group employment by sector. Again, a number of concentrations stand out; for example, some sectors such as transport and communication and distribution, hotels and restaurants exhibit relatively high proportions of BME individuals within their workforce. In contrast, within other sectors, such as agriculture, forestry and fishing; and energy and water, the large majority of employees are White.

Projections by JRF show that the occupational structure of employment is expected to polarise to 2022, with projected increases in high pay and low pay occupations of 2.34 million and 0.52 million respectively, whereas occupations associated with middle-level skills are projected to decrease by 1.01 million[footnote 47]. These forecasts predict Indian and Chinese groups will be concentrated in highly paid occupations, while Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black and other Asian groups will continue to be overrepresented in the low paid to intermediate sector.

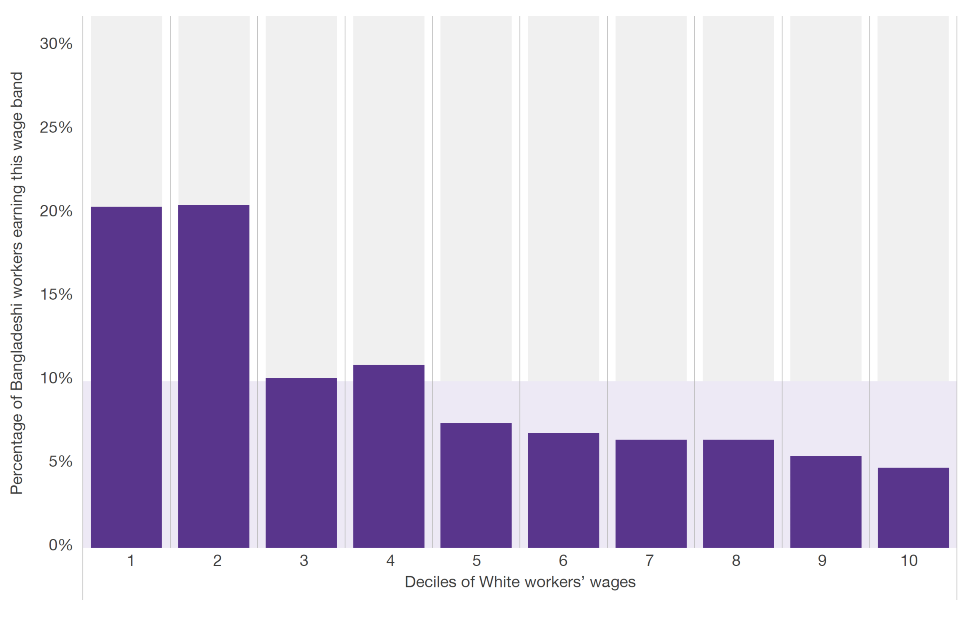

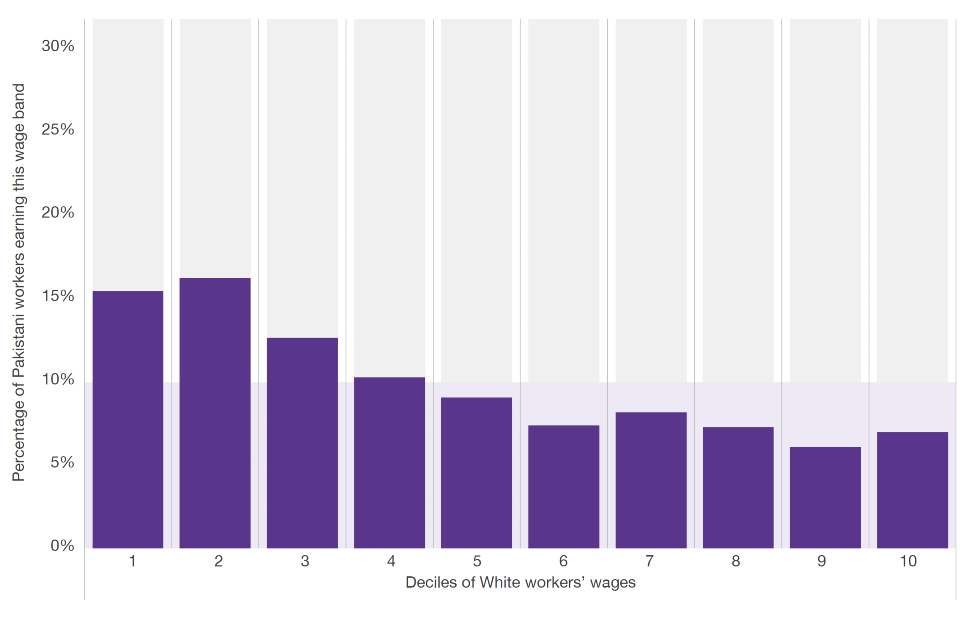

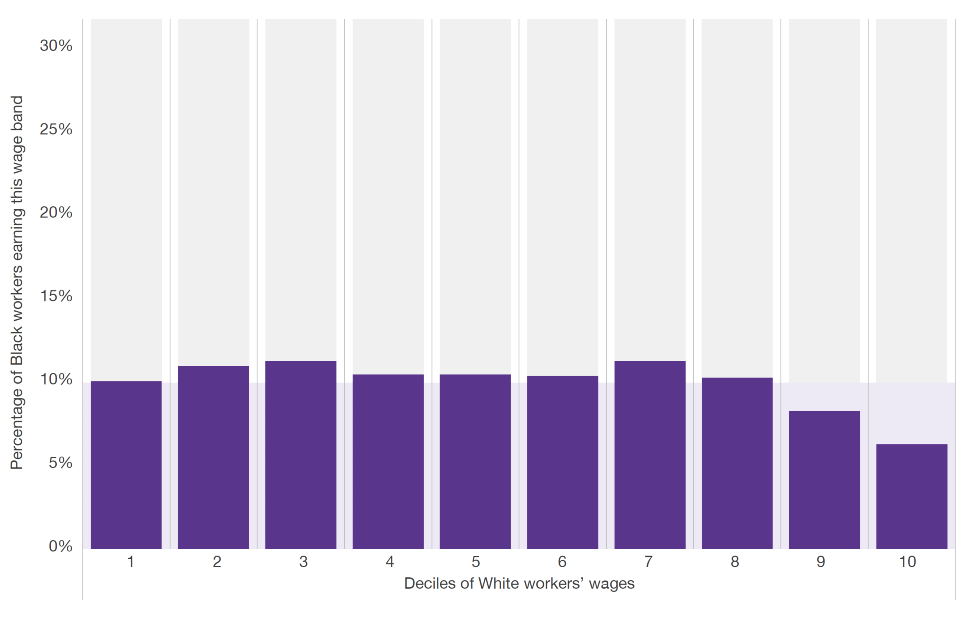

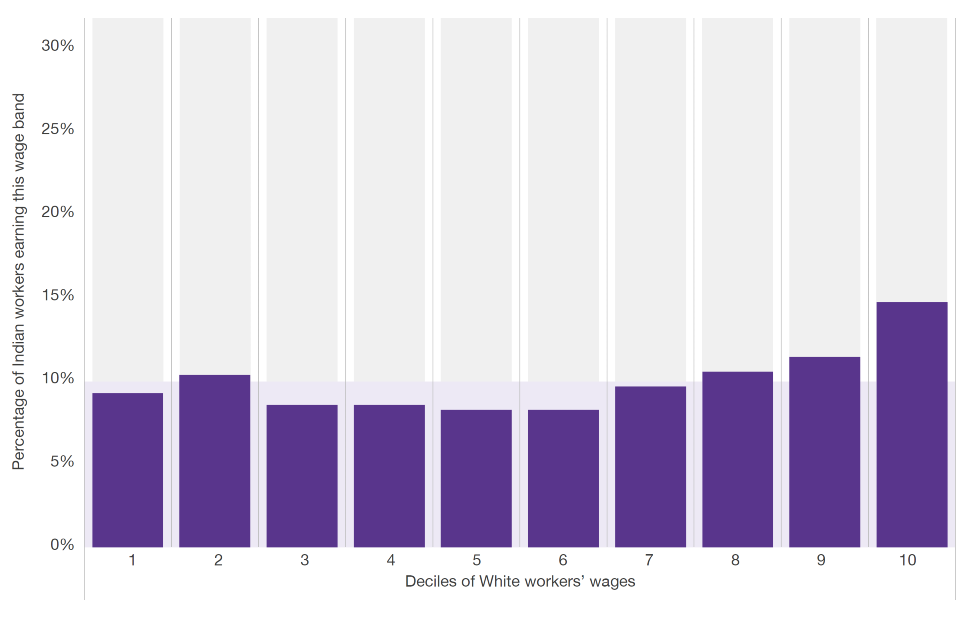

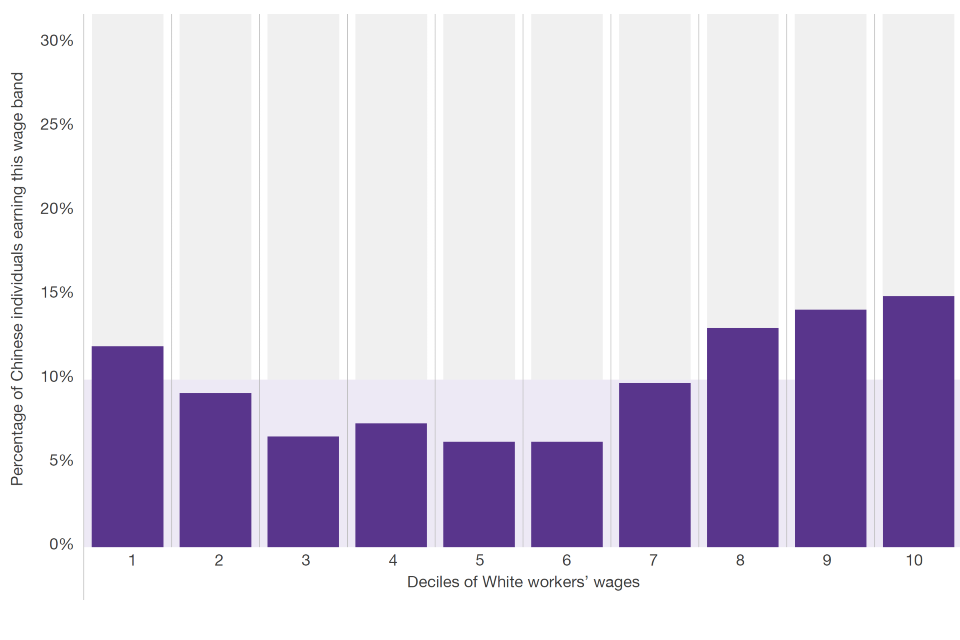

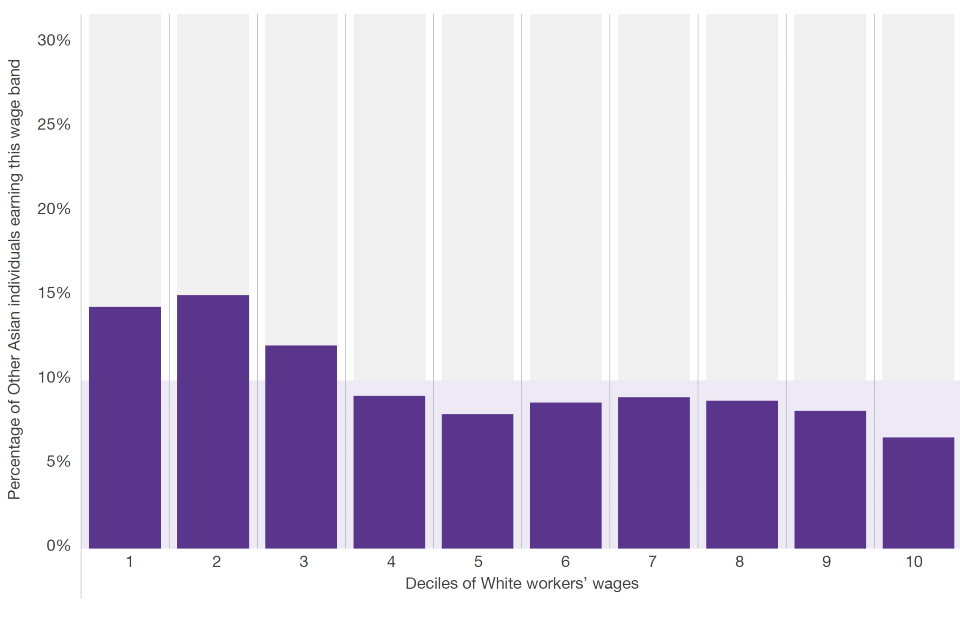

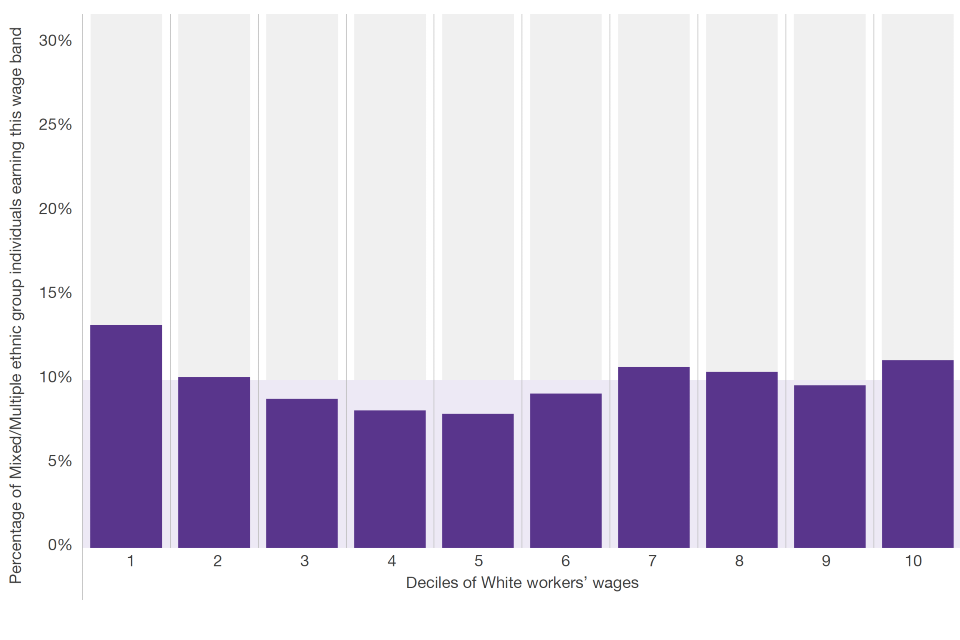

The types of jobs that ethnic minorities find themselves in impacts on wider income inequality. This is particularly stark for some ethnic groups. For instance, between 2011 and 2015, 20% of Bangladeshi individuals in work earned less than the wages of the bottom 10% of White workers. A similar picture is true for workers reporting as being from Pakistani origin, where 16% earn less than the bottom 10% of White workers. However, there have been some success stories. The income distribution for Black/African/Caribbean/Black British workers is almost comparable with that for White workers. Likewise, there are now more Indian workers who are in the top earnings decile (top 10%). Graphs 4 to 7 can be used to compare the wage distribution of BME workers with that of White workers[footnote 48].

Graph 4: Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Bangladeshi individuals, 2011 to 2015. Source: ONS Labour Force Survey, 2011 to 2015[footnote 49]

""

| Deciles of White workers wages | Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Bangladeshi individuals |

|---|---|

| 1 | 20.5% |

| 2 | 20.6% |

| 3 | 10.2% |

| 4 | 11.0% |

| 5 | 7.5% |

| 6 | 6.9% |

| 7 | 6.5% |

| 8 | 6.5% |

| 9 | 5.5% |

| 10 | 4.8% |

Graph 5: Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Pakistani individuals, 2011 to 2015. Source: ONS Labour Force Survey, 2011 to 2015[footnote 50]

""

| Deciles of White workers wages | Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Pakistani individuals |

|---|---|

| 1 | 15.5% |

| 2 | 16.3% |

| 3 | 12.7% |

| 4 | 10.3% |

| 5 | 9.1% |

| 6 | 7.4% |

| 7 | 8.2% |

| 8 | 7.3% |

| 9 | 6.1% |

| 10 | 7.0% |

Graph 6: Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Black/African/ Caribbean/Black British individuals, 2011 to 2015. Source: ONS Labour Force Survey, 2011 to 2015[footnote 51]

""

| Deciles of White workers wages | Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Black individuals |

|---|---|

| 1 | 10.1% |

| 2 | 11.0% |

| 3 | 11.3% |

| 4 | 10.5% |

| 5 | 10.5% |

| 6 | 10.4% |

| 7 | 11.3% |

| 8 | 10.3% |

| 9 | 8.3% |

| 10 | 6.3% |

Graph 7: Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Indian individuals, 2011 to 2015. Source: ONS Labour Force Survey, 2011 to 2015[footnote 52]

""

| Deciles of White workers wages | Wage distribution of hourly earnings for Indian individuals |

|---|---|

| 1 | 9.3% |

| 2 | 10.4% |

| 3 | 8.6% |

| 4 | 8.6% |

| 5 | 8.3% |

| 6 | 8.3% |

| 7 | 9.7% |

| 8 | 10.6% |

| 9 | 11.5% |

| 10 | 14.8% |

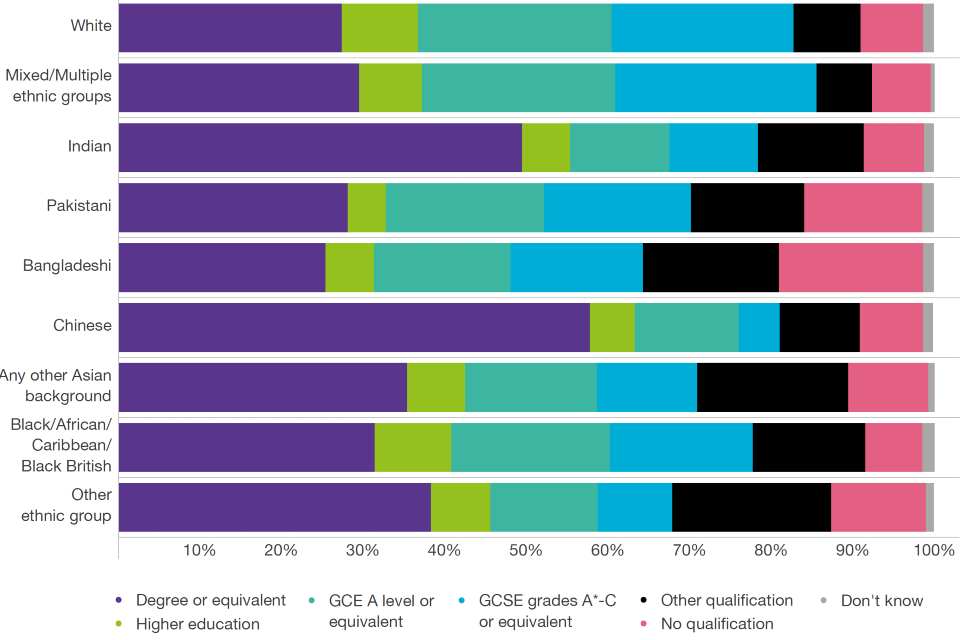

Less able to secure opportunities for employment which matches their skills and abilities

Graph 8: Qualification, by ethnic group, Quarter 1 2016. Source: ONS Labour Force Survey, 2016[footnote 53],[footnote 54]

""

| Qualification by ethnic group | White | Mixed or multiple | Indian | Pakistani | Bangladeshi | Chinese | Other Asian | Black | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree or equivalent | 27.4% | 29.5% | 49.5% | 28.1% | 25.4% | 57.8% | 35.4% | 31.4% | 38.3% |

| Higher education | 9.3% | 7.7% | 5.9% | 4.7% | 5.9% | 5.5% | 7.1% | 9.4% | 7.3% |

| GCE A level or equivalent | 23.8% | 23.7% | 12.2% | 19.4% | 16.8% | 12.8% | 16.2% | 19.5% | 13.2% |

| GCSE grades A*-C or equivalent | 22.3% | 24.7% | 10.8% | 18.0% | 16.2% | 5.0% | 12.3% | 17.5% | 9.1% |

| Other qualification | 8.2% | 6.8% | 13.0% | 13.9% | 16.7% | 9.8% | 18.5% | 13.8% | 19.5% |

| No qualification | 7.7% | 7.2% | 7.4% | 14.5% | 17.7% | 7.8% | 9.8% | 7.0% | 11.6% |

| Don’t know | 1.3% | 0.5% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 0.8% | 1.5% | 1.0% |

Graph 8 illustrates the highest level of qualification of BME individuals in comparison to the White group. It is evident that BME individuals generally have educational outcomes on par with or even superior to the White group. For instance, 37% of BME individuals have obtained a degree or equivalent, as opposed to only 27% of the White group. In particular, individuals in the Chinese (58%) and Indian (50%) groups are more likely to have obtained a degree. In contrast, individuals from the Pakistani (15%) and Bangladeshi (18%) groups are much more likely to have no qualifications.

Despite these positive outcomes, there is a variety of evidence that suggests that BME individuals are more likely to be overqualified for the job that they are in. In many cases this will mean that the skills and abilities of BME individuals are not being fully utilised. JRF finds that, taken as a whole, ethnic minority groups tend to have a slightly higher educational attainment than those from White ethnic groups on average[footnote 55]. The ‘overqualification’ of ethnic minority employees in low paying jobs is widespread, with Pakistanis and Bangladeshis being most likely to be overqualified.

A further JRF study in 2015, which looked at supporting young BME individuals from education into work, found that[footnote 56]:

- all BME groups are more likely to be overqualified than White ethnic groups. The gap is widest for those with A-level qualifications

- over 40% of all Black African employees with A-level and graduate-level qualifications are overqualified for their current jobs

- BME women entering the labour market in recent times, particularly Black African and Pakistani/Bangladeshi women, are taking jobs well below their qualification level

- despite a slightly higher level of educational qualifications amongst BME individuals relative to the White population, BME individuals are less likely to attend Russell Group universities

There is a wealth of evidence suggesting that BME individuals struggle to achieve the same progression opportunities as their counterparts. Research in 2015 by Business in the Community (BITC) found that 1 in 8 of the working age population are from a BME background, yet only 1 in 10 are in the workplace and only 1 in 16 top management positions are held by an ethnic minority person[footnote 57]. As noted above, JRF found that a higher proportion of BME individuals tend to work in low paid occupations[footnote 58]. JRF notes that progression from these low paid, low skilled positions is as challenging for some BME groups as it is getting into employment in the first place.

BITC’s Gender and Race Benchmark looked at trends in performance and appraisal and found that[footnote 59]:

- BME employees are less likely to be rated in the top 2 performance rating categories (27% compared with 35% of White employees)

- BME employees are less likely to be identified as ‘high potential’ (10% compared with 20% of White employees)

- the public sector is less likely to identify BME as ‘high potential’ in similar proportions as White employees

- there is an issue with talent programmes, in that the future leadership pipeline within the private sector is imbalanced when analysed by race

- appraisal mechanisms feeding into leadership are more likely to rate BME employees less favourably;

- white employees are more likely to be promoted overall compared with all other groups

- BME women are more likely to be promoted than BME men (BME women overall promotion rate is 7.3% compared with 6.4% for BME men)

- in terms of opportunities for progression 35% of Pakistani, 33% of Indian and 29% of Black Caribbean employees report feeling that they have been overlooked for promotion[footnote 60]

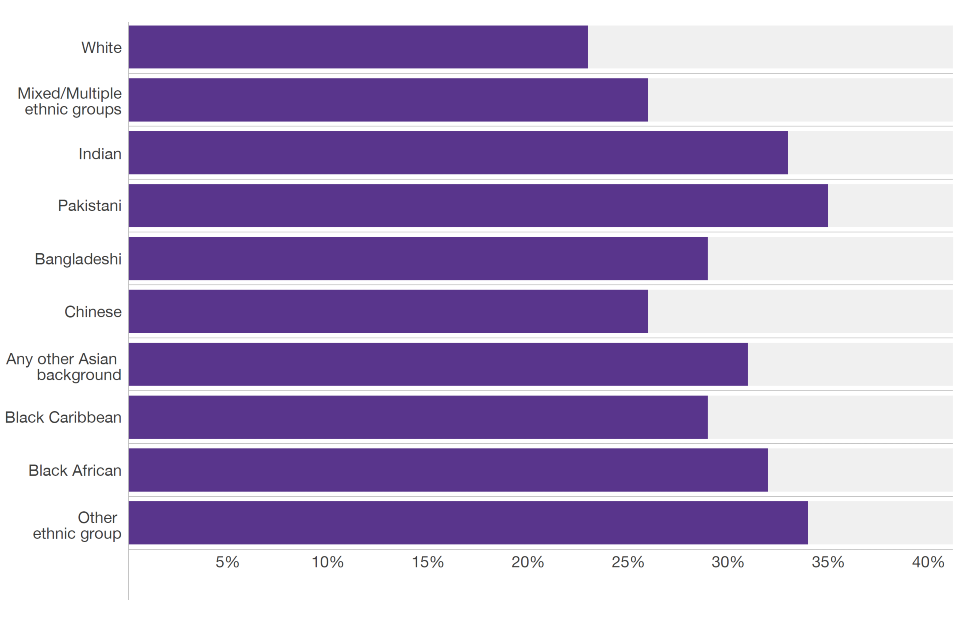

Graph 9: Percentage of employees reporting that they have been overlooked for promotion by ethnic group[footnote 61]. Source: Business in the Community, 2015[footnote 62]

""

| Ethnic group | % of employees reporting that they have been overlooked for promotion |

|---|---|

| White | 23% |

| Chinese | 26% |

| Mixed | 26% |

| Bangladeshi | 29% |

| Black Caribbean | 29% |

| Other Asian | 31% |

| Black African | 32% |

| Indian | 33% |

| Other Asian | 34% |

| Pakistani | 35% |

According to JRF, BME groups also tend to have unequal access to opportunities for development, often because of a lack of clear information on training opportunities or progression routes within their workplaces[footnote 63]. This can be made worse if progression relies on opaque or informal processes, if there is a lack of BME role models or mentors at higher levels within their workplaces to provide support and advice, or if there is a gap between equality and diversity policies and practice in the workplace.

Underrepresentation of BME at the top

In addition to the evidence that BME individuals struggle to achieve the same progression opportunities as their White counterparts, there is evidence that BME individuals are underrepresented at managerial and senior positions in business.

BITC reports that there has been virtually no ethnicity change in top management positions in the 5 years between 2007 and 2012, and, in fact, the gap at management level widened during that period[footnote 64]. Again, it is important that ethnic groups are considered separately, because there are significant differences in success rates and sector representation between ethnic groups. The Black and Black British group did particularly poorly over the period between 2007 and 2012, with the number of Black/Black British people in top management positions decreasing by 42%.

BITC also found that a number of UK sectors appear to be closed off to BME people when it comes to leadership opportunities, with almost three-quarters (74%) of management positions held by BME individuals clustered in 3 sectors: banking and finance; distribution, hotels and restaurants; and public administration, education and health. The banking and finance sector appears to perform better than some other sectors, with the number of managers from all but one ethnic group increasing between 2007 and 2012. The majority of management positions within the energy and water, construction, legal, media and political sectors were held by White people.

The number of BME managers in the ‘other services’ sector has had the second fastest growth rate, of 51%, between 2007 and 2012. ‘Other services’ covers activities of membership organisation, repair of computers and personal household goods, and personal service activities such as dry-cleaning, hairdressing and beauty treatments. BITC suggests that this could indicate a preference by BME individuals to start their own business rather than find employment in the more traditional industries. Whether this is by choice or necessity is an interesting question. On a positive note, BITC reports that 10% of BME employees are on the first rung of the promotion ladder, which is proportionate to the 10% of BME people in employment at the time of the BITC report.

With regard to the public sector, 11% of civil servants in government agencies are BME individuals[footnote 65]. However, at a senior level this number decreases to 7%. 6% of MPs and members of the House of Lords have an ethnic minority background, which means that the 14% of the population who are BME individuals are currently being underrepresented. In the health sector, 18% of NHS staff and 41% of doctors come from an ethnic minority background. However, the General Medical Council reports that White UK medical graduates are more likely than BME graduates to pass specialty exams, and that the chances of passing are particularly low if a primary qualification was gained outside the UK or EEA[footnote 66].

Green Park’s annual survey of Britain’s 10,000 top business leaders, reports that there has been a decline in BME presence in the pipeline Top 100 leaders, which it defines as the most senior leaders including all reports to main board directors[footnote 67]. Its analysis finds that the equivalent of nearly 40 non-White leaders has been lost in the 12 months preceding the survey. On a somewhat positive note, Green Park found that there were 3 non-White Chairs of FTSE 100 companies in spring 2015, up from 2 in 2012.

Research by Third Sector also finds that, amongst leadership of the top 50 UK fundraising charities, just 12% of chief executives, 6% of senior managers and 8% of trustees are non-White[footnote 68]. These proportions fall short relative to the overall proportion of non-White people living in the UK. Furthermore, 19 of the 50 top charities surveyed have no non-White people on their top teams or trustee boards.

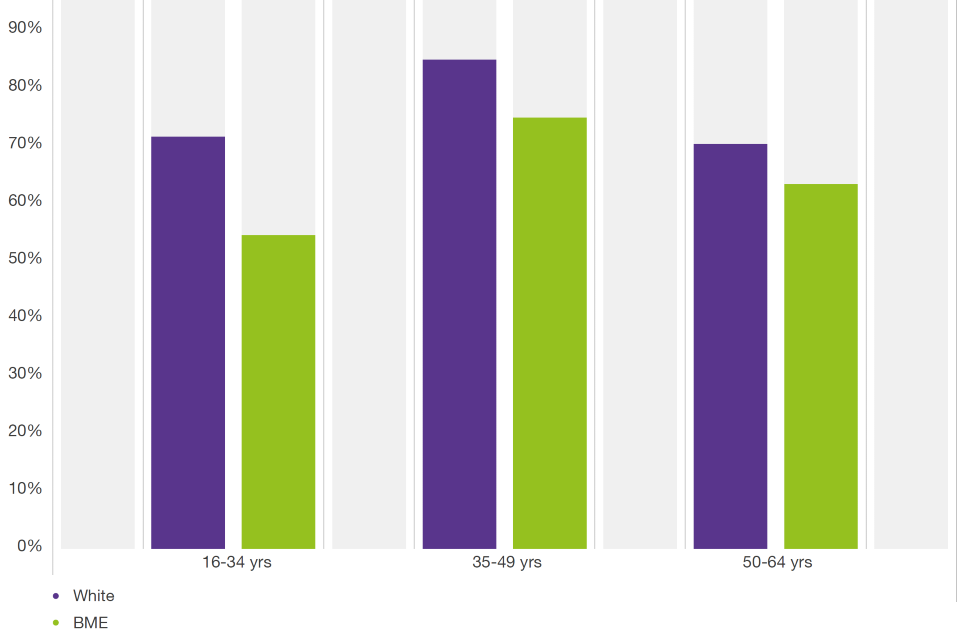

Pipeline of talented and skilled Black and Minority Ethnic individuals

BME individuals are more likely to participate in higher education than White British individuals[footnote 69]. However, evidence indicates that this does not translate into equal outcomes in terms of both degree attainment and employment after graduation[footnote 70],[footnote 71]. Similarly, figures suggest that there remains an employment gap for those with vocational qualifications and for those who have completed apprenticeships[footnote 72].

Higher education

Examining the performance of different ethnicities in the UK’s higher education system is one way to better understand the pipeline of skilled individuals from different ethnic backgrounds who are entering the labour market. There is a very good story to tell on the relative progression of BME groups to higher education in England and the higher representation of BME groups in English higher education institutions relative to their share of the population. However, issues remain around the retention, attainment and progression from higher education for some BME groups.