Nuclear emergencies: information for the public

Updated 25 May 2022

Introduction

The Radiation (Emergency Preparedness and Public Information) Regulations 2019 (REPPIR) aim to establish a framework for the protection of members of the public and workers from and in the event of radiation emergencies that originate from premises.

The regulations ensure that members of the public are provided with information both before and during an emergency, so that they are properly informed and prepared, in advance, about what they need to do in the unlikely event of a radiation emergency occurring.

This booklet is intended to support local authorities in the provision of information to the public by providing background information on radiation and health. It is recommended that the contents of this booklet are read together with other local guidance provided.

Emergency consequences

Nuclear licensed sites are designed, built and operated so that the chance of an emergency and any release is very low. Emergencies have occurred however, notably at Windscale (UK) in 1957, Three Mile Island (US) in 1979, Chernobyl (Ukraine) in 1986 and Fukushima (Japan) in 2011.

Legislation requires operators of nuclear licensed sites to have plans to deal with emergencies.

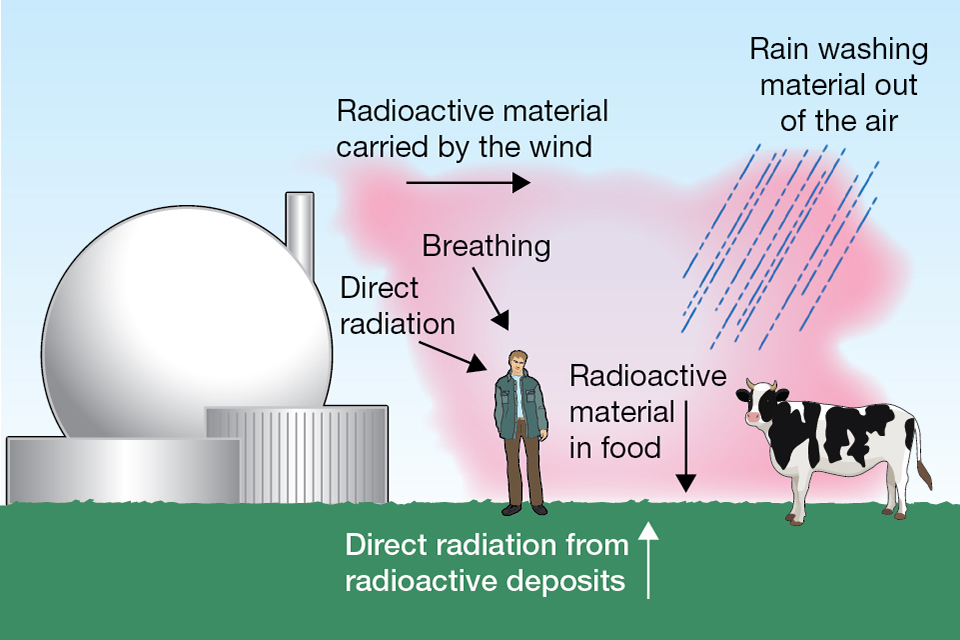

Weather conditions at the time of release are an important factor determining the affected areas as the radioactive material is carried down wind, spreading out and depositing on the ground and other surfaces as it goes.

People may be exposed to radioactivity released during an emergency in the following ways:

- by breathing in radioactive materials (inhalation)

- by direct radiation exposure from radioactive materials carried in the air and deposited on surfaces

- by eating and drinking food and water contaminated with radioactive materials (ingestion)

Radioactive material is carried by the wind. Rain washes material out of the air. Direct radiation comes from radioactive deposits on surfaces. Radioactive materials can also be breathed in or ingested when eating contaminated food.

Protective actions

In the unlikely event of an emergency at a nuclear licensed site which results in a release of radioactive material, the following actions could be taken to reduce radiation doses.

Sheltering

Staying indoors with doors and windows closed. This provides a high degree of protection from breathing in radioactive material in the air. It also gives protection from direct radiation from radioactive material on the ground.

Evacuation

Evacuation reduces exposure by taking people away from the affected area.

Stable iodine tablets

Faults at operating nuclear reactors can release radioactive forms of iodine, which can lead to radiation doses to the thyroid gland. It has been shown that taking stable iodine speeds the removal of radioactive iodine from the body, resulting in a reduced radiation dose.

Food

Radioactive material deposited on soil or grass can find its way into food through crops and animals. It might be necessary to ban milk or other foods containing radioactive material following an emergency.

Food advice compared with other protective actions

Where food is contaminated it can lead to an intake of radioactivity over a longer period of time, leading to a build-up of dose. This dose can be reduced by banning the sale of contaminated food.

The limits on radioactivity in food are deliberately low to reduce radiation dose to minimal levels. This may result in a wide area being subject to food controls.

If you are in doubt about what protective actions to take, follow the instructions provided by the emergency services.

If you live close to a nuclear licensed site, you should refer to the specific local information provided to you.

Emergency plans

To ensure that there is adequate protection against emergencies, legislation requires the operator of a site to conduct a detailed safety assessment of the plant and processes. This assessment assists in identifying circumstances in which an emergency may occur.

Based on the results of the assessment, working procedures may be changed or additional engineering controls introduced to make the possibility of an emergency even more unlikely.

Each site is required to have emergency plans to deal with the on and off-site consequences of such an emergency.

Emergency plans must be sufficiently flexible to deal with any emergency. These plans contain details of arrangements to protect the public.

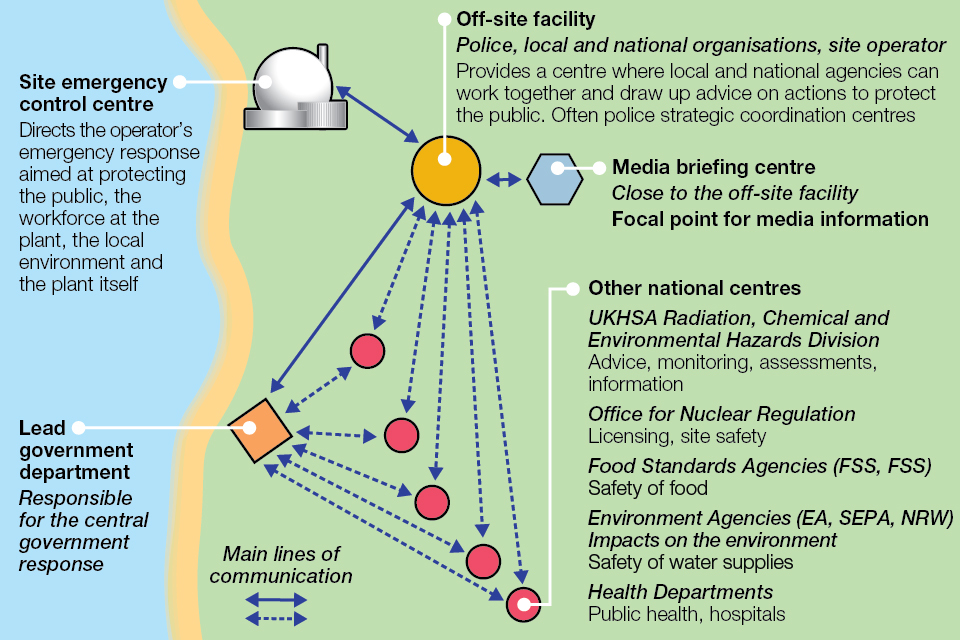

In an emergency, the site emergency control centre directs the operator’s emergency response aimed at protecting the public, the workforce at the plant, the local environment and the plant itself. The local government department is responsible for the central government response.

The off site facility provides a centre where local and national agencies including the police, local and national organisations, the site operator, can work together and draw up advice on actions to protect the public. This is often at a police strategic coordination centre.

The media briefing centre is close to the off-site facility, and is a focal point for media information.

Other national centres include UKHSA Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards Division, who offer advice, monitoring, assessments and information; the office for nuclear regulation who offer advice on licensing and site safety; the food standards agencies who oversee the safety of food; the environment agencies who consider the impacts on the environment, and other health departments including hospitals.

Lines of communication are established and remain open between each of these sites.

Detection and monitoring

Radioactive material in the environment can be measured in various ways. Many organisations can make such measurements: operators of nuclear licensed sites, UKHSA, government departments, local authorities, universities and local medical physics departments.

Following an emergency, a wide range of food supplies and drinking water would be checked to see if they contained more radioactive materials than the allowed levels.

Fixed radiation monitors around nuclear licensed sites would detect and measure abnormal radiation levels. By international agreement the UK should receive warning of nuclear accidents abroad. As a back-up, automatic instruments throughout the country continuously measure for abnormal radiation levels.

Detailed and sensitive measurements of radioactive materials in people can be made to assess doses and to check that protective actions were effective.

Monitoring of the general public in the vicinity of a nuclear licensed site would be conducted to provide reassurance to the public in the event of an emergency. Initial monitoring would be followed-up, if necessary, to assess long-term doses to individuals.