Sexually transmitted Shigella spp. in England: data up to quarter 2, 2022

Updated 16 May 2024

Applies to England

Background

Shigella spp. are bacterial enteric pathogens transmitted through faecal-oral contact, which can cause dysentery. Whilst diagnoses of shigellosis are often associated with exposure to contaminated food or water during travel to endemic countries (1), shigellosis is increasingly acquired domestically in England, mainly among men who have sex with men (MSM) via direct oral-anal contact, oral sex after anal sex or play, including fingering and use of sex toys (2).

The previous Shigella Health Protection Report (3) described a reduction in the number of reported Shigella spp. diagnoses overall in 2020, likely due to the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) related control measures, reduced international travel, limited domestic travel and social distancing. The previous report also described high levels of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among Shigella spp. isolates in England.

This report presents a timely opportunity to review trends in Shigella spp. diagnoses in England, using laboratory surveillance data following the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions in 2021 and 2022, and complements the return of the ‘Maybe It’s Shigella’ awareness campaign from 11 April 2022, hosted by HIV Prevention England with colleagues from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) (4). Throughout this report, we refer to adult men without a recent history of foreign travel as presumptive MSM and use this as a proxy for sexual transmission among MSM (5). Data from 2019 has been used as a baseline comparator for pre-COVID-19.

Main messages

The main messages from this report are that:

- whilst the number of sexually transmitted Shigella spp. diagnoses reported in England by quarter 2 (Q2) 2022 had not yet reached pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels, reported diagnoses among presumptive MSM increased from 67 to 152 between Q3 2021 and Q2 2022 indicating transmission has increased following the lifting of restrictions

- London continued to account for most Shigella spp. diagnoses reported in the 12-month period between Q3 2021 and Q2 2022, followed by Greater Manchester and Surrey and Sussex

- from Q3 2021 onwards, there was a substantial increase in S. sonnei diagnoses from the very low levels reported during the COVID-19 lockdown period, with 56 diagnoses reported in Q2 2022, in addition to increased reporting of S. flexneri diagnoses – this increase was driven by the return in late 2021 of a S. sonnei clade 5 outbreak strain which had since become extensively drug-resistant (XDR) (technical note D) (6)

- antimicrobial resistance among Shigella spp. isolates continues to be a significant public health concern, in particular following the increase in XDR, S. sonnei isolates with acquired resistance to a key second-line treatment for shigellosis, ceftriaxone – ongoing monitoring is required to ensure the appropriate clinical treatment of severe cases of shigellosis and the continued effectiveness of antimicrobial treatment

Overview of Shigella spp. trends

The Second Generation Surveillance System (SGSS) provides the total number of Shigella spp. diagnoses reported in England from diagnostic laboratories (technical note A). Although data in the Gastrointestinal Data Warehouse (GDW) is a subset of diagnoses reported in SGSS, data from GDW is primarily used in this report to allow for more detailed analyses (technical note A).

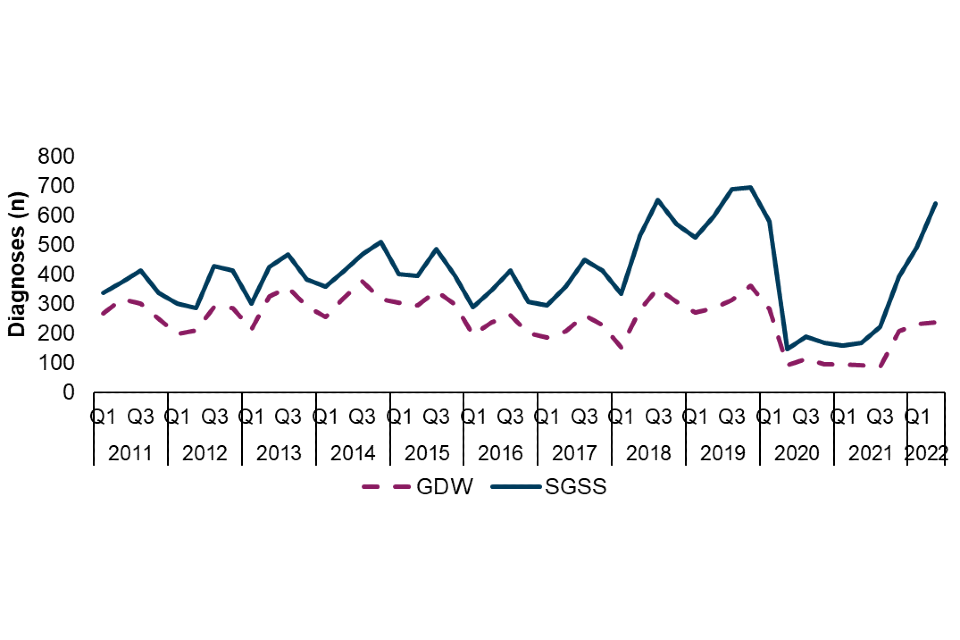

There was a steep decline in early 2020, and subsequent low plateau, of diagnoses reported to both surveillance systems, likely due to COVID-19 related control measures (Figure 1). Since Q3 2021 diagnoses among adults reported to both surveillance systems have increased, and in SGSS diagnoses are nearing levels seen prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (†). Reported diagnoses increased by 189% in SGSS (222 to 642) and 172% (87 to 237) in GDW between Q3 2021 and Q2 2022.

Figure 1. Number of Shigella spp. diagnoses among adults (≥16 years), England, Q1 2011 to Q2 2022, by laboratory surveillance system (†)

† The disparity between the number of diagnoses reported in SGSS and GDW is due to incomplete referral of specimens from local laboratories to the UKHSA Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Laboratory (GBRU). S. flexneri isolates are more likely to be referred to the GBRU than S. sonnei isolates; variation in the prevalence of species across time is therefore expected to lead to changes in the disparity between laboratory data sources across time. Data source: GDW and SGSS (technical note A)

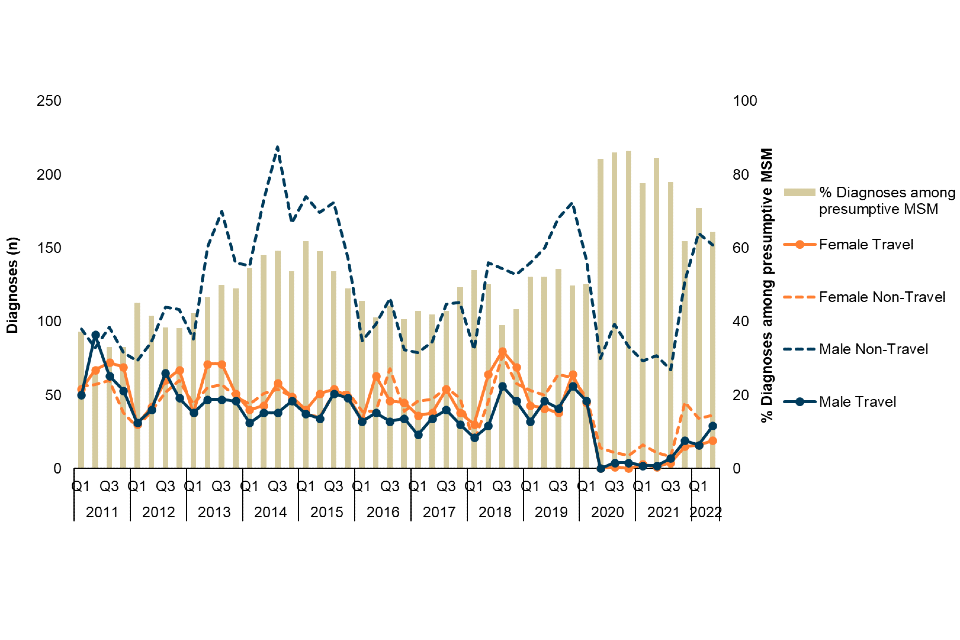

The decline in reported diagnoses in 2020 was largely driven by a decline in travel-associated diagnoses, and whilst diagnoses among presumptive MSM reduced, they continued to be reported throughout 2020 (Figure 2). Following the easing of COVID-19 restrictions from Q2 2021, the number of travel-associated and non-travel associated diagnoses increased in Q3 2021. However, this increase was most notably among presumptive MSM, with a 127% increase (from 67 to 152) between Q3 2021 and Q2 2022 (Figure 2). Due to this substantial increase among presumptive MSM, coupled with the more modest increase in travel-associated cases and cases among females, the proportion of all diagnoses among presumptive MSM is greater in 2022 (to Q2) (68%) compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic (52% in 2019).

Figure 2. Number of Shigella spp. diagnoses among adults (≥16 years) by travel association and sex, and proportion of diagnoses among presumptive MSM (technical note B), England, Q1 2011 to Q2 2022 (‡)

‡ Excludes those where sex is not known. Data Source: GDW (technical note A)

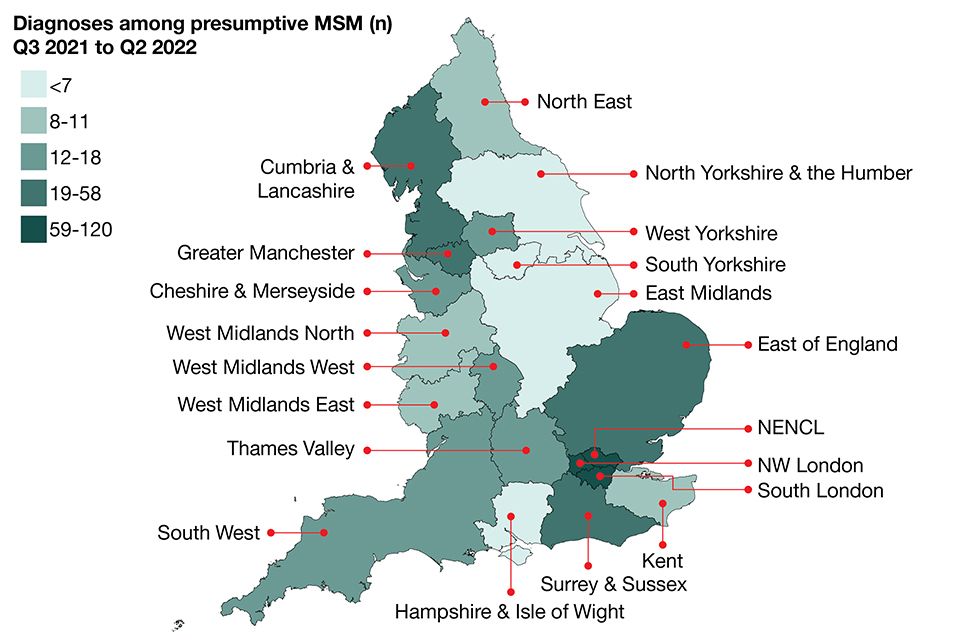

In the 12-month period between Q3 2021 and Q2 2022, London continued to account for the highest proportion of diagnoses among presumptive MSM (technical note B) (312 out of 583), followed by Greater Manchester and Surrey and Sussex Health Protection Teams (HPT), with 58 and 31 diagnoses, respectively (Figure 3) (3).

Figure 3. Number of Shigella spp. diagnoses among presumptive MSM (technical note B) by Health Protection Team, England, Q3 2021 to Q2 2022 (§)

§ Excludes those where HPT is not known. Whilst HPT refers to patient residence, the reporting laboratory is used where patient residence is not known. Data source: GDW (technical note A). NENCL: North East and North Central London HPT. NW London: North West London HPT

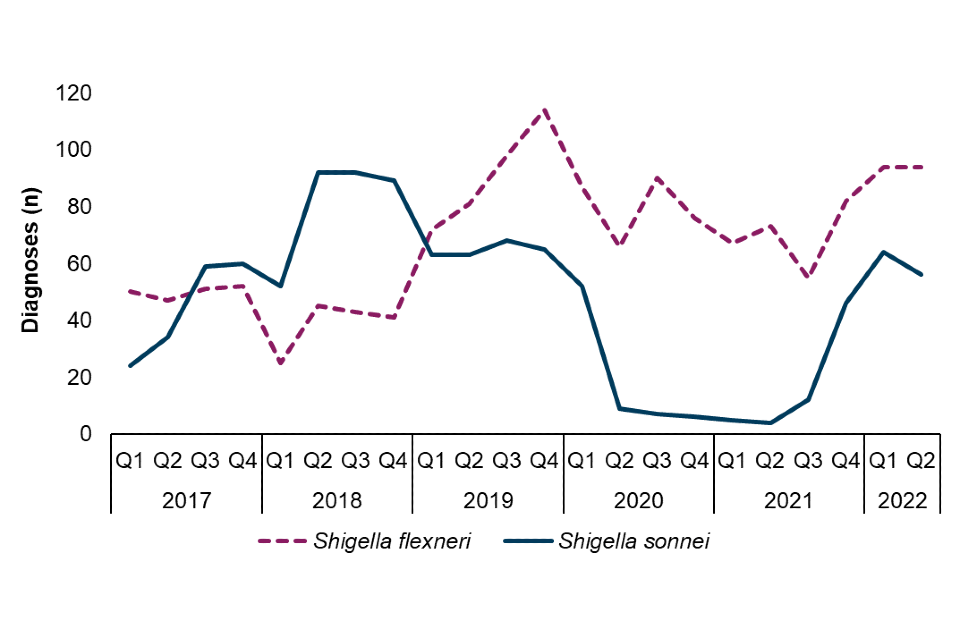

Among presumptive MSM (technical note B), S. flexneri has been the most reported species since 2019. Following very few reported diagnoses of S. sonnei among presumptive MSM during periods of COVID-19 lockdowns, between Q3 2021 and Q2 2022 there was a rapid and substantial increase in diagnoses of 367% (12 to 56). This increase occurred in parallel with a 71% increase in S. flexneri diagnoses (55 to 94) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Number of Shigella spp. diagnoses among presumptive MSM (technical note B) by species, England, Q1 2017 to Q2 2022 (❖)

❖ Data Source: GDW (technical note A)

Antimicrobial resistance among sexually transmitted Shigella spp.

The World Health Organization recommends ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) as a first-line treatment for shigellosis, and azithromycin (a macrolide), ceftriaxone (a third-generation cephalosporin), or pivmecillinam (an extended-spectrum penicillin) as second-line therapies (7). Isolates are classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) (technical note C) or extensively drug-resistant (XDR) (technical note D) based on the presence of genetic markers of resistance.

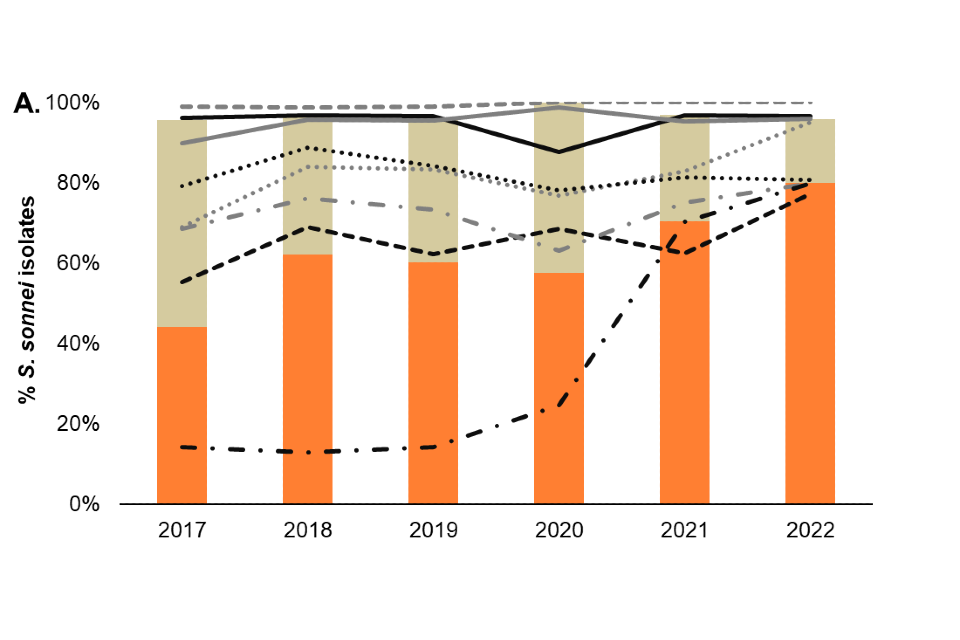

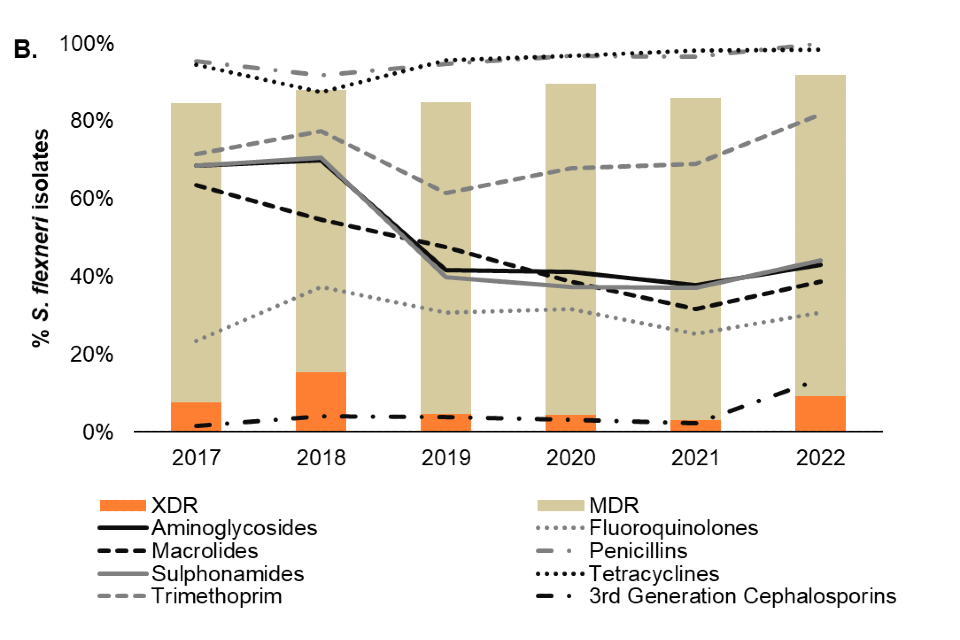

Among presumptive MSM (technical note B), antimicrobial resistance is consistently high in both S. sonnei and S. flexneri isolates, with 96% and 92% of isolates classified as MDR or XDR in 2022 (to Q2), respectively (Figure 5).

There has been a sustained increase in the proportion of XDR S. sonnei from 58% in 2020 to 70% in 2021, and subsequently 80% of diagnoses in 2022 (to Q2), this is driven by the resurgence of a S. sonnei Clade 5 outbreak strain that had acquired ceftriaxone resistance and was characterised as XDR in Q3 2021 (6) (Figure 5). Reporting of XDR S. flexneri isolates was also relatively more frequent in 2022 (9%) compared to 2021 (3%). In addition, 14% (25 out of 183) of S. flexneri isolates reported in 2022 harboured markers of resistance to third generation cephalosporins relative to 2% (6 out of 261) in 2021.

Markers of resistance to fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, were present in both S. sonnei (95%) and S. flexneri (31%) isolates among presumptive MSM in England in 2022 (Figure 5). Furthermore, 77% of S. sonnei and 39% of S. flexneri isolates had resistance markers to macrolides, such as azithromycin.

Figure 5. Patterns of antimicrobial resistance detected, by antimicrobial and MDR/XDR (technical notes C and D) classification, in A) S. sonnei and B) S. flexneri isolates from presumptive MSM (technical note B), England, 2017 to 2022 (¶)

¶ Antimicrobial resistance is based on the presence of genetic markers. Isolates missing information on antimicrobial resistance markers and overall classification have been excluded. Data source: GDW (technical note A). Data up to quarter 2, 2022

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Hannah Charles, Gauri Godbole, Claire Jenkins, Holly Mitchell, Katy Sinka, Katie Thorley

Suggested citation

Thorley K, Charles H, Mitchell H, Jenkins C, Godbole G, and Sinka K. Sexually transmitted Shigella spp. in England – data up to quarter 2, 2022. September 2022, UK Health Security Agency, London

Technical notes

A. Data sources

Second Generation Surveillance System (SGSS): this dataset includes primary laboratory-based diagnostic data and has the advantages of automated reporting and national coverage, so provides the total number of Shigella spp. diagnoses reported in England from diagnostic laboratories.

Gastro Data Warehouse (GDW): faecal specimens from cases with gastrointestinal symptoms are sent to local hospital, private and regional laboratories in England for culture. Local hospital laboratories are recommended to submit presumptive Shigella spp. samples to Gastrointestinal Bacterial Reference Unit (GBRU) at UKHSA for confirmation and typing. Approximately two thirds of Shigella spp. samples are submitted to the GBRU.

Both GDW and SGSS datasets are restricted to contain only Shigella spp. diagnoses among adults (≥16 years) in England.

Data is updated on an annual or biannual basis and subject to current extraction and cleaning procedures. Therefore, it is possible data may differ from previous publications.

B. Presumptive men who have sex with men (MSM)

Data obtained from GDW does not include information on cases’ sexual orientation or sexual behaviour. These analyses consider adult males with no recent foreign travel history as a proxy for men who have sex with men (MSM), in alignment with research on the transmission of Shigella spp. in England (5).

C. Multidrug-resistant (MDR)

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) is defined as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in 3 or more antimicrobial categories (8).

D. Extensively drug-resistant (XDR)

Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) is defined as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in all but 2 or fewer antimicrobial categories (8).

References

1. Public Health England (2017) ‘Travel-associated Shigella spp. in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 2014’

2. Mitchell H and Hughes G (2018). ‘Recent epidemiology of sexually transmissible enteric infections in men who have sex with men’. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases: volume 31, issue 1, pages 50 to 56

3. Charles H, Prochazka M, Godbole G, Jenkins C, Sinka K, and contributors (2021). ‘Sexually transmitted Shigella spp. in England: 2016 to 2020’. Public Health England.

4. HIV Prevention England (2022). ‘Maybe It’s Shigella resources and webinar’

5. Mitchell HD and others (2019). ‘Use of whole-genome sequencing to identify clusters of Shigella flexneri associated with sexual transmission in men who have sex with men in England: a validation study using linked behavioural data.’ Microbiology Society: volume 5, issue 11

6. Charles H and others (2022). ‘Outbreak of sexually transmitted, extensively drug-resistant Shigella sonnei in the UK, 2021-22: a descriptive epidemiological study’. The Lancet Infectious Diseases

7. World Health Organization (2005). ‘Guidelines for the control of shigellosis, including epidemics due to Shigella dysenteriae type 1’.

8. Magiorakos AP and others (2012). ‘Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance.’ Clinical Microbiology and Infection: volume 18, issue 3, pages 268 to 281