Interim report

Updated 26 January 2022

Executive summary

Introduction

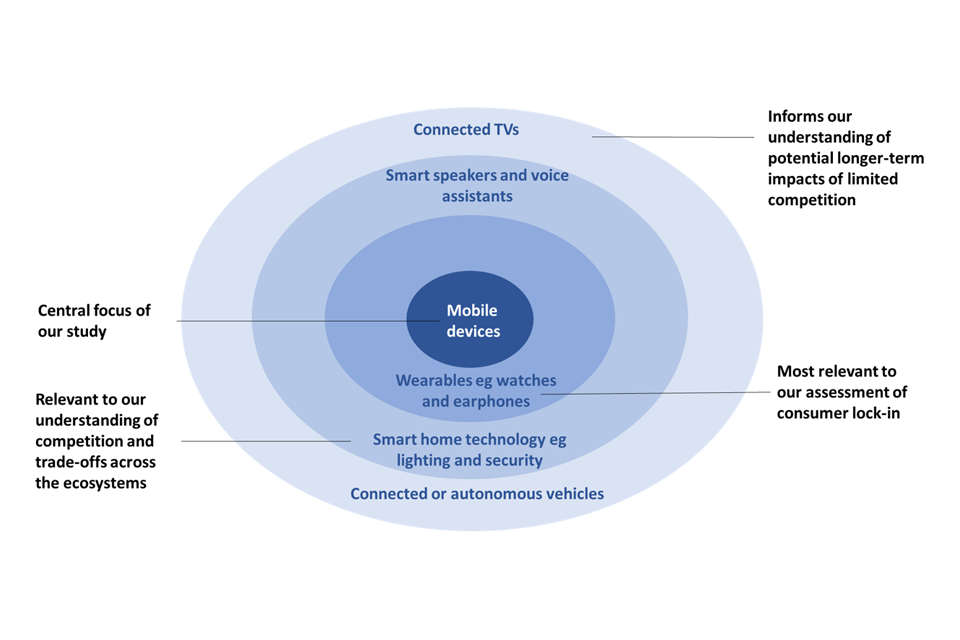

Mobile devices with internet connectivity such as smartphones and tablets now play a fundamental role in the lives of UK citizens, providing fast and convenient access to a wide range of products, content and services. In addition to communication, mobile devices also give us instant access to the latest news, music, TV and video streaming, shopping, games, fitness tracking and much more. They can also be connected to a wide range of other devices such as smart speakers, smart watches and home security and lighting. These products and services are now able to work in combination with each other, in a way that strengthens the value and functionality of each, within what we refer to as mobile ecosystems.

Mobile ecosystems can be broadly characterised as comprising the following core set of products:

-

mobile devices: portable electronic devices that can be held in the hand, including smartphones and tablets, and can connect to the internet

-

mobile operating systems: the pre-installed system software powering mobile devices

-

mobile applications (or ‘apps’): pieces of computer software providing functionalities to mobile devices. Some apps come pre-installed on devices (including, notably, mobile app stores and browsers), while others can be selected and installed by the user.

Mobile devices generally come with at least one app store and one browser pre-installed on them. These are the 2 key channels through which users and content providers can connect through 2 main channels of content distribution:

-

native apps: these are applications written to run on a specific operating system and, as such, interact directly with relevant elements of the operating systems in order to provide relevant features and functionality. Native apps can be pre-installed on devices or otherwise are typically downloaded through app stores [footnote 1]

-

browsers and web apps: mobile users can access websites through the browser on their devices, or ‘web apps’, which are applications built using common standards based on the open web, and are designed to operate through a web browser. Web apps have additional functionality compared to standard websites.[footnote 2] Web apps should in principle work on all browsers and on any operating system due to the common standards of the open web

When consumers today purchase a mobile phone, they effectively enter into one of 2 mobile ‘ecosystems’ – one operated by Apple, powered by the iOS [footnote 3] operating system; the other operated by Google, powered by Google-compatible versions of the Android operating system.[footnote 4]

The operating system on a mobile device determines and controls a range of features that are important to users of mobile devices, ranging from the appearance of the user interface, through to the speed, technical performance, and security of the device. They can also determine what kinds of software (applications) can run on top. As suppliers of the 2 key mobile operating systems in the UK, Apple and Google are able to make a number of key decisions that can have significant implications for the products and services that are accessed online.

Apple and Google also control the key gateways through which users access content on mobile devices and through which content providers can access potential customers:

-

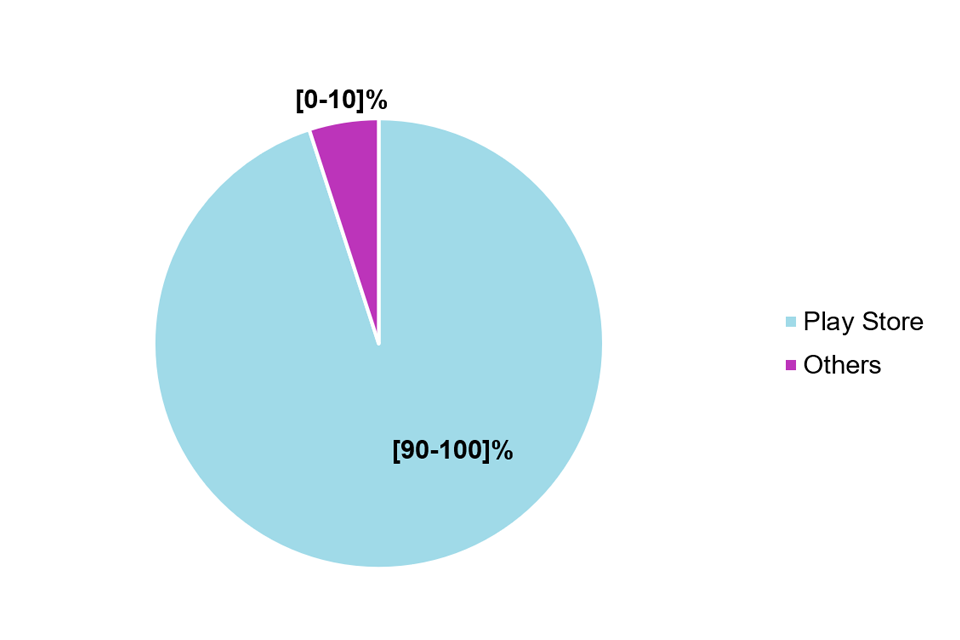

Apple’s App Store is the only permitted app store on iOS devices and Google operates the Play Store, which is used for the discovery and download of over 90% of all native apps on Android devices.[footnote 5] Apple and Google are in a position to determine which apps are allowed in their store, how apps are ranked and discovered, and also often charge significant levels of commission (up to 30%) on app developers’ revenues from in-app transactions, by requiring these transactions to be made through their own in-app payment systems. At the same time, Apple and Google also offer their own ‘first-party’ apps to users.

-

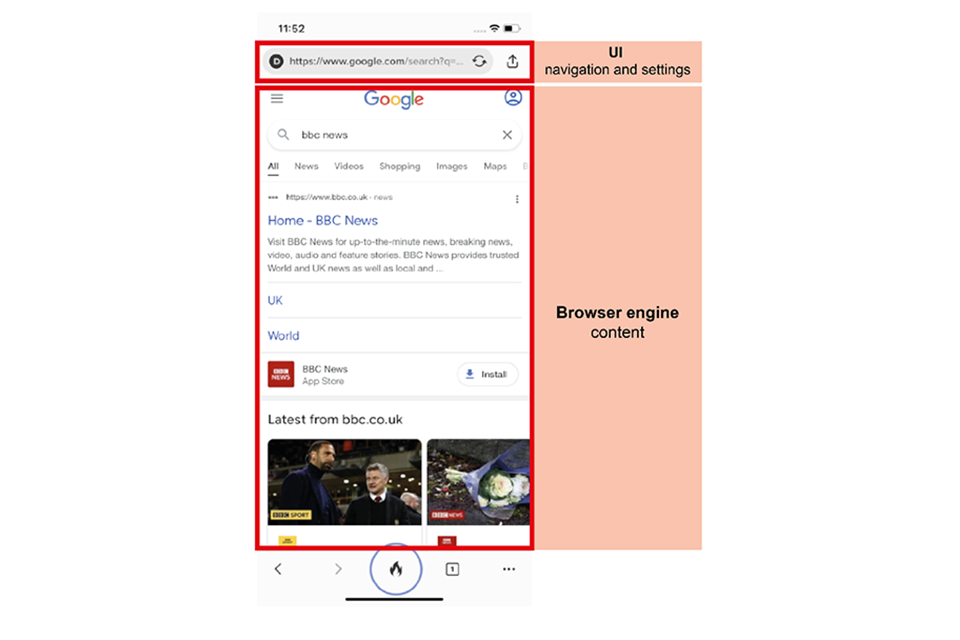

Apple’s browser, Safari (over 90%) and Google’s browser, Chrome (75%) have very strong shares of browser usage in their respective mobile ecosystems and are generally pre-installed for use when a user first turns on the device. As Apple operates the only browser ‘engine’[footnote 6] that runs on iOS and as Google operates the main browser engine on Android devices, each is in a position to determine the functionality and standards that will apply not only to their own browsers, but to competing browsers and, in turn, to web apps.

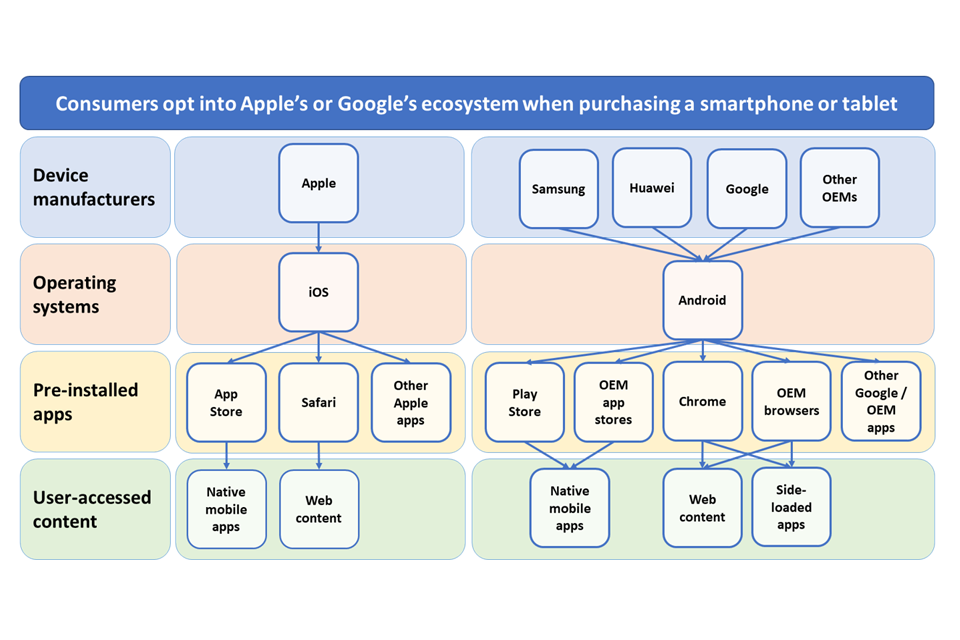

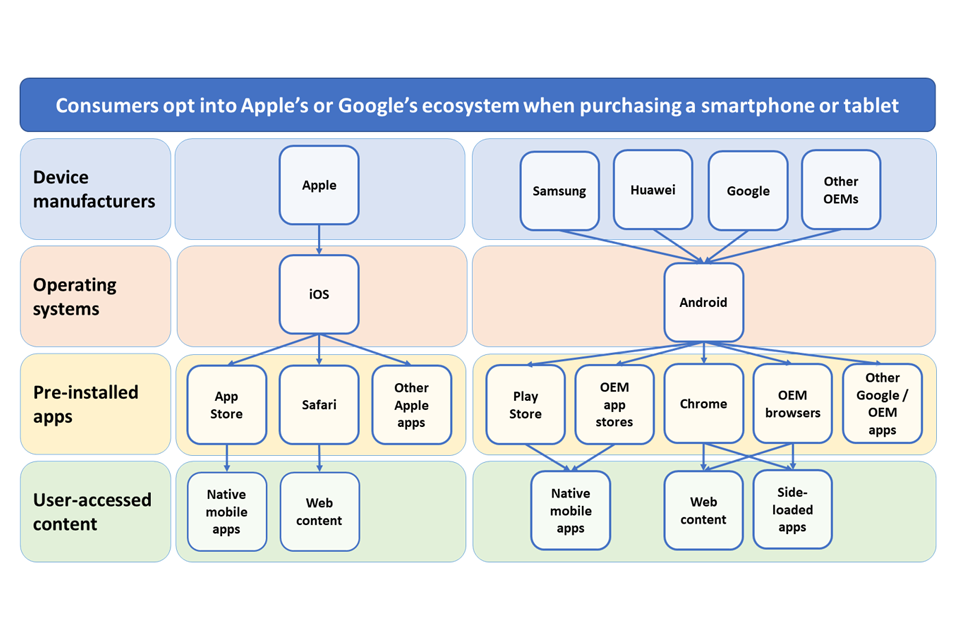

Figure 1 below illustrates how the control of their respective operating systems give Apple and Google the ability to influence outcomes in other aspects of the overall ecosystem.

Figure 1: the choice between Apple’s and Google’s mobile ecosystems

Figure description: A diagram showing the nature of the choice between Apple and Google’s mobile ecosystem and the control each firm has over the main gateways through which users access online content. The diagram lists user choices on the device manufacturer level, the operating system level, for pre-installed apps and for user accessed content. For Apple, the diagram shows Apple as the only choice on the manufacturer level, on the operating system level there is only iOS, for preinstalled-apps there is the AppStore, Safari and other Apple apps. Users can access native mobile apps and web content. For Google’s ecosystem, the diagram lists Samsung, Huawei, Google, and other OEM’s as decive manufacturers; and Android as the only operating system. On the level of pre-installed apps the diagramm lists Play Store, OEM app stores, Chrome, OEM browsers, and other Google/OEM apps. Users can access native mobile apps through the Play Store and OEM app stores, and web content and side loaded apps via Chrome or OEM browsers.

What is at stake for consumers?

As well as accounting for the majority of internet usage in the UK – with internet users spending almost 3 hours a day on average online using a smartphone or tablet – mobile devices are also the channel through which an increasing range and volume of other products and services are accessed and consumed. Mobile devices are a platform through which millions of apps from hundreds of thousands of app developers are made available to users and also an important platform for innovation.

It is important to recognise that Apple’s and Google’s control over their respective ecosystems can give rise to a number of positive outcomes. For example:

-

having an operating system, app store, and a core set of apps (as well as, for Apple, mobile devices) developed by a single provider help guarantee that products work seamlessly together, and are easy and convenient for users. Apple’s and Google’s ecosystems have each proven to be highly valued by consumers. We have received evidence that overall users’ satisfaction with both iOS and Android smartphones is high with over 9 in 10 satisfied with their device.

-

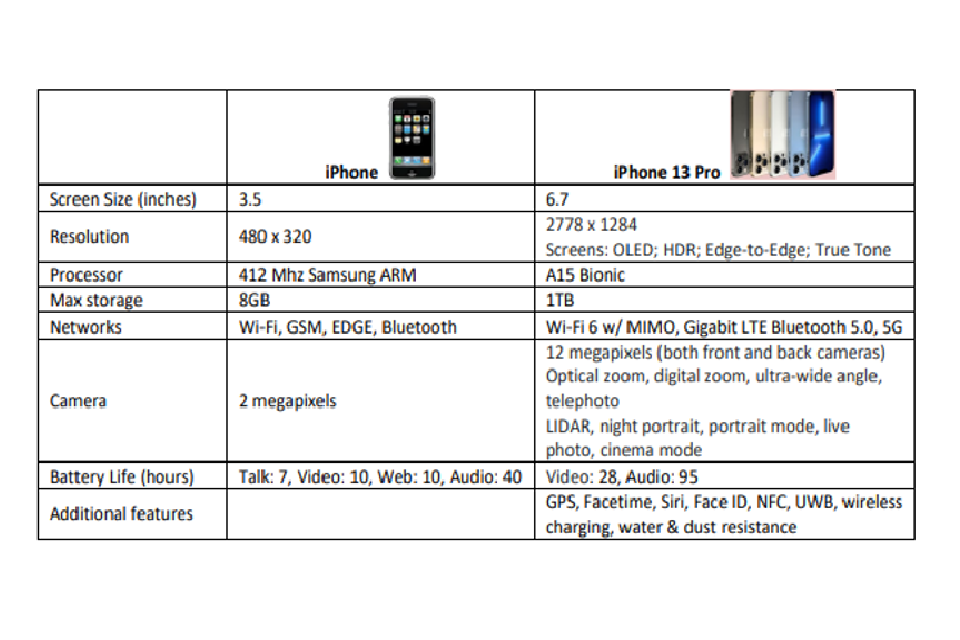

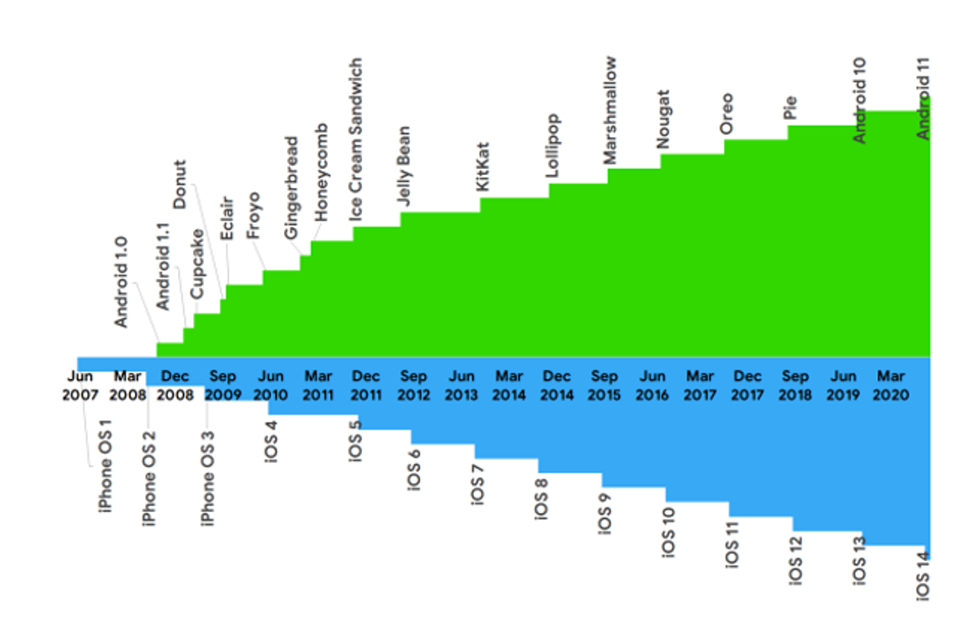

Apple and Google (and others) have engaged in innovation that has improved the features, functionality and performance of their mobile devices and operating systems as well as the tools they provide to support app developers. This innovation will have benefitted users as it has made devices quicker, more powerful and increased the number of things consumers can do on their mobile devices

-

we have heard from some app developers that Apple’s and Google’s stewardship of their ecosystems, in particular through app review processes and strong security features, helps to create consumer confidence and trust, which is vital for small start-ups and unknown brands. We have also heard that having 2 stable, secure, and trusted platforms helps to create the conditions that are needed to encourage investment in future innovation, and that by providing and maintaining app stores with low costs of entry for the majority of developers, Apple and Google enable new businesses to come forward that otherwise may not be viable

-

we also recognise that the revenue earned from Apple’s and Google’s core services funds the provision of a large number of other valued services for free to users, including the app stores, browsers and their underlying engines, and many other first-party apps

However, the level of control exerted by Apple’s and Google’s in relation to operating systems, app stores and browsers means that it is very difficult for another ecosystem to emerge. Further, because Apple and Google control the way that browsers perform on their devices; and also set the terms for access to their app stores for native apps, they are able to limit competition from third parties in various ways within their ecosystems.

Weak competition within and between Apple’s and Google’s mobile ecosystems can affect consumers in the following ways:

-

innovation: barriers to competition (particularly from third parties) risk holding back innovation in digital markets. For example, certain types of service may not be available to users (such as cloud gaming services on iOS devices), or certain developments in technology may be held up where Apple or Google do not have a clear incentive to promote these (such as web apps on iOS devices). Further, third parties investing in innovative products such as apps, services or connected devices which could complement the existing ecosystems may be discouraged from doing so, for example due to a fear of their data being used in order to further the development of Apple’s and Google’s own apps. Consumers may also lose out indirectly where, for example, the way that app stores are designed (including the ranking of apps) or terms imposed on app developers by Apple and Google, such as high rates of commission, have an impact on which apps succeed.

-

the user experience: although overall satisfaction with smartphones is high there may be some ways in which users are not making informed and effective choices within mobile ecosystems. For example, the pre-installation of certain apps or setting certain apps as the ‘default’ can have significant impacts on user behaviour and give an advantage to Apple’s and Google’s own apps. The design of app stores and in particular the way in which search results are ranked can have a significant impact on which apps succeed

-

privacy, security, and safety online: through design choice or other policies, Apple and Google are often in the position of acting in a quasi-regulatory capacity in relation to users’ security, privacy, and online safety. In many cases they opt to make decisions on behalf of consumers. However, it is not always clear if these numerous choices – ranging from restrictions on browser functionality to policies that affect targeted advertising – are in all cases made fully in the interests of consumers. For example, in many cases it seems decisions made on the grounds of protecting users’ security and privacy would also serve to give an advantage to first-party apps, or otherwise limit consumer choice

-

prices: both Apple and Google are consistently making substantial profits with high margins, meaning that their prices go well beyond recovering the costs of providing these goods and services. In particular, Apple’s device sales, as well as for app distribution and search advertising revenue for both firms, are all highly profitable. We can infer from this that the prices charged for Apple’s devices, Google’s search advertising fees and each firms’ app store commissions, are likely to be above a competitive rate in each case. These high prices will in most cases ultimately be borne, directly or indirectly, by consumers

An important challenge within this market study is to consider the extent to which potential consumer harms are sufficiently justified by the possible benefits identified by Apple and Google regarding their positions and practices.

Some parties argue in particular that opening up ecosystems to greater competition and choice may mean less convenience for users, or create risks for security and privacy protections. These considerations are considered further in this report and will continue to be a key focus in the second half of our study.

Finally, some of Apple’s and Google’s practices and restrictions on third parties may also form part of the way in which Apple and Google compete with each other to attract and retain customers for their mobile ecosystems. We have taken this into account as part of our assessment, where relevant.

Apple’s and Google’s business models and incentives

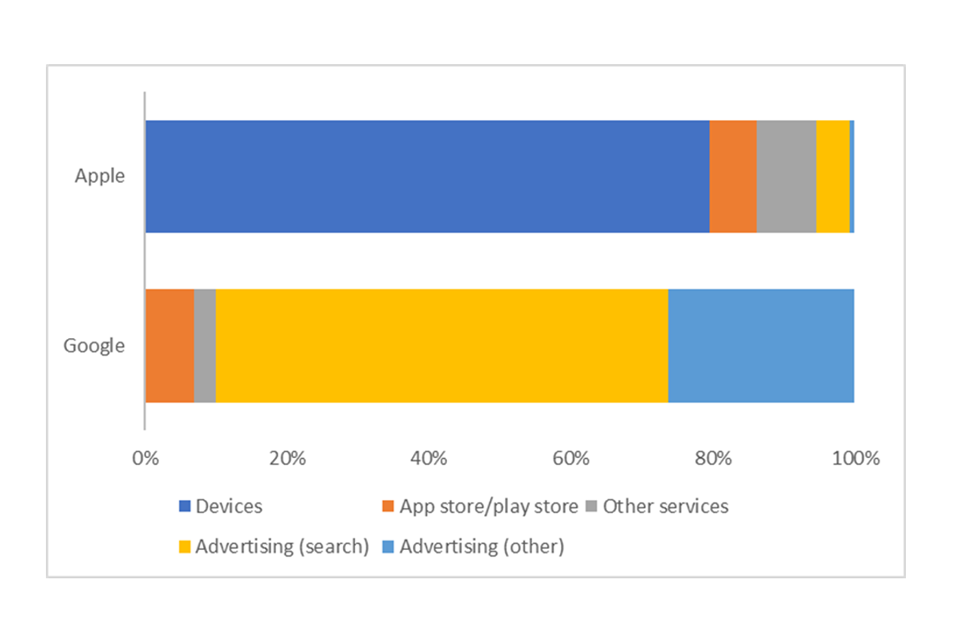

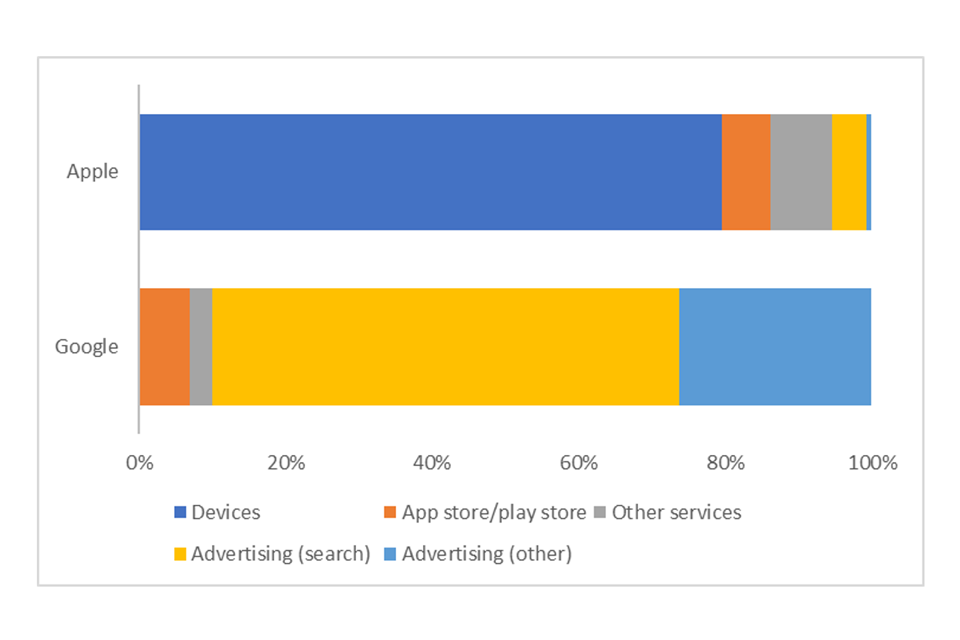

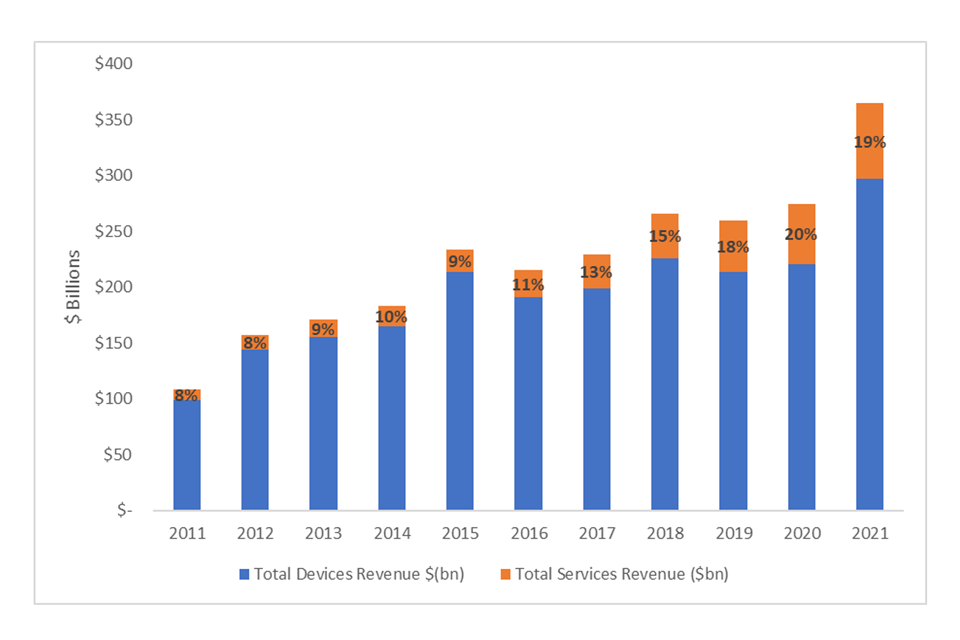

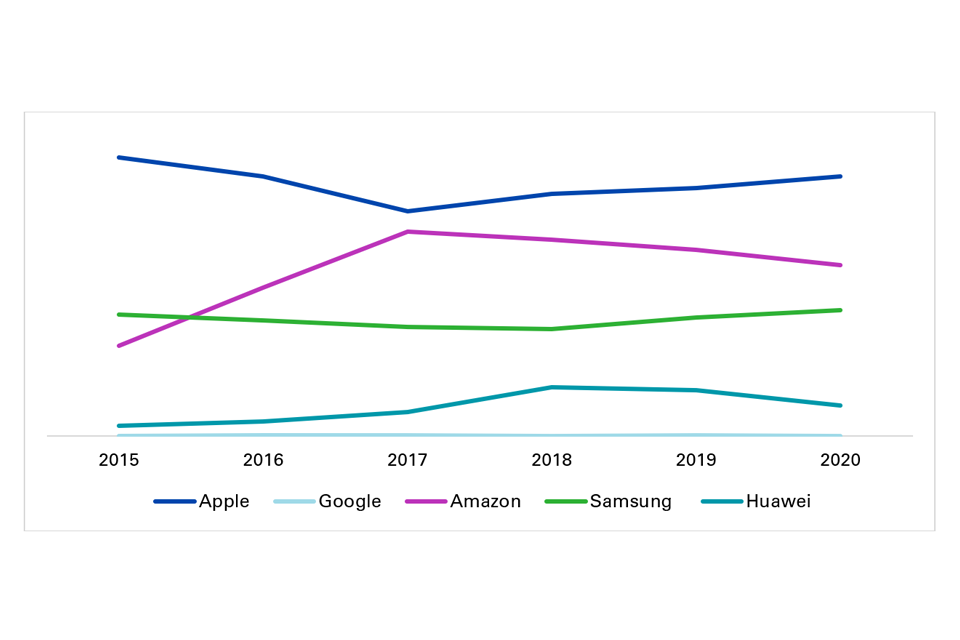

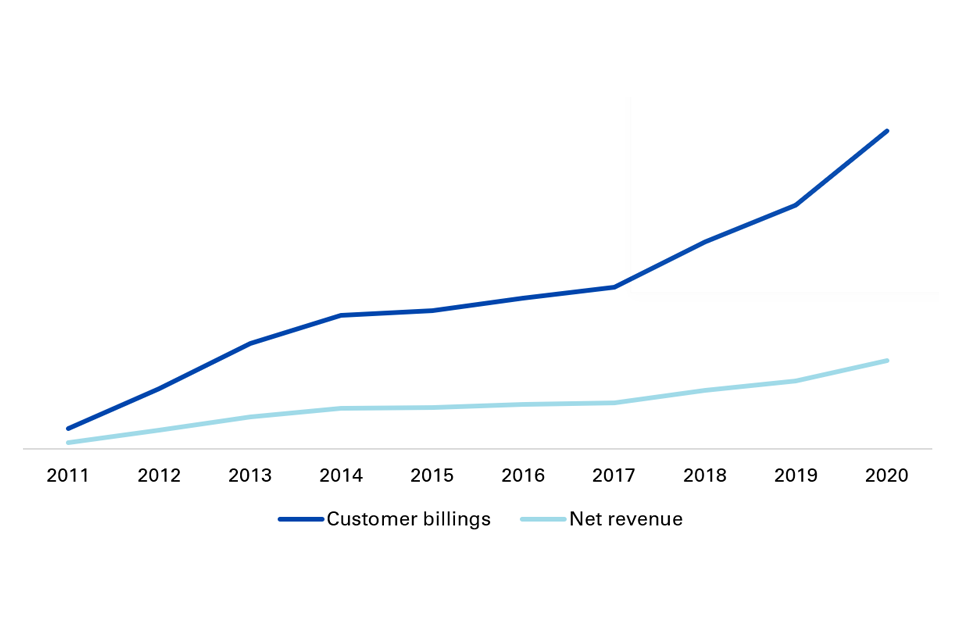

As illustrated by Figure 2, Apple and Google have different business models, each with their own key sources of revenue. This affects their incentives and the way that they have developed their mobile ecosystems over time.

Figure 2: breakdown of Apple’s and Google’s 2020 global revenue

Figure description: A chart showing key sources of revenue for Apple and Google in 2020. For Apple the breakdown is: Devices the majority of its revenue, second highest source are other services, third is the App Store, fourth advertising (search), fifth advertising (other). For Google the highest source of revenue is advertising (search), followed by advertising (other), third highest revenue source is Play Store the fourth other services.

Source: CMA analysis based on data submitted by Apple and Google. Note: There are some limitations to this data that we will seek to address for our final report: in particular the chart does not include revenue for Google’s mobile device sales and the Apple devices total excludes wearables. In each case we anticipate including the omitted data will make a small change to the overall picture.

Apple has made the vast majority of its mobile device revenues from sales of comparatively more expensive mobile devices. Through its vertically integrated model, it operates tight control over the hardware and software that run on those devices, in order to achieve security, interoperability and ease of use within its mobile ecosystem. Apple argues that its integrated model gives its products a distinctive ‘look and feel’ and that quality, security, privacy and integrity of user experience that they provided as a result of their vertically integrated offering attracts consumers to their devices.

Apple’s primary source of revenue comes from selling hardware and its associated operating systems (the iPhone and iOS) – in 2020 around 80% of Apple’s worldwide revenue came from its hardware, with around 50% coming from the iPhone alone. This means that Apple is likely to have an incentive to: (i) invest in new or enhanced features, services, and connected devices over time to maintain loyal customers, and also to encourage periodic replacement of older devices; and (ii) add friction to the process of switching away from Apple, as it does not earn any revenue from users of devices from other manufacturers.

Between 2016 and 2020, [footnote 7] Apple’s revenue growth has mainly been driven by ‘services’ (that is, income that is driven from content or applications that run on a mobile device) and from the operation of its App Store in particular. In order to pursue this growth strategy, Apple’s incentive is to encourage the download of native apps which offer paid content through its App Store as the primary way for users to access content on iOS devices, given the commission it receives from certain in-app purchases. This could be to the detriment of the development of browsers and web apps on iOS devices and native apps which are free to the user (although in some cases funded through advertising). Apple is also able to pursue policies which given an advantage to its own revenue-generating apps (such as Apple Music) over those of rivals, or otherwise block access to or increase development costs for third parties on its platform.

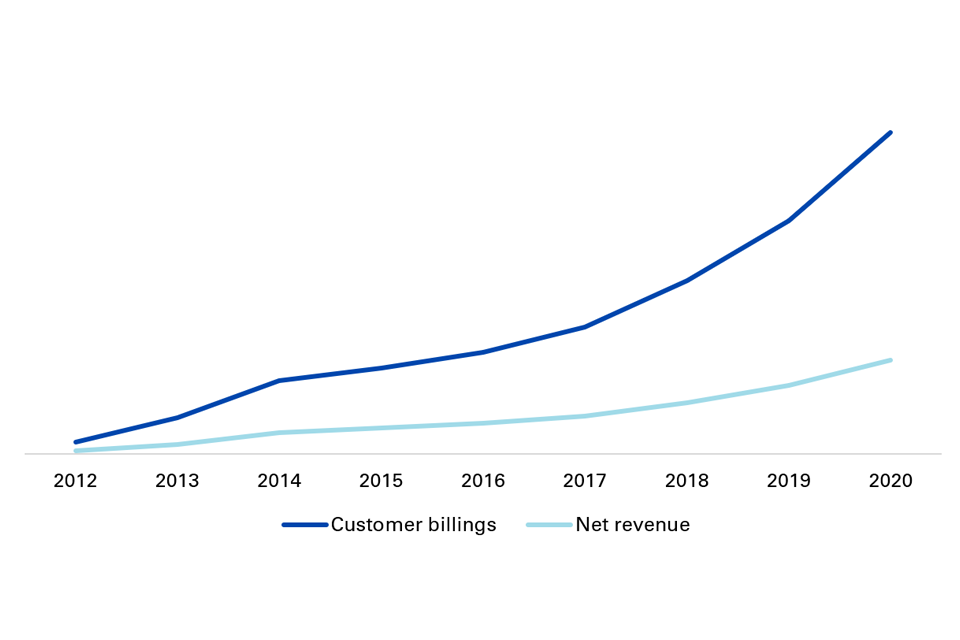

By contrast, Google is predominantly an advertising business. The majority of Google’s UK revenues are generated from search advertising, which totalled £6.8 billion in 2019 in the UK. Google therefore has a strong incentive to invest in products and services, such as its operating system and browser and to ensure that these are as widely adopted as possible, in order to generate traffic for its search engine and its other services that earn advertising revenues, including YouTube. This strategy has been successful to date, with more time spent on Google sites each day (52 minutes) by UK internet users than on any others.[footnote 8] Through the provision of these services, it is also able to take an active role in maintaining and promoting common standards across the open web.

While the Android operating system is available on an open-source basis, most manufacturers use a ‘Google compatible’ version of Android (referred to in this report as ‘Android’),[footnote 9] for which they are also able to licence key apps and services from Google. We consider Google’s agreements with device manufacturers seek to ensure that key Google apps are pre-installed prominently, such as its browser (Chrome) and its app store (the Play Store), and that Google Search is the default search engine at various search access points.

Like Apple, Google earns substantial revenue from its app store, which has seen rapid growth. Google appears to be moving towards tighter rules around the Play Store in certain respects, which are more closely aligned to those of Apple, in order to drive greater revenues in this aspect of its business (particularly around the use of its own payment system for in-app purchases, through which it also collects a commission [footnote 10]. As a result of its operation of the Play Store, Google controls the main method of offering native apps across the vast majority of Android devices and, as for Apple above, there is a risk that Google could give an advantage to its own apps and services or otherwise block access to or increase development costs for third parties on its platform.

Both firms are highly profitable

Despite the differences in their business models, both Apple and Google earn substantial profits from their mobile ecosystems, with very high margins, and high returns on capital employed.

On a global basis, Apple made $67.1 billion in profit in 2020, and recent disclosures indicate that this grew to $109.2 billion in 2021.[footnote 11] We have estimated that in recent years, Apple’s return on capital employed has been over 100% – a high figure in any sector.

Google made $48.1 billion in profit globally in 2020.[footnote 12] Based on analysis from the CMA’s market study into online platforms and digital advertising,[footnote 13] we have estimated that the return on capital employed for the Alphabet Group (Google’s parent company) was 39% on average between 2011 and 2019. That previous study concluded that this figure had been well above any reasonable competitive benchmark for many years.

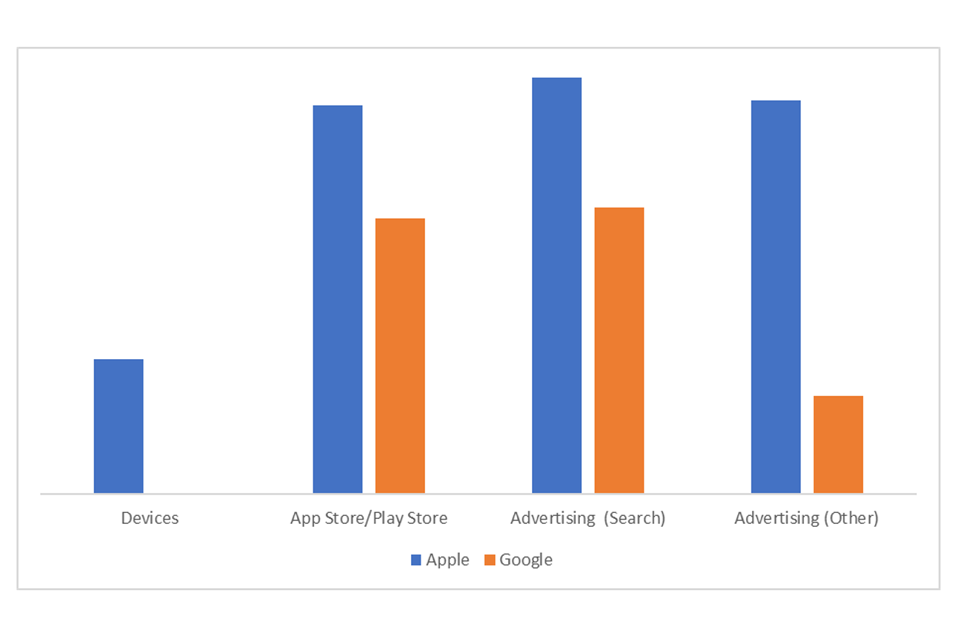

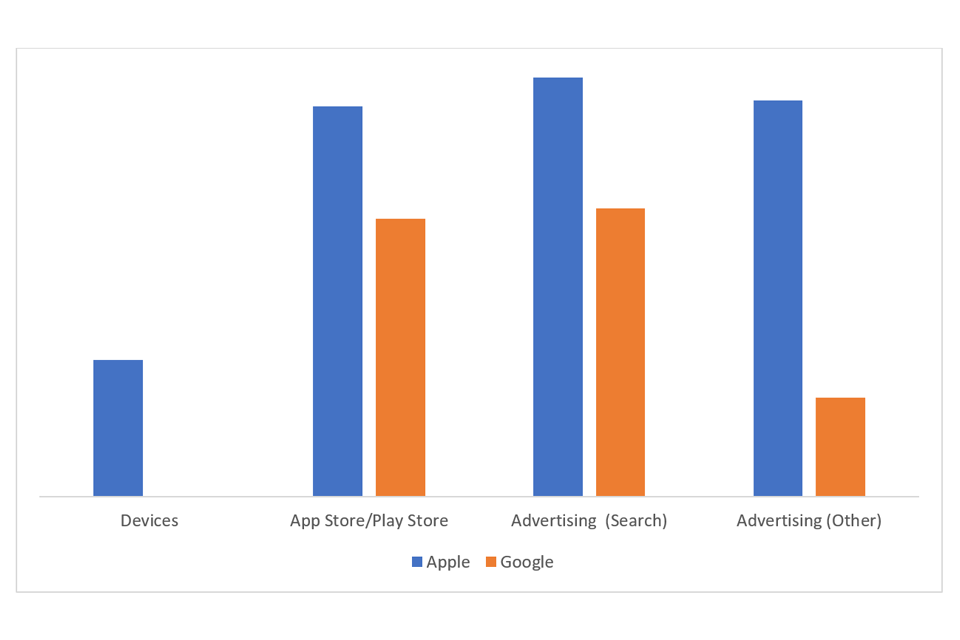

Gross margins represent the amount of money that companies retain after incurring the direct costs of providing the goods and services. Figure 3 illustrates the relative gross margins that Apple and Google earned from their main sources of revenue in 2020, indicating the strong performance of the app stores and search advertising for both firms.

Figure 3: gross margins by main sources of global revenue in 2020

Figure description: Gross margins for both Apple and Google by source of revenue. Apple’s highest margins are from advertising (search), closely followed by both advertising (other) and App Store, lastly lower margins are achieved with devices. Google’s margins are all lower than Apples. Google’s highest margins are achieved with advertising (search) closely followed by the Play Store, advertising (others) appears approximatly a third of the size of the other margins, no gross margins are shown for devices.

Source: CMA analysis of data submitted by Apple and Google. Note: Apple earns revenue from search advertising through a revenue share agreement with Google. Also, to note there are some limitations to this data that we will seek to address for our final report: in particular the chart does not include data for Google’s device sales.

The context of this market study

As set out in the statement of scope published at the launch of this study, following recommendations made by the CMA in our earlier market study into online platforms and digital advertising, and through the Digital Markets Taskforce,[footnote 14] the government has indicated that it intends to establish a new, pro-competition regulatory regime to address concerns relating to digital platforms with ‘strategic market status’ (SMS). A Digital Markets Unit (DMU) has been established within the CMA on a non-statutory basis to begin work to operationalise the new regime, and the government intends to introduce legislation to put the regime on a statutory basis when legislative time permits. The government recently consulted on proposals to bring this new regime into force,[footnote 15] which would result in firms assigned with SMS by the DMU facing enforceable codes of conduct, and potential pro-competitive interventions to address the sources of their market power.

The CMA expects that this market study will contribute towards the establishment of the new pro-competition regulatory regime, in particular by helping to inform the assessment of whether Apple or Google should be designated with SMS in relation to any of the activities captured by the scope of this study. This study also provides an opportunity to consider how, were Apple and Google to be so designated, key elements of the regulatory regime (as currently proposed) – in particular codes of conduct and pro-competitive interventions – might be used to address the potential harms to competition and consumers identified. Our preliminary views on these issues are set out further below.

As also noted in the statement of scope, in parallel to our work to develop the new regulatory regime, the CMA is also making use of our existing powers to the fullest extent possible to address concerns in digital markets. We have also launched 2 competition law enforcement cases, in connection with the prohibitions in the Competition Act 1998, which are related to important aspects of this market study. The first is an investigation into Apple’s App Store, in which the CMA is investigating Apple’s conduct in relation to the distribution of apps on iOS and iPadOS devices in the UK, in particular, the terms and conditions governing app developers’ access to Apple’s App Store.[footnote 16] The second is an investigation into Google’s ‘Privacy Sandbox’ browser changes, in which the CMA is investigating Google’s proposals to remove third-party cookies and other functionalities from its Chrome browser.[footnote 17] The CMA has recently published a notice of intention to accept modified commitments offered by Google and launched a consultation on these modified commitments.[footnote 18]

Our competition enforcement cases focus on specific suspected breaches of competition law, while our market study is seeking to provide a broader, overarching view of these interconnected markets.

We are also aware that other competition authorities and government bodies around the world are looking at similar issues to those we are considering in this study, or have previously carried out work in this area. For example, the European Commission is investigating whether Apple has breached competition law in relation to its distribution of apps,[footnote 19] having previously fined Google for imposing anticompetitive restrictions on Android device manufacturers and mobile network operators.[footnote 20] In addition, a number of private enforcement cases have been brought in the USA, UK and other jurisdictions, relating (among other issues) to Apple’s and Google’s management of their respective app stores.[footnote 21] Several other agencies are carrying out similar sectoral studies of mobile platforms, while new forms of regulation – including the sort of ex ante rules being considered in the context of the DMU – are also under consideration in a number of jurisdictions around the world, for example as part of the Open App Markets Bill in the United States and the proposed Digital Markets Act in the EU. In South Korea, legislation has recently been introduced which, among other things, prohibits Apple and Google from mandating the use of their in-app payment systems for in-app purchases of digital content.

Further action by other authorities could potentially result in changes that would affect market conditions in the UK. We continue to monitor the work carried out in other jurisdictions and, in turn, aim to contribute to the global debate on how to tackle the problems associated with digital platforms with substantial market power. This reflects our belief that the most effective way to promote competition in these markets will be through action that is internationally coherent, by achieving a common understanding of the problems and broad agreement over the way to tackle them.

Summary of competition concerns

As noted in our statement of scope, the CMA has structured its work according to the following 4 themes:

- theme 1: competition in the supply of mobile devices and operating systems

- theme 2: competition in the distribution of mobile apps

- theme 3: competition in the supply of mobile browsers and browser engines

- theme 4: the role of Apple and Google in competition between app developers

The initial findings of this market study are set out by theme below. Within these themes, we also explore the links that exist between Apple’s and Google’s different activities across their ecosystems.

Theme 1: competition in the supply of mobile devices and operating systems

Under Theme 1, we have been considering the extent to which there is competition in the supply of mobile devices and operating systems. This has included considering (among other issues) the extent of price competition, whether there may be natural barriers to entry and expansion in the supply of mobile operating systems such as network effects and economies of scale and whether there are barriers to switching that ‘lock’ consumers into a certain mobile ecosystem. In doing this we have also considered how Apple and Google may have contributed to any barriers to entry or barriers to switching.

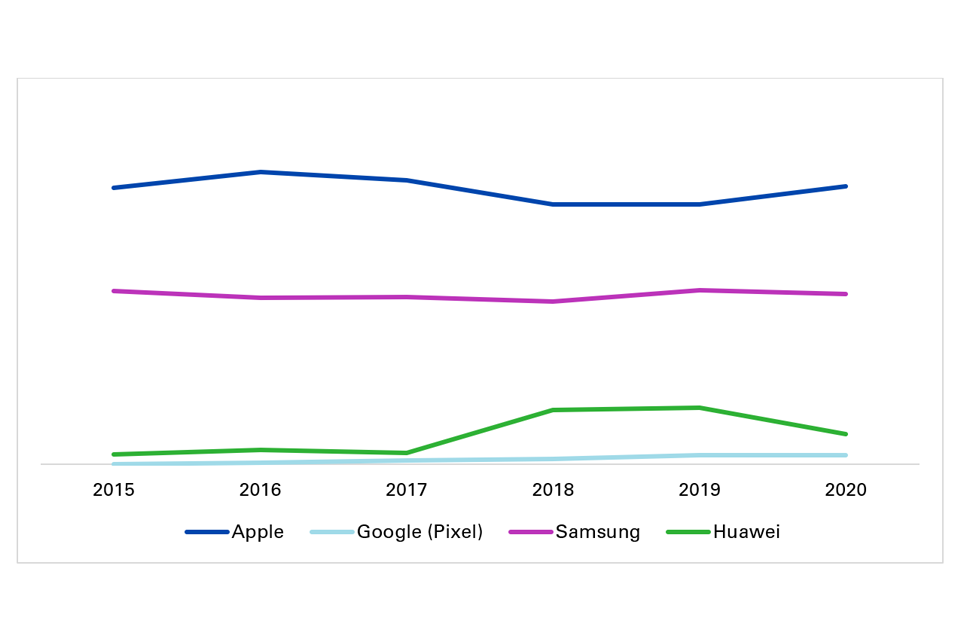

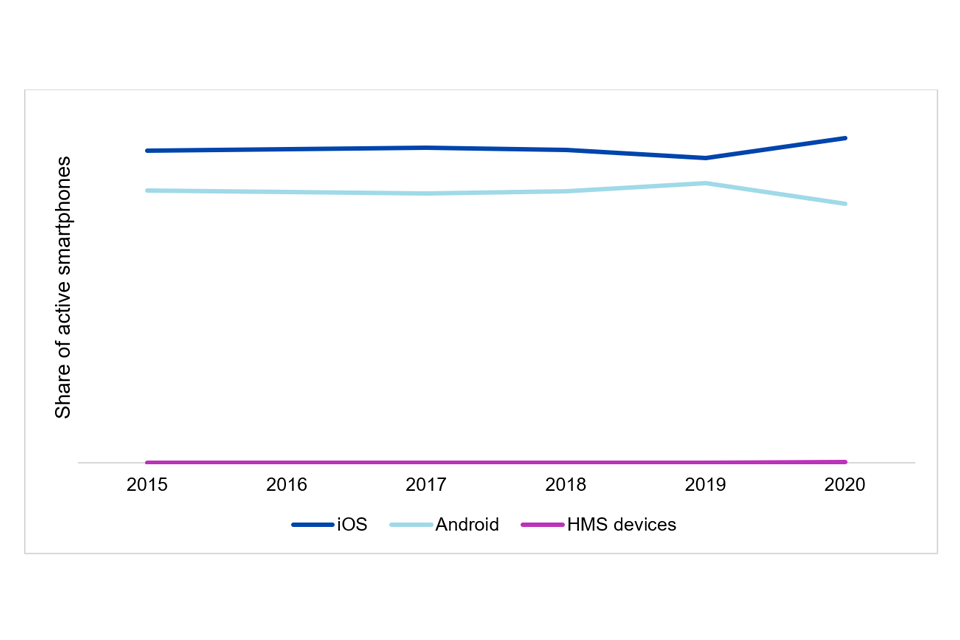

Consumers enter Apple’s or Google’s mobile ecosystems the first time they purchase a mobile device that uses the iOS or Android operating system. Apple and Google have an effective duopoly in the provision of operating systems that run on mobile devices, with similar shares of supply in the UK. In particular:

-

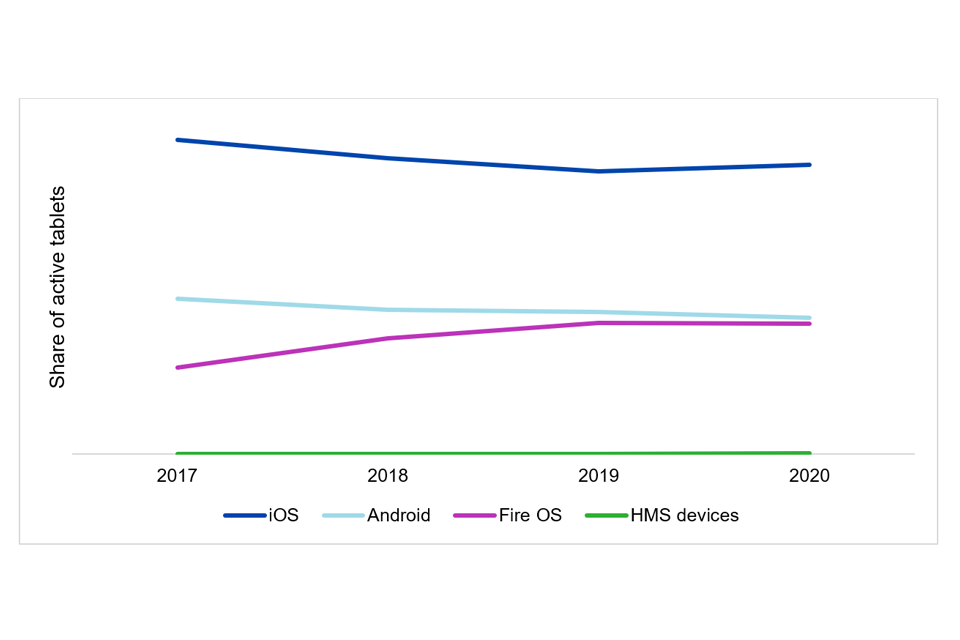

Apple is the largest player in the supply of both mobile devices and operating systems with a share of [50% to 60%] of active smartphones as well as [50% to 60%] of active tablets in the UK in 2020 [footnote 22]

-

in contrast, Google has a small presence in mobile devices with most Android devices being manufactured by third parties. Google’s Android is the second largest mobile operating system, with Android devices accounting for [40% to 50%] of all active smartphones and [20% to 30%] of active tablets in the UK in 2020

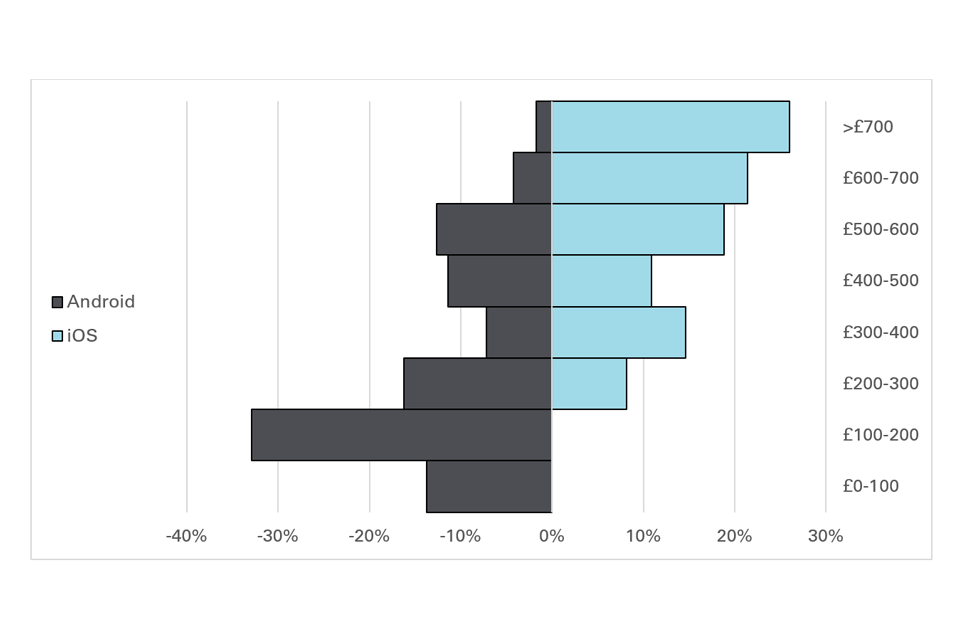

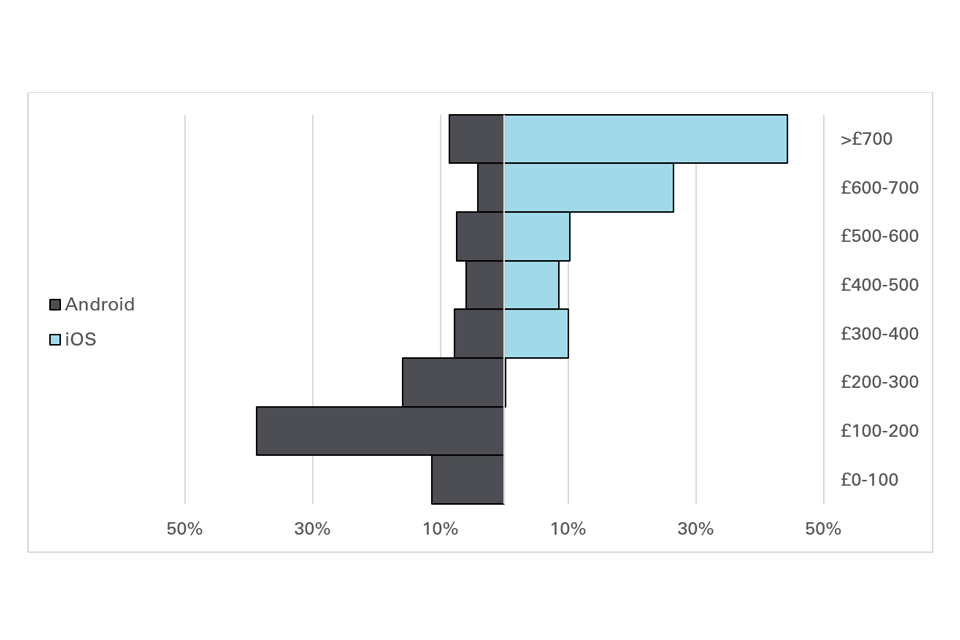

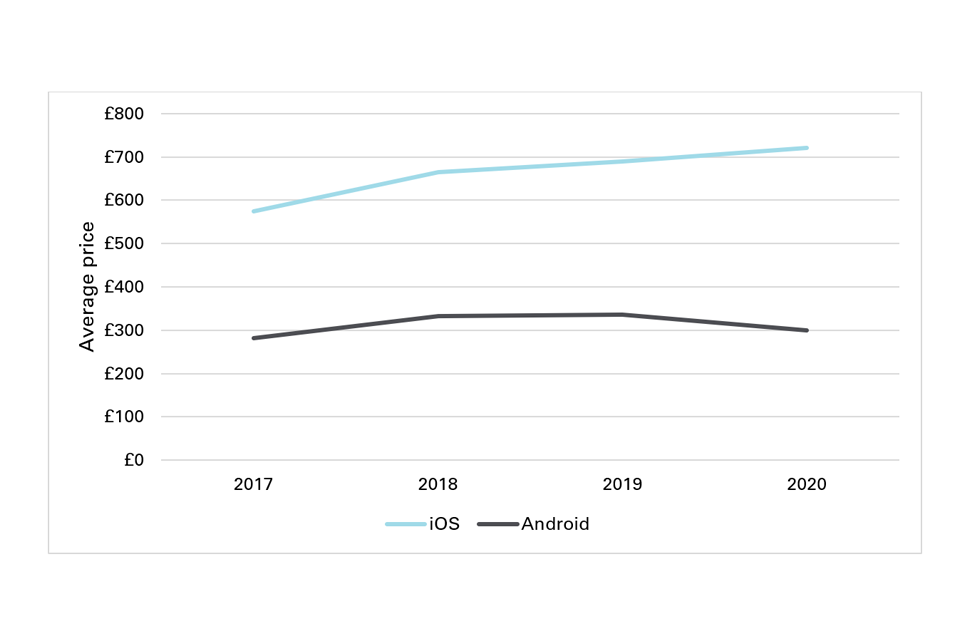

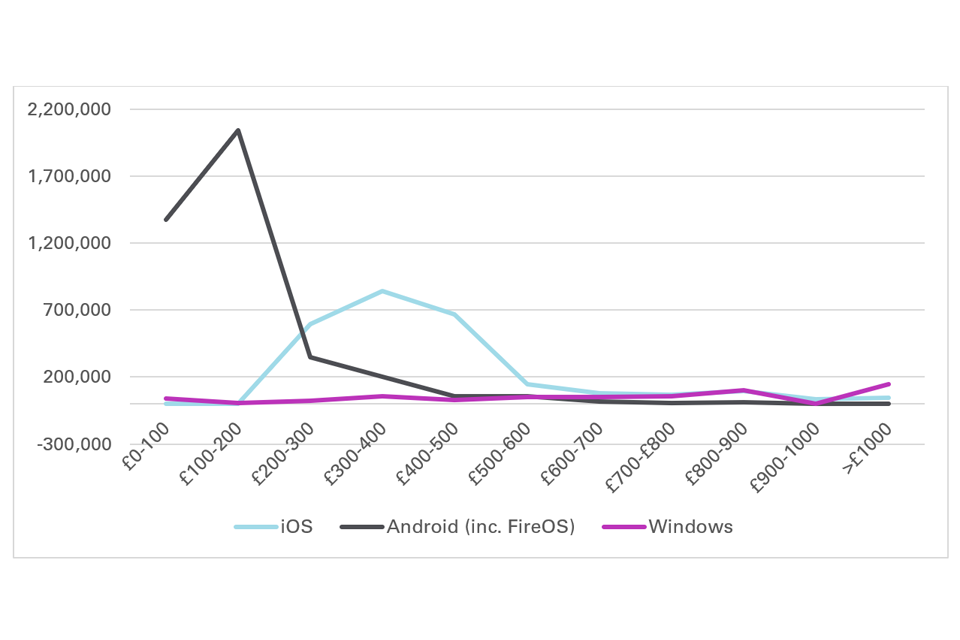

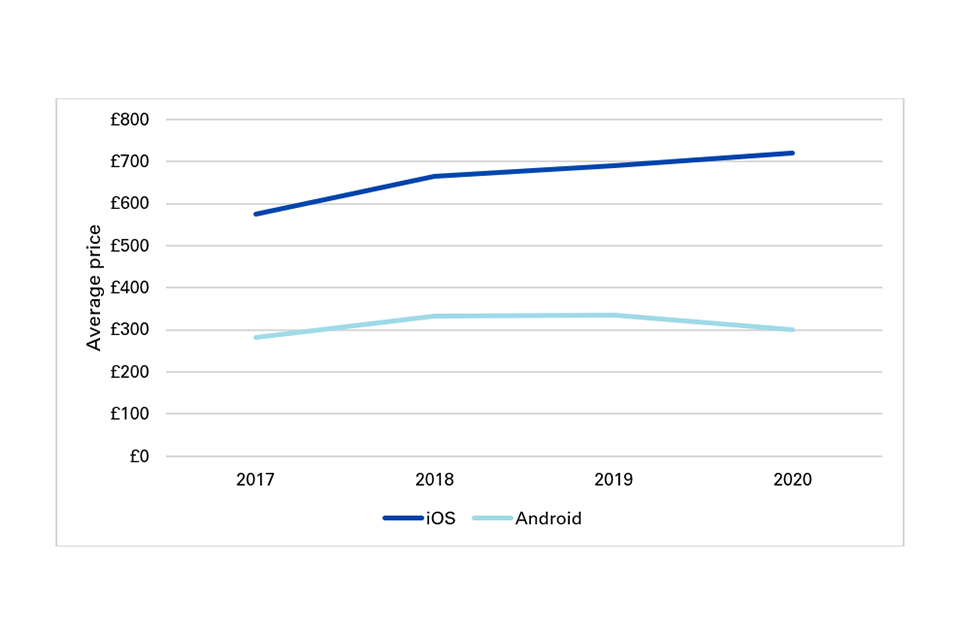

We have found that there is limited user-driven competition because most users purchasing a device are buying a replacement device and rarely switch between operating systems. Also, there appears to be limited price competition between iOS and Android devices and each effectively has its own segment of the market, with iOS dominating sales of high-priced devices and Android dominating sales of low-priced devices.

The evidence indicates that there are material barriers to switching between devices using the iOS and Android operating systems. The barriers include challenges that users may face when seeking to transfer data, apps and manage subscriptions when they switch devices, which stem in part from requirements to use Apple’s and Google’s in-app payment systems. The characteristics and Apple’s first-party apps, services and connected devices pose a further barrier to switching, due to their incompatibility, or limited compatibility, with devices built by other manufacturers. Barriers to switching are thus asymmetric, affecting users of Android and iOS but falling more heavily on iOS users. Overall, these factors mean that Apple and Google do not appear to be competing strongly with each other for users for their respective operating systems.

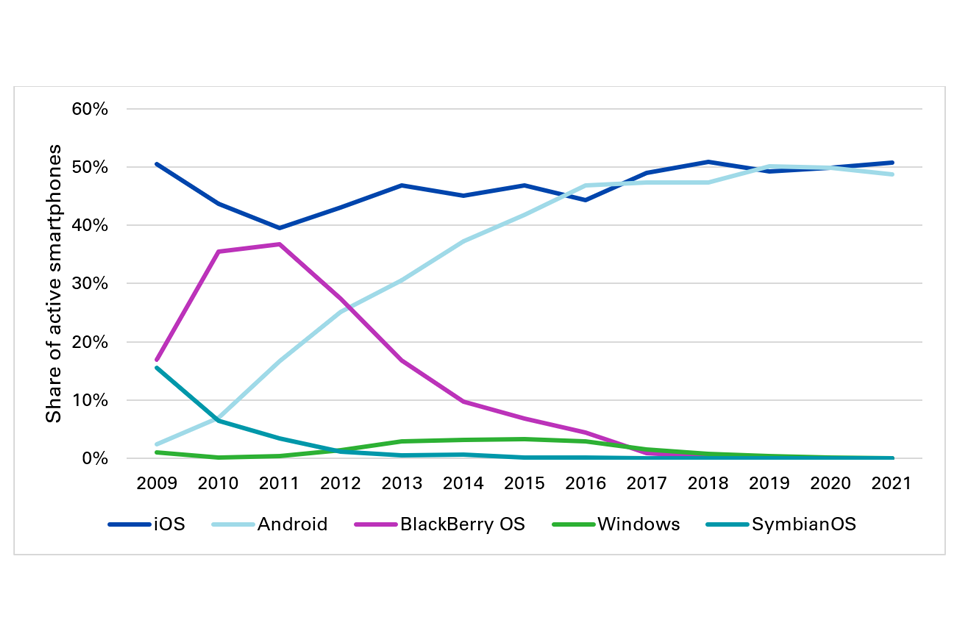

In addition, Apple and Google both benefit from material barriers to entry and expansion faced by rival providers of operating systems.

-

there are significant indirect network effects – the benefit to users of an operating system increases with the volume and quality of content and apps they can access through that operating system and similarly the benefit to content providers/app developers increases with the number of users they can access through an operating system. This means it is difficult for a new operating system to gain traction as they cannot attract one set of customers without the other

-

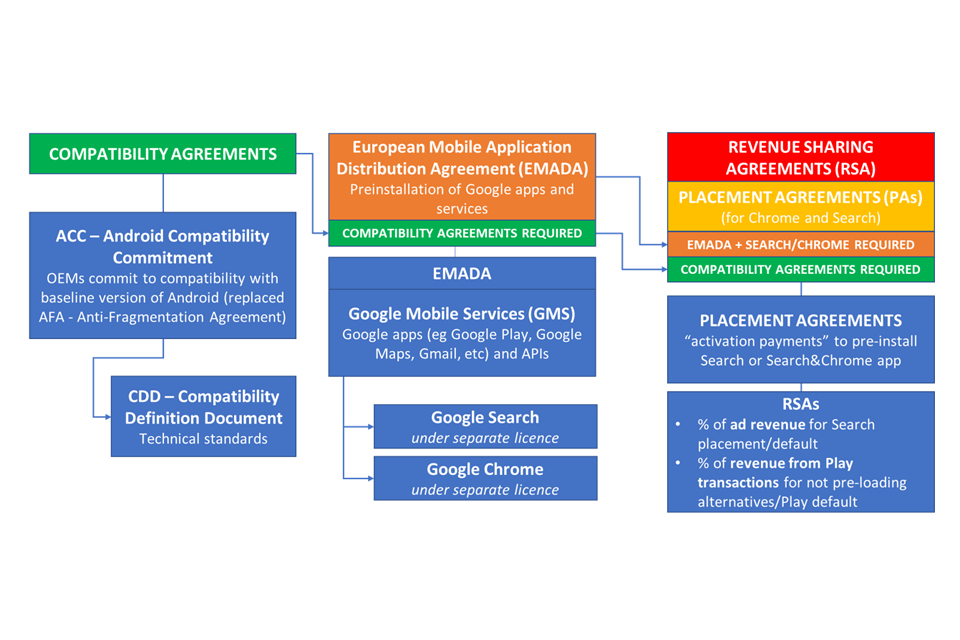

Google has various agreements with device manufacturers. These include agreements under which Google agrees to share a percentage of its search advertising revenue with the device manufacturer (typically in return for use of a Google compatible version of Android and setting Google Search as the default search engine at various points on their devices) and, in some cases, a percentage of its revenue from Play Store transactions for meeting additional requirements in relation to the Play Store.[footnote 23] It is very difficult for rivals seeking to attract manufacturers to their competing operating systems to replicate these arrangements

-

the barriers to users switching away from their current mobile ecosystems would substantially limit the chances of a new entrant. These barriers are greatest for Apple users, accounting, for [50% to 60%] of active smartphone users and [50% to 60%] of active tablets, in part due commercial decisions made by Apple

Given these barriers to entry and the fact that Android is the only licensable mobile operating system in the UK (and is the only large licensable operating system we are aware of internationally),[footnote 24] manufacturers have no credible alternative option but to use the Android operating system. Given this, Apple and Google face limited competitive constraints from providers of alternative operating systems for mobile devices.

Theme 2: competition in the distribution of mobile apps

Under Theme 2, we have examined the extent to which Apple and Google, as owners of the main app stores in their respective ecosystems, have market power in the distribution of native apps. This includes the extent to which there are suitable alternatives to the main app stores through which consumers can download and app developers can distribute native apps, as well as alternative methods through which a user can access the same content (for example, web-based alternatives and alternative devices such as games consoles).

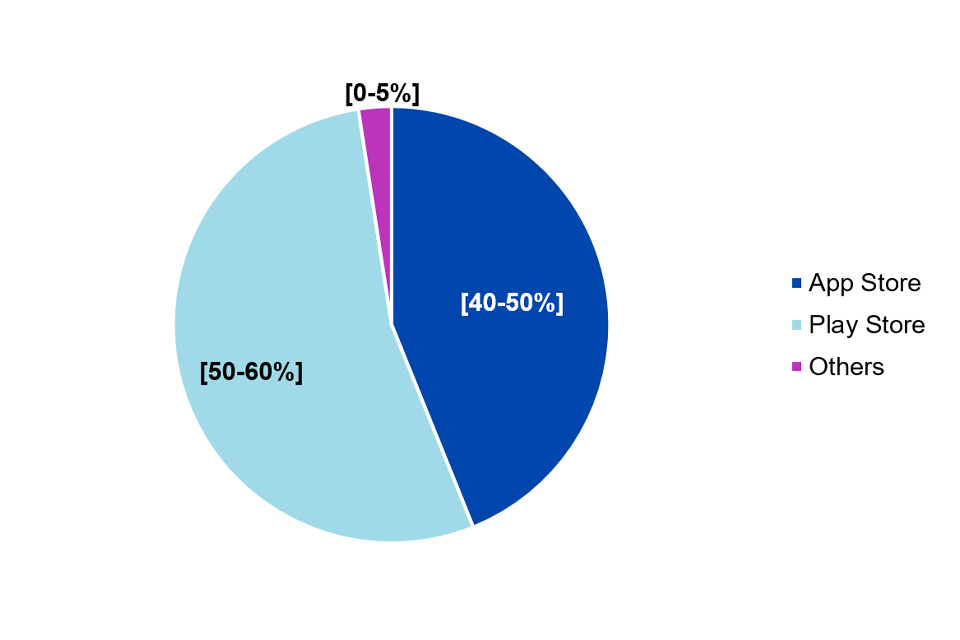

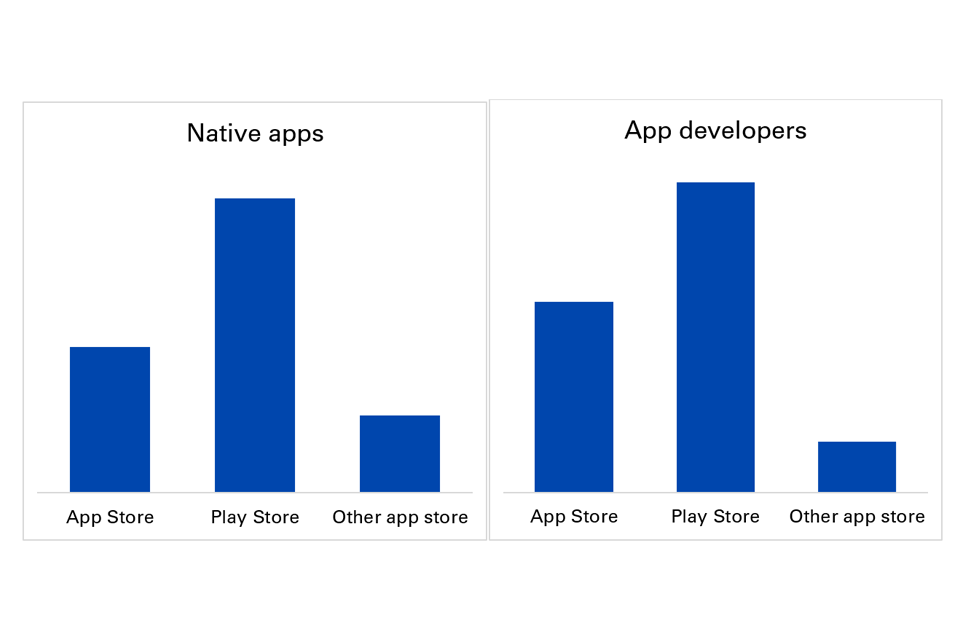

The App Store on iOS and Play Store on Android are the key gateways through which app developers can distribute apps to users on mobile devices. Our initial findings are that the App Store and Play Store face a lack of competition from within and outside of their respective ecosystems as a method of delivering native apps to users:

-

in Apple’s ecosystem, the App Store is the only method of native app distribution and so 100% of native apps downloaded on iOS devices are through the App Store

-

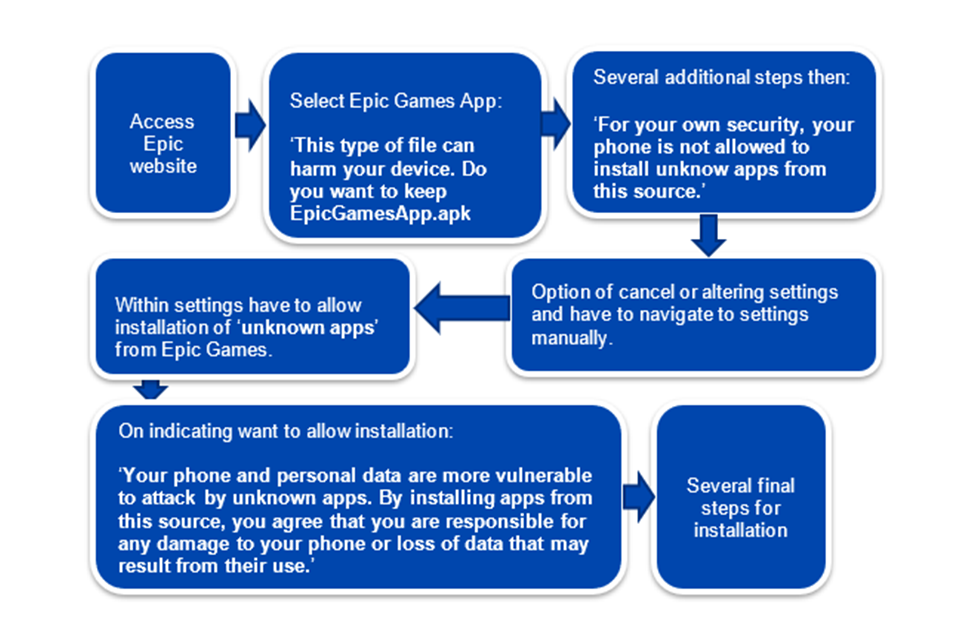

on Android devices,[footnote 25] [90% to 100%] of native apps are downloaded from the Play Store. Although alternative app download methods [footnote 26] do exist on Android, these are not viable or popular alternatives to the Play Store for the majority of users or app developers. Alternative app stores can be pre-loaded on Android devices (for example, those of the main device manufacturers[footnote 27]) but face significant barriers in attracting a sufficient number of app developers and users to be successful. Further, Google’s agreements with manufacturers[footnote 28] mean that the Play Store is pre-installed and prominently displayed on the vast majority all Android devices

-

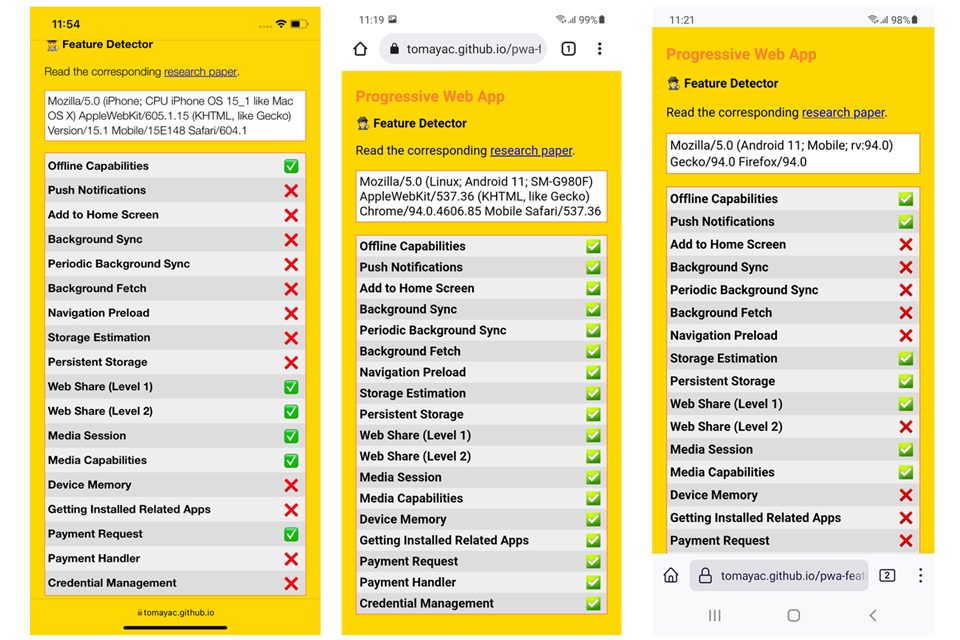

‘web apps’, which in principle allow developers to offer their apps directly to users circumventing the app stores, are not currently a suitable alternative to native apps for most app developers. In particular, web apps do not currently provide the same features and functionalities as native apps. The evidence indicates that this is largely due to restrictions on the features and functionalities of web apps that result from the fact that browsers on iOS devices must use Apple’s own WebKit browser engine. The lower functionality for web apps on iOS means that developers are unlikely to be able to rely on web apps for iOS and this is likely to significantly increase development costs, as the efficiency saving from having to only develop one app (ie one web app as opposed to a native app for each operating system) is lost

-

the App Store and Play Store do not represent strong competition for each other, as alternatives for users or app developers. The largest app developers are available on both app stores and see them as complements rather than substitutes due to their size and because most App Store users do not use the Play Store and vice versa. That is, they are, in effect, unavoidable trading partners for many app developers. In addition, as noted above, users rarely switch between Apple’s and Google’s operating systems when buying a replacement device

-

the App Store and Play Store do not face significant competition from alternative devices, such as desktops or games consoles, largely because they are used differently to mobile devices, which can be used ‘on the go’. Therefore, non-mobile devices are not seen as a viable alternative option for mobile app developers

Apple and Google are able to exercise the market power of their app stores through their processes for reviewing which apps can be listed on their app stores. Apple and Google set the rules to be followed by app developers and have discretion over whether to approve or reject apps. This control has enabled Apple to block certain types of apps being present on iOS altogether (such as cloud gaming services) and for other types of apps, the app review process for the App Store and Play Store provides an incentive or ability for Apple and Google to confer an advantage over their own apps and services and, more widely, can mean uncertainty and increased development costs for app developers.

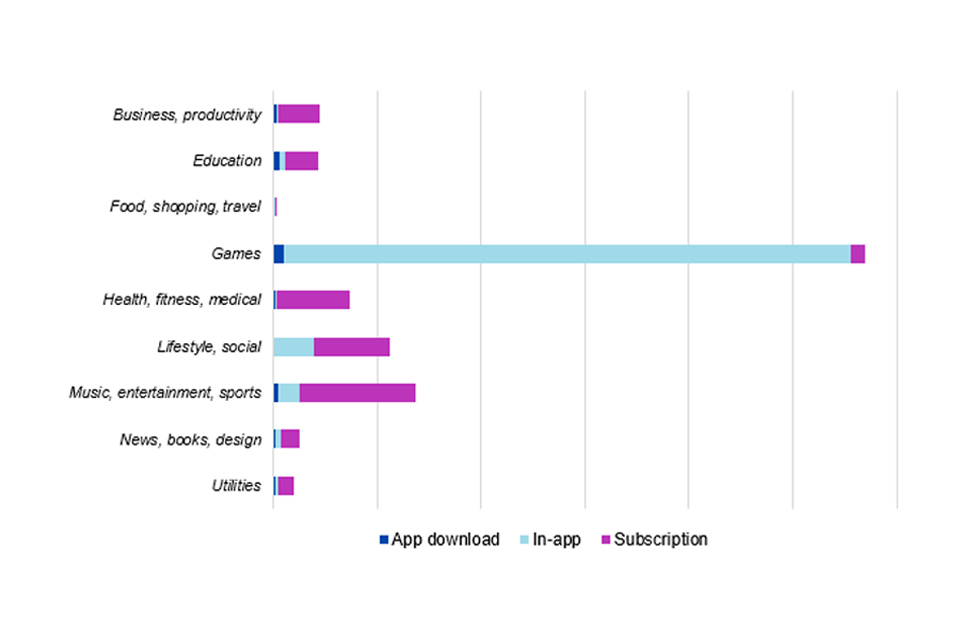

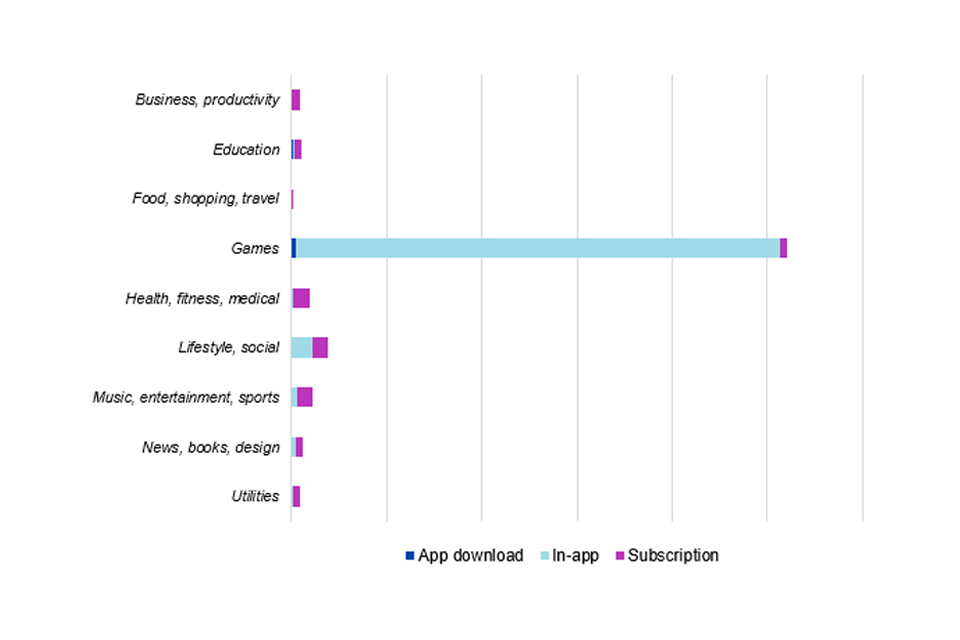

In addition, Apple and Google require app developers to use their payment systems for certain in-app transactions relating to digital content consumed within the app, and charge an average commission of close to 30%.[footnote 29] These commissions result in Apple and Google making substantial and growing profits (with high margins) from their app stores, consistent with market power.

We have also identified certain ways in which the control of access to the App Store enables Apple to introduce policies and terms, such as App Tracking Transparency, which may operate to the detriment of ad-funded apps, and which push users towards apps which derive revenue from users having to make in-app purchases (in relation to which it is able to collect a commission). These are considered further under Theme 4. In some respects such as these, we have found that Google does not have such strict rules as Apple.

Theme 3: competition in the supply of mobile browsers and browser engines

Alongside app stores, mobile browsers are the key gateway in the mobile ecosystem between users and content providers. Mobile browsers are a type of app that enable users of mobile devices to access and search the internet and interact with content on different websites through the open web. Mobile browsers also enable users to access web apps. Native apps can also be installed directly from mobile browsers through ‘sideloading’ on Android devices. Alongside app stores, mobile browsers are one of 2 key gateways in the mobile ecosystem between users and content providers. Browser engines are responsible for key functionality in browsers as they enable browsers to load and display content on a web page.

Under Theme 3, we have examined the extent to which Apple and Google, as owners of the 2 largest browsers and browser engines on mobile devices, have market power in the supply of mobile browsers. This includes an assessment of potential barriers to entry and expansion such as the restriction within iOS on browser engine choice, the role of web standards and webpage compatibility, consumer behaviour and the role of pre-installation and default settings for browsers on mobile devices. We have also assessed whether Google’s and Apple’s positions in the supply of browsers may enable them to hold up effective competition in ways which may protect their market position across their other activities (notably, their app stores or in the case of Google, its search advertising business).

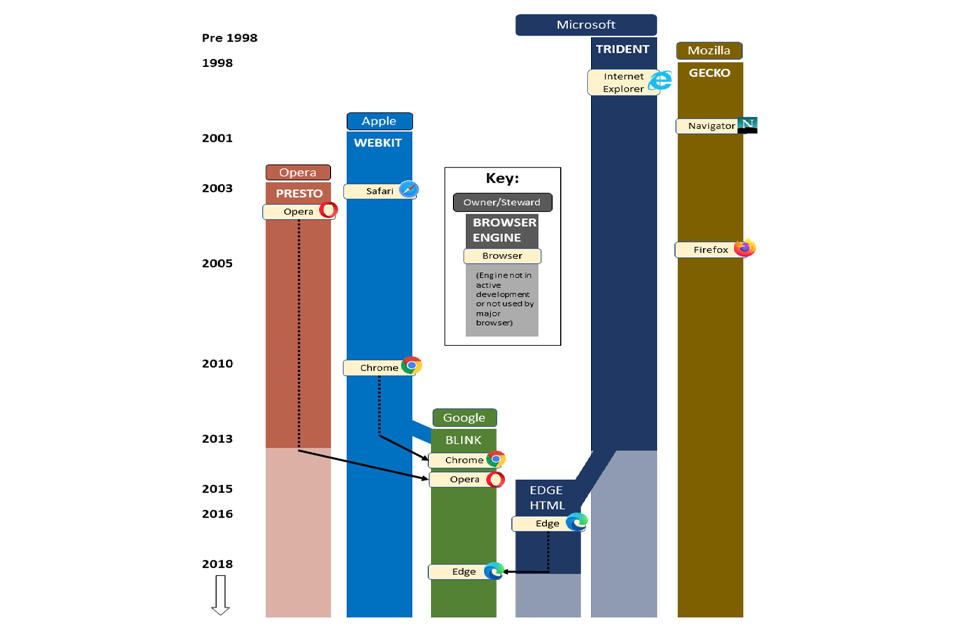

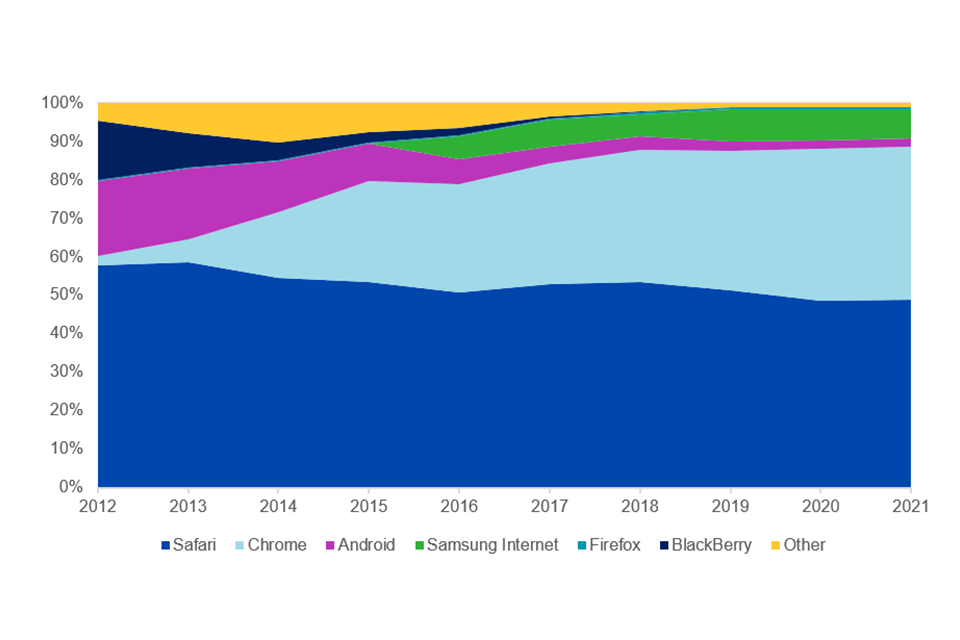

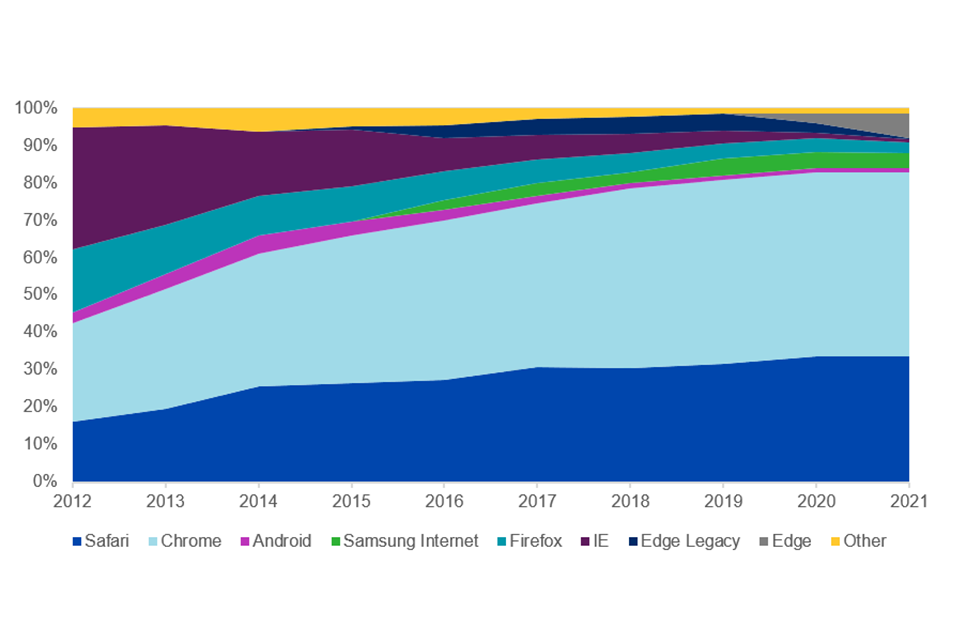

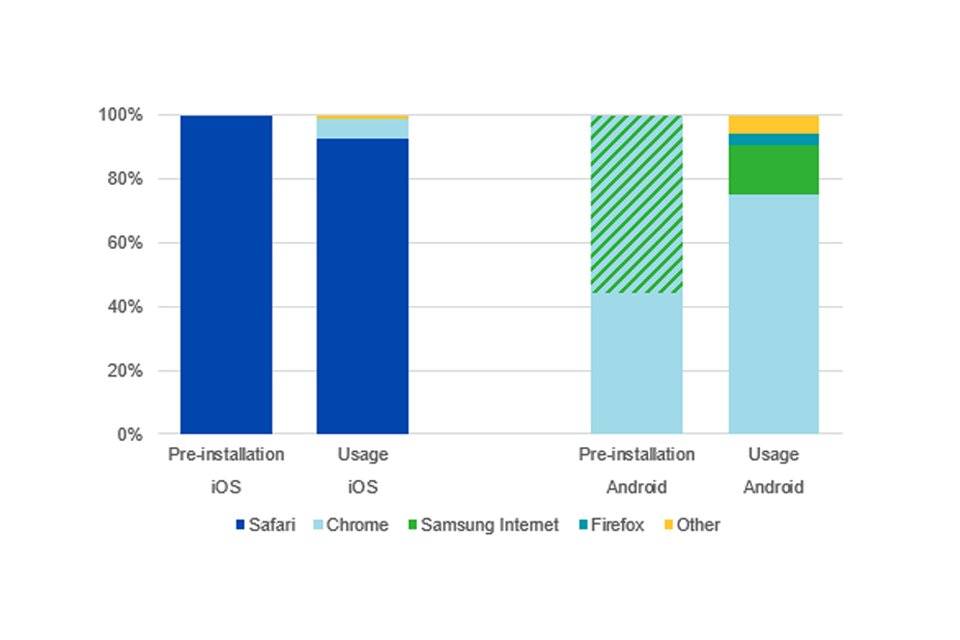

Apple’s browser, Safari (over 90%) and Google’s browser, Chrome (75%) have very strong shares of browser usage in their respective mobile ecosystems. There are just 3 browser engines: WebKit (provided by Apple); Blink (by Google); and Gecko (by Mozilla). All browsers on iOS have to use WebKit and most browsers on Android use Blink (the key exception being Firefox which uses Gecko), such that the position of both Apple and Google in browser engines is even stronger than in browsers.

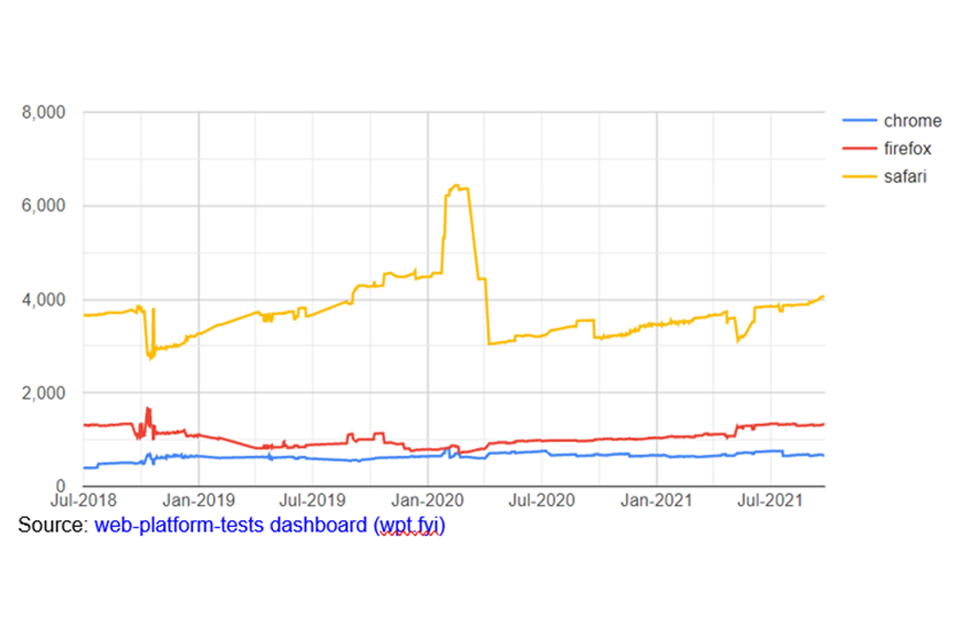

We have found that by requiring all browsers on iOS devices to use its WebKit browser engine, Apple controls and sets the boundaries of the quality and functionality of all browsers on iOS. It also limits the potential for rival browsers to differentiate themselves from Safari. For example, browsers are less able to accelerate the speed of page loading and cannot display videos in formats not supported by WebKit. Further, Apple does not provide rival browsers with the access to the same functionality and APIs that are available to Safari. Overall, this means that Safari does not face effective competition from other browsers on iOS devices.

The evidence also suggests that browsers on iOS offer less feature support than browsers built on other browser engines, in particular with respect to web apps. As a result, web apps are a less viable alternative to native apps from the App Store for delivering content on iOS devices. As noted above under Theme 2, the lower functionality for web apps on iOS means that developers are unlikely to be able to rely on web apps for iOS and this is likely to significantly increase development costs, as the efficiency saving from having to only develop one app (ie one web app as opposed to a native app for each operating system) is lost.

Both Apple and Google appear to influence user behaviour in other ways that serve to cement their market power in browsers. In particular, both Apple and Google use pre-installation, default settings and choice architecture to maximise use of their own browsers within their respective ecosystems. Although Google also displays browser choice screens on Android devices, the above shares of supply demonstrate that most Android users choose Chrome in practice. In addition, where users do exercise choice over their ‘default browser’, [footnote 30] these are overridden in certain contexts, such as when a browser is launched within a particular app.

This control over browser functionality also leads to concerns about Apple and Google being able to protect or expand market power in other activities – in particular, by Apple undermining the potential competitive constraints that face its App Store as a method of distributing apps to users; and by Google distorting competition in the market for the supply of ad inventory and in the market for the supply of ad tech services.

Theme 4: the role of Apple and Google in competition between app developers

Under this theme, we have examined the ways in which Apple’s and Google’s conduct as app store providers affects competition between app developers. This has included exploring concerns that Apple or Google could be using their position as operators of app stores to:

- give an advantage to their own apps and related services compared to those of competitors, in a way that may harm competition and consumers

- distort competition between third parties

- entrench their position of control over app distribution

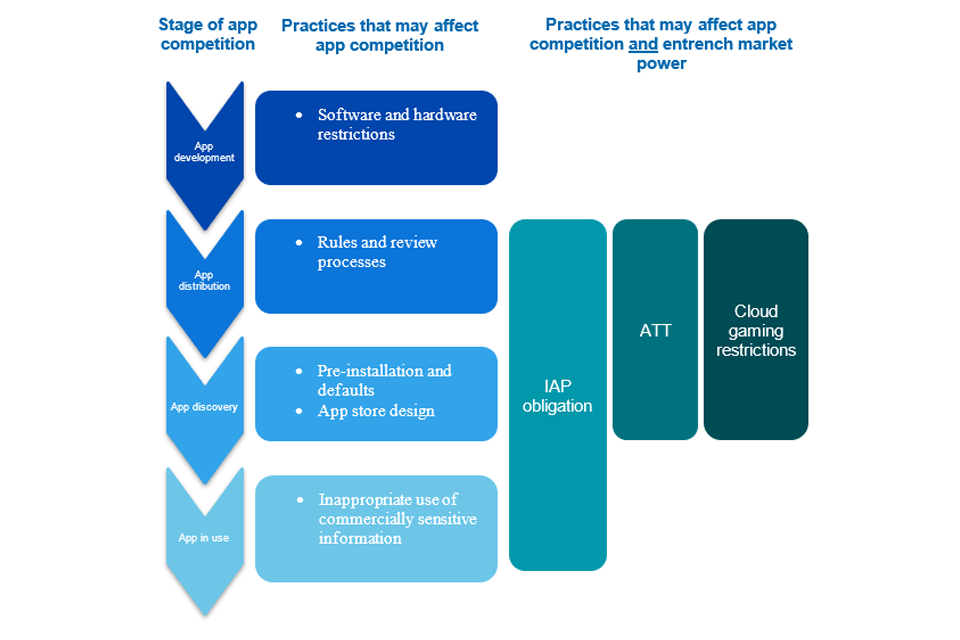

Apple and Google are able to use their control over their app stores, operating systems and (in Apple’s case) devices to set the ‘rules of the game’ for competition between app developers. This influence ranges from determining what features or business models app developers can implement, to shaping users’ choices about which apps to use. We have considered several ways in which this control could be harmful to competition:

-

there are a number of examples of hardware and software functionality on an iPhone that Apple does not allow other app developers to access, such as the technology that enables contactless payments. This could serve to preference Apple’s products and restrict innovation. Google appears to be less restrictive, in part because, given that the vast majority of Android devices are made by other companies rather than by Google, Google cannot control access to hardware to the same extent as Apple

-

app review processes can be opaque and rules can be inconsistently applied. Both Apple and Google have a wide discretion to reinterpret and change rules, and remove apps or block apps or app updates, where they consider that their rules are not being complied with. App developers have no choice but to make changes to their apps to meet Apple’s and Google’s requirements, while delays and uncertainty can add to development costs

-

the pre-installation of apps and setting certain apps as defaults (which Apple and to a lesser extent Google control in their respective ecosystems) can have significant impacts on user behaviour and give an advantage to Apple’s and Google’s own apps

-

the design of app stores and in particular the way in which search results are ranked can have a significant impact on which apps succeed. This creates the potential for Apple and Google to distort competition by giving an advantage in rankings to their own or certain third-party apps. It also means that changes to app store search algorithms may cause substantial disruption to app developers’ businesses, and we have heard concerns that these changes are made non-transparently and with a lack of notice

-

we have also heard particular concerns about Apple using commercially sensitive data or information about app developers that is obtained through operation of its app store, either to develop new products, or to otherwise gain a competitive advantage through its access to data about the financial performance of other apps. This may be facilitated by contractual terms that weaken developers’ intellectual property rights

Overall, we consider that there are various improvements that could be made put in place regarding the operation of app stores, including safeguards to ensure that Apple and Google are not able to give a competitive advantage to their own apps.

We have also considered 3 sets of specific practices which, as well as influencing competition in app markets, may have broader competitive implications, such as protecting market power in app distribution. These are: rules around payments for in-app purchases, Apple’s ‘App Tracking Transparency’ (‘ATT’) policy, and Apple’s restrictions on cloud gaming.

Both Apple and Google have rules around purchases of digital ‘in-app’ content, which require certain app developers with ‘digital’ apps to use only Apple’s or Google’s in-app payment system to process transactions; [footnote 31] and through which Apple and Google collect a commission of up to 30% for in-app payments for digital content. The payment rules also restrict the ability of app developers to inform consumers within an app of the ability to purchase in-app content (possibly at a cheaper price) elsewhere, such as on a website (often termed ’anti-steering provisions’). Apple and Google both say that that the obligation to use their payment systems is necessary for them to collect a commission on the sales that developers make as a result of distributing apps through their app stores.[footnote 32]

In addition to complaints about the level of commission payable, we have heard concerns that the use of Apple’s and Google’s payment systems makes it more difficult for users to switch devices (because they cannot manage subscriptions made through Apple or Google on their new device after they have switched to another operating system). These rules may also reinforce the market power of app stores as a way for users to discover and pay for content, as app developers cannot make any reference within an app to other payment options for accessing content on mobile devices (such as websites), which may be cheaper.

There are also concerns that in-app payment rules ‘disintermediate’ app developers from their users, because Apple and Google are the direct seller where purchases are made through their respective in app purchasing systems. The effect of this is to reduce the control that developers have over pricing and refunds, leading to complaints that app developers are less able to respond to users of their apps and worsening the consumer experience. Finally, in-app payment rules may also distort competition between apps that face these requirements and Apple’s and Google’s own apps (which are not subject to a commission).

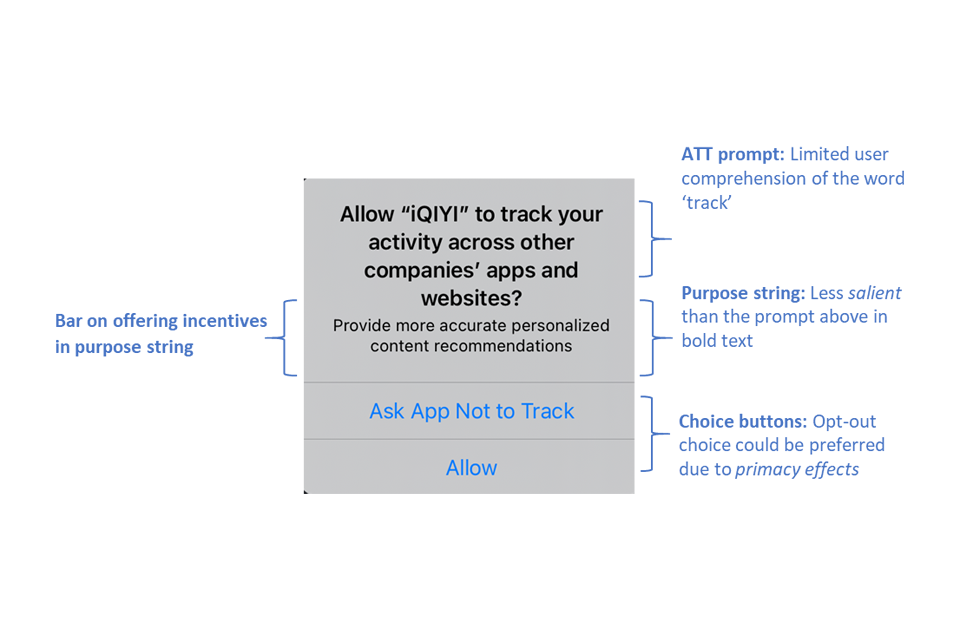

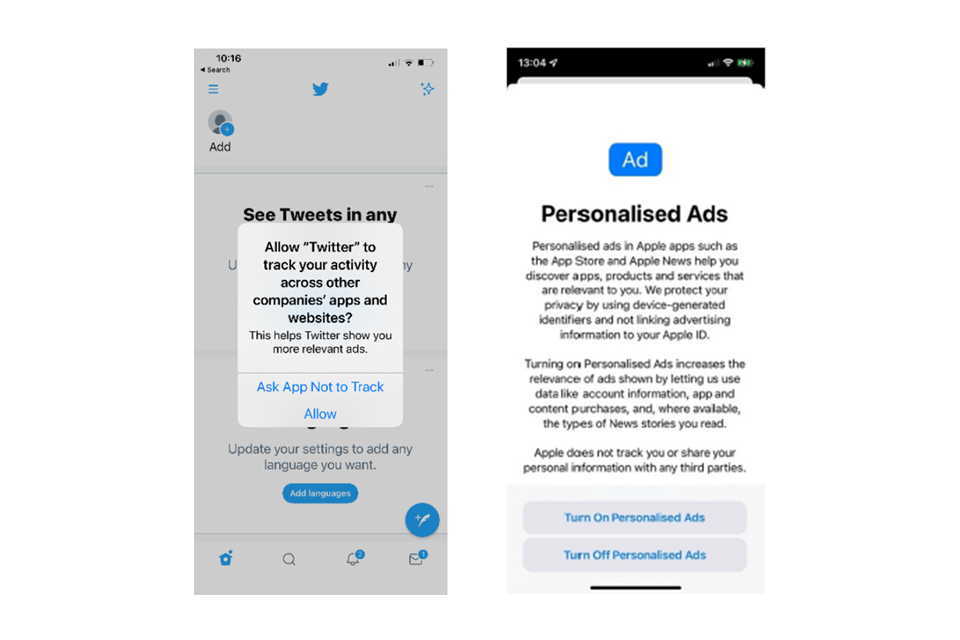

Two further issues relate only to Apple’s rules for apps made available through its App Store. The first is Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) policy, launched in April 2021, which Apple told us is intended to empower consumers by giving them greater transparency and ability to control the sharing of their own data. The change requires app developers to show a specific prompt to request users’ permission to collect certain data, in particular identifiers used to monitor users’ activity across apps.

We are supportive in principle of market developments that promote greater control and choice for consumers in a way that is competitively neutral, and ATT has the potential to deliver some consumer benefit in the form of enhanced privacy and user agency over the way that personal data is used for personalised advertising. However, we are concerned that Apple may not be applying the same standards to itself as to third parties, and the design and implementation of the ATT prompt to users may be distorting consumer choices. Ultimately this may mean that Apple is able to entrench the position of the App Store as the main way of users discovering apps, may give an advantage to Apple’s own digital advertising services, and could drive app developers to begin charging for previously free, ad-funded apps.

Second, through its control of the App Store, Apple has been able to block the emergence of cloud gaming on the App Store, which is currently permitted on Android. Cloud gaming is a potential threat to the model of accessing native apps through app stores, since it represents an alternative method of game discovery and distribution. Apple’s policy may also protect its competitive position in mobile devices and operating systems, as cloud gaming services may reduce the importance of high-quality hardware and make it easier for users to switch between platforms.

Initial views on ‘Strategic Market Status’ (SMS)

In its July consultation on a new pro-competition regime, described above, the government proposed that firms designated with SMS would be required to follow a legally enforceable code of conduct, which would manage the effects of market power by setting out how firms with SMS are expected to behave. The codes are intended to offer clarity to both users and firms designated with SMS, aiming to influence the latter’s behaviour in advance to prevent negative outcomes before they occur.

Building on the CMA’s advice through the Digital Markets Taskforce, the government’s consultation proposed that designation of SMS should require a finding that a firm has substantial, entrenched market power in at least one digital activity, providing the firm with a strategic position. There are essentially 3 components to this assessment, which are:

-

digital activities: the government has proposed that: (i) products, services and processes could be regarded as a single activity if they all can be described as having a similar function or, if in combination, can be described as fulfilling a specific function; (ii) such activities are to be considered ‘digital’ where digital technologies are a ‘core component’ of the products and services provided as part of that activity

-

substantial and entrenched market power: this arises when users of a firm’s product or service lack good alternatives to that product or service, and there is a limited threat of entry or expansion by other suppliers; further, such power is entrenched where it is expected to persist over time and is unlikely to be competed away in the short or medium-term

-

strategic position: a position is strategic where the effects of market power are likely to be particularly widespread or significant

Based on our assessment to date, in our view:

-

Apple would meet the government’s conditions (as currently proposed in its consultation, for possible SMS designation by the DMU) for each of the main activities within its mobile ecosystem, namely its iOS operating system and the devices on which it is installed, its app store, and its browser and browser engine

-

Google would meet such proposed conditions for possible SMS designation by the DMU for each of the main activities within its mobile ecosystems, namely the Google-compatible Android operating system, its app store, and its browser and browser engine

We have considered further below how the regime proposed in the government’s consultation, if implemented in that form, may apply to Apple and Google were the DMU to designate them with SMS status. First, however, we consider the potential interventions that could address the competition concerns identified in our study to date.

Initial views on potential interventions to address competition concerns

Overall, the CMA is of the preliminary view that a number of possible interventions may make positive differences to businesses that seek to offer products on Apple’s and Google’s platforms, and also to users of mobile devices.

We have given initial consideration to potential interventions that could contribute towards at least one of the following high-level objectives:

-

taking action to address the sources of market power, with a view to reducing barriers to competition or otherwise opening up markets to greater competition and choice

-

addressing harms to competition and consumers where market power is being exploited

At this stage, we have not reached any final views as to whether any particular interventions are warranted. Instead, we aim to assess in broad terms the relative merits of possible interventions, with a view to inviting stakeholders’ input on likely effectiveness of such interventions, in encouraging competition within and between mobile ecosystems, and if so whether the benefits to competition and choice they would deliver would outweigh any costs. For example, measures to allow greater choice within ecosystems may also create increased risks to device security or user privacy. Further, measures which reduce the extent of integration between the different products and services within mobile ecosystems could also worsen the user experience or erode consumer trust.

There may be complex trade-offs between these various considerations. We therefore encourage stakeholders responding to the consultation on this interim report to provide evidence both on the potential benefits to competition and choice they expect would result from the interventions described, and on any potential risks and costs (including how important such risks, such as risks to security or user experience, can be mitigated or managed).

Addressing the source of market power

The CMA has considered possible interventions that are directed at the ability of Apple and Google to exercise market power through measures that may increase competition or choice in operating systems, methods of app distribution on mobile devices and mobile browsers and browser engines.

First, we have considered interventions designed to allow third parties to carry out activities that are currently reserved for only Apple or Google within their ecosystems, which can harm mobile users by tying them into other services as a result of their choice of device, or certain policies or practices which mean that a substantial proportion of users are locked into Apple’s and Google’s related services. This could include measures such as:

-

removing barriers for other methods of installing apps on mobile devices, which could include allowing alternative or additional app stores, or allowing sideloading, under certain conditions

-

removing restrictions that are imposed by Apple and Google in relation to offering alternative payment options for in-app purchases for digital apps

-

changes to policies that currently reinforce the position of app stores as the primary method of accessing content or which disadvantage apps that are monetised in ways other than through in-app payments (for example Apple’s rules relating to cloud gaming and advertising prompts

-

greater choice of browser engines within mobile ecosystems; or a requirement to offer certain forms of functionality and interoperability to third-party browsers

The measures referred to above regarding browsers and browser engines may also lead to greater functionality being available for web apps and a more widespread uptake of this type of app on mobile devices. This could have the broader effect of reducing the barriers to entry for new operating systems, by breaking a link between operating systems and control over distribution of content through native apps which are accessed through Apple’s and Google’s app stores.

In allowing greater competition for these activities than currently exists, it may mean that Apple and Google need to provide additional information or functionality to third parties than they presently do. Therefore, the above measures may need to be combined with certain interoperability requirements, such as requiring that third parties are provided with the necessary APIs to be able to compete with Apple or Google’s own products or services. In particular, equitable interoperability would allow parties access on equal terms to others (including Apple’s and Google’s own products and services), effectively prohibiting self-preferencing and discrimination against third parties.[footnote 33]

We acknowledge concerns that such measures could give rise to increased security or privacy risks and that mobile ecosystems play an important role in protecting consumers from such risks, for example by checking apps do not contain malware and by limiting access and use personal data. If considering the case for any such interventions, we would therefore expect to consider also what conditions might be appropriate for Apple and Google to impose on third parties to address such risks.

As an example, Apple has told us that as a result of its requirement that all browsers on iOS be based on its own browser engine, WebKit, it is more readily able to fix any privacy and security concerns that arise in a timely manner, and reduce risks for users. We will be looking to test the effectiveness of alternative mechanisms to address such concerns, and will engage with stakeholders to develop our understanding of the effectiveness of different interventions. 76. We have also considered demand-side interventions that are focussed on making it easier for users to switch between devices that come with different operating systems. These measures are aimed at ensuring that many of the key features of mobile ecosystems that users value (for example data, apps, app content and subscriptions) can be easily transferred to and accessed on an alternative device.

Another possible barrier to competition in relation to mobile operating systems relates to the impact of Google’s placement and revenue sharing agreements associated with key products such as Chrome, Google Search and the Play Store. These agreements are conditional on manufacturers using a compatible version of Android and licensing a number of popular Google apps including the Play Store, Google Maps, YouTube, and Gmail as well as Google APIs or Google Play Services and, under a separate licence, Google Search and Chrome apps. These arrangements can harm the ability of suppliers of versions of Android that do not use Google’s products (such as ‘forked’ versions of Android) to attract device manufacturers, as other manufacturers are unlikely to be able to replicate the payments Google makes under these arrangements. We have therefore considered interventions which could involve ensuring that core features or functionalities are available within the open-source version of Android.

However, we are mindful that Google has previously invested significantly in the development of Android and continues to incur significant ongoing expenses associated with this operating system. Sharing the benefits of these investments with Google’s rivals could dampen Google’s incentive to invest and innovate in its platform. Further Google has told the CMA that there is a material risk that its apps would not run properly on such devices and that this would harm its reputation. We are therefore seeking to understand the impact of such interventions, and whether technical and compatibility issues could be overcome.

We also consider interventions which aim to make it easier for users to choose alternatives to Apple and Google, where such choice already exists within their mobile ecosystems. Currently Apple’s and Google’s ecosystems are heavily integrated and, even where there is in theory a choice, the large majority of users use the products that are typically pre-installed, prominently placed, and often set as a default on their device, including Apple’s and Google’s own browsers and Google’s Play Store. The design of choice architecture[footnote 34] and the approach to determining defaults is another key consideration of our study as we have found that this design can heavily influence consumer decision-making within mobile ecosystems, both in choice of apps and in other preferences, including the choices offered by Apple’s ATT prompt. We are therefore considering a range of potential interventions to prevent Apple and Google from benefiting unduly from these biases, which could include prompting consumers to make an active choice in setting a default for a key product and making it easier to exercise or alter such choices.

These interventions may be less likely to result in the kind of privacy or security risks associated with interoperability. However, to the extent that these markets will nevertheless remain heavily influenced by the power of defaults, a requirement to introduce alternative forms of choice architecture may on its own have a more limited effect on consumer behaviour. In addition whilst some forms of intervention on choice architecture can deliver benefits for users, such as making it easier for those users who wish to exercise choice, too many choice screens can also introduce burdens on consumers or ‘decision fatigue’ which will also affect the effectiveness of the intervention.

For this reason, some parties have called for direct interventions restricting the pre-installation of certain products as the default on mobile devices. Such measures would also require redesigning choice architecture to allow users to make a choice in the absence of a default or pre-installation. There may be a fine balance to be struck in ensuring that a choice screen for browsers is designed in a way – and presented at an appropriate frequency – to ensure the competition benefits outweigh the cost of introducing the mechanisms, and the possible frictions and burdens to users from being faced with choice screens too often. As part of responses to our consultation, we would welcome views on the proportionality of such measures.

Remedies aimed at addressing harms to competition and consumers where market power is being exploited

We have also given preliminary consideration to the merits of particular interventions which could protect against the effects of Apple’s and Google’s market power, in particular in relation to themes 3 and 4 above. This could include a range of interventions which are targeted at specific forms of conduct, such as:

-

requiring Apple and Google not to restrict unreasonably third-party access to hardware and software that is necessary to compete more equitably in browsers or app development. This would include through the design of Apple’s browser engine

-

requirements for Apple and Google to carry out a fair and transparent app review process

-

a requirement for Apple and Google to provide more transparency about their algorithms for ranking apps and in particular the factors that influence how apps are displayed on the app store. This may include a requirement to give reasonable notice of any material changes to the working of the algorithm, if that is likely to affect positioning of apps and therefore demand for app developers’ services

-

restrictions on Apple and Google sharing and using data or insights gained from the operation of their app stores or app review process in developing their own apps

-

a requirement for Apple and Google to allow alternative in-app payment options to be displayed alongside their own payment services within apps. This may necessitate Apple and Google finding other, potentially less restrictive, ways of charging a commission for the use of their app stores

-

a requirement that Apple and Google should remove from their rules the ‘anti-steering’ provisions that prevent developers from notifying users of alternative off-app payment options, and which further restrict app developers from offering a choice of payment systems to users

-

a requirement for the consistent treatment of own apps and third-party apps for privacy purposes

-

requiring an amendment to Apple’s policy on cloud gaming apps on iOS devices, so that cloud gaming service providers could offer apps which allowed users to stream multiple different games without these games each needing a separate listing on the App Store

What links these points is an objective of addressing the ability of Apple and Google to use their role in setting the ‘rules of the game’ for competition between app developers in a way which acts in their own interests or creates uncertainty or increases development costs for app developers.

We will assess these potential interventions in the second half of our study, including in particular a targeted assessment of arguments from Apple and Google as to why particular restrictions or rules for third-party apps are justified. As noted above, both Apple and Google have referred to privacy and security risks associated with allowing additional interoperability to the device, for example that allowing third parties access to the same APIs as first-party apps might give them access to personal data, or that allowing interoperability with aspects of hardware could cause risks to the user’s security. We welcome views and evidence on the benefits and costs of such interventions, whether the concerns raised by Apple and Google can be addressed as part of any interventions, and if so whether the costs of doing so would be proportionate to the benefits. 85. Given the broad spectrum of products and services within mobile ecosystems, we have also considered the role of separation remedies, as such interventions could help to prevent certain conflicts emerging and the leveraging of a market position from one area of market strength into a related activity.

In particular, we have considered the potential role for forms of separation in respect of Apple’s and Google’s own app development businesses, which compete actively with other app developers that rely on the mobile ecosystems. Options to implement this form of separation could include either data separation, specifically between data received through app store and app review processes and the teams responsible for app development; or operational separation, which would impose additional requirements to run app development operations independently from app store and review processes, and to ensure that Apple and Google offer comparable terms to other app developers that are available to their own apps and services.

The links between the different segments of mobile ecosystems have a number of implications for potential interventions. Some interventions will be most effective when designed in combination with others – for example, enabling greater choice for some areas within mobile ecosystems may also require some form of interoperability requirement. Taken together, the objective of such a package of remedies could be to lead to sufficient potential entry to address the market power that currently exists within mobile ecosystems. In contrast, some of the interventions outlined above could potentially be regarded as alternatives. As part of our further assessment of interventions, we will whether they may need to be implemented in combination to be effective, or whether the staggering of interventions is more appropriate, for example to allow time for testing whether any particular interventions have been effective in practice.

DMU powers

As discussed above, the government has recently consulted on proposals for a pro-competition regime for digital markets, which would include requiring firms designated with SMS status to follow codes of conduct that promote ‘fair trading, open choices and trust and transparency’. Based on the assessment in this interim report, we consider the framework currently under consultation could be an effective means of implementing the interventions we have considered in relation to those digital activities – operating systems (and devices for Apple); app stores and browsers and browser engines – in which Apple and Google appear in our view to meet the proposed criteria for possible designation with SMS.

Our preliminary view is that many of the potential interventions above would be consistent with the types of measures effected through codes of conduct, like those envisaged for the DMU by the government consultation. For example, that consultation envisages that codes of conduct would enable the following types of requirements:

- to trade on fair and reasonable contractual terms

- not to apply unduly discriminatory terms, conditions or policies to certain customers

- not to unreasonably restrict how customers can use platform services

- not to influence competitive processes or outcomes in a way that unduly self-preferences a platform’s own services, or services for which the platform derives a commercial benefit, over rival services, including through use of preferential access to data

- not to bundle or tie the provision of products or services in markets where the SMS platform has market power with other services in a way which has an adverse effect on users

- not to unreasonably restrict interoperability with third-party technologies where this would have an adverse effect on users

- to hold own apps/services accountable to the same privacy standards as are being imposed on third parties

- not to unreasonably restrict APIs or hardware in a way which has an adverse effect on users

The government has also proposed that the DMU should have powers to impose pro-competitive interventions (PCIs) to open up competition to the SMS platforms. PCIs would be targeted at the sources of market power, and would work alongside the code of conduct that is intended to address the adverse effects of market power. For example, PCIs could be appropriate where Apple and Google would need to introduce new functionality to be able to interoperate with third parties and to support competition within the mobile ecosystem.

In summary, our initial view is that if the government implements the framework broadly as currently envisaged, the framework for codes of conduct and PCIs envisaged in its consultation could be effective in addressing the types of concerns associated with exploitation of market power in the markets within the scope of this study, in addition to reducing market power for particular activities over time.

Decision on whether to make a market investigation reference

Where the CMA considers that there is a case for a more detailed examination of a market (or markets) it may refer the market(s) for an in-depth market investigation.[footnote 35] A market investigation seeks to determine whether features of the market(s) have an adverse effect on competition, and if so, the CMA decides what remedial action, if any, is appropriate to take using its order making powers, or recommends remedial actions for others to take.

Based on our initial findings, we believe there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that features of the following markets could be restricting or distorting competition in the UK:

-

mobile operating systems, with a focus on the closed nature of Apple’s ecosystem, and on the nature of Google’s licensing agreements with device manufacturers

-

app stores and app distribution, with a focus on addressing the sources of Apple’s and Google’s market power in native app distribution within their respective ecosystems

-

browsers and browser engines, with a focus on Apple’s WebKit restriction and other barriers to competition such as pre-installation, default settings and choice architecture

The CMA nevertheless has a discretion whether or not to make a market investigation reference, and one of the factors taken into account when exercising this discretion is whether it is the most appropriate mechanism for assessing the issues and delivering the required outcomes. 95. We also take into account any stakeholder representations encouraging us to make a market investigation reference. Since issuing our market study notice on 15 June 2021, we have not received any such requests in response to our statement of scope or in our subsequent engagement with stakeholders.

Our current assessment is that the DMU – through a combination of the anticipated enforceable codes of conduct and pro-competitive interventions – will in principle be best placed to tackle the competition concerns identified by this market study to date. In particular, this is because the interconnected nature of the activities carried out by Apple and Google within their ecosystems is likely to necessitate a package of interventions aimed at assessing potential harms to competition from a number of different angles, which in some cases potentially requires iterative design, testing, and trialling.

On this basis, the CMA has decided not to make a market investigation reference. Notwithstanding this, the CMA will continue to keep under review the potential use of all its available tools during and following the second half of the market study, taking into account any relevant market or legislative developments that may arise. This includes the possibility of making a market investigation reference at a later point in time or taking enforcement action under our competition or consumer powers.[footnote 36]

Next steps

This interim report provides an update on the progress we have made to date in this market study. It sets out our initial findings on a wide range of potential concerns within each of our 4 themes and identifies the range of potential interventions we are considering in order to address them. We welcome responses by 7 February.

In the second half of the study, we intend to gather more evidence to test and refine our thinking in relation to the competition concerns outlined above. In particular, we will be undertaking more comprehensive quantitative analysis of various market dynamics and gathering further evidence on the existence or otherwise of trade-offs between competition, security, and privacy in the context of mobile ecosystems.

We will set out conclusions and recommendations for interventions in our final report, which we will publish by 14 June 2022.

1. Introduction

Context

On 15 June 2021, the CMA launched a market study into mobile ecosystems,[footnote 37] setting out its intention to gain a better understanding of a major component of the digital economy, and to gather evidence to inform an assessment of whether competition is working well for consumers and citizens in the UK.

The study was deliberately scoped broadly, both to enable us to investigate the wide range of concerns and potential issues that have been brought to our attention in these related markets; and to provide us with a holistic perspective of how each of the components of mobile ecosystems interrelate, and how differing business models in this sector can drive incentives and behaviour.

As set out in our statement of scope, the conclusions we reach in this market study will also contribute towards a broader programme of work, which includes the proposed establishment of a new pro-competition regulatory regime for digital markets, and our active competition and consumer enforcement work. This is consistent with the CMA’s Digital Markets Strategy, refreshed in February 2021,[footnote 38] which emphasises that a key objective across our work in digital markets is to support the establishment of the Digital Markets Unit (DMU) within the CMA to oversee a new pro-competition regulatory regime. In establishing the DMU, we hope to deliver a step-change in the regulation and oversight of competition in digital markets and in turn drive dynamic innovation.

In July 2021, the government launched a consultation on its proposals for the new pro-competition regime, which are intended to drive greater dynamism in the UK tech sector, empower consumers, and drive growth across the economy.[footnote 39] The government’s proposals build on the recommendations by the Digital Competition Expert Panel, chaired by Professor Jason Furman,[footnote 40] and are informed by subsequent findings and recommendations from the CMA’s market study into online platforms and digital advertising,[footnote 41] and the advice of the Digital Markets Taskforce.[footnote 42]

Evidence Gathering

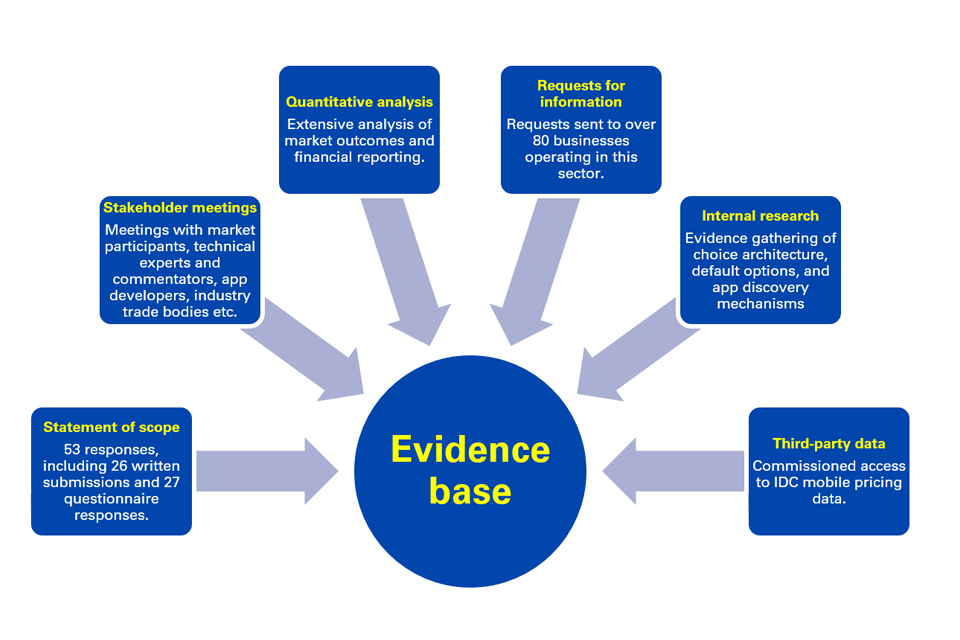

We have consulted a large number of parties throughout the last 6 months, which has enabled us to gather a broad range of evidence that reflects a diverse set of perspectives. This has involved a high volume of submissions from parties, in response to our statement of scope, an online questionnaire for app developers, and our formal requests for information. We are grateful to all those parties who have engaged with our work and enabled us to make substantial progress in the first half of our market study. Figure 1.1 summarises our progress to date in gathering evidence.

Figure 1.1: Overview of our evidence sources

Diagram providing an overview of CMA’s evidence sources: written responses to our Statement of Scope (53 responses, including 26 written submissions and 27 questionnaire responses.); stakeholder meetings (meetings with market participants, technical experts and commentators, app developers, industry trade bodies etc.); quantitative analysis (extensive analysis of market outcomes and financial reporting); requests for information (Requests sent to over 80 businesses operating in this sector); internal research (evidence gathering of choice architecture, default options, and app discovery mechanisms) and Third-party data (commisioned access to IDC mobile pricing data).

A summary of the responses to our statement of scope can be found in Appendix B.

The purpose of this interim report

Published half-way through our market study, the purpose of this interim report is to provide an update on our approach and our progress, to indicate the direction of travel our analysis is taking in relation both to concerns and potential interventions to address them, and to test these initial findings with stakeholders.

This interim report sets out our understanding of how the companies and markets within our scope function. We do this at a high level in Overview of mobile ecosystems, which provides an overview of mobile ecosystems in the UK and why they are so important, highlighting the key similarities and differences between the business models of Apple and Google, and setting out some descriptive statistics regarding various market outcomes.

The chapters that follow then provide a more focused and detailed description and assessment of competition within each of the major components of mobile ecosystems. In Competition in the supply of mobile devices and operating systems explains our analysis and findings regarding competition in the supply of mobile devices and operating systems, while in Competition in the distribution of native apps and in Competition in the supply of mobile browsers do the same for mobile app distribution and mobile browsers respectively. The role of Apple and Google in competition between app developers then sets out our findings on the role that Apple and Google play in competition between app developers.

Where there are elements of our work that are more complex or technical, or where our assessment is supported by a large volume of evidence, such as in relation to Google’s contractual agreements with device manufacturers and app developers,[footnote 43] we have sought to provide additional detail in supporting appendices.