Making Every Contact Count: evaluation guide for MECC programmes

Updated 4 March 2020

About this guide

Jointly published by Public Health England and Health Education England (HEE) in conjunction with London South Bank University. This guide is part of the Making Every Contact Count practical resources

Public Health England (PHE) lead: Mandy Harling. HEE lead: Lara Hogan. London South Bank University leads: Jane Wills, Susie Sykes and Viv Speller, from a learning set funded by the Academy of Public Health for London and South East. This guide replaces and supersedes previous MECC Evaluation Framework published on GOV.UK from PHE and HEE that was based on work delivered within Kent, Surrey and Sussex.

PHE - NHS - London South Bank University

Introduction

MECC is an established national initiative in which public-facing workers are encouraged to make contact with patients, service users or the public as an opportunity to support, encourage or enable them to consider health behaviour changes such as stopping smoking or improving their sense of wellbeing. This may involve initiating a very brief intervention referred to as a VBI – that takes place in less than two minutes – with a person perhaps as part of a routine appointment or consultation; and where appropriate, offering advice, raising awareness of risks, providing encouragement and support for change or signposting and referring them to local services and sources of further information.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance[footnote 1] states that a VBI is intended to motivate change which may be evidenced by individual outcomes of:

- the making of a plan

- the setting of goals

- an expressed intention to use services, or having the knowledge of how to use them

- the appropriate use of a service to support a behaviour change

This guide has been developed as a practical resource to support practitioners, co-ordinators and commissioners who are about to undertake an evaluation of a MECC programme. To plan an evaluation, it is necessary to:

- determine the aims and objectives of the MECC programme and what the outcomes might be, and their attribution to MECC

- understand what evidence there is about what works to achieve those outcomes

- explore the links between MECC activities and the outcomes by describing and mapping a logic model

- develop an evaluation plan to measure progress and achievements, using either quantitative and or qualitative data

This guide is structured to help the reader step by step towards developing an evaluation for MECC. This includes advice on how to identify appropriate indicators or success measures, questions to explore when evaluating programmes, and what factors to consider when selecting methods to collect data. The guide was piloted in an action learning set across London and the South East during 2018 and the advice and feedback from practitioners is reflected within the content and also under the sections labelled ‘practitioner voice’.

Evaluation is the systematic collection of information about the activities, characteristics and results of a programme or intervention in order to make judgements about the programme’s effectiveness and benefits and inform decisions about future commissioning. This guide should be read alongside the MECC implementation guide which encourages organisations to reflect and review their readiness to implement MECC.

Step 1: Plan the evaluation and involve stakeholders

Planning for the evaluation of a MECC programme is integral to the planning of the programme itself and should take place at the outset. You should:

- design your programme with evaluation in mind

- collect data from the very start, and on an ongoing basis

- use this data to continuously improve what you are doing

It is not necessary to have an external evaluation. Although you might not have prior experience in evaluation, taking time to decide how you will evaluate your programme will be worthwhile and does not have to be complicated. Evaluations do involve planning and monitoring meetings, collecting and analysing data amongst other activity, so it is important to identify who will undertake each task, when this will take place, and how much of their time is needed.

This process of planning will also help in clarifying the business case for MECC and its expected benefits for the local population, the organisation and for staff where this is being delivered. Involving stakeholders at the outset will help ensure that they have a realistic understanding of what the evaluation can demonstrate. These stakeholders may include both those funding, developing or delivering MECC. Evaluation also needs to be timely and aligned to when the organisation makes decisions or allocates resources.

Practitioner voice

‘Involve your stakeholders at an early stage in the evaluation because otherwise you may find that they may expect different outcomes or are over-ambitious for the programme.’

An evaluation needs to answer:

- how effectively local MECC programmes have been in achieving their aims and delivering the intended changes

- what difference the MECC programme has made and to whom

- what factors have enabled or inhibited implementation of a MECC programme

- whether MECC interventions are delivered in the ways they are intended (fidelity of the approach)

- if the programme is delivering value for money

Step 2: Identify the existing evidence base

A key element when making the case for investment in an intervention or programme is to examine the existing evidence base on whether it is effective. It is recognised that there is limited published formal research on MECC itself, with most of the evidence being from within policy papers or local evaluations of training programmes for example the review by University of Southampton on the Wessex MECC training[footnote 2]. There is good evidence for the cost effectiveness of brief interventions for alcohol and smoking[footnote 3], but this is not explicitly tied to the application of the MECC approach of very brief advice to other behavioural risk factors such as physical activity, to weight management or mental wellbeing.

This published evidence was also mostly generated in relation to smoking cessation or alcohol interventions delivered within primary care settings. Where evidence is said to exist to support MECC programmes such as in the Health Strategy for Ireland (2016)[footnote 4] [footnote 5] [footnote 6], it should be noted that there can be a variety of definitions of ‘brief’. In the Strategy for Ireland, the delivery evaluated is of MECC brief interventions, rather than very brief interventions or VBIs – that is those that can be delivered in under two minutes, which increasingly feature in a MECC approach. There are several published local evaluations such as those from Wessex and Milton Keynes, but the focus of these has often been the impact of training on workforce confidence and capability to engage in MECC interventions.

There is one rapid review of the evidence for Wirral[footnote 7] and another for Yorkshire and the Humber[footnote 8] although these are narrative overviews rather than research evidence reviews. A scoping review of evidence undertaken in 2018[footnote 9] concluded that there is no discrete or stand-alone evidence base for MECC itself, although MECC does include the delivery of brief interventions which are known to be effective and for which there is a supporting literature identifying many key features of good practice in their implementation.

Step 3: Identify your expected outcomes

A scoping exercise with stakeholders between 2014 and 2018 revealed a range of aims for the delivery of MECC programmes. These ambitions can be categorised as:

a) MECC contributes to a cultural change of embedding prevention into organisational policy and strategy

b) the adoption of MECC enables wider workforces to see prevention as part of their role

c) MECC training increases the capability of workforces to undertake healthy conversations as part of their everyday practice

d) MECC motivates and prompts staff to adopt positive health behaviour changes

e) MECC brief interventions promote population health behaviour change

Many of these ambitions are also reflected in the benefits of MECC outlined by Health Education England[footnote 10]. Within any one MECC programme there might be a number of these different ambitions, but in order for services to plan and evaluate MECC it would be necessary to start to unpack the different aims for a service, and to examine them more closely. Each of these ambitions such as the examples in the list under Step 3 above, reflects a change, but being able to measure them for example knowing what has increased or decreased, improved or reduced, and then evaluate the long-term impact from this, may have its challenges.

Outcomes measure the changes or differences that are expected as a result of the MECC programme being delivered. Using a framework approach can support staff and organisations in the delivery of MECC and also enable a common approach to delivery[footnote 11]. Table 1 is a possible outcomes framework for MECC using each of the ambitions detailed above as a separate domain, with a number of possible indicators then identified. It should be stressed that this is not a template and local considerations will influence the choice of indicators that are adopted.

Table 1: Outcomes Framework for MECC

| Organisational Culture | Extent that prevention is embedded within the organisation | • leadership: buy-in demonstrated for example by managers taking part in MECC training; MECC presentations to managers/Board • MECC on the agenda of team meetings • awareness of MECC amongst staff: MECC publicity in bulletins; MECC workshops • a local MECC brand • MECC written into organisational policies • MECC written into annual reports • having a designated MECC champion • MECC being part of induction and/or mandatory training • MECC principles in job descriptions and personal development plans/workforce appraisal systems • health and social care professionals can deliver a healthy conversation (brief or very brief intervention) • MECC incorporated into relevant service pathways • all public service sites are able to support opportunities for a healthy conversation, for example a suitable room or space for one-to- one conversation, or access to internet for information on sources of local support/referral |

| Prevention as part of all roles | A shift in recognition for staff (outside of health improvement) of their contribution to preventing ill-health | • the number of healthy conversations (incl. topic discussed) and where these took place , for example outpatients clinic, community service, housing office • the number of referrals and signposting undertaken and the setting where these took place • the use of evidence and information from robust sources, for example All Our Health or MECC |

| Staff knowledge and skills | The capability of staff to engage people in and conduct ‘healthy conversations’, also known as VBIs | • the number of training sessions delivered, and which staff groups took part in these • reported levels of workforce satisfaction and confidence following training • number of staff completing training who are then delivering VBIs • refresher courses are made available and follow up conducted on how training is put into practice • use of a consistent training model developed using MECC training quality markers ˄ • all relevant health and social care professionals have achieved level 1 of MECC competence (possibly through e-learning) and a proportion achieve level 2 competence † |

| Improvement in staff health and wellbeing | Impact on workforce wellbeing from the MECC approach to address behavioural risk factors ‡ | • development of staff wellbeing and health initiatives • staff uptake of services to support behaviour change • staff sickness absence rates • reported staff behavioural risk factor changes, such as stopping smoking, or starting an exercise activity or joining a wellbeing group |

| Population health improvement | Reduction in behavioural risk factors | • reported behaviour change by individuals or reported contemplation of making change/or planning for change • reported satisfaction from individuals who have been engaged in a MECC intervention • uptake of services enabling behaviour change, for example smoking cessation, weight management • longer term reduction in behavioural risk factors, for example reduced levels of smoking, obesity, or alcohol consumption at increasing or higher risk levels, amongst the population the programme serves |

˄ How, S. and Smith, N. (2018). Making Every Contact Count (MECC): quality marker checklist for training resources Public Health England, Health Education England.

† Health Education England – Wessex (n.d.). Making Every Contact Count: Implementation Toolkit

Practitioner voice

‘Be clear about the ambitions for your MECC programme. Our stakeholders wanted it to achieve all of the ambitions. Identifying the specific changes for Ambition E was the most challenging. Our stakeholders expected to see health improvements such as a reduction in risk factors such as smoking and cost savings from reduced demand on services. We were able to explain at the outset that these are high level outcomes which would be difficult to evidence and attribute to MECC.

We learned that having a robust evaluation plan to measure the effects that the MECC programme is demonstrably having on shorter term outcomes helped us to defend the effectiveness of our activities and make the case for investment in MECC.’

Outcomes over time

As highlighted above, it can take time for the benefits from the delivery of brief interventions to become visible within a population. Many conditions such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease will develop over a number of years, often with very few external indicators for the individual. MECC VBIs can help increase the number of individuals who will go on to stop smoking, reduce their alcohol intake or begin to increase their physical activity levels, all of which are proven to positively contribute to reducing the prevalence of conditions such as cancers, diabetes and cardiovascular disease amongst a population – but it should be noted that it can take time to begin to see this change at a population level.

Another factor to be aware of when planning an evaluation as highlighted in the practitioner voice quote above, is the challenge of tracking back, of identifying the causal factor that led to an outcome, such as a person stopping smoking. This can be challenging as programmes are often delivered alongside other activities and national wellbeing campaigns, all of which could also have contributed to a person then embarking on a behaviour change. This is covered in more detail below.

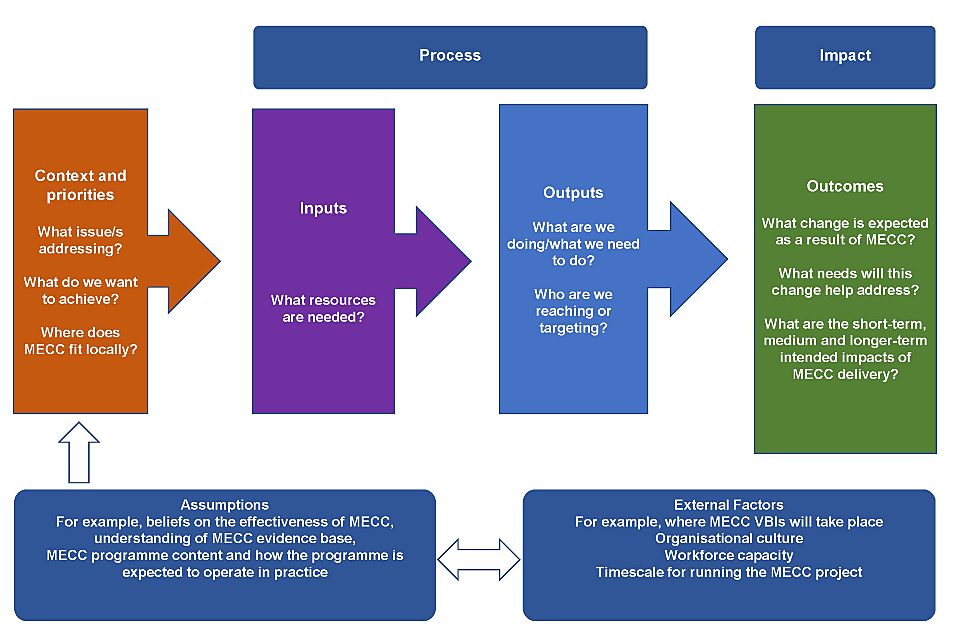

Step 4: Use a logic model to plan delivery to help achieve the expected outcomes

One of the most useful tools for deciding how to evaluate programmes is a logic model. This is a diagram that summarises your expected change model – in other words, what changes that you will deliver to achieve your programme’s desired objectives. For example, if someone accesses a weight management service, or quits smoking following a VBI. NICE (2014) states that a logic model can help to provide: “…narrative or visual depictions of real-life processes leading to a desired result. Using a logic model as a planning tool allows precise communication about the purposes of a project or intervention, its components and the sequence of activities needed to achieve a given goal. It also helps to set out the evaluation priorities right from the beginning of the process.”

The HM Treasury Magenta Book sets the ‘industry standard’ for logic modelling in evaluation and provides useful guidance on how to develop and use a logic model[footnote 12].

A logic model helps make explicit the programme theory underpinning a programme that explains how MECC works and specifies how its activities or components will contribute to a chain of effects that bring about its intended or actual impact and outcomes. A logic model can also highlight other factors that may influence the impact that an intervention has, such as context and the potential impact from other initiatives that are being implemented concurrently – these other initiatives can be referred to as confounders.

Figure 1: Components of a logic model

Figure 1 Logic model diagram

Practitioner voice

‘I had never seen a logic model but developing one was the biggest ‘light-bulb’ moment. It helped me to question a whole load of assumptions I was making that, for example, if staff are more confident they are more likely to have a healthy conversation each day and that would lead to widespread lifestyle changes. I was much more confident in articulating the logic behind the relationship of each component activity with the longer-term outcomes and whether or not there exists an evidence base.’

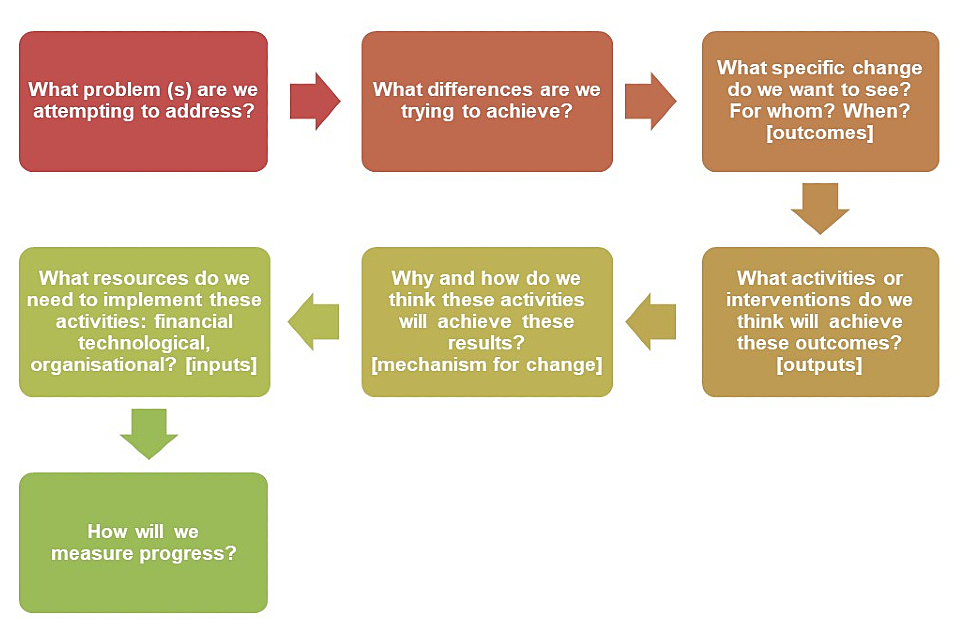

Logic model process

The figure below outlines the steps in the planning process. In essence a logic model helps you to plan by describing:

- what the need is that you are attempting to address

- what you will need in order to intervene (inputs)

- what that resource will deliver (outputs) in terms of activities and participants reached for envisaged short, medium, and longer-term outcomes

Using an approach known as ‘backcasting’ will help you to first identify the possible outcomes from your programme, arranging them from short term outcomes to those with longer term impact. Taking this approach will then help you to work backwards to identify the outputs and activities required to help your programme to achieve those outcomes.

Figure 2: Process for developing a logic model for MECC

Figure 2 Process for developing a logic model

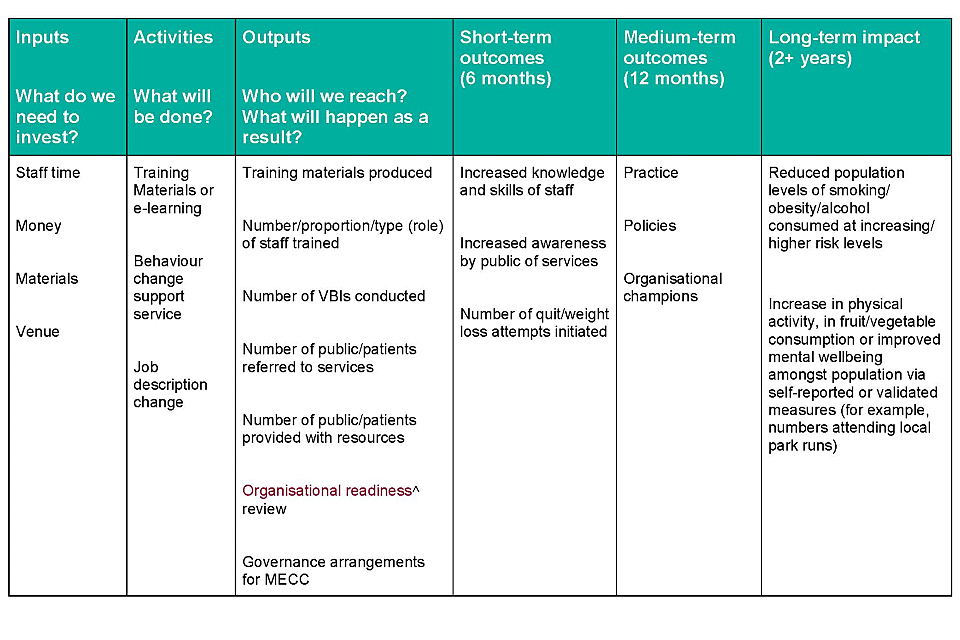

Developing a logic model

There is no consistent template for a logic model, as it will need to be developed following discussion and input from relevant leads for a programme. A simplified logic model for MECC might look like the one in Table 2 below. Further information on logic models can also be found in the resources section below.

Table 2: An example Logic Model for MECC

Table 2 Example Logic Model for MECC

˄ Organisational readiness review.

Practitioner voice

‘By using a logic model, we were able to see that our proposed activities wouldn’t really deliver our desired outcomes. The outcomes themselves were too ambitious and not specific. By understanding how to bring about the short-term changes we could identify a much more realistic programme and then select a set of measures and indicators.’

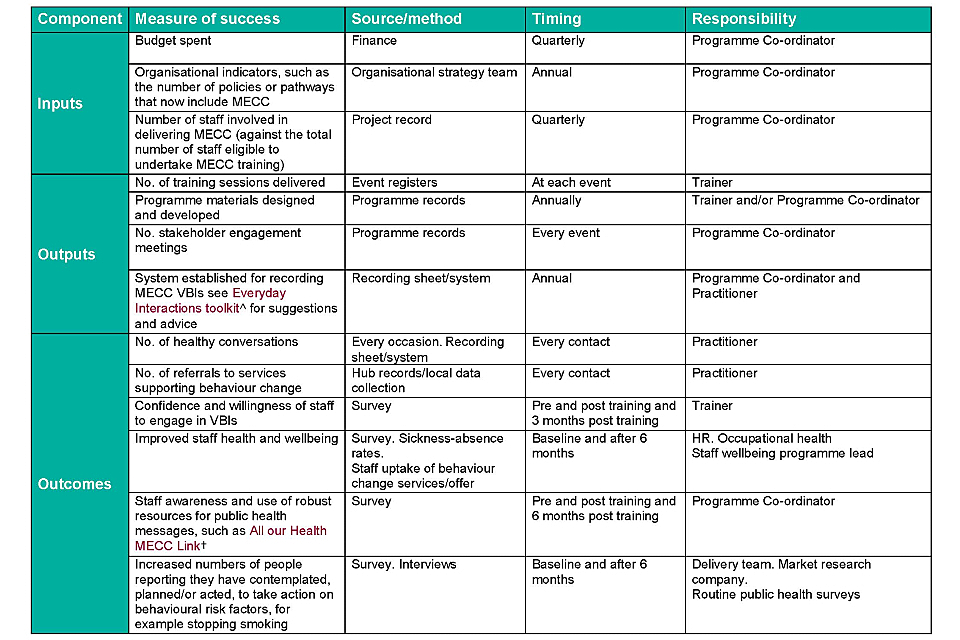

Step 5: Select a set of measures

The framework in Table 1 (in step 3 above) can provide a starting point, identifying a list of possible indicators for each domain or ambition for MECC. When planning an evaluation, each domain will require different data sources and you will need to consider how such data will be collected, when this collection will take place and by whom. Each MECC programme will likely have different services involved and different types and levels of local infrastructure, for example, whether there is a local single point of access or hub for local people to access services. This means evaluation data collected will vary from area to area.

By identifying relevant indicators for your programme and tracking them from the start, you will be able to compare progress and impact from programme delivery against the baseline or initial programme starting point for your area.

Effective indicators will often be based on up-to-date sources of information for example BMI or smoking status recorded within antenatal services. The key is to identify those which are collected routinely, are feasible for collection and are accurate, and longitudinal (enabling population change and trends to be tracked over time).

When considering evaluation indicators:

- identify measures that can be monitored routinely such as numbers attending training or changes to job descriptions, and those for which data collection will need to be planned for such as staff satisfaction surveys, or the views of senior managers

- consider the feasibility when you select programme evaluation measures – thinking about what can be attributed to impact on your local population. The nature of MECC as a VBI is that individuals won’t necessarily know or remember that they have had a specific conversation, and the resulting cumulative impact of several VBI conversations over time – helping to reinforce a wellbeing message that may be effective for an individual.

- the Everyday Interactions Toolkit developed by the Royal Society for Public Health and Public Health England, may be useful when considering data collection on VBIs conducted by practitioners

- track both short term outcomes and longer-term impact but be careful to manage expectations of what your programme can realistically deliver

- identify who is going to be responsible for collecting the data

- while quantitative data such as indications of trends in the local population can be persuasive, so too are case studies and testimonies – gathering feedback from different stakeholders can help in building a fuller picture, including insights on engaging harder to reach groups and current non-beneficiaries of the programme

An indicators framework may begin to look like the condensed example below.

Table 3: Example of an Indicators Framework for MECC

Table 3 Example Indicators Framework

˄ Everyday Interactions toolkit.

† All our Health and MECC link

Practitioner voice

‘I think it’s a very positive programme – a simple and effective way for members of an organisation, especially in local government and charities, to think about health and prevention even where it may not achieve what it purports to, with the challenges of isolating health behaviour changes, it does still do other things. It’s part of a multi-pronged approach, not a single intervention.’

Step 6: Develop an evaluation framework or protocol

The following questions could be useful to guide you when developing an evaluation protocol. This will involve you initially describing the scope of the evaluation, and then detailing what methods are to be used, the expected outcomes and impact of the MECC programme, as well as those factors that may enable or inhibit the outcomes being achieved and whether the programme could be a good return on investment. It is likely that the evaluation will include 3 elements:

-

Outcome evaluation

-

Process evaluation

-

Identifying if the programme is delivering value for money

You will need to consider who will receive the evaluation report and include the senior responsible officer in the planning. If you view MECC as part of the organisation’s commitment to prevention and public health, then you may wish it to be presented to your organisation’s modernisation or transformation body. Dissemination may be a single report or presentation, but you could make it part of a much wider MECC programme strategy. An example of this approach is available from Surrey Heartlands.

Table 4. Suggested evaluation framework for MECC

| Manage | • Who are the stakeholders • What do they want • How will you find |

| Define and Frame | • What is the purpose of the evaluation • What important 3 to 5 questions are needed |

| Describe | • What quantitative data needs to be collected; by whom, when, how • What qualitative data needs to be collected; by whom, when, how • How will you identify if the programme is delivering value for money • How will you assess the quality of the programme • How can impact be assessed across population groups, and progress on addressing health inequalities |

| Understand outcomes | • Are there elements of your programme that are unique or distinctive • What aspects of local context might influence outcomes • What are the delivery challenges and barriers; How do you address these • What are the main enablers to delivery, and how can you build on them • Has the programme had the expected level of uptake? for example, of training. If not, why is this, and what can be done to address this issue • Are there any particular population groups that are over or under represented in delivery data for the programme; What can be done to address this • Does the programme provide value for money • Could anything be done differently to increase reach or outcomes • What impact has the programme had on staff or public or patients or the organisation • How will you approach the tracking of evidence, to help identify and attribute the impact of interventions back to the MECC programme |

| Synthesis and presentation | • How will the evaluation report be structured • To whom will it be |

Step 7: Making the case for MECC

A successful case for an MECC programme will depend on clarity of:

- a vision and articulated benefits that sit with current priorities – for example for population health and public health impact, staff confidence and morale

- the existing evidence base, and demonstration of which elements of MECC are comparable to other examples of interventions that have a relevant existing business case

- identifying the objectives to be achieved through developing a logic model will help you set out what activities the programme will deliver to have the intended impact

- the costs of delivery and the value for money expected, for example the financial and social return on investment such as reduced sickness-absence and staff retention

- the planned evaluation of the programme delivery and the indicators that will be used, making clear that it can take time to see impact

- population wellbeing benefits such as those identified by Derbyshire Fire and Rescue Service

Derbyshire Fire and Rescue Service

With a limited amount of published formal research on MECC, the case for investing in a MECC programme has frequently been based on its potential, for example via elements of policy papers or local evaluations of training programmes, plus the more robust randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence on efficacy of brief interventions for smoking cessation and alcohol. As part of this, some have cited a reference from an early East Midlands MECC implementation guide and the principle that if every frontline staff member engages in ten healthy conversations per year, based on the size of the health and social care workforce, this could generate up to 2.88 million new opportunities for health improvement annually (based on the scale of workforce and the number of contacts they will have with members of the public). It was estimated that if a proportion of these brief interventions – cited as 1:20 of those conversations conducted – resulted in a behaviour change, then around 144,000 individuals could be improving their health in a given year.

With a large number of daily contacts with the public, there is potential for the health and care workforce to help enable positive behaviour change and in turn reduce risk factors. Your local MECC programme evaluation could help throw further light onto this, by potentially providing evidence for the likely impact of MECC on population health risk factors.

Practitioner voice

‘It was always that we should ‘do prevention’ and there was a political will but this (MECC Evaluation training programme) has really helped the business case. It is important to articulate the challenges and be clear about what we know and what we don’t know.’

Learning and conclusion

The vital factors from practitioners evaluating MECC programmes are to:

-

Consult stakeholders early on, build understanding from their perspectives and also identify how MECC sits with organisational priorities.

-

Be clear (and realistic) about what MECC is going to achieve.

-

Establish a baseline or alternative for comparison of programme impact.

-

Develop ways of measuring and valuing outcomes.

-

Identify key performance indicators.

-

Identify not just the financial costs incurred in implementing MECC but also the social return on investment, value for money and benefits generated from the programme.

Resources

Making Every Contact Count has many useful resources that can help inform your evaluation planning, for example:

- MECC implementation guide[footnote 13] can help organisations when assessing their current position on MECC delivery, helping to identify any areas for further input or improvement – it can also act as an implementation checklist and can help form the basis of a local action plan when used together with the evaluation framework

- case studies[footnote 14] contain examples of local evaluations conducted from across the NHS, voluntary sector and local authorities

- ‘All our Health’ is a framework of evidence about public health issues that can form part of training programmes for MECC[footnote 15]

Useful resources when planning an evaluation:

Public Health England (2018): Planning an evaluation

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2011): [Developing an effective evaluation plan] (https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/CDC-Evaluation-Workbook-508.pdf)

Medical Research Council Guidance (2008): Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance and Medical Research Council (2015) Process evaluation of complex interventions

Cavill, N, Roberts, K, Ells, L (2015): Evaluation of weight management, physical activity, and dietary interventions: an introductory guide

Video: Creating a logic model to guide an evaluation

Logic model examples and templates

Logic model examples and template may provide a useful starting point when considering your local logic model for your programme.

-

NICE (2014) Behaviour Change: individual approaches. London, NICE. Available at: < https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49> ↩

-

Dewhirst S and Speller V (2016) Wessex Making Every Contact Count (MECC) Evaluation Report, June 2015. Primary Care & Population Sciences (PCPS), Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton ↩

-

Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A and West R (2012) Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012 Jun;107(6):1066–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03770.x. Epub 2012 Feb 28. ↩

-

Queen J, Howe TE, Allan I et al (2011) Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to General Hospital wards. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8: CD005191. ↩

-

Drummond C, Deluca P, Coulton S et al (2014). The effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief Intervention in emergency departments: A multicentre pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 9(6). E99463. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099463. ↩

-

O’Brien M and Scott A (2016) A Health Behaviour Change Framework and Implementation Plan for Health Professionals in the Irish Health Service ↩

-

Collins B (2015) Making Every Contact Count: a rapid evidence review ↩

-

Kislov, R., Nelson, A., Nomanville, C., Kelly, M. and Payne, K. (2012) Work redesign and health promotion in healthcare organisations: a review of the literature, pp. 30. Available at: http://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/media/1021/04-literature-review-for-mecc.pdf ↩

-

Wills J, Sykes S, Speller V (2018) The evidence for MECC: a scoping review. Unpublished ↩

-

https://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/media/27613/mecc-resources-fact-sheet-v9-20180601.pdf ↩

-

https://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/evidence/frameworks/ ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-magenta-book ↩

-

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/769488/MECC_Implememenation_guide_v2.pdf ↩

-

https://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/implementing/case-studies/ ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/all-our-health-personalised-care-and-population-health ↩