Liver disease: applying All Our Health

Updated 6 May 2022

The Public Health England team leading this policy transitioned into the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) on 1 October 2021.

Introduction

Liver disease and liver cancer[footnote 1] together caused 2.5% of deaths in England in 2020. Almost half of these deaths occur in those of working age (ages 15 to 64).[footnote 2]

The Office for National Statistics reports that in 2020 in England, cirrhosis and other diseases of the liver[footnote 3] are among the top 5 leading causes of death for females in the 20 to 34, 35 to 49 and 50 to 64-year age groups, and males in the 35 to 49 and 50 to 64-year age groups. It was the second leading cause of death for people aged 35 to 49 years, accounting for 9.8% of deaths in that age group.[footnote 4]

In terms of years of working life lost (among those between the ages of 16 and 64) in England and Wales, diseases of the liver[footnote 3] were in the top 2 leading causes for females in 2020, accounting for 28,000 years lost (malignant neoplasm of the breast was the top cause). For males, diseases of the liver were the fourth top cause of working life lost, accounting for a loss of 45,000 years. Intentional self-harm, ischaemic heart disease and accidental poisoning were the top 3.[footnote 2]

Since 2001, in England the rate of liver disease and liver cancer[footnote 1] deaths in people aged under 75 has been increasing, and in 2020 it reached its highest at 20.6 per 100,000 population. In 2001, the rate was 15.4 per 100,00 population.[footnote 5]

In England, in 2020, liver disease from specific causes[footnote 6] was the second leading cause of working lives lost (between those aged 16 to 64), overtaking ischaemic heart disease and accidental poisoning. Self-harm and undetermined intent was the leading cause. The fifth leading cause of working lives lost in England in 2020 was coronavirus (COVID-19).

Figure 1: years of working life lost to specific causes in England and Wales, 2001 to 2020

Years of working life lost to specific causes in England and Wales, 2001 to 2020.

Table 1: specific causes of liver disease and their ICD-10 codes

| Liver disease *specific causes | ICD-10 codes |

|---|---|

| *Liver disease – alcohol related | K70 |

| *Liver disease – cause not recorded | K721, K229–K732, K738–K742, K746, K766–K767, I81, I820, I850, I859 |

| *Liver disease – miscellaneous | K71, K744, K750, K751, K761–K785, K768–K770 |

| *Liver disease – non-alcoholic fatty | K758, K760 |

| *Liver disease – autoimmune | K720, K743, K745, K752–K754, K759 |

| *Liver disease – viral hepatitis | B15–B19 |

| *Liver disease – metabolic | E830, E831 |

| *Liver cancer | C22 |

The leading causes of mortality from liver disease and liver cancer are:

- alcohol misuse

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) related to obesity and metabolic syndrome

- viral hepatitis

- autoimmune liver disease

- metabolic liver disease and a variety of rarer miscellaneous causes

In England in 2020, in around a tenth of liver disease-specific deaths[footnote 6], the aetiology of liver disease is not recorded, but the likelihood is that the majority of these deaths are alcohol-related, with a proportion due to NAFLD, autoimmune liver disease and other causes.

In the last 2 decades, around 90% of liver deaths in England are related to lifestyle and unhealthy environments with the vast majority of these being alcohol related, and it is these diseases that are responsible for a 4-times increase in liver mortality over the last few decades.[footnote 7]

All liver diseases have a common pathway of liver damage that results from the accumulation of scar tissue (fibrosis) and when the liver is very scarred this is termed cirrhosis. There is a misconception that cirrhosis is end-stage and irreversible, but the liver has remarkable powers of regeneration. The scar tissue may not disappear, but if the underlying cause is removed liver function will often improve dramatically. The scar tissue becomes less important, just as the scar of an operation becomes less visible with time.

If the underlying cause persists, cirrhosis will inevitably progress to liver failure:

- jaundice

- ascites

- hepatic encephalopathy

- malnutrition and sepsis

In addition, around half of patients with cirrhosis develop portal hypertension (increased pressure in the abdominal veins) – varicose veins in the gullet can bleed severely and are a common cause of death. Primary prophylaxis of varices using endoscopic band ligation or therapy with beta blockers significantly reduces the risk of a first bleed.

Primary liver cancer frequently develops as a complication of chronic liver disease. In England and Wales in 2020, there were 9,666 liver deaths with a further 5,445 deaths from primary liver cancer.[footnote 2] Screening of cirrhosis patients for liver cancer with a 6-monthly ultrasound in primary care can enable effective early treatment, reducing cancer mortality.

Liver disease develops silently with no signs or symptoms, and the tests currently done in general practice do not detect underlying liver scarring or cirrhosis. The majority of patients with cirrhosis are unaware that they have liver disease until they present with often fatal complications.

Public attention surrounding liver disease is not always positive due to its links to health inequalities and the stigmatisation of this disease as being ‘self-inflicted’. The truth is that alcohol and obesity-related liver disease is a combination of an underlying genetic susceptibility and environmental factors, just like diabetes or heart disease. Liver health has been suggested as a barometer for the wider health environment and that lifestyle-induced disease is the major challenge for global health in the 21st century.

Promoting awareness of liver disease in your professional practice

Most people with liver disease die in working-age, making liver disease from specific causes[footnote 6] the second biggest cause of mortality in terms of potential years of working life lost (YOWLL) in England. Between 2001 and 2020, potential YOWLL from liver disease has gone up by 28%, while the leading cause – self-harm and undetermined intent – has gone down by 21%. The third leading cause – accidental poisoning – went up by 88%, while the fourth leading cause – ischaemic heart disease – reduced by 32% in that time period.

Mortality rates for liver disease[footnote 1] in people aged under 75 have increased by almost 35% between 2001 and 2020 (liver profile). Mortality rates for alcoholic liver disease in people aged under 75 have increased by almost 45% between 2001 and 2020.[footnote 4]

The Office for National Statistics reports for England and Wales that the average age of death from liver disease[footnote 3] in 2020 is 61 for males and 62 for females.[footnote 2]

Around three-quarters of patients who will die from cirrhosis are currently unaware that they have liver disease, and the majority have entirely normal liver blood tests until they present to hospital as an emergency.[footnote 8]

The 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on the diagnosis and management of cirrhosis recommends that very heavy daily drinkers (men drinking up to 50 units per week or women 35 units per week) should be screened for cirrhosis using one of the newer non-invasive diagnostic technologies.[footnote 9] NICE suggests FibroScan and in 2020 published a Medtech innovation briefing around its use in primary care settings[footnote 10], but simple blood tests for fibrosis markers are just as accurate and should now be available to any clinician.

The relationship between damage to the liver from alcohol becomes more rapid with higher units of alcohol consumed. More than half of alcohol-related cirrhosis occurs in very heavy daily drinkers – the equivalent of 2 to 3 pints of beer or just 1.5 to 2.5 large glasses of wine per day.

Obesity increases the toxicity of alcohol. For people with a BMI of 35 or more, one bottle of wine is equivalent to 2 bottles as far as the liver is concerned.[footnote 11]

Hepatitis C is a treatable blood-borne virus that predominantly infects the cells of the liver[footnote 12] and is a major cause of liver cancer and liver disease.[footnote 13] Around two-thirds[footnote 9][footnote 14] of people infected with hepatitis C are unaware they have the virus as they have no symptoms until decades later.

In 2016, the UK government signed up to a World Health Organization (WHO) target to reduce hepatitis C-related morbidity and mortality by 65% by 2030. A report by Public Health England in 2020 showed that substantial progress had been made between 2015 and 2019 with prevalence of the hepatitis C virus having fallen by around one-third and deaths by 25%. The report noted, however, that there had been little evidence of a fall in the number of infections in recent years.

The COVID-19 pandemic poses a serious threat to the UK’s ability to meet the WHO’s hepatitis C virus elimination goals. Diagnosis and treatment fell rapidly during 2020, but are recovering now.

New direct-acting antiviral drugs have helped reduce mortality from Hepatitis C-related end stage liver disease in recent years, along with more people accessing treatment. The ability to deliver treatments is limited by the capacity to be able to find and diagnose people.

Incidence and mortality rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have tripled across England in the last 20 years, but have slowed in recent years – possibly due to effective hepatitis C antiviral treatments becoming more available. 82,024 cases of primary liver cancer were diagnosed in England between 1997 and 2017.[footnote 15] The development of most HCCs is linked to cirrhosis, mainly due to alcohol consumption or from the hepatitis B or C virus.

NAFLD is the term for a range of conditions caused by a build-up of fat in the liver and can lead to much more severe liver disorders in later life.[footnote 16] About 10 to 15% of patients with NAFLD will develop fibrosis, which may lead to cirrhosis and, in a proportion, primary HCC.[footnote 17]

In the UK, over 90% of new undiagnosed cases of hepatitis B virus are among people born in countries with high prevalence of the virus.[footnote 18]

Core principles for healthcare professionals

This All Our Health liver disease information has been created to help all health and care professionals:

- understand specific activities and interventions that can prevent liver disease

- think about the resources and services available in your area that can help people liver disease

Healthcare professionals should:

- know the needs of individuals, communities and populations, and the services available

- think about the resources available in the health and wellbeing system

- understand specific activities that can prevent, protect and promote

Taking action

Frontline health and care professionals

Healthcare professionals can have an impact on an individual level by:

- raising awareness to the risk factors of liver disease

- being proactive and asking people about risk factors

- signposting people to the local services available

Team leaders and managers

Community level

Community health professionals and providers of specialist services can have an impact by screening for risk factors for liver disease, giving a brief behavioural intervention and signposting patients to support services such as:

- highlighting that screening and brief intervention for alcohol is effective and cost-effective with a number needed to treat of around 10 (that is, 10 patients need to be treated to have an impact on one person)[footnote 19]

- the recent Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) scheme for 2022 to 2023 which recommends – in line with NICE guidance – that people who are alcohol dependant should be screened for cirrhosis and fibrosis. It is thought this will increase the number of early diagnoses and allow more time for intervention. The aim is to achieve 35% of all unique inpatients with a primary or secondary diagnosis of alcohol dependence to be screened

- encouraging people who have diabetes, high blood pressure or high cholesterol (who can be at risk of liver disease) to speak to their GP about having a liver function check

- ensuring all high-risk groups (as identified in NICE PH43) are immunised against hepatitis A and B as per the schedule in the Green Book

Senior and strategic leaders

In England in 2019, the combination of increasing-risk (more than 14 and up to 35 units for women or 50 units for men) and higher-risk (more than 35 for women or 50 units for men) drinkers accounts for about 23% of the population.[footnote 11] Higher-risk drinkers comprise 6% of the population. A recent report reviewing alcohol consumption during the pandemic suggested that an increase in off-trade alcohol purchasing was driven by those who were already drinking heavily before the pandemic.[footnote 20][footnote 21]

Figure 2: alcohol consumption in persons aged 18 and over

Graph showing alcohol consumption in persons aged 18 and over.

*Female and male units per week. Adapted from Sheron and others.[footnote 22]

Effective population-level public health policies are able to change unhealthy environments, just as they have dramatically reduced harm from smoking. The most effective and cost-effective measures are fiscal, tackling cheap alcohol, followed by reductions in the exposure of children to marketing.

Liver death rates respond rapidly to changes in the affordability of alcohol. Scotland introduced minimum unit pricing in May 2018 and has significantly impacted on the heaviest drinkers. In March 2020, Wales also introduced a minimum unit pricing. An evaluation of the Scottish scheme has shown a reduction in drinking levels 2 years on and early data for Wales is showing similar findings.[footnote 23]

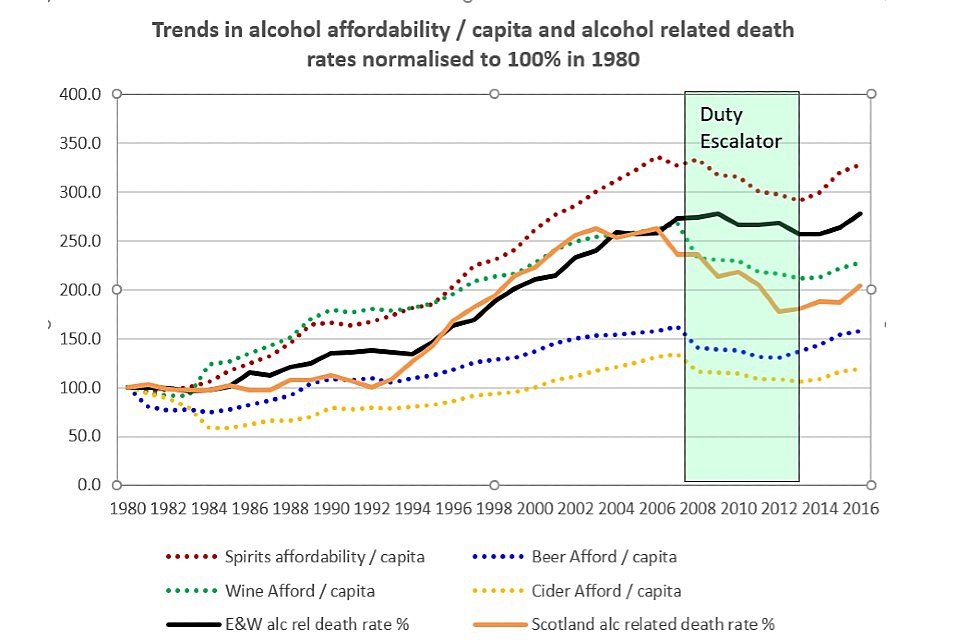

In England, between 2008 and 2013, a ‘2% above inflation’ alcohol duty escalator was implemented.[footnote 24][footnote 25] Although the price of alcohol has increased over the past 10 years, the amount of disposable income has also increased with alcohol now estimated to be 14% more affordable than in 2010[footnote 26], suggesting multiple economic factors influence alcohol consumption. The 2% duty escalator may have had a relatively large effect during this period where there was a reduction in alcohol-related deaths. The duty escalator was discontinued in 2013 for beer, and in 2014 for cider and spirits. Liver deaths in England, Wales and Scotland are increasing once more.

Similarly, the levels of NAFLD are related to the overall levels of obesity within the population, which in turn are driven by the obesogenic environments in which people live.

Figure 3: trends in alcohol affordability per capita and alcohol-related death rates normalised to 100% in 1980

Graph showing trends in alcohol affordability.

In October 2021, the English government started a consultation on the new alcohol duty system that highlighted numerous problems with the way alcohol is taxed currently. One of the proposals was to have a ‘strength escalator’ system where alcoholic drinks would be taxed in reference to the litres of pure alcohol they contain. The consultation ran until February 2022 and, subject to the outcome, the new system should be implemented by February 2023.

Understanding local needs

OHID provides intelligence and data through the various outputs of the health intelligence teams. This information is useful for monitoring and identifying the opportunity for better health outcomes of people with liver disease.

Data around liver disease is available in the:

- fingertips liver profile and bulletins

- fingertips local alcohol profiles for England

- 2nd Atlas of variation in risk factors and healthcare for liver disease in England

Public Health Outcomes Framework (PHOF)

The PHOF for 2019 to 2022 includes 160 indicators covering a wide range of health-related topics.

The PHOF alcohol-related indicators include:

- percentage of children where there is a cause for concern (C12)

- under-75 mortality rate from liver disease (E06a)

- under-75 mortality rate from liver disease considered preventable (E06b)

- adults with substance misuse treatment need who successfully engage in community-based structured treatment following release from prison (C20)

- admission episodes for alcohol-related conditions – narrow definition (C21)

The PHOF obesity-related indicators include:

- breastfeeding initiation (C05a)

- breastfeeding prevalence at 6 to 8 weeks after birth (C05b)

- excess weight in 4 to 5-year-olds and 10 to 11-year-olds – 4 to 5-year-olds (C09a)

- excess weight in 4 to 5-year-olds and 10 to 11-year-olds – 10 to 11-year-olds (C09b)

- under-75 mortality rate from liver disease (E06a)

- under-75 mortality rate from liver disease considered preventable (E06b)

- percentage of physically active and inactive adults – active adults (C17a)

- percentage of physically active and inactive adults – inactive adults (C17b)

- excess weight in adults (C16)

- proportion of the population meeting the recommended ‘5 a day’ (C15)

The PHOF population vaccination coverage hepatitis B indicators are:

- 1 years old (D03b)

- 2 years old (D03g)

NHS Digital

The NHS Digital website contains:

- a ‘statistics on alcohol’ report including data on deaths, hospital admissions, drinking behaviour and affordability.

- clinical indicators: Clinical Commissioning Group Outcomes Indicator Set, NHS Outcomes Framework and a Compendium of Population Health Indicators – alcohol, obesity and cirrhosis-related indicators can be found within these resources

- a National Indicator Library with a searchable database

Measuring impact

As a health professional, there is a range of reasons why it makes sense to measure your impact and demonstrate the value of your contribution. This could be about sharing what has worked well in order to benefit your colleagues and local people or help you with your professional development.

The Everyday Interactions measuring impact toolkit provides a quick, straightforward and easy way for healthcare professionals to record and measure their public health impact in a uniform and comparable way.

The Royal College of General Practitioners’ Liver Disease Toolkit provides links to useful resources for practitioners and the public.

The Quality and Outcomes Framework is a voluntary annual reward and incentive programme for all GP surgeries in England, detailing practice achievement results. It is not about performance management but resourcing and then rewarding good practice.

The Public Health Outcomes Framework examines indicators that help us understand trends in public health such as premature mortality in individuals with cardiovascular disease.

Further reading, resources and good practice

Advice for patients and the public

This includes:

- NHS pages on liver disease and cirrhosis

- British Liver Trust provides information and support to patients promoting the prevention and early diagnosis of liver disease

- Children’s Liver Disease Foundation focuses on supporting and researching liver disease in childhood

- Hepatitis C Trust supports people with hepatitis C

- Yellow Alert campaign aimed to raise awareness about jaundice in babies

- NHS Blood and Transplant provide information on blood and organ donation

- Alcohol Change UK provide support to people concerned about their drinking

- Healthier families, One You and NHS Live Well contain information and applications to support healthy lifestyle choices on diet, exercise and alcohol consumption

Professional resources and tools

For more information on the complications associated with liver disease, visit NICE.

The national CQUIN CCG9 scheme 2022 to 2023:

- offers the chance to identify and support inpatients who are alcohol dependant

- supports referral for a test to diagnose cirrhosis or advanced liver fibrosis

This CQUIN applies to acute and mental health providers in 2022 and 2023. It covers unique adult inpatients only (patients aged 16 years and over who are admitted for at least one night with a primary or secondary diagnosis of alcohol dependence and who have an order or referral for a test to diagnose cirrhosis or advanced liver fibrosis).

This CQUIN will help providers to implement the guidance produced by NICE on alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis and management of physical complications and FibroScan for assessing liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in primary care.[footnote 10]

To help understand how alcohol consumption and harm changed in England during the pandemic, refer to the recent report on alcohol consumption during the pandemic[footnote 20].

Good practice examples

BASL Decompensated Cirrhosis Care Bundle – First 24 Hours from the British Society of Gastroenterology provides a guide to help ensure that the necessary early investigations are completed in a timely manner and appropriate treatments are given at the earliest opportunity.

Alcohol-related disease is a joint position paper meeting the challenge of improved quality of care and better use of resources.

Getting it Right: Improving End of Life Care for People Living with Liver Disease assists healthcare professionals to understand the trajectory of end of life care in relation to liver disease.

Caring for people with liver disease: competence framework for nursing is the Royal College of Nursing framework for nurses that care for people with liver disease.

Alcohol care teams: reducing acute hospital admissions and improving quality of care provides users with practical case studies that address the quality and productivity challenges in health and social care.

-

Deaths recorded with an underlying cause of death of liver disease and liver cancer (ICD-10 codes B15 to B19, C22, I81, I85, K70 to K77 and T86.4). ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Office for National Statistics. NOMIS official labour market statistics: mortality statistics – underlying cause sex and age. 2022 (cited 14 February 2022). ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Deaths recorded with an underlying cause of death of diseases of the liver (ICD-10 codes K70 to K76). ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Office for National Statistics. Deaths registered in England and Wales, 2020. 2021 (cited 14 February 2022). ↩ ↩2

-

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Liver disease profiles. 2022 (cited 14 February 2022). ↩

-

Deaths recorded with an underlying cause of death of liver disease from specific causes (ICD-10 codes B15 to B19, C22, E830, E831, I81, I820, I850, I859 and K70 to K77). ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

British Liver Trust. Statistics: liver disease crisis. 2019 (cited 16 February 2022). ↩

-

The Lancet Commission. ‘Addressing liver disease in the UK: a blueprint for attaining excellence in health care and reducing premature mortality from lifestyle issues of excess consumption of alcohol, obesity, and viral hepatitis.’ The Lancet 2014: volume 384, issue 9958, pages 1953-1997. ↩

-

NICE. NICE guideline [NG50] – Cirrhosis in over 16s: assessment and management. 2016 (cited November 2019). ↩ ↩2

-

NICE. Medtech innovation briefing [MIB216]: FibroScan for assessing liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in primary care. 2020 (cited 15 February 2022). ↩ ↩2

-

Public Health England. The public health burden of alcohol and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: an evidence review. 2016 (cited 29 November 2019). ↩ ↩2

-

Public Health England. Tens of thousands unaware they have deadly hepatitis C infection. 2019 (cited 1 December 2019). ↩

-

National Cancer Research Institute. Deaths from liver cancer have tripled in past 20 years in England. 2019 (cited 9 December 2019). ↩

-

The Hepatitis C Trust. About the hepatitis C virus. 2019 (cited 6 December 2019). ↩

-

Burton A, Tataru D, Driver RJ, Bird TG, Huws D, Wallace D and others. ‘Primary liver cancer in the UK: incidence, incidence-based mortality and survival by subtype, sex and nation.’ JHEP Reports 2021: volume 3, issue 2, 100232. ↩

-

Public Health England. The 2nd Atlas of variation in risk factors and healthcare for liver disease in England. 2017 (cited 6 December 2019). ↩

-

The Lancet Commission. The Lancet Liver Campaign Updates: Obesity. 2015 (cited 6 Decmber 2019). ↩

-

Martin NK, Vickerman P, Khakoo S, and others. ‘Chronic hepatitis B virus case-finding in UK populations born abroad in intermediate or high endemicity countries: an economic evaluation.’ BMJ Open 2019: volume 9, issue 6, e030183. ↩

-

Sheron N, Moore M, O’Brien W and others. ‘Feasibility of detection and intervention for alcohol-related liver disease in the community: the Alcohol and Liver Disease Detection study (ALDDeS).’ British Journal of General Practice 2013: volume 63, issue 615, e698-e705. ↩

-

Public Health England. Monitoring alcohol consumption and harm during the COVID-19 pandemic 2021 (cited 1 March 2022). ↩ ↩2

-

UK Health Security Agency. Reducing liver death: a call to action. 2021 (cited 1 March 2022). ↩

-

Sheron N and Gilmore I. ‘Effect of policy, economics, and the changing alcohol marketplace on alcohol-related deaths in England and Wales.’ British Medical Journal 2016: volume 353, issue 1860. ↩

-

Anderson P, O’Donnell A, Kaner E and others. The Lancet Commission. ‘Impact of minimum unit pricing on alcohol purchases in Scotland and Wales: controlled interrupted time series analyses.’ 2021 (cited 1 March 2022). ↩

-

Alcohol Change UK. Alcohol price and duty. (cited 6 December 2019) ↩

-

Institute of Alcohol Studies. Alcohol Knowledge Centre: Price. (cited 13 December 2019) ↩

-

NHS Digital. Statistics on Alcohol, England 2021. 2020 (cited 4 February 2022). ↩