Lessons on pensions engagement

Published 7 October 2024

DWP research report no. 1071

A report of research carried out by Ipsos UK on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2024.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit the National Archives website or write to

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

This document/publication is also available on our website at Research at DWP

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published October 2024.

ISBN 978-1-78659-723-6

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report summarises research exploring consumer engagement and ways to increase public engagement with private pensions in the UK. It brings together findings from a rapid review of publicly available literature with intelligence from 6 expert interviews across the UK, Western Europe and Israel. This provides new insight and understanding into some of the factors influencing pensions engagement. The research highlights areas for further research and could be expanded in the future by seeking a wider range of expert interviews from across the industry.

The report firstly discusses the definition of engagement in the context of member interaction with pensions. The topic of ‘engagement’ appears to be one that has relevance and interest over many different fields and lessons can be learned from across a wide range of consumer sectors. Within the literature reviewed, the term is often used without a specific definition, but is variously attributed to cognitive, emotional, and behavioural components. The cognitive component involves the ability to understand pensions and the communications received about them.

Emotional engagement includes feeling connected to or ‘in control’ of your pension. And behavioural engagement includes actions such as logging into a pensions account and making decisions on products. Engagement is typically considered a positive aspect of consumer interaction. However, the literature reviewed did not explain how positive outcomes for consumers are directly caused by consumers’ engagement.

The report also discusses factors that can increase member engagement with pensions, which were the importance of communication effectiveness; information provision; and using technology. Communication effectiveness includes making information more visible, understandable, and relevant to members as well as taking a more ‘consumer-centric’ approach to communications about pensions. Information provision includes actively sending information about pensions to people, such as by emails or letters. Using technology refers to digital tools such as dashboards, interactive tools on apps, and generally improved online access to pensions information. This needs to be caveated with the understanding that the effectiveness of technological tools depends on the level of members’ digital literacy.

Several theories from behavioural economics were also noted as potentially applicable to pensions. These included the idea that behavioural change should be manageable and that benefits should feel proportionate to the amount of effort being put in.

The report also makes suggestions for ways to increase pensions engagement. One suggestion is to create awareness through different communication channels, both online and offline, and involve pension providers and employers in the communication strategy. Another suggestion is to focus on the information members want, and to present it in a simple and relatable manner. This could include using visual information, digital technologies, and personalized tools to enhance member understanding and engagement. A final suggestion is to build trust in pensions and financial providers. This is a long-term challenge that requires honest and transparent behaviour from institutions.

The report also discusses the roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders in supporting and fostering member engagement with pensions. Firstly, members have a responsibility to take on board information about their pensions and be invested in planning for their future. Secondly, employers can play a valuable role as an information channel and can provide workplace interventions to engage employees with their pensions. Thirdly, community groups and associated agencies may have a role to play. They can reach or target specific sections of the community, demographic groups, or harder-to-reach audiences. Fourthly, pension providers themselves have responsibilities such as providing accessible information, developing online tools and apps, and offering product formats that aid comparison. Finally, the government, particularly the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), has the opportunity to take on a coordinating role by establishing community networks and working with pension providers. By working alongside these stakeholders, the department could improve comparability between products, and help build and foster a greater sense of trust amongst members.

The review identified a range of possible engagement points that DWP could further develop:

- The lessons that can be learned are highly varied. They range from very specific, and manageable, actions around language (for example, using £ values over percentages), to fundamental challenges (for example, encouraging easier comparability between products). This implies that a structured plan for developing engagement is needed to assign priority over the many possible actions.

- The review also suggests actions to develop a greater sense of pensions engagement and improve member literacy in this area. We know research has already been conducted (for example, by individual pension providers of their own customers) to look at different member segments. An understanding, or even a consolidated standard model of member segments would be very powerful, allowing government and providers to better develop products and communication. This may be especially important for segments featuring more disadvantaged members, who may not attract high levels of commercial attention from providers.

- Member engagement with seldom heard audiences could be supported by developing a network of community and partner agencies. These organisations could support conversations and share information with these groups.

1. Methodology

1.1 Literature review: processes and sources

To take learnings on pensions member engagement from different sectors and benefit from a variety of experiences, a range of sources were included in the literature review. The process combined insights from pension-based sources, non- pension-based financial services and wider fields of consumer interaction and engagement, including taxation, public health and education. The research could be expanded in the future by conducting a wider range of expert interviews from across the pensions industry.

The rapid literature review was conducted in April and May of 2023. Throughout this period, the identification and sourcing of relevant material was approached through complementary online-based approaches as outlined further below.

We started with simple Google searches, exploring the results from different formulations of search terms, such as:

- ‘consumer engagement in pensions’

- ‘studies into consumer engagement’

- ‘published research on effective consumer engagement in financial services’

More targeted searches were also conducted within the online resources of likely, or potentially relevant, organisations. These included UK Government resources on GOV.UK, Open Banking, the Association of British Insurers, and the Financial Conduct Authority.

Queries were also posed to ChatGPT (https://chat.openai.com/). These included:

- ‘What drives engagement in financial services?’

- ‘What studies have looked at the role of social media in engaging consumers in financial services?’

- ‘UK based research into engaging consumers in public sector services’

- ‘Tell me more about research in the healthcare sector into engaging patients’

While ChatGPT provided interesting mentions of research studies, routinely, it did not provide links to the reports identified. In such cases, further manual search actions were used to supplement this approach and to identify potential sources for inclusion within the literature review.

The identification and sourcing stage of the process provided a set of 35 sources that provided learnings on improving interaction and engagement among consumers and pensions members. The search criteria was agreed to be limited to recent reports.

Given the multiple changes made to UK pensions in the 2007 Pensions Act, at a minimum, sources reviewed were published no earlier than 2007 . The majority of sources reviewed were published within the last 5 years, ensuring their relevance to the current pensions landscape. The literature included UK-relevant sources only as these were thought to be the most relevant to the UK pensions context. These sources are detailed further in Appendix A.

The 35 sources reviewed do not encompass the full range of material available on the subject. However, they offer a varied picture of engagement that is proportionate to the time scale the project was delivered in.

These 35 sources were reviewed with the main points and extracts captured. These were then collated and recorded in an analytical spreadsheet under headings centred around the project objectives and on themes of potential interest. The themes were based on learnings from the initial online search and scoping process. These included areas such as communications; the role of nudges, emotions and barriers; product design; and technology. This process identified themes within and across each source focusing on how consumer and pensions member engagement had been attempted and what successes or outcomes could be evidenced.

1.2 Interviews with pensions/financial experts

In addition to the literature review, five qualitative in-depth interviews, including one paired interview, were conducted with six experts either working in pensions or within the financial services industry. Interviewees were from Israel and selected countries in Western Europe who had specific expertise in pensions member or consumer engagement. This selection criteria were intended to provide insights on the general topic of consumer engagement that could be applied to the UK pensions context.

With the exception of the UK, they were also from countries that have launched public-facing pensions dashboards programmes which meant experts were able to discuss the impact of these on pensions engagement. These interviews were designed to complement and add further insight to the learnings from the literature review.

The formal objectives for the interviews were:

- to gather information on engagement methods (and their outcomes) that have been implemented in different countries to see how these approaches may inform pensions engagement methods in the UK

- to test the UK-based evidence found in the literature review and gather views about its applicability to alternative contexts

Insight from the expert interviews is integrated into the report to explain or amplify the learnings from the literature review.

2. Definition of engagement

One immediate question was to consider what we mean by the term ‘engagement’, and what definition we should use when identifying and reviewing relevant sources. Further, to explore how to improve member engagement with pensions, it was important to consider what engagement looks like, and what it leads to.

Consideration was also given to whether ‘engagement’ itself results in improved outcomes for members and whether any evidence can be offered to support this.

The term ‘engagement’ was used widely. It was often referred to as a ‘general good’ as it was assumed that to have engagement is to have a positive aspect of member interaction with service. This was, for example, identified in the Pension Policy Institute (PPI) report into saving for retirement[footnote 1].

Though no source provided a quantifiable definition, other sources gave more explicit definitions. One example of this is the definition of engagement in the context of non- workplace pensions offered by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA):

‘We define engagement as ‘interest and involvement in the non-workplace pension, where involvement is a positive decision to do, or not do, something in relation to their pension.’[footnote 2]

A complementary view was presented by the expert interview in Open Banking, which is the system of allowing access of member banking and financial accounts through third-party applications. This describes the focus on what that technology is trying to achieve and where member engagement sits in the overall process:

We know the outcomes we want to deliver… which is people being more engaged with their finances… and so on… You’ve got to have the services in the market. The next step is that consumers have to adopt them, so you have to sign up to them. The next step is they have to… like them and continue to use them and then the final, most difficult to prove step is that we achieve the outcomes that we’ve defined.

Obviously, outcomes is the most difficult to prove or demonstrate. - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

This expert interviewee also drew attention to the idea that it is harder to measure engagement and therefore hard to demonstrate whether actions to increase engagement have explicitly worked. On the other hand, it was considered to be easier to demonstrate whether changes to the structure of pensions impacted people’s experience of pensions and the resulting outcomes. For example, the impact of increasing the minimum contribution rate for a workplace pension.

The literature review pointed to some common components which are attributed to engagement, broadly representing cognitive interaction, emotional impacts and behavioural markers. We discuss each of these further below, as well as touching on the theme of positive outcomes as a direct result of engagement:

2.1 Cognitive interaction

To be engaged is commonly taken to involve elements of awareness and understanding. Especially in a technical field such as pensions, this is often seen as the ability to understand and process information that may be complex. For example, Bank of England research into different reporting formats and improvements to comprehension found that providing a visual summary of the Inflation Report and making it relevant to people increased their engagement and understanding of the information being presented[footnote 3].

Another useful concept referenced in the literature produced by Public Health England[footnote 4] was that of ‘literacy’. This refers to the ability of a consumer to take on board information and to understand it and what it means for them personally. They can then use this to make a judgement, possibly leading to some action on their part.

This was also commented on by one of the expert interviews, who held the opinion that lack of understanding regarding pensions is a global issue.

It’s a pervasive issue that, in most cultures of the world, pensions are not understood - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

2.2 Emotional impact

A number of references to engagement in the literature reviewed spoke of emotion and how these can be closely linked and related. Emotion-based responses to pensions were mentioned by some[footnote 5] as powerful and important factors and/or barriers to engagement. A sense of capability, confidence, connection, or control were mentioned as positive emotional aspects of engagement. Conversely, feelings of uncertainty, fear of making a mistake, and feelings of distance or disconnection can serve as barriers and have a negative effect upon engagement.

2.3 Behavioural markers

In some reports member engagement was linked to identifiable behaviours and actions, not simply feelings reported by members. The behaviours included logging onto an online account, looking at documentation (such as statements), making a decision, or consciously and informedly deciding not to act.[footnote 6]

Reasons for a lack of member engagement mentioned in the literature largely built on the opposite of the behaviours listed above. For instance, a lack of engagement was shown by members being unaware of details of their pension or not reading information about their pension. People also tend not to make active decisions about their pension which is partly because any positive outcome from decisions will not be felt for a long time. People also find it easier to make decisions about immediate or short-term issues. Active decisions are also harder for people to make because people may feel they are unable to affect the distant future.[footnote 7] Similarly they may be confused about pensions and so prefer not to think about them[footnote 8].

Experts interviewed for this research reported general low levels of pensions engagement among members. Groups with particularly low engagement were younger cohorts, those with dependent children and those with little or no disposable income.

Groups with more disposable income or more extensive pension provisions were seen as more engaged. However, overall, there is low engagement with pensions among populations. This was summarised by Expert #1:

To generalise, in just about every western country in which there is state retirement provision, individual and company provided provision, many people find it very difficult, or lack motivation, to engage in retirement saving until they’re approaching retirement - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist United Kingdom/Israel

Experts also commented on engagement strategies, particularly information-based ones, that seem to reach those who were already engaged most effectively, rather than those more distant from their pensions:

I think we do better and better on the ones that need the least help… But with that [improved data visualisation] you reach the usual suspects, so people that have the baseline interest in this space. So the ones that are not so interested, maybe also a poorer range of socioeconomic status, they’re least likely to look this up, they’re least capable to look this up and I think there we still have to do more - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights & Pension Communication, The Netherlands

Closely linked to some of the emotional responses discussed above, expert interviewees commented on how the theme of fear and confusion can limit, or act as a barrier to, engagement with pensions:

When it comes to money and long-term decision-making, most people don’t trust themselves. It’s like ‘I don’t have the confidence and I don’t trust myself to make the right decisions.’ They don’t trust themselves, or their spouses or their partners or their families, right, in having the expertise, the knowledge. There are very few people who feel sufficiently financially literate to know what to do when it comes to retirement saving -Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

If people don’t think they will understand what they see they stop before even looking at what to see. Some people may not be motivated because they fear pulling up this information just gives them bad news, like not going to the doctor - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

2.4 Trust

A further factor mentioned in reports and by interviewees was lack of trust in pension providers and the pension system more generally. This is connected to a range of factors including past negative experiences with pensions providers and a negative view on government commitment to pensions in the medium and long term.[footnote 9] [footnote 10]

As one expert (#3) argued, if pension providers were obligated to promote pensions dashboard systems, it would allow for ease of comparability between products and providers. It was argued that, in turn, this would show providers to be open and transparent, instilling a sense of trust, and ultimately engagement, among members:

You know, if you’re pension provider and you know your fees are high, you’ve got no incentive to encourage people to use a pensions dashboard because they end up switching their pension anyway. So, you would have to have a regulatory mandate to force them to promote it, promote it properly, to explain the benefits of it. I’m not sure the pensions dashboard is in the interests of the incumbent providers in many cases - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

2.5 Positive outcomes

Positive outcomes as a direct result of engagement were rarely identified in the literature reviewed. It was also difficult more widely to identify direct links between engagement and positive outcomes when compared with non-engagement. Some studies did cite evidence of this link. For example, in the public health field, Public Health England found a link between patients who are more engaged with their health leading to better patient outcomes, both in the short and longer term.[footnote 11] Conversely, the Financial Conduct Authority found members can make ‘sub-optimal choices’ if they disengage due to factors such as ‘informational complexity’ or ‘choice overload’.[footnote 12]

It is also important to consider that positive outcomes may not be limited to members. More engaged members could have a beneficial effect on supply-side organisations and service providers. The Institute for Government, for example, makes the argument that citizens being more engaged in the policy discussion around Net Zero could support the Governmental priority.[footnote 13] This suggests that more engaged pension members could, in turn, result in better actions by providers if a very large increase in the proportion of engaged members were to occur. If, for example, the majority of customers are engaged and demanding better, or seeking the most competitive, products and services, then pensions providers may find it in their interest to improve their offer.

In summary: This chapter discussed the definition of engagement in the context of member interaction with pensions. Our research found that the term ‘engagement’ was often used without a specific definition, but was variously attributed cognitive, emotional, and behavioural components. The cognitive component involved the ability to understand pensions and communications received about them. Emotional engagement included members feeling connected to or ‘in control’ of their pension. Behavioural engagement included actions such as logging into a pensions account and making decisions on products. Engagement was typically considered a positive aspect of member interaction, but the literature reviewed did not explain direct links between members’ engagement and positive outcomes in their pensions.

3. Key themes regarding engagement

Across the 35 sources reviewed, a number of major themes came forward regarding routes to better engagement. Many of the reports focussed on how improvements in communication can make information more visible, more understandable, and more relevant to members. The benefits of guidance and other interventions were also discussed. The use of technology in providing ‘real time’, easy to understand information and giving users interactive tools was also noted as a promising area within the literature. Spanning these topics, lessons can also be derived from Behavioural Economics to see where ‘nudges’ help people engage and overcome functional and emotional barriers. Finally, a more minor theme in the literature was around product design and how easily, or otherwise, members can compare, understand and engage with pension products.

3.1 Information and communication: the challenge

Experts interviewed commented on the theme of communication, suggesting that much pensions communication has limited value or use to customers. This is because it is caused either by satisfying regulatory requirements, or reflecting corporate processes, rather than providing useful information centred on member needs:

You’ve got your regulation that aims to protect the interests of consumers and savers, but often is used by pension providers and funds to drive the form and content of engagement. And then you’ve got people who have deep expertise writing the stuff. And what most product providers and company pension arrangements have failed to do, is to really centre the individual, the ordinary person, in the middle of the engagement and to think about how things are from their point of view - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

What’s happened historically is you have decision makers in financial institutions. They have a finance background, super smart. They get it. Then there’s something that needs to be communicated and then it’s set into stone and goes to the marketing department who now make something out of that. And, by the way, before we send it out, legal rewrite all of that to be on the safe side. That shouldn’t be the process.

There should need to be awareness at the top level that communication is key - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

The provision of information and how this is communicated was frequently commented on in the literature, across a range of reports and sectors. As illustrated in the quotes below, this focus is partially dependent on members struggling to understand useful information in technical fields:

-

‘The communication of [pension fund] charges (usually in percentages and sometimes hard for respondents to find) is challenging for respondents to understand.’[footnote 14]

-

‘One of the reasons central bank publications are often challenging to read relates to the technical nature of the subject matter - economics. A YouGov poll conducted in 2015 found that only 12% of respondents said politicians and the media discussed economics in an accessible way.’[footnote 15]

-

‘T&Cs are typically lengthy and complex, so it is not surprising that most consumers are not inclined to read the entire fine print.’[footnote 16]

-

‘[A] challenge for health care professionals is that of patients’ health literacy. This refers not just to reading and understanding health information but to the patient’s ability to make use of health information and apply it to choices and decisions. This is a known barrier to engagement.’[footnote 17]

The challenge of member understanding of information as mentioned in these reports relates back to the engagement component of cognitive interaction as mentioned previously. Specifically, they relate to the ability and ease of accessing information, making sense of it, and using it to make decisions.

DWP’s own research indicates that getting people to look at information relating to their pension is difficult. A recent study[footnote 18] suggests that more information, presented in the right way, for example easy to understand, will tend to encourage engagement. That research also reveals that ‘non-looking’ at (i.e. not reading or engaging with) pensions information is a widespread behaviour. It found that although participants claimed to look at their annual statements, emails and frequent communications, such as monthly, were particularly unlikely to be engaged with. This shows that while clear information is important for engagement, there are lessons to be learnt in how to get that information to people and how frequently to do this.

3.2 Lessons that can be learnt regarding provision and communication of information

The literature reviewed pointed to several suggestions around enhancing the ability of information and communication to support member engagement. These can be organised as; improving member access to information, improving the content of information available to members, and improving the expression of information/how it is communicated to members. As commented on by one of our expert interviewees, these factors are very likely inter-related:

What drives [engagement]? Is it better information? Or easier access to information? Or is it awareness?, Whatever the reason increasing [engagement], that’s hard to say - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

3.3 Accessing information from trusted sources

Some reports commented that useful access to information is not only about availability, but also where the information is sourced from. In particular, whether or not that source is seen as relevant to the member, and if that source is trusted.

Information provided through multiple channels (for example, publications, statements, but also online resources and social networks) is recommended in some reports. This is because different audiences access information through different routes, some more or less formal than others.[footnote 19][footnote 20] This may be particularly important when providing information to some ethnic groups, non-native English speakers, or people who do not respond to standard forms of communication. His Majesty’s Revenue & Customs’ (HMRC’s) experience in engaging ethnic groups in Tax Credits was to disseminate information and resources both formally through HMRC, and through partner agencies.[footnote 21]

Reports identified employers and, where known, existing pensions providers as being important routes for disseminating information to pension holders. Both were considered to benefit from being familiar and more trusted sources of information.[footnote 22]

Despite general low levels of trust reported in pensions and financial services, evidence shows that people trust their own pension provider more than member groups and other sources to give them information on what they can do with their retirement pot.[footnote 23]

I would say that the most powerful lever is through the pension provider that the consumer is most closely linked to. So, the one that they’re currently contributing to. They are the one who are in active communication with their customers, however it might be fairly sparse, but they’re actively communicating with their customers or employees of course, because it could be a work pension scheme - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

3.4 Content that engages consumers

An important lesson on successful communication from other organisations is about giving members the right information. It’s essential to give members the information they need to improve their knowledge and understanding, as well as what they may want to know. Or, as one of the expert interviewees put it:

It’s got to comply with the law, but it should not be the regulation that is driving the communication and the engagement. It should be what is needed to help ordinary men and women understand what they need to understand… Relevant, understandable, accessible - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

As one report indicated, content is associated with further action and learning. Further investigation is needed to discover whether these simply occur together, or whether content itself causes or prompts further action. The FCA’s ‘Financial Lives Survey’ identified the value for some pension scheme members of reading their annual pension statement: If a member has read and understood their pension statement well, they are more likely to have reviewed their pot in the last 12 months; to be aware of their contribution levels and to have thought about how much they should be paying in. They are also more likely to be aware that there are some charges incurred and to have thought about the way their pension is invested.[footnote 24] However, this only relates to a subsection of pensions customers. The study also shows that recall of receiving a statement is low to begin with, that readership isn’t universal, and that of those who do read it, not all understand it. Levels of readership and understanding also vary by age and other demographics.

A study by Nest Insight[footnote 25] sought to understand if certain messages would prompt better pensions engagement, compared to other messages. Specifically, whether messaging around responsible investment would motivate people to log onto their pension account more than generic saving or investing messages. Results identified a general savings message as the most effective at getting all members who had not previously registered for online access to sign up. However, the responsible investment email was the most impactful for those who say environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues are very important to them. This treatment was significantly more effective at driving email click-through rates conditional on email opening, relative to the Investment email, among those who said they were most engaged in ESG issues.[footnote 26]

An FCA report identified three important pieces of information to encourage savers to engage with their pension. These were the current value of their pension pot, how this has changed on an annual basis, and what the implications are for their future situation:

‘At best, the annual statement is skimmed to look for the current value of their non- workplace pension and how it compares to the previous year… Respondents believe that having greater visibility on what their non-workplace pension should mean to them, now and in the future, would lead to greater engagement on their part.’[footnote 27]

This information focus was echoed in one of the expert interviews, relating to the Danish pension dashboard system. The Danish dashboard has stopped over-providing information to members, concentrating instead on what is most useful to provide at that time:

Keep it simple. We have had 5 or 6 different versions and we still have them with a lot of text. Now we just came to the conclusion that we have what we need to show the users something they can-, by looking at-, get an overview of where they’re standing and we just have 5, max 10 minutes of the user’s time. So, we have overview, ‘What is the current value of your pensions?’ That’s something they are interested in. And then the others are, ‘What can you expect to get? What is your official retirement age?’ - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

This idea of providing focussed and relatable information was also noted in the case of Expert #4 from The Netherlands:

Understanding what do people want to know, and it’s probably, first and foremost, ‘Do I have enough?’ And that’s something where we make progress. We need more progress, but we make progress. For example, in the Netherlands, we have great data on consumption, so it’s not only that we can say, ‘Hey, this is your expected pension,’ but we can also contrast that with information on average spending, because only the two together give the answer to the pressing question, ‘Do I have enough? And how do we do that? These are the tricks to visualising what you can buy from that, making abstract, strange numbers concrete by relating them to something that people can understand, which is all the things you can buy, and also translating the money into something we save it for. We don’t save the money to have money later on. We need the money to buy stuff - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

3.5 Expression and style: improving engagement through communicating more effectively

Much attention was paid in all the literature to how improvements in the design and expression of communications can improve member comprehension and engagement.

Much of the literature returned to the challenge of communicating in technical fields (such as finances, taxation, health) to non-expert members. It identified how changes in expression, style, and design help people to take in relevant information and become more engaged. The need for using effective communications was summed up by one of the expert interviews:

Whenever people receive anything to do with pensions, it’s mired in complex language. Most people, when they first get a communication on pensions, an annual statement for example, will look at it and when they get to line 3 it’s like, ‘I don’t understand…’ and they stop looking at it. So, the thing about plain language is very important. It’s language, personalisation and access. Providers and pension funds have a lot of data on savers and technology is coming on in leaps and bounds. So, in today’s day and age, it should be possible, feasible and affordable, to personalise an engagement experience around the circumstances of an individual - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

In one of the sources reviewed, a presentation aimed at employers, ‘5 Steps to support your employees’ wellbeing’ [footnote 28], Aon recommends the use of ‘real world’ expressions, rather than technical language to communicate the value of pension saving, for example:

‘Putting your coffee fund in your pension could make a bigger difference. A UK higher rate taxpayer (at current rates) paying the same £3 every day for a cup of coffee needs to earn pre-tax income of £1,887 per year to fund their coffee. If they forego their coffee purchase and redirect the money to their pension via salary sacrifice, in 10 years they could have an extra £24,018 in their pension, but there is no guarantee of this.’

This was echoed in an academic study cited by Expert #4 which showed how putting things in ‘real terms’ can be helpful when it comes to pensions engagement and understanding:

We tried to motivate people to save more, and you can use the same just to motivate them to become more engaged. We used consumption baskets. That’s not our idea… [Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association] developed these lifestyle labels… they have 3 lifestyle buckets [minimum, moderate and comfortable].[footnote 29] Then they explain to you now if you have a certain pension then this means you can go once on a vacation to the UK, for example. This is what we see helps people to understand these abstract numbers shown to them – what they can buy from their pension - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

These points of expressing information in a more relatable way and using visual summaries can also be seen in the Bank of England’s efforts to make their communications more accessible:

‘We find that the recently introduced Visual Summary of the Inflation Report improves comprehension of its main messages in a statistically significant way compared to the traditional executive summary. We also find that public comprehension and trust can be further improved by making the Visual Summary more relatable to people’s lives.’[footnote 30]

A Bank of England working paper published with the Behavioural Insights Team[footnote 31] also cited academic research into how changes in communication can lead to better accessibility and higher engagement. In summary, they found that the following can increase or improve engagement:

- reducing the [amount of] information that individuals need to process

- making information relevant to individuals’ circumstances

- employing linguistic ‘involvement’. For example, increasing the use of first and second person pronouns (for example, ‘us’-/‘you’) while reducing the use of third-person abstractions (for example, ‘the Bank of England’)

- expressing financial costs in pound values instead of percentages to improve comprehension

- using ‘everyday language’, such as ‘rising prices’ rather than more technical ones such as ‘inflation’

- using visual personalisation, such as interactive charts or calculators that people can input figures or locations into that are relevant to them. An example mentioned in the working paper was “an interactive chart that invited participants to find out what unemployment was like in the region in which they reside”

- ensuring narrative coherence, which means explaining things in terms of what they mean for individuals or relating them to things that are important for them or that they understand. An example used was “explaining the Monetary Policy Committee’s interest rate decision with reference to prices, pay and jobs”[footnote 32]

Further examples were found from the fields of taxation and public health:

‘The research suggested that how information about tax credits was communicated was crucial to take-up among Chinese and Indian individuals. Promoting the positive aspects of tax credits (such as ‘entitlements’ rather than ‘benefits’) and providing relevant case studies for customers to benchmark against were seen as good ways to make tax credits resonate more with these groups.’[footnote 33]

‘The most common health literacy strategy reported in major health literacy reviews is ensuring that health and social care services and information is clear and accessible for all, regardless of individual ability. Materials can be simplified by the use of plain and direct language and the careful application of good layout and design. The latter may employ the use of tested pictures and symbols, although care needs to be taken that these are understood correctly by the target audience. This has been found to positively influence literacy levels.’[footnote 34]

The effect of colour coding with regards to retirement saving and pensions outcomes was also highlighted by one of the experts interviewed:

Because we just show information, but still maybe [what would be useful is] a red, green, red, yellow or green line depending on entering your current salary and then combine that and say, ‘Okay if I retire at 60 how does it look?’ Red - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

3.6 The role of guidance, interventions, and workplace sessions in driving engagement

As cited during one of the expert interviews, advice and guidance from third parties can be greatly valued when it comes to making decisions relating to pensions:

We value someone doing it for us. We don’t trust ourselves. It’s complex. What we value is someone else doing it for us. Although we don’t trust others either, we trust them more than ourselves to do it - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

Equally, formal, regulated pensions advice is commented on in the literature as potentially powerful in enhancing engagement:

‘Those who have had regulated financial advice in the last 12 months are more engaged and have a better understanding of their pension than those who have not.

This is very encouraging, although we cannot be sure from the questions asked whether the advice results in better engagement and understanding, or if those with better engagement and understanding are more likely to seek advice.’[footnote 35]

However, the limitation to this route is the fact that take up of professional pensions advice is low, particularly for those with lower levels of savings, wealth or income. As HM Treasury commented in 2017:

‘There is an ‘advice gap’ for retirement advice for people without significant wealth. High quality financial advice can have a significant impact on retirement incomes, and people often increase their savings rate as a result of taking advice. For example, research by Unbiased found that those who sought retirement advice increased their retirement savings by an average of £98 a month. However, less than a third of people have accessed financial advice on their pension. The Financial Advice Market Review (FAMR) found that many people perceive financial advice to be unaffordable or ‘not for people like them’.’ [footnote 36][footnote 37][footnote 38]

As noted in the previous section, employers are routinely identified as an effective and valued route. Employers could not only provide (general) pensions information to and encourage engagement with pensions holders, but also share information and facilitate education on finances more generally.

‘Employers can help play a big role in tackling this knowledge and engagement gap by providing information and guidance to employees about how to maximise their finances in later life. The potential benefits are many: engaged scheme members might well be motivated to perform well and could be less likely to suffer financial stress. Financial education seminars are a great way to get people thinking about the future.’ [footnote 39]

‘Employee engagement programmes should remind staff about their existing pension benefits – 83% of employees whose employers currently give them pension contributions value these as part of their current benefits package, making it a valuable employee retention tool.’[footnote 40]

‘Running a modular financial education programme can help simplify complex financial issues into an understandable and actionable format for your employees. From our surveys, we’ve found that financial education is a popular choice with employees – 4 in 5 in their early career would like support from their employer, and the most popular method of support is face-to-face.’[footnote 41]

Using the employer channel was also supported by Expert #4 as a way of reaching and engaging younger cohorts:

Young people are problematic because the topic is far away and there is this belief, ‘I can do it tomorrow, I can do it a year down the road and so on.’ So, we were never able to test that but what we found is that employers can play a big role in that. Let’s say you have your intake talk at the new position and then you discuss the benefit package and by the way here is your 10-point bucket list for starting your position.

Why not have them check your account, check your contribution fund? - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

Such interventions can be seen to support the ‘literacy’ concept mentioned earlier. Similarly, Public Health England found that equipping people with better foundational knowledge can help them to feel more confident and engaged in important decisions. This is particularly true for decisions which they may otherwise be uncertain of, with a delayed benefit, and especially among lower socioeconomic groups:

‘A number of studies have found that combining general literacy, language and numeracy skills training with empowerment strategies to increase self-efficacy and attitudes towards health may be beneficial in terms of influencing [positive long-term] health behaviours of families in disadvantaged socioeconomic groups.’[footnote 42]

3.7 ‘Nudging’ people towards engagement

Several reports identified where and how the approach of behavioural economics, and specifically ‘nudge theory’, can help to increase engagement. Behavioural economic principles may encourage engagement with services that people may not want to think about, or that feel distant, complex or risky. The behavioural economics-based reports analysed in this research identified the barriers preventing people from engaging, and the targeted actions needed to overcome them.

One expert interview mentioned an academic study where effective and stimulating messaging was framed in regards of an older, trusted audience:

We did something with a large Dutch pension scheme… each month they send out these newsletters but few people read these newsletters, so… We use a classic marketing trick, which is showing what others do… in the first large-scale survey with the scheme, we measured the peers that people socially identify with, or where they think, ‘These are age factors or characteristics where I can assume, if I do that, it must be a good behaviour.’ And then we sent out targeted emails, where we gave them information like, ‘Hey, by the way, people your age read this interesting article in this pension magazine. Please also click on this link to read it.’ - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

The use of technology for engagement was often discussed in relation to behavioural economics and how this could be applied to overcome barriers to pension engagement. This is discussed in further detail in the next section, but the report ‘Engaging people with pensions via digital dashboards’[footnote 43] effectively outlines significant barriers to engagement in behavioural economics terms. These are inertia (the tendency towards inaction), present bias (valuing immediate gratification), ‘hassle factor’ (the effort required versus the outcome’s value), choice overload (too many or too complex options) and lack of knowledge or ability. ‘Present bias’ was identified by an expert describing the difficulty of getting members to think about the future:

It is almost impossible to get people to engage in something financially that doesn’t have an effect on them within a longer term than 5 years. The 5 years basis is something that is kind of impossible - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

Expert #1 also attributed widespread lack of engagement in western countries to the ‘present bias’ factor – not thinking about a life event seen as being in the future.

Expert #2 also commented on the challenge of making pensions feel important at younger life stages, when so many other financial priorities seem more immediate and important:

When we are, let’s say, 50 or beyond, at some point, really see that you have a dream that could come true if you want to retire at a certain age or travel or so on. But, as a start, when you are establishing a system, family, and you are buying a house, it’s almost impossible to get people engaged, because they have so many other expenses at the time and they want to travel with their kids and other things - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

Experts #2 and #4 argued that pensions communication should be framed by the retirement objectives of the member. This would mean engagement would be focused on their future plans, rather than on just the financial product itself.

You have to [encourage the view], ‘I want [to achieve] such and such and my pension can help me,’ instead of just, ‘I want to engage in my pension.’ So, it should be the other way around because then they have something, a goal or a wish or something that the pension should help them with - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

This expert also outlined an interventionist approach adopted in Denmark, where mortgage applications must take on applicant’s data for later-life funding from the national pensions dashboard system. This nudges applicants to log-on to access and share their pensions information, which then starts a conversation with the applicant around their long-term saving.

Let’s say you’re a young family, you’re getting a mortgage, buying a house then the bank always asks the spouses to send their pensions data to the bank. So that way they engage a bit, they have to log on and send them the information, and then they also have a talk with the bank and might say, ‘Okay, you have this dormant pension account. Wouldn’t it be a good time to think about that?’. So, in that way, they talk to their bank adviser about their pensions - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

Taking evidence from academic studies conducted in the Netherlands, one expert identified monetary incentives as being effective in overcoming the ‘friction-cost’ or ‘hassle-factor’ barrier:

One thing that I know from study of colleagues is, it’s a classic, is monetary incentives. Like saying, ‘Well, if you do this and check this out, by the way, we raffle so many vouchers,’ so that what’s worked in the study of my colleagues. Or to emphasise, ‘Hey there’s free money,’ so there’s maybe a tax rebate or other economics. Don’t leave this unused, just use it, because that’s usually working - Expert #4, Behavioural Insights and Pensions Communication Specialist, The Netherlands

And some ‘nudges’ can be stronger than others. For example, one expert identified dashboards, along with legal measures compelling members to save for retirement, as an important factor of engagement:

Another very important thing that can contribute to engagement is access to an understandable, relevant and accessible dashboard - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

Some experts saw some element of automatic enrolment or a minimum compulsory engagement as beneficial, such as automatic enrolment in workplace pensions in the UK. They suggested this helps increase engagement because if people already have something in place automatically, they are more likely to engage as it is easier to do so. One expert suggested automatic enrolment to a pensions dashboard service as a potential way to optimise engagement and overcome some of the barriers to initial adoption:

If everybody with a live pension was automatically enrolled into a pensions dashboard… it would be very easy then to encourage people to add other [pension pots] to it. I think the challenges of adoption shouldn’t be underestimated - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

The literature review also identified several non-pension examples to support the inclusion of a behavioural economics inspired approach for encouraging member engagement. An important idea in nudge theory is that the behaviour change should be relative to the amount of effort needed, for it to appeal to the member. This principle is shown in the successful experience reported by Public Health England in their evaluation of the Drink Free Days communication campaign:

‘Behaviour change posed a challenge among increasing and higher risk drinkers (38% of whom think they do not need to cut down) but taking drink-free days appears to be a good strategy for this group, as it is a message that is already understood and favoured by this audience in comparison to other methods of moderation, and so can be leveraged as a prompt to change. Increasing and higher risk drinkers are more likely than [non-increasing or higher risk drinkers] aged 40 to 64 to understand the value of drink free days, seeing them as a good way to cut down (85%) and to reduce the health risks (77%).’[footnote 44]

Applying this to pensions would involve asking or suggesting to people that they do certain small, achievable actions that have an outcome seemingly ‘worth the effort’ of the action put in.

Similarly, nudges provided in a light-touch, supportive manner, and mediated through technology proved successful in engaging adult learners in a small-scale study by Department for Education:

‘Weekly text messages of encouragement to adult learners (aged 19+) enrolled on maths and English courses improved attendance rates by 22 percent (7.4 percentage points, from 34.0 to 41.4 percent) and achievement rates by 16 percent (8.7 percentage points, from 54.5 to 63.2 percent) … Text messages are an inexpensive and scalable way of reaching learners at times when they can take advantage of information. There is a growing body of evidence in other fields to suggest that personalised text messages sent directly to participants can have a significant effect on behaviour.’[footnote 45]

Furthermore, the concept of individually personalised nudges supported by digital technology was commented on in the expert interviews:

Personalised and interactive video can and should be used. For example, if I sent you a video saying, ‘You’re currently paying £43 a month into your retirement savings account, and you’re projected that when you reach age 60 you’ll be able to have a monthly pension income of £250, did you know if you increase that to £50 a month, your monthly pension income would go up to £300 a month? Is there another amount that you’ve considered saving each month? Type it in here.’ - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

If you had open banking connection linked to your Pension Dashboard, and you got a pay rise, for example, that would be automatically noted, and then, you’d get a message saying, ‘We see you’ve got a pay rise. You should consider increasing your pension contributions,’ for example.” - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

3.8 Enabling engagement by digital means

Another point raised in the previous quote is the usefulness of knowing a wide range of financial information about an individual, as this can help to personalise advice provided to them and can help understand where pensions savings fit into their wider financial context. One expert suggested that engagement in pensions could be strongly supported through digital tools that can present this holistic picture of a member’s financial position:

If you think about all that data that’s available, if I had access to that data on you, I should be able to help you make decisions to improve your financial health. So, I can see whether you have loans, whether you have debts, what your mortgage is, what your income is. I don’t think people should be looking at retirement savings in isolation from the rest of their life - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

Multiple reports identified clear and powerful examples of member engagement enabled by digital technology – whether this be improved online access, digital communication, or app-based interactive tools. However, this can be dependent on the level of ‘literacy’ that people have in digital technologies and the appetite and skill they have in using them.

It’s [engaging online or by digital means] not only a question of digital skills, but also digital confidence - Expert #5, Product Manager mypension.be (Belgium’s official online pensions portal), Belgium

This is also discussed by the FCA on the varying levels of consumer engagement when buying insurance:

‘Three-quarters (76%) of those who have excellent internet ability always shop around for insurance, compared with 63% who self-rate as good or fair, 39% who self-rate at poor or bad, and 25% who never use the internet.’[footnote 46]

Willingness and readiness to use digital tools is likely to grow across age groups with digital skills and abilities particularly strong among younger consumers and pensions members. Both the literature review and expert interviews revealed a number of examples of how technology is enabling engagement:

These days people are expecting to be able to access information through their mobile devices, through their iPad, through their laptop. And, if I want to increase my monthly savings, I want to be able to do it on a device - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

One expert interview reported how pension dashboard or portal functionality in both accumulation and decumulation phases was driving use and engagement in Belgium:

We have a very big engagement and mypension.be is very much used, on a yearly basis we have around 2.5 million unique users. Not only in the accumulation phase, but also in the decumulation phase. So, once you get your pension, it’s also on mypension.be that… you have a follow up of your monthly pension, you can see what are the deductions etc. On the one hand, it’s a pension dashboard, a pension tracking system during active life. But if you’re pensioned, it’s also administrative space.

80% of the people who took their pension have been visiting mypension.be in the two years prior their pension take up. ‘What if I stopped working two years earlier than my pension date? How does that affect my pension amount and things like that?’ So, we give them scenarios… to have a better view on the impact of their choices on their pensions - Expert #5, Product Manager mypension.be (Belgium’s official online pensions portal), Belgium

In the UK, Open Banking/Application Programming Interface (API)-enabled accounts provide users with information and tools they can use to inform decisions across their spending and their saving. Research by the Open Banking Implementation Entity (‘Open Banking’ for short) revealed high level of satisfaction, engagement and some behaviour change among users of such apps. Over 60% of spenders surveyed reported being better able to keep track of their money and on top of their spending.

The results were even more positive among savers – with nearly 70% of users saying they found it easier to save money left over each month and build up their savings:

‘Nearly two-thirds of all Savings app users (64%) reported that their overall level of savings had indeed gone up since they started using a Savings app.’ [footnote 47]

In the same research, qualitative interviews with users identified the aspects that Open Banking app users particularly appreciated in the technology:

‘[Spenders] often reported appreciating how well the app allowed them to keep an eye on their finances across different accounts and different types of transactions. They also felt that the efficient organisation brought a capability not offered by standard financial providers. Savings app users often appreciated the easy visibility of seeing their savings grow. Users also mentioned the insights and recommendations that their apps made, as useful in helping them to both improve their finances and change their behaviour.’ [footnote 48]

We were able to interview representatives from the Open Banking sector and they confirmed that the appeal of this enabling technology was steadily growing:

We’re seeing big growth in the likes of payments and so forth, so people are doing it, there’s a substantial number of people each month who are using open banking for the first time - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

Another report from Open Banking described how API-enabled financial platforms, such as those for building up savings, are seen to offer compelling and powerful member propositions. The main cause for this is their ability to bring together data (for example, spending/pricing/savings) from a range of sources or providers. This allows users to monitor activity, access easy to understand analysis, and receive recommendations for products or actions that can potentially benefit them.[footnote 49]

This is echoed in the interactivity provided by the Danish pension dashboard. The dashboard allows users to see how retiring at different ages affects the value of their retirement income. This, together with the fact the dashboard works alongside digital banking advisory tools, gives people convenient access to information and the opportunity to ‘scenario-plan’ their retirement:

The dashboard can show what you can get and pensions at different retirement ages all the way from 60 and up to 75. And if you’re working it’s an ongoing payment until retirement. So, there’s a huge change for lifelong monthly payments (i.e., an annuity) if you take it when you’re 75 or if you take it when you’re 60 - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

Powerful engagement stories enabled by technology were also identified in other fields, such as taxation and health promotion. For example, HMRC reported an increase in confidence among self-employed individuals and small businesses once they began using Making Tax Digital software:

‘This constant engagement with financial processes helped to increase their confidence and to ease the emotional burden around producing a VAT return. The VAT return process was now more familiar, and the elements which contribute to it were better understood … Having this real-time financial clarity has helped build a feeling of control of the business finances. This has helped with planning for the future and more effectively being able to anticipate and mitigate challenges.’[footnote 50]

A Public Health England report also showed the appeal and effect of an online calculator as part of its ‘Drink Free Days’ campaign:

‘The campaign’s online drinking comparison tool, which shows users how much alcohol they drink compared to others their age, saw impressive levels of engagement from the target audience during the campaign. 90% of those who started to use the tool went on to complete it.

Those who used the Drink Free Days app felt they drank less after using the app than before. Users were almost universally positive about the app, with the majority reporting taking action as a direct result of downloading it, most reducing alcohol intake and increasing drink free days. A sizeable minority of users reported broader actions, including changes to diet and physical activity.’[footnote 51]

Further detail on pension dashboards was provided by an expert interviewee, quoting the case of Denmark, where these have been long established, but took many years to provide users with full coverage. This gradual development likely meant that member engagement changed as coverage increased. The expert commented that dashboards provide the information that members need to engage with their pensions, but cautioned they do not provide an overnight solution to engagement challenges:

If you look at the dashboard, for example, it took us, to be honest, 8 years before almost all providers delivered all of the data for their customers to the dashboard. So, even making a dashboard, that’s one thing, but it doesn’t really have an effect if only 20%, 30%, 40% of the pension providers give us their data. So, it’s not a magic wand, the dashboard, it’s a tool that people can get aware of, to know it’s there to get an overview, but it’s difficult. It’s really difficult to get people engaged in pensions, especially if you are at a young age - Expert #2, Pensions expert, Denmark

Other experts agreed with the Danish experience that digital tools needed and/or benefitted from promotional support, as well as being easily accessible to optimise their chance of engaging members:

You’ve got to make people aware of these tools. You’ve got to encourage them to use them. So, I think it would say to me promotion is very important - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

When we launched the information on when people can take mypension.be, we got a lot of media coverage and since that moment the increase is explosive and it has also one of the biggest brand recognition rates of public services in Belgium - Expert #5, Product Manager mypension.be (Belgium’s official online pensions portal), Belgium

Even if they don’t find your dashboard on their own, they will find your dashboard just because there you have put doors towards your dashboard everywhere - Expert #5, Product Manager mypension.be (Belgium’s official online pensions portal), Belgium

The UK Open Banking expert identified a number of challenges to be addressed in fully realising the benefits of such a digital system in the pensions field. They pointed to a significant difference in the way that pensions data is intended to be used and the different status of money held in a pension. They also pointed to the importance of data quality and data consistency, which may be hard to ensure, and the difficulties that may come from it being a long-term process.

Finally, they identified the comparative ease of user access available to members through their banking apps for Open Banking. They felt that different, less familiar, access systems for pension dashboards were likely to be off-putting:

Those 7 million users monthly who are using open banking, they’ll be much more inclined to use it because it feels and looks the same. And that becomes more acute as you go into open finance and open data. This aspiration to give a very similar interface for the customer, it promotes and encourages that uptake. And I think the siloed approach and making a different customer experience of accessing these services has that limitation in that, you know, people don’t want to have to sign up for this in a completely new way. And it will discourage them from doing so - Expert #3, Open Banking, United Kingdom

This last point was echoed by expert interview #5:

To convince people that are not really interested in pensions, to use your portal, you have to offer a good digital experience… otherwise they use it once and never again. mypension.be is there for everybody and you just log in and then you see your personal file. So, there’s no registering you just have to log in with your unique identity card and you will see your file. There’s no membership. You can just access it because you’re a citizen of Belgium - Expert #5, Product Manager mypension.be (Belgium’s official online pensions portal), Belgium

3.9 Engagement by product design and scheme options

Within the literature reviewed, the concept of whether product design can encourage engagement with long-term saving was rarely discussed. There were, nevertheless, some interesting perspectives to include.

One idea proposed was product formats that give greater saving flexibility. This could help address the ‘present bias’ referred to in the behavioural economics analysis of barriers discussed earlier:

‘Balancing the need for saving in a pension against the need to save into liquid savings can be particularly difficult for those who might find pension contributions difficult to afford on their own, and requires a degree of flexibility and agility, supported by policies and products designed to work with a more flexible and agile working style.’[footnote 52]

Recent research by Nest Insight highlighted the potential for salary sacrifice to appeal and engage both employers and employees, particularly among smaller employers. This research also identified features such as higher contribution defaults and auto-escalation as positive design elements.[footnote 53]

The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) report, ‘Defining Ambitions Shaping Pensions Reforms Around Public Attitudes’ recommended that pensions be designed to meet savers’ income needs in retirement. The idea behind this was to overcome some of the uncertainty around the outcome of pension saving. Particularly since the outcome of (the increasingly common) defined contribution pensions schemes can be less clear to members.

‘Our research demonstrates that supported consideration of the income that people will need [at] retirement, increases their propensity to save. The case for saving into a pension specifically is strengthened by a greater understanding of defined- contribution pensions. Finally, beginning from what the public want (and need) in their retirement and working backwards to set a contribution level and pension age is likely to encourage higher contribution rates and a greater feeling of certainty.’[footnote 54]

While financial advisers encourage their clients to think about and set their contributions accordingly; IPPR were proposing this be ‘designed in’ at a product level and done at scale.

Being able to compare products is important in making informed choices. The CMA states their ambition is to promote an environment where people can be confident they are getting great choices and fair deals.[footnote 55] This can be difficult in the pensions field:

‘Pensions are considered complex and the effort involved to gain effective knowledge relative to the value of the pension can appear disproportionate. The ability to effectively compare features across providers is felt to be hard.’[footnote 56]

In contrast to this, for other financial products, for example insurance and savings, the FCA states, there are active and growing levels of product comparison:

‘Covid 19 has increased consumer interest in shopping around for financial products. We have also seen more switching in insurance and more attention being paid to policy details. Three in ten (29%) adults with other financial products like current accounts, savings accounts and ISAs are more likely to shop around in the future.

For those who had never shopped around for these products previously, 13% say they are now more likely to do so.’[footnote 57]

We can also see that product design is an area where consumer and pensions member engagement can, and should, feature. And how the way in which things are designed can directly influence how they are used. As Open Banking comment in ‘Consumer priorities in Open Banking’, there is value in making products as accessible as possible for disadvantaged groups. In doing so, a much wider group are often found to benefit.

In 2011, the Financial Inclusion Taskforce recommended the promotion of ‘jam-jar accounts’ to give people more control over their money and to make banking more attractive to financially excluded and marginally banked people. These accounts would split members’ balance into spending, saving and bill-payment pots. They would improve members’ budgeting and bill payment behaviour through automatic low balance alerts and transfers of funds between ‘jam-jars’.

Today, the young, tech-savvy, early adopters of challenger accounts value the very same ‘innovative’ features that were recommended for people on the margins of banking, some eight years ago.[footnote 58]

In summary: This chapter discussed the importance of communication effectiveness, information provision, and using technology. Communication effectiveness included making information more visible, understandable, and relevant to members as well as taking a more ‘consumer-centric’ approach to communications about pensions. Information provision included actively providing information about pensions, while using technology referred to digital tools such as dashboards, interactive tools on apps and generally improved online access to pensions information.

Several theories from behavioural economics were also noted as potentially applicable to pensions, such as the idea that behavioural change should be manageable, and that benefits should feel proportionate to the amount of effort being put in.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Learnings from the literature review helped to identify ways to support and foster member engagement. It also developed some indication of priority and whether they can be seen as relatively ‘quick wins’ or longer-term strategic targets.

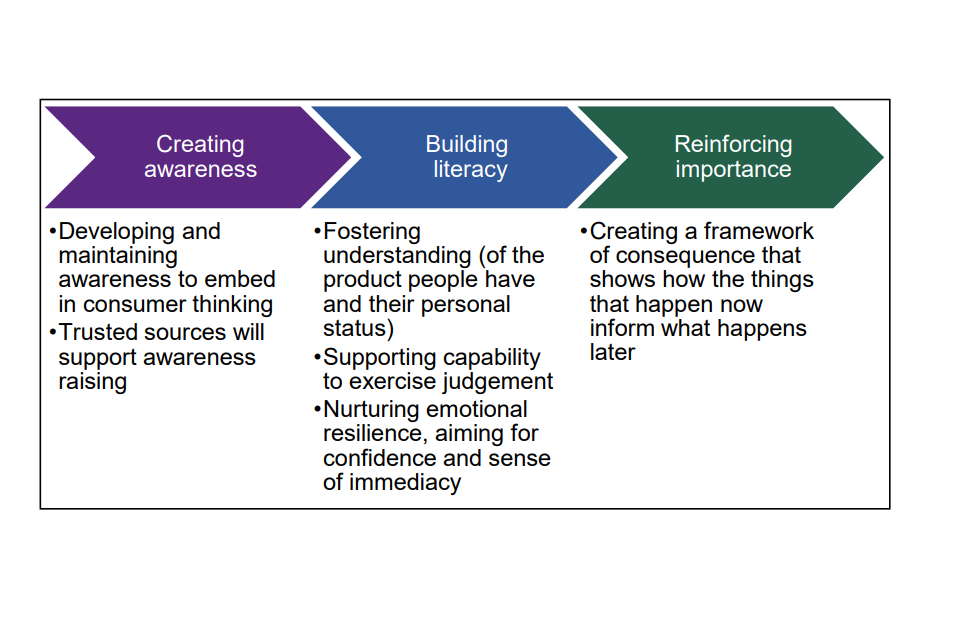

To conclude, we will return to the initial concepts of engagement that were discussed in Chapter 2 of this report. Based on the literature review we created the model shown below in figure 4.1, and will discuss lessons learnt on each aspect in detail.

Figure 4.1: Model consolidating possible engagement actions

1. Creating awareness

- Developing and maintaining awareness to embed in consumer thinking

- Trusted sources will support awareness raising

2. Building literacy

- Fostering understanding (of the product people have and their personal status)

- Supporting capability to exercise judgement

- Nurturing emotional resilience, aiming for confidence and sense of immediacy

3. Reinforcing importance

- Creating a framework of consequence that shows how the things that happen now inform what happens later

4.1 Creating awareness

From both the literature review and expert interviews, the lessons that were identified are:

- Various communication channels and routes should be used to reach a wide audience and ensure members are able to access information in different ways. It is also important to consider issues related to neurodiversity and the differing ways in which members read, interpret and understand the information presented to them.

Engagement has to recognise diversity. We talk about all diversity. We talk about ethnicity, we talk about sexual diversity, gender diversity, age diversity. And now, the big thing coming, and it’s about time, is engaging more effectively with and catering for neurodiversity - Expert #1, Global Pensions Strategy and Consumer Engagement Specialist, United Kingdom/Israel

- Communication channels should include both digital and offline, as both provide value and utility to different sections of the pension audience

- Pension providers and employers should be essential to any communication strategy as these are seen as directly related (and therefore relevant) and – to some degree – trusted sources

- Moreover, both formal and informal communication channels should be used. We use ‘formal’ to describe traditional communications activity for example, campaigns, publications, and online resources. ‘Informal’ stands for community and multi-agency based communication routes such as those used by HMRC to contact harder-to-reach audiences. [footnote 59] These were discussed in Section 3

- Focused messages that regularly prompt, remind, or encourage through a convenient channel should be considered. This was evidenced in the DfE study on how to engage adult learners[footnote 60], awareness works best when it is reinforced. However, contact that is too frequent has been found to decrease engagement. A trade-off needs to be found where communications are enough to reinforce messages, but not enough to discourage engagement.

- We are cautious, from a feasibility perspective, to recommend as a quick win that all pension information should be available digitally and non-digitally. However, it certainly should be a high priority action, given the need to reach all sections of the pensions’ audience.

4.2 Building literacy

From the analysis, the lessons are:

- Focus on the information people want and the information they need to understand what options/actions are available to them.

Keep it simple. Keep it very in line with what they really want to know - Expert #5, Product Manager mypension.be (Belgium’s official online pensions portal), Belgium

- The information people want and need appears to be information about their current pension pot value and its growth or decline over a given period, commonly the last year. Alongside this is an indication or projection of what this will give them in the future and any options available to them that could help to improve their projected levels of retirement income.