Report on the Inclusion at Work Panel’s recommendations for improving diversity and inclusion (D&I) practice in the workplace

Published 20 March 2024

Chair’s cover letter to the Minister for Women and Equalities

Dear Secretary of State,

You asked me to chair an ‘Inclusion at Work’ Panel for 6 months to:

- identify the interventions that increase fairness, inclusion, and diversity, explaining what works, why, and how; and developing and disseminating resources to promote this

- make the most compelling arguments in favour of good practice, and against bad, with the best evidence and data available

- develop a new Inclusion Confident Scheme, complementing other such kitemarks, embedded first in the Civil Service and public sector

This paper summarises the work of the Panel, our conclusions reached and why, and a proposal for what the government may do to support more effective practice.

We have spoken to over 100 people representing 55 organisations, which themselves represent many thousands of people in the public, private and charity sectors. We have worked with, and studied the work of, some leading academics in the fields of behavioural and occupational psychology, neuroscience, and employment law.

As you will read, we do not recommend introducing a new scheme at this stage. This is for 2 reasons. We assessed the range of existing similar or directly relevant schemes, and their efficacy. Many already cover the concept of inclusivity in some way. Introducing another accreditation or compliance scheme risks duplication and perverse incentives, and before those the challenge of communicating any awareness at all. Second, the very broad and subjective definitions of ‘inclusion’ make a precise and useful scheme near impossible. As we show below, definitions of diversity, equity and inclusion are contested and can even be – legitimately – mutually exclusive.

However, having conducted many constructive discussions about the problem you wanted us to address, there is clearly an appetite and need for an authoritative means to assess the quality and value for money of workplace practice. This should be something that can be used for both large organisations and small, in all sectors. The Panel has looked at the example of the ‘Education Endowment Foundation’s (EEF) Teaching and Learning Toolkit’, and recommend the Equality Hub builds a similar model for assessing interventions in pursuit of inclusion.

Done well this will achieve your first 2 requests of the Panel: to identify the interventions that work, and to make compelling arguments for them and against those that don’t. The precision and specificity of such a tool will equip leaders and managers in all workplaces to assure themselves that they are investing their limited resources in ways that achieve their ultimate goals. The EEF’s tool has contributed to a ‘self-improving’ system in the vast domain of teaching and education, empowering and unleashing greatness rather than mandating mediocrity. We believe the same model has the most potential for lasting change in the workplace. In time, this work might evolve into a set of practices which could be codified into independent accreditation. As we set out below, large organisations in particular may come to value this level of trusted, objective, accountability for their efforts, linking their stated goals for inclusion with their visible, measurable, outcomes.

Alongside such a tool we also recommend more clarity on employment law as it affects inclusion practice, for example the governance and behaviour of staff networks, and HR policies. There have been a number of recent important rulings concerning the Public Sector Equality Duty and Equality Act. The Equality and Human Rights Commission has a clear mandate to help employers understand their implications.

Many of those we spoke to in undergoing this work are keen to help build an Inclusion Practice evidence tool, and test its value both for their own employees and those they represent across all sectors. In backing and piloting such a toolkit, we believe that the Department for Business and Trade (DBT) could be a trusted and pioneering exemplar for the Civil Service workforce, and beyond.

I hope our work will make a useful contribution to what is an important, and complex, challenge. It has been a pleasure working with such a distinguished panel of experts and I am grateful to them, and to everyone with whom we have worked, for engaging in such good faith and candour.

Pamela Dow

Panellists

- Pamela Dow (Chair), COO Civic Future, founder of the Government Skills Campus and Leadership College for Government

- Ama Ocansey, UK Head of D&I, BNP Paribas

- Ashley Ramrachia, Founder and CEO of Academy (recruitment firm)

- Barry Ginley MBA, CEO of Tamstone Consulting (disability and inclusion specialists)

- Denis Woulfe OBE, Co-Chair, Leaders as Change Agent Board (OBE for services to Business and to Equality)

- Emer Timmons OBE, Co-Chair, Leaders As Change Agents Business Board (OBE for services to Women and Equality)

- Marcus Whyte, CEO and Founder, Zyna Search (recruitment firm)

- Nick Walker, Deputy Director, Government Skills and Curriculum Unit

Advisor to the Panel

- Professor Iris Bohnet, Albert Pratt Professor of Business and Government and Co-Director, Women and Public Policy Program, Harvard Kennedy School

Background

In 2022 the government published the Inclusive Britain action plan.[footnote 1] It comprised 74 actions to address the underlying causes of unjust ethnic disparities. The plan recognised that not all disparities were a result of discrimination and that, in order to tackle unfair disparities, there was a need to understand and address their multifaceted causes in a data-driven way.

Action 69 of the plan committed the government to establishing an independent Inclusion at Work Panel with a remit to develop and disseminate resources to help employers drive fairness in the workplace. Action 71 committed the government to using evidence from the Panel’s work to develop a new, voluntary ‘inclusion confident scheme’ to improve diversity and inclusion (‘D&I’)[footnote 2] practice and progression in the workplace.

The Panel was appointed in June 2023 to fulfil this remit by the end of December 2023. Since its establishment the Panel has convened experts from the private, public, and third sector. Panel members, both individually and collectively, have met a range of people with knowledge and interest in this topic. Drawing on gathered insights, and their existing expertise, panellists have established consensus around a set of shared principles, designed a high level framework, and recommended an evidence tool. We believe these have the potential to give employers the knowledge and confidence to undertake D&I activities in a more rigorous, evidence-led way.

This report is the Panel’s final report to the Minister for Women and Equalities (and Secretary of State for Business and Trade) on what good practice could look like, and the contribution the government might make to increasing it.

Summary of recommendations

We recommend that:

-

The government endorses a new framework (outlined in Recommended framework for D&I success) which sets out criteria employers might apply to their D&I practice, for effectiveness and value for money.

-

The government funds, and works with, a research partner to develop a digital tool similar to the Education Endowment Foundation’s ‘Teaching and Learning Toolkit’.[footnote 3] This will allow all leaders and managers, in every sector, to assess the rigour, efficacy, and value for money of a range of D&I practices. It will also ‘nudge’ commercial or activist providers of interventions to evaluate and prove impact.

-

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) explains and clarifies the legal status for employers in relation to D&I practice, with particular focus on the implication of recent rulings for HR policies and staff networks.

Why is a new approach to D&I in the workplace needed?

There is widespread consensus that a diverse, inclusive workforce can reap meaningful rewards for businesses and employees. Drawing on a wide range of experiences and backgrounds in an organisation improves the potential for effectiveness, is conducive to innovation and creativity,[footnote 4] and reduces groupthink[footnote 5].

In recent years explicit D&I functions and roles in-house, and the supply of workplace training by external providers, have expanded. According to LinkedIn data[footnote 6] published in 2020, in the 5 years prior, the number of people globally with a ‘head of diversity’ title more than doubled (107% growth). The number with a ‘Director of Diversity’ title grew 75%, and ‘Chief Diversity Officer’ 68%. The research also found that the UK employs almost twice as many D&I workers (per 10,000 employees) as any other country.

Another estimate[footnote 7] based on Freedom of Information Requests to 6,000 public authorities cites the existence of approximately 10,000 public D&I jobs, at a cost of £557 million a year to the UK taxpayer. According to Harvard Kennedy School Professor Iris Bohnet (who closely advised this Inclusion at Work Panel), US companies spend roughly $8 billion a year on such training.[footnote 8] Management consultant McKinsey also assessed racial equity commitments from 1,369 Fortune 1000 companies from May 2021 onwards. Their analysis found that companies pledged around $340 billion to ‘driving racial equity’ with around $141 billion committed between May 2021 and October 2022. While the motive behind a public commitment to a more inclusive workplace is principled, the effective means to achieve this end are less clear and increasingly contested.

The terms ‘diversity’, ‘inclusion’ (and other associated terminology) are conceptually ambiguous, rapidly evolving, and often conflated. The terms ‘equality’ and ‘equity’ are also used interchangeably, incorrectly. Within academic literature[footnote 9] these have different definitions, sometimes as conflicting concepts (equality of opportunity versus equality of outcome). While, recently, much emphasis has been on ‘diversity’ in the form of the descriptive representation of characteristics (primarily ethnicity and gender), it is not self-evident that focusing on visible characteristics promotes a meaningful level of diversity. An organisation may be proportionately representative of the population in gender and race. However, if the workforce remains largely socio-economically and geographically homogenous (for example, composed of middle-class graduates from South East England) it is likely unrepresentative in life experience and values.

‘Inclusion’ is yet more ambiguous as it is less empirical. The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) defines inclusion as “the practice of including people in a way that is fair for all, values everyone’s differences, and empowers and enables each person to be themselves and achieve their full potential and thrive at work.”[footnote 10] The Chartered Management Institute (CMI) defines it as “ultimately about attracting and unleashing talent, gathering different perspectives to solve wicked problems, creating a collaborative culture and driving innovation.” Each definition implies interventions are necessary but both remain abstract and, fundamentally, subjective.

As noted, employers are also now expected to take action to achieve ‘equality’ and ‘equity’. Harvard Law Professor Minow[footnote 11] highlights a conflict between the 2 concepts: equality requires impartiality and focuses on fairness for future opportunities; equity considers past (dis)advantage and intervenes to correct current disparities. However, judgements of relative advantage between individuals and groups (by virtue of their characteristics), and the proportionality of differential treatment required to address disadvantage, is complex and likely beyond the capability of a corporate HR team.

Because D&I is a social, not physical, science, causality between interventions and outcomes is often near impossible to discern, even if positive correlations should be taken seriously and shared. Definitive claims of ‘what works’ can be misleading or inconclusive. Results in one context cannot necessarily be replicated in another as workplaces are complex social environments with countless variables. This is not to suggest that employers should disregard data and scientifically produced findings, and we have tried to cite many examples of high quality research in this report. Employers already evaluate many aspects of business operations using empirical, quantitative metrics. They should approach D&I practice in the same way. Evidence is essential for measuring progress and impact, and evidence exists for many interventions. Easy access to authoritative data and insights, to better understand value for money and effectiveness, would give employers more confidence in their strategic choices.

A need for a new approach to D&I is also evident as in recent years some well-meant practice has been shown to be counterproductive and, in some cases, unlawful. For example, in Maya Forstater v CGD Europe and others,[footnote 12] the claimant received over £100,000 for being discriminated against at work for her (protected) gender critical beliefs, and in Furlong v Chief Constable of Cheshire Police,[footnote 13] it was found that Cheshire Police discriminated against a white candidate through incorrectly applying the positive action provisions of the Equality Act. A Ministry of Defence review into the Royal Air force (RAF) found that pressure to meet recruitment targets for women and ethnic minorities had led to unlawful positive discrimination against white men.[footnote 14]

The evidence points to confusion. Employers are expected to understand disadvantage and equality in great depth, and keep up-to-date with the most current positions. However, assessments of disadvantage require deep understanding of comparative history, and comprehensive analysis of socio-economic data, the capability for which simply does not exist in most organisations.

We believe that, while employers have a duty to fully grasp and apply the law, leaders and managers should not be expected to possess a sophisticated knowledge of the demographic, historical, and socio-economic debates relating to the relative advantage and disadvantages between groups. Nor, crucially, should they outsource or delegate this to those with potentially conflicting incentives. Leaders in all sectors can and should be empowered to better understand their own workforce data, and how specific practice can help productivity, retention, fairness and belonging.

Engagement insights

The Panel, supported by the Equality Hub Secretariat, met a range of people representing large and small businesses, the public and third sectors, and academia. The Equality Hub had, prior to the Panel being established, begun preliminary engagement work, notably 4 90-minute workshops from 15 to 18 November 2022, with 34 organisations represented. These discussions gathered insights about:

- understanding and awareness of inclusion

- the motivation for, and participation in, existing schemes

- accreditation and assessment

The Panel convened more in-depth, wide-ranging, discussions, including 5 roundtables between September and October 2023, for public and third sector organisations. Senior civil servants and ‘staff network’ leaders were represented, alongside a range of employers, activists, academics and diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) professionals. The purpose was to understand participants’ experience of workplace D&I, gain insights into examples of good and bad practice, and views on a new accreditation scheme or evidence toolkit. Supporting these, members of the Panel also hosted informal and formal one-to-one meetings and small group discussions, across Whitehall (including with the Civil Service Policy Profession) and the wider public sector, and with: ACAS (The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service), the Fawcett Society, CIPD (The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development), CMI (The Chartered Management Institute), and the BCC’s (British Chamber of Commerce) Workplace Equity Commission.

Brief summary of insights

Participants were asked:

- what D&I means to their organisation

- what they are trying to achieve with their D&I strategy or practice

- what barriers exist to positive impact

There was consensus that D&I is a complex and sometimes sensitive workplace agenda, with competing definitions and unclear evidence. Although some participants cited examples of what ‘good’ does or might look like, measurable impact was scarce.

Employers want to ‘do the right thing’ but cited barriers including:

- the size of the organisation and the resources available

- lack of time to test new ideas or have ‘good faith’ discussions with staff

- little or no data

- lack of confidence

- fear of saying and doing ‘the wrong thing’

Increasingly issues of freedom of speech and expression affect D&I debates in the workplace, exacerbated by recent high profile court cases. Non-legally-trained managers and leaders are finding it difficult to navigate the Equality Act and associated duties. People mentioned fear of legal action, conflicting or unclear HR policies, and that definitions of bullying, harassment and discrimination are becoming ‘weaponised’ in employment grievances and pre-emptive HR or legal advice. A number of participants suggested that employers, in an attempt to go ‘above and beyond the law’ in their D&I efforts (albeit with good intentions) were inadvertently breaking the law.

All agreed that more, better, data and evidence would improve D&I strategies and interventions, and if this was in some way government-curated or endorsed, employers would have more confidence in citing it. Both quantitative and qualitative insights from the experience of others were said to be valuable. Participants reported that quantitative data would help employers set aspirational targets for recruitment, retention, progression and pay. Qualitative data, such as that from staff surveys, would help employers make contextual choices suited to their size, maturity, sector, and workforce demography. All cited the difference of capacity and needs in large corporations compared to small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

Emerging themes: barriers to more effective D&I practice

- A lack of accessible, plain-language, robust data on the efficacy of D&I interventions

- Active initiatives for which there is little, no, or conflicting evidence of efficacy (often at significant cost)

- Little evaluation of D&I strategies

- Misinterpretation or misapplication of equalities legislation (with financial and reputational cost)

- Politicised and polarised D&I debates, particularly on gender (and race).

A government-endorsed tool which addresses these would give managers and leaders more confidence. It is important that these are precise and specific, not just highlighting abstract and unchallengeable values which are open to competing interpretations. The format should be self-improving – that is, it should evolve positively over time – and adapted to suit the huge range of sectors and employers, in the private, public and charity sectors.

Guiding principles for D&I practice

The Panel concluded that a principles-based framework would most suit the needs of employers. This would be neither definitive nor exhaustive, to be explained with real or hypothetical illustrations of application.

Principle 1: ‘Heterogeneous’ – or meaningfully diverse – workplaces are desirable and beneficial

Teams and workplaces which are heterogeneous – comprising people from a range of backgrounds and with a range of characteristics (be they sex, ethnicity, or viewpoint) – should be an aspiration. Social homogeneity in workplaces can be associated with limited experience and perspective, suppressed talent, workforces unreflective of the population, and can reinforce disadvantage. By contrast, heterogeneous workplaces can be associated with improved problem solving, tolerance and a culture of positive challenge, increased trust and collaboration, and improved performance (all correlated with access to a wider talent pool).

Principle 2: Visible diversity alone does not automatically make an organisation meaningfully diverse or inclusive

A visibly diverse organisation is not necessarily meaningfully heterogenous. Simply increasing the proportions of a particular identity characteristic in the workforce does not maximise the advantages of diversity of thought and experience. There is evidence that equality of opportunity is improved when people from disadvantaged backgrounds can see themselves visibly reflected in an organisation, but employers must also consider less visible diversity, including socioeconomic and educational background, and problem-solving style.

Principle 3: Diversity and inclusion (and equity) decisions are rarely impartial. Concerted efforts should be made to mitigate the impact of ideological biases

Adjudication on matters of diversity, inclusion, equality, and equity are often fraught with subjective judgements about what these terms mean and how they should be applied in practice. ‘Inclusion’ is often in the eye of the beholder. Good managers balance the sometimes conflicting interests of different groups in the workforce in an open and respectful way which simultaneously recognises that not all requests can be accommodated at all times. Decisions about D&I should be rooted in evidence as far as possible and be context-specific, rather than be based on abstract, social-theoretical, definitions of privilege and disadvantage.

Principle 4: The impact evidence on D&I is mixed and often inconclusive. Initiatives grounded in robust evidence should take primacy and employers should be open to learning and change

Causality between certain D&I interventions and outcomes will be near impossible to discern in a complex social environment such as a workplace where there are countless variables. However, positive correlations between interventions and outcomes that are consistently observed over time should be taken seriously and shared. This does not mean that employers should disregard research. Rather, they should take care to design any D&I strategy in a way that allows for ongoing scrutiny and embeds regular review and evaluation of impact.

### Principle 5: Positive, not just negative, stories on D&I in the workplace should be widely recognised and effective practice should be shared

While there is a lot of work to do to make workplaces more inclusive, there has been significant positive change over time. It is right that inequalities and lack of inclusivity in workplaces should be highlighted where they exist, but this should be counterbalanced with, and put in the context of, a general trajectory of improvement. Signs of progress, explained, can improve morale and motivate employers and employees to support new and successful practices. Furthermore, ‘showing, not telling’ – that is, explaining and demonstrating what has worked, how, and in what context – helps inspire and give confidence to others.

Principle 6: D&I activities should be cost-effective. Employers have a responsibility to use money dedicated to D&I in a way that demonstrably achieves intended outcomes

Reviewing and evaluating the efficacy of D&I interventions is rare. According a recent employer survey,[footnote 15] 1 in 4 employers with a ‘DEI strategy’ do not evaluate its effectiveness. It is incumbent on all organisations, whether public or private, to be satisfied that money is spent responsibly. This need not be critical of past efforts. Done well, more scrutiny of D&I interventions and their return on investment will prevent the proliferation of poor practice and of waste.

Recommended framework for D&I success

The Panel believes a clear, concise framework is a useful tool for helping organisations conceptualise what successful D&I practice entails. Our proposed framework has 5 criteria for organisations to consider when designing, implementing, and evaluating good D&I policies and practices; and conditions which promote long-term success of D&I initiatives. These criteria encompass 2 themes: embedding evidence-informed practice, and recruiting and retaining staff inclusively, using sophisticated understanding of what works.

Embedding evidence-informed practice

Criteria 1: Gathering evidence systematically and comprehensively

We found that the collection of robust data and insights is rare. Gathering evidence on D&I metrics confers many benefits. It allows organisations to identify context-specific problems within their own organisation, rather than assuming that society-wide inequalities are present. It also allows employers to target interventions proportionately to address problems, while reducing the use of resources on addressing inconsequential or absent issues.

Many organisations do not collect inclusion-related data. The CIPD’s Inclusion at Work 2022 report[footnote 16] surveyed over 2,000 UK senior decision-makers in organisations across many sectors. It found that only 38% of employers collect some form of equal opportunities monitoring data from employees and/or job applicants.

Writing in the Harvard Business Review, law professors Joan C. Williams and Jamie Dolkas argue that, given that companies today acquire data about virtually everything else, “their failure to track diversity statistics sends a message of indifference—or, worse, may be taken as evidence that the company has allowed bias to flourish.”[footnote 17] They argue that while many companies committed to D&I goals should attentively track ‘outcome’ metrics such as proportions of underrepresented groups within the workforce, “outcome metrics indicate only whether you have a problem, not where it’s arising and how to fix it.” This is where ‘process’ metrics (which can pinpoint problems in employee-management processes such as hiring, evaluation, and promotion) are important.

D&I consultant and author Lily Zheng[footnote 18] also highlights the problem with embarking on D&I initiatives without a robust foundation of data and insights. According to Zheng, too many organisations ‘start’ their D&I journey with arbitrary ‘DEI’ interventions that have no clear objective when effective action actually requires companies to collect and learn from data before arriving at solutions that ‘match’ the challenges.

McKinsey and Companies’ analysis[footnote 19] based on work with hundreds of companies seeking to launch or transform ‘DEI strategies’ also identifies poor data gathering as a common reason for the failure of those strategies. Their research shows that companies which have begun to fulfil their D&I commitments take a systematic approach where they first use quantitative and qualitative analytics to establish a baseline before determining what interventions are most needed.

Criteria 2: Putting evidence into practice

The evidence suggests that many organisations’ D&I approaches are driven by pre-existing notions, assumptions, and pressures rather than empirical evidence. This is reflected in CIPD’s[footnote 20] data from over 2,000 organisational leaders. Only 25% said they consult data before new inclusion and diversity activity is planned and when asked why they choose certain D&I areas to address over others, “data showing there are inequalities in this area within the organisation” did not appear on the top 5 in the list of reasons. Additionally, 1 in 4 employers say that their approach to D&I is entirely or mostly reactive – for example, “in response to societal events like the Black Lives Matter protests.” Similarly, the Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) analysis of financial firms’ D&I approaches has found that “firms’ strategies and actions are not consistently based on a clear diagnosis of their specific circumstances nor an evaluation of their effectiveness.”[footnote 21]

Much evidence on D&I initiatives shows mixed, often inconclusive results. Studies such as Urwin et al.’s (2013)[footnote 22] systematic review of D&I practices found that while previous research had found there to be anecdotal evidence of the benefits of diversity, little tangible evidence was available – and that which was available related to correlation, with little evidence on causation. Another study[footnote 23] which reviewed the literature on interventions for reducing prejudice concluded that the causal effects of many widespread prejudice-reduction interventions, such as workplace diversity training, remain unknown. Although some intergroup contact and cooperation interventions appear promising, much more research is needed.

Despite strong evidence to suggest particular interventions are not effective and sometimes counterproductive, many employers continue to use them. For instance, there has been a proliferation of diversity training in recent years. This is despite much evidence showing ineffectiveness. Sociology Professor Musa Al-Gharbi[footnote 24] points to a robust and ever-growing body of empirical literature that suggests that diversity-related training typically fails at its stated objectives. He reports:

- an absence of meaningful or durable improvement in organisational culture and workplace morale

- a failure to increase collaboration or exchange across lines of difference

- failure to improve hiring, retention or promotion of diverse candidates

Sociology Professors at Harvard[footnote 25] studied 800 American firms over 3 decades and found that 5 years after training became required for managers, companies saw no increase in the proportion of minority groups in management. In fact, the proportion of black women and Asian-Americans at that level actually dropped.

However, evidence of interventions shown to produce desired results in workplaces does exist. For instance, a study[footnote 26] found that in multiple choice tests where there was a penalty for incorrect answers, females were less likely to guess (and instead, skipped the question) than males of an equal ability. Because women skipped more questions, they received lower scores than their male counterparts, who were more willing to guess and therefore got more answers correct. In contrast, when there was no penalty for wrong answers, men and women answered all questions. One study examined the impact of the removal of penalties for wrong answers on the national college entry examination in Chile.[footnote 27] It found that the policy change reduced sizable gender gaps in questions skipped, and narrowed the gender gap in test performance. In 2016, the American College Board (which develops and administers standardised tests for American higher education institutions) also removed the ‘guessing penalty’ for the SAT test.[footnote 28] The Chilean study represents a good example of an organisation changing a policy in a way that is rooted in the evidence and which addresses a disparity without undermining meritocracy or opportunity for other groups.

If organisations are serious about evidence-based D&I practice, there are compelling reasons why they should stop investing heavily in diversity training, and opt for interventions which are shown to yield intended outcomes. Journalist Zulekha Nathoo’s article[footnote 29] on ‘Why ineffective diversity training won’t go away’ argues that ineffective D&I training “endures as a way to maintain optics, legal protection and the veneer of progressive action.” If employers are given the evidence behind the efficacy and inefficacy of different interventions, their confidence to stop the use of ineffective practices may well increase as they will have an evidence-based justification for doing so.

Criteria 3: Reviewing interventions and processes regularly

Evidence suggests a lack of evaluation of D&I policies and procedures within organisations is prevalent. Gathering data and insights before designing and implementing D&I interventions is crucial in ensuring that D&I strategies are informed, precise, and achieve desired outcomes. However, this should be accompanied by evaluating the impact of interventions after the fact. Evidence-led practice allows organisations to assess whether their D&I interventions are having the desired effect, and to adapt or reverse them if they are shown to be ineffective or counterproductive.

The CIPD has noted “a concerning but recurring theme” of a “significant gap between the data that is collected and that which is reviewed by the HR director or senior leaders. many of whom expressed concern that a lot of data was being collected without a clear aim or outcome, and that the information was not being used for business decision-making.” In the CIPD’s 2023 Inclusion at Work survey,[footnote 30] about half of respondents said their organisation collects information on employee diversity but only around a quarter of business leaders said they review this data regularly. This was found to not just be a function of being a small business – even among employers of 1,000 or more employees, the research found significant gaps in the workforce data which is collected and that which is reviewed.

The need to review D&I practice has been echoed by McKinsey’s assessment of why businesses succeed.[footnote 31] In addition to using data to inform their D&I strategies, successful companies also “establish routines for monitoring progress over time; in this way, leaders can hold people accountable for desired outcomes while scaling and sustaining momentum on DEI initiatives that are working.”

Meaningfully evaluating D&I interventions entails not just evaluation of impact on the workforce, but evaluation of value for money. Private and public spending on D&I is high. For example, in November 2023 it was reported that an estimated £13 million is spent a year on D&I roles in the NHS.[footnote 32] In October HM Treasury announced a review into ‘equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI)’ spending in the Civil Service to “ensure it represents value for money for the taxpayer”.[footnote 33]

This reflects a global trend. According to Harvard Kennedy School’s Professor Iris Bohnet, US companies spend around $8 billion a year on ‘DEI’ training, with few visible positive results.[footnote 34] Additionally, McKinsey looked at the racial equity commitments from 1,369 Fortune 1000 companies from May 2021. Their analysis found that companies pledged about $340 billion to ‘driving racial equity’, $141 billion of which came between May 2021 and October 2022. While reports cite a correlation between ‘business case’ and ‘return on investment’,[footnote 35] the link is complex and direct causal relationships between interventions and inclusion, equality of opportunity, or productivity, is very hard to establish.

Despite the lack of robust evidence of the relationship between inclusion and profit, there is a consensus that diverse, inclusive workforces are ‘good for business’, thereby incentivising all and any investment in pursuit of this. However, no employer can measure value for money if data and metrics have not been integral to design and implementation, transparent, tracked, and compared objectively.

Organisational psychologist Dr Janice Gassam Asare, writing in Forbes on how to measure return on investment, explains how evaluation standards should be part of implementation.[footnote 36] She suggests that organisations must first undertake a detailed investigation of a ‘D&I culture’ to identify existing problems. Areas for improvements can then be identified, establishing precise outcomes and metrics for measuring success. She argues that only once employers can find a way to quantify such programmes will they be able to assess impact and value for money.

Our engagement insights

In all the Panel’s discussions it was clear organisations have goals to improve representation, through recruitment and retention. All recommended that any new D&I scheme should have clear guidelines about what sort of D&I data to collect, and how, in order to aid meaningful targets, progress, and comparative evaluation. Employers cited the lack of evidence-led practice in their sectors, and sought standards for quantitative data and metrics, particularly on recruitment, retention, progression, and pay. However, they also sought support in collecting and sharing usable qualitative data – for example in staff, leadership and service user surveys. Both public and private sector representatives cited the data that white working-class populations were often more disadvantaged than ethnic minority groups, though this is rarely a priority in D&I interventions.

One representative from a large public organisation explained that “data collection, reporting, and transparency has been really powerful… The power of reporting [disparities within our workforce] and the transparency is very important; and also [helps in] identifying actions that have started to make a difference”. Many agreed that large organisations can do more than SMEs with the data they have and use, and that small organisations would benefit proportionately more from transparent guidance on what data to collect, and a comparative evidence tool.

While most feedback regarding data and evidence was positive, some discussions noted that a preoccupation with data could create perverse incentives, and could encourage continuous pressure to “beat” representation statistics.

Sophisticated recruitment and retainment

Criteria 4: Widening diversity of thought and experience

Much D&I activity has focused on gender and race representation, expanding to disability, sexuality, socio-economic and neurodiversity more recently. Improvements in representation and belonging are evident in the UK, and are welcome developments. The proportion of women (aged 16 to 64) in the workforce increased between 2012 and 2023 from 66% to 72%.[footnote 37] In 2022, the ethnic minority employment rate (excluding white minority groups) was 69%, an increase of 488,000 on the previous year.[footnote 38] The disability employment rate was 54% in the 3 months to June 2023, compared to 82% for non-disabled people – an overall increase of 10 percentage points since the same period in 2013.[footnote 39]

Socio-economic diversity is increasingly recognised as a priority[footnote 40] and efforts to improve working class representation in the workforce are more common, for example from the Social Mobility Commission[footnote 41] and BBC.[footnote 42] Leading organisations should continue to explain why increasing such diversity is important. The evidence strongly indicates that homogeneity in an organisation breeds groupthink and stifles creativity and progression. Harvard Economist Paul Gompers and writer Silpa Kovvali[footnote 43] measure the impact of diversity on business success and find that social homogeneity – along traditional measures such as race and gender, but also in social background – is detrimental because “[t]hriving in a highly uncertain competitive environment requires creative thinking”. Research from Deloitte[footnote 44] found that “high-performing teams are both cognitively and demographically diverse.” They define ‘cognitive diversity’ as educational and functional diversity, as well as diversity in the mental frameworks that people use to solve problems. Apple also recognises the importance of ‘invisible’ diversity: “We take a holistic view of diversity that looks beyond usual measurements. A view that includes the varied perspectives of our employees as well as app developers, suppliers, and anyone who aspires to a future in tech. Because we know new ideas come from diverse ways of seeing things.”[footnote 45]

Our engagement insights

The theme of ‘diversity of thought’ (or lack thereof) was often cited as a significant barrier to inclusion and fairness. For example some of those we spoke to expressed concerns of being ‘discriminated against’ because their views did not align with a perceived dominant culture within their organisations. In relation to employees with beliefs perceived as not conforming with the organisational ‘consensus’, participants in the roundtables cited wrongful dismissals resulting in legal settlements, and high profile examples of lengthy investigations, bullying and harassment, and a perceived absence of employer protection. Roundtable conversations also covered a perceived lack of freedom of speech and a censorious environment, particularly in large organisations, where candid discussion of the efficacy or neutrality of D&I practice was discouraged.

Criteria 5: Restoring the importance of clear performance standards, high quality vocational training, and excellent management, as the most effective means to improve equality of opportunity, inclusion and belonging

UK businesses consistently report (to the CIPD) that their top ‘people priorities’ are recruiting employees with the skills the organisation needs (53%) and retaining the skills the organisation needs (47%).[footnote 46] These should not be in conflict with activity to improve diversity and belonging. However, the incentives towards visible, superficial, efforts in pursuit of the latter appear to be reducing focus on ‘the basics’ of good recruitment, clear standards, training, and reward. For example, in 2019 the Furlong v Chief Constable of Cheshire Police ruling[footnote 47] and 2023 Royal Air Force (RAF) enquiry[footnote 48] exposed how well-intentioned efforts to boost visible diversity can lead to unjustifiably unfair practices that amount to unlawful positive discrimination. In the USA, the Supreme Court recently overturned the practice of race-based affirmative action[footnote 49] (stating that it violated equal protection laws) after the plaintiffs alleged that the practice was discriminating against Asian Americans by requiring them to meet a higher threshold in academic and extracurricular accomplishments than other groups colleges deemed more disadvantaged. Employers should recognise that equality of opportunity will sometimes result in unequal outcomes, and disparities between individuals are not always a product of discrimination.

Current inclusion strategies in organisations focus on company culture, values and mission, providing training and support on inclusion. The less direct link, between improving vocational capabilities and improving inclusion and fair progression, is compelling though less well discussed and understood.[footnote 50]

A good D&I strategy should be devised to suit individual organisational needs. Transparent progression and high quality vocational training are likely to be better suited to improving diversity and belonging in an organisation than standalone awareness initiatives or identity networks.

Conditions for success

Condition 1: Board and CEO level direction and leadership

In all our discussions it was clear that people of all levels were concerned about D&I strategies becoming siloed in HR, with a lack of oversight and accountability from organisational leadership.

Our engagement insights

When discussing what D&I means to organisations currently and who is responsible for D&I in the workplace, roundtable participants cited the importance of senior leadership. Many participants felt that any D&I scheme or data tool would be most effective if it was understood and owned beyond HR Functions. Some expressed concerns about an ideological groupthink in HR training, and that D&I interventions and strategies would be more widely supported if part of overall corporate and business strategy.

There was consensus that senior managers need to be visible when it comes to D&I practices – to ‘show not tell’ – and ensuring senior manager and line manager capability was viewed as being vital. However, it was also noted that good practice does not mean a proliferation of written policies. Senior leadership prioritising the transmission of their own knowledge and skills, and professional development, has a positive impact on an inclusive culture.

Condition 2: Awareness and mitigation of unintended consequences

Even the most well-intentioned D&I initiatives have unintended consequences, and are rarely neutral in design. When D&I ‘goes wrong’ the cost to organisations can be considerable, in resources and reputation. A recent academic paper titled ‘How to prevent and minimise DEI backfire’[footnote 51] cites examples including a divisive Coca Cola diversity training activity suggesting employees should try to be ‘less white’ which drew significant negative media attention,[footnote 52] and the use of ‘sham’ interviews for underrepresented groups.[footnote 53][footnote 54]

Social psychologist Aarti Iyer[footnote 55] notes ‘particularly fierce’ opposition to D&I interventions which employees feel are not inclusive. She highlights the importance of initiatives that do not increase alienation and opposition from particular identity groups. Other studies have shown that pro-diversity messages from organisations can have the effect of making those who are not the targets of such messages feel concerned that they may be treated unfairly, and that those individuals can even go on to perform poorer during interviews in companies who tout ‘pro-diversity’ messages in job applications compared to those who do not.[footnote 56]

Additionally, D&I initiatives, poorly designed, can also offend those they seek to help. A 2023 study[footnote 57] found that organisations who proactively made the ‘business case’ for diversity (by linking diversity to corporate profits) made underrepresented groups less likely to apply, or feel less included. In order for their D&I interventions to be successful, organisations should ensure that concerted efforts have been made to prepare for and mitigate against unintended consequences and backfire.

Our engagement insights

It was clear from our engagement that managers want to do the right thing. Participants had a generally positive view about businesses genuinely wanting to improve equality of opportunity, fairness, and belonging. However, some feared legal action or being “cancelled” if they couldn’t point to visible initiatives, or weren’t seen to be active and vocal in generic inclusion and D&I debates. People talked about a ‘bullying’ or ‘oppressive’ response to expressing views that were deemed unpopular or raising opposition to certain beliefs and approaches to race and gender.

Many participants expressed a sense that avoiding negative PR was driving the actions they were taking (or not taking) rather than ‘what works’.

Condition 3: Applying equality law correctly

Recent high profile cases expose employers misinterpreting and misapplying equality legislation, leading to several landmark rulings. This primarily relates to employers’ interpretation of philosophical beliefs under the Equality Act 2010, as well as the positive action provisions of the Act. In addition to those cited above, the Forstater v CGD Europe and others tribunal[footnote 58] awarded over £100,000 in compensation for injury to feelings and aggravated damages, ruling that Maya Forstater’s employer had discriminated against her because of her ‘gender-critical’ beliefs – beliefs that the ruling confirmed were protected under the Act. Similarly, in what is believed to be a legal first in the UK, employment judge Kirsty Ayre ruled in 2023 that holding a view that does not subscribe to critical race theory is a protected characteristic under the “religion or belief” section of the Equality Act.[footnote 59]

The cost of misapplying equalities legislation is significant both for employers and employees (or applicants). In particular, when the offending party is a government body, this poses an avoidable cost to the taxpayer. This year[footnote 60] a Civil Service whistleblower was dismissed after raising alarms about political activism, leading to a tribunal and settlement of £100,000 by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), though the employer did not admit liability. A new staff network in the Civil Service[footnote 61] has recently been established to unite those who share concerns about political activism in the Service.

Clear and simple legal explanation and an accessible common framework for understanding equality legislation is vital. Monica Kurnatowska, Partner at Law Firm Baker McKenzie has produced a much valued guide for employers setting out 8 broad guiding principles that employers should consider in managing conflict of beliefs situations:[footnote 62]

-

The importance of freedom of speech and expression

-

There is no right not to be offended

-

Consider the context – determining whether something is objectionable will be context specific

-

Do not make assumptions about an employee’s views or what an individual might do

-

Ensure your policies are clear and employees are regularly given training that all beliefs are treated equally

-

The importance of even-handed leadership

-

The need to handle complaints with care

-

Take a balanced approach

The Panel endorses this, and recommends the EHRC produces similar.

Engagement insights

Confusion and lack of clarity surrounding employer and employee obligations was a core theme of our discussions, particularly in relation to gender. Many people expressed fear of misinterpreting and/or misapplying the law due to “poor clarity within the legislation”, and unclear guidance. Those with expertise in equality law expressed concern that some organisations, in an attempt to go ‘above and beyond’ the law in their D&I efforts (with good intentions) were actually breaking the law. Increasingly, issues of freedom of speech and expression affect D&I debates. Participants mentioned fear of legal action, and that the definitions of bullying, harassment and discrimination are becoming ‘weaponised’ in employment grievances and pre-emptive HR or legal advice.

During our engagement, the Free Speech Union (FSU) – which supports and advises individuals who believe their right to free speech has been curtailed, often by their employer – told us of dozens of cases (past and present) involving potential misapplication of equalities law, and D&I practice employees deemed exclusionary or discriminatory.

Reviewing the case for an ‘Inclusion Confident Scheme’

Action 72 of Inclusive Britain committed the government to developing a new, voluntary Inclusion Confident Scheme, based on the work of the Panel. In endeavouring to establish how a new scheme might most effectively add value, rather than duplicate other similar initiatives, we assessed a wide range of pre-existing inclusion schemes and kitemarks (some prominent examples of which are listed below). These are available for organisations to join voluntarily and span a wide range of areas. Some are specific to certain characteristics, such as the Disability Confident Scheme and the Race at Work Charter. Others, such as the Inclusive Employers Standard, are generalist. We have considered the remit, reach, and format of many such schemes in determining where the gaps lie, and how (if at all) another scheme or tool might be useful.

Disability Confident Scheme

Remit

The Disability Confident scheme supports employers to make the most of the talents disabled people can bring to the workplace.

Scheme members have free access to guidance, peer support groups and specialist events to give them the skills and confidence to employ disabled people. Members also receive accreditation when they join the scheme, including a certificate and Disability Confident badge to use on their website and in recruitment adverts.

Reach

Targeted at employers who are recruiting disabled employees.

As of September 2023, 18,902 employers have signed up to the scheme.

14,223 – Level 1

4,129 – Level 2

550 – Level 3

Format

A free service. Three levels and employers must complete one before moving up the levels.

Level 1 – Disability Confident Committed – employer must agree to the Disability Confident commitments and identify at least one action that they will carry out.

Level 2 – Disability Confident Employer – employer self-assesses their organisation around 2 themes; getting the right people for their business and keeping and developing their people. Having confirmed they have completed their online self-assessment, the employer is registered as a Disability Confident Employer for 3 years.

Level 3 – Disability Confident Leader – employer has their self-assessment validated by someone outside of their business, provide a short narrative to show what they have done or will be doing to support their status as a Disability Confident Leader, confirm they are employing disabled people and report on disability, mental health and wellbeing, by referring to the Voluntary Reporting Framework.

Investors in People

Remit

Investors in People assess how organisations perform against their “We invest in people” framework. They provide advice and support on how to improve workplace culture over time specifically in areas around employee engagement, communication, organisational culture and work practices. Three basic principles – plan, do and review.

Reach

Recognised in 66 countries, with over 50,000 accredited organisations.

Format

Paid for service. Three year accreditation (one year available for organisations with 10 or less people).

Standard, Silver, Gold and Platinum award levels.

Race at Work Charter

Remit

Led by Business in the Community (BiTC), the Charter asks businesses to make a public commitment to improving equality of opportunity in the workplace. In 2017 BITC’s Race at Work 2018: The Scorecard Report was published one year after the McGregor-Smith Review to look at how UK employers performed against the recommendations outlined in the review.

The findings led BITC to create the Race at Work Charter, with 5 calls to action to improve race equality, inclusion and diversity in the workplace.

Reach

1,020 signatories as of October 2023.

Format

Free to sign. Seven calls to action to ensure that ethnic minority employees are represented at all levels in an organisation:

-

Appoint an Executive Sponsor for race.

-

Capture ethnicity data and publicise progress.

-

Commit at board level to zero tolerance of harassment and bullying.

-

Make clear that supporting equality in the workplace is the responsibility of all leaders and managers.

-

Take action that supports ethnic minority career progression.

-

Support race inclusion allies in the workplace.

-

Include Black, Asian, Mixed Race and other ethnically diverse-led enterprise owners in supply chains.

Inclusive Employers Standard

Remit

Evidence-based workplace accreditation tool for inclusion and diversity.

The IES highlights to people and stakeholders that inclusion is integral to the organisation and that the organisation understands the business case for inclusion and diversity.

Reach

65 organisations are accredited through this scheme.

Format

Paid for service. Participants answer 35 questions that cover all the protected characteristics and wider inclusion themes and submit evidence to support the answers.

They use the responses to measure inclusion and diversity within an organisation and assess where organisations are on their journey.

The questions are divided across 6 pillars of inclusion, that measure all areas of inclusion activity. Employers then receive a bronze, silver or gold accreditation and bespoke, action-focused feedback.

National Centre for Diversity Accreditation

Remit

The National Centre for Diversity Accreditation offers a 3-level accreditation:

-

Investors in Diversity Award

-

Leaders in Diversity Award

-

Masters in Diversity Award

Reach

Over 900 accredited organisations (not clear)

Format

Three levels. 7 steps to gain accreditation include:

-

Organisations get assigned a dedicated NCFD Advisor and a Personal Relationship Manager.

-

Cultural audit – The next step is a cultural audit to establish where the organisation is currently in terms of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, and where it wants to be.

-

Feedback – Advisors discuss the results of the cultural audit and report the key findings.

-

Building a bespoke action plan and next steps – Using the results of the audit, advisors create a detailed plan.

-

Continuous support and improvement – advisors will work with organisations to build on and embed the recommendations from the action plan.

-

Evaluation – advisors then re-audit the organisation to evidence that it has achieved the recommendations from the action plan.

-

Achieving the accreditation – After achieving the Investors in Diversity Award, organisations can display the achievement on all of their corporate communications.

Women in Finance Charter

Remit

This is a commitment by HM Treasury and signatory firms to work together to build a more balanced and fair industry. Firms that sign up to this Charter are pledging to be the best businesses in the sector.

The Charter reflects the government’s aspiration to see gender balance at all levels across financial services firms.

Reach

As of June 2023, there have been over 400 signatories.

Format

To complete the Charter, organisations must commit to implementing the recommendations in the Empowering Productivity: Harnessing the talents of women in financial services review. This was published in March 2016 and makes 4 recommendations to industry to improve gender diversity, which have received widespread support from the sector. Organisations commit to:

-

Appointing one member of the senior executive team who is responsible and accountable for gender diversity and inclusion.

-

Setting and publishing internal targets for gender diversity in senior management.

-

Publishing progress annually against these targets in reports on their website.

-

Having an intention to ensure the pay of the senior executive team is linked to delivery against these gender diversity targets.

Education Endowment Foundation toolkit

In addition to the above inclusion schemes and kitemarks, the Panel also considered the Education Endowment Foundation[footnote 63] (EEF) tool for teaching and learning practices. The EEF is an independent charity supporting teachers and school leaders to use evidence of what works – and what doesn’t – to improve educational outcomes, especially for disadvantaged children and young people. It does this by:

- summarising evidence – working with an academic partner which reviews the best available evidence on teaching and learning, and presenting this in an accessible way for educators

- finding new evidence – funding independent evaluations of programmes and approaches that aim to raise the attainment of children and young people from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds

- putting evidence to use – supporting education practitioners, as well as policymakers and other organisations, to use evidence in ways that improve teaching and learning

The EEF toolkits:

- are based on real life data about what has happened when particular approaches have been used in schools before

- do not make definitive claims as to what will work to improve outcomes in a given school – rather, they provide high quality information about what is likely to be beneficial based on existing evidence – ‘best bets’ for what might work in organisations’ own context

- are not designed to be used in isolation because they do not give definitive answers – professional judgement and expertise is needed to move from the information in the toolkit to an evidence-informed decision about what will work best in schools

Together, the toolkits present, in an accessible digital format, over 40 approaches and interventions for improving teaching and learning. Each intervention is rated according to:

- its average impact on attainment (efficacy)

- the strength of the research evidence supporting it (the number of robust studies evaluating that intervention)

- its cost

Both toolkits are live resources that are updated on a regular basis as new findings from high-quality research, including EEF-funded projects, become available.

How the toolkit synthesises the latest evidence

The Teaching and Learning Toolkit pulls together a large amount of academic evidence that would otherwise sit behind academic paywalls. To avoid selecting only positive or well known studies, the toolkit uses systematic review. This means that the criteria for the inclusion of research studies in the toolkit is specified in advance. Any study that meets the criteria is included, irrespective of whether it shows efficacy or inefficacy for a particular intervention. In other words, the inclusion criteria is neutral – studies are included because they are methodologically robust, not because they are supportive of researchers’ preferences. This means that researchers cannot exclude a study just because they ‘don’t like’ the results.

The EEF works with Durham University on research, data extraction, and analysis, to ensure the tool itself is robust. Separate from the tool (but to be used alongside it), are the guidance reports and case studies, prepared and promoted by the EEF.

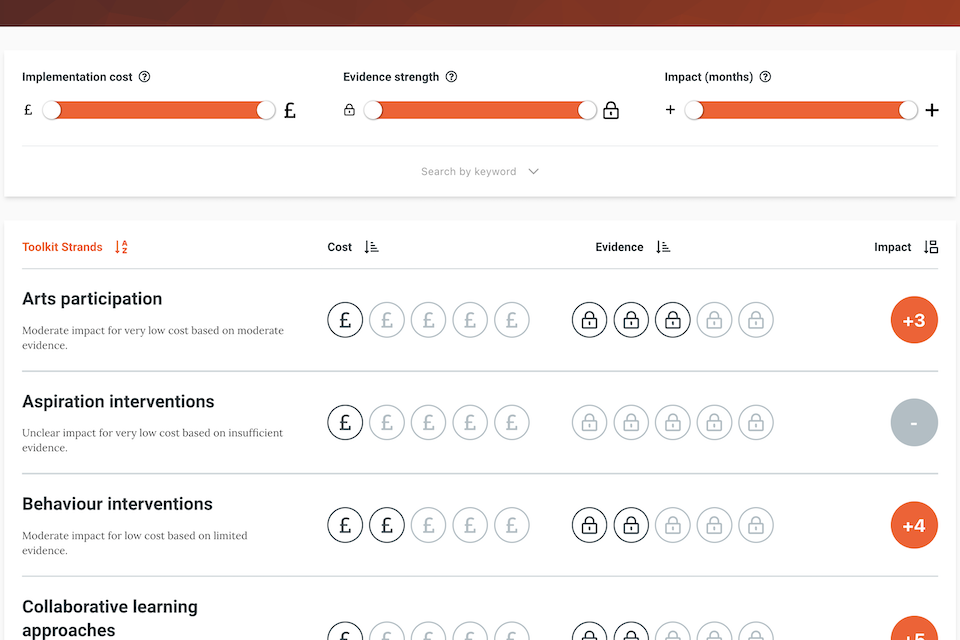

Figure 1 shows how this synthesised and systematised evidence is presented to users. Toolkit users who want to understand the efficacy and strength of evidence of various educational interventions can filter these interventions by 3 indicators: impact, evidence strength, and implementation cost.

Figure 1: Snapshot of the digital EEF toolkit

Screenshot: the EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit.

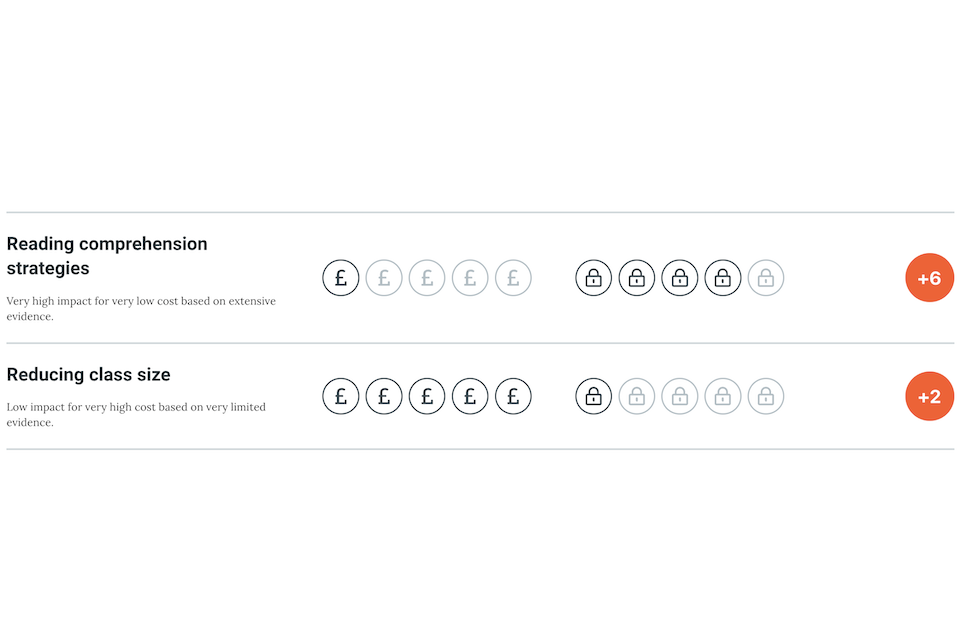

To further elucidate the comparative function of the tool, Figure 2 below gives an example of 2 interventions within the toolkit – reading comprehension strategies and reducing class size. The toolkit indicates that on one hand, reading comprehension strategies are a ‘very low cost’, ‘very high impact’ intervention for which there is ‘extensive evidence’, while reducing class sizes is a ‘very high cost’, ‘low impact’ intervention with ‘very limited evidence’. This clear comparative format allows educators to make evidence-based judgements about which interventions are more worthwhile than others, given the latest evidence and given their own context.

Figure 2: Two interventions compared

Screenshot: the EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit.

The Panel’s Secretariat met the EEF to discuss how the tool was designed and developed, how the framework has evolved, and general lessons we might learn. There are many parallels between evidence-based practice in teaching and workplace inclusion, for example many time-poor teams and managers, and a well-resourced activist and commercial sector providing training. The Panel believes the EEF toolkit is clear, highly practical, easy-to use, and the methodology used in assessing and categorising each intervention is robust and impartial.

A D&I evidence tool

The Panel recommends the government funds the design and maintenance of a tool to synthesise evidence of impact and value for money of workplace D&I interventions, based on the EEF model. Over time, as with the EEF tool in teaching, this will give all leaders and managers in every sector access to evaluation rigour. It will also ‘nudge’ commercial or activist providers of interventions to be transparent and prove impact.

Such a tool would build on the criteria outlined above, and support employers and procurers and practitioners of D&I efforts to assess the strength of evidence, efficacy, and cost of implementation of interventions. In support of the tool, and to explain and promote its purpose and operation, the Department for Business and Trade might run a series of engagement conversations, and work with and through business representative groups and influential leaders. The EHRC might also use the design and existence of an evidence tool to explain how organisations can meet statutory duties in the Equality Act. As with the EEF evidence assessment tool, the quality and impact of D&I interventions which draw on its data should improve over time.

Metrics and measures

An Inclusion Confident tool should use similar metrics to the EEF: strength of evidence, cost of implementation and impact (based on case studies from organisations who have used the intervention).

The methodology and specific measures would be decided in collaboration with a research partner. This would include how to measure the strength of evidence and impact, which metrics to use, and how to systematically present comparisons between interventions in a business-friendly, accessible format.

Recommendations

We recommend that:

1. The government endorses a new framework (outlined in ‘Recommended framework for D&I success’) which sets out criteria employers might apply to their D&I practice to embed effectiveness and value for money.

The framework is intended to act as a set of conditions and expectations employers should strive to meet to embed good D&I practice, putting evidence at the heart of their activities. The government – with the Department for Business and Trade and Equality Hub leading – should promote these in future engagement work it undertakes, and any future guidance and tools it produces for organisations both public and private. Advice on how employers can meet these criteria should also feature in a new, government-backed D&I evidence tool for businesses.

2. The government funds, and works with, a research partner to develop a digital tool similar to the EEF’s ‘Teaching and Learning Toolkit’.[footnote 64] This will allow all leaders and managers in every sector to assess the rigour, efficacy, and value for money of a range of D&I practices. It will also ‘nudge’ commercial or activist providers of interventions to evaluate and prove impact.

The digital tool should synthesise and summarise evidence on various D&I practices and interventions in a plain-English, business friendly format. At the minimum, the tool should include a measure for the strength of evidence behind different interventions, and for the impact those measures have been shown to have in previous research. The research partner should establish how best to reflect other useful metrics (for example, cost) that could support organisations in making informed decisions about different D&I interventions to implement. The tool should also feature case studies of effective practice.

3. The EHRC explains and clarifies the legal status for employers in relation to D&I practice, with particular focus on the implication of recent rulings for HR policies and staff networks.

In particular, the guidance should make clear organisations’ legal duties and responsibilities relating to the protected characteristic of ‘belief’ – and the risks and implications of failure to carry out these duties. It should highlight recent legal cases, and set out a number of guiding principles to help employers manage situations where conflicts of belief arise in the workplace. The government should also further promote the April 2023 guidance Positive Discrimination in the Workplace[footnote 65] and committing to regularly updating guidance to reflect relevant rulings to ensure that all employers’ understand how to correctly interpret and apply the positive action provisions of the Equality Act 2010.

-

UK Government (2022) Inclusive Britain: government response to the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities ↩

-

We use ‘D&I’ throughout as a common, widely understood label for workplace diversity and inclusion activities. There are many acronyms and shorthands in use (DEI, Inclusion), all of which are evolving and contested. ↩

-

Education Endowment Foundation (2023) Teaching and Learning Toolkit ↩

-

Gompers, P. and Kovvali, S. (2018) The Other Diversity Dividend, Harvard Business Review ↩

-

Bourke, J. (2018) The diversity and inclusion revolution: Eight powerful, Deloitte ↩

-

Anderson, B. M. (2020) Why the Head of Diversity is the Job of the Moment, LinkedIn ↩

-

Conservative Way Forward (2022) Defunding Politically Motivated Campaigns ↩

-

Kirkland, R. and Bohnet, I. (2017), Focusing on what works for workplace diversity, McKinsey & Company ↩

-

Minow, M. (2021), ‘Equality vs. equity’, American Journal of Law and Equality,1, pp.167-193 ↩

-

CIPD (2022) Equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in the workplace ↩

-

Minow, M. ‘Equality vs. equity’, American Journal of Law and Equality (2021), 1:167–193 ↩

-

Employment Tribunal, HM Courts & Tribunal Services (2020) M Forstater v CGD Europe and others: 2200909/2019 ↩

-

Employment Tribunal, HM Courts & Tribunal Services (2019) Mr M Furlong v The Chief Constable of Cheshire Police: 2405577/2018 ↩

-

Beale, J. (2023), ‘RAF diversity targets discriminated against white men’, BBC News ↩

-

CIPD (2022), Inclusion at Work 2022: Findings from the inclusion and diversity survey ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Williams, JC. and Dolkas, J. (2022), ‘Data-Driven Diversity’, Harvard Business Review ↩

-

Zheng, L. (2023), ‘How to Effectively — and Legally — Use Racial Data for DEI’, Harvard Business Review ↩

-

Jan Shelly Brown, J.S., et al. (2023), ‘It’s (past) time to get strategic about DEI’, McKinsey & Company ↩

-

CIPD (2022), Inclusion at Work 2022: Findings from the inclusion and diversity survey ↩

-

Financial Conduct Authority (2022), ‘Understanding approaches to D&I in financial services’ ↩

-

Urwin, P., et al. (2013), ‘The business case for equality and diversity: A survey of the academic literature.’ ↩

-

Paluck, E.L. and Green, D.P. (2009) ‘Prejudice reduction: What works? A review and assessment of research and practice’. Annual review of psychology, 60, pp.339-367. ↩

-

Al-Gharbi, M. (2020), ‘Diversity is Important. Diversity-Related Training is Terrible.’ ↩

-

Kalev, A. and Dobbin, F. (2020), ‘Does Diversity Training Increase Corporate Diversity?’, Regulation Backlash and Regulatory Accountability. ↩

-

Baldiga, K., (2014), ‘Gender differences in willingness to guess’, Management Science, 60(2), pp.434-448 ↩

-

Coffman, K.B. and Klinowski, D. (2020), ‘The impact of penalties for wrong answers on the gender gap in test scores’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(16), pp.8794-8803. ↩

-

The Princeton Review (Unknown date), ‘Should You Guess on the SAT and ACT?’ ↩

-

Nathoo, Z. (2022), ‘Why ineffective diversity training won’t go away’, BBC, 17 June ↩

-

CIPD (2023), Effective Workplace Reporting: Improving people data for business leaders ↩

-

Jan Shelly Brown, J.S., et al. (2023), ‘It’s (past) time to get strategic about DEI’, McKinsey & Company ↩

-

Somerville, E (2023), NHS chiefs told to cut woke roles as diversity tsars still cost £13m a year, the Telegraph, 11 Nov. ↩

-

HM Treasury (2023), ‘End to Civil Service expansion and review of equality and diversity spending announced in productivity drive’, 2 Oct. ↩

-

Bohnet, I. (2017), Focusing on what works for workplace diversity, McKinsey & Company, 17 Apr. ↩

-

Adams, D. (2022) Harnessing The Power Of Diversity For Profitability, Forbes, 3 Mar. ↩

-

Asare, J. (2018), How To Measure The ROI Of Diversity Programs, Forbes, 21 Dec. ↩

-

Office for National Statistics (2023), Female employment rate ↩

-

Race Disparity Unit, Ethnicity Facts and Figures, Employment ↩

-

Department of Work and Pensions (2023), Employment of Disabled People 2023 ↩

-

Elsässer, L. and Schäfer, A., (2022). ‘(N)one of us? The case for descriptive representation of the contemporary working class’, West European Politics’, 45(6), pp.1361-1384 ↩

-

Social Mobility Commission (2020) Socio-economic diversity and inclusion ↩

-

BBC Workforce Diversity and Inclusion Strategy (2021-2023) Diversity and Inclusion Plan ↩

-

Gompers, P. and Kovvali, S. (2018) The Other Diversity Dividend, Harvard Business Review ↩

-

Deloitte (2019) The diversity and inclusion revolution: Eight powerful truths, Deloitte Review, issue 22 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Employment Tribunal, HM Courts & Tribunal Services (2022) M Forstater v CGD Europe and others: 2200909/2019 ↩

-

Employment Tribunal, HM Courts & Tribunal Services (2019) Mr M Furlong v The Chief Constable of Cheshire Police: 2405577/2018 ↩

-

BBC News (2023) RAF diversity targets discriminated against white men ↩

-

BBC News (2023) Affirmative action: US Supreme Court overturns race-based college admissions ↩

-

Adrian Wooldridge (2021) The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World ↩

-

Burnett L, Aguinis H (2023) How to prevent and minimize DEI backfire, George Washington School of Business ↩

-

Brenmer, J (2021) Coca-Cola faces backlash over seminar asking staff to ‘be less white’, The Independent, 24 Feb. ↩

-

Portocarreo S (2022) Diversity initiatives in the US workplace: A brief history, their intended and unintended consequences ↩

-

Hyde S, White M, Casper W (2023) What About Me? When Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Efforts Result in Unintended Outcomes, The Global Human Resource Management Casebook ↩

-

Iyer, A. (2016) ‘Understanding advantaged groups’ opposition to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies: The role of perceived threat’, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16(5), p.e12666. ↩

-

Dover, TL. et al. (2016), ‘Members of high-status groups are threatened by pro-diversity organizational messages’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 62, pp. 58-67 ↩

-

Georgeac OAM, Rattan A (2023) The business case for diversity backfires: Detrimental effects of organizations’ instrumental diversity rhetoric for underrepresented group members’ sense of belonging, National Library of Medicine ↩

-

Employment Tribunal, HM Courts & Tribunal Services (2020) M Forstater v CGD Europe and others: 2200909/2019 ↩

-

Dathan, M (2023) Law protects opposition to critical race theory, Judge rules, The Times, 29 Sept. ↩

-

Clarence-Smith, E (2023) Civil servant who blew the whistle on political activism wins £100,000 settlement, The Telegraph, 27 May. ↩

-

Cabinet Office (2023) SEEN Network ↩

-

Kurnatowska, M (2023) Conflicts of belief in the workplace: forging a path, Baker McKenzie, 24 Aug. ↩

-

Education Endowment Foundation How we work ↩

-

Education Endowment Foundation (2023) Teaching and Learning Toolkit ↩

-

Equality Hub (2023) Positive Action in the Workplace ↩