HPR volume 9 issue 40: news (13 November)

Updated 29 December 2015

1. Use of genomics in salmonella outbreak surveillance

PHE’s Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit (GBRU) has been implementing the use of whole genome sequencing (WGS) for identifying and characterising salmonella isolates since April 2014. The initial step involves Multi Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) to assign each isolate a profile or sequence type that correlates closely to traditional serotype, allowing backward compatibility. This method has, since April 2015, replaced most of the serotyping for routine identification of salmonella species. The second step involves the comparison of the isolate’s full genome to an appropriate reference genome to identify individual nucleotide differences (single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs). The assigned SNP address for each isolate is then added to a secure Gastro Data Warehouse and used to identify clusters of cases and, if available, food isolates that have the same SNP address. Clusters of interest are further investigated by generating phylogenetic trees, to take advantage of the unparalleled information obtained with WGS. Due to the sequential nature of mutational drift, phylogenetic methods can be used to study variation in genomes and reveal ancestral relationships.

The use of WGS is proving to be particularly useful in detecting outbreaks of genetically monomorphic clones such as Salmonella Enteritidis, excluding unrelated cases within the same phage type, providing case definitions and refining outbreak investigations to increase the chances of identifying a common source exposure. This enhanced ability to identify and effectively investigate outbreaks resulted in implementation of appropriate risk mitigation measures in two recent cases: the Salmonella Enteritidis phage type (PT) 14b outbreak in 2014 [1], and a Salmonella Enteritidis outbreak earlier this year linked to snake ownership [2]. Most significantly, without the use of WGS, the latter example would not have been identified as an outbreak – and the subsequent epidemiological investigation linking the Salmonella Enteritidis cluster to contaminated mice used for reptile feed, and the publication of targeted public health advice by PHE, would not have occurred.

The high resolution WGS typing of isolates at a national level is facilitating the improved detection of smaller or geographically scattered clusters and PHE’s Gastrointestinal Infections Department and GBRU are now developing cluster detection and reporting methods which will allow appropriate and timely investigation of such clusters. Time, size and genetic variation are being taken into account and clusters are being assessed, within the GI department initially, with the aim of developing an automated reporting system in future to initiate appropriate epidemiological investigation.

Further information about these techniques, including explanation of how genomics can be applied to support public health, is available from the e-learning module at: http://public-health-genomics.phe.org.uk/.

Assistance with the use of whole genome sequencing data is available from PHE’s Gastrointestinal Infections Department and the Gastrointestinal Bacterial Referencing Unit.

1.1 References

- Inns T, Lane C, Peters T, Dallman T, Chatt C, McFarland N, Crook P, et al, on behalf of the outbreak control team (2015). “A multi-country Salmonella Enteritidis phagetype 14b outbreak associated with eggs from a German producer: near real-time application of whole genome sequencing and food chain investigations, United Kingdom, May – September 2014”. Euro Surveill. 20(16).

- Carrion I [presenter], Kanagarajah S, Awofisayo-Okuyelu A, Ashton P, Dallman T, Hawker J, et al (2015). ‘Uncovering the scale of a reptile associated salmonellosis outbreak in the United Kingdom (UK) 2015: a recent history’. Presentation at the European Scientific Conference on Applied Infectious Disease Epidemiology (ESCAID)”.

2. Quarterly update on enteric fever in EW&NI

PHE’s latest quarterly report summarising the epidemiology of enteric fever across England, Wales and Northern Ireland is published in the Infection Reports section of this issue of HPR [1].

The report includes analysis of the data according to organism type, age/sex and geographical distribution of cases, and travel history of cases.

The data shows a decline in case reports compared with the equivalent period in 2014, and compared with the mean number of reports over the past eight years.

2.1 Reference

3. Impact of changing nature of injecting drug use on infections in the UK

The thirteenth annual report on infections among people who inject drugs (PWID) in the United Kingdom – Shooting Up – has been published by Public Health England [1].

PWID are vulnerable to a wide range of infections – including those caused by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B and C, and bacteria such as Clostridium Botulinum and Staphylococcus Aureus – that can cause significant morbidity and mortality. The report examines the extent of infections and the associated risks among PWID under five headings.

3.1 Changing patterns of psychoactive drug injection are increasing risk

Heroin, alone or in combination with crack-cocaine, remains the most commonly injected psychoactive drug. However, there is evidence of an increase in the injection of stimulants, including recently emerged psychoactive drugs such as mephedrone. Over the past decade, the number of people reporting that amphetamines and amphetamine-type drugs are their main drug of injection has increased three-fold. One in eight now say these are the main drug they inject.

Overall, needle and syringe sharing among those currently injecting psychoactive drugs has fallen from 28% in 2004 to 17% in 2014. However, people injecting stimulants report much higher levels of risk behaviours such as sharing and re-using needles and syringes. Higher levels of risk behaviours associated with the use of stimulants can increase harm, and increased rates of stimulant injection has been a factor in a number of infections outbreaks among PWID in other countries.

3.2 Bacterial infections continue to be a problem

Around a third (31%) of those who inject psychoactive drugs reported having a symptom of an injecting site infection during the preceding year. Outbreaks of infections due to bacteria, such as Clostridium Botulinum, continue to occur in this group. Some of these infections are severe and place substantial demands on healthcare. Half of those with hepatitis C remain unaware of their status.

Hepatitis C remains a major problem among PWID in the UK, with around half of those who inject psychoactive drugs having antibodies to hepatitis C. Data indicate that hepatitis C transmission is probably stable in this group and further effort is needed to reduce this. Although the uptake of diagnostic testing is high (83%), about half of the hepatitis C infections remain undiagnosed – either because people have never had a test or have become infected since their last test. Those PWID with undiagnosed hepatitis C typically make use of a range of health services. This underlines the need to identify, and make use of, the opportunities for regularly offering tests to those at risk.

3.3 Hepatitis B remains rare but vaccine uptake has stopped improving

Less than 1% of those who inject psychoactive drugs are currently infected with hepatitis B. The proportion ever infected with hepatitis B has fallen from 28% in 2004 to 14% in 2014. This public health success reflects a marked increase in the uptake of the vaccine against hepatitis B during the 2000s. In 2014, 72% reported vaccination uptake – this was lower than the uptake seen in 2011 (76%) and indicates that uptake may now be declining. Most of those who have not been vaccinated have been in contact with health services where they could have received a dose of the vaccine.

3.4 HIV levels remain low overall and the uptake of care is good

HIV infection among PWID remains rare in the UK compared with many other countries. Only 1% of those who inject psychoactive drugs have HIV, and overall HIV incidence is currently low among PWID. Most of those infected with HIV are aware of their infection and are accessing care. The low overall prevalence in this group probably reflects the extensive provision of needle and syringe programmes, opioid substitution therapy and other drug treatment since the 1980s. The recent outbreak of HIV among PWID in Glasgow is a concern.

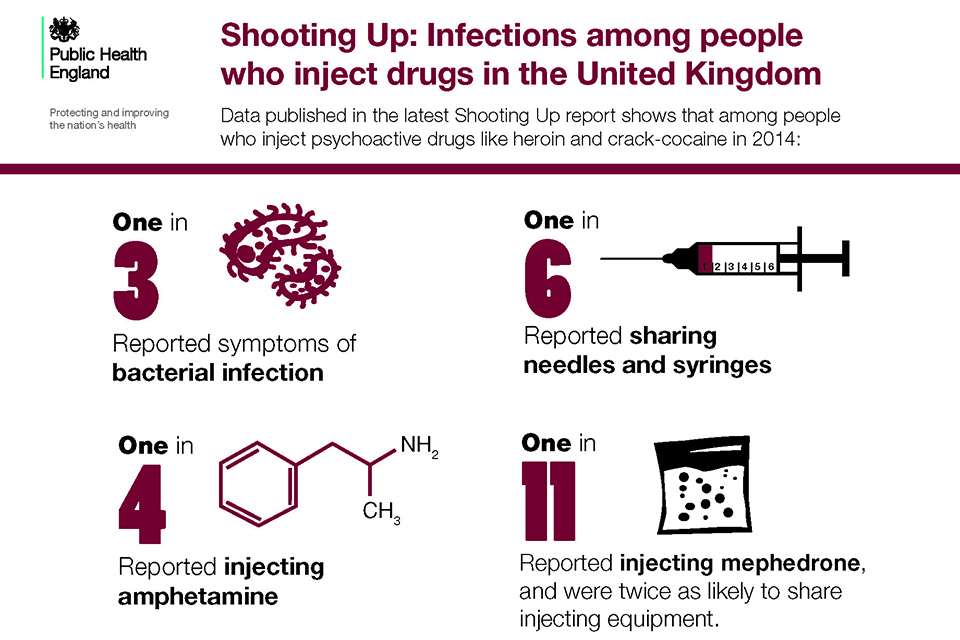

Key facts about the risk behaviours of those injecting psychoactive drugs are presented in an infographic associated with the new report (see extract below), highlighting the fact that, among people who were injecting psychoactive drugs in 2014: one in three reported symptoms of bacterial infection, one in four reported injecting amphetamines, and one in six reported sharing needles and syringes. The one in 11 who reported injecting mephedrone were twice as likely to share injecting equipment.

Shooting Up inforgraphic [Source: Infographic “Shooting Up: infections among people who inject drugs in the UK” illustrating aspects of the data contained in the new report, with particular reference to those who inject psychoactive drugs (heroin, crack-cocaine, etc). See Shooting Up webpages (reference 1).]

The findings presented in the report indicate a need to maintain, and improve services that aim to reduce injecting-related harms and to support those who want to stop injecting. A range of services, including locally appropriate provision of needle and syringe programmes, opioid substitution treatment, and other drug treatment, should be provided. In addition, there should be easy access to diagnostic testing for hepatitis C and HIV (including access to care pathways for those living with these infections), to vaccinations including that for hepatitis B, and to information and advice on safer injecting practices, on preventing infections and on the safe disposal of used equipment. These services should be developed in line with published guidelines [2,3,4,5] to ensure that the interventions they provide have sufficient coverage to prevent infections.

3.5 References

- PHE, Health Protection Scotland, Public Health Wales and Public Health Agency Northern Ireland (November 2015). “Shooting Up: infections among people who inject drugs in the UK, 2014”. For related documents, see Shooting Up webpages.

- Department of Health (2007). “Drug misuse and dependence – guidelines on clinical management: update 2007”.

- NICE (July 2007). Drug misuse: psychosocial interventions Clinical Guideline CG51.

- NICE (July 2007). Drug misuse: opioid detoxification Clinical Guideline CG52.

- NICE (March 2014). Needle and syringe programmes: providing people who inject drugs with injecting equipment Public Health Guidance, PH52.