Health matters: community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing

Published 28 February 2018

Summary

This professional resource focuses on the concept and practice of community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing and outlines how to create the conditions for community assets to thrive.

Why work with communities?

What does ‘community’ mean?

‘Community’ as a term is used as shorthand for the relationships, bonds, identities and interests that join people together or give them a shared stake in a place, service, culture or activity.

Distinctions are often made between communities of place or geography and communities of interest, identity or affinity, as strategies for engaging people may vary accordingly. Nevertheless, communities are dynamic and complex, and people’s identities and allegiances may shift over time and in different social circumstances.

Community determinants underpin health and wellbeing

Positive health outcomes can only be achieved by addressing the factors that protect and create health and wellbeing and many of these are at a community level.

Community life, social connections and having a voice in local decisions are all factors that have a vital contribution to make to health and wellbeing. These community determinants build control and resilience and can help buffer against disease and influence health-related behaviour.

Involving and empowering local communities, and particularly disadvantaged groups, is central to local and national strategies in England for both promoting health and wellbeing and reducing health inequalities. Participatory approaches can directly address marginalisation and powerlessness that underpin inequities and can therefore be more effective than professional-led services in reducing inequalities.

As well as having health needs, all communities have health assets that can contribute to the positive health and wellbeing of its members, including:

- the skills, knowledge, social competence and commitment of individual community members

- friendships, inter-generational solidarity, community cohesion and neighbourliness

- local groups and community and voluntary associations, ranging from formal organisations to informal, mutual aid networks such as babysitting circles

- physical, environmental and economic resources

- assets brought by external agencies including the public, private and third sector

Infographic - what are community health assets?

Recognising assets helps value community strengths and ensure everyone has access to them. It builds on the positives and ensures that health action is co-produced equally between communities and services.

Community-centred ways of working are important for all aspects of public health, including health improvement, health protection and healthcare public health. It’s not about expecting communities to do more and saving public money but about investing in more sustainable and effective approaches to reduce health inequalities.

The picture across England

The Community Life Survey is a survey of adults aged 16 and above in England, which is held annually to track trends across areas that are central to encouraging social action and empowering communities, such as:

- volunteering and charitable giving

- neighbourhood (views about the local area, community cohesion and belonging)

- civic engagement and social action

- wellbeing

This nationally representative survey provides data on behaviours and attitudes to inform policy and action in these areas.

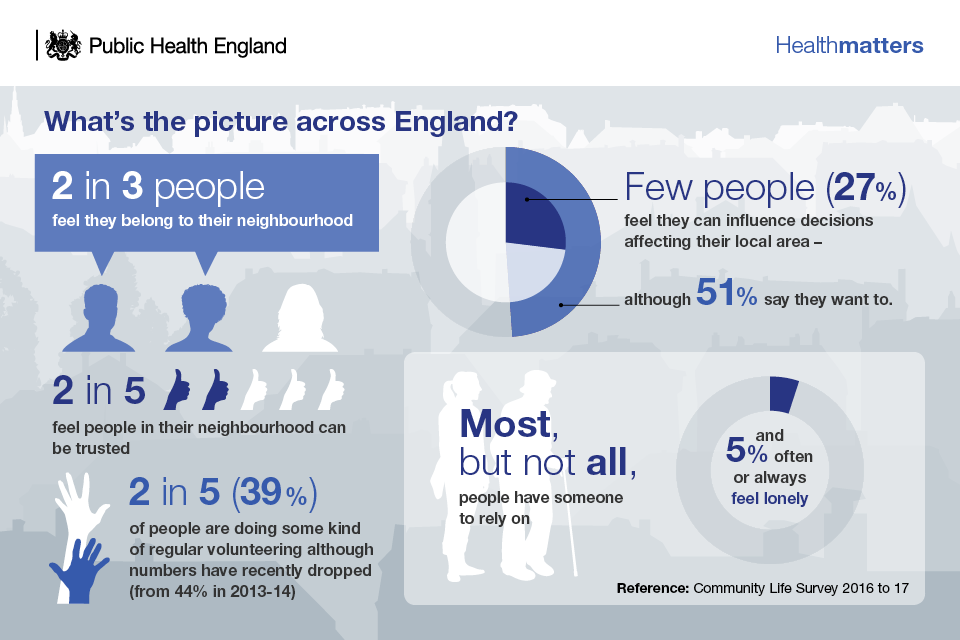

The findings of the Community Life Survey 2016 to 2017 indicate the picture across England in terms of people’s feelings towards their communities and their role within them. In 2016 to 2017, 2 in 3 people said they feel they belong to their neighbourhood and 2 in 5 feel people in their neighbourhood can be trusted.

In terms of volunteering, 2 in 5 people (39%) are engaging in some kind of regular volunteering. However, levels of volunteering have decreased between 2013 to 2014 and 2016 to 2017, with the proportion of adults who had engaged once a month falling from 44% to 39% in this period.

Regarding community decisions, in 2016 to 2017, 27% of respondents agreed they could personally influence decisions affecting their local area. This has remained fairly consistent since 2013 to 2014 when 26% agreed with this statement. Despite this figure, 51% said they would like to be more involved in decisions made by their local council.

Infographic - people's views on involvement with their neighbourhood

Lastly, the survey reported on the proportion of adults who felt lonely often or always, which has remained unchanged since collection began in 2013 to 2014 at 5%. Most, but not all, people have someone to rely on and in 2016 to 2017, over half (54%) stated they felt lonely hardly ever or never.

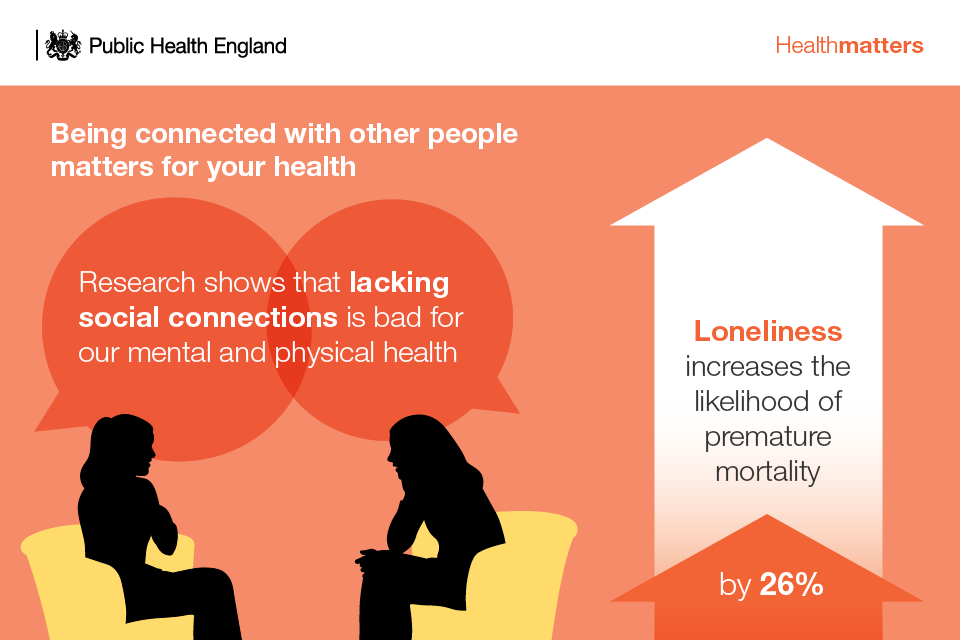

Infographic - being connected with other people matters for your health

What the evidence says

Health inequalities persist and many people experience the effects of social exclusion or lack social support. The Marmot Review provided evidence that in order to reduce health inequalities in England we need to improve community capital and reduce social isolation across the social gradient.

How people experience social relationships influences health inequities. Critical factors include how much control people have over resources and decision-making and how much access people have to social resources, including social networks, and communal capabilities and resilience.

(UCL Institute of Equity, 2013)

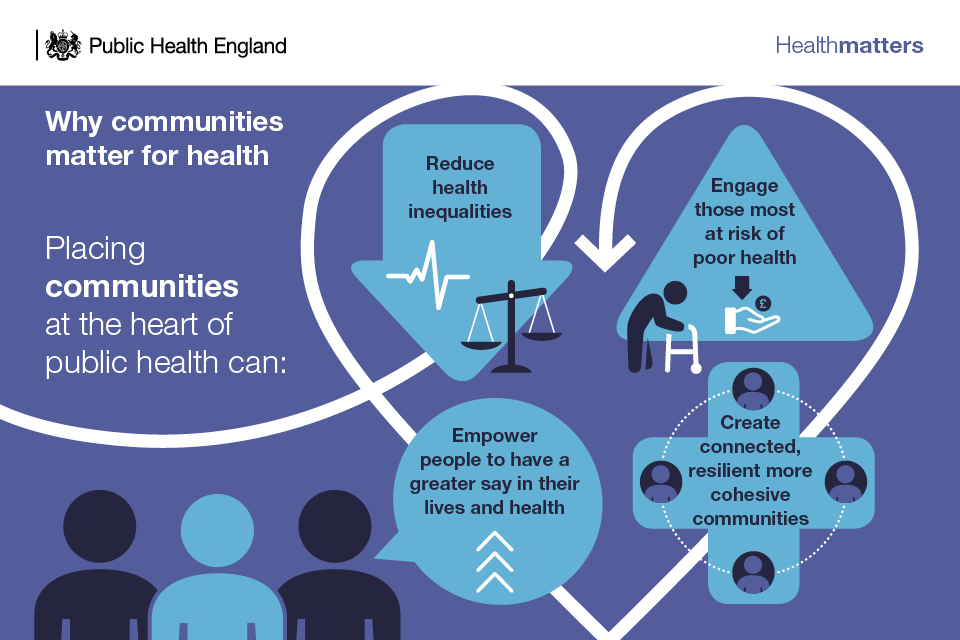

Infographic - why communities matter for health

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance reiterates the importance of community engagement as a strategy for health improvement, particularly as it leads to services that better meet the community members’ needs. The NICE community engagement quality standard is useful for commissioning community approaches.

Community-centred approaches are also important for health and social care services. The NHS Five Year Forward View sets out how our health services need to change and argues for a new relationship with patients and communities. There is a shared commitment across national agencies to help us work together to achieve this.

This supports PHE’s strategy, From evidence into action, which calls for improved health and wellbeing and reduced health inequalities through place-based approaches that:

- develop local solutions drawing on all the assets and resources of an area

- integrate public services

- build resilience of communities

Building social capital with community-centred approaches

There is a growing interest in the UK in community-centred approaches to enhance individual and community capabilities, create healthier places and reduce health inequalities.

Community-centred approaches are not just community-based, but about mobilising assets within communities, promoting equity, and increasing people’s control over their health and lives.

It involves:

- using non-clinical methods

- using participatory approaches, such as community members actively involved in design, delivery and evaluation

- reducing barriers to engagement

- utilising and building on the local community assets

- collaborating with those most at risk of poor health

- changing the conditions that drive poor health

- addressing community-level factors such as social networks, social capital and empowerment

- increasing people’s control over their health

Why invest?

Most local authorities are embracing community-centred ways of working, but the challenge that many are now seeking to achieve is the scaling-up of a whole-system community-centred and asset-based approach.

Evidence cited by NICE on the costs and economic benefits of community-centred approaches is limited, partly because it is difficult to assess and measure wider social impacts and compare areas.

Nonetheless, community-centred approaches offer a different way to use local resources, and some studies have evidenced that there is good social return on investment.

The London School of Economics found that:

- timebanking has a return of £2.89 for every £1 invested

- befriending for older people gives a return of £3.75 for every £1 invested

- community navigators have a return of £3 for every £1 invested

The Cabinet Office and Department for Work and Pensions’ report ‘Wellbeing and civil society’ found that:

- the value that frequent volunteers place on volunteering is around £13,500 per year *‘not being able to meet up with friends a number of times per week’ is equivalent to a cost of £17,300 per year

- the value that people place on ‘living in a society where they feel they can trust people’ is about £15,900 per year

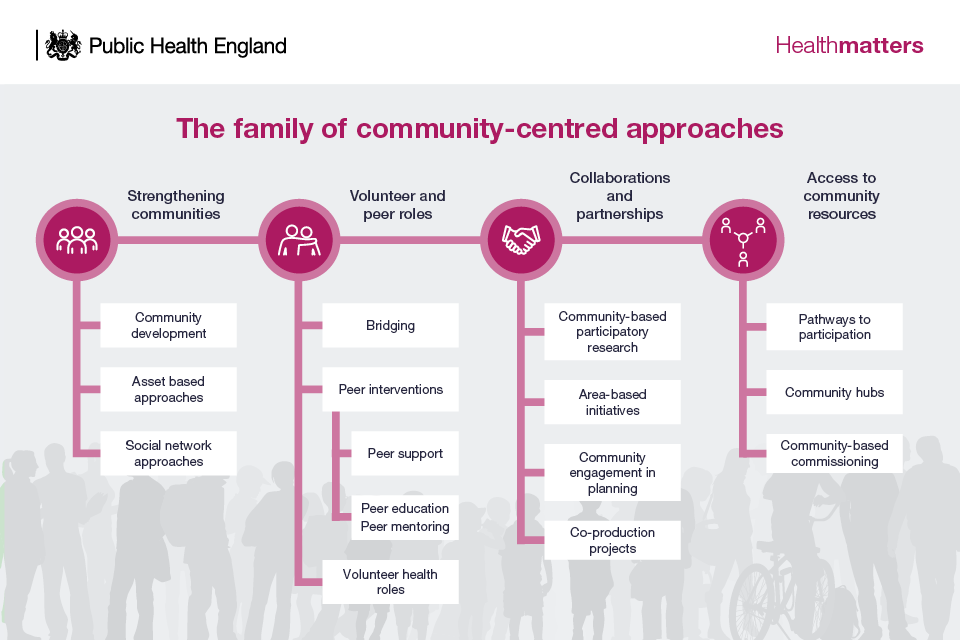

The family of community-centred approaches

The ‘family of community-centred approaches’ has been developed as a framework to represent some of the practical and evidence-based options that can be used to improve community health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities. PHE has published guidance on using the family model.

Infographic - the family of community-centred approaches

Most localities have good examples of community-centred practice. The challenge that many are now seeking to achieve is the scaling-up of a whole-system community-centred approach that is also built ‘bottom-up’ from the diversity of grassroots community organisations and members.

This edition of Health matters highlights some of the successful interventions within the family model that have been implemented across England.

Strengthening communities

These approaches involve building on community capacities to take action together on health and the social determinants of health. It includes community development, asset based approaches, social action and social network approaches, such as time-banking or Men’s Sheds.

Nationally, the Big Local programme is an opportunity for residents in 150 neighbourhoods to come together to make their area an even better place to live. Early findings indicate that approaches that empower communities to have greater control can have positive effects on wellbeing. Control, satisfaction with the area and sense of belonging are main factors.

Volunteer and peer roles

These approaches focus on enhancing individuals’ capabilities to provide advice, information and support or organise activities around health and wellbeing in their or other communities.

The premise is that people will use their life experience, cultural awareness and social connections to relate with other community members, to communicate in a way that people understand and to reach those not in touch with services.

It includes bridging roles such as:

- health trainers

- peer support

- volunteer health roles

PHE is promoting and supporting the development of mutual aid in drug and alcohol recovery. Mutual aid can make a significant contribution to effective treatment as highlighted in the Home Office Drug Strategy.

International peer-reviewed evidence demonstrates that involvement with mutual aid can significantly improve recovery outcomes, and that more active or frequent involvement is associated with greater improvement in outcomes.

PHE has produced a mutual aid toolkit, including an evidence briefing, a self-assessment tool, guidance for commissioners and providers, coordinated via a national reference group.

Collaborations and partnerships

These approaches involve communities and local services working together at any stage of the planning cycle, from identifying needs through to implementation and evaluation.

It includes community-based participatory research, area-based initiatives such as healthy cities, community engagement in planning and co-production – a term used to describe engaging community members and service users as equal partners in service design and delivery.

PHE supports collaboration and coproduction through the health and wellbeing alliance. This is made up of 21 voluntary and community sector umbrella organisations with the aim to increase their voice and expertise in national policy making.

Video: ‘Wandsworth Coproduction in Action’.

Access to community resources

These approaches work by connecting people to community resources, practical help, group activities and volunteering opportunities to meet health needs and increase social participation. It includes approaches that improve pathways to participation such as:

- social prescribing

- community hubs

- community-based commissioning

Infographic - social prescribing

GPs and other health care professionals can refer people to a range of local, non-clinical services.

NHS England is aiming for social prescribing to be operational in all GP practices in England. A national team is working to integrate it into the NHS system and support delivery through implementation and evaluation tools and guidance. It is supported by regional and national networks and the provision of DH funding for local projects.

Many local plans, including Sustainability and Transformation Plans, now include social prescribing schemes.

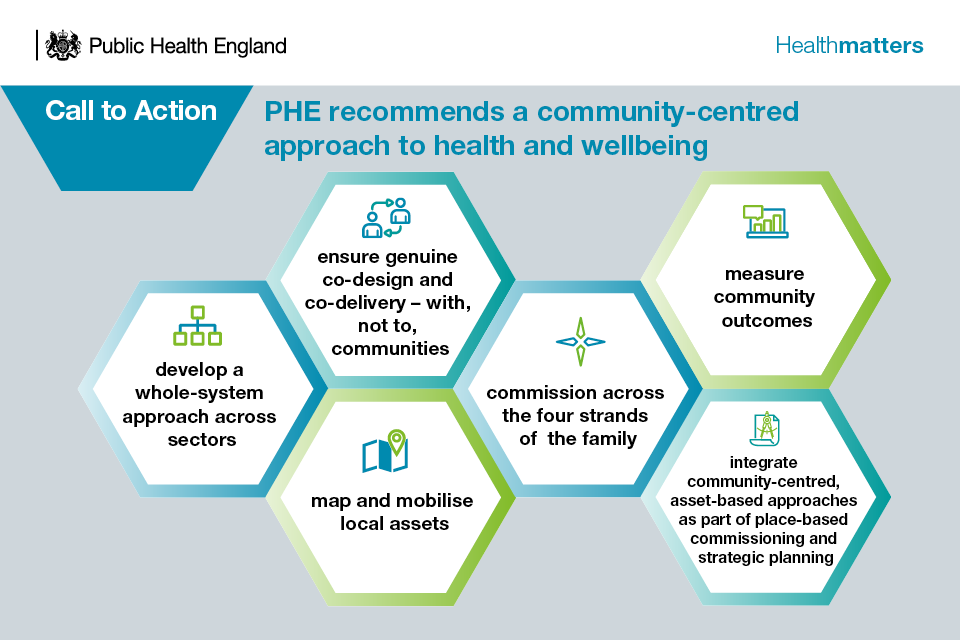

Call to action

Infographic - call to action

Develop a whole-system approach

Empower communities by working across partnerships and sectors to maximise impact and remove system barriers.

Genuine co-design and co-delivery

Involve members of the community in setting priorities, monitoring and evaluating services and initiatives.

Working co-productively leads to improved outcomes for people who use services and carers, and has a positive impact on the workforce. Think Local, Act Personal is a national partnership committed to enabling co-design and co-delivery.

This national partnership has over 50 organisations committed to transforming health and care through personalisation and community-based support, including PHE, central and local government, the NHS, the provider sector, people with care and support needs, carers and family members.

The partnership delivers a work programme through work streams, which is agreed with the partners and funded annually by the Department of Health.

Map and mobilise local assets

Work with members of the community in identifying and developing the skills, knowledge, networks, relationships and facilities available that contribute to health and wellbeing for all community members.

PHE’s Health asset profiles can be used to explore local data on protective factors.

PHE has also tested its SHAPE digital tool to support local asset mapping. Wakefield District, for example, integrated an asset map into their Joint Strategic Needs Assessment to support alcohol reduction. Macmillan also developed an asset map to improve the quality of life of people with cancer.

Commission across the 4 strands of the family of community-centred approaches

These approaches are important for achieving all public health outcomes and PHE has been linking practice across our programmes, for example, health protection, drugs and alcohol, obesity, healthy ageing, children and young people’s health.

Measure health and social outcomes that people say matter

Such as:

- wellness

- social connections

- improved neighbourhood environment

These protective factors can help buffer against risk factors like smoking, obesity, and drug and alcohol use.

These outcomes remain difficult to measure but are best done at a local level. The What Works Centre for Wellbeing has produced a local wellbeing indicators guide and dataset to support localities.

Integrate community-centred, asset-based approaches as part of place-based commissioning and strategic planning

Community action is a necessary component of place-based approaches to reduce health inequalities, alongside and as part of, healthy public policy and prevention services.

Devolution plans present an opportunity to increase the power and control of local communities. This can also be supported through the Localism Act and the Social Value Act. Initiatives such as supporting community business support local economic growth and community wellbeing.