Global Disability Summit: One Year On – accountability report 2019

Published 26 September 2019

Foreword from the co-hosts

The Global Disability Summit was co-hosted by the UK Department for International Development, the International Disability Alliance and the Government of Kenya in July 2018. It was a game-changing event with far reaching consequences.

World leaders, government officials, civil society, the private sector, the donor community and Disabled People’s Organisations came together to share experiences, ideas and aspiration for development and humanitarian work inclusive of people with disabilities. People with disabilities were at the centre of design and delivery of the Summit, reflecting the fundamental principle of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the disability rights movement; ‘nothing about us without us’.

The drive and energy brought by all attendees and supporters of the Summit was unprecedented, resulting in hundreds of commitments being made on disability inclusive development and humanitarian action. Over the year following the Summit, the co-hosts have continued to work together, in partnership with a range of sector representatives, to develop an approach to accountability for the commitments made. An early step in this process is the analysis and reporting work to inform this One Year On report, presenting independent analysis by Equal International. We launched a self-reporting survey, giving everyone who made commitments an opportunity to reflect on the progress they have made. Disabled People’s Organisations in 3 focus countries (Kenya, Nepal and Jordan) provided case studies of their country’s progress on disability inclusion since the Summit, best practices and lessons learnt.

The findings are set out in this report. As co-hosts we will build on this evidence and work with partners to establish a longer-term accountability process. We hope the examples of progress inspire the whole international development community to continue to realise the potential of our collective action.

Let us use this moment to reflect on and celebrate the progress we have collectively made to date, then support each other to go even further, delivering on our shared ambition and vision for a truly inclusive world.

Thank you for your continued commitment and partnership.

Now is the time.

The Global Disability Summit 2018 co-hosts

-

The Department for International Development

-

The International Disability Alliance

-

The Government of Kenya

Executive Summary

The Global Disability Summit 2018 (GDS18) was an ambitious milestone for disability inclusive development. One hundred and seventy one governments and organisations made substantial and wide-ranging commitments. Over 300 governments and organisations signed the GDS18 Charter for Change, encouraging focused implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Penny Mordaunt, the then UK Secretary of State for International Development, called on all of those engaged in development and humanitarian assistance to ‘step-up’ efforts to focus on improving the lives of people with disabilities.

GDS18 started “a new wave in the disability rights movement; a new way to do advocacy in partnership with a wide range of stakeholders.” [footnote 1]. One year on, and this positive impact is beginning to show.

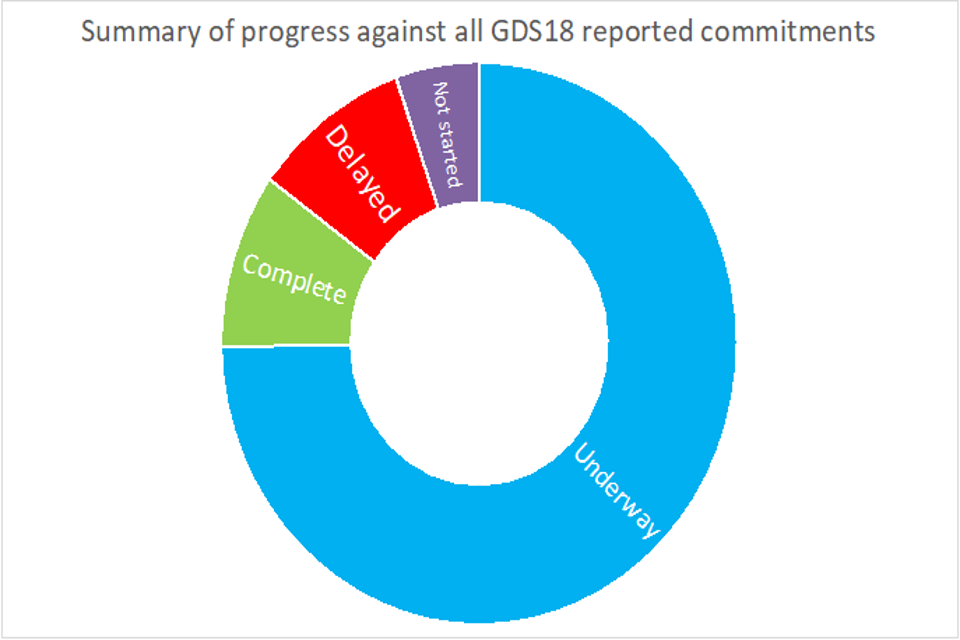

The results of the first GDS18 self-reporting survey demonstrate that significant progress has been made on implementation of the 968 Summit commitments. Work is reported to be underway on 74% of the commitments and 10% are reported as already completed, contributing towards an improved and increased visibility of disability inclusion within development and humanitarian action.

For example, in Nigeria, the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act has now been passed following 17 years of advocacy from Nigerian-based Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs). In Rwanda, ongoing efforts by DPOs have helped push for completion of the National Policy on Disability and Inclusion which was finalised at the end of 2018. The UN launched a new Disability Inclusion Strategy in June 2019 which is ground breaking in its aim to embed sustainable and transformative progress on disability inclusion across the UN system. DFID’s wide range of ambitious commitments are all completed or on track, including publishing a new Disability Inclusion Strategy at the end of 2018 and launching the Inclusive Education Initiative fund in 2019. Both the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade have adopted the new OECD-DAC disability marker, whilst in the private sector Unilever Plc report progress on their ambitious vision to be the number one employer of choice for people with disabilities by 2025.

Beyond the delivery of individual commitments, the wider impact of the Summit is also clearly visible, along with progress on realising the GDS18 Charter for Change. Evidence indicates a growing awareness of the effect disability inclusion can have on development outcomes, helped by rapidly improving data and the ‘Leave no one behind’ commitments of Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Key stakeholders working at the international level observed that the Summit helped to galvanise momentum and action on the issue of disability inclusion globally. For example, Sir Mark Lowcock, Head of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, arranged for the International Disability Alliance to deliver a briefing on disability inclusion to UN Humanitarian Principals for the very first time. This is just one example at the global level which testifies to the shifts in culture and leadership that the Summit introduced.

The DPO advocacy movement is benefitting from GDS18 momentum, with organisations in Kenya and Nepal providing technical support to government around disability inclusive policies, and DPOs in Bangladesh using GDS18 commitments to support their advocacy for strengthening implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). More generally, 68% of respondents to the self-reporting questionnaire felt that GDS18 had made it easier for their organisation to work in a more disability inclusive way.

The impact of the Summit from the perspective of disability activists has been gathered through case studies carried out by Disabled People’s Organisations (DPOs) in Kenya, Nepal and Jordan. These reports give an indication of the breadth of progress at local and national level. The range of reported progress varies from a greater awareness of human rights and disability inclusion among government and non-state actors in Kenya, to a knowledgeable DPO and civil society movement in Nepal, and gradually improving visibility of disability inclusion in Jordan.

This report is an early step toward highlighting and securing the positive changes promised by GDS18 commitments, providing the information needed to help organisations hold themselves and others accountable, and to support efforts to advocate for strengthened implementation of the CRPD. A long-term approach to GDS18 accountability will pick up where this report ends. We hope that governments and organisations already engaged in GDS18 and included in this report, as well as those new to disability inclusion but inspired by this report, will act as champions as the outcomes of GDS18 are taken forward in the months and years to follow.

Now is the time that we must “focus on moving from words to action; working together as partners; and holding ourselves and each other to account for our promises.” [footnote 2].

Introduction

The Global Disability Summit 2018 (GDS18) was a historic event for disability inclusion. Co-hosted by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), the Government of Kenya and the International Disability Alliance (IDA), GDS18 inspired unprecedented engagement and generated commitments to action that will help deliver Agenda 2030’s vision to ‘Leave No One Behind’ as well as existing obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).

The Summit itself had 4 main objectives:

- raise global attention and focus on a neglected area

- bring in new voices and approaches to broaden engagement

- mobilise new global and national commitments on disability

- showcase best practice and evidence from across the world

When held up against these 4 objectives, GDS18 secured notable successes. GDS18 was attended by approximately 1200 delegates from 67 countries including a Head of State (Ecuador), over 40 government Ministers and 5 heads of UN agencies[footnote 3]. People with disabilities were at the centre of planning and delivering the Summit, in line with the principle of ‘nothing about us without us.’ The event brought together high-level decision makers with existing champions of disability inclusion, emerging partners and new donors. By the time of the Summit, over 300 organisations and governments had signed the Charter for Change, a framework for action on implementing the CRPD. Attendees also made close to 1000 specific commitments intended to strengthen disability inclusive development, including many from agencies and governments comparatively new to disability inclusion.

GDS18 was designed to be more than just a one-off event; by making commitments, governments and agencies also made themselves accountable for implementing change. The long-term success of GDS18 will be realised as these commitments are implemented and start to have a positive impact on the inclusion of people with disabilities. Work to track and build upon the commitments made at GDS18 is underway; this report is an early step in that process. This report provides a one year on snapshot of progress made to date on the commitments and includes:

- analysis of the scope, scale and nature of the original commitments made by participating agencies

- results from a self-reported questionnaire designed to track progress on implementation of commitments

- consideration of the wider impact of the Summit to the global disability inclusion movement

- findings from case studies carried out by Disabled Person’s Organisations (DPOs) in 3 focus countries (Kenya, Jordan and Nepal) on their government’s progress against GDS18 commitments

Analysis of commitments

One hundred and seventy one national governments, multilateral agencies, donors, foundations, private sector and civil society organisations made a total of 968 individual commitments around the 4 central themes of the Summit (ensuring dignity and respect for all, inclusive education, routes to economic empowerment, harnessing technology and innovation), as well as 2 cross-cutting themes (women and girls with disabilities, conflict and humanitarian contexts), and data disaggregation[footnote 4].

When the commitments were analysed by stakeholder type, we found the largest number of commitments were made by civil society organisations, representing 48% of all commitments. National governments (including donors) made 31% of all commitments. These figures underscore a relatively high level of engagement from these 2 stakeholder groups. Seventeen multilateral agencies made a total of 125 commitments, also demonstrating a significant level of engagement.

More than half (59%) of the commitments made are intended to have a global reach; these globally focused commitments were mostly made by multilateral agencies and civil society stakeholders (many of which are international NGOs (INGOs)). In terms of country-specific commitments, Nepal is the country which is the subject of the most individual commitments by some considerable margin (50 in total), followed by Rwanda (29) and Ghana (22). With the exception of Rwanda, the majority of these country-level commitments were made by civil society indicating quite an engaged social sector. In Rwanda by contrast just 6 of the 29 commitments were made by civil society with the rest being made by government.

Thematically, the greater number of commitments were made in relation to ensuring dignity and respect for all[footnote 5]. (19%), followed by inclusive education (15%), routes to economic empowerment (14%) and data disaggregation (12%). The fewest number of commitments were made in relation to harnessing technology and innovation (10%), although it is worth noting that these included some particularly significant and ambitious commitments.

Applying a CRPD lens to GDS18 commitments, Article 31 (data) was the CRPD Article most often implicated within the commitments (10% of all commitments aligned with this Article). This was followed by Article 32 (international cooperation) and Article 9 (accessibility) both at 9% as well as Article 27 (employment) and Article 24 (education) both at 8%.

Only 4% of commitments were deemed ‘not trackable’ insofar as work committed was already well underway or delivered by the time of GDS18 (n=23); or the commitment statements themselves were too general or just a descriptive list of activities without clear targets (n=10). Eight commitments were not tracked because they had no obvious link to disability, for example focusing on eliminating child marriage and female genital mutilation; focusing on women’s empowerment; or making general references to vulnerable people. More detailed analysis of the commitments is available in Appendix 1. Selected examples of key initiatives and commitments from GDS18 are available in Box 1 below.

Box 1 Selected key initiatives and commitment pledges made during GDS18

- World Bank Group announced a set of 10 wide-reaching commitments designed to accelerate global action on disability-inclusive development in the areas of education, digital development, data collection, gender, post-disaster reconstruction, transport, private sector investments and social protectio

- The head of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) recommitted to the UN’s proposed review into how the UN system supports the rights of persons with disabilities and confirmed the UN Secretary General’s earlier commitment to developing a new system-wide policy, action plan and accountability framework on disabilities by early 2019

- UNICEF pledged to work with partners to ensure an additional 30 million children with disabilities gain access to education by 2030

- ILO’s Global Business and Disability Network committed to provide a framework for companies at global and national level to learn from each other about inclusive practices on employment

- Launch of the DFID-Leonard Cheshire data portal (https://www.disabilitydataportal.com/). Four donor governments (Australia, Sweden, Canada and Finland) also committed to implement a disability policy marker to track disability inclusion in aid development and to adopt the voluntary OECD-DAC disability marker

- Humanitarian agencies set out more clearly how they are trying to be more responsive to people with disabilities with some strong commitments recognising the specific needs of people with disabilities in this sector

- ten national governments committed to using the Washington Group questions on disability status in upcoming national censuses or surveys (Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia), of which 7 will include the questions in their national population census in the next 5 years.

- Nine national governments announced their commitment to pass or formulate new or revised laws for disability rights (Lesotho, Nigeria, Malawi, Nepal, Uganda, Rwanda, Mozambique, Palestine, Namibia). The Kyrgyz Government committed to ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities by 2021/2022

- seventeen national governments committed to creating and implementing inclusive education sector policy and plans (Nigeria, Malawi, Philippines, Kenya, Nepal, Rwanda, Senegal, Ghana, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Jordan, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Tanzania, Ethiopia, Uganda, Zimbabwe)

- fourteen national governments and multilaterals committed to supporting inclusive social protection systems (Cameroon, Rwanda, Lesotho, Nigeria, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, Uganda, ILO, Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Nepal, International Social Security Association, Qatar Foundation for Social Work)

- five private sector companies (BT, CISCO Systems, Unilever, Microsoft and Purple Zest ltd) made commitments to actively increase the numbers of disabled people in their workforce or to provide training programmes and support to enable disabled people to gain work experience in their field

Self-reported progress

Background

Between April and May 2019, a self-reporting questionnaire was sent out to the 171 stakeholders who had made commitments during GDS18. The web-based survey was designed to capture what progress stakeholders have made on their commitments since July 2018. They were asked to re-state each of their GDS18 commitments by theme, and to rate progress made ranked as either: complete; underway; delayed; not started; or discontinued (see Table 1). They were also encouraged to provide links to documents or reporting mechanisms to support their assessments. In addition to their commitment ranking they were asked the extent to which their organisation has changed to become more disability inclusive since GDS18 and whether or not they felt the Summit and commitments had made it easier for them to work in a more disability inclusive way.

| Table 1 | Ranking criteria for the self-assessment process |

|---|---|

| Complete | The commitment has been completed and evidence is available in the public domain and/ or can be provided by the stakeholder |

| Underway | The commitment is underway and on-track to be delivered by the date set, and evidence is available in the public domain and/ or can be provided by the stakeholder |

| Delayed | The commitment is underway but not on-track to be delivered by the date set, and evidence is available in the public domain and/ or can be provided by the stakeholder |

| Not Started | No work has yet started on the commitment although we have intentions to begin |

| Discontinued | No work will be carried out on this commitment |

In response, 58% (n=99) of stakeholders reported back on their progress which is relatively high for a web-based self-reporting survey.

Multilateral agencies had the highest response rate, although most stakeholder groups showed quite high levels of engagement with this questionnaire:

- multilateral response rate was 94% (n=16)

- foundation response rate 57% (n=4)

- civil society response rate 57% (n=45)

- private sector response rate 50% (n=7)

- government response rate 50% (n=20)[footnote 6].

Results

A basic analysis of the responses shows that most of the commitments made for GDS18 are reported as being underway (74%), and 10% are reported as having been completed. This is encouraging news; it suggests that work is underway for almost three quarters of all GDS18 commitments which is likely to be contributing towards an increased visibility of disability within development and humanitarian action. Only 5% of commitments are reported as not yet started. Where information has been provided, the reasons given generally relate to an ongoing need to mobilise resources, make sufficiently detailed plans, or wait for others to make their inputs before work can get started. There were no commitments classified as discontinued.

Summary of progress against all GDS18 repotted commitments

With the exception of the ‘Other’ category (which is a mix of different focus areas including commitments regarding human resources)[footnote 7]., analysis by category showed that broadly there was consistency across categories, with harnessing technology and data collection commitments more likely to be reported as completed (both at 13%) whilst commitments made under the theme of women and girls had the highest number reported as being delayed (19%). The humanitarian theme was the one in which we found the highest number of commitments recorded as not started (11%).

Responses came back from a cross-section of all stakeholder groups, all of which will be utilised for the purposes of longer-term monitoring. Due to the large number of responses, we have limited the following section of the report to focus on the commitments we anticipate having most impact at scale; particularly those made by governments, multilaterals, the private sector and foundations.

National governments: Progress against commitments

- most notable amongst the commitments which have been completed are those in which governments have enacted positive disability legislation for the first time or have updated existing legislation to ensure it is more CRPD compliant. Early in 2019, for example, the Nigeria Federal Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development assented to the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act representing a significant achievement for the disability movement who lobbied tirelessly for this to happen

- in Rwanda, ongoing efforts by DPOs have helped push for completion of the National Policy on Disability and Inclusion which was finalised towards the end of 2018. The Cabinet have scheduled the policy for adoption in 2019. In close collaboration with DPOs, the government of Rwanda also developed a ‘Roadmap’ for implementation of the GDS18 commitments during 2019 which was welcomed by civil society as a positive indication that the government intends to continue to prioritise the rights of people with disabilities

- the Federal Government of Somalia is reporting that it is making positive progress towards developing a new disability law which aims to eradicate the stigma faced by people with disabilities. The Federal Government has actively sought the inclusion of people with disabilities and their representative organisations in the latest constitutional review process with relevant recommendations for the final Constitution

Multilateral agencies: Progress against commitments

- significant amongst the multilateral stakeholder group has been the progress across the UN system on the development of a United Nations Disability Inclusion Strategy (UNDIS). At the Summit the head of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) recommitted to the UN’s review into how the UN system supports the rights of persons with disabilities and confirmed the UN Secretary General’s earlier commitment to developing a new system-wide policy, action plan and accountability framework on disabilities by early 2019. The new UNDIS was subsequently developed between October 2018 and March 2019 and launched at the 12th UN Conference of States Parties to the CRPD (COSP) in June 2019. The UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities reflected on the contribution of GDS18 to the development of the UNDIS:

The Global Disability Summit had a major impact on the UN’s ambition to become disability inclusive. Without the global attention and the momentum built up by the Summit it is unlikely that the UN Disability Inclusion Strategy would have had such support from UN Principals or been developed with the same energy and commitment.

-

The World Bank reported considerable progress against 7 of its broad ranging commitments including for example piloting an initiative to develop disaster risk reduction project-specific action plans for disability inclusion; finalising production of a guidance note on how to conduct disability disaggregation through surveys conducted or supported by the World Bank; launching a Safe and Inclusive Schools Platform with a strategy for ensuring equity and inclusion in World Bank education projects; and drafting a new Disability Directive alongside creating a new human resource information system to capture confidential information on staff who wish to identify as having a disability

-

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) launched, in November 2018, their Guidelines for Providing Rights-based and Gender-responsive Services to Address Gender-based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for Women and Young People with Disabilities, which is now being rolled out to regional and country offices

-

The Inter-American Development Bank has published a new policy brief on ‘Education for All: Advancing Disability Inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean’ and has already successfully hosted a seminar focusing on digital technology and disability inclusion at the IDB’s Multilateral Investment Fund’s Forum on Microenterprise (FOROMIC) in October 2018

-

UN Women has completed a new strategy designed to ensure a more systematic approach towards strengthening the inclusion of the rights of women and girls with disabilities in UN Women’s efforts to achieve gender equality, empowerment of all women and girls, and the realisation of their rights

-

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has appointed a dedicated focal point to foster the inclusion of persons with disabilities in its mandated activities

Donors: Progress against commitments

- DFID published a new Disability Inclusion Strategy at the end of 2018 and launched the Inclusive Education Initiative fund at the World Bank Spring meetings in 2019. DFID’s flagship Disability Inclusive Development programme is progressing well, alongside the disability inclusion theme of its UK Aid Connect programme, and the ‘Leave No Girl Behind’ funding window to the Girls Education Challenge programme. Since signing the Inclusive Data Charter at the Summit, DFID published an Inclusive Data Charter Action Plan in March 2019

- Over the last year DFID has doubled its funding to its AT2030 programme focused on learning what works in assistive technology, and the ATscale global partnership has the potential to revolutionise access to assistive technology, with new partners such as the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) coming on board

- The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) provided funding for the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to undertake a baseline review of the UN system in preparation for the development of the UN Disability Inclusion Strategy (UNDIS)

- both the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) and DFAT reported adopting the voluntary OECD-DAC disability marker with DFAT also reporting they now routinely use the Washington Group questions when collecting data on disability

Private Sector and Foundations: Progress against commitments

- Ford Foundation reported work is underway on a new Disability Justice Fund initiative in the US which will bring donors and disability activists together to help catalyse change within the philanthropic sector

- Unilever Plc reported progress on its commitments under the Routes to Economic Empowerment theme by starting work to realise its vision of becoming the number one employer of choice for disabled people by 2025. They made a high-profile commitment to support disability inclusion in business with a worldwide call to action for business to recognise the value and worth of disabled people at Davos 2019

- Mannion Daniels Ltd indicated work has begun on providing guidance on use of the Washington Group Short Set of Questions to applicants and grant holders. They reported that, by March 2019, 66 grantees include disability as a key word in their reporting

- Open Society Foundations reported progress on the inclusion of a disability lens to its programming on women and girls. Their Women’s Rights portfolio has adopted an intersectional approach. A proportion of grantees within this funding window are organisations of women with disabilities but at the same time, all grantees are being encouraged to include women with disabilities in their activities

- The international foundation Royal Dutch Kentalis reported that it has completed professional training of Deaf adults so they can run workshops for (hearing) parents on the importance of early childhood development and education in Uganda, Zambia, Rwanda with a planned roll-out of the program to rural areas

Wider impact of the Summit

Beyond individual organisations’ progress against their commitments, there is evidence that GDS18 has had a wider impact in raising awareness, and increasing prioritisation, in relation to disability inclusion. The Summit highlighted disability inclusion as key to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and leaving no one behind, inspiring a broader movement for change and igniting action on a global scale.

The Charter for Change[footnote 8]

The Charter for Change is a key part of the legacy of the Summit. The document was a collective call to action on disability inclusion, aiming to bring about further implementation of the UN CRPD and highlight the importance of delivering the Sustainable Development Goals. Over 300 governments and organisations signed the Charter by the time of the Summit. To date, there are 350 signatories.

The Charter has been influential in inspiring the global community to prioritise a number of key issues. For example, NORAD is a founding partner of the Inclusive Education Initiative. On its launch at GDS18, former Minister for Development Cooperation, Nicolai Astrup, noted that Norway had committed itself to promote the human rights of persons with disabilities both through the implementation of the CRPD and its work towards the Sustainable Development Goals, and was now moving from words to actions. The new Inclusive Education Initiative would contribute to ensure that children and young persons with disabilities have better access to education all over the world. The Minister later added that Norway signed the Charter for Change to send a strong signal that it stands firm on its commitment to strengthen the implementation of the UN CRPD. It is an expression of political will to lift this area of work together with all who made commitments at GDS18.

In relation to the Charter, Vladimir Cuk, IDA Executive Director, also stated:

The Charter for Change has played a hugely important role in bringing focus to the UN CRPD and inspiring action in developing countries to further implement it. The number of governments and organisations which signed the Charter demonstrates the increasing global attention and commitment being brought to the CRPD, which has the potential to bring about positive change to the lives of people with disabilities.

This report does not analyse in detail the impact of the Charter on the growing global disability movement, but this could be an interesting focus for future accountability reports.

Organisational level impact

In terms of organisational level impact, the self-reporting questionnaire asked agencies to reflect on whether GDS18 made any difference to the way they work. Just over 68% of all respondents reported that GDS18 had made it easier for their organisation to work in a more disability inclusive way.

Quotes from a couple of respondents sum up some of the sentiments being expressed:

Before the Government of Ghana participated in the Global Disability Summit very little attention had been paid to supporting persons with disabilities and little resources allocated to addressing their needs. Following the Summit, there has been a positive shift in the focus of the Government of Ghana on persons with disabilities

Overall, the Summit has been well received, is a living element in the global community around disability and development, and has certainly helped to galvanise momentum, prioritisation and action on the issue.

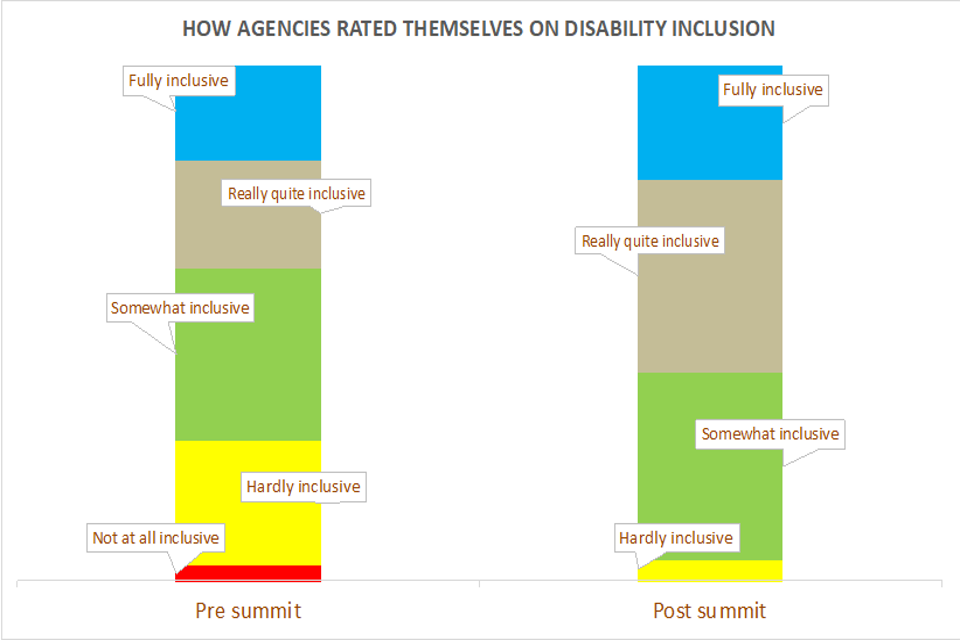

It is also possible to see that as a result of GDS18 there was a 54% increase in the number of agencies reporting they believe their organisation to be more inclusive since the Summit, in comparison to before the Summit:

How agencies rate themselves on disability inclusion

Impact of GDS18 commitments in CRPD advocacy work[footnote 9].

Part of the ground-breaking potential of GDS18 commitments is their ability to inspire innovation and incentivise governments to do more around fulfilling their obligations under the CRPD. For example, a small number of national coalitions in a selection of Commonwealth countries have been supported through the Disability Rights Fund and Disability Rights Advocacy Fund (funded via DFID) to utilise the GDS18 commitments in CRPD related advocacy.

In Rwanda, the National Union of Disabilities Organisations in Rwanda (NUDOR) had the opportunity to provide input into their government’s original commitments and have since been involved in helping the government put together its Roadmap for implementation of the commitments. NUDOR representatives have made extensive use of their experience by participating in the review of Rwanda by the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Geneva, and working on the alternative report, to ensure that the government’s new Roadmap aligns well with the CRPD.

In Bangladesh, a delegation of DPOs was supported to attend the UN’s 11th pre-sessional working group on the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities during which Bangladesh’s first State Report on its implementation of the CRPD was considered. A key part of the preparation for attending this meeting was to review the alternative report to pull out examples where leveraging GDS18 commitments could help strengthen arguments around CRPD compliance. A key moment in the process came when DPO advocates realised that the GDS18 commitments could be used to fuel their own advocacy for CRPD implementation.

Country level case studies

In this section, we provide space for people with disabilities to give us their reflections on what progress has been made by their governments post-Summit. We engaged 3 disability activists within the disability movements of Kenya, Jordan and Nepal to deliver a situational report on how well their governments are doing towards meeting their GDS18 commitments. In Kenya the review was led by the Users and Survivors of Psychiatry in Kenya (USP-K); in Nepal this was led by the National Federation of the Disabled Nepal (NFDN); and in Jordan by the I Am a Human Society for Rights of Persons with Disability (I Am a Human).

In each country, the DPOs were tasked with gathering information directly from government on their progress towards each of the GDS18 commitments and from a selection of persons with disabilities. In each case this involved reviewing the latest government policies, strategies and statements of relevance to the GDS18 commitments; directly engaging government representatives in interviews; and hosting focus group meetings involving people with disabilities representing different interest groups (such as those with different impairments, women and young people). The full case studies can be found in Appendix 2.

Kenya case study: summary

It is evident that the impact of GDS18 has been substantial in Kenya. As a co-host of GDS18, the Government of Kenya were very engaged pre-Summit and a lot of momentum was generated around GDS18 which has continued to influence positive developments around disability inclusion in Kenya.

USP-K noted a greater awareness of human rights and disability inclusion among government and non-state actors following GDS18, especially at national-level. Key progress was also noted by USP-K around several specific areas:

- Launch of the National Action Plan on the implementation of the Global Disability Summit Commitments 2018

- Development by the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection of an advocacy toolkit that will be used to strengthen dignity and respect for all

- Establishment and launch of the Inter Agency Coordinating Committee to coordinate and monitor the implementation of the National Action Plan on the implementation of the Global Disability Summit Commitments 2018

- Plans underway by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics to use the Washington Group Short Set questions in the upcoming National Population and Housing Census in August 2019

- New momentum in legislating; the Persons with Disability Draft Bill 2018 was presented for the second reading at the Senate in April 2019 and the Mental Health Act of 1989 is under review to align it with international best practises and the CRPD

Nepal case study: summary

While the Government of Nepal was represented by the Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizens (MoWCSC) at GDS18, NFDN found that the original representative from the MoWCSC had left and that awareness of the commitments made was very low among other MoWCSC representatives or other government departments. Nonetheless, NFDN revealed positive attitudes to disability exist among government as well as awareness of challenges and barriers related to persons with disabilities. Half of the DPOs and organisations working on disability rights engaged by NFDN were also knowledgeable about GDS18 and the commitments made by the government, enabling civil society to continue to call for action.

Key progress was also noted by NFDN around several specific areas:

- Regulations for the implementation of anti-discrimination legislation were due to be passed in 2018. Whilst this has not happened yet, a draft set of regulations has gone to the Council of Ministers for approval

- The Compulsory and Free Education Act was passed in 2018. The Act aims to provide basic and higher education to children and young people with disabilities and prohibits the rejection of admissions of children with disabilities, it mandates government to take necessary measures to bring children with disabilities into mainstream education

- A new Social Protection Act (2018) includes provision of social protection for people with disabilities

- A Cooperative Act (2018) provides tax exemptions, discounts and seed money to people with disabilities (amongst others) to help promote self-employment and cooperative businesses

- The Central Bureau of Statistics reports working with NFDN to apply the Washington Group Short Set questions in the next national census

- The Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act 2018 has recognised persons with disabilities as a vulnerable population at increased risk during disasters and has made provision to protect them with priority and special programmes

Jordan case study: summary

Progress in Jordan against GDS18 commitments assessed by the Jordanian DPO ‘I Am a Human’ was found to be limited. Findings suggest that little progress has been made against the government’s commitments and awareness around GDS18 generally (both among government and civil society) is limited. This is aligned with the views of people with disabilities across the country. People with disabilities expressed frustration at the slow pace of implementation of well-intentioned policies and strategies of Government of Jordan. From their perspective, more needs to be done before GDS18 has a substantial impact on improving the situation for people with disabilities. Nonetheless, progress since GDS18 has helped to enhance visibility of disability inclusion. Some key areas of progress identified are as follows:

- Disaster preparedness operations have benefitted from awareness raising initiatives focused on the need to plan for the inclusion of sign language users. This included a couple of public information broadcasts that had sign language interpretation. There are plans to instigate video calling facilities for emergency services

- The Public Security Directorate has run training courses on public safety and first aid for persons with disabilities and its institutions in the North Region

- The 2018-2022 Education Strategic Plan includes provision for the rehabilitation of around 400 schools so that children with disabilities can access them whilst also increasing the number of new schools that are accessible. There are plans to increase the overall enrolment of disabled students (although there remains no clear budget allocations or resourcing plans)

- An employment reform policy for persons with disabilities was submitted to the Cabinet for approval. Budget allocations for 2019 included resources to enable implementation of the proposed reforms

- Training courses were implemented by DPOs and the Ministry of Political and Parliamentary Affairs regarding the political participation of persons with disabilities, the political empowerment of women with disabilities, and the media and disability issues

Concluding remarks

GDS18 was an ambitious and dynamic milestone for disability inclusive development whose impact is already being positively felt across the disability sector, one year on from the event. As this progress report highlights, 10% of the 968 commitments made at GDS18 have already been completed. The commitments already delivered include some notable successes at both global and national levels.

Delivery against a further three quarters of GDS18 commitments is currently underway, with most of them reportedly on-track. The potential impact of these commitments on the lives of persons with disabilities once they are realised is both exciting and transformative. The capacity of development and humanitarian agencies to support persons with disabilities is expected to change substantially with the realisation of commitments to adopt the OECD-DAC disability marker, routine use of the Washington Group questions for data disaggregation and the roll-out of disability inclusion standards for future programming. Millions of persons with disabilities will gain better access to education, social protection, work and affordable assistive devices as commitments highlighted by this report are delivered. However, this report underscores that delivery of the GDS18 commitments is not guaranteed. Securing tangible results will require sustained effort from organisations to deliver their commitments and from stakeholders to hold organisations accountable.

A long-term approach to GDS18 accountability is currently being developed, with the aim that it will be launched in 2020. This approach will continue to track the delivery of GDS18 commitments but will also harness and further galvanise the momentum generated by the Summit. The GDS18 co-hosts have been working closely with a Key Stakeholder Group comprised of representatives from across different stakeholder sectors, to design and develop the longer-term accountability process. This is taking place in consultation with a wider Partnership Forum, which is open to all[footnote 10]. The accountability process will take a partnership approach, encouraging delivery of commitments and convening partners to support progress with a focus on national level accountability. The movement will likely be structured around a full-time secretariat supported by an advisory group, working groups and CRPD committee advisors. The secretariat will manage commitments trackers and help facilitate national level dialogues. The approach will link in with existing mechanisms as far as possible, emphasising the synergies with the CRPD and the 2030 Agenda.

This report is an early step toward securing the positive changes promised by GDS18 commitments, providing the information needed to help organisations hold others accountable and to support effort to advocate for strengthened CRPD implementation. The long-term approach to GDS18 accountability will pick up where this report ends. We hope that governments and organisations already engaged in GDS18 and included in this report, as well as those new to disability but inspired by this report, will act as champions as the outcomes of GDS18 are taken forward in the months and years to follow.

Appendix 1: Analysis of Summit commitments

Before looking at the current rate of progress against GDS18 commitments, the Equal International team first analysed the commitments themselves. A key objective of GDS18 was to deliver ambitious new global and national level commitments on disability inclusion, so we looked at the scale and scope of the statements made by each stakeholder group under the main themes.

Analysis by stakeholder

National governments, multilaterals, donors, civil society organisations, foundations and the private sector made a total of 968 individual commitments (see Table 2) around the4 central themes of the Summit (ensuring dignity and respect for all, inclusive education, routes to economic empowerment, harnessing technology and innovation), as well as the 2 cross-cutting themes (women and girls with disabilities, conflict and humanitarian contexts), and data disaggregation[footnote 11].

Table 2: Summary of commitments made by stakeholder type

| Stakeholder type | Number and type of commitments made | Total | Dignity | IE | EE | Tech | Women | Humanitarian | Data | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil Society | 466 | 93 | 59 | 64 | 49 | 59 | 50 | 59 | 33 | |

| Foundations | 24 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| Government | 300 | 59 | 47 | 47 | 30 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 33 | |

| Multilaterals | 125 | 23 | 21 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 17 | 24 | 10 | |

| Private Sector | 40 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 6 | |

| Research | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 11 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 968 | 188 | 142 | 140 | 92 | 106 | 97 | 117 | 86 |

Note: ‘Government’ stakeholder category includes both national government commitments and those made by donor governments

Our analysis shows that the largest number of commitments were made by civil society organisations, representing 48% of all commitments. National governments and donors made 31% of the commitments. These figures show a relatively high level of engagement from the 2 stakeholder groups. There is considerable scope for more engagement with the private sector in the future, 4% of commitments came from this stakeholder group (representing 13 individual organisations). While there were only 17 individual multilateral agencies making commitments, between them they made 125 commitments (13%) which means they are the stakeholder group that made the highest number of individual commitments per agency.

Key facts on the original commitments

- 31% of all commitments were made by government stakeholders

- 48% were made by civil society

- seventeen multilateral agencies between them made 125 commitments

- about 4% are not trackable (work already well underway or delivered; general statement or description of activities without any obvious intentions; no obvious disability focus)

- greatest number of commitments were made in relation to dignity and respect for all (19%), followed by inclusive education (15%), economic empowerment (14%) and data (12%). Lowest number found harnessing technology (10%)

Looking at the themes, the largest number of commitments were made under the category of dignity and respect for all (19%), followed by inclusive education (15%), economic empowerment (14%) and data (12%). The lowest number were found under harnessing technology (10%).

Multilateral agencies focused most of their commitments around data disaggregation, dignity and respect for all, inclusive education, humanitarian, and economic empowerment. Aside from the theme of dignity and respect, governments and donors focused more on inclusive education, economic empowerment and harnessing technology. Civil society focused on economic empowerment, inclusive education, data and women. The private sector focused on economic empowerment, followed by inclusive education.

Analysis by geographical location

The single most popular geographical focus for commitments was global, 572 commitments were intended to have a global reach (59%). Perhaps not surprisingly, the globally focused commitments were made mostly by multilateral and civil society stakeholders (many of which are INGOs). These types of commitments represent a challenge to accountability mechanisms since tracking progress at the global level can be difficult to achieve.

Of those that had a more specific geographical focus, some 190 commitments were made that focused on countries within Africa (20% of all commitments had at least one African country as a focus). This contrasts with Asia where 107 focused on specific Asian countries (11% of commitments had at least one Asian country as a focus), and the Middle East where there were 48 country focused commitments (5% of all commitments). Overall therefore most country focused commitments relate to Africa.

An analysis of stakeholders shows that multilaterals targeted most of their commitments at the global level (89% of commitments). Government commitments understandably were well distributed across regions and countries although it is worth noting that despite having several civil society commitments, there were no government commitments made by Qatar or Pakistan. Civil society stakeholders also covered many regions and countries but there were some notable exceptions. Those countries with government commitments but no civil society commitments include: Cameroon, DRC, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe in Africa; Afghanistan, Burma, and Philippines, in Asia; and Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine in the Middle East. In total, there were 33 countries to which individual country commitments were directed. Overall Nepal is the country which has the most individual commitments by some margin (see Table 3):

Table 3: Countries with highest numbers of commitments

| Country | Number of individual commitments |

|---|---|

| Nepal | 50 |

| Rwanda | 29 |

| Ghana | 22 |

| India | 22 |

| Kenya | 20 |

| Malawi | 15 |

| Jordan | 15 |

| Tanzania | 14 |

| Bangladesh | 13 |

| Uganda | 12 |

| Iraq | 8 |

The African countries which have both civil society and government commitments include:

- Rwanda with 29 commitments; 23 are by government and 6 are from civil society

- Ghana with 22 commitments; 8 are by government and 14 are from civil society

- Kenya with 20 commitments; 4 are by government and 16 are from civil society (although these are all from a single civil society group)

- Malawi with 15 commitments; 11 are by government and4 are from civil society

- Tanzania with 14 commitments; 13 are by government and one from an INGO

This shows that except for Ghana and Kenya, there is not a very significant civil society presence in relation to the submission of commitments coming from specific African countries.

From the Middle Eastern countries:

- Iraq has 8 commitments; 7 are by government and one from an INGO

- Syria has 7 commitments; one is by government (donor) with 6 from civil society (representing a single agency)

Again, this seems to suggest low rates of submission from civil society stakeholders.

From Asia:

- Nepal with 50 commitments; 7 are by government and 43 are from civil society. Nepal represents the country with the most diverse engagement from civil society with 6 different organisations contributing

- India with 22 commitments; 6 are by government and 16 are from civil society (represented by 3 CSOs)

- Bangladesh with 13 commitments; 8 are by government and 5 are from civil society (represented by 1 organisation)

The commitments from Asia show a higher submission rate from civil society with a greater number of commitments being made by civil society in comparison to Africa and the Middle East. However, what this analysis is unable to show is the extent to which civil society may have collaborated with government on the formulation of commitments.

There are no African or Middle Eastern countries where we see a convergence between commitments made by government, civil society and the private sector. In fact, only India has this convergence although the private sector in this instance is represented by just 1 stakeholder. Private sector commitments are mostly directed at the global level (83%).

Analysis by CRPD alignment

Although GDS18 did not actively request organisations to make commitments that align with the CRPD, there is value in understanding the extent to which these commitments are likely to contribute towards fulfilling CRPD obligations. When we analysed the commitments in relation to the CRPD we found that Article 31 (data) was the Article most often associated with the commitments (10% of all commitments aligned with this Article). This was followed by Article 32 (international cooperation) and Article 9 (accessibility) both at 9% as well as Article 27 (employment) and Article 24 (education) both at 8%. More detailed analysis of CRPD alignment can be found in the thematic analysis (see below).

It is worth noting that CRPD Articles 10, 18 and 22 received no coverage at all from GDS18 commitments and Articles 1, 2, 14, 17 and 20 were identified once[footnote 12]. That means key protections around the right to life; liberty of movement and nationality; respect for privacy; liberty and security (especially relevant in mental health work); protecting the integrity of the person; and personal mobility are not a part to any significant degree of GDS18 commitments. Other key CRPD Articles received more coverage but perhaps at levels which are not as high as we might have anticipated:

- Article 5 on equality and non-discrimination (16 alignments)

- Article 6 on women with disabilities (41 alignments)

- Article 7 on children with disabilities (5 alignments)

- Article 8 awareness raising (82 alignments)

- Article 28 standard of living and social protection (28 alignments)

This shows that specific alignment of the of GDS18 commitments with Articles focused on women and on children as well as those on social protection and equality and non-discrimination were not as high as might have been anticipated. This was a surprising finding given the themes promoted at GDS18 and in the pre-Summit documentation. Further work to raise awareness of the link between GDS18 commitments and the CRPD would be highly valuable. This is a key area in which any future GDS18 accountability mechanism needs to be aware of, partly to avoid multiple progress reporting processes but mostly because the GDS18 commitments do offer the opportunity for all stakeholder groups to use their progress in this area as work towards fulfilling CRPD obligations.

Analysis by thematic area

Here we provide an overview of the main findings which arose when assessing the scale and scope of the commitments by thematic area:

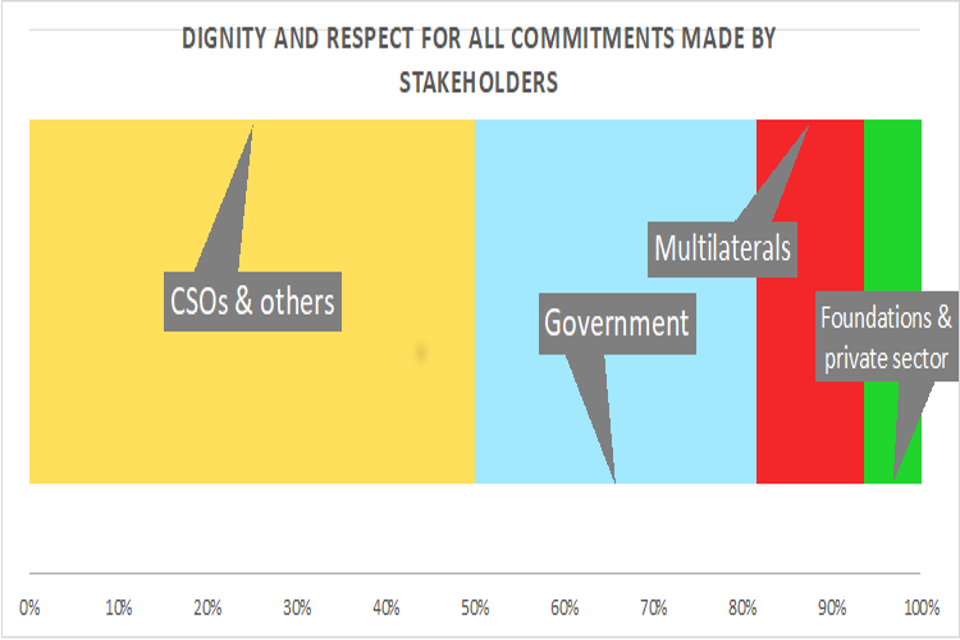

Dignity and respect for all

There were 188 commitments made under this theme representing 19.4% of all commitments. All stakeholder groups are represented in this theme.

Dignity and respect for all commitments made by stakeholders

Fifty nine commitments were made by governments (of which 7 came from donors, including DFID) compared with 94 made by civil society organisations. There were 23 made by multilateral organisations and 12 made by the private sector and foundations combined. Analysis of all the commitments made within this sector suggests that addressing dignity and respect for all tended to be implied through work on policy and legislation without necessarily being the explicit target of the commitment. Perhaps in keeping with the theme, many of the commitments anticipate long timescales, with some reaching as far as 2030. There were some notably strong commitment statements made around tackling discrimination in the public sphere and a good number state intent to empower persons with disabilities and their representative organisations.

Selected commitments made regarding dignity and respect for all:

- Nine national governments announced their commitment to pass or formulate new or revised laws for disability rights (Lesotho, Nigeria, Malawi, Nepal, Uganda, Rwanda, Mozambique, Palestine, Namibia)

- Eighteen national governments, donors and multilaterals have committed to new systematic policies, action plans or strategies for disability inclusion (Malawi, Philippines, Nepal, Uganda, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Myanmar, New Zealand, Canada, Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), World Health Organisation (WHO), UN Population Fund (UNFPA), UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), International Organisation for Migration (IOM), Asia Development Bank (ADB), International Rescue Committee (IRC))

- Seven national governments (Nigeria, Malawi, Kenya, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Jordan) and 4 multilaterals (UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA, IRC) committed to raising public awareness and/or developing new strategies or programmes to challenge harmful stereotypes, attitudes and behaviours against persons with disabilities

- Eighteen civil society organisations will work towards eliminating the institutionalisation of children globally

- The Kyrgyz Government committed to ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities by 2021/2022

- The Government of Rwanda and the Government of Kenya committed to ratify the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Africa

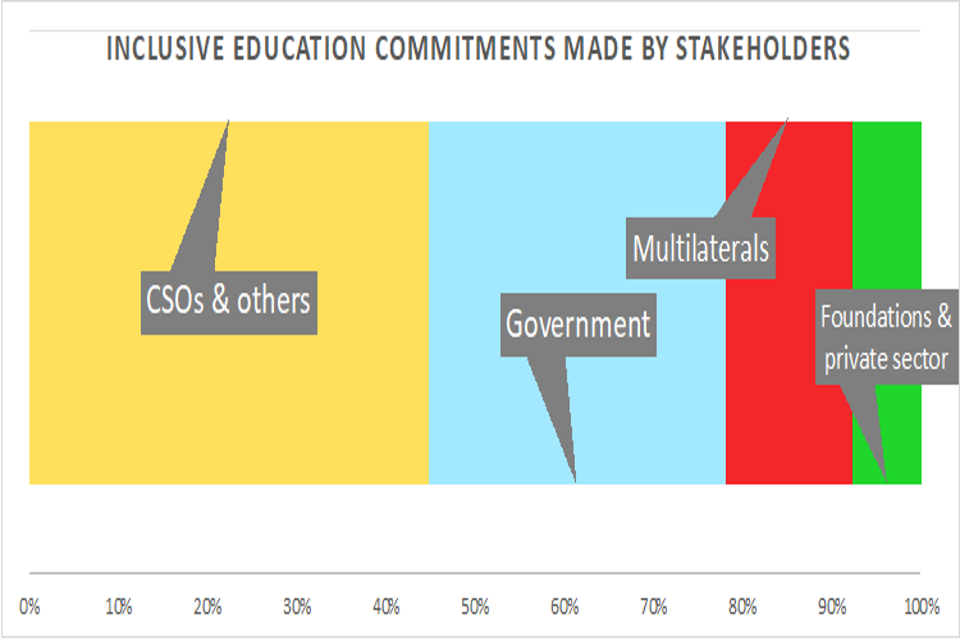

Inclusive Education

There were 141 commitments made under this theme representing 15% of all commitments. All stakeholders are represented in this theme.

Inclusive education commitments made by stakeholders

Forty seven commitments are made by governments (of which 6 came from the donor sector, including DFID) compared with 59 made by civil society organisations. There were 20 commitments made by multilaterals (including 5 made by GPE and 4 by UNESCO alone) and 11 made by the private sector and foundations combined.

On the whole commitments made by governments under this theme are quite generalised towards improving the provision of education for children with disabilities. Almost every commitment that references policies or implementation plans does so in the context of inclusive education. Very few mention special needs education or support to specialist provision (the exceptions are Rwanda and Ghana which mention the need to support both inclusive and specialist education). The level at which the commitments are targeted (e.g. pre-school to tertiary level) is not specific in almost all commitments, except for Zambia (commits to inclusive education at all levels). There is no mention of pre-school provision or life-long learning.

Overall many of the commitments mention the need for supporting improved teacher training and preparedness to include children with disabilities in their classes (both pre and in-service support are mentioned); improving the physical infrastructure of schools to make them more accessible; and embedding the provision of education for children with disabilities within national education plans. Some mention the need to improve the flexibility of curriculums (Rwanda, Lebanon, and Jordan), whilst Rwanda specifically cites the need to provide training to Education Officers to monitor the quality of special needs provision in schools. Some commitments look specifically at the need to link plans to budgets (including Ghana, Nepal, Rwanda and Jordan) with Ghana committing to increase budgetary allocations for Inclusive Education by 1.5% in 2019. Canada commits specifically to supporting programmes that ensure increased educational access to girls with disabilities living in crisis and conflict situations.

As with some of the other sector areas there is a tendency to focus on activities that are specific to children with disabilities rather than tackling barriers. Perhaps not surprisingly, many commitments are specific to types of disability or are context-specific (especially from civil society organisations).

Selected commitments made regarding inclusive education:

- seventeen national governments committed to creating and implementing inclusive education sector policy and plans (Nigeria, Malawi, Philippines, Kenya, Nepal, Rwanda, Senegal, Ghana, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Jordan, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Tanzania, Ethiopia, Uganda, Zimbabwe)

- twelve national governments committed to expanding teacher capacity building and training on Inclusive Education (Malawi, Philippines, Kenya, Nepal, Rwanda, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Myanmar, Jordan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Zimbabwe)

- Five donors and multilaterals committed to endorsing or supporting the Inclusive Education Initiative (UK, Norway, World Bank Group, UNICEF, Global Partnership for Education (GPE)). NGOs and research institutions were also supportive of the Initiative

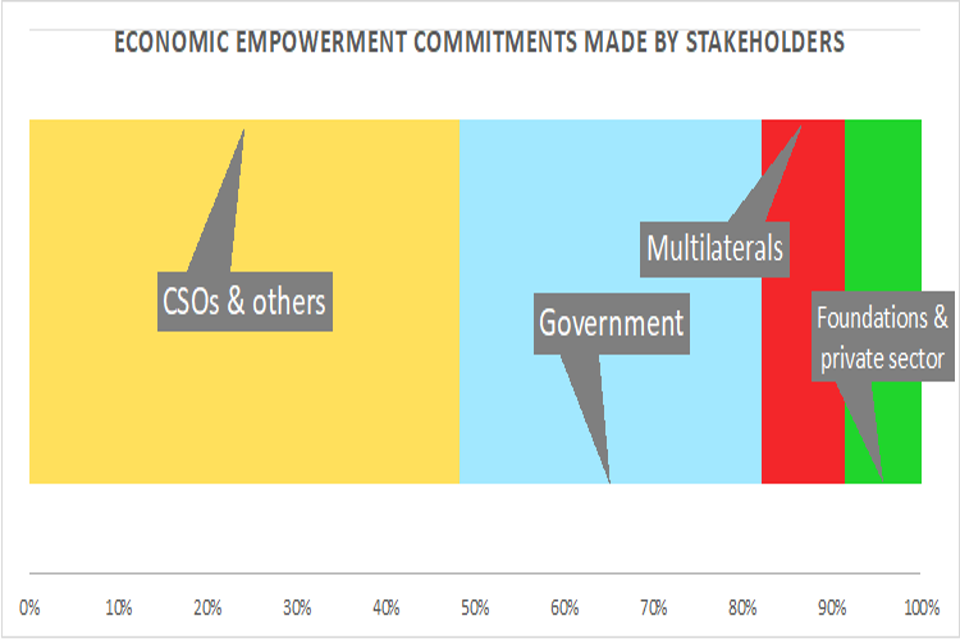

Routes to Economic Empowerment

In total 139 commitments were made under this theme representing 14.5% of all commitments. All stakeholder groups are represented in this theme.

Economic empowerment commitments made by stakeholders

Forty seven commitments are made by governments (of which 3 came from donors, including DFID) compared with 67 made by the NGO sector. There were 13 commitments made by multilateral organisations and 12 made by the private sector and foundations combined.

Across all of the commitments, including civil society ones, organisations looking at work-based issues have focused much more significantly on individual skills-based training and support for persons with disabilities as opposed to tackling structural issues and barriers preventing employment and decent jobs or promoting work experience in the open labour market for persons with disabilities.

Several governments focus their commitments more on “supply side” issues (skills training and access to finance) without equivalent commitments on “demand side” issues persons with disabilities face (including gaining work, selling goods and services in self-employment).

Many commitments that can be identified as relating to the structural issues of inclusive employment practice however are quite non-specific, broad and vague, potentially indicating reservations around what exactly is needed, or that they are awaiting evidence before committing more specifically. There are a significant number of commitments made around social protection commitments.

Some commitments have very long timescales, even though they are concrete - e.g. Philippines committed to implementing existing laws by 2030. It is also interesting to note that some commitments do not reference persons with disabilities but rather use the term ‘vulnerable people’.

The National Council for Persons with Disabilities Kenya has a range of specific commitments, focused on people with disabilities and their environments – they show a clearer sense of direction, purpose and understanding compared to others. Some governments are looking at barriers to access and more than just disability-specific measures (e.g. Kenya, Malawi). Malawi had some barriers-orientated specific commitments.

Selected commitments made regarding routes to economic empowerment:

- fourteen national governments and multilaterals committed to supporting inclusive social protection systems (Cameroon, Rwanda, Lesotho, Nigeria, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, Uganda, ILO, Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Nepal, International Social Security Association, Qatar Foundation for Social Work)

- thirteen national governments, multilaterals, donors and businesses committed to enabling inclusive environments in the workplace (Microsoft, BT, CDC Group, Myanmar, Kenya, Rwanda, DRC, Japan, PIDG, ILO, UNESCO, World Bank, Vidya Sagar)

- eleven national governments, multilaterals, donors and businesses committed to investing in skills development for decent work (Cisco, Essilor, Republic of Korea, Sierra Leone, Philippines, Lesotho, UNESCO, ADB, IRC, UNHCR, Rwanda)

- eight national governments, multilaterals, donors and businesses committed to improving access to decent work (Unilever, Andorra, ILO, Rwanda, Japan, Palestine, Namibia, Purple Zest Ltd)

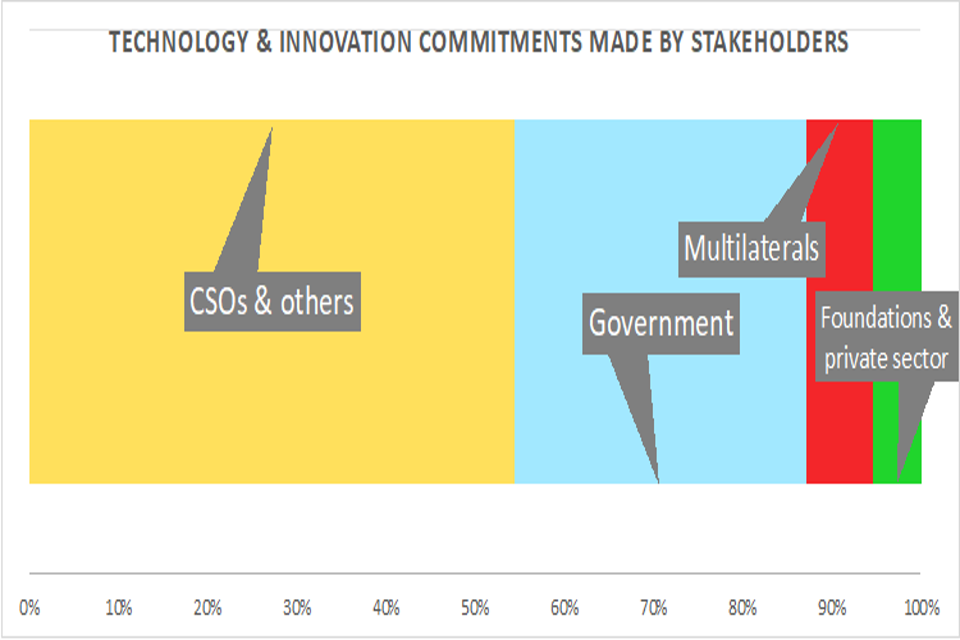

Harnessing technology and innovation

There were 92 commitments made under this theme representing 9.5% of all commitments. All categories of stakeholders made commitments regarding this theme; more than a quarter of all technology and innovation-themed commitments were made by national governments.

Technology and innovation commitments made by stakeholders

Technology and innovation-themed commitments made at GDS18 appear to provide a compelling response to improving the availability and affordability of assistive technologies. The focus of so many commitments on ATscale 2030 and on researching and developing assistive technologies reflects a strong desire to adopt a market-shaping approach to establish a sustainable supply of low-cost, high-quality assistive technology and to harness cross-sector partnership to catalyse change and amplify existing work. The technology and innovation-themed commitments made at GDS18 also indicate some limited focus on embedding assistive technology needs in healthcare systems, including adapting WHO guidelines (Government of Kenya) and providing training to service providers (DRC Ministry of Social Affairs). These were 3 key areas of concern identified by a background note produced for the Summit on assistive technology [footnote 13].

Gaps in the focus of the technology and innovation themed commitments do exist, however. The same background note suggested that:

- data and evidence of assistive technology usage, breakage and repair as well as the success of training programmes for personnel

- increasing the agency and participation of people with disabilities in assistive technology were also priority areas for consideration.

These 2 areas appeared to receive little focus in the commitments made. It is important that these ‘gaps’ do not detract from the commitments that were made. However, looking ahead it is clear that commitments regarding technology and innovation can be strengthened.

Selected commitments made regarding harnessing technology and innovations:

- nine organisations committed to joining the Global Partnership on Assistive Technology (DFID, USAID, WHO, UN Special Envoy Office (UNSEO), UNICEF, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Global Disability Innovation Hub, Government of Kenya, Chinese Disabled People’s Federation)

- The Federal Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development, Nigeria, will establish an affordable technology and innovation centre

- The World Bank Group will screen all digital development projects to ensure they are disability sensitive including through the use of universal design and accessibility standards

- by 2019, the International Committee of the Red Cross will deliver a broader range of high-quality PRP-developed assistive devices and post a 25% reduction in the average cost

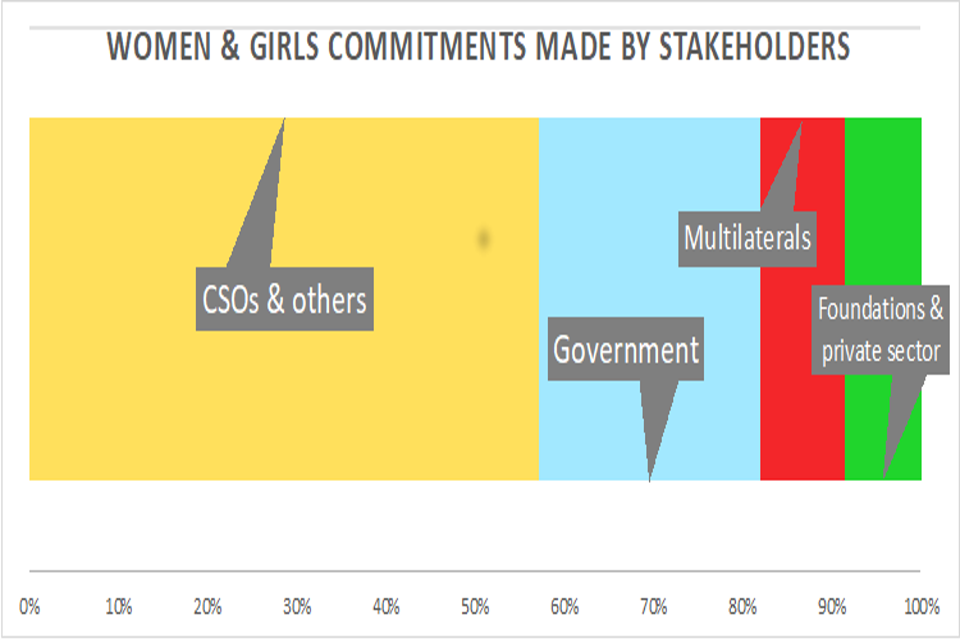

Women and girls with disabilities

There were 105 commitments made under this theme representing 11% of all commitments. All categories of stakeholders made commitments regarding this theme.

Women and girls commitments made by stakeholders

The commitments include a clear focus on gender-based violence and sexual reproductive health which aligns with priority areas identified in a recent Global Advocate Survey (by Equal Measures 2030 in 2017). This is a hugely important issue and deserves a lot of attention, especially because women and girls with disabilities are more likely to experience violence than women and girls without disabilities[footnote 14]. However, there is a risk that GBV and SRH are considered the main or only women’s concern.

Many other commitments use terms or key words like ‘empowerment’, ‘meaningful participation’ and ‘integrating women’s issues’ which will require clarification for each given context. Gender equality appears only 4 times in commitments (by SIDA, Philippines Council of Disability Affairs, Korea International Cooperation Agency and UNESCO). Other commitments mention women’s rights and empowerment as well as their increased participation, but often in a specific thematic context and in combination with needs. While this is not negative, gender equality is a status that should transcend thematic areas and is more than meeting a selection of needs.

‘Intersectionality’ was only mentioned once directly (by the Ford Foundation) and indirectly once (by UN Women in referring to mainstreaming gender, age and disability perspectives). This is significant as it reflects the gap in stakeholders’ understanding of and engagement with the concept of how multiple identities, for example, gender, age, disability, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, and others intersect and often result in compounded experiences of discrimination and marginalisation.

Selected commitments made regarding women and girls:

- UN Women will launch a corporate strategy for the empowerment of women and girls with disabilities, and committed that by 2021, 80% of their country programmes will include a focus on women and girls with disabilities

- Open Society Foundation committed to ensure that 75% of their programming on women and girls will consider the needs of women and girls with disabilities

- The Government of Ghana will include provisions on women and girls with disabilities in its Affirmative Action Bill

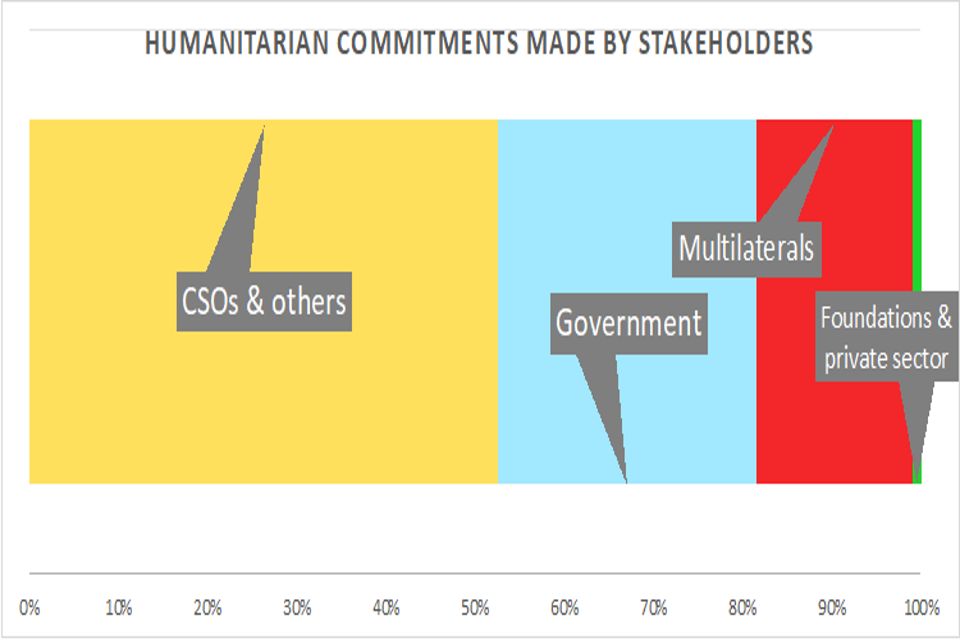

Conflict and Humanitarian Contexts

There were 97 commitments made under this theme representing 10% of all commitments. All but one category of stakeholder made commitments regarding this theme; no commitments under this theme were made by foundations.

Humanitarian commitments made by stakeholders

Almost a third of the 97 humanitarian-themed commitments were made by national governments and almost a fifth by multilateral organisations. 16 governments, seven donors and 10 multilaterals committed to strengthening disability inclusive humanitarian approaches.

Humanitarian-themed commitments made at GDS18 indicate a clear desire to strengthen disability inclusion across the humanitarian sector. Almost two-thirds of the humanitarian- themed commitments made are targeted at the global level, suggesting a recognition by key actors that disability currently is not routinely considered within humanitarian activities. The strong focus from a broad range of actors (including EU-CORD, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNDP) on setting global standards and guidelines for disability inclusion in humanitarian activities further suggests that the focus remains concentrated for many actors at the policy-level. Multiple commitments coalesce around the IASC Guidelines on the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action, Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action and the Humanitarian inclusion standards for older people and people with disabilities.

A significant cohort of humanitarian-themed commitments made at GDS18 look beyond global standards, to translating policy into action. While many of these commitments lack specificity, commitments point to a desire to share knowledge and best practice (e.g. the commitment made by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM)), to build the capacity of implementing staff and partners (e.g. commitments made the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and IOM) and to deliver services that include persons with disabilities (e.g. commitments made by UNFPA and WHO).

Selected commitments made regarding conflict and humanitarian contexts:

- DFAT will provide $16.4 million over 3 years to support disability inclusive action in response to the Syria Crisis

- The Government of Jordan will provide a safe environment for all students with disabilities including Syrian refugees

- UNICEF will strengthen the inclusion of children with disabilities in humanitarian action in 35 countries by 2021

- UN OCHA will establish a road map to include issues of persons with disabilities in coordination tools and mechanisms by end 2018

- The World Bank will ensure that projects financing public facilities in post- disaster reconstruction efforts are disability inclusive by 2020.

Data disaggregation

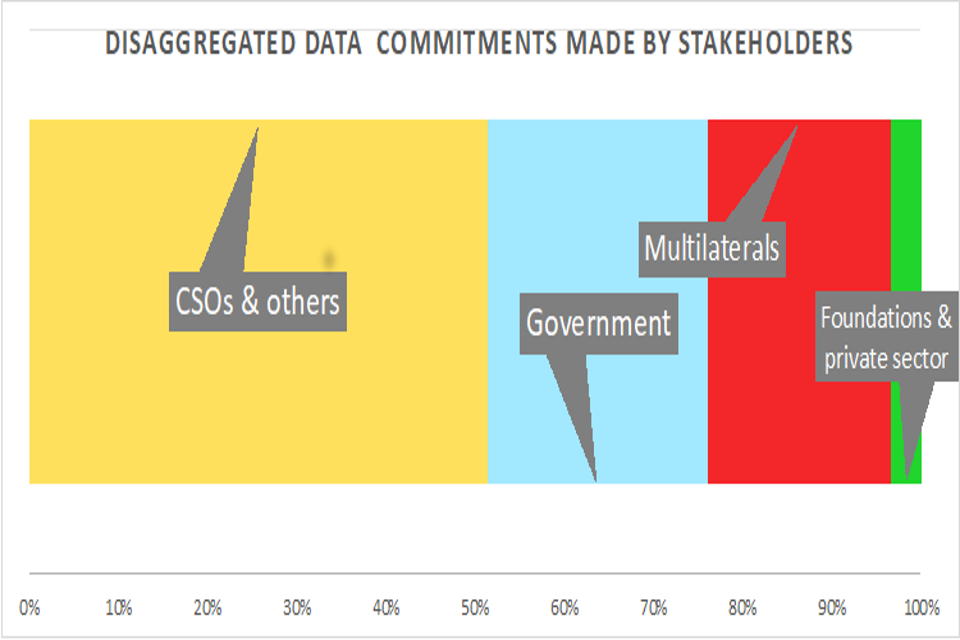

There were 117 commitments made under this theme representing 12% of all commitments. All stakeholder groups made commitments regarding data disaggregation.

Disaggregated data commitments made by stakeholders

Twenty nine commitments are made by governments (of which 8 came from the donors, including DFID) compared with 59 made by civil society organisations. There were 24 commitments made by multilateral organisations (including 5made by UNESCO alone) and 4 made by the private sector and foundations combined.

Lots of agencies have taken up the challenge of collecting disability disaggregated data with a significant proportion of them willing to support implementation of the Washington Group Questions which should enable the collection of considerably more comparable data from government to project level. In fact, ten national governments have committed to using the Washington Group Questions, seven of which will include the questions in their national population census within the next 5 years (Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Nigeria, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Zambia). Inevitably, this will help the donor community to understand the extent to which persons with disabilities are participating in programmes and should lead to more active programming for inclusion. However, there are also potential gaps – collecting disability data is one step but the extent to which this data will then be analysed and used in future programming remains unknown. It is also not evident from the commitments alone, the extent to which it will be possible for the development community to identify and eliminate barriers to inclusion. In this respect the commitments from Ministry of Social Welfare Relief and Resettlement in Myanmar are worth highlighting since their intention is to undertake a disability survey ‘…with direct input from and/or in partnership with organisations of persons with disabilities.’

Another feature of the commitments is the lack of recognition of the diversity of experiences faced by persons with disabilities. Very few of the commitments really address disability from an intersectional perspective – for example looking more specifically at the differential outcomes for older people with disabilities; young people with disabilities; girls or women with disabilities, or those from different ethnic backgrounds. There is still a tendency to refer to people with disabilities as a single group although some agencies such as UNESCO (mention girls and women), UNICEF (mention children), IOM (sex disaggregation), and UN Women (reference to girls and women) have started to raise more complex understanding by highlighting intersectional identities.

Finally, the inclusion of commitments that reference the establishment of disability databases, registries or ID systems raise some challenges. From the commitments alone, it is not possible to understand the intentions behind such systems nor is it possible to discern the extent to which the rights of people with disabilities would be upheld by such processes.

Selected commitments made regarding data disaggregation:

- ten national governments committed to using the Washington Group Questions on disability status in upcoming national censuses or surveys (Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia), of which seven will include the questions in their national population census in the next 5 years (Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Nigeria, Malawi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Zambia)

- at least 3 bilateral and 12 multilateral organisations or bodies have committed to promote use of the Washington Group Questions (including DFAT, Finland Ministry of Foreign Affairs, DFID), World Bank Group, ILO, UNICEF, UNFPA, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNDP, UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), OHCHR, IOM, IRC, the Washington Group)

- four national governments have committed to undertake a national disability survey or similar study on the situation of people with disabilities (Bangladesh, Myanmar, Mozambique and Andorra)

- seven members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) committed to using the new DAC disability inclusion marker (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, Italy, Sweden and the UK)

- The World Bank Group, the Government of Kenya, and DFID signed up to the Inclusive Data Charter

Appendix 2: Country level case studies

Case study developed by Users and Survivors of Psychiatry Kenya (USP-K)[footnote 15].

Users and Survivors of Psychiatry Kenya (USP-K) is a national membership organization whose major objective is to promote and advocate for the rights of persons with psychosocial disabilities in Kenya.

To create this case study USP-K conducted a total of 10 interviews consisting of 3 government ministries, 1 constitutional commission, 4 organisations of persons with disabilities, 1 international development NGO and 1 organisation for persons with disabilities. We also conducted 2 focus group discussions at the county level with 2 groups of persons with disabilities in Kiambu and Nyeri Counties.

The Government of Kenya’s role as co-host of the Summit and the specific commitments the government made has helped to generate significant momentum in Kenya around disability inclusion.

While it is too soon for the Government of Kenya to have delivered their commitments (delivery of the commitments is set for after 2019), several significant steps toward their delivery have been taken. The Government of Kenya has launched the National Action Plan on the implementation of the Global Disability Summit Commitments 2018, providing a roadmap for the delivery of all Summit commitments. An Inter-Agency Coordinating Committee (IACC) has also been launched to coordinate and monitor the implementation of the National Action Plan. The IACC consists of representatives from Government Ministries, Departments and Agencies, Constitutional Commissions, Civil Society Organisation’s and Disabled People’s Organisations.