Scope of the GCA investigation and the investigation process

Published 25 March 2019

4. Paragraph 16 of the Code

4.1 Paragraph 16 of the Code (Duties in relation to De-listing) states:

“Prior to De-listing a Supplier, a Retailer must:

- provide Reasonable Notice to the Supplier of the Retailer’s decision to De-list.”

4.2 Paragraph 1 of the Code states:

“De-list means to cease to purchase Groceries for resale from a Supplier, or significantly to reduce the volume of purchases made from that Supplier. Whether a reduction in volumes purchased is ‘significant’ will be determined by reference to the amount of Groceries supplied by that Supplier to the Retailer, rather than the total volume of Groceries purchased by the Retailer from all of its Suppliers.”

4.3 Paragraph 1 of the Code also states:

“Reasonable Notice means a period of notice, the reasonableness of which will depend on the circumstances of the individual case, including:

- the duration of the Supply Agreement to which the notice relates, or the frequency with which orders are placed by the Retailer for relevant Groceries;

- the characteristics of the relevant Groceries including durability, seasonality and external factors affecting >their production;

- the value of any relevant order relative to the turnover of the Supplier in question; and

- the overall impact of the information given in the notice on the business of the Supplier, to the extent that this is reasonably foreseeable by the Retailer.”

4.4 On 27 November 2014 I published interpretative guidance on De-listing to assist with the interpretation of paragraph 16 of the Code (the De-listing Guidance). The purpose of the De-listing Guidance was to assist with the interpretation of the language used in paragraphs 1 and 16: “significantly to reduce the volume of purchases made” and “Reasonable Notice”. I noted in the De-listing Guidance that it was not acceptable for the Retailers to adopt a “one size fits all” approach. I stated that the guidance was not intended to be exhaustive, but that I hoped it would be used to inform and facilitate meaningful dialogue between Retailers and Suppliers when De-listing was contemplated.

4.5 In relation to the meaning of “significantly to reduce the volume of purchases made”, the De-listing Guidance set out my view that the plain English meaning of significantly ought to be applied. This would vary from one situation to another, and was always referable to the amount of groceries supplied by the particular Supplier in the situation being considered. I suggested various factors that should be considered in each case by the Retailer. These included whether the groceries supplied are branded or own-label; whether the Supply Agreement is sole or exclusive to the Retailer; whether the groceries supplied are a niche product; the speed, ease and extent to which the Supplier can switch to supplying an alternative customer without loss of profit; the extent to which production of the groceries by the Supplier can be controlled, for example it might be difficult for a Supplier of fresh produce to cease supplying without adequate notice; and certain external and well-publicised factors affecting demand which may determine or significantly direct a Retailer’s action and the applicable timescales.

4.6 Clearly, then, to stop buying products altogether from a Supplier would be significant, as could be reducing the overall volume by turnover or across all lines; but so might reducing the number of product lines stocked from that Supplier, or the volume of certain lines, permanently or on a seasonal or short-term basis. Each case would depend on its facts as to significance.

4.7 In relation to the meaning of “Reasonable Notice”, I noted in the De-listing Guidance that this would vary from case to case but some factors that could be considered included the consistency with which the Retailer applies its De-listing policy; the overall impact of the information given in the notice on the Supplier’s business, to the extent that this is reasonably foreseeable by the Retailer; relevant contracting history or practice between the parties; for how long the Supplier has supplied the Retailer; the reasonable expectations of the parties; the length of time taken to produce the groceries; any relevant joint planning activity and whether the Supplier had been forewarned of possible De-listing.

4.8 The De-listing Guidance also noted that where a Retailer is planning a range reduction or other comparable initiative, communication with Suppliers at both planning and implementation stages will be important, as will the authority given to individuals within the Retailer to negotiate on a case-by-case basis. Retailers often will not be aware of all the factors they need to take into account. Clearly then, only by speaking to or otherwise obtaining relevant information directly from Suppliers will they be in a position properly to consider individual Supplier circumstances.

4.9 I published supplementary guidance on De-listing in August 2016 (the Supplementary De-listing Guidance). This was intended to be of benefit to the fresh produce sector in particular, but would apply equally to any relevant De-listing situation. Fresh produce Suppliers may experience extreme effects of certain conditions of supply, such as long production cycles, short shelf life and volatile demand. Suppliers in other sectors may experience significant effects of similar conditions of supply. In each case, these will help determine the appropriate level of certainty as to the risks and costs of trading and hence the reasonable period of notice in a particular De-listing situation. In short-term seasonal, fixed term or rolling contracts, for example, the Supply Agreement should set out key decision points about the next season’s supply and I would consider the reasonableness of notice given by reference to the clarity of the Supply Agreement as to these key decision points.

4.10 The Supplementary De-listing Guidance again underlines the importance of a Retailer communicating effectively to each Supplier what its volume is likely to be to enable Suppliers to manage their production and supply risks.

5. Paragraph 3 of the Code

5.1 Paragraph 3 of the Code (Variation of Supply Agreements and terms of supply) states:

“If a Retailer has the right to vary a Supply Agreement unilaterally, it must give Reasonable Notice of any such variation to the Supplier.”

5.2 In January 2014 I published a case study on my website about Co-op seeking Supplier payments for failure to meet target service levels. This clarified that requesting Supplier payments for failure to meet target service levels not set out in the relevant Supply Agreement was not consistent with paragraph 3 of the Code.

5.3 On 20 June 2016 I published another case study clarifying paragraph 3 of the Code. A different Retailer had requested lump sum payments from Suppliers which were not supported by the Supply Agreement. I noted that while Retailers retain the right to vary a Supply Agreement unilaterally, there must be provision for this in the Supply Agreement and reasonable notice must be given to the Supplier. The notice period given was four weeks in most cases and sometimes less. I concluded that if the Retailer was making unilateral variations to Supply Agreements, it had not given reasonable notice of the variation in each case. I also noted that swift action by a Retailer in response to regulatory interest from the GCA can in some circumstances avert an investigation, because to investigate may become disproportionate in the circumstances.

5.4 On 4 September 2017 I published a further case study on paragraph 3 of the Code. This related to another of the Retailers implementing a project to deliver cost price savings and range reductions which resulted in variation of Supply Agreements. In this case the variation took the form of Retailer requests to Suppliers to make significant financial contributions to keep their business with the Retailer, with very little time allowed to agree to the proposed changes. I concluded that the Retailer had made unilateral variations to Supply Agreements or had made variations without reasonable notice being given. I noted again that while Retailers retain the right to vary a Supply Agreement unilaterally, there must be provision for this in the Supply Agreement and reasonable notice must be given to the Supplier. The point of interpretation had accordingly been made quite clear. Again I noted that swift action by a Retailer in response to regulatory interest from the GCA can in some circumstances avert an investigation, because to investigate may become disproportionate in the circumstances, especially if things have largely been put right; provided the learning points can be shared with the sector as a whole for the benefit of Suppliers and consumers.

6. Paragraph 2 of the Code

6.1 Paragraph 2 of the Code (Principle of fair dealing) states:

“A Retailer must at all times deal with its Suppliers fairly and lawfully. Fair and lawful dealing will be understood as requiring the Retailer to conduct its trading relationships with Suppliers in good faith, without distinction between formal or informal arrangements, without duress and in recognition of the Suppliers’ need for certainty as regards the risks and costs of trading, particularly in relation to production, delivery and payment issues.”

6.2 I have consistently applied paragraph 2 of the Code to help me to interpret the practice- specific provisions. It goes to the heart of the way a Retailer treats its Suppliers, and understanding it is vital to effective compliance risk management. In the June 2016 case study I determined that the Retailer had effectively required payments from Suppliers, even though these were framed as requests. Once the Retailer was alerted to the issue, these became genuine negotiations between the Retailer and Suppliers. The Retailer ensured by its swift and comprehensive action to put in place additional training, more robust internal processes and increased audits, as well as checking at year end to ensure no similar activity had occurred, that it could sufficiently assure me as to its Code compliance for the future.

6.3 In the September 2017 case study, another Retailer again conducted negotiations with Suppliers in a way that was not Code-compliant, because of aggressive tactics, inflexible demands, very short time periods for Suppliers to respond, and the threat of De-listing in the background, which was clearly implied if not expressly stated. In this case study, I noted in particular that Retailers should ensure that their legal, compliance and audit functions are sufficiently connected to commercial initiatives that they work effectively together to ensure Code compliance. Moreover, individuals within Retailers should be sufficiently aware of the Code and empowered in their roles meaningfully to challenge any commercial or other initiative by the Retailer which may put them in breach of the Code. This extends beyond the Code Compliance Officer (CCO) role and the legal and compliance function of the Retailer, and includes individuals at all levels in the business.

The investigation process

7. In the period from late 2015 until my decision to launch the investigation on 8 March 2018, I raised and escalated with Co-op senior management, as well as its CCO, my concerns about its compliance with paragraphs 16, 3 and 2 of the Code. I received reports, held regular meetings with Co-op, and we exchanged correspondence. I have summarised this activity below, to the extent it is within the scope of this investigation.

8. Escalation of issues raised under paragraph 16

8.1 In 2016 I received information from Suppliers raising concerns about De-listing decisions being made by Co-op, including whether sufficient notice was given of De-listing. I raised the issue with Co-op and was provided with a copy of its De-listing guidance. This contained “relevant notice periods” of a minimum of 12 weeks for own-label products and two weeks for branded products. I expressed my concerns to Co-op about these periods, in particular that two weeks was unlikely to be reasonable except in very limited circumstances. Co-op advised me that it would review these minimum periods but sought to reassure me that buyers had been trained to consider De-listing on a case-by-case basis in accordance with the De-listing Guidance.

8.2 In 2017 I received further information from Suppliers that Co-op was applying what appeared to be standard notice periods of De-listing of two weeks and 12 weeks and in one case gave no notice at all of De-listing. I wrote to Co-op reiterating my concerns. I asked Co-op to tell me what steps it was taking to ensure that De-listing was conducted in compliance with the Code and what remedial action was being taken for any Suppliers already adversely affected by De-listing without reasonable notice. Co-op responded that it was reminding its buying team to decide reasonable notice on a case-by-case basis, and that it was reviewing its current activities to ensure compliance with the Code, including having undertaken an initial review to identify Suppliers to which reasonable notice might not have been given. Co-op subsequently explained that it was undertaking a further, more detailed assessment of the Suppliers it knew to have been affected.

8.3 It also became clear from what Co-op told me that it might not have identified all relevant reductions in volume as significant hence engaging the De-listing provisions of the Code. This was particularly apparent in the way Co-op described to me its range review activity, especially in conducting its “Right Range Right Store” initiative. Range reviews are regularly conducted by most Retailers to ensure that they are stocking the most appropriate products. The Co-op Right Range Right Store initiative was a large-scale range review programme that had been developed by Co-op but my experience is that Suppliers did not necessarily understand it to be a special programme any different from any other range review activity.

8.4 Moreover, having seen the training offered by Co-op to its buyers and others on Code compliance, I was very concerned that parts of the training were incorrect or misleading, especially in relation to reasonable notice, the suggestion of minimum notice periods and the information given to buyers about significance.

8.5 I continued to engage with Co-op on these issues but became increasingly concerned that Co-op was failing adequately to resolve them. It was not clear to me how Co-op had sought to review the potentially non-compliant De-listings, what this exercise had revealed and what was being done comprehensively to put things right for Suppliers. It was also not clear what steps if any Co-op was taking to ensure there was no repetition of the issues in the future. I expressed particular concern to Co-op about De-listing where there was a failure to give reasonable notice which had arisen from inadequate systems and processes and where the failure may also have arisen from more persistent cultural and behavioural patterns.

8.6 Co-op accepted that a “two week minimum notice period is unlikely to be reasonable notice”. Further, when in January 2018 Co-op provided me with an update from its own supplier survey, this indicated a high proportion of incidents where Suppliers had been given only six weeks’ notice of De-listing or less including instances where no notice was given. The figures provided from an internal audit of compliance with Co-op policy on De-listing also gave me significant cause for concern: 80% of branded goods and only 3% for own-label were in line with Co-op policy.[footnote 1]

8.7 Co-op also accepted that it had made a number of errors in its interpretation of paragraph 16 of the Code and had failed to identify circumstances when significant reductions in volume of products ordered might be occurring. Co-op acknowledged that it had not responded quickly enough or adequately to the need to change its policy and practice relating to De-listing. Co-op stated that it had “done too much, too quickly and not properly engaged with or embedded the Code”. It apologised for letting down its “suppliers, members and customers”. In the meeting following the provision of additional information in January 2018 Co-op informed me that it could not ascertain the extent of the problem and did not have readily available the information about which Suppliers had been De-listed.

8.8 The regulatory position was clear from my published guidance, both as to the paragraph 16 requirement of reasonable notice to be determined on a case-by-case basis and its application to significant reductions in volume. Equally clear was the wider point about how Retailers should manage their businesses in a way that ensured Code compliance. Accordingly I reached the view that an investigation would enable me to gain greater understanding of the totality of the conduct in relation to De-listing, and that it would offer the best prospect of an evidence-based assessment as to whether the Code had been broken and if so, of comprehensive remedial action for the future.

9. Escalation of issues raised under paragraph 3

9.1 In August 2016 I received information from Suppliers raising concerns about charges levied by Co-op where it deemed there had been quality issues with groceries delivered into depots (quality control charges). I was informed that these charges had been applied around November 2015 and were unexpected and charged without notice. I raised the issue of charges with Co-op and in particular that charges had been applied without prior notification having been given to Suppliers. When responding to my question, Co-op instead provided me with information relating to a different type of charge, for customer benchmarking tests which were carried out to compare competitors’ products with Co-op own-label products. Co-op informed me that it had provided Suppliers with three weeks’ notice of the introduction of the benchmarking charges in July 2015. Co-op subsequently confirmed in relation to depot quality control charges that its terms and conditions were amended in 2013 to allow for these but that charges had not been levied until 2015. Given the time lapse, Suppliers may have assumed no charges would be applied. Co-op initially informed me that in 2016 it had given Suppliers two weeks’ notice of the removal of a £200 cap on the maximum charge per delivery but subsequently confirmed that this was done in July 2015.

9.2 I informed Co-op that on the information it had provided and for both types of charge it had identified, reasonable notice may not have been given as to when they would be applied, sufficient to enable Suppliers to factor the additional costs into their negotiations. I was concerned that paragraph 3 of the Code might have been broken and asked Co-op to consider appropriate remedial steps for any affected Suppliers. In March 2017, Co-op confirmed to me that it had undertaken a review to identify the Suppliers affected by the charges and the amounts charged. Co-op accepted that the notice it had given was unreasonable and decided to issue a number of refunds.

9.3 I engaged with Co-op regarding the remedial steps it was undertaking in order to assess whether my concerns were being sufficiently addressed. I saw that its approach to identifying affected Suppliers and its methodology for calculating refunds were inadequate and demonstrated a failure in its understanding as to what reasonable notice meant for the purposes of the Code.

9.4 In particular, Co-op appeared not to have considered whether the notice given enabled Suppliers to renegotiate their cost prices to take account of the increased costs of supplying Co-op. Depending on whether or not Suppliers were on fixed-cost contracts and if so, the duration of each of them, it was likely that different periods of notice would be reasonable in different circumstances.

9.5 In October 2017, I informed Co-op that despite my intervention, I had not seen material improvements in its compliance with this provision of the Code. Several published case studies had made the regulatory position clear, both as to the paragraph 3 requirement of reasonable notice and the wider principle about how Retailers should manage their businesses in a way that ensured Code compliance. I expressed my concern that the failure to give reasonable notice may have arisen from an absence of communication between Co-op and its Suppliers at the time the charges were applied, as well as from the system adopted by Co-op for the application of charges.

9.6 Co-op acknowledged that its oversight of the way in which charges had been applied had been “fragmented” and that those responsible for applying charges “did not have the appropriate level of training on the Code.” It accepted that in respect of the introduction and increase in depot quality control charges, “the 2 week window was unreasonable” and in respect of benchmarking charges, “Suppliers could reasonably have expected more notice of these charges.” Co-op acknowledged that it had “introduced Depot Quality Check (QC) and Benchmarking charges without reasonable notice as we did not provide suppliers with sufficient opportunity (where any opportunity existed) to factor these charges into their cost prices and renegotiate the terms and commercial arrangements of supply.” Accordingly, it recognised that “in this area we have to do more to demonstrate our compliance with the spirit of the Code.” Co-op confirmed it would reimburse all quality control charges and benchmarking charges made up to the point of a Supplier’s contract renegotiation date following the introduction and/or increase of the charge. More generally Co-op acknowledged that “to deliver and sustain the improvements we need will require significant changes to our culture, systems and ways of working and it will take time to identify and embed these.”

9.7 Despite this, I remained unconvinced that Co-op had identified all relevant Suppliers, calculated refunds appropriately, or taken the steps necessary to prevent charges being implemented without reasonable notice in the future, especially since I understood that Co-op was seeking to re-introduce the charges with immediate effect. Accordingly I reached the view that an investigation would enable me to gain greater understanding of the totality of the conduct failures in relation to the application of benchmarking and depot quality control charges, and that it would offer the best prospect of an evidence-based assessment as to whether the Code had been broken and if so, of comprehensive remedial action for the future.

9.8 Moreover, the factors noted in the published case studies in June 2016 and September 2017 about how in some circumstances a Retailer may by swift, comprehensive action avert an investigation were not present in this case. Co-op had undertaken significant work but had not been able to explain to me what had gone wrong and why. Nor had Co-op handled its enquiries and activities in relation to the concerns I raised in a way that gave me sufficient confidence that it had either repaid charges which it should not have levied or would make systemic changes to ensure Code compliance in the future.

10. The decision to launch an investigation

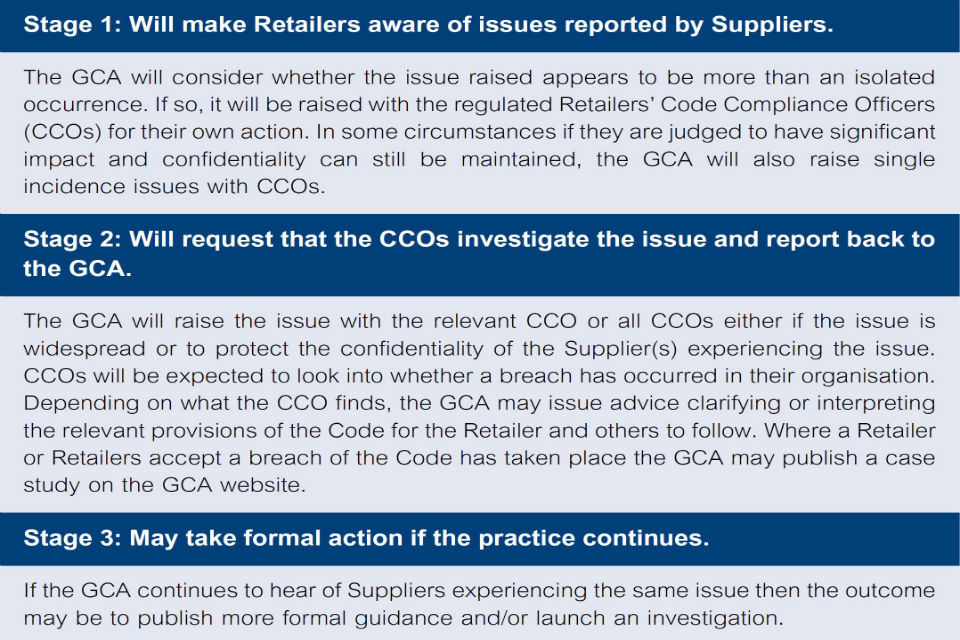

10.1 I have developed an effective, modern approach to regulation, with collaboration and business relations at its core. When Code-related issues are raised with me I escalate them as follows:

Three stages of Code escalation. Stage 1: will make Retailers aware of issues reported by Suppliers. Stage 2: Will request that the CCOs investigate the issue and report back to the GCA. Stage 3: May take formal action if the practice.

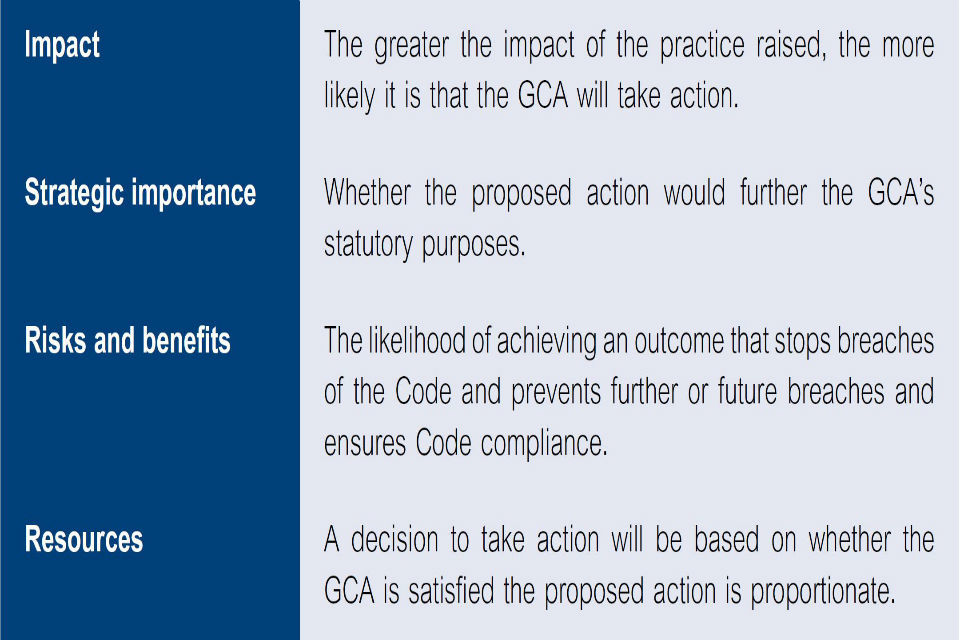

10.2 I have also published in my Guidance four prioritisation principles, which enable me to target my resources effectively and proportionately. They assist me in deciding whether to initiate, and subsequently whether to continue an investigation. They are:

The four prioritisation principles are: Impact, Strategic importance, risk and benefits and lastly resources.

10.3 I took all of these factors into account when deciding whether to launch an investigation into Co-op. I considered the information submitted to me and assessed it in line with my published Guidance. I held a reasonable suspicion that the Code had been broken by Co-op by some of its practices in relation to De-listing and the introduction of benchmarking and depot quality control charges. I escalated my concerns in accordance with my published collaborative approach to regulation. There was a period of intense engagement in which Co-op accepted that it had fallen short of my expectations. I am satisfied that it was proportionate in all the circumstances to investigate. I concluded that an investigation was necessary to fully understand and to determine, which as GCA I am required in appropriate circumstances to do, the extent to which the Code may have been broken, the impact on Suppliers and the root causes of the issues, so that they could be comprehensively put right for the future. Accordingly, I took the decision to launch an investigation into Co-op compliance with paragraphs 16, 3 and 2 of the Code.

11. Notice of Investigation

11.1 Steve Murrells, Group CEO of Co-op, was notified of my decision by telephone on 7 March 2018 and in writing on the same day. The Notice of Investigation was published on my website on 8 March 2018. As part of the Notice of Investigation, I made a public call for any evidence relevant to my determination of whether Co-op had broken paragraphs 16 and 3 of the Code in the ways described in the notice, and evidence of the effect that this had on Suppliers. The purpose of the call for evidence was to give any organisation or individual the opportunity voluntarily to provide me with information relevant to the investigation. Material which I received in response to the public call for evidence assisted me in deciding what requests for information I needed to make and ultimately, whether or not Co-op had broken the Code.

12. Period under investigation

12.1 I decided to investigate Co-op conduct between January 2016 and 8 March 2018, the date of the Notice of Investigation. I stated in the Notice of Investigation that my main focus would be on the period between summer 2016 and summer 2017 when the Right Range Right Store programme was underway. When deciding on the appropriate period of time to investigate I took into account the need to cover a time period that was sufficiently long to address a potentially longstanding issue and to determine whether any behaviour was repeated, and possibly systemic. I balanced this with the need for the period under investigation to be proportionate and not to capture events that would have inevitably become historic in a fast-moving business such as groceries retail. I decided that early 2016 was an appropriate point from which to commence the investigation bearing in mind the information I had received from Co-op and Suppliers. 8 March 2018 was the conclusion of the period under investigation as it was the date of launch of the investigation.

12.2 My findings as to whether or not the Code has been broken are not based on any information relating to Co-op practices other than during the period under investigation. I have nonetheless had regard to behaviour by Co-op before the period under investigation in order properly to understand the conduct being investigated. I have received information from Co-op about the steps that it has taken in response to my escalation of the issues which were later investigated and its continuing action while I have been carrying out my investigation to get to the bottom of what happened and to put right practices for the future. I have recorded this and have been mindful of it when determining whether and if so how I should apply my enforcement powers as a result of this investigation.

13. My powers to issue requests for material relevant to my investigation

13.1 The Act provides me with the power to compel persons to provide documents or information to me for the purposes of an investigation. This includes a power to require information to be provided orally. Requests may be made of an entity or person, including Retailers, Suppliers, customers and third parties. An intentional failure to comply with the request without reasonable excuse is a criminal offence.

13.2 I have exercised these powers when seeking disclosure of material during the course of my investigation. Requests for information were issued to Co-op, Co-op employees and to a number of Suppliers to obtain information and material. I have ensured that requests for information were proportionate by requiring disclosure of sufficient information to conduct a thorough investigation while seeking to minimise the burden on the recipient of my request. I am extremely grateful for the co-operation of and assistance provided by those who responded to my requests. Further details about these requests are set out below.

14. Requests for information from Co-op and its employees

14.1 I issued two requests for information to Co-op during the course of my investigation. I explained to Co-op that my information requests would be made in stages and would be targeted.

14.2 I issued the first request for information to Co-op on 21 March 2018. In response, Co-op provided a narrative response and documentation on 18 April 2018.

14.3 On 23 May 2018, I wrote to Co-op and asked for clarification of some of the material that had been provided in its response and set out material that I believed was missing. In response, on 6 June 2018 Co-op provided me with a further narrative response and documentation and indicated that a further set of materials would follow. On 15 June 2018 I received a further narrative and accompanying documents.

14.4 On 13 September 2018, I wrote to Co-op to ask for the information which was required to complete its response to my first request for information. I also made a second request for information. On 11 October 2018 Co-op provided me with a narrative response and further accompanying documentation. In this correspondence Co-op also notified me that it was conducting a further review of whether additional refunds for depot quality control charges were due to Suppliers. On 21 January 2019 it informed me that it had identified 34 Suppliers to which it would be providing further refunds. I requested additional information about the rationale for these refunds and which Suppliers were affected, which was provided to me in February 2019.

14.5 Having reviewed the material provided by Co-op, I decided that I required further information from a number of individuals employed at Co-op to ensure that I had the information I needed to carry out my assessment of whether Co-op had broken the Code and if so, the extent to which it had been broken.

15. Requests for information from Suppliers

15.1 I also issued requests for information to Suppliers which I considered might have relevant information that would assist my investigation. In some cases I exercised my statutory power to request that representatives from the Supplier attended a meeting with me to discuss the information held by the Supplier and its experiences with Co-op during the period under investigation. I sought this information to obtain a rounded understanding of Co-op behaviour in relation to paragraphs 16, 3 and 2 of the Code. I chose the Suppliers to include different- sized Suppliers, from different parts of the UK and a range of product categories covered by the Code. The Suppliers included both those who supplied branded and own-label products to Co-op.

15.2 I am satisfied that these Suppliers represented a broad cross section of companies that supply groceries to Co-op. These Suppliers provided me with a significant quantity of evidential material in response to the requests. Suppliers were asked to provide me with narrative summaries to explain the context of any documentation they provided.

15.3 The meetings that took place with Suppliers were of great assistance to me in understanding and expanding upon the information provided in writing. They also gave me a much better understanding of each of the Suppliers’ relationships with Co-op. I had the opportunity to review the written material from each Supplier before each meeting. On some occasions I asked the Suppliers to provide additional information after the meeting where I had further queries. At all times I reassured Suppliers of my confidentiality obligations in relation to all the material they provided to me.

16. Confidentiality

16.1 I have a statutory duty to keep certain information confidential. This includes any information that I think might cause someone to think that a particular person has complained about a Retailer failing to comply with the Code. 16.2 I take this duty very seriously. I have sought to protect the identity of any Supplier or individual, including Co-op employees, who has provided me with information during the course of this investigation. No Supplier or individual is named in this report or described in a way that might enable them to be identified.

17. Information I received during the course of the investigation which was outside its scope

17.1 Any information that I have received during the course of my investigation that does not fall within the scope of the investigation has not been considered for the purposes of my findings. Consistent with my published approach, I am retaining this information for consideration as part of my usual engagement with the Retailers and may feed some or all of this into my collaborative work.

-

Co-op informed me when commenting on this report in draft that the document in which it presented this information to me was itself incorrect. The correct position, Co-op now says, is that these figures were assessing compliance against its new, January 2018 policy, not the previous one, in July 2017. ↩