Fight or flight? How ‘stuck’ schools are overcoming isolation: evaluation report

Published 8 January 2020

Applies to England

Executive summary

Ofsted exists to independently inspect and report on standards in education and care. Across the country, we see schools that improve, schools that decline and schools that continue to deliver good standards of education. But hidden behind this is a set of schools in which children have been failed for too long.

In some pockets of the country, 2 whole cohorts of children have gone through all their primary or all their secondary school life without ever attending a good school – that’s 13 years or more. At the end of August 2019, there were still an estimated 210,000 pupils being educated in stuck schools. Despite the system of support, intervention and inspection designed to improve schools, nothing has changed for these children.

This is not good enough for any child, but it is particularly concerning for these children, who are more likely to live in deprived areas than children attending other schools. Poor education is not an inevitability of poor communities: the majority of schools in the most deprived areas have shown that they can provide good or outstanding education despite the challenging contexts in which they work.

However, some of these good or outstanding schools have not always been so. Some of them have had difficult journeys with many different forms of intervention and support, and many different leadership strategies, finally coming together to make an impact. The reasons that they have improved have been under-investigated and are therefore far from clear cut.

This report explores why some consistently weak schools are able to improve while others are not, so that the whole system can then work together to transform education for these children. It is not intended to apportion blame or leave the problem at schools’ doors alone. Indeed, the whole school and accountability system – of which inspection is a part – has some responsibility for the lack of progress in these schools. This report is a call to action for every part of the system, including government, councils, Ofsted, multi-academy trusts (MATs) and schools themselves, to work together better so that education can be improved for every pupil.

This report draws on research visits to 20 schools, 10 of which have been graded less than good consistently for 13 years or more and are considered as ‘stuck’. The other 10 were graded good in their last 2 inspections, but previously had 4 full inspections that graded them less than good. These are considered as ‘unstuck’. Across the country, there are 415 stuck and 65 recently unstuck schools as of August 2019. Stuck schools represent 2% of all state-funded schools in England.

The evidence collected was self-reported through focus groups and interviews. We did not attempt to independently verify the views or facts that were given to us. This means that the evidence reported should be seen as schools’ interpretation of their journey, rather than Ofsted’s view.

We found that there are no substantial differences in the reported contexts of the stuck and unstuck schools we visited. All can be viewed as operating in very challenging circumstances, in which a mixture of geographical isolation, unstable pupil populations and poor parental motivation appear to be compounding the issues for children. The fact that some schools are delivering good education despite these challenges shows that it can be done. This report explores how.

We also found no systematic differences in the level or type of school improvement support that stuck and unstuck schools have been given. All have been involved in some form of government-funded support programme, most commonly receiving advice from National Leaders of Education. The programmes have not succeeded in getting these stuck schools to good and they are not perceived to have been transformative in unstuck schools either. Ofsted has also inspected these stuck schools on multiple occasions, sometimes 6 or 7 times for stuck schools generally, without seeing substantial improvement.

Most stuck and unstuck schools stated that they had received too much school improvement advice from too many different quarters of the school system. Often, the advice was intended to help schools with their improvement strategy. However, this rarely had the intended impact. Leaders perceived that the quality of the advice itself was often lacking. School leaders also commented on a poor match between the problems of the school and the advice on offer. While many were concerned about the lack of support available following inspection, schools often welcomed the fresh thinking and impetus that independent inspection had given them. Schools did not appear to be inhibited from discussing some of the challenges of inspection during this project.

Advice and support were perceived to have a greater impact when they were built into the school or MAT’s strategy and delivered internally. This was not always possible, due to a lack of capacity within the school or MAT. When it was possible, the internal support structures that facilitated this were considered transformational. Most commonly, these support structures included revising and implementing a consistent behaviour policy and upholding high standards of teaching. These schools, typically in MATs, also had stronger systems of accountability and oversight, which were a weakness among the other schools visited.

Overall, the evidence suggests that there is enough capacity in the system to support and advise these schools. However, too little attention is given to:

- the content of the support, including whether it enables focused, effective action that responds directly to the issues identified through inspection

- whether the support is best provided internally or externally to the school or MAT

- the quality of those coordinating or delivering the support

This report highlights the need for a closer link between this research on stuck schools, Ofsted’s inspection processes and those providing school improvement support. This approach could be achieved without Ofsted directly delivering school improvement support and with it maintaining its statutory role to independently inspect and report on school quality. We are working with the Department for Education (DfE) to develop proposals to help improve education for children in stuck schools.

Introduction

Education policy in England has long been concerned with addressing the ‘long tail of underachievement’. This is commonly characterised as the underachievement of children from disadvantaged backgrounds. A number of different policies over the last 2 decades have sought to address the issue, often focusing attention on improving standards in large cities.

However, some of the worst education is delivered in communities that have been left out of improvements in economic prosperity. These are not leafy suburbs where there is a comfortable and thriving local economy, but typically in pockets of the country with a declining industry or jobs market and a lack of broader cultural opportunities. Often, these schools are in remote areas or on the very outskirts of major cities.

In some of these areas, a pupil will go through their whole primary or whole secondary school life never having attended a good school: 13 years or more. This is failure of the highest order. The whole school system has been letting down these children for over a decade.

The definition of ‘stuck’ and ‘unstuck’ schools

Ofsted has been looking at the challenge of ‘stuck schools’. A stuck school is a school (including its predecessor if it has converted to become an academy) that has had consistently weak inspection outcomes throughout the last 13 years. This means that it has:

- been judged to be inadequate, satisfactory or to require improvement in every inspection it has had between 1 September 2006 and 31 August 2019

- had at least 4 full inspections in the period

We first highlighted the issue of stuck schools in our Annual Report in 2018.[footnote 1] We focused on the number and location of these schools, their performance data and the characteristics of the pupils. We have included an update to some of these details later in this chapter.

Since then, we have also developed a definition of an ‘unstuck school’. This is a school that previously had 4 full inspections in which we graded it less than good, but it has since had 2 inspections in which it was good. This gives us a good comparison group to understand why some schools have remained stuck and others have sustainably improved.

Being ‘stuck’ is not a new type of Ofsted category, but rather a way to analyse a problem. Therefore, we will not be publishing a list of stuck schools. Of course, any formerly ‘stuck’ school that we have graded most recently as good is no longer ‘stuck’. However, until it has had 2 consecutive good inspection grades, we do not define it as an ‘unstuck’ school. It is important that the unstuck schools we are analysing have maintained their good judgements and are not yo-yo-ing.

This report builds on our knowledge base of stuck schools. We were interested in 2 main questions:

- what is the perceived impact of school improvement initiatives on stuck schools?

- what strategies have unstuck schools used to improve education?

Methodology

As much as it was possible, we wanted to create a level playing field to investigate this subject. It is clear that most stuck schools operate in very challenging circumstances. However, we know that there are many schools in similar circumstances that can and do provide a good or outstanding level of education. Limiting the influence of context on the schools we visited would allow us to focus on why some schools had improved while others had not.

To do this, we matched our list at the time of roughly 490 stuck schools to a list of unstuck schools, pairing together schools with similar contextual data.[footnote 2] For each stuck school, this produced a match with one or more unstuck schools most similar on contextual data. From this, we made a list of around 10 stuck schools (5 deemed primary and 5 secondary) from across each of Ofsted’s 8 regions, and their pairs. The pairs were often not in the same region but did have similar contexts.

We contacted the 20 schools on our list to invite them to participate in the research. If they agreed, we arranged a day for inspectors to visit the school and we contacted the relevant local authority and MATs to invite them to be interviewed by telephone or during the visit. In total, we visited:

- 8 primary schools (3 stuck and 5 unstuck)

- 2 junior schools, deemed primary (2 stuck)

- 10 secondary schools (5 stuck and 5 unstuck)

Of the 10 stuck schools, we had graded 9 as requires improvement at their latest inspection and 1 as inadequate. All of the 10 unstuck schools were graded good at their latest inspection. You can find more detail on the sample in the appendix to this report.

Each school in the sample was visited by 2 Her Majesty’s Inspectors (HMI), carrying out research rather than an inspection. In total, 3 HMI were involved in the project and one HMI went on all of the 20 visits.

During the visit, inspectors interviewed or ran focus groups with the following people:

- the headteacher

- the senior leadership team

- the governors or trustees of the MAT

- long-standing classroom teachers

The questions for focus groups and interviews were open ended and intended to help participants describe the journey of their school. Participants were prompted to recall past inspections, the different types of improvement support that they had received and their view of the effect that each of these had on the direction of the school.

We analysed the notes and transcriptions from the visits using qualitative coding software and then grouped them into the themes of this report.

Limitations of the methodology

For an in-depth, qualitative study of this kind, we had a healthy and good-sized sample of 20 schools. However, the 10 stuck schools that we visited represent just over 2% of all stuck schools and so cannot be considered representative. This study was not intended to provide a representative view of all stuck and unstuck schools, but rather to uncover schools’ perspectives of their journeys.

The strength of the methodology is that, compared with all schools, the pairs of schools had similar contexts. This means that we can directly compare the experiences of each of the schools. However, there are some limitations due to the qualitative design of the project and the nature of the schools that we visited.

The first limitation is that all the evidence was subjective and self-reported through focus groups and interviews. We did not attempt to independently verify the views or facts that were given to us. For example, if a school stated that they believed their school had improved due to a new behaviour policy, we did not seek to check this through inspection or other methods. This means that the evidence reported should be seen as the schools’ interpretation of their journey, rather than Ofsted’s view.

The second limitation is that some (though not all) of the school leaders, staff and governors we spoke to had been running or working in stuck schools for some time and their ability to look objectively at the root cause of issues was therefore reduced. Our data shows that just under half (46%) of stuck schools do not improve at their next inspection.

The final limitation is that most leaders of the stuck schools we spoke to thought that their school was on the way to getting to good. This meant that they were likely to present recent changes as positive and past changes as negative. As described above, we did not independently verify whether the schools were improving or, in the case of unstuck schools, whether any particular change had improved the school.

What are stuck schools like?

This chapter summarises information we have about stuck schools from the data and the evidence from the school visits. We found that the contexts of all the stuck and unstuck schools we visited were remarkably similar. All these schools are working in challenging areas of the country, where parents and the wider community are perceived by the schools to be disengaged in education and where geographical isolation and unstable pupil populations make good education harder to deliver.

The unstuck schools, however, are able to overcome these challenges.

We also identify 2 types of stuck schools from the data we have:

- those that are chaotic and change fatigued

- those that have a resistant and embedded culture

These categories will help those visiting stuck schools again, including Ofsted, to understand the background and culture of the schools, and therefore the possible support mechanisms that might help them improve.

Characteristics of stuck schools

There are currently 415 schools that fit our working definition of a stuck school. At the end of August 2019, there were an estimated 210,000 pupils in these schools.

There are stuck schools in all phases of education. However, it is a greater issue for secondary and junior schools than it is for primary. The figures show that these phases are over-represented in the list of stuck schools:

- 46% (189) are primary schools (compared with 72% nationally)

- 9% (37) are junior schools (compared with 5% nationally)

- 44% (181) are secondary schools (compared with 15% nationally)

The remainder are pupil referral units, alternative provision or special schools.

The majority (86%) of stuck schools are now academies, compared with 37% nationally. This is a reflection of the current government policy of academisation to support struggling schools. However, 42% of all stuck schools are new academies that have not been inspected as a new school, because the first inspection of new schools usually takes place in the school’s third year. While any school can request an early inspection, these new schools will not have had a routine opportunity to receive a judgement of good.

In turn, almost all stuck academies (95%) are part of a MAT. However, around half of these are part of MATs with fewer than 10 academies, which is similar to the proportion of all academies in MATs of this size. This is notable because it means that the scale that some larger MATs can bring to support stuck schools is not being maximised.

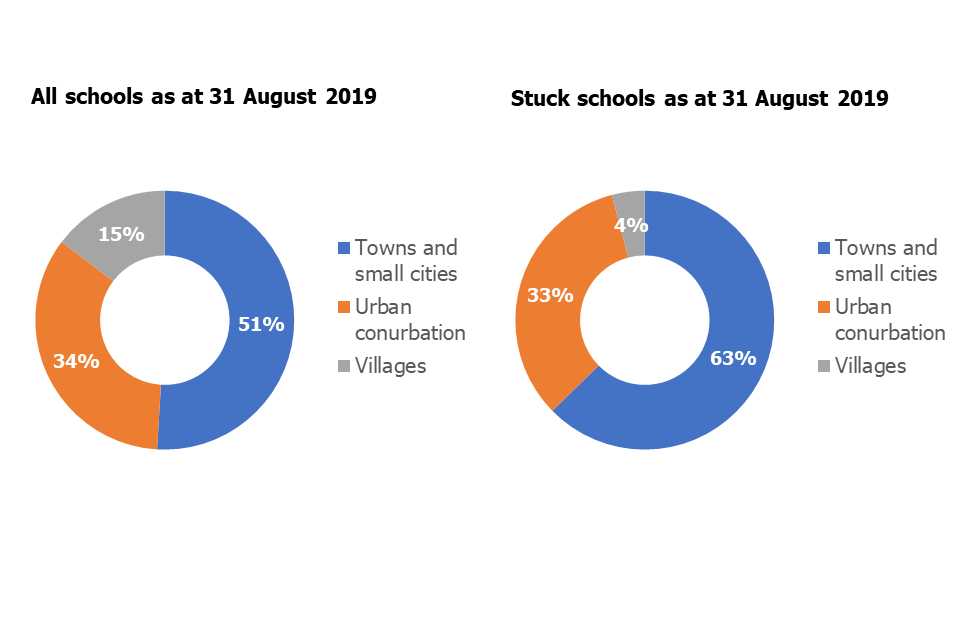

Stuck schools are disproportionally located in towns and small cities.[footnote 3] Figure 1 shows that 63% of stuck schools are in towns and small cities, compared to 51% of all schools.

Figure 1: Location of stuck schools compared to all schools

This chart compares the percentage of stuck schools in urban and rural locations with all schools. The proportion of stuck schools in towns and small cities is higher than that of all schools.

Location data does not fully capture the characteristics of the areas and local economies of stuck schools compared to other schools. Our Annual Report 2017/18 showed that stuck schools have an intake of proportionally more pupils eligible to receive free school meals than other schools. More recent research has attempted to define a new index of ‘left behind’ areas, based on data on the level of civic assets, connectedness and community engagement.[footnote 4] Around 9% of stuck schools are located in wards that are identified as ‘left behind’, compared with 4% of all schools.

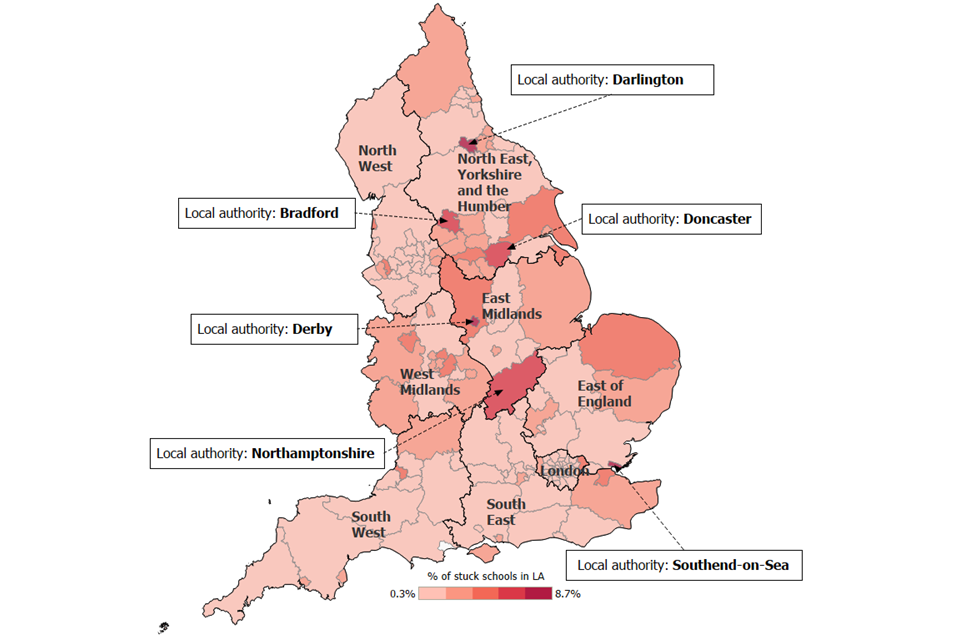

Around 12% (51) of stuck schools fall within the government’s current ‘opportunity areas’.[footnote 5] One opportunity area (West Somerset) has no stuck schools within it. The 3 local authorities with the highest proportion of stuck schools are: Derby, Southend-on-Sea and Darlington. The 3 with the lowest are: Surrey, Devon and Manchester.

Figure 2: Local authority by proportion of stuck schools

This map shows stuck schools as a percentage of all schools in the LA. The 6 LAs with the highest percentage of schools that are stuck are Derby, Southend-on-Sea, Darlington, Bradford, Doncaster and Northamptonshire.

Context of stuck and unstuck schools

All the stuck and unstuck schools we visited commented on the challenges that their pupils and communities face. This was as true for stuck schools as it was for unstuck schools: there were no obvious differences between the context in which these 2 groups of schools were operating. This was not just a function of how we matched the schools. Each pair of schools differed from every other pair on the contextual data. Nonetheless, all stuck and unstuck schools stated that they faced the same broad challenges. This shows that the challenges, while difficult, are not insurmountable.

The contextual issues were around the location and social environment of the school. A number of schools invoked the phrase ‘dumping ground’ to refer to why they had the children they had. Although this is clearly a degrading way to refer to children, it does represent a perception that these schools are expected to take a disproportionate share of children likely to struggle at school. In several cases, schools found themselves taking children on managed moves from other schools in the area because they had dwindling pupil rolls and therefore spare capacity. In one case, this amounted to 100 children in just one year (10% of their pupil intake). It was the schools’ view that children from more affluent families sent their children elsewhere.

Although many schools had concerns about funding, it was not possible to distinguish these from the wider challenges they faced in attracting a stable pupil population. Two stuck schools reported having private finance initiatives (PFI) as investment in their buildings. In one case, servicing this loan was costing 12.5% of the school’s annual budget; in the other, it was £1.3 million per annum. We did not look at school accounts, so we do not know what the latter is as a percentage of the school’s budget.

There are no substantial differences between the average percentage gain that stuck and unstuck schools will receive from the government’s new National Funding Formula (NFF).[footnote 6] The likely average percentage gain for these groups separately is between 3 and 4 per cent. This is compared to a likely average percentage gain of 5 per cent for all other schools. Although the NFF is yet to be implemented, many consider it to address historic inequalities in school funding. While not conclusive, the fact that stuck schools are not due to receive a higher percentage gain suggests that inequalities in per-pupil funding do not explain these schools’ situations.

The contextual challenges that the stuck and unstuck schools visited claimed to operate in broadly fit into 3 categories:

- poor parental motivation

- geographical isolation

- unstable pupil populations

Poor parental motivation

All the schools, both stuck and unstuck, reported issues with parents and the wider community that affected attendance, behaviour and attitudes in school. Many schools reported low levels of literacy and employment among parents. In some schools, children are reportedly sent to school hungry and allowed to stay up late on social media or to access inappropriate material on the internet. One school said that some children try to get excluded so that they can return home because they are concerned that their parents are victims of domestic abuse. Drugs and alcohol abuse within the school community are reported as commonplace.

The issues reported were considered to be intergenerational and deep rooted in all the schools we visited. Two senior leaders – one from a stuck and one from an unstuck school – commented:

‘We have generations of the community who haven’t bought into education and what it can offer.’ (Senior leader, School 7a)

‘There are a lot of cultural gaps that need filling… They were amazed when they visited [city name] to see the tall buildings.’ (Senior leader, School 5b)

Another teacher from an unstuck school commented:

‘I think we have an intake that is very low in self-worth. I think that’s how I would describe it. You know, they are very down on themselves.’ (Teacher, School 2b)

We did not attempt to verify the level of parental motivation for pupils at the schools. Therefore, these findings should only be considered as perceptions of those working in the schools.

Geographical isolation

Most schools we visited stated that they were challenged by the geographical location of their school. This boiled down to the fact that their school was not located in a desirable place to live in, or commute to, for teachers. There were multiple aspects to this problem.

Some schools lay just outside a greater city region, meaning that they felt they could not offer as attractive a salary package as schools within the city region. They saw policies such as the London teacher weighting as exacerbating issues they already had with teacher recruitment and retention, believing that good teachers were even less likely to apply for posts in the school.

Schools also felt that their communities were not sufficiently economically vibrant to attract good teachers, particularly due to lower pay. They believed that the wider cultural, social and economic opportunities available within bigger towns and cities were draining them of talent.

Others commented on the general undesirability of the location and its lack of transport infrastructure with cities. One senior leader commented:

‘Geographically we are in an awkward area. This is not a fashionable area and most people travel in. Transport links are not very good. It’s quite a difficult school to get to.’ (Senior leader, School 8b)

Some of the schools we visited benefited from Teach First trainees, but they found it difficult to retain these staff once they graduated. At least 3 schools commented on their struggle to retain Teach First graduates. One staff member commented:

‘We attract the Teach First trainees. However, once the 2 years of training are over, Teach Firsters want to move to trendier areas such as [city names] and do not want to stay in the area.’ (Headteacher, School 5a)

Again, all these issues were similar in both stuck and unstuck schools.

Unstable pupil intake

All schools commented on the unusual lack of stability in their pupil numbers and population. In most cases, schools reported that the number of pupils on roll fell as they were put into special measures, but rose when they reached requires improvement. This has a destabilising effect on funding, particularly for small schools. A sharp reduction significantly reduces funding and a sharp rise increases it – but that money is only available the following year, due to the lagged funding system.

However, schools believed that the dramatic rise and fall of pupil numbers in these schools had less to do with parental choice than local authority decision-making. Their impression was that local authorities would not send children to schools in special measures but would send pupils on in-year transfers to a school once it was graded requires improvement. This is because the school would be seen as improving as well as having spare capacity.

Once a stuck school is graded requires improvement, the number of in-year transfers it is given appears to be extremely large. One school reported mid-year moves ‘in the hundreds’, which represented at least a 10% increase in its pupil population. Other schools reported significant numbers.

It is not known why these pupils were being moved. Some schools spoke of taking a large number of pupils who had been permanently excluded. Others spoke of having a highly mobile pupil population, such as those from traveller communities, migrant communities or unstable accommodation arrangements. One school commented:

‘The other problem is the high churn of pupils due to the deprived area. With much housing benefit private rented, people move around.’ (Governor, School 6b)

Five of the 20 schools invoked the phrase ‘dumping ground’ to refer to the children they had been given. Four of these schools were stuck and just one unstuck. However, general attitudes towards pupil populations tended to be disparaging. Two senior leaders of stuck schools commented:

‘We get all the mid-year transfers and I’ve yet to see one where actually there aren’t serious concerns, issues either with safeguarding or behaviour… So, we very much feel like we’re a dumping ground. That’s soured the relationship between us and the local authority because we were expecting a bit of respite. Like, look, we’re struggling, we don’t have full teachers, we don’t have capacity, we’re in special measures, give us a bit of a break. But it was every other week.’ (Senior leader, School 4a)

‘It was the dumping ground, seen as the ‘toilet of schools’, with under capacity. That reputation is still there. [Migrant communities] are always sent to us as we have space. Students join part way through the year. This doesn’t lend itself to creating stability.’ (Senior leader, School 8a)

As mentioned, this is not an appropriate way to refer to children. A cycle of poor performance has led, over time, to parent and pupil flight, which has led to spare capacity. In turn, this has led to these schools becoming the ‘go to’ for incoming pupils and a less stable pupil population.

The 2 types of stuck schools

Although all of the schools we visited had similar contextual challenges, the stuck schools were not addressing these challenges effectively. These schools broadly fell in 2 categories:

- those that were continually changing and lacked a stable culture and staffing

- those that were not and instead had a resistant and embedded culture

However, some schools had features of both categories.

In all stuck schools, governance and oversight were reported to be very weak. Most governors felt they did not have the knowledge or skills to challenge senior leadership teams. Often, the governors were led by the school, rather than the other way around. The final chapter of this report discusses this further.

Type A: Chaotic and change fatigued

Six of the 10 stuck schools fell into this category. A school fit this category if it had at least 2 of the following attributes:

- unstable leadership

- unclear direction for school oversight

- inexperienced teacher workforce

Unstable leadership

These stuck schools have very unstable leadership, with a change of headteacher on average every one to 2 years. Leadership changes are generally more frequent than section 5 Ofsted inspections, which are every 3 years on average for all schools. One school reportedly had 14 different headteachers in the space of 10 years. Over the same period, it had 4 full inspections, showing that leadership change is not always related to inspection.

In most cases, incoming headteachers tried to establish a new culture at the school but had not been successful. We do not know enough about these former headteachers to know why this was the case. However, we have provided details of good leadership decision-making later in this report.

Unclear direction for school oversight

Leaders and staff within these stuck schools were anxious about the direction of their school. They often spent time worrying about academisation or a change in academy sponsor.

However, none of the schools we visited had transferred to a different academy sponsor more than once over the many years they had been stuck. Of the 15 academies that we visited, only 2 had transferred sponsors. Indeed, changes in headship were much more frequent than changes in academy sponsors.

Nevertheless, there was much speculation about potential transfers to new sponsors in these schools. This perception related to the speculation rather than reality of joining a MAT but was clearly distracting and demotivating for staff. One teacher in a stuck school commented:

‘In the last 7 years, we’ve had 4 headteachers. We’ve looked like we’re joining 3 different MATs.’ (Teacher, School 8a)

Inexperienced teacher workforce

These schools have a high turnover of staff, with one school reporting 60% turnover on average every year. There is a strong reliance on agency staff, new graduates and Teach First trainees.

Type B: Resistant and embedded culture

Four of the stuck schools fell into this category. A school fit this category if it had just 2 of the following attributes:

- settled leadership team

- long-standing teacher workforce

- antagonistic union voice

Settled leadership team

These schools have had the same headteacher and a similar senior leadership team (SLT) typically for around 5 years or more. During this period, they had at least 2 full inspections graded less than good. Often, the headteacher is someone who also used to be a deputy headteacher in the school and therefore has worked there for an even longer period of time.

Long-standing teacher workforce

Teachers have been working for the school for a long period of time, often decades. The headteacher and SLT have struggled to retain good teachers and many have then left. Performance management of teachers who remain at the school was reported to be poor because the SLT relies on them for having a sufficient number of classes of a certain size.

Antagonistic union voice

Although there is a helpful and constructive union voice in many schools, this is less constructive in a small number of these schools. Both teachers and leaders in at least 2 schools commented on the difficulties this created. There was a union strike in one school that we visited:

‘I met with the [specific union rep] who took a personal interest in the school. They said that if there were any restructuring or redundancies, they would go on strike and cripple us.’ (Headteacher, School 8a)

‘The previous MAT upset people… They precipitated the strikes. I don’t fully go along with this as the staff are very militant and have been in charge for years and years.’ (Teacher, School 8a)

Although headteachers in unstuck schools have been prepared to have difficult discussions when needed, those in stuck schools are anxious about the time and emotional energy needed to make changes at the school with the challenge the union voice would give.

The role of school improvement support and inspection

The government has introduced a number of different school improvement initiatives over the last 2 decades to help support underperforming schools, in addition to system-wide policies such as academisation. Some of these initiatives have been available to schools (though not always mandatorily) that are judged as requires improvement, as well as those that are inadequate. A summary is listed below. This list is not exhaustive and there are other forms of school improvement support (for example, in local authorities) that also exist.

Figure 3: Summary of school improvement initiatives

| Dates | Name | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 to 2003 | Education action zones | An area-based programme with several educationally underperforming towns and cities tasked with bringing together schools, parents and businesses to attract private sponsorship. |

| 1998 to 2005 | Beacon schools | A national status given to high-performing schools, requiring them to disseminate good practice to struggling schools. |

| 1999 to 2006 | Excellence in cities | A place-based funding programme for 58 underperforming local authorities to support learning mentors, learning support units, gifted and talented projects and city learning centres. |

| 2001 to 2006 | School facing challenging circumstances | A category for schools in which less than 25% of pupils achieved 5 GCSEs at grades A* to C, prompting additional government funding and more regular inspection. |

| 2003 to 2006 | Leadership Incentive Grant | A national fund for struggling schools, with the aim of enabling them to hire experienced teachers and leaders. |

| 2005 to present | School improvement partners (SIPs) | An individual from the local authority tasked with supporting struggling schools with their self-evaluation. |

| 2006 to present | National leaders of education (NLE) | A national network of experienced leaders funded to support other schools. This was expanded in 2010. |

| 2008 to present | Local leaders of education (LLE) | A local network of experienced leaders, funded to support struggling schools for a small number of days a year. |

| 2008 to 2011 | National challenge advisors | A national network of advisors, working closely with NLEs, to develop a school improvement plan for schools with fewer than 30% of pupils achieving 5 or more GCSEs above grade C. |

| 2010 to present | Specialist leaders of education (SLE) | A network of experienced middle leaders with a subject or specific area of expertise (such as behaviour). |

| 2011 to present | Teaching schools | A national network of good or outstanding schools that provide training for teachers and support to schools in their local area. |

| 2012 to present | National leaders of governance | A national network of experienced governors facing governance challenges for a small number of days a year. |

| 2016 to present | Opportunity areas | A place-based programme to improve social mobility in 12 local authority districts, bringing together local stakeholders with central government to create a plan for the area. |

| 2017 to present | Strategic School Improvement Fund (SSIF) | A national fund from which local authorities, MATs and teaching schools could bid to support eligible schools in their area. |

| 2017 to present | Teaching and Leadership Innovation Fund | Support for 10 providers of continuing professional development to offer a variety of programmes to existing teachers and leaders of schools who principally work in Ofsted-rated grade 3 or grade 4 schools which are within an opportunity area or one of category 5 and 6 LA districts. |

| 2018 to present | Tailored support programme | To provide NLE-led tailored packages of support to schools facing severe teacher recruitment and retention challenges. |

| 2018 to present | School improvement support | Bespoke support for underperforming schools, comprising of help from system leaders and evidence-based support programmes. In 2019 to 2020, eligibility is based on Ofsted judgements. |

Over the same period, there have also been changes to the way Ofsted inspects and reports on schools. The most relevant changes to these schools, as reported through the research visits, are the:

- introduction of non-graded monitoring visits of inadequate schools in 2001 (ceased as part of routine inspection in 2016 for maintained schools,[footnote 7] as these schools would be academised by the DfE through regional schools commissioners. We continue these for schools in which we have safeguarding concerns.)

- introduction of improvement seminars for inadequate schools in 2002 (ceased in 2009)

- introduction of monitoring visits for satisfactory schools in 2009 (continues for requires improvement schools)

- replacement of the term ‘satisfactory’ with ‘requires improvement’ in 2012, to denote a grade 3 provider (continues)

- introduction of ‘getting to good’ seminars for requires improvement schools in 2014 (ceased in 2015)

- introduction of the common inspection framework in 2015 (replaced in 2019 with the education inspection framework)

The literature on school improvement

This chapter presents an overview of the research on school improvement initiatives and evaluates how well this is being put into practice for stuck schools.

Much of the literature on school improvement warns against schools trying to implement too many strategies at once.[footnote 8] Research has instead concluded that focusing on a small number of core goals is more effective.[footnote 9] Indeed, this was a main finding of our 2010 evaluation of the national strategies, which found that:

‘the frequent introduction of new initiatives, materials and guidance led to overload and diminished the potential effectiveness of each individual initiative’.[footnote 10]

There is a significant body of literature on implementation science, particularly in health policy. The literature tends to find positive effects of using an active implementation framework,[footnote 11] which advocates introducing initiatives that are flexible enough to be implemented with high fidelity. The Education Endowment Foundation uses this literature in its ‘School’s guide to implementation’.[footnote 12]

Research has also suggested that context-specific initiatives are more effective for schools that are struggling the most.[footnote 13] This follows a wider body of literature that supports the idea of balancing the fidelity of implementation with flexibility.[footnote 14]

Timeline of school improvement initiatives

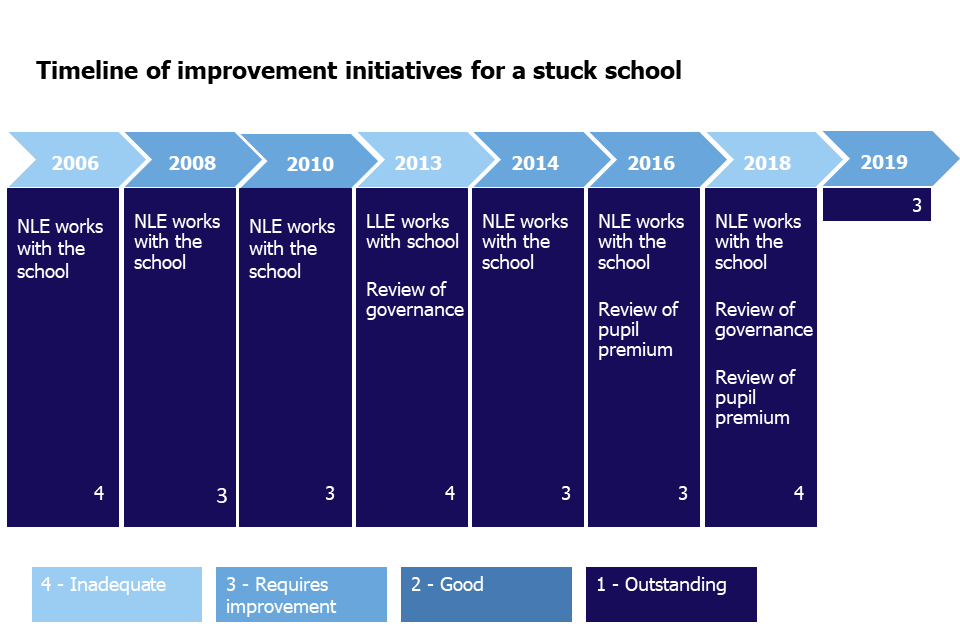

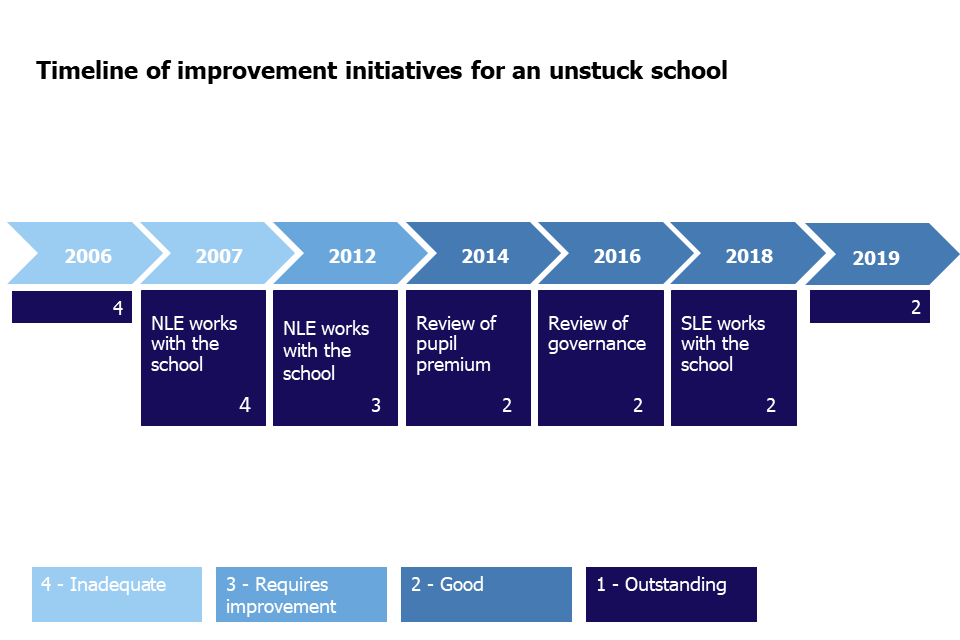

All the schools we visited had been involved in multiple forms of school improvement initiatives (usually around 5 to 6), receiving advice from several different organisations and individuals since 2005. Because we were not always able to speak to staff who were at the school since 2005, it is likely that the number of improvement initiatives they have received is underestimated. Most schools received advice from NLEs and could usually recall working with 2 or 3 different NLEs.

The visits highlighted the fact that just as many stuck schools had received support as unstuck schools: there was no apparent difference in levels of, or access to, support.

Figure 4: Timelines comparing school improvement initiatives for a stuck school and an unstuck school

The timeline shows movement between inadequate and requires improvement and improvement initiatives (NLEs, SLEs and reviews of governance and pupils premium) 2006 to 2019.

Note: The timeline shows the years that the school took part in improvement initiatives.

The timeline shows movement from inadequate to good and improvement initiatives (NLEs, SLEs and reviews of governance and pupils premium) 2006 to 2019.

Note: The timeline shows the years that the school took part in improvement initiatives.

We know, however, by the fact the stuck schools are still not graded good that these initiatives did not have a substantial enough impact. Evidence from visits also suggests that unstuck schools did not find them to be transformative either, as discussed in the next section.

Views on school improvement initiatives

This section summarises the views from stuck and unstuck schools on the effect of those initiatives. Although some of the schools we visited were unstuck, there was no evidence to suggest that any of the school improvement initiatives were important in this transformation. Our evidence is, however, based on schools’ perspectives rather than a full analysis of impact. Because some of the school leaders, staff and governors that we spoke to were those who had been running or working in stuck schools for some time, their ability to fully evaluate their school’s position may have been weak.

The findings contrast with schools’ views of internally driven factors for improvement, such as behaviour policy change, which were often cited as having a transformative effect. Although there can be a link between external support and internal policy changes, this link was not made explicit by the schools we visited.

Overall, schools told us that they received too much advice and that this advice was ‘thrown’ at them without enough thought. They found that the quality of those providing advice and support was too variable. When it was seen to work, the advice was tailored to the problems within the school and the individuals involved spent time working with staff. When it was seen to fail, there was too much general, one-size-fits-all advice, with individuals spending too little time and giving too little thought to the priorities of the school.

Leaders of education

Most schools that we visited had received support from one or several of the following:

-

national leaders of education (NLEs), who are experienced school leaders with a track record of at least 3 years working for a school that is graded good or better

-

local leaders of education (LLEs), who are no longer managed by the DfE, but can be designated by teaching schools to provide leadership support

-

specialist leaders of education (SLEs), who are experienced leaders with a specialism in a subject area, or specialist leadership area (such as behaviour)

All these types of ‘system leaders’ are made available to support struggling schools and schools would normally approach the teaching school to broker support in the period of interest.[footnote 15]

There were a range of views about leaders of education. Some school leadership teams had found their support helpful in the past, while others thought their work had added confusion and given misplaced attention to some areas of school improvement.

There were 2 circumstances in which leaders of education were perceived to work well:

- when designated leaders (for example, NLEs or SLEs) had been found from staff within the MAT rather than outside it

- when leaders took the time to understand the school and deliver bespoke support.

This is exemplified in 2 headteachers’ comments:

‘The MAT had commissioned support involving an NLE in the academy trust, coming to work with me doing mentoring learning walks and performance management support. Really really effective… Very much bespoke to us: what we needed and required.’ (Headteacher, School 9a)

‘We brought in SLEs from the MAT, who spent one or 2 days a week to up-skill teachers. This was external moderation… SLEs from outside the trust didn’t have the right skill set: we needed those who’d worked in challenging schools.’ (Headteacher, School 7a)

Leaders of education were considered less effective when they did not spend the time to get to know the challenges with the school:

‘[The] SLE was not effective – they did not team teach and support. They spent the time monitoring without the coaching, modelling and support. Most of the time the teachers were left to their own devices.’ (Deputy headteacher, School 1a)

‘Local leaders of education, we didn’t see them enough… It was a mismatch, it wasn’t appropriate to our children. When their teachers came to work with us, their jaws dropped. They didn’t have the skills they needed in our school.’ (Assistant headteacher, School 2a)

‘In some cases, because they didn’t take the time to get to know the school, the NLE didn’t always offer the right things to do’ (Headteacher, School 2a)

Other schools reflected their view that leaders of education (particularly LLEs) were more interested in elevating their personal position in the local network of schools than providing high-quality advice. Some described this as ‘a power thing’ with senior leaders from local schools.

Some of the leaders we spoke to were leaders of education themselves. They believed that there needed to be a better matching process between the leader (usually an NLE) and the context and challenges of the school.

Teaching schools

The success of the match between the stuck school and a teaching school was also considered important. As set out in [the appendix](#appendix], a teaching school is a good or outstanding school that provides training for teachers and support to schools in its local area. When teaching schools were reported as being successful in helping a school improve, this included close working between headteachers and mentorship.

For others, teaching schools have been frustrating and confusing, with some describing the experience as ‘demoralising’ for staff. This was particularly the case in resistant and embedded schools when there could be a conflict of vision between the leadership of the school and the teaching school that was left unaddressed:

‘In teaching school 1, I knew some heads who had worked with the school and said that the school had similar expectations. This was successful. However, teaching school 2 had a totally different outlook to me, and different to parents and children. They wanted our staff to work their way. This was frustrating for our teachers. It was confusing for teachers who asked, “do I follow you or the teaching school? You are saying different things”.’ (Headteacher, School 1a)

Staff in some schools (particularly classroom teachers) felt they had a lack of autonomy over which teaching schools would be appropriate for them. As school leadership teams are usually able to choose their teaching school partners, this may reflect a divergence of opinion on the school’s needs. Some teachers found that teaching schools did not have the resources required to facilitate improvement, such as the necessary subject-specialist teachers.

School improvement partners

There were mixed views about the effect and quality of school improvement partners. Some schools remembered historically quite large teams of senior leaders being sent to the school from the local authorities. This was viewed as supportive but in all cases the school remained stuck afterwards. Two leaders commented:

‘If I can think back, there was a team of SIPs in 2010. They’d come in, here and there, for a day, from the LA. It was saying the right things but then they’d go off for weeks and nothing really changes. It must’ve been a huge investment.’ (Senior leader, School 7a)

‘When I arrived the behaviour policy was phoning 999 to access the police. It was beyond chaotic. The SIP had no appreciation of the amount of work needed to turn around a highly challenging school. Her reports focused incorrectly on areas that were not of significance. I made a fuss – changed a SIP.’ (Headteacher, School 4a)

Schools were more positive about their recent encounters with SIPs. These individuals were either attached to their MATs or from an outstanding school in the local area. Advice is welcomed when it is more practical and when the relationship with the school is sustained:

‘Historically, we’ve had a couple of SIPs that we thought were okay but not great… But now we’ve got our SIP, who is a local outstanding headteacher, and has been outstanding for many years, and she’s able to come in, she does a very rigorous review, and she does a lot of peer coaching with [headteacher] and is very practical… Previously too much advice was given, it was too expensive and limited impact.’ (Governor, School 4a)

Opportunity areas

Only 2 of the schools we visited reported being part of an opportunity area and both schools were stuck. In the main, their involvement in the initiative was too recent for the schools to evaluate its effect. However, one school commented on the difficulty it had in accessing support with an unstable leadership:

‘The opportunity area has been difficult to access in the right way. The process has been tricky, so we’ve missed out on this. Without the continuity and consistency of our leadership, we’ve not been able to access this pot of money as we’ve had too many changes in staff. It’s a very specific process to achieve this.’ (Senior leader, School 8a)

This suggests, as with other initiatives, that stuck schools need high-quality support to prioritise and coordinate their improvement journey. The leadership of these schools either lacks those essential skills or is busy dealing with the day-to-day difficulties of running the school.

The quality of advice

As the evidence from our school visits demonstrates, there is no shortage of support and advice available to stuck schools. Many schools commented on the sheer volume of initiatives and advice available out there, with the feeling that these were ‘thrown at’ the school without enough consideration:

‘You’ve got to be careful not to have initiative overload. Ideas generation is my job but we’ve got to pick what to focus on.’ (Senior leader, School 8b)

‘Sometimes too many people coming in, telling us what to do, too much to deal with.’ (Headteacher, School 1a)

‘Before academisation, lots of things were thrown at us. LA advisors gave out lots of different messages, not all cohesive.’ (Headteacher, School 10b)

‘People throw things at you with the best intentions but it isn’t what we need right now… I have support from MAT. My confidence grew as a result of the initial support from the MAT and to make decisions.’ (Headteacher, School 9a)

This feedback suggests that there is enough capacity within the school system to support schools and that the focus should instead shift to improving the quality of advice available.

There were many examples of improvement support being perceived to work well in the schools we visited. As discussed above, the features of this working well are:

- support is commissioned from those that know the school well – in these instances, the MAT

- those delivering the support have the necessary experience to address the school’s unique challenges

- the support is bespoke to the school and time is spent with teachers and leaders

Views on Ofsted inspection

Ofsted’s role in the system is different to that of schools and the DfE. We independently inspect and report on the quality of education. It is for others to take action on the basis of what we have seen.

However, our aim to be a ‘force for improvement’ means we should always reflect on where inspection and subsequent action by others have not led to sufficient improvements in education quality. It is important that our inspections are as useful as they can be to all those responsible for improving schools.

Data on inspection numbers shows that 83%vof the stuck schools have been inspected 4 or 5 times and the remaining schools have been inspected 6 or 7 times (see Figure 5). Although stuck schools make up only 2% of all schools in England, it is clear that inspection has not been the required catalyst for sustained improvement in these schools’ cases.

Figure 5: Number of inspections since stuck schools’ first requires improvement or inadequate judgement

This chart shows the number of stuck schools by the number of full inspections since their first requires improvement or inadequate judgement. The largest group of stuck schools have had five full inspections.

We should never judge the effectiveness of inspection on subsequent improvements in inspection grades. To do so would create a perverse incentive for us to give higher judgements rather than to inspect independently. However, it is important for us to work with those responsible for improving schools to make sure our inspections are as useful as they can be.

Schools spoke to us about their experience of Ofsted. In general, unstuck schools were more positive than stuck schools – most likely because they had received 2 recent good judgements. Across all our research at Ofsted we find a positive correlation between a school’s latest inspection judgement and its views on the experience of inspection.

Impact of inspection

Overall, school leaders spoke of the benefits of independent inspection to their school’s journey. Some commented on the fresh thinking and impetus this had given them to make changes in their school. Others valued the expertise of HMI and the experience of our Ofsted Inspectors (OIs), who are serving practitioners in schools. Leaders said that they wished to commission advice from them more regularly:

‘It was very difficult, but the recommendations were precise and clear, and we acted on these… I definitely think the outcomes of the inspection were helpful and reshaped our thinking.’ (Senior leader, School 8a)

‘We have had a very positive experience of inspection throughout the trust… We felt that inspectors had taken the time to know the school and had an ability to hold us account. We are excited by the new inspection framework. We would like to commission the support from Ofsted – feel that expertise would be so useful for improvement.’ (CEO of trust, School 9b)

The impact of inspection also reached those responsible for designing and teaching the curriculum:

‘You came in at the right times… For me, the first 6 or 7 years of my career, there was one Ofsted visit a year or a monitoring visit… The school was in a category of concern and received monitoring visits. It felt that SLT were firefighting hugely. Now we feel ready for inspections. You could come in now at any time and it is the normal.’ (Teacher, School 5b)

‘Because of the last inspection all aspects of English changed. We linked this change to the areas for improvement in the report, including the link between topic and writing. Children are now saturated with the text. Children can now see the journey, it’s so much better.’ (Senior leader, School 1a)

Support following inspection

Despite a view that Ofsted’s recommendations and professional expertise helped schools, many governors and headteachers bemoaned the lack of support they received immediately following inspection. Usually, this was expressed in terms of Ofsted inspecting and then leaving, rather than working with the school following inspection to improve it. This is because the government does not ask or fund Ofsted to support schools following inspection. When schools were told this, they made reference to a more general lack of support immediately following inspection, in contrast to the amount of support made available to them in the longer term. The DfE aims to address this through its new School Improvement offer for requires improvement schools.[footnote 16]

Schools found themselves without support from those that had seen and understood the school and who knew how to advise them:

‘Ofsted come into the school for 2 days, identify areas to improve but do not provide support or funding to address these.’ (Teacher, School 5a)

‘We are one of the most vulnerable schools according to Ofsted, but we’ve had nothing and have been left for a year. That I find very difficult.’ (Headteacher, School 2a)

‘We were given the judgement without being given the support. The headteacher was unaware of where we could get the support needed to be good.’ (Teacher, School 6a)

This suggests that a closer link between Ofsted inspection and the support given to schools by others could be beneficial. This approach could be achieved without Ofsted directly delivering school improvement support and with it maintaining its statutory role to independently inspect and report on school quality.

Recognising ‘green shoots’

Schools also recognised that inspection teams have to make difficult judgements, particularly when there is a new leadership team at the point of inspection. In some cases, schools thought Ofsted took a risk in awarding a higher judgement to validate the approach of new leaders; in others, they thought we did not give the new leadership team enough of a chance. Others thought we were too generous and that this led to inaction and a deepening of the problems at the school.

One executive member of a MAT with a stuck school told us that receiving a judgement of good for leadership and management made things worse for the school and its pupils in the long run:

‘The first Ofsted report after it became an academy gave the school a false lift… The MAT thought they could ease off as the school got a 2 for leadership and management. This was the mistake. There were 2 monitoring visits, the signs should have been there, and this was reflected in these. At that stage it was right that the school went into a Grade 4. It was a huge shock. This kick started everyone into action. Who knows how long the school would have drifted.’ (Executive principal, School 7a)

There were varying views about whether recognising ‘green shoots’ in the potential of new leadership teams was helpful. Some teachers felt that Ofsted did not give new leadership teams enough of a chance, while some of those responsible for governance thought inspectors’ desire to recognise potential had harmed the school:

‘I do not believe that the school was inadequate when inspected. The headteacher was new in the school, she had clear ambition and knew what she needed to do. This was not helped by the inspection; it was destructive.’ (Teacher, School 5a)

‘Some inspectors were generous but that wasn’t helpful. I think the school had coasted and it should have been pulled up before this. Sometimes an RI [requires improvement] judgement feels kinder but doesn’t help.’ (Governor, School 2a)

Monitoring visits

It is not easy to assess whether Ofsted inspections and visits were right to be firm or right to recognise green shoots. In 2016, we carried out internal research and found that most schools that remained requires improvement or declined at their re-inspection had been judged to be ‘taking effective action’ at their previous monitoring visit. Very few monitoring visits had been complained about (less than 1% of visits). This may be indicative of effective inspecting and maintaining a strong professional dialogue, or indeed too little robust challenge.

Nevertheless, when we identified that leaders were ‘not taking effective action’, over half subsequently improved at their next inspection. This suggests that when visits are clear and direct in their view of the insufficiency of leaders’ actions, monitoring visits can motivate improvement and change.

We have since invested in training to ensure that monitoring visits are as effective at encouraging improvement as they can be.

School leadership decisions

This section summarises the evidence from visits on the leadership decisions that governors, teachers and leaders considered to be the most effective. Those researching struggling schools often point to effectiveness of leadership as being crucial, but there is little research on what leaders in stuck schools should do.

Upholding high teaching standards

All senior leaders commented on the importance of recruiting and retaining good teachers. However, there were different views about how to achieve this. Schools that were unstuck believed the following were crucial in the transformation of the school:

- achieving the right balance between teacher turnover and quality

- using the ‘teachers’ standards’[footnote 17]

- improving flexibility for staff

As discussed earlier, the context of stuck schools made recruitment and retention challenging. There were different views about the relative importance that the SLT gave to retention compared with upholding high standards of teaching.

In stuck schools, there was a tendency to see reducing turnover as important above all else, even if this meant keeping poor teachers at the school. In unstuck schools, a greater number of senior leaders saw high turnover or temporary understaffing as a price worth paying for upholding good teaching standards.

All unstuck schools highlighted the importance of managing performance well. This included challenging poor teachers and encouraging those with potential. During the school’s journey to becoming good, senior leaders of unstuck schools stated that they heavily relied on the ‘teachers’ standards’ to manage performance. In some cases, this led to the school removing poor teachers and raising motivation and expectations for good teachers. Once schools became good, they tended to move to more flexible methods. One school commented:

‘A big issue was the quality of teaching in 2016, without the staff realising. The mantra was “Ofsted got it wrong”. I was staggered by how unaware they were. When the teacher standards came out, staff started to become aware of what good teaching looks like – this had a dramatic impact.’ (Headteacher, School 7a)

When it came to improving the quality of teaching through recruitment, senior leaders spoke of the need to change the culture within the school. Two different schools commented:

‘There was poor quality staff previously. We’ve managed to retain quite a lot of the good staff and we’ve managed to shed the not so good staff… And the appeal of working in [city], if we’re talking back to recruitment I think that’s a back factor. Getting good quality graduates to come and work in this town, and I think the lack of aspiration in the town is an important factor.’ (Senior leader, School 3b)

‘We brought in staff who knew what they were doing. There was significant negativity; staff were very resistant to change on the back of lots of new people coming in… Successful recruitment has been around telling people about the moral purpose. People have left us when they don’t fit with our ethos. We don’t recruit from the merry go round of teachers here in the local area.’ (Headteacher, School 7a)

The headteachers of at least 2 stuck schools were challenged by strong union representation resisting action to improve the culture of the school. These headteachers saw previous leaders as weak for not being able to handle these challenges. Often, however, these leaders lacked the support of strong governors who knew about the issues and were prepared to back them.

In one stuck school, the headteacher had been in post for 12 months and commented:

‘The 2 problems have been the finance and the unions… I prepared for dismissals of staff. It would have been a tough move but I was prepared to do that… Then I worked on a staffing restructuring and saved £650,000. The unions were objecting to the basics of monitoring and leadership and it made leadership untenable. We’ve had some really good recruitment for next year including school improvement.’ (Headteacher, School 8a)

Similarly, a senior leader told us:

‘Previously we had a great deal of unionisation. Staff are now more open however in the past there was a real hill to climb in order to develop the school… Previously governors were not skilled to take on the challenge. I just think everything in the school has been ‘ramped up’; everything is more professional now.’ (Senior leader, School 7b)

A number of unstuck schools considered innovative methods for retaining talented staff. This included implementing the following strategies:

- introducing an email curfew for teaching staff

- permitting job shares

- re-employing retired teachers

The success of these initiatives depends on the context of the school and its workforce. However, staff, senior leaders and governors in these schools believed that they helped them to retain good teachers and leaders in an otherwise difficult labour market.

Getting behaviour right

When asked what changes had led to improving education, nearly all unstuck schools made reference to behaviour policy. This included both setting the right policy and implementing it consistently across the school. Only 2 of the 10 unstuck schools did not mention behaviour policy at all.

Some stuck schools also mentioned changes that they had made to behaviour policy and its implementation, stating that they thought these had improved their ability to teach and the quality of education in the school. However, fewer stuck than unstuck schools mentioned this, and in all cases their new behaviour policy had been implemented after their most recent full inspection.

There are several aspects to the changes that unstuck schools had made on behaviour policy:

- establishing sufficiently high expectations

- implementing the policy consistently

- understanding the effect on the retention of good teachers.

Many school leaders and teachers recognised that having sufficiently high expectations of the whole-school community – including pupils, parents and other teachers – was fundamental to their transformation. Sometimes, this meant changing the culture for pupils and families from one that accepted disruption and violence, to one that challenged it with clear processes. Leaders told us:

‘The behaviour policy changed the culture… We raised the expectations. There were low expectations of our pupils even from staff. We needed to say “this is the standard”. Now the behaviour policy is strict but clear. Pupils and teachers know that there is a consistent approach. Teachers and pupils now want to come to the school. Basically, when I came there were no processes.’ (Headteacher, School 5a)

‘When I first came to this school the behaviour was really poor – it was crowd control. I really would not turn my back on any pupils or give them scissors. Not enough time therefore to teach… Now we have developed a culture when student ethos is positive’ (Senior leader, School 5a)

As these comments show, ensuring consistency is a crucial part of implementing good behaviour policy. This includes taking decision-making away from teachers, so that they have the reassurance that leaders will support them in following the school’s behaviour policy. One senior leader at a stuck school commented:

‘Behaviour was “tricky” when I joined. There was a lot of time when I was in my teaching role but I couldn’t teach because I was constantly sorting out behaviour issues… We now have that more or less under control – we’ve got really good systems now. But that’s taken a long time to embed.’ (Senior leader, School 10a)

It is clear that the leadership’s ownership of the behaviour policy has a large impact on the retention of high-quality teachers. This is clear from focus groups with teachers, who worked in schools where behaviour clearly had been an issue in the past:

‘Strategies for behaviour since joining the MAT has made the biggest change, along with professional development… Prior to academisation we were desperate to train in behaviour interventions. It was frustrating not to be given these opportunities, but good now that we are able to.’ (Teacher, School 10b)

‘Having a strong behaviour lead has been invaluable – you can focus on teaching and not managing behaviour extremes.’ (Teacher, School 6a)

Some senior leaders in stuck schools have recognised the impact of poor behaviour on teacher retention:

‘Retention issues have been a mixture of teachers which have not “fitted” the school and others who have left – reasons for leaving include leadership responsibility pressures against the stresses of managing behaviour.’ (Senior leader, 10a)

The link between managing behaviour and teacher retention was more obvious to headteachers in unstuck than stuck schools. In stuck schools, it was rarely mentioned in the context of retaining high-quality staff, even though leaders saw this as a core issue to address. Our previous research into teacher well-being shows that there is a clear link between managing challenging behaviour and the retention and well-being of staff.[footnote 18]

The impact of effective MATs

Most unstuck schools that were part of a MAT considered the influence of the MAT as crucial to their recent success. Teachers and leaders at all levels within these schools recognised the importance of the MAT. They usually made reference to the MAT’s role in raising expectations and developing curriculum subject expertise.

These schools considered the scale and management of the trust to be critical in developing subject expertise. This includes creating opportunities for sharing knowledge and expertise, and using the scale of the trust to fill vacancies or establish subject career development:

‘Academy-led subject networks have been significant – they have been a huge investment in CPD. We are given a lot of opportunities to develop our practice. We have built leadership capacity. There have been a lot of secondments to enrich people’s awareness of roles.’ (Teacher, School 7b)

‘Teachers are now collaborating; subject leaders work together. If one leaves, you retain some subject specialists. Previously, where staff left, you were left with inadequate teachers. Scale through the trust gives solutions and protection against these problems.’ (Governor, School 5b)

Teachers and leaders in these schools also recognised the importance of the MAT in setting high expectations and providing challenge where needed:

‘I think it’s quite telling that my first port of call is always the MAT. This is where most impact support and intervention has come from. Without this we wouldn’t have made the sustained improvement that we have.’ (Headteacher, School 5b)

‘The trust expectations have ramped up expectations: they are looking for commonality across the academy schools. This has changed rapidly. As the trust has grown, the structures have improved. Previously they were too laissez-faire.’ (Teacher, School 7b)

However, it was clear from the visits that being part of just any MAT does not make the difference. A number of stuck schools were part of their current MATs at their latest inspection and had been for at least 3 years (in one case, 7 years), but still had not been graded good. Only 2 schools (one stuck and one unstuck) had been transferred to another MAT once since 2005.

The stuck schools that were paired with the above unstuck schools (5a and 7a) saw the failure of the MAT to provide effective challenge and insight as a make-or-break moment for the improvement of their school. One headteacher thought the MAT invested too much at the senior level, rather than at other levels, within the school:

‘Working with MAT wasn’t as impactful as I would have liked… They sent into the school someone to work in the school for 2 days per week… I felt we were just hiring a less than capable senior leader – an extra body yes but not an expert.’ (Headteacher, School 5a)

Improving the parlous state of oversight

The lack of thorough scrutiny and oversight of school leadership was an issue for most schools we visited. The only schools that thought they were effectively held to account were unstuck schools in MATs. In these instances, it was the executive team, rather than the local governing body, that was fulfilling this important duty. These executive teams tended to be part of a national structure.

The rest of the schools we visited commented on the lack of scrutiny, support and challenge given by those with responsibility for governance. This was often put down to a lack of skills in school leadership and management.

The headteacher was seen as the accountable officer in these instances, holding to account those responsible for governance, rather than the other way around. One teacher in an unstuck school commented on the ‘abdication’ of responsibility by governors and the good work of the headteacher to control this:

‘We’ve not had good governors in the past: they had no concept of what it was like. The head had to get rid of governors who were misogynists. They were enraged that she stopped the residential where everyone got drunk. She wasn’t popular, but it was worth it.’ (Teacher, School 8b)

Sometimes, governors recognised how they could be easily led by senior leaders. The proliferation of internal performance data has not helped this situation, in which governors find themselves ‘bamboozled’ by senior leaders. This problem is particularly significant when the leadership is weak:

‘We are in the hands of senior leaders… We were bombarded by data by leaders and, with hindsight, could not see the wood for the trees… I do not think that we had a true understanding of the issues for this school of the effectiveness of the trust to manage this.’ (Vice chair of trust, School 6a)

It is likely that the same issues affecting the recruitment of good teachers and leaders also affects the recruitment of good governors in these areas. This issue is avoided in some of the larger, less localised MATs, because a national or regional executive team provides governance and oversight. However, the data on stuck schools shows that around half of stuck academies are part of a small or medium MAT (with under 10 schools) compared with 25% of all academies. The opportunities to improve governance by recruiting executive members from a broader geographical area are therefore not being maximised.

Conclusions

This research should give hope to anyone attending or working in a stuck school. It is possible to improve, even in the most challenging of circumstances. There are unstuck schools working in similar environments that are making it happen. The leaders of these schools focus on:

- implementing an effective behaviour policy

- ensuring high standards of teaching, sometimes at a cost to retention levels

- getting the right support from their MAT

However, the findings suggest that the separate systems of inspection and support are not working together as effectively as they could. Improvement support is rarely seen as transformative. Schools feel they receive too much advice from too many different directions and, although this may have helped some schools, the quality of those delivering it is too often questioned. There is certainly no lack of capacity for school improvement, but rather a need to improve its quality.

We recognise the part that Ofsted has to play. As an independent inspectorate, our job is to inspect and provide a thorough view of the quality of education being delivered, but one that is sufficiently detailed so that these schools can respond effectively. We work within a policy framework in which others support and improve schools.

However, stuck schools are complex. Their pupils face incredibly challenging social circumstances. It takes time and expertise to fully diagnose the issues within these schools. We are therefore working with the DfE to jointly review our approach to independent inspection and the support provided by others in these schools, so that the system as a whole can improve education for all children.

Appendix

Basic characteristics of schools visited

The below table provides some basic statistics on the stuck schools we visited and their unstuck pairs. The schools came from all of Ofsted’s 8 regions.

We have not included detailed contextual information to prevent the schools being identified. We committed to take all reasonable steps to prevent the schools or individuals spoken to as part of this research being identified.

| Pair | Stuck or unstuck | Phase of education | Academy or maintained or other[footnote 6] | Urban or rural | School size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | Stuck | Primary | Maintained | Urban | Medium |

| 1B | Unstuck | Primary | Maintained | Urban | Medium |

| 2A | Stuck | Primary | Maintained | Urban | Small |

| 2B | Unstuck | Primary | Maintained | Urban | Small |

| 3A | Stuck | Secondary | Other | Urban | Medium |

| 3B | Unstuck | Secondary | Academy | Urban | Large |

| 4A | Stuck | Secondary | Academy | Urban | Medium |

| 4B | Unstuck | Secondary | Academy | Urban | Medium |

| 5A | Stuck | Secondary | Academy | Urban | Medium |

| 5B | Unstuck | Secondary | Academy | Urban | Medium |

| 6A | Stuck | Junior | Academy | Urban | Small |

| 6B | Unstuck | Primary | Maintained | Urban | Medium |

| 7A | Stuck | Middle | Academy | Urban | Large |

| 7B | Unstuck | Secondary | Academy | Urban | Large |

| 8A | Stuck | Secondary | Academy | Urban | Medium |

| 8B | Unstuck | Secondary | Other | Urban | Large |

| 9A | Stuck | Junior | Academy | Rural | Small |

| 9B | Unstuck | Primary | Academy | Rural | Small |

| 10A | Stuck | Primary | Academy | Rural | Small |

| 10B | Unstuck | Primary | Academy | Rural | Small |

Note: ‘Other’ includes voluntary aided and foundation schools.

-

The Annual Report of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Education, Children’s Services and Skills 2017/18, Ofsted, 2018 ↩

-

This included the percentage of pupils who are eligible for free school meals, who speak English as an additional language and who are in a minority ethnic group, the IDACI quintile of the school, the size and phase of the school, and whether the school was in a rural or urban area. ↩

-