Fan-Led Review of Football Governance: securing the game’s future

Published 24 November 2021

Applies to England

Foreword

Like millions of other children my first experience of football was playing it in the street outside my childhood home. I would play for hours with the boys on the estate only pausing for the cars to pass or being called in for tea. My love developed from kicking a ball to watching it on TV, going to Reachfields to cheer on Hythe Town, to collecting Panini stickers, coaching girls and finally getting a season ticket at Spurs.

Despite being banned from playing football at school, simply for being a girl, the passion for the sport has stayed with me throughout my life. Four decades ago while kicking a ball against a wall with ‘NO BALL GAMES’ pinned to it I would never have dreamt that English football would have been bouncing from one crisis to another and that I’d be charged with helping the nation’s favourite pastime navigate its way beyond and on to a brighter future. It has been an absolute privilege to chair the Fan-Led Review of Football Governance working alongside an exceptional panel and a brilliant team of officials. Since the Review began, triggered by the European Super League (ESL) debacle, the Review team heard over one hundred hours of evidence from passionate fans, club leaders, interest groups, football authorities, financial experts and many others who engage day in and day out with football.

The commitment and passion of the fans who have contributed to the Review has been genuinely humbling to see. Where this passion had been betrayed by owners it has been heart-breaking — and testimony from those who had lost their club in Bury particularly so. The sophistication of thought about the problems of the game and solutions presented by those fans was also remarkable. It is often said that football would be nothing without the fans. The same can be said for this Review and I want to thank each and every one who has contributed.

The Review has formed the firm belief that our national game is at a crossroads with the proposed ESL just one of many, albeit the most recent and clearest, illustrations of the many deep-seated problems in the game. I believe there is a stark choice facing football in this country. Build on its many strengths, modernise its governance, make it fairer and stronger still at every level, or do nothing and suffer the inevitable consequences of inaction in towns and cities across the country — more owners gambling the future of football clubs unchecked, more fan groups forced to mobilise and fight to preserve the very existence of the club they love and inevitably more clubs failing with all the pain on communities that brings. As was remarked to the Review, clubs are only one bad owner away from disaster.

For those who say that English football is world leading at club level and there is no need to change I would argue that it is possible simultaneously to celebrate the current global success of the Premier League at the same time as having deep concerns about the fragility of the wider foundations of the game. It is both true that our game is genuinely world leading and that there is a real risk of widespread failures and a potential collapse of the pyramid as we know it. We ignore the warning signs at our peril and I hope this Review protects the good and the special but sets a clear course for a stronger national game with the interests of fans at its heart.

The Review concluded that English football’s fragility is the result of three main factors — misaligned incentives to ‘chase success’, club corporate structures that lack governance, diversity or sufficient account of supporters failing to scrutinise decision making, and the inability of the existing regulatory structure to address the new and complex structural challenges created by the scale of modern professional men’s football. Football is sport but it is also big business. As the game has grown and developed its governance has failed to grow and modernise with it.

The Report sets out the conclusions of the Review as to how to address these structural challenges but it is important to stress that the recommendations should be considered holistically and not as a set of individual options from which football can cherry pick. Stronger regulation, better corporate governance, and enshrined protection on heritage issues all lead to greater confidence in the redistribution of finances. Only if taken together can we ensure the long-term sustainability of football.

The main recommendation is for a new Independent Regulator for English Football (IREF) established by an Act of Parliament, which will be focused upon specialist business regulation adapted to the football industry. This would operate a licencing system for professional men’s football. The licencing conditions should focus upon measures to ensure financial sustainability via financial regulation (which should be a new system based upon prudential regulation in other industries) and improving decision making at clubs through items such as a new corporate governance code for professional football clubs, improved diversity and better supporter engagement. The licencing system would also allow IREF to protect key items of club heritage via a ‘Golden Share’ requiring supporter consent to certain actions by a club. Football clubs are important cultural assets and must never be the playthings of owners who are simply their custodians.

The Report also contains important recommendations on parachute payments, alternative revenue sources for other parts of the pyramid and grassroots football (including a new solidarity transfer levy), women’s football and player welfare. All of which I hope will be adopted by football and the government.

I do not apologise for the length of my Report into the Review. The issues are complex legislatively and financially. I hope that when read as a whole it is recognised that a great deal of thought, time and energy has gone into the contributions which have been made to the Review by fans and others across the game, and in consideration of the recommendations.

The final conclusions reached in the report are mine, but in reaching these conclusions I was assisted by a remarkable Panel of Experts whose commitment to the Review was incredible. Their wisdom and counsel was invaluable and I express my sincere thanks to Dawn Airey, Denise Barrett-Baxendale, Clarke Carlisle, Danny Finkelstein, Roy Hodgson, Dan Jones, David Mahoney, Kevin Miles, Godric Smith, and James Tedford for giving up their time for free. I would also like to acknowledge the assistance of and thank several additional experts who also voluntarily gave their time and assistance to the work of the Review, and in particular Kieran Maguire, Nick Hulme, Anthony Pygram, Tony Burnett, Ashley Brown, Lynsey Tweddle, Anna Donegan, Alexander Juschus, Reuben Wales, Craig Gleeson and Mark Phillips. I am also very grateful for the input of officials at the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities, the Home Office and HM Revenue and Customs. Finally, I would like to sincerely thank the dedicated team of officials who worked on the Review throughout — Chris Anderson, Adam Crockett, Laura Denison, Joanna Braine, Fiona Wood, and Tom Mills.

My happiest football memories include the times I pretended to be Clive Allen weaving around flowerpots to score imaginary cup final goals against the backdoor. The darkest days have been watching clubs like Bury and Macclesfield disappear from our communities. Past and present Sports Ministers have often said “football is in the last chance saloon” when it comes to reform. The saloon should be closed. Now is the time for an independent regulator to take on the reform that fans have been crying out for but which the authorities have failed to deliver, and it needs to be done now.

Tracey Crouch MP

Chair of the Independent Fan-Led Review of Football Governance

Executive summary

Football clubs should be classed as heritage. They are integral to many families and to cities and towns in a way that’s not replicated in other businesses. Clubs need to be protected from asset stripping and situations such as Bury…

Contributor to Fan-Led Review online survey

Background to the Review

The Fan-Led Review of Football Governance (‘the Review’) was the result of three points of crisis in our national game. The first — mentioned by the contributor above — was the collapse of Bury FC. A club founded in 1885, which had existed through countless economic cycles, several wars and 26 different Prime Ministers ceased to exist in 2018-19 with a devastating impact on the local economy and leaving behind a devastated fan base and community. This led to the commitment in the 2019 Conservative Party manifesto to ‘set up a fan-led review of football governance…’.

The next crisis was COVID-19. For the first time since the Second World War, club football was brought to a complete halt, threatening the continued existence of many professional football clubs. Fortunately, the clubs survived due to a combination of government support and commitment from many football stakeholders, including fans, club owners, and — eventually and after a delay of 6 months — the leagues and Football Association (FA). However, the pandemic and its effects laid bare the fragile nature of the finances of many clubs, as well as the structural challenges of the existing domestic football authorities.

The final crisis was the attempt to set up a European Super League (ESL) in April 2021. This new competition would have involved six English clubs as founding members, protected from relegation. It was a threat to the entire English football pyramid and led to an unprecedented outpouring of protests from fans, commentators, clubs and government. As a result, the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) announced to Parliament on 19 April 2021:

“…it’s clearer than ever that we need a proper examination of the long-term future of football. To many fans in this country, the game is now almost unrecognisable from a few decades ago. Season after season, year after year, football fans demonstrate unwavering loyalty and passion by sticking by their clubs. But their loyalty is being abused by a small number of individuals who wield an incredible amount of power and influence.

If the past year has taught us anything, it’s that football is nothing without its fans. These owners should remember that they are only temporary custodians of their clubs, and they forget fans at their peril.

That’s why over the past few months I have been meeting with fans and representative organisations to develop our proposals for a fan-led review. I had always been clear that I didn’t want to launch this until football had returned to normal following the pandemic.

Sadly, these clubs have made it clear that I have no choice. They have decided to put money before fans. So today I have been left with no choice but to formally trigger the launch of our fan-led review of football.”

The terms of reference for Fan-Led Review of Football Governance were issued on 22 April 2021. These charged the Review with the aim to ‘explore ways of improving the governance, ownership and financial sustainability of clubs in English football, building on the strengths of the football pyramid.’ The full terms of reference are included at Annex B.

Review

The Review Panel met for the first time in late May 2021. After this, evidence was heard from a wide range of football stakeholders, including representatives of supporters of over 130 football clubs, the Football Supporters’ Association (FSA), Kick it Out, the Football Association (FA), the Premier League, English Football League (EFL), National League, League Managers’ Association and Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA). The Panel also heard from football club owners, including the so-called “Big Six” and others throughout the pyramid. A number of evidence sessions were also held with experts in finance and other relevant areas as well as interest groups including Our Beautiful Game, FA Equality Now, and Fair Game. In all, over 100 hours of evidence was heard by the Review Panel or Chair, and a list of those who contributed evidence is at Annex C.

In July 2021, the Review also conducted an online survey seeking views on the issues being considered. This received over 20,000 responses and the results are summarised at Annex D.

Following this initial phase, the preliminary findings of the Review were published on 22 July 2021. Since the publication of these preliminary findings the Review has continued to investigate the issues and is grateful for the contribution of the many experts who were willing to assist its work, including the supervision team at the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and others.

The Review was primarily set up to address the challenges encountered in men’s professional football and the evidence that it received was overwhelmingly focused on these challenges. Unless otherwise stated, the findings of this Review and the recommendations set out in the report relate to men’s professional football. However, the passion of those involved and their commitment to the development of women’s football was incredible and the unique issues of women’s football are specifically addressed in a dedicated Chapter 10.

The findings of the Review

This report sets out the conclusions reached by the Review and its recommendations to ensure the future of English club football.

There is much to celebrate about English football. The Premier League is the leading football league in the world and one of the biggest leagues of any sport. The Championship is by far the biggest ‘second division’ in football. The strength and depth of the English football pyramid is admired across the globe, and the development of women’s football in recent years has been remarkable. The work of clubs in their communities has always been incredible and a source of real assistance to many in need but was demonstrated more than ever during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given all of the above, it is even more important that the future of football clubs is ensured by addressing the challenges faced by the game.

Chapter 1 Explores the structural challenges facing English club football that result in the need for reform. The key findings of Chapter 1 are:

-

The incentives in the game are leading to many clubs with fragile finances which were further exposed by COVID-19.

-

Many clubs are poorly run, with reckless decision making chasing an illusion of success and a disconnect between the interests of fans and owners.

-

Regulation and oversight of the game at the domestic level is not up to the challenge of solving the structural challenges and specialist business regulation that will be needed.

Chapter 2 Considers options for addressing the structural challenges identified in chapter 1. To ensure that a long-term and healthy future is possible the Review has concluded that sophisticated business regulation tailored to the specifics of the football industry is needed. This is very different to traditional sports regulation. The Review considered several regulatory models and concluded that this regulation needs to be led by an independent regulator, created by an Act of Parliament. This regulator should be independent from football clubs and government, and have a clear statutory objective with strong investigatory and enforcement powers. The new Independent Regulator for English Football (IREF) will not operate in areas of traditional sports regulation which will be left to the existing authorities.

The Review also concluded that the new regime should be delivered through a new licensing system, administered by IREF which would apply to the professional game (i.e. the top division of the National League and above). This creates a mechanism for the Regulator to enforce its requirements on clubs. It also allows IREF flexibility to introduce requirements tailored to address the problems identified in the industry, adjusted for different sized clubs, as well as to adapt these over time as the landscape changes.

Chapters 3 - 8 Sets out the Review’s recommendations for licence conditions to be introduced by the Regulator to address the problems identified by evidence received.

Chapter 3 Sets out a new approach to the financial sustainability of clubs based on regulatory models operated by regulators in other industries such as the Financial Conduct Authority. The Review considered that in the context of football, any financial regulation needs to consider five important factors:

-

Ensuring long-term financial stability — clearly the single most important factor in the context of the challenges facing English football,

-

Avoiding monopolisation of leagues,

-

International competitiveness,

-

Minimising burdens on clubs or an expensive system and

-

Ensuring compatibility with other rules (for example UEFA).

The Review looked at models of financial regulation operated in many sports around the world, including the existing approaches to financial regulation adopted by the Premier League and EFL. It concluded that none of these approaches balanced the factors outlined sufficiently to be an effective long-term solution.

The Review therefore concluded that a new system was required. The proposed system is simple and based on capital and liquidity requirements used alongside the financial resilience supervision model operated by the FCA (similar rules are used by the Prudential Regulation Authority and are currently being considered in the energy supply industry in light of recent company failings in the market). At its core, this is a relatively simple system and would be adapted to the nuances of the football industry. Clubs would work with IREF to ensure they have adequate finances and processes in place to keep operating. Firstly, clubs would be obliged to ensure they have enough cash coming into the business, control of costs and suitable processes and systems to ensure the sustainability of the business. Clubs would need buffers in place for shocks and unforeseen circumstances. IREF would look at clubs’ plans, conduct its own analysis and if a club plan is not credible, does not have enough liquidity, costs are too high or risk not accounted for properly, IREF would be able to demand an improvement in finances (e.g. inject some cash into the business or lower the wage bill).

Under the proposed new approach, a club would be able to invest in order to seek to improve its competitive position but this will no longer be to gamble with a club’s future. For a club to do this, the money would need to be in the club upfront and committed. Further, the Review has concluded that, on balance due to the fragile state of club finances, if the activity of one or a few profligate clubs driven by owner subsidies are objectively assessed as being destabilising to the long-term sustainability of the wider league in which it competes, IREF should be able to block further owner injections on financial stability and proportionality grounds.

The Review has also concluded that the new financial system should involve real time financial monitoring, with an ability to intervene at an early stage if required. As a last resort, clubs would also be required to have a transition plan — an agreed series of actions to undertake triggered by certain financial markers to ensure stability of a club whilst a new owner is sought. This will mean that IREF would intervene well before financial collapse, which is not necessarily true of other possible approaches.

The system of financial regulation outlined above would be a significant change for the industry. In order to smooth the transition to the new system and allow it to operate as soon as possible after the relevant legislation is passed, it is recommended that the Regulator be set up in ‘shadow form’. This would involve the Regulator being set up and the recruitment of experienced regulators, particularly on prudential regulation, who would work with the industry before the related legislation receives Royal Assent.

Chapter 4 considers who should be allowed to be the owner or directors of a football club. These are the parties whose actions can lead to the success and growth of a club or to disaster. An owner should be a suitable custodian of a community asset. A director should have the necessary skills and experience to run a football club.

Having considered the existing tests operated by the Premier League, EFL and FA, the Review has concluded that IREF should replace these tests with a single test for owners, and a different test for directors. In both tests, the applicant should be disqualified if they are subject to one or more disqualifying conditions, which shall initially be the same as those provided for in Section F of the Premier League handbook. Further, each test should contain an element of ongoing monitoring and, in the case of owners re-testing on three yearly intervals.

Owners’ Test The Owners’ Test should apply to any party (or parties acting in concert) who hold voting rights of 25% or more of the club’s share capital as well as to the ultimate beneficial owner(s). In addition to not being subject to any disqualification criteria, prospective new owners should also be required to:

- submit a business plan for assessment by IREF

- evidence of sufficient financial resources to cover three years

- be subject to enhanced due diligence checks on source of funds to be developed in accordance with the Home Office and National Crime Agency (NCA)

- pass an integrity test.

Directors’ Test The Directors’ Test should apply to all directors, shadow directors and senior club executives (as well as any ‘advisers’ or ‘consultants’ who perform a similar function). In addition to not being subject to the disqualification criteria, a prospective director should be required to:

- demonstrate that they have the necessary professional qualifications, and/or transferable skills, and/or relevant experience to run the club.

- pass an integrity test in the same manner as prospective owners.

- declare any conflicts of interest.

- declare any personal, professional or business links with the owner of the club in question, or any other club owner (past or present).

In both cases, the integrity tests would subject applicants to more scrutiny than has been applied to football in the past, but which is known in other industries. The Review has concluded that an approach based on that used in financial services, including the ‘Joint Guidelines on the prudential assessment of acquisitions and increases of qualifying holdings in the financial sector’ should be adopted. This would involve an assessment by IREF of whether the proposed owner or director is of good character such that they should be allowed to be the custodian of an important community asset. The proposed approach should be (but not limited to):

- a proposed owner be considered as of good character if there is no reliable evidence to consider otherwise and IREF has no reasonable grounds to doubt their good repute

-

IREF would consider all relevant information in relation to the character of the proposed owner, such as:

- criminal matters not sufficient to be disqualifying conditions

- civil, administrative or professional sanctions against the proposed acquirer.

- any other relevant information from credible and reliable sources

- the propriety of the proposed acquirer in past business dealings (including honesty in dealing with regulatory authorities, matters such as refusal of licences, reasons for dismissal from employment or fiduciary positions etc)

- frequent ‘minor’ matters which cumulatively suggest that the proposed owner is not of good repute

- consideration of the integrity and reputation of any close family member or business associate of the proposed owner

Chapter 5 Considers corporate governance, noting that good corporate governance can help better decision making by subjecting the actions of a club to proper scrutiny and challenge, as well as skills based recruitment, and diversity of skills and experience. The chapter recommends that there should be a new, compulsory corporate governance code for football. This should be based on the UK Sport and Sport England Code for Sports Governance, including proportional requirements with greater demands on clubs in the PL as compared to National League clubs. This will include mandatory requirements for items such as independent non-executive directors, skills based recruitment of directors and an express recognition of the stewardship duty owed to a community asset such as a football club (i.e. that an owner/director should be required to operate to ensure the club should exist long after they have departed).

Chapter 6 Addresses equality, diversity and inclusion. Aside from a clear moral case, improving diversity is also a key aspect of driving better business decisions by football clubs. Diverse companies perform better with detailed long-term studies by McKinsey & Co reporting that ‘the business case [for diversity] remains robust but also that the relationship between diversity on executive teams and the likelihood of financial outperformance has strengthened over time’.

In order to achieve this improved performance from diversity, the Review considers that each club should be required to have an Equality, Diversity & Inclusion (EDI) Action Plan, which would be assessed as part of the annual club licensing process. These plans would set out the club’s objectives for EDI, and importantly, how the club is going to achieve them for the upcoming season. IREF would then scrutinise these documents for approval at the start of the season, ensuring they are robust and challenging. As part of the annual licensing process, IREF would also consider the performance of the club against its previous plan. If IREF deemed there to be insufficient progress made against the organisation’s plans, it would be able to enforce financial or regulatory punishments.

The Review also concluded that the football authorities should work more closely to ensure consistent campaigns and where possible, pooling resources to increase the impact of these important initiatives. There should also be a new, single depository for reporting and collecting reports on discriminatory incidents.

Chapter 7 Considers ways to improve supporter engagement in the running of their clubs. As well as the importance of supporters having a voice in a significant cultural part of their lives, it makes business sense for clubs to liaise closely with their most important stakeholder and develop plans with their views at the forefront.

The Review investigated a variety of approaches for supporter engagement. The Review concluded that IREF’s role is to set a minimum baseline of engagement across all licenced clubs. It therefore could not set multiple requirements as these would not be deliverable across all licenced clubs, though clubs should consider multiple engagement strategies, including town hall style fan forums, structured dialogue, fan elected directors, Shadow Boards and supporter shareholders.

Chapter 7 sets out the Review’s conclusion that each club be required to have a ‘Shadow Board’ of elected supporter representatives which would be consulted by the club on all material off pitch matters. The mechanism for selecting the Shadow Board members should be independent of the club, and result in members from a cross section of the supporter base. In order to allow full discussion, the members of the Shadow Board should be subject to suitable confidentiality obligations though these obligations should allow members of the Shadow Board to discuss most matters, although not confidential items including financial matters, with the wider fan base.

Chapter 8 Provides for measures to protect club heritage. The loss of club heritage, most frequently stadiums, is often a consequence of badly run clubs. The Review also considered that in recognition of the cultural, civic and community role of clubs there should be additional protection for key items of club heritage, including preventing the club from joining new competitions not affiliated to FIFA, UEFA or the FA.

The Review has therefore concluded that each club should be required to provide for a special share — a ‘Golden Share’ — in its articles of association. This share should be held by a democratically run Community Benefit Society formed under the Cooperative and Community Benefit Societies Act 2014 for the benefit of the club’s supporters. In most cases, this can be an existing Supporters’ Trust, provided that the constitution of such a Trust meets specified requirements. The Golden Share would require the consent of the shareholder to certain actions by the club — specifically selling the club stadium or permanently relocating it outside of its local area, joining a new competition not affiliated to FIFA, UEFA or the FA, or changing the club badge, the club name or first team home colours.

The Review is confident that this model can work and heard from several clubs that they would be comfortable with the proposal as well as from others who are already working on similar models with their own fan base. The Review notes the successful operation of this model by Brentford.

The Review also noted that the Golden Share approach has limitations, and accordingly it has also considered other ways that might provide protection for items such as club stadiums. This included investigation of items such as planning law, and the Review has concluded that the government should explore ways to clarify some aspects of planning law to provide additional protections.

Chapter 9 Considers financial distributions and specific reforms that might assist the revenue and sustainability of clubs at the lower levels of the pyramid.

The Review carefully investigated these issues, including the financial disparity between the leagues (particularly between the Premier League and Championship), measures taken to address these to date such as parachute payments (i.e. payments to relegated teams to soften the financial blow of relegation) and the impact this disparity has on the pyramid. It concluded that there is a strong case for some additional distributions from the Premier League to the rest of football. In simple terms, even modest additional funding allied with sensible cost controls could secure the long-term financial future of League One and League Two clubs as well as make a substantial contribution to the grassroots game.

The Review considered carefully whether the Review or IREF itself should directly intervene on the question of financial distributions. On balance, it considered that it would be preferable that this should be left to the football authorities to resolve. However, given the poor history of the industry reaching agreement, the Regulator should be given backstop powers that can be used if no solution is found.

The Review also carefully considered the question of so-called parachute payments. On balance, the Review concluded that although the intention of parachute payments is laudable the system should be reformed as part of wider reform of distributions. This reform needs to deliver an evidence based solution, with compromises on both sides and creative thinking to resolve the apparent impasse between the Premier League and EFL on this issue. The Review was made aware that the Leagues are in discussions on parachute payments, and it is hoped that they will reach a mutually beneficial conclusion. If football cannot find a solution by the end of the year, the Review has concluded that the Premier League and the EFL should jointly commission external advice to develop a solution to parachute payments as well as wider distribution issues.

However, if football cannot find a solution ahead of the introduction of legislation to implement the reforms set out in this report then IREF should be given backstop powers to intervene and impose a solution. The formation of IREF is therefore a deadline for the football authorities to resolve this issue or face an imposed solution. External involvement in this process would be another example of football’s failure to put aside self interest and protect the long-term interests of the game.

The Review also investigated the impact of salary costs, by far each club’s biggest cost, in a relegation scenario. The Review concluded that a pragmatic solution would be for a new clause to be introduced to player contracts adjusting salaries by a fixed percentage on both promotion (upwards) and relegation (downwards). In this way, relegation risks can be mitigated but players can also be rewarded for success. Providing for a fixed percentage increase or decrease also avoids the amount of the uplift or decrease becoming part of a competitive recruitment scenario.

In addition to consideration of increasing distributions and reforming parachute payments, the Review has also considered other possible approaches to provide greater support throughout the football pyramid. Of these, the Review considered that the most progressive intervention is a new solidarity transfer levy paid by Premier League clubs on buying players from overseas or from other Premier League clubs. This would work in a similar way to stamp duty and distribute revenues across the pyramid and into grassroots.

If a 10% levy had been applied in the last 5 seasons, an estimated £160 million per year could have been raised for redistribution. This would be a relatively modest cost to Premier League clubs (particularly given the relative financial advantage of the Premier League over other European leagues because broadcast income will grow in years to come) but annually, could be game changing to the rest of the football pyramid. One year’s payments illustratively could fund all of the below, which would benefit men’s, women’s, boys’ and girls’ football for the long term:

- a grant to ensure that League One and League Two clubs broke even[footnote 1]

- 80 adult 3G pitches

- 100 adult grass pitches

- 100 children’s/small sided grass pitches

- 30 two team changing rooms (including referee facilities)[footnote 2]

The final aspect of chapter 9 is consideration of ways that lower league clubs might generate additional revenue for themselves. In particular, it notes that there are two areas that clubs are being prevented from doing so by regulation and law — the use of synthetic pitches in League Two and sale of alcohol. Given the widespread acceptance of use of modern synthetic pitches at the highest levels of the game — including by UEFA in the Champions League — the Review concluded that clubs should be allowed a degree of flexibility in the use of pitches. This might involve a ‘grace period’ before they are required to change to a grass pitch.

In regard to alcohol sales, the Review concluded that in light of the potential benefits to club sustainability and doubts about the effectiveness of the current law, the possibility of amending the law should be explored via a small scale pilot scheme at League Two and National League level carefully designed in conjunction with police advice alongside a possible review of the legislation, which would be the first such review in nearly 40 years of its existence.

Chapter 10 Moves from considering issues in men’s football to considering ways to grow women’s football. Although the bulk of the evidence to the Review concerned men’s football it also heard from many involved in the women’s game. It is clear that women’s football is on the verge of an exciting future. All those involved in this — including the FA — deserve great credit.

The Review also heard that despite this success and women’s football being, today, the top participation sport for women and girls in England, it faces its own significant challenges which are very different to those faced by the men’s game. The Review concluded that there is a potential for women’s football to have a powerful future, but that it is clearly at a crucial point in development. There are a number of fundamental issues that require resolution in women’s football to allow it to move forward on a sustainable footing for the future. Crucial issues, such as establishing the value of women’s football, its financial structure, support from the Premier League, and league structure cannot be resolved in isolation. They require a holistic examination, research and evidence based resolution to enable the sport to move forward strongly.

The Review concluded that it is only right that exactly 100 years after the FA banned women’s football, the future of women’s football is the subject to its own separate review to fully consider the issues. The Review therefore recommends that women’s football should have a dedicated review to consider the issues in detail and provide tailored solutions.

Chapter 11 Addresses issues of player welfare. Although this was not directly included in the Review’s Terms of Reference, the Review was presented with some concerning evidence regarding the impact of involvement with professional football on young and retired players. The common theme linking those exiting the game at academy stage and post professional career is an apparent gap in provision of aftercare. The Review concluded that football needs to do better and be more joined up in its approach — including better sharing of best practice. This should involve as an urgent priority, football stakeholders working together to devise a holistic and comprehensive player welfare system to fully support players exiting the game, particularly at Academy level but including retiring players, including proactive mental health care and support.

The comments in the preceding paragraphs related to club academies, but there were also additional and greater concerns regarding private academies which are not affiliated to clubs or the FA. The Review therefore concluded that the FA should proactively encourage private football academies to affiliate to the local County Football Associations to ensure appropriate standards of safeguarding and education for young players, including exploring ways to incentivise this affiliation, perhaps through operation of a ‘kite mark’ scheme or similar and prohibiting registered academies from playing friendly matches against unregistered private academies.

Strategic recommendations

The Review makes a number of detailed recommendations, which each relate to an overall strategic recommendation. The full list of recommendations is summarised at Annex A, and the strategic recommendations are:

Chapter 1: The case for reform

Introduction

As noted in the introduction to this report, this Review was established in response to three crises — the collapse of Bury FC, COVID-19 and finally the attempt by six English clubs to join a new European Super League — an existential threat to the English football pyramid.

The Review benefitted from over 100 hours of engagement, involving representatives of over 130 clubs, approximately 21,000 survey responses and the benefit of extensive expert input and research. This has identified a number of structural challenges which are set out in this chapter. Subsequent chapters will consider solutions to these problems.

Why does football matter?

Football is the national game and most popular sport in England. It boasts 14.1 million grassroots players,[footnote 3] 35 million fans attending the top four leagues per season and over 40,000 association football clubs[footnote 4] — more than any other country. England also has the oldest national governing body in the Football Association (FA), the joint-first national team, the oldest national knockout competition (the FA Cup) as well as the oldest national league, the English Football League (EFL).

The English Premier League (Premier League), established in 1992, has also grown into one of the most famous and lucrative sports leagues in the world. It is the most watched league on earth, featuring the most games covered of all European leagues per season. Out of the top 30 global highest revenue-generating clubs in the Deloitte Football Money League, 12 are English, more than double the next most represented country.[footnote 5]

Football clubs also sit at the heart of their communities and are more than just a business. They are central to local identity and woven into the fabric of community life. The rich history surrounding football clubs is invaluable to their fans, with many clubs having existed for over one hundred years. They play a huge and often invisible role in unifying communities across generations, race, class and gender. They are a source of pride, and often in hard times comfort as well as practical assistance. In many places they are also a crucial part of the local economy.

Through evidence gathered from fans and Supporters’ Trusts, the Review heard from a substantial number of clubs who have strong bonds with their communities, stretching further than their fan base. One example is Brentford Football Club who engage with thousands of young people across West London each year, offering initiatives such as weekly multi-sport sessions, mentoring, volunteering and training opportunities for young people. There are many other excellent similar examples at all levels of the football pyramid.

What is the economic impact and how does the market work?

English football generates significant levels of income and its growth has out-performed international comparators. In the last season of the old football system 1991/1992, the 22 clubs in the top division had collective revenues of £170 million a year. By the 2018/19 season, the collective turnover of the 20 Premier League clubs had increased to £5.15 billion.[footnote 6] The Premier League has revenues far in excess of any other country — €2.4 billion more than Spain, the next biggest league in terms of revenue.[footnote 7]

Nor is it just the Premier League that has experienced growth or that outperforms comparative leagues in Europe. In the second, third and fourth tiers of English football, revenues have increased from £93 million in 1991/92, to just under £1 billion in 2019/20.[footnote 8]

This success generates vast economic activity. Premier League transfers totalled £1.8 billion during the 2019/20 season, with a further £266 million in transfers from the EFL clubs’ transfer combined expenditure. The Premier League also exported £1.1 billion of broadcast rights around the globe in 2016/17.[footnote 9] International broadcast revenues were higher than the combined total of the other four major European leagues. In comparison to other major global brands, Ernst and Young estimate the Premier League overseas rights are more than twice the combined value of the broadcast exports of the major North American sports leagues.[footnote 10]

The unparalleled commercial value of the sport supports the provision of public services, with £2.2 billion of taxes paid to the UK government during the 2019/20 season.[footnote 11] It also creates jobs at home, with over 12,000 FTE jobs directly supported by the Premier League and a further 52,000 indirectly supported down the supply chain.

In addition to the commercial value of the sport, the elite game inspires both participation and significant investment in grassroots football. The Premier League funding of the Football Foundation since 2000 has contributed almost £500 million towards new facilities for schools, local clubs and communities.[footnote 12]

What are the structural challenges in football?

Since the Premier League started, the popularity of football has soared, television audiences have grown across the globe, sponsors have seen opportunity, and external investment has poured into the game. Football has been outstanding at increasing income. This success story of English football is a credit to the hard work and vision of countless people over many years but it is possible to simultaneously celebrate this achievement at the same time as having serious concerns about the future viability of football in this country. This Review has seen significant evidence of a range of impending financial problems in football. This brings the risk of significant long-term damage to the game and widespread failures by clubs.

There are three main reasons why football clubs are at this precipice, which are set out in more detail below:

-

The incentives of the game mean many clubs are gambling for success, leading to clubs facing financial distress.

-

Clubs are too often being run recklessly, owners make decisions with personal impunity frequently leaving communities and others to deal with the consequences/fall out of their decisions and fans are cut out of their clubs and key decisions.

-

The regulations and oversight of the game are not up to the task of ensuring a sustainable future for clubs.

A. The incentives in the game are leading to many clubs facing financial distress

The incentives of the game drive reckless decision making seeking to gain, and then maintain, the financial rewards of competing at a higher level. Deloitte estimates that promotion to the Premier League is now worth £170 million to a promoted Championship club. European competition revenues are also significant — particularly playing in the Champions League. At the 2021 Champions League final, Chelsea reportedly received £95 million in prize money, which included money earned by progressing through each stage of the tournament, with the true number likely to have been much higher.

Clubs see the riches at the top of the game and therefore chase success, or are driven by fear of relegation. They recruit new talent and increase the wage bill, in the hope this will improve on pitch performance. To stay competitive, other clubs are forced to spend as well. In the Championship, this is exacerbated by relegated clubs with parachute payments which massively boosts the income of relegated clubs as compared to others. Evidence provided to the Review has shown these clubs can ‘gazump’ rivals for the best talent or at the very least push wage costs up. This creates a perpetual vicious cycle as other clubs try to compete. In such a market, it is easy to see how wage costs could rise significantly but relative performance remains unchanged.

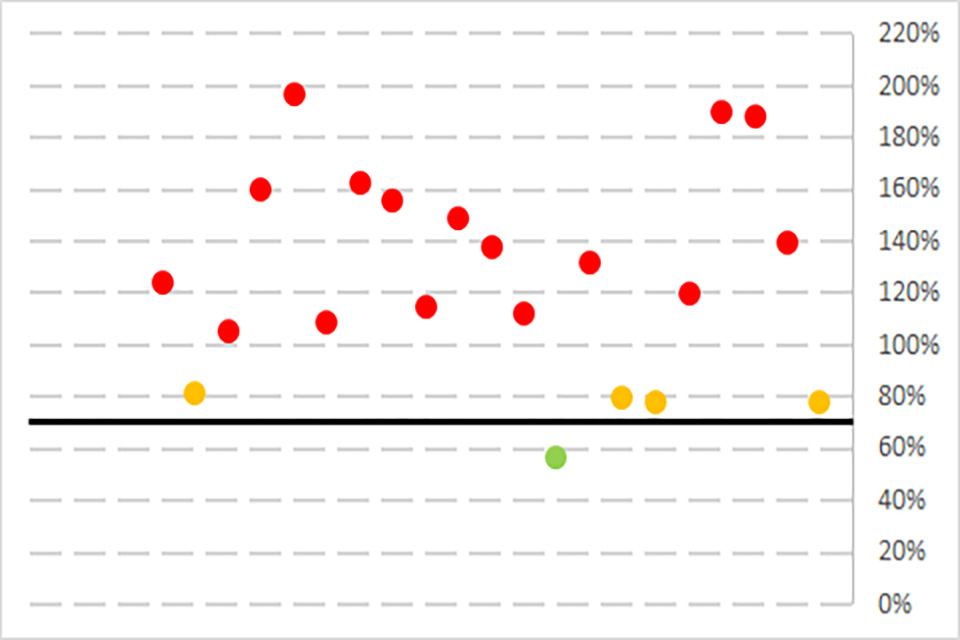

As a result, many English clubs are spending far more than they should, particularly on wage costs. UEFA has undertaken analysis which indicates that to have a chance of breaking even, total wages as a proportion of turnover should not go above 70%. However, in the Premier League this rate is 73% on average. Outside the six teams with the highest turnover, it is 87%. In the Championship, the rate is even worse, at 120%. In some instances, this figure is almost 200%. Rick Parry, Chairman of the English Football League and former Chief Executive of the Premier League, has described the speculative financing as ‘the most expensive lottery ticket on the planet’.

Nor does the financial situation necessarily improve once a club wins the lottery by getting to the Premier League as they are driven to spend to avoid relegation or try to progress to competing in Europe. A recent example of this can be seen in Brighton and Hove Albion which has shown that just trying to remain in the Premier League is costly. The club’s costs mainly relate to players, in the form of wages and transfers. In reaching the Premier League, Brighton made an operating loss in every year from 2011 to 2017, operating in its 2017 promotion season with a record loss of £38.9 million and a wage/income ratio of 138%. In the first season in the Premier League, income increased significantly and the club made an operating profit of £12.8 million. The club avoided relegation in that season — and went straight back to making an operating loss of £19.4 million and £63.9 million in subsequent seasons alongside wage/turnover ratios above the UEFA ‘safe’ figure of 70% in both seasons. The club’s debt increased to over £300 million from £191 million in 2017. Brighton’s on pitch performance resulting from this spending is credible, but in none of the seasons covered by these financials did it finish higher than 15th. So despite achieving and maintaining Premier League status at a modest level, Brighton’s financial position was no better in 2020 — and arguably worse — than it was in 2017 despite the huge increase in its income.

The result is unsurprising. In the Premier League, pre-tax losses were £966 million in 2019/20, with huge losses expected for the 2020/21 season due to the additional COVID-19 impact. Since the 1999/2000 season 17 out of the 21 (80%) seasons of the Premier League have seen collective pre-tax losses. Further, despite the huge revenue generation, collective losses in that time have been almost £3 billion as clubs spend high to stay in the league, and spend higher to compete or try to compete for a chance in the Champions League.

In the Championship, losses have been even worse as clubs spend well beyond their means in aim of promotion to the Premier League, exacerbated by relegated clubs with parachute payments. Since 2010/11, Championship clubs have made a loss every season. Those pre-tax losses have been almost £2.5 billion — almost as much as the Premier League but in half the time and despite significantly lower revenues compared to Premier League clubs. In both leagues, debt is also rising significantly and currently stands at an aggregate £5.3 billion.

Chart 1: Premier League and Championship club revenues 2019/20 (£m)

| Club type | Matchday | Broadcasting | Commercial | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCL clubs | 66 | 178 | 200 | 444 |

| UEL clubs | 61 | 118 | 148 | 327 |

| Premier League (other) | 13 | 100 | 28 | 141 |

| Premier League (relegated) | 8 | 89 | 15 | 112 |

| Championship with parachute | 5 | 39 | 8 | 52 |

| Championship without parachute | 5 | 8 | 7 | 20 |

Since the formation of the Premier League in 1992, clubs have fallen into administration 62 times, some more than once. A number of these clubs have survived, for example Leeds United, Leicester City, Portsmouth, and Exeter City. Some of the clubs which have gone into administration have gone on to be promoted through the leagues and are now financially stable. Although none of these administrations was ‘pain free’ for those involved these clubs at least survived. There is also an unacceptable number of clubs who could not be saved: Bury, Macclesfield Town, and Rushden & Diamonds — all falling into liquidation, and taking with them huge chunks of history, heritage and the hearts of a community.

The Review has therefore concluded that the financial incentives of the game are warping decision making, at all levels of football. Clubs are locked into perpetual cycles of spending far more than they should. Losses are accumulating and debts rising. Clubs are completely exposed to the good will of owners and lenders and there is no in-built resilience in clubs as a result. Clubs, on a wide scale are facing the financial precipice and the consequences of widespread losses would be catastrophic. Change is needed and it needs to be bold.

B. Clubs can be poorly run, with poor decisions and there is a disconnect between the interests of fans and owners

The long-term health of football relies on clubs being run sensibly, making rational decisions and planning for a long-term sustainable future. A common theme in clubs facing difficulties is owners and directors making reckless short-term decisions which result in negative outcomes for the club aided by a lack of good corporate governance structures to challenge decisions, consistent financial losses, poor fan engagement and as a result, unstable futures. A good example is Birmingham City where evidence, submitted during the Review, alleged that the club is currently over £100 million in debt, has breached Profit and Sustainability rules and is in a situation where the club and the ground are owned by different people, under a complicated offshore ownership structure.

Good corporate governance can help with decision making, providing a diversity of opinion and expertise to clubs’ decisions, as well as transparency and accountability. This ensures good decisions are more likely and improves the confidence of fans in the running of their club.

However there are many examples in football of corporate governance that would not be tolerated in other industries. This is true even in the Premier League, where arguably the worst example in recent times was Newcastle United which, until the recent takeover, has had a Board of one, the person in question being also the company’s top executive officer. Other obvious examples of poor governance include Reading and Derby County which both appear to lack proper board structures. Reading spent approximately twice its revenue on wages in 2019/20 and Derby County has just gone into administration. A proper system of corporate governance would have subjected the very risky business decisions by these clubs to scrutiny and challenge.

Engaging with fans is also an important part of good club decision making. There are a number of clubs and owners who follow strong fan engagement practices. However, the evidence from the Football Supporters’ Association is that despite existing EFL and Premier League rules containing requirements for fan consultation, there ‘…has been limited progress on delivering the relatively unambitious minimum standards…’.[footnote 13] The European Super League is the highest profile example of a massive disconnection between clubs and their fan bases, and a clear example of why better fan engagement is needed.

Another outcome of poor business decisions and lack of engagement with fans is the loss of club heritage. According to the Football Supporters’ Association, in the last 25 years, more than 60 clubs have lost ownership of their stadium, training ground or other property. Clubs who lose ownership of their ground have also often been forced to relocate away from their hometown. The highest profile example is Coventry City which played in Northampton between 2013 - 2014, and in Birmingham in 2019 - 2021. However, there are many others including Darlington which spent 5 years playing 13 miles away from Darlington, Scarborough Athletic which was based 18 miles away from its home town for 10 years, and most infamously Wimbledon — moved to Milton Keynes as a new team MK Dons.

The Review have also seen evidence of decision making where no regard has been given to the fans and communities of those clubs. There have been attempts to change club names (Hull City), and changes to strip (Cardiff City) and location (MK Dons/Wimbledon). Although these case studies are less frequent, the importance of club heritage to local communities and fans means that there is a special case to offer additional protections as is done in order to protect other items of non-sporting cultural heritage.

Owners have driven century old clubs to ruin. Above all else this is the issue, no one should lose their club due to its community value. Clubs and assets should be protected from vultures.

Contributor to Fan-Led Review online survey

The evidence of poor decision-making by clubs at the very least raises questions of whether or not the right people are becoming the owners or directors of clubs. The Review has seen evidence of numerous failings of the current Owners’ and Directors’ tests (‘ODT’), with the resultant acquisition of clubs by owners unsuited to the custodianship of important cultural, heritage assets, as well as the appointment of unsuitable directors who do not effectively contribute to the running of the club. Examples of unsuitable owners include, but are not limited to:

- owners with long histories of prior business bankruptcies

- owners who acquired clubs without proof of funds (albeit that such loophole has apparently been closed)

- owners who have subsequently been imprisoned for offences including money laundering

- owners with serious criminal convictions

- clubs changing from stability under long-term owners to near extinction in three years

- owners who engaged in multiple legal disputes with the club, other owners and fans

- offshore hedge funds with unclear ownership acquiring clubs

- a club being put into administration by an owner who had only purchased the club two weeks earlier

- owners who appear to have done little or no diligence prior to acquiring the club

- directors appointed to club boards despite no significant prior experience.

It would be wrong to put all owners into the same box. The Review has also seen examples of owners who have supported their club for no other reason than commitment to their local area and done it well, like Accrington Stanley. The Review has also seen evidence of successful owners, those who make selfless investments into their club year after year, who are good people with sound motives without whom many clubs would not exist but living in a system where the price of prudence and sound finance is often ‘failure’ on the pitch given the unreasonable incentives and lack of controls. Rotherham United is a good example of a club with an owner who seems to try and run the club on a sustainable basis yet who are disadvantaged in trying to compete in the Championship. And even where the current owner of a club is ‘good’ as said by one fan group in evidence ‘A club is only one bad owner away from disaster’ or the system can drive a well meaning owner to make reckless decisions.

I’m a Wycombe Wanderers fan and the current owners are superb. But in the past we have had terrible owners who tried to sell our ground. So it shows for every good owner there is a bad one.

Contributor to Fan-Led Review online survey

C. Regulation and oversight of the game is substandard

Loss of public confidence

Lack of public confidence likely stems at least in part from a system that is confused and where clarity on the roles of regulators is opaque. Evidence taken through the Review showed key stakeholders have lost confidence in the current domestic football authorities. This was echoed in the results of the Fan-Led Review Online Survey, which ran in July 2021, and amongst other questions, asked “How do you rate the performance of each of the following regulatory bodies as regulators in English football?” The table below sets out the results, which shows the number of people rating the performance above average (good and very good), particularly of the FA, PL and EFL, is low. With the exception of the National League, the majority consensus from this survey was that the performance of the authorities is below average (poor and very poor).

| Authority | Good and Very Good | Average | Poor and Very Poor | Don’t Know | Total Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Football Association | 15% | 37% | 44% | 3% | 17,907 |

| Premier League | 15% | 27% | 56% | 2% | 17,819 |

| EFL | 14% | 27% | 49% | 10% | 17,832 |

| National League | 16% | 23% | 26% | 35% | 17,773 |

Of course, the financial instability and other severe problems faced by the game itself questions the efficacy of the existing regulatory system. It was this system under which the problems arose. As football has grown, the complexity, sophistication and range of challenges has expanded, likely to a point beyond what could have been foreseen when the current structures were created, thus straining the ability of the current domestic authorities to address the many problems arising.

Conflicted regulators

The constitutional set up of the existing authorities is also inherently conflicted, with the rules of regulation being set by the parties that are to be regulated. In the Premier League for example 14 votes from clubs are required to pass a rule change and in the EFL for a change in regulations to be carried, it must be passed by a majority of votes cast by all member clubs, and at the same time, passed by a majority of the votes cast by all member clubs in the Championship. Understandably, clubs are incentivised to prioritise their own interests rather than taking a long-term view of what is best for the game. One example of this is the EFL’s corporate governance reforms. The EFL instructed a leading sports QC to recommend improvements to its governance but did not adopt the recommendations in full with member clubs rejecting fully independent EFL board membership in favour of retaining club appointed directors.

There is also an inherent conflict with an organisation taking disciplinary action against their own shareholders, particularly where that action might have significant negative commercial impact on the organisation. This can disincentivise enforcement action, or even the allocation of sufficient resources to investigation and enforcement functions.

Lack of resource

Even where there are rules in place, the Review has heard that the authorities are under-resourced, particularly when faced with enforcing rules against sophisticated modern businesses. An effective regulatory system should undertake investigation and reach a conclusion in a timely manner; but this is not always the case in football, leading to an unsatisfactory situation that suits no-one involved. As noted by the Court of Appeal in a recent judgement relating to a legal action involving Manchester City and the Premier League:

This is an investigation which commenced in December 2018. It is surprising, and a matter of legitimate public concern, that so little progress has been made after two and a half years — during which, it may be noted, the club has twice been crowned as Premier League champions.[footnote 14]

Missed opportunities for reform

In the past, the domestic authorities have had multiple opportunities for reform with little or no progress made. The 2011 DCMS Select Committee’s report set out a package of conclusions and recommendations including the creation of a modern, accountable and representative FA Board, the implementation of a licensing framework administered by the Football Association in close cooperation with the professional game and changes to the decision-making structures within the FA, specifically in relation to the Council.

There was also an expectation following the 2011 DCMS Select Committee’s report that the football authorities would agree and publish a joint response setting out the process for how they intend to take forward their plans to address these immediate priorities — this was not produced.

Another example was the unanimous resolution passed by the FA Council in October 2019, which also called on the FA to produce proposals for reform. The resolution stated ‘it believes that these failures [failure of Bury and others] indicate that the current financial and governance regulatory framework in the professional and semi professional game needs strengthening’ — this proposal has not been acted on.

In fairness, it should be noted that the domestic authorities have all taken some recent steps to improve the way in which they operate. The National League has undertaken significant constitutional reform by addressing the difficulties in its voting structure. The FA has taken small steps towards a more modern independent board with the creation of two new independent non-executive director roles. The Premier League is working towards reforms of its own constitution by adopting the Wates Corporate Governance principles for large private companies. Further it is understood that the EFL is taking steps to improve its own financial enforcement mechanisms. All these steps are welcome and the authorities are strongly urged to continue the process of reform. However, many of these simple changes have been called for by stakeholders for some time — including the 2011 DCMS Select Committee report some 10 years ago. They still do not go far enough. The problems football is facing are complex and pressing and cannot wait for further reform — which there is no guarantee the authorities will be able to deliver.

Lack of one voice

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, football clubs stepped up right across the country underlining the deep roots and connection to their communities. Many clubs up and down the country were at the forefront of the response to COVID-19. Many turning themselves almost entirely into community support organisations to help provide practical and moral support. Whilst all this was happening many were internally questioning their own future viability as businesses.

The football authorities’ response to the dire financial situation they, and many businesses, found themselves in during the pandemic perhaps best illustrates the different vested interests at play within the game and how they can restrict the ability of the authorities to take unified action. The government made it clear early on in the pandemic that it was not going to provide specific funding for Premier League and EFL clubs given the billions spent in the transfer window that summer (2020). Despite this, it took until December for the two organisations to come to an agreement on a financial support package for the EFL. The issue was characterised by one commentator as ‘nearly six months of gridlock, uncertainty and bickering with the government’.

Lack of accountable leadership

The system lacks clearly accountable leadership. As an example, Leyton Orient had stable ownership for many years but was transferred to new ownership, leading to dramatic consequences for the club. Instead of intervening, the EFL maintained that they were ‘only a competition organiser’, a phrase heard repeatedly throughout the review including from Bury fans. And failures of the EFL to intervene during a turbulent period for Charlton Athletic, despite supporter pleas, leading to legal action. Similarly, several fans groups reported to the Review that the FA offered no assistance when they were faced with difficulties threatening the viability of their clubs. It is not clear to clubs and fans if the authorities do not want to or cannot intervene, or if the system prevents them from doing so.

A sub-standard regulatory system has overlaps and underlaps of regulation. Oversight should look across issues and competitions, to deliver for the whole game. But there are varying levels of oversight, including the Premier League, EFL, National League, and the FA. Issues can fall between bodies; the European Super League proposal was an issue without a clear lead body to deal with it. Owners’ tests or financial rules have interest from all competitions, although in some instances no clearly accountable body. This is not conducive to good outcomes.

Football authorities have shown they are either not willing or capable of doing this, particularly league authorities, and therefore change should be forced upon them.

Contributor to Fan-Led Review online survey

The need for action

Some will argue, given the apparent success of English football, why change? The Review has formed the firm belief that our national game is at a crossroads with the proposed ESL just one of many, albeit the most recent and clearest, illustrations of the many deep seated problems in the game. The game is at real risk of widespread failures and a potential collapse of the pyramid as we know it. There is a stark choice facing football. Build on its many strengths, modernise its governance, make it fairer and stronger still at every level or do nothing and suffer the inevitable consequences of inaction in towns and cities across the country — more owners gambling the future of football clubs unchecked, more fan groups forced to mobilise and fight to preserve the very existence of the club they love and inevitably more clubs failing with all the pain on communities that brings.

Action must be taken, and with the previous track record of the authorities not responding to advice there is no evidence to suggest that this time it will be different. The Review believe the time has come for the government to take action, that is why a new independent regulator is needed to help fix the rising problems and ensure the future stability of our beautiful game.

Summary

In summary, the Review has concluded that:

- the men’s game is at the financial precipice, because the incentives are driving poor and reckless decision making

- this is exacerbated because corporate governance in clubs can be poor, there is too often too little diversity of thought and owners can act with impunity, ignoring the interests of fans.

- added to this, the short term interests of owners and long-term interests of fans are not always aligned

- the system of regulation in place is poorly designed, there is a conflict of interest as regulations are overseen by those that are regulated, football is unable to act at pace or make changes to its setup and there is a lack of clear regulatory leadership

- fans have lost faith in the football authorities

It is for these reasons that this Review has concluded that change must follow to ensure the long-term health of the men’s game.

Chapter 2: Regulation

Introduction

In chapter 1, we have shown a clear problem in football. The review has concluded that there is a strong case that without intervention, football at many levels risks financial collapse.

Ensuring a long-term and healthy future is possible, but football needs radical reform, with a complete overhaul of the existing approach to business regulation. The Review has considered how best to do this including whether the government should intervene. We have started from the point that the bar for government intervention is high and assessed the alternatives. The Review has considered four alternatives:

-

Leave poorly run clubs to collapse and allow the market to resolve issues.

-

Allow a football-led solution, building on 150 years of self-regulation.

Option 1: Leave to the market

If football governance is left as is then there is an existing system for club failures. Clubs either go into administration or, in extreme, liquidation. In fact, the current football system and UK insolvency system has been engaged in football a number of times.[footnote 15] The last two years have seen collapses at Bury, Bolton Wanderers, Derby County, Macclesfield Town, and Wigan Athletic.

In an administration, the legally appointed administrator will attempt to keep the club going by resolving or restructuring debts and seek a new owner for the club. League rules also impose some bespoke requirements as compared to an administration in other industries. The highest profile is the ‘football creditors’ rule whereby a protected class of creditors must receive full payment before a club is allowed to continue in the league. In a liquidation, the club is wound up and its assets sold to try to discharge the club’s debts. Ultimately, another club will replace the club in the league. The existing club ceases to exist, though a ‘phoenix club’ can be created in the same community which then restarts at a lower point in the pyramid.

This system generally leads to: non football creditors being repaid a fraction of what they are owed; significant job losses in a club; the club’s best players being sold; a long distressing period of uncertainty for a club’s fans; vulnerability to unsuitable owners looking to take advantage of a club and points deductions impacting on the sporting outcome of competitions. In extreme, clubs go out of existence with a devastating impact on local communities. Given the perilous state of the game, and the systemic nature of problems identified, it is not unreasonable to consider that wide scale failures could happen at the same time.

Consequently, this approach is deeply unsatisfactory. There are superior options.

Option 2: A football-led response

When it comes to the rules of the game, the model of self-regulation has operated for 150 years, having been created at a time when regulation of any kind was uncommon in society. However, society has changed a lot since then, and football itself has changed hugely in the last 30 years. It is no longer just a sport — it is big business. In 1991/92, the revenue of the top 22 clubs was £170 million combined. Premier League revenues were over £5 billion before the pandemic.[footnote 16]

The range of issues faced by those overseeing the regime has correspondingly increased in complexity. The set up of the system, with regulation split across several bodies, is not optimal — a regulator should be thinking about issues in the round and connecting different parts of the regime. The bodies that make the rules lack the clearly defined objectives of a normal regulator. They also have strong commercial interests and are effectively controlled by those that are to be regulated. That is a clear conflict and makes meaningful change hard to achieve.

The nature of regulation is changing and faces sophisticated businesses, complex market shaping regulation and distributional issues. Original regulations covered team kits, the rules of the game or eligibility of players. However, given the nature of the problems, reform needs to include complex issues like cost controls. This involves designing a system to prevent clubs going out of business while balancing competing factors like avoiding red tape and ensuring healthy competition. These are not the areas of traditional sports governance and to regulate them effectively will need new skills and expertise not currently in the game. The problems to be addressed are not core football regulation addressed by traditional self regulation, but specialist business regulation.

Option 3: Co-regulation

Co-regulation usually involves the industry or professions developing and administering its own rules, but with the government providing legislative backing to enable the arrangements to be enforced. This approach can strengthen a self-regulatory system as requirements being enforced are set out in law. While a self-regulation model is in essence a voluntary system, co-regulation can be stronger because of its legal footing.

A system of co-regulation could be employed in football. However, in this case it is not viable for a number of reasons:

- Problems would remain around the constitutional setup of the leagues and authorities that would enforce this system. These bodies have commercial interests and are made up of the clubs who are to be regulated, both representing a conflict of interest and an unsatisfactory approach to regulation.

- The issue of the current system being overseen by several bodies, who are disjointed and disconnected, with overlaps and underlaps of oversight, still remains.

- Football authorities would need to come back to Parliament to request new and additional regulation if new issues occur. Legislative change can be slow, therefore this model is slow and lacks agility.

- As with self-regulation new and complex issues are business regulation that sports and football currently do not have experience or expertise.

Option 4: Independent regulation

The terms of reference for the Review specifically included considering calls for an independent regulator in English football. The Review has assessed this option against the three root causes of problems identified in chapter 1:

-

The incentives of the game mean clubs are at the financial precipice.

-

The way clubs are run and the misaligned interests of fans and owners.

-

The existing regulatory setup is not able to correct problems.

Finances: Given the dire state of football finances, bold leadership and difficult decisions are needed. Current oversight of financial rules is led by leagues, made up by the clubs that will be regulated. Taking bold decisions and being able to secure support for that change is very difficult. Most importantly, there is a clear conflict of interest between the interests of clubs and their direct or indirect involvement in oversight of the system that regulates them. Independent regulation is the only way to overcome this issue as it will not have a conflict of interest. As a statutory body with a clearly defined purpose it will listen to but not be constrained by the voices of clubs, enabling it to effect change in a timely way.

How clubs are run: If football led, oversight of this issue would be led by the leagues, which are run by the clubs. By definition, this must tip interests in favour of owners. It seems unrealistic that leagues (that would enforce rules) would be able to objectively balance the range of stakeholders in the same manner as an independent body. These are complex issues and an independent regulator should have a statutory objective to look after the interests of fans but also reflect the views of all parties.

Regulatory setup: The review has considered best practice in other important industries where a proactive regulator helps shape that industry to deliver good outcomes — for example, in financial services. While many of these systems have their own rules and industry codes in a similar manner to football, oversight of the system by a regulator has been a force for good. It is hard to argue that football would not benefit from a regulatory system overseen by an independent body focused on the long-term interests of fans, clubs and the wider game.

An Independent Regulator can also be more adaptable and flexible to problems in football. Unlike the other options considered, where regulatory change requires securing a mandate or approval from clubs or the government, an Independent Regulator can take a swifter approach to updating regulations — especially on contentious issues. In the other models considered, securing agreement from enough clubs could be difficult. Taking action and enforcing against the biggest and most powerful clubs is an issue in self-regulation (for example, there may be commercial or political reasons why enforcement is constrained). However, an independent body is free to take action against offending clubs, separate from large or influential clubs.