Outcome evaluation

Published 7 August 2018

Introduction

An outcome evaluation can tell us how effective an intervention is by asking ‘Did it work?’ and ‘How well did it work?’ These studies investigate whether changes in outcomes occurred as a result of the intervention.

Intervention outcomes

An intervention outcome is a measure of something that the intervention was expected to change. This could be something about participants or their environments. Outcome evaluations can employ primary and secondary outcomes. The primary outcome is the main change the intervention was designed to generate and is the endpoint of the logic model. Identification of the primary intervention outcome measure is central to intervention design.

Secondary outcomes are usually measures of effects expected to follow from primary outcome. For example, an intervention might be designed to promote weight loss (the primary outcome) but also expected to enhance quality of life as a secondary outcome. Interventions are designed to change a wide variety of outcomes so, depending on the initial needs assessment, many different primary outcomes may be considered. For example:

- increasing knowledge or awareness (for example, about a health threat)

- changing beliefs or attitudes

- enhancing motivation

- promoting particular behaviour patterns (for example, physical activity, condom use or adherence to medication)

- reducing the prevalence of health-risk factors (for example, blood pressure or BMI)

- reducing the incidence of health conditions/ diseases (for example, heart attacks or sexually transmitted diseases)

- changing use of services (for example, GP appointments or hospital admissions)

Reliability and validity of outcome measures

The reliability of an outcome measures is the degree to which it generates the same score or value when it is used repeatedly in unchanging circumstances. For example, if a weighing machine generates different weights for the same person over a single afternoon then it is unreliable. Reliability is prerequisite to the validity and usefulness of an outcome measure. Ensuring that a reliable measure of the proposed outcome is available and can be use in practice is a critical aspect of evaluation design.

Validity of outcome measures is the degree to which a measure or test can be said to really measure what it is designed to measure. Concurrent validity is achieved when two or more tests generate the same findings. The tests validate one another. For example, if two weighing machines give the same weight for the same person on the same afternoon, it suggests that they are both measuring the same thing – weight. Predictive validity is achieved when a measure predicts a future measure. For example, when a fitness measure predicts performance in a subsequent test of strength or endurance.

Evaluation design involves identifying reliable and valid outcome measures. This is likely to involve searching the research literature early in the design process.

Outcome evaluation design

Several different study designs are used in outcome evaluations. We briefly discuss three here. In a single-group pre-post comparison, outcomes are measured before and after the intervention. Then post-intervention levels/scores are compared to pre-intervention scores to assess change. This design provides relatively weak evidence of effectiveness because changes occurring outside the intervention may be mistakenly attributed to the intervention. For example, the season or media coverage may be changing the primary outcome quite apart from the intervention itself.

A stronger design would use a matched control group who do not receive the intervention. This allows comparison of change in the intervention group to change in the control group. So naturally occurring change (not caused by the intervention) can be measured. The intervention and control group should be as similar as possible so that naturally occurring change relevant to the intervention group is captured by measuring change in the control group. This design allows change in the intervention group to be judged in relation to change in the control group.

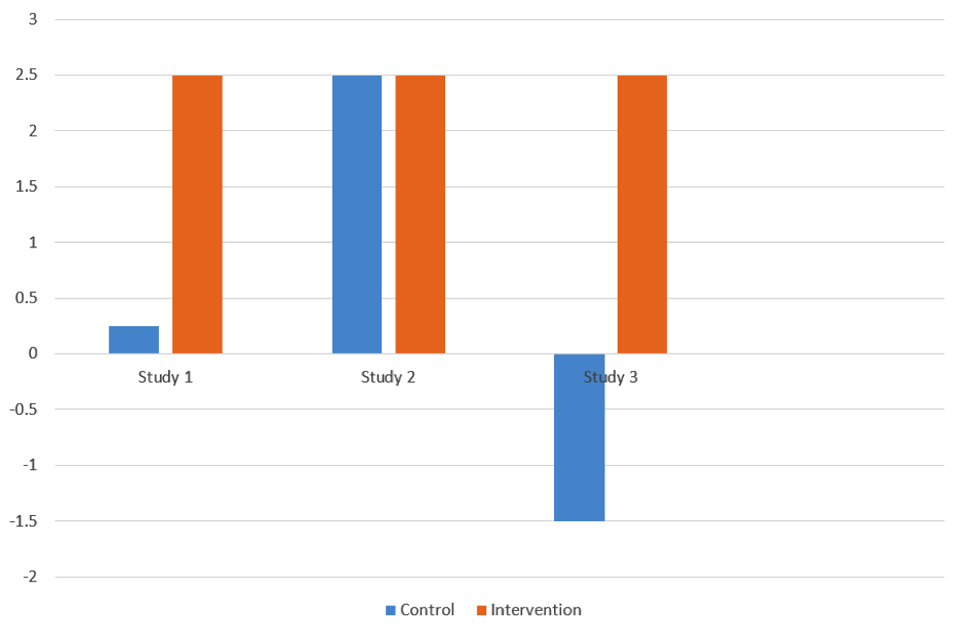

The graph illustrates hypothetical findings from 3 outcome evaluations. The first study shows an intervention group doing much better than the control group who show a small improvement, so the intervention may have had a real effect. In the second study the intervention group changes by the same amount but, because the control group also changes by this amount, it appears that the intervention was ineffective. In the third study the same change in the intervention group is contrasted with a deterioration in the control group, suggesting that the intervention may have prevented naturally occurring deterioration and well as prompting improvement.

Outcome evaluation graph showing control and intervention study results

A yet stronger design is provided by a randomised control trial in which study participants are randomly allocated to the intervention and control group. Randomisation provides better matching because differences between participants should be evenly spread between the two groups. This means that such differences should not affect differences in change between the two groups. Randomisation may be managed at an individual level, or organisational level (for example when comparing one GP practice or school to another).

Another important outcome evaluation design question is when to measure the outcomes. In addition to pre-post intervention measures, intermediate measures may be taken during the intervention to track progress (eg, weight loss measures each week during a three-month intervention). These are especially important in process evaluations.

Immediate follow-up measures can tell us what happened once the intervention was complete (eg, weight loss measures at the end of the intervention). Longer-term follow-up measures can tell us whether immediate post-intervention changes were maintained, that is, remained stable over time. Such follow-up measure may be taken at any time after the intervention (eg, at 6, 12 or 24 months).

Efficacy versus effectiveness evaluations

Efficacy is the capacity of the intervention to generate change when delivered properly (for example, by experts) in favourable/ideal circumstances. Efficacy evaluations can demonstrate the potential of an intervention. Efficacy evaluations may be small scale (for example, a 2-site trial or a laboratory study).

Conversely, effectiveness is the capacity of the intervention to generate change when delivered in practice (for example, as part of routine service delivery). Effectiveness evaluations (for example, multisite service randomised control trials) may be challenging and expensive to conduct and are usually best undertaken once good efficacy has been demonstrated.

Efficacy does not guarantee effectiveness.

External validity

External validity is the extent to which the findings of an outcome evaluation can be generalized to other groups and contexts. For instance, is a weight-loss intervention found to be effective for overweight adults likely to work for overweight British children?

A limitation of randomised controlled trials is that the very careful selection and randomisation of participants and the control of the intervention-delivery contexts may mean that observed effects of interventions in trials are not replicated in (or do not generalise to) routine practice. So a trial may demonstrate efficacy but not effectiveness across contexts.

This potential disjunction between the findings of well-conducted trails and real- world implementation is referred to as ‘external validity’ The RE-AIM framework (Glasgow et al, 2002) helps to anticipate challenges to external validity in the adoption, implementation and maintenance of interventions. The framework details five dimensions of external validity:

Reach

- number or percent of target population impacted

- extent that the participants represent the population and are the most at risk

- participation rate, representativeness and exclusion rate

- effectiveness

- measurement of intervention impact on health or behaviour patterns including the positive, negative and unanticipated consequences

Adoption

- extent to which intervention in adopted by implementers

- extent that participating settings are representative of ‘real world’ settings that the target population uses or visits.

Implementation

- whether intervention components delivered as intended; time and cost

- adherence to protocols or guidelines

Maintenance

- for organisations: integration into the systems, staff, and budgets

- for individuals: continuation to exhibit the desired health behaviour change(s)

Outcome evaluation challenges

Practical challenges of outcome evaluations include the following:

- interventions may impact at several levels so multiple valid and relatable outcome measures may needed

- if care is not taken, measurement could be affected by researcher expectations

- randomisation may lead to demoralisation or competition. For example, those assigned to the control group may be disappointed

- large samples may be needed to measure change, especially if the expected change is small. Therefore, study recruitment may be challenging

- intervention and control groups may be difficult to isolate so resulting in ‘contamination’

- people or sites may drop out – causing ‘attrition’

Challenges associated with designing outcome evaluations:

- defining outcomes during evaluation design, both primary and secondary outcomes

- ensuring reliability and validity of all outcome measures

- deciding how to measure effect sizes

- establishing the size of change that is important or useful (practical or clinical importance)

- deciding on an evaluation design

- deciding when to measure outcomes

- conducting efficacy evaluations before effectiveness evaluations

- conducting process evaluations to optimize external validity

Review questions and answers on outcome evaluations

How outcome evaluation differs from other types of evaluation The purpose of an outcome evaluation can tell us how effective an intervention is. These studies investigate whether changes in outcomes occurred as a result of the intervention. This is achieved by measuring something at different time points (eg, pre and post intervention) that the intervention was expected to change, or intervention outcome.

How I can start to design an outcome evaluation

The first steps are to determine what the aim of your intervention is and how you will measure the intervention outcome. The logic model will inform you of the aim of the study. You need to make sure that your intervention outcome measure is reliable (generates the same score or value when it is used repeatedly) and valid (measures what it is designed to measure).

You will also need to consider the study design that you plan to use (for example, single-group pre-post comparison, matched control group, or randomised control trial). Each of these designs provides varying levels of evidence, with a randomised controlled trial proving the strongest evidence. Another important design element of outcome evaluation is when to measure the outcomes: pre- and post-intervention, during the interventions, and / or short- and long-term follow-ups.

The difference between efficacy and effectiveness

Efficacy is the capacity of the intervention to generate change while effectiveness is the capacity of the intervention to generate change. Efficacy evaluations may be small scale (for example, a 2-site trial or a laboratory study), and effectiveness evaluations may be on a larger scale (for example, multisite service randomised control trials). Effectiveness evaluations can be challenging and expensive to conduct and are usually best undertaken after good efficacy has been demonstrated. However, demonstrating efficacy does not necessarily mean an intervention will be effective.

Why external validity is important

External validity is whether the findings of an outcome evaluation can be applicable to other groups and settings. The observed findings of the study (for example, benefits of a weight loss intervention) may only work in the study conditions and not in the ‘real world’. It is important to assess external validity because the ultimate goal of designing and testing interventions – particularly, public health intervention – is so they can be implemented widely. If the intervention is not externally valid then a great deal of resources will have been used to test an intervention which has no application in everyday life. The RE-AIM framework can be used to anticipate some of the challenges to external validity.

Selection of useful resources

HM Treasury (2011). The Magenta Book: guidance for evaluation

Medical Research Council (2006). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance

NHS Health Scotland (2003). LEAP for health: learning, evaluation and planning. Edinburgh: Health Scotland

NHS National Obesity Observatory (2012). Standard evaluation framework for dietary interventions

NHS National Obesity Observatory (2012). Standard evaluation framework for physical activity interventions

NHS National Obesity Observatory (2009). Standard evaluation framework for weight management interventions

United Nations Development Programme (2009). Handbook on planning, monitoring and evaluating for development results

UN Women (2013). Ending violence against women and girls: progamming essentials

UN Programme on HIV/AIDSA (2008). Framework for monitoring and evaluating HIV prevention programmes for most-at-risk populations

W K Kellog Foundation (2004). ‘Logic model development guide: using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation and action’ Battle Creek MI: W K Kellog Foundation

Written by Charles Abraham, Margaret Callaghan and Krystal Warmoth, Psychology Applied to Health, University of Exeter Medical School

Acknowledgement:

This work was partially funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research, the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care of the South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC) and by Public Health England. However, the views expressed are those of the authors.

References

Cohen, J. (1992). ‘Theory of Change: a theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions’ A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155-159. Trials 15: 267 doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-267

Glasgow, RE, Bull, SS, Gillette, C, Klesges, LM, Dzewaltowski, DM (2002). ‘Behavior change intervention research in healthcare settings: a review of recent reports with emphasis on external validity’ American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 62-69.

Access a series of supporting materials: