HM Government transparency report: disruptive powers 2020 (accessible)

Published 3 March 2022

Foreword

The safety and security of the public is my number one priority. It is vital that those who keep us safe have every power and tool they need to tackle serious crime, terrorism, and hostile state activity. They represent enduring threats to this country. Battling those threats is an increasingly complex mission, not least in the light of the COVID pandemic.

The Government’s legislative response to the abhorrent attacks at Fishmongers’ Hall and in Streatham, which were both committed by a known terrorist offender, has been very robust. In April 2021, the Counter-Terrorism & Sentencing Act received Royal Assent, marking the largest overhaul of terrorist sentencing and monitoring in decades. This builds on emergency legislation passed in February 2020 that ended the automatic early release of terrorist offenders and terrorism-connected offenders serving standard determinate sentences. The Act also toughens sentences for terrorist offenders, including a 14-year minimum custodial term for the most serious offences, as well as extending licence periods. All of this is proof that this government will not hesitate to treat such offenders with the severity they deserve. Crucially, the Act also enhances the disruption and risk management tools available to operational partners, including through strengthened Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures.

We are determined to make the UK the safest place to be online and to crack down on terrorist material on the internet. The Government’s response to the Online Harms White Paper consultation sets out new expectations on companies to keep their users safe, by tackling illegal content on their platforms and protecting children from harmful material and online activity. This will be followed by legislation that will be ready this year.

COVID has been an enormous and unprecedented challenge for this country. I pay tribute to the outstanding professionalism, courage, and skill of those who work around the clock to keep the United Kingdom safe. They have not flinched. Events throughout the second half of 2021 were another reminder of the continuing threats and challenges we face. They included the terrible killing of my friend Sir David Amess MP and the explosion outside the Liverpool Women’s hospital. Our democracy and the values that we hold dear demand constant protection and vigilance. We also had to respond to the changing situation in Afghanistan very rapidly, including with security checks so that we could offer people sanctuary.

I see every day how the powers described in this report, as well as arrests, prosecutions and convictions, are essential to making us all safer. We have successfully defended the use of our disruptive powers in the courts over the last year, demonstrating that they are lawful and used only when necessary and proportionate.

Much of the work undertaken to keep the British people safe must go unseen, but the Government is committed to the maximum level of responsible transparency. This report is an important part of that commitment.

Priti Patel

Home Secretary

2 – Introduction

The priority of any Government is keeping the United Kingdom safe and secure.

Under the Government’s counter-terrorism strategy, CONTEST, we work to reduce the risk to the UK and its interests overseas from terrorism, so that people can go about their lives freely and with confidence. Drawing on lessons learned from the attacks in London and Manchester in 2017, an updated and strengthened CONTEST was published in June of 2018.

The UK continues to face numerous different and enduring terrorist threats. Despite their loss of geographic territory, Daesh retain their ability to inspire and direct attacks across the world, while Al Qa’ida remains a persistent threat. We must also continue to be vigilant of extreme right-wing terrorism.

Furthermore, serious and organised crime (SOC) is an inherently transnational security threat and continues to evolve at pace. Its impact is wide-ranging and cumulatively damaging. These criminals target vulnerable individuals, public services, and the private sector. The resulting harm to the economy, communities and citizens is extensive; SOC affects more UK citizens, more often, than any other national security threat and leads to more deaths in the UK each year than all other national security threats combined.

To counter these and other threats, it is crucial that we have the necessary powers and that they are used appropriately and proportionately. This report includes figures on the use of disruptive powers in 2020. It explains their utility and outlines the legal frameworks that ensure they can only be used when necessary and proportionate, in accordance with the statutory functions of the relevant public authorities.

There are limitations concerning how much can be said publicly about the use of certain sensitive techniques. To go into too much detail may encourage criminals and terrorists to change their behaviour in order to evade detection. However, it is extremely important that the public are confident that the security, intelligence and law enforcement agencies have the powers they need to protect the public and that these powers are used proportionately. The agencies rely on many members of the public to provide support to their work. If the public do not trust the police and security and intelligence agencies, that mistrust would result in a significant operational impact.

Unlike the previous iteration of this report - but consistent with previous years - information on MI5 investigations and the number of closed SOIs has not been included. The Government has decided to not routinely update these figures because the sensitivity of MI5’s investigative work means it is not always possible to provide the relevant context to explain any changes. Additionally, this information does not directly relate to the focus of this report, which is to provide information on the use of disruptive powers.

3 – Terrorism Arrests and Outcomes

Conviction in a court is one of the most effective tools we have to stop terrorists. The Government and operational partners are as a priority committed to pursuing convictions for terrorist offences where they have occurred. Terrorism-related arrests are made under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), under the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) in circumstances where arresting officers require additional powers of detention or need to arrest a person suspected of terrorism-related activity without a warrant. Whether to arrest someone under PACE or TACT is an operational decision to be made by the police.

Between April and December 2019, 207 persons were arrested for terrorism-related activity. Of the 207 arrests, 75 (36%) resulted in a charge, and of those charged, 61 were considered to be terrorism-related. Many of these cases are ongoing, so the number of charges resulting from the 207 arrests can be expected to rise over time. Of the 61 people charged with terrorism-related offences, 38 have been prosecuted, 19 are awaiting prosecution and 4 were not proceeded against. 37 of the prosecution cases led to individuals being convicted of an offence: 36 for terrorism-related offences and one for a non-terrorism related offence. One person was found not guilty.

As at 31 December 2019, there were 231 persons in custody in Great Britain[footnote 1] for terrorism-related offences. This total was comprised of 177 persons (77%) in custody who held Islamist extremist views, 41 (18%) who held far right-wing ideologies and a further 13 other persons.

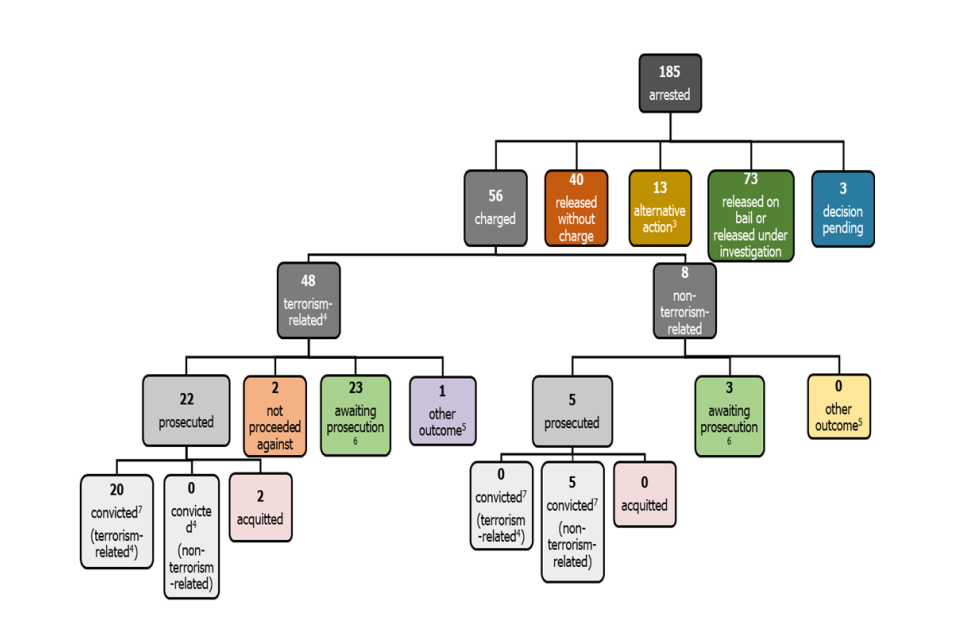

In the year ending 31 December 2020, 185 persons were arrested for terrorism-related activity, a decrease of 34% from the 282 arrests in the previous year. This was the lowest number of arrests in a year since the year ending December 2011. Of the 185 arrests, 56 (30%) resulted in a charge, and of those charged, 48 were considered to be terrorism-related. Many of these cases are ongoing, so the number of charges resulting from the 185 arrests can be expected to rise over time. Of the 48 people charged with terrorism-related offences, 22 have been prosecuted, 23 are awaiting prosecution, 2 were not proceeded against and 1 received another outcome. 20 of the prosecution cases led to individuals being convicted of an offence, all of which were for terrorism-related offences. Two people were found not guilty.

As at 31 December 2020, there were 209 persons in custody in Greater Britain for terrorism-connected offences[footnote 2]. This total was comprised of 156 persons (75%) in custody who held Islamist extremist views, 42 (20%) who held extreme right-wing ideologies and a further 11 other persons.

Terrorism arrests and outcomes are often highly reliant on the investigatory powers and tools outlined in this report.

Figure 1: Arrests and outcomes year ending 31 December 2020

Figure 1 summarises how individuals who are arrested on suspicion of terrorism-related activity are dealt with through the criminal justice system. It follows the process from the point of arrest, through to charge (or other outcomes) and prosecution.

In detail:

Of 185 arrested:

56 charged, 40 released without charge, 13 alternative action (see note 3), 73 released on bail or released under investigation, 3 decision pending.

Of the 56 charged:

48 terrorism related (see note 4), 8 non terrorism related.

Of terrorism related:

22 prosecuted, of which 20 convicted (see note 7) and 2 acquitted.

2 not proceeded against.

23 awaiting prosecution (see note 6).

1 other outcome (see note 5).

Of non terrorism related

5 prosecuted, of which 5 convicted (see note 7).

3 awaiting prosecution (see note 6)

Source: Home Office, ‘Operation of police powers under the Terrorism Act 2000 and subsequent legislation’, data tables A.01 to A.07

Figure 1 notes:

-

Based on time of arrest.

-

Data presented are based on the latest position with each case as at the date of data provision from National Counter Terrorism Police Operations Centre (NCTPOC) (14 January 2021).

-

‘Alternative action’ includes a number of outcomes, such as cautions, detentions under international arrest warrant, transfer to immigration authorities etc. See table A.03 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/operation-of-police-powers-under-the-terrorism-act-2000-quarterly-update-to-december-2020 for a complete list.

-

Terrorism-related charges and convictions include some charges and convictions under non-terrorism legislation, where the offence is considered to be terrorism-related.

-

The ‘other’ category includes other cases/outcomes such as cautions, transfers to Immigration Enforcement Agencies, the offender’s details being circulated as wanted, and extraditions.

-

Cases that are ‘awaiting prosecution’ are not yet complete. As time passes, these cases will eventually lead to a prosecution, ‘other’ outcome, or it may be decided that the individual will not be proceeded against.

-

Excludes convictions that were later quashed on appeal.

4 – Disruptive Powers

4.1 – Stops and Searches

Powers of search and seizure are vital in ensuring that the police are able to acquire evidence in the course of a criminal investigation and are powerful disruptive tools in the prevention of terrorism.

Section 47A of the Terrorism Act 2000 (TACT) enables a senior police officer to give an authorisation, specifying an area or place where they reasonably suspect that an act of terrorism will take place. Within that area and for the duration of the authorisation, a uniformed police constable may stop and search any vehicle or person for the purpose of discovering any evidence – whether or not they have a reasonable suspicion that such evidence exists – that the person is or has been concerned in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism, or that the vehicle is being used for such purposes.

The authorisation must be necessary to prevent the act of terrorism which the authorising officer reasonably suspects will occur, and it must specify the minimum area and time period considered necessary to do so. The authorising officer must inform the Secretary of State of the authorisation as soon as is practicable, and the Secretary of State must confirm it. If the Secretary of State does not confirm the authorisation, it will expire 48 hours after being made. The Secretary of State may also substitute a shorter period, or a smaller geographical area, than was specified in the original authorisation.

Until September 2017, this power had not been used in Great Britain since the threshold of authorisation was formally raised in 2011. This reflects the intention that the power should be reserved for exceptional circumstances, and the requirement that it only be used where necessary to prevent an act of terrorism that it is reasonably suspected is going to take place within a specified area and period. However, following the Parsons Green attack, on 15 September 2017, the power was authorised for the first time, by four forces: British Transport Police (BTP), City of London Police, North Yorkshire Police and West Yorkshire Police. There were a total of 128 stop and searches conducted (126 of which were conducted by BTP), which resulted in 4 arrests (all BTP).

Between April and December 2019, 480 persons were stopped and searched by the Metropolitan Police Service under section 43 of TACT (this data is not available in relation to other police forces). There were 42 resultant arrests from these 480 searches, giving an arrest rate of 9%. In the year ending 31 December 2020, 524 persons were stopped and searched by the Metropolitan Police Service under section 43 of TACT. This represents a 21% decrease from the previous year’s total of 663. Over the longer term, there has been a 50% fall in the number of stop and searches, from 1,052 in the year ending 31 December 2011. In the year ending 31 December 2020, there were 57 resultant arrests; the arrest rate of those stopped and searched under section 43 was 11%, up from 10% in the previous year.[footnote 3]

4.2 – Port and Border Controls

Schedule 7 to the Terrorism Act 2000 (Schedule 7) helps protect the public by allowing an examining police officer to stop and question and, when necessary, detain and search individuals travelling through ports, airports, international rail stations or the border area. The purpose of the questioning is to determine whether that person appears to be someone who is, or has been, involved in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism. Schedule 7 also extends to examining goods to determine whether they have been used in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism.

Prior knowledge or suspicion that someone is involved in terrorism is not required for the exercise of the Schedule 7 power. Examinations are also about talking to people in respect of whom there is no suspicion but who, for example, are travelling to and from places where terrorist activity is taking place, to determine whether those individuals are, or have been, involved in terrorism.

The Schedule 7 Code of Practice for examining officers provides guidance on the selection of individuals for examination. The most recent version of the Code, which came into effect in August 2020[footnote 4], is clear that selection of a person for examination must not be arbitrary or for discriminatory reasons and so should not be based on protected characteristics alone. When deciding whether to select a person for examination, officers will take into account considerations that relate to the threat of terrorism, including known and suspected sources of terrorism, specific patterns of travel and observation of a person’s behaviour.

When an individual is examined under Schedule 7 they are given a Public Information Leaflet, which is available in multiple languages and outlines the purpose of Schedule 7 as well as any rights and obligations relating to use of the power. No person can be examined for longer than an hour unless the examining officer has formally detained them. Any person detained under Schedule 7 is entitled to receive legal advice from a solicitor and have a named person informed of their detention. A more senior ‘review officer’ who is not directly involved in the questioning of the individual must then consider on a periodic basis whether the continued detention is necessary.

The Public Information Leaflet and Code of Practice also include relevant contact details in case a person wishes to make a complaint regarding their examination. An individual can complain about a Schedule 7 examination by writing to the Chief Officer of the police force for the area in which the examination took place. Additionally, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation is responsible for reporting each year on the operation of the Schedule 7 power.

Statistics on the operation of Schedule 7 powers are published by the Home Office on a quarterly basis[footnote 5]. In the year ending 31 December 2020, a total of 3,315 persons were examined under this power in Great Britain, a fall of 65% on the previous year. Throughout the same period, the number of detentions following examinations decreased by 43% from 2,082 in the year ending 31 December 2019 to 1,191 in the year ending 31 December 2020. The notable fall in the number of Schedule 7 person examinations and resulting detentions is consistent with the large reduction in passenger volume due to the measures being taken to respond to Covid-19 during the same period.

Of those individuals that were detained (excluding those who did not state their ethnicity), 35% categorised themselves as ‘Chinese or other’. The next most prominent ethnic groups were: ‘Asian or Asian British’ at 32% and ‘White’ at 16%. The proportion of those that categorised their ethnicity as ‘Black or Black British’ or ‘Mixed’ made up 11% and 6% respectively.

Use of Schedule 7 is informed by the current terrorist threat to the UK and intelligence underpinning the threat assessment. Whilst the impact of Covid-19 makes it more difficult to draw inferences from the current data, self-defined members of ethnic minority communities do comprise a majority of those examined under Schedule 7. However, the proportion of those examined should correlate not to the ethnic breakdown of the general population, or even the travelling population, but to the ethnic breakdown of the terrorist population In his 2018 report, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism, Jonathan Hall QC, acknowledged that Schedule 7 was not a randomly exercised power, and so whilst the majority of those examined self-define as members of ethnic minority communities, it did not automatically follow that Schedule 7 was being applied unlawfully. His report also declared he had found no reason to suggest officers were motivated by conscious bias when selecting individuals for examination following screening. Since April 2016, the Home Office has collected additional data relating to the use of Schedule 7. This data includes the number of goods examinations (sea and air freight), the number of strip searches conducted, and the number of refusals following a request by an individual to postpone questioning. In the year ending 31 December 2020, a total of 518 air freight and 2,314 sea freight examinations were conducted in Great Britain. Regarding strip searches over the same period, there were two instances carried out under Schedule 7. There were no refusals to postpone questioning (usually to enable an individual to consult a solicitor) during the same period.

4.3 – Counter-Terrorism Sanctions in the UK (formerly described as Terrorist Asset-Freezing)

As of 31 December 2020, the UK no longer applies EU sanctions regulations and all sanctions regimes are now implemented through UK regulations. The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (the Sanctions Act) provides the legal framework for the UK to impose, update and lift sanctions autonomously. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is responsible for all international sanctions and designations; and Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT) is responsible for domestic sanctions and designations.

The regulations provided under the Sanctions Act established the UK’s autonomous counter-terrorism sanctions framework, which came into force at the end of the Transition Period. The ISIL (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida (United Nations Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019[footnote 6] implement restrictive measures on those designated under the United Nations ISIL (Da’esh) & Al-Qaida 1267 Sanctions List.

The UK’s autonomous regime, through the UK Counter-Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019[footnote 7], replaces EU Common Position 931, the EU AQ/Da’esh autonomous regime, and the Terrorist Asset-Freezing Act 2010. This set of regulations relating to international counter-terrorism sanctions allows the UK to implement autonomous UK listings with an international focus related to counter-terrorism, including many that were previously made under the EU CP931 regime. The regime (along with the domestic sanctions regime) ensures the UK implements its international obligations under UN Security Council Resolution 1373.

The UK’s previous main domestic counter-terrorism sanctions legislation, the Terrorist Asset-Freezing etc. Act 2010 (TAFA), was repealed and replaced on 31 December 2020. The UK implements UNSCR 1373 obligations via two of the new counter-terrorism sanctions regimes: the Counter-Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and the Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019[footnote 8] (i.e. the domestic counter-terrorism sanctions regime).

Under the domestic sanctions regime, the HMT can designate individuals, groups or entities with a clear UK nexus (e.g. the target resides in the UK, is likely to return to the UK, holds economic resources in the UK, or where the designation will be in the interests of UK national security in a counter-terror context where UN financial sanctions are not available or deemed an appropriate tool to utilise).

Meeting these UNSCR 1373 obligations is also part of the 40 standards on anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing set out by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). FATF evaluated the UK’s compliance with its standards in 2018 and has given the UK the highest possible ratings on the UK’s system to combat terrorist financing. The full 2018 report can be found here:

https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer4/MER-United-Kingdom-2018.pdf

Financial restrictions imposed by the UK’s three new counter-terrorism sanctions regimes have the effect of freezing any funds or economic resources owned, held, or controlled by a designated person or entity. The restrictions also make it an offence for any person to make funds, financial services or economic resources available (directly or indirectly) to, or for the benefit of, a designated person or entity where that person knows, or has reasonable cause to suspect, the individual or entity is designated. Designated persons under the United Nations ISIL (Da’esh) & Al-Qaida 1267 Sanctions List and the UK Counter-Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 are also subject to an arms embargo and (for designated individuals) travel bans. Offences under the UK’s three new counter-terrorism sanctions regimes can be committed by anyone in the UK and extends to conduct by a UK national or UK-incorporated/constituted company that takes place wholly or partly outside the UK.

The UK’s autonomous counter-terrorism sanction regimes contain robust safeguards with the aim of keeping any restrictions proportionate to their purpose. Under regulation 6(1)(a) and (2) of The Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and the Counter Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, HMT or FCDO may only designate persons where they have reasonable grounds to suspect that the person is, or has been, involved in terrorist activity, or is owned, controlled (directly or indirectly) or acting on behalf of or at the direction of someone who is, or has been, involved in terrorist activity, or is a member of, or associated with, a person who is or has been so involved.

Under regulation 6(1)(b), a person may only be designated when HMT or the FCDO considers it appropriate, having regard to the purposes of the regulations (e.g. compliance with the relevant UN obligations, and otherwise furthering the prevention of terrorism in the UK or elsewhere) and the likely significant effects of the designation on the person to be designated. The requirements of both regulations 6(1)(a) and 6(1)(b) must be met for a designation to be made under The Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and the Counter Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019.

In addition, there are a number of other safeguards to ensure that the UK’s counter-terrorism

sanctions regimes operate fairly and proportionately:

-

The Home Secretary may direct that exceptions are made to travel bans on individuals.

-

HMT may grant licences authorising certain activities or types of transaction that would otherwise be prohibited by sanctions legislation.

-

In addition to issuing licences relating to a specific person, HMT may also issue general licences, which authorise otherwise prohibited activity by a particular category of persons (who fall within the licence criteria).

-

The overall objective of the licensing system for terrorism designations is to strike an appropriate balance between minimising the risk of diversion of funds to terrorism and respecting the human rights of designated persons and other third parties. HMT grants licences where there is a legitimate need for such activities or transactions to proceed. This helps to ensure that the sanctions regime remains effective, fair and proportionate in its application.

-

HMT or the Secretary of State respectively must in each review period consider each qualifying autonomous designation which has effect under the regulations they have made and decide in the case of each such designation whether to vary or revoke the designation or to take no action with respect to it. The review period as outlined in regulation 24(6) of the Sanctions Act is: (i) the period of 3 years beginning with the date when the regulations are made; and (ii) each period of 3 years that begins with the date of completion of a review. The Secretary of State and HMT may only maintain a designation where the requirements under regulations 6(1)(a) and (b) of The Counter-Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and The Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, respectively, continue to be met.

-

The appropriate Minister must without delay take such steps as are reasonably practicable to inform the designated person of the designation, variation or revocation under The Counter-Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 or The Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019.

-

Designations must generally be publicised, along with the “statement of reasons”, which is a brief statement of the matters that the appropriate Minister knows, or has reasonable grounds to suspect, in relation to the designated person which have led the appropriate Minister to make the designation. Designations can be notified on a restricted basis and not publicised when one of the conditions in regulation 8(7) of The Counter-Terrorism (International Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and The Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 is met. Those conditions are that:

the Secretary of State or the Treasury believe that the designated person is under the age of 18; or

the Secretary of State or the Treasury consider the disclosure of the designation should be restricted:

i) in the interests of national security or international relations;

ii) for reasons connected with the prevention or detection of serious crime in the United Kingdom or elsewhere; or

iii) in the interests of justice.

Where a designation is notified on a restricted basis, the Secretary of State and HMT can specify that people informed of the designation treat the information as confidential.

-

A designated person (or entity) may request a variation or revocation of a UK autonomous designation under Section 23 of the Sanctions Act, for instance, if they consider that they no longer satisfy the criteria for designation. The appropriate Minister must then decide whether to vary or revoke the designation or to take no action with respect to it. Section 25 of the Sanctions Act provides a right for persons designated by the UN to request that the Secretary of State uses their best endeavours to secure their removal from the relevant UN list.

-

A designated person has a right to apply to the High Court for the appropriate Minister’s decision on that request (see s.38 of SAMLA). Anyone affected by a licensing decision (including the designated person (or entity)) can challenge on judicial review grounds any licensing decisions of HMT. There is a closed material procedure available for such appeals or challenges using specially cleared advocates to protect closed material whilst ensuring a fair hearing for the affected person.

-

The Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, Jonathan Hall QC, will conduct a review of, and report on, the operation of The Counter-Terrorism (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 later this year.

There is currently £108,000 frozen across the UK’s three counter-terrorism sanctions regimes.

The following table sets out the number of natural and legal persons, entities or bodies designated under the UK’s autonomous counter-terrorism sanctions regimes as at 1 January 2021:

| ISIL (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida | Counter-Terrorism (International) | Counter-Terrorism (Domestic) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of designations (at the end of the quarter) | 351 | 44 | 1 |

| Total number of designated individuals (at the end of the quarter) | 262 | 22 | 1 |

| Total number of designated groups and entities (at the end of the quarter) | 89 | 22 | 0 |

| Total number of current confidential designations (at the end of the quarter) | N/A | 0 | 0 |

Listings

1. List of all the individuals, entities and ships that are designated or specified under regulations made under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-uk-sanctions-list

2. Consolidated list of all those subject to financial sanctions imposed by the UK:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/financial-sanctions-consolidated-list-of-targets

Further information about the UK’s autonomous counter-terrorism sanctions regimes can be found here:

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-sanctions-on-isil-daesh-and-al-qaida

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-international-counter-terrorism-sanctions

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-counter-terrorism-sanctions

4.4 – Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures

Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPIMs) allow the Home Secretary to impose a powerful range of disruptive measures on a small number of people who pose a real threat to our security but who cannot be prosecuted or, in the case of foreign nationals, deported. These measures can include overnight residence requirements (including relocation to another part of the UK), police reporting, an electronic monitoring tag, exclusion from specific places, limits on association, limits on the use of financial services, telephones and computers, and a ban on holding travel documents.

It is the Government’s assessment that, for the foreseeable future, there will remain a small number of individuals who pose a real threat to our security but who cannot be either prosecuted or deported, and there continues to be a need for powers to protect the public from the threat posed by these people.

The use of TPIMs is subject to stringent safeguards. Before the Secretary of State decides to impose a TPIM notice on an individual, she must be satisfied that five conditions are met, as set out at section 3 of the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011 (TPIM Act)[footnote 9].

The conditions are that:

a) the Secretary of State considers, on the balance of probabilities[footnote 10], that the individual is, or has been, involved in terrorism-related activity (the “relevant activity”);

b) where the individual has been subject to one or more previous TPIM orders, that some or all of the relevant activity took place since the most recent TPIM notice came into force;

c) the Secretary of State reasonably considers that it is necessary, for purposes connected with protecting members of the public from a risk of terrorism, for Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures to be imposed on the individual;

d) the Secretary of State reasonably considers that it is necessary, for purposes connected with preventing or restricting the individual’s involvement in terrorism-related activity, for the specified Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures to be imposed on the individual; and

e) the court gives permission, or the Secretary of State reasonably considers that the urgency of the case requires Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures to be imposed without obtaining such permission.

The Secretary of State must apply to the High Court for permission to impose the TPIM notice on the individual, except in cases of urgency where the notice must be immediately referred to the court for confirmation.

All individuals upon whom a TPIM notice is imposed are automatically entitled to a review hearing at the High Court relating to the decision to impose the notice and the individual measures in the notice. They may appeal against any decisions made subsequent to the imposition of the notice, i.e. a refusal of a request to vary a measure, a variation of a measure without their consent, or the revival or extension of their TPIM notice. The Secretary of State must keep under review the necessity and proportionality of the TPIM notice and specified measures during the period that the notice is in force.

The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 enhanced the powers available in the TPIM Act, including introducing the ability to relocate a TPIM subject elsewhere in the UK (up to a maximum of 200 miles from their normal residence, unless the TPIM subject agrees otherwise) and a power to require a subject to attend meetings as part of their ongoing management, such as with the probation service or Jobcentre Plus staff[footnote 11].

The Counter-Terrorism and Sentencing Act 2021[footnote 12], which received Royal Assent on 29 April, made further amendments to the TPIM Act. These amendments have been made to strengthen TPIMs as a risk management tool and support a more efficient operation of the TPIM regime.

The Counter-Terrorism and Sentencing Act 2021 (section 41) also amends the TPIM Act (section 20) to require the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation to review and report on the operation of the TPIM Act annually for a period for five years beginning with 2022. The Home Secretary must make the Reviewer’s report available to Parliament.

Under the TPIM Act the Secretary of State is required to report to Parliament, as soon as reasonably practicable after the end of every relevant three month period, on the exercise of her TPIM powers. Copies of all the Written Ministerial Statements, which detail the number of cases per quarter, can be found by searching https://hansard.parliament.uk/

The total number of individuals who have been served a TPIM Notice since the TPIM Act 2011 received Royal Assent up to 31 December 2020 is 24.

4.5 – Royal Prerogative

The Royal Prerogative is a residual power of the Crown which is used widely across Government in a number of different contexts. Secretaries of State exercise a range of prerogative powers and the courts have upheld the legitimacy of prerogative powers that are not based in primary legislation.

A passport remains the property of the Crown at all times. HM Passport Office issues or refuses passports under the Royal Prerogative and there are a number of grounds for withdrawal or refusal. The Home Secretary has the discretion, under the Royal Prerogative, to refuse to issue or to withdraw a British passport on public interest grounds. This criterion supports the use of the Royal Prerogative in national security cases. The Royal Prerogative is therefore an important tool to disrupt individuals who seek to travel on a British passport to engage in terrorism-related activity and who would return to the UK with enhanced capabilities to do the public harm.

On 25 April 2013, the Government redefined the public interest criteria to refuse or withdraw a passport in a Written Ministerial Statement to Parliament[footnote 13].

The policy allows passports to be withdrawn, or refused, where the Home Secretary is satisfied that it is in the public interest to do so. This may be the case for:

“A person whose past, present or proposed activities, actual or suspected, are believed by the Home Secretary to be so undesirable that the grant or continued enjoyment of passport facilities is contrary to the public interest.” (Written Ministerial Statement to Parliament 25 April 2013)

The application of discretion by the Home Secretary will primarily focus on preventing overseas travel, but there may be cases in which the Home Secretary believes that the past, present or proposed activities (actual or suspected) of the applicant or passport holder should prevent their enjoyment of a passport facility whether or not overseas travel is a critical factor.

Under the public interest criterion, in relation to national security, the Royal Prerogative was exercised to deny access to British passport facilities three times in 2019 and twice in 2020.

An individual may ask for a review of any decision to deny access to passport facilities or apply for a new passport at any time (prompting a review of the decision). In addition, if significant new information comes to light a case review may be triggered. In 2019, there were 11 reviews undertaken, which led to eight individuals having their passport facilities restored. In 2020, there were four reviews undertaken which led to all four individuals having their passport facilities restored.

4.6 – Seizure and Temporary Retention of Travel Documents

Schedule 1 to the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 enables police officers at ports to seize and temporarily retain travel documents to disrupt immediate travel, when they reasonably suspect that a person intends to travel to engage in terrorism-related activity outside the UK.

The temporary seizure of travel documents provides the authorities with time to investigate an individual further and consider taking longer term disruptive action such as prosecution, exercising the Royal Prerogative to withdraw or refuse to issue a British passport, or making a person subject to a TPIM order.

Travel documents can only be retained for up to 14 days while investigations take place. The police may apply to the courts to extend the retention period but this must not exceed 30 days in total.

In 2019 the power was exercised only once and the travel document was retained beyond the 14-day period. The power was not used in 2020.

4.7 – Exclusions

The Secretary of State (usually the Home Secretary) may decide to exclude a person if he or she considers that the person’s presence in the UK would not be conducive to the public good. If a decision to exclude is taken it must be reasonable, consistent and proportionate based on the evidence available. Exclusion is normally used in circumstances involving national security, unacceptable behaviour (such as extremism), international relations or foreign policy, and serious and organised crime. Until 31 December 2020, European Economic Area (EEA) nationals and their family members could be excluded from the UK in accordance with the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016 on the grounds of public policy or public security, if they were considered to pose a genuine, present and sufficiently serious threat affecting one of the fundamental interests of society. From 1 January 2021, the threshold for exclusion of EEA nationals will depend on their status and whether or not their rights are protected under the Withdrawal Agreement.

The number of individuals excluded in 2019 is as follows:

-

8 on the basis of unacceptable behaviour;

-

26 on national security grounds;

-

2 on criminality grounds; and

-

1 on the basis of international crimes.

In 2020 the following number of individuals were excluded:

-

6 on the basis of unacceptable behaviour;

-

14 on national security grounds; and

-

3 on criminality grounds.

The Secretary of State uses the exclusion power when justified and based on all available evidence. In all matters, the Secretary of State must act reasonably, proportionately and consistently. The power to exclude an individual from the UK is very serious and the Government does not use it lightly. This power can be used to prevent the travel or return to the UK of foreign nationals suspected of taking part in terrorist related activity in Syria due to the threat they would pose to public security.

4.8 – Temporary Exclusion Orders

The Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 introduced Temporary Exclusion Orders (TEOs). This is a statutory power which allows the Secretary of State (usually the Home Secretary) to disrupt and control the return to the UK of a British citizen who has been involved in terrorism-related activity outside of the UK. The tool is important in helping to protect the public from any risk posed by individuals involved in terrorism-related activity abroad, including those who travelled to Syria and Iraq.

A TEO makes it unlawful for the subject to return to the UK without engaging with the UK authorities. It is implemented by withdrawing the TEO subject’s travel documents ensuring that when individuals do return, it is in a manner which the UK Government controls. The subject of a TEO commits an offence if, without reasonable excuse, he or she re-enters the UK not in accordance with the terms of the order.

A TEO also allows for certain obligations to be imposed once the individual returns to the UK and during the validity of the order. These might include reporting to a police station, notifying the police of any change of address, or attending appointments such as a de-radicalisation programme. The subject of a TEO also commits an offence if, without reasonable excuse, he or she breaches any of the conditions imposed.

There are two stages of judicial oversight for TEOs. The first is a court permission stage before a TEO is imposed by the Secretary of State. The second is an optional statutory review of the decision to impose a TEO and any in-country obligations after the individual has returned to the UK.

In 2019, the TEO power was used six (6) times on a total of 4 subjects (2 males, 2 females). One individual was subject to three TEOs, the earlier two TEOs being revoked.

Of the four TEOs imposed in 2019, two returned in 2019 (1 male, 1 female) and one returned in 2020 (female).

One TEO was imposed on a male subject in 2020. The subject returned to the UK in 2021.

4.9 – Deprivation of British Citizenship

The British Nationality Act 1981 provides the Secretary of State with the power to deprive an individual of their British citizenship in certain circumstances. Such action paves the way for possible immigration detention, deportation or exclusion from the UK and otherwise removes an individual’s associated right of abode in the UK. The Secretary of State may deprive an individual of their British citizenship if satisfied that such action is ‘conducive to the public good’ or if the individual obtained their British citizenship by means of fraud, false representation or concealment of material fact.

When seeking to deprive a person of their British citizenship on the basis that to do so is ‘conducive to the public good’, the law requires that this action only proceeds if the individual concerned would not be left stateless (no such requirement exists in cases where the citizenship was obtained fraudulently).

The Government considers that deprivation on ‘conducive’ grounds is an appropriate response to activities such as those involving:

-

national security, including espionage and acts of terrorism directed at this country or an allied power;

-

unacceptable behaviour of the kind mentioned in the then Home Secretary’s statement of 24 August 2005 (‘glorification’ of terrorism etc)[footnote 14];

-

war crimes; and

-

serious and organised crime.

By means of the Immigration Act 2014, the Government introduced a power whereby in a small subset of ‘conducive’ cases – where the individual has been naturalised as a British citizen and acted in a manner seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the UK – the Secretary of State may deprive that person of their British citizenship, even if doing so would leave them stateless. This action may only be taken if the Secretary of State has reasonable grounds for believing that the person is able, under the law of a country outside the United Kingdom, to become a national of that country.

In practice, this power means the Secretary of State may deprive and leave a person stateless (if the vital interest test is met and they are British due to naturalising as such), if that person is able to acquire (or reacquire) the citizenship of another country and is able to avoid remaining stateless.

David Anderson QC undertook the first statutory review of the additional element of the deprivation power, as required by the Immigration Act 2014. His report was published on 21 April 2016[footnote 15]. A subsequent review has not been completed but to date the power has not been used since its introduction in July 2014.

The Government considers removal of citizenship to be a serious step, one that is not taken lightly. This is reflected by the fact that the Home Secretary personally decides whether it is conducive to the public good to deprive an individual of British citizenship.

Between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019, 27 people were deprived of British citizenship on the basis that to do so was ‘conducive to the public good’[footnote 16].

Between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2020, 10 people were deprived of British citizenship on the basis that to do so was ‘conducive to the public good’[footnote 17].

4.10 – Deportation with Assurances

Where prosecution is not possible, the deportation of foreign nationals to their country of origin may be an effective alternative means of disrupting terrorism-related activities. Where there are concerns for an individual’s safety on return, government to government assurances may be used to achieve deportation in accordance with the UK’s human rights obligations.

Deportation with Assurances (DWA) enables the UK to reduce the threat from terrorism by deporting foreign nationals who pose a risk to our national security, while still meeting our domestic and international human rights obligations. This includes Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which prohibits torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Assurances in individual cases are the result of careful and detailed discussions, endorsed at a very high level of government, with countries with which we have working bilateral relationships. We may also put in place arrangements – often including monitoring by a local human rights body – to ensure that the assurances can be independently verified. The use of DWA has been consistently upheld by the domestic and European courts.

The then Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, David Anderson QC, reviewed the legal framework of DWA and examined whether the process can be improved, including by learning from the experiences of other countries, his report was published in July 2017[footnote 18]. Mr Anderson noted that the UK had taken the lead in developing rights-compliant procedures for DWA; that future DWA proceedings were likely to take less time now that the central legal principles have been established by the highest courts; that for as long as the UK remains party to the ECHR, the provisions of the ECHR will remain binding on the UK in international law; that the key consideration in developing safety on return processes was whether compliance with assurances can be objectively verified; and that assurances could be tailored to particular categories of deportee, or to particular outcomes.

The Government published a response to Mr Anderson’s report in October 2018[footnote 19]. The Government response acknowledged Mr Anderson’s findings on the UK’s use of DWA and advised that future use of DWA would be based on responding to operational needs via a flexible, adaptable approach, with urgently negotiated agreements being made as needed. The response confirmed that DWA remained appropriate in relevant cases, and would remain one of the tools available to this Government

A total of 12 people have been removed from the UK under DWA arrangements. There have been no DWA removals since 2013 and new agreements would need to be negotiated for any future cases.

4.11 – Proscription

Proscription is a powerful tool enabling the prosecution of individuals who are members or supporters of, or are affiliated with, a terrorist organisation. It can also support other disruptive powers including prosecution for wider offences, immigration powers such as exclusion, and terrorist asset freezing. The resources of a proscribed organisation are terrorist property and are therefore liable to be seized.

Under the Terrorism Act 2000, the Home Secretary may proscribe an organisation if she believes it is concerned in terrorism. For the purposes of the Act, this means that the organisation:

- commits or participates in acts of terrorism;

- prepares for terrorism;

- promotes or encourages terrorism (including the unlawful glorification of terrorism); or

- is otherwise concerned in terrorism.

“Terrorism” as defined in the Act means the use or threat of action which: involves serious violence against a person; involves serious damage to property; endangers a person’s life (other than that of the person committing the act); creates a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or section of the public; or is designed seriously to interfere with or seriously to disrupt an electronic system. The use or threat of such action must be designed to influence the government or an international governmental organisation or to intimidate the public or a section of the public and be undertaken for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, racial or ideological cause.

If the statutory test is met, there are other factors which the Home Secretary will take into account when deciding whether or not to exercise the discretion to proscribe. These discretionary factors include:

- the nature and scale of an organisation’s activities;

- the specific threat that it poses to the UK;

- the specific threat that it poses to British nationals overseas;

- the extent of the organisation’s presence in the UK; and

- the need to support other members of the international community in the global fight against terrorism.

The proscription offences are set out in sections 11 to 13 of the Terrorism Act 2000 and were amended by the Counter Terrorism and Border Security Act 2019 by adding the offences of:

-

the reckless expression of support for a proscribed organisation; and

-

publishing an image of an article such as a flag or logo.

This means it is now a criminal offence for a person in the UK to:

-

belong, or profess to belong, to a proscribed organisation in the UK or overseas (section 11 of the Act);

-

invite support for a proscribed organisation (the support invited need not be material support, such as the provision of money or other property, and can also include moral support or approval) (section 12(1));

-

express an opinion or belief that is supportive of a proscribed organisation, reckless as to whether a person to whom the expression is directed will be encouraged to support a proscribed organisation (section 12(1A));

-

arrange, manage or assist in arranging or managing a meeting in the knowledge that the meeting is to support or further the activities of a proscribed organisation, or is to be addressed by a person who belongs or professes to belong to a proscribed organisation (section 12(2)); or to address a meeting if the purpose of the address is to encourage support for, or further the activities of, a proscribed organisation (section 12(3));

-

wear clothing or carry or display articles in public in such a way or in such circumstances as to arouse reasonable suspicion that the individual is a member or supporter of a proscribed organisation (section 13); and

-

publish an image of an item of clothing or other article, such as a flag or logo, in the same circumstances (section 13(1A)).

The penalties for proscription offences under sections 11 and 12 are currently a maximum of 10 years in prison and/or a fine. The maximum sentence will increase to 14 years following commencement of changes recently made by the Counter Terrorism and Sentencing Act 2021. The maximum penalty for a section 13 offence is six months in prison and/or a fine not exceeding £5,000.

Under the Terrorism Act 2000, a proscribed organisation, or any other person affected by a proscription, may submit a written application to the Home Secretary, asking that a determination be made whether a specified organisation should be removed from the list of proscribed organisations. The application must set out the grounds on which it is made. The precise requirements for an application are contained in the Proscribed Organisations (Applications for Deproscription etc) Regulations 2006 (SI 2006/2299).

The Home Secretary is required to determine a deproscription application within 90 days from the day after it is received. If the deproscription application is refused, the applicant may appeal to the Proscribed Organisations Appeals Commission (POAC). POAC will allow an appeal if it considers that the decision to refuse deproscription was flawed, applying judicial review principles. Either party can seek leave to appeal POAC’s decision at the Court of Appeal.

If the Home Secretary agrees to deproscribe the organisation, she will lay a draft order before Parliament removing the organisation from the list of proscribed organisations. Alternatively, if POAC allows an appeal it may make an order for the organisation to be removed from the list of proscribed organisations.

Under the same legislation proscription decisions in relation to Northern Ireland are a matter for the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, including deproscription applications for Northern Ireland groups.

Since 2000, the following four groups have been deproscribed;

- the Mujaheddin e Khalq (MeK) also known as the People’s Mujaheddin of Iran (PMOI) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in June 2008 as a result of judgments of POAC and the Court of Appeal;

- the International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in March 2016 following receipt of an application to deproscribe the organisation; and

- Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin (HIG) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in December 2017 following receipt of an application to deproscribe the organisation.

- Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) was removed from the list of proscribed groups in November 2019 following receipt of an application to deproscribe the organisation.

There is currently 76[footnote 20] terrorist organisations proscribed under the Terrorism Act 2000. In addition, there are 14 organisations in Northern Ireland that were proscribed under previous legislation. Information about these groups’ aims is given to Parliament at the time that they are proscribed and is available on GOV.UK.

In July 2020 the extreme right-wing terror group Feuerkrieg Division was proscribed.

4.12 – Tackling Online Terrorist Content

The open internet is a powerful tool which terrorists exploit to radicalise and recruit individuals, and to incite and provide information to enable terrorist attacks. Terrorist groups and individual actors make extensive use of the internet to spread their messages and continue to diversify their approach, using a broad range of platforms to host and disseminate content. Our objective is to ensure that there are no safe spaces online for all forms of terrorists to promote or share their extreme views.

In order to counter the online threat effectively, a coordinated and multi-sector approach is vital. This means collaborating with law enforcement, tech companies, our international partners as well as with civil society working to counter extremist ideologies and supporting people in communities already working to reject those narratives.

The UK’s dedicated police-led Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU) refers content that they assess as contravening UK terrorism legislation to tech companies. If tech companies agree that it breaches their policies they remove the content voluntarily. Since its inception in February 2010, the CTIRU has secured the removal of over 314,500 pieces of terrorist content. The Europol Internet Referral Unit replicates this model at a European level and services all Member States.

However, this Government has been clear that tech companies should not rely on referrals from law enforcement or the public, but instead should invest, where possible, in automated technology to more quickly detect and remove terrorist content from their platforms. Given the pace at which terrorist content can disperse across the internet, it is critical that tech companies adopt a coordinated approach to tackling the online threat. This is why the work of the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) - an international, industry-led forum to tackle terrorist use of the internet - is so important. The UK Government sits on the GIFCT’s Independent Advisory Committee alongside colleagues from civil society, other governments and international organisations; we also co-chair the GIFCT’s Technical Approaches working group and participate in the Crisis Response working group. Through our participation, we will continue to support the GIFCT to lead a robust response to terrorist use of the internet.

We also work bilaterally with tech companies to help prevent their platforms from being exploited to disseminate terrorist content and activity, through regular engagement and by responding to terrorist attacks where there is an online element. Where a terrorist attack occurs in the UK with an online element (for example, an attacker livestreams their attack or a proscribed group disseminates related propaganda), we will enact our crisis response protocol. This involves working closely with the CTIRU, affected tech companies, and the GIFCT where relevant, to remove terrorist content related to the attack. We enacted our crisis response protocol twice in 2020 – following the attacks in Streatham and Reading.

Following the Christchurch attack in New Zealand, in September 2019 the Government announced that the Home Office would be providing funding for a new project to support efforts to develop technology that can automatically identify online videos which have been altered to avoid existing detection methods. Following an open competition, two suppliers were selected to develop two proofs of concept, which were completed in early 2020 and achieved very high accuracy rates.

We strongly support the commitments and goals of the 2019 Christchurch Call to Action. During 2020, the UK Government took part in a Christchurch Call Community Consultation, through which the governments of France and New Zealand sought to understand how supporters of the Call are implementing the commitments made in May 2019, as well as to inform decision-making around the future areas of focus. The consultation report was published in April 2021 and can be found here: christchurch-call-community-consultation-report.pdf (christchurchcall.com).

Online Safety Legislation

On the 15th December 2020 the Government published the Full Government Response to the Online Harms White Paper consultation. This sets out the new expectations on companies to keep their users safe, including that companies must tackle illegal content on their platforms and protect children from harmful content and activity online. The Full Government Response will be followed by legislation, which we are working on at pace, and will be ready this year. The new regulatory framework will establish a duty of care on companies to improve the safety of their users online, overseen and enforced by an independent regulator.

The regulator will also be given an express power in legislation to require a company to use automated technology to identify and remove illegal terrorist content from their public channels. This power will be used where this is the only effective and proportionate and necessary action available and will be subject to strict safeguards including the accuracy of the tools, prevalence of illegal terrorist activity on the public channels of a service and the regulator being clear that other measures could not be equally effective. The Government will continue to support companies that choose to use technology to identify online terrorist content and activity on a voluntary basis once online harms legislation is in force, where the use is appropriate and proportionate.

The Full Government Response was accompanied by the interim code of practice on terrorist content and activity online, published by the Home Office. The interim code of practice will help to bridge the gap between Government’s response to the Online Harms White Paper, and the establishment of the independent regulator. The interim code is principles-based and contains examples of good practice companies may wish to undertake when implementing the code. This will enable companies to take swift action in tackling terrorist content and activity online. The Government will work with industry stakeholders to review the implementation of the interim codes so that lessons can be learned and shared with Ofcom, to inform the development of their substantive codes.

4.13 – Tackling Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

The Government is undertaking a significant programme of work to enhance the UK’s response to online child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA).

Following the Online Harms White Paper in April 2019, the government published an initial response to the consultation on the White Paper in February 2020 and a full government response in December 2020. The full government response sets out the new duties on companies to keep their users safe online, which includes taking robust action to prevent and tackle online child sexual exploitation and abuse.

Alongside the full government response, we published an Interim Code of Practice on online. This sets out measures that companies are encouraged to take to tackle CSEA, ahead of legislation coming into force. This interim code was developed in consultation with industry and civil society.

Collaborative working between Police forces and the NCA is estimated to be resulting in on average approximately 850 arrests each month for online CSEA offences, and the safeguarding or protecting of over 1000 children each month.

Starting with an initial investment of £7 million in the financial year 2020/21, the Government’s five-year Child Abuse Image Database (CAID) Transformation programme will help law enforcement to manage the scale of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) by further enhancing the CAID system, enriching data and allowing greater sharing of data and capabilities. This will help law enforcement to identify and safeguard more victims and survivors, and to identify and bring more offenders to justice. It will also better support officers’ wellbeing.

Internet users in the UK, including members of the public, who find illegal images of child sexual abuse are able to report them to the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF). The web pages containing such images can be blocked by Internet Service Providers (ISPs). The IWF is an independent organisation that acts as the UK hotline for the reporting of CSEA criminal content online. The purpose of the IWF is to minimise the availability of child sexual abuse images hosted anywhere in the world and non-photographic child sexual abuse images hosted in the UK.

The IWF has authority to hold and analyse this content through agreement with the Crown Prosecution Service and the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) - now the National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC). In 2020, IWF analysts processed[footnote 21] 299,600 reports, which include tip offs from members of the public. This is up from 260,400 reports in 2019 - an increase of 15%. Of these reports, 153,350 were confirmed as containing images and/or videos of children being sexually abused. This compares to 132,700 in 2019 - an increase of 16%. If the site hosting the image is hosted in the UK, the IWF will pass the details to law enforcement (the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Command of the National Crime Agency or local police forces) and the website host will be asked to take down the webpage.

If outside the UK, the IWF will alert the hotline in the relevant country to enable them to work with law enforcement in that country to take down the webpage. In countries where a hotline does not exist, this liaison is carried out via INTERPOL. Although the IWF is not part of Government, the Home Office maintains regular contact with the organisation, and Ministerial responsibility for policy relating to online child sexual exploitation and abuse. The responsibility for the legislation in respect of illegal indecent imagery of children and sexual contact with a child online sits with the Ministry of Justice.

5 – Serious Organised Crime Arrests and Outcomes

The National Crime Agency (NCA) is responsible for leading and coordinating the fight against serious and organised crime affecting the UK.

The NCA published its latest Annual Report and Accounts on 21 July 2020[footnote 22]. This report explains the NCA’s response to the threat we face from serious and organised crime between 1 April 2019 - 31 March 2020. An outline of this activity is below.

It should be noted that these figures provide only an indication of the response to serious and organised crime. The NCA is focused on the disruptive impact of its activities against priority threats and high priority criminals and vulnerabilities, rather than simply numbers of arrests or volumes of seizures. Furthermore, the UK’s overall effort to tackle serious and organised crime also involves a wide range of other public authorities, including police forces, Immigration Enforcement, Border Force and HM Revenue and Customs.

Arrests and Convictions

A significant part of the NCA’s activity to disrupt serious and organised crime is to investigate those responsible in order that they can be prosecuted. In the period from 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020, over 1,000 individuals were arrested in the UK, and over 600 abroad, by NCA officers, or by law enforcement partners working on NCA-tasked operations and projects. In the same period, there were 376 convictions in relation to NCA casework in the UK and 2,507 disruptions (34% increase on the total for 2018-19). Disruptions, in this context, refers to the impact of law enforcement activity against serious organised crime.

Interdictions

Between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019, activity by the NCA resulted in the seizure of more than 129 tonnes of cocaine and 2.5 tonnes of heroin. In addition, during this period NCA activity resulted in the seizure of 685 firearms within the UK and abroad. 263 of these were seized within the UK alone, more than double the total in 2018-19.

Criminal Finances[footnote 23]

In the period from 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020, the NCA recovered assets worth £23.2 million (Forfeitures £9.0m, Civil Recovery receipts £8.9m, Confiscation receipts £5.3m). In addition, the agency denied assets of £436.4 million. Asset denial activity included cash seizures, restrained assets and frozen assets (AFO £146.1m, Listed Assets £4.9m, Cash Seizures £9.0m, Civil Freezing orders (IFO, PFO, TFO) £131.5m, Restraint Orders £144.9m).

Child Protection

In 2019/2020, 69% of the 7,212 arrests made by law enforcement agencies against online CSAE stemmed from triaged NCA intelligence. The NCA also took assertive action against those who seek to abuse children, including through the viewing of indecent images, and arrested 192 of the most heinous CSAE offenders.

Child protection is when action is taken to ensure the safety of a child, such as taking them out of a harmful environment. Child safeguarding is a broader term including working with children in their current environment, such as working with a school or referring a child for counselling. As with terrorism arrests and convictions, serious and organised crime outcomes such as those outlined above are often highly reliant on the investigative powers outlined in this report.

Future publications

Under the Crime and Courts Act 2013 the NCA is required to publish an Annual Report and Accounts, which is the primary source of the information on serious and organised crime disruptions contained in the Transparency Report. Future publications of the Report will not include data on serious organised crime arrests and outcomes (or data on tackling online child sexual exploitation and abuse) because this is already routinely published by the NCA. The activity summarised in this report for 2019/20 is typical of the disruption that the NCA makes to serious organised crime. However the 2020/21 annual report by the NCA, which is available at Annual Report and Accounts 2020-21 (nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk), details the more recent success of Operation Venetic and a range of other NCA operational activity.

6 – Litigation Safeguards

6.1 – Closed Material Procedure

The Justice and Security Act 2013 introduced a statutory closed material procedure (CMP), which allows for sensitive material, i.e. material the disclosure of which would be damaging to national security, to be examined in civil court proceedings in senior courts across the UK [footnote 24]. CMPs ensure that government departments, the UK Intelligence Community, law enforcement bodies and any other party to proceedings have the opportunity to properly defend themselves or bring proceedings in the civil court, where sensitive national security material is considered by the court to be involved. CMPs allow the courts to scrutinise matters that were previously not heard because disclosing the relevant material publicly would have damaged national security.

A declaration permitting closed material applications is an “in principle” decision made by the court about whether a CMP should be available in the relevant case. This decision is normally based on an application from a party to the proceedings, usually a Secretary of State. However, the court can also make a declaration of its own motion.

Where a Secretary of State makes the application, the court must first satisfy itself that the Secretary of State has considered making, or advising another person to make, an application for public interest immunity in relation to the material. The court must also be satisfied that material would otherwise have to be disclosed which would damage national security and that closed proceedings would be in the interests of the fair and effective administration of justice. Should the court be satisfied that the above criteria are met a declaration may be made. During this part of proceedings, a Special Advocate may be appointed to act in the interests of parties excluded from proceedings.

Once a declaration is made, the Act requires that the decision to proceed with a CMP is kept under review, and the CMP may be revoked by a judge at any stage of proceedings, if it is no longer in the interests of the fair and effective administration of justice.

A further hearing, following a declaration, determines which parts of the case should be dealt with in closed proceedings and which should be released into open proceedings. The test being considered here remains whether the disclosure of such material would damage national security.

Section 12 of the Act requires the Secretary of State to prepare (and lay before Parliament) an annual report on the use of CMP under the Act. The reports are published on GOV.UK[footnote 25]. In summary, in the first seven years of operation, between 25 June 2013 and 24 June 2020, there were:

-

June 2013 to June 2014 – 5 Applications made, 2 Declarations made.

-

June 2014 to June 2015 – 11 Applications made, 5 Declarations made.

-

June 2015 to June 2016 – 12 Applications made, 7 Declarations made.

-

June 2016 to June 2017 – 13 Applications made, 14 Declarations made.

-

June 2017 to June 2018 – 13 Applications made, 5 Declarations made.

-

June 2018 to June 2019 – 4 Applications made, 7 Declarations made.

-

June 2019 to June 2020 – 6 Applications made, 4 Declarations made.

Section 13 of the Act contains a requirement to review the first five years of operation of CMPs. The review must cover the period from 25 June 2013 to 24 June 2018. On 25 February 2021, the Lord Chancellor announced the appointment of an Independent Reviewer, Sir Duncan Ouseley. In accordance with sections 13(4)-13(6) of the Act, once the review is completed, the reviewer must send a report on the outcome of the review to the Justice Secretary. A copy of it must then be laid before Parliament, excluding any part of the report that would be damaging to the interests of national security. It is expected that the review will conclude in the spring of 2022. More information on the review can be found on GOV.UK[footnote 26].

7 – Oversight

The activities of the UK intelligence and security agencies (SIS, GCHQ and MI5) are governed by robust legal frameworks and oversight arrangements. Within HMG, there are internal oversight mechanisms such as the Home Secretary’s statutory responsibilities to oversee MI5, as well as the independent oversight provided by various judicial and parliamentary bodies. Further information on Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation (IRTL) and the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) is provided below given their particular relevance to this report.

For further information on other oversight bodies such as the Office of the Biometrics Commissioner, Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC), and the Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office (IPCO) please see their public websites.

7.1 – The Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation

The current IRTL, Jonathan Hall QC, took up his appointment on 23 May 2019. The IRTL is appointed by the Home Secretary through open competition in accordance with the Governance Code on Public Appointments.

The role of the IRTL is to keep under review the operation of a range of UK counter-terrorism legislation to ensure that it is effective, fair and proportionate. This helps to provide transparency, inform public and political debate, and maintain public and Parliamentary confidence in the exercise of counter-terrorism powers, by providing independent and ongoing oversight of UK terrorism legislation as the legislative landscape and the threat from terrorism changes.

The IRTL is required by section 36 of the Terrorism Act 2006 (TACT 2006) to report annually on the operation of Part 1 of that Act and the Terrorism Act 2000[footnote 27]. Beyond this, he has discretion to set his work programme and can also review a range of other Acts depending on where he feels he should focus his attention, or if requested to do so by the Home Secretary or the Economic Secretary. The full remit of the IRTL includes:

- Terrorism Act 2000;

- Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (Part 1, and Part 2 in so far as it relates to counter-terrorism);

- Part 1 of the TACT 2006;

- Counter-Terrorism Act 2008;

- Terrorist Asset-Freezing etc Act 2010;

- Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011;

- Part 1 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015; and

- Regulations made under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 with a counter-terrorism purpose.

The IRTL’s reports are presented to the Secretary of State, who is required to lay them before Parliament and publish them. The Government also routinely publishes a formal response to each report. To allow the IRTL to perform his duties he is security cleared and has access the most sensitive information and Government staff relating to counter-terrorism.

The IRTL’s reports on TACT 2000 and part 1 of TACT 2006 may cover the following:

- the definition of terrorism;

- proscribed organisations;

- terrorist property;

- terrorist investigations;

- arrest and detention;

- stop and search;

-

port and border controls; and

- terrorism offences.

At the beginning of every year the IRTL is required to provide the Home Secretary with a work programme that specifies what reviews he intends to conduct in that 12 month period. The Secretary of State may also ask the IRTL to undertake other ad hoc or snapshot reviews.

7.2 – Investigatory Powers Tribunal