Defence and Security Industrial Strategy (accessible version)

Updated 26 March 2021

A strategic approach to the UK’s defence and security industrial sectors

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Defence by Command of Her Majesty.

March 2021.

© Crown copyright 2021.

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit the National Archives website.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at Official documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at SPO-DSISReview-Group@mod.gov.uk.

ISBN 978-1-5286-2496-1

CCS0321239404 03/21

Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Foreword

Our Armed Forces stand ready to defend our country and its interests. We have set out through the Integrated Review and the Defence Command Paper ‘Defence in a competitive age’ the threats we face and how the UK will rise to those challenges. We will deter and if needed defeat these threats. To do so, our forces require equipment which is state of the art. Just as we are refreshing what we require of our Armed Forces, we are reviewing the equipment they will need to face tomorrow’s threats and setting out a path for innovation for the future.

We must not only ensure that our forces have the right kit and equipment, but that we maintain capabilities onshore to produce and support critical elements for our national security, and ensure that our supply chains are sustainable and resilient. Through targeted investments we can deliver not only the right equipment but can bolster the Union, deliver on levelling up and enhance the skills and prosperity of the United Kingdom. As we invest more than £85-billion over the next four years in our defence equipment and support, we are determined to deliver not just for our Armed Forces but for the whole of the UK.

In addition to MOD and Armed Forces personnel, Defence alone already supports over 200,000 jobs directly and indirectly and tens of thousands of apprentices. Our defence and security industrial base is one of the many binding elements of our successful political union. A world class workforce is building everything from nuclear-powered submarines to advanced multi-role aircraft. We have frigates manufactured in Scotland, state-of-the-art satellites in Northern Ireland, next generation AJAX vehicles in Wales and Typhoons in England.

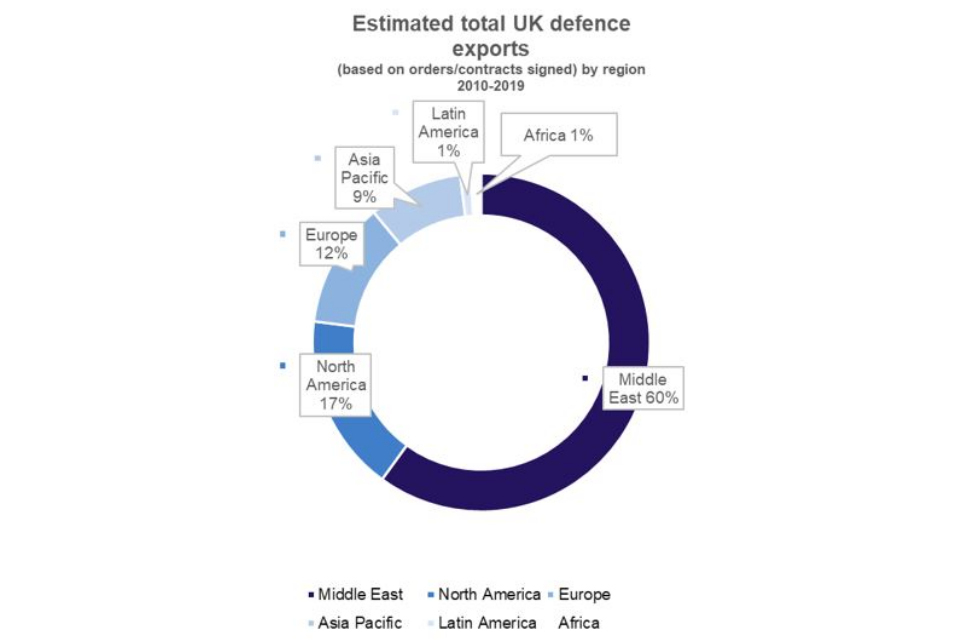

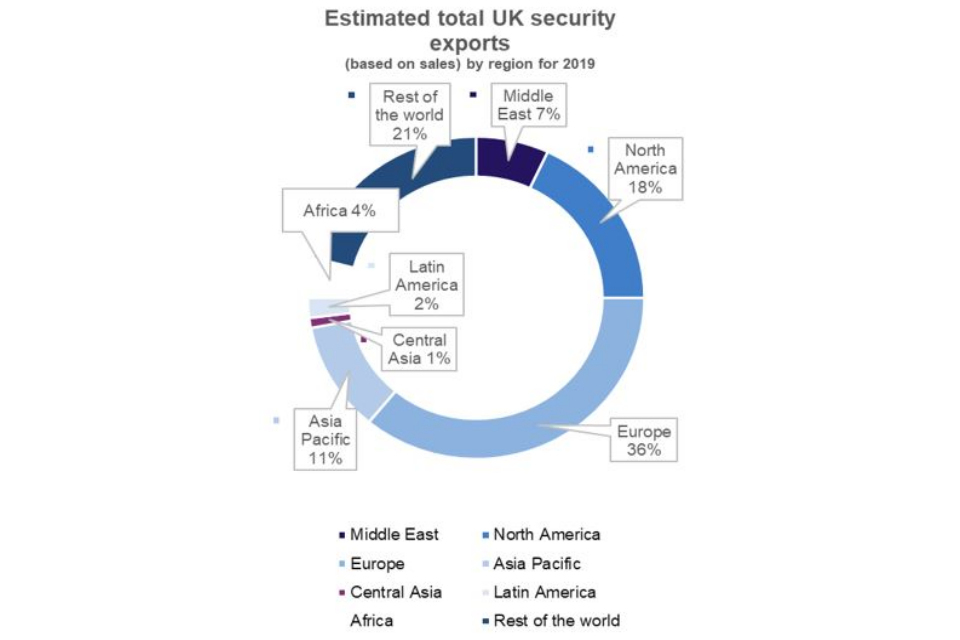

The UK is one of the largest defence exporters in the world and our industry’s products, such as the Type 26 frigate, continue to drive export success and interoperability. Our wider security industry is also a world leader in exports (ranked third globally in 2019), and a hive of innovation, driven by small and medium sized enterprises based across the Union that are targeting a wide variety of domestic and international customers.

But for Global Britain to succeed we need to make more of these great strengths. So with our partners across government we have a vision to unlock the potential of the defence and security industries to make a virtue of the immense social value they bring to our nation.

This Defence and Security Industrial Strategy will see industry, government and academia working ever closer together to drive research, enhance investment and promote innovation. We will do so while fundamentally reforming the regulations that govern defence and security procurement and single source contracts, improving the speed of acquisition and ensuring that we incentivise innovation and productivity. We will continue to build on the strong links we enjoy with strategic suppliers to ensure we retain critical capabilities onshore and can offer compelling technology for international collaborations. We will bring our allies with us on this great journey, collectively staying one step ahead of our adversaries, and building mutual resilience.

With clear priorities for our international cooperation, we will make better use of our bilateral and multilateral links with NATO and others to create capability. And we will develop new commercial mechanisms to sell our great defence and security exports to our friends and allies around the world.

This is an ambitious plan to re-energise our defence and security sectors. A plan to treat this great industrial powerhouse as a strategic capability in its own right. A plan to spread opportunity across the nation. In a post-Covid world, we’re sending out a powerful signal of Britain’s determination to build back better and stronger.

Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP, Secretary of State for Defence

Jeremy Quin MP, Minister for Defence Procurement

Executive Summary

Addressing the threat, meeting our responsibilities

As the Integrated Review sets out, the United Kingdom has a global role and global responsibilities. We are a Permanent Member of the United Nations, a leading member of the Commonwealth, a lynchpin member of NATO, and a vital contributor to wider European security, with enduring relationships to our Five Eyes partners and to our many friends and allies around the world.

As the Defence Command Paper makes clear, this global role requires us to retain Armed Forces equipped: to deter and where necessary defeat the military threats of the future; to be present and persistent; and to be agile and adaptable to the changing face of warfare and global engagement.

To do that, we need a sustainable defence industrial base to ensure that the UK has access to the most sensitive and operationally critical areas of capability for our national security, and that we maximise the economic potential of one of the most successful and innovative sectors of British industry. At the same time, and recognising the different characteristics of the wider security sector, we recognise the opportunities here to take similar approaches based on greater transparency, working together and better cross-government coordination to increase the impact of our support to the security sector too.

This Defence and Security Industrial Strategy (DSIS) aims to establish a more productive and strategic relationship between government and the defence and security industries. These critical industrial capabilities are a vital strategic asset in their own right, to which the government pays close attention to ensure we maintain our operational independence. In support of those industries, the government welcomes investment from overseas to build capacity, introduce new technology and techniques, and generate employment.

The MOD will invest a total of over £85-billion on equipment and support in the next four years. This settlement brings stability to the defence programme and provides industry with the certainty they need to plan, invest and grow. Increased investment in R&D and close collaboration with industry will allow us to experiment and bring new and emerging capabilities more rapidly into service, creating military advantage and economic opportunity.

The DSIS is part of a broader, consistent, government drive to promote both our national security in its traditional sense, and the economic growth which both underpins and depends on that security. We want to ensure that the UK continues to have competitive, innovative and world-class defence and security industries that underpin our national security, drive investment and prosperity across the Union, as well as contribute to strategic advantage through science and technology. We have a great opportunity now to set the conditions for achieving just that, as the DSIS is launched in the wider context of:

- the overall policy framework set out in the Integrated Review, setting out a fresh level of ambition for the UK, and determination to face the challenges of global systemic competition

- the additional investment of £24-billion in defence over the next four years, and the plans for that investment that have been set out in the Defence Command Paper

- wider procurement reform, taking the opportunity to modernise and update regulations

- broader government policy changes (including the revised Green Book and new social value procurement policy) to promote economic growth that is distributed more equitably across the UK

- new national security and investment legislation, increasing government’s ability to investigate and where necessary intervene in mergers, acquisitions and other types of transactions that could threaten our national security.

These changes and the policies and programmes within the DSIS itself, set out in more detail below, represent a new opportunity for UK industry to establish a ‘virtuous circle’ in which:

- the substantial injection of new funding, including at least £6.6-billion in Defence Research & Development over the next four years, directly generates growth and development of new technology, created and commercialised in the UK for strategic advantage

- companies, informed by government’s clear statements of its national security needs, plans and technology priorities, and understanding better how government evaluates industry’s offers, have the confidence to invest themselves in developing new technology, products and services and improving productivity;

- the government works more closely with industry to develop the equipment capability it needs, considers the export and international collaboration opportunities earlier, and supports industry more effectively (including where appropriate by entering government-to-government commercial agreements) to increase export market share still further, achieving economies of scale, sustaining the skills base… …beginning the cycle again by encouraging further reinvestment in R&D, skills and equipment, driving productivity and competitiveness even further.

Creating Economic Prosperity, Bolstering the Union, Levelling Up

Just as the Armed Forces serve the interests of the whole United Kingdom, the defence industry is a truly Union-wide endeavour. MOD spending secures more than 200,000 direct and indirect jobs across the UK, while the industry’s success in exports (with the UK being the world’s second largest exporter of defence products) supports many thousands more.

Defence investment bolsters the Union, levels up the United Kingdom, enhances our skills base and makes a substantial contribution to national Research and Development.

Alongside the defence sector, the UK security industry has been a success story with significant sales growth in the last decade and export earnings of £7.2-billion in 2019. Like the UK defence industry it has invested heavily in skills development offering some 3,000 apprenticeships a year[footnote 1] and is spread widely throughout the Union. The security sector though is far less concentrated (95% of it is represented by SMEs) and much less dependent on central government procurement. These different characteristics require different forms of engagement and support. The UK government will continue to support this highly competitive and innovative sector at home and in particular in helping identify and deliver on export opportunities overseas.

Industry as a strategic capability

Through the DSIS we will take a more strategic approach to industrial capability critical to our strategic and operational needs. While competition will remain an important tool to drive value for money in many areas and within supply chains, we need flexibility in our acquisition strategies to deliver and grow the onshore skills, technologies and capabilities we need, and we must ensure consistent consideration of the longer-term implications of the MOD’s procurement decisions for military capability and the industry that produces and supports it.

Therefore, we are replacing the former policy of ‘global competition by default’ with a more flexible and nuanced approach which demands that we consciously assess the markets concerned, the technology we are seeking, our national security requirements, the opportunities to work with international partners, and the prosperity opportunities, before deciding the correct approach to through-life acquisition of a given capability. This approach allows defence and security departments to use competition where appropriate, but also to establish where global competition at the prime level may be ineffective or incompatible with our national security requirements. In those situations another approach may be needed to secure the capability we need and to deliver long-term value for money, and we may for instance opt instead for long-term strategic partnerships. But in all cases, we will want to ensure that we are as transparent and inclusive as possible about our future plans and priorities.

While the DSIS sets out what we need onshore to meet our national security requirements, the UK defence and security industrial base will remain uniquely open to working with trusted allies and partners. Consistent with the HM Treasury Green Book, our defence and security procurements will take explicit account of the extent to which options contribute to well publicised social value policy priorities, and under our revised industrial participation policy we will encourage and support defence suppliers, whether headquartered here or overseas, to consider carefully what can be sourced from within the UK. But we will continue to welcome overseas-based companies and investment into the onshore industrial base, and will continue to work with international partners to co-develop and collaborate on new capability where our needs align; indeed, one of the changes inside the MOD will be to ensure that international collaborative opportunities are considered earlier and more systematically. We are also strengthening our safeguards against potential malign investment through new legislation, reassuring our partners that jointly developed technology will be protected.

In support of the government’s vision, the DSIS delivers an ambitious agenda of policy change, reform and investment, across four main areas, set out below. The annex builds on this by setting out a clearer view of our national security requirements for the key segments, including specifying those which are ‘strategic imperatives’ to be provided onshore (nuclear, crypt key and offensive cyber), and indicating where, within other segments, there are substantive capabilities we will particularly seek to maintain in this country to maintain our operational independence. Where appropriate the segmental analysis is set alongside the government’s investment decisions and plans (as per the Spending Review and detailed further in the Defence Command Paper) to illustrate in more detail some of the opportunities for industry.

Acquisition and Procurement Policy

The DSIS includes a package of legislative reform, policy changes and internal transformation that together will improve the speed and simplicity of procurement, provide more flexibility in how we procure and support capability, and stimulate innovation and technology exploitation. This package is particularly focused on MOD given its market-driving role as a customer, but it includes increasing transparency and improving communication with industry more broadly around the government’s defence and security priorities. This includes strengthening relevant government-industry groups such as the Security and Resilience Growth Partnership, the Defence Suppliers Forum and the Defence Growth Partnership.

Other elements include:

- reforming the Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations as part of the broader government review of procurement regulations, not least to improve the pace and agility of acquisition and tailor it to better enable innovation

- reforming the Single Source Contracts Regulations to simplify the regime, speed up the contracting process and introduce new ways of incentivising suppliers to innovate, take risk and support government objectives

- building on progress made by the MOD’s Acquisition and Approvals Transformation Portfolio, with a particular focus on category management, technology exploitation, cultural change and increasing the capability of the MOD’s commercial function

- publishing a fresh MOD SME Action Plan to set out how the department will maximise opportunities for SMEs to do business with the MOD

- introducing Intellectual Property (IP) strategies into the MOD’s acquisition processes for defence programmes to better incentivise and manage risk

- piloting a revised industrial participation policy for defence procurement, to promote onshore supply chain opportunities to companies bidding for MOD contracts.

Enhancing UK Productivity and Resilience

The DSIS aims to strengthen the productivity and resilience of the defence and security sectors, ensuring that the government is able to access the capabilities that it needs, whilst achieving greater prosperity for the UK through improvements in efficiency and productivity. This includes working with industry to understand the complex supply chains that underpin national security capabilities, and enhancing our ability to protect sensitive and advanced technology. Changes include:

- building greater resilience in defence supply chains in particular by mapping the MOD’s most critical supply chains and improving the reporting and management of risk across critical programmes, to ensure potential impacts on the delivery of MOD outputs are minimised

- enhancing the productivity and competitiveness of the UK’s defence sector. This includes the MOD establishing a Defence Supply Chain Development and Innovation Programme

- developing the Joint Economic Data Hub, as well as the UK Defence Solutions Centre, to make better use of analytical tools and market data

- implementing the National Security and Investment Bill which will strengthen the UK’s ability to investigate and where necessary intervene in mergers, acquisitions and other transactions that could threaten our national security

- protecting defence supply chains and sensitive technologies from malign activity by working with suppliers to establish clear, effective processes which promote security in supply chains

- working with industry to nurture and develop relevant skills in the defence and security sectors, including through sharing expertise, and outreach and communication by defence and security departments to identify and attract potential talent.

Technology and ‘pull-through’

Government, alongside industry and the defence and security sectors in particular, must understand the opportunities, implications and choices that arise from continuously evolving technological developments, and be able to access, develop and exploit new technologies at the pace of relevance to stay ahead of emerging threats. The increased investment of at least £6.6-billion in defence R&D over the next four years will enable this, and we can build on it with clearer communication between industry and government, as well as the acquisition and procurement reforms mentioned above, to encourage innovation across the Union and stimulate further private and public investment.

Relevant elements include:

- promoting greater government leadership and communication of future R&D and capability needs. The MOD will publish a new defence science and technology collaboration and engagement strategy, while the enhanced Security and Resilience Growth Partnership provides a forum for prioritised technology requirements and areas of interest from across the broader national security community to be communicated to the security industry

- developing an ambitious defence Artificial Intelligence (AI) strategy and investing in a defence AI centre to accelerate adoption of this transformative technology across the full spectrum of our capabilities and activities

- investment in Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA) challenges to identify innovative solutions to key challenges

- expanding the Defence Technology Exploitation Programme being piloted in Northern Ireland into a UK-wide initiative to support collaborative projects between SMEs and prime contractors

- supporting industry and Local Enterprise Partnerships in piloting a network of new Regional Defence and Security Clusters

- through the National Security Technology and Innovation Exchange (NSTIx), piloting a network of co-creation spaces that will bring together world-class expertise and specialist facilities from government, the private sector and leading academic communities

- with the Defence Suppliers Forum and academia, discussing what further access to government expertise, facilities and datasets industry and academia would need to access to accelerate development of new defence and security solutions.

International Cooperation, Exports and Foreign Investment

The Integrated Review described an increasingly contested and competitive global environment, in which the UK must play an active role in shaping the international order of the future and in strengthening international security. This includes cooperating with our allies and partners on the development of defence and security capabilities and associated trade and industrial issues.

Commercially however the same allies may often be supporting competitors for exports, and the DSIS also takes forward a renewed focus on delivering export success at every stage, from requirements definition to building cross-departmental packages and government-to-government commercial arrangements to deliver deals and ensure satisfied overseas customers will continue to seek the world-class products our industries can provide.

Changes include:

- establishing clear priorities for international cooperation and export opportunities for the defence and security sectors and within MOD, with clear responsibilities for ensuring adaptability and collaboration opportunities are considered early enough in the MOD capability development process

- enhancing and diversifying our international strategic partnerships, making the most of our international links for capability development and enabling industrial cooperation, including through multilateral institutions like NATO, the UK’s bilateral relationships, and groupings such as the National Technology and Industrial Base grouping with the US, Australia and Canada

- establishing a new government-to-government commercial mechanism for defence and security exports, and a renewed level of cross-departmental support for the defence and security sectors, led from the top by Ministers across MOD, the Home Office, DIT, BEIS and FCDO

- a transformation programme by the Export Control Joint Unit to improve transparency and the customer experience for exporters

- establishing a Defence and Security Faculty as part of DIT’s Export Academy, to give SMEs access to the regional, financial, and political expertise they need to maximise their chances of winning business overseas.

Context

The UK has a world-leading defence and security industrial base with a broad footprint across the UK. It underpins our national security and makes a significant contribution to the economy through jobs, skills, research and development, and exports.

The MOD alone spends around £20-billion a year with UK industry which directly and indirectly supports over 200,000 jobs[footnote 2]. The settlement for defence announced as part of Spending Review 2020 provides the MOD with additional funding of over £24-billion over the next four years, with at least £6.6-billion being spent on R&D, creating further opportunity for industry across the UK in the coming years, with modernised platforms and weapon systems across all domains. The UK’s defence and security industrial base plays a crucial role in maintaining the UK’s global influence and ultimately ensures that the UK and its allies are able to access the capabilities needed to meet rapidly changing security challenges and to keep their citizens safe.

However, over the past decade, the UK’s defence and security industrial base has been under pressure from a varied and complex set of challenges and, as a result, is at risk of losing ground to overseas competitors and potential adversaries. The most significant of these challenges include intense global competition and rapid geopolitical and technological change.

The pace of global technological change in particular is having a significant impact on the defence and security sectors. The far-reaching consequences of the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’, including the significant potential of greater automation, artificial intelligence and the importance of data in maximising capability mean that the UK’s industrial base must adapt faster, ensuring that the UK and its allies are able to maintain advantage. Government and industry need to work together to identify the technology with most potential, exploit it and deliver it to the frontline, quicker than our potential adversaries– placing a premium on our shared ability to anticipate and adapt.

Adapting to the new technological developments is important for much of UK industry if opportunities for growth are to be seized. But it is particularly pressing for these sectors on which we depend for our national security. The re-emergence of intense competition between states is driving significant investment across the spectrum of defence and security capabilities. At the same time, non-state actors can access previously inaccessible technology, experimenting and adapting it to add to their tactics. Our national security and ability to successfully prosecute military operations therefore requires an assured industrial base that can adapt to both technological opportunity and rapidly evolving threats.

The UK is well placed to meet these challenges, and there are significant opportunities for the UK’s defence and security industrial sectors in doing so. These can be best realised through a significant step change in the relationship between government and industry focused on a clear assessment of strategic needs, future priorities, and the realities of the market. As the Defence Command Paper (‘Defence in a competitive age’) notes, the government must integrate with its allies and partners, across domains and with industry to enable us to respond most effectively to the future operating environment.

The UK does not face these challenges alone. While we will compete with allies for business in the defence and security sectors just as much as elsewhere, the scale and complexity of national security capability development, and most modern defence equipment in particular, means that international partnerships and cooperation will remain essential to meet our mutual security goals.

The UK’s defence and security sector at a glance

- the MOD spent a total of £20.3-billion with UK industry and commerce in 2019/20 and will invest more than £85-billion on equipment and support in the next four years

- over 200,000 jobs across the UK are supported as either a direct or indirect result of MOD expenditure with UK industry and commerce

- the UK is the second largest exporter of defence equipment in the world (winning orders of £11-billion in 2019). For security exports, sales were £7.2-billion in 2019, putting the UK third in the world rankings

- a minimum of £6.6-billion will be invested in defence research and development over the next four years.

Our vision for the UK’s Defence and Security Industrial Sectors

It is in this context that we need a new Defence and Security Industrial Strategy (DSIS). Through this strategy, the government is determined to ensure that the UK continues to have competitive, innovative and world-class defence and security industries, that drive investment and prosperity, and which underpin our national security now and in the future.

This strategy is an opportunity to reset our relationship with industry, treating the defence and security industrial sectors as strategic capabilities in their own right. These industries not only supply the often highly sophisticated systems we need, but are crucial to our ability to continue to adapt to meet new challenges. The UK has world leading companies in these sectors and this strategy is aimed at maintaining that position, creating an environment where they can remain at the forefront of science, technology and innovation, harnessing novel and emerging technologies, to generate the cutting-edge capability we need to safeguard our national security and build strategic advantage through S&T.

Through a closer and more strategic partnership between government and industry, particularly in the capability and market segments that are most important to our national security, the government, and defence and security departments in particular, will build on these strengths and pursue new opportunities. We will sustain and grow onshore industrial capability and skills for the future in those areas most critical to defence and security, supporting economic growth across the Union and improving the competitiveness of our companies in the global market. And in strengthening UK industrial capability we will maximise the benefits of international collaboration and the potential for exports.

In doing so however, we cannot and should not attempt to actively maintain industrial capability across all markets and capability areas, and there are areas where we will continue to rely on the global market or key allies for the supply of some defence and security goods and services at both prime and subcontract level. However, this strategy lays out what will be prioritised, including those areas of industrial capability we see as strategically or operationally important in terms of our national security.

Key to realising our vision is establishing a ‘virtuous circle’, where more transparency and clarity around government’s future plans and procurement gives industry the confidence to invest in cutting-edge R&D

and innovation, leading to future technology and productivity gains. Then, through maximising the benefits of international cooperation and exports to achieve more effective capability development and economies of scale, we will sustain key skills in the UK and encourage further reinvestment in R&D, skills and equipment to drive increased productivity and enhanced competitiveness.

The government recognises that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has, in many cases across the economy, led businesses to cut back on research and development, training and other investments in future capacity and productivity. But notwithstanding this and the disproportionate impact on some linked areas of the economy including aerospace, the defence and security industries have a bright future. The UK will continue to spend over 2% of GDP on defence, is a global leader in defence exports, and before the pandemic the security industry was seeing impressive growth in revenue and exports too. By articulating where the government’s priorities are for both sectors, we anticipate that companies will be better able to plan and invest for the future.

The sectors

This strategy takes a broad view of both the defence and security sectors and the relationship between government and industry in each. Though the sectors have some significant differences between them, many of the challenges are common and the changes in this strategy will address issues and increase the future potential for both sectors.

The security sector is highly diverse and made up of a relatively large proportion of Small-to-Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs) (95%)[footnote 3] providing goods and services to many different government departments and agencies as well as a wide range of private sector customers.

By contrast, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) is often the sole customer for many defence goods produced in the UK and can restrict or prevent companies from selling military and dual-use goods elsewhere. While the MOD has thousands of suppliers for a very wide range of goods and services, many of which would not naturally be considered military capability, the MOD typically procures defence equipment from a smaller number of much larger prime contractors capable of managing the complex financial, technological and engineering demands of delivering highly complex systems, with SMEs typically engaged in their supply chains[footnote 4].

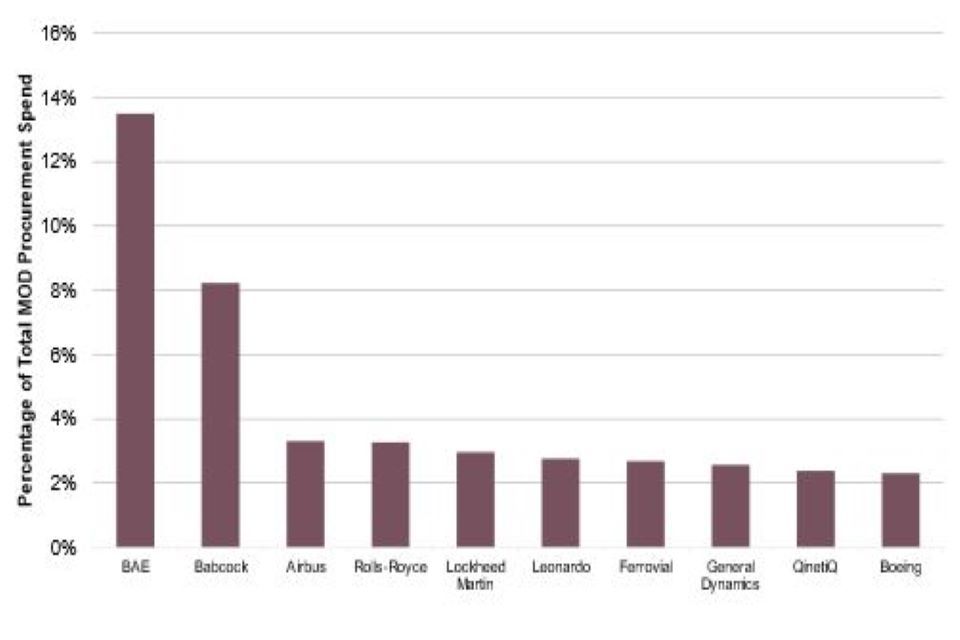

Graph showing MOD procurement spend. Figures explained in the text.

Internationally, states also frequently deviate from free market trade policies and invoke national security exemptions to restrict who can bid, and on what basis, to supply their defence equipment, often favouring national producers.

The levels of investment and access to existing intellectual property required for defence equipment, and the unusual and bespoke facilities sometimes required, can also often create high barriers to entry for new suppliers. This can make it challenging to secure value for money and encourage innovation, and can limit the scope for meaningful competition at prime level.

As a result, government policy has a far more market shaping effect on the UK’s defence industry than its security sectors. Therefore, some changes in this strategy are focused solely on the defence sector and the MOD due to its unique and market shaping relationship with the defence sector. However, despite the differences, government retains an important role as a market enabler for the security sector. Within both the defence and security sectors, there are market segments and specific capability areas which require different approaches.

Overall, this strategy sets out what those different approaches are and how the government will achieve this vision for the defence and security industrial sectors through a package of policies to revitalise the industrial base and the relationship between government and industry in these sectors.

The security sector

There is no exclusive definition of the security sector, but in this document it is taken to include critical national infrastructure protection, cyber security, policing and counter-terrorism, major event security, border security, offender management, and services including consultancy, training, guarding and risk analysis.

In the UK, around 6000 UK security companies are represented through their trade associations by RISC, the UK’s Security and Resilience Industry Suppliers Community, which was founded by the trade associations ADS, techUK, and BSIA, in co-operation with the Home Office, in 2007.

Its customer base is similarly diverse, including central government, infrastructure providers (from urban developments to critical national infrastructure, both public and private), first responders, border security, major events security and transport security. It was growing rapidly pre-COVID-19, with a 67% increase in turnover 2014-19.

To realise this vision, this strategy will drive through a range of changes to:

- foster an innovative, thriving and globally competitive UK defence and security industrial base that can provide value for money in the goods and services government buys

- ensure we can effectively acquire and maintain the defence and security capabilities that we need now and in the future

- establish a closer, more transparent working relationship between government and industry

- encourage diversity in defence and security supply chains, including by reducing barriers to entry for smaller businesses to encourage competition and innovation

- grow and improve the diversity of the people and skillsets within government and industry

- provide greater clarity on our future requirements and technology priorities which show most potential for national security application, working with industry to promote greater ‘pull through’ of these technologies into deployable national security capabilities, while contributing to the UK’s strategic advantage through S&T

- set out our approach to international cooperation on defence and security, including working collaboratively across government and with industry on: exports; developing our strategic industrial relationships with key allies and partners; and encouraging foreign investment whilst protecting and maintaining control over our most sensitive technologies.

To achieve these aims, this strategy delivers change across four main areas (discussed in more detail in the following chapters). It:

- Ensures that defence and security departments’ approaches to acquisition and procurement are effective and fit for purpose. This includes providing clarity on where onshore capability is required for reasons of national security and how best government can work with industry to sustain industrial capability across those areas. It entails moving away from a policy of ‘competition by default’ to a more flexible and nuanced approach that allows us to use competition where appropriate, or opt for strategic partnerships with industry for certain capability and technology segments, particularly where this model enhances our ability to meet our national security requirements. It includes launching reform of the regulations covering defence & security public contracts to ensure these regulations are appropriate given the current context and the pace of change we are experiencing. And it also includes taking explicit account of ‘social value’ in competitive tenders.

- Strengthens the productivity and resilience of the defence and security sectors. This includes changing the way that government and industry work together in a more sophisticated and strategic relationship, understanding the complex supply chains that underpin national security capabilities, protecting technology, and helping promote UK opportunities to overseas suppliers bidding into the UK for MOD contracts.

- Signals our requirements and where the government will make future investment in key technologies. This includes making changes to promote greater ‘pull through’ of investment in research and development into deployable national security capabilities for the future while contributing to the UK’s strategic advantage through S&T. In doing so we will seek to maintain the UK’s leading role in international capability development, whilst staying ahead of potential adversaries.

- Sets out our approach to international cooperation, exports and foreign investment. This includes establishing clear priorities for international cooperation and export opportunities, whilst adopting more of a coherent ‘TeamUK’ approach between government departments and industry in the pursuit of international success – including government being much more ready to take on responsibility for delivery through government-to-government (G2G) commercial agreements. $CTA

Defence and Security Capability and Technology Segments

Developing and maintaining military equipment and national security capabilities requires access to skills and technologies that may reside within government, in industry, or in academia. Within the defence and security sectors this is sometimes referred to as the ‘industrial and technology base’[footnote 5]. This DSIS takes a strategic view in setting out the areas of our industrial and technology base where we need to pursue different approaches to meet our most critical national security requirements. This chapter sets out our overall approach based on closer and more strategic partnerships between government and industry in the capability and market segments that are most important to us. In doing so, we categorise these segments under new headings, including specifying which are ‘strategic imperatives’ and those in which we need ‘operational independence’. A more detailed segment-by-segment breakdown is included as an annex towards the end of this strategy.

If the UK’s industrial and technology base is to continue to be successful, it must be able to adapt to the challenges of the future by continuously evolving to respond to emergent technologies, adopt smarter and more agile business practices, and provide innovative solutions to meet national security challenges. In some cases, government can have a simple transactional relationship with the industrial base, buying commodity items with a high degree of confidence that the market will provide them when needed. But the dysfunctions in global defence markets, the understandable concern of governments to control who has access to equipment capability produced in their territories and for what purpose, and the dangerous consequences of not being able to acquire and operate national security capabilities as we choose in a crisis, means that all states will consider carefully how they assure their access to those capabilities (and ensure they are not compromised or used against them by others).

There are different techniques available for capability assurance, including having excellent test & evaluation capabilities to confirm that equipment will indeed perform as intended, whether on delivery or post operational modification; stockpiling against the risk of any supply disruption; or cooperating with allies to ensure that mutual assistance can be provided in times of crisis. But many states with domestic defence industries conclude that certain industrial capabilities are so important they must be maintained onshore. Increasingly, other states that previously were happy to rely on imports now also wish to develop their own industries onshore to be able to deliver similar assurance.

The defence and security industries are a strategic capability in their own right and across the UK’s industrial and technology base there are specific industrial capability segments that are particularly important for our national security. Some of these segments require specific capability segment strategies to sustain industrial capabilities and protect operational independence, while others will require a close HMG-industry relationship to adapt to the opportunities of the future.

UK Industrial Capability Policy and Priorities

The 2012 White Paper used concepts of Operational Advantage and Freedom of Action to guide when open global competition might not apply, but the link between national security requirements and procurement strategies may not be so straightforward, and the concepts have proved difficult to apply in practice. Instead, in considering what are the industrial capability priorities to be maintained onshore, the concepts of Strategic Imperatives and Operational Independence have been applied.

Strategic imperatives

There are areas of industrial capability which are so fundamental to our national security, and/or where international law and treaties limit what we can obtain from overseas, that we must sustain the majority of the industrial capability onshore.

For instance, the ultimate guarantee of our national security is nuclear deterrence which relies on us having a credible nuclear capability to deter the most extreme threats to the UK and our Allies. As such, there can be no risk to our ability to deploy this without interference. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons prohibits nuclear weapons states from transferring nuclear weapons to other states, including other nuclear weapons states. Therefore, while we can acquire the ballistic missiles from the US, the warheads themselves must be produced in the UK. In addition, maintaining the integrity of the broader platform and system that protects it is essential: all those capabilities unique to submarines and their nuclear reactor plants need to be retained in the UK, to enable their design, development, build, support, operation and decommissioning.

More generally, the government needs to ensure that it can protect its national secrets and ensure that material marked ‘UK eyes only’ is indeed not compromised by other states. Accordingly, the UK needs to maintain a national cryptography capability. Furthermore, there is an absolute requirement to respond to the contested nature of cyberspace by developing our national Offensive Cyber capabilities. Offensive Cyber offers the UK a range of national flexible, scalable and de-escalatory measures that will help us to maintain strategic advantage. We must continue to nurture our international partnerships on cyber whilst maintaining onshore capability.

Accordingly, nuclear deterrence capabilities, submarines, cryptography and offensive cyber are strategic imperatives: there are no safe, credible and/or legal ways to meet our security needs otherwise.

Operational independence

Elsewhere, there are other areas which include particular aspects that historically we have placed a high priority on maintaining within the UK, particularly to ensure we can continue to conduct military operations as we choose without external political interference, and to protect the sensitive technologies that underpin those capabilities. Delivering this operational independence is significantly more than just ensuring delivery of ongoing contracts which might be interrupted should overseas governments object to the UK’s policy and operations; it also includes: the ability to respond to (by definition unforeseen) urgent requirements arising during operations, where systems engineering skills and design knowledge must be available; and the support of in-service equipment. Our operational independence will increasingly be shaped by our access and ability to share data with industry and across systems in consistent way, enabled by the Digital Backbone.

This operational independence is not the same as ‘procurement independence’ – or total reliance on national supply of all elements. Since the end of the Cold War, the UK has not sought to maintain a full spectrum of industrial capability onshore, and has increasingly partnered or imported, from the US in particular, where that had cost advantages and/or secured access to technology that was not available domestically. But the importance of operational independence was reflected in the previously developed strategies and partnerships for combat air, maritime, complex weapons and general munitions. Even in these narrower areas past governments did not seek to maintain procurement independence, and indeed in some areas made major investments in others’ programmes (not least F35); but these developed strategies sought to maintain onshore the most significant aspects – typically around systems integration, upgrades, manufacture of the most critical components, and testing and evaluation – to ensure operational independence. Under the DSIS, the implications for operational independence of decisions which affect industrial capabilities will be explicitly evaluated in acquisition-related decisions.

The previously mentioned MOD strategies, and analogous work across government on cyber and space, emerged due to particular pressures in those segments at different periods, but cumulatively they have underlined that the 2012 policy of global competition by default, and the application of the Technology Advantage exception, did not reflect the complexity of the factors in play in defence and security industrial strategy.

The DSIS review has been an opportunity to both review these previous ‘exceptional’ approaches but also consider how best to ensure operational independence across a much broader range of segments, including the national security industry, against a common framework. This approach took into account future requirements; industrial capability health; the current state of the global market; and, adoption of technology, as well as international and prosperity aspects.

The results have demonstrated which capability segments need more or sustained deliberate approaches across the portfolio of acquisition programmes and set Industrial Capability Priorities. These will be reviewed regularly to inform capability planning and investment processes, with departmental investment appraisal committees responsible for holding Capability Sponsors (e.g. MOD Capability Directors) to account for implementation within their portfolios of responsibility, working closely with procurement and commercial teams. In some cases, we intend, as set out in the annex, to develop further specific segment industrial strategies (for example, for air platform protection), which will be published as they mature, assuming that we have been able to work successfully with industry to develop a value-for-money proposition that delivers our objectives.

Building on the DSIS, the MOD will review its Assured Capability Policy to ensure that we continue to understand the effectiveness and vulnerabilities of technology and capabilities throughout the development, in-service life and export processes, to ensure that the UK defence and security capabilities are protected and we maintain our battle-winning edge.

Acquisition and Procurement Policy

The government’s defence and security industrial policy and our approach to acquisition will now be based on a more sophisticated consideration of our national security requirements and the reality of the markets in which we operate, rather than an assumption that global competition is always the best way to meet our needs. Therefore, as well as being clearer on our respective approaches to different capability and technology segments, we must update our overall policy towards acquisition and procurement, as well as setting out what progress national security departments are making on reform in important areas.

The 2012 White Paper ‘National Security through Technology’ set a policy of ‘global competition by default’, envisaging only rare exceptions when particular national security concerns applied, at which point single source arrangements would be used. In practice, a more nuanced approach has often been taken, with single source procurement making up a significant percentage (c.35% or some £8-billion a year) of the value of MOD contracts signed each year.

This expenditure includes the whole of MOD’s procurement (including goods and services from non-defence companies including facilities management and business services), so in practice the majority of MOD’s expenditure with the defence industry as it would generally be understood is single-source.

Graph showing MOD payments made by type of contract. Figures explained in the text.

This departure from the stated ‘default’ of global competition is partly because in many of the segments in which national security concerns are most acute (as set out in the segments annex) the systems are complex and costly and only within the scope of a very limited number of companies. Therefore, global competition is often not possible or inappropriate, as there are too few companies able to deliver projects and those projects are too infrequent to sustain domestic competition beyond the short term.

At the same time, in some other segments, even where particular national security concerns apply, global and domestic competition has remained viable at the prime contractor level. For example, many security markets function effectively and global competition continues to deliver long-term value for money, and some shipbuilding has been competed domestically in the last decade.

The need for a different approach to the 2012 policy has been previously acknowledged through some more narrowly defined defence sectoral strategies, like the National Shipbuilding and Combat Air strategies, and some broader security-related strategies (for example, the National Cyber Security Strategy, the Security Exports Strategy and the Aviation Security Strategy). Within the defence sector, other existing strategic partnerships (for example, with MBDA for complex weapons, and BAE Systems for general munitions) have endured and evolved. This DSIS pulls together these individual areas and puts them in a broader context, and updates our overall policy for these new circumstances.

Accordingly, the ‘global competition by default’ policy will now be replaced with a much more sophisticated and nuanced approach based on understanding the markets concerned, the technology we are seeking, our national security requirements, the opportunities to work with international partners and the prosperity opportunities, before deciding the correct approach to through-life acquisition of a given capability. This will mean that industrial consequences and commercial strategies will need more case-by-case consideration in future procurement decisions. However, this does not mean we cannot give industry clarity on the strategic picture. Rather than leaving the biggest decisions to individual projects, the DSIS approach includes consciously deciding and communicating now those areas of particular strategic and operational importance, where we need to sustain industrial capability onshore in the UK, as well as specifying where we will continue to reap the benefits of global competition or collaboration. These details are set out in the segments annex.

In all cases, we will of course conduct our procurements consistent with relevant international legal obligations and UK procurement regulation.

As part of this strategy, we need to promote a more collaborative approach between government and industry to improve the way that defence and security departments acquire goods and services. There is significant enthusiasm for a more strategic and collegiate relationship across both government and industry in both the defence and security sectors. There is much work already underway to improve the way that departments acquire the equipment and capabilities that they need. This is particularly true of the MOD which in recent years has launched a set of transformation and reform initiatives to improve the way it works with industry.

Through this strategy the government will build on these existing efforts to reform approaches to acquisition in defence and security departments and, in doing so, will drive change through a package of policy, process and legislative reform delivered with renewed energy and commitment from both government and industry. We will enable these changes by working with our acquisition communities to drive empowerment, collaboration, professionalisation and effective management of risks.

Through this package of change we will aim to ensure we have acquisition systems that:

- improve the speed and simplicity of procurements and upgrades, underpinned by streamlined processes and empowered teams, to reduce timescales and processes for introducing and upgrading capability

- provide more choice and flexibility in how we procure and support capabilities, in response to the needs of each capability segment and the status of the market that these segments need to access

- stimulate innovation and exploit technology through procurement to unlock value from new suppliers, increase responsiveness to technological change and enable our capabilities to remain current whilst they are in service.

Accordingly, defence and security departments will implement reform across a number of areas relating to our policies and processes around acquisition and procurement including those set out in the following pages.

Reforming the Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations and Single Source Contracts Regulations

The UK’s departure from the European Union provides an opportunity to reform the Defence and Security Public Contracts Regulations (2011) (DSPCR) which are derived from an EU Directive and control defence and sensitive security procurement in the public sector. A significant proportion of MOD’s procurement is conducted under this regime.

The MOD has embarked on an ambitious and comprehensive review of the DSPCR as part of the broader government review of procurement regulations. The Cabinet Office has published a Green Paper on Transforming Public Procurement[footnote 7] which aims to speed up and simplify procurement processes and place value for money at their heart. Through this we will improve the pace and agility of acquisition, simplify the regulatory framework, tailor it to better enable innovation and support the pull through of new technology into defence and security capability.

The Green Paper includes a proposal to rationalise and clarify the parallel rules in the Public Contracts Regulations and DSPCR (and other regulations governing competitive public procurement), replacing them all with a single uniform set of rules. This would be supplemented with defence and security sector-specific rules where these are required to protect our national security interest or our industrial base. The MOD has also been undertaking a comprehensive review of the Single Source Contract Regulations, focusing on simplifying the regime, speeding up the contracting process and introducing new ways of incentivising suppliers to innovate and support government objectives. These reforms will be designed to ensure that we have a sustainable supply base that is capable of meeting the UK’s needs in a rapidly changing world.

To do this, we will ensure that the regulations allow us to avoid paying unjustifiably low or high profit rates for single source contracts. We will also look at the range of profit rates we can pay on existing single source work to ensure that they properly reflect risk and market conditions across the breadth of what we buy. We will also ensure that we can use profit to properly incentivise suppliers to support delivery of the government priorities set out in this strategy.

The effect of these changes would mean suppliers can earn higher profits where there is a significant transfer of risk, or they achieve outstanding performance against contract deliverables or wider government priorities. Conversely the profit rate available for low risk work or less challenging performance would be lower. Using profit on single-source contracts to incentivise world-class performance and innovation will improve the sustainability and long-term competitiveness of the UK defence industry.

At the same time, we intend to reduce the administrative burden on industry by ensuring that suppliers are only required to produce the information the MOD needs, and we will be clear about what that information will be used for. We also intend to change the regulations so that they can be sensibly applied to a wider range of contracts, including introducing new ways of determining a fair price for goods or services sold in open markets. And we will adapt the regulations to cater for new contracting approaches such as co-funding research into cutting-edge technologies.

Combined, these changes would ensure that the single source regulatory framework for single-source contracts supports long term sustainability of the UK defence sector by driving high performance and innovation.

MOD will publish a Command Paper later this year setting out in more detail the policy proposals for reforming the SSCRs and the legislative and other mechanisms by which these reforms will be implemented, and are already engaging industry on this through the Defence Industry Council and the Defence Suppliers Forum.

Acquisition Transformation

The MOD will build on progress made through its Acquisition and Approvals Transformation Portfolio, whilst focusing on the following key areas:

-

Category Management: the MOD is building on the early adoption of Category Management arrangements to increase co-ordination across Defence in the acquisition of capability, goods and services. By leveraging pan-Defence expertise and demand, and by adopting a more joined-up and strategic approach to how we set requirements and leverage the market the department will drive better value for money, deliver capability quicker, and reduce duplication of effort. Through Category Management, the MOD will have more influence on the market, improving how we utilise industry by providing a unified front when dealing with key suppliers.

-

Technology Exploitation: increasing the pace and agility of the MOD’s acquisition processes to enable the effective pull-through of emergent technology and the delivery of capability while it is still technologically relevant. As part of this, the MOD is exploring ways to involve industry partners earlier in the development and procurement processes, to ensure we benefit from innovation and new technology, with greater industry involvement in the development of requirements and end specifications.

-

Cultural Change: recognising the importance of culture and behaviours within relevant departmental teams to the effective transformation of acquisition. We have already upgraded our investment decision making process, establishing an earlier decision point to better set up programmes for success. The evidence required to support approvals decisions is being made more proportionate to the risk and complexity of cases. By introducing ‘Appropriate Risk’ and ‘One Team’ approaches, we are empowering programme teams to tailor acquisition and approvals routes to reflect the level of complexity and risk of each programme, whilst also encouraging collaborative working across organisational and functional boundaries, as well as with industry, to shape programmes from an earlier stage in the acquisition process.

-

Continuing to increase the capability of the commercial function: defence and security departments have increased the capacity and capability of their commercial functions. Departments will continue to invest in the commercial expertise required to support the delivery of this strategy, for example, by ensuing our teams can assess markets in which we operate in a more sophisticated way and by continuing to develop teams capable of contracting for open systems in an agile way.

MOD-Industry Engagement

There are a variety of existing fora for engagement between MOD and industry and academia, involving other government departments including BEIS and DIT as appropriate, outside of specific commercial arrangements and partnerships. We will build on these by:

- increasing transparency and improving communication of longer-term government priorities, requirements and pipelines: identified through cross-government collaboration and the development of ‘road maps’ for the pull through of projects. As noted below, this is important for all security focused departments not just the MOD

- driving implementation of the MOD Strategic Partnering Programme (SPP): to enable greater collaboration with industry and using it to support implementation of this strategy with our strategic suppliers. The SPP aims to unlock mutual benefit, improve value to UK society, and underpin long term economic prosperity and was recognised by the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply as the “Best Supplier Relationship Initiative” in their 2020 awards

- refreshing MOD’s commitment to SMEs and reducing barriers to entry: the MOD has undertaken a wide-ranging review of its procurement practices to encourage more SME participation in defence procurement with SME spend already improving from 13.5% in Financial Year 16/17 to 19.3% in Financial Year 18/19. The MOD will publish a refreshed SME Action Plan which will set out how we will further improve access to opportunities for SMEs to do business with the department

- strengthening the Defence Suppliers Forum (DSF) as the primary MOD-industry engagement mechanism on strategic topics. We will maintain a balance of industry representation to ensure that primes, mid-tiers (who form a vital part of the defence supply-chain) and SMEs have a voice in the development of our approach to the UK defence sector. This includes the creation of a DSF SME Working Group alongside the other existing DSF groups and the SME Forum chaired by the Minister for Defence Procurement. The DSF will drive a common focus on the challenges ahead, including supporting a sustainable future for the defence industry, and its role in supporting the delivery of this strategy and the defence and security industries’ contribution to broader national economic success. To support this, we will revisit the ‘DSF vision 2025’ and its key supporting deliverables

- at the same time, and jointly with industry, the MOD will conduct a strategic review of the Defence Growth Partnership’s work on exports and economic growth, and strengthen links with other sector groups such as the Aerospace Growth Partnership, and related bodies such as the Security and Resilience Growth Partnership and Cyber Growth Partnership.

MOD-Industry Engagement

The MOD engages with UK defence suppliers through two main fora. The Defence Suppliers Forum (DSF) enables strategic engagement between Government and its suppliers to share information effectively, align objectives and optimise delivery of Defence capability from the available budget.

The DSF is co-chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence and Chief Executive BAE Systems. It has several dedicated Steering and Working groups focussing on our key joint challenges through a number of workstreams, including Commercial Enterprise and Acquisition, Capability Management International and Innovation, People and Skills, and Digital. Across its sub-groups, membership includes senior officials from MOD and other government departments and representatives from MOD’s strategic and mid-tier suppliers, as well as SMEs.

The DSF is central to delivering the improved pace and agility required for a joint approach to meeting Defence capability needs. Its work aims to create a more collaborative, but also demanding, approach to MOD’s relationship with its industry suppliers as expressed in our Joint Industry Vision 2025. DSF has collectively responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, and has been an effective engagement mechanism to ensure continuity of delivery to the MOD and cashflow to industry. A recent survey of members found that: ‘collaboration was very good’ and ‘Defence seemed to be leading the way in many areas both in supporting the response to the crisis and in its relationship with its supply chain’.

The Defence Growth Partnership (DGP) is a partnership between Government and Industry that works to grow the UK’s defence sector by strengthening its global competitiveness to achieve international success. Sponsored by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the DGP membership includes MOD, Department for International Trade, thirteen leading defence primes, and ADS, the trade association. It has established the UK Defence Solutions Centre to provide market intelligence, capability and market development, innovation and aligned investment jointly for the UK government and defence industry; designed to enable UK companies to win significant new business in export defence markets. Its government/industry “Team UK” approach seeks to appeal to international customers by offering a collaborative approach to developing capability solutions. The DGP also works to access the UK’s complete value chain and on skills initiatives in areas which support competitiveness in international markets.

Examples of government-industry security sector engagement

Aviation security

The government promotes the UK’s aviation security objectives at an international level, through multilateral bodies such as the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), and by working in partnership with industry and likeminded international partners to pursue joint approaches on priority issues. We have recently been successful in securing new ICAO Standards to address the risks from insider threat. 2021 is the ICAO Year of Security Culture, during which we will work in partnership with ICAO, the aviation industry and partner countries to deliver practical and sustainable initiatives that will result in positive change to security culture at airports around the world.

Crypt-Key

The government has used an open and evidenced based approach to identify competent companies capable of developing Crypt-Key solutions. The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) brings these companies together on a regular basis to discuss common issues, sector challenges and explore the government’s expected direction of travel and likely future requirements. Together, government and industry seek to identify improvements in working practices that meet the needs of both parties to ensure successful delivery of Crypt-Key projects. This includes the sharing of risks as appropriate, collaborative and collegiate working between teams and including industry partners as much as possible when articulating the problems that government wishes to solve. In doing so, the NCSC actively encourages innovative ideas and ways of solving problems to develop effective solutions for future Crypt-Key capabilities.

MOD commercial policy changes

The MOD is introducing Intellectual Property (IP) strategies into its acquisition processes, which will ensure that defence programmes and projects consider the costs, risks, benefits and constraints associated with different intellectual property approaches early on, when these programmes are defined. Through this, the MOD aims to secure only those rights (for example, those relating to technical data and software delivered) that are necessary to meet the operational needs of the military user and to deliver value for money.

The MOD’s commercial policy on the limitation of contractor’s liability is being updated, responding to industry concerns that too often the department has sought to put uncapped liability onto bidding companies, which they may be unable to manage, may deter competition, and which do not reflect the degree of technical risk inherent in some defence projects.

These reforms and those set out in the previous pages are wide-ranging, and their implementation will be a long-term endeavour. Improvements will be incremental as success will often rely on empowering government commercial teams to take appropriate risk and manage individual projects effectively over the long term, but within strategic guidance established early in the evolution of projects. The MOD will provide the framework, tools and support for staff to enable them to do so while enhancing their skills through training and guidance at all levels.

National security procurement by non-MOD government departments and agencies

The UK government customer base for non-military goods and services is spread across multiple departments and agencies, spanning Whitehall and the wider public sector, including independent operational partners accountable to different governance frameworks and often operating on annual budgetary cycles. It is also worth noting that customers for security related goods and services are often private entities, which is in stark contrast to the defence sector where government is often the main, and sometimes the sole, customer for defence goods.

This all makes it extremely challenging to communicate security capability requirements to industry, and there is limited coordination of procurement to stimulate industrial investment, illustrated for example by the generally independent procurement activity of each police force (notwithstanding the recent establishment of BlueLight Commercial).

The diversity of the security sector and the generally smaller companies within it can make it difficult for industry to engage comprehensively and consistently with government outside of individual competitions and consultation exercises. While there are good examples of dialogue (see boxes), these are not as consistent and formalised as is the case with the defence industry.

The Joint Security and Resilience Centre (JSaRC)

JSaRC was founded in 2016 by the Office of Security and Counter-Terrorism (OSCT) to provide security outcomes for the United Kingdom by combining government, academic and private sector expertise to meet the fast moving and ever-evolving threats to our citizens, both here and overseas. It aims to overcome the traditional barriers that have prevented collaboration between the private and public sectors by improving the understanding both sides have of each other, and of the key issues and trends that have an impact on the UK’s security and resilience.

JSaRC has a ‘threat-agnostic’ approach, championing multi-use technology that has multiple applications and encouraging specialist innovation in ideas and products to meet the possible security and resilience threats facing the UK. This results in relevant, practical and market ready solutions being offered to the public and private sector.

Case Study: BlueLight Commercial

In recent years, it has been noted that commercial services in policing are fragmented without a structured approach to procurement for policing as a whole. This has led to the 43 forces across the UK often taking different approaches and paying different prices for the same goods.

To deliver savings through a more strategic approach to procurement across police forces, BlueLight Commercial, a sector owned company, was created in 2020. This supports the delivery of a commitment made in the Policing Vision 2025 to change the way support services are delivered to ensure policing is able to meet changing demands, and delivers on expectations set out in the Police Funding Settlement. BlueLight Commercial aims to promote the use of industry best practice, including through dedicated category expertise and effective market engagement, to support forces to procure and manage contracts throughout their life-cycle and deliver savings over the long term. This includes undertaking more shared procurement to realise greater economies of scale. The first major tender exercise was launched in October 2020 to procure more than 8000 vehicles for police forces in England and Wales.

The introduction of BlueLight Commercial is not intended to centralise all commercial and procurement activity and the majority will remain locally managed. However, to drive improvements across these activities, the company is establishing a Centre of Excellence on commissioning and social value to provide advice and support to relevant staff across the policing sector on all aspects of the commercial cycle. Once fully established, BlueLight Commercial is expected to deliver annual savings of £20-million in commercial efficiencies.

Future Aviation Security Solutions (FASS)

FASS is a joint initiative between the Department for Transport (DfT) and the Home Office that works collaboratively with other government agencies and a wide range of stakeholders from airports to universities.

The FASS programme was established in 2016 with £25.5-million to invest over a five-year period in truly innovative science and technology. The programme has since been embedded into the wider work of the DfT and continues to encourage, fund, and support the development of innovative solutions to deliver a step change in aviation security.

To date, FASS has supported the creation of nine themed competitions and invested 128 projects in areas such as machine learning, passenger screening, x-ray, and vapour/trace detection.

Case Study: Security-Technology Research Innovation Grant

In 2020, FASS delivered the Department for Transport’s first Security-Technology Research and Innovation Grant (S-TRIG) programme. This scheme provided suppliers with funding to conduct short research projects to tackle some of the challenges that could arise within national security in the UK.

FASS collaborated with several government departments including counter-drones teams in the DfT and Home Office, HM Prison Service, the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI), and Border Force and delivered the programme with the support of Connected Places Catapult.

Nearly £530,000 has been awarded to 18 organisations with proposals across five areas of national security by FASS and its government partners.

Case study: Future Aviation Security Solutions Industrial PhD Partnership

The Future Aviation Security Solutions Industrial PhD Partnerships (FASS IPPs) was announced in 2019 and sought to bring academia and industry together to develop innovative ideas capable of transforming the future of aviation security.

Fourteen universities from across the UK applied to the programme and eight were awarded funding to undertake PhDs – four of which began in October 2020 with the others to follow.

The PhDs cover a range of aviation security topics and have received more than £930,000 from FASS and in-excess of £1.3-million cash and in-kind support from industry.

As security markets generally function effectively and given that government is often not the primary customer for security goods, less support and intervention is required with the security sector when compared to defence markets. However, there are still opportunities for government and industry to jointly address several issues which are common to defence and security sectors. These include:

- increased transparency and improved communication of longer-term security priorities (i.e. the ‘problems to solve’), including developing roadmaps from early research to commercialisation and exploitation, including for exports

- earlier engagement with industry on potential solutions to individual requirements

- running cross-sector innovation challenges through DASA

- reducing barriers to entry for security industry SMEs.

In order to allow for greater strategic alignment between security, industry, academia and government on these issues, the existing Security and Resilience Growth Partnership (SRGP) will be expanded further This ministerial board will provide updates on cross-government homeland security priorities and demand signals which will then be communicated to the security industry and academia. The board will set the strategic direction on this joined up approach.

The Security and Resilience Growth Partnership (SRGP)

The Security and Resilience Growth Partnership (SRGP) was established in May 2014 through the Home Office’s Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism (OSCT). It established a new government/private sector partnership approach to the innovation, promotion and delivery of UK security capabilities. As the key strategic level board for engagement with the security sector, both industry and academia, it is jointly chaired by the Minister of State for Security and the Chairman of RISC, the UK security and resilience industry suppliers’ community.