4. Pre-existing mental health conditions Spotlight

Updated 18 November 2021

Applies to England

Introduction

This Spotlight is part of a series within the COVID-19: mental health and wellbeing surveillance report.

The report is about population mental health and wellbeing in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. It includes up-to-date information to inform policy, planning and commissioning in health and social care. It is designed to assist stakeholders at national and local level, in both government and non-government sectors.

The report is regularly updated with the most recent information available and follows a standard structure to enable regular and easy use.

The Spotlight series describes variation and inequality in the population. Spotlights have also been published for age, gender and ethnicity.

This Spotlight presents intelligence on the mental health and wellbeing experience of people with pre-existing mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the collated evidence is from surveys where respondents have self-reported a pre-existing condition, but some is also based on the experience of people on mental health patient registers. Together, this includes a range of conditions, from anxiety and depression through to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

This Spotlight is composed of 2 main categories of information:

- Weekly data drawn from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study up to week 46 of 2020 (week ending 13 November).

- Analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects up to week 46 of 2020 (week ending 13 November).

The 2 categories of information have separate purposes.

Weekly data serves as an early warning system for large changes and differences between groups. It should not be used to draw conclusions about smaller changes or differences between groups from week to week. This is because the data has not been analysed to control for any confounding factors or potential biases.

The analysis from academic research offers a good picture of change over time and differences between groups. This intelligence is the basis for more nuanced interpretation and feeds into the Important findings chapter.

The latest available version of the data presented in this spotlight can be found in the Wider Impacts of COVID-19 on Health (WICH) tool.

Note:

Any deterioration of mental health captured in studies and weekly reporting should not be automatically interpreted as an increase in mental illness or need for mental health services. This is a difficult and stressful time for many, and some short-term increases in psychological distress and anxiety are to be expected.

Note:

To enable this Spotlight to be as up to date as possible, some pre-print (and therefore not yet peer reviewed) academic research is presented. Even with this approach there is still a time delay between data being gathered and findings reported.

Note:

The UCL COVID-19 Social Study focuses on the psychological and social experiences of adults living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study is not representative of the UK population but instead was designed to have good stratification across a wide range of socio-demographic factors with data weighted to the national population.

This study sample was refreshed in late August and around 16,000 participants, who had stopped submitting data routinely, re-engaged. The study also changed from weekly to monthly follow up with participants allocated to one of 4 weeks. The impact of these changes is not yet fully understood, therefore reporting of data from the point of change is indicated on the graphs. While comparisons with earlier data should be undertaken with caution, there are now more than 10 weeks of data from this revised cohort.

It is also important to note that some of the baseline levels for the UCL COVID-19 social study graphs use data from other countries and therefore may not be representative of UK pre-COVID-19 levels.

The basis for the intelligence included is presented in the Methodology document.

Main findings

There are various sources of intelligence on the physical and mental health of people with pre-existing mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, they suggest that:

-

adults with pre-existing mental health conditions are generally reporting worse levels of mental health and wellbeing than adults without pre-existing mental health conditions, but this gap has not grown over the course of the pandemic

-

the majority of respondents with mental health problems report that they are managing to cope, with a minority needing more support

-

adults with pre-existing mental health conditions appear to be at greater risk of death and hospitalisation from COVID-19 than the general population, but at lower risk than some other high-risk groups

-

one mental health trust has also reported a rise in non-COVID-19 related deaths among people who are, or have been in contact with their services, relative to the same period last year

-

while many adults are still accessing mental health services, there is some evidence of a shift from face-to-face to virtual care

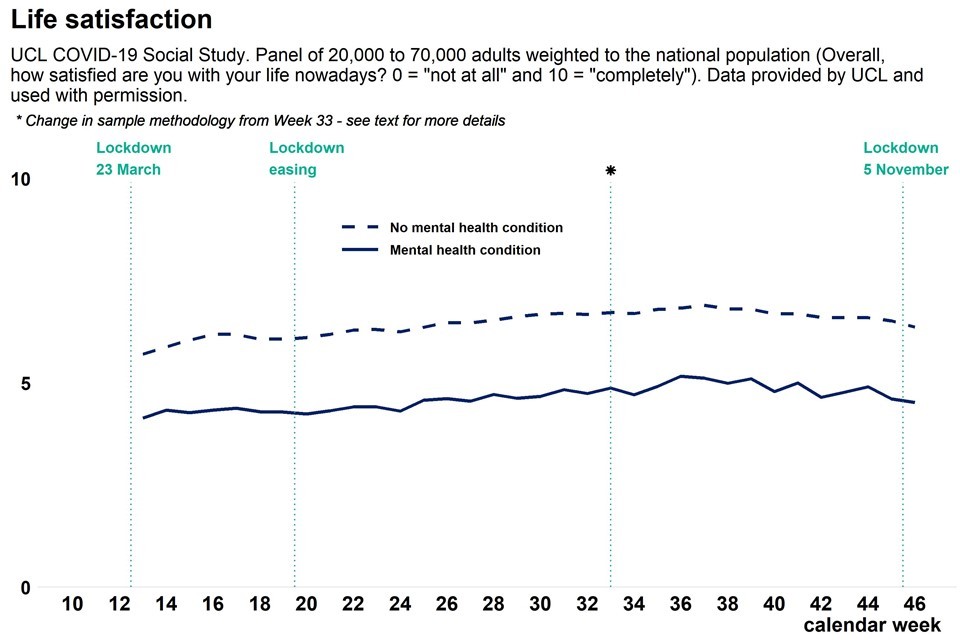

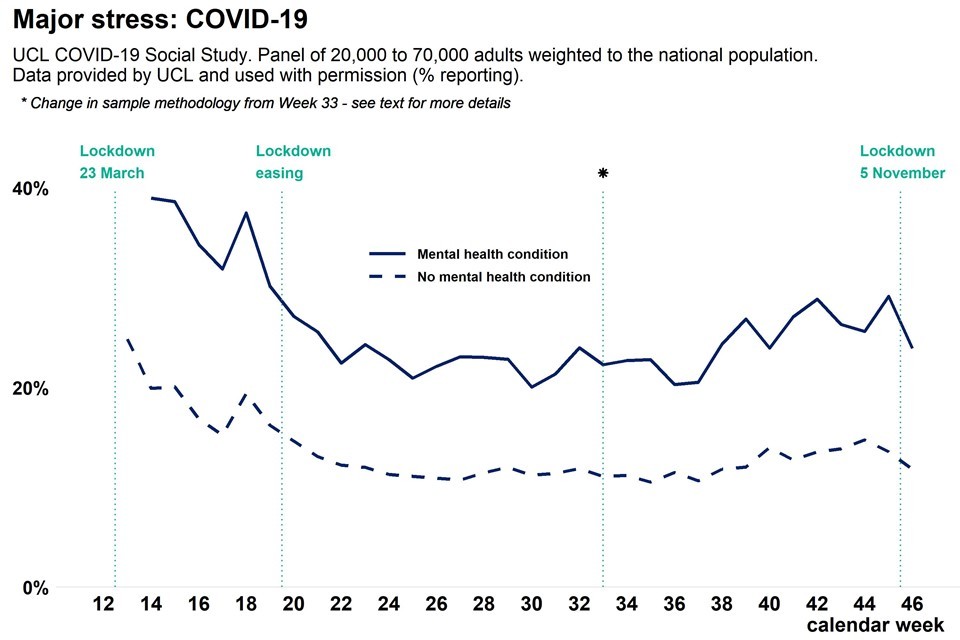

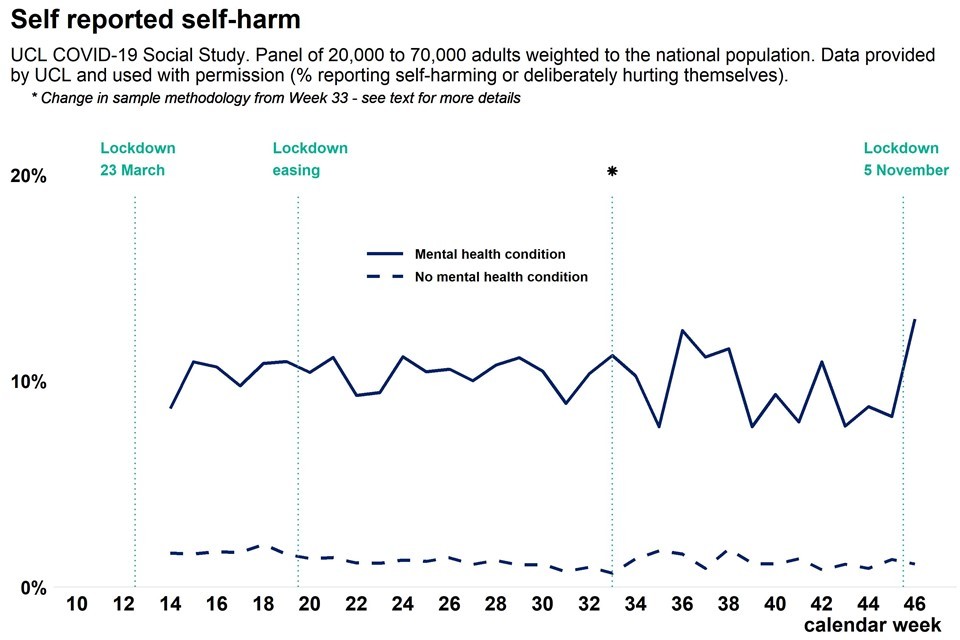

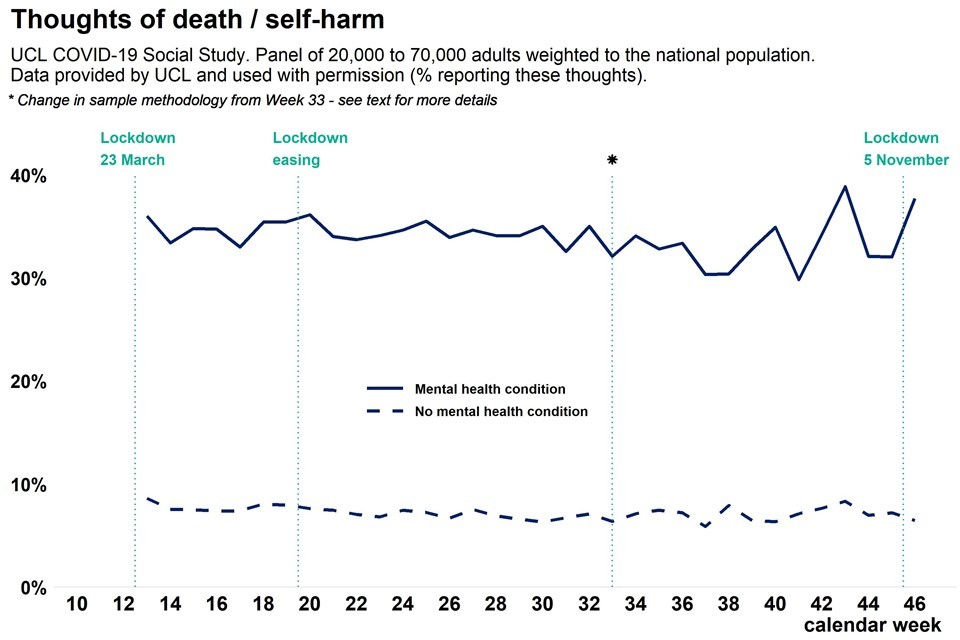

Graphs tracking pre-existing mental health conditions in the population

The graphs in this section are based on weekly data, and included as an early warning system for large changes and differences between groups.

Each of the graphs suggest that adults with a pre-existing mental health condition are reporting worse mental health and wellbeing than adults without pre-existing mental health conditions. However, the gap between the 2 groups does not appear to be changing significantly.

One exception to this is major stress related to finance. People with pre-existing mental health conditions have consistently been more likely to report major finance-related stress and there is some indication that this gap has increased since the summer.

Up-to-date data is available on the WICH tool.

Graph showing population anxiety measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Graph showing population depression measure as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Graph showing population life satisfaction as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Graph showing population loneliness as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Graph showing population finance related stress as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Graph showing population Covid related stress as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Graph showing population reported thoughts of self-harm as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Graph showing population reported actual self-harm as weekly time trend over pandemic, comparing adults with a pre-existing mental health condition and adults without pre-existing mental health conditions

Analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects

The analysis in this section is based on ongoing academic research, and is included to inform a more precise picture of change over time and differences between groups.

What has the mental health and wellbeing impact of the pandemic been for adults with pre-existing mental health conditions?

Adults with self-reported pre-existing mental health conditions have been more likely to report worse levels of mental health and wellbeing than adults without self-reported mental health conditions. However, this gap does not appear to have increased over the course of the pandemic.

One study following adults between April and August 2020 found that people with pre-existing diagnoses of mental health conditions reported higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms than adults without pre-existing mental illness, but no evidence of that inequality widening. Separate analyses of the same data set found that adults with pre-existing mental health conditions were more likely to report higher levels of loneliness during the first national lockdown.

Adults with pre-existing mental health conditions have also been more likely to report using either avoidant coping (behavioural disengagement, denial, substance use) or socially supported coping mechanisms (emotional support, instrumental support, and venting). This is as opposed to problem-focused coping (active coping, planning) and emotion-focused coping (positive reframing, acceptance, humour, religion). Furthermore, the reported frequency of abuse, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm was higher among people experiencing mental disorders.

On the other hand, a large longitudinal study has reported that respondents with a pre-existing diagnosis of depression have not reported a statistically significant increase in the prevalence of mental health problems or a significant increase in symptoms, as opposed to the population without diagnoses of depression, who have reported increases in both.

A longitudinal study of adults in southwest England found that respondents with pre-existing mental health conditions and those who had reported difficulties accessing mental health information, were at greater risk of persistent anxiety (anxiety in both April and June 2020) than adults without pre-existing mental health conditions.

One study has reported that people with a pre-existing mental health problem have been more likely than the overall population to report not coping well. Although, both this and another study of mental health service users also highlight that the majority of respondents say that they are managing to cope.

What impact has the pandemic had on physical health among adults with pre-existing mental health conditions?

Analysis of data from the UK Biobank suggests that people with a psychiatric disorder have been more likely to be diagnosed with, hospitalised by and die from COVID-19 than people without a psychiatric disorder. This excess risk was observed across all levels of physical comorbidities and subtypes of pre-pandemic psychiatric disorders.

The excess risk increased as the number of pre-pandemic psychiatric disorders experienced by the patient increased. The study also found an association between pre-pandemic psychiatric disorders and increased risk of hospitalisation for other infections.

An NHS Foundation Trust in London has reported 1,109 excess deaths among people with pre-existing mental health disorders between 1 March and 30 June 2020 (out of a total of 2,561 deaths on their mental health register during this period). COVID-19 was recorded as the underlying cause in 64% of this excess, with the remainder accounted for as either unnatural or as yet unexplained, or from neurodegenerative conditions.

None of the excess mortality was attributed to cancer, circulatory disorders, digestive disorders, respiratory disorders, or other diseases. The study does not compare excess deaths among adults with severe mental illness (SMI) to that among adults with no SMI, or account for the impact of comorbidities.

The trust covers an ethnically diverse and urban catchment, with high levels of deprivation. Between 15 March and 16 May 2020 they report an excess mortality ratio of 3.33 among their Black African and Black Caribbean mental health patients, compared to a ratio of 2.47 among their White British mental health patients. If this is limited to premature deaths (where the deceased was aged less than 70) the ratios fall slightly to 2.74 and 1.96 respectively.

A high excess mortality rate among people with SMI has also been reported in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. The majority of excess deaths in this study were among adults aged 70 and over. This was true for adults with and without SMI. However, among adults with SMI there was also evidence of excess mortality between the ages of 40 and 60.

The same study also reported that Black, Asian and minority ethnicity (BAME) adults with SMI in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough have a higher mortality rate than White adults with SMI. However, this inequality was present before the pandemic, and there is not evidence to suggest it has changed since the pandemic’s onset.

Evidence points to an association between many health conditions and mortality from COVID-19. A recent study found that serious mental illness was associated with a relatively modest increased risk of dying from COVID-19 (26% for women compared to women with no serious mental illness, and 29% among men). However, as an illustrative example, type II diabetes was associated with a 529% increased risk for women (compared to women without this diagnosis) and 374% increased risk for men.

What impact has the pandemic had on use of mental health services among people with pre-existing mental health conditions?

An ongoing study that is interviewing adults who use either primary or secondary mental health services has reported that 51% of their sample say they will need either the same or less support during the pandemic. Of the remainder, 20% say that things are difficult, but they are trying to make do with the support they have; 20% say that they need more support because of the pandemic; and 10% say they needed more support before the pandemic, and that remains the case.

A study including responses from people with and without pre-existing mental health conditions has reported that 4% of the sample without said that they had contacted a mental health professional (for example a counsellor) since the start of the first national lockdown, compared to 11% among respondents with a pre-existing mental health problem.

A second study including responses from people with and without pre-existing mental health conditions has found that during the first national lockdown psychiatric medications were the most common type of support being used among people who reported abuse, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm, but that fewer than half of those affected were accessing formal or informal support.

The NHS Foundation Trust in London mentioned above has reported that between 15 March and 16 May 2020 their community mental health teams saw relatively stable caseloads and total contact numbers, but a substantial shift from face-to-face to virtual contacts. Their Home Treatment Teams saw the same shift to virtual contact but reductions in caseloads and total contacts.

The study of service use in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough also reported changes. During the first national lockdown there was a sharp reduction in referrals to primary care mental health services, psychological therapy, liaison psychiatry referrals (except eating disorders) and all secondary care mental health teams (except early intervention in psychosis services). This drop was followed by a subsequent increase towards normal levels.

The changes in referrals to secondary care were proportionally less for patients with SMI than for conditions that are not an SMI. There was also a gradual decrease in telephone calls to the NHS 111 mental health crisis service. Inpatient numbers fell, but new detentions under the Mental Health Act were unchanged, and many services shifted from face-to-face to remote contacts.

Finally, data from the UK Biobank suggests that people with a pre-existing diagnosis of a mental health condition have been more likely to be tested for COVID-19, whether or not they have contracted the virus.

This chapter draws upon weekly data from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study and analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects. It does not directly present data from the NHS as this is reported elsewhere. Data on NHS mental health services provided during the pandemic can be found on the Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS) and Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) websites.