Community-centred practice: applying All Our Health

Updated 1 September 2022

The Public Health England (PHE) team leading this policy transitioned into the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) on 1 October 2021.

Why you should adopt community-centred approaches in your professional practice

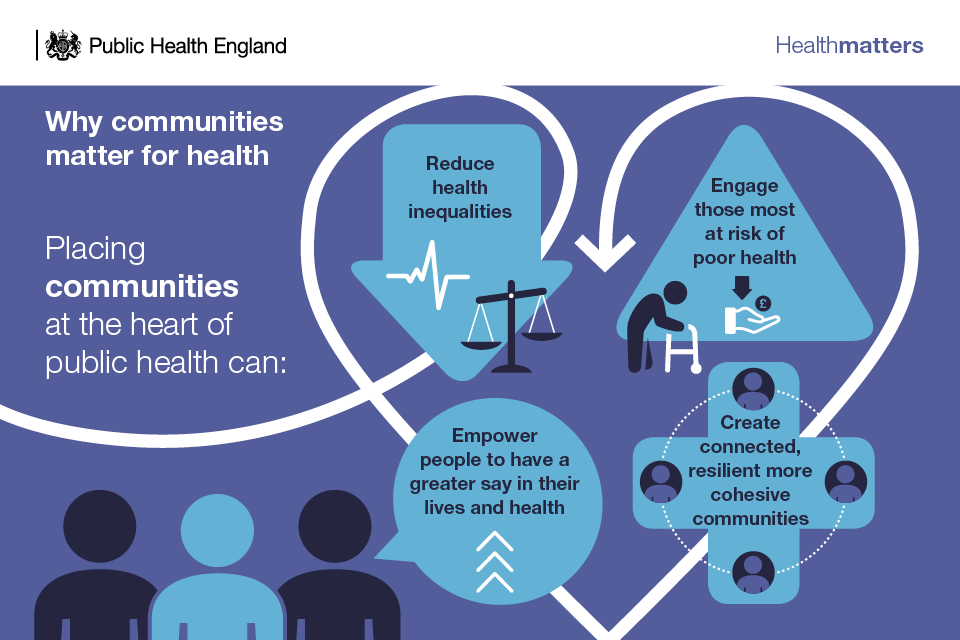

Community-centred ways of working can be more effective than more traditional services in improving the health and wellbeing of marginalised groups and vulnerable individuals. For this reason, they are an essential way of reducing health inequalities within a local area or community.

Those who find themselves excluded from society, discriminated against, or lacking power and control because of living in extreme poverty, can be the least likely to access and benefit from services – despite often having the worst health. Adopting more community-centred practice can help provide more appropriate and effective ways of engaging people and improving their health and wellbeing.

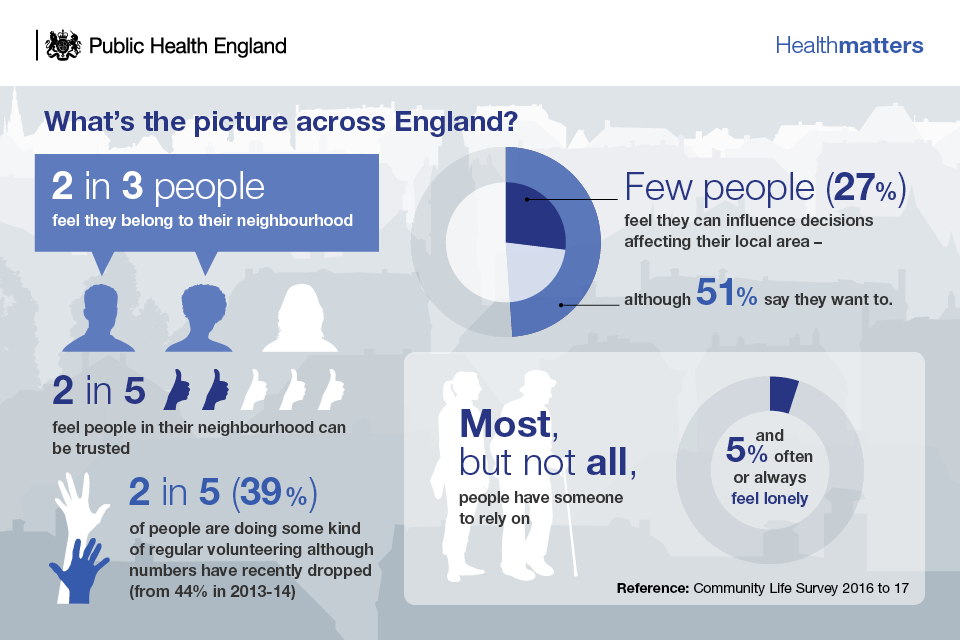

The extent to which we have control over our lives, have good social connections and live in healthy, safe neighbourhoods are all important influences on health.[footnote 1]These community-level determinants are protective of good mental and physical health and can buffer against stressors across the life course.[footnote 2] [footnote 3] However, socio-economic inequalities negatively affect the quality of community life for many.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic demonstrated the importance of community factors for health, particularly trust, neighbourliness, and social connection. Communities played a valuable role in supporting others and we learnt how important it is to listen to and understand community needs and concerns.

This is not only about the places where people live, but also about the connections between people. Social isolation and loneliness are detrimental to health, with review evidence showing that weak social networks and lack of social support are associated with higher health risks.[footnote 4] [footnote 5]

The evidence shows that community engagement interventions have a positive impact on a range of health outcomes across various conditions.[footnote 6] Recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on community engagement (NG44) signals the importance of working in partnership with local communities to plan, design, deliver and evaluate health and wellbeing initiatives.

For the NHS, the Five Year Forward View highlighted the need to ‘fully harness the renewable energy of communities’ as part of a greater emphasis on prevention.[footnote 7]The community contribution of volunteers and residents active in their neighbourhoods is also important for local government.[footnote 8]

Building on an earlier ambition in its Five Year Forward View to ‘fully harness the renewable energy of communities’, the NHS Long Term Plan set out how the service will work to improve population health over a 10 year period (2019 to 2029). A key ambition in this plan is to improve care out of hospitals and a commitment to develop fully integrated community-based health care.

Integrated care systems and the primary care networks within them will be an important aspect of this delivery, though achieving this will only be possible where volunteers and residents are meaningfully involved. From a public health perspective, involving people in volunteer and peer roles can help strengthen social networks and offers a means to access and connect with groups at risk of social exclusion.[footnote 9]

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the government’s prevention green paper set out the importance of community assets and community-based activities, such as social prescribing, in supporting its aim to prevent ill health. Since then, recent government has re-instated the importance of community-centred approaches in improving population health and strengthening community resilience.

The ‘Beyond the data: understanding the impact of COVID-19 on BAME communities’ report, and it’s follow-up report ‘Beyond the data: one year on’, highlights the importance of understanding the wider determinants of ill health for people from minority ethnic backgrounds and inclusion health groups. Learning from community-centred interventions used in the COVID-19 response, such as the COVID-19 community champions scheme, have contributed to understanding how to work with communities to design action to reduce health disparities.

The government’s levelling up white paper recognises the importance of social capital to quality of life and prosperity and sets out how government will work to restore ‘pride in place’ in communities.

Core principles for healthcare professionals

The core principles of community-centred approaches are that they:

- promote health and wellbeing or reduce health inequalities in a community setting, using non-clinical methods

- use participatory methods where community members are actively involved in the design, delivery, and evaluation of services and locally-based activities

- address barriers to engagement and enable people to play an active part

- utilise and build on the local community assets in developing and delivering the service or activity

- find ways to work in partnership with individuals and groups at most risk of poor health

- have a focus on changing the conditions that drive poor health alongside individual factors

- aim to increase people’s control over their health and lives

Taking action

If you’re a frontline health professional

You should:

- understand the health needs of the local population, and the things that are influencing poor health for different communities

- consider how people’s social and emotional needs are affecting their health, for example their relationships, social networks, and support in their neighbourhood

- adopt person-centred and strengths-based practice when communicating with and assessing patients. This may involve health coaching and co-producing care plans. See the person-centred care framework

- find out what community and voluntary services and groups there are in the local area, and actively signpost patients to them to improve their health and wellbeing

You can also consider how the services you provide can incorporate more community-centred approaches, by:

- developing peer roles, for example, where patients provide support to each other

- using volunteers in aspects of the service

- engaging with patient groups and community representatives to plan, review and improve the service

- participating in social prescribing schemes or integrated wellness services – where health services and voluntary and community groups work together to provide non-medical sources of support

- working in partnership with other professionals and community organisations to provide joined-up local services

Examples of community-centred practice can be found in the UK Health Security Agency’s online library.

If you’re a team leader or manager

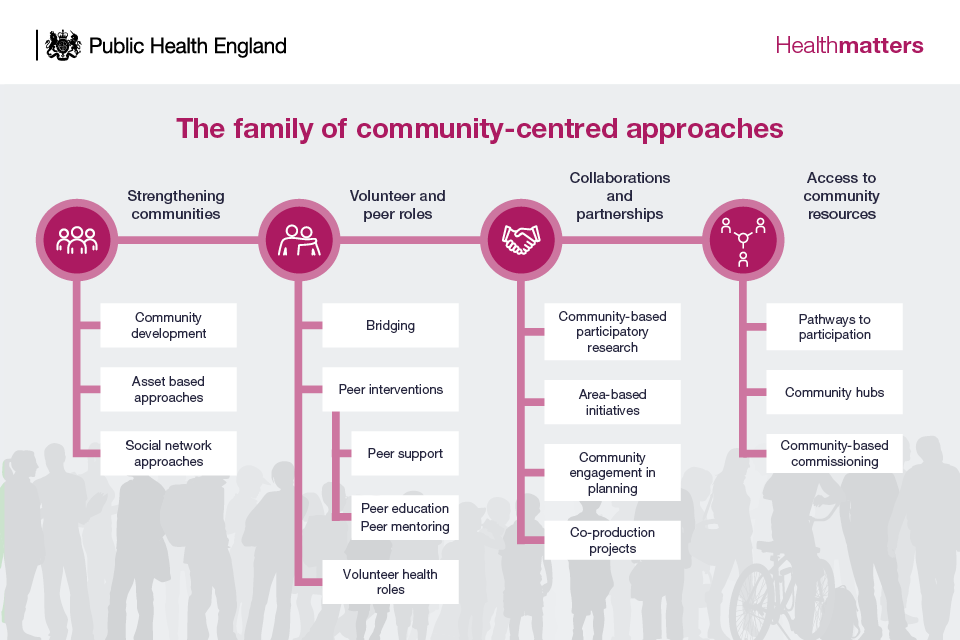

Consider how community-centred approaches can be adopted by the team. National guidance by PHE and NHSE divided this into 4 strands of approaches, recognised by NICE guidance:

- strengthening communities, for example, community development approaches to build action on health issues such as road traffic accidents, parenting support and green space use – as well as timebanking schemes that help build social networks for people with long-term conditions by neighbours helping each other out

- volunteer and peer roles, for example – mutual aid within drugs recovery, breastfeeding mums groups, health walk volunteers, peer support in mental health

- collaborations and partnerships, for example – patient forums for joint decision-making, patient commissioning panels, patient-led research

- access to community resources, for example – social prescribing, services provided within local community hubs alongside other services

If you’re a senior or strategic leader

You should implement NICE guidance on community engagement (NG44), and also use the NICE quality standards for quality assurance and commissioning, to ensure:

- members of the local community are involved in setting priorities for health and wellbeing initiatives.

- members of the local community are involved in monitoring and evaluating health and wellbeing initiatives as soon as priorities are agreed

- members of the local community are involved in identifying the skills, knowledge, networks, relationships and facilities available to health and wellbeing initiatives

- members of the local community are actively recruited to take on peer and lay roles for health and wellbeing initiatives

- the family of community-centred approaches are used to map, plan, commission or deliver local services

Community-centred systems

There is increasing recognition that reducing health disparities requires a complex system approach that puts communities at the heart of everything we do. Research has shown this can be achieved through:

- greater involvement of communities in decision-making, delivery and evaluation

- scaling integrated community-centred prevention at neighbourhood levels

- developing community roles and staff skills in community-centred ways of working

- investing in and valuing the voluntary and community sector

- developing long-term relationships with communities to build trust

- shifting mindsets and organisational cultures towards community-centred practice

Understanding local needs

A good understanding of local needs in relation to community life, social isolation, neighbourhood belonging and people’s emotional wellbeing and resilience is best collected locally by:

- speaking to communities

- listening to patients and carers

- conducting local research to gain insight

The local authority and voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations (including faith-based) can be a good source of information. Health professionals are in a good position to listen and learn about what’s happening locally in their patch.

Routinely collected local data is available on OHID’s online health profiles. Related measures include:

- self-reported wellbeing

- social connectedness

- wider determinants data, which will give an indication of the level of need in the community and populations – and also indicate who might benefit from these approaches

Indicators on loneliness, social isolation, social capital, and wellbeing are included in the Mental Health Profiles.

Many of the community measures are from national-level data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, for example, social capital.

Further local wellbeing indicators are available from the What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

Measuring impact

NHS England (NHSE) worked with National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA) on the Realising the Value project, on person and community-centred practice in health and care. It has produced a guide on modelling the potential impact of 5 approaches that have shown impact.

These are:

- peer support

- self-management education

- health coaching

- group activities to support health and wellbeing

- asset-based approaches, in a health and wellbeing context

Each of these 5 approaches impact:

- financially, for example – peer support for people with mental health problems have the greatest net financial gain

- health and wellbeing outcomes, for example – health coaching is particularly beneficial for people with long-term conditions[footnote 1]

- wider social impact, for example – self-management for people with cancer has the highest net gain in social impact

Peer support and self-management education have the potential to offer commissioners £2,102 savings per person per year, or £5.2million for the CCG.

-

Marmot M, 2010, Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010 London: The Marmot Review. ↩ ↩2

-

Friedli L. Mental health, resilience and inequalities. Denmark: World Health Organization Europe, 2009. ↩

-

Chief Medical Officer. Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer London: Department of Health, 2012. ↩

-

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. ↩

-

Valtorta, N.K., Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;0:1 to 8. ↩

-

O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(129). ↩

-

NHS England. NHS Five Year Forward View. London: NHS England; 2014. ↩

-

Local Government Association. Community action in local government. A guide for councillors and strategic leaders. London: LGA, 2016. ↩

-

South, J. and others. People in Public Health – a study of approaches to develop and support people in public health roles. Report for the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme. 2010, NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme. ↩