Changing gender norms: engaging with men and boys

Published 15 January 2021

Changing Gender Norms: Engaging with Men and Boys

Research report prepared by Stephen Burrell, Sandy Ruxton and Nicole Westmarland, Durham University, for the Government Equalities Office

October 2019

This research was commissioned under the previous government and before the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result the content may not reflect current government policy, and the reports do not relate to forthcoming policy announcements. The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the government.

Executive summary

Introduction

This report provides an in-depth exploration of how to engage with men and boys to address social norms connected to masculinity and challenge and change harmful gender stereotypes in the UK today. The research was commissioned in 2019 by the Government Equalities Office. The primary aim of the project was to consolidate existing knowledge from both research and practitioner experience, and apply that with an engagement toolkit which sits alongside this research report together with a longer literature review. There is surprisingly little research in the UK context on how to engage with men and boys in relation to gendered social norms. As such, this research should be understood as a starting point to open up discussions in this area rather than the final word on the issue.

‘Social norms’ are implicit and informal rules of behaviour shared by members of a group or society, which most people within that group accept and abide by. ‘Gender norms’ define the different practices that are expected of women (what is understood as being ‘feminine’) and of men (what is seen as being ‘masculine’). There is ambiguity in the ways in which the concept of ‘gender norms’ is used, and different terms (for example, ‘gender roles’, ‘masculinities’/’femininities’) often overlap or are used interchangeably. For the purposes of clarity, we prefer to use the term ‘gendered social norms’.

Research methods

The research involved 3 stages:

-

A rapid evidence assessment of relevant literature.

-

17 key-informant interviews.

-

An online survey of 143 practitioners’ views.

Three online meetings were also held during the project with an NGO expert panel. Given the short timeframe of the project, the research was intended to be exploratory. This is reflected in the concise nature of the rapid evidence assessment, and the relatively small samples for the key- informant interviews and survey. Nevertheless, they still provide diverse, important and useful insights into the impacts of gendered social norms on men and boys in the UK today, and how to develop effective engagement work and policy interventions on these issues.

Review of existing literature

The literature highlights that social and gender norms change over time, across cultures and within particular groups. Whilst attitudes and values can reside in individuals, norms are also embedded in wider organisations, institutions, structures, processes and systems, and reflect the rules, laws, customs and ideologies of different societies (Connell and Pearse, 2014). Changing gender norms is therefore not just about changing individual mind-sets, important though that objective may be.

The literature review demonstrated that gendered social norms continue to significantly shape the lives of men and boys in the UK. While important shifts have taken place, these often reflect changes in what it means to be a man rather than a reduction in the need to conform to certain ideas of masculinity more generally. Furthermore, changes in normative perceptions do not necessarily equate to changes in behaviour. For instance, research suggests that women still carry out the bulk of childcare and housework despite now playing a significant role in the labour market (van der Gaag and others, 2019).

Expert interviews

The key-informant interviews were wide ranging in nature. They underscored how vital it is to adopt an intersectional approach when seeking to understand and engage with issues around men and masculinities. Gendered social norms can vary significantly among different groups of men and boys and are shaped by different power relations and inequalities in addition to those of gender. For example: older men face an increasing contradiction between their conscious or unconscious desire to live up to norms they grew up with (‘be tough’, ‘be strong’, ‘be independent’), and the reality that they may be less able to do so. Men with disabilities are often unwilling or unable to live up to ‘ideal’ models of masculinity based on body strength and performance. Gay, bisexual and/or transgender men are often marginalised as a result of being seen to go against heteronormative masculine expectations. When working with men and boys, it is crucial to take such differences into account to make sure that interventions are relevant to the diverse contexts in which they live their lives.

Another theme across the key-informant interviews was the need to find ways to engage with men and boys positively, without negative preconceptions (which may themselves be based on stereotypes of masculinity). This means providing a source of hope and optimism for men and boys about how they can be part of changes in social norms.

Survey of people working with men and/or boys

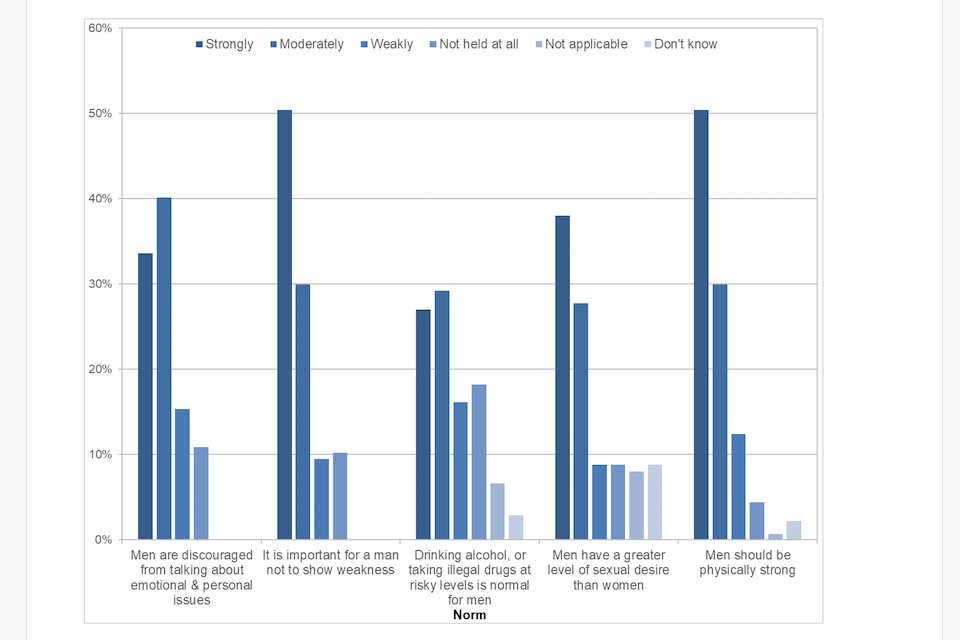

The first part of the online survey asked about traditional masculine norms related to health and wellbeing. For each of the 5 example norms given, the majority of respondents felt they had a strong or moderate influence on the men and boys they work with. This was particularly true of notions that men should not show weakness, and that men should be physically strong (in both cases, 50% felt this norm was strongly held and 30% felt it was moderately held).

The second part of the survey asked for respondents’ perspectives on the norms held by the men and boys they work with regarding men’s roles within intimate partner relationships. The findings here were more varied and complex. In 2 cases, the majority of respondents did feel that a traditional gender norm remained highly influential: that women make better caregivers for young children than men (which 43% felt was strongly held and 33% felt was moderately held), and that a man should be the main ‘breadwinner’ in the family (which 29% felt was strongly held and 37% felt was moderately held). For the other 3 example norms, responses were more mixed.

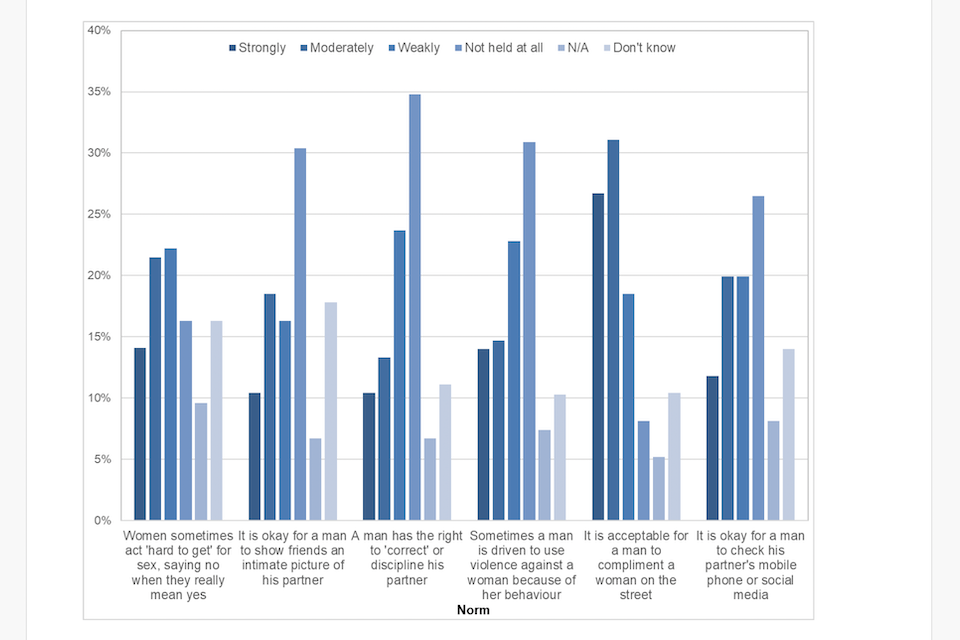

The third part asked respondents about their views on the impact of gender norms which could be understood as contributing to violence against women and girls. This set of example norms generated the most diverse findings. In some cases, the majority of respondents suggested that norms of masculinity connected to violence against women and girls were not particularly influential for the men and boys that they work with. Others, however, remained strongly held; for example, for the notion that women sometimes act ‘hard to get’ for sex and say no when they really mean yes, 14% viewed this as being strongly held, 22% felt it was moderately held, 22% felt it was weakly held, and only 16% felt it was not held at all.

Conclusions and recommendations

Here we set out key conclusions from the research and a selection of our recommendations for taking this work forward in the UK.

Policy and campaigns

Norms of masculinity are at the roots of a range of significant policy and public health issues, from men’s mental health to violence against women. It is important not to lose focus on the importance of structural, legislative and societal change – these play the biggest role in shaping social norms, and attention to norms should not lead to a focus only on individuals.

Here are 2 of our 4 recommendations on this:

-

There is a real need for more engagement with men and boys (and all members of society) across the UK from a young age about gender norms and inequalities.

-

Policies, programmes and campaigns should be designed in ways which encourage gender equality and avoid perpetuating harmful norms and stereotypes. In representing and approaching men and masculinities, it is important to avoid reproducing stereotypes and limiting norms around gender in the process.

Engaging with men and boys

Whilst one-off, single-level forms of engagement are an important first step, they are not enough to foster sustainable transformations in gender norms and inequalities.

-

Policymakers and practitioners should work together to develop multi-level, in-depth interventions with men and boys to shift gender norms in different contexts.

-

A positive approach to engaging with men and boys through dialogue, highlighting opportunities for creating change, is an important element of effective practice.

-

Guidance on working with men and boys should focus on how to build effective relationships that enable productive work to happen, and staff and volunteers doing specialist engagement work in this area should be trained to a high standard.

-

Childhood and fatherhood – Gender norms and stereotypes constrain opportunities for boys and girls by presenting them with a limited set of possible expectations and behaviours, reinforced through different play environments, toys and clothing (for example).

-

Guidance and training for ante-natal, early childhood and health practitioners should be developed so they are aware of the impact of gender norms and how they can be shifted. It is crucial to begin to work with new fathers and with boys at a young age when they may be most receptive to the questioning of norms.

-

Norms of fatherhood have expanded in recent decades to include closer involvement with children. The introduction of a number of months of paid leave targeted specifically at fathers would reinforce this trend.

Education

Dominant norms of masculinity for boys and young men at school often involve ‘hardness’, sporting prowess, ‘coolness’, and casual treatment of schoolwork. However, away from peer group pressures, boys can be much more reflective. There is considerable variation among boys at school, and social class and ethnicity are frequently more influential on achievement than gender.

Here are 3 of our 5 recommendations:

-

There is a need for greater reflection and learning about gender norms and inequalities throughout the school curriculum.

-

Training should be available for all teachers on the influence of gender stereotypes and the benefits of challenging them.

-

Literacy programmes should be mindful of the influence of gender norms, and it is not enough for them to be gender neutral if they are aimed at raising the literacy levels of boys and young men.

Health and wellbeing

Many issues connected to the health and wellbeing of men and boys are directly related to social norms and traditional constructions of masculinity, such as the expectation to be ‘tough’ and ‘strong’, appear in control, take risks, and not seek help. However, there are also norms relating to masculinity – for example, around physical fitness, that may positively support health.

Two of our 4 recommendations on this are as follows:

-

Attention to gender norms and how these play out for different groups should be a central component of health strategies at national and local levels.

-

It is vital to create more supportive community spaces to help address social isolation and loneliness among men, and give them opportunities to explore issues around gender, masculinity, relationships, sexuality, violence, health and wellbeing.

Employment

Organisational structures, cultures and practices tend still to be based on an assumed masculine norm of lifetime, full-time, continuous (male) employment. ‘Masculine’ values are strongly embedded within many organisations (for example, through job segregation, sex discrimination, gender pay gaps, sexual harassment, workaholic culture).

-

Employers, trade unions and careers advisors should take a more proactive approach to challenging gender stereotypes in employment and training choices.

-

Work-based initiatives should be developed to engage men around the health issues they face, including risk-taking and mental health issues.

-

Employers should make greater efforts to support men’s roles in caring.

Violence against women and girls

Norms of masculinity are a central factor in the continued pervasiveness of violence against women and girls, with expectations of superiority, power and entitlement over women seemingly continuing to be influential in perceptions of what it means to be a man.

- A gendered approach to tackling violence against women and girls is vital for effective policy and practice interventions.

- Transforming gender norms and tackling gender inequalities should form a key part of efforts to prevent violence against women and girls from happening in the first place, and engaging men and boys is a particularly important aspect of this.

Media

Representations of men and masculinities in TV shows, adverts, magazines, films and music videos habitually reflect restrictive, unrealistic and stereotypical images. Increasing and easy access to pornography routinely presents men as dominant and women as sexual objects.

However, the media can also be powerful in generating a more positive debate when they challenge accepted ways of thinking and behaving.

-

Educational initiatives to assist viewers, and especially young men, to analyse media content critically – and particularly the portrayal of gender – should be significantly expanded.

-

Comprehensive relationships and sex education which considers harmful gender norms in relation to pornography is vital, along with the development of media literacy and strengthening the filtering of access to pornographic websites (especially for those under 18).

-

There is potential for the development of online communication and social media campaigns which challenge restrictive representations of masculinity.

-

Men in positions of power should provide high-profile and proactive support for gender equality and encourage other men to play their part, including by modelling different, healthier ways of being a man.

Developing organisations working with men and boys

There is a range of innovative and impactful work being done with men and boys and on gender norms around the UK; however, it is currently quite fragmented and piecemeal. In addition, engaging men in building gender equality will be counterproductive if an alternative message is given by the underfunding and undervaluing of services for women and girls.

-

Organisations leading the way in engaging with men and boys and looking critically at masculinities should be supported and resourced by the government; however, this should not be at the expense of women’s organisations and services.

-

Organisations working in this area should be more connected in order to share good practice and collaborate. The government could help to facilitate this.

Approaching gendered social norms

In order to create normative change, and in ways which can be measured, it is important to be clear and specific in language and frameworks about the norms that we want to shift, how they work and how we aim to change them.

We have 5 recommendations on this, including the following and others:

- Policymakers and practitioners should consider how they can embed gender-sensitive and gender-transformative approaches within different interventions – and not only those which explicitly seek to address gendered issues.

- A key task is to illuminate the diverse ways in which many men are already living their lives and challenging stereotypes around masculinity.

Intersectionality

It is important to recognise that men and boys are not a homogenous group and are simultaneously affected by different aspects of their identity and positions within different social categories and systems, including age, social class, ‘race’ and ethnicity, sexuality and disability as well as gender. These factors also shape gender norms, which vary for different groups of men and boys in different contexts.

- Policy and practice should adopt an intersectional framework to understand the complexities of men’s and boys’ lives, recognising that some men have more power than others as a result of different social inequalities, to engage with them in relatable and relevant ways.

Evidence gaps

There is a need for more extensive research and measurement of the nature and impacts of gendered social norms in the UK today. We still do not have enough understanding about the dynamics of how to change gender norms. This is especially true for the UK, where there has been less work in this area than in some other contexts.

-

Policy and practice should draw from new and existing research on men, masculinities, gender norms and inequalities when developing interventions.

-

The Government Equalities Office could play a central role in disseminating promising practices in engaging men and boys around gender norms.

1. Introduction

This report provides an in-depth exploration of how to engage with men and boys to address social norms connected to masculinity and challenge and change harmful gender stereotypes in the UK today. The primary aim of the research was to consolidate existing knowledge from both existing research and practitioner experience about how to effectively apply this knowledge to develop a toolkit to support future work with men and boys on issues related to masculine gender norms in the UK.

The research was commissioned in 2019 by the Government Equalities Office (GEO) as a result of its efforts to build evidence on the gender pay gap and how best to close it. To support this work, the GEO is developing research on topics related to the unobserved element of the gender pay gap, including gender norms, and what more government, schools, parents and individuals can do to help reduce the harmful stereotypes, attitudes and behaviours that can contribute towards it. With this project, the GEO sought to find out more about what works to engage men and boys on gender and relationships in relation to the UK context.

The GEO set out the following research questions for this piece of work:

-

How are masculine gender norms formed and enacted in the UK? How does this vary by demographic? – for example, people from different ethnic minority groups, people with disabilities, people from different socioeconomic groups, LGBT people?

-

What impact do masculine gender norms have on the behaviour of men and boys in the UK?

-

What impact do masculine gender norms have on the wellbeing of men and boys in the UK?

-

Do masculine gender norms contribute to violence against women and girls in the UK?

-

What are the best ways to communicate with men and boys about harmful masculine gender norms? How can this knowledge be applied to support delivery of UK policy interventions?

-

Have any interventions been successful in reducing the negative impacts of masculine gender norms? How could these be applied in the UK policy context?

These are very broad, complex questions and there was a limited time period for the work to be completed in. We responded to them using a rapid evidence assessment, qualitative interviews with experts, and an online survey of practitioners who work with men and/or boys. The work was supported by an expert panel. However, there are limitations to the research, including our inevitably restricted recruitment approach (relying on networks and snowball sampling) and relatively small sample sizes. In particular, it was difficult to fully apply the intersectional lens that this issue requires. This report should be read with such caveats in mind. There is surprisingly little research in the UK context on how to engage with men and boys in relation to gendered social norms. As such, this research should be classed as a starting point to open up discussions in this area rather than the final word on the issue.

The remainder of this chapter will explore the concept of gendered social norms and discuss how it is used in this report. Chapter 2 describes the methods the research team used to answer these questions in more detail (including the limitations of the research). Chapter 3 then gives an overview of findings from a rapid evidence assessment of relevant literature. The following and others chapters report the findings from the new data collected for this report, based on key-informant interviews (Chapter 4) and an online survey (Chapter 5). We also conducted 3 online meetings over the course of the project with a panel of 9 experts from relevant non-government organisations (NGOs), which informed the development of the research. Finally, in Chapter 6 we bring together our main conclusions and recommendations.

1.1 What are social norms in relation to gender?

Social norms and gender norms are concepts which are highly influential in understanding the gendered behaviours of individuals, as well as the gender relations and inequalities in society more broadly. We begin this report by discussing some of the thinking behind them – which is also much debated and contested. The term ‘social norms’ refers to the implicit and informal rules of behaviour shared by members of a group or society – a ‘reference group’ (Bicchieri, 2006) – that are held in place by empirical and normative expectations, and which most people within that group accept and abide by (Cislaghi and Heise, 2016). Social norms are influenced by a variety of factors, such as belief systems, the socioeconomic context, and through perceived rewards and sanctions for adhering to (or not complying with) prevailing norms. Norms are embedded in formal and informal institutions and produced and reproduced through social interactions. They are learnt primarily by observing:

- what other people do (X) in situation (Y) (‘empirical expectations’ or ‘descriptive norms’)

- how other people react (including not reacting at all) when someone does X in situation Y (‘normative expectations’ or ‘injunctive norms’) (Bicchieri, 2006; Cialdini and others, 2006; Mackie and others, 2015)

Within different social groups and societies, there are many powerful and influential social norms constructed in relation to ideas about gender – often referred to as ‘gender norms’. These specifically define the different things that are expected of women (what is understood as being ‘feminine’) and of men (what is seen as being ‘masculine’). As with all social norms, these vary according to context and within different social groups (for example, depending on class, ethnicity, sexuality and age) and societies. This is one reason why it is important to take into account that rather than there being one form of masculinity or femininity, there is a plurality – and these are ordered hierarchically, with some forms holding more power than others (Connell, 2005). Furthermore, these norms often play an important role in maintaining and legitimising gender inequalities – indeed, that may often be where their origins lie (Connell, 2005; Hearn, 2012).

Gendered social norms shape acceptable, appropriate and obligatory actions for individuals in a social group or society. They are both embedded in institutions and nested in people’s minds.

They play an important role in shaping women’s and men’s unequal access to resources and freedoms, affecting their voices, agency and power (Cislaghi, Manji and Heise, 2018). Gendered social norms are usually taken to define the expected behaviour of people who identify as, or are identified by others as being, male or female. In other words, they are constructed in a binary way and often do not recognise or include non-binary or gender-fluid identities. They are frequently heteronormative, with lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender (LGB and/or T)[footnote 1] people often experiencing marginalisation as a result of dominant gender norms, which they may be viewed as failing to conform to (Connell, 2005). Indeed, more space for dialogue and research is needed to advance our understandings of the relationships between sex and gender, and how gender norms impact on those who do not necessarily identify as a man or a woman or within a binary of masculinities and femininities (Hearn, 2014).

It is important to note that social and gender norms are contested, and are continually subject to debate, dissent and re-evaluation. They change over time, across cultures and within particular reference groups. Whilst attitudes and values reside in individuals, norms are also embedded in wider organisations, structures, and systems, and reflect the rules, laws, customs and ideologies of different societies (Connell and Pearse, 2014). Changing gender norms is therefore not just about changing individual mind-sets.

1.2 Conceptualising gendered social norms

There is sometimes ambiguity in the ways in which the concept of ‘gender norms’ is used, and different terms often overlap or are used interchangeably, such as ‘gender norms’, ‘gender roles’, and ‘masculinities’/’femininities’. For the purposes of clarity, we primarily use the term ‘gendered social norms’ throughout this report, as we are discussing a specific, gendered subset of broader social norms, and how they might apply in different ways for different groups of men and boys.

This also makes it possible to move beyond some of the critiques that have been made about the notion of changing gender norms, or there being ‘healthy’ or ‘harmful’ forms of gender norms.

Some theorists (for example, Flood, 2015a) have contested that gender norms altogether can be seen as harmful, in the sense that people should not feel that they have to conform to any specific social expectations based on their gender or sex. Furthermore, norms of ‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’ are relational – they are constructed in relationship with one another and defined in opposition to one another, and this is generally seen as being a hierarchical relationship (Connell, 2005). In other words, the masculine is defined as superior to and dominant over the feminine, and even positive traits commonly associated with femininity are typically subordinated in relation to traits associated with masculinity.

However, social norms more broadly can serve positive societal functions, and it is possible and desirable to strive to create healthier, egalitarian social norms. It could, therefore, be argued that rather than changing gender norms, we should seek to reduce their impacts and, ultimately, remove them altogether from society, so that people can live their lives free from any specific set of expectations based around gender. It is difficult to justify why any positive trait frequently associated with femininity (for example, being caring) or masculinity (for example, being courageous) should only be associated with women or men. Furthermore, even when qualities perceived to be positive are gendered in this way, they can still foster negative consequences – for example, an expectation for men to act courageously may not be healthy in all circumstances and might make it difficult for men to be open about being vulnerable.

We can instead focus attention on and encourage healthy social norms that apply to all people, such as equality, respect and non-violence within intimate relationships. Indeed, this debate highlights that by engaging men and boys on the basis of fostering healthier forms of masculinity, for example, there is a danger that interventions might actually reaffirm men and boys’ commitment to gender norms, rather than helping them to free themselves from such constraints (Burrell, 2018; Flood, 2018). This underscores the importance of developing a coherent theory of change when engaging with men and boys around issues of gender and social norms (Burrell and Flood, 2019).

2. Research methods

The research started in March 2019 and began with a rapid evidence assessment of relevant literature, which was added to throughout the project until August 2019. The second part of the research involved conducting 17 key-informant interviews, between 23rd April and 17th June 2019. Finally, an online survey of practitioners’ views was carried out between 17th May and 14th June 2019. Three online video conference meetings were also held at the early, mid and late stages of the project with a NGO expert panel. Each part of the project (including data collection, analysis and write-up) was carried out by all 3 members of the research team.

Given the short timeframe of the project, the research was intended to be exploratory. This is reflected in the concise nature of the rapid evidence assessment, and the relatively small samples for the key-informant interviews and survey. The samples are, therefore, not representative of the UK population as a whole and may also not be representative or generalisable to the population doing work with men and boys. Nevertheless, they still provide diverse, important and useful insights into the impacts of gendered social norms on men and boys in the UK today, and how to implement effective engagement work and policy interventions on these issues.

2.1 Expert panel

The purpose of the NGO expert panel was to consult with and hear the views of leading practitioners to help inform different aspects of the research and outputs. The panel was made up of 9 members, invited to take part as representatives of a range of different NGOs working on issues closely connected to masculine gender norms and identified by the research team as being particularly influential or important for the UK context. In addition, we consulted with the GEO for advice and feedback throughout the project. Hearing these views was an important way of trying to ensure that the project was pertinent to practice and that as broad a range of perspectives as possible were reflected in the research development, as well as reducing the influence of potential biases as a result of existing standpoints from the research team.

2.2 Rapid evidence assessment

As part of the project, we undertook a rapid evidence assessment to ensure that the review of the literature was carried out as efficiently and rigorously as possible within the timescale of the project (Varker and others, 2015). There is a wide range of literature on issues relating to masculine gender norms; relationships, wellbeing, and violence against women; and engaging with men and boys. However, the extent of research which specifically addresses these issues in combination with each other, in ways which are relevant to interventions in the UK context, is much smaller.

Utilising the rapid evidence assessment approach enabled us to find the most applicable publications for this specific project, as it meant including or excluding literature based on the following criteria:

Table 1: Rapid evidence assessment – Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Geographical location | UK + research which appears particularly relevant or applicable to the UK context | Lack of relevance/applicability to the UK context |

| Language | English | Not in English |

| Publication date | 2009 to 2019, or before if judged to be highly influential or relevant | Pre-2009 unless judged to be highly influential or relevant |

| Publication format | Journal articles, research- based working papers, other academic research, evaluations, policy briefings, |

| governmental and NGO research reports | Student dissertations or theses, overtly political or commentary pieces, research with obvious methodological weaknesses (for example, no ethical review, no discussion of methods of analysis) | ||

| Aim of study | Medium or high overlap with aims of current study | Low overlap with aims of current study | |

| Study design | Primary empirical research (quantitative OR qualitative) OR systematic reviews OR theoretical development | EITHER lacking explanation of methodology OR secondary literature review OR case commentary |

In order to find the most relevant literature, we applied the following search terms within and others academic bibliographic databases, Google Scholar and Scopus. The numbers indicate how many results each search yielded in the and others databases, specifically for sources published between 2009 and 2019:

Table 2: Rapid evidence assessment – Search terms

| + Men | + Boys | |

| Relationships + Norms | Google Scholar: 4 |

| Scopus: 1,109 | Google Scholar: 3 |

| Scopus: 197 | ||

| Wellbeing + Norms | Google Scholar: 1 |

| Scopus: 67 | Google Scholar: 0 |

| Scopus: 28 | ||

| “Violence against women” + Norms | Google Scholar: 2 |

| Scopus: 130 | Google Scholar: 2 |

| Scopus: 24 | ||

| Engaging + Norms | Google Scholar: 3 |

| Scopus: 129 | Google Scholar: 0 |

| Scopus: 32 |

The publications found as a result of these searches were then sifted for relevance using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. From this, a list of the most applicable literature was produced for detailed review. These publications were then read with notes made about key findings, which were stored in a shared Durham University Box directory and thematically analysed and synthesised to inform the report and engagement toolkit.

To ensure that we did not miss out on any particularly relevant literature, we also used additional methods to find publications. This has included consulting our own existing reference lists; asking contacts with knowledge of the area (including members of our NGO expert panel); and posting call-outs on relevant mailing lists for recommendations (including: British Sociological Association Violence against Women Study Group Jisc mailing list; Masculinity Studies Jisc mailing list, Men against Violence mailing list; MenEngage Europe mailing list; PROFEM mailing list). As a result, we have also cited publications from prior to 2009 if we judged them to be particularly influential or important for the project.

2.3 Interviews with experts in the field

For the first part of the empirical research for the project, we conducted 17 qualitative key- informant interviews with individuals identified as experts in relation to practice, policy and research on gendered social norms and engaging men and boys in the UK. The participants were selected based on the research team’s knowledge of the field together with suggestions made by the NGO expert panel. Several of the interviewees were representatives or practitioners from different organisations relevant to the topic of the research, and we sought to hear a diversity of views to encapsulate the range of different forms of work being undertaken with men and boys.

We also spoke to 5 academic experts on different aspects of masculine gender norms identified as being particularly influential in the UK context.

The interviews were semi-structured, with a range of questions about masculine gender norms in the UK, how to engage effectively with men and boys, and the work that participants were doing and aware of in this area (see Annex I for topic guide). They lasted approximately one hour on average. Interviews were conducted either through an online video call or by phone and transcribed before being thematically analysed. Five interviewees were women and 12 were men, and they were based in different locations across the whole of the UK. The sample was predominantly white British or white European, and one participant was Black African. The sample was generally middle-aged, with ages ranging from 31 to 71.

2.4 Survey of practitioners who work with men and boys

For the second part of the data collection for the project, we sought the perspectives of people doing some form of work with men and/or boys in their everyday lives in the UK via a short (10 to 15 minute) online survey. While a survey with men and boys as beneficiaries was considered, this was decided against in this project for and others reasons. First, due to the longer timescale and higher ethical requirements of doing research with children. Second, as the main purpose of the study was about engagement with men and boys, people whose role involves working with them were viewed as an important group in themselves to survey.

The survey included a mixture of quantitative and qualitative questions about respondents’ views on the impacts of masculine gender norms in the UK today, and how to engage with men and boys about these norms (see Annex II for survey questions). The survey was completed by 143 people. It was distributed online through relevant contacts, networks, organisations and social media accounts, with the help and advice of the NGO expert panel. The majority of respondents (58%) were women, whilst 41% were men[footnote 2] (this may reflect women being more aware of issues relating to gender). There was a mixture of ages, largely clustered around the middle age ranges.[footnote 3]

Survey respondents were doing a wide range of different forms of work with men and boys in different contexts, including as: teachers (at all levels of education), support workers, GPs, prison officers, NGO practitioners, youth workers, social workers, probation officers, nurses, volunteers, police officers, counsellors, community development workers and paramedics.

-

36% of respondents worked with men/boys of all ages, whilst 64% worked with a specific age group. In most cases this was with young men/boys as children, teenagers, or aged between 18 and 25; however, some did work with men aged 50 and over, for example. Other respondents simply specified here that they worked with adult men.

-

69% of respondents worked with men and/or boys and women and/or girls, whilst 22% worked predominantly with men and/or boys, and 12% worked exclusively with men and/or boys.

-

69% of participants worked with men and/or boys from all ethnic groups, whilst 33% said that they worked mainly with a specific ethnic group (this was typically white British men/boys, presumably because of the demographics of their local area).

-

14% worked with men and/or boys from a specific faith group – specifically Christianity or Islam.

-

67% worked with men and/or boys from all social classes, whilst 34% mainly worked with men and/or boys belonging to a specific social class (mostly working-class) although in some cases (for example, for a university lecturer) this was middle-class men and/or boys.

-

8% of the sample worked specifically with gay, bisexual and/or transgender men and/or boys.

-

13% of respondents worked specifically with men and/or boys with disabilities.

-

The respondents were doing work with men and/or boys across all the different regions of the UK[footnote 4], with the majority (20%) based in North East England (which was perhaps unsurprising, given that this is where the research team was located).

3. Review of existing literature

There has been growing public attention and debate in recent years around issues and ideas of men and masculinities, perhaps in particular regarding the notion of ‘toxic masculinity’ (Flood, 2018). This is a term which is commonly used in media and popular discourse in relation to social problems potentially arising from traditional, restrictive and harmful gender norms and expectations for men and boys: for example, that they should be tough, active and dominant.

Meanwhile, researchers have been trying to understand the impacts that socially constructed ideas and norms around gender have on men and boys and, in turn, other people in their lives for several decades. This chapter will explore some of this research further and discuss the key findings from our rapid evidence assessment of the literature in relation to the research questions.

3.1 How are gendered social norms formed and enacted for men and boys?

A long-standing perception about gender norms is that they reflect generally agreed social consensus about particular gender roles, which children are then socialised into by different institutions within society. However, according to Connell and Pearse (2014) research suggests there is no clear consensus in society about these values and norms. Indeed, there are significant differences within societies, for example between social classes, rural and urban groups, between ethnic and religious groups, between generations, and importantly, between women and men.

Furthermore, rather than children merely being passive ‘sponges’ of cultural values and norms, research indicates that gendered practices are largely ‘produced’ through active, non-linear processes of social interaction (Connell, 2005).

Connell’s (2005; 2009) work has been particularly influential in shifting the focus away from ‘masculinity’ as a singular formation towards the idea of diverse ‘masculinities’ as plural, dynamically interacting with other social divisions such as ethnicity, class, culture, faith, disability, and sexual orientation. She argues that ‘masculinities’ can be understood as collective as well as individual experiences and practices, conditioned and sustained by the cultures, values and norms within particular groups or institutions (for example, schools, workplaces, the army, prisons, sports clubs, religious communities). In any given context a certain version of masculinity becomes dominant (‘hegemonic’) over other subordinated versions (Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005).

Within a school, for example, a range of different ways of ‘doing’ masculinity can be identified – but there will probably be one model that is more powerful than others, to which all boys aspire or are affected by to some degree (Robb, 2007).

However, Mac and Ghaill and Haywood (1994; 2012) have argued that there are other ways of understanding masculinity that are not based on hegemony and dominance. For them, boys (and, to a lesser extent, young men) might be understood more as ‘becoming’ men and having identities that are far less ‘stable’ than their older counterparts as they try to make sense of how they fit into the world around them. Whilst, at times, their identities seem rigidly hyper-masculine, in other contexts they are considerably more flexible. Similarly, Anderson (2009) has proposed that contemporary masculinities are much more fluid, flexible, and open – especially in relation to sexual orientation – than previous research has suggested.

3.1.1 Gender norms as defined by the ‘Man Box’

One influential way of understanding masculinity is the idea of the ‘Man Box’ (Kivel, 2007); this refers to a set of rigid and constraining norms or beliefs, communicated directly or indirectly by families, peers, education, the media, and other members of society, that place pressure on men to be a certain way (and are also harmful for women). These dictate that men should: be self- sufficient; act tough; look good; stick to rigid gender roles (for example, around housework and caregiving); be heterosexual and homophobic; display sexual prowess; be prepared to use violence; and control household decisions and women’s independence (Kivel, 2007).

Based on this framework and survey data from the US, UK and Mexico, a report by Promundo (Heilman, Barker and Harrison, 2017) found that in the UK sample of 1,225 young men aged 18- 30, over half agreed that social norms include the expectation that men will act strong (64%), be the primary earner (56%) and not say no to sex (55%). Less than half agreed that norms for men include non-involvement in household work (45%) and using violence to get respect (40%). Other findings were more contradictory. For example, on homophobia, although just under half (49%) agreed that society tells them “a gay guy is not a ‘real man’”, two-thirds (66%) agreed that society tells them friendships between heterosexual and gay men are ‘normal’. Meanwhile, more than half (56%) agreed that there is a social norm that “men should really be the ones to bring money home to provide for their families, not women”, and just under half (46%) agreed that society tells them “it is not good for a boy to be taught how to cook, sew, clean the house or take care of children”.

This study suggests that although young men believe some traditional masculine norms – for example, around acting tough, being a breadwinner, being sexually active – endure, they may also be identifying with more egalitarian norms in the home, and less punitive approaches towards homosexuality. The study shows that young men’s own views of masculinity are more progressive overall than the social norms they perceive (Heilman, Barker and Harrison, 2017). For instance, in the UK sample, only 39% had the opinion themselves that men should be the primary earner, and only 27% agreed that a husband should not have to do housework. Nevertheless, although the participants often appeared to reject aspects of the Man Box, around a third still endorsed patriarchal notions that “A man should always have the final say about decisions in his relationship or marriage” (33%) and that “If a guy has a girlfriend or wife, he deserves to know where she is all the time” (37%) (Heilman, Barker and Harrison, 2017).

The Man Box survey was expanded with qualitative data and focus groups, including in England, which highlighted that young men experience pressure to conform to dominant masculine stereotypes, but increasingly also express scepticism towards and detachment from them (Robb, Ruxton and Bartlett, 2017; Robb and Ruxton, 2018). As in the overall study, the majority of young men believed in the importance of treating women as equals. But many still held on to traditional norms about gender roles, seeing men as ‘breadwinners’ or ‘protectors’ and women as ‘carers’.

There was also a definite sense that many young men still endorse stereotypical ideas about heterosexual relationships. Meanwhile, a minority believed that gender equality had gone ‘too far’ and that they, as young men, were now at a disadvantage.

A common and noteworthy feature in survey data is that men’s attitudes to gender are consistently less progressive than women’s (Flood, 2015a). British Social Attitudes surveys have found over many years that traditional views of gender roles in the UK continue to decline, in line with changing social norms (Scott and Clery, 2013), and views on gender roles are increasingly becoming more progressive, as indicated by the 2017 survey (Phillips and others, 2018):

-

Less than one in 10 (8%) agree that “a man’s job is to earn money”, and “a woman’s job is to look after the home and family”, while over 7 in 10 (72%) disagree with this statement.

-

However, women are more likely than men to disagree with traditional gender roles (74% compared with 69% for men).

-

Women (30%) are also less likely than men (36%) to favour a mother of pre-school children staying at home.

However, it is important to take into account that whilst surveys may indicate changes in attitudes, this does not necessarily equate to changes in behaviour.

3.2 How do gender norms vary by demographic?

Theories of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) highlight how various socially and culturally constructed categories such as gender, race, class, disability and sexual orientation interact on multiple and often simultaneous levels, contributing to and multiplying the impacts of systemic social inequalities. A significant theme within research on masculinities is the dynamic interrelationships between these different strands of men’s lives. An important insight of an intersectional approach to men and masculinities is that all men are located in multiple relations of privilege and disadvantage (Flood, 2019).

It is, therefore, important to avoid approaching men and boys as if they are a monolithic or homogenous group, when their experiences and practices are likely to differ considerably depending on their intersecting positions in society (Baker, 2013; Miedema and others, 2017). This can also complicate conversations about power, given that many men may simultaneously receive gendered privilege whilst experiencing inequalities in other ways. It is therefore vital to take these intersectional differences into account when engaging with men and boys, to ensure that the approach adopted is relevant to the target audience (Peretz, 2017). Peretz points out that research around men and masculinities can often treat white, heterosexual, middle-class young men as the default and fail to consider how different aspects of men’s identities and social locations can shape their experiences and practices in addition to gender.

3.2.1 Boys and young men

For boys and young men, the impact of gender norms on their attitudes and behaviours is evident as they develop and begins from a very early age. The Fawcett Society Commission on Gender Stereotypes in Early Childhood has highlighted that when children are born, they are unaware of gendered expectations and attitudes (Culhane and Bazeley, 2019). However, by the age of and others most children are conscious of the social relevance of gender (Martin and Ruble, 2004), and by the time children reach the end of primary school, they have already developed a clear sense of what is expected of boys and girls and how they are supposed to behave (Bian and Cimpian, 2017).

These expectations are reinforced in various ways. Parents often create a ‘gendered world’ for young children by providing different play environments, toys, and clothing for boys and girls. They also tend to have gendered ideas and expectations about their children’s abilities (Our Watch, 2018). School and nursery practitioners report that they often unknowingly treat children differently based on gender (National Union of Teachers, 2013). Children and young people also have the tendency to ‘police’ one another, ridiculing those who behave in ways that do not conform to certain gender norms and rewarding gender-typical behaviour (Reigeluth and Addis, 2016), including at pre-school age (Martin and others, 2013).

Research has also identified that consumer goods aimed at children continue to be marketed in gender-specific ways (Committee of Advertising Practice, 2018). The Fawcett review concludes that gender stereotypes limit children by presenting them with a specific set of acceptable behaviours, and experiences of early gender bias have potentially damaging long-term effects in terms of development, attainment, wellbeing, occupational segregation and the gender pay gap (Culhane and Bazeley, 2019).

An influential study in London secondary schools by Frosh, Phoenix and Pattman (2002) suggested that boys aged between 11 to 14 have sophisticated understandings of the contradictions involved in negotiating masculine identities. Boys defined themselves in large part in terms of their difference from girls and policed each other’s identities by constructing certain other boys as transgressing gender boundaries and thus as ‘gay’. Dominant norms of masculinity appeared to involve ‘hardness’, sporting prowess, ‘coolness’, and casual treatment of schoolwork which could in turn have a detrimental impact on academic performance. The boys were aware of the negative ways they were often seen, which often created resentment in them. ‘Having a laugh’ was a way of being a boy in relation to adult authority and classroom learning and was part of an oppositional culture around which social status could be constructed. Conscientiousness and commitment to work were, in contrast, feminised. However, many of the boys also expressed anxieties about impending exams and what grades they would achieve.

A study by Hartley and Sutton (2013) suggests that, from a young age, children believe that boys are academically inferior to girls and that adults think this too – and these negative academic stereotypes about boys can lead to self-fulfilling consequences. Meanwhile, research by Stahl (2016) has found that working-class boys often exclude themselves from school agendas of university entrance and social mobility. Instead, they internalise their potential academic failure, and prefer employment that is viewed as ‘respectable working-class’, such as a recognised trade.

A study by McDowell (2003) highlighted that employment often appears to be central to the self- esteem and development of young white male working-class school leavers. She found that young men’s views of masculinity in some ways conformed to the notion of a ‘lad’ but also emphasised domestic conformity. Whilst their attitudes and behaviours were varied and complex, the study revealed the continued dominance of a ‘traditional’ masculinity, rather than a new version more in tune with the requirements of a service-based economy which might, for example, require more emotional, communication and caring skills. Virtually all these young men adhered to conventional masculine aspirations and markers of adult status, such as employment, an independent home and a family.

However, based on interviews with working-class boys in the retail sector, Roberts (2013) argues that the habitual narrative that young working-class men perform poorly at school and would rather not work in the ‘feminised’ service sector is simplistic. Some at least enjoy the emotional labour in this setting, and not all are attracted to ‘protest masculinity’ in other spheres. Meanwhile, through ethnographic research with young working-class men in the South Wales valleys, Ward (2015) found that the norms of masculinity the young men in his study sought to conform to often had damaging effects, not least for themselves. There was no readily available script for being a young working-class man in what they saw as the feminised world of education, and their inability to create a viable alternative script was holding them back. Those who did adapt best to full-time education post-16 were likely to leave the valleys and create a new life elsewhere.

Young fathers, in particular those from disadvantaged backgrounds, are most at risk of becoming disengaged from parenting responsibilities; they are often characterised as ‘irresponsible’ or ‘feckless’ and viewed with distrust by service providers (Ashley and others, 2006). Some young single fathers may experience praise by virtue of being a lone male parent, but this is a minority experience (Hirst, Formy and Owen, 2006). However, many voice a desire for information, advice and inclusion (Quinton, Pollock and Golding, 2002). Recent research suggests that despite countless obstacles and difficulties, young fathers are typically committed to their children and striving to ‘make a go’ of parenthood (Neale and Davis, 2015). Indeed, the experience of becoming a father can itself be a catalyst for helping young men to leave behind a troubled past (Robb and others, 2015). Although some young men have experienced difficult or unsatisfactory relationships with their fathers, most aspire to be fathers themselves, and take that role seriously, often expressing a desire to be a different and more engaged kind of father (Robb and Ruxton, 2018).

3.2.2 Ageing men

Among older men, there is considerable diversity in experiences, with an increasing split between, for instance, affluent early retirees and low-paid men working beyond retirement age. Although the socioeconomic status of older men tends to be higher than that of older women, some groups of men, such as those living alone and/or without partners, are particularly prone to loneliness and social isolation (Beach and Bamford, 2013; Willis and others, 2019). For older men, the dominant discourse of young, active, virile masculinity is counterposed by the ‘othering’ of ageing masculinities (Jackson, 2007). Ageing men, therefore, face an increasing contradiction between their desire to live up to masculine norms of independence, self-reliance and strength, and the reality that they are less able to do so (Ruxton, 2007). Many older men may, therefore,` experience a sense of marginalisation through bodily fragility and loss of sexual potency (Jackson, 2016).

This contradiction is underpinned by widespread gender stereotyping and ageism that undervalues older people’s lives, which research suggests can leave them feeling isolated and excluded from opportunities (Abrams, Eilola and Swift, 2009). This is generated and reinforced in a number of ways, including: negatively framed headlines in the media, lack of regular contact between older and younger generations, and age-based prejudice in the workplace (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and Royal Society for Public Health, 2018). Older men tend to be depicted on the one hand as displaying ‘diminished masculinity’; as sedentary, passing time, asexual. On the other hand, they are often portrayed as ‘grumpy old men’, miserable, moaning, and boring (Barber and others, 2016). For many older men, their relationship with employment and the workplace is central to their identity; this raises a dichotomy for some between their long-standing view of themselves as ‘productive’ breadwinners, and their self-image in older age of becoming ‘unproductive’ dependents (Ruxton, 2007).

Conforming to restrictive notions of masculinity often results in men avoiding certain behaviours that they take to be ‘non-masculine’. In particular, older men are seen as reluctant to admit to having problems, displaying emotions, or seeking assistance from others. Many are less likely to recognise or acknowledge conditions such as depression, substance abuse, or stressful life events (Kosberg, 2005). They frequently regard visiting the doctor as a sign of weakness and tend to postpone getting appointments – unlike older women, for whom visits to the doctor may have been a more regular feature of their lives (owing to pregnancy, childcare etc). Older men are also less likely than women to use existing care services, due to traditional notions of male independence and self-reliance, and the ‘feminised’ feel of much provision (Davidson and Arber, 2003). Research suggests that these are likely to be factors contributing to men having a lower life expectancy than women (Springer and Mouzon, 2011).

However, these perceptions can also render invisible the hidden realities of many older men’s economic and social contributions, for instance as carers for ill partners, active nurturing grandparents, and campaigners on issues such as the environment. They may also hide the ways in which some older men are already engaging with diverse, grassroots community activities and organisations, such as ‘men’s sheds’, which can have important benefits for their health and wellbeing (Golding, 2011). Moreover, by portraying older men’s lives as fixed and static, such stereotypes underplay the dynamic shifts and disruptions that many encounter (for example, illness, deaths, grandfathering, new relationships) (Robinson and Hockey, 2011). Although some men cling on to earlier identities and refuse to acknowledge increasing fragility, life changes can help others to move beyond obsessive concerns with work, success, competition and achievement.

Jackson (2016) argues that time for self-reflection and stock-taking can result in a new concern for caregiving and a desire to participate actively in emotional work.

3.2.3 Norms in relation to gay, bisexual and/or transgender men

According to a series of British Social Attitudes surveys, the British public has become increasingly accepting of same-sex relationships, especially since the introduction of same-sex marriages in 2014 (Swales and Taylor, 2016). The proportion saying that same-sex relationships are ‘not wrong at all’ is now a clear majority at 66% (Albakri and others, 2019). This suggests a society- wide shift in normative perceptions towards LGBT people. However, this liberalisation of attitudes towards same-sex relations (and also towards premarital sex) appears to be slowing down – with the aforementioned 66% figure actually representing a decrease for the first time, from 68% in the 2017 Social Attitudes Survey (Albakri and others, 2019). Meanwhile, the 2016 survey found that only 53% condemn transphobia completely (Swales and Taylor, 2016). Women were more likely than men to condemn prejudice against transgender people (58% of women say it is “always wrong” compared with 46% of men). Yet the relatively low levels of people with overtly-stated prejudice contrasts with the high proportions of transgender people who report facing regular harassment and intimidation. Furthermore, many respondents who said they were not transphobic went on to say that transgender people should not be able to have certain jobs, such as being a police officer or teacher (Swales and Taylor, 2016).

Whilst public attitudes appear to be becoming more accepting in some ways, the lives of gay, bisexual and/or transgender men, themselves, remain structured by their experiences in a dominant heteronormative culture and, in particular, by homophobia, biphobia and transphobia (Stepelmen, 2007). For instance, the GEO (2018) National LGBT Survey[footnote 5] found that at least and others in 5 respondents had experienced an incident such as verbal harassment or physical violence because they were LGBT in the last 12 months, and a 2017 Stonewall report on hate crime and discrimination found similar patterns (Bachmann and Gooch, 2017). This prejudice and discrimination may often be rooted in the notion that LGBT people are somehow failing to live up to dominant gender norms and expectations.

Despite the seeming endurance of homophobia, Anderson’s (2009) ‘inclusive masculinity’ theory contrasts with earlier studies which argued that hostility to homosexuality was a key element in the formation of young masculine identities (Nayak and Kehily, 1997). McCormack (2012) explored the lives of a group of young, white, mainly middle-class students at sixth form colleges in England, finding similarly that they were more likely to have pro-gay attitudes, and to have friendships with students who were openly gay. Other research has suggested that the use of homophobic language – though still widespread – may be decreasing in some school contexts (White and Hobson, 2015; Bradlow and others, 2017). However, it has been observed that ‘softer’ forms of masculinity can co-exist alongside ‘harder’ forms (Segal, 2007). Some scholars argue that rather than a new form of masculinity replacing previous versions, this ‘hybridisation’ only represents a shift in the practices of certain (relatively privileged) young men, and that homophobic aspects of dominant masculinities are transforming rather than disappearing (Bridges, 2014). For other (especially marginalised) young men, there is evidence that change is slower, and some struggle even to discuss the issue of homosexuality (Robb, Ruxton and Bartlett, 2017).

Gay, bisexual and/or transgender men have just as varied and diverse experiences and enactments of gender norms as other men, and these are also like to be shaped by their positions in relation to other social categories. There are many unique forms and expressions of masculinity which have developed within LGBT communities. However, many gay, bisexual and/or transgender men are likely to also be influenced by wider societal expectations of gender to some degree. For instance, some may seek to disassociate themselves from femininity, and men perceived as ‘feminine’ may experience marginalisation within the LGBT community. For some men, they may seek to ‘queer’ masculinities (bring dominant norms into question by applying a different lens to them and blurring and troubling traditional boundaries and expectations), whilst others may attempt to construct their own affirming sense of masculinity which still to some extent meets with hegemonic gender expectations. Many gay, bisexual and/or transgender men may experience a degree of conflict between, on the one hand, wishing to or feeling pressured to conform to dominant masculine norms, whilst also having an awareness of the limitations of these, or of how they, themselves, have also experienced marginalisation as a result of those same norms (Sánchez and others, 2010; Wilson and others, 2010).

3.2.4 Men from ethnic minority groups

Another critical research strand is the position and experience of men and boys from ethnic minority backgrounds. Issues facing men from ethnic minority groups overlap with those facing other men (indeed, some may have ‘multiple memberships’ of minority and majority communities), and for many men their cultural and religious identities are likely to play a part in shaping their construction of masculinity. Many ethnic minority men in the UK are also affected by a complex mix of racism, discrimination, and educational and social disadvantage. Yet the ways these experiences play out in practice vary considerably between different groups.

For instance, research suggests that men from African and Caribbean backgrounds are over- represented in the use of mental health services (Keating, 2007; Khan and others, 2017). In 2012, detention rates under the Mental Health Act were 2.2 times higher than the average for people of African origin and 4.2 times higher for those of Caribbean origin. In a survey of median hospital admission periods, the median number of days Black Caribbean men spent in psychiatric hospitals was more than twice the number spent by people of White British origin (Time to Change, 2016). Meanwhile, in a survey of people from minority ethnic groups with mental health problems, 28% of Black Caribbean and 31% of African respondents reported that they had directly experienced racism within services over the last 12 months (Rehman and Owen, 2013).

For African and Caribbean men, the route to services disproportionately takes place through the police and criminal justice system, and they are more likely to experience controlling service responses (Time to Change, 2016). There are a number of potential factors behind these figures, including an increased likelihood of experiencing poverty, housing insecurity and homelessness, difficulties at school and subsequent reduced access to opportunities (Ruxton, 2009; Khan and others, 2017). However, Khan and others (2017) argue that experiences of racism have a particularly significant influence on the mental health of Black boys and young men, such as through negative and demonising media representations, that can ‘wear down’ their resilience as they grow up.

These representations and racist assumptions may be shaped in part by particular gendered stereotypes about Black men and boys.

In a study of discourses within the UK print media, Baker and Levon (2016) point out that representations of masculinity are often highly racialized and classed. They found that Black and Asian men were frequently portrayed as being violent, criminal, and morally and socially deviant, whilst White men were often characterised as being unfairly excluded from society. The study suggests that idealised perceptions of masculinity are frequently associated with White men, and that race plays an important role in shaping the dynamics of hegemonic and subordinate forms of masculinity. Meanwhile, specific groups of ethnic minority men may be blamed or scapegoated for issues connected to masculine norms more broadly, such as child sexual abuse and exploitation, ‘othering’ the problem in the progress (Tufail, 2015). There has also been significant focus placed on ‘father absence’ among Black and ethnic minority fathers in the UK. However, research suggests that non-resident fathers often still contribute to their children’s lives in other ways, and have an active involvement in parenting (Phoenix and Husain, 2007; Reynolds, 2009).

3.2.5 Men with disabilities

Despite important legislative changes to tackle discrimination against disabled people, negative stereotypes persist. In a recent survey, one in 3 (32%) disabled respondents said that there is a lot of prejudice against disabled people in Britain; non-disabled people gave a somewhat different response however, with just one in 5 (22%) agreeing (Dixon, Smith and Touchet, 2018). Attitudes to those with less ‘visible’ disabilities (such as mental health conditions or learning disabilities) are more negative than to those with more ‘visible’ disabilities (physical or sensory disabilities). Men aged 18-34 are the group least likely to interact with disabled people and most likely to hold negative attitudes towards them (Aiden and McCarthy, 2014). Women are generally seen as exhibiting less prejudice towards disabled people than men (Robinson, Martin and Thompson, 2007).

Men with disabilities often live their lives in ways that contradict dominant norms of masculinity, as can sometimes also be the case with older men. They are often unwilling or feel unable to live up to ‘ideal’ models of masculinity based on body strength and performance (Shakespeare, 1999; Gerschick, 2005; Ruxton and van der Gaag, 2012). Masculine standards and expectations – for example, that they are not allowed to ‘fail’ and must be ‘strong’ and ‘tough’ – can be at odds with the reality of life for disabled men. Masculinity and disability are thus frequently in conflict with each other, with disability associated with being dependent and helpless, whereas masculinity is associated with being powerful and autonomous (Shuttleworth, Wedgwood and Wilson, 2012).

Furthermore, if labour markets, health and education systems exclude or marginalise disabled boys and men, as is often the case, then they are unlikely to be able to achieve masculine expectations around being breadwinners and career-builders. If norms of masculinity stereotypically entail having power over women, then how can disabled men be understood if they are receiving large amounts of care and support from women in everyday life (Abbott and others, 2019)?

The main focus of research in this field has been on how masculinity intersects with disability as a generic category, rather than with specific types of impairment (Shuttleworth, Wedgwood and Wilson, 2012). However, some research has begun to address this issue. For example, Wilson and others (2012) have documented how men with learning disabilities are often represented negatively, in terms of a propensity for violence and sexual aggression, rather than the positive experiences that they may derive from homosocial camaraderie, physical activity and sexual expression (Barrett, 2014). More recently, in a study with men who have Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Abbott and others (2019) found that men with disabilities of this kind can often be denied an adult identity and infantilised, as assumptions are made about their cognitive and physical capacities.

3.3 What impact do gendered social norms have on the behaviour of men and boys in the UK?

Promundo’s ‘Man Box’ study (discussed in section 3.1.1) found that over half of young men in the UK (52%) perceived that their parents, society, or partners think that men should aspire to the constraining norms of the ‘Man Box’, and high percentages of young men were also found to have internalised these norms (38%) (Heilman, Barker and Harrison, 2017). The study found that the stronger young men’s stated belief was in those norms, the more likely they were to show several negative behavioural outcomes. It concludes that men who adhere closely to the rules of the Man Box are more likely to put their health and wellbeing at risk, to cut themselves off from intimate friendships, to resist seeking help when they need it, to experience depression, and to think more frequently about ending their own life.

These findings concur with those of other international studies, which show that men who endorse dominant masculine norms tend to have more risky lifestyles and worse health outcomes (Courtenay, 2000). One recent meta-analysis highlighted that conformity to masculine norms is associated with poor mental health (Wong and others, 2017). According to the Promundo study, young men inside the Man Box are also more likely to use violence, both against women and against other men, and to have experienced violence themselves (Heilman, Barker and Harrison, 2017). A follow-up to this research estimates that the harmful masculine norms that make up the Man Box cost the UK economy at least £3.1 billion per year, based on 6 key cost categories: bullying and violence, sexual violence, depression, suicide, binge drinking and traffic accidents (Heilman and others, 2019).

One difficulty in assessing the impact of gender norms on behaviour is that evidence of the existence of a norm in a particular context is often taken, erroneously, to explain the extent to which that norm sustains a particular practice (Cislaghi and Heise, 2018a). Various hypotheses have been put forward to explain what determines the strength of a norm. A review by Chung and Rimal (2016) highlights the need to consider whether a behaviour is enacted spontaneously or after reflection, with norms likely to be more directly influential in the former case. Meanwhile, Cislaghi and Heise (2018a) suggest that the characteristics of a practice (for instance, whether it is ‘detectable’) can affect the influence a norm might exert.

Another difficulty in analysing the impact of gender norms on behaviour is that social norms are rarely the only drivers behind harmful practices (Kwasnicka, 2016; Grant, 2017). A range of models have been developed to explain the various factors that affect behaviour. One of the most commonly cited is the ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), which has been adapted by Cislaghi and Heise (2018b) as a framework for developing social norm change interventions. They highlight 4 overlapping domains of influence (institutional, material, social and individual), and argue that understanding how these factors interact to influence people’s harmful practices can help practitioners design effective interventions that include a social norms perspective (Cislaghi and Heise, 2018a). Similarly, Connell and Pearse (2014) analyse how norms and stereotypes are materialised in social life, highlighting the role that key sites such as media, work, organisations, and education play in this process.

For example, media representations of men and masculinities ranging from magazines, to TV shows, to self-help books, to films, influence understandings of what being a man is about (Gauntlett, 2008). Easy access to pornography online regularly presents women as sexual objects, and (heterosexual) masculinity as “playfulness, flight from responsibility, detached and uninhibited pleasure-seeking and the consumption of women’s bodies” (Gill, 2007). Recent years have also seen the explosion of misogynistic abuse online, often directed at women who are prominent in public life (Lewis, Rowe and Wiper, 2016). However, there is evidence that people are selective in their readings of the normative messages contained in TV and other forms of popular culture (Connell and Pearse, 2014), and the relationship between images, norms and behaviour is not straightforward. For instance, focus group research with young men identified that whilst they continue to experience pressure to conform to particular gender stereotypes, many perceived that images of masculinity promoted in the media and elsewhere were so remote from their own lives as to be irrelevant (Robb, Ruxton and Bartlett, 2017).

Recently, the Committee of Advertising Practice (2018) has produced guidance for advertisers on the depiction of gender stereotypes, arguing that there is a wide body of evidence indicating that these can negatively reinforce how people think they and others should look and behave. The Committee’s review (Advertising Standards Authority, 2017) suggests that stereotypes implying that men should be physically strong, unemotional and family breadwinners are limiting and potentially damaging. There are also strong indications that men and boys are increasingly experiencing harm as a consequence of pressure to achieve a certain ‘masculine’, muscular body image – reflecting the longstanding pressures experienced by women and girls (Reardon and Govender, 2011). However, in recent years, some companies have also started to challenge norms of masculinity through advertising, such as with Gillette’s ‘The Best Men Can Be’ campaign.

Gender norms are also interrelated with economic change and workplace cultures (Pearse and Connell, 2016). For instance, new patterns of managerial or ‘transnational business’ masculinity have emerged among men with positions of power in global corporations (Connell and Wood, 2005). These patterns are marked by an extreme commitment to work and competitive achievement, strong division between home and working life, and a declining sense of responsibility for others. However, workplaces may be more or less ‘gendered’ in the ways they are organised and structured, and this will significantly affect the shifting and dynamic gender relations within them. Organisational structures, cultures and practices tend still to be based on an assumed masculine norm of lifetime, full-time, continuous (male) employment. ‘Masculine’ values are also strongly embedded within many organisations, with men exercising power over women in the workplace in a variety of ways (for example, job segregation, sex discrimination, the gender pay gap, sexual harassment) (Collinson and Hearn, 2004).

Norms of femininity associating women with being caring, self-sacrificing, and industrious contribute to women most often being employed in (lower-paid) service industries, or caring professions (for example, teaching and nursing). Women also continue to do most unpaid domestic and care labour (Connell and Pearse, 2014). Whereas men are over-represented in management, financial, legal, and technical workforces, female managers who attain senior levels are required to act in more masculine ways, working long hours, and delegating, like male managers, domestic responsibilities for childcare, cooking, and housework (Wajcman, 1999). A common and growing feature of the contemporary economy is job insecurity and precarity, with workers increasingly offered short-term or zero-hours contracts rather than a ‘job for life’. For many men, the lack or loss of a job, earning power and/or status can represent a significant challenge to their sense of their role and entitlements as men (Nolan, 2005).

3.3.1 Relationships