Autumn Budget 2017

Published 22 November 2017

1. Executive summary

The United Kingdom has a bright future. The fundamental strengths of the UK economy will support growth in the long term as the UK forges a new relationship with the European Union (EU). The Budget prepares for that: supporting families and business in the near term; setting a path to a prosperous, more open Britain; and building an economy that is fit for the future. It demonstrates the government’s commitment to a balanced approach to managing the public finances and supporting key public services. By investing in the future, the Budget will ensure that every generation can look forward to a better standard of living than the one before and ensures young people have the skills they need to get on in life. It backs the innovators who deliver growth, helps businesses to create better, higher paid jobs and builds the homes the country needs.

The Budget sets out actions the government will take to:

-

support more housebuilding, raising housing supply by the end of this Parliament to its highest level since 1970, to make homes more affordable in the long term and help those who aspire to homeownership

-

prepare for exiting the EU and ensure a smooth transition by setting aside an additional £3 billion for government

-

establish the UK as a world leader in new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), immersive technology, driverless cars, life sciences and FinTech

-

give everyone the skills to succeed in the modern economy and get better paid jobs

-

expand the National Productivity Investment Fund (NPIF) to support innovation, upgrade the UK’s infrastructure and underpin the government’s modern Industrial Strategy

-

invest over £6.3 billion of new funding for the NHS to improve A&E services, reducing waiting times and improving performance for treatment after referral, and to transform and integrate patient care

-

provide more support in the short term for households, reducing costs of living, and boosting wages for the low paid through the National Living Wage (NLW)

1.1 Economic context

The UK economy has shown its resilience, with solid growth over the past year and further increases in the number of people with a job. Gross domestic product (GDP) grew 1.5% in the year to the third quarter of 2017, employment remains near the record high set earlier this year and unemployment is at its lowest rate since 1975.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) now expects to see slower GDP growth over the forecast period, mainly reflecting a change in its forecast for productivity growth. It has revised down its forecast for GDP growth by 0.5 percentage points to 1.5% in 2017, then growth slows in 2018 and 2019, before rising to 1.6% in 2022.

Household spending continues to grow, having slowed since 2016 due to higher inflation caused by the depreciation of sterling. Business investment has grown moderately over the past year and net trade has started to make a positive contribution to GDP growth. Surveys of export orders in 2017 have been strong, with some reaching their highest level since 2011.

1.2 Outlook for the public finances

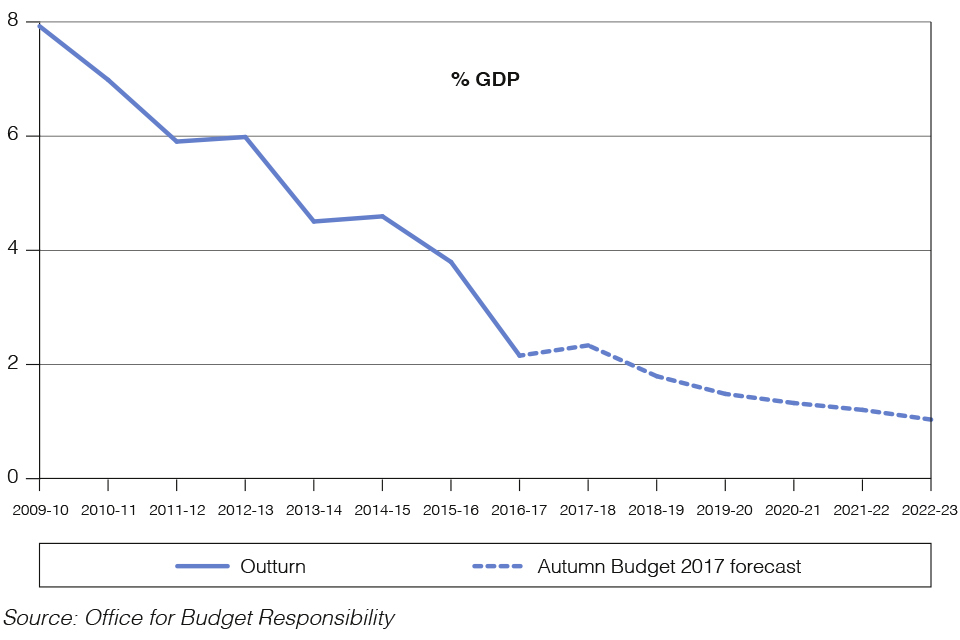

The government has made significant progress since 2010 in restoring the public finances to health. The deficit has been reduced by three quarters from a post-war high of 9.9% of GDP in 2009-10 to 2.3% in 2016-17, its lowest level since before the financial crisis.

The government’s fiscal rules take a balanced approach to government spending, getting debt falling but also investing in our key public services like the NHS, and keeping taxes low.

Compared to the Spring Budget 2017 forecast, borrowing is significantly lower in the near term. However, over the medium term the impact of a weaker economic outlook and the measures taken at the Budget see borrowing higher than previously forecast. The OBR expects the government will meet its 2% structural deficit rule for 2020-21 two years before target, in 2018‑19, and with £14.8 billion of headroom in the target year. Debt is forecast to peak at 86.5% of GDP in 2017-18, and is forecast to fall in every year thereafter to 79.1% of GDP in 2022-23.

1.3 Building an economy fit for the future

The Budget sets out a long term vision for an economy that is fit for the future – one that gives the next generation more opportunities. It is an economy driven by innovation that will see the UK becoming a world leader in new and emerging technologies, creating better paid and highly skilled jobs.

To achieve this vision, the government has already set in train a plan to boost UK productivity over the long term. A key part of this is the NPIF, launched last year to provide additional investment in housing, infrastructure, and research and development (R&D). The Budget goes further, increasing the size of the NPIF from £23 billion to £31 billion. This investment will underpin the government’s modern Industrial Strategy and help raise wages and living standards. It means public investment as a proportion of GDP will reach its highest level in 30 years by 2020-21, excluding the exceptional years following the financial crisis. Further details of the government’s plan will be set out in the Industrial Strategy.

Government action at this Budget to boost productivity includes:

-

Transport: A £1.7 billion new transforming cities fund through the NPIF to improve connectivity and support jobs across England’s great city regions

-

Research and Development: The largest boost to R&D support for 40 years with a further £2.3 billion investment from the NPIF in 2021-22

-

Long Term Investment: Unlocking over £20 billion of patient capital, over the next 10 years so that innovative high-growth firms can achieve their full potential

-

Emerging Tech: Leading the world in developing standards and ethics for the use of data and AI, and creating the most advanced regulatory framework for driverless cars in the world

-

Skills: Creating a new partnership with industry and trade unions to deliver a National Retraining Scheme, giving people the skills they need throughout life to get a well-paid job, and equipping young people with the science, technology, engineering, and maths (STEM) skills to become innovators of the future

1.4 Building the homes our country needs

The government is determined to fix the dysfunctional housing market, and restore the dream of home ownership for a new generation. The only sustainable way to make housing more affordable over the long term is to build more homes in the right places. Government action has already increased housing supply to 217,000 in 2016-17. The Budget goes further and announces a comprehensive package which will raise housing supply by the end of this Parliament to its highest level since 1970s, on track to reach 300,000 per year, through:

-

making available £15.3 billion of new financial support for housing over the next five years, bringing total support for housing to at least £44 billion over this period

-

introducing planning reforms that will ensure more land is available for housing, and that maximises the potential in cities and towns for new homes while protecting the Green Belt

The Budget also announces further support for those struggling to get on the housing ladder now. The government will permanently exempt first time buyers from stamp duty for properties up to £300,000, with purchasers benefiting on homes up to £500,000.

1.5 Supporting people, businesses and the NHS

The Budget takes further steps to put the NHS on a strong and sustainable footing - both now and in the future – with £6.3 billion of additional funding. The government will invest £3.5 billion in capital by 2022-23, to ensure patients receive high quality, integrated care and improve efficiency and productivity. The government will also provide an additional £2.8 billion of resource funding to improve NHS performance and ensure that more patients receive the care they need more quickly. This is a significant first step towards meeting the government’s commitment to increase NHS spending by a minimum of £8 billion in real terms by the end of this Parliament. In addition, the government is committing to funding pay awards for NHS staff on the Agenda for Change contract that are agreed as part of a pay deal to improve productivity, recruitment and retention.

The Budget prepares the UK for the future, but it also recognises there are immediate challenges caused by rising prices. The Budget will boost wages, reduce costs of living, and support businesses by:

-

freezing fuel duty for the eighth year in a row, saving the average driver £160 a year, and freezing alcohol duties

-

providing a further £2.3 billion of support to businesses to reduce the burden of business rates

-

increasing minimum wages, equivalent to a pay rise of £600 per year for a full-time worker on the NLW, and introducing the largest increases in youth rates in 10 years

-

further reducing income tax by increasing the personal allowance to £11,850 and the higher rate threshold to £46,350, in line with inflation

1.6 A fair and sustainable tax system

The government remains committed to a low tax economy, cutting taxes for both working people and businesses to help respond to short term pressures. It has secured £160 billion in additional tax revenue, and these actions have also helped the UK achieve one of the lowest tax gaps in the world at 6.0% in 2015-16. The Budget takes action so that everyone pays their fair share, including those seeking to evade or avoid tax using offshore structures. The Budget will:

-

crack down on online value-added tax (VAT) evasion by strengthening and extending existing powers that make online marketplaces responsible for the unpaid VAT of their sellers

-

provide Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) with additional resources including for new technology to further tackle avoidance and evasion risks

-

increase the time limits for HMRC assessments of offshore tax non-compliance, and support new global rules to force the disclosure of certain offshore structures to tax authorities

As the UK economy evolves, the tax system needs to evolve with it, to ensure that vital public services can be funded sustainably. The Budget sets out the government’s approach to ensuring that digital businesses will pay tax that is fair, given the value they generate.

1.7 Budget decisions

A summary of the fiscal impact of the Budget policy decisions is set out in Table 1. Chapter 2 provides further information on the fiscal impact of the budget.

Table 1: Autumn Budget 2017 policy decisions (£ million) (1)

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total spending policy decisions | -150 | -4,460 | -7,190 | -3,625 | -1,450 | -1,105 |

| Total tax policy decisions | -80 | -1,585 | -2,725 | +310 | -1,510 | -1,415 |

| Total policy decisions | -230 | -6,045 | -9,915 | -3,315 | -2,960 | -2,520 |

| 1 Costings reflect the OBR’s latest economic and fiscal determinants. |

1.8 Government spending and revenue

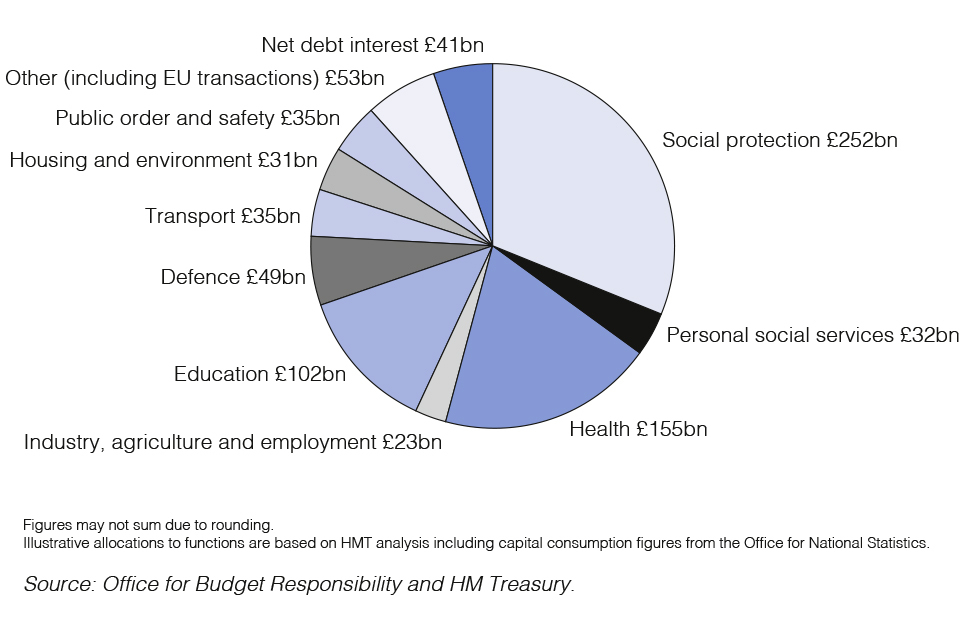

Chart 1 shows public spending by main function. Total Managed Expenditure (TME) is expected to be around £809 billion in 2018-2019.

Chart 1: Public sector spending 2018-19

Chart 1 shows public spending by main function. Total Managed Expenditure (TME) is expected to be around £809 billion in 2018-2019.

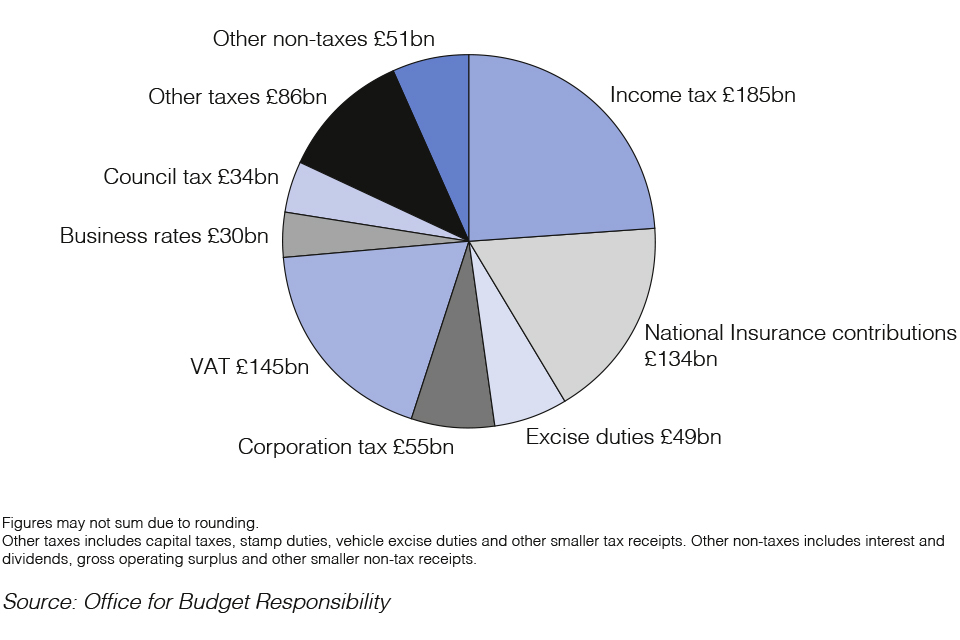

Chart 2 shows the different sources of government revenue. Public sector current receipts are expected to be about £769 billion in 2018-2019.

Chart 2: Public sector current receipts 2018-19

Chart 2 shows the different sources of government revenue. Public sector current receipts are expected to be about £769 billion in 2018-2019.

2. Economy and public finances

2.1 Economic context

The UK economy has demonstrated its resilience over the past 18 months.[footnote 1] Gross domestic product (GDP) growth has remained solid – extending the period of continuous growth to 19 quarters. Employment has risen by 3 million since 2010 and is close to its record high, and unemployment is at its lowest rate since 1975. The increase in employment has supported prosperity across the country and income inequality is at its lowest level in 30 years.

Over the past year, higher inflation has weighed on household income, business investment has been affected by uncertainty, and productivity has been subdued. Productivity growth has slowed across all advanced economies since the financial crisis, but it has slowed more in the UK than elsewhere. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has revised down expectations for productivity growth over the forecast period compared to Spring Budget 2017. There is an opportunity, if the UK can unlock productivity growth, to increase growth, wages and living standards over the long term.

In the near term, the Budget provides support for households and businesses. Over the medium term, the government has already set in train a plan to address the UK’s productivity challenge, by cutting taxes to support business investment, improving skills and investing in high‑value infrastructure. The Budget goes further, building an economy that is fit for the future and ready to take advantage of new opportunities.

2.2 UK economy

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that the UK economy grew by 1.8% in real terms in 2016 and by 1.0% on a per capita basis. The ONS published revisions to the National Accounts in September. While annual GDP growth in 2016 was not revised, there were changes to the quarterly path and composition of GDP that implied a little less momentum at the end of 2016.

In 2017 GDP growth has remained solid, but slowed slightly compared to the previous year. GDP growth was 0.3% in each of the first two quarters of this year and rose to 0.4% in Q3 2017. Services output increased by 0.4% in Q3, slightly stronger than the average pace of growth in the first half of the year, but a bit slower than in 2016. Construction output decreased by 0.9% in Q3, having also fallen by 0.5% in Q2. Production output grew by 1.1% in Q3, driven mainly by manufacturing output, which also grew by 1.1%.

Household consumption underpinned growth in demand last year, growing by 2.8% in 2016, but slowed in the first half of 2017 to an average of 0.3% per quarter. Consumer confidence and retail sales point to further modest consumption growth in the third quarter of this year.

Business investment was previously estimated to have fallen by 1.5% over the course of 2016, but the latest data suggests that the decline was less marked at 0.4% in 2016. Despite the recent revisions, business investment growth remains moderate at 2.5% in the year to Q2 2017, below its average annual rate of 4.9% between 2010 and 2015. Private business surveys cite uncertainty as a factor impeding investment.

In 2016, export and import volumes grew by 1.1% and 4.3% respectively. As a result, net trade subtracted 0.9 percentage points from GDP growth in 2016. Since Q4 2016, export volumes have started to increase, rising by 4.9% in Q2 2017 on a year earlier, above import volumes growth of 3.4% over the same period. Net trade has therefore made a small positive contribution to yearly GDP growth of 0.3 percentage points in the first two quarters of 2017. Surveys indicate that in 2017 export orders have been strong, with some reporting the highest level of orders since 2011.

The ONS published revised data for the current account in September. In 2016, the current account deficit was 5.9% of GDP. The current account deficit narrowed in Q4 2016 and Q1 2017 but widened again to 4.6% of GDP in Q2 2017. The wider current account deficit was driven by a deterioration in the investment income deficit but was partially offset by a narrowing in the trade deficit.

2.3 Productivity, labour market and earnings

In 2016, UK output per hour grew by 0.2%, close to its average since 2008 of 0.1% but well below its pre-crisis trend of 2.1% in the decade before (see Box 1.1 for further details). Productivity has remained subdued this year, falling in the first two quarters, but rising in Q3, pushed up by lower total hours worked.

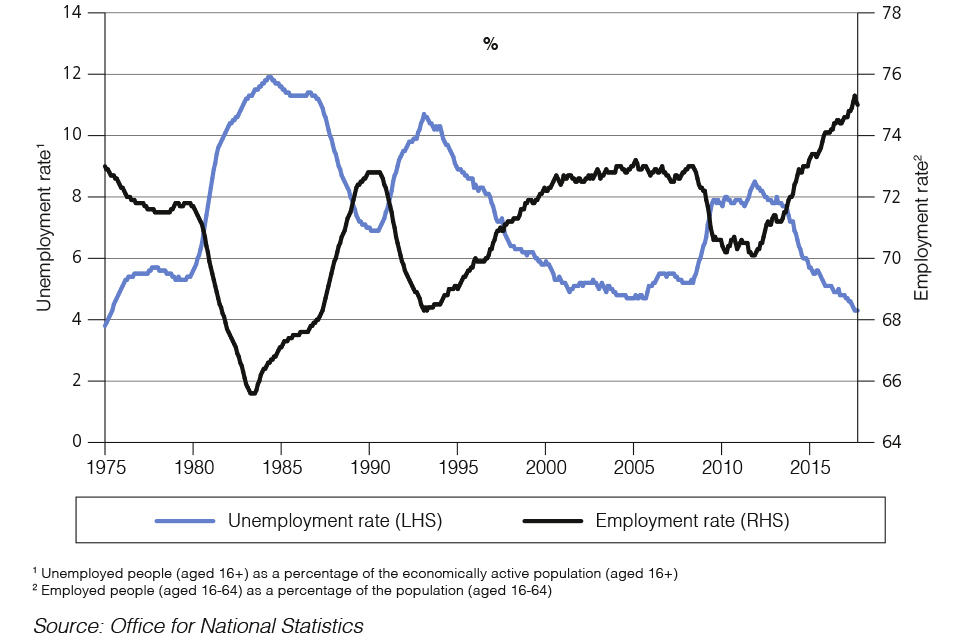

Chart 1.1: Unemployment and employment rates since 1975

Chart 1.1: Unemployment and employment rates since 1975

The UK labour market continues to perform well. The number of people in work has risen over the last year; the employment rate was 75.0% in the three months to September 2017, close to the record high set earlier this year; the level of female employment is close to a record high at 15 million; and over the past year, higher employment has been accounted for by rising full-time employment. The unemployment rate has continued to fall since the last Budget and now stands at 4.3% – the lowest since 1975 (Chart 1.1). Since 2010, 75% of the fall in unemployment has come from outside London and the South East. The biggest falls in unemployment rates since 2010 have occurred in Yorkshire the Humber and Wales. There are also 954,000 fewer workless households since 2010.

Box 1.1: Productivity – a long-term challenge

Productivity is the amount of output produced per hour worked. Improving productivity benefits the whole of the UK economy. It enables workers to produce more for the same number of hours worked. This in turn raises profits for companies and benefits households, as firms can pay higher wages and offer goods and services at lower prices.

Employment has risen to near record levels in the UK, accounting for the bulk of GDP growth since 2010 (Chart 1.2), and the government has supported living standards through raising the personal allowance and introducing the National Living Wage. However, raising wages over the long term requires improvements in productivity (a).

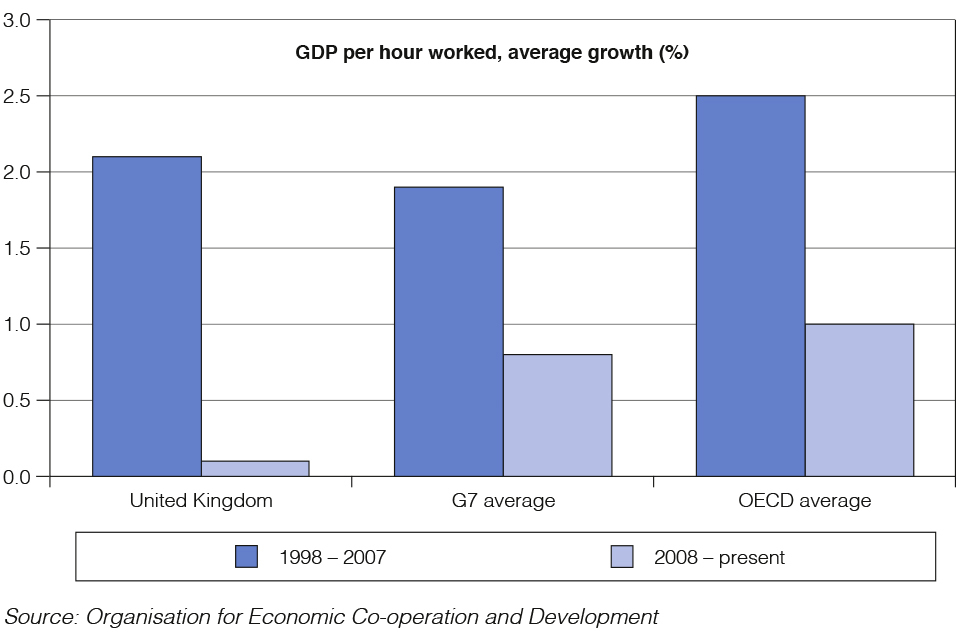

Productivity growth has slowed around the world. In over two thirds of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, annual productivity growth has been at least 1 percentage point slower since 2008 than in the preceding decade. In the UK, however, the slowdown has been more acute; productivity growth has averaged 0.1% since 2008, compared to 2.1% in the decade prior (Chart 1.3).

Historically, UK productivity has been below other advanced economies. This gap predates the financial crisis, but has widened since 2008. Raising productivity growth above the post-crisis average and closing the gap would generate significant improvements in living standards.

Chart 1.2: Contributions of productivity and labour to GDP growth

Chart 1.2: Contributions of productivity and labour to GDP growth

Chart 1.3: Average annual productivity growth

Chart 1.3: Average annual productivity growth

Evidence suggests the UK should prioritise upgrading infrastructure, improving skills, helping businesses to invest, and reforming the housing and planning systems (b). The government has already made significant progress: increasing public investment in infrastructure and innovation, enhancing skills and delivering a competitive tax regime to support business investment.

The Budget goes further. It invests in infrastructure and RD, ensures the UK is a world leader in new technologies, takes steps to transform lifelong learning and increases housing supply. Productivity is a long-term issue and these reforms will take time to have an impact. Taken together, they represent a significant step towards improving the UK’s productivity, in order to boost wages and enhance people’s living standards.

a ‘Spring Budget 2017’, HM Treasury, March 2017.

b See ‘Fixing the foundations: creating a more prosperous nation’, HM Treasury and Department for Business, Innovation Skills, July 2015.

Both total pay (including bonuses) and regular pay (excluding bonuses) rose 2.2% in the three months to September compared with the same period a year earlier. Earnings growth for workers in lower paid jobs has been supported by the introduction of the NLW. The lowest earners saw their real wages grow strongly, by almost 7% in the last two years. With inflation rising, real household disposable income (RHDI) per head has fallen in recent quarters compared to a year earlier but remains 3.6% higher in Q2 2017 than at the start of 2010.

2.4 Prices

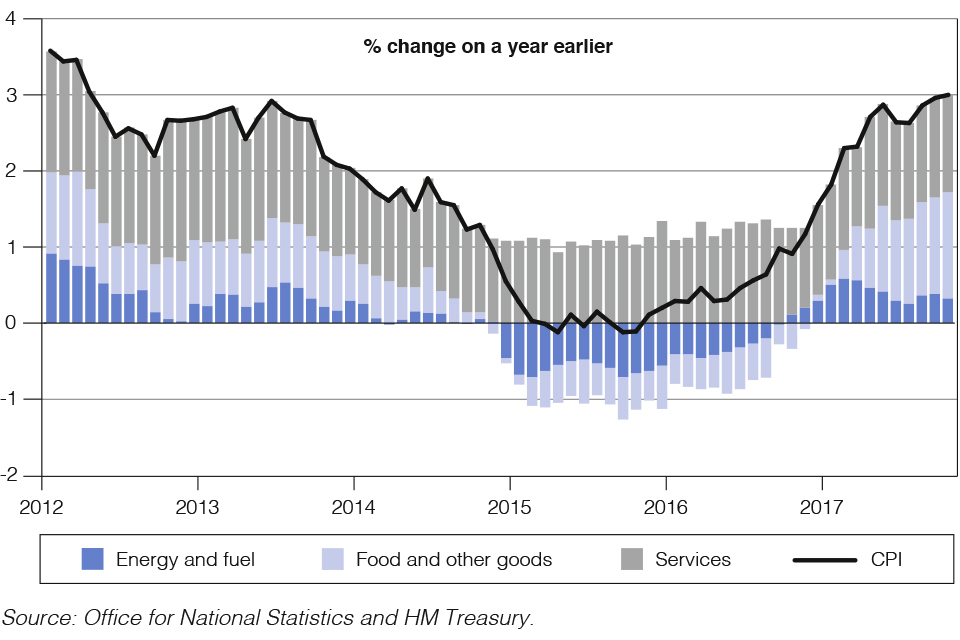

The value of sterling is little changed compared to Spring Budget 2017 in trade-weighted terms, but is around 10% below the level seen in the first half of 2016. This has fuelled an increase in inflation over the past year. Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation has risen from 0.9% in October 2016 to 3.0% in October this year and stands above the ten-year average of 2.4%. The increase has primarily been driven by a rise in goods price inflation, which has increased from -0.4% to 3.3% over the past year. In contrast, services price inflation has not increased materially, and remains below its long-run average.

Chart 1.4: CPI inflation

Chart 1.4: CPI inflation

The Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH)[footnote 2] became the ONS’s headline measure of inflation in March 2017 and regained National Statistics status in July 2017.[footnote 3] CPIH inflation was 2.8% in October 2017 and has risen broadly in line with the trends seen in CPI inflation.

2.5 Global economy

Global growth has strengthened in the first half of 2017. The OECD estimates that GDP growth for the G20 rose to 3.6% in the year to Q2 2017, up from 3.0% in Q2 2016. Growth has also become broader-based, as activity has strengthened in the euro area and Japan, and Brazil and Russia have emerged from recession. Growth has remained strong in China and firmed in the US. Higher global growth will benefit the UK economy. The OBR forecasts that global growth will be 3.6% in 2017 and 3.7% in 2018; these forecasts are both 0.2 percentage points higher than at Spring Budget 2017.

2.6 Economic outlook

The OBR’s Autumn Budget forecast is for GDP to grow each year, with the level of employment higher than at Spring Budget 2017. The OBR has revised down its view of the outlook for trend productivity in each year of the forecast, and this has fed through to revisions to the forecast for actual GDP. Given the persistent weakness in productivity growth since the financial crisis, the OBR has revised its judgement and decided to place more weight on recent trends, although it still expects productivity growth to pick up in later years of the forecast. The OBR notes: “The outlook for potential or trend productivity growth is the most important, yet most uncertain, element of potential output growth and, indeed, of [this] forecast in general”.[footnote 4] The OBR has also revised down its assessment of the sustainable rate of unemployment to 4.6% by the end of the forecast, and revised up its expectations for trend employment.

The OBR has revised down its forecast for GDP growth in 2017 to 1.5%, given slower growth than expected at the start of the year and revisions to past growth in 2016. Thereafter, slower growth is driven by the lower assumption for trend productivity. Lower GDP growth is reflected in lower consumption growth and business investment. From 2020, consumption growth picks up and GDP growth rises to 1.6% at the end of the forecast. Cumulative GDP growth is expected to be 2.1 percentage points lower over the forecast period, compared to the forecast at Spring Budget 2017. Policy measures announced in the Budget offer additional support to the economy when growth is weakest and invest in the UK’s long-term productivity.

The OBR has not attempted to predict the precise outcome of negotiations with the EU. Instead, it has made broad assumptions, which have not changed since Spring Budget 2017.

Table 1.1: Summary of the OBR’s central economic forecast (percentage change on a year earlier, unless otherwise stated) (1)

| Forecast | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| GDP | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| GDP per capita | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Main components of GDP | |||||||

| Household consumption (2) | 2.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| General government consumption | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Fixed investment | 1.3 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Business | -0.4 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| General government | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Private dwellings (3) | 5.5 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Change in inventories (4) | -0.2 | -0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Net trade (4) | -0.9 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| CPI inflation | 0.7 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Employment (millions) | 31.7 | 32.1 | 32.3 | 32.4 | 32.5 | 32.6 | 32.7 |

| LFS unemployment (% rate) (5) | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Productivity per hour | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| 1 All figures in this table are rounded to the nearest decimal place. This is not intended to convey a degree of unwarranted accuracy. Components may not sum to total due to rounding and the statistical discrepancy. |

| 2 Includes households and non-profit institutions serving households. |

| 3 Includes transfer costs of non-produced assets. |

| 4 Contribution to GDP growth, percentage points. |

| 5 Labour Force Survey. |

| Source: Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility. |

2.7 Growth

GDP growth in 2017 has been revised down to 1.5%, reflecting weaker growth than expected at the start of the year and the ONS’s revisions to GDP in 2016. The OBR forecasts slower growth to continue into 2018 and 2019 with GDP growth of 1.4% and 1.3% respectively, before rising to 1.6% at the end of the forecast period. Lower forecast GDP growth also reflects the ONS’s latest population projections, with annual net migration lower by around 20,000; this reduces the level of GDP by around 0.2% by 2022.

Household consumption has been revised down in each year of the forecast. The OBR forecasts consumption growth of 1.5% in 2017, slowing to 0.8% in 2018, before increasing gradually to 1.6% in 2022.

The OBR has revised down the path of business investment growth relative to its forecast at Spring Budget 2017. Business investment is forecast to grow by 2.5% in 2017 and by either 2.3% or 2.4% in every other year of the forecast.

The OBR has revised up its net trade forecast for 2017 due to stronger exports growth in the first half of the year, and expects it to make a positive contribution to GDP growth of 0.4 percentage points. The net trade contribution then declines to 0.2 percentage points in 2018 and makes no contribution to growth for the rest of the forecast period. The current account deficit is expected to narrow to 4.6% in 2017 and remain at a similar level until 2020, before falling to 4.4% of GDP in the final years of the forecast.

2.8 Productivity, labour market and earnings

The OBR expects productivity to remain flat in 2017, before increasing 0.9% in 2018 and 1.0% in 2019. Productivity growth is then forecast to increase to 1.3% in later years. This compares to the Spring Budget 2017 forecast of 1.7% on average over the forecast period.

The OBR has revised down its forecast for the unemployment rate in every year. This is due to a revised judgement on the equilibrium rate of unemployment in the economy – the lowest unemployment rate which can be sustained while maintaining stable inflation. As a result, the number of people in employment is forecast to continue to increase to 32.7 million in 2022 – a further 600,000 people in work by the final year of the forecast. The unemployment rate is forecast to increase slightly over the forecast horizon as it returns to the OBR’s new estimate of its equilibrium rate, remaining at 4.6% from 2020 onwards.

With a lower forecast for productivity growth the OBR expects average earnings growth of 2.3% in 2017, 2018 and 2019. It then increases to 2.6% in 2020, 3.0% in 2021 and 3.1% in 2022. The OBR expects RHDI per head to fall by 0.8% in 2017, before it then grows by 1.7% over the rest of the forecast period.

2.9 Prices

The OBR forecasts CPI inflation to peak at the end of this year, averaging 3.0% in Q4. It is then expected to ease over 2018, reaching 2.0% by the end of the year, as the effect of sterling’s depreciation wanes. Inflation then remains steady around 2.0% until the end of the forecast.

2.10 Monetary policy

The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England has full operational independence to set monetary policy. Monetary policy is a critical element of the UK’s macroeconomic framework which is important to maintain price stability and to support the economy.

Low and stable inflation supports living standards and provides certainty for households and businesses. This helps households and businesses make efficient decisions about saving, investment and spending. The MPC voted to raise interest rates from 0.25% to 0.5% at their November meeting.[footnote 5]

The Chancellor is responsible for setting the MPC’s remit. In the Budget, the Chancellor reaffirms the symmetric inflation target of 2% for the 12-month increase in the CPI measure of inflation, which applies at all times. The government also confirms that the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) will remain in place for the financial years 2017-18 and 2018-19.

On 4 August 2016, the MPC announced a new Term Funding Scheme (TFS) and the Chancellor agreed that the total drawings of the TFS would be determined by actual usage of the scheme. In response to a request from the Governor of the Bank of England on 20 November 2017, the Chancellor authorised an increase in the total size of the APF of £25 billion to £585 billion, in order to accommodate expected usage of the TFS.[footnote 6] This will ensure that the TFS can continue to lend central bank reserves to banks and building societies at rates close to Bank Rate during the defined drawdown window, which will close on 28 February 2018.

2.11 Public finances

The government has made significant progress since 2010 in restoring the public finances to health. The deficit has been reduced by three quarters from a post-war high of 9.9% of GDP in 2009-10 to 2.3% in 2016-17, its lowest level since before the financial crisis.[footnote 7]

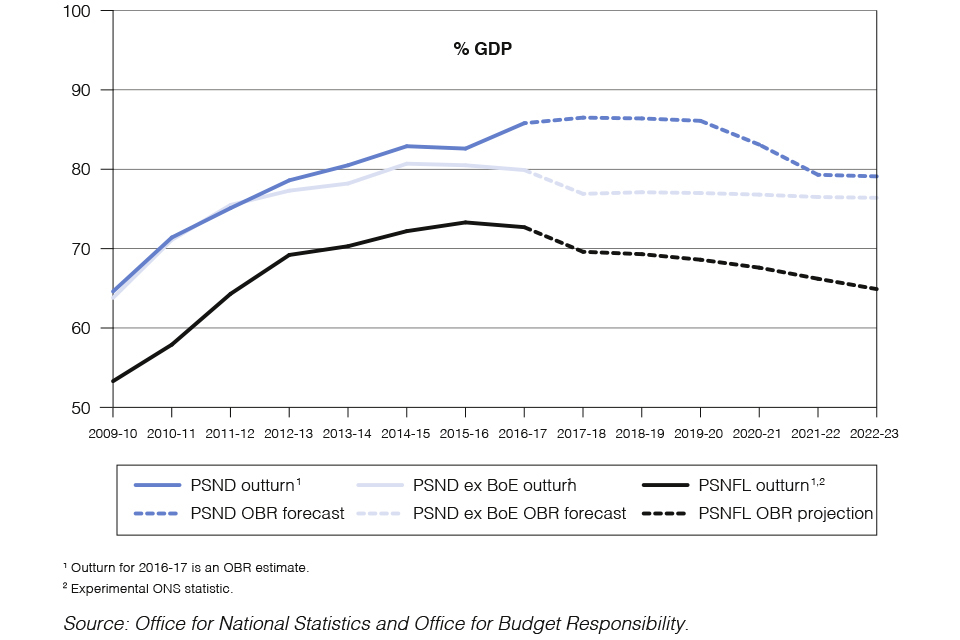

Despite these improvements, borrowing and debt remain too high. The OBR forecast debt will peak at 86.5 % of GDP in 2017-18,[footnote 8] the highest it has been in 50 years.[footnote 9] In order to ensure the UK’s economic resilience, improve fiscal sustainability, and lessen the burden on future generations, borrowing needs to be reduced further.

The fiscal rules approved by Parliament in January 2017 commit the government to reducing the cyclically-adjusted deficit to below 2% of GDP by 2020-21 and having debt as a share of GDP falling in 2020-21.[footnote 10] These rules will guide the UK towards a balanced budget by the middle of the next decade. The OBR forecasts that the government will meet both its fiscal targets, and that borrowing will reach its lowest level since 2001-02 by the end of the forecast period.[footnote 11] Debt as a share of GDP is forecast to fall next year and in every year of the forecast.

The rules enable the government to take a balanced approach between returning the public finances to a sustainable position while helping households and businesses, supporting our world-class public services, and investing in Britain’s future.

2.12 The fiscal outlook

Compared to the Spring Budget 2017 forecast, borrowing is significantly lower in the near term, due to a combination of stronger than expected receipts, lower spending, and classification changes. Over the medium term the impact of a weaker economic outlook and the measures taken at the Budget see borrowing higher than previously forecast. As at Spring Budget 2017, debt as a share of GDP peaks in 2017-18 and then falls over the remainder of the forecast.

Borrowing in 2017-18 is £49.9 billion, £8.4 billion lower than forecast at Spring Budget 2017. Receipts are forecast to be higher by £3.1 billion, reflecting stronger outturn data for 2016-17 in income tax, National Insurance contributions, VAT, excise duties and interest and dividends receipts. Spending is forecast to be £3.1 billion lower, due to lower spending on welfare and tax litigation, and changes to the OBR’s forecast for departmental spending. Classification changes, predominantly the reclassification of English Housing Associations to the private sector,[footnote 12] also reduce borrowing by £2.8 billion in 2017-18. Measures taken by the government at the Budget, and described in Chapter 2, increase borrowing by £0.7 billion in 2017-18.

Compared to Spring Budget 2017, borrowing is £12.2 billion higher by 2020-21 due to a combination of the following factors:

-

Receipts are £13.0 billion lower in 2020-21 due to a weaker economic outlook, which reduces income tax, National Insurance contributions and VAT receipts.

-

Public spending in 2020-21 is £0.7 billion higher than forecast at Spring Budget 2017 due to higher local authority self-financed capital expenditure and spending on Network Rail.

-

Classification changes, principally the reclassification of English Housing Associations to the private sector, reduce borrowing by £5.1 billion in 2020-21.

-

Measures taken by the government at the Budget, and described in Chapter 2, increase borrowing by £3.6 billion in 2020-21.

Table 1.2: Changes to the OBR’s forecast for public sector net borrowing since Spring Budget 2017 (£ billion)

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring Budget 2017 | 58.3 | 40.8 | 21.4 | 20.6 | 16.8 |

| Total forecast changes since Spring Budget 2017 (1) | -9.0 | -4.0 | 4.1 | 8.6 | 11.8 |

| of which | |||||

| Receipts forecast | -3.1 | 0.4 | 8.4 | 13.0 | 20.6 |

| Spending forecast | -3.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | -3.0 |

| Accounting and classification changes | -2.8 | -5.3 | -5.0 | -5.1 | -5.8 |

| Total effect of government decisions since Spring Budget 2017 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 9.2 | 3.6 | 1.5 |

| Total changes since Spring Budget 2017 | -8.4 | -1.3 | 13.4 | 12.2 | 13.3 |

| Autumn Budget 2017 | 49.9 | 39.5 | 34.7 | 32.8 | 30.1 |

Figures may not sum due to rounding

| 1 Equivalent to lines from Table 4.8, Table 4.18 and Table 4.40 of the OBR November 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook; full references available in 'Autumn Budget 2017 data sources'. |

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations. |

Borrowing as a share of GDP rises from 2.3% last year to 2.4% this year, owing primarily to timing effects and one-off factors. It then falls over the remainder of the forecast period to 1.1% of GDP in 2022-23, its lowest level since 2001-02.[footnote 13]

Table 1.3: Overview of the OBR’s borrowing forecast as a percentage of GDP

| Outturn | Forecast | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

| Public sector net borrowing | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing | 2.2 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Treaty deficit (1) | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Memo: Output gap (2) | -0.3 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.1 | 0.0 |

| Memo: Total policy decisions (3) | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| 1 General government net borrowing on a Maastricht basis. |

| 2 Output gap measured as a percentage of potential GDP. |

| 3 Equivalent to the 'Total policy decisions' line in Table 2.1. |

| Source: Office for National Statistics, Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations. |

Debt is forecast to peak in 2017-18 at 86.5% of GDP, and then fall in every year thereafter, reaching 79.1% of GDP in 2022-23. Public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England (PSND ex BoE) is forecast to rise from 76.9% of GDP this year to 77.1% of GDP next year, then fall in every year thereafter to 76.4% of GDP in 2022-23. Public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL) falls in every year of the forecast, reaching 64.9% of GDP in 2022-23.

Table 1.4: Overview of the OBR’s debt forecast as a percentage of GDP

| Estimate (4) | Forecast | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

| Public sector net debt (1) | 85.8 | 86.5 | 86.4 | 86.1 | 83.1 | 79.3 | 79.1 |

| Public sector net debt ex Bank of England (1) | 79.9 | 76.9 | 77.1 | 77.0 | 76.8 | 76.5 | 76.4 |

| Public sector net financial liabilities (2) | 72.7 | 69.6 | 69.3 | 68.6 | 67.6 | 66.2 | 64.9 |

| Treaty debt (3) | 86.8 | 87.0 | 87.3 | 87.4 | 87.0 | 86.8 | 86.3 |

| 1 Debt at end of March; GDP centred on end of March. |

| 2 Public sector net financial liabilities at end of March; 2016-17 is an experimental ONS statistic; GDP centred on end of March. |

| 3 General government gross debt on a Maastricht basis. |

| 4 Nominal 2017 GDP for Q3 has not yet been published therefore GDP centred on end of March is an estimate. |

| Source: Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility. |

Box 1.2: The OBR’s Fiscal risks report

In July 2017, the OBR published its first ‘Fiscal risks report’ (FRR).[footnote 14] The report provides a comprehensive assessment of risks to the public finances over the medium-to-long term. It also illustrates the potential fiscal impact of a number of these risks materialising at the same time through a fiscal stress test based on the Bank of England’s annual cyclical scenario. The publication of the FRR builds on the steps that the government has taken to improve fiscal transparency, including the creation of the OBR itself, and keeps the UK at the frontier of fiscal management worldwide.

The government has made significant progress in reducing its exposure to fiscal risks. Since 2010, the government has cut the deficit by three quarters as a share of GDP, strengthened financial sector supervision to reduce the likelihood and impact of financial instability, and established a new approval regime for government guarantees and other contingent liabilities.

Despite this progress, the FRR shows that the UK’s fiscal position remains vulnerable. Elevated levels of government debt and growing demographic pressures leave the public finances exposed to possible shocks to economic growth, inflation, and interest rates, as illustrated by the FRR’s stress test scenario which saw government debt rise to 114% of GDP by 2021-22. These high levels of debt also increase the burden on future generations.

The government is committed to enhancing the UK’s fiscal resilience by reducing the structural deficit to below 2% of GDP and getting debt to fall as a share of GDP by 2020-21, on course to returning the public finances to balance by the mid-2020s. The government will also take further action to mitigate the risks identified in the FRR and publish its formal response to the report by the summer of 2018.

2.13 Performance against the fiscal rules

The OBR’s ‘Economic and fiscal outlook’ shows that the government is forecast to meet the 2% cyclically-adjusted deficit rule two years early in 2018-19, with £14.8 billion (0.7% of GDP) of headroom in the target year of 2020-21. The OBR judges that on current policy, the government has a 65% chance of achieving the fiscal mandate in 2020-21.

Chart 1.5: Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing (CAPSNB)

Chart 1.5: Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing (CAPSNB)

The ONS’s outturn data shows the UK’s Treaty deficit[footnote 15] was 2.3% of GDP in 2016-17,[footnote 16] below the 3.0% of GDP target agreed in the Stability and Growth Pact. The OBR forecasts it will remain below 3.0% of GDP during the forecast period.

The supplementary debt target

The OBR’s forecast also shows that the government is expected to meet its supplementary debt target. Debt as a share of GDP is forecast to fall in 2020-21 with £67.1 billion of headroom and is due to begin falling two years earlier in 2018-19.

Chart 1.6: Public sector debt

Chart 1.6: Public sector debt

2.14 Welfare cap

The welfare cap is designed to improve Parliamentary accountability of welfare spending. It currently applies to spending on benefits and tax credits within its scope in 2021-22, and includes a 3% margin to manage unavoidable fluctuations in spending.

In accordance with the Charter for Budget Responsibility, as is mandated for the first fiscal event of this Parliament, the OBR has formally assessed spending against the welfare cap in its ‘Economic and fiscal outlook’. Spending within scope is forecast to be within the welfare cap and margin, and so the fiscal rule is judged to have been met with £2.5 billion of headroom.

The government is now required to reset the welfare cap for the new Parliament. The cap will be based on the OBR forecast in the Budget of the benefits and tax credits in scope as set out in Annex B, and will apply to welfare spending in 2022-23. In the interim years, progress towards the cap will be managed internally, based on the OBR’s monitoring of forecasts of welfare spending. Again, to manage unavoidable fluctuations in welfare spending there will be a margin rising to 3% above the cap; the cap will be breached if spending exceeds the cap plus the margin at the point of assessment.

Performance against the cap will be formally assessed by the OBR in 2022-23. This will avoid the government having to make short term responses to changes in the welfare forecast, while ensuring welfare spending remains sustainable in the medium term.

Further details on the operation of the cap are set out in the Charter for Budget Responsibility.

Table 1.5: New welfare cap (in £ billion, unless otherwise stated)

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cap | - | - | - | - | - | 130.1 |

| Interim pathway | 119.3 | 120.9 | 122.1 | 123.8 | 126.9 | - |

| Margin (%) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Source: HM Treasury |

2.15 Public spending

With debt still too high, it is vital that the government continues to control public spending and improve the productivity of public bodies and services. Government spending as a share of GDP has been brought down from 44.8% in 2010-11 to 39.0% in 2016-17.[footnote 17] Total Managed Expenditure (TME) as a share of GDP is forecast to fall from 38.9% in 2017-18 to 37.7% in 2022-23, the same proportion of GDP as in 2003-04.[footnote 18] Table 1.6 sets out the path for TME, Public Sector Current Expenditure (PSCE) and Public Sector Gross Investment (PSGI) to 2022-23.

Tables 1.7 and 1.8 show the departmental resource and capital totals set at Spending Review 2015, adjusted to reflect subsequent announcements. These reflect the government’s balanced approach to public spending set out in Spending Review 2015, including its commitments to priority public services, to defence and to international development.[footnote 19]

For the years beyond the current Spending Review period, the government sets out a path for overall expenditure. Before additional investment over the forecast period and excluding classification changes, departmental spending will continue to grow in 2020-21 and 2021-22 in line with the profiles set out at Autumn Statement 2016 and Spring Budget 2017. In 2022-23, departmental resource spending will continue to grow in line with inflation, and departmental capital spending will grow in line with GDP.

Table 1.6: Total managed expenditure (in £ billion, unless otherwise stated) (1, 2)

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current expenditure | ||||||

| Resource AME | 386.5 | 397.8 | 406.2 | 417.0 | 431.5 | 447.6 |

| Resource DEL excluding depreciation | 304.0 | 309.6 | 310.7 | 313.5 | 319.1 | 324.8 |

| Ring-fenced depreciation | 22.0 | 22.8 | 23.3 | 21.9 | 22.3 | 22.7 |

| Total public sector current expenditure | 712.5 | 730.2 | 740.1 | 752.4 | 772.9 | 795.1 |

| Capital expenditure | ||||||

| Capital AME | 26.0 | 18.0 | 17.7 | 21.3 | 23.0 | 23.8 |

| Capital DEL | 56.9 | 61.1 | 69.0 | 76.2 | 75.8 | 77.9 |

| Total public sector gross investment | 82.8 | 79.1 | 86.6 | 97.6 | 98.8 | 101.8 |

| Total managed expenditure | 795.3 | 809.3 | 826.7 | 849.9 | 871.7 | 896.8 |

| Total managed expenditure % of GDP | 38.9% | 38.5% | 38.3% | 38.2% | 37.9% | 37.7% |

| 1. Budgeting totals are shown including the OBR forecast allowance for shortfall. Resource DEL excluding ring-fenced depreciation is the Treasury's primary control within resource budgets and is the basis on which departmental Spending Review settlements are agreed. The OBR publishes Public Sector Current Expenditure (PSCE) in DEL and AME, and Public Sector Gross Investment (PSGI) in DEL and AME. A reconciliation is published by the OBR. |

| 2. The ONS has announced the reclassification of English Housing Associations to the private sector with effect from 16 November 2017, which means that from this date their expenditure is no longer part of PSGI. As a result of reclassification, the OBR now considers that from this date central government grants to Housing Associations will be part of PSGI in CDEL. More detail can be found in the OBR’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook. |

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations |

2.16 Preparing for EU exit

The government is approaching the EU exit negotiations anticipating success. The government does not want or expect to leave without a deal, but while it seeks a new partnership, it is planning for a range of outcomes, as is the responsible thing to do. To support the preparations, nearly £700 million of additional funding has been provided to date. Details of additional departmental funding will be set out as part of the 2017-18 Supplementary Estimates process in the usual way.

The Budget sets aside a further £3 billion to ensure that the government can continue to prepare effectively for EU exit. £1.5 billion of additional funding will be made available in each of 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Departmental allocations for preparing for EU exit in 2018-19 will be agreed in early 2018. Ahead of these allocations, government departments will continue to refine their 2018-19 plans with the support of HM Treasury and the Department for Exiting the European Union. Details of additional departmental funding will be set out as part of the 2018-19 Supplementary Estimates process in the usual way. Departmental allocations for 2019-20 will be agreed later in 2018-19, when there is more certainty on the status of our future relationship with the EU.

2.17 Efficiency Review and Official Development Assistance

At Budget 2016, the government announced that spending would be reduced by £3.5 billion over Spending Review 2015 plans in 2019-20. An Efficiency Review was launched to help deliver this. As announced at Autumn Statement 2016 the government has reprioritised £1 billion of low value spend to fund new priorities, instead of putting savings toward deficit reduction as originally planned.

A further £1.4 billion reduction has been delivered by a number of savings in low value spend, announced in the previous Parliament, in addition to lower than forecast Official Development Assistance (ODA) spending. In line with the commitment to spend 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) on ODA each year, ODA budgets will be adjusted at the Budget to reflect the OBR’s revised forecasts for GNI. Taking existing plans into account, ODA budgets will be adjusted down by £375 million in 2018-19 and £520 million in 2019-20.

Given potential new spending and administrative pressures faced by departments in 2019‑20, the government has decided not to proceed with the remaining £1.1 billion reduction in spending in that year. Taking these changes together, departmental spending in 2019-20 will therefore be higher than envisaged at Budget 2016 by £2.1 billion.

Table 1.7: Departmental Resource Budgets (£ billion)

| Plans | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | |

| Resource DEL excluding depreciation (1) | |||

| Defence | 27.5 | 28.2 | 29.0 |

| Single Intelligence Account (2) | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Home Office | 10.6 | 10.7 | 10.7 |

| Foreign and Commonwealth Office (3) | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| International Development (4) | 7.6 | 8.7 | 8.2 |

| Health (inc. NHS) | 119.1 | 121.9 | 124.2 |

| Work and Pensions | 6.2 | 6.0 | 5.4 |

| Education | 61.3 | 62.4 | 63.3 |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Transport | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.7 |

| Exiting the European Union | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| DCLG Communities | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| DCLG Local Government | 6.7 | 4.8 | 5.6 |

| Scotland (5) | 14.3 | 13.8 | 13.5 |

| Wales (6) | 13.4 | 13.2 | 11.2 |

| Northern Ireland | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Justice | 6.6 | 6.2 | 6.0 |

| Law Officers Departments | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| HM Revenue and Customs | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| HM Treasury | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Cabinet Office | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| International Trade | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Small and Independent Bodies | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Reserves (7) | 3.5 | 6.5 | 7.2 |

| Adjustment for Budget Exchange (8) | -0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total Resource DEL excluding depreciation | 306.7 | 310.9 | 311.9 |

| OBR allowance for shortfall (9) | -2.8 | -1.3 | -1.3 |

| OBR resource DEL excluding depreciation forecast | 304.0 | 309.6 | 310.7 |

| 1. Resource DEL excluding depreciation is the Treasury's primary control total within resource budgets and the basis on which Spending Review settlements were made. |

| 2. The SIA budget in 2017-18 includes transfers from other government departments, which have yet to be reflected in later years. |

| 3.Figures for 2018-19 and beyond do not reflect all transfers which will be made from DFID to other government departments, as the cross government funds have not been allocated for these years. |

| 4.Figures reflect Autumn Budget 2017 adjustments, as well as further adjustments made as result of revised GNI forecasts at Autumn Statement 2016. |

| 5.The Scottish Government’s resource DEL block grant has been adjusted from 2016-17 onwards as agreed in the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Framework. In 2016-17 an adjustment of £5.5 billion reflected the devolution of Stamp Duty Land Tax and Landfill Tax and the creation of the Scottish Rate of Income Tax. In 2017-18 an adjustment of £12.5 billion reflects the devolution of further income tax powers and revenues from Scottish courts. In 2018-19 and 2019-20, adjustments of £13.1 billion and £13.4 billion also include the devolution of Air Passenger Duty. However, the UK and Scottish governments have now agreed to delay the devolution of Air Passenger Duty. As a result, the Scottish Government’s block grant for 2018-19 and 2019-20 will be re-calculated. |

| 6. The Welsh Government’s resource DEL block grant has been adjusted from 2018-19 onwards as agreed in the Welsh Government’s Fiscal Framework. In 2018-19 an adjustment of £0.3 billion reflects the devolution of Stamp Duty Land Tax and Landfill Tax and in 2019-20 an adjustment of £2.3 billion reflects the devolution of the Welsh Rates of Income Tax. |

| 7. The reserve in 2017-18 reflects allocations made at Main Estimates and Autumn Budget 2017. |

| 8. Departmental budgets in 2017-18 include amounts carried forward from 2016-17 through Budget Exchange, which has been voted at Main Estimates. These increases will be offset at Supplementary Estimates, so are excluded from spending totals. |

| 9. The OBR's forecast of underspends in resource DEL budgets. |

Table 1.8: Departmental Capital Budgets (£ billion)

| Plans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | |

| Capital DEL | ||||

| Defence | 8.5 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.6 |

| Single Intelligence Account | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Home Office | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Foreign and Commonwealth Office | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| International Development | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| Health (inc. NHS) | 5.6 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.8 |

| Work and Pensions | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Education | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.5 |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (1) | 10.9 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 6.1 |

| Transport | 6.5 | 8.1 | 11.9 | 13.0 |

| Exiting the European Union | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| DCLG Communities | 7.7 | 8.6 | 10.5 | 11.6 |

| DCLG Local Government | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Scotland | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.3 |

| Wales | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Northern Ireland | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Justice | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Law Officers Departments | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| HM Revenue and Customs | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| HM Treasury | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Cabinet Office | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| International Trade | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Small and Independent Bodies | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Reserves | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Capital spending not yet in budgets (2) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| Adjustment for Budget Exchange (3) | -0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Adjustment for Research & Development RDEL to CDEL switch (4) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.5 |

| Total Capital DEL | 58.7 | 62.9 | 71.3 | 76.2 |

| Remove CDEL not in public sector gross investment (5) | -8.6 | -8.5 | -9.2 | -7.9 |

| OBR allowance for shortfall (6) | -1.9 | -1.8 | -2.3 | - |

| Public Sector Gross Investment in CDEL | 48.2 | 52.6 | 59.7 | 68.3 |

| 1. Full BEIS capital DEL budgets for 2020-21 have not yet been set. See footnote 4. |

| 2. The uplift in capital DEL represents funding not allocated to departments. It is presented net of the OBR's allowance for shortfall in 2020-21. |

| 3. Departmental budgets in 2017-18 include amounts carried forward from 2016-17 through Budget Exchange, which have been voted at Main Estimates. These increases will be offset at Supplementary Estimates, so are excluded from spending totals. |

| 4. As most departmental resource DEL budgets have not been set in 2020-21, the OBR has forecast the size of the resource to capital switch for R&D that will take place in that year. |

| 5. Capital DEL that does not form part of public sector gross investment, including financial transactions in capital DEL. |

| 6. The OBR's forecast of underspends in capital DEL budgets. |

2.18 Devolved administrations

The application of the Barnett formula to spending decisions taken by the UK government at the Budget will provide each of the devolved administrations with additional funding to be allocated according to their own priorities. The Scottish and Welsh governments’ block grants will be further adjusted as set out in their respective fiscal frameworks.

2.19 Financial transactions

Some policy measures do not directly affect PSNB in the same way as conventional spending or taxation. These include financial transactions that directly affect only the central government net cash requirement (CGNCR) and PSND. Table 1.9 shows the effect of the financial transactions announced since Spring Budget 2017 on CGNCR.

Table 1.9: Financial transactions from 2017-18 to 2022-23 (£ million) (1,2)

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Help to Buy: Equity Loan (Spending) (3) | -1,895 | -2,870 | -3,325 | -3,780 | - | - |

| Help to Buy: Equity Loan (Receipts) | 30 | 125 | 355 | 725 | 1,130 | 1,510 |

| Estate Regeneration | 0 | -60 | -85 | -95 | -120 | -120 |

| Home Building Fund: SMEs | 0 | -365 | -620 | -440 | -235 | -120 |

| Patient Capital Investment Fund | 0 | 0 | -115 | -175 | -195 | -195 |

| Charging Infrastructure Investment Fund | 0 | -40 | -80 | -80 | 0 | 0 |

| Tuition Fee Cap Freeze | 0 | 105 | 220 | 225 | 230 | 235 |

| Student Loans Repayment Threshold (4) | 0 | -125 | -235 | -370 | -490 | -615 |

| RBS Share Sales | 0 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,000 |

| Universal Credit: Advances | -20 | -100 | -40 | -35 | -10 | 5 |

| Innovation Loans | 0 | -20 | -20 | -5 | 0 | 0 |

| Reprofile Financial Transactions (BEIS) | 0 | 80 | -80 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total policy decisions | -1,885 | -270 | -1,025 | -1,030 | 3,310 | 3,700 |

| 1. Costings reflect the OBR's latest economic and fiscal determinants, and are presented on a UK basis. |

| 2. Negative numbers in the table represent a cost to the Exchequer. |

| 3. The Government confirmed in October 2017 that Help to Buy Equity Loan will continue until March 2021. |

| 4. Student Loans Plan 2 Repayment Threshold Increase to £25,000 in 2018-19 and index with average earnings thereafter. |

2.20 Sovereign Grant

The Sovereign Grant for 2018-19 will be £82.2 million. This grant provides funding in support of Her Majesty’s official duties as Sovereign.

2.21 Asset sales

The government remains committed to returning the financial sector assets acquired in 2008 to 2009 to the private sector in a way that achieves value for money for taxpayers:

-

Lloyds Banking Group (LBG) – The government fully exited its shareholding in LBG on 16 May 2017.[footnote 20] Sales of the government’s stake in the bank generated over £21.2 billion for taxpayers, representing almost £900 million more than the original investment.[footnote 21]

-

Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) – RBS has made significant progress on resolving its legacy issues and refocusing on serving British businesses and consumers. It remains the government’s objective to return the bank fully to the private sector when it represents value for money to do so and market conditions allow. The government intends to recommence the privatisation of RBS before the end of 2018-19 and to carry out over the forecast period a programme of sales expected to dispose of around £15 billion worth of shares, which represents around two thirds of our stake at current market prices.

-

UK Asset Resolution (UKAR) – UKAR’s balance sheet has already reduced from £115.8 billion in 2010 to £34.3 billion as at 31 March 2017.[footnote 22] UKAR has completed an £11.8 billion sale of Bradford Bingley mortgages in 2017-18 as part of a programme of sales to repay Bradford Bingley’s debt to the Financial Services Compensation Scheme,[footnote 23] and this programme of sales is expected to complete in early 2018-19. Building on UKAR’s strong track record of successful asset sales, the government expects to divest the remaining assets from the former Bradford Bingley and Northern Rock by March 2021, subject to achieving value for money and market conditions remaining supportive.

The government continues to explore options for the sale of wider corporate and financial assets, where there is no longer a policy reason to retain them and when value for money can be secured for taxpayers. This is an integral part of the government’s plan to repair the public finances:

-

On 20 April 2017, the government announced the sale of the UK Green Investment Bank plc (GIB) to Macquarie Group Limited, with a £2.3 billion deal which secures a profit on the government’s investment in the bank, provides value for taxpayers and ensures GIB continues its green mission in the private sector.[footnote 24]

-

On 31 October 2017, the government announced the continuation of the process to sell part of the pre-2012 income contingent repayment student loan book.[footnote 25] The sale process is expected to take a number of weeks and remains subject to market conditions and a final assessment of value for money. This is the first tranche of a programme of sales which is forecast to raise £12 billion by 2021-22.

-

On 17 November 2017, Network Rail announced its intention to sell the leases for commercial space under railway arches.[footnote 26] The sale is expected to complete in the autumn of 2018.

2.22 Debt and reserves management

The government’s revised financing plans for 2017-18 are summarised in Annex A.

3. Policy decisions

The following chapters set out all Autumn Budget policy decisions. Unless stated otherwise, the decisions set out are ones which are announced at the Budget.

Table 2.1 shows the cost or yield of all Autumn Budget decisions with a direct effect on PSNB in the years up 2022-23. This includes tax measures, changes to Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL) and measures affecting annually managed expenditure (AME).

The government is also publishing the methodology underpinning the calculation of the fiscal impact of each policy decision. This is included in the supplementary document ‘Autumn Budget 2017: policy costings’ published alongside the Budget.

The supplementary document ‘Overview of Tax Legislation and Rates’ published alongside the Budget, provides a more detailed explanation of tax measures.

Table 2.1: Autumn Budget 2017 policy decisions (£ million) (1)

| Head | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing and Homeownership | |||||||

| 1 Land Assembly Fund (3) | Spend | 0 | 0 | -220 | -355 | -355 | -355 |

| 2 Housing Infrastructure Fund: extend (3) | Spend | 0 | 0 | -215 | -710 | -1,070 | -1,185 |

| 3 Small sites: infrastructure and remediation | Spend | 0 | -275 | -355 | -120 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 Local Authority housebuilding: additional investment | Spend | 0 | 0 | -355 | -265 | -260 | 0 |

| 5 Stamp Duty Land Tax: abolish for First Time Buyers up to £300,000 | Tax | -125 | -560 | -585 | -610 | -640 | -670 |

| 6 Right to Buy for Housing Association tenants: pilot | Spend | 0 | 0 | -85 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 Council Tax: increase maximum empty home premium to 100% | Tax | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +5 | +5 |

| National Health Service | |||||||

| 8 NHS: additional resource | Spend | -400 | -1,900 | -1,070 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 NHS: additional capital | Spend | -600 | -420 | -840 | -1,020 | -960 | -360 |

| Supporting families and working people | |||||||

| 10 Fuel Duty: freeze for 2018-19 | Tax | 0 | -830 | -825 | -845 | -865 | -885 |

| 11 Alcohol Duties: freeze in 2018 | Tax | -35 | -225 | -230 | -230 | -235 | -240 |

| 12 Air Passenger Duty: freeze for long-haul economy flights and raise business class multiplier | Tax | 0 | 0 | +25 | +25 | +25 | +30 |

| 13 Targeted Affordability Fund: increase | Spend | 0 | -40 | -85 | -95 | -100 | -110 |

| 14 Universal Credit: remove 7 day wait and extend advances to 100% | Spend | -20 | -170 | -205 | -195 | -160 | -145 |

| 15 Universal Credit: run on payment for housing benefit recipients | Spend | 0 | -130 | -125 | -135 | -110 | -40 |

| 16 Universal Credit: in-work progression trials | Spend | * | * | * | -5 | -5 | 0 |

| 17 Private rented sector access schemes: support for households at risk of homelessness | Spend | 0 | -10 | -10 | - | - | - |

| 18 Disabled Facilities Grant: additional resource | Spend | -50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 Relationship Support: continue programme | Spend | 0 | -5 | -10 | - | - | - |

| An economy fit for the future | |||||||

| 20 Domestic spending: preparing for EU Exit | Spend | 0 | -1,500 | -1,500 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 National Productivity Investment Fund (3) | Spend | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -7,000 |

| 22 Research and Development: NPIF investment (3) | Spend | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2,300 | - |

| 23 Research and Development: increase R&D expenditure credit to 12% | Spend | -5 | -60 | -170 | -175 | -170 | -175 |

| 24 Oil and Gas: transferrable tax history | Tax | 0 | +5 | +20 | +10 | +10 | +25 |

| 25 Patient Capital Review: reforms to tax reliefs to support productive investment | Tax | 0 | 0 | +45 | +35 | -15 | -20 |

| 26 Innovation: Ultra Low Emission Vehicles: plug in car grant | Spend | 0 | -50 | -50 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 Innovation: tech, AI, and geo-spatial data | Spend | 0 | -70 | -75 | - | - | - |

| 28 Transport: accelerate capital investment for intra-city transport (Transforming Cities Fund) | Spend | 0 | -10 | -240 | -285 | +525 | - |

| 29 Transport: additional investment in local roads | Spend | -55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 Public Works Loan Board: new local infrastructure rate | Spend | 0 | * | -5 | -5 | -5 | -5 |

| 31 Skills: National Retraining Scheme initial investment | Spend | 0 | -20 | -45 | - | - | - |

| 32 Skills: investment in computer science teachers and maths | Spend | 0 | -30 | -50 | - | - | - |

| 33 Skills: teacher premium pilot | Spend | 0 | -10 | -15 | -15 | -5 | 0 |

| 34 Business Rates: bring forward CPI uprating to 2018-19 | Tax | 0 | -240 | -530 | -525 | -520 | -520 |

| 35 Business Rates: extend pubs discount to 2018-19 | Tax | 0 | -30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 36 Competition and Markets Authority: additional enforcement | Spend | 0 | -5 | -5 | +5 | +15 | +10 |

| 37 Aggregates Levy: freeze in 2018-19 | Tax | 0 | -15 | -10 | -10 | -10 | -10 |

| 38 HGV VED and Road User Levy: freeze in 2018-19 | Tax | 0 | -15 | -10 | -15 | -15 | -15 |

| Avoidance, Evasion, Fraud and Error | |||||||

| 39 Avoidance and Evasion: additional compliance resource | Tax | -10 | +10 | +170 | +585 | +580 | +740 |

| 40 Corporation Tax: tackle related party step up schemes | Tax | +15 | +45 | +45 | +45 | +45 | +45 |

| 41 Corporation Tax: depreciatory transactions | Tax | +5 | +10 | +10 | +10 | +10 | +10 |

| 42 Royalty payments made to low tax jurisdictions: withholding tax | Tax | 0 | 0 | +285 | +225 | +160 | +130 |

| 43 Online VAT fraud: extend powers to combat | Tax | 0 | +10 | +20 | +40 | +50 | +45 |

| 44 Offshore Time Limits: extend to prevent non-compliance | Tax | 0 | * | * | * | +5 | +10 |

| 45 Carried Interest: prevent avoidance of Capital Gains Tax | Tax | 0 | +20 | +170 | +165 | +150 | +145 |

| 46 Insolvency use to escape tax debt | Tax | 0 | -5 | +70 | +135 | +150 | +150 |

| 47 Dynamic coding-out of debt | Tax | 0 | 0 | +55 | +30 | +20 | +20 |

| 48 Construction supply chain VAT fraud: introduce reverse charge | Tax | 0 | 0 | +90 | +135 | +105 | +75 |

| 49 Waste crime | Tax | 0 | +30 | +45 | +45 | +50 | +45 |

| 50 Fraud, Error, and Debt: greater use of real-time information | Spend | 0 | +85 | +75 | +65 | +40 | +40 |

| A fair and sustainable tax system | |||||||

| 51 Corporation Tax: freeze indexation allowance from January 2018 | Tax | +30 | +165 | +265 | +345 | +440 | +525 |

| 52 Capital Gains Tax: extend to all non-resident gains from April 2019 | Tax | +5 | +15 | +35 | +115 | +140 | +160 |

| 53 Non-resident property income: move from Income Tax to Corporation Tax | Tax | 0 | 0 | 0 | +690 | -310 | -25 |

| 54 Capital Gains Tax payment window reduction: delay to April 2020 | Tax | 0 | 0 | -1,200 | +950 | +235 | +10 |

| 55 VAT registration threshold: maintain at £85,000 for two years | Tax | 0 | +15 | +55 | +105 | +145 | +170 |

| 56 Tobacco Duty: continue escalator and index Minimum Excise Duty | Tax | +45 | +35 | +40 | +45 | +40 | +35 |

| Other public spending | |||||||

| 57 Adjustments to DEL spending | Spend | +1,000 | 0 | -1,135 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 58 Official Development Assistance: meet 0.7% GNI target | Spend | 0 | +375 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 59 Scotland police and fire: VAT refunds | Tax | 0 | -40 | -40 | -40 | -45 | -45 |

| Air Quality | |||||||

| 60 Air Quality: increase Company Car Tax diesel supplement by 1ppt from April 2018 | Tax | 0 | +70 | +35 | -30 | +130 | +90 |

| 61 Air Quality: First Year Rate increased by one VED band for new diesel cars from April 2018 | Tax | 0 | +125 | +50 | +10 | * | * |

| 62 Air Quality: funding for Air Quality Plan and Clean Air Fund | Spend | -20 | -180 | -215 | -80 | - | - |

| Previously announced policy decisions | |||||||

| 63 Tuition Fees: raise threshold to £25,000 in April 2018 | Tax | 0 | -50 | -100 | -175 | -235 | -295 |

| 64 Tuition Fees: freeze fees in September 2018 | Tax | 0 | -5 | -15 | -25 | -35 | -45 |

| 65 Oil and Gas: funding for UK continental shelf exploration projects | Spend | 0 | -5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 66 NICs: maintain Class 4 NICs at 9% and delay NICs Bill by one year | Tax | -10 | -125 | -645 | -685 | -565 | -525 |

| 67 Making Tax Digital: only apply above VAT threshold and for VAT | Tax | * | * | -65 | -245 | -515 | -585 |

| 68 City Deals: Swansea and Edinburgh | Spend | 0 | -30 | -30 | -30 | - | - |

| 69 Social rented sector: maintain current rent policy without Local Housing Allowance cap | Spend | 0 | 0 | -155 | -205 | -255 | -320 |

| Total policy decisions (3) | -230 | -6,045 | -9,915 | -3,315 | -2,960 | -2,520 | |

| Total spending policy decisions | -150 | -4,460 | -7,190 | -3,625 | -1,450 | -1,105 | |

| Total tax policy decisions | -80 | -1,585 | -2,725 | +310 | -1,510 | -1,415 | |

| * Negligible |

| 1 Costings reflect the OBR’s latest economic and fiscal determinants. |

| 2 At Spending Review 2015, the government set departmental spending plans for resource DEL (RDEL) for the years up to and including 2019-20, and capital DEL (CDEL) for the years up to and including 2020-21. Where specific commitments have been made beyond those periods, these have been set out on the scorecard. Where a specific commitment has not been made, adjustments have been made to the overall spending assumption beyond the period. |

| 3 These figures do not feed into the Total policy decisions line. In 2021-22 and 2022-23, funding for these measures has been allocated from the aggregate total for capital spending. This includes the National Productivity Investment Fund. The NPIF will extend into 2022-23 at £7bn in that year. |

4. Tax

4.1 Introduction

The government remains committed to a low-tax economy, and is cutting taxes for both working people and businesses to help them respond to short-term pressures. Since 2010-11, the personal allowance (PA) has increased from £6,475 to £11,500 and the corporation tax rate has fallen to 19%, the lowest in the G20.[footnote 27] The Budget goes further by freezing fuel duty for the eighth consecutive year, reducing the upfront costs for first-time buyers by including a permanent Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) relief, reducing business rates by £2.3 billion over the next 5 years, and further increasing the PA and higher rate threshold (HRT).

The Budget also introduces measures to ensure that everyone pays their fair share, including those seeking to evade or avoid tax using offshore structures. The Budget increases the time limits for HMRC assessments of offshore tax non-compliance, as much as tripling the current time limits to at least 12 years in all cases, further addresses online VAT fraud, and announces investment to provide HMRC with the resources it needs to continue to strengthen its ability to tackle tax avoidance in the future. These policy changes build on the government’s longer‑term record, including £160 billion secured in additional tax revenue since 2010 by being at the forefront of global efforts to tackle avoidance, evasion and non-compliance.[footnote 28]

This is the first Budget in the new annual tax policymaking cycle. The government’s aim is to provide greater tax certainty for households and businesses by consulting with taxpayers further in advance of changes and changing taxes less frequently. Further details on this new process will be set out later this year. To accommodate the move to an Autumn Budget, at this Budget the government has changed the forecasted timetable for the uprating of alcohol and tobacco duties. The forecast now assumes that alcohol duties will be uprated on 1 February, and tobacco duties will be uprated at 6pm on Budget day. As the OBR confirms, the changes are designed to be largely neutral for receipts.[footnote 29] Further details are available in the Autumn Budget 2017: policy costings document.

4.2 Personal tax

The government puts the interests of ordinary working families first in the tax system. Since 2010-11, the PA has been increased from £6,475 to £11,500. Successive increases in the PA and HRT have allowed over 31 million working people to keep more of what they earn, and have taken over a million people out of paying income tax altogether.[footnote 30]

4.3 Income tax and National Insurance

Personal allowance and higher rate threshold – The government is committed to raising the PA to £12,500 and the HRT to £50,000 by 2020 – which will mean an increase to the PA of over 90% in the space of a decade. The Budget announces that in 2018-19 the PA and HRT will increase further, to £11,850 and £46,350 respectively.[footnote 31] This will mean that in 2018-19 a typical taxpayer will pay at least £1,075 less tax than in 2010-11.

Marriage Allowance: allowing claims on behalf of deceased partners – The Marriage Allowance allows taxpayers to transfer up to 10% of their unused PA to their partner, reducing their tax bill by up to £230 a year in 2017-18. The government will now allow claims in cases where a partner has died before the claim was made. These claims will be able to be backdated by up to 4 years.

Off-payroll working in the private sector – The government reformed the off-payroll working rules (known as IR35) for engagements in the public sector in April 2017. Early indications are that public sector compliance is increasing as a result, and therefore a possible next step would be to extend the reforms to the private sector, to ensure individuals who effectively work as employees are taxed as employees even if they choose to structure their work through a company. It is right that the government take account of the needs of businesses and individuals who would implement any change. Therefore the government will carefully consult on how to tackle non-compliance in the private sector, drawing on the experience of the public sector reforms, including through external research already commissioned by the government and due to be published in 2018.

Employment status discussion paper – The government will publish a discussion paper as part of the response to Matthew Taylor’s review of employment practices in the modern economy, exploring the case and options for longer-term reform to make the employment status tests for both employment rights and tax clearer. The government recognises that this is an important and complex issue, and so will work with stakeholders to ensure that any potential changes are considered carefully.[footnote 32]

Taxation of trusts – The government will publish a consultation in 2018 on how to make the taxation of trusts simpler, fairer, and more transparent.

National Insurance Contributions (NICs) Bill – As previously announced, to ensure that there is enough time to work with Parliament and stakeholders on the detail of reforms that will simplify the NICs system, the government has announced that it will delay implementing a series of NICs policies by one year. These are the abolition of Class 2 NICs, reforms to the NICs treatment of termination payments, and changes to the NICs treatment of sporting testimonials. (66)

Rent-a-room relief – The government will publish a call for evidence to establish how rent-a-room relief is used and ensure it is better targeted at longer-term lettings.

Mileage rates for landlords – The government will extend the option to use mileage rates to individuals operating property businesses, on a voluntary basis, to reduce the administrative burden for these businesses.

Benefits in kind: electric vehicles – From April 2018, there will be no benefit in kind charge on electricity that employers provide to charge employees’ electric vehicles.

Taxation of employee business expenses – Following the call for evidence published in March 2017, the government will make several changes to the taxation of employee expenses:

-

Self-funded training – The government will consult in 2018 on extending the scope of tax relief currently available to employees and the self-employed for work-related training costs.

-

Subsistence benchmark scale rates – To reduce the burden on employers, from April 2019 they will no longer be required to check receipts when reimbursing employees for subsistence using benchmark scale rates. The existing concessionary accommodation and subsistence overseas scale rates will be placed on a statutory basis, to provide greater certainty for businesses.

-

Guidance and claims process for employee expenses – HMRC will work with external stakeholders to improve the guidance on employee expenses, particularly on travel and subsistence and the process for claiming tax relief on non-reimbursed employment expenses.

Armed Forces personnel accommodation – An income tax and NICs exemption will be introduced for certain allowances paid to Armed Forces personnel for renting or maintaining accommodation in the UK private market. This will support the Ministry of Defence’s aim to provide a more flexible, attractive and better value-for-money approach to accommodation.

Seafarers’ Earnings Deduction and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary – Seafarers are entitled to an income tax deduction of their foreign earnings in certain circumstances. The existing extra-statutory treatment of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary will be placed on a statutory basis.