Arm's length body sponsorship code of good practice

Published 23 May 2022

Ministerial foreword

Public bodies form an important means of providing services on behalf of Her Majesty’s Government. They cover a wide range of areas, from health to education, justice to defence and beyond. Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs) spend over £220 billion a year and employ the equivalent of over 300,000 people on a full-time basis.

Sponsorship is the activity that promotes and maintains an effective working relationship between departments and public bodies, in turn facilitating accountable, efficient and effective services to the public.

The National Audit Office (NAO) and the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) have both recommended improvements in the Government’s oversight of ALBs. This followed from a number of high-profile failures which illuminated concerns around sponsorship[footnote 1].

For this reason, HM Government decided to improve departmental sponsorship through action 24 of the Declaration on Government Reform[footnote 2]. I am, therefore, pleased to launch the Sponsorship Code of Good Practice which will fulfil that commitment.

As with all State activities, the relationship with Parliament is fundamental. ALBs must prioritise their obligations to Members of Parliament to whom they are accountable and by whom they are paid on behalf of voters. This is of particular importance when MPs seek “redress of grievance” for their constituents.

This code sets out why sponsorship is essential, what effective sponsorship entails, and how it can be undertaken. The Code requires departments to:

-

Strive to deliver best practice in six key sponsorship capabilities; and

-

Progress through three levels of maturity - ‘emerging, maturing and advanced’.

This approach recognises the variety of public bodies so HM Government Departments should be confident in complying with the Code, or explaining why compliance is not necessary or appropriate.

These measures will promote a more effective relationship between HM Government Departments and ALBs, providing better services to the British public.

Rt Hon Jacob Rees-Mogg MP

Minister for Brexit Opportunities and Government Efficiency

Introduction

What is sponsorship?

Sponsorship is the activity that delivers effective relationships between departments and their ALBs. Effective relationships help departments and their ALBs to operate as outcome delivery systems, delivering the efficient and effective public outcomes that Parliament and the public expect.

Sponsorship has a long history. The Next Steps Report (1988) recommended the establishment of Next Steps Agencies: central government public bodies focused on the delivery of policies developed by ministerial departments[footnote 3].

To deliver these principles, senior sponsors and their supporting sponsorship teams were introduced to act as the golden thread between departments and public bodies.

In its 2021 report, ‘Central oversight of arm’s length bodies’,[footnote 4] the National Audit Office (NAO) recommended that:

The Cabinet Office should set out common standards for what good departmental sponsorship arrangements look like, and work with departments to ensure sponsorship teams have the right capability and sufficient capacity. It should monitor how this is adopted by departments during its regular review of framework agreements.

In its 2021 report, ‘Government’s delivery through arm’s length bodies’,[footnote 5] the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) subsequently recommended that:

[The Cabinet Office should] assure itself that the guidance it sets is being followed and that assurance and framework documents are regularly updated; support departments and ALBs so that they can better benchmark their performance; and improve sponsorship skills across government and how it will measure the success of this.

The government committed in the June 2021, Declaration on Government Reform (“DoGR”) to “increase the effectiveness of departmental sponsorship, underpinned by clear performance metrics and rigorous new governance and sponsorship standards.” [footnote 6]The government reiterated that commitment to support and monitor the delivery of more consistently high-quality sponsorship arrangements across government in its response to the PAC and NAO’s recommendations.[footnote 7]

Government has a number of sponsorship functions for its ALBs, each with a distinct role and responsibilities.

How is sponsorship delivered?

Sponsorship requires a whole department effort. There should be a focus on forging strong and trusting relationships between the relevant individuals at all levels of the ALB and the department. This will help to ensure both that ALBs feel supported and that departments are assured of their delivery. Working together to create trust and a culture of no surprises is the foundation of good sponsorship.

Sponsorship is delivered by several actors, listed below. Section [5] provides more detail on how departments might structure themselves to deliver sponsorship in practice.

-

The Secretary of State is accountable to Parliament for the performance of each Public Body for which their department is responsible[footnote 8]. They may delegate responsibility to a junior minister.

-

The board of an ALB provides leadership, strategic direction, advocacy and independent scrutiny to both the ALB and the department. It acts in accordance with the requirements of Managing Public Money and is key to promoting an effective relationship between the sponsoring department and the ALB. The role of the board varies according to the classification of the ALB. Whereas some boards are advisory, others (usually boards of government-owned companies) also have fiduciary responsibilities [see Annex C -The Role of the Arm’s Length Body (ALB) board for further information].

-

The Principal Accounting Officer (PAO) - normally the department’s Permanent Secretary - is accountable to Parliament for the management of public money.

-

The PAO should appoint a delegated Accounting Officer (AO) to each of their ALBs.[footnote 9]

-

Routine oversight of each ALB within the departmental group should be led by a senior sponsor, normally appointed by and acting on behalf of the PAO.

-

Senior sponsors are normally supported by a team, or by an equivalent group such as a secretariat. The potential structures of the sponsorship team are described in section 5.

-

The senior sponsors accountable for managing an ALB should engage with the department’s functional leads, and work with them to ensure that the department’s ALBs have the right information, tools and capacity to adopt relevant functional standards.[footnote 7]

-

These sponsors typically oversee the strategic engagement between the department and its ALBs, working closely with the department’s functional experts and are able to call on specialist expertise as needed.

Figure 2: Table illustrating the differences between the categories of ALBs dependent on their comparable characteristics, defining roles and responsibilities

| Category | Accountable to Minister | Department policy oversight | Accounting Officer | Income sourced from department estimate | Management | Appointments | Position relative to department |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Agency | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | CEO & Non-Exec Chair | Minister- appointed CEO, Chair & Non-Exec board members | Part of the home department, established by the home department, sometimes under legislation but without a separate legal personality. |

| Non Departmental Public Body (Advisory) | Yes | Yes* | No | Yes | Independent Committee | Minister appoints members | Within department, no legal distinction |

| Non Departmental Public Body (Non-Advisory) | Yes | Yes* | Yes | Yes | CEO & Non-Exec Chair | Minister- appointed Chair and Non-Exec board members | Established and sponsored by the department with own separate legal personality, outside of the Crown |

| Non-Ministerial Department | Yes** | No | Yes | No | CEO & Non-Exec Chair | Minister usually appoints board members, though usually subject to pre appointment scrutiny by parliament. | Shares many characteristics with a department, but without a minister and acts separately from any sponsoring department. |

*Department sets a strategic framework. **Minister usually reported to, but ‘constitutional bodies’ report directly to Parliament in exceptional circumstances.

What is the scope of this Code?

This Code is for Executive Agencies or Non-Departmental Public Bodies[footnote 11] and may be applicable to Non Ministerial Departments. The code accounts for all forms and functions of ALBs (i.e. regulators, granting organisations).

Departments must exercise their discretion when determining the correct application of this document to ALBs of differing independent status under their purview. A ‘comply or explain’ approach must be adopted to facilitate this.

Departments are encouraged to apply this Code to central government public bodies as appropriate.[footnote 12]

The Code supersedes pre-existing guidance; namely, the 2017 Sponsorship Code, the 2014 Sponsorship Competency Framework, and the 2014 Sponsorship Induction pack.

The Code compliments any statutory requirements and those set out in Managing Public Money. It is consistent with, and complementary to, the Cabinet Office guidance on reviews of public bodies[footnote 13] and sets the standards for sponsorship. The Code is also issued in addition to other relevant directives such as functional standards and Dear Accounting Officer letters.

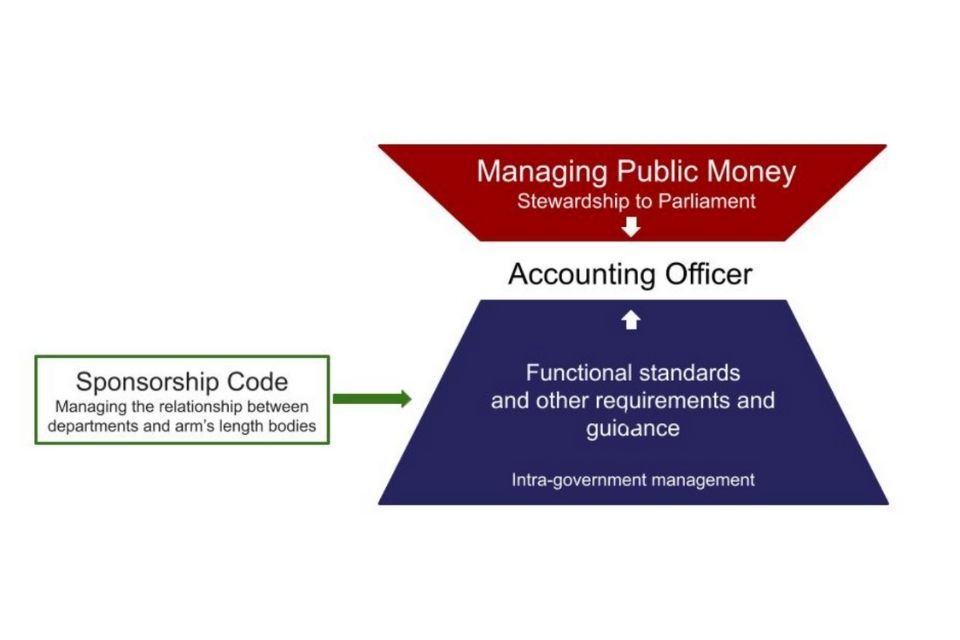

Figure 3: The Sponsorship Code supports Accounting Officers to fulfil their stewardship role for the public resources associated with the direction and management of arm’s length bodies

The Sponsorship Code manages the relationship between departments and arm’s length bodies. It feeds into the functional standards and other requirements and guidance, which supports Accounting Officers to fulfil their role. Accounting Officers also need to consider the Managing Public Money guidance.

The principles and the capabilities that underpin sponsorship

The key principles of great sponsorship are:

-

purpose: a mutual clear understanding of the purpose of the ALB

-

assurance: a proportionate approach to assurance

-

value: mutual sharing of skills and experience, and

-

engagement: open, honest and constructive relationships

Great sponsors apply these principles across six key capabilities:

- relationship management

- agreeing strategy and setting objectives

- outcome assurance

- financial oversight

- risk management, and

- governance and accountability

Central assurance of departmental sponsorship

It is important that there is a consistent level of sponsorship across different departments and their ALBs and that standards in sponsorship continue to develop and respond to the changing environment.

The Cabinet Office will provide ministers and the Civil Service Board with assurance that the effectiveness of departmental sponsorship is increased by:

- providing a tool to support departments in assuring their PAO that high standards of sponsorship are being delivered in respect of the department’s ALBs [footnote 14]

- the Cabinet Office 2022-23 Outcome Delivery Plan guidance includes two sponsorship focused metrics that offer assurance in department adoption of the Code

- number of department sponsor teams adopting the sponsorship ‘Code of Good Practice’; and

- number of departments reporting they assess their sponsorship capability as ‘emerging, maturing, or advanced’.

- a proportionate annual assurance of departments to monitor continuous improvement in ALB sponsorship capability and consistency across government[footnote 15]

- sponsorship being an integral part of ALB reviews

How should departments use this Code?

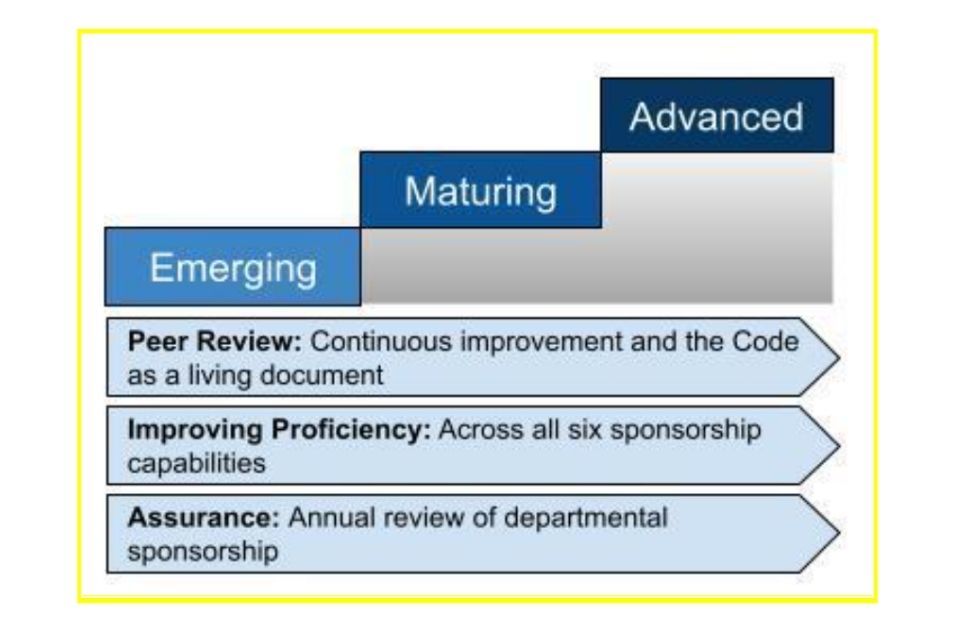

Departments should strive for continuous improvement, delivering best practice by progressing through the three maturity stages described in Box 1 below according to the priorities departments determine for their sponsorship development.

Figure 4: diagramatic illustration of the maturity model approach

The three maturity stages are emerging, maturing and advanced. They include:

- peer review: continuous improvement and the Code as a living document

- improving proficiency: across all six sponsorship capabilities

- assurance: annual review of departmental sponsorship

There is a diverse landscape of ALBs. Departments will be best placed to consider proportionality in relation to the sponsorship of their bodies. Departments should therefore look to apply the ‘comply or explain’ principle against this Code.

There may be organisations that, for a variety of reasons, are unable to fully implement the Code. A good faith attempt to apply with all aspects of the Code should be made and evidenced through a ‘comply or explain’ principle

This section sets out what effective sponsorship entails across each of the six sponsorship capabilities:

- relationship management

- agreeing strategy and setting objectives

- outcome assurance

- financial oversight

- risk management, and

- governance and accountability

Box 1: sponsorship maturity

Relationship management

Emerging

1. Engagement between the department and the ALB is ad hoc and unfocused.

2. Understanding of the ALB’s purpose within the department is limited to those officials who engage routinely with the ALB.

3. Departmental officials over-identify with the ALB’s interests and are unable to give the appropriate level of constructive challenge.

4. Trust is yet to be established between the sponsor team and the ALB and constructive challenge is limited and lacks the appropriate sharing of views.

5. Risks are not surfaced early enough to be resolved quickly and efficiently, leading to operational concerns and delays.

Maturing

6. The department and the ALB are engaging regularly, but not at an appropriate degree of seniority to be effective.

7. The ALB’s purpose is well understood within the business units of the department adjacent to the ALB’s policy area but not the wider department.

8. There is some leverage of the ALB’s expertise as part of the department’s policy development cycle.

9. Departmental officials are engaging routinely with the ALB, striking an appropriate balance between advocating for the ALB within the department and holding the ALB to account for meeting its objectives.

10. There is trust between the ALB and the department at some levels. Constructive challenge is undertaken but is ad hoc and lacks detailed understanding of ALB operations.

Advanced

11. Engagement between the department and the ALB is regular and effective at all levels at the relevant points across the department.

12. Engagement is strategic, delivering a shared understanding of risks, opportunities, ministerial priorities, and the ALB’s operating context.

13. The ALB’s purpose is communicated and understood throughout the sponsoring department at all levels of seniority and publicly.

14. Where appropriate and applicable, processes are in place to draw on the ALB’s expertise in policy development by the department.

15. Trusting, mature relationships are well established. Challenge is welcomed and is a norm in engagements.

16. Crisis management is characterised by a culture of collective responsibility, early identification and mutual problem solving.

Agreeing strategy and setting objectives

Emerging

1. The responsible minister (or PAO, if delegated) does not communicate priorities to the ALB, for example via an annual chair’s letter or direct communication.

2. There is limited engagement between the department and ALB on what success looks like, how it can be delivered and how it is measured.

3. The senior sponsor has limited engagement with the ALB in the production of its annual business plan and multi-year corporate strategy and is unable to influence its direction.

4. The ALB is insufficiently responsive to departmental priorities, to change delivery through lack of awareness or inability to flex resources.

5. The ALB’s plans to deliver ministerial objectives are not clearly articulated in an annual business plan and multi-year corporate strategy.

Maturing

6. The responsible minister (or PAO, if delegated) clearly articulates the priorities for s for the ALB

7. Senior sponsor engagement on the business plan and corporate strategy is limited to final review.

8. A vision of what success looks like, how it can be delivered and how it is measured is clearly articulated by the department to the ALB, but may be over- or under-stretching and not properly reflect ministerial priorities and/or the reality of the ALB’s operating context.

9. Priorities for the ALB from the department change frequently and can at times be inconsistent with the longer-term strategic direction and/or any statutory underpinning.

Advanced

10. The priorities for the ALB are set out in documents such as an annual chair’s letter issued by the responsible minister (or PAO, if delegated) sets SMART[footnote 16] outputs or objectives for the ALB to deliver.

11. Outputs provide a stretching but realistic target that drives continuous improvement in effectiveness and efficiency for the ALB.

12. The department and the ALB engage collaboratively on an annual business plan that sets out how these SMART outputs will be delivered, underpinned by key performance indicators that are informed by timely management information. There is a constructive yet challenging dialogue between individuals at all levels that underpins this work.

13. This document makes up the first year of a multi-year corporate strategy that sets out how the ALB’s annual outputs contribute to the delivery of longer-term impacts.

Outcome assurance

Emerging

1. There is a lack of understanding of what good delivery [operation] should look like for the ALB throughout the department. The department has limited discussions and opportunities to review and challenge the outcomes delivered by the ALB.

2. The processes implemented by the department to ensure the outcomes delivered by the ALB are not sufficiently effective or broad enough to understand its operational delivery.

3. Management information (MI) provided to the department is limited scrutiny is cursory and unsupported by relevant functional expertise, or lacks timeliness.

4. The ALB’s MI is not available to the department, or it is not scrutinised appropriately.

5. Functional support is not sought and/or provided to help scrutinise outcomes by the department and the application of functional standards is limited and not considered appropriately.

6. The department makes frequent and/or unnecessary changes to the MI that it requires from the ALB.

Maturing

7. There are discussions between the ALB and department at working level and with the senior sponsor on performance. However, there is no ‘join up’ between the ALB’s outcomes and the department’s wider governance and delivery system.

8. MI is provided to the department in a timely manner, but assurance is process driven and not undertaken collaboratively or in order to drive continuous improvement at all levels.

9. The department and the ALB agree MI reporting arrangements at the beginning of the year and minimise in-year changes to those requirements.

Advanced

10. Discussions take place at all levels, including active constructive challenge on the outcomes the ALB has delivered. These outcomes flow into the department’s wider governance, and are discussed by the departmental board. The department facilitates the ALB discussing its outcomes with bodies that constitute any wider delivery system they are part of.

11. MI is widely used to inform decision making and to drive continuous improvement at all levels. It is presented in an accessible manner and the department and the ALB consider the same versions of the ALB’s MI.

12. MI is considered at regular formal accountability meetings between the responsible minister and the ALB’s chair and between the senior sponsor and the ALB’s chief executive, as well as at working level.

13. The department and the ALB keep the effectiveness of reporting arrangements under active and critical review, and agree changes in a spirit of partnership where clear gains to the quality of the accountability and feedback loop can be achieved.

Financial oversight

Emerging

1. There is a limited relationship between the ALB and departmental finance teams - interactions only take place through the minimum required processes.

2. The PAO or relevant budget holder does not provide the ALB with a delegated authority letter at an appropriate time, hampering the ALB’s business planning.

3. The ALB goes beyond the delegated limits and budget allocations set out in the delegated authority letter and there is limited discussion on justification.

4. In-year assurance of the ALB’s financial position by the department is inadequate, either through the absence of timely and accurate financial data being provided by the ALB, or through the department not having effectively scrutinised and acted upon that data.

5. An excess of controls and approval processes: the department adds additional financial controls over the ALB, impacting on the ALB’s operational freedom and effectiveness.

6. There is a lack of engagement or information on the ALB financial position and therefore issues are not visible to the department.

Maturing

7. There are relationships at a working level between the ALB and departmental finance teams - but this does not extend to senior or board levels. Suspicion remains within the relationship about expenditure and/or the sharing of relevant data, though there is a degree of in-year spending assurance.

8. The delegated authority letter from the department to the ALB AO fails to provide the ALB with an appropriate degree of operational autonomy or the department with an appropriate degree of control.

9. The department (and Cabinet Office/ HM Treasury where applicable) sets an appropriate spending approval framework, but does not consistently deliver service standards, for example in relation to business case turnaround times, hampering the ALB’s operational delivery.

Advanced

10. There is a well established and trusting but constructively critical relationship between the ALB’s finance team and the department’s finance team at all levels. Both the ALB and the department act as ‘one team’ when it comes to significant expenditure requests, or any proposals that need to be submitted to the Centre.

11. The PAO delivers a timely and comprehensive delegated authority letter to the ALB’s AO, balancing the ALB’s need for operational autonomy with the department’s need for control.

12. Regular ‘open book’ engagement between the department and the ALB provides both parties with assurance that the ALB’s expenditure is affordable, sustainable, and within agreed limits and allocations.

13. The ALB has a good understanding of and operates in accordance with Managing Public Money and with Cabinet Office spending controls.

Risk management

Emerging

1. The ALB has limited implementation of appropriate risk management framework in accordance with the Orange Book.

2. The department does not discuss and provide clarity to the ALB as to the risks that it is willing to take to achieve objectives - its risk appetite. Alternatively, the ALB exceeds the department’s position.

3. The department has limited processes and opportunities for the ALB to routinely escalate risks to the department, or the ALB fails to employ these processes appropriately.

4. The department and the ALB do not engage at appropriate frequency on risk identification and management.

5. Risk management is largely viewed as a process-driven exercise in the department, ALB, or both.

Maturing

6. The department provides a balance of opportunity and risk to the ALB that is either too restrictive to operate delegated decision making or too lax to discharge respective accountabilities and responsibilities

7. Although there are some processes in place to routinely escalate risk from the ALB to the department, the department does not identify and deliver cross-cutting risks and mitigation strategies within the departmental family or to support ALBs in managing those risks by identifying and sharing best practice

8. The value of an effective risk management framework, including appropriate escalation, is generally understood and processes are largely proportionate.

Advanced

9. Aligned risk management processes are applied and within the department and the ALB

10. The department provides a clear and balanced risk appetite to the ALB that meets the needs of the department for control and of the ALB for operational autonomy.

11. The department and the ALB have a mutual understanding of risk, both within the ALB and of cross-cutting risks within the departmental family.

12. The department supports ALBs in managing risks by identifying and sharing best practice in risk management and by delivering cross-cutting interventions.

13. Effective risk management is seen as a key strategic tool at all levels, and is approached by the department and the ALB in the spirit of partnership and constructive challenge.

Governance and accountability

Emerging

1. Managing Public Money is not well understood nor applied by the ALB.

2. The PAO does not appoint a senior sponsor in respect of each ALB, or appoints a single sponsor to oversee an excessive number of ALBs.

3. The PAO does not prioritise resources to ensure that the senior sponsor is supported by a sponsor team, or equivalent, with appropriate capability and capacity to deliver consistently high quality sponsorship.

4. The department has insufficient processes and oversight in place to ensure good governance or accountability is in place within the ALB.

5. The department’s engagement with the ALB frequently undermines the ALB’s own governance structures and processes.

Maturing

6. The PAO appoints a senior sponsor, but they may have limited time to build and maintain an effective relationship with the ALB.

7. The senior sponsor is supported by a working-level sponsor team or equivalent, but this team may lack the capacity and capability to provide consistently high quality support to the senior sponsor.

8. The department monitors whether the ALB has met the requisite standards of governance and accountability and highlights deficiencies to the ALB’s senior leadership team at formal accountability meetings.

9. The department has named individuals in place for the departmental and ALB accountabilities set out in GovS 001, Government functions

10. The PAO is assured that the ALB is meeting the mandatory elements set out in Managing Public Money and relevant functional standards

Advanced

11. The PAO appoints a senior sponsor to each ALB and balances these appointments with senior sponsors’ other responsibilities so that each ALB receives an appropriate degree of oversight from the senior sponsor.

12. The senior sponsor is supported by a working-level sponsorship team, or equivalent, with the capability and capacity to provide consistently high quality support.

13. The PAO has confidence that the arm’s length body has a comprehensive picture of improved delivery performance, including evidence about how progress is being maintained.

Why sponsorship is essential

Effective relationships help departments and ALBs to operate as outcome delivery systems that are worth more than the sum of their parts. Sponsorship enables those effective relationships, supporting the efficient and effective delivery of public outcomes.

Sponsorship plays a vital role in providing Principal Accounting Officers (PAOs) with assurance that the ALBs for which they are accountable are operating effectively, managing and escalating risks appropriately, and operating with a high degree of probity.

Conversely, ineffective sponsorship can undermine the relationships between departments and public bodies. This can in turn have a detrimental effect on the delivery of effective public outcomes that offer value for money. For example, if a public body does not have a clear set of agreed objectives for the year, it may fail to meet the expectations of the department.

Sponsors should be supported by the Government Functions[footnote 17], resourced appropriately, and provided with impactful learning and development opportunities.

What effective sponsorship entails

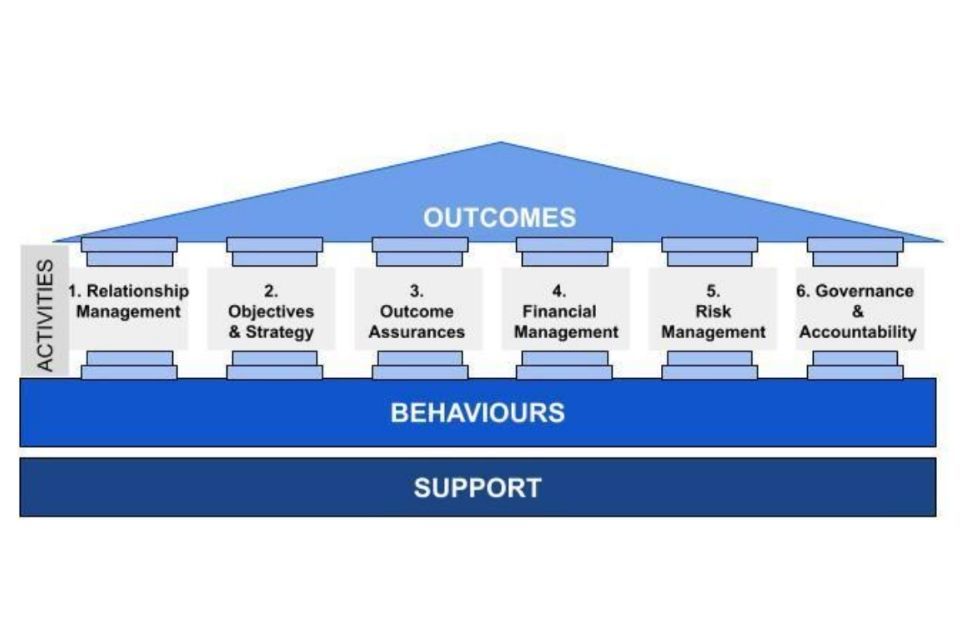

In respect of the six capabilities, this section sets out the outcomes that departments should strive for, the activities that facilitate those outcomes, and the support that is available to facilitate those activities.

Figure 5: The interaction between the key components of effective sponsorship and the six sponsorship capabilities as set out below

The outcomes are supported by 6 activities: relationship management, objectives and strategy, outcome assurance, financial management, risk management and governance and accountability. These are also supported by two components: behaviours and support.

Relationship management

At the heart of a successful partnership between the department and its ALBs are relationships, which support the delivery of efficient and effective public outcomes.

Outcomes

Departments should strive for relationships characterised by:

-

Trust;

-

Honesty and openness, and

-

Constructive challenge.

Case Study 1: 2019 collaboration between the Department for Transport (DfT) and the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) to deliver the Thomas Cook passenger repatriation

In 2019 the DfT and the CAA - the UK’s specialist aviation regulator - assisted by other organisations such as the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), collaborated closely to repatriate passengers following the financial collapse of travel group Thomas Cook.

The two organisations worked tirelessly between 23 September and 7 October 2019 to ensure that over 150,000 passengers were returned to the UK on 746 flights across 54 destinations from 18 countries. This was achieved with as little disruption as possible, and the vast majority on their originally intended day of travel. This was a significant achievement given the scale of the exercise and tight timeframe in which it was delivered.

The operation was characterised by a high level of trust between the two organisations in each other’s capabilities and that decisions would be made and put into practice in a timely manner. This is testament to the effective DfT-CAA relationship prior to the Thomas Cook insolvency; constructive and regular engagement took place at all levels, roles and accountabilities were clear and decision-making processes were mutually understood.

The successful partnership was reinforced by thorough contingency planning using their experience of the 2017 Monarch repatriation; by attention to the recommendations of an Airline Insolvency Review; and by flexibility in responding to the variety of challenges that came up during the course of the repatriation.

The insolvency of Thomas Cook was a difficult and emotional event for affected passengers and especially for staff who lost their jobs. However, the efficient repatriation and other government initiatives meant that the impact on passengers, employees and local communities was minimised. The DfT’s second Permanent Secretary, Gareth Davies, noted that this was “a great example of what government can do when it’s got a clear goal, a real sense of purpose and mission and is able to work as one team.

Case Study 2: Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) maintaining a close working relationship with The Pensions Regulator (TPR) to mitigate resource constraints

One of DWP’s major ALBs - The Pensions Regulator (TPR) - is largely funded by a levy on the private pensions industry. Facing a situation where the levy was in deficit, but the Regulator was required to implement new powers arising from the Pension Schemes Act 2021. DWP and TPR agreed that increased strategic engagement about priorities and budget allocation was required.

This engagement was built on a relationship that had developed over a number of years enabling the frank exchange of views and an understanding of the challenges and pressures each party faced. In addition to existing working level meetings and regular meetings between the Chief Executive and the responsible minister, quarterly meetings were introduced between the DWP Pensions and ALB Executive Leadership Team and TPR Senior Leadership Team.

The meetings allowed full and open discussion about strategic priorities; resource implications and where appropriate, the support that DWP specialist functions, such as commercial and digital, could offer. As a result, there was a clear and joint understanding of government priorities, and DWP and TPR were in a good position to reach agreement on how available resources should best be used to deliver those priorities over the Spending Review period.

Behaviours

The following behaviours underpin these outcomes:

-

Both parties prioritise investing in the relationship and its maturity at all levels, from the relationship between the responsible minister and the ALB’s Chair to the working-level relationships between the department and the ALB. This was particularly crucial as challenging circumstances arose.

-

A ‘no surprises’ culture existed. This enabled trust and transparency to grow between the department and the ALB. As trust grew the ALB was granted further autonomy. The ALB engaged with the department on an ‘open book’ basis.

-

The department respected the expertise of the ALB and the ALB welcomed constructive challenges from the department.

Activities that enable great outcomes and behaviours are set out below.

Activity 1

Clearly articulate accountability relationships within the departmental group, including with ALBs, in an up-to-date Accounting Officer System Statement (AOSS), including relevant roles for functional leadership (see GovS 001, Government functions)

Activity 2

Clearly articulate the nominated Accounting Officer, if applicable, and senior sponsor of each of the department’s ALBs. It may be appropriate to do so within the AOSS.

Activity 3

Publish a Framework Document that has been updated in the last three years and is based on a template published within Managing Public Money.

Activity 4

Articulate where responsibility lies for each sponsorship function - policy and corporate - of the department in relation to each of its ALBs, such as through a Terms of Reference.

Activity 5

Encourage new senior executives and non-executives in the department and in the ALB to be inducted appropriately, including by encouraging new ALB Non-Executive Directors to attend a CO-led induction event.

Support

To support them in delivering effectively, sponsor teams should draw on relevant training, in addition to the guidance referenced throughout this Code. In particular, sponsors may benefit from undertaking the following Civil Service Learning training:

-

Giving feedback - Giving and receiving feedback helps us to build authentic and trusting relationships. [footnote 18]

-

Communicating with customers Defining the four fundamental principles of professional communication. [footnote 19]

-

Influencing skills - Effective influencing skills are critical if you want to build successful relationships. Whether it’s customers, colleagues or management, find out how to adapt your influencing behaviours through an awareness of their viewpoints. [footnote 20]

-

Verbal communication - Develop skills such as crafting a compelling message and building rapport, and consider how the inflection of your voice can affect the outcome of a conversation. [footnote 21]

-

Written communication - Learn how to write effectively. [footnote 22]

-

Assertiveness - Investigate the impact of assertiveness on your day-to-day working life, as well as the most typical barriers to being assertive. [footnote 23]

Service Standards between both parties may help to strengthen this relationship. Service standards may be appropriate where both the department and the ALB believe an agreement is helpful.

A template for reaching this agreement is at Annex B. The Service Standard is not contractual and should be used only on a ‘best endeavours’ basis. It may be appropriate to monitor performance against an agreed Service Standard at meetings between the senior sponsor and the ALB chief executive or as part of an ALB review. [footnote 24]

Agreeing strategy and setting objectives

ALBs form part of departmental outcome delivery systems. Agreeing the strategy and setting objectives is a vital step in delivering outcomes.

Outcomes

Departments should strive for:

-

A unified sense of purpose and a clear mutual understanding of how agreed outcomes will be delivered;

-

ALBs that are established, and continue to exist, only when there is a clear net benefit to doing so; and

-

Clear expectations and ownership of the outputs to be delivered by the ALB with supporting management information, which - where possible - are benchmarked against those delivered by similar organisations to provide stretching but realistic targets that drive continuous improvement.

Case Study 3: Collaboration between the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and the Arm Length Body Partnership team, supporting a shared sense of purpose

The fast-moving impacts of Covid-19 restrictions (from March 2020) meant that sponsorship activity within the MoJ had to adapt to ensure changing operational objectives remained aligned to the wider department and government strategies and to actively prioritising informational support.

This opened up new opportunities to increase two-way communication with ALBs. The department was conscientious in providing a shared sense of purpose, providing practical support through data sharing and supporting decisions being made around service priorities. One of the MoJ’s ALBs set up a weekly gold command [footnote 25] meeting to co-ordinate these changes. By inviting the MoJ’s ALB partnership team, this created a unified sense of purpose and a clear mutual understanding of how agreed outcomes will be delivered.

This gave the MoJ a first-hand view of decisions being made on the ground, as well as input into how the ALB targeted its resources to navigate complex and fast-changing circumstances. Both parties actively prioritised informational support, sharing information at all levels, providing engagement and producing collaborative outputs.

Having the opportunity for regular strategic participation and collaboration promoted active dialogue which helped the partnership team craft up-to-the-minute advice to Ministers and the Permanent Secretary when required. In some instances, in advance of waiting for events to play out. This regular collaboration ensured departmental objectives were communicated in real time and ensured alignment of strategies throughout the pandemic.

Case Study 4: Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and UK Anti-Doping - National Anti-Doping Policy

In 2019 DCMS started working with UK Anti-Doping (UKAD) to revise and update the UK’s National Anti-Doping Policy.

The document, owned by the government, sets out the roles and responsibilities around anti-doping activities in the UK. It aimed to meet the requirements of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Convention against Doping in Sport while ensuring that the World Anti-Doping Code is implemented in the UK. However, the policy had not changed since its introduction in 2009 when UKAD was established. The UK’s policy was in need of updating to reflect significant developments in anti-doping, education and the latest World Anti-Doping Code.

DCMS worked with UKAD to identify areas of the *policy requiring revision, and launched a six week public consultation in late 2019 on how these could be updated. The results of the consultation were analysed by both organisations, and a process of iterative discussions took place to agree the new policy. This involved further consultation with stakeholders from across the sport sector, and close collaboration between DCMS and UKAD to consider, agree and finalise changes.

The result was the publication in April 2021 of the updated UK National Anti-Doping Policy. The most significant update was the introduction of a new Assurance Framework through which sports can formally demonstrate their compliance with the policy, reflecting the need for greater clarity over responsibilities apparent through the consultation. Roles and responsibilities of organisations involved in anti-doping were updated, and additional organisations added to make the policy more comprehensive.

The result was a policy that is helping sports organisations better understand and meet their anti-doping responsibilities, and the UK is better able to meet its international obligations.

Behaviours

The following behaviours underpin the outcomes:

-

Both parties were conscientious in providing a shared sense of purpose and fostering a culture of support.

-

Both parties provided practical and informational support through sharing data, providing engagement and producing collaborative outputs, defining clear expectations and highlighting the ALB’s contribution to the department’s aims.

-

Both parties promoted active dialogue that is constructive yet challenging thereby creating a respectful working environment.

Activities

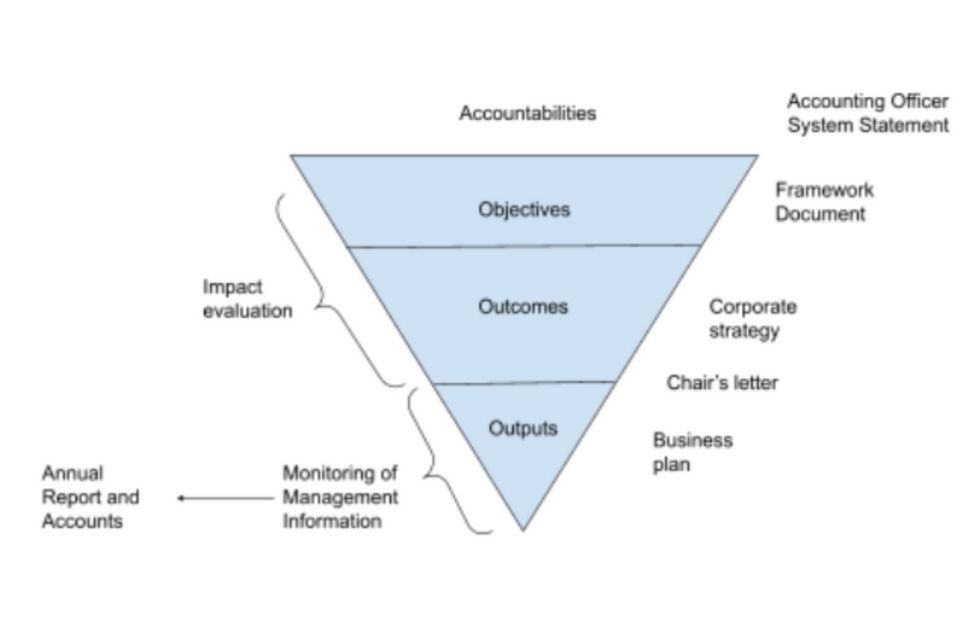

Figure 6: The hierarchy of documentation that the department should employ in agreeing the ALB’s strategy and setting its objectives

Figure 6 provides an illustrative timeline for producing and agreeing this documentation.

Activity 1

Clearly articulate:

-

The ALB’s purpose and objectives in the Framework Document, consistent with those agreed in the business case for the ALB’s establishment, where applicable, and with any relevant enabling legislation.

-

The ALB’s purpose and objectives should be linked to departmental priorities, including the ALB in the department’s Outcome Delivery Plan.

-

Short-term outcomes in a published multi-year corporate strategy, informed by an annual Chair’s Letter, issued by the relevant Minister or Principal Accounting Officer to the ALB Chair.

-

Immediate delivery outputs in a published annual business plan.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to measure the ALBs performance against the Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (SMART) outputs agreed between the department and the ALB.

Activity 2

Implement procedures or mechanisms to draw on the expertise of the ALB in departmental policy-making.

Activity 3

Explore opportunities to cluster similar ALBs - within or outside of the departmental group - and to benchmark their performance, setting realistic but stretching targets that promote the efficient and effective delivery of public outcomes.

Activity 4

Ensure an assessment is made about how well the department and its ALBs are currently meeting functional standards, and their ambition for meeting them more efficiently and effectively in the future; embed actions about continuous improvement into business plans.

Activity 5

Sponsorship teams should triage proposals by policy teams to establish new ALBs before engaging the Cabinet Office’s Public Bodies Team, in line with the Public Bodies Handbook Part 2 - the Approval Process for New Arm’s Length Bodies. [footnote 26]

Support

To support them in delivering effectively, sponsor teams should draw on relevant training, in addition to the guidance referenced throughout this Code. In particular, sponsors may benefit from undertaking the following Civil Service Learning training:

-

Collaboration across departments, government and Beyond - Supports civil servants in building and maintaining relationships and maximising the value of collaboration. [footnote 27]

-

Communicating and negotiating policy with influence - Supports civil servants in influencing and negotiating with different stakeholder groups as part of policy development and implementation. [footnote 28]

Sponsor teams should draw on expert support within their departments, including from the private office of the responsible minister.

Outcome assurance

Departments should act as critical friends to ALBs, offering support and challenge in the delivery of outcomes informed by timely Management Information (MI).

Outcomes

Activities that enable great outcomes and behaviours are set out in the checklist below.

Activity 1

A shared understanding at all levels as to how well the ALB is meeting its KPIs.

Activity 2

-

Require ALBs to ensure that they undertake longer-term outcome and impact evaluation.

-

Require ALBs to publish appropriate information on outturn delivery against KPIs within the ALB’s Annual Report and Accounts.

-

Ensure that appropriate arrangements are in place to allow the findings of impact evaluations to influence departmental policy decisions as part of the policy development cycle. [footnote 29]

Shared outcomes across clusters of ALBs that operate within broad ‘outcome delivery systems’; where joined up working helps minimise cost and increase benefits for the user.

Activity 3

A continuous improvement culture where learning lessons is primary and ‘blame allocation’ is avoided.

Case Study 5: The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and their ALBs outcome focussed approach to assurance.

Each year the MoJ makes an evidence-based assessment of the “meaningful oversight” necessary for each of the ALBs. These are based on the nature and level of risks faced in the year ahead and how these may impact on delivery against the MoJ’s Outcome Delivery Plan (ODP).

To inform the assessment, engagement with ALBs is undertaken across all levels and with a range of policy and functional colleagues. This ensures a shared understanding as to whether the ALB is meeting the performance that is expected of it, that KPI’s are being met, and that risks are being effectively managed. Consideration of where and how the department can best support ALB delivery of essential statutory functions is made and determines the optimum, risk-based and proportionate oversight and assurance arrangements for the year ahead.

The findings are reported to the MoJ’s Audit and Risk and Executive Committees and outcomes from this exercise are used to put in place bespoke oversight and support arrangements for each ALB, proportionately targeting our higher risk ALBs. Enhanced oversight arrangements include increased “holding to account” meetings, tailored engagement and delivery of targeted risk-reducing initiatives. The risks, strategic themes and prioritised projects identified through this process are reviewed throughout the year at regular holding to account meetings.

Through this process we ensured effective oversight and assurance of ALB delivery and risk management fostering a continuous improvement culture where learning lessons is primary and ‘blame allocation’ is avoided. We act as critical friends to our ALBs, holding them to account for delivering agreed outcomes informed by timely Management Information.

Behaviours

The following behaviours underpin the outcomes:

-

Both parties prioritised an outcomes focussed approach; the ALB was open with its management information (MI) and strived to provide it in a timely and an accessible manner. The department was supportive of this approach and appreciated the limitations of what the MI told it.

-

The department and the ALB fostered a culture of open communication; communicating any problems and solutions, both through formal reviews, the recommendations coming from them, and informally on an ongoing basis. The department should also identify cross-cutting problems and support ALBs in solving them.

-

When things went wrong both the ALB and department looked to problem solve rather than apportion blame

Activities that enable great outcomes and behaviours are set out in the checklist below.

Activity 1

Hold ALBs to account for delivering their objectives through regular discussion of timely Management Information (MI) linked to output KPIs.

Activity 2

Ensure that:

-

ALBs undertake longer-term outcome and impact evaluation.

-

ALBs publish appropriate information on outturn delivery against KPIs within the ALB’s Annual Report and Accounts.

-

that appropriate arrangements are in place to allow the findings of impact evaluations to influence departmental policy decisions as part of the policy development cycle. [footnote 30]

Activity 3

In the Framework Document, agree a mechanism for sharing the ALB’s MI with the department.

Activity 4

Support the delivery of ALB reviews in line with Cabinet Office guidance, and the implementation of recommendations or actions coming from them. [footnote 31]

Support

To support them in delivering effectively, sponsor teams should draw on relevant training, in addition to the guidance referenced throughout this Code. In particular, sponsors may benefit from undertaking the following Civil Service Learning training:

- Performance indicators - Performance indicators help government departments understand how well a policy, programme, project or service is performing against expectations. This training covers the setting and use of targets and the use of outcome-based indicators, benchmarking, and the balanced scorecard approach. [footnote 32]

Sponsor teams should draw on expert support within their departments, including from their corporate governance teams, relevant functional leads, and operational delivery teams.

Sponsor teams should draw on relevant functional expertise, and understand the need to meet functional standards in a way that is proportionate and appropriate to the work being done by an Arm’s Length Body. Multiple functional standards - for example, GovS 002, Project Delivery and GovS 008, Commercial - support the successful, timely, and cost-effective delivery of government policy objectives.[footnote 33] Any analysis to support decision making should follow GovS 010, Analysis.[footnote 34]

Financial Oversight

ALBs, like other public sector organisations, should follow the guidance on handling public funds that is contained within Managing Public Money (MPM) and augmented by ‘GovS 006, Finance’ where appropriate. This Code is secondary to MPM.

The Principal Accounting Officer (PAO) is accountable to Parliament for the stewardship of their organisation’s resources. They may delegate responsibility for the operations of an ALB to an Accounting Officer (AO) within that body, but their personal accountability remains unchanged.

An understanding of the breadth of legal responsibility of the board and the ALB, including how such legal and financial responsibilities also affect and relate to the Accounting Officer’s direct responsibility to Parliament for the ALB.

Outcomes

Departments should strive to:

-

Assure their PAOs that ALBs within the departmental system spend public money with high levels of probity, delivering value for money.

-

There is a clear process with the ALB Board, department and the Accounting Officer (AO) to ensure appropriate engagement in the budgeting process.

Case Study 6: The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) Assurance of Financial Oversight

The MoJ Sponsorship team identified that one of its ALB had received a number of negative audit opinions, therefore raising concerns about their compliance with financial controls and functional standards.

Striving to assure the department’s Principal Accounting Officer (PAO) that the ALB spent public money in a manner that was delivering value for money, the sponsorship team worked closely with the finance functional leads to understand the rationale for the negative audit opinions and to design a specific improvement plan to support.

Working as a partnership between the Sponsorship team and functional leads, the department was able to articulate what good would look like and what steps the department could perform to help the ALB. This included providing dedicated financial support and associated interim resourcing as well as an enhanced offer of training on financial controls from functional leads, and deeper and broader engagement on financial issues via more focused partnership activities

This led to improved audit opinions and strengthened departmental assurance of the ALB’s financial processes and governance arrangements. This in turn provided the assurance that was required for both the department’s PAO and the ALB’s Accounting Officer (AO).

Case Study 7: The Home Office (HO) example of Financial Oversight Function of an Arm’s Length Entity (ALE)

One of the HO Arm’s Length Entities (ALE’s) required assistance from the department to provide an independent element in assessing quotations for a research project which had been put out to tender.

In considering who in the department was best placed to fulfil this function, the ALE identified the Home Office Sponsorship Unit (HOSU) as it considered that it possessed the relevant skill sets. The relevant Team Leader in the unit was approached and agreed to assist in the process.

The Team Leader, utilising their acquired knowledge and subject matter specialism around sponsorship (e.g. finance, commercial), was able to effectively support the ALE in assessing the quotations and contracts were awarded accordingly.

The ALE was grateful for the input from HOSU and the expertise that the Unit was able to bring to assess the quotations and award the contract. Both parties were able to utilise the strong relationship which had been established, with HOSU remaining respectful of the ALEs autonomy and independence, while balancing the departments need for oversight of Financial Oversight assurance.

Behaviours

The following behaviours underpin the outcomes:

-

Both parties prioritised an open, frank and conscientious relationship at all levels, ensuring guidance on handling public funds that is contained within Managing Public Money (MPM) and augmented by ‘GovS 006, Finance’ was adhered to.

-

A culture of regular engagement was promoted; providing both parties assurance that the ALB’s expenditure was affordable, sustainable, and within agreed limits and allocations.

-

Both parties were respectful of the ALBs operational autonomy in balance with the department’s need for oversight and assurance.

Activities that enable great outcomes and behaviours are set out in the checklist below.

Activity 1

Implement proportionate oversight arrangements to assure the PAO that the ALB has the systems and processes in place to reach high standards of probity in handling public funds.

Activity 2

Ensure that the financial and operational freedoms provided to the ALB by the department are clearly articulated in a delegated authority letter from the PAO or relevant budget holder to the AO, which should also set out budget limits.

Activity 3

Support ALB business planning to assure the PAO that the ALB’s financial plans are sustainable and affordable, in addition to delivering agreed outcomes.

Activity 4

Support ALB leaders to meet functional standards.

Support

To support them in delivering effectively, sponsor teams should draw on relevant training, in addition to the guidance referenced throughout this Code. In particular, sponsors may benefit from undertaking the following Civil Service Learning training:

- Awareness of finance in government - Learn about the processes used to manage, monitor and report financial operations to deliver value for money to the taxpayer.

Sponsor teams should draw on expert support within their departments, including from their Corporate Governance or Financial Governance Teams or equivalent and from their Internal Audit Team.

Where sponsor teams encounter ALB spending proposals that may be novel, contentious, or repercussive, they should engage their Permanent Secretary’s office and then consider whether it would be appropriate to engage the relevant spending team or the Treasury Officer of Accounts at HM Treasury.

Sponsor teams should call upon the function leaders within the department, and ensure that relevant functional standards are followed when functional work is involved. For example,

-

The Finance Functional Standard is likely to be relevant to the effective management of public funds.

-

The Commercial Functional Standard is likely to be relevant when undertaking procurement.

-

Sponsor teams should pay due regard to the Counter Fraud functional standard in managing fraud, bribery, and corruption risk in government.

-

Sponsor teams should refer to the debt functional standard when managing debt owed to the government.

-

Sponsor teams should likewise adhere to the grant functional standard to support them in delivering effective and efficient grant-making.

Risk management

Sponsors play a vital role in overseeing the ALB’s management of risk. The Orange Book: Management of Risk – Principles and Concepts sets out the main principles underlying effective risk management in departments and Arm’s Length Bodies.[footnote 43] This Code is subordinate to the Orange Book.

Outcomes

The department should strive for:

-

Risks that are well understood, managed and appropriately escalated.

-

An appropriate assessment and management of opportunity and risk with clarity over the risks that the ALB is exposed to and willing to take to achieve its objectives - its risk appetite.

-

Confidence in the response to risks and transparency over the principal risks faced and how these are managed balances the needs of the department for oversight and of the ALB for operational autonomy.

Case Study 8: The Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) and a shared understanding of risk management

The DWP wanted to ensure all its bodies had a shared understanding of risk, a better understanding of the department’s risk appetite and that the impact on the department of ALB risks was clear.

To enable this, DWP instigated regular forums of the chairs of each body’s Audit and Risk Assurance Committee (ARAC). These were attended by the senior sponsor and the department’s NEDs responsible for risk oversight alongside members of the department’s central risk team.

These quarterly fora fostered a collaborative culture, enabling bodies to share common risk themes, raise items of common interest and share the outcomes of broader horizon scanning exercises looking at less likely but high impact risks. Discussions have also been informed by Annual Assurance.

Assessment and the regular reporting to departmental ARAC and have supported a mutual understanding of this both within the individual ALBs and of cross-cutting risks within the departmental family.

The fora have prioritised an appropriate risk appetite, building stronger links within the audit and risk functions across the bodies and enhancing the links with the central departmental teams. This has resulted in a better understanding of the overall risk landscape.

Case Study 9: The Department for Education (DfE) and a shared understanding of risk management

The DfE was keen to lead a collaborative approach to system risk management working with its Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs).

Supported by sponsor teams and allowing for greater collaboration on areas of shared risk affecting multiple organisations, System Risk Reviews were undertaken to enable cross-organisational discussion of system level risks (including Devolution of Accountability, T Levels and Data Sharing and Quality) with actions agreed. The department and ALBs were able to identify, manage and mitigate system level risks and share risk information, intelligence, professional expertise and best practice.

Creating an open and transparent approach to sharing risk information between the department and its ALBs fostered a culture of collaboration in which all parties were respectful of one another’s risk appetite and able to account for this within their own respective appetite.

Through DfE’s commitment to resource the work, including a dedicated experienced System Risk Manager and team, the risks were well understood, communicated and stakeholder engagement plans agreed with actions monitored, evaluated, managed and appropriately escalated, creating an appropriate risk appetite that balanced the needs across the ALB landscape and those of the department.

The positive culture of collaboration within risk management resulted in the establishment of the ALB Risk Leads Network in May 2021 where best practice and risk expertise continue to be shared and provide a platform in which all can seek advice and support.

Behaviours

The following behaviours underpin the outcomes:

-

Both parties prioritised a mutual understanding of risk. Roles and responsibilities for risk management were clear and supported effective governance and decision making at each level, both within the ALB and of cross-cutting risks within the departmental family.

-

The department fostered a collaborative culture; supporting ALBs in identifying, managing and mitigating risks. They also looked to understand if and how risks of an ALB may impact other ALBs both within their department and the wider ALB landscape.

-

Both parties were respectful of one another’s responsibilities, delegations and governance, accounting for these in their respective risk management frameworks.

Activities that enable great outcomes and behaviours are set out in the checklist below.

Activity 1

Implement a proportionate process for updating the department on the ALB’s risk assessments and risk management strategies.

Activity 2

Regularly and openly discuss the department’s risk appetite with the ALB.

Activity 3

Implement an effective risk escalation structure. Escalation from the ALB’s Audit and Risk Assurance Committee to the ALB’s board and then to the department’s Audit and Risk Assurance Committee or other appropriate committee is likely to be appropriate.

Activity 4

It may be appropriate for the ALB to invite departmental representatives to attend the ALB’s Audit and Risk Assurance Committee or other risk management structures as observers from time to time.

Activity 5

The ALB should avoid escalating an excessive number of risks to the department. Doing so could undermine the clear lines of accountability that exist between the Department and the ALB, within which it is the responsibility of the ALB to manage its own risks. Likewise, the Department should avoid intervening excessively in the ALB’s risk management structures.

Support

To support effective delivery, sponsor teams should draw on relevant training, alongside the guidance referenced in this Code. In particular, sponsors may benefit from undertaking the following Civil Service Learning training:

-

Risk management - Identify and understand the types of risks you may encounter, how they may be addressed and how managing them effectively can lead to organisational improvement.[footnote 44]

-

Managing risks, issues and dependencies - Learn about what risk is (its cause, effect and impact) as well as effective ways to manage it.[footnote 45]

Sponsor teams should draw on expert support within their departments, including from their Corporate Governance or Financial Governance Teams or equivalent.

Sponsor teams should also draw on relevant functional expertise. The finance functional standard is relevant to risk management and assurance.[footnote 46]

Governance and accountability

As with central departments, Parliament expects ALBs to operate to the highest of standards of professionalism and probity. Ministers are responsible for the performance of their ALBs and PAOs for ALBs’ stewardship of public funds. Ministers and PAOs should be provided with appropriate assurance in relation to those points, including through the provision of appropriate scrutiny.

Outcomes

Departments should strive to:

- Assure their PAOs that ALBs within the departmental family - operate effectively and to a high standard of probity, meeting the requirements set out in Managing Public Money.

Case Study 10: The Department for Work and Pensions flexible approach to partnership working

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) sponsors three regulators, money guidance and pensions bodies and advisory committees for which sponsor arrangements are centralised.

Small Grade 7 led partnership teams support each of the department’s public bodies, supporting the Head of the Division as senior sponsor. A centralised Public Appointments Team within the Division is responsible for administering the public appointments process on behalf of Ministers and provides recruitment expertise. This structure creates a centre of expertise with partners and the public appointments team supporting and learning from each other. Each partnership team has a relationship with the policy leads for their public bodies which span DWP, HMT, BEIS, DEFRA, DLUHC and MoD so it is essential that senior sponsors and partner teams build effective working relationships across the whole system. As well as day to day engagement, policy leads join the formal quarterly accountability review meetings with each body. These meetings provide an opportunity for strategic discussion on delivery against strategic objectives and business plans, risk and Financial Oversight.

There are also relationships with the functional leads within the Department, for example Finance, Commercial, People and Capability, Communications, Security, Parliamentary, Digital, Legal, Analysis mapping onto the functional standards. A Central Assurance Team deals with issues that apply across all of DWP’s bodies, and also acts as the central focus point for engagement with Cabinet Office.

This approach to prioritising a relationship that consistently delivers high quality support creates a more flexible approach to partnership working, tailored to suit the needs of each individual body, while ensuring consistency across DWP’s bodies, assuring the Principal Accounting Officer (PAO) that ALBs within the departmental family are operating effectively and to a high standard of probity.

Behaviours

The following behaviours underpin the outcomes:

-

The department prioritised a relationship that consistently delivered high quality support. The senior sponsor was supported by a sponsorship team or equivalent with appropriate capability and capacity.

-

A culture of active assurance is central to activity. The ALB supported early conversations about governance and accountability activities.

-

Both parties were respectful of the assurance required by the PAO and AO.

Activities that enable great outcomes and behaviours are set out in the checklist below.

Departments should note that the governance requirements for Executive Agencies and for Non-Departmental Public Bodies vary. For example, some Executive Agencies are not required to lay an Annual Report and Accounts (ARA) before Parliament each year.

Activity 1

Ensure that the ALB challenges [or requires] the ALB to have:

-

A management board or equivalent that meets at least four times annually and that includes appropriate non-executive representation.

-

A Terms of Reference for each board sub-committee, which should be reviewed annually.

-

A Schedule of Delegation setting out the delegated responsibilities of each sub-committee.

-

A published Annual Report and Accounts, if required, that is laid before Parliament annually.

-

A schedule of meetings and an attendance register for the board and each of its sub-committees that is published in the governance statement of the ALB’s Annual Report and Accounts, which should be laid before Parliament annually.

-

Completed an annual board Effectiveness Review and, at least triennially, an externally-led board effectiveness review.[footnote 47]

-

Completed annual appraisals of non-executive members led by the Chair and that the senior sponsor or an appropriately senior departmental official has completed an annual appraisal of the Chair.

-

A Diversity Action Plan

-

A board Operating Framework or Terms of Reference, or equivalent in place, which should be reviewed annually.

-

A board Operating Code in place, which should be published and reviewed biennially.

-

A clear conflicts of interest policy and a register of interest that captures the interests of all board members. These documents should be published and reviewed regularly.

-

A whistleblowing policy in place that is consistent with the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

-

Integrated the management of functional work into its overall management arrangements, to meet functional standards.

-

A business continuity plan within the annual business plan.

Activity 2

Support early conversations between the Chair, your department’s appointments team and your ministers about succession planning for board appointments, and the planning/running of individual appointment campaigns.

Activity 3

The department and ALB should provide mutual support in undertaking Parliamentary and public engagement, including in responding to requests made under the Freedom of Information Act, Parliamentary Questions, and Ministerial Correspondence.

Support

To support them in delivering effectively, sponsor teams should draw on relevant training, in addition to the guidance referenced throughout this Code. In particular, sponsors may benefit from undertaking the following training:

-

Governance, assurance and audit - Explores the issues involved in governance, assurance and audit and how these interrelated subjects should be handled to manage and mitigate risk both across government and in ALBs.[footnote 48]

-

Essential corporate governance - Looks in detail at the role of boards in delivering good governance, the regulatory landscape and key responsibilities for directors.[footnote 49]

Sponsor teams should draw on expert support within their departments, including from their Corporate Governance Team[footnote 50] or equivalent.

How to deliver good practice in ALB sponsorship

Leadership of the department’s sponsorship of its ALBs

PAOs should appoint a senior sponsor to oversee the department’s relationship with each of its ALBs. The PAO should consider how many ALBs it would be appropriate for a single senior sponsor to oversee. This assessment should be based on the budget, risk profile, or political significance of the ALB and on the senior sponsor’s other responsibilities. The senior sponsor is responsible for ensuring that activities across the six capabilities are met in respect of the ALBs for which they are senior sponsor.

The overriding requirement is that the senior sponsor is able to dedicate the necessary time to executing their responsibilities fully.

Senior sponsors may be supported in delivering this responsibility by a sponsorship team, secretariat, or equivalent, in addition to the department’s functions e.g. its finance, HR and commercial teams. This section sets out how departments may structure themselves to provide this support.

Sponsorship functions and models

Functions

The government has a number of distinct sponsorship functions for its ALBs. For ALBs of any complexity and/or scale there should be an articulation of the relevant sponsorship functions. Each sponsor’s role and responsibilities should be set out in the framework document.

A sponsorship function should have sufficient and dedicated resource, and effectively represent the government’s interests relating to their role. It must work closely with other functions to ensure a unified departmental approach.

Sponsorship functions may be divided into two broad areas: policy and corporate sponsorship, (also characterised as the shareholder function for certain ALBs).

-

Policy sponsor: this function relates to what ALBs deliver on behalf of the government. It is responsible for agreeing ALB purpose and strategy, setting policy outcomes aligned to ministerial and government priorities and assuring delivery of those outcomes.

-

Corporate sponsor (also known as ‘shareholder’ for certain ALBs): this function relates to how ALBs perform and deliver, including risk and financial oversight, governance, and accountability. UK Government Investments (UKGI) is the government’s centre of excellence in corporate governance in government, and performs the shareholder function for a number of complex ALBs. As per MPM, departments should consider whether UKGI is best placed to deliver this function for their ALBs or, if not, seek the advice and use the expertise of UKGI during the life of such arm’s length bodies.

Project sponsor (also known as client or customer) relates to what and how ALBs deliver projects and programmes. It represents the department’s interests as the recipient of the ALB’s services or function. It specifies and holds the ALB to account for delivery of the project. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) is the government’s centre of expertise for sponsorship of major projects and programmes.

Clarity of roles between policy and corporate sponsorship is important to achieve success for ALBs of complexity or scale. Where this is not beneficial to the performance and management of the ALB, departments should retain the flexibility to deploy different operating models depending on their ALB and departmental construct.

Models

No two departments structure their sponsorship teams in precisely the same way, however, department approaches may be grouped into three broad models based on how responsibility for delivering each function is apportioned. They are as follows:

-

Centralised model: Where the policy and corporate sponsorship functions are delivered by separate teams in separate business units.

-

Hybrid model: Where policy and corporate sponsorship are delivered separately but within the same business unit.

-

Decentralised sponsorship model: Where the same team discharges both the policy and corporate sponsorship functions.

The model of the departmental sponsorship of the ALB should align with both the objectives of the ALB and enable the department to provide support and oversight. For example designing the ‘how’ of support around the ‘why’ of the ALB.[footnote 51]

Across each model functional experts either deliver on behalf of or support the delivery of corporate sponsorship functions. Sponsorship should never seek to be delivered in a vacuum - it requires engagement at appropriate levels to the relationship across the department.

Co-sponsoring

Co-Sponsoring is an extraordinary process and is the act in which two (or more) departments may wish to sponsor one ALB.

Where co-sponsorship is considered, clear lines of accountability should be defined with a single department sponsoring each ALB. Memorandums of Understanding (MoU) governing the relationships between the ALB and other departments or ALBs should be in place.

The co-sponsorship relationship can support the delivery of departmental objectives. (Including sharing learning with partners across the whole of the UK, including devolved administrations, to deliver better outcomes for citizens).

Capability of the sponsor team

The nature of sponsorship of ALBs varies widely. Tables 1, 2, and 3 summarise the support available to help new, experienced and senior sponsors, respectively, to learn and develop in their roles.

The department should facilitate the exchange of knowledge and expertise between departments, the department and the ALB, and between ALBs. It may be appropriate to do so by facilitating staff loans, convening forums and networks where best practice can be discussed and relevant information disseminated, as well as undertaking/supporting ALB reviews and the implementation of review recommendations.

Bibliography

-

12 Principles of Governance for all Public Body NEDs, March 2021.

-

Arm’s Length Body Boards: Guidance on Reviews and Appraisals, 2022.

-

Central Oversight of Arm’s Length Bodies, NAO, 2021 (pdf, 444 KB).

-

Code of Conduct for Board Members of Public Bodies, 2019.

-

Government Functional Standards and associated guidance, 2020.

-

Public bodies Handbook - Part I, 2016.

-

Public Bodies Handbook - Part II, 2016.

-

Public Bodies Landing Page, GOV.UK

-

The Green Book; Central Government Guidance on Appraisal & Evaluation, 2022.

The Orange Book; Management of Risk - Principles and Concepts (pdf, 462 KB), 2004.

Glossary of terms

Accounting Officer

[See Principle Accounting Officer] This role is delegated to other Senior Civil Servants as required.

Accounting Officer System Statement