An in-depth review of fire-related fatalities and severe casualties in England, 2010/11 to 2018/19

Updated 16 May 2023

Applies to England

Foreword

I am very pleased to provide the foreword to this report.

Over recent decades there has been a substantial and welcome reduction in fire-related fatalities and casualties in England. Fatalities from fires in the home have in recent years been at historically low levels. This has not been the result of a single change or intervention but by a combination of many factors influencing the overall risk of fire. The continued focus on prevention including the work undertaken by fire and rescue services across the country have played an important role in this overall reduction.

It is imperative that, despite the reductions in fire related fatalities over the years, we must not lose sight of the impact of each specific case and the distress fires, particularly fatal fires, invariably cause. This report talks necessarily of numbers and frequencies, but the heart-breaking reality behind each incident and behind each number must not be forgotten. The Grenfell Tower fire in 2017 brought this into stark relief and, together with the many individual cases also included in the report, clearly demonstrate how devastating fire can be.

It is key that all work on fire prevention must be informed by evidence of what works. We need to know what the dangers are, who is at risk and, despite the efforts of everyone involved in fire safety, why we still have people losing their lives to fire. This report helpfully builds our collective understanding of the circumstances around fatal fires. By adopting two approaches – a statistical review of many years of fire incident data and an in-depth analysis of one year of fire investigation reports – this research provides a rounded look at common themes, repeating patterns and emerging issues. These can be taken, considered and used to inform local and national fire prevention activity.

The overall success should be celebrated, but we must not get complacent, and all involved need to continue to work together to reduce these individual tragedies further. This report will only serve to support that.

This report has only been possible due to the support of local FRSs and the NFCC in collating the relevant data and information and providing expert input throughout. We are grateful to them for their help in supporting this important study.

Sarah Gawley, Interim Director of Fire

Acknowledgements

The authors (Alexandra Bartlett, Isabel Preston, Molly Watts) would like to thank the fire and rescue services that took the time to provide fire investigation reports, to the National Fire Chiefs Council Home Safety Committee for their assistance in designing and promoting the research.

Thanks to Professor Andrew Clark and Dr Julie Mytton for peer reviewing the final report.

Thanks also go to all members of the fire and rescue analysis programme and policy teams who either took part in the analysis or contributed to the review and drafting process.

Executive summary

The vast majority of fires attended by fire and rescue services (FRSs) in England do not result in loss of life or serious injury. However, an average of 5 people a week died in a fire in England in the year ending 31 March 2019. As the tragic events at Grenfell Tower in June 2017 showed, fires can still result in multiple fatalities and many other adverse outcomes.

While the number of fire-related fatalities has declined markedly from a peak of 755 since current records began in 1981 to 251 in the year ending March 2019, it is important to keep knowledge and understanding of the profile and circumstances of fires which result in a fatality up to date, to inform prevention activity and further reduce the numbers of fire-related fatalities.

This report presents findings from research designed to provide an in-depth analysis of fire-related fatalities in England. It also considers whether fires that result in severe casualties are notably different from those that result in fatalities and thus whether a different approach to reducing non-fatal casualties is required.

Research aims

The aims of this research were to:

- better understand of the circumstances of fires that result in fatalities and severe casualties

- examine the risk across the population of being a severe casualty or fatality of fire

- understand the differences between fatal fires and fires which result in a severe casualty

- explore the behaviours of fatal victims of fires, leading up to and during the fire

- assess the consistency of fire investigation reports and provide recommendations for best practice for documenting fire-related fatalities going forward

Research design

This research comprised two parts:

- in phase one, Home Office Incident Recording System (IRS) data were analysed to explore the circumstances of fires involving a fatality or severe casualty in the years ending March 2011 to 2019. Historical data on fires involving all non-fatal casualties (not just severe) were also examined to understand the overall trend in fires and casualties

- in the second phase, fire investigation reports (FIRs) were analysed to explore the behaviours of victims and circumstances of fatal fires in the year ending March 2017

Phase 1: Findings from the IRS

The first phase of the research considered the overall trend in fire-related fatalities and severe casualties, then analysed IRS data to show:

- the prevalence of such fires

- where and when fatal and severe casualty fires occurred

- what types of fires resulted in fatalities and severe casualties

- the profile of fatal and severe casualty victims

Trends in fire-related fatalities and severe casualties

When comparing the number of fires against the number of fatal and non-fatal casualties, the trend showed that fires, fatalities and non-fatal casualties had been decreasing over time. However, comparing the rates of severe casualties and fatalities per 10,000 fires, the rate of fatalities in fires increased whereas the rate of severe casualties remained the same.

In the years ending March 2011 to 2019 there were:

- 2,356 fatal fires which involved 2,637 fatalities1

- 5,128 severe casualty fires which involved 5,817 severe casualties

Notes:

- For the purpose of publications, figures include the number of fatal casualties which were either recorded as ‘fire-related’ or ‘don’t know’. Of the 2,637 fatalities, 283 (11%) were classified as don’t know as to whether these were fire-related.

There were many similarities between the characteristics of fatal and severe casualty fires such as in the high levels of prevalence in and around residential properties, fires involving older people living alone, and fires occurring more frequently in deprived areas. However, there are some key differences that demonstrate that the circumstances around fatal fires are often distinct from severe casualty fires, as summarised in Table 1 and discussed below.

Table 1: Summary of most prevalent factors in fatal and severe casualty fires, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019

| Circumstance | Fatal fires | Severe casualty fires |

|---|---|---|

| WHERE THE FIRE OCCURRED | ||

| Location | Dwellings (1,808 fires, 77%) |

Dwellings (3,696 fires, 66%) |

| Property type | House (943 fires, 52%) |

House (1,713 fires, 51%) |

| Fire start location | Living room (685 fires, 38%) |

Kitchen (1,195 fires, 66%) |

| WHEN THE FIRE OCCURRED | ||

| Season | Winter (711 fires, 30%) |

Summer (1,328 fires, 26%) |

| Time of day | Afternoon (630 fires, 27%) |

Evening (1,590 fires, 31%) |

| WHAT TYPE OF FIRE | ||

| Motive | Accidental (1,827 fires, 78%) |

Accidental (4,070 fires, 79%) |

| Source of ignition | Smoking materials (590 fires, 25%) |

Cooking appliances (1,117 fires, 22%) |

| Item first ignited | Textiles, upholstery and furnishings (1,127 fires, 48%) |

Textiles, upholstery and furnishings (1,792 fires, 35%) |

| VICTIMS | ||

| Gender | Male (1,637 victims, 62%) |

Male (3,823 victims, 66%) |

| Age | 65 or over (1,071 victims, 41%) |

45 to 64 (2,827 victims, 33%) |

Where did fatal and severe casualty fires occur?

There were differing numbers of fatalities and severe casualties across the country, but not necessarily linked to the actions of FRSs in these areas. Local factors, for example age profile of residents and building composition, could have contributed to the likelihood of fires and, at a more local level, fatal and severe casualty fires occurred more frequently in areas of high deprivation.

Analysis of fire start location and property type showed fires involving a fatality or severe casualty most often occurred in indoor locations and specifically in residential buildings. The most common room of origin for fatal dwelling fires was the living room, whereas it was the kitchen for severe casualties. Fatal other building fires occurred more frequently in residential properties such as a residential home, whereas severe casualties most frequently occurred in industrial premises. Road vehicle fires that involved a fire-related fatality or casualty were relatively infrequent and generally occurred in cars. Outdoor fires that involved a fatality or severe casualty were rare but were most likely to occur close to a building or structure.

When did fatal and severe casualty fires occur?

Time of day, day of week, and the season in which fatal and severe casualty fires occurred can be important to consider when determining appropriate shift patterns and the timing of fire safety messaging. The pattern is different for fatal and severe casualty fires. Fatal fires more often occurred during winter months, with little variation based on the day of the week or time of day. Severe casualty fires occurred evenly throughout the year, but more often in the afternoon/evening. No trend in the time of day fatal fires occurred suggests there are not the same links to activities such as cooking, as there are with severe casualties.

What types of fires resulted in fatalities and severe casualties?

The IRS collects data on how fires started, the presence of a working smoke alarm and some limited information on whether drug and/or alcohol use was believed to have contributed to the fire. This, together with data on the behaviour of the fire itself, such as spread, provides a useful indication of the types of fire which resulted in a fatal or severe casualty.

While there was a higher risk of severe casualty than fatality in all fires, the risk of fatality and of severe casualty in smokers’ materials fire are almost equal. For both severe casualty and fatal fires in buildings, the item first ignited was most often textiles, upholstery and furnishings. Fatal and severe casualty fires rarely spread beyond the room of origin or item first ignited. There was a working smoke alarm present in about half of all fatal and severe casualty dwelling fires and in most fires in residential buildings. The absence of a working smoke alarm increased the risk that a household would be involved in a fatal or severe casualty fire.

What was the profile of fatal and severe casualty victims of fire?

Limited information is collected in the IRS on the victims of fire however the data that is available can be used to explore differences in the risk for different gender and age groups. The analysis found older people are more likely to die in a fire than the average for the general population, while the risk profile is more variable for severe casualties. Males are more likely than females to die or experience a severe casualty in a fire.

Phase 2: FIRs for the year ending March 2017

While the IRS data can give some initial indication of activities and behaviours at the time of fire, FIRs provide a more in-depth understanding and authoritative account of the circumstances of fatal fires. There were 185 fatal dwelling fires involving 201 victims in the year ending March 2017, for which there was an available FIRs.

Fire discovery and escape

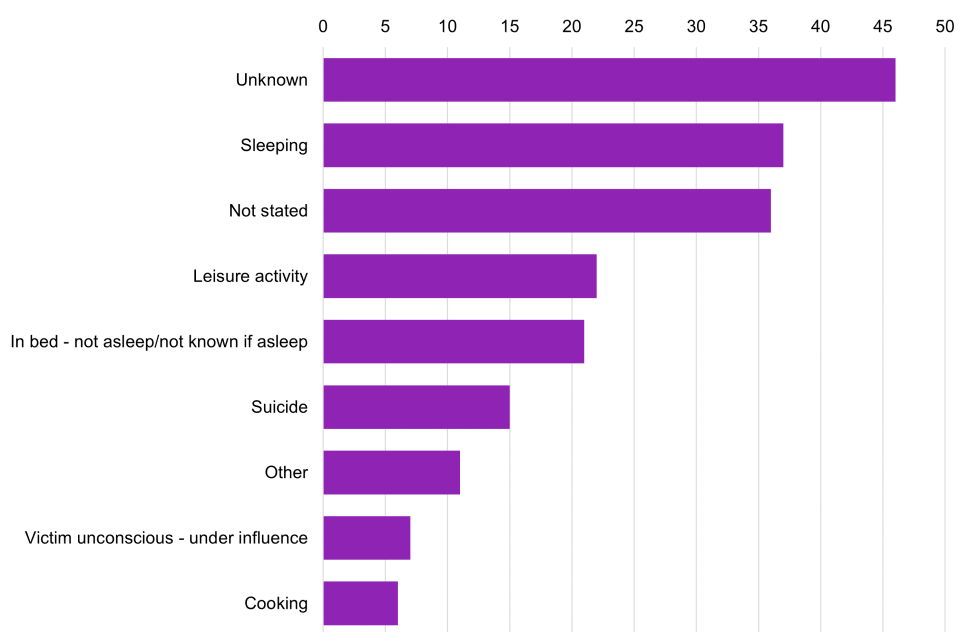

When a fire is discovered and the timeliness of notifying the FRS influences its outcome. Victims’ activities at the time of fire, such as whether they were asleep, is therefore often a very important factor in the potential outcome of the fire, along with their actions upon discovering the fire, and any actions of witnesses.

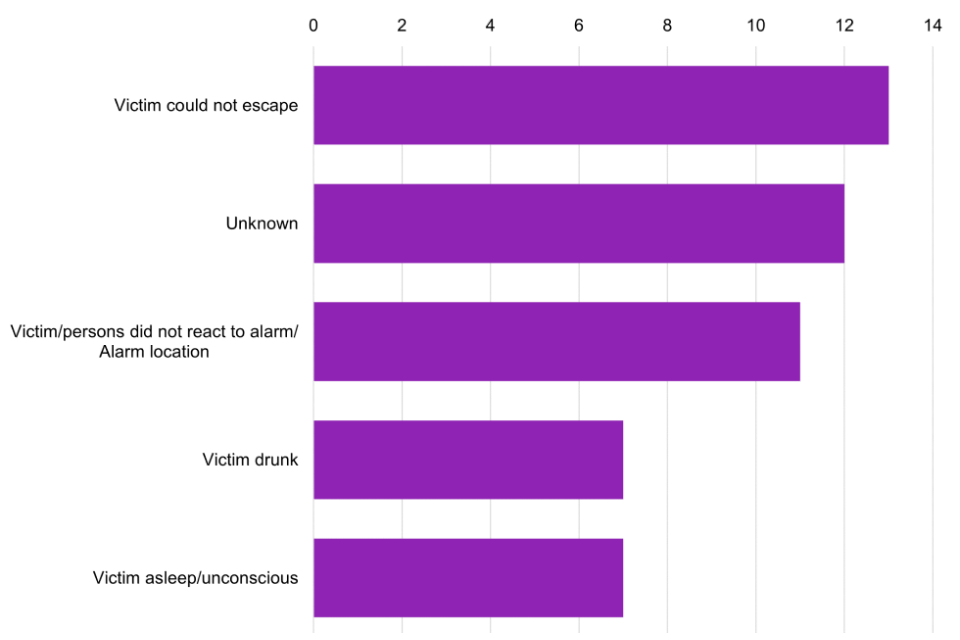

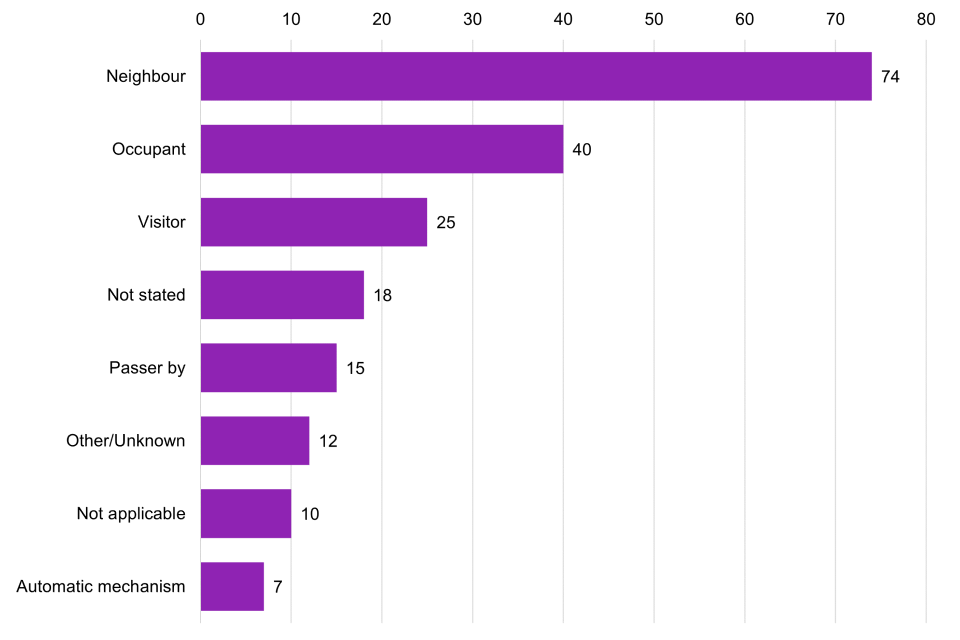

Victim activity at the time of fire is difficult to establish and therefore often recorded in the FIRs as unknown, but where known, victims were often asleep at the time of fire (37 victims). A large proportion of the fatal fires (81 of 185) took place where a smoke alarm was present, and in 13 cases where the alarm activated but the victim could not escape. A substantial number of victims (88 victims) discovered the fire themselves, and the first person who attended the fire, other than the victim, was a neighbour. The first action by first responders was often to raise the alarm by calling 999 (in 67 instances). Many victims (83 of 201) were found in the room where the fire started suggesting they could not escape, largely due to impairment or being on fire themselves.

Impact of impairments on the outcome of the fire

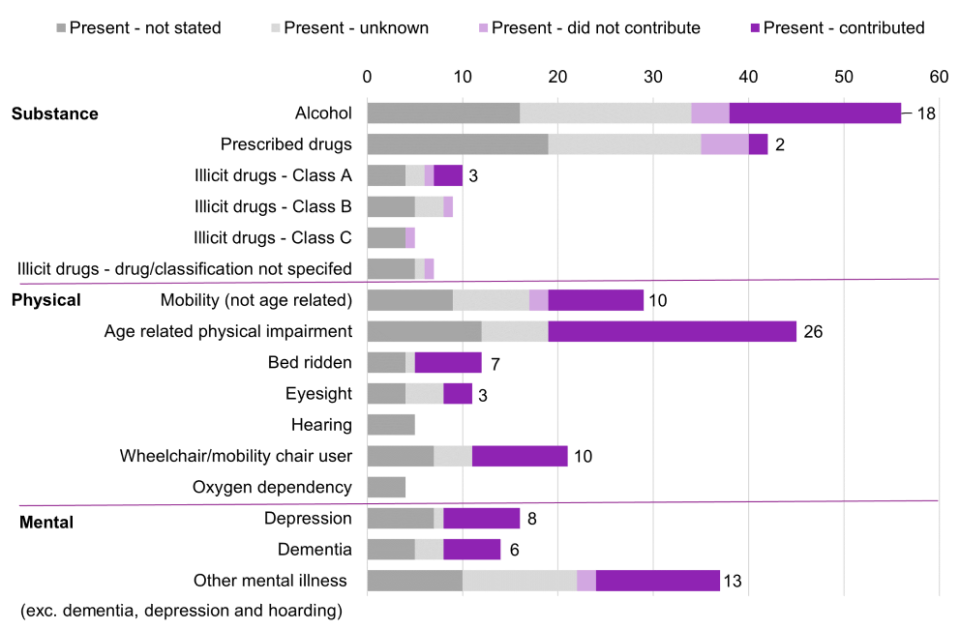

Many of the fires involved those who had pre-existing impairments. The impairments were often stated as a factor in both the starting of a fire and the outcome. Impairments were categorised in the analysis under three major areas:

- physical – such as mobility-related impairments

- mental – such as dementia or hoarding

- substance use – such as the use of prescribed or illicit drugs

Most victims (123 of 201) had some level of overall impairment that may have affected their response to the fire. An impairment was not stated or unknown in many cases (57 of 201) and some (21 of 201) had no impairment at all. Physical impairments were prevalent among a notable number of the individuals (43 of 201), and this was sometimes combined with a mental impairment (16 of 43) or a substance-related impairment (7 of 43). For 71 individuals, the impairment was considered to have contributed to starting the fire or the outcome.

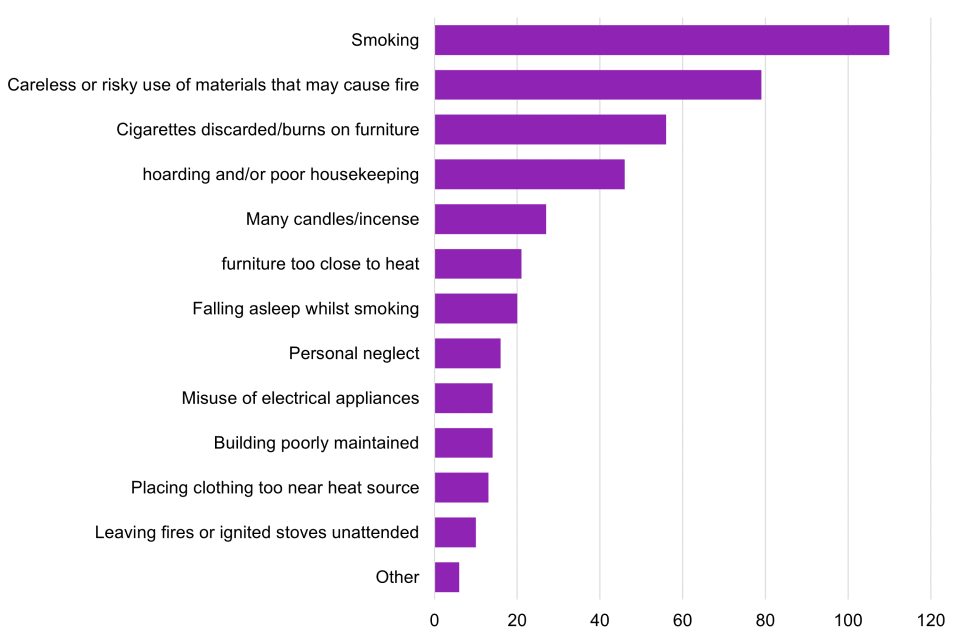

History of potentially unsafe fire behaviours

As a large proportion of fires (145 of 185) were identified as being caused by human behaviour, the risk of a fatal fire could potentially be mitigated against by spotting unsafe fire behaviours early. The most common potentially risky behaviour was smoking (110 victims), along with discarding cigarettes inappropriately (56 of 201 victims), and careless or risky use of materials that may cause fire (79 victims). There were some cases of hoarding and poor housekeeping among fatal fire victims, which may have contributed to the outcome of the fire (46 victims).

Contact with FRSs and other agencies

One way in which unsafe fire behaviours can be identified and mitigated against before a fire occurs is through contact with FRSs and other agencies. Over a quarter of victims (56 of 201) were in a care environment and 32 (of 201) individuals had specific contact with FRSs prior to the fire. This includes 26 victims who had a Home Fire Safety Check (HFSC) and 6 who had smoke alarms fitted by the FRS.

Suicide, arson and accidental self-immolation

It can be difficult to determine if an individual has deliberately set a fire and if they intended to commit arson or suicide. It is important to understand these incidents though, as their prevention requires a different approach compared with accidental fires.

In the fires with the motive recorded as deliberate (27 of 185), 16 were suicide, 2 were arson, and the intention was unknown or not stated in 9. In the 16 fires where the cause was suicide, accelerant was used in 11 of them.

In 21 fires, the victim accidentally set themselves on fire, but these were not considered to be linked to suicide or arson. In 9 of these instances, smoking materials was the source of ignition.

Common fatal fire scenarios

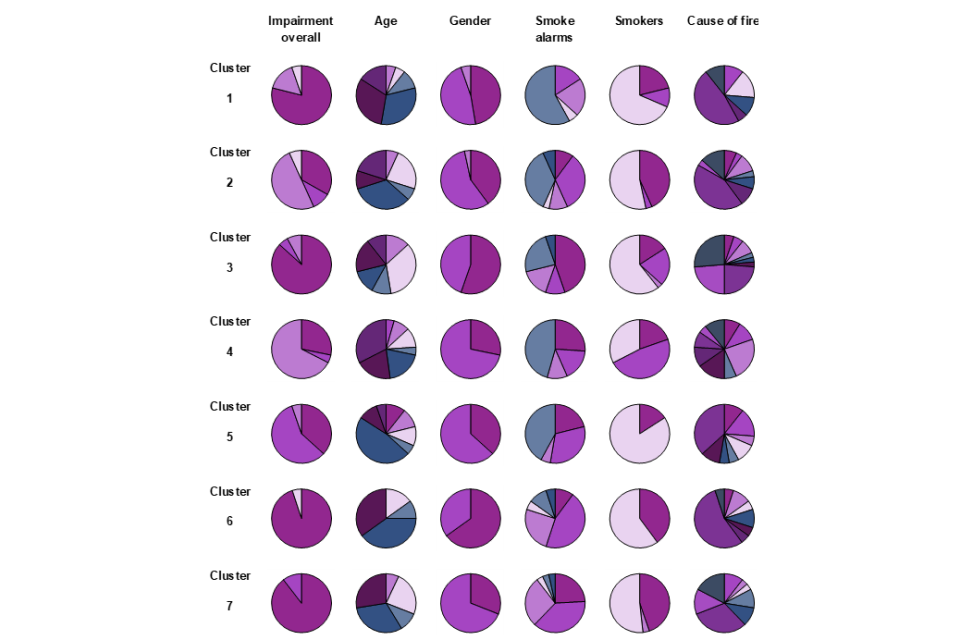

The overall analysis showed that while there were some similarities between fatal fire incidents, there were a lot of different factors that might have affected the outcome. Cluster analysis was used to identify common fatal fire scenarios in the FIRs for the years ending March 2011 to 2019 by grouping similar fires and victims together. Seven groups were identified in this analysis:

- vulnerable individual with working smoke alarm

- individual under the influence of alcohol and smoking

- individual with mental impairment

- fires caused by misused heating devices and poor housekeeping

- single male falls asleep while smoking

- single female falls asleep while smoking

- male with impairments in mixed circumstances

Discussion

The profile of fatal fires has stayed relatively consistent since undertaking previous detailed research. Older age, the presence of an impairment such as physical disability, living alone, smoking and alcohol use remain key risk factors, and this is similar for severe casualties.

FIRs provided a good amount of detail to support development of fire safety initiatives; however, there are currently large differences in the type of information and level of detail captured in the reports. Ensuring all reports record key data consistently, and sharing this information between FRSs, will help to improve understanding of fire-related fatalities and aid faster identification of emerging risks. Similarly, more consistent recording of information in the IRS would allow for more reliable analysis of victim and household profiles at a national level.

Analysis of the FIRs found it was not uncommon for a working smoke alarm to have been present and active in a fatal fire. This shows the importance of considering fire safety measures other than smoke alarms where particular risks are identified. Such measures could include working with other agencies, such as social care, to ensure the usage of fire-safe materials in the property, particularly bedding, and installation of fire suppression systems. This is particularly important for those with both age and non-age-related physical impairments, or for those known to misuse substances or alcohol who will be less able to respond quickly to a fire.

As 26 individuals had previously had a home fire-risk check, it is evident that people at risk are being identified by FRSs; however, given that a further 86 individuals not recorded as having previous contact with FRSs were identified as having some level of overall impairment, there could be more to do to reach those potentially at risk or vulnerable. It would be useful to explore this further and improve the evidence base on the effectiveness of different interventions.

1. Introduction

The vast majority of fires attended by fire and rescue services (FRSs) in England do not result in loss of life or serious injury. However, an average of 5 people a week died in a fire in England in the year ending 31 March 2019 and, as the tragic events at Grenfell Tower in June 2017 showed, fires can cause multiple fatalities and many other adverse outcomes.

While the number of fire-related fatalities has declined markedly from a peak of 755 since current records began in 1981 to 251 in the year ending March 2019, it is important to keep knowledge and understanding of the profile and circumstances of fires which result in a fatality up to date to inform prevention activity and further reduce the numbers of fire-related fatalities.

This report presents findings from research designed to provide an in-depth analysis of fire-related fatalities in England. It also considers whether fires that resulted in severe casualties were notably different from those that resulted in fatalities, and thus whether a different approach to reducing non-fatal casualties is required.

1.1 Aims

The aims of this research were to:

- better understand the circumstances of fires that result in fatalities and severe casualties

- examine the risk across the population of being a severe casualty or fatality of fire

- understand the differences between fatal fires and fires which result in a severe casualty

- explore the behaviours of victims of fatal fires, leading up to and during the fire

- assess the consistency of fire investigation reports (FIRs) and provide recommendations for best practice for documenting fire-related fatalities

2. Background

The last published in-depth review of fatal fire data in England was conducted in 2006 on behalf of the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) (now Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities – DLUHC). To contextualise the findings from the current research, we have identified key papers on fatal fire research since 2006. This section describes the DCLG commissioned paper, key papers published since with a focus on fatal fires in the UK and compares these to international findings.

2.1 DCLG research into fatal fires (2006)

Research conducted by Greenstreet Berman in 2006, on behalf of DCLG, analysed 535 FIRs from the period 2001 to 2006 to identify the characteristics and behaviours of those most at risk of fatal fires (Smith & Wright, 2006). The research identified that over half of the victims of fatal fires were over the age of 50, despite representing less than half of the population. In addition, careless use of smoker’s materials was responsible for almost half the fires, and there was a high level of mental and/or physical impairment among the victims, particularly age-related impairments. The research also indicated that household type – particularly being a single adult, and even more so a lone older person – was associated with fatal residential fires, along with use of alcohol and cigarettes, especially amongst middle-aged persons, but less so amongst older people.

2.2 Fatal fires in the UK

Limited robust research has been conducted into fire-related fatalities since 2006 (Clark, et al., 2015; Turner, et al., 2017). In an extensive review of academic literature, Clark et al. (2015) demonstrated that compared to other areas such as crime, illness or risk-associated activities such as smoking, there was limited research exploring the behaviours and characteristics of those involved in fires. Similarly, in a large-scale systematic review looking into risk factors associated with unintentional house fires, injuries and deaths, Turner et al. (2017) identified only 11 suitable papers. All papers in the systematic review were rated as medium or low quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for literature reviews where the research reviewed is not experimental (Wells, et al., 2011).

Despite the low-quality ratings identified in the Turner et al. (2017) systematic review, the research concluded with findings consistent with the DCLG study that older residents were at increased risk of injurious fires. It was, however, also found that properties with higher numbers of older residents were significantly less likely to experience a fire in the home.

Overall, the number of fire-related fatalities per year has decreased over time (Bryant & Preston, 2017). Home Office research identified a few key factors that could be associated with a reduction in fatal fires in England, including an increase in households with working smoke alarms; a downward trend in smoking, drug and alcohol use; improved safety standards, including regulations for furniture and furnishings; and FRSs’ preventative work and fire safety education. Conversely, it was suggested that an increasing, ageing population, and increased overcrowding in homes could act as an upward pressure on these trends.

2.3 Fatal fires internationally

The downward trend in fires and fire-related fatalities, and the profile of fatal fire victims, was mirrored internationally (Harpur, 2014; Doyle, et al., 2019; Giebułtowicz, et al., 2017; Sadeghian, et al., 2019; Jonsson, et al., 2015; Xiong, et al., 2015; Winberg, 2016; Ahrens & Evarts, 2017). In a review of published national statistics from 42 countries, Winberg (2016) found that both USA and Great Britain have reduced the number of fire fatalities most significantly over the past three decades, and now have a lower fire death rate per capita compared with their home country of Sweden. It concluded that, unlike in Sweden, USA and Great Britain have introduced enhanced fire regulations for furniture and furnishing.

Despite noting issues in comparing international statistics, due to varying reporting styles, the Fire Service Academy in the Netherlands compared the statistics for nine European counties and found a common risk profile (Fire Service Academy, 2018).

Besides age, gender, and physical and mental impairment characteristics, most studies have linked measures of deprivation, such as low income, with a relatively high prevalence of fire. This includes a study of 189 countries using World Health Organisation and World Bank data that found a statistically significant link between a nation’s income level (including Gross Domestic Product per capita, Gross National Income per capita, and Gini) and the number of fire-related fatalities (Peck & Pressman, 2013).

Further to this, two recent studies used cluster analysis to show the combinations of factors associated with fatal fires (Jonsson, et al., 2017; Coates, et al., 2019). Coates et al. (2019) used coroner’s data to find common co-occurrence of factors such as age, disability, and presence of medications or alcohol in blood. Similarly, in a study of fire-related fatalities in Sweden, Jonsson et al. (2017) used cluster analysis to identify six common case studies of fatal fires:

- fatalities typically involving older people, usually female, whose clothes were ignited

- fatalities involving middle-aged (45 to 64 years old), often intoxicated men, where the fire usually originated from furniture

- fires caused by technical fault, started in electrical installations in single person households

- fires caused by cooking appliances left on

- fires with unknown cause, room and object of origin

- deliberately set fires

Alternative prevention activity, other than smoke alarm installation, aimed at those who are most at risk of fatal fires was recommended in a few papers, for example residential sprinkler system installation. This, it was argued, would be more suited to people who are older or have disabilities (Coates, et al., 2019). Better co-operation between various public services such as FRSs, psychiatric clinics and other social services was also suggested (Jonsson, et al., 2017).

2.4 Comparing severe casualty and fatal fires

The behaviour of individuals leading up to and during a fire, and their ability to respond, can influence the outcome of a fire. A study by the Fire Service Academy in the Netherlands, investigated the difference between fatal and non-fatal casualties in 56 fatal fires and 152 non-fatal fires (Kobes, M. & van den Dikkenberg, 2016). Using fire service data collected at fires alongside a survey of survivors, the research found key factors associated with fatal rather than non-fatal casualties. These were the ability to respond to the fire, for example being awake or having mobility, and the position of the fire in relation to exits. When exploring fire response, the time between the fire starting and the fire service being notified was considered a more important factor than the time it took for the fire service to arrive on scene once they had been notified.

2.5 Conclusion

While there is a lack of recent research on fatal fires, the available studies consistently identified age, the presence of an impairment such as physical disability, smoking and alcohol use as key factors. This study’s analyses of national fire data will help understand if these patterns still hold in England. The literature is less clear on whether these factors are different to those in a non-fatal fire. In addition, the data analysed in identified literature does not fully explore the behaviours of the individuals in fatal fires.

3. Research design

In order to fully understand fires involving a fatality and the behaviours of those involved, this research comprised two parts:

- in phase one, Home Office Incident Recording System (IRS) data were analysed to explore the circumstances of fires involving a fatality or severe casualty in the years ending March 2011 to 2019. Long-term trends were also explored using historical data

- in the second phase fire investigation reports were analysed to explore the behaviours of victims, and circumstances of fatal fires in the year ending March 2017

In addition, to contextualise the findings of the research, key publications were reviewed as discussed in Chapter 2.

3.1 Phase one

Phase one analysed IRS data to understand the circumstances of fires that result in fatalities and severe casualties. A range of analysis techniques was used to understand the differences between these types of fires, and to examine the risk across the population of becoming a severe casualty or fatality of fire.

3.1.1 Data sources

The data used in this report included:

- data on fires involving casualties, and the national population, for years ending March 1982 to 2019

- detailed incident and victim data on fatal and severe casualty fires from the IRS for years ending March 2011 to 2019

- FRS population data from years ending March 2010 to 2018 provided by the Office of National Statistics (ONS)

- indices of multiple deprivation (IMD) data for years ending March 2010 and 2015 published by the Ministry of Housing and Local Government (MHCLG) (now called Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities),

- English Housing Survey (EHS) data for the year ending March 2019 published by MHCLG

Prior to the IRS, casualties were reported as either fatal or non-fatal. Since the Home Office introduced the IRS, casualties in fires have been defined by injury severity:

- precautionary checks recommended (precautionary checks)

- first aid given at scene (first aid)

- victim attended hospital as an out-patient (hospital slight)

- victim went to hospital and stayed overnight as an in-patient (hospital severe)

- fatality

Further information on these sources is in Appendix A. Definitions and terminology used in this report match those used in published statistics unless specified. Please see the definitions guidance for fire statistics for more information.

3.1.2 Analysis

The analysis conducted was primarily descriptive to show the frequency of factors associated with fatal and severe casualty fires. This covered overall numbers of fires, fatalities and non-fatal casualties since the year ending March 1982. The circumstances of fatal and severe casualty fires were then explored from the year ending March 2011 onwards. The latter included building or location type, fire start location, time of day and day of week, and household type. Further analysis explored included local variation, links to deprivation, further circumstances of fire such as source of ignition, cause of fire and fire spread, and victim characteristics including age and gender.

Given fatal and severe casualty fires are relatively rare, data for the years ending March 2011 to 2019 were combined to produce a large enough number to draw meaningful conclusions.

3.1.2.1 Regional analysis

The local variation in where fatal and severe casualty fires occurred were explored using population data at an FRS level and deprivation data. Rates of fatal and severe casualty fires, in relation to population, were mapped to visualise differences between FRS areas. This was done by taking the total number of these fires per year in each FRS area and dividing it by the population for each FRS in each year. These were then averaged to account for year-on-year fluctuations.

Each fire was mapped according to X and Y coordinates logged at the time of the fire to its relative deprivation area score using ArcGIS® software by ESRI1. These deprivation areas were divided into ten equal groups (or deciles) according to their deprivation rank across England. The total number of fires per decile was then calculated to understand the correlation between fires and each level of deprivation.

Notes:

- ArcGIS® and ArcMap™ are the intellectual property of ESRI and are used herein under license. Copyright © ESRI. All rights reserved. For more information about ESRI® software, please visit www.esri.com.

3.1.2.2 Further circumstances of fire analysis

Details on the source of ignition, cause of fire and spread of fire were analysed by calculating the number of fatal and severe casualty fires per 1,000 fires. The presence and functionality of smoke alarms were explored by calculating the frequency of fatal and severe casualty fires in which they were present. In addition, EHS data on smoke alarm ownership across England were used to calculate the relative risk of fatality or severe casualty when a working smoke alarm was present.

3.1.2.3 Victim analysis

Victim age and gender were analysed using relative risk analysis to understand if particular age groups or genders were at greater risk of fatal or severe casualty fires. This analysis compared the rate of occurrence for a specific group to that of the whole population. For instance, the relative risk of a fire fatality for females per age group was calculated by dividing the rate of fire fatality per million population for each age group by the rate of fire fatality in the general population (total male and female population of all age groups). The average risk for the general population is 1.0. A value higher than 1.0 demonstrates a higher risk of a fire fatality. In this analysis, multiple victims from the same fire were analysed separately.

3.2 Phase two

Phase two of the research focussed on exploring the behaviours of fatal fire victims leading up to, and during the fire, and assessing the consistency of FIRs and provide recommendations for best practice for documenting fire-related fatalities going forward. Only dwelling fires – fires that happen in the home – were included in this analysis, as these are where most fatal fires occur and where the fire service can have the biggest impact within the current legislation.

3.2.1 Reports

To undertake in-depth analysis, FRSs were asked to provide FIRs for fatal fires in dwellings for the year ending March 2017. The year ending March 2017 were chosen for analysis as finalising FIRs can take longer than one year, meaning the reports offered the most recent and complete sample.

A total of 203 FIRs were provided by 39 FRSs in England. Three FRSs could not supply the information (primarily due to the investigation having been undertaken by another agency such as the police, or a formal FIR not being written as it was covered via a witness statement or Coroner’s report not held by the FRS). A further 3 FRSs did not experience any fatalities during that year. There were 18 fatal fires identified in the IRS data but excluded from the research either due to the fatality not being fire-related or the report not being received. Investigation reports for 185 fires relating to 201 victims were therefore used in the analysis.

Building on previous research and reading a sample of 40 fatal fire investigation reports provided by London Fire Brigade, a data collection framework with approximately 100 variables was developed to extract information from the reports. Cambridgeshire FRS piloted this framework which covered information routinely recorded in the IRS plus further details outlined in ‘Additional information covered in FIRs’ below.

Once the database was finalised, all reports provided were read and coded. If 2 or more victims were in a fire, each victim was coded separately. As per General Data Protection Regulation protocols, FRSs were requested to redact all personal information from the reports before sharing them with the Home Office. Further details on the information collected and data analysed is available in Appendix B.

Additional information covered in FIRs

Further circumstances of fire: Including property tenure, detail on deliberate fires, detail on item first ignited, victim activity at the time of the fire.

Fire discovery and escape behaviour: Including presence and function of smoke alarms, victim’s response to fire including escape behaviour, and other individuals’ response to fire, including calling 999 and attempting to rescue the victim.

Presence and impact of impairments: Including whether the victim was mentally or physically impaired, whether they were a substance user, and whether these were considered to have contributed to the fire or outcome.

Previous history of victim: Including evidence of unsafe fire behaviours, and if the individual had any previous contact with the FRS or other agencies.

3.2.2 Analysis of FIRs

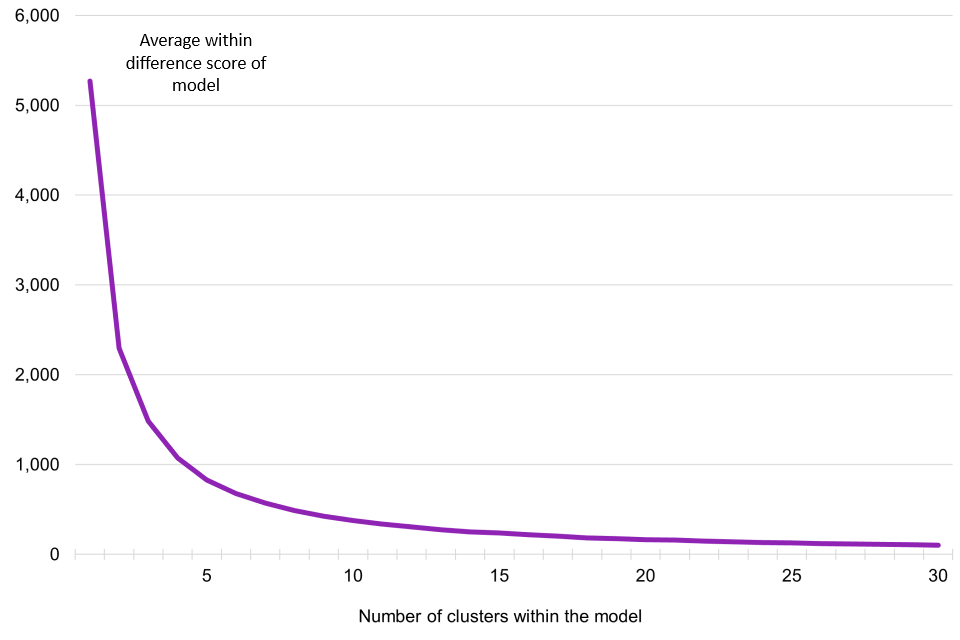

The frequency of all factors was analysed to understand if the fatal fires in the year ending March 2017 were similar to those analysed in phase one, and to understand the prevalence of circumstances, behaviours and impairments in fatal fires. Further to this, K-modes cluster analysis was conducted to identify fatal fire scenarios that can target fire safety initiatives (This analysis used R along with the package klaR).

K-modes analysis groups categorical data into ‘clusters’ of characteristics, behaviours and circumstances which are often observed together. Using R software, the analysis was run iteratively to find the number of clusters that best suited the data and with the least number of observable differences within each cluster. Further information on this approach is in Appendix C. Descriptive analysis on the dominant characteristics, behaviours and circumstances observed in each cluster were then used to develop the fatal fire case studies.

3.3 Background literature

In order to identify relevant literature that would help contextualise the findings of the further research, key papers that covered fire-related fatalities were identified from an existing database of fire-related research. Forwards and backwards citation searches identified additional relevant papers. In addition, broad search terms identified further papers using online databases including Google Scholar, JSTOR, Springer, Science Direct and EBSCOhost (search terms were iterative but included “Fire” AND (“Fatal” OR “Death” OR “Casual*”). Searches focussed on identifying national level research, or systematic reviews, that would give context to the overall profile of fire-related fatalities or severe casualties.

This method identified 63 papers. Only those published since 2006 were included in the review as this was the last time that research similar to phase two of this report was published in England (Smith & Wright, 2006). Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and 37 were excluded as being out of date, briefing rather than research based, technology focussed, for example methods of scene investigation, or case studies of major events such as major industrial incidents. Eight were identified as contained within a systematic review already included. Information on scope, methodology and key findings of each of the papers were extracted and summarised for the report (see Chapter 2).

4. Findings from the Incidents Recording System

This section first explores the long-term trends in fire-related fatalities and severe casualties using data from the IRS (see ‘Recording of fatalities and casualties in the IRS’ additional information below for more detail). An in-depth review of factors associated with fatal and severe casualty fires is then presented by exploring the location of fatal and severe casualty fires, timing, types including source of ignition and spread of fire, and the profile of victims of fatal and severe casualty fires. Key findings are presented and further detail along with data tables can be found in Appendix D.

Recording of fatalities and casualties in the IRS An incident record from a fire is generally completed by one of the firefighters on scene shortly after an incident. These records can then be updated with further information and for fatalities is updated once a fatality has been confirmed, or the cause of death is established. This can be some time after an incident if, for example, an individual later dies from complications as a result of an injury in the fire, or an investigation is held into the cause or circumstances of the fatality such as an inquiry.

Firefighters are asked to record if the fatality or injury is fire-related, and where this is not immediately clear it is coded as ‘don’t know’ in the IRS. For the purpose of Home Office publications, a fire-related fatality includes those that were recorded as ‘don’t know’. Casualties are those resulting from a fire, whether the injury was caused by the fire or not. FRSs are asked to update the information once known and figures are revised in each statistical publication.

The figures in this report include records of incidents up to and including 31 March 2019 that had reached the IRS by 26 September 2019, when a snapshot of the database was taken for the purpose of analysis.

4.1 Trends in fire-related fatalities and severe causalities

As the population is rising it could be expected that there would be more fires, as they are generally caused by human behaviour, and, in turn, more fatal and non-fatal casualties. Despite a rising population however there has been a long-term downward trend in fires, fatalities, all non-fatal casualties, and specifically severe casualties since the 1980s. The overall risk of being a casualty in a fire has therefore decreased however the extent of the decline in fire-related fatalities and casualties differs and is explored in this section.

Historic data on the number of primary fires have been available since the year ending March 1982, and all fires since 19961.

Notes:

-

Primary fires are defined as potentially more serious fires that harm people or cause damage to property and meet at least one of the following conditions:

- any fire that occurred in a (non-derelict) building, vehicle or (some) outdoor structures

- any fire involving fatalities, casualties or rescues

- any fire attended by five or more pumping appliances

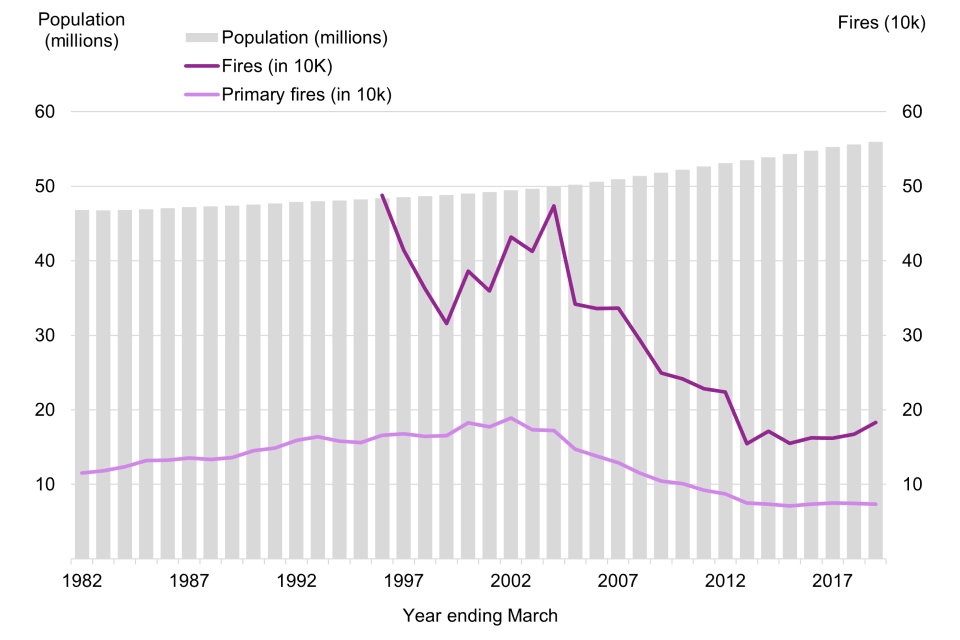

Since a peak of 189,068 primary fires in the year ending March 2002, these have declined by 61% to 73,267 in 2019. All fires have declined by 62% from 487,600 in the year ending March 1997 to 182,906 in the year ending March 2019. Figure 1 shows this trend in context of a rising population.

Figure 1: Trends in fires, England, years ending March 1982 to 2019

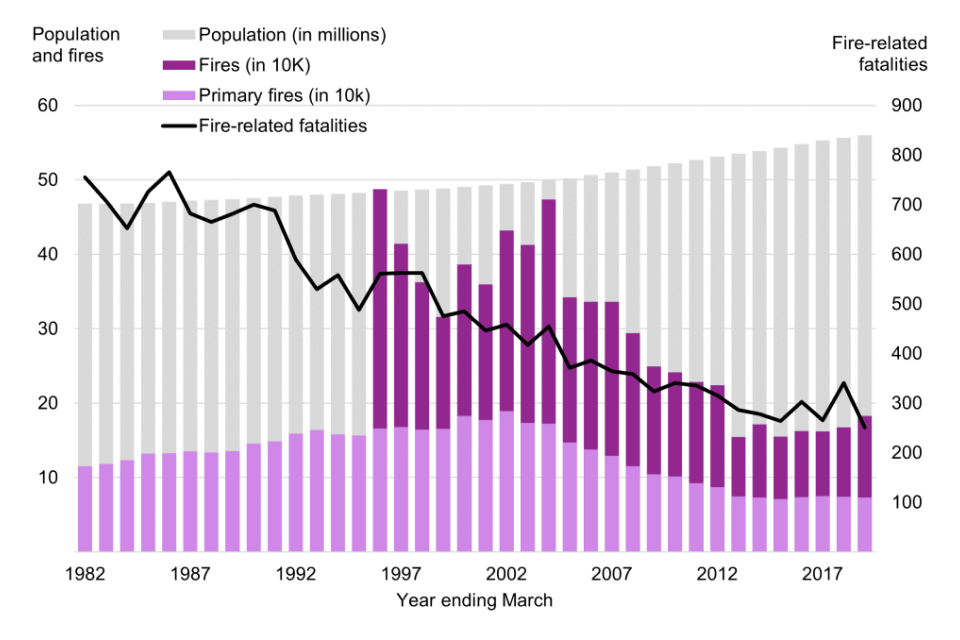

Since a peak of 765 fire-related fatalities in the year ending March 1986, fire-related fatalities have declined by 67% (Figure 2). Despite an increase in the population over time, the rate of fatalities per million population has fallen by 72%, from 16.1 to 4.5 per million population. This is a decline of 31% from 6.5 per million population in the year ending March 2011. The number of fatalities per 10,000 fires however fluctuated over the years with peaks of 20 fatalities per 10,000 fires in the year ending March 2018, and 19 per 10,000 fires in the year ending March 2016 and 2013, and lows of 10 per 10,000 fires in the years ending March 2003 and 2004. The overall risk of being involved in a fatal fire has decreased while the risk of a fire being fatal has increased.

Figure 2: Trends in fire-related fatalities, England, years ending March 1982 to 2019

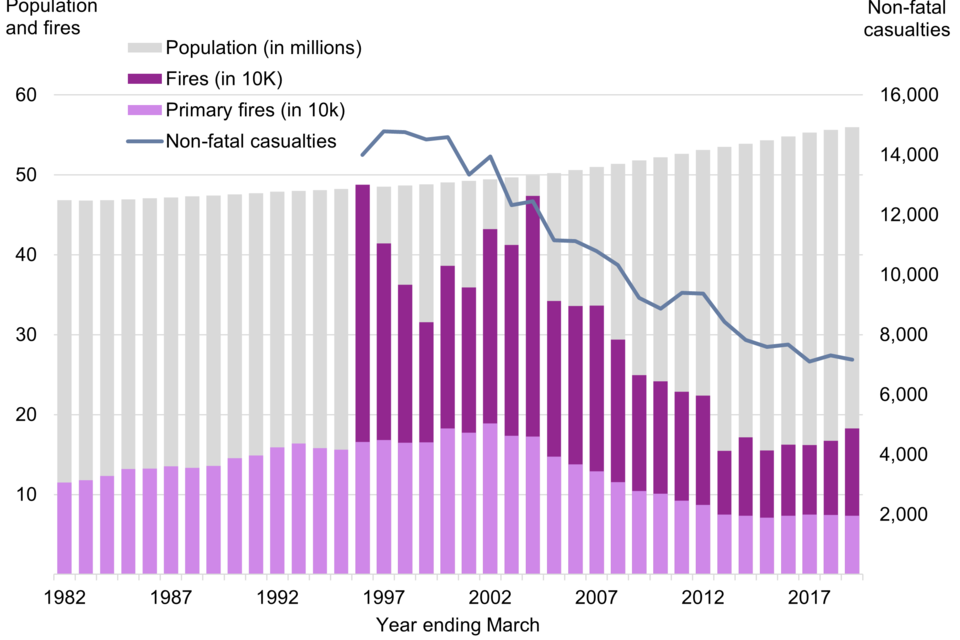

Non-fatal casualties have declined at half the rate of fatalities (Figure 3). Since the year ending March 1997, there has been a reduction in the number of non-fatal casualties by 52% and, given a 15% increase in the population during this time, the non-fatal casualty rate has declined by 58%. This is a decline of 28% since the year ending March 2011 from 179 per million population. The number of non-fatal casualties per 10,000 fires increased from a low of 287 in the year ending March 1996 to 546 in the year ending March 2013 which has since declined to 392 per 10,000 fires in the year ending March 2019. The overall risk of being involved in a casualty fire has therefore decreased.

Figure 3: Trends in non-fatal casualties, England, years ending March 1982 to 2019

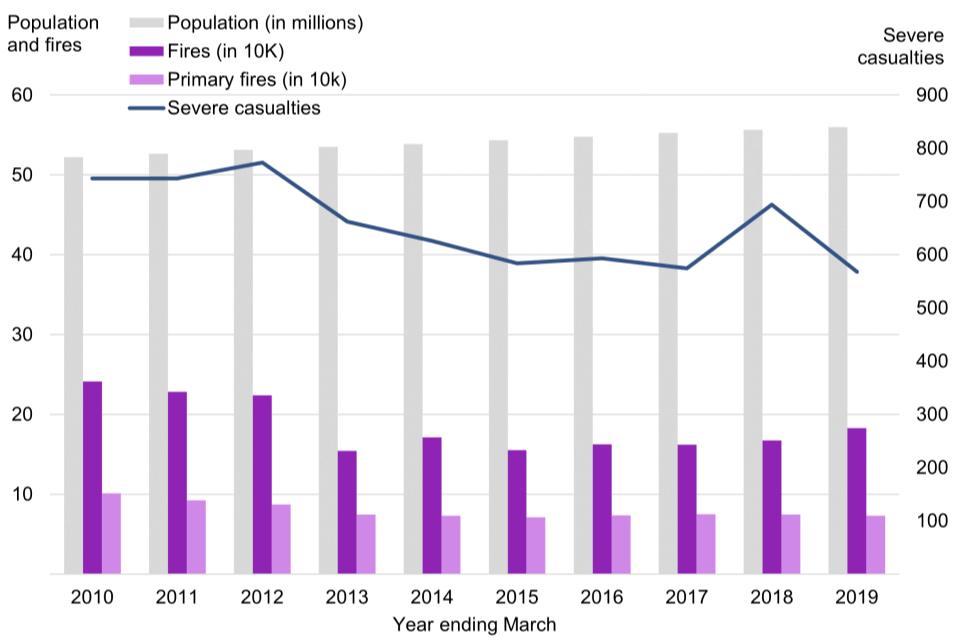

Since 2009, when the electronic IRS was introduced, non-fatal casualties have been categorised by injury severity. Since then, severe casualties, where the victim went to hospital and had at least an overnight stay in hospital as an in-patient, have also been on a downwards trend (Figure 4). There has been a 23% reduction of severe casualties from 743 in the year ending March 2011 to 568 in year ending March 2019 and the population has increased by 6%. The rate of severe casualties has decreased by 28% from 14.1 per million population to 10.1. The number of severe casualties per 10,000 fires was the same in the years ending March 2019 and 2010 at 31, however there have been peaks of 43 per 10,000 fires in the years ending March 2013, and 41 in 2018. The overall risk of being involved in a severe casualty fire has decreased but the risk of a fire involving a severe casualty has stayed the same.

Figure 4: Trends in severe casualties, England, years ending March 1982 to 2019

The decline in numbers of fatalities and severe casualties in the context of increasing population levels indicates means the overall risk of being involved in these fires has decreased. The difference in the trend when considering the reduced risk of a fire involving a fire-related fatality or severe casualties suggests there might be different factors affecting fatal and non-fatal fires.

4.1.1 Fires with multiple victims

In the year ending in March 2011 to 2019, there were:

- 2,356 fatal fires which involved 2,637 fatalities1

- 5,128 severe causality fires which involved 5,817 severe causalities

Notes:

- For the purpose of publications, figures included the number of fatal casualties which were either recorded as ‘fire-related’ or ‘don’t know’. Of the 2,637, 11% (283) were classified as don’t know as to whether these were fire-related.

Most fatal fires result in one fatality and, although not as rare as multiple fatality fires, fires which result in more than one severe casualty are uncommon (Table 2). Severe casualties and fatalities rarely occur together in the same fire. In the years ending March 2011 to 2019, 102 fires (1.3% of all fatal and severe casualty fires) resulted in at least one fatality and at least one severe casualty. Further exploration of fatal and severe casualty fires can determine if there are distinct victim or fire characteristics that influence the outcome of a fire.

Table 2: The number of fatalities and severe casualties resulting from fire, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019

| Number of fatalities | Number of fires with fatalities | % of all fatalities | Number of severe casualties | Number of fires with casualties | % of all severe casualties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,213 | 83.9% | 1 | 4,684 | 80.5% |

| 2 | 108 | 8.2 % | 2 | 336 | 11.6% |

| 3 | 17 | 1.9% | 3 | 67 | 3.5% |

| 4 | 8 | 1.2% | 4 | 19 | 1.3% |

| 5 | 5 | 0.9% | 5 | 13 | 1.1% |

| 6 | 3 | 0.7% | 6 | 5 | 0.5% |

| 11 | 1* | 0.4% | 7 | 2 | 0.2% |

| 71 | 1** | 2.7 | 8 | 1 | 0.1% |

| 67 ** | 1 | 1.2% |

Key:

-

*Shoreham Airshow Disaster

-

**Grenfell Tower Fire

There have been 2 major recent fires that have involved multiple casualties.

On 22 August 2015, a former military aircraft crashed during an air display at the Shoreham Airshow at Shoreham Airport, in West Sussex. During an aerobatic manoeuvre the aircraft crashed onto a main road and fuel escaping from the fuel tanks ignited in a large fire. There were 11 fatalities in this incident. The official inquiry into the fatalities has yet to be concluded and were therefore recorded as ‘don’t know if fire-related’ in the IRS.

On 14 June 2017, a fire broke out in the 24-storey Grenfell Tower block of flats in North Kensington, West London. From an initial refrigerator fire, the fire spread rapidly across the building. The fire claimed the lives of 71 people who were present in the tower that night. Another resident who had escaped from the building, seriously affected by smoke inhalation, died seven months later. A total of 227 people in all (residents and visitors) escaped from the tower and there were 67 severe casualties recorded. At the time of publication, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry had concluded hearings for Phase 2 and was preparing the final report.

4.2 Where do fatal and severe casualty fires occur?

This section explores whether certain areas of England have experienced higher rates of fatalities and casualties than others, and in which buildings or locations these fires occur.

Key findings

- fatal and severe casualty fires occurred more frequently in deprived areas

Location of fatal and severe casualty fires:

- fires involving a fatality or severe casualty most often occurred in indoor locations (1,952 fatal fires and 3,969 severe casualty fires) and specifically in residential buildings (1,844 fatal fires and 3,479 severe casualty fires)

- the most common room of origin for fatal dwelling fires was the living room (685 fires) whereas for severe casualties it was the kitchen (1,195 fires)

- fatal fires in other buildings (not classified as dwellings) occurred more frequently in residential properties (36 of 144 fires) such as a residential home, whereas severe casualties most frequently occurred in industrial premises (123 of 600 fires)

- road vehicle fires that involved a fire-related fatality or casualty were relatively infrequent (247 fatal fires and 573 severe casualty fires), and generally occurred in cars

- outdoor fires that involved a fatality or severe casualty were rare (157 fatal fires and 586 severe casualty fires) and generally occurred close to a building or structure

4.2.1 Local variation

Fire-related fatalities and severe casualties did not occur evenly across the country. The numbers of fatalities and severe casualties were highly correlated with the size and density of the population, meaning these fires occurred more frequently in the metropolitan areas (Population estimates by FRS can be found in Table FIRE1401 ).

In the years ending March 2011 to 2019, the total number of fatalities and severe casualties across FRSs varied from 0 fatalities and 1 severe casualty in the Isles of Scilly to 449 fatalities and 778 severe casualties in Greater London. The differing numbers of fatalities and severe casualties across the country were not necessarily linked to the actions of those FRSs and were possibly due to local characteristics of those areas.

4.2.1.1 Deprivation

The IMD combines data on seven domains of deprivation (income, employment, health deprivation and disability, education and skills training, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment) through a weighing system to produce a single ranking, organised into ten equally sized groups.

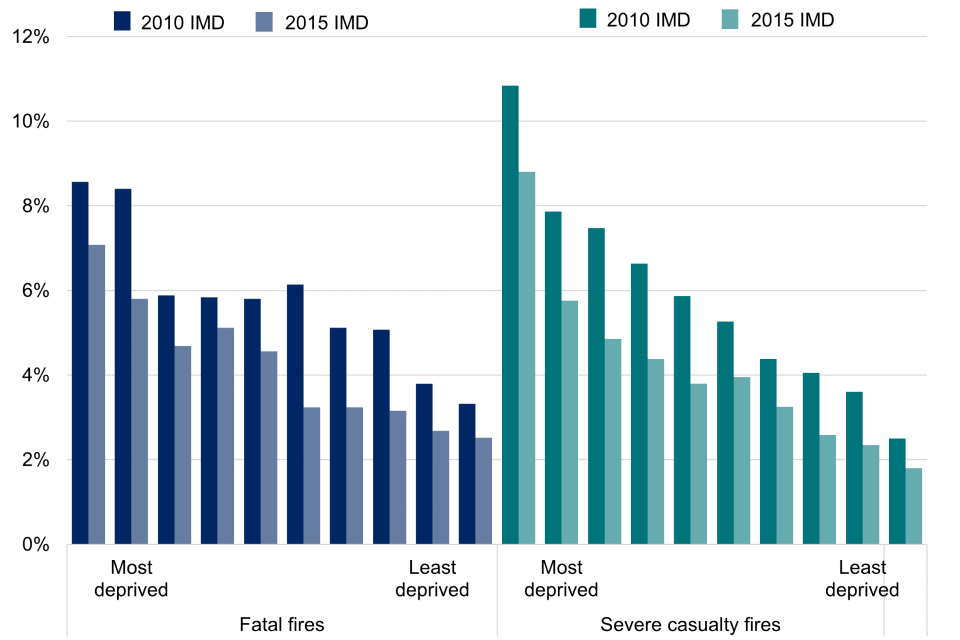

The number of fire fatalities and severe casualty fires were highly correlated with deprivation indices. The areas defined by the IMD as the most deprived half of England, accounted for 63% of fatal fires and 67% of severe casualty fires (full data shown in Appendix D). As the level of deprivation increased, the number of fire-related fatalities and casualties increased.

Considering both iterations of the IMD, 16% (334) of fatal fires and 21% (951) of severe casualty fires happened in the most deprived 10% of areas in England. This compares with 5% (106) of fatal fires and 4% (186) of severe casualty fires occurring in the least deprived 10% of areas in England. The relationship is shown in Figure 5. This has held true for both iterations of the IMD.

Figure 5: The proportion of fatal fires (left) and severe casualty fires (right) in each deprivation decile in England, combined data for years March 2011 to 2019

4.2.2 Location of fatal and severe casualty fires

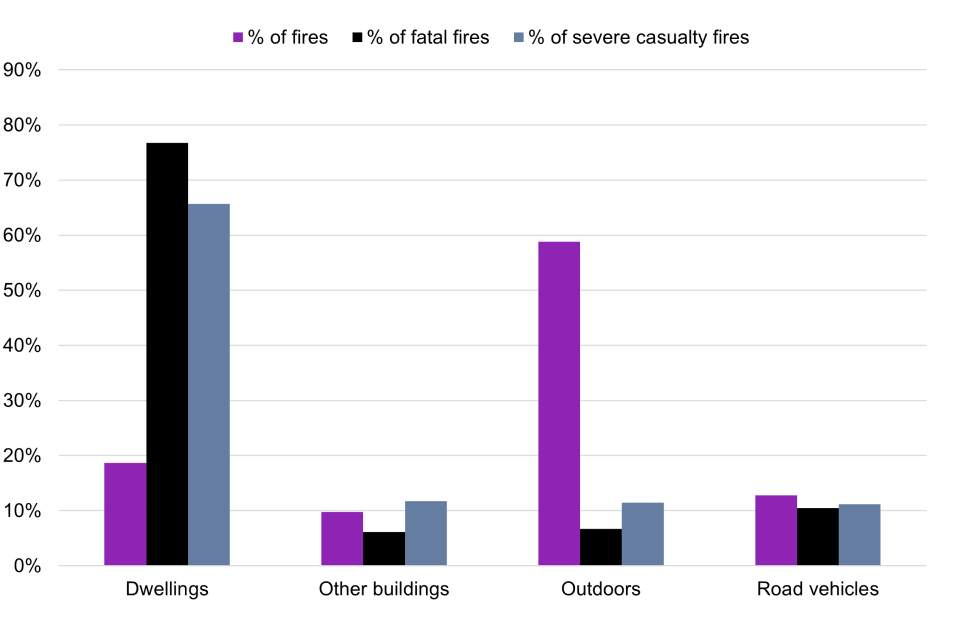

Despite a large proportion of fires since the year ending March 2011 occurring outdoors, relatively few of these resulted in a fatality or severe casualty (157 and 586 since that year). This was probably due to the likelihood of an individual being in proximity to the fire being lower in outdoor locations. As fire safety policy is generally defined by the building type or how it is used, for example requirements to install sprinklers, it is important to understand in which buildings, or locations, fatal and severe casualty fires occurred more frequently.

There are four major location categories within the fire data: dwellings, other buildings, road vehicles and outdoor. Dwellings are non-commercial residential properties such as houses and apartments. Other buildings are split between residential properties such as care homes, and non-residential properties such as office buildings. Analysis did not take into account composition of the total building stock and therefore the proportions of fires may reflect the proportions of each dwelling type generally. (Further information on this can be found in the detailed analysis of fires attended by fire and rescue services, England, April 2018 to March 2019).

After outdoor fires, the highest number of fires occur in dwellings. It is therefore not surprising that both fatal (77% or 1,808) and severe casualty (66% or 3,369) fires occurred most commonly in dwellings. Nearly equal proportions of severe casualty fires occurred in other buildings (12% or 600), and road vehicles (11% or 573). However, road vehicles accounted for larger proportions of fatal fires (10% or 247) compared with other buildings (6% or 144) and outdoor locations. It can be reasonably assumed that persons in a vehicle fire are more likely to be in proximity of the fire, with fewer means of escape, than in other buildings and outdoor fires.

Figure 6: Location of all fires, fatal fires, and severe casualty fires, years ending March 2011 to 2019

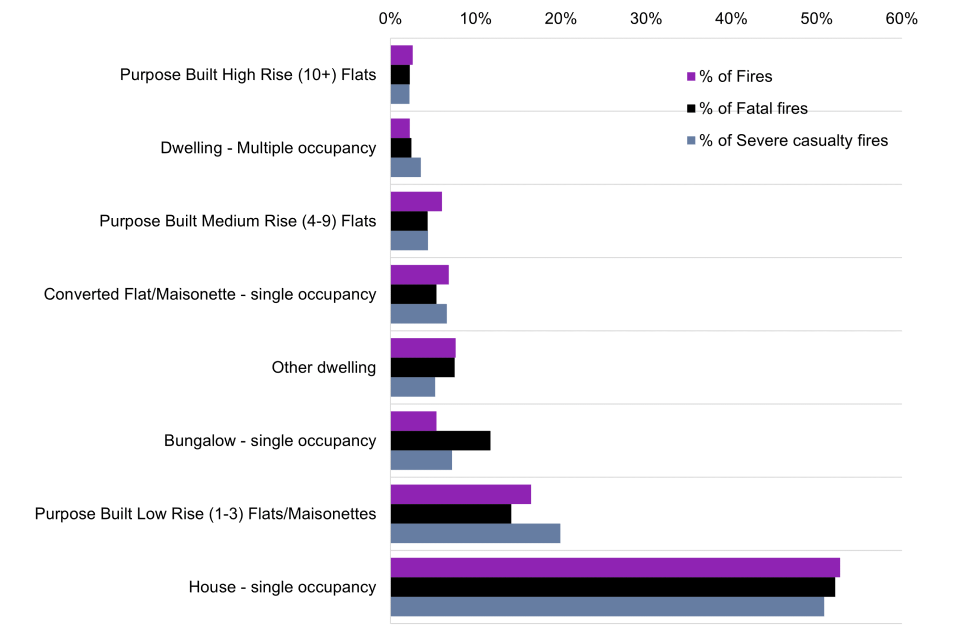

4.2.2.1 Dwelling fires

The proportion of fires which resulted in a severe casualty or fatality was similar across almost all dwelling types with the highest proportions for both in single occupancy houses. This indicates that the dwelling type did not greatly impact on the outcome of a fire. However, this did not hold for bungalows, where there were a higher proportion of fatal fires than severe casualty fires. It could be there was a characteristic of the victims more likely to live in these properties which made the fires more likely to be fatal.

Fatal and severe casualty fires were proportionally least common in purpose-built high-rise (10 or more storeys) flats, representing 2% of both fatal fires and severe casualty fires (41 and 75). However, the lowest proportion of fatal and severe casualty fires were in houses of multiple occupancy (2% and 4% respectively). It should be noted that while the number of fires in purpose-built high-rise flats was low, this category includes the Grenfell Tower fire.

Figure 7: All fires and fatal and severe casualty fires in dwelling type, years ending March 2011 to 2019

In all dwelling types, the fire start location for the majority of both severe casualty fires (1,552, 46%) and fatal fires (1,248, 69%) was either the living room, bedroom or bedsitting room. The living room was the most common starting location for fatal dwelling fires (685, 38%), whereas severe casualty fires most frequently began in the kitchen (1,195, 35%). This suggests that the room in which the fire started was likely to be a factor in the outcome. The cause of fire was recorded as deliberate in 267 fatal dwelling fires (15%) and 684 severe casualties (20%).

4.2.2.2 Other building fires

Other building fires are fires that occurred in a non-derelict building that was not a dwelling. This includes both residential buildings such as care homes and hotels, and non-residential buildings such as offices. Other buildings were generally covered by the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005, meaning they were subject to more regular scrutiny in terms of fire safety. These regulations are intended to reduce the likelihood of unsafe environments that could lead to fires and, when fires do occur, appropriate systems should be in place to safely evacuate the building and suppress the fires.

There were 144 fatal fires (6% of all fatal fires) and 600 severe casualty fires (12% of all severe casualty fires) in other buildings in the years ending March 2011 to 2019. The majority of fatal other building fires occurred in residential homes, or private non-residential properties such as sheds and summer houses, whereas severe casualties most frequently occurred in industrial premises. The low proportion of fatal and severe casualty fires in non-residential buildings, was likely due to people within these buildings being more alert to fire.

Similar to dwellings, fatal and severe casualty fires in residential other building fires were most likely to start in the bedroom or bedsitting room (61% (22) fatal and 50% (55) severe casualty). In non-residential properties, fatal or severe casualty fires were mostly likely to start in an ‘other’ location (31% and 40% respectively) followed by the garage (17% and 14%). The cause of fire was recorded as deliberate in 49 fatal other building fires (34%) and 165 severe casualties (28%).

There were more locations in which the fire started for severe casualty fires than fatal fires. This reflects the greater diversity in the type of buildings where severe casualty fires occurred and suggests there is more variability in severe casualty fires that will need to be considered when targeting fire safety interventions.

4.2.2.3 Road vehicle fires

There were 247 fatal fires (10% of all fatal fires) and 573 severe casualty fires (11% of all severe casualty fires) in road vehicles in the years ending March 2011 to 2019. The majority of fatal fires occurred in cars (200, 81%), with very few in other vehicle types such as lorries or motorcycles. While the majority of severe casualties also occurred in cars (353, 62%), higher proportions occurred in incidents with multiple vehicles (64, 11%). The cause of fire was considered to deliberate for 113 fatal road vehicle fires (46%) and 51 severe casualty road vehicle fires (9%).

The complexity of these fires, a scenario whereby the victim could not escape, may increase the difficulty of assigning cause to injuries. For this reason, it was not always confirmed that severe casualties in road vehicle fires were fire-related. The cause of fire for 85 fatal fires in road vehicles (34%) and 352 severe casualty fires in road vehicles (61%) was listed as ‘vehicle crash’ or ‘collision’.

The most frequent starting point of fatal road vehicle fires was in the driver or passenger area (50%), whereas severe casualty fires most commonly started in the engine (51%). The difference in outcome was likely affected by the victim’s proximity to the fire and therefore ability to escape.

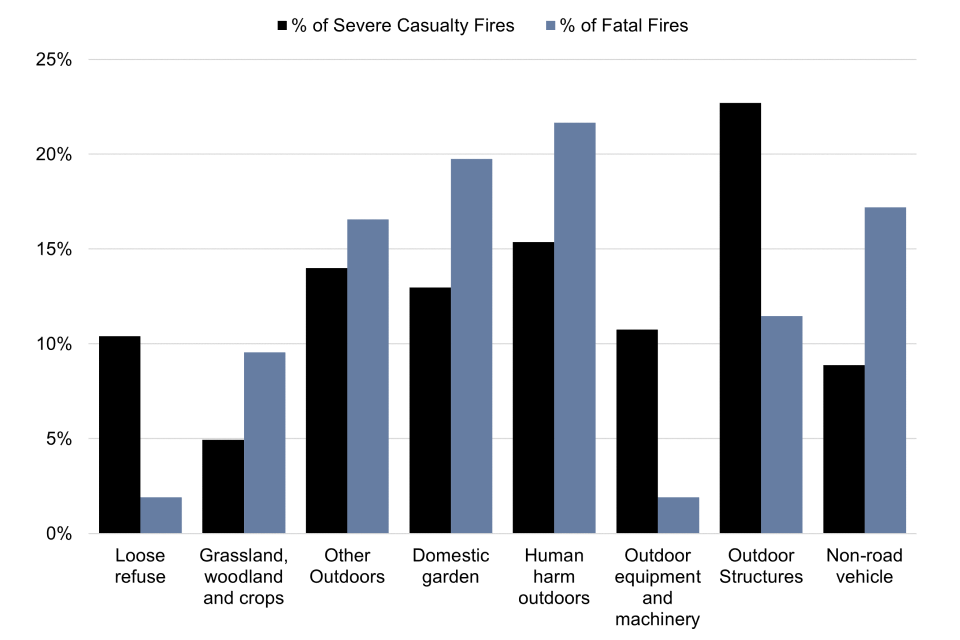

4.2.2.4 Outdoor fires

There were relatively few fatal fires (157 or 7% of all fatal fires) and severe casualty fires (586 or 11% of all severe casualty fires) that occurred as a result of an outdoor fire. These generally occurred where people were expected to be present, for example in a domestic garden. Furthermore, the fire start location in outdoor fires was often near housing (41 fatal outdoor fires and 197 severe casualty outdoor fires). A large proportion of the fatal fires outdoors (82 or 52%) were deliberate and 140 severe casualty outdoor fires (24%) were deliberate.

Figure 8: All outdoor fires and fatal and severe casualty fires by location, years ending March 2011 to 2019

Notes:

- Human harm outdoors is defined as fire where the focus of the fire was the individual involved, for example self-immolation.

4.3 When do fatal and severe casualty fires occur?

Fires generally occurred more during the evening (between 16:00 and 22:00) and, in the case of outdoor fires, were more frequent during the summer months (Home Office, 2019). It is important to understand if these patterns held for fatal and severe casualty fires as this can influence decisions around firefighter shift patterns, and at what times during the year it would be appropriate to run education initiatives on fire safety. The time of day may also link to periods of common behaviour, for example peak time cooking.

Key findings

- fatal fires more often occurred during winter months (711, 30%), with little variation based on the day of the week or time of day

- severe casualty fires occurred evenly throughout the year but more often occurred in the afternoon/evening

4.3.1 Seasonal differences

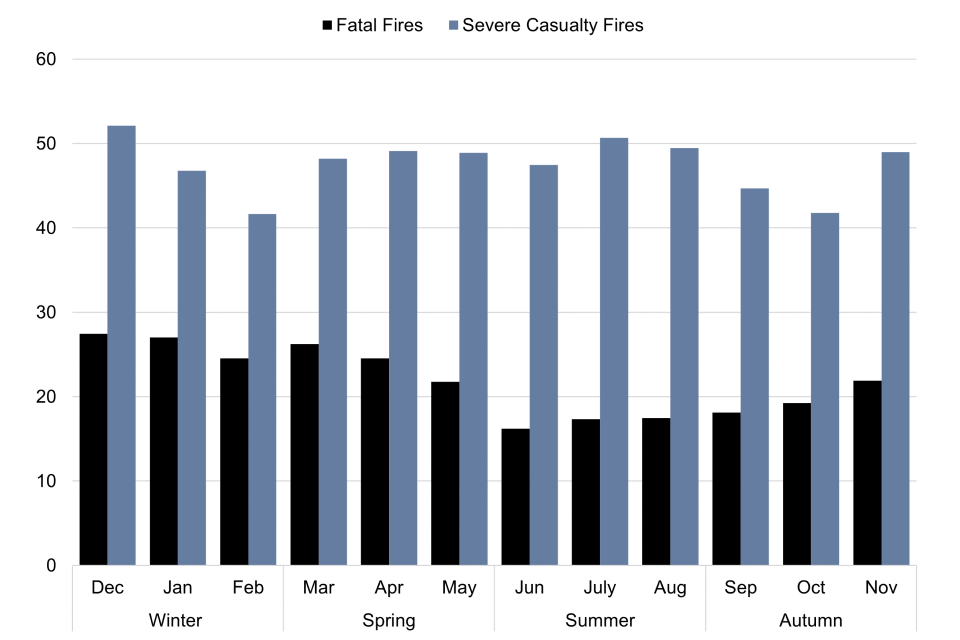

Fatal fires were not spread evenly throughout the year with more occurring in winter and spring months than summer months. While there was some monthly variation in severe casualties, they were more evenly spread throughout the year and less linked to seasons (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Average number of fatal and severe casualty fires per month, years ending March 2011 to 2019

Three in ten (30%) fatal fires occurred in the winter months of December, January and February, an average of 69 per year. This compares with 19% of fatal fires which occurred during summer (June, July and August), an average of 51 per year. This trend could be associated with people being inside more during the winter months and additional use of heating equipment.

The proportion of dwelling fires that involved a fatality was higher in winter (32% of all fatal fires or 581) than any other season, whereas in other building and outdoors fires there was a higher proportion of fatal fires in spring. Road vehicle fires had similar proportions of fatal fires throughout the year. These seasonal patterns generally held true for severe casualty fires; however, the highest proportions of other building and outdoor fires involving severe casualties were in the summer. This potentially links with more people spending time outdoors or at outdoor event spaces.

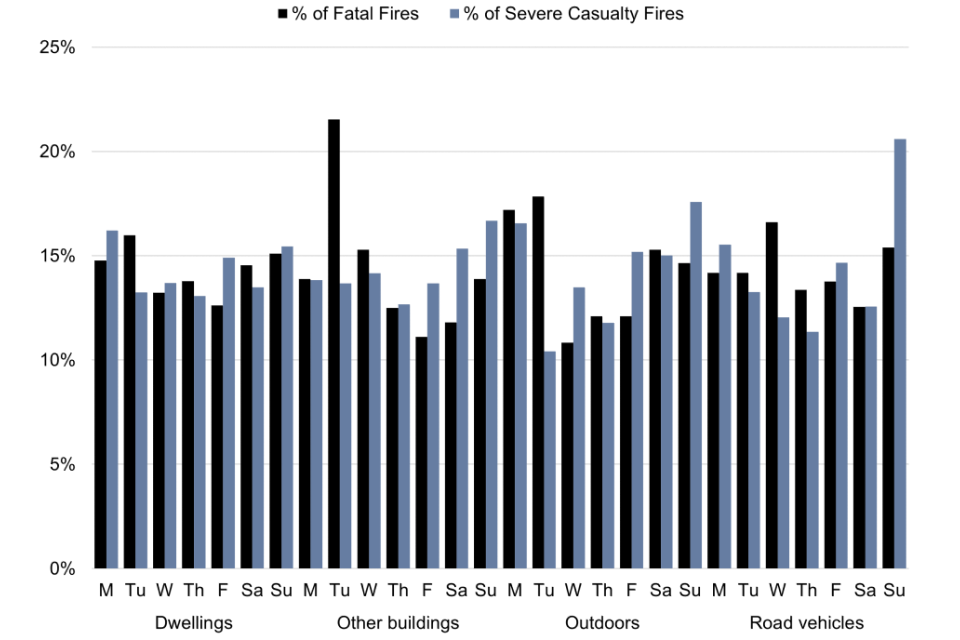

4.3.2 Day of the week

Overall, fatal and severe casualty fires occurred equally throughout the week. This was often true when considering each fire location, although a higher proportion of non-dwelling fatal fires occurred on Tuesdays than any other day of the week. It is not clear why this would be the case. Additionally, road vehicle fires involving severe casualties occurred most regularly on Sundays.

Figure 10: proportion of fatal and severe casualty fires each day by location, years ending March 2011 to 2019

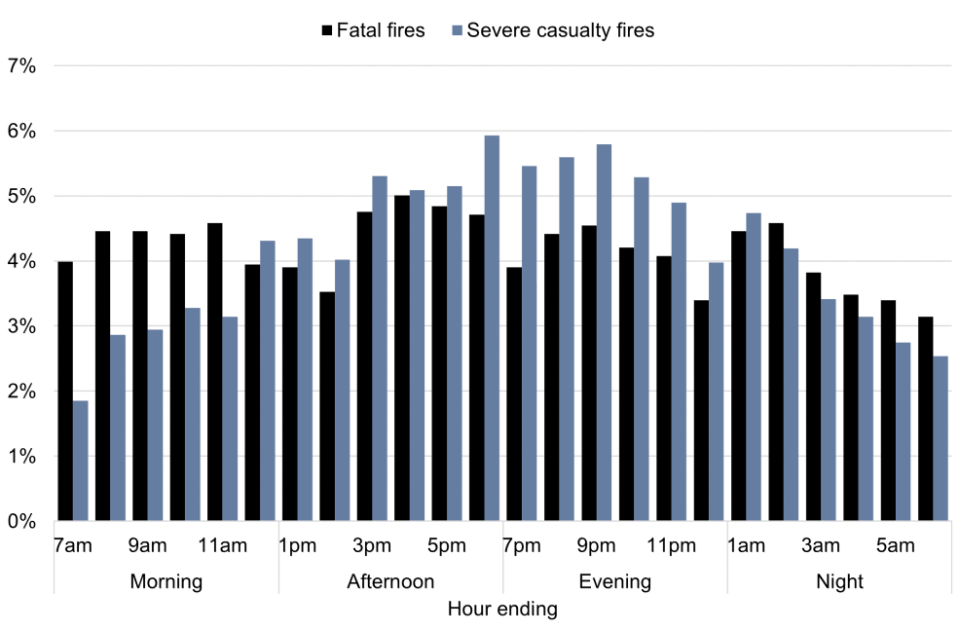

4.3.3 Time of day

Fatal fires did not vary substantially depending on the time of day. However, a higher proportion of severe casualty fires occurred between 2pm and 11pm, and the fewest of these fires occurred during times people typically sleep.

Figure 11: The proportion of fatal severe casualty fires by time of day, years ending March 2011 to 2019

Overall, the number of severe casualty fires was lowest between 6am and 7am (95, 2%), but increased gradually through the day, with a peak of 304 (6%) occurring between 5pm and 6pm. The frequency of severe casualties then stayed fairly stable before declining gradually between 10pm and 6am.

The afternoon and evening accounted for more severe casualty fires. Over half (3,120, 61%) of severe casualty fires occurred in the afternoon and evening. Fewer severe casualty fires occurred during the early morning hours, particularly between 2am and 11am, where 26% (1,329) of fires occurred. This pattern exists across fire locations.

It is likely that fewer severe casualties occurred at night and in the morning due to sleeping patterns and lower levels of activities which increase the risk of a severe fire injury, such as cooking or smoking. This is particularly evident by a high proportion of severe casualty fires taking place at what could be considered ‘dinner time’ between 5pm and 9pm. As there was no trend in the time of day fatal fires occurred, it suggests that there are not the same links to activities such as cooking, as there are with severe casualties.

4.4 What types of fire result in fatalities and severe casualties?

The IRS collects data on how fires start, the presence of a working smoke alarm and some limited information on whether drug and/or alcohol use is believed to have contributed to the fire. This, together with data on the behaviour of the fire itself, such as the spread of fire, provides a useful indication of the types of fire which result in a fatal or severe casualty.

Key findings

- while there was a higher risk of severe casualty than fatality in all fires, the risk of fatality in a smokers’ materials fire and the risk of severe casualty were almost equal (18.3 and 18.4 per 1,000 fires)

- the item first ignited for both severe casualty and fatal fires in buildings was most often textiles, upholstery and furnishings (1,127 fatal fires and 1,792 severe casualty fires)

- fatal and severe casualty fires rarely spread beyond the room of origin or item first ignited

- there was a working smoke alarm present in a large proportion of fatal (925 or 50%) and severe casualty (1,986 or 57%) fires that occurred in dwellings or other residential properties, and the lack of a working smoke alarm increased the likelihood of a fatal or severe casualty fire

4.4.1 Source of ignition and item first ignited

For a fire to start, a source of ignition and something to be ignited are needed. Some sources of ignition are intended to flame, for example cigarette lighters, whereas others generally cause fires due to a fault, for example electrical distribution. In both cases the item first ignited is instrumental in the fire spreading.

Determining the cause of fire can be difficult depending on the extent of fire damage and so the source of ignition was unspecified in a large proportion of cases (776 fatal fires (33%) and 1,799 severe casualty fires (35%)). Where it was specified, smoking materials (including discarded cigarettes) were the source of ignition in 25% (590) of fatal fires and 12% (593) of severe casualty fires, despite only accounting for 2% (32,226) of all fires in the same period. It should be noted that while there is a higher risk of severe casualty than fatality in all fires, the risk of fatality in a smoking-related fire and the risk of severe casualty in a smoking materials fire were almost equal at 18.3 fatal fires per 1,000 smoking material fires and 18.4 severe casualty fires. Although smoking material fires had a high severe casualty rate, candle fires had the highest severe casualty fires rate overall (21.8 per 1,000 fires) (Table 3).

Although cooking appliances had a lower severe casualty rate of 7 per 1,000 fires, this was the source of ignition for the largest volume of severe casualty fires where specified, accounting for over 1 in 5 (22%, 1,117) severe casualty fires which resulted in 1,204 severe casualties.

Table 3: Number and rate of fatal and severe casualty fires per 1,000 fires by source of ignition, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019

| Source of ignition | Fatal fires | Severe casualty fires | Fires | Rate of fatal fires | Rate of severe casualty fires |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blowlamps, welding and cutting equipment | 8 | 69 | 5,577 | 1.4 | 12.4 |

| Candles | 94 | 204 | 9,371 | 10 | 21.8 |

| Central and water heating appliances | 5 | 10 | 3,963 | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| Cigarette lighters | 199 | 410 | 22,164 | 9 | 18.5 |

| Cooking appliances | 180 | 1,117 | 150,639 | 1.2 | 7.4 |

| Electrical distribution | 80 | 267 | 71,072 | 1.1 | 3.8 |

| Matches | 143 | 229 | 34,907 | 4.1 | 6.6 |

| Other / Unspecified | 776 | 1,799 | 1,208,993 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| Other electrical appliances | 106 | 205 | 53,906 | 2 | 3.8 |

| Smokers’ materials | 590 | 593 | 32,226 | 18.3 | 18.4 |

| Space heating appliances | 175 | 225 | 14,850 | 11.8 | 15.2 |

Notes:

- It should be noted that source of ignition was not collected in secondary fires (those that do not involve people or property and require less than four pumps in attendance). These accounted for 865,734 fires in the years ending March 2011 to 2019. Without these the other/unspecified rate of fatal and severe casualty fires would be 2.3 and 5.2 respectively.

When looking at total fatal fires, 17% (405) were recorded as being associated with alcohol and/or drugs. However, fatal fires where the source of ignition was from smokers’ materials were more often associated with alcohol or drug use (44%, 179) than any other ignition type. Meanwhile, in severe casualty fires the most likely source of ignition where the individual used alcohol or drugs was in cooking fires (29%, 282).

Table 4: Proportion of fatal and severe casualty fires where individuals were suspected to be under the influence, by source of ignition, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019

| Source of ignition | % of fatal fires suspected under the influence | % of severe casualty fires suspected under the influence |

|---|---|---|

| Blowlamps, welding and cutting equipment | - | 0.1% |

| Candles | 5.7% | 5.6% |

| Cigarette lighters | 6.2% | 7.8% |

| Cooking appliances | 10.4% | 28.9% |

| Electrical distribution | 2.2% | 1.3% |

| Matches | 3.2% | 3.5% |

| Other / Unspecified | 20.2% | 25.0% |

| Other electrical appliances | 1.7% | 1.3% |

| Smokers’ materials | 44.2% | 23.4% |

| Space heating appliances | 6.2% | 3.0% |

| All sources of ignition | 17.2% | 19.0% |

For three-quarters of the fatal fires where smoking materials were the source of ignition (75%, 441 of 590), the item first ignited was textiles, upholstery and furnishings, and for nearly one-third (30%, 131 of 441), upholstered furniture was the item recorded as responsible for the spread of fire, followed by bed/mattresses (23%, 100). These figures indicate that victims of these fires were likely in close proximity to the fire, particularly if they were in bed, or sitting on furnishings.

There were 123 fatal fires ignited by cigarette lighters recorded as being caused deliberately and 259 severe casualty fires.

More than half of severe casualty candle fires (53%, 108) were caused by placing articles too close to heat, and for 73% (148), the item first ignited was textiles, upholstery and furnishings. Injuries occurring from this type of fire could be associated with victims’ clothes catching on fire, therefore explaining the high rate of injury.

When considering the location of the fire, the item first ignited for both severe casualty and fatal fires in buildings was most often textiles, upholstery and furnishings (2,585, 44% of all fatal and severe casualty building fires). In outdoor and road vehicle fires that involve a fatality or casualty, the item first ignited was most often explosives, gases or chemicals (536, 35% of these fires).

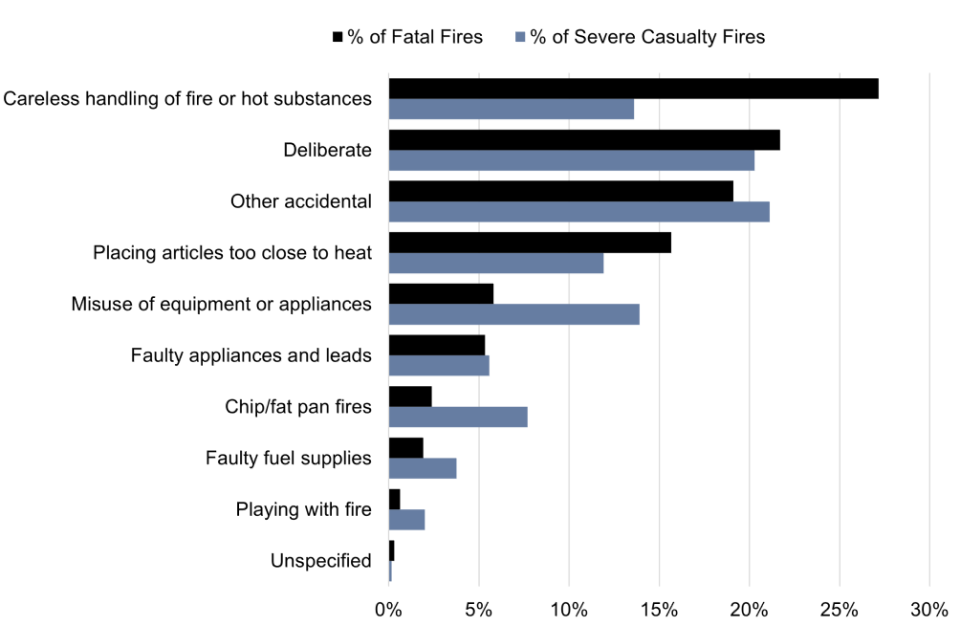

4.4.2 Cause of fire

The most common cause of fatal fires was careless handling of fire or hot substances (640, 27%), whereas the most common causes of severe casualty fires where known were considered to be deliberate (1,040, 20%) or misuse of equipment or appliances (713, 14%). There were 511 (22%) fatal fires in which the cause was considered to be deliberate. Of these, 295 were specifically recorded suicide or homicide attempts. For the remaining 216, it is not always clear in the recording of these cases if the fire was intentionally set to harm people or property, or if this was an intentional use of fire that grew out of control.

Figure 12: Proportion of fatal and severe casualty fires by cause of fire, years ending March 2011 and 2019

Of the fires where the cause is listed as other accidental, 99 fatal fires and 63 severe casualty fires were caused by vehicle crash or collision. For all other cases, the causes were intentional burning going out of control (such as a bonfire), accumulation of flammable materials, or the cause of fire was unclear at the time of recording.

4.4.3 Spread of fire

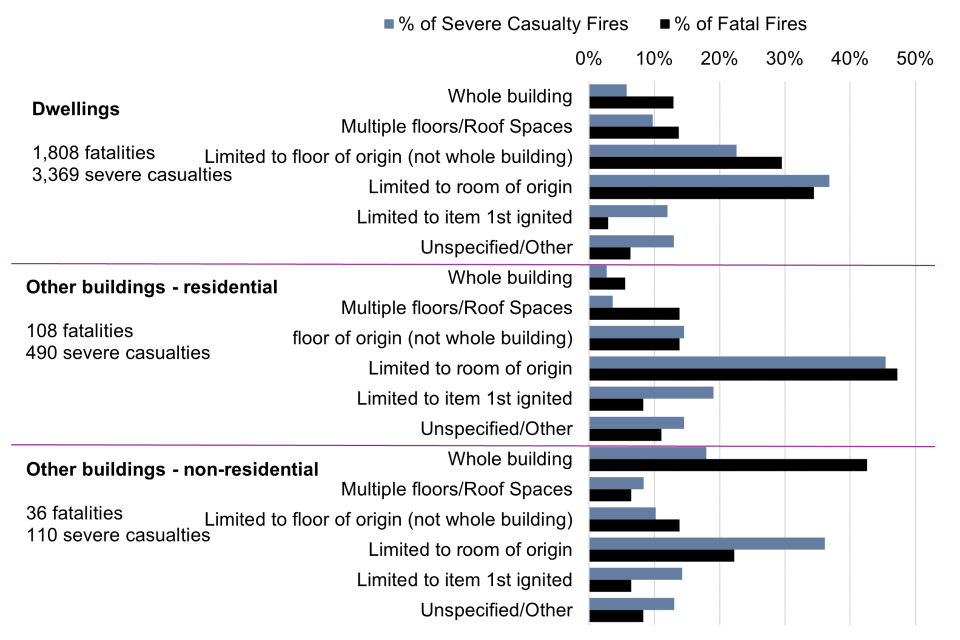

It was not the case that larger fires were responsible for more fatalities and severe casualties. In many fatal and severe casualty dwelling fires, the spread was limited to the room of origin (Figure 13). This was similar for other buildings. However, a high proportion, albeit a small number, of severe casualty fires in non-residential buildings were the result of a fire that spread throughout the whole building (43%, 88 fires) and, of these 88 fires, 35 were in smaller buildings such as private sheds or garages. Road vehicle fires typically involved the whole vehicle.

Figure 13: Proportion of fatal and severe casualty fires within each location type by extent of fire spread, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019

In addition to the fire spread, where the fire affected a part of the building covered by the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005, firefighters could record if compartmentation had been breached. Where this was recorded, compartmentation generally stopped/checked the spread of fire.

Table 5: Compartmentation in fatal and severe casualty fires in dwellings and other buildings, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019

| Compartmentation | Fatal fires | Severe casualty fires |

|---|---|---|

| Breached – current building work | 7 | 9 |

| Breached – fire doors left open or incorrectly fitted | 14 | 26 |

| Breached – previous building work | 2 | 6 |

| Damage to compartmentation | 10 | 27 |

| Fire spread through gaps or voids in construction | 16 | 35 |

| No compartmentation in building | 21 | 78 |

| Other | 21 | 34 |

| Stopped/Checked spread | 148 | 485 |

| Not applicable | 2,117 | 4,428 |

4.4.4 Smoke detection

Based on the EHS for year ending March 2019, an estimated 90% of dwellings in England had a working smoke alarm. The presence of a smoke alarm does not prevent fires; however, it can alert people to the existence of a fire so they react appropriately, meaning this should reduce the number of fires that require the FRSs, and the chance of a fatality or severe casualty.

In 50% of fatal dwelling fires (895 of 1,808) and 56% of severe casualty dwelling fires (1,885 of 3,369), there was at least one working smoke alarm present. This compares with 83% of fatal fires in other residential buildings (30 of 36) and 92% of severe casualty other residential building fires (101 of 110). The difference is likely due to the regulations around other residential buildings that required a smoke detection system that was regularly tested.

It should be noted that there were fatalities and severe causalities where at least one smoke alarm was present and activated. The outcome of these fires could have been due to a number of reasons such as the person did not hear the alarm or was not able to respond. This means that further fire safety systems or interventions may need to be considered for some individuals.

Comparing the proportion of fires with or without smoke alarms with the proportion of households with or without smoke alarms, it is possible to calculate the risk of a fire based on the presence of a working smoke alarm.

Table 6: Proportion of dwellings, dwelling fires, and fatal dwelling fires by smoke alarm status, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019

| Smoke alarm present and working | Smoke alarm present but defective | No working smoke alarm | Smoke alarm absent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dwellings* | 88% | 12% | ||

| Dwelling fires | 62% | 8% | 30% | |

| Severe casualty dwelling fires | 56% | 15% | 29% | |

| Fatal dwelling fires | 50% | 16% | 34% |

Key:

- *Average smoke alarm data for all years from the EHS, year ending March 2019.

Households with no working smoke alarm are:

- more than 4.7 times more likely to be involved in a fire that requires FRS assistance

- more than 6.0 times more likely to be involved in a severe casualty fire

- more than 7.8 times more likely to be involved in a fatal fire

4.5 What is the profile of fatal and severe casualty victims of fire?

It is well documented that most fatal victims tend to be older, and men have a greater likelihood of dying in a fire than women (Home Office, 2019). Using relative risk analysis, this section explores whether the same holds true for severe casualties and, if compared with the general population, by how much the risk of being involved in a fatal and severe casualty fire increases. Relative risk is given alongside confidence intervals (CI). In addition, this section explores the recorded information on household type at the time of the fire, and victim ethnicity.

Key findings

- the risk of being a fatal fire victim increases with age

- the risk of being a severe casualty is more variable and those between 17 and 54 years have a higher risk than those aged between 54 and 65 years

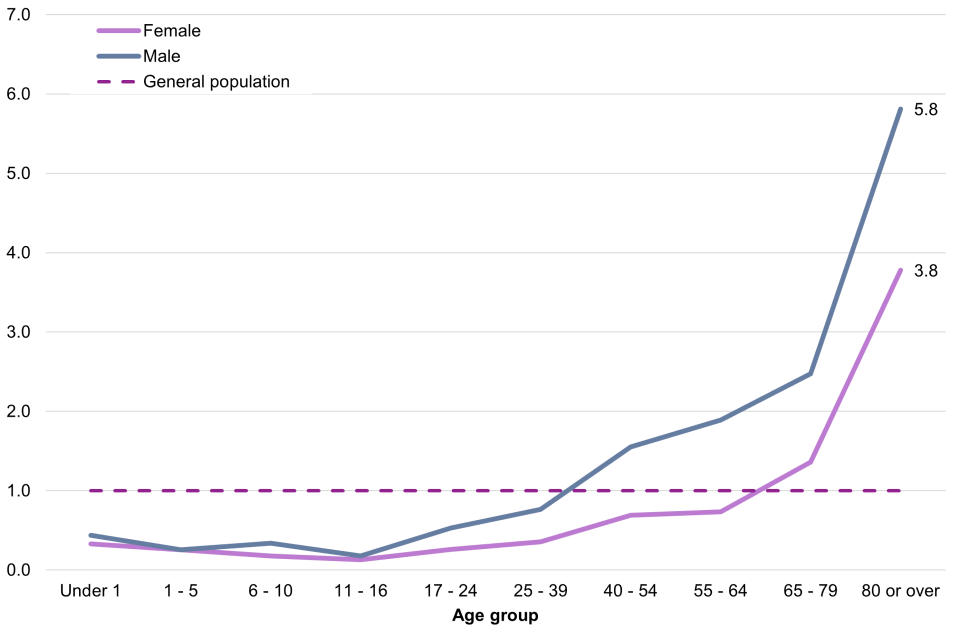

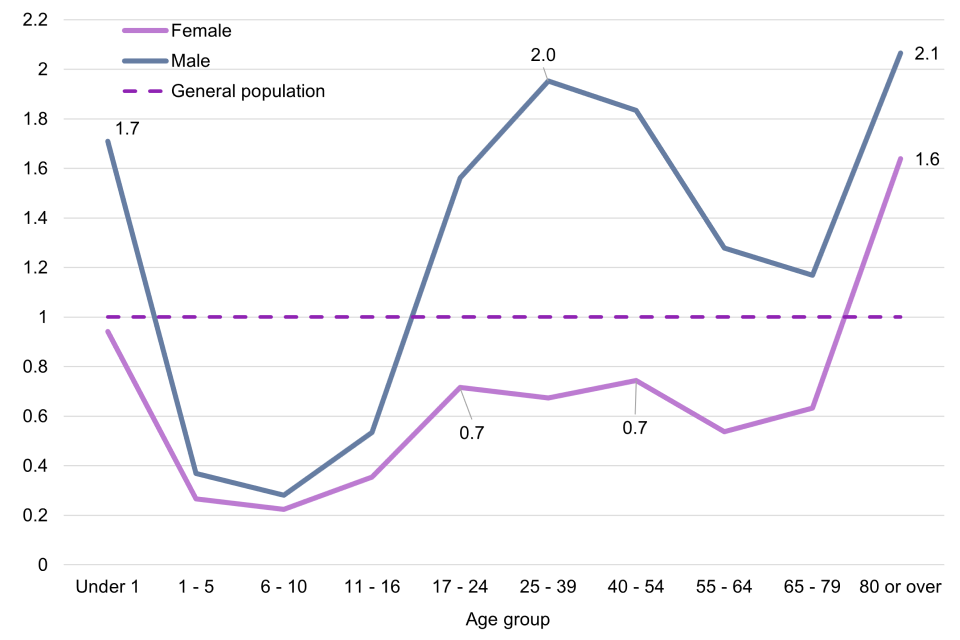

- the risk of being involved in a fatal or severe casualty fire is higher for males than females

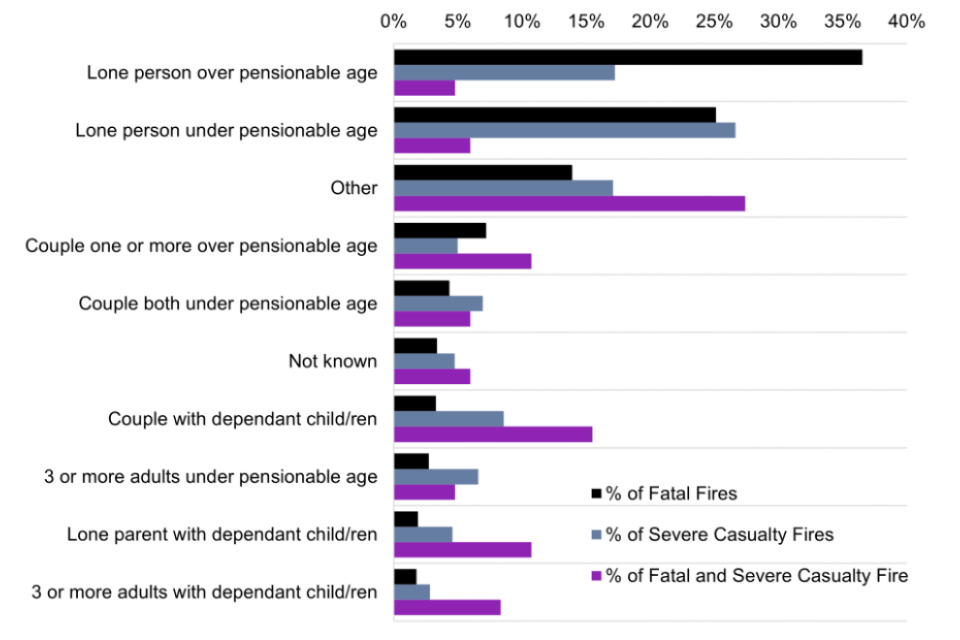

- the highest proportion of fatal fires were in households where a single person over pensionable age was present (660 of 2,356 fires)

- males are two times more likely than females to be a fatal fire victim in a deliberate fire at any age

4.5.1 Age

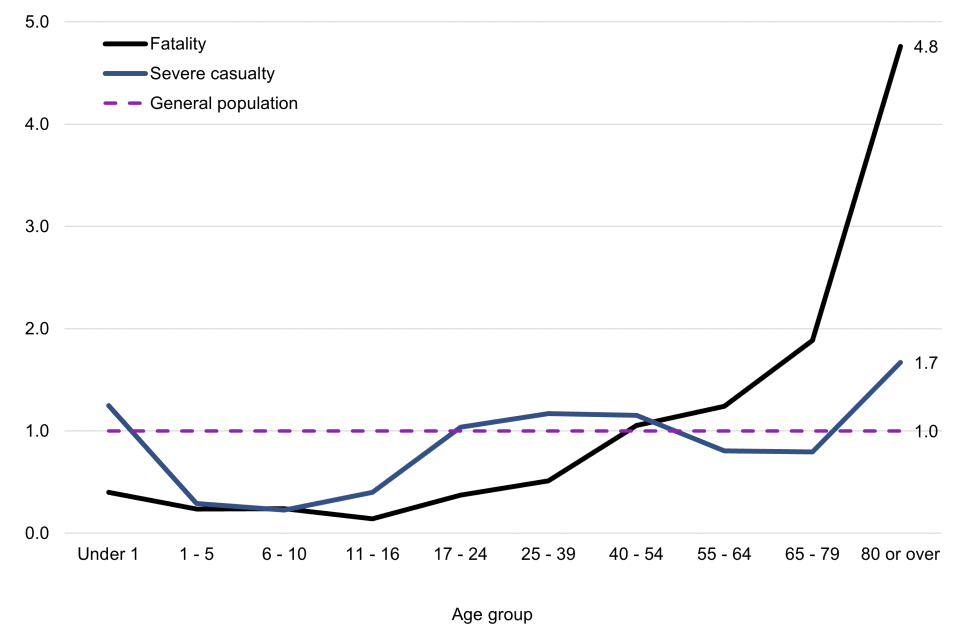

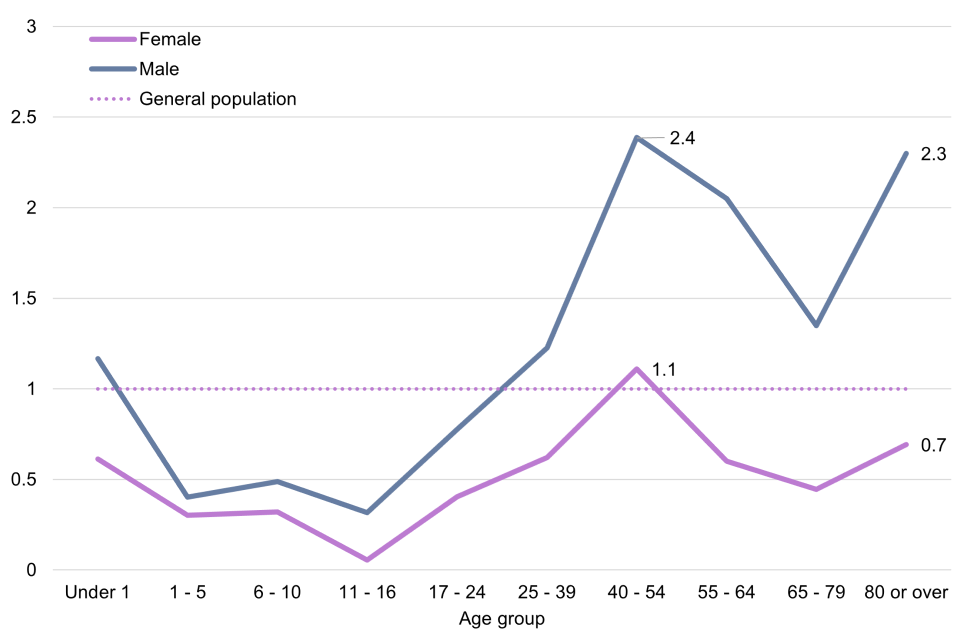

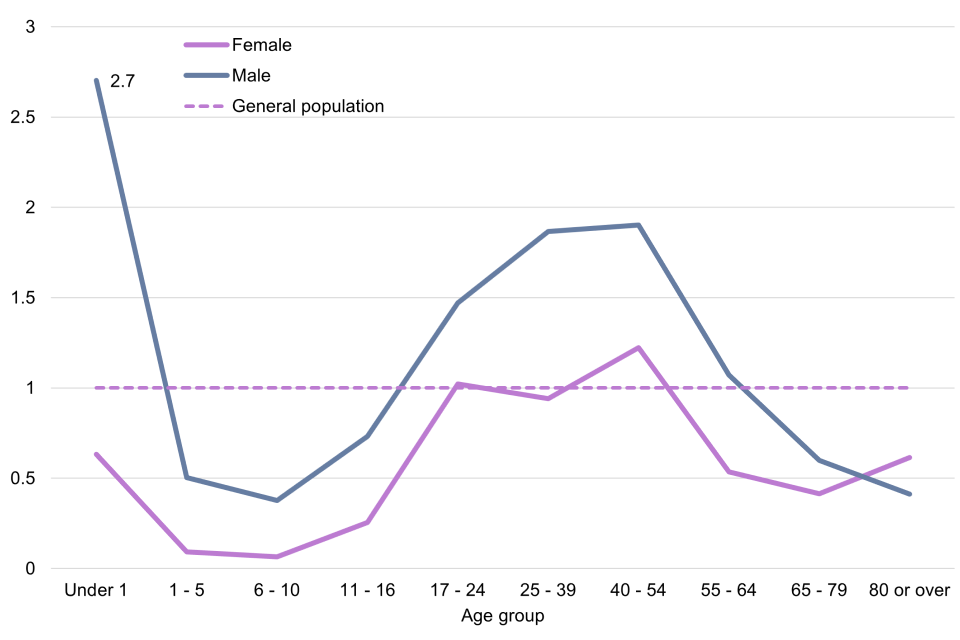

Figure 14 shows the relative risk (RR) of fatality and severe casualty by age group compared to the general population. This analysis clearly outlines the increased risk of fire-related fatality with age. Those aged 80 or older were four times more likely to die in a fire than the average for the general population. The gradual increase in risk began from ages 11 to 16 (RR = 0.1, 95% CI -0.2 to 0.5) with all those over 40 having an above average risk of dying in a fire (RR aged 40 and 54 = 1.1, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.1; RR aged 80 or over = 4.8, 95% CI 4.7 to 4.9).

Figure 14: RR of fire fatality and severe casualty by age group, combined data for years ending March 2011 to 2019