Technical consultation on the Infrastructure Levy

Published 17 March 2023

Applies to England

Topic of this consultation

This consultation seeks views on technical aspects of the design of the Infrastructure Levy. Responses will inform the preparation and content of regulations, which will themselves be consulted on, should Parliament grant the necessary powers set out in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill.

The Bill also introduces the power for the government to pilot Community Land Auctions (CLAs) to explore another avenue to more efficiently capture land value. While CLAs are not subject to this technical consultation, local authorities interested in finding out more should contact the Department for Levelling Up Housing and Communities (DLUHC) Infrastructure Levy team at InfrastructureLevyConsultation@levellingup.gov.uk.

DLUHC’s Infrastructure Levy team welcomes the opportunity to engage with a range of stakeholders from across the development and affordable housing sector, as well as with representative organisations and local government.

Geographical scope

These proposals will apply to England only.

Impact assessment

The government is required under section 149 of the Equality Act 2010 (“the Public Sector Equality Duty”) to have regard to the actual or potential impact/s (if any) of any new policy proposals on ‘equality’. This means in summary, addressing three needs: eliminating discrimination, promoting equality of opportunity and fostering good relations between different groups. This applies in relation to protected characteristics; sex, race, disability, age, etc. We will refer to this broadly as the ‘equality’ impacts. In each part of the consultation we invite any views on any perceived equality impacts. We are also seeking views on the potential impacts of the package as a whole on equality. We need to understand who this policy may affect and how it may affect them.

A regulatory impact assessment has been published for the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill. Impact assessments are required for all UK government interventions of a regulatory nature that affect the private sector and/or public services. The impact assessment is reviewed and rated by the Regulatory and Policy Committee prior to publication. DLUHC received a ‘Green’ rating[footnote 1] from the RRPC on 1 July 2022 meaning the impact assessment is fit for purpose.

Duration

This consultation will last for 12 weeks from 17 March to 9 June 2023.

Following the closure of this consultation, the government will assess responses. In doing so, a response will be issued that summarises the themes that emerged, before issuing a final consultation on the draft regulations after the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill achieves Royal Assent.

Enquiries

Any queries about this consultation should be directed to:

InfrastructureLevyConsultation@levellingup.gov.uk.

How to respond

We strongly recommend that responses are submitted through Citizen Space.

Citizen Space is an easy-to-use, digital tool that will significantly aid the process of analysing responses, and respondents are encouraged to use this avenue to send responses.

Please use this link to access the consultation via Citizen Space.

Alternatively, you can email your response to:

InfrastructureLevyConsultation@levellingup.gov.uk.

Responses sent to this email address should make it clear which questions you are responding to.

Written responses should be sent to:

Infrastructure Levy Technical Consultation

Planning Directorate

3rd Floor

Fry Building

2 Marsham Street

London, SW1P 4DF

When you reply, please specify whether you are replying as an individual or submitting an official response on behalf of an organisation and include:

- your name

- your organisation (if applicable)

- an address (including post-code)

- include ‘Infrastructure Levy Consultation response’ in your correspondence

- an email address, and

- a contact telephone number.

Privacy Notice

Please read our Privacy Notice.

Executive summary

The government wants to make sure that local authorities receive a fairer contribution of the money that typically accrues to landowners and developers. This will support funding for the infrastructure – affordable housing, schools, GP surgeries, green spaces and transport infrastructure to support connectivity that local communities expect to come with new development.

To do this, the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill (‘the Bill’) seeks to replace the current system of developer contributions with a mandatory, more streamlined, and locally determined Infrastructure Levy. The Bill provides the framework for the new Levy, with the detailed design to be delivered through regulations.

The Levy will be charged on the value of the property at completion per square metre and applied above a minimum threshold. Levy rates and minimum thresholds will be set and collected locally, and local authorities will be able to set different rates within their area.

This will allow developers to price the value of contributions into the value of the land and for Levy liabilities to reflect market conditions. It will also remove the need for planning obligations to be renegotiated if the gross development value (GDV) is lower than expected; while allowing local authorities to share in the uplift if GDVs are higher than anticipated.

The Infrastructure Levy will be a more efficient system, largely sweeping away the sometimes-protracted negotiation of Section 106 planning obligations (“s106”) (Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990). It will be more transparent, as Levy charging schedules will make the expected value of a contribution clear up-front. It will also make it clear to existing and new residents what new infrastructure will accompany development and to developers what infrastructure will be required to make development acceptable. This will ultimately create a more consistent system, which removes unnecessary delay and provides additional funds to local communities.

To strengthen infrastructure delivery, the Bill requires local authorities to prepare Infrastructure Delivery Strategies. These will set out a strategy for delivering local infrastructure and spending Levy proceeds. The Bill will also enable local authorities to require the assistance of infrastructure providers, the local community, and other bodies in devising these strategies and their development plans.

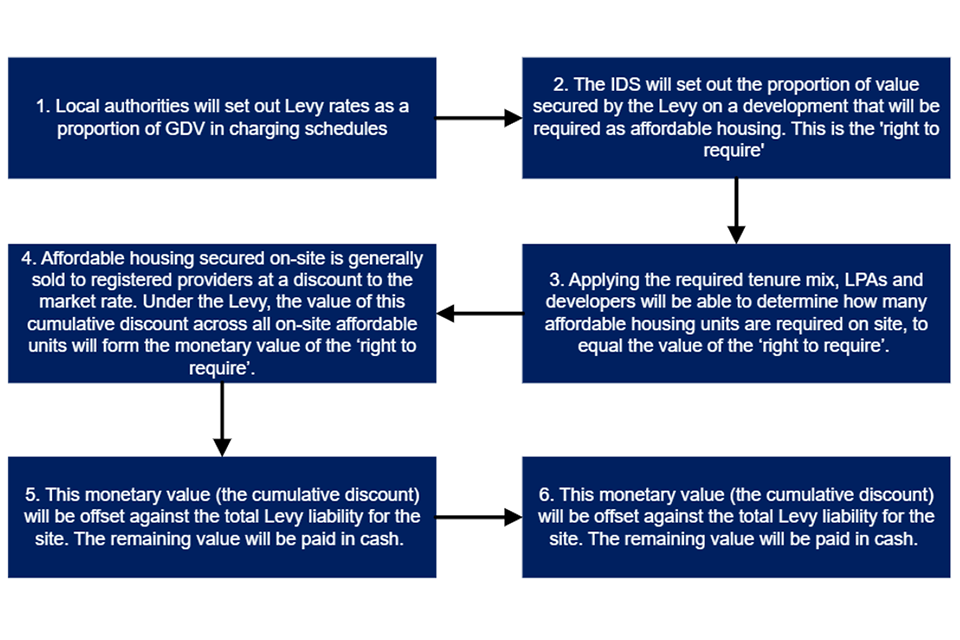

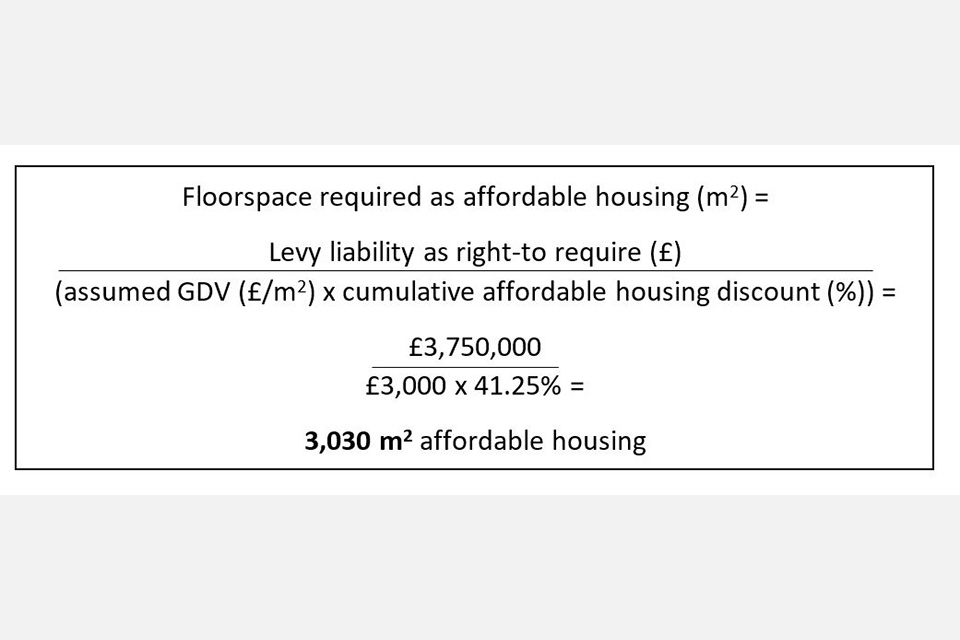

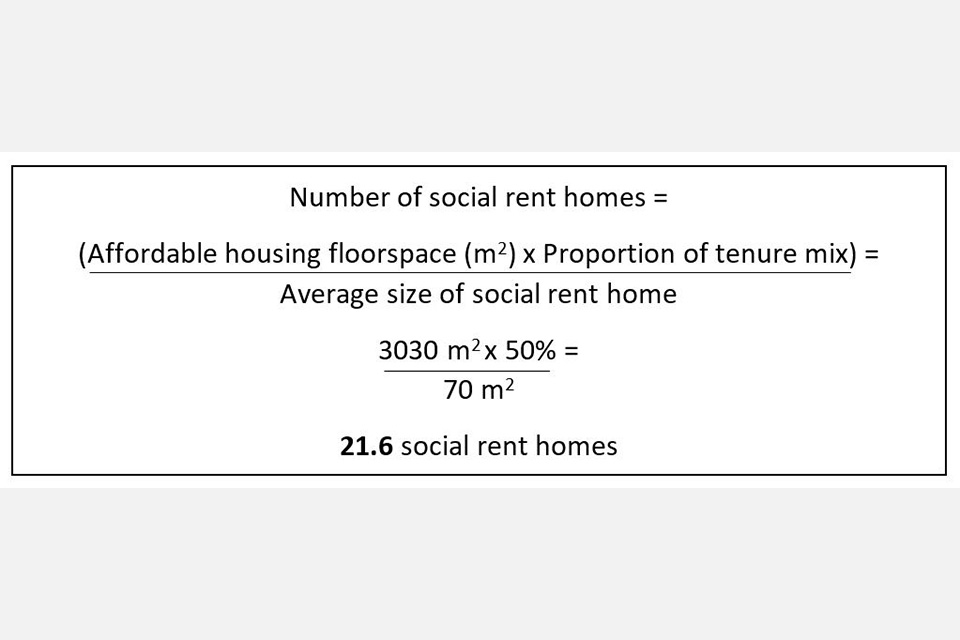

The government is committed to the Levy securing at least as much affordable housing as developer contributions do now. A new ‘right to require’ will enable local authorities to set out what proportion of the Levy they want delivered as affordable homes and what proportion they want delivered as cash. As the developer will be obliged to deliver these apportionments, the ‘right to require’ will afford greater protection to policy compliant levels of affordable housing. That is because, under the existing system, levels of affordable housing are often negotiated downward on viability grounds, resulting in fewer units being delivered than a local authority initially sought. The non-negotiable nature of the Levy provides an opportunity to address this. The ‘right to require’ means that where local authorities set out how much of the Levy they want as affordable housing, that amount will be delivered without the risk of a downward negotiation.

The proposal for the Levy set out in this document has been informed by responses to the Planning for the Future White Paper and by direct engagement with key stakeholders.

Consultation outline

- Primary legislation in Part 4 and Schedule 11 of the Bill provides the overarching framework for the Infrastructure Levy. Schedule 11 inserts new Part 10A into the Planning Act 2008, comprising of new sections 204A to 204Z1. It is based on the existing Planning Act 2008, Part 11 provisions, which provide for the CIL framework. As with CIL, the detailed design of the new Levy will be set out in regulations. The Bill introduces the following components of the Levy:

- The Levy will be a mandatory charge.

- Levy rates are to be set by charging authorities (generally the local authority), and when setting rates, they must take into account certain factors. This includes the viability of development in the area and the desirability that rates can deliver affordable housing at a level equalling or exceeding what developers deliver now in that area.

- There is a process of examination in public of Infrastructure Levy charging schedules, in order for rates to be adopted.

- The Secretary of State for DLUHC can intervene in the preparation of charging schedules in certain circumstances.

- Charging authorities must publish an Infrastructure Delivery Strategy.

- Once the Bill reaches Royal Assent, these elements of the Infrastructure Levy will feature in primary legislation. Therefore, the government is not seeking views on these aspects of the Levy.

- This technical consultation seeks responses on those elements of design that will be delivered through regulations, made under the framework set out in primary. A summary of the lead proposals for the Levy, and corresponding chapters in the consultation document, can be found below.

Chapter 1: Fundamental design choices: proposals

- Scope of the Levy. The Levy will apply to all types of development, aside from where exemptions apply. Changes of use through permitted development rights will also fall within scope in a manner that ensures such schemes remain viable.

- Types of infrastructure under the Levy. Infrastructure ‘integral’ to the successful functioning of a site, such as on-site play areas, site access and internal highway network or draining systems, will be delivered by developers and secured through planning conditions. Where this is not possible, ‘integral’ infrastructure will be delivered through targeted planning obligations known as ‘Delivery Agreements’. All other forms of infrastructure – ‘Levy funded’ infrastructure – will be paid for through Levy revenues. Questions 2 and 3 seek views on the definitions of ‘integral’ and ‘Levy funded’ infrastructure. Questions 4-6 seek views on spending the Levy on matters typically considered non-infrastructure items.

- Use of Section 106. S106 will be retained in the new system but for restricted purposes. Sites will come forward through three different ‘routeways’ depending on their character. In each routeway, s106 will play a role.

- The routeways seek to strike a balance between reducing negotiation and delay and allowing local authorities to secure the infrastructure and affordable housing they need. Questions 7 and 8 seek views from respondents on these routeways.

- The core routeway. The majority of schemes will be subject to this routeway. The Levy will function as a cash-based system where rates and thresholds apply. S106 agreements will retain a restricted function, limited to securing matters that cannot be conditioned for.

- The infrastructure in-kind routeway. On the largest and most complex sites, often with unique infrastructure requirements, s106 agreements can be used to deliver infrastructure as an in-kind payment of the Levy. The value of this agreement must equal or exceed what would have been secured in cash through a calculation of Levy liabilities.

- The s106-only routeway. Sites where Gross Development Value (GDV) per m2 cannot be calculated, or where buildings are not the main focus of development, such as minerals or waste sites, will not be subject to the Levy. Planning obligations will apply as now.

Chapter 2: Levy rates and minimum thresholds

- Rate setting. Levy rates and minimum thresholds (below which no Levy is charged) will be set by the local authority. Rates and thresholds can be varied by the type of development (including brownfield and greenfield) and local authorities can create different charging zones. Levy charging schedules will be subject to consultation and public examination. Questions 11 seeks views on instances where some brownfield sites should qualify for offsets from final Levy liabilities, where the nature of a fixed-rate Levy could unduly effect scheme viability.

Chapter 3: Charging and paying the Levy

-

Charging the Levy. Levy liabilities will be based on GDV at the point of site sale or completion. The consultation seeks views on where circumstances may warrant payment of the Levy at an earlier stage of development.

-

Payment of the Levy. Basing the Levy on GDV requires a novel proposal around Levy payments. Indicative liabilities will be calculated using Levy charging schedules. These will set out expectations of Levy liabilities that reflect assumed values of a site. A provisional payment of the Levy will be made close to scheme completion. A final adjustment payment can be used on completion incorporating final values to ensure correct liabilities are discharged. Views are sought on this process in response to Questions 14 and 15, and alternative proposals are welcomed.

Chapter 4: Delivering Infrastructure

- Forward funding infrastructure. Borrowing against future Levy proceeds will be permitted, including from the Public Works Loan Board, to facilitate the forward funding of infrastructure. Cash reserves can also be built up across sites. Questions 18-20 ask respondents to consider the mechanics behind infrastructure delivery under the Levy.

- The Infrastructure Delivery Strategy. Through a new Infrastructure Delivery Strategy, local authorities will be able to take a more strategic and unified approach to infrastructure planning and delivery. That includes how they expect to spend Levy proceeds to accommodate the needs of the community such as through the provision of GP surgeries and schools. The Infrastructure Delivery Strategy will be subject to examination, and the consultation seeks views on what should form the content of the document, including the process of input from infrastructure providers and local residents. Questions 24-29 seek views on the Infrastructure Delivery Strategy.

Chapter 5: Affordable housing

- Affordable Housing. The government is committed to delivering at least as much – if not more – on-site affordable housing as developer contributions do now. On-site affordable housing can be delivered as an in-kind payment of the Levy through a new ‘right to require’ which will enable local authorities to secure affordable homes as a proportion of levy liabilities. The consultation seeks views on the ‘right to require’ and in what circumstances exemptions from the Levy for register provider-led schemes could be appropriate.

Chapter 6: Other areas

- The neighbourhood and administrative share. Imitating provisions under the existing Community Infrastructure Levy legislation, both a neighbourhood share, and administrative share of the new Levy will be able to be retained to support funding of local community priorities and Levy administration respectively.

- Exemptions and reduced rates. The Levy will replicate some existing exemptions from CIL. The consultation seeks views on the case for other suitable exemptions or reduced rates, including a proposal to apply exemptions to qualifying small sites and publicly funded infrastructure. The consultation also seeks views on enforcement mechanisms.

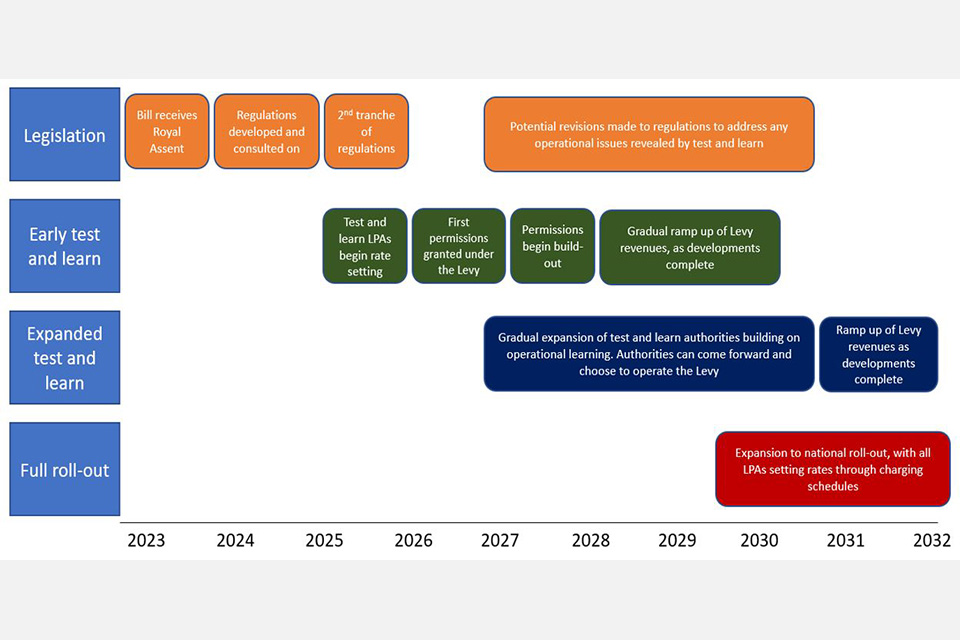

Chapter 7: Introducing the Levy

- Test and learn. A reform of this scale represents a substantial change for housebuilders, local authorities, registered providers of affordable housing and other parts of the sector. That is why the Infrastructure Levy will be introduced through a phased ‘test and learn’ process over several years, which will support the effective implementation of the Levy, and provide local authorities and industry time to prepare and adapt to the change. Prior to national roll-out, the government will monitor, evaluate, and improve the operation of the Levy. Local authorities that are interested in becoming a ‘test and learn’ authority are invited to express their interest.

- Transition to the new system. Sites permitted before the introduction of the new Levy will continue to be subject to their CIL and s106 requirements. We are considering whether further transitional provisions are needed to account for sites which are delivered over longer time periods. However, these sites will not be moved into the new Levy system. The consultation seeks views on whether the proposed approach will ensure effective transition and implementation of the new system.

Introduction

What is the Infrastructure Levy?

The Infrastructure Levy will be a locally-set, mandatory charge levied on the final value of completed development to replace the existing system of developer contributions. By charging the Levy on the value of completed development, the amount collected will increase as development prices increase, or reduce as prices drop, making the Levy more responsive to market conditions.

The aim of the Levy is to create a swifter, simpler, more transparent system, and one that will raise at least as much revenue as at present, if not more, for local authorities to provide the infrastructure and affordable housing that communities need. A summary of the new Levy and how it compares to the existing system of developer contributions is shown in Table 1, at the end of this section.

Why does the existing system need to be reformed?

New - development creates demand for infrastructure. To create sustainable development and successful places, it is important that this demand is addressed and appropriately planned for. Contributions from developers, which are secured by capturing a proportion of the uplift in the value of land generated by the granting of planning permission, are a key tool in mitigating the impacts of new development, alongside wider government funding for infrastructure and affordable housing.

Under the current system, there are 2 broad routes for local authorities to secure developer contributions. Planning obligations, through Section 106 (i.e. “s106” of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990) agreements, are negotiated with developers, and the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) (enacted by SI 2010/948) which is a fixed charge levied on the floorspace of a new development.

Developer contributions estimated to be worth around £7 billion were agreed in 2018/19, of which £4.7 billion was in the form of affordable housing contributions. However, planning obligations are uncertain and opaque. That they are subject to negotiation (and can be subject to subsequent renegotiation), can create uncertainty for communities over the level of infrastructure and affordable housing that will be delivered, as well as leading to substantial delays in the granting of planning permission.

CIL is more transparent and predictable. However, it is inflexible in changing market conditions and unable to efficiently capture value where increases in value occur after rates have been set. The Neighbourhood Share of CIL enables a proportion of total CIL receipts to be spent in the location of a scheme, in agreement of the local community. The Infrastructure Levy will maintain a Neighbourhood Share, for the same purpose. This is explained further in Chapter 6.

The government believes that it should address the issues with the existing system and reconsider how value is captured from new development and to create a simpler, non-negotiable, and streamlined system that can capture more value and provide better outcomes for communities.

On what basis will the Levy be charged?

The Levy will be charged to the GDV per m2 of completed development. This means that development will be charged on a basis that is consistent, transparent, and fair. It will be sensitive to the differing values of one development compared to another and to changing market conditions. Should a development prove more valuable than anticipated, the Levy will capture a fair share of the additional value for local authorities and communities; where development is worth less than expected, developers will contribute less, but without the need to renegotiate their obligations.

The final GDV will be reflected in the sales price of the development, or a valuation of the market price if the development is not sold. Some additional estimates of the final liability will be required earlier in the process of developing a site, providing developers and local authorities with a clear indication of how much respectively they are likely to pay and receive.

The government recognises that charging a Levy on GDV is a significant change from the current system. It also recognises that valuations will be needed in some circumstances to determine liabilities, and that this creates potential areas of dispute and additional administration. We intend for the ‘test and learn’ rollout to help manage and optimise this process, ultimately resulting in a system that reduces negotiation and creates opportunity for local authorities to capture greater value for communities.

Will the Levy raise more revenue?

The Levy is designed to be able capture more revenue. Independent research commissioned by the department (See Annex A) suggests that there is scope to capture more value, with the greatest scope on greenfield sites with higher development values, and that local authorities will have flexibility to set rates on such sites to capture more value. How much more value might be captured will vary from one development to another and depend on multiple factors, including how effectively rates and minimum thresholds are set. When setting rates, local authorities will need to balance their aim to capture land value with the importance of ensuring that land continues to come forward for development. This will be a local judgement and will be informed by the amount of value captured for specific development typologies under the existing system in their area.

Will the Infrastructure Levy be more complicated than the existing system?

Once in operation across England, the new, single system of developer contributions will remove a substantial element of negotiation, which is often responsible for slowing build-out and can result in outcomes unfavourable to local authorities. Charging schedules will set out Levy rates up front, which will add certainty for both developers and local authorities, and ultimately make for a system that is easier to navigate, more straightforward, and transparent.

Where planning obligations are retained in the new Levy system, such as on the largest and most complicated sites, an element of negotiation will remain. However, the value of any agreement will need to equal or exceed the Levy liability had the site been subject to the core Levy routeway (see Chapter 1).

The aim of the Infrastructure Levy is to create a fairer and simpler system of developer contributions, which will ultimately capture more value for local authorities and local communities.

How will the Levy work?

There are three main elements to operating the Levy, which will build on the approaches taken to setting and collecting CIL: (i) setting the Levy; (ii) charging and collecting the Levy; and (iii) spending the Levy. Local authorities will be responsible for setting Levy rates, charging, collecting, and spending the Levy, enabling the Levy to reflect local circumstances and priorities.

(i) Setting the Levy

Local authorities will set a minimum threshold (on a £ per m2 basis), below which the Levy will not be charged. This is to account for the costs of development in an area, and the value of the land in its existing use, broadly meaning that the Levy is charged on the increase in land value created by a development. Rates will be set as a percentage figure of the final GDV above the minimum threshold.

Hence, for solely illustrative purposes, if a local authority were to set a minimum threshold of £1,500 per m2, and the GDV of a completed development was £2,500 per m2, then the Levy will be charged only on the £1,000 per m2 that is above the threshold.

Local authorities will be able to set different rates and/or thresholds for different development uses and land typologies in their local area. The Levy will apply to most types of development, but certain types may be exempt or subject to reduced rates.

The charging schedule that sets out Levy rates and thresholds will remove in most instances the time-consuming negotiation of s106 agreements and provide considerably more certainty for local authorities and developers. In setting rates, local authorities will have to consider various factors (to be provided for expressly in the regulations), which will include a requirement that rates are set with regard to the desirability of maintaining or exceeding the levels of affordable housing that are currently secured through developer contributions in their area.

We will also set out a mechanism that enables rates to be set at a lower level initially, and then to be stepped up over time. This will allow local authorities to set rates with a larger viability buffer to begin with, but which captures more value over time. Where local authorities are setting rates under the Levy, they should be taking as their starting point how much they actually receive through the existing system, including the amount of affordable housing received. They will need to balance the aim of capturing land value with ensuring that land continues to come forward, meaning that rates set will be a local judgement based on local evidence.

(ii) Charging and collecting the Levy

The Levy will be charged by local authorities, based on the GDV of a development upon its completion. What is meant by ‘completion’ in this context will be a matter for regulations. This approach allows developers to price in the amount of their contributions into the value of the land, based on the projected GDV and the amount charged, to be responsive to market conditions. This removes the need for planning obligations to be renegotiated if the GDV is lower than expected and allows local authorities to share in the value uplift if GDVs are higher than anticipated.

By allowing the Levy to be charged on most types of development, local authorities will be able to capture value where there is scope to do so from development types for which little or no contributions are collected at present. That could also include some types of development under permitted development rights, if rates are set in a manner that keeps such schemes viable. Such development types could be subject to reduced Levy rates to ensure they are accommodated in the Levy without challenge to their viability.

As designed, the Levy will require valuations of GDV during build-out of a development. The government is seeking views as to how this could function in practice (Question 20) as well options for the timings of payments (Questions 18 and 19) and the routeways by which the Levy might be charged (Questions 7 and 8).

(iii) Spending the Levy

The delivery of the right infrastructure ahead of or alongside development is a priority for the government. This will help support new development with the services it needs. For residential development, this includes important infrastructure that a community needs and will mitigate the impact of a new scheme like schools, health facilities such as GP surgeries, the provision of sustainable transport infrastructure and connectivity, including active travel, or new public green spaces or other types of green infrastructure.

For commercial development, this could include improving public transport connections to increase accessibility and enable active travel. The Levy will be an important source of funding for local authorities to deliver infrastructure priorities for their area to support planned development.

Should the Levy generate more revenue than is collected under the present system, proceeds could be focused on providing more of the infrastructure that communities need. The Levy could also be used to deliver support for the local community in ways that do not typically meet the definition of ‘infrastructure’. This is explored further in Chapter 1 and we seek views on when this could be appropriate at Questions 4-6.

We propose to delineate between different types of infrastructure under the Levy. ‘Integral’ infrastructure, which is needed for a site to function, will be delivered by developers primarily through the use of planning conditions. ‘Levy-funded infrastructure’ refers to infrastructure that is supported by Levy receipts and mitigates the cumulative impact of new development on the local area. This consultation seeks views on these concepts and how they can be defined most effectively (Questions 2 and 3)

To identify and plan for infrastructure priorities, local authorities will be required to prepare a new document, called an Infrastructure Delivery Strategy. This document will set out the local authority’s strategic plans for infrastructure delivery to support growth and how they intend to spend the Levy to address infrastructure and affordable housing need. The Infrastructure Delivery Strategy will provide communities with an opportunity to engage with how the Levy may be spent, and a clear view of how local authorities will use Levy receipts on their behalf. Chapter 4 expands on the Infrastructure Delivery Strategy and seeks views on its possible content (Questions 24-29).

The government is also committed to the Infrastructure Levy being able to deliver at least as much affordable housing as developer contributions do now, and the Levy has been designed to meet that goal. On-site affordable housing on residential schemes will be delivered predominantly as an in-kind payment of the Levy through a new ‘right to require’.

The ‘right to require’ will see a percentage of the Levy value delivered in-kind by developers as on-site affordable housing, in a manner that protects it from the pressure of other spending priorities. Developers will be obliged to provide the in-kind contribution, rebalancing how and what is delivered and removing time-consuming negotiations from the process. Views are sought on the approach to affordable housing in Chapter 5, including how to ensure that registered provider-led schemes receive appropriate treatment under the Levy, as per Question 31.

How will the Levy be implemented?

Prior attempts to improve land value capture have sometimes encountered challenges, which in part have arisen from the quick implementation of substantive reforms. We understand that the Levy will be a big change to the planning system and that local authorities will require support upon its introduction. This is why we are consulting on aspects of design now and intend to take a phased ‘test and learn’ approach to implementation.

We want to ensure the Levy is implemented in a way that navigates these hurdles, so that it can achieve the aim of capturing more land value uplift and deliver at least as much affordable housing. The ‘test and learn’ approach will see the Levy introduced in selected local authorities in the first instance, before full roll-out across England. During the ‘test and learn’ period, the government will work closely with local authorities, developers, affordable housing providers, and other stakeholders operating the Levy to monitor, evaluate, and improve its operation. Should other local authorities wish to adopt the new system ahead of its full introduction, they will be able to do so.

Following the passage of the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill, this consultation will help to inform the drafting of regulations, which themselves will be subject to consultation. Once regulations are introduced, we expect ‘test and learn’ authorities to introduce charging schedules from late 2024/25, and operating the Levy from 2025/26. National rollout will occur over the course of a decade and the current system will remain in place in areas which have not adopted the Levy. More detail on the prospective timeline can be found in Chapter 7 of this document.

| Means of developer contributions | Current system: Section 106 (as applied currently) | Current system: Community infrastructure Levy | The proposed new Infrastructure Levy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statutory basis | Town & Country Planning Act 1990 | Planning Act 2008 | Levelling Up & Regeneration Bill |

| Type of contribution | Negotiated planning obligation | Tax-like charge | Tax-like charge |

| Scope | Most development, but in practice obligations do not accompany a significant proportion of cases | Most development but significant exemptions apply | Most development, applied more widely than at present but with some exemptions |

| Mandatory or voluntary for local planning authorities? | Voluntary, subject to negotiation | Voluntary; There are currently 162 charging authorities |

Mandatory |

| Basis of charge | Local policy sets expectations, actual contributions are negotiated on viability grounds | Gross internal floor area of a development | Gross value of a development |

| Charging schedule | None | Requirement to consult followed by an examination in public | Requirement to consult followed by an examination in public |

| Responsive to market conditions | Yes But only subjectively and by time-consuming negotiation |

No Because liability is based on floorspace and is fixed when permission is granted |

Yes Because liability is based on final gross development value |

| Can be used to secure affordable housing? | Yes Secured at levels subject to negotiation |

No Unable to secure affordable housing |

Yes Secured as a non-negotiable, in-kind proportion of the liability |

| Can be used to deliver infrastructure? | Yes Delivered by developers directly or by local authorities via a cash payment, subject to negotiation; directly related to the development and necessary to make the development acceptable in planning terms |

Yes Delivered via cash receipts (although some scope for in-kind contributions, not commonly used) |

Yes Delivered by developers directly and/or via cash receipts; value is non-negotiable. |

| Includes a neighbourhood share? | No | Yes Can be passed on to other bodies to spend on neighbourhood priorities |

Yes Can be passed on to other bodies to spend on neighbourhood priorities |

| Is there a mandatory spending plan | Not mandatory Local authorities can set out priorities in an infrastructure delivery plan/Infrastructure Funding Statement, and report on spending as part of an Infrastructure Funding Statement |

Not mandatory CIL charging authorities may have a CIL spending plan or set out priorities in an infrastructure delivery plan/Infrastructure Funding Statement |

Yes Requirement for an Infrastructure Delivery Strategy |

Chapter 1: Fundamental design choices

Key parts of the Bill that this Chapter relates to include Part 4, clauses 124, 125, and 126 and 122, and the following sections of new Part 10A of the Planning Act 2008 (inserted by Schedule 11, Part 1 of the Bill):

- 204A: The Levy

- 204B: The Charge

- 204D: Liability

- 204E: Liability: interpretation of key terms

- 204F: Charities

- 204G: Amount

- 204Z: Regulations: general

Scope of the Levy

1.1 Under the current system of developer contributions, all local authorities can use discretionary s106 planning obligations to secure mitigations for development. In addition, all local authorities can charge CIL and around half of them do. Under the new system, introduced by the Bill, it will be mandatory for local authorities in England to charge the Infrastructure Levy in their area when it is implemented there.

1.2 The Levy will increase the scope of developer contributions in several ways:

-

More development overall will be subject to a mandatory regime. CIL, which is non-negotiable for developers when charged, is widely acknowledged to increase developer contributions, with 60% of CIL charging authorities reporting increases in land value capture following its introduction, and 38% of non-CIL charging authorities believing it will enhance value capture. The mandatory nature of the Infrastructure Levy, and the coverage across all of England, will mean that development that currently escapes making significant contributions will be brought into the regime, and will be required to contribute.

-

The non-negotiable nature of the Levy will mean that developers must take full account of the Levy payments they will make when agreeing a price for land. They will not be able to overpay for land and then negotiate their contributions downwards through the use or misuse of viability assessments. Case studies developed by the University of Liverpool show that there is scope for additional land value capture in a number of cases, particularly relating to greenfield developments. A more certain, non-negotiable Levy will give local authorities scope to seek an increase in value capture over time.

-

The types of development which are subject to the Infrastructure Levy can also be expanded from the existing system of developer contributions. For instance, many types of change of use are de facto exempt from existing developer contributions. These can be brought into the new Levy with appropriate, lower rates charged to ensure such types of development remain viable. This is covered in Chapter 2.

Definition of development under the Levy

1.3 The Bill defines development for the purposes of the Infrastructure Levy at new section 204E(1) in Schedule 11 of the Bill. The definition is broad, covering the creation of new buildings and changes of use in existing buildings, but allows for regulations to set out in more detail what is and is not to be treated as development for the purposes of the Levy. Section 204G(8)(f) sets out that regulations may be used to provide, permit or require differential rates including nil rates, while section 204Z(1) makes clear that levy regulations may make provision that applies generally or only to specified cases, circumstances or areas.

1.4 We anticipate that most development types will be subject to the Levy, including residential, commercial, and industrial development. Local authorities can continue to set different rates for different types of development, as they do under CIL currently.

1.5 We will define the parameters of ‘development’ for the purposes of the Levy in regulations. This definition broadly means that structures that are buildings, and used by people, will qualify as ‘development’. A straightforward approach will be to maintain the definitions from CIL, which define what does not constitute development, including:

- Development of less than 100 square metres, unless this consists of one or more dwellings.

- Buildings into which people do not normally go.

- Buildings into which people go only intermittently for the purpose of inspecting or maintaining fixed plant or machinery.

- Structures which are not buildings, such as pylons and wind turbines

1.6 We are interested, as per Question 1, in whether stakeholders consider that the 100 square metre threshold remains appropriate, in terms of the scale of development that is exempt, and whether this should be a full exemption or a reduced rate. New Section 204E(1)(c)makes an addition to existing definitions of ‘development’. Namely, by adding “any change in the use of an existing building or part of a building”, this expands what kinds of development can be subject to the Levy. This is explored further in Chapter 2.

1.7 In addition to what is and is not defined as development, CIL has a series of exemptions, including for residential extensions and affordable housing. Further details about exemptions to the Levy are given in Chapters 5 (as they relate to affordable housing) and 6 (as they relate to other areas).

Question 1: Do you agree that the existing CIL definition of ‘development’ should be maintained under the Infrastructure Levy, with the following excluded from the definition:

- developments of less than 100 square metres (unless this consists of one or more dwellings and does not meet the self-build criteria) – Yes/No/Unsure

- Buildings which people do not normally go into - Yes/No/Unsure

- Buildings into which peoples go only intermittently for the purpose of inspecting or maintaining fixed plant or machinery - Yes/No/Unsure

- Structures which are not buildings, such as pylons and wind turbines. Yes/No/Unsure

Please provide a free text response to explain your answer where necessary.

The types of infrastructure that can be funded by the Levy

1.8 The delivery of the right infrastructure at the right time is a priority for the Government. The Levy will be an important source of funding for local authorities to deliver infrastructure that supports planned development. It will replace CIL in England as a means of funding infrastructure and will largely replace the negotiated Section 106 regime. Whilst there will remain a role for s106 agreements in limited circumstances (see later in this chapter), affordable housing and contributions to infrastructure required as a result of cumulative development will be secured through the Levy on the majority of sites.

1.9 For most schemes, payment of the Levy will require a certain percentage of the liability to be delivered in-kind as affordable housing (see Chapter 5). The Levy is non-negotiable, and so this approach removes the need for contributions towards this type of infrastructure to be negotiated on a site-by-site basis. This will decrease the delays currently experienced in the planning system from s106 negotiations that can derive from agreeing affordable housing contributions.

1.10 When a new scheme is built out, some on-site infrastructure will be required to make sure that the site itself can function successfully. It makes practical sense that infrastructure which is ‘integral’ to how the site is designed and how it operates should be integrated into the build cost of a scheme and delivered by the developer. Other forms of infrastructure, which are not needed for a particular site to function but are needed to address the cumulative impact of development, will be delivered using the cash raised by the Levy.

1.11 This creates two categories of infrastructure, which are (1) infrastructure needed for a scheme to function, which is ‘integral’ to the site and will be delivered by developers (or through an appropriate sub-contractor) outside of the Levy charge and (2) ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure delivered by the local authority using cash receipts from the Levy.

1.12 It is important that the distinction between the two categories is clear, so developers know what they are expected to deliver as part of their build costs, and that local authorities can consider those costs effectively when setting charging schedules. The dividing line between ‘integral’ and ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure is subject to this consultation, and will be set through regulations, policy, and guidance.

Integral infrastructure

1.13 Where on-site infrastructure is needed to make a site liveable, it is practical that the developer delivers that infrastructure alongside the development. This will aid site operation and ensure that critical, site-specific infrastructure is delivered in a timely fashion.

1.14 The approach to integral infrastructure does not constitute a significant departure from what happens in the current planning system. On-site mitigation is often required to meet planning policy requirements, is often incorporated into build costs, and is secured through planning conditions and s106 agreements.

1.15 On that basis, it is anticipated that developers will cost in ‘integral’ infrastructure as part of the build cost for a scheme and for it to be delivered in addition to payments of the Levy. This will broadly ensure that Levy revenues are not used to fund infrastructure that would normally be part of the costs of development. Some examples of what ‘integral infrastructure’ might include are:

- Cycle parking areas

- Electric vehicle charging points

- Inclusion of sustainable urban drainage systems and flood and site-specific coastal erosion risk mitigation

- Carbon reduction design measures to meet building regulations

- Biodiversity enhancements and net gain

- Private amenity space

- Street trees and on-site green infrastructure

- On-site play areas and open space for residents

- The creation of safe, high quality, adoptable internal road layouts, that prioritise pedestrian movements and sustainable transport modes as well as, where appropriate, well designed agreed levels of multi-modal parking, including for disabled users, car clubs and electric vehicles

- Any requirements of a Section 278 or Section 38 agreement (of the Highways Act 1980) – New or improved movement infrastructure to either become, or continue to be maintainable at the public expense within or directly adjacent to the site, including but not limited to:

- footways;

- bus stops and shelters;

- segregated cycle routes;

- crossings;

- traffic calming;

- Carriageways, including shared space;

- Public on-street car parking and

- Any other form of traffic management including traffic signals

1.16 These examples of ‘integral’ infrastructure are site-specific and embedded into the design of the site and relate to its functionality and or accessibility. What is considered as ‘integral’ infrastructure may vary, however, and depend on the size of the development and its on-site needs.

1.17 That said, creating certainty for developers, through clear parameters of what should be considered ‘integral’ will be essential for this kind of infrastructure to be effectively costed into scheme delivery. Equally, LPAs will need to consider the costs of ‘integral’ infrastructure when preparing their charging schedules.

1.18 That said, creating certainty for developers, through clear parameters of what should be considered ‘integral’ will be essential for this kind of infrastructure to be effectively costed into scheme delivery. Equally, local authorities will need to consider the costs of ‘integral’ infrastructure when preparing their charging schedules. Where the government sets requirements for additional contributions to be collected separately to the Levy, such as the Biodiversity Net Gain, these will be considered as integral infrastructure, and local authorities will be expected to account for these costs when setting Levy rates.

1.19 Where possible, planning conditions will be the primary means of securing ‘integral’ infrastructure, though planning conditions cannot cover all scenarios where this kind of infrastructure will be required. To ensure ‘integral’ infrastructure is successfully secured, we are proposing to retain a constrained, narrowly targeted use of s106 agreements, known as ‘Delivery Agreements’. These will be used to plug gaps in what planning conditions cannot secure.

1.20 In terms of delivering ‘integral’ infrastructure, a Delivery Agreement will be used to ensure that a scheme complies with policy or design codes and delivers all infrastructure deemed to be ‘integral’. That means a Delivery Agreement will have wider usage than securing on-site infrastructure, in order to cover all purposes of planning obligations and to support the proper mitigation of the effects of development on a site, where this would not be covered by the Levy. The role of Delivery Agreements is explained further in this chapter. In certain circumstances, where contributions are required to deliver a site, delivery agreements could be used to ensure that a contribution is made, for instance for suitable alternative natural green spaces.

Levy-funded infrastructure

1.21 New section 204N will require regulations to apply the Levy to supporting the development of an area by funding the provision, improvement, replacement, operation or maintenance of infrastructure. It includes a non-exhaustive list of what infrastructure could mean in this context, which can broadly be defined as infrastructure required as a result of the cumulative growth in the local area.

1.22 Unlike ‘integral’ infrastructure, ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure is not dependent on the functionality or physical location of a scheme. Levy receipts will be used to deliver infrastructure that is required because of planned growth that will have a cumulative impact on an area and creates the need for new infrastructure to mitigate its impact. Examples of ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure could include:

- Expansion or improvements to local healthcare infrastructure such as GP surgeries or the provision of new facilities

- Expansion or improvements to schools and other educational facilities, including the provision of childcare facilities

- Flood risk infrastructure

- Improvements to road and highway infrastructure

- Improvements to local emergency services infrastructure

- Improvements to water and wastewater infrastructure networks

- Additions to local bus services

- Provision of play equipment and other street furniture outside of the site boundary

- Strategic green infrastructure and tree planting/maintenance

- Enhancements to local play pitches or sports facilities

- The delivery of strategic multi-modal movement infrastructure, for example:

- A new or enhanced movement corridor

- A strategic walking, wheeling or cycling route

- Enhancements to public transport routes

- An area wide intervention such as a liveable neighbourhood or controlled parking zone

1.23 Levy receipts can also be passed to third parties such as county councils, highways authorities, and water and sewerage undertakers, if they are best placed to deliver the infrastructure. We are also exploring the possibility for developers to pay elements of the Levy through land payments if an area of the development, for instance, is to be used for building a school.

1.24 Local authorities will also be able to use cash secured through the Levy to buy land if that is necessary to deliver infrastructure. However, there may be times when this approach will lead to less-than-optimal outcomes, leading to infrastructure which is inconveniently located in relation to its users.

1.25 To address this, local authorities may indicate in their Infrastructure Delivery Strategy (see Chapter 4) that on sites over a certain size they expect a certain proportion of land to be set aside for ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure. These requirements should be taken into account when assessing the GDV of these sites, in order to set Levy rates. In line with our approach to affordable housing, it will also be possible to require that a certain amount of floorspace should be given over to local infrastructure priorities, and for this to be offset from the Levy accordingly.

Distinguishing effectively between ‘integral’ and ‘Levy-funded infrastructure’

1.26 The lists of what might be considered ‘integral’ and ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure are not comprehensive. Through regulations, policy, and guidance, and following further consultation and engagement, the demarcation will be made clear and distinct. We recognise that any approach to ‘integral’ and ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure, which does not provide clarity may lead to inappropriate Levy rates being set, as the costs to developers of providing ‘integral’ infrastructure are not properly accounted for, or it could create uncertainty for developers and local communities as to what integral infrastructure will be provided alongside development.

1.27 It will also be important to identify circumstances where drawing a clear line between ‘integral’ and ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure will be challenging. For example, we envisage that the majority of developments will make a contribution to local schools and healthcare facilities like GP surgeries in paying the Levy, meaning these would be considered as ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure. However, a site may sometimes require a GP surgery or school on-site, and it could be argued that an on-site matter could fit into either category of infrastructure. It is important that there is a clear and consistent approach on these situations. We also appreciate that LPAs will have local circumstances to consider.

1.28 There are several possible tools we can use to create an appropriate distinction. One of, or a combination of the approaches outlined below could be adopted.

a) A set of principles established in regulations or policy. For infrastructure to be considered ‘integral’, it may be that a combination of principles must be met, which could include:

i. Design: the mitigation relates to how the site is designed or interacts physically with the wider area

ii. Liveability: the mitigation relates to the quality of the development itself

iii. Beneficiaries: the mitigation is primarily for the benefit of those who inhabit the development or are directly impacted by the development

iv. Predictability: it is clear to the developer that they will be required to make this kind of contribution

v. Individuality: it is required to mitigate an individual development, rather than the pooled impacts of multiple developments

b) A nationally set list of types of infrastructure that are either ‘integral’ or ‘Levy-funded’ set out in regulations or policy. Such typologies can never be exhaustive but can deal with many common types of infrastructure. For instance, on-site green spaces and play areas and certain environmental mitigations might be set at a national level as integral infrastructure, which developers are expected to contribute.

c) Principles and typologies are set locally. With reference to national policies and guidance, local authorities will be able to set out any specific items that they will be seeking as integral contributions, through their infrastructure delivery strategy (see Chapter 4).

Question 2: Do you agree that developers should continue to provide certain kinds of infrastructure, including infrastructure that is incorporated into the design of the site, outside of the Infrastructure Levy? [Yes/No/Unsure]. Please provide a free text response to explain your answer where necessary.

Question 3: What should be the approach for setting the distinction between integral and Levy-funded infrastructure? [ see para 1.28 for options a), b), or c) or a combination of these]. Please provide a free text response to explain your answer, using case study examples if possible.

Using the Levy to fund other local needs

1.29 Under the existing system of developer contributions, local authorities may sometimes provide small amounts of revenue funding where this is considered necessary in planning terms. The Levy also allows for funding to go towards the operation and maintenance of infrastructure – for example, funding for the upkeep of a green space for a set period of time. Local authorities have considerable flexibility under the existing system to negotiate s106 agreements, as long as they are necessary in planning terms, directly related to the development, and fair in terms of scope and scale. National policy sets a broad framework for local authority decision making in how they direct their funds towards particular priorities, but it is the local authority that decides how it wishes to prioritise the purposes to which it puts developer contributions.

1.30 Under new section 204N(5), and via regulations, we will be able to allow local authorities funding for non-infrastructure matters, such as revenue funding for services.

1.31 It should be noted that the Levy is, in essence, a one-off payment made in relation to a development, whereas revenue funding of services is an ongoing obligation. This means that the ongoing delivery of a service cannot be funded in the long-term by levy revenues from a specific development. Services are also funded from other sources, including central and local government funding.

1.32 Nonetheless, local authorities may wish to have flexibility to provide contributions towards service funding for local priorities. This will ultimately be a matter for local authorities to decide and consider when developing their Infrastructure Delivery Strategy subject to regulations (see Chapter 4). It is possible that this may occur once a local authority has met its requirements for affordable housing and infrastructure needs, the latter of which will be essential to making new development acceptable. This approach will also help ensure that as much affordable housing is delivered as under the current system and that development is well supported by infrastructure that the community needs.

1.33 However, the Bill provides a flexible framework whereby regulations could allow local authorities the flexibility to direct an element of their levy funding towards non-infrastructure matters, like social care, subsidised or free childcare schemes, or improving local services including service provision. The detail of this will be set out in regulations, but we are seeking views (question 5) on whether those regulations should require that the local authority prioritise affordable housing and physical infrastructure.

Question 4: Do you agree that local authorities should have the flexibility to use some of their levy funding for non-infrastructure items such as service provision? [Yes/No/Unsure] Please provide a free text response to explain your answer where necessary.

Question 5: Should local authorities be expected to prioritise infrastructure and affordable housing needs before using the Levy to pay for non-infrastructure items such as local services? [Yes/No/Unsure]. Should expectations be set through regulations or policy? Please provide a free text response to explain your answer where necessary.

Question 6: Are there other non-infrastructure items not mentioned in this document that this element of the Levy funds could be spent on? [Yes/No/Unsure] Please provide a free text response to explain your answer where necessary.

The role of Section 106 agreements - the proposed Levy routeways

1.34 The Levy aims to create a simpler and more consistent system than the current system of CIL and s106. However, paying the Levy may not always be enough to fully mitigate the impact of a development and make it acceptable in planning terms. Indeed, there are some situations where sites have very complex infrastructure needs, which necessitates retaining a negotiated approach to developer contributions. That is why we do not propose to remove s106 agreements altogether.

1.35 New Section 204Z1 of the Bill sets out that regulations can provide for how s106 of the Town and Country Planning Act may or may not be used. This power enables s106 planning obligations to be crafted in the new system, to support how infrastructure will be delivered under the Levy. To create a clear distinction over how s106 agreements should be used in different circumstances, we propose creating three distinct routeways for securing developer contributions. How infrastructure is secured and how s106 agreements operate in each routeway will vary, and this will reflect the size and type of site being brought forward.

1.36 The 3 routeways are as follows:

1. The core Levy routeway

2. Infrastructure in-kind routeway

3. S106-only routeway

1.37 An overarching framework for these ‘routeways’ will be set out in regulations, following further consultation. Based on this framework, the routeway which will apply to a particular kind of site will be set out in the Local Plan.

The core Levy routeway

1.38 The majority of new development will be subject to the core Levy routeway. Here, the Levy will be paid in cash by developers, with liabilities based on final GDV above a minimum threshold. The distinction between ‘integral’ and ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure will apply with Levy receipts used to fund the latter. We see the role for s106 agreements in this routeway as a new product – ‘Delivery Agreements’ – that will be used to secure ‘integral’ infrastructure in circumstances where conditions cannot be used. In limited circumstances, Delivery Agreements could also be used to request additional money outside of Levy liabilities.

1.39 This might include facilitating additional payments where a development does not meet planning policy requirements, securing a covenant on land in perpetuity, or maintaining in perpetuity rural exception sites. Under the core Levy routeway, delivery agreements could also be used to secure a timely minimum payment towards off-site mitigation that is needed to make the development acceptable, such as to ensure that any requirements of the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations can be met. Infrastructure Levy receipts could be used to fund this, but we want to ensure confidence when mitigation will be delivered and in situations where the Levy may not raise sufficient funds to do so, setting out a minimum amount the developer will need to pay to mitigate the impact of the development, (in the event that the Levy charge does not raise sufficient funds), ensures that it can still be taken forward.

1.40 Any obligations contained in a Delivery Agreement will be subject to existing CIL Regulations (regulation 122) restrictions, and additional regulatory restrictions on use. Local authorities will continue to be able to use section 278 and section 38 agreements in relation to highways matters. However, Delivery Agreements will not be a means to request additional contributions from developers towards ‘Levy-funded’ infrastructure.

1.41 Under the core Levy routeway, affordable housing can be secured as an in-kind contribution of Levy liabilities. This means that the value of affordable housing secured can be offset against the total amount of Levy owed. How this mechanism will operate, and how affordable housing can be secured under the Levy, is explained in further detail in Chapter 5.

The infrastructure in-kind routeway

1.42 We propose retaining negotiated s106 planning obligations for large and complex sites. On these sites, highly bespoke infrastructure needs often arise, which can have a transformative effect on an area, and can sometimes take 15 to 20 years to deliver. These sites also require specialised infrastructure to be delivered at specific times throughout the development period. For qualifying schemes, s106 obligations will be used as a tool to secure infrastructure and affordable housing as an in-kind contribution of the Levy.

1.43 This is a practical approach to the largest sites, as it will reduce situations where developers pay the Infrastructure Levy, for that cash to then be passed back to them to deliver infrastructure. On a large scheme, this more flexible approach will help accommodate the transformative impact such a scheme will have on an area, and ensure a wide-ranging agreement can be in place to aid the efficiency that infrastructure projects, and the scheme itself, can be delivered.

1.44 There are, however, key differences from how s106 agreements will function under the Levy than they do in the existing system. First, the value of any contributions towards infrastructure will have to equal or exceed the value of what otherwise would be secured through a calculation of the Infrastructure Levy. This means that the value of that agreement cannot, through the process of negotiation, go below a certain monetary value. This will be known as a ‘Levy backstop amount’. Our preferred approach is that any shortfall in the value of the infrastructure provided on site, or contributed to, will be made up through a cash payment to the local authority. This approach not only provides a baseline for negotiations but ensures fairness between the two routeways.

1.45 Second, the infrastructure in-kind routeway will only apply to qualifying sites that fall over a certain threshold based on site size, limiting the use of s106 across the system.

1.46 Where the threshold for this routeway is set will have significant implications for the final design of the Levy. If the threshold for the infrastructure in-kind routeway is low, more sites will qualify, which means there is greater the scope for developers to deliver infrastructure as an in-kind contribution. If it is set high, and fewer schemes qualify, then, through the local plan, clear expectations may need to be set about how the land is to be used. For example, if a site requires a new school or GP surgery to mitigate the direct impacts of the site, rather than the cumulative impacts of population growth, this will need to be made clear in the local plan so that the development cost can be taken account of in the setting of rates.

1.47 Where the threshold for this routeway is set will have significant implications for the final design of the Levy. If the threshold for the infrastructure in-kind routeway is low, more sites will qualify, which means there is greater the scope for developers to deliver infrastructure as an in-kind contribution. If it is set high, and fewer schemes qualify, then, through the local plan, clear expectations may need to be set about how the land is to be used. For example, if a site requires a new school or GP surgery to mitigate the direct impacts of the site, rather than the cumulative impacts of population growth, this will need to be made clear in the local plan so that the development cost can be taken account of in the setting of rates.

1.48 There are several options:

a) A high threshold. A threshold could be set so only the very largest and most complex sites are suitable for the ‘infrastructure in-kind’ routeway. This could include new settlements of 10,000 homes and above, or complex urban regeneration sites with large scale redevelopment of existing buildings. Given the benefits of a tax-like system provided by the Levy, this is our preferred option. It will mean that the greatest number of sites possible are subject to the core Levy routeway.

b) A medium threshold. A threshold could be set that is somewhat lower to cover urban extensions. This could be somewhere between 2,000 and 4,000 units for example.

c) A low threshold. A threshold could be set that is far lower, such as for sites over 500 units. That lower number of units is for illustrative purposes only and we wish to test the principle of a lower threshold. We are not currently in favour of setting a low threshold, given the associated levels of negotiation this will entail, which the Infrastructure Levy seeks to reduce.

d) Local authority discretion. An alternative approach could be that local authorities set their own qualifying threshold for this routeway, which they could set out in their Infrastructure Delivery Strategy (see Chapter 4). Guidance will set parameters for how local authorities should take this decision. For the Infrastructure in-kind routeway, the role of s106 agreements will also be defined through consultation and regulations.

Question 7: Do you have a favoured approach for setting the ‘infrastructure in-kind’ threshold? [high threshold/medium threshold/low threshold/local authority discretion/none of the above]. Please provide a free text response to explain your answer, using case study examples if possible.

The S106-only routeway

1.49 A minority of developments, such as those which do not meet the definition of development set out in 204E of the Bill (such as mineral and waste sites), will not be charged to the Levy and remain subject to s106 planning obligations as now. S106 will operate subject to the restrictions about the use of s106 currently set out in CIL regulation 122, which sets out the circumstances in which s106 obligations can be a reason for granting planning permission.

Table 2: The restricted role of S106 under the Levy in the three Infrastructure Levy routeways

| Policy approach/routeway | Integral Infrastructure | Levy-funded Infrastructure | Delivery of Affordable Homes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Core Levy routeway | Planning conditions and Delivery Agreements | Cash payment of Levy liabilities | In-kind payment of Levy liabilities (where residential development is proposed) |

| 2. Infrastructure In-Kind routeway | Planning conditions or s106 agreements where needed | In-kind payment of Levy liabilities secured through s106 agreements | In-kind payment of Levy liabilities (where residential development is proposed) |

| 3. S106-only routeway | The distinction between integral and Levy-funded infrastructure does not apply. s106 agreements used as now | The distinction between integral and Levy-funded infrastructure does not apply. s106 agreements used as now | No affordable housing sought |

Question 8: Is there anything else you feel the government should consider in defining the use of s106 within the three routeways, including the role of delivery agreements to secure matters that cannot be secured via a planning condition? Please provide a free text response to explain your answer.

Chapter 2: Levy rates and minimum thresholds

Key parts of the Bill that this Chapter relates to include the following sections of new Part 10A of the Planning Act 2008 (inserted by Schedule 11, Part 1 of the Bill):

- 204E: Liability: interpretation of key terms

- 204G: Amount

- 204H: Charging schedule: consultation and evidence

- 204I: Charging schedule: examination

- 204J: Charging schedule: examiner’s recommendations

- 204K: Charging schedule: approval

- 204X: Secretary of State: power to permit alteration of IL rates and thresholds

- 204Y: Secretary of State: power to require review of charging schedules

Setting rates and minimum thresholds

2.1 A key trade-off in designing the Levy concerns managing complexity and maximising land value capture. Seeking to maximise value capture by charging a bespoke Levy per development, for example, could capture more value but introduces significant uncertainty and operational complexity. A highly simplified Levy where national or regional rates are applied will be easier to navigate but is unlikely to be sufficiently flexible to ensure it can capture at least as much value as the current system. The government is seeking to strike an appropriate balance to manage this tension by allowing local authorities to set their own rates and minimum thresholds (a threshold for liability below which the Levy will not be charged).

2.2 To capture more value than the current system, local authorities will need to be able to maximise Levy revenues whilst maintaining the viability of development in their area. Localised rate and threshold setting will enable local authorities to reflect local land values and circumstances in how they prepare a Levy charging schedule. Doing so also provides the flexibility to bring development into scope of developer contributions which is typically out of scope in the current system.

2.3 The existing CIL framework serves as a foundation for how Levy rates and minimum thresholds will be set. A Levy charging schedule, which must be issued in accordance with new section 204G, will set out Levy rates and minimum thresholds. Having these rates set up front will remove, in most instances, the time-consuming negotiation of s106 agreements and provide considerably more certainty for local authorities and developers alike.

2.4 In determining their charging schedules, the Bill stipulates that local authorities must have regard to various factors. These include the degrees to which revenues and levels of affordable housing generated by developer contributions will compare to those at present, the viability of development, and an Infrastructure Delivery Strategy (to outline how local authorities intend to spend Levy receipts, including the proportion to be put towards affordable housing). Local authorities will use appropriate available evidence to inform how they prepare their charging schedules, and the schedule will then be subject to public examination.

2.5 As per new section 204G, local authorities will be able to set different rates and/or minimum thresholds for different development uses and land typologies in their local area. This approach will also allow the Levy to be aligned to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). The NPPF prescribes substantial weight to the value of using suitable brownfield land and the Levy will need to facilitate these policy intentions. This may result in local authorities taking the decision to set a lower rate for brownfield development and higher rates being applied to greenfield development, where appropriate. This would reflect the higher existing use values and construction costs typically associated with brownfield sites.

2.6 A local authority may take such a choice as brownfield land tends to have a higher existing use value and may be subject to costly remediation. Such an approach might be delivered through the use of different charging zones (as with CIL now). It may also be appropriate for local authorities to apply different Levy rates and minimum thresholds to residential and commercial development respectively, to reflect the differences in build costs and development values. In each instance, rates must be prepared in a way that allows different kinds of development in an area to remain viable.

Make-up of minimum thresholds

2.7 New section 204G, enables regulations to permit charging schedules to operate by reference to several elements related to development, including floorspace. This will allow local authorities to set a minimum threshold for Levy liability (on a £ per m2 basis), below which the Levy will not be charged. A minimum threshold will account for the costs of development in an area, and the value of the land in its existing use, broadly ensuring that the Levy is charged only on the additional value of a development.

Make-up of Levy rates

2.8 New section 204G(8)(b) provides that regulations may permit charging schedules to operate by reference to any measurement of the amount or nature of development. The Levy will be applied as a percentage figure charged on the GDV of a scheme above the minimum threshold. Levy rates will be charged to the internal area (m2) of a development as a percentage of the final GDV (£ per m2) above this minimum threshold. In simple cases, such as housing development sold on the open market, the final GDV will be the sales value of the housing.

2.9 Basing the charge on final sale GDV means liabilities will track price changes in the development market. In the event of a fall in house prices, for example, Levy liabilities will automatically reduce and, where prices rise faster than expected, the Levy will make sure the community benefit from that increase in value. By automatically reflecting changes in market prices, the Levy removes one of the key drivers behind negotiation in the existing system.

Setting ‘stepped’ levy rates

2.10 With the existing system, local authorities need to balance the infrastructure needed to support new schemes with viability. Some local authorities may set high requirements for affordable housing contributions, with the expectation these will be reduced on marginally viable sites. CIL-charging authorities may also account for viability by setting rates cautiously. Local authorities will also be able to create a ‘buffer’ to maintain viability in how they set the Levy.

2.11 The Bill, at new section 204G(6)(f), will allow provision to be made in the regulations for Levy charging authorities to set ‘stepped’ rates which increase at specified future points. That will enable rates to be set with a greater buffer initially, but which can be stepped up over time. Stepped rates will serve as a useful tool when implementing the Levy, reducing the risks of both overly ambitious rate setting (which may lead to landowners withholding land) and overly cautious rate setting (which could see a reduction in value captured).

Dealing with the variability of sites

2.12 Levy rates and minimum thresholds should be set at levels appropriate to be charged to sites that are typical of a typology of development which is in a local authority’s area. In doing so, they will balance the need to capture land value uplift with the need to ensure that development remains viable. A core part of this judgement will be the premium that is allowed for landowners above existing use value, in order to incentivise a landowner to bring their site forward for development. Local authorities will need to balance allowing a sufficient incentive, with the ambition to capture more value.

2.13 Other factors that will need to be taken into account when setting rates and minimum thresholds include the value per square metre of the site in its existing use, the density of any building in its existing use, demolition and remediation costs, build costs including ‘integral’ infrastructure, the extent of mitigation required to make the site acceptable, and the allowable density of the final development.

2.14 Our proposed approach to balancing viability and land value capture across variable sites is as follows:

- The application of a minimum threshold. The threshold means that broadly only value generated above the average costs of purchasing and developing a site is subject to developer contributions. This does mean that if the GDV of the site only just exceeds the minimum threshold, the total Levy liability will be low, and that if it substantially exceeds the minimum threshold, the total liability will be higher.

- Assessing the ‘window’ of possible rates and minimum thresholds. Local authorities should assess where rates and thresholds can be set, what a maximum rate could be, what they capture now, and how rates and thresholds account for construction costs and sale values within the local area.

- Local authorities should include a ‘buffer’ when setting rates and minimum thresholds. Rather than seeking a revenue maximising rate, applying a buffer will allow for circumstances such as higher than modelled existing use values, and higher than anticipated build costs to be incorporated into the price a developer will pay the landowner, and still leave a reasonable premium for the landowner. Local authorities may also set stepped rates (see above), to reduce this buffer over time, and to set long-term expectations for the level of the landowners’ premium.