Online Harms White Paper - Initial consultation response

Updated 15 December 2020

Joint ministerial foreword

The Rt Hon Baroness Morgan of Cotes Secretary of State, Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Secretary of State, Home Office

This is an exciting and unprecedented age of digital opportunity, and this government is committed to unleashing the full power of this country’s first-class technology and boosting our standing in the world. Digital advances will undoubtedly drive our economy and enrich our society, but to fully harness the internet’s advantages, we must confront the online threats and harms it can propagate, and protect those who are vulnerable to them.

That’s why we want to make the UK the safest place in the world to be online and the best place to start and grow a digital business. We will make sure the benefits of technology are spread more widely and shared more fairly. Our approach is guided by the need to promote fair and efficient markets where the benefits of technology are shared widely across communities; ensure the safety and security of those online; and maintain a thriving democracy and society, where pluralism and freedom of expression are protected.

By getting it right, we will drive growth and stimulate innovation and new ideas, whilst giving confidence and certainty to innovators and building trust amongst consumers. As we leave the EU, we have an incredible opportunity to lead the world in regulatory innovation.

As the internet continues to grow and transform our lives it is essential that we get the balance right between a thriving, open and vibrant virtual world, and one in which users are protected from harm.

The scale, severity and complexity of online child sexual exploitation and abuse is a concern for government, law enforcement and companies, with 16.8 million referrals of child sexual abuse material by US technology companies to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children in 2019. In the UK, law enforcement is making 500 arrests and safeguarding 700 children a month as a result of these referrals and other sources. Terrorist propaganda and vile online child sexual abuse destroy lives and tear families and communities apart. We cannot allow these harmful behaviours and content to undermine the significant benefits that the digital revolution can offer.

Two thirds of adults in the UK are concerned about content online, and close to half say that they have seen hateful content in the past year. Online abuse can have a severe impact on people’s lives and is often targeted at the most vulnerable in our society. Cyberbullying has been shown to have psychological and emotional impact. In a large survey of young people who had been cyberbullied, 37% had developed depression and 26% had suicidal thoughts. These figures are higher than corresponding statistics for ‘offline’ bullying, indicating the increased potential for harm.

This update shares some of the findings from the Online Harms White Paper consultation, as we work to ensure the digital revolution works for families, communities and businesses. We are grateful to everybody who responded to the consultation on our proposals to eradicate these corrosive and abhorrent harms. There were some clear themes amongst the responses which we will pay close attention to as we move towards the legislation announced in the Queen’s Speech.

Firstly, freedom of expression, and the role of a free press, is vital to a healthy democracy. We will ensure that there are safeguards in the legislation, so companies and the new regulator have a clear responsibility to protect users’ rights online, including freedom of expression and the need to maintain a vibrant and diverse public square.

We are also introducing greater transparency about content removal, with the opportunity for users to appeal. We will not prevent adults from accessing or posting legal content, nor require companies to remove specific pieces of legal content. The new regulatory framework will instead require companies, where relevant, to explicitly state what content and behaviour is acceptable on their sites and then for platforms to enforce this consistently.

Secondly, respondents emphasised the need for clarity and certainty for businesses, and proportionate regulation. Analysis so far suggests that fewer than 5% of UK businesses will be in scope of this regulatory framework. The ‘duty of care’ will only apply to companies that facilitate the sharing of user generated content, for example through comments, forums or video sharing. Just because a business has a social media presence, does not mean it will be in scope of the regulation. Business to business services, which provide virtual infrastructure to businesses for storing and sharing content, will not have requirements placed on them.

Thirdly, many respondents reinforced the importance of higher levels of protection for children, which will be reflected in the policy we develop through this consultation. The proposals assume a higher level of protection for children than for the typical adult user, including, where appropriate, measures to prevent children from accessing age-inappropriate or harmful content. This approach will achieve a more consistent and comprehensive approach to harmful content across different sites and go further than the Digital Economy Act’s focus on online pornography on commercial adult sites.

On the question of who will be taking on the role of the regulator, having listened to feedback from this consultation, we are minded to appoint Ofcom. This would allow us to build on Ofcom’s expertise, avoid fragmentation of the regulatory landscape and enable quick progress on this important issue.

We are a pro-technology government and we are keen to continue to work with industry to drive forward the digital agenda. We are continuing to work at pace to ensure the right regulatory regime and legislation is in place. The ICO has recently published its Age Appropriate Design Code, and more detailed proposals on online harms regulation will be released in the spring alongside interim voluntary codes on tackling online terrorist and child sexual exploitation and abuse content and activity.

In the meantime, we will continue our efforts to unlock the huge opportunities presented by digital technologies whilst minimising the risks.

To ensure that we keep momentum on a comprehensive package of measures we will be publishing and undertaking further work to address online harms, such as:

● government media literacy strategy

● The Law Commission’s consultation on abusive and offensive online communications

● a review into the market for technology designed to improve online safety, where the UK is a leading innovator

● developing our understanding and evidence base of online harms and approaches to tackling them. This is why we have supported cross-government research to understand how platforms can recognise their child users through age assurance

We are confident that this publication, and the other plans we are driving forward, will help us to achieve our objectives; making Britain the safest place to be online and the best digital economy in the world.

The Rt Hon Baroness Morgan of Cotes

Secretary of State, Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport

The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP

Secretary of State, Home Office

Executive summary

1. The Online Harms White Paper set out the intention to improve protections for users online through the introduction of a new duty of care on companies and an independent regulator responsible for overseeing this framework. The White Paper proposed that this regulation follow a proportionate and risk-based approach, and that the duty of care be designed to ensure that all companies have appropriate systems and processes in place to react to concerns over harmful content and improve the safety of their users - from effective complaint mechanisms to transparent decision-making over actions taken in response to reports of harm.

2. The consultation ran from 8 April 2019 to 1 July 2019. It received over 2,400 responses ranging from companies in the technology industry including large tech giants and small and medium sized enterprises, academics, think tanks, children’s charities, rights groups, publishers, governmental organisations and individuals. In parallel to the consultation process, we have undertaken extensive engagement over the last 12 months with representatives from industry, civil society and others. This engagement is reflected in the response.

3. This initial government response provides an overview of the consultation responses and wider engagement on the proposals in the White Paper. It includes an in-depth breakdown of the responses to each of the 18 consultation questions asked in relation to the White Paper proposals, and an overview of the feedback in response to our engagement with stakeholders. This document forms an iterative part of the policy development process. We are committed to taking a deliberative and open approach to ensure that we get the detail of this complex and novel policy right. While it does not provide a detailed update on all policy proposals, it does give an indication of our direction of travel in a number of key areas raised as overarching concern across some responses.

4. In particular, while the risk-based and proportionate approach proposed by the White Paper was positively received by those we consulted with, written responses and our engagement highlighted questions over a number of areas, including freedom of expression and the businesses in scope of the duty of care. Having carefully considered the information gained during this process, we have made a number of developments to our policies. These are clarified in the ‘Our Response’ section below.

5. This consultation has been a critical part of the development of this policy and we are grateful to those who took part. This feedback is being factored into the development of this policy, and we will continue to engage with users, industry and civil society as we continue to refine our policies ahead of publication of the full policy response. We believe that an agile and proportionate approach to regulation, developed in collaboration with stakeholders, will strengthen a free and open internet by providing a framework that builds public trust, while encouraging innovation and providing confidence to investors.

Our response

Freedom of expression

1. The consultation responses indicated that some respondents were concerned that the proposals could impact freedom of expression online. We recognise the critical importance of freedom of expression, both as a fundamental right in itself and as an essential enabler of the full range of other human rights protected by UK and international law. As a result, the overarching principle of the regulation of online harms is to protect users’ rights online, including the rights of children and freedom of expression. Safeguards for freedom of expression have been built in throughout the framework. Rather than requiring the removal of specific pieces of legal content, regulation will focus on the wider systems and processes that platforms have in place to deal with online harms, while maintaining a proportionate and risk-based approach.

2. To ensure protections for freedom of expression, regulation will establish differentiated expectations on companies for illegal content and activity, versus conduct that is not illegal but has the potential to cause harm. Regulation will therefore not force companies to remove specific pieces of legal content. The new regulatory framework will instead require companies, where relevant, to explicitly state what content and behaviour they deem to be acceptable on their sites and enforce this consistently and transparently. All companies in scope will need to ensure a higher level of protection for children, and take reasonable steps to protect them from inappropriate or harmful content.

3. Services in scope of the regulation will need to ensure that illegal content is removed expeditiously and that the risk of it appearing is minimised by effective systems. Reflecting the threat to national security and the physical safety of children, companies will be required to take particularly robust action to tackle terrorist content and online child sexual exploitation and abuse.

4. Recognising concerns about freedom of expression, the regulator will not investigate or adjudicate on individual complaints. Companies will be able to decide what type of legal content or behaviour is acceptable on their services, but must take reasonable steps to protect children from harm. They will need to set this out in clear and accessible terms and conditions and enforce these effectively, consistently and transparently. The proposed approach will improve transparency for users about which content is and is not acceptable on different platforms, and will enhance users’ ability to challenge removal of content where this occurs.

5. Companies will be required to have effective and proportionate user redress mechanisms which will enable users to report harmful content and to challenge content takedown where necessary. This will give users clearer, more effective and more accessible avenues to question content takedown, which is an important safeguard for the right to freedom of expression. These processes will need to be transparent, in line with terms and conditions, and consistently applied.

Ensuring clarity for businesses

6. We recognise the need for businesses to have certainty, and will ensure that guidance is provided to help businesses understand potential risks arising from different types of service, and the actions that businesses would need to take to comply with the duty of care as a result. We will ensure that the regulator consults with relevant stakeholders to ensure the guidance is clear and practicable.

Businesses in scope

7. The legislation will only apply to companies that provide services or use functionality on their websites which facilitate the sharing of user generated content or user interactions, for example through comments, forums or video sharing. Our assessment is that only a very small proportion of UK businesses (estimated to account to less than 5%) fit within that definition. To ensure clarity, guidance will be provided by the regulator to help businesses understand whether or not the services they provide or functionality contained on their website would fall into the scope of the regulation.

8. Just because a business has a social media page that does not bring it in scope of regulation. Equally, a business would not be brought in scope purely by providing referral or discount codes on its website to be shared with other potential customers on social media. It would be the social media platform hosting the content that is in scope, not the business using its services to advertise or promote their company. To be in scope, a business would have to operate its own website with the functionality to enable sharing of user-generated content, or user interactions. We will introduce this legislation proportionately, minimising the regulatory burden on small businesses. Most small businesses where there is a lower risk of harm occurring will not have to make disproportionately burdensome changes to their service to be compliant with the proposed regulation.

9. Regulation must be proportionate and based on evidence of risk of harm and what can feasibly be expected of companies. We anticipate that the regulator would assess the business impacts of any new requirements it introduces. Final policy positions on proportionality will, therefore, align with the evidence of risk of harm and impact to business. Business-to-business services have very limited opportunities to prevent harm occurring to individuals and as such will be out of scope of regulation.

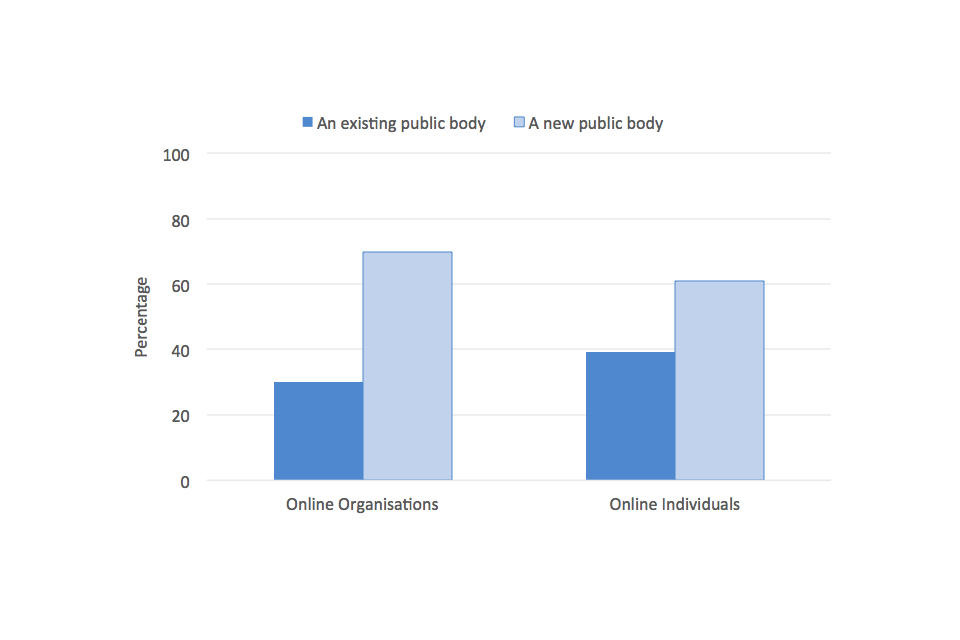

Identity of the regulator

11. We are minded to make Ofcom the new regulator, in preference to giving this function to a new body or to another existing organisation. This preference is based on its organisational experience, robustness, and experience of delivering challenging, high-profile remits across a range of sectors. Ofcom is a well-established and experienced regulator, recently assuming high profile roles such as regulation of the BBC. Ofcom’s focus on the communications sector means it already has relationships with many of the major players in the online arena, and its spectrum licensing duties mean that it is practised at dealing with large numbers of small businesses.

12. We judge that such a role is best served by an existing regulator with a proven track record of experience, expertise and credibility. We think that the best fit for this role is Ofcom, both in terms of policy alignment and organisational experience - for instance, in their existing work, Ofcom already takes the risk-based approach that we expect the online harms regulator will need to employ.

Transparency

13. Effective transparency reporting will help ensure that content removal is well-founded and freedom of expression is protected. In particular, increasing transparency around the reasons behind, and prevalence of, content removal may address concerns about some companies’ existing processes for removing content. Companies’ existing processes have in some cases been criticised for being opaque and hard to challenge.

14. The government is committed to ensuring that conversations about this policy are ongoing, and that stakeholders are being engaged to mitigate concerns. In order to achieve this, we have recently established a multi-stakeholder Transparency Working Group chaired by the Minister for Digital and Broadband which includes representation from all sides of the debate, including from industry and civil society. This group will feed into the government’s transparency report, which was announced in the Online Harms White Paper and which we intend to publish in the coming months.

15. Some stakeholders expressed concerns about a potential ‘one size fits all’ approach to transparency, and the material costs for companies associated with reporting. In line with the overarching principles of the regulatory framework, the reporting requirements that a company may have to comply with will also vary in proportion with the type of service that is being provided, and the risk factors involved. To maintain a proportionate and risk-based approach, the regulator will apply minimum thresholds in determining the level of detail that an in-scope business would need to provide in its transparency reporting, or whether it would need to produce reports at all.

Ensuring that the regulator acts proportionately

16. The consideration of freedom of expression is at the heart of our policy development, and we will ensure that appropriate safeguards are included throughout the legislation. By taking action to address harmful online behaviours, we are confident that our approach will support more people to enjoy their right to freedom of expression and participate in online discussions.

17. At the same time, we also remain confident that proposals will not place an undue burden on business. Companies will be expected to take reasonable and proportionate steps to protect users. This will vary according to the organisation’s associated risk, first and foremost, size and the resources available to it, as well as by the risk associated with the service provided. To ensure clarity about how the duty of care could be fulfilled, we will ensure there is sufficient clarity in the regulation and codes of practice about the applicable expectations on business, including where businesses are exempt from certain requirements due to their size or risk.

18. This will help companies to comply with the legislation, and to feel confident that they have done so appropriately.

Enforcement

19. We recognise the importance of the regulator having a range of enforcement powers that it uses in a fair, proportionate and transparent way. It is equally essential that company executives are sufficiently incentivised to take online safety seriously and that the regulator can take action when they fail to do so. We are considering the responses to the consultation on senior management liability and business disruption measures and will set out our final policy position in the Spring.

Protection of children

20. Under our proposals we expect companies to use a proportionate range of tools including age assurance, and age verification technologies to prevent children from accessing age-inappropriate content and to protect them from other harms. This would achieve our objective of protecting children from online pornography, and would also fulfil the aims of the Digital Economy Act.

Next steps

1. Online Harms is a key legislative priority for this government, and we have a comprehensive programme of work planned to ensure that we keep momentum until legislation is introduced as soon as parliamentary time allows. As mentioned above, this is an iterative step as we consider how best to approach this complex and important issue. We will continue to engage closely with industry and civil society as we finalise the remaining policy. While preparation of legislation continues, and in addition to the full response to be published in the spring, we are developing other wider measures in order to ensure progress now on online safety. These will include:

Interim codes of practice

2. The government expects companies to take action now to tackle harmful content or activity on their services. For those harms where there is a risk to national security or to the safety of children, the government is working with law enforcement and other relevant bodies to produce interim codes of practice.

3. The interim codes of practice will provide guidance to companies on how to tackle online terrorist and Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (CSEA) content and activity. The codes will be voluntary but are intended to bridge the gap until the regulator becomes operational, given the seriousness of these harms. We are continuing to engage with key stakeholders in the development of the codes to ensure that they are effective. We will publish these interim codes of practice in the coming months.

Government transparency report

4. The Online Harms White Paper committed the government to producing its first annual transparency report. We intend to publish this report in the next few months. The report will be informed by discussions at a multi-stakeholder Transparency Working Group chaired by the Minister for Digital and Broadband.

Non-legislative measures

5. The White Paper made clear that all users should have the tools and resources available to manage their own online safety, and that of others in their care. It committed the government to developing a media literacy strategy and we announced in the government’s response to the Cairncross Review that the strategy would be published in summer 2020. The media literacy strategy will ensure a coordinated and strategic approach to online media literacy education and awareness for children, young people and adults. It will aim to support citizens as users in managing their privacy settings and their online footprint, thinking critically about the things they come across online (disinformation, catfishing etc), and how the terms of service and moderating processes can be used to report harmful content. We will publish this in the summer of 2020.

6. We are keen to continue to work in partnership with tech companies and wider stakeholders to refine our approach, and to work on collaborative solutions, especially looking at how we can use technology to tackle these issues. Industries such as the safety tech sector are central to the government’s aim to promote innovation and develop a flourishing tech industry that also delivers technological solutions to meet regulatory requirements. To that end, we can also announce the upcoming publication of a full report into the safety technology ecosystem, which will identify opportunities for increasing competition and quality within the sector.

Wider regulation and governance of the digital landscape

7. As well as delivering on our commitments set out in the Online Harms White Paper, the government is undertaking an ambitious programme of wider work on how we govern digital technologies to unlock the huge opportunities presented by digital technologies whilst minimising the risks. Work on electoral integrity and related online transparency issues is being taken forward as part of the Defending Democracy programme together with the Cabinet Office.

8. We want the wider institutional landscape for digital technologies to be future-proof and fit for the digital age. As a result, over the coming months we will engage experts, regulators, industry, civil society and the general public to ensure our overarching regulatory regime for digital technologies is fully coherent, efficient, and effective.

Chapter one: Detailed findings from the consultation

1. The next sections cover:

-

Chapter One: Methodology of the written consultation and engagement with stakeholders across industry, civil society, international partners and user groups

-

Chapter Two: Responses on the regulatory framework (ie scope, user redress, industry transparency, enforcement options and appeals)

-

Chapter Three: Responses on the proposals for the independent regulator, regulatory accountability and funding models

-

Chapter Four: Responses to the non-legislative measures: the opportunities and challenges around technological innovation, safety by design, child online safety and education and awareness

Methodology - public consultation

2. Following the White Paper’s publication, we undertook a formal 12-week public written consultation, complemented by an extensive programme of stakeholder engagement. The written consultation took place between April and July 2019, and included 18 questions on aspects of the government’s plans for regulation and tackling online harms. In total, we gathered 2,439 responses from across academia, civil society, industry and the general public. The face-to-face stakeholder engagement enabled a constructive dialogue with key stakeholders, and those groups that may have been underrepresented in the written consultation.

Written consultation

3. We gathered written consultation responses via an online portal, email and post, both from organisations and from members of the public. Not all respondents engaged with every question - and indeed the response rate dropped throughout the questions. Of the 18 questions, 6 were closed questions with predefined response options on the online portal, allowing us to provide statistics for the responses to these questions for those who responded via the portal. These statistics, therefore, represent 63% of all responses (69% of all individuals and 32% of all organisations), and do not represent the major organisational respondents.

4. The remainder of the questions invited free text qualitative responses and each response was individually analysed. The response summaries below include the key themes and issues highlighted across all responses, but do not include statistics due to the nature of these questions.

5. A notable number of individual respondents to the written consultation disagreed with the overall proposals set out in the White Paper. Those respondents often seemed not to engage with the substance of questions on the specific proposals, but instead reiterated a general disagreement with the overall approach. This was most notable in those questions on regulatory advice, proportionality, the identity and funding of the regulator, innovation and safety by design, which seemed to attract a relatively large amount of confusion in responses. For these respondents, it was therefore difficult to delineate between an objection to the overall regime and an objection to the specific proposal within the question.

Profile of respondents

6. In total we received 1,531 online responses and 908 responses via email. 84% of these responses were from individuals and 16% from organisations (including tech sector, civil society, charities etc).

7. We collected demographic information for just over 90% of individuals who responded via the online portal, covering 58% of all responses:

-

Age: The largest proportions of responses were from those aged 45-54 (21%) and 55-64 (17%), followed by those aged 35-44 (16%) and 25-34 (15%). Respondents aged 18-24 and over 65 each made up 13% of the sample while 5% were under 18

-

Gender: Almost three quarters (72%) of respondents identified as male, with around a quarter (24%) female and 4% identified as “other”

-

Ethnicity: A little under two thirds (60%) of respondents identified as “White British/English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish”. Followed by 11% “White: Any other background”, 3% “asian”, 2% “mixed/multiple ethnic groups” and “Black/African/Caribbean background” respectively. Fewer than 1% identified as “Arab”, 13% selected “other” and 9% preferred not to say

-

Disability: Just over one in ten (11%) consider themselves as disabled under the Equality Act 2010, 75% do not and 14% preferred not to say.

8. As these demographics indicate, this sample, as with all written consultation samples, may not be representative of public opinion as some key groups are over- or under-represented.

9. A number of ‘campaigns’ were organised in response to the consultation from three sources: Samaritans, Open Rights Group, and Hacked Off. These responses were either identical or very similar and were submitted through central coordination. These responses were analysed and included in the same way as all other responses.

Engagement

10. Over the 12 week period we held 100 meetings, which supported the written consultation. This engagement enabled detailed conversations with a wide range of stakeholders and ensured we heard the views of important groups. Our engagement reflected the range of organisations that may be in scope of the online harms regulatory framework, including tech organisations, the games industry and retail. We also engaged with academia, regulators and civil society. Furthermore, we consulted the devolved administrations and discussed the policy in international multi-stakeholder fora and with international partners.

11. We recognise that some abuse or content which targets users based on actual or perceived protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010 means that some people face disproportionately negative experiences online. In line with this, during the consultation period we conducted workshops with groups representing users with various protected characteristics. This included engaging with a range of user groups representing those who are likely to be disportionately affected by online harms, such as the LGBTQ+ community; survivors of abuse and violence; disabled users; mental health organisations; religious groups; children, parents and child safety organisations. This engagement ensured groups were able to feed back expert knowledge on specific issues faced by the users they represent.

12. Engagement included a series of thematic workshops to consult on the core White Paper policies. These workshops focused on: the scope of regulation; transparency; enforcement powers; technology as a solution; safety by design; the regulator; user complaints; media literacy and education. Other meetings included 17 ministerial engagements, ‘deepdive’ sessions with major technology companies, and roundtable meetings with industry associations. We also engaged stakeholders on specific, key issues raised following the White Paper’s release, including the regulation of the press and freedom of expression, and the approach to the interim codes of practice on terrorist content and child sexual exploitation and abuse.

Summary of response findings:

13. The key themes from responses to the consultation and our engagement were:

-

The White Paper stated, on the activities and organisations in scope, that the regulatory framework will apply to online providers that supply services or tools which allow, enable or facilitate users to share or discover user-generated content or interact with each other online. Respondents welcomed the targeted, proportionate and risk based approach that the regulator is expected to take. Responses also highlighted the need to ensure that proposals remain flexible and able to respond as technology develops in the future. Companies and stakeholders, however, asked for more detail on the breadth of both services and harms in scope. Responses focused on ensuring that freedom of expression is protected.

-

The White Paper made clear that under the new duty of care, companies will need to ensure they have user redress mechanisms in place. This would mean that companies need to have effective, accessible complaints and reporting mechanisms for users to raise concerns about specific pieces of harmful content or activity and seek redress. The White Paper also highlighted a role for designated bodies to make ‘super complaints’ to the regulator to defend the needs of users. Respondents welcomed this, and highlighted the importance of ensuring that companies have effective reporting mechanisms for harmful content, accessible to all users. Organisations showed stronger support for the proposals for super-complaints than individuals did. Broadly, respondents requested more guidance on how a super-complaints function could work, and how it could take into account accountability and transparency mechanisms.

-

On transparency, the White Paper set out that companies in scope will be required to issue annual transparency reports. Respondents to the consultation as well as the stakeholders who were engaged highlighted the importance of transparency, both in terms of reporting processes and moderation practices. They see this as being central in holding companies accountable for enforcement of their own standards. Industry respondents suggested that transparency requirements should be proportionate – noting that a ‘one size fits all’ approach was unlikely to be effective and could be costly to implement for smaller companies.

-

The White Paper set out that the regulator will have an escalating range of powers to take enforcement action against companies that fail to fulfil their duty of care - including notices and warnings, fines, business disruption measures, but also senior manager liability, and Internet Service Provider (ISP) blocking in the most egregious cases. Respondents to the consultation as well as the stakeholders who were engaged recognised the role for a tiered enforcement structure, ensuring that enforcement powers are used fairly and proportionately. Civil society groups overall expressed support for firm enforcement actions in cases of non-compliance. Industry and rights groups expressed some concerns about the impact of some of the measures on the UK’s attractiveness to the tech sector and on freedom of expression. They sought further clarity on the intervention and escalation structure, including the grounds for enforcement. They want the regulator to support compliance with the regime in the first instance.

-

The White Paper proposed that companies have nominated representatives in the UK, to assist the regulator in taking enforcement action against companies based overseas. Respondents acknowledged that this system would support the effectiveness of the proposed legislation, however concerns were raised about the potential impact on smaller businesses.

-

The White Paper set out that the regulator will offer regulatory advice to companies on reasonable expectations for compliance, based on both the severity and scale of the harm, the age of their users and the size of the company and resources available to it. Respondents welcomed this. The main suggestions provided were on opportunities for the regulator to provide clarity on any specific standards and thresholds, alongside guidelines and expert advice on how organisations could comply.

-

The White Paper acknowledged that online harms can materialise via private communications services, and committed to setting out a differentiated framework for harm over private communications. Responses across stakeholders recognised the balance between taking appropriate action to address the serious harms, such as child grooming, that can be initiated and escalate from private forums and ensuring appropriate protections for users’ privacy. Most companies and organisations agreed that expectations of private services to tackle harm should be greater, firstly where content and activity is illegal, and secondly where children are involved. Most respondents opposed the inclusion of private communication services in scope of regulation. However, some responses - both from individuals and organisations acknowledged that abuse, harassment and some of the most serious illegal activity occur in private spaces, like closed community forums and chat rooms. These responses expressed support for the principle that platforms should be responsible for their users’ safety in private channels.

-

The White Paper set out that there must be an appeals mechanism for companies and others to challenge against a decision by the regulator when appropriate. Responses showed broad support for a mechanism allowing appeals against enforcement action by the regulator. Companies suggested that appeals mechanisms should be quick and affordable, focussed on the merits of the action taken and that administrative processes should be as streamlined as possible.

-

The White Paper stated that proportionality would be central to enforcement decisions by the regulator. Respondents welcomed the suggestion that the compliance systems could be designed similarly to current models in, for example, the finance sector. Specifically, they expressed support for options allowing companies to self-assess whether their services are in scope, and enabling members of the public to raise concerns with the regulator where a company is not complying.

-

The White Paper did not express a specific preference for the identity of the regulator. Most of the stakeholders we engaged with had no particular preference. Responses were supportive of a new body or of extending the duties of an existing regulator. Some feared that the latter option could prove overwhelming for an existing body and thus instead voiced support for a transitional or temporary body.

-

The White Paper set out that the regulator will be cost-neutral, and that for funding it would recoup costs via charges or a levy on companies in scope. Companies who responded to the consultation viewed the application of a charge with concern, citing worries around potential double or disproportionate costs to certain services and exemption for others.

-

The White Paper proposed a duty on the regulator to lay an annual report and accounts before Parliament and provide Parliament with information as and when requested for accountability. All groups generally expressed support for Parliament to have a defined oversight role over the regulator in order to hold it to account, maintain independence from government and build public trust and hold industry confidence.

-

The White Paper committed to developing a framework on safety by design and innovation, to make it easier for start-ups and small businesses to embed safety in their products. Stakeholders expressed broad agreement and recognition that safety is improved when organisations build in user-safety at the design and development stage of their online services. They also emphasised that machine learning solutions require extensive data and were supportive of the ‘regulatory sandbox’ model (i.e. allowing businesses to test innovations in a controlled environment).

-

The White Paper committed to make the UK the safest place to be online, having key regard for child online safety. Respondents welcomed this, and one of the key themes of our engagement was parents’ concerns about the safety of their children online. In particular, although parents felt that they know their children best and are therefore usually the best placed to tailor standard advice for them, they also agreed on the need for more advice and education on how to be online safely.

-

The White Paper recognised that users want to be empowered to manage their safety online, and that the regulator should consider education and awareness to support this. Throughout our engagement, digital education and awareness were key recurring themes. Many felt that the regulator could have an important role in creating a framework for evaluating the impact of existing education and awareness activity in their space. Others recognised that there could be a role for the regulator or for government in supporting the most vulnerable children and disseminating alerts about emerging online threats for young people.

Chapter two: Regulatory framework

1. The Online Harms White Paper set out the intention to bring in a new duty of care on companies towards their users, with an independent regulator to oversee this framework. The approach will be proportionate and risk-based with the duty of care designed to ensure companies have appropriate systems and processes in place to improve the safety of their users.

2. The White Paper stated that the regulatory framework will apply to online providers that supply services or tools which allow, enable or facilitate users to share or discover user-generated content, or to interact with each other online. The government will set the parameters for the regulatory framework, including specifying which services are in scope of the regime, the requirements put upon them, user redress mechanisms and the enforcement powers of the regulator.

3. The consultation responses indicated that some respondents were concerned that the proposals could impact freedom of expression online. We recognise the critical importance of freedom of expression, and an overarching principle of the regulation of online harms is to protect users’ rights online, including the rights of children and freedom of expression. In fact, the new regulatory framework will not require the removal of specific pieces of legal content. Instead, it will focus on the wider systems and processes that platforms have in place to deal with online harms, while maintaining a proportionate and risk-based approach.

4. To ensure protections for freedom of expression, regulation will establish differentiated expectations on companies for illegal content and activity, versus conduct that may not be illegal but has the potential to cause harm, such as online bullying, intimidation in public life, or self-harm and suicide imagery.

5. In-scope services will need to ensure that illegal content is removed expeditiously and that the risk of it appearing is minimised by effective systems. Reflecting the threat to national security and the physical safety of children, companies will be required to take particularly robust action to tackle terrorist content and online child sexual exploitation and abuse.

6. Companies will be able to decide what type of legal content or behaviour is acceptable on their services. They will need to set this out in clear and accessible terms and conditions and enforce these effectively, consistently and transparently.

7. We do not expect there to be a code of practice for each category of harmful content. We recognise that this would pose an unreasonable regulatory burden on in-scope services. However, we will publish interim codes of practice in the coming months to provide guidance for companies on how to tackle online terrorist and CSEA content and activity. The codes will be voluntary but are intended to bridge the gap and incentivise companies to take early action prior to the regulator becoming operational, thus continuing to promote behaviour change from industry on the most serious online harms. We are continuing to engage with key stakeholders in the development of the codes to ensure that they are effective.

8. We will expect the regulator to set expectations around imagery that may not be visibly illegal, but is linked to child sexual exploitation and abuse, for example, a series of images, some of which were taken prior to or after the act of abuse itself. We will consider further how to address this issue through the duty of care.

9. The legislation will only apply to companies that provide services which facilitate the sharing of user generated content or user interactions, for example through comments, forums or video sharing. Only a very small proportion of UK businesses (estimated to account for less than 5%) fit within that definition. To ensure clarity, guidance would be provided to help businesses understand whether or not the services they provide would fall into the scope of the regulation.

10. To be in scope, a business’s own website would need to provide functionalities that enable sharing of user generated content or user interactions. We will introduce this legislation proportionately. We will pay particular attention to minimising the regulatory burden on small businesses and where there is a lower risk of harm occurring.

11. We have listened to and taken into account feedback from industry stakeholders. It is clear that business-to-business services have very limited opportunities to prevent harm occurring to individuals and as such remain out of scope of the Duty of Care.

12. We are continuing the work on the final details of the organisations in scope, to ensure proportionality and effective implementation of our proposals. We will produce an impact assessment to accompany legislation which will take into account burdens to businesses.

Activities and organisations in scope

Are proposals for the online platforms and services in scope of the regulatory framework a suitable basis for an effective and proportionate approach?

Engagement

13. Throughout our engagement, organisations expressed support for the targeted, proportionate, and risk-based approach for the regulator. Many parties expressed a need for clarity as the proposals develop around the kind of organisation and platforms that would be in scope.

14. The tech industry, while broadly supportive, emphasised the importance of providing clear definitions of the companies and harms in scope, in particular addressing what is meant by ‘user generated content’. A number of organisations suggested that business to business (B2B) services should not be in scope, as their view was that there was a lower risk that the harms covered in the White Paper would develop on such platforms. Press freedom organisations and media actors also expressed the view that journalistic content should not be in scope, to protect freedom of expression and in accordance with established conventions of press regulation.

15. Civil society organisations representing disadvantaged groups demonstrated strong support for the proposals and emphasised the importance of including any provider of a platform or service made available to users in the UK within the scope of the regulation. Women’s groups , LGBT+, disability, and religious groups cited larger social media companies most frequently as the platforms of greatest concern, but were also concerned about smaller platforms, chat rooms, and anonymous apps, which they believe can easily be infiltrated for harm. A number of organisations suggested that economic harms (for instance, fraud) should be in scope. While the White Paper was clear that the list of harms provided was not intended to be exhaustive or definitive, a number of organisations suggested specific harms, for example misogyny. Many civil society organisations also raised concerns about the inclusion of harms which are harder to identify, such as disinformation, citing concerns of the impact this could have on freedom of expression.

Written consultation

16. Just over half of respondents to the written consultation answered this question. Responses which expressed support for the proposed platforms and activities in scope called on the government to increase education and public awareness of online harms. Responses also stressed the need to ensure that the proposals remain flexible and able to change as technology develops in the future, and that they maintain a special focus on young people and children.

17. Many respondents expressed concerns around the potential for the scope of the regulator to be too broad or for it to have an adverse impact on freedom of expression. Many of these respondents, therefore, called for further clarification of services and harms in scope. Some respondents also raised concerns that the proposals would have disproportionate impacts on specific organisations or, on the other hand, that they may not go far enough.

A systems based approach to online safety

The White Paper outlined a systems based approach:

-

The duty of care is designed to ensure companies have appropriate systems and processes in place to improve the safety of their users.

-

The focus on robust processes and systems rather than individual pieces of content means it will remain effective even as new harms emerge. It will also ensure that service providers develop, clearly communicate and enforce their own thresholds for harmful but legal content.

-

Of course, companies will be required to take particularly robust action to tackle terrorist content and online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse. The new regulatory framework will not remove companies’ existing duty to remove illegal content.

18. When broken down, the responses from organisations and members of the public differed in regard to the main perceived issues. For instance, concerns for freedom of expression were significantly more prevalent amongst individual respondents than amongst organisations. Instead, organisations reported a higher concern around the overreach of scope and a need for further clarity.

19. In general, organisations were more supportive of regulation when compared to public respondents. The tech sector and civil society groups expressed a level of support for the activities listed in scope, with many agreeing that focus should be on risk of harm, and that the regulator should take a proportionate approach to the companies in scope according to their risk profile.

20. At the same time, almost all industry respondents asked for greater clarity about definitions of harms, and highlighted the subjectivity inherent in identifying many of the harms, especially those which are legal. The majority of respondents objected to the latter being in scope.

21. Regarding harms in scope, several respondents stated that the 23 harms listed in the White Paper were overly broad and argued that too many codes of practice would cause confusion, duplication, and potentially, an over-reliance on removal of content by risk-averse companies. We do not expect there to be a code of practice for each category of harmful content, however, as set out above we intend to publish interim codes of practice on how to tackle online terrorist and Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (CSEA) content and activity in the coming months.

22. Specific groups echoed many of the general points raised in the written consultation, as well as suggesting specific services for inclusion in scope. For example, counter-extremism and religious groups noted the need for clarity to ensure that harms can properly be protected against and to minimise risks to constraining free expression. A common perspective among children’s charities was that gaming should be in scope.

23. Across responses and engagement, there was broad support for the proposed targeted, proportionate and risk-based approach that the regulator is expected to take. Responses also highlighted the need to ensure that proposals remain flexible and able to respond as technology develops in the future. However, companies and stakeholders wanted more detail on the breadth of both services and harms in scope. There was also a consistent focus on ensuring that freedom of expression was protected. Respondents welcomed the focus on protecting vulnerable users, including young people and children, and a number of respondents also suggested that further work should be done to increase education and public awareness of online harms.

User redress

24. The White Paper recognised that companies’ claims of having a strong track record on online safety are often at odds with users’ reported experiences. The White Paper made clear that, under the new duty of care, government expects companies to ensure they have effective, accessible complaints and reporting mechanisms for users to raise concerns about specific pieces of harmful content or activity and seek redress, or to raise wider concerns that the company has breached its duty of care. The White Paper also highlighted a role for designated bodies to make ‘super complaints’ to the regulator to defend the needs of users.

25. The regulator will have oversight of these processes, including through transparency information about the volume and outcome of complaints, and the power to require improvements where necessary. The regulator will be focused on oversight of complaints processes, it will not make decisions on individual pieces of content.

26. Recognising concerns about freedom of expression, while the regulator will not investigate or adjudicate on individual complaints, companies will be required to have effective and proportionate user redress mechanisms which will enable users to report harmful content and to challenge content takedown where necessary. This will give users clearer, more effective and more accessible avenues to question content takedown, which is an important safeguard for the right to freedom of expression. These processes will need to be transparent, in line with terms and conditions, and consistently applied.

Should designated bodies be able to bring super complaints to the regulator in specific and clearly evidenced circumstances? If your answer is yes, in what circumstances should this happen?

What, if any, other measures should the government consider for users who wish to raise concerns about specific pieces of harmful content or activity, and/or breaches of the duty of care?

Engagement

27. While the written consultation did not directly ask about internal company processes, many organisations shared their views in written responses and in supporting stakeholder engagement. They overwhelmingly agreed that companies should have effective and accessible mechanisms for reporting harmful content and felt that current processes often fell short. They agreed that this process should start with reports directly to the platform. Some respondents, including disability and children’s advocates, noted the importance of making these mechanisms accessible and prominent for all users, as they are often not easy to find on websites. Some also noted the importance of companies providing explanations to users whose content is removed, in order to protect rights and to help all users understand what is acceptable on different platforms. Some respondents also argued for a more standardised approach to reporting complaints to enable comparison and analysis.

28. A number of organisations highlighted concerns about a potential risk that the regulator would become the arbiter of what is considered harmful and the potential impact of this on freedom of expression.

29. A recurrent theme in organisational responses was that more effective complaints and reporting processes must also be accompanied by education and awareness-raising by companies and other stakeholders, including on people’s rights and responsibilities and the avenues available to them to raise concerns. Nevertheless, as the section summarising responses to the question of how users should be educated shows, there was no consensus on which body or bodies should be responsible for educating users.

30. We stated that we do not envisage a role for the regulator itself in determining disputes between individuals and companies. Several organisations agreed with this, noting that it would not be feasible for the regulator to look into individual complaints and that it could risk users’ rights to freedom of expression. Other respondents instead suggested that the regulator should have powers to look at specific cases, for example those which are particularly high-profile or serious.

Written consultation

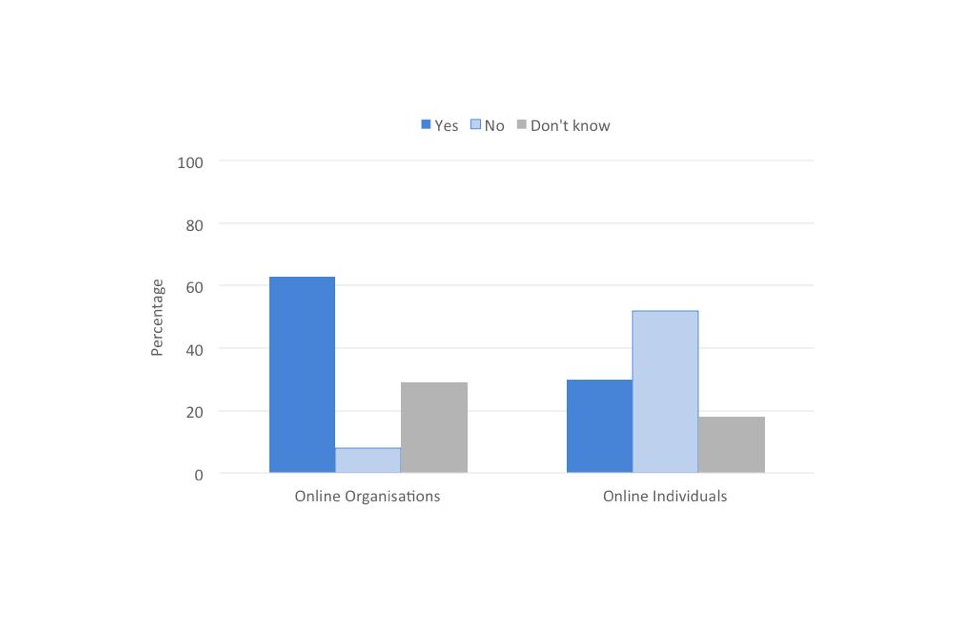

31. The White Paper written consultation included a specific question on whether legislative provision should be made for designated bodies to bring ‘super-complaints’ to the regulator for consideration, in specific and clearly evidenced circumstances. 88% of respondents online answered this question, of whom almost a third (32%) agreed with the proposal and almost half (49%) disagreed. The remainder (19%) said they did not know.

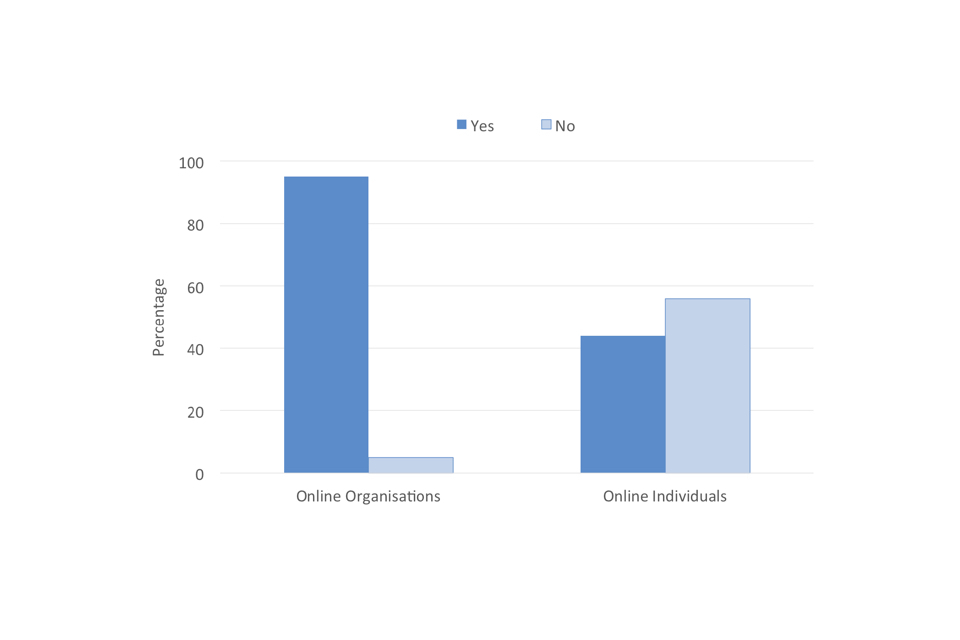

Figure 1: Should designated bodies be able to bring super complaints to the regulator in specific and clearly evidenced circumstances? Note: Online portal respondents only.

32. When considering organisational responses only, the proportion of respondents who agreed with the proposal rises to almost two-thirds (63%). The majority of stakeholders with whom we engaged also supported super-complaints. Many noted that super-complaints could prove particularly useful for tackling issues regarding legal harms, which cannot be addressed through law enforcement agency routes. Groups representing religious users felt that super-complaints could provide an effective means to address online discrimination and abuse. Disability and children’s advocacy groups, as well as some academics, were especially supportive, noting that super-complaints would allow for people who might not otherwise raise concerns or report issues to be heard and to have their concerns alerted to the regulator.

33. Several organisational respondents sought further clarity on how a super-complaints function would work in practice, and others (including regulators with super-complaint functions) noted that they are not normally intended to deliver direct redress to individuals. Women’s charities expressed support, but noted that other mechanisms may be necessary, for example in the case of low-level continuous harassment, which causes distress through its repetitiveness rather than its content. Some respondents also noted that a super-complaints function would only be effective if it was transparent and backed up by accountability mechanisms.

34. For those answering ‘yes’, we asked a further question on the circumstances under which super complaints should be admissible. Among organisational respondents, there was a high level of agreement that super-complaints should be permitted when there has been a large number of complaints or where there is evidence of clear abuses of company policy or standards. However , there was little consensus on what the criteria would look like in practice. There were relatively few individual responses to this question, as individuals responding online were only shown the question if they had responded ‘yes’ to part one. Of those individuals who did respond, there was little consensus, although in general individuals were more supportive than organisations of super-complaints regarding specific pieces of content.

35. We also consulted on other measures for users who wish to raise concerns about specific pieces of harmful content or activity, and/or breaches of the duty of care. Less than two fifths of respondents answered this question, and while the majority of responses expressed general disagreement with the proposals, a significant number expressed support and proposed options for users to raise concerns.

36. Many responses, particularly from organisations, argued for an independent review mechanism, such as an ombudsman, although no-one gave further detail on how this could work and some organisations raised concerns about the feasibility and desirability of an ombudsman. Other proposals included the possibility for automatic suspensions of reported posts on request by regulator or individuals.

37. While many individual respondents raised concerns about freedom of expression and how the envisaged user redress framework will be implemented in practice, there was a general consensus amongst organisations about the need for effective and accessible mechanisms for users to seek redress, and in favour of the measures we proposed.

Protecting users’ rights online

The White Paper stressed that users should receive timely, clear and transparent responses to their complaints of harmful content and committed to protecting their rights.

-

Companies covered by the regulator will be required to have an effective, proportionate, easy-to-access complaints process, allowing users to raise concerns about harmful content or activity, or that the company has breached its duty of care.

-

The regulator will set minimum standards for these processes, so that users will know how they can raise a complaint, how long it will take a company to investigate, and what response they can expect.

-

We do not envisage a role for the regulator itself in determining disputes between individuals and companies, but where users raise concerns with the regulator, it will be able to use this information as part of its consideration of whether a company may have breached duty of care.

38. The importance of ensuring that companies should have effective reporting mechanisms for harmful content, accessible to all users, was highlighted here. There was stronger support for the proposals for super-complaints from organisations responding than from individuals, with organisations highlighting that super-complaints could provide particularly useful for addressing legal-but-harmful content prevalent on some platforms. Broadly, respondents requested more support on how a super-complaints function could work, and how it could take into account accountability and transparency mechanisms. A number of respondents suggested a role for an independent review mechanism.

Transparency

39. As set out in the White Paper, the government has committed to giving the regulator the power to require annual transparency reports from companies in scope. These reports would, for example, outline the prevalence of harmful content on their platforms, and what measures are being taken to address these.

40. The regulator would publish these reports online to support users and parents in making informed decisions about internet use. The regulator would also have powers to require additional information from companies to inform its oversight or enforcement activity, and to establish requirements to disclose information.

41. Effective transparency reporting will help ensure that content removal is well-founded and freedom of expression is protected. In particular, increasing transparency around the reasons behind, and prevalence of, content removal may address concerns about some companies’ existing processes for removing content. Companies’ existing processes have in some cases been criticised for being opaque and hard to challenge.

42. In addition, as part of the transparency reporting framework, the regulator will encourage companies to share anonymised information with independent researchers, and ensure companies make relevant information available.

43. The government is committed to ensuring that conversations about this policy are ongoing, and that stakeholders are being engaged to mitigate concerns. In order to achieve this, we have recently established a multi-stakeholder Transparency Working Group chaired by the Minister for Digital and Broadband, which includes representation from all sides of the debate, including civil society members as well as industry. This group will feed into the government’s transparency report, which was announced in the Online Harms White Paper and which we intend to publish in the coming months.

44. Some stakeholders expressed concerns about a potential ‘one size fits all’ approach to transparency, and the material costs for companies associated with reporting. The regulatory framework is designed to be proportionate, and so will set out minimum thresholds that a company would need to meet before reporting requirements would apply. In line with the overarching principles of the regulatory framework, the reporting requirements that a company may have to comply with will also vary in proportion with the type of service that is being provided, and the risk factors involved.

The government has committed to Annual Transparency Reporting. Beyond the measures set out in this White Paper, should the government do more to build a culture of transparency, trust and accountability across industry and, if so, what?

Engagement

45. Transparency has been a key theme discussed with a range of organisations and user groups. A wide variety of stakeholders, including rights groups and tech companies, supported such measures and agreed that increased transparency is needed. Children’s charities, LGBT+ organisations and religious groups especially welcomed the framework’s focus on transparency - both in terms of reporting processes and moderation practices for the purpose of holding companies accountable to their own standards. Freedom of expression groups were similarly supportive of greater transparency and accountability but were keen to emphasise that transparency reporting should promote users’ rights and should contain information about how companies uphold users’ right to freedom of expression online.

46. The importance of proportionality in relation to the transparency requirements emerged as a key point. Furthermore, a number of companies noted that, given the variation between companies, a ‘one size fits all approach’ was unlikely to be effective.

Written consultation

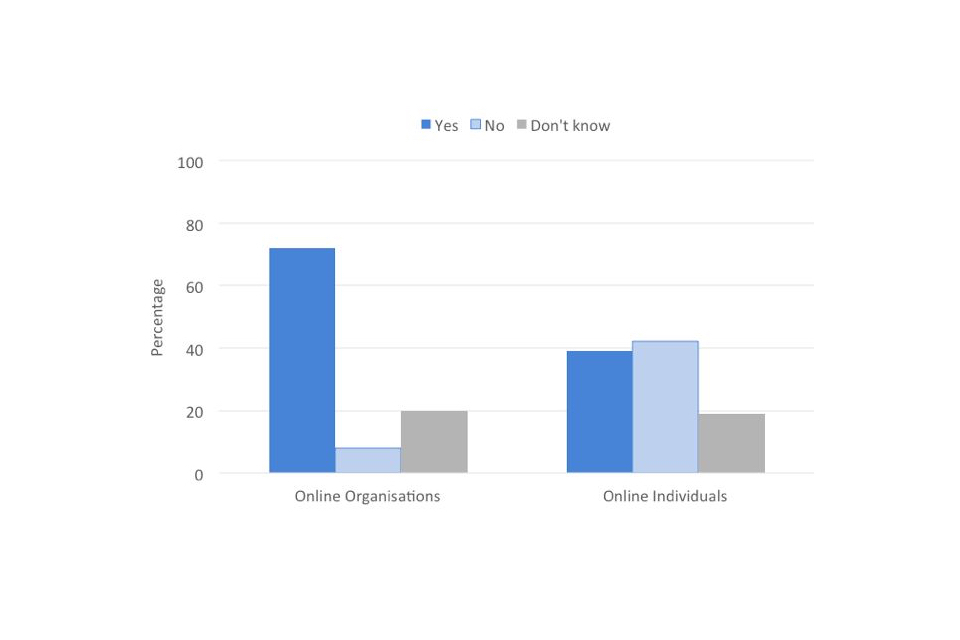

47. The written consultation asked people whether, beyond the measures set out in the White Paper, the government should do more to build a culture of transparency, trust and accountability across industry and, if so, what? 90% of online respondents answered this closed question. Of these, there was little difference between those who agreed the government should do more and those who disagreed (41% and 39% respectively). Almost a fifth (19%) said they didn’t know.

Figure 2: The government has committed to Annual Transparency Reporting. Beyond the measures set out in this White Paper, should the government do more to build a culture of transparency, trust and accountability across industry? Note: Online portal respondents only.

48. When broken down, the responses from organisations and members of the public differ, with 72% of organisations agreeing that the government should do more, compared to only 39% of individuals.

49. Those who agreed that the government should do more provided answers for how and what measures could go beyond the White Paper proposals to increase transparency. A large proportion of responses suggested this could be done through requiring increased clarity and detail of reporting. Many responses also suggested that engagement with international partners would help to promote a culture of transparency and trust.

50. In particular, amongst organisations, civil society groups were considerably more supportive of the proposals advanced in the White Paper around transparency, which they saw as a crucial mechanism to increase companies’ accountability and foster positive relationships with the regulator. While the technology sector was also overall broadly supportive of transparency, there was less consensus about the format the reporting should take. Some small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) highlighted resource and capability challenges associated with collecting or reporting certain types of information. Other respondents, including dating sites and retailers, echoed this concern, stating that transparency reporting might be overly onerous on them should it require significant re-engineering of their given product or service if it had not been designed to gather certain types of data. Generally, respondents expressed support for flexibility over rigid guidelines, although, at the same time, some did acknowledge the benefit of having structure and direction from the regulator.

51. Many responses also explicitly mentioned that reporting should be qualitative, not just quantitative, avoiding a one size fits all approach, and that the data reported should be clear and meaningful. Respondents also asked that transparency reports be written in plain English and made accessible to the public.

52. Responses from both organisations and individuals contained specific proposals for how to increase transparency. These proposals included requiring social media companies to show how safety features are being improved in line with the regulator’s recommendations. Other suggestions included: increased transparency from social media platforms on content moderation decisions, involving the public in formulating online harms policy and encouraging social media companies to promote their own transparency reports to their users.

53. Responses also suggested specific focal points and metrics for the transparency report, such as an independent review of AI/algorithms, an attention to ‘addiction by design,’ a specific separate focus on child safety, advertising, and finally expert medical advice.

54. Additionally, although not directly relevant to the question, many responses took the opportunity to suggest an increase in government transparency and that any future regulator should also be transparent.

55. Many of those who disagreed that the government should do more asserted that government should not be involved or should be less involved. Other responses attested that it was not possible to hold the companies in scope to account.

56. Overall, responses to this question varied, expressing suggestions for what government should do to increase transparency, trust and accountability across industry, as well as some respondents expressing concerns with an increasing government role.

Enforcement

57. The regulator will have a range of enforcement powers to take action against companies that fail to fulfil their duty of care. This will drive rapid remedial action, and ensure that non-compliance faces serious consequences. The enforcement powers referenced are the power to issue warnings, notices and substantial fines. The White Paper also included proposals for business disruption measures - including potential for business disruption, Internet Service provider (ISP) blocking, senior management liability.

Should the regulator be empowered to i) disrupt business activities, or ii) undertake ISP blocking, or iii) implement a regime for senior management liability? What, if any, further powers should be available to the regulator?

Engagement

58. Throughout our engagement, industry representatives ranging from larger tech firms to start-up companies expressed a measure of support for the tiered enforcement approach set out in the White Paper. At the same time, they asked for further clarity on what would be considered appropriate points for intervention and escalation, as well as what limits could be considered reasonable for sanctions in order for these not to represent an unacceptable business risk. Internet service provider (ISP) blocking represented the main area of concern across discussions. Industry stated in principle support in some cases (e.g. when websites are set up for solely unlawful purposes), but argued that it would need to be mandated only as a last resort following due process and underpinned by the legal framework.

59. Senior manager liability emerged as an area of concern. Discussions with industry highlighted the risk of potential negative impacts on the attractiveness of the UK tech sector. Further concerns emerged that this approach may unduly penalise individuals for content often originating from other third-parties who would not be adversely affected by the sanctions, unless the regime proposed is able to account for these. With regard to further powers, industry representatives felt that the regulator should fulfill a supervisory function and look to support compliance in the first instance.

60. Civil society groups overall expressed support for firm enforcement actions, in cases of non-compliance. Nevertheless, rights organisations expressed concerns about risks to freedom of expression and the potential impact of censorship associated with enforcement powers.

Written consultation

61. The written consultation specifically asked whether the regulator should be empowered to:

-

disrupt business activities

-

undertake ISP blocking

-

implement a regime for senior management liability

62. We also asked if any further powers should be available to the regulator.

63. This question did not receive a high response rate. Across all categories, the majority of respondents highlighted concerns that excessive enforcement could have a detrimental effect on both business and personal freedoms - and risk that measures could incentivise companies to over-block user-generated content to avoid penalties.

64. Analysis of the responses of organisations and individuals showed a large difference in levels of support - with a significantly larger portion of concerns coming from the individual respondents, while organisations generally supported the proposals. This result is not surprising given the apprehension amongst many individual respondents about how the proposals would impact usability and personal freedoms. The creative industries, sport sector, local government, law enforcement organisations and children’s charities particularly expressed broad support for the majority of enforcement mechanisms listed in the White Paper.

65. Respondents who supported the proposals took the view that the regulator should have robust enforcement powers that are used fairly and proportionately.

66. Respondents expressing support for the business disruption proposals highlighted the importance of the need to ensure these powers are used proportionately and should be an escalation from demonstrable non-compliance and prior warnings being issued. This view was also expressed for senior management liability. Many who welcomed it as a measure to hold individuals to account felt it should only be used after demonstrable non-compliance and the failure of previous measures. For ISP blocking the common view was that it be used as a last resort. A small number of respondents suggested additional powers, including further enforcement measures against companies such as temporary content takedowns, and sanctions for failing to duly protect freedom of expression.

67. Organisations raised other points of criticism. Rights groups expressed concerns that the proposed enforcement approach may be disproportionately punitive, and the regulator would need to demonstrate it had met the proportionality test for freedom of expression under human rights law. This was a particular concern for ISP blocking.

68. Although many industry members noted their opposition to ISP blocking in general, they acknowledged that there may be circumstances in which the exercise of such powers would be appropriate. Practically, industry requested clear guidance and an agreed process for notifying operators when websites are required to be blocked (or reinstated), and clarification on the anticipated volume of websites that would be in scope.

69. From a technical perspective, Internet Service Providers (ISPs) also noted the importance of developing the future regulation with reference to wider technical developments such as encryption, which might undermine the effectiveness of website blocking. Industry requested a transition period to adjust to or implement the new regulations without the threat of severe sanctions. Larger tech companies highlighted the implementation challenges they may have due to the size and complexity of their systems.

70. In summary, while civil society groups overall expressed support for firm enforcement actions, the proposals remain contentious for industry, freedom of expression groups, and members of the public. For the implementation of the proposed measures, respondents expressed a preference for the regulator to begin its operations by supervising companies and supporting compliance through advice, and that any further enforcement measures should be used proportionately and following a clear process.

Nominated Representative

71. Noting the particularly serious nature of some of the harms in scope and the global nature of many online services, the White Paper proposed that the regulator should have the power to ensure that action can be taken against companies without a legal presence in the UK. It sets out the possibility of a requirement for companies to nominate a UK or EEA-based representative for these purposes, similar to the concept in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Should the regulator have the power to require a company based outside the UK or EEA to appoint a nominated representative in the UK or EEA in certain circumstances?

Engagement

72. Throughout our engagement with industry, concerns of impracticality and challenges of implementation emerged as a key theme, with SMEs arguing that this could be excessively burdensome for them. Some proposed other ideas, such as the establishment of an endorsement system for companies demonstrating best practice.

Written consultation

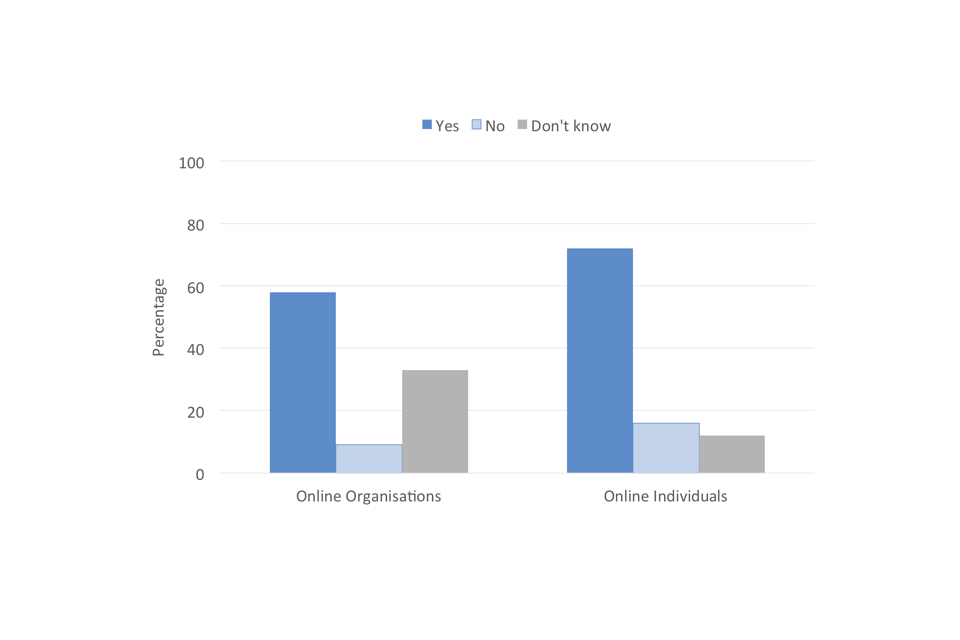

73. Less than half of online respondents answered this question (48%), of which almost two thirds (62%) responded“no”, followed by “yes” (27%) and “don’t know” (11%). Respondents to the written consultation generally disagreed that the regulator should have the power to require a company based outside the UK or EEA to appoint a nominated UK or EEA representative.

Figure 3: Should the regulator have the power to require a company based outside the UK or EEA to appoint a nominated representative in the UK or EEA in certain circumstances? Note: Online portal respondents only.