Consultation on the English portion of dormant assets funding

Updated 7 March 2023

Applies to England

Ministerial foreword

Over a decade ago, the UK set up its globally renowned Dormant Assets Scheme, leading the charge on putting assets lying idle to good use. Since then, £892 million has been released to address some of the country’s most pressing social and environmental challenges – including breaking down barriers to work for disadvantaged young people, tackling problem debt, and creating the world’s first social investment wholesaler.

This year marks the beginning of an exciting new era with the Scheme’s expansion, providing the opportunity to support industry’s work to reunite more people with their assets and potentially unlock hundreds of millions more for good causes. The Dormant Assets Act 2022 brings an estimated £3.7 billion of additional assets sitting idle into scope, drives efforts to reunite £2 billion of this with its rightful owners, and is set to make around £880 million more available for social or environmental causes across the UK over time.

In the unprecedented context of the country’s recovery from Covid-19 and its wide-ranging implications for social and environmental priorities, now is the right time to look at how the Scheme can deliver the greatest impact. The consultation will determine what the broad purposes of the English portion should be and we want to hear what matters most to you. This includes local communities, current and potential participants, civil society organisations, and any interested individuals. While we invite specific views on four causes – youth, financial inclusion, social investment, and community wealth funds – we also want to hear your suggestions for any other social or environmental causes that we should consider.

The Scheme is a fantastic example of what can be achieved when public, private, and civil society sectors come together to form innovative partnerships. Its success to date is testament to the commitment and drive of all those in the Scheme’s ecosystem: from industry participants to Reclaim Fund Ltd; The National Lottery Community Fund and The Oversight Trust; to the four organisations that have distributed the money to date. The Scheme is making a real difference to people’s lives in communities across England. We look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can secure the long-term impact of its expansion that addresses some of the country’s greatest challenges.

Nadine Dorries MP

Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

Nigel Huddleston MP

Minister for Sport, Tourism, Heritage and Civil Society

Key terms and acronyms

Key terms

| 2008 Act | The Dormant Bank and Building Society Accounts Act 2008 |

| 2022 Act | The Dormant Assets Act 2022 |

| Cause | The term ‘cause’ is used to refer to the broad purposes for which, or the kinds of person to which, a distribution of dormant assets money for meeting English expenditure may be made. Currently, this is youth, financial inclusion, and social investment wholesalers |

| Community wealth fund (CWF) | A fund which gives long-term financial support (whether directly or indirectly) for the provision of local amenities or other social infrastructure |

| Current spend organisations | ‘Current spend organisations’ refers to the four independent organisations that have received dormant assets funding in England to date, and are overseen by The Oversight Trust. These are: Big Society Capital, Access – the Foundation for Social Investment, Fair4All Finance, and Youth Futures Foundation |

| Dormant asset | A dormant asset is an identifiable and attributable item, valued as a monetary amount or able to be valued as such, which a participant is unable to reunite with its owner despite reasonable efforts. Section 1(6) of the 2022 Act summarises the dormant assets that are in scope of the Scheme currently. |

| Financial inclusion initiatives | Expenditure on or connected with the development of individuals’ ability to manage their finances, or the improvement of access to personal financial services |

| Participant | The term ‘participant’ is used to refer to firms, companies, and other organisations managing assets that might participate in the Scheme |

| Scheme | The UK’s Dormant Assets Scheme |

| Social investment wholesaler | A body that exists to assist or enable other bodies to give financial or other support to organisations that exist wholly or mainly to provide benefits for society or the environment |

| Youth initiatives | Expenditure on or connected with the provision of services, facilities, or opportunities to meet the needs of young people |

Acronyms

-

BSC: Big Society Capital

-

CWF: Community wealth fund

-

DCMS: Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport

-

F4AF: Fair4All Finance

-

NEET: Not in Education, Employment, or Training

-

RFL: Reclaim Fund Ltd

-

TNLCF: The National Lottery Community Fund

-

YFF: Youth Futures Foundation

1. Background

1.1 Introduction

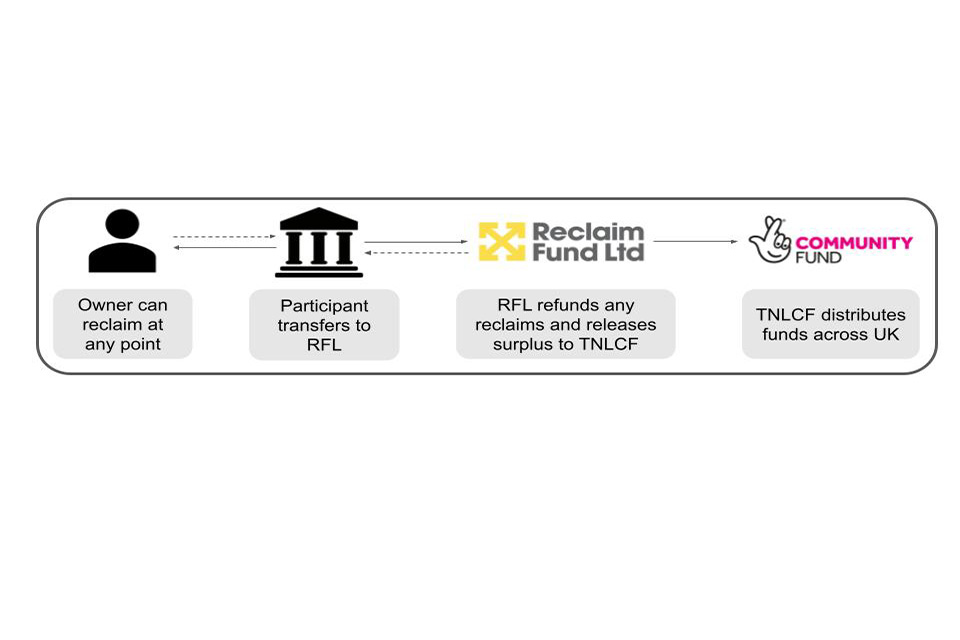

The UK’s Dormant Assets Scheme (“the Scheme”) is led by industry and backed by the government. It enables responsible businesses to voluntarily channel funds from dormant assets to good causes, while ensuring owners’ rights are protected. The Scheme responds to the imperative to put funds lying idle to good use, distributing hundreds of millions of pounds to social and environmental initiatives that would otherwise be gathering dust in forgotten accounts. This is particularly important in the context of recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic and pressures on the cost of living.

To date, Reclaim Fund Ltd (RFL), the Scheme’s administrator, has received over £1.6 billion of dormant assets. The Scheme has unlocked £892 million of this for social and environmental causes across the UK, with its expansion enabling a potential £880 million more to be released over time.

RFL determines how much it must prudently retain in order to meet any reclaims from rightful owners, and distributes the surplus annually to The National Lottery Community Fund (TNLCF). TNLCF in turn makes the money available for good causes across the UK – at the direction of the devolved administrations for their respective portions, and the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) for England.

At the Scheme’s inception more than a decade ago, restrictions were set that mean funding can only go to three broad causes in England:

-

the provision of services, facilities, or opportunities to meet the needs of young people (“youth”)

-

the development of individuals’ ability to manage their finances or the improvement of access to personal financial services (“financial inclusion”)

-

funding for social investment wholesalers to support civil society organisations (“social investment”)

To date in England, the Scheme has channelled £110 million to breaking down barriers to employment for disadvantaged young people; £100 million to increasing access to fair and affordable financial products and services for vulnerable individuals; and £485 million of urgently-needed investment for charities and social enterprises, particularly those operating in more deprived communities.

This consultation seeks the public’s and industry participants’ views on what the broad purposes of the English portion should be going forwards. England receives 83.9% of dormant assets funding, meaning around £738 million of the £880 million eventually expected to flow through from the Scheme’s expansion will be apportioned for England.

It is important to note that this money will not immediately become available and is expected to take several years to be released through to TNLCF. For example, it took five years for the first £400 million of the English portion to be unlocked through the Scheme.

1.2 Principles of the Scheme

The Scheme is underpinned by the following principles:

-

Reunification first: participants’ first priority is to trace and reunite people with their assets.

-

Full restitution: asset owners are able, at any point, to reclaim the amount that would have been due to them had a transfer into the Scheme not occurred.

-

Voluntary participation: potential industry participants can choose whether to contribute to the Scheme, when, and to what extent.

Dormant assets funding across the UK must be used for environmental or social purposes. It is distributed in line with the principle of additionality: the money cannot be used to undercut or substitute government spending, but rather must be distributed to projects that are unlikely to be funded centrally. Annex B describes our current policy and practice on additionality in more detail.

In England, dormant assets distributions have focused on driving systems-wide change to entrenched social and environmental issues. This big-picture approach is a key aspect of the Scheme’s success to date, and one we wish to ensure continues. Chapter 2 highlights this and other criteria that we will use when assessing responses to this consultation.

1.3 Scope of consultation

This consultation seeks views on the broad social or environmental purposes of the English portion of dormant assets funding. In order to understand its scope, it may be helpful to note the context behind it and anticipated next steps. The figure below outlines four pillars that are relevant to deploying funding in England:

| 1. Primary legislation |

Social and/or environmental focus Primary legislation requires all dormant assets funding to be distributed to social or environmental initiatives. Distributions are made in line with the additionality principle. |

| 2. Secondary legislation |

Prescribed causes Secondary legislation can prescribe the social and/or environmental causes that the English portion is able to support. The government must consult on this before secondary legislation can be made. |

| 3. Policy directions |

Broad purposes for a release of funds DCMS issues policy directions to TNLCF for the broad purposes – within the boundaries of any prescribed causes – for a specific release of funds in England. |

| 4. Distribution |

Specific distribution decisions Responsibility for granular decision-making lies with TNLCF and/or the organisation(s) delivering initiatives. There is therefore no central government bidding process for accessing dormant assets funding. |

This consultation informs the second pillar: it invites public input on the broad social or environmental purposes for dormant assets funding in England. Responses will help to inform the government’s decision on what causes (if any) should be prescribed in future secondary legislation. As such, the scope of this consultation is set at a correspondingly high level. It therefore does not consider any specific release of money and is not a bidding process for organisations to access funding. These decisions can only be taken once we have determined what overarching purposes the English portion will have.

1.4 Structure of consultation

Chapter 2 outlines the criteria that the government will use when assessing the relative merits of any social and environmental causes proposed. This ensures that the government’s decision is transparent, collaborative, and informed by evidence, so that the Scheme continues to have the greatest impact it can. Chapter 2 therefore lays the foundation for the chapters that follow.

The government recognises the broad support the Scheme has received since its inception, most notably through the excellent voluntary participation rate from industry. Accordingly, Chapters 3–5 invite views on the current three causes – youth, financial inclusion, and social investment – and whether they should continue to benefit from the Scheme’s support.

While the government is proud of this impact, we also recognise that there may be other social or environmental causes that are worth considering. One of these is the community wealth fund (CWF) proposal: where long-term funding for community infrastructure is distributed to more deprived areas. Chapter 6 seeks views on this. Chapter 7 then invites suggestions for any other social or environmental causes that respondents believe should be considered.

In addition to considering whether to name specific purposes in secondary legislation, the Secretary of State may also consider whether to make an order that provides that there are to be no specific purposes. In that scenario, any dormant assets funding in England could be distributed for any social or environmental purpose (subject to complying with any policy directions given to TNLCF by the Secretary of State). Question 30 invites views on this.

2. Criteria for assessing causes

2.1 Introduction

The government is proud of the success of the Scheme to date and, with its expansion set to release approximately £738 million in England over time, we are committed to ensuring this money is put to effective and efficient use. To lay the foundations for this, we have created a set of criteria that we will use when considering the social and environmental causes proposed through this consultation. This chapter sets out what we consider to be essential and desirable characteristics, which we encourage respondents to take into account when proposing broad causes.

The government is keen to ensure that this consultation enables everyone’s voice to be heard and ideas to be considered on the basis of their merit. All responses to this consultation will be considered. While the relative frequency of any cause being proposed will be noted, this alone will not determine which one(s) are chosen.

2.2 Essential criteria

We consider the following eight criteria to be essential features of any future cause chosen for the English portion:

-

Any cause must constitute a social or environmental initiative. This requirement is set out in primary legislation. Examples of what we would consider to be ineligible include political activism, activities of an exclusively religious nature, paid for lobbying, and gifts.

-

There must be sufficient scope to fund initiatives that would not otherwise be funded by central government. This is known as the principle of additionality, and its definition is set out in primary legislation. The principle means that allocating dormant assets funding to a particular cause, community, or organisation should not result in the reduction of government funding to that entity. This does not mean that dormant assets funding cannot operate in the same sphere as central government. However, there must be evidence of how it could be additional (and preferably complementary) to central funding, not a substitution. Annex B provides more detail on our policy on additionality.

-

A portion of the £738 million must have a meaningful impact. Industry stakeholders have estimated that the expansion of the Scheme will unlock £880 million for good causes over time. This would translate to £738 million for England. There must be evidence that the scale of the problem could be addressed within a portion of this overall quantum.

-

The funds must seek to make sustained, high-impact change. Building on the previous criteria, we want to ensure that piecemeal interventions are not the focus of this funding as this would dilute its impact. Rather, the English portion should be used to fund long-term initiatives capable of moving the dial on entrenched social or environmental issues.

-

There must be an ability to attribute and measure the impact achieved. Being able to measure the impact of dormant assets funding is essential to ensuring the transparency of the Scheme, as well as its success. We would expect to see tangible progress made within five years.

-

It must align with key government policy priorities, including securing voluntary industry support. Examples include:

• aligning to and supporting net zero goals, including those set out in the UK government’s net zero strategy. For instance, projects are encouraged to demonstrate low or zero carbon best practice; adopt and support innovative clean tech; and/or support the growth of green skills and sustainable supply chains;

• contributing to the wider government priority of levelling up left-behind communities, as outlined in the Levelling Up White Paper; and

• securing the support of the Scheme’s voluntary industry participants, who have been – and will continue to be – crucial to its success. -

There must be scope for nationwide impact across England. The impact of the funding should be most felt across the most disadvantaged areas in England, and not be concentrated in one particular region.

-

Dormant assets funding must be appropriate for the cause. It should be capable of weathering the highly uncertain funding flows and timings associated with this unique type of public money.

2.3 Desirable criteria

In addition to the eight essential criteria, the government will be mindful of the following three desirable characteristics of any social or environmental cause:

-

Contribute positively to good community relations and integration. The ability to promote good community relations and advance integration would be considered favourably.

-

The ability to leverage in other sources of funding is desirable. The ability to corral other funders into the same space supports the amplification of the Scheme’s impact.

-

Using existing organisations and/or systems of delivery, governance, and accountability is preferable. There is a value for money argument for utilising existing structures, where possible without risking impact, rather than establishing new ones. While this consultation does not ask for input on specific distribution mechanisms, this is something the government will take into consideration when assessing the relative merits of proposals.

3. Youth

| Chapter 3 seeks views on one of the three causes currently supported by the Scheme in England: the provision of services, facilities, or opportunities to meet the needs of young people (referred to as “youth” for simplicity). |

3.1 Introduction

The 2008 Act currently defines three causes to which the English portion of dormant assets can be distributed (see Chapter 1.1). The first of these is the provision of services, facilities, or opportunities to meet the needs of young people (referred to as “youth” for simplicity). This definition is sufficiently broad to enable TNLCF to distribute funding to a wide range of initiatives, securing longevity of impact and responding to the most pressing issues of the day. This is subject to meeting the additionality principle: there are a number of areas relating to young people that the government has a statutory responsibility to fund centrally, such as the school system and care system. These are areas that dormant assets clearly could not and should not be used.

The following sections provide more information on how funding has been spent to date on this cause and future opportunities for impact, to inform your response to the question of whether youth should remain a cause in England.

3.2 Impact to date

In 2017, DCMS led an engagement exercise with the youth sector in England to explore the possibility of investing dormant assets funds to tackle the issue of youth unemployment. This was in response to the Race Disparity Audit, which highlighted a clear inequality of opportunity for young people from different backgrounds or growing up in different parts of England.[footnote 1] This exercise concluded that a new organisation would be best placed to forge partnerships across businesses, education, and youth organisations and to take a strategic, long-term, and evidence-based approach in response to these issues.

Youth Futures Foundation (YFF) was established as an independent organisation to undertake this work, and began operating in December 2019. YFF has since been allocated £110 million of dormant assets to fund a range of programmes. It has invested £20.8 million in 153 civil society organisations to engage over 17,000 young people across all regions in England.[footnote 2] This includes the £16 million Connected Futures Fund designed to join up services for young people at a local level in areas with the highest NEET (not in education, employment, or training) rates and wider indicators of deprivation. Alongside targeted investments to support the delivery of local services, YFF has been accredited as a What Works Centre in the UK. Such centres aim to improve the way that the government and other public sector organisations create, share, and use high-quality evidence in decision-making.

To support these aims, YFF works to:

-

Establish a strong evidence base of what works and actively share knowledge to achieve systemic change, including by:

• Launching a Youth Employment Evidence and Gap Map, summarising 658 studies in the world’s largest evidence resource on improving youth skills, employment, and job quality.

• Funding the largest ever range of youth employment evaluations in England, investing £13.6m in 25 organisations. -

Develop partnerships to build strong and innovative links between the public, private, and voluntary sector at the local and national level – including by:

• Mobilising the youth employment sector across the UK through co-founding the Youth Employment Group (YEG), bringing together over 300 youth employment experts to advocate for full and inclusive employment for young people.

• Developing evidence for employers through two best practice guides to recruiting and retaining young people in employment, reaching over 250,000 employers so far. -

Lead new research, data, and policy analysis to understand barriers and solutions to support specific groups of ethnic minorities into quality education, training, and employment – including by:

• Establishing and co-chairing the Ethnic Disparities Sub-group of the YEG, which has 40+ members, including researchers, academics, practitioners and policymakers.

• Funding 55 organisations focused on supporting young people belonging to an ethnic minority.

Youth case study: Friends, Families and Travellers

Young people from Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller communities face some of the greatest barriers to employment of any ethnic group in the UK. Educational attainment is extremely low: 60% have no qualifications and by year 11, and 50% have dropped out. To compound these problems, young people frequently have low self-confidence, limited aspirations, and little knowledge of life outside their family and site.

Friends, Families and Travellers is a national charity that supports people from Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller backgrounds. It received a £78,035 grant from the Inspiring Futures Fund for a programme of employability support activities for young people. The grant will support 252 people aged 10–24 who live in Sussex.

The programme includes a focus on digital skills training to close the educational and employability gap for these young people. The project also aims to improve essential employability skills such as leadership, communication, and patience.

3.3 Potential opportunities for further impact

The pandemic had an unprecedented impact on young people. Anxiety levels are at a 12-year high;[footnote 3] young people saw the largest increase in unemployment during COVID;[footnote 4] while a year of disrupted learning widened the attainment gap.[footnote 5] 66% of 16-19 year olds report worrying about their future, with the most disadvantaged hit the hardest.[footnote 6]

Future dormant asset funds could have significant impact on the youth sector by maximising the Scheme’s impact to date or addressing key gaps in provisions. Opportunities include:

1. Amplifying the Scheme’s impact to date on tackling youth unemployment:

-

Maximising the impact of the Scheme’s existing £110 million investment in preventing youth unemployment, future funds could focus on continuing to support early intervention, preventing young people from becoming NEET in the first place, resulting in significant savings to public finances.[footnote 7]

-

Another potential opportunity is strengthening the networks and partnerships between the youth sector and employers to secure sustained behavioural changes around recruitment, retention, and progression. This is vital to supporting more young people into fulfilling and long-term employment.

2. Providing more local clubs and activities for young people:

- In a recent survey by the Children’s Commissioner, one of the biggest concerns raised by young people, alongside mental health, is having something to do in their local area.[footnote 8] Evidence shows participation in youth services and programmes leads directly to positive outcomes for young people. This includes the enhancement of life skills and character traits;[footnote 9] better mental health and narrower mental inequalities later in life;[footnote 10] and increased confidence, resilience, and self-belief.[footnote 11] Out-of-school youth provisions can also deliver significant indirect upstream benefits to society, including prevention of negative outcomes that will require more costly intervention later on, such as mental health issues,[footnote 12] becoming NEET,[footnote 13] and serious youth violence.[footnote 14]

2. Expanding local youth partnerships:

- These partnerships bring together groups such as the local council, voluntary sector, businesses, and young people to decide how best to support young people to thrive in their local area. They have been shown to bring more investment into youth services and provide long-term support to deliver on young people’s priorities in a local area. Well suited for dormant assets funding, they work best when there is a mix of public, private, and voluntary sector organisations involved.

4. Supporting the outward bounds sector:

- Young people, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds benefit hugely from adventures away from home, interacting with nature and their peers in new and challenging situations.[footnote 15] These experiences are often only achieved through access to ‘outward bounds’ centres across England. The sector has seen a number of sites close over the pandemic and dormant assets funding could be used to help secure existing sites or reopen some that have closed. Funding could also be used to subsidise outward bounds places for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds or vulnerable groups.

3.4 Consequences of removing youth as a cause

Removing support for young people now could compound the considerable negative impacts of the pandemic, especially for the most disadvantaged. In February this year, the government published its Youth Review,[footnote 16] which announced the Youth Guarantee. Backed by £560 million of central funding, it committed that by 2025 every young person will have access to regular clubs and activities, adventures away from home, and volunteering opportunities. Removing youth as a cause could inhibit opportunities for dormant assets funding to support complementary youth initiatives (in accordance with the additionality principle) to accelerate and expand on these ambitions at a vital time.

Equally, it could weaken the potential benefits from the £110 million investment the Scheme has already made in preventing youth unemployment in England. Building an understanding of the barriers to youth employment and what works to tackle these requires long-term investment. If youth was removed as a cause, it may result in a missed opportunity to translate the evidence gathered since 2019 through the existing funding into systemic change across the youth employment ecosystem.

4. Financial inclusion

| Chapter 4 seeks views on one of the three causes currently supported by the Scheme in England: the development of individuals’ ability to manage their finances or the improvement of access to personal financial services (referred to as “financial inclusion” for simplicity). |

4.1 Introduction

The 2008 Act currently defines three causes to which the English portion of dormant assets can be distributed (see Chapter 1.1). The second of these is commonly referred to as “financial inclusion”. Financial inclusion means that individuals, regardless of their background or income, should have access to appropriate and affordable financial products and services that enable them to manage their finances day to day, withstand life shocks, and thrive. Section 4.2 below explains how dormant assets funding to date has been targeted towards increasing the accessibility of affordable finance.

The following sections provide more information on how funding has been spent to date on this cause and future opportunities for impact, to inform your response to the question of whether financial inclusion should remain a cause in England.

4.2 Impact to date

In 2017, DCMS led an engagement exercise with the financial inclusion sector to explore the possibility of investing dormant assets funds to tackle financial exclusion. A user-centred, cross-sector engagement followed, which concluded that systemic market change was needed in order to help vulnerable people meet their financial needs. £55 million of dormant assets funding was committed to increase the use of fair, affordable, and appropriate financial products and services that boost savings, increase protection against shocks, and smooth incomes.[footnote 17] It was agreed that a new organisation was best placed to deliver this, and Fair4All Finance (F4AF) was established as an independent organisation in 2019.

Since then, F4AF has been allocated £100 million from the Scheme. It has used this to invest in and work with providers who serve some of the most deprived areas of England to get affordable credit to those who need it most.[footnote 18] Overall affordable credit provision in the market has increased by £48 million, of which £19.7 million can be directly attributed to F4AF investment. This has resulted in 150,000 customers being lent a total of £150 million through F4AF’s funded providers, with estimated interest savings for these customers of £50–75 million compared to their next realistic alternatives.[footnote 19] The key objectives of the funding to date have been to:

1. Scale the provision of fair and affordable credit, investing in providers to build and prove scalable and sustainable models:

-

£28 million of funding has been committed or deployed into community finance providers, such as credit unions and community development financial institutions (CDFIs). This is working towards a five-year target to triple the provision of affordable credit from £300 million to £900 million a year.

-

F4AF’s investment and support for community finance providers has helped influence social investors to extend or increase their investment in the sector, with circa £20 million currently committed.

2. Partner with mainstream financial services, building the evidence base for how they can serve excluded customers and what longer-term subsidy and regulation may be needed. F4AF has leveraged an additional £8 million to support research and market development, most notably:

-

Funding from JP Morgan, HM Treasury, and Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland governments for a pilot of a No-Interest Loan Scheme (NILS), targeted at consumers in vulnerable circumstances.[footnote 20]

-

NatWest funding for research into the financial exclusion of people from ethnic minorities.[footnote 21]

-

Esmée Fairbairn Foundation funding for a Theory of Change for affordable credit provision.

3. Support the development of new products and improve service design, partnering with others to address market gaps and failures with inclusive products:

-

F4AF has launched a new technology fund to invest in technology infrastructure that will support affordable credit providers to scale and invest in new platforms.

-

It has commissioned brand awareness work for the whole sector, which will support lenders to drive marketing efficiencies across community finance providers.

Financial inclusion case study: Fair For You

F4AF has provided £5 million of dormant assets funding to support the growth of Coventry-based Fair For You, which provides affordable loans to tackle furniture poverty across the UK. They focus on lending for essential household items such as appliances and beds.

From its establishment in 2015 to 2020, Fair For You provided £13.4 million in affordable loans to almost 40,000 customers.[footnote 22] During this time, Fair for You generated £50 million of social value and helped move 71% of its customers away from high-cost credit. This has meant that 60% of Fair for You customers were better able to pay their rent, Council Tax, and other household bills as a result. It is estimated that over £2 million has also been saved from reduced use of NHS services, due to the positive health benefits of having essential home items.

4.3 Potential opportunities for further impact

The combination of the pandemic, market changes, and cost of living pressures have significantly increased the scale of challenges around financial exclusion. The number of people with low financial resilience increased by nearly 30% to 14 million during the pandemic[footnote 23] and around 8.5 million adults in the UK are classed as over-indebted.[footnote 24] The pressures of the pandemic also intensified problem debt for people on the lowest incomes: some estimates suggest that between March 2020 and March 2021, 11 million people accumulated £25 billion of debt and arrears for essentials.[footnote 25] Many do not have the resilience to withstand everyday financial shocks, with one in five adults having less than £100 in savings.[footnote 26] Projections indicate that the cost of living pressures will push more people into financially vulnerable circumstances: it is estimated that families will pay an additional £1,200 a year from April 2022. These increases that are likely to have a disproportionate impact on low income households,[footnote 27] and people on the lowest incomes are more likely to need to access borrowing or additional support to get by.[footnote 28]

This evidence demonstrates the growing need for fair and affordable finance to manage income shocks and build financial resilience. As needs grow, so does the gap in appropriate products and services for these customers. Recent estimates place the number of people who may be using loan sharks at over 1 million,[footnote 29] and the Financial Conduct Authority recorded significant growth in the number of people borrowing from their family and friends.[footnote 30] In response to these issues, future dormant asset funds could have significant impact on the financial inclusion sector by addressing key market gaps:

1. Scale up affordable credit:

- The affordable credit sector is currently much smaller than customer demand.[footnote 31] Customers considered to be high risk were previously able to use high-cost credit, but over £1 billion has been lost from this market in the last three years.[footnote 32] Scaling affordable credit is the biggest opportunity for systems-wide change in financial inclusion, where dormant assets funding could address the need to grow this market to support millions of people. Further investment into existing affordable providers, and capital to enable new ones, would support creating a market to serve customers appropriately over the long-term.

2. Scale up pilots on NILS and consolidation loans:

- Alongside the NILS pilot, Fair4All Finance is also piloting a fair and affordable consolidation loan scheme. This is designed to reduce costs and complexity for people struggling with multiple debts. Depending on the outcomes of the pilots, dormant assets could provide the necessary capital to scale these schemes and reach more people in need.

3. Tackling appliance poverty:

- Over 2 million households live in appliance poverty where they do not own an essential white goods such as a fridge, cooker, or washing machine, costing them over £1,000 a year.[footnote 33] Dormant assets funding could be used to address appliance poverty through an affordable finance pilot to get appliances to those who cannot afford them in social housing and private rented accommodation. This would reduce living costs and has proven wellbeing benefits.[footnote 34]

4. Building financial resilience through accessible insurance:

- Further funding could bring the capital required to address systemic gaps in insurance provision across home insurance, motor, and life shock protection. This would help address issues such as the one in four households in the UK without contents insurance and the significant poverty premium paid on insurance products.[footnote 35]

4.4 Consequences of removing financial inclusion as a cause

The areas listed above need significant funding to reach the scale required by customers and drive system-wide market change. So far, F4AF has deployed £28 million into affordable credit from dormant assets funding. At this time, dormant assets funding is the only capital available for scaling this market in England, particularly given that commercial investors have not been able to invest in this space. Dormant assets funding can also provide the capital needed to secure and leverage wider funding from banks, social investors, and other funders. If financial inclusion is removed as a cause, there may not be any other suitable funding pots of an appropriate and effective size to grow this market.

Removing financial inclusion may therefore result in a missed opportunity to drive sustained change and amplify the impact of £100 million of dormant assets currently working to build a long-term, sustainable financial system that is able to support the most vulnerable customers in society. Estimates suggest that poor financial wellbeing costs UK private sector employers £1.56 billion each year, as money worries reduce people’s productivity at work and lead to 4.2 million missed days of work. A 2014 study also found that the social cost of problem debt experienced by 2.9 million people amounted to £8.3 billion.[footnote 36] Tackling this could therefore result in wider benefits to growth, wellbeing, and productivity across the country.

5. Social Investment

|

Chapter 5 seeks views on one of the three causes currently supported by the Scheme in England: funding for social investment wholesalers to support civil society organisations (referred to as “social investment” for simplicity). Social investment wholesalers are defined as bodies that exist to assist or enable other bodies to give financial support to third sector organisations. Third sector organisations are defined as organisations that exist wholly or mainly to provide benefits for society or the environment. |

5.1 Introduction

The 2008 Act currently defines three causes to which the English portion of dormant assets can be distributed (see Chapter 1.1). The third of these is social investment wholesalers: organisations that enable other entities to provide financial support to third sector organisations. Third sector organisations exist wholly or mainly to provide benefits for society or the environment; usually charities or social enterprises. Like businesses, they need capital in order to grow so they can have a greater impact. However, they often struggle to access finance from mainstream lenders like banks. Social investment fills this gap, enabling charities and enterprises to grow their incomes or buy assets to better meet local needs.

In addition, as people and organisations increasingly want to invest in causes they believe in, social investment has also catalysed entirely new markets, allowing funding to flow to areas like social housing at a significant scale. Crucially, all the money is invested so it is repaid and recycled, enabling funds to be reused sustainably to grow future support for trading charities and social enterprises.

5.2 Impact to date

The 2005 Independent Commission on Unclaimed Assets that led to the establishment of the Scheme recommended that the funds should be used to set up a social investment bank to help civil society organisations working in the country’s most deprived communities. Following the 2008 Act, Big Society Capital (BSC) was founded in 2012 to fulfil this vision as the world’s first social investment wholesaler and the first independent spend organisation for dormant assets funding in England. Access – the Foundation for Social Investment (Access) was founded as its sister organisation in 2015.

Through the work of both organisations, social investment in the UK has grown eightfold over the last decade, with more than £6.4 billion invested in charities and social enterprises. Evidence shows that this money has targeted the most deprived parts of the country: 65% of organisations in BSC’s portfolio are in the most deprived parts of the country and a deep-dive analysis of social investors found that 42.8% of social investment deals have gone to areas which the government has identified at Levelling up Priority 1 Areas, totalling over £521 million across nearly 2,000 investment deals.[footnote 37]

Since 2012, BSC has invested over £425 million of dormant assets money alongside £200 million from their bank shareholders to grow a range of social investment funds. BSC has leveraged other capital alongside dormant assets, turning it into more than £2.5 billion of new capital available to organisations with a social or environmental mission. This equates to more than £3 of matched funding for every £1 invested.

Investments from BSC have benefited more than 2,000 organisations serving a huge number of people across the country in a wide range of areas, including arts; heritage; conservation and the environment; employment, training and education; support for vulnerable families; andmental health and wellbeing. Examples include a £24 million investment in 55 organisations to support vulnerable young people and help children on the edge of care by intervening early, and £150 million invested into 305 charities and social enterprises supporting young people at risk of unemployment, and providing training opportunities for people disconnected from the labour market.

Since its creation in 2015, Access has received £60 million from the Scheme. It has used this funding to expand the reach of social investment by enabling smaller charities and social enterprises, particularly in more disadvantaged areas, to access the finance they need. Access focuses on growing the blended finance market: where grants are provided alongside social investment. Without some grant funding in the system, social investment itself cannot always support these civil society organisations due to the financial risks and costs involved. Access has supported this growth through a number of funds, including:

-

The Growth Fund: a partnership with BSC and TNLCF aimed at organisations that are unlikely to have taken on social investment before, which offers up to £150,000 of finance by combining grants with loans into simple, affordable products. Since 2016, the Growth Fund has made over 600 investments across 535 charities and social enterprises, with over half the money going to those working in the most deprived 30% of communities across England.

-

Local Access: a place-based programme working across six places (Bradford; Bristol; Gainsborough; Greater Manchester; Hartlepool, Redcar & Cleveland; and Southwark) to develop collaborations between charities, social enterprises, and investors to create stronger, sustainable social economies in disadvantaged areas.

-

Reach Fund: helps charities and social enterprises on the verge of taking on social investment. The programme allows social investors to refer charities and social enterprises that need additional, final stage support to raise investment. Almost 800 grants have been awarded to date, totalling more than £8.9 million.

Evidence shows that organisations are feeling the impact of the growth in blended finance: Social Enterprise UK (SEUK) reported that only 8% of social enterprises cite obtaining debt or equity as a major barrier in 2021, down from 18% in 2019.[footnote 38]

Social investment case study: Powering up communities through renewable energy

BSC has invested £20 million to fund large-scale community energy projects, enabling communities to own and control renewable energy assets, generating their own energy and reinvesting the profits to benefit local people. The Sustainable Capital Bridge Fund (formerly Leapfrog) helps local groups to fund construction and acquire existing assets.

Warrington Borough Council has been supported through the fund to be the first local council in the country to produce all of its electricity from renewable sources. Its solar farm will produce enough electricity to power almost 11,000 homes and will save over 13,500 tonnes of carbon per year. Additionally, almost 200 acres have been given back to nature, helping to protect species through the introduction of bee hives and wild flowers.

Alongside funding the construction of the solar farm, the investment also led to the establishment of a Community Benefit Fund. This initiative ensures a proportion of the surplus is used to support social wellbeing programmes in the local area and finance fuel poverty reduction projects. This includes supporting vulnerable individuals to benefit from renewable energy and energy efficiency measures, providing advice, technology, and energy saving measures, as well as other relevant support. It is estimated that the Community Benefit Fund will generate £85,000 per annum over 30 years for investment back into the local community.

5.3 Potential opportunities for further impact

Over the last 10 years, dormant assets funding has enabled key areas of the social investment market to develop and scale without the need for further injections of dormant assets. However, there are other areas of the market that are still in their infancy and could benefit from continued support from dormant assets to grow their impact, reach their full potential, and become equally self-sustainable.

The biggest area of need that remains in the sector is enabling social investment to support smaller charities, social enterprises, and community businesses in the most deprived and underserved communities. The Growth Fund evaluation found that blended finance reaches the most disadvantaged communities at four times the rate of the wider social investment market.[footnote 39] Future dormant assets funds could therefore be used to build on the impact the Scheme has had to date on blended finance and seek to further extend the availability of small, flexible, and affordable loans. By its nature, the grant element of blended finance requires an ongoing supply of funding. While the provision of grants in blended products to charities and social enterprises is likely to continue to grow among trusts and foundations, evidence indicates that this growth will be insufficient to meet demand.[footnote 40] As such, there could be an ongoing role for future dormant assets to maintain market infrastructure and ensure impact is not lost over the next decade (see Chapter 5.4 below).

The demand from civil society organisations for smaller amounts of finance is greater than the wider social investment market currently offers. SEUK research shows that social enterprises are usually seeking median amounts of around £50,000.[footnote 41] Evidence from a recent review by New Philanthropy Capital (NPC) into blended finance also indicates that there is great demand in the sector for blended finance products. A survey conducted by one social investor showed that 29% of the sample felt that a grant/loan blended product would best meet their future needs. This was the most popular answer, above grants at 24% and loans at 5%.[footnote 42]

5.4 Consequences of removing social investment wholesalers as a cause

The recent Commission on Social Investment, set up by Lord Victor Adebowale CBE, reported that a lack of subsidy in social investment would ‘leave a significant hole in the marketplace, particularly for the smallest social enterprises and those operating in the most deprived communities.’[footnote 43] This follows similar conclusions of The Oversight Trust in 2021, which found that the ongoing provision of blended capital and enterprise development through Access is ‘essential to the charity and social enterprise sector’s impact in the most deprived communities.’[footnote 44]

The NPC review similarly concluded that there are currently no other sources of funding, besides future dormant asset funds, which are sufficient to meet the scale required in the short- and medium-term to maintain the blended finance market. The review outlines a number of potential impacts if dormant assets support is removed and an equitable source for the subsidy is not found. This includes harm to the social investment ecosystem as a whole: social investment intermediaries may not be able to offer investment to smaller organisations in more deprived communities, which could lead to them collapsing or changing their models. It may also harm the growth of charities and social enterprises as they struggle to access more mainstream finance, with a disproportionate impact on organisations operating in the most disadvantaged communities and find it hardest to access mainstream finance.[footnote 45]

6. Community Wealth Funds

| Chapter 6 seeks views on whether community wealth funds should start receiving support from the Scheme in England. Community wealth funds are defined in the 2022 Act as funds which give long-term financial support (whether directly or indirectly) for the provision of local amenities or other social infrastructure. |

6.1 Introduction

Community wealth funds (CWFs) are pots of money distributed over long-term periods (circa 10 years), with spending decisions made by local residents on how to improve their communities and lives. These communities would be hyper-local, going beyond Local Authority level into neighbourhoods of typically less than 10,000 residents, and experiencing high levels of deprivation and low social capital.

There are various models of CWFs, including where residents are able to identify outcomes that are important to them and develop bespoke solutions, and where neighbourhoods are supported with targeted funding and support to achieve their ambitions. These neighbourhoods may have been excluded from accessing funding to help address these challenges in the past. This may be because of a lack of knowledge about grant processes, or the skills and experiences needed to apply for alternative funding sources or identify challenges and solutions. CWFs seek to close these gaps by investing time and money into building the necessary capacity of the local communities involved. This chapter invites your views on whether CWFs should become a cause for the English portion of dormant assets funding.

If respondents are minded that CWFs should start receiving support from the Scheme in England, we would welcome views on whether its definition in the 2022 Act is suitable to ensure maximum impact of any potential funding. In line with the additionality principle (see Annex B), any interventions funded through CWFs could not be a substitute for government funding.

6.2 Delivery

The scope of this consultation is on broad social and environmental causes, rather than specific ways to deliver the funding. This offers flexibility, protects longevity, and aligns with the approach taken to broadly define the current three causes of youth, financial inclusion, and social investment. It is therefore important to note that detailed views on specific delivery models or releases of funding are out of scope of this consultation (see Chapter 1.3).

Accordingly, no decisions have been made on any specific delivery models or delivery partners if a community wealth fund is chosen as a cause.

Dormant assets money is not a guaranteed regular funding stream. Voluntary participation and expansion into new and complex asset classes mean it is difficult to accurately predict the flow of funding into the Scheme. This is especially relevant in the first few years of the expanded Scheme. Any causes that rely on secure, constant funding flows, or an immediate substantial injection of money, may not be suitable for the Scheme without work to mitigate against this reliance (see essential criteria 8, Chapter 2.2).

6.3 Potential opportunities for impact

Across the UK, geographical differences in productivity, pay, crime, health, and educational attainment disproportionately affect areas such as coastal towns, former mining communities, and outlying urban estates – and there are many instances where pockets of deprivation exist near pockets of affluence.[footnote 46] Research suggests that communities in deprived areas suffering from poor connectivity, low levels of community engagement, and lack of community spaces experience worse social and economic outcomes for residents.[footnote 47] It is clear that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to regeneration, and that place-based approaches have the potential for greater community involvement in decision-making.

In Onward’s Turnaround review[footnote 48] of regeneration initiatives both in the UK and abroad, it was found that the most successful approaches:

-

focused on smaller geographic areas, such as neighbourhoods;

-

invested in community capacity over the long-term, and

-

helped communities to take ownership of local assets.

The most successful regeneration programmes ensure communities have a stake in the process, which includes empowering local people with setting priorities and making decisions, devolving budgets, and building new community-level institutions. These programmes also protect time and money to develop skills, experience, and knowledge in communities, building capacity to increase the likelihood of communities being able to maintain improvements in the long-term.

CWF case study: Big Local The Big Local programme is driven by a £217 million endowment from TNLCF and managed by Local Trust. It supports local residents in 150 neighbourhoods across England to make decisions on how to use £1.15 million of funding to create lasting change in their neighbourhoods. These neighbourhoods have experienced higher than average levels of deprivation and had previously missed out on lottery or other public funding.

The Big Local programme has four broad aims:

- communities will be better able to identify local needs and take action in response

- people will have increased skills and confidence, so that they continue to identify and respond to needs in the future

- the community will make a difference to the needs it prioritises; and

- people will feel that their area is an even better place to live.

Among diverse solutions to place-based challenges, 98 areas have built or renewed a community hub to anchor their neighbourhood activities, creating a space for community groups to meet and residents to form meaningful relationships. Residents have also engaged in peer learning opportunities and training sessions on measuring change, and have benefited from guidance for building digital confidence.

One of the strengths of the CWF proposal is its focus on funding over the long-term. Patient funding allows for learning and capacity building in communities, without the pressure of money needing to be spent quickly. Some Big Local areas have managed to secure assets to help amplify and sustain their impact. Examples include Collyhurst Big Local acquiring empty land through housing stock clearance and creating a business incubation space on it using shipping containers – and Whitley Bay Big Local using funding through the Community Ownership Fund to purchase premises for a community hub. However, the long-term focus also means that some of the Big Local areas are still engaging in community-led improvements and responding to unexpected effects of the pandemic. It is therefore difficult at this stage to evaluate its long-term legacy and the sustainability of both the interventions and the community engagement.

Interim evaluations, though, have found that a Big Local-inspired approach has the potential to generate a number of positive outcomes for the individuals, groups, and broader communities they serve, as well as having a national impact:[footnote 49],[footnote 50]

1. Positive outcomes for individuals include:

-

reduced loneliness and social isolation;

-

increased community engagement and aspirations;

-

increased confidence and self esteem through involvement and formal support; and

-

employment opportunities, especially for young people.

2. Positive outcomes for local groups include:

-

the creation, growth, and development of community and voluntary organisations;

-

grant programmes for local organisations; and

-

improvements in capacity: some small initiatives supported by Big Local have gone on to secure other grant funding or contracts.

3. Positive outcomes on the broader community include:

-

physical and environmental improvements (such as play and leisure facilities, development of environmentally friendly homes, and approved plans for community-led and co-operative housing);

-

enhanced community cohesion and networks (such as a community café becoming a place for residents to access personal support groups;[footnote 51])

-

improved relationships between communities and partners (such as working with local authorities and the civil society sector to target issues that are particularly important to local residents;[footnote 52]) and

-

community-owned assets: places to meet and/or to create a sustainable economic model (such as community hub buildings and business incubation spaces)

4. Positive national impacts include financial and social benefits:

Research into the economic case of investments such as a CWF[footnote 53] has estimated that a £1 million investment in similar areas to Big Local over a ten-year period could generate:

-

£1.2 million of financial benefits – such as employer tax, benefits, and healthcare savings, and reduced financial costs of crime; and

-

£2 million of social and economic benefits – such as increased employment, improved health and wellbeing, and reduction in crime.

Alongside the benefits of CWF programmes, there have also been some challenges faced by those involved in Big Local projects. Programme evaluations have suggested that resident-led change can sometimes face difficulties, highlighting areas which could be taken as lessons for good CWF design in the future, including:[footnote 54]

-

Time: some programmes struggled to maintain momentum over long periods.

-

Participation: pressure is placed on a small number of participants, and some areas experienced difficulties with engaging new residents.

-

Internal struggles: differing personalities could lead to power struggles within groups.

-

External struggles: difficulties in linking community-specific problems with wider, often national, strategies led to some feeling distant from local and regional power holders.

While the success of, and need for, place-based approaches is broadly recognised, the evidence base to determine what specific actions make the most difference is still in development. If CWFs become a cause for dormant assets funding in England, a robust programme of evaluation would be built into the model in order to add to the understanding of what works in this area.

7. Alternative causes

| Chapter 7 invites suggestions of other broad social or environmental cause(s) that could be considered for the Dormant Assets Scheme in England, apart from the four causes presented in previous chapters (youth, financial inclusion, social investment, and community wealth funds). |

7.1 Introduction

The government has consistently committed to ensuring this consultation is a genuinely open conversation about what social or environmental purposes should benefit from dormant assets funding in England going forwards. This chapter therefore provides the opportunity for people, participants, and organisations to tell us your views. If you believe multiple causes should be considered, including those in earlier chapters, we would also like to understand how you would rank your answers in order of importance to you.

These responses will help to inform decisions on the broad focus of the English portion. The question therefore does not regard any specific release of money, distribution mechanism, or delivery partners. It is not a bidding process for organisations to access funding.

7.2 Criteria for the English portion

We recommend that responses take into consideration the set of criteria, set out in Chapter 2, which the government will use when assessing potential social and environmental causes. These are summarised in the table below:

| Essential criteria | 1. A social or environmental initiative 2. Sufficient scope to fund initiatives that would not otherwise be funded by the government (the additionality principle) 3. A portion of £738 million must have a meaningful impact 4. Targeting sustained, high-impact change 5. Ability to attribute and measure the impact achieved 6. Ability to align with key government policy priorities, including securing voluntary industry support 7. Nationwide impact across England, particularly in disadvantaged areas 8. Capable of weathering uncertain funding flows |

| Desirable criteria | 1. Contribute positively to good community relations and integration 2. Ability to leverage in other sources of funding 3. Using existing organisations and/or systems of delivery, governance, and accountability |

8. How to respond

Please respond to the consultation by completing the below online survey:

Please respond before 23:45 on Sunday 9 October 2022.

This consultation covers England only.

We welcome comments from all stakeholders who may be interested.

Alternatively, you can respond by completing the response sheet and emailing it to dormantassetsconsultation@almaeconomics.com.

If you are unable to submit your response electronically, you can download this document and post it to: Dormant Assets Team, DCMS, 4th Floor, 100 Parliament Street, London, SW1A 2BQ.

When responding, please state whether you are responding as an individual, or on behalf of an organisation, multiple individuals or multiple organisations. We are keen to hear from a wide range of respondents, and encourage likeminded stakeholders to submit joint responses where appropriate. If responding on behalf of multiple individuals or organisations, please make it clear who you are representing and, if applicable, how their views were assembled.

To enable us to process the results of this consultation efficiently and ensure answers can be compared appropriately, please do not submit responses that do not use the online survey or response sheet provided.

If you require a copy in an alternative format or have any questions, please email us at dormantassetsconsultation@almaeconomics.com.

8.2 Privacy notice

8.2.1 Who is collecting my data?

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) helps to drive growth, enrich lives and promote Britain abroad.

We protect and promote our cultural and artistic heritage and help businesses and communities to grow by investing in innovation and highlighting Britain as a fantastic place to visit. We help to give the UK a unique advantage on the global stage, striving for economic success.

This website (“Website“) is run by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (“we” and “us“, “DCMS“). DCMS is the controller for the personal information we process, unless otherwise stated.

We are working with Alma Economics to manage this consultation process. This will be for the purpose of data analysis.

8.2.2 Purpose of this Privacy Notice

This notice is provided within the context of the notice provided to meet the obligations as set out in Article 13 (this sets out the info we have to provide where the data is received directly from the data subject). Article 13 of UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA). This notice sets out how we will use your personal data as part of our legal obligations with regard to Data Protection.

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport’s personal information charter (opens in a new tab) explains how we deal with your information. It also explains how you can ask to view, change or remove your information from our records.

8.2.3 What is personal data?

Personal data is any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural living person, otherwise known as a ‘data subject’. A data subject is someone who can be recognised, directly or indirectly, by information such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or data relating to their physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity. These types of identifying information are known as ‘personal data’. Data protection law applies to the processing of personal data, including its collection, use and storage.

8.2.4 How will we use your data?

We use personal information for a wide range of purposes, to enable us to carry out our functions as a government department.

8.2.5 What is the legal basis for processing my data?

To process this personal data, our legal reason for collecting or processing this data is: Article 6(1): you have freely given your consent – it will be clear to you what you are consenting to and how you can withdraw your consent.

8.2.6 What will happen if I do not provide this data?

If your personal data is not provided you will be unable to contribute your views to this consultation.

8.2.7 Who will your data be shared with?

We will share this information with Alma Economics who DCMS are working with to manage the consultation process. This will be for the purpose of data analysis.

8.2.8 How long will my data be held for?

We will only retain your personal data for two years, in line with DCMS retention policy, if it is needed for the purposes set out in this document.

8.2.9 Will my data be used for automated decision making or profiling?

We will not normally use your data for any automated decision-making. If we need to do so, we will let you know.

8.2.10 Will my data be transferred outside the UK and if it is, how will it be protected?

We will not send your data beyond the European Economic Area. If we need to do so, we will let you know.

8.2.11 Links to other websites

Where we provide links to websites of other organisations, this privacy notice does not cover how that organisation processes personal information. We encourage you to read the privacy notices of the other websites you visit.

8.2.12 What are your data protection rights?

You have rights over your personal data under the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018). The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is the supervisory authority for data protection legislation, and maintains a full explanation of these rights on their website

DCMS will ensure that we uphold your rights when processing your personal data.

8.2.13 How do I complain?

The contact details for the data controller’s Data Protection Officer (DPO) are: Data Protection Officer, The Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, 100 Parliament Street, London, SW1A 2BQ, Email: dpo@dcms.gov.uk

If you are unhappy with the way we have handled your personal data and want to make a complaint, please write to the department’s Data Protection Officer or the Data Protection Manager at the relevant agency. You can contact the department’s Data Protection Officer using the details above.

8.2.14 How to contact the Information Commissioner’s Office

If you believe that your personal data has been misused or mishandled, you may make a complaint to the Information Commissioner, who is an independent regulator. You may also contact them to seek independent advice about data protection, privacy and data sharing.

Information Commissioner’s Office, Wycliffe House, Water Lane, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 5AF, Website: www.ico.org.uk, Telephone: 0303 123 1113, Email: casework@ico.org.uk

Any complaint to the Information Commissioner is without prejudice to your right to seek redress through the courts.

8.2.15 Changes to our privacy notice

We may make changes to this privacy policy. In that case, the ‘last updated’ date at the bottom of this page will also change. Any changes to this privacy policy will apply to you and your data immediately.

If these changes affect how your personal data is processed, DCMS will take reasonable steps to let you know.

This notice was last updated on 16/07/2022.

Annex A: Consultation Questions

Questions on respondents

1. Are you responding as an individual or on behalf of an organisation? (select only one)

-

Individual [skip to Q10]

-

Organisation [continue to Q2]

2. What is the name of your organisation?

3. What type of organisation do you work for? (select only one)

-

Academic think-tank

-

Business or private sector

-

Civil society (charity etc.)

-

Public sector body

-

Other [textbox with a 50 character limit]

4. Is your organisation a current or prospective participant of the Dormant Assets Scheme? (select only one)

-

Yes [continue to Q5]

-

No [skip to Q6]

5. In which sector(s) does your organisation operate? [Regardless of the answer, then skip to Q7]

-

Banks and building societies

-

Insurance and pensions

-

Investment and wealth management

-

Securities

6. Please select the primary sector in which your organisation operates. (select only one) [Regardless of the answer, then continue to Q7]

-

Agriculture

-

Business support consultancy

-

Community development

-

Creative industries

-

Culture and leisure

-

Domestic services/cleaning

-

Education and skills development

-

Employment and skills

-

Environmental

-

Financial support and services

-

Healthcare

-

Hospitality

-

Housing

-

IT

-

Manufacturing

-

Retail

-

Social Care

-

Transport

-

Utilities (energy)

-

Workspace/room hire

-

Other [textbox with a 50 character limit]

7. Does your organisation operate in England? (select only one)

-

Yes [Continue to Q8]

-

No [Skip to Q9]

8. Where does your organisation operate? (select only one)

[Regardless of the answer, then skip to Q13]

-

Multiple English regions

-

East Midlands

-

East of England

-

London

-

North East

-

North West

-

South East

-

South West

-

West Midlands

-

Yorkshire and the Humber

9. Where does your organisation operate? (select only one)

Please note that this consultation will help inform government decisions on the Dormant Assets Scheme in England only. [Regardless of the answer, then skip to Q13]

-

UK-wide and/or internationally

-

Northern Ireland

-

Scotland

-

Wales

10. Do you live in England? (select only one)

-

Yes [Continue to Q11]

-

No [Skip to Q12]

11. Where do you live? (select only one)

[Regardless of the answer, then skip to Q13]

-

East Midlands

-

East of England

-

London

-

North East

-

North West

-

South East

-

South West

-

West Midlands

-

Yorkshire and the Humber

12. Where do you live? (select only one)

Please note that this consultation will help inform government decisions on the Dormant Assets Scheme in England only. [Regardless of the answer, then continue to Q13]

-

Northern Ireland

-

Scotland

-

Wales

13. Do you want your response to be treated as confidential or do you agree for your answers to be quoted on an anonymised basis? (select only one)

-

I want my response to be confidential

-

I agree for my answers to be quoted on an anonymised basis

Section 1 – Youth

14. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

“Youth should continue to remain a cause of the Dormant Assets Scheme in England”. (select only one)

-

Strongly agree

-

Agree

-

Neither agree nor disagree

-

Disagree

-

Strongly disagree

15. Please explain the reasons for the answer you have given.

Section 2 – Financial inclusion

16. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

“Financial inclusion should remain a cause of the Dormant Assets Scheme in England”. (select only one)

-

Strongly agree

-

Agree

-

Neither agree nor disagree

-

Disagree

-

Strongly disagree

17. Please explain the reasons for the answer you have given.

Section 3 – Social investment

18. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

“Social investment wholesalers should remain a cause of the Dormant Assets Scheme in England”. (select only one)

-

Strongly agree

-

Agree

-

Neither agree nor disagree

-

Disagree

-

Strongly disagree

19. Please explain the reasons for the answer you have given.

Section 4 – Community wealth funds

20. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

“Community wealth funds should become a cause of the Dormant Assets Scheme in England”. (select only one)

-

Strongly agree

-

Agree

-

Neither agree nor disagree

-

Disagree

-

Strongly disagree

21. Please explain the reasons for the answer you have given.

22. Community wealth funds are defined in the Dormant Assets Act 2022 as funds which give long-term financial support (whether directly or indirectly) for the provision of local amenities or other social infrastructure.

Do you agree with the definition of community wealth funds as being suitable for the Dormant Assets Scheme?

-

Yes [Skip to the next section]

-

No [Continue to Q23]

-

Don’t know or don’t want to comment [Skip to the next section]

23. Please explain the reasons for the answer you have given.

Section 5 – Alternative causes

24. Would you like to suggest other cause(s) you think should receive funds from the Dormant Assets Scheme?

(We welcome suggestions of broad causes not currently considered by the Scheme. Please note that any suggestions will be assessed according to the essential and desirable criteria.)

-

Yes [Continue to Q25]

-

No [Skip to Q29]

25. Please specify the alternative cause that you consider to be most important.

26. Please rank the causes below by order of importance – 1 being the most important to you. (options showing in randomised rows to avoid response bias)

-

Youth

-

Financial inclusion

-

Social investment wholesalers

-

Community wealth funds

-

The alternative cause that you consider to be most important (specified in your previous answer)

27. Please explain why the alternative cause that you consider to be most important should receive funds from the Dormant Assets Scheme.

28. Please suggest any other cause you think should receive funds from the Dormant Assets Scheme.

29. Please rank the causes below by order of importance – 1 being the most important to you (options showing in randomised rows to avoid response bias)

-

Youth

-

Financial inclusion

-

Social investment wholesalers

-

Community wealth funds

30. Do you have any comments on whether secondary legislation should prescribe specific purposes?

Section 6 - Public Sector Equality Duty

31. Do you have any comments about the potential positive and/or negative impacts that the options on the broad purposes of the Dormant Assets Scheme in England outlined in this consultation may have on individuals with a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010?

-

Yes [continue to question 32]

-

No [skip to question 33]

32. Please explain what you think these impacts (both positive and/or negative) would be.

33. In your view, is there anything that could be done to mitigate any negative impacts?

-

Yes [continue to question 34]

-

No [end of the consultation]

34. Please specify what you think could be done to mitigate the negative impacts.

Annex B: Policy on the additionality principle

Principle

The principle of additionality is a central tenet of the Dormant Assets Scheme and critical to its success. Reliant on voluntary participation, the Scheme is led by industry and backed by the government. In order to protect its impact, it is imperative that this money cannot be used to substitute the government’s own spending and should not reduce other forms of public support for the important social and environmental issues it seeks to tackle.