Government response and summary of responses

Updated 21 February 2023

1. Introduction and context

The consultation on biodiversity net gain (BNG) regulations and implementation was launched in January 2022 and ran for 12 weeks. It was supported by a consultation document, market analysis study, impact assessment for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs), and a report detailing results of an economic appraisal for major infrastructure projects.

The consultation covered the 3 main areas:

-

the scope of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (TCPA) requirement and proposed exemptions; development within statutory designed sites, and irreplaceable habitats

-

applying BNG to different types of development, including phased development; small sites; NSIPs

-

how mandatory BNG will work for TCPA development and an example biodiversity gain plan

This Government response aims to summarise current policy positions and report on responses. Any changes to previously published policy positions or processes will be clearly highlighted. A detailed summary of responses to each question is presented in Annex A.

The government provided £4.18 million of funding to local government alongside the consultation to provide support to prepare for mandatory BNG. This funding was distributed to local authorities in England in 2022. We have heard through responses to this consultation that concerns remain in relation to local authority capacity. Therefore, we can confirm that we will be providing up to £16.71 million of funding for Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) to prepare for mandatory net gain between now and November 2023.

2. Respondents

A total of 590 responses were received during the consultation period. The majority (440) of these were submitted through the online portal, Citizen Space. We received an additional 186 written responses by email or letter, 36 of which were duplicates of responses received through Citizen Space.

We are grateful to everyone who took the time to respond and share their experience, views and suggestions. All responses were considered in the development of policy and this government response.

2.1 Stakeholder events

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) held a series of stakeholder workshops in February 2022. This provided Defra with useful, in-depth feedback prior to the consultation closing. Attendees of the stakeholder workshops included local planning authorities, non-governmental organisations, developers, consultancies, professional institutes, academics and wider industry. The Planning Advisory Service ran several events for local planning authorities.

2.2 Breakdown of respondents

There was a broad sectoral distribution of respondents. The largest respondent group was LPAs and their representatives. Other large groups of respondents comprised businesses (including developers and consultancies), members of the public and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Developers were asked to specify whether they were housebuilders, commercial/industrial, mixed, or other. Collectively, 11.6% of responses were from developers.

A response to the consultation and additional advice was provided by the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP).

A significant number of responses were from large organisations or membership bodies. The percentage of responses cited for each question throughout the summary of responses does not, therefore, present a representative sample of stakeholder views.

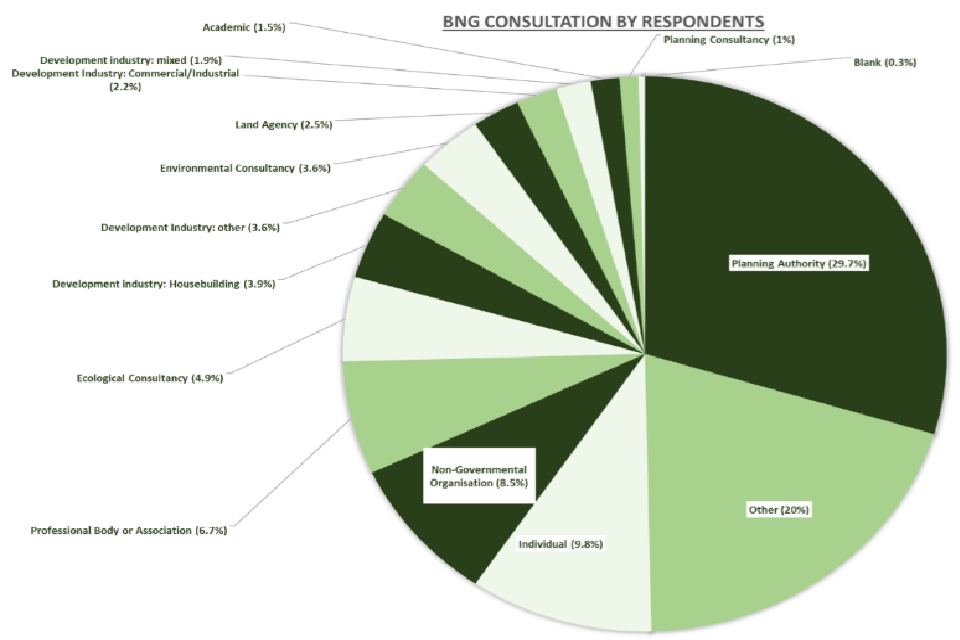

2.3 Figure 1: Approximate breakdown of respondents to the net gain consultation by reported or assigned type of organisation.

Pie chart showing BNG respondents by type of organisation.

3. Government response part 1: Defining the scope of the BNG requirement for Town and Country Planning Act 1990 development

3.1 Exemptions

The Environment Act 2021 already makes exemptions for permitted development and urgent crown development. The biodiversity metric, subject to its own consultation[footnote 1], allows for temporary impacts that can be restored within 2 years to be excluded from calculations. It also gives existing sealed surfaces (such as tarmac or existing buildings) a zero score, meaning that these surfaces are effectively exempted from the percentage gain requirement. We consulted on whether any further exemptions are necessary to keep the policy ambitious but proportionate.

We intend to use regulations to make exemptions for:

-

development impacting habitat of an area below a ‘de minimis’ threshold of 25 metres squared, or 5m for linear habitats such as hedgerows

-

householder applications

-

biodiversity gain sites (where habitats are being enhanced for wildlife)

In addition to the exemptions above, we propose to exempt small scale self-build and custom housebuilding. We will aim to define this exemption in a way that addresses the risks of exempting large sites made up of many custom plots and will keep this under review.

Exempt development outside the scope of mandatory net gain still provides opportunity for biodiversity enhancements that could be secured through planning policy. We will work with DLUHC to develop planning policy for minor development such as householder and de-minimis development, to seek to secure proportionate on-site biodiversity enhancements where possible.

Other than where they are covered by the exemptions above, we do not intend to specifically exempt:

-

previously developed land (though some sites will effectively be exempted by a zero baseline score in the metric)

-

change of use applications (though the majority of types of change of use application will be exempt through the de minimis habitat exemption)

-

temporary applications (though the metric makes allowances for short term habitat loss)

-

developments which would be permitted development but are not on account of their location in Conservation Areas, for example, areas of outstanding natural beauty or national parks, which are subject to some restrictions on permitted development rights (though de minimis and householder exemptions mean we think this will have little effect in practice)

3.2 Development within statutory designated sites for nature conservation

We will not be making an exemption for development on statutory sites designated for nature conservation from the BNG requirement. As proposed, we intend to use policy and guidance to prevent BNG being used as a justification for otherwise unacceptable development on such sites. Reporting should distinguish between meeting the BNG requirement and meeting other requirements, which is discussed further in the ‘additionality’ section of this response document.

3.3 Irreplaceable habitat

We asked respondents whether they agreed with our proposals to:

a. Exclude irreplaceable habitat from the quantitative mandatory biodiversity gain objective.

b. Include a requirement to submit a version of a biodiversity gain plan for development (or component parts of a development) on irreplaceable habitats to increase proposal transparency.

c. Allow the use of the biodiversity metric to calculate the value of enhancements of irreplaceable habitat where there are no negative impacts to irreplaceable habitat.

d. Use the powers in BNG legislation to set out a definition of irreplaceable habitat, which would be supported by guidance on interpretation.

e. Provide guidance on what constitutes irreplaceable habitat to support the formation of bespoke compensation agreements.

Respondents expressed strong agreement with all 5 proposals for irreplaceable habitats (listed above). The updated policy and processes set out below reflect consultation responses and additional stakeholder engagement undertaken since January 2022.

We will use secondary legislation to set out a clear definition of irreplaceable habitat and list of habitat types to be considered irreplaceable. We will be consulting on this definition and seeking views on the proposed list. The definition statement will be published for transparency, but it is not intended for direct use in decisions on whether habitats are considered irreplaceable. Those trying to establish whether a habitat is irreplaceable should refer to the list of habitats instead.

Secondary legislation will also be used to disapply the 10% measurable net gain requirement for irreplaceable habitat, and to apply separate information requirements that can be used by the planning authority in determining the planning application:

-

The biodiversity gain objective (referred to in para 2 of Pt. 1 of Environment Act’s Schedule 14/7A) is to be replaced with a requirement for appropriate compensation relative to the baseline habitat type. The planning authority must be satisfied that as a minimum, the mitigation or compensation plan meets requirements in relevant policy and guidance, and decisions on planning applications should be made in line with the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

-

Development on irreplaceable habitats, and consequent habitat losses and gains, are to be accounted for, either in a separate section of the biodiversity gain plan template, or a separate report to be submitted to the relevant planning authority alongside the biodiversity gain plan. A separate tab of the metric calculator tool must be completed which documents all irreplaceable habitat onsite. This will ensure losses of, and compensation for, irreplaceable habitat is recorded and communicated clearly

-

We will state that statutory biodiversity credits must not be used to compensate for residual irreplaceable net losses resulting from development or land use change

-

Alongside the standard requirement for a biodiversity gain plan, applications involving development on irreplaceable habitat should set out a robust summary statement of reasonable alternatives explored for the development that would avoid the loss of irreplaceable habitats and why they were not feasible

4. Government response part 2: Applying the biodiversity gain objective to different types of development

4.1 Phased development and development subject to subsequent applications

As we proposed for outline planning permissions, or development which is to be permitted in phases, we will require additional biodiversity gain information that sets out how biodiversity gain will be achieve across the whole site on a phase-by-phase basis. We will also require that such development should be subject to a condition which requires approval of a biodiversity gain plan prior to commencement of each phase. We will proceed with this proposal, but have noted concerns about any overly rigid requirements for delivering higher biodiversity gains in early phases (‘front-loading’) and that it will be important to leave room for discretion for local planning authorities when it comes to deciding this. We are committed to ensuring an efficient, user-friendly process for phased development and will set out details about this process through secondary legislation and accompanying guidance.

Changes to minerals permissions and varying existing permissions

We recognise concerns raised about our proposal that Reviews of Old Minerals Permissions (ROMPs) should remain out of scope of BNG. We believe that these can be addressed through existing policy and discussions with minerals planning authorities, and that applying the new mandatory approach to old permissions with existing restoration plans would be disproportionately complex. We will instead use policy to support an approach based on appropriate ecological outcomes rather than percentage targets.

We intend to address concerns from the minerals industry about how BNG fits with their sector’s long development timelines, and those raised about the process’s ability to recognise the value of habitats created incidentally through mineral operations, through guidance and policy informed by further engagement with relevant sectors.

In the case of variations of planning permissions, respondents suggested that any Section 73 application that would result in a change to the post-development biodiversity value should require an updated biodiversity gain plan. Most of the respondents agreed that original pre-development baseline should apply, and Section 73 variation applications should be bound by the net gain condition. Some noted that this would not work where the original permission was granted before mandatory BNG was commenced. Subject to further engagement, we therefore intend to only apply the requirement to Section 73 applications where the original permission was granted after commencement of the mandatory BNG requirement. We have noted that guidance will be needed about what constitutes a change requiring an updated biodiversity gain plan. This was raised most clearly for minerals sites, for which Section 73 applications are often used to extend phases and could result in biodiversity unit costs when restoration plans are accordingly delayed.

4.2 Small sites and reducing the burdens of the process

As proposed, we are going to provide a small sites metric for developments which meet its size and absence of priority habitats criteria. We also accept that clear guidance, as well as innovative approaches to automation and digital support, will be critical to ensure that SME developers can engage with BNG positively to deliver greener developments.

While respondents were generally supportive of the November 2023 commencement date, they raised concerns about how prepared local planning authorities are. To lessen initial burdens and allow a longer period for developers and local planning authorities to adapt and prepare for the high volume for minor applications, we will extend the transition period for small sites until April 2024.

Small sites are defined for the purpose of the BNG exemption as:

(i) For residential: where the number of dwellings to be provided is between one and nine inclusive on a site having an area of less than one hectare, or where the number of dwellings to be provided is not known, a site area of less than 0.5 hectares.

(ii) For non-residential: where the floor space to be created is less than 1,000 square metres OR where the site area is less than one hectare.

We asked if there were any additional process simplifications (beyond a metric) that would help reduce the burden for small sites. We received several good suggestions that we will explore and implement where possible, including:

-

improved spatial mapping of habitats to guide development to less biodiverse sites (which we hope will be provided through and alongside Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS))

-

a simplified biodiversity gain plan template or process for small developments

-

online training and guidance specifically for smaller developments and users of the small sites metric, including references to how gardens and amenity green spaces should usually be recorded and the types of on-site features that could generally help them towards achieving biodiversity gains

-

ensuring that the biodiversity unit allocation and statutory biodiversity credits sales mechanisms are fit for use with the small volumes that are likely to be required by smaller developments

-

as we have proposed in our separate metric consultation, adding clearer outputs to the biodiversity metric tool so that it is easier to see what is needed to achieve BNG

-

making it clear in planning guidance that, whilst higher net gain percentages may be set in local planning policy, careful consideration should be given to the feasibility of requirements above 10%

We are supportive of digital tools to help with the process of BNG, provided they do not reduce the quality of ecological information or overcomplicate the process.

4.3 Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs)

Scope, percentage, and targeted exemptions

We intend to apply BNG for NSIPs without any broad exemptions other than the provision made for development on irreplaceable habitats. Using the same broad approach for NSIPs will help to create consistency between different types of projects, reducing the scope for confusion and the need to define requirements in reporting.

Setting the requirement and transition arrangements through ‘biodiversity gain statements’

Due to their significant scale and complexity, it will be particularly important to ensure that NSIPs developers have sufficient time to incorporate BNG into their designs. The majority of respondents wanted an earlier date for the NSIPs requirement than we proposed, but respondents from the infrastructure sector stated that they needed two years to prepare. Therefore, we will keep the current position, with the requirement in place no later than November 2025, to allow NSIPs developers time to prepare. We will produce a draft biodiversity gain statement for NSIPs this year and begin to consult with industry and wider stakeholders on this draft as soon as possible. We will encourage projects to adopt BNG earlier on a voluntary basis wherever possible.

NSIP off-site gains and a ‘portfolio approach’

Recognising respondents concerns that this could discourage proper application of the mitigation hierarchy, we do not intend to facilitate lighter touch approaches to the off-site biodiversity gains for NSIPs. We intend to stipulate that NSIP off-site gains will need to be recorded in a biodiversity gain site register, as is the case for development under the TCPA.

Process and demonstrating biodiversity net gains

It is important that the applicant can clearly demonstrate that the BNG objective has been met through the examination process. We intend therefore to keep the NSIPs approach broadly consistent with the TCPA approach, meaning that developers or scheme promoters will need to prepare a form of biodiversity gain plan and a completed biodiversity metric.

To remove the incentive to clear habitats in advance of ecological assessments, we intend to make provision in the biodiversity gain statement for an earlier habitat value to be applied as the baseline where the value of habitats has been recently degraded. Where habitats have been degraded since January 2020, the pre-degradation habitat should be taken as the baseline.

Some NSIPs need to include significant areas for environmental mitigation within their project boundaries. We do not intend to make a distinction for NSIPs between on-site habitats (which are subject to BNG) and any dedicated environmental mitigation areas included in the project boundary. This maintains consistency with the approach for TCPA development. We will consult further on this proposal through the draft biodiversity gain statement.

Maintenance period for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project developments

The minimum duration for secured off-site biodiversity gains allocated to NSIPs will be specified in biodiversity gain statements. We recognise the potential, highlighted by many respondents, for NSIPs to deliver longer-lasting gains. The minimum duration for which biodiversity gains must be secured will initially be set at 30 years. This will help to ensure that the market for biodiversity gains can function fluidly across consenting regimes. The Environment Act 2021 includes a requirement to keep this duration under review, and the minimum duration for NSIPs would be increased in line with any increases to the minimum for TCPA development. This will not apply retrospectively to existing gain sites or developments which have already received consent and would be done with sufficient notice to allow industry to plan for the transition.

Compulsory acquisition

We recognise the concerns raised by some respondents on the negative impact of compulsory acquisition on landowners, and their preference for compulsory acquisition to be used as a last resort for BNG delivery. We are not intending to make any new provisions for compulsory acquisition. We will, however, consider providing guidance or reference in biodiversity gain statements that outlines the reasonable alternatives developers should explore to deliver net gain before they consider compulsory acquisition of land.

Marine infrastructure

Responses to this section raised a number of helpful suggestions and observations that we will take into account for both NSIPs and TCPA development. We will also:

-

provide clarity on the relationship between terrestrial/intertidal and marine net gain units as the marine net gain process is established

-

ensure that the BNG approach enables intertidal and marine projects to contribute to ecologically meaningful strategic projects at larger scales, off site in the intertidal zone

-

aim to provide alignment between the marine licensing and planning system regimes to minimise any conflicting demands or duplication in processes

-

put in place the statutory credits system so that intertidal and coastal projects can meet their net gain obligations through payments into national projects, in the event that there is a shortage of market or developer-led intertidal or coastal biodiversity units

5. Government response part 3: How the mandatory BNG requirement will work for Town and Country Planning Act 1990 development

5.1 Biodiversity gain plan

We asked respondents whether they agree with the proposed content of the biodiversity gain information and biodiversity gain plan. The proposals were broadly supported, but it was suggested that:

-

more information should be required about future management of biodiversity in the biodiversity gain plan

-

the biodiversity gain information and biodiversity gain plan should make greater reference to existing industry guidance

-

we should use regulations and guidance to clarify the precise information requirements, or provide a checklist of any necessary supporting documents

-

intertidal developments should not be required to demonstrate delivery of on-site habitats, which are not usually ecologically feasible

-

more of the template is labelled as mandatory to reduce the likelihood of plans needing to be resubmitted with additional information

We will aim to address the points above in the final biodiversity gain plan template. We will be requiring that biodiversity gain information (in the form of a BNG Statement) is provided alongside the planning application before a biodiversity gain plan is then submitted and approved prior to commencement of development. We will also continue to remove duplication across BNG documents and aim to reduce the overall length of the template.

Some respondents raised concerns relating to the proposal that “on-site biodiversity gains should be secured for delivery within 12 months of the development being commenced or, where not possible, before occupation” and questioned whether this was reasonable and achievable for sites such as minerals sites, phased developments, or sites with complex engineering demands. We will take these observations into account as we draft final guidance wording. We intend for this part of the guidance to influence planning authorities’ application of conditions, planning obligations and conservation covenants rather than to be enforced as an inflexible rule itself.

5.2 Off-site biodiversity gains

Guidance on appropriate use of off-site biodiversity gains

We will implement our proposals and provide further guidance on what constitutes appropriate off-site biodiversity gains for a particular development.

We recognise the need to deliver strategic biodiversity improvements to support the restoration of functional ecosystems but also recognise the value of access to nature near developments for communities. Government will continue to incentivise a preference for on-site gains over off-site gains. There is one exception to this, intertidal developments, for which small on-site enhancements are often inappropriate. We will also incentivise local off-site provision in strategically significant locations through the biodiversity metric. We will keep this position, and the extent that BNG is contributing to off-site nature restoration, under review through our monitoring and evaluation of BNG in practice.

Securing sites for more than 30 years

Government intends to commence mandatory BNG with 30 years set as the minimum period for which biodiversity gain sites must be secured. As proposed in the consultation, this will not be reviewed before 2026 so that there is a reasonable amount of information available on the biodiversity gain market and potential impacts of a longer minimum duration.

Several respondents wanted to know what would happen after the 30-year period has passed. At the end of a 30-year biodiversity gain agreement, a landowner would likely be able to consider other available incentives to maintain or further enhance the site. We would hope that very few biodiversity gain sites are taken out of conservation management entirely at the end of their agreements. We therefore advise landowners to bear these factors in mind when offering their land for biodiversity gains. It might be possible for the increased biodiversity of the site to be taken as a new baseline and the land re-entered into the BNG market to deliver further habitat enhancements.

Additionally, we will consider the range of suggestions that we received for how to incentivise retention of biodiversity gains once gain sites’ legal agreements expire. These suggestions included:

-

tax incentives

-

securing longer term management through investment bonds or other financial instruments

-

allowing sale of new biodiversity units for new enhancements after the initial 30-year legal agreement ends

Staged sales

We propose that, where planned habitat enhancements have been achieved and evidence of this can be provided, further enhancements should be possible before the end of the existing legal agreement. For this to be permissible we would expect verification of the achievement of the first planned enhancement in terms of quantity, habitat type and condition. Any such subsequent enhancements will require an updated legal agreement which sets new goals. In updating the legal agreement, the duration must be extended so that it covers any remaining time on the initial agreement plus 30 years for the new enhancement.

5.3 The market for biodiversity units

Supply of units to the market

Two thirds of respondents supported our approach to who could supply the market for biodiversity units. As we proposed in the consultation, any landowners or managers will be able to create or enhance habitat for the purpose of selling biodiversity units, provided that they are able to meet the requirements of the policy, including additionality and register eligibility requirements, and demonstrate no significant adverse impacts on priority habitats. This includes local authorities, but they cannot direct buyers towards their land in preference over other suppliers to the market unless there are clear ecological justifications for doing so. Suppliers of biodiversity units will be able to sell to developers anywhere in England, provided that the use of those units is appropriate for the development in question and the distance between the development and the off-site habitat is properly accounted for in the biodiversity metric.

Allowing developers to sell excess biodiversity units

We asked whether developers who can exceed the biodiversity gain objective for a given development should be allowed to use or sell the excess biodiversity units as off-site gains for another development. The majority of respondents were supportive, but some did raise the concern that this approach could inadvertently make 10% the maximum gain at a national scale by redistributing any gains above this level.

We will allow developers to sell the excess biodiversity units as off-site gains for another development, provided that this excess gain is registered and that there is genuine additionality for the excess units sold. This means that these units should be delivered above and beyond the gains required by the original development to meet the mandatory BNG requirement and to make the development acceptable to the local planning authority. These ‘excess’ gains must be identified clearly as such in the original development’s biodiversity gain plan. We will keep this position under review and monitor whether this imposes an artificial ceiling on the gains achieved.

Government’s role in the market and tax

Government will not develop a centralised trading platform for biodiversity units or facilitate other roles which could be performed by the private sector or other third parties, such as brokering. We will detail in guidance the expectation that funds are held securely so that outcomes are secure in the long-term, but it will be for the buyer, seller, and any other parties to the agreement to agree payment terms. The price of units supplied by the off-site market will be determined through negotiations between the buyer and seller and are likely to vary by habitat type and location. Sellers must ensure that the price is sufficient to cover the costs of creating or enhancing the habitat, any necessary monitoring, and maintaining it for a minimum of 30 years.

Work is underway to provide guidance on the tax implications for habitat creation or enhancement. Biodiversity units will be subject to VAT when they are sold.

5.4 Habitat banking

Creation of habitat banks

As we proposed in the consultation, we consider habitat banking will enable delivery of larger, more strategic sites for nature. Habitat created or enhanced after 30 January 2020 will be eligible for registration and sale of the associated biodiversity gains, provided it meets the other criteria of the biodiversity gain site register. This date is the date that the Environment Bill was re-introduced into Parliament; it has been selected as we consider it the point at which landowners could be reasonably certain of mandatory BNG being implemented. We therefore want to make enhancements before this date ineligible, as we think they are unlikely to have been undertaken for mandatory BNG.

Habitat created or enhanced before this date will need to be re-baselined using the statutory biodiversity metric from 30 January 2020 to ensure that only biodiversity units created or enhanced after this date can be sold.

Time limit on habitat banks

We asked whether there should be a time limit on how long biodiversity units can be banked before they are allocated to a development. We do not intend to set a time limit on how long biodiversity units can be banked before they are allocated to a development. A habitat bank would need to be able to record and provide suitable monitoring information to demonstrate that the initial works to create or enhance the habitat had been completed by a given date if they wish to take advantage of the ‘advanced creation’ function in the metric.

The whole land area within a habitat bank need not be secured by a legal agreement for the minimum 30-year period prior to the first sale of units to a developer, although we would not prevent a landowner or manager from doing this if they chose to. When, however, biodiversity units are sold to a developer, the associated parcel of land within the habitat bank would need to be secured by a legal agreement and registered prior to approval of the biodiversity gain plan for the associated development.

5.5 The biodiversity gain site register

The UK Government will appoint Natural England as the Biodiversity Gain Site Register Operator, responsible for establishing and maintaining the register. The core purpose of the biodiversity gain site register is to record allocations of off-site biodiversity gains to developments and make this information publicly available. The register will not act as a marketplace platform for buying or selling units, nor will it assess the ecological suitability or additionality of proposals. Natural England aim to open the register for new biodiversity gain sites by November 2023. We will set an achievable determination time for applications to the register in consultation with Natural England. This is likely to be around 6 weeks.

Government does not intend to mandate registration of on-site gains on the biodiversity gain site register because this would duplicate information submitted to and held by local planning authorities in planning applications which are already in the public domain. However, we agree that both on-site and off-site information on biodiversity gains should be accessible in one place and so are exploring how on-site information can be extracted from planning permissions and published on the register.

It will be the responsibility of local planning authorities or responsible bodies, when creating agreements that secure delivery of biodiversity gains, to assure themselves that the habitat enhancements proposed are achievable. This will happen before registration of a gain site – a binding legal agreement is a pre-requisite to registration. Since landowners will be legally obliged to deliver the outcomes they agree to in the legal agreement, it is also in their interest to make sure the planned enhancement is achievable.

Government will publish guidance on what LPAs and responsible bodies should take into consideration when creating legal agreements to secure biodiversity gains. This will cover things such as checking that there are no conflicts with other interests on the land (such as shooting or mineral working rights), checking that any necessary permissions have been obtained (such as planning permission, felling licences) and consulting aerodrome safeguarding authorities where applicable.

Register eligibility criteria and information requirements

We will refine the proposed eligibility criteria to ensure that the register does not duplicate or conflict with other parts of the process and that the criteria are fit for the purpose of the register. We will also address concerns that the proposed criteria would not work well for habitat banks and will provide for the register to allow the registration of gain sites separately from allocation of biodiversity gains to development.

Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan

We asked whether we should require habitat management and monitoring plans (HMMP) to be included on the register. 95% of respondents agreed that we should. We will require that habitat management and monitoring information is provided as part of site registration. Habitat management plans must be secured by the legal agreement which secures the gain site. We are working with Natural England to develop a HMMP template which is streamlined but robust, and will provide consistency for developers, ecologists, and LPAs.

Fees and fines

We asked whether the register operator should charge a fee for applications to register biodiversity gain sites. 92% of respondents agreed with this proposal. Government will provide for the register operator to charge a fee for applications. The fee will be set to achieve cost recovery, so that all the register costs are fully covered by application fees. We are working with Natural England to determine a reasonable fee and are considering different options including a flat fee or one related to biodiversity gain site size. As a guide, we would expect a fee to be between £100 and £1,000.

Government will give the register operator powers to issue financial penalties to help ensure the register contains accurate information. The register operator will have discretion over whether to apply a fine. Fraud legislation may also apply in some cases.

Appeals

We will allow the applicant to appeal where an application for registration of a gain site is refused by the register operator. We will set a maximum time after an application is refused within which an appeal must be made. Applicants will also be able to appeal against; the rejection of an application to amend an entry on the register, an amendment the register operator made to information on a gain site on the register, the removal of a gain site from the register, or the rejection of an application to record allocation of habitat enhancements on the register. An applicant who receives a fine from the register operator will also be able to appeal against this. A fee may be charged for appeals, in keeping with the principle of cost recovery. Government does not intend to provide for an appeal process for third parties, but we will consider options for allowing third parties to contact Natural England to raise concerns about the registration process itself. Information on registered gain sites will be in the public domain and the register will detail the relevant enforcement body for each gain site.

5.6 Additionality

We asked about 5 separate proposals (on page 72 of the consultation) about additionality which were broadly supported by respondents. We intend to implement these five proposals.

The proposals included a statement that mitigation and compensation for protected species and protected sites can be counted within a development’s BNG calculation. The consultation document stated that: “at least 10% of the gain should be delivered through separate activities which are not required to mitigate or compensate for protected species impacts”. This has been interpreted in different ways. To clarify, this means that at least 10% of the total (110+%) post-development biodiversity score should be from measures which are not undertaken to address impacts on protected species or protected sites (e.g. nutrient mitigation). For example, if a development has a baseline score of 10 biodiversity units and needs to achieve a score of 11 units, at least 1 unit should come from separate activities (such as an onsite habitat or the wider market for biodiversity units).

Enhancements in statutory protected sites for nature conservation

We will not be making an exemption for development on statutory sites designated for nature conservation. We asked whether the non-designated features or areas of statutory protected sites, Local Wildlife Sites and Local Nature Reserves should be eligible for enhancement through BNG. Responses were generally supportive, but in recognition of the risk of ‘cost shifting’ raised by some academic respondents, we will be providing guidance on the circumstances in which statutory protected sites can be enhanced for BNG and will keep this position under review through policy evaluation.

In response to broad support for the proposal, we will state that all habitats in the intertidal zone, including designated features of protected sites, or a short distance (to be confirmed, but no more than 2 kilometres) above the high-water mark, would be eligible for enhancement for BNG. Any compensation that a development is delivering in meeting wider statutory protections may be counted towards that development’s BNG. This would be subject to any relevant approvals for the enhancement and only permitted where the proposals do not risk harming designated species or features.

Stacking of payments for environmental services

We asked whether payments for biodiversity units should be combined with other payments for environment services from the same parcel of land (‘stacking’). We will publish guidance alongside this response on how BNG and nutrient mitigation can be stacked and how they can be combined with other schemes. This first phase of guidance will run until March 2025.

Land managers will be able to sell both biodiversity units and nutrient credits from the same nature-based intervention, for example the creation or enhancement of a wetland or a woodland on the same parcel of land. Land managers should not sell credits for other ecosystem services (such as carbon credits) from the same nature-based intervention if they are also selling biodiversity units and/or nutrient credits.

Biodiversity units may be generated on top of an existing obligation or grant payment if the land manager is able to further enhance a habitat and can establish a clear and verifiable baseline from what the existing payment or obligation has achieved. See also the ‘Staged sales’ section earlier in Part 3.

5.7 Statutory biodiversity credits

Natural England will sell statutory biodiversity credits on behalf of the Secretary of State. Credit sales will be facilitated by an accessible and user-friendly digital sales platform which is currently being developed and tested.

Further guidance on how the need for credits should be determined and demonstrated in developer’s gain plans will be published during the transition period to support decision-making by developers and planning authorities.

We aim to minimise the use of statutory biodiversity credits and phase them out once the biodiversity unit market has matured.

Credit price

An indicative credit price will be published 6 months in advance of BNG becoming mandatory. The price will be set to be intentionally uncompetitive with the market. We are assessing whether to vary the price by habitat type. We will review the price at 6-monthly intervals in response to market data once the mandatory requirement is in place. Price changes will be indicated well in advance to allow developers to plan ahead. We will be providing policy guidance on when a developer will be able to access the credit scheme to ensure that they remain a last resort.

Credit investment

As proposed, revenue from credit sales will be invested by Natural England on behalf of Defra’s Secretary of State in strategic habitat creation and enhancement projects which deliver long-term environmental benefits and an overall net gain in England.

For practical reasons, we do not propose to make a direct, traceable link between an individual development that has purchased credits and specific sites that have received that investment. For transparency, the Secretary of State will publish an annual report detailing the total payments received by the credit scheme and how those payments have been used. Credit investment will only be used for the purposes set out in the Environment Act 2021.

Statutory biodiversity credits can only be sold by the Secretary of State, and it will not be possible for local variations of these to be sold (for example, local tariff schemes) for the purpose of meeting the mandatory requirement.

5.8 Reporting, evaluation, and monitoring

We recognise the concern raised by some respondents that additional training and capacity will be needed for effective enforcement by all planning authorities. The register operator will not have planning enforcement powers and planning authorities will need to ensure that gains are appropriately secured where necessary to enable effective enforcement. Gains can be secured via planning conditions, planning obligations or conservation covenants (or a combination of these methods). We intend to make this clear through guidance and training. For gains that are secured with conservation covenants, we expect costs for monitoring and enforcement activities to be reflected in the price of biodiversity units. We will define the threshold for significant on-site gains, which will need to be explicitly secured through the mechanisms set out above, in guidance and are currently minded to set a definition according to habitat area and distinctiveness.

The planning enforcement regime will be the principal way of enforcing delivery of BNG. We will review the role of guidance in supporting when enforcement action can be taken, to clarify that a failure to deliver promised environmental enhancements can justify enforcement action at a planning authority’s discretion. We will also work with the Department for Levelling Up, Communities and Housing on any future measures and guidance that could support enforcement of BNG.

We noted in the consultation that clear and proportionate monitoring proposals for enhanced habitats will be essential to facilitate wider policy evaluation and enforcement. We will make it clear that planning authorities should set specific and proportionate monitoring requirements as part of planning conditions and obligations used to secure off-site or significant on-site habitat enhancements. Some respondents suggested changes to the monitoring frequencies we suggested and we will take these suggestions into account as we finalise guidance.

Conservation covenants

Local planning authorities and other eligible organisations can apply to become responsible bodies and use conservation covenants which have been designed for the purpose of securing, and where necessary enforcing, positive (and restrictive) land management obligations. Conservation covenants bind the land which means they will apply to new landowners if the land is sold.

Prospective responsible bodies will be able to apply to Defra for designation from early 2023 and successful applicants will be able to create conservation covenants thereafter. We will publish guidance on what should be included in a conservation covenant or planning obligation which secures biodiversity gains for the purpose of BNG.

Earned recognition

We asked whether accreditation or earned recognition has potential to help focus enforcement and scrutiny of BNG assessments, reporting and monitoring. We will continue to explore the potential for earned recognition with stakeholders and monitor practice to establish whether a higher competency or accreditation bar is needed for components of the BNG approach.

In response to suggestions from respondents that the independence of ecologists is important, we will also continue to consider whether reforms are needed to the procurement or regulation of ecological expertise. We do not think that introducing structural changes to the ecology and planning authority sectors would be sensible in the immediate future while BNG and wider changes are being implemented.

Policy level evaluation

We asked whether proposals for policy-level reporting and evaluation seemed sufficient and achievable. We will consider the responses provided as we continue to develop our monitoring and evaluation framework for mandatory BNG.

Biodiversity reports

We asked whether there was any additional data that should be included in biodiversity reports required by the strengthened biodiversity duty on public authorities introduced by the Environment Act, and whether there was anything that should be removed. We will consider the suggestions provided for inclusion in reporting requirements, along with the scope to reduce duplication across reporting templates and products.

5.9 Local planning authorities (LPAs)

We announced £4.18 million for LPAs in January 2022. We will be providing further funding of up to £16.71 million for LPAs to prepare for mandatory BNG between now and November 2023. This will be followed by further new burdens funding following commencement of the requirement in November 2023. As set out in the original BNG impact assessment, our assessment remains that there is an additional burden created by the reforms, primarily in the form of demand for additional ecologist and monitoring resources.

We are continuing to provide support through the Planning Advisory Service to local planning authorities to implement biodiversity net gain.

We understand there is a need for further clarification about how local planning authorities should apply existing BNG policy, in both the NPPF and policies contained in local plans, to set out expected interactions once the mandatory net gain requirement comes into force in November 2023. We will consult on any changes required to national policy in due course.

6. Annex A – Detailed summary of consultation responses

6.1 Part 1: defining the scope of the BNG requirement for Town and Country Planning Act 1990 development

Exemptions

Question 1: Do you agree with our proposal to exempt development which falls below a de minimis threshold from the BNG requirement? a) for area-based habitat b) for linear habitat (hedgerows, lines of trees, and watercourses)

69% of respondents were supportive of exempting development which falls below a de minimis threshold from the biodiversity net gain requirement for area-based habitat; 21% were unsupportive.

Those supportive fell into the following categories:

- 2 metres squared – 7%

- 5 metres squared – 8%

- 10 metres squared – 10%

- 20 metres squared – 9%

- 50 metres squared – 22%

- Other threshold – 13%

65% of respondents were supportive of exempting development which falls below a de minimis threshold from the BNG requirement for linear habitat (hedgerows, lines of trees, and watercourses); 25% were unsupportive. Those supportive fell into the following categories:

- 2m – 10%

- 5m – 15%

- 10m – 12%

- 20m – 8%

- 50m – 10%

- Other threshold – 10%

Question 2: Do you agree with our proposal to exempt householder applications from the BNG requirement?

55% agreed with the proposal to exempt householder applications from the BNG requirement. 23% disagreed, 15% said other and 7% said they did not know. 14% said it was proportionate to exempt householder applications and 7% said this would lift a burden on LPAs.

A number of respondents observed that, whilst an exemption is proportionate, it would be valuable for public biodiversity awareness and engagement with nature to be able to apply some small fee or small mitigation requirement.

Question 3: Do you agree with our proposal to exempt change of use applications from the BNG requirement?

39% of respondents were supportive of the proposal to exempt change of use applications, while 40% were unsupportive. 22% considered that change of use can have big impacts. Those that supported the exemption of change of use said that the change would usually be towards residential, is unlikely to have biodiversity impacts and would not justify the overwhelming amount of additional work that this would generate for LPAs. One said changes of use should not impact habitats generally, however a specific exemption may not be needed if a de minimis limit is introduced.

Question 4: Do you think developments which are undertaken exclusively for mandatory biodiversity gains should be exempt from the mandatory net gain requirement?

48% of respondents agreed that developments undertaken exclusively for mandatory BNG should be exempt and 24% agreed with this for some other environmental mitigation purpose. 13% were unsupportive of these being exempt. One LPA said that to ensure this applies to legitimate BNG developments, all exempted sites must meet the criteria of registered BNG sites.

There was some concern that other “wider environmental mitigation”, such as flood mitigation measures may in itself result in a biodiversity net loss and so a clear definition in guidance or regulations would be needed.

Question 5: Do you think self-builds and custom housebuilding developments should be exempt from the mandatory net gain requirement?

8% of respondents thought that self-builds and custom housebuilding developments should be exempt from the mandatory net gain requirement; 76% of respondents did not think they should be exempt, with the remainder unsure or answered ‘other’. Those that were supportive said self builds already aimed for high environmental standards (2%).

15% were concerned that self-builds and custom housebuilding developments could be large in scale and greater than single houses. One respondent said exempting this group would put small builders at a disadvantage who do not meet the custom build definition.

Question 6: Do you agree with our proposal not to exempt brownfield sites, based on the rationale set out above?

86% of respondents agreed with the proposal not to exempt brownfield sites from the net gain requirements. 6% did not agree and 7% said ‘other’. 29% of respondents were concerned about an exemption as brownfield sites can be biodiverse and exempting them may result in significant loss. A developer suggested it could impact on low-cost housing which is built in areas experiencing high levels of deprivation which attract lower land values and are of more marginal viability, as these sites would have to purchase offsite units to achieve net gains.

Question 7: Do you agree with our proposal not to exempt temporary applications from the BNG requirement?

80% of respondents agreed with the proposal not to exempt temporary applications; 3% disagreed and 7% answered ‘other’. Those who agreed stated that temporary applications may cover long periods of time or lead to permanent changes. One respondent said such permissions are frequently then followed by applications for permanent permission and others pointed out that exempting temporary applications could create a loophole by allowing for biodiversity losses which then cannot be accounted for in the baseline of subsequent permanent applications. Those who disagreed mentioned that it could cause undue burden on the delivery of infrastructure as temporary works are essential for the expedient delivery of infrastructure.

Question 8: Do you agree with our proposal not to exempt developments which would be permitted development but are not on account of their location in conservation areas, such as in areas of outstanding natural beauty or national parks?

83% agreed with our proposal not to exempt developments which would be permitted development but are not on account of their location in conservation areas, such as in areas of outstanding natural beauty or national parks. 7% disagreed.

A planning authority explained that the cumulative impact of applications in such areas could have a long-term major impact which is why permitted development rights have been limited in these areas in the first place. A planning authority against the proposal said it seems unfair that development schemes in these areas should have to deliver biodiversity gains when they elsewise would not.

Question 9: Are there any further development types which have not been considered above or in the previous net gain consultation, but which should be exempt from the BNG requirement or be subject to a modified requirement?

12% said there were further development types which should be exempt from the BNG requirement, including:

-

redeveloping existing buildings

-

creation of energy provision schemes

-

waterway restoration projects

-

agricultural buildings

-

mineral developments

-

telecommunication masts, affordable housing

-

amendments to existing planning permissions

-

flood and drainage infrastructure

-

community charity projects

-

affordable homes

-

walking and cycling routes

8% said there were further development types which should be subject to a modified requirement, including:

-

development located in proximity of airfields

-

defence projects where there is a risk of explosives

-

permitted development undertaken by utility companies

-

SANGs (suitable alternative natural greenspaces)

-

minerals development

-

solar development

-

campsites

47% said there were no further development types that should be exempt or be subject to a modified requirement.

Development within statutory designated sites for nature conservation

Question 10: Do you agree with our proposal not to exempt development within statutory designated sites for nature conservation from the biodiversity gain requirement?

91% agreed with our proposal not to exempt development within statutory designated sites for nature conservation; 3% were unsupportive and one respondent highlighted that “these sites would be excluded from BNG calculations on the basis that works need to represent additionality.” However, most respondents asked for strengthened guidance and communication on the mitigation hierarchy. Some respondents said that the BNG requirement should be greater than 10% in designated sites.

Irreplaceable habitat

Question 11: Do you agree with the stated proposals for development (or component parts of a development) on irreplaceable habitats, specifically:

a) The exclusion of such development from the quantitative mandatory biodiversity gain objective?

71% of respondents agreed with our proposal to exclude such developments from the quantitative mandatory biodiversity gain objective; 17% disagreed. Some stated that no development should take place on irreplaceable habitats and that no amount of mitigation can compensate for its destruction, nor re-create what has been removed. 2% of supportive respondents stated that the metric should take account of indirect impacts on irreplaceable habitats.

b) The inclusion of a requirement to submit a version of a biodiversity gain plan for development (or component parts of a development) on irreplaceable habitats to increase proposal transparency?

81% of respondents agreed with our proposal to include a requirement to submit a version of a biodiversity gain plan for development on irreplaceable habitats to increase proposal transparency; 11% disagreed, with some saying it would be an additional admin burden. 3% of respondents thought that an option to provide a biodiversity gain plan for development on irreplaceable habitats would be at odds with imperative to avoid irreplaceable habitat loss. 2% of respondents noted that a separate document should be required and recorded in a version of the biodiversity gain site register for irreplaceable habitats.

c) Where there are no negative impacts to irreplaceable habitat, to allow use of the biodiversity metric to calculate the value of enhancements of irreplaceable habitat?

78% of respondents agreed with our proposal that, where there are no negative impacts on irreplaceable habitat, we should allow the use of the biodiversity metric to calculate the value of enhancements of irreplaceable habitat; 2% disagreed, most stating that it should be kept out of net gain considerations.

Overall, 2% of supportive respondents specified that indirect impacts should be considered. A Local Nature Partnership said that the definition of impacts to irreplaceable habitats must be defined, and highlighted that landscaping, drainage, and recreational footpaths are often not considered by developers to be direct impacts. 2% of respondents who agreed with proposal noted that the biodiversity metric should also be supported by further evidence and expertise.

d) To use the powers in BNG legislation to set out a definition of irreplaceable habitat, which would be supported by guidance on interpretation?

84% of respondents agreed with our proposal to use the powers in BNG legislation to set out a definition of irreplaceable habitat, supported by guidance on interpretation; 6% disagreed, some noting that existing NPPF definition is sufficient. Some stated that the tools for BNG should not become the definitive position as to what is and isn’t irreplaceable, and that any new definition must be updated in the NPPF.

Some respondents stated that the definition of irreplaceable habitat should also include species data, not just habitat class. Several respondents asked that definitions are aligned with the UKHab definitions of habitats. 4% of respondents noted that local context should be considered and a ‘one size fits all’ definition is not appropriate.

e) The provision of guidance on what constitutes irreplaceable habitat to support the formation of bespoke compensation agreements?

83% of respondents agreed with the proposal for the provision of guidance on what constitutes irreplaceable habitat to support the formation of bespoke compensation agreements. 4% of respondents who agreed with the proposal noted the aim should be to minimise development on irreplaceable habitat. 9% of respondents disagreed, some stating that an irreplaceable habitat cannot be replaced and therefore there can be no adequate compensation for its loss.

6.2 Part 2: What development should be in scope of a net gain policy? Applying the biodiversity gain objective to different types of development

Phased development and development subject to subsequent applications

Question 12: Do you agree with our proposed approach that applications for outline planning permission or permissions which have the effect of permitting development in phases should be subject to a condition which requires approval of a biodiversity gain plan prior to commencement of each phase?

71% of respondents agreed with the proposal, 7% disagreed with the proposal and 4% of respondents answered ‘don’t know’. 10% of respondents did however have concerns about delivering BNG over longer periods with phased projects which could take years to complete. It was suggested that any phase-level revisions or additions to the original biodiversity gain plan should be submitted to the local authority. 11% of respondents specifically welcomed the proposal for a strategic approach from the start of the process. 3% of respondents noted that flexibility is needed to be built in to allow phases to change if needed as it is currently done with outline planning submissions.

7% of respondents supported frontloading of BNG and suggested that BNG could begin to be delivered pre-commencement. Some respondents raised concerns over how front-loading the delivery of biodiversity gains may impact the viability of schemes. 2% of respondents had questions about how best BNG could be secured (for example, through S106 vs conditions) and 2% of respondents noted the need for further guidance and model conditions.

Question 13: Do you agree with the proposals for how phased development, variation applications and minerals permissions would be treated?

53% of respondents agreed with the proposals for how phased development, variation applications and minerals permissions would be treated. 13% disagreed and 19% responded ‘don’t know’. 6% of respondents explicitly stated that Review of Old Minerals Permissions (ROMPs) should not be excluded from BNG requirements. They highlighted that there is a significant potential for habitat creation and enhancement associated with ROMPs, and that some had in effect been rewilded due to the lack of human disturbance and reactivation of these sites could lead to a permanent or uncompensated loss of biodiversity.

4% of respondents expressed concern that there is danger that the approach to mineral applications may not maximise the amount of BNG that could be delivered. On respondent said that “the regime needs to reflect that different rate(s) of extraction from that anticipated at the application stage can extend extraction periods and delay restoration and net gain measures and there needs to be a way of increasing or decreasing the net gain figure to reflect these changes.”

For Section 73 applications, most respondents agreed that original baseline should apply and Section 73 variation applications should be bound by the net gain condition. However, they have raised some concerns including:

-

about variations of an older permission that was not subject to BNG and where the baseline may not be verifiable;

-

what the mechanism will be for comparing the biodiversity value of a previously approved scheme with a varied scheme;

-

clarity around who will scrutinise applications for permission under section 73 to determine whether they affect the post-development ‘biodiversity value’ of the site; and

-

that Non Material Amendment applications should be required to have to re-assess the net gain against the original baseline given they are minor and non-material.

A professional body also noted challenges in introducing the BNG requirement to planning permissions via Section 73 where the earlier grant of permission was not subject to the mandatory BNG condition.

Small sites

Question 14: Do you agree that a small sites metric might help to reduce any time and cost burdens introduced by the biodiversity gain condition?

66% were supportive of the use of the small sites metric and that it can reduce time and cost burdens of measuring net gains. 4% of respondents said that a separate approach, and metric, is required for small sites to make sure it is proportionate compared to larger schemes. In comparison, 6% of respondents suggested that there should not be a separate approach for small sites and did not see this as an additional burden. 20% of respondents did not feel that the small sites metric would help reduce any time or cost burdens, and some respondents felt that, for simplicity, one metric should be applied for both large and small developments.

Question 15: Do you think a slightly extended transition period for small sites beyond the general 2- year period would be appropriate and helpful?

56% of respondents said that there should not be an extension to the transition period for small sites. Some suggested that longer transition periods lead to more biodiversity damage (8%). The majority of those that were unsupportive of the proposal said that the requirement for small sites to achieve BNG should happen as soon as possible (18%) and that the knowledge and guidance already exists to successfully implement this (3%). 25% of respondents were supportive of an extension to the transition period for small sites. 76 of those said that they would prefer a 12-month extension. Fewer respondents that were supportive (40) said they would prefer a 6-month extension.

Question 16: Are there any additional process simplifications (beyond a small sites metric and a slightly extended transition period) that you feel would be helpful in reducing the burden for developers of small sites?

Respondents that were unsupportive said that legislation and guidance need to prevent larger sites being split into smaller plots to benefit from a simplified small sites metric. Additionally, some respondents said that the small sites metric does not appear to offer any time saving compared to the full biodiversity metric.

Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs)

Question 17: Are any targeted exemptions (other than that for irreplaceable habitat), reduced BNG objectives, or other modified requirements necessary for the application of the BNG requirement to NSIPs?

65% of respondents agreed that there should be no other targeted exemptions.11% said that further exemptions were needed, and the remainder did not know or answered ‘other’. 6% of respondents said that NSIPs should deliver more than the 10% minimum net gain. Some suggested there needed to be a level playing field between NSIPs and TCPA applications and others said NSIPs should set the example for others to follow. The NFU said it was important to recognise that not all NSIPs projects will result in permanent habitat loss. For example, any hedgerows or other habitat features removed to allow cables to be laid would be reinstated on completion of the scheme.

Question 18: Do you agree that the above approach is appropriate for setting out the BNG requirement for NSIPs?

38% were supportive of the approach. 17% disagreed and the remainder did not know or answered ‘other’. IEMA supports at least 10% net gain for NSIPs because of their larger impacts and said a consistent approach to the amount of net gain required will reduce complexity for developers and planners and support effective implementation.

Question 19: Do you consider that the November 2025 is an appropriate date from which NSIPs accepted for examination will be subject to the BNG requirement?

44% of respondents thought the BNG requirement for NSIPs should be brought into effect sooner, including 5% of respondents that thought that the requirement should be implemented at the same time as the requirement for TCPA developments. Several respondents explained that some NSIPs already deliver BNG or are working towards it. One planning authority said that “NSIPs should be in a better position than most to deliver 10% BNG from 2023”.

21% of respondents supported our proposal to bring the BNG requirement for NSIPs into effect by November 2025. One planning authority said that due to the significant lead in times for NSIP’s, 2025 is considered the earliest date that it would be possible to implement BNG.1% of respondents thought the BNG requirement for NSIPs should be brought into effect later. This included several responses from the development industry who referred to the long lead in times for DCO applications. The remainder of respondents stated that they did not know or answered “other”.

Question 20: Do you agree that a project’s acceptance for examination is a suitable threshold upon which to set transition arrangements?

42% responded ‘don’t know’; 31% of respondents supported the use of a project’s acceptance for examination as the threshold; 17% disagreed as too late in the process. A key reason described by 2% of respondents (including several planning authorities) was that after an NSIP is accepted for examination there is limited scope to change the application, so it would be too late to introduce new BNG requirements. Suggestions from respondents for alternative thresholds included: application submission to the Planning Inspectorate (PINS) and, project registration with PINS at the pre-application stage.

Question 21: Would you be supportive of an approach which facilitates delivery of BNG using existing landholdings by requiring a lighter-touch registration process, whilst maintaining transparency?

40% of respondents were unsupportive of a lighter-touch registration process for existing landholdings; 25% of respondents answered, ‘don’t know’ or ‘other’. Many respondents (13%) raised concerns over transparency, oversight, or enforcement under a lighter-touch approach. 12% of respondents expressed a preference for a consistent approach, with all mitigation sites to be registered and recorded in the same way. Some respondents raised concern that this approach could reduce the certainty that BNGs delivered on existing landholdings are additional.

34% of respondents supported the lighter-tough registration process and 4% thought it could deliver better results. For example, one utilities company stated that it would allow them to manage and maintain BNG site more strategically. A planning authority explained that public bodies could have large landholdings in strategically important locations, so this approach could enhance the ecological connectivity.

Question 22: Do you consider that this broad ‘biodiversity gain plan’ approach would work in relation to NSIPs?

61% supported the broad ‘biodiversity gain plan’ for NSIPs. Several thought it is sensible to use a broadly comparable approach with development granted permission under the TCPA. Several (3%) commented on the importance of removing the incentive for landowners and developers to clear habitats in advance of ecological assessments. Our proposal to use an earlier habitat value as the baseline where there has been recent habitat degradation was supported.

8% were unsupportive of the broad ‘biodiversity gain plan’ for NSIPs for several reasons. Two respondents thought NSIPs should have more ambitious BNG requirements. One respondent disagreed due to uncertainty on whether and how compensation sites could be excluded from the development area of NSIPs. Other respondents thought the entire site including compensation areas should be subject to net gain requirements. 30% answered ‘don’t know’ or ‘other’.

Question 23: Should there be a distinction made for NSIPs between on-site habitats (which are subject to the BNG percentage) and those habitats within the development boundary which are included solely for environmental mitigation (which could be treated as off-site enhancement areas without their own gain objective)?

35% supported a distinction between on-site habitats and environmental mitigation habitats within the development boundary. Several stressed that mitigation habitats should only be distinguished if they are not impacted by the development.

28% thought there should not be a distinction. The main reason was to ensure that impacts to all habitats on site, including mitigation habitats, are captured in the site’s baseline metric so that any uplift is truly additional. 3% of respondents, including the Environment Agency, thought making a distinction could add confusion, and lead to loopholes or enforcement issues.

Some (9%) said environmental mitigation sites can occur on some other developments (not just NSIPs), and that there should be a consistent approach across TCPA and NSIPs developments. 37% did not know if there should be a distinction.

Question 24: Is there any NSIP-specific information that the Examining Authority, or the relevant Secretary of State, would need to see in a biodiversity gain plan to determine the adequacy of an applicant’s plans to deliver net gain (beyond that sought in the draft biodiversity gain plan template at Annex B)?

54% did not know if any NSIP-specific information would be needed. Many respondents wanted further consultation on what is required for NSIPs in the biodiversity gain plan, when more detail on the approach for NSIPs is available.

18% thought that no additional NSIP-specific information is needed. 24% wanted NSIP-specific information. Suggestions include how the mitigation hierarchy has been followed, irreplaceable habitats details, location, and impact on statutory sites, how the plan aligns with LNRS, and any relevant wider-scale strategies for NSIPs, impact on connectivity, habitat maps pre- and post-development, delivery, and management plan, how maintenance of the infrastructure will be carried out to avoid and minimise impact to biodiversity, detail on interactions with other planning documents.

Question 25: Do you think that 30 years is an appropriate minimum duration for securing off-site biodiversity gains allocated to NSIPs?

42% were supportive of a 30-year minimum for securing off-site biodiversity gains. This includes 30% who thought it should be reviewed after it has been put in practice, and that the biodiversity gain markets should be evaluated. 31% thought the minimum duration should be longer than 30 years. 3% thought it should be shorter. 18% answered ‘don’t know’.

Question 26: Are further powers or other measures needed to enable, or manage the impacts of, compulsory acquisition for net gain?

21% thought no extra powers or measures are needed. Many preferred developers to meet the net gain requirements on-site, or through off-site units. 5% of respondents said compulsory acquisition should be a last resort. Some said that acquisition for BNG could undermine the market for biodiversity units.

9% thought extra powers or measures are needed. Respondents wanted clarification in the Planning Act 2008 to enable CPOs to be made specifically for BNG.

3% suggested the following extra powers or measures to manage impacts of compulsory acquisition:

-

guidance on when compulsory acquisition would be appropriate for the purposes of BNG (for example, when the public interest test would be met)

-

ensuring the mitigation hierarchy is followed (for example, only takes place after other options have been exhausted)

-

ensuring potential acquisition sites are assessed to check they are suitable, and to check for any impacts from the NSIP development on the site

-

ensuring compulsory acquisition of land is focussed on land that is of strategic value in line with relevant local policies (for example LNRS)

13% thought extra powers or measures are needed to both enable and manage impact of compulsory acquisition. 46% answered ‘don’t know’.

Question 27: Is any guidance or other support required to ensure that schemes which straddle onshore and offshore regimes are able to deliver BNG effectively?

43% of respondents wanted guidance or support for schemes which straddle onshore and offshore regimes. 18% of respondents said guidance should cover interactions between marine, intertidal and onshore development for BNG.

Several respondents (3%) thought guidance and clarity would be required on the remits of responsible organisations such as LPAs and the Marine Management Organisation (MMO). Other responses highlighted the importance of coordination and joint engagement for consistent guidance and to avoid contradictory advice. 3% of respondents wanted a range of experts involved in the development of guidance and advice in this area.

2% of respondents thought that no more guidance or support is required, and the remainder of respondents answered ‘don’t know’.

6.3 Part 3: What development should be in scope of a net gain policy? How the mandatory BNG requirement will work for Town and Country Planning Act 1990 development

Biodiversity gain plan

Question 28a: Do you agree with the proposed content of the biodiversity gain information and biodiversity gain plan?

49% of respondents agreed with the proposed content of the biodiversity gain information and biodiversity gain plan. 17% replied that they did not agree, while 7% answered ‘don’t know’.

9% of respondents said the information requirements for biodiversity gain information and the biodiversity gain plan should be set out in regulations and guidance to ensure consistency and clarity. 4% of respondents believed that there is some content missing from the biodiversity gain information and biodiversity gain plan. Suggestions included that the biodiversity gain information and biodiversity gain plan should include steps taken to avoid, mitigate and compensate biodiversity loss. In the biodiversity gain plan it was suggested that more information should be required about future management of biodiversity.

Other suggestions include:

- a requirement for more information in the biodiversity gain plan about how development will avoid damage to existing habitat as far as possible

- the submission of maps and plans must be mandatory. This includes habitat condition scores, with a standardised format of a baseline habitat map and a masterplan map which presents all biodiversity enhancements