Decision rationale and sale impact analysis for a change of ownership of Channel 4

Updated 18 July 2022

Introduction

1. The Channel Four Television Corporation (C4C) is a self-financing public corporation which is publicly owned but commercially run. C4C is part of the UK’s vibrant public service broadcasting (PSB) family, and has played a valuable role economically, socially and culturally in the 40 years since its inception. These contributions have significant synergies with supporting the government’s wider strategic aims for the creative economy. This includes its support for the independent production sector; its specific focus on producing content for audiences that are not otherwise well-served by other broadcasters, including diverse and young audiences; and in more recent years, it has increased its focus on support for the creative economy outside London, through its physical footprint outside London and through targets to increase commissioning from producers based outside the M25.

2. The broadcasting landscape has evolved radically, and is continuing to do so, with the growth of online streaming platforms, changing viewing habits and increased competition from well-funded global players. Now is an appropriate time to explore ways to ensure the future long-term sustainability of a C4C that continues to contribute economic and social value across the UK.

3. Whilst all broadcasters are having to respond to these changes, C4C is more constrained than other linear TV broadcasters as a result of its current ownership and operating model. Under the current borrowing limits set out in legislation and as a publicly owned statutory corporation with no shares, C4C has restricted access to debt capital and no ability to raise equity capital by issuing shares. This means its ability to invest in content and technology — and compete with others in the market — is more limited than its privately owned rivals. Its ability to diversify its income to improve its resilience is also limited due to the publisher-broadcaster restriction. This restriction, which is set in legislation and does not apply to any other broadcaster, effectively stops C4C from making its own content to show on its main channel and generating new intellectual property for subsequent sales worldwide. This means C4C is currently reliant on advertising revenues which are cyclical in nature and, in the case of linear TV advertising, are also in structural decline.

4. In exploring the future of C4C, the government wants to ensure that the broadcaster remains financially sustainable over the long term and that its economic and social contribution continues to be significant. The government aims to underpin C4C’s financial sustainability through greater revenue diversification and access to capital, without placing undue risk or burden on the public sector finances, especially at a time of constraints and pressures on the public purse. Any intervention needs to facilitate the continued economic contribution of C4C to the UK, and the provision of a broad range of high-quality, diverse programming that demonstrates innovation, experimentation and creativity, is distinctive, educational and appeals to the tastes and interests of a culturally diverse society in the UK for decades to come.

5. We have considered a wide range of different options, outlined in more depth later, to meet these aims. Following extensive consideration of these options, the government believes that private ownership, when accompanied by the removal of the publisher-broadcaster restriction, is the best way to meet these aims, and that the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks. Having significantly increased access to capital, and the ability to own and sell its own content will give C4C the best range of tools to accelerate and unleash its potential in a rapidly changing media landscape.

6. Predicting the specific strategic choices C4C will make under new ownership at this stage is difficult, although it could be expected that a new owner would take an active approach to supporting C4C’s growth and sustainability. It should have a broader range of tools to facilitate this, in a more agile way, than is available to C4C under public ownership.

7. The government will look to mitigate any risks to C4C’s economic, social and cultural contributions through complementing the new opportunities and investment facilitated by a change of ownership of C4C with continued government support for the creative economy. The government will look to use some of the proceeds from the sale of Channel 4 to deliver a new creative dividend for the sector. The government will also consider funding for the creative industries in the round at the next Spending Review. There will also be ongoing requirements in C4C’s licence and remit to reduce any possible negative economic and social impacts of the intervention.

8. Following advice from the Better Regulation Executive (BRE) and the Regulatory Policy Committee (RPC), DCMS has not produced a full Regulatory Impact Assessment. The sale of C4C does not meet the definition of a regulatory provision under the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 and is therefore outside the scope of the Better Regulation Framework’s impact assessment requirements. While not a requirement, following advice from the BRE and the RPC, DCMS has nevertheless prepared this document to set out the rationale for intervention driving the decision to pursue a change of ownership, and provide an assessment of the potential impacts. As impacts are heavily dependent on the choices that a new owner would take, this has been addressed through a qualitative rather than a quantitative analysis.

Summary of impact of a change of ownership

9. The broadcasting landscape has evolved radically, and is continuing to do so, with the growth of online streaming platforms, changing viewing habits and increased competition from well-funded global players. With the broadcasting sector continuing to evolve at pace, now is the right time to act to ensure the long-term sustainability of C4C and future-proof its economic and social contributions across the UK. The decision to privatise C4C could potentially have impacts on three main areas: C4C’s sustainability; the delivery of C4C’s remit, and the independent production sector.

10. A new owner could enable C4C to access and deploy additional capital — debt and/or equity — to facilitate increased investment and growth, accelerating C4C’s revenue diversification and improving the scope for revenue growth, increasing the scale and reach of C4C. This may include enabling C4C to compete more effectively — to accelerate its digital transition, supporting increased investment in technology and data analytics to create a platform to compete effectively with larger well-funded streaming businesses. A new owner could also enable C4C to invest in content production and ownership, through organic or acquisition-led expansion and may also be able to pursue higher budget projects. There may be scope to grow revenues through accelerating C4C’s international expansion, for example via new international distribution, new platform deals or strategic partnerships to access new markets and audiences. Depending on the buyer, there may also be scope to unlock efficiency savings which could come from shared Board/oversight, central and back-office functions; from shared technology investment; from accessing parent-company digital platforms; from new content deals with parent company and/or third parties.

11. C4C is, and will remain, a public service broadcaster, just like other successful public service broadcasters — ITV, STV, and Channel 5 — that are already privately owned. C4C delivers its remit through commercially successful content that appeals, in particular, to young and valuable audiences, and underpins its distinctive brand. A more profitable, resilient and growing C4C, facilitated by access to capital, could make greater and more sustainable public value contributions, especially when underpinned by a continuing public service broadcasting remit. C4C currently delivers its remit, including its focus on diversity and creativity, in ways that are generally commercial and support its brand and audience attraction strategy. As such, buyers are likely to see value in making decisions that nurture and support effective delivery of this remit, although it is not possible to predict how it would be delivered by any particular buyer.

12. Consistent with the founding purpose of C4C when it was established in 1982, the independent production sector is now flourishing, with sector revenues increasing greatly over the last two decades. Meanwhile, the contribution of PSB commissions to sector revenues has been falling. The independent production sector has expressed concern at the removal of C4C’s publisher-broadcaster restriction, with the potential for content spending to be lost to an in-house production arm under a new owner. However, given the strong demand for independent production, and the now relatively small proportion of total spend represented by C4C commissions, the government believes that the independent production sector can continue to thrive without the publisher-broadcaster restriction in place for C4C. Additionally, the Terms of Trade will be preserved, which ensure that independent producers retain the underlying copyright and intellectual property rights to their content, which they can sell internationally. Also, a new owner with improved access to capital and deeper pockets may facilitate the growth of C4C, increasing investment in independent productions in absolute terms. Removing the restriction will also provide C4C with an opportunity to diversify its income streams which are currently heavily dependent on advertising revenues.

13. A fuller analysis of these impacts is outlined in the Impact of a change in ownership section below.

Rationale for intervention

C4C’s current situation

14. C4C has continued to perform successfully over recent years despite the increasingly competitive market backdrop. It generated £934 million in revenue in 2020, only 5% down on 2019[footnote 1] despite the challenges presented by COVID-19. It is expected to report another strong performance for 2021 having previously suggested revenues were set to grow by 19%, taking them past £1 billion.[footnote 2] C4C reported a financial surplus of £74 million in 2020 and ended the year with cash reserves of £201 million.[footnote 3] However, the market has changed radically and is continuing to evolve rapidly and C4C’s recent strong financial performance does not guarantee its sustainability in the medium to long term due to the many changes facing participants in the sector, set out below.

Evolution of the broadcasting sector

15. The broadcasting landscape has evolved radically, and is continuing to do so, with the growth of online streaming platforms, changing viewing habits and increased competition from well-funded global players. Whilst all broadcasters are having to respond to these changes, C4C is more constrained than other linear TV broadcasters as a result of its current ownership and operating model. As a publicly owned statutory corporation it has more restricted access to capital than private-sector organisations would do to respond to the changes in the landscape. The publisher-broadcaster restriction gives it limited ability to diversify its income streams through IP ownership to mitigate the impact of a decline in linear TV advertising revenue. With the broadcasting sector continuing to evolve at pace, now is the right time to examine options to ensure the long-term sustainability of C4C and future-proof its economic and social contributions across the UK.

16. The government is committed to continuing the success and sustainability of C4C, and all public service broadcasters (PSBs), to ensure audiences can continue to enjoy a wide range of high-quality programmes. However, C4C, like all PSBs, is having to respond to changes in the sector, with changing consumer habits across all ages, but in particular across young audiences, and ever-increasing content budgets following the entrance of global players into the UK and a wave of consolidation across the sector resulting in larger competitors with deeper pockets. These changes call into question whether C4C’s current ownership and operating model gives it the best opportunity to continue to deliver for UK audiences for the long term.

17. Ofcom recently published its recommendations to the government on the future of public service media (PSM) and concluded that rapid change in the broadcasting industry is making it harder for PSBs, whether publicly or privately owned, to compete for audiences and maintain their current offer. Respondents to Ofcom’s consultation broadly agreed that the PSM system needs to be updated urgently to ensure that it is financially sustainable for the future.

1. Changing viewing habits and video-on-demand growth

18. Changes in viewing habits, driven by advances in technology, represent both challenges and new opportunities for PSBs to innovate following a marked shift in the way that people consume TV over the last decade. Audiences are increasingly likely to consume content on non-linear platforms such as video-on-demand (VoD) services, and are doing so on non-traditional ‘second-screens’ with just under half (47%) of all adults who go online now consider online services to be their main way of watching TV and films, rising to around two-thirds (64%) among 18-24 year-olds.[footnote 4]

19. C4C’s share of linear TV audiences has remained robust, with a main channel viewing share of 5.9% and portfolio viewing share of 10.1% in 2020,[footnote 5] only slightly down on its audience share in 2010. However, as choice for consumers continues to grow, PSBs are experiencing a diminishing share of total video viewing. The emergence of subscription video-on-demand (SVoD) services and the rise of other digital, video sharing platforms such as YouTube is drawing audiences away from the PSB ecosystem. Whilst overall daily audio-video viewing is increasing, rising from 4 hours 49 minutes in 2017 to 5 hours 40 minutes in 2020, broadcast TV’s share of total viewing fell from 74% in 2017 (3 hours 33 minutes) to 61% in 2020 (3 hours 27 minutes), whilst SVoDs (such as Netflix and Disney+) share of total video increased from 6% in 2017 (18 minutes) to 19% in 2020 (1 hour 5 minutes).[footnote 6] It is therefore crucial that C4C is able to adapt and differentiate itself to retain its audience reach against a backdrop of declining linear TV viewing.

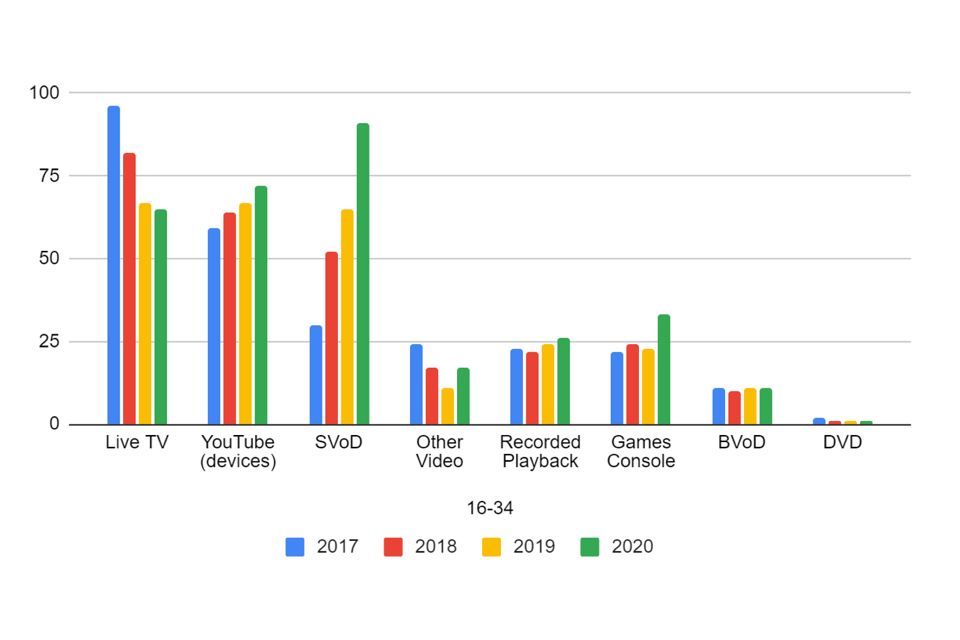

20. C4C attracts a large share of viewing amongst 16-34-year-olds, achieving a portfolio viewing share of 15.7% in 2020, 55% higher than its corresponding all-audience share of 10.1%.[footnote 7] Young audiences in particular are turning to alternative platforms to access content with 16-34 year olds watching 65 minutes of live TV per day in 2020, down from 96 minutes in 2017 (Figure 1). Meanwhile, SVoD viewing tripled in that time with 16-34 year olds watching 91 minutes of SVoD content per day in 2020, up from 30 minutes in 2017. They also watched an average of 72 minutes of YouTube each day in 2020, up from 59 minutes in 2017.[footnote 8] In order to retain this key audience, it is therefore essential that C4C accelerates its transformation into a hybrid broadcaster with both linear and VoD offerings across multiple platforms, a transition that could require significant investment and which is made more difficult by C4C’s existing ownership model and lack of access to capital.

Figure 1: Average daily viewing minutes by device, 16-34 year olds[footnote 9]

21. The marked shift in viewing habits from live TV broadcasting to SVoD has been exacerbated by the rapid penetration of the UK market by global competitors with deep pockets such as Netflix and Amazon. In Q2 2021, 16.8 million UK households subscribed to Netflix, 12.5 million UK households subscribed to Amazon Prime Video and 4.8 million UK households subscribed to Disney+.[footnote 10] These SVoD platforms boast larger content libraries than broadcaster video-on-demand (BVoD) services (such as BBC iPlayer and All4). As of April 2021, Amazon Prime Video had over 41,000 hours of content, and Netflix had over 38,000 hours of content; whilst the PSB’s BVoD services combined held nearly 37,000 hours of content, with All4, C4C’s on demand service, offering just over 15,000 hours.[footnote 11] While All4 continues to grow, receiving 1.25 billion streaming views in 2020, up 26% year-on-year, the well-funded SVoD services experienced even faster growth, with Amazon Prime receiving 1.82 billion views, up 118% year-on-year and Netflix receiving 15.5 billion streams in 2020, up 89% year-on-year.[footnote 12] With the transition to digital streaming expected to continue, it is essential that C4C has the financial firepower and other strategic support to continue to develop its strong VoD offer. Private-sector ownership that provides C4C with access to capital could support and accelerate investment in C4C’s digital transition to grow its reach and appeal to audiences.

2. Rising production costs

22. While an increasingly global broadcasting market contributes to the success of the UK’s production ecosystem and delivers more choice for audiences, in an era of rising production costs and competition, PSBs, including C4C, cannot afford to stand still if they aspire to retain their audience reach. Global SVoD players have experienced rapid growth and achieved significant market penetration. A number of sector mergers such as the recently announced WarnerMedia and Discovery merger, have created global players with significant financial and operational resources compared to UK PSBs, further driving up content costs and viewer acquisition costs across the sector.

23. These rising production costs are reflected across a number of genres, including high-end dramas where the average spend per hour on purely domestic productions has remained under £2 million per hour. The budget for shows with international investment is now almost £6 million per hour — with the gap set to widen.[footnote 13] Total PSB content spend on the production of original content was just under £2.1 billion in 2020, whilst Netflix alone spent $11.8 billion (£9.2 billion) on content globally in 2020,[footnote 14] with much of that content available to audiences on its UK platform. These growing content budgets across VoD platforms make it increasingly difficult for domestic players without access to significant capital to support strategic investment to compete. Under private ownership, with improved access to capital, C4C would have greater ability to increase its investment in content to remain competitive and maintain, or even expand, its audience reach, without any incremental risk associated with this investment impacting the public finances.

3. Switch to digital advertising

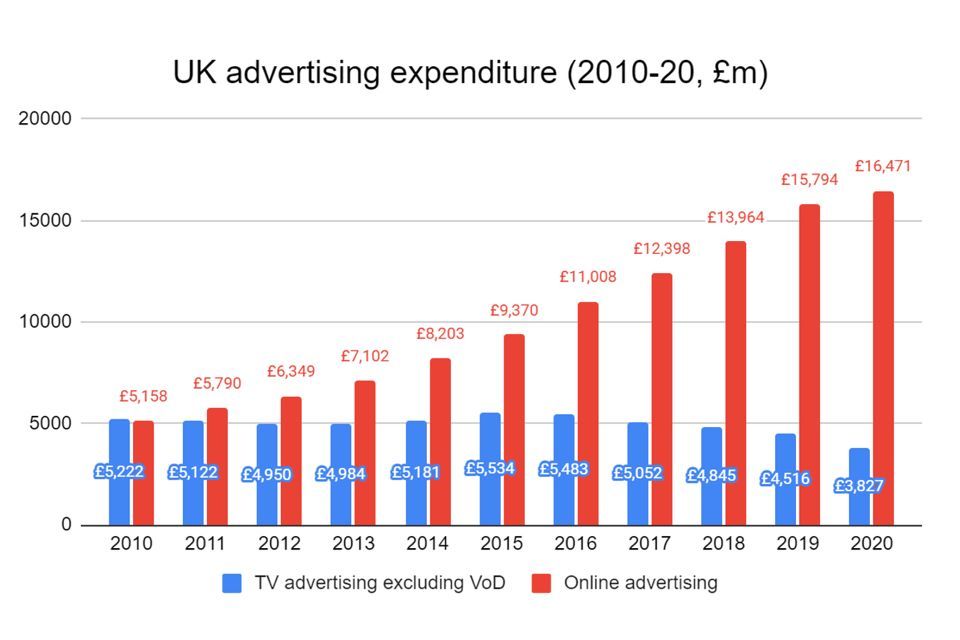

24. Digital advertising growth has accelerated over the past five years (Figure 2) with UK online advertising revenues increasing from £9.4bn in 2015 to £16.5bn in 2020. Meanwhile, linear TV advertising revenues have fallen from £5.5bn in 2015 to £3.8bn in 2020,[footnote 15] with the pace of decline in linear advertising likely to continue. VoD advertising growth is forecast at 8.6% in 2022, well above total TV advertising growth, which is forecast at 0.6% in 2022.[footnote 16]

Figure 2: UK TV and online advertising revenues[footnote 17]

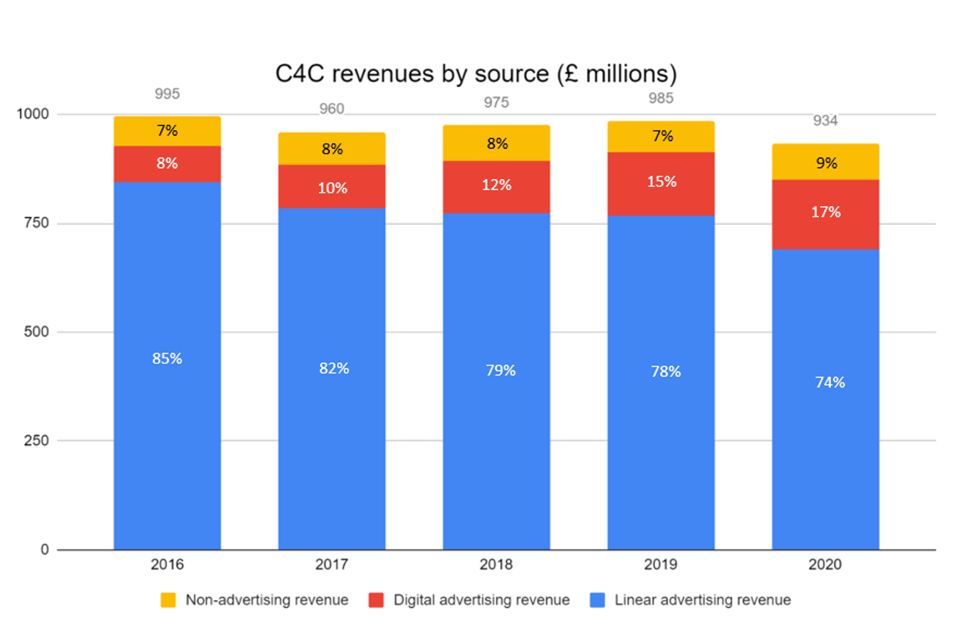

25. As of 2020, 74% of C4C’s revenue came from linear TV advertising, with 17% of its revenue from digital advertising (Figure 3). These revenue streams are cyclical in nature and in the case of linear TV advertising, are also in structural decline. Online advertising has offset some of the 18% decline in C4C’s linear advertising revenue over the period 2016-2020, but C4C still faced an 8% decline in overall advertising revenue before adjusting for inflation.[footnote 18] C4C’s digital viewing grew 30% in 2020,[footnote 19] its digital advertising revenue growth was 11%,[footnote 20] implying that there is further opportunity to grow digital advertising revenue and reduce C4C’s reliance on linear advertising. C4C announced its Future4 Strategy in 2020, aimed at accelerating its digital growth and driving both online viewing and new revenues. Specifically, the five-year strategy targets doubling All4 viewing by 2025, digital advertising to be at least 30% of total revenue by 2025, and non-advertising revenue to be at least 10% of total revenue by 2025. C4C’s ambitions to diversify away from linear advertising could be significantly accelerated under private ownership with improved access to capital and the removal of the publisher-broadcaster restriction, by providing C4C with the option and the associated capital needed to develop an in-house production capability.

Figure 3: C4C revenues by source[footnote 21]

4. Revenue diversification

26. C4C’s current reliance on advertising revenues and on linear advertising revenue in particular presents a risk it will face challenges to continuing to deliver the same high quality content in the future without further intervention. Whilst C4C could arguably reduce content spend to manage any short term revenue decline, as they did when preemptively cutting content spend by £138 million in 2020 in response to COVID-19,[footnote 22] this is not a credible long term solution without risking losing audience share and/or the quality of content being negatively impacted. Enders Analysis described C4C cutting content spending by 21%, as ‘in no way sustainable given the explosion in programming spends of the streaming services.’[footnote 23]

27. Investing in producing and owning content has been used by most broadcasters as a key way to reduce reliance on advertising revenue. Unlike other broadcasters, C4C’s publisher-broadcaster status prohibits it from being involved in the making of programmes to be broadcast as part of the C4C service without first seeking regulatory approval. This publisher-broadcaster restriction largely precludes it from using intellectual property ownership as a form of revenue diversification.

28. Both BBC and ITV have their own production division, with ITV Studios accounting for 42% of ITV Group’s revenue in 2020[footnote 24] and BBC Studios accounting for 25% of the BBC’s total income in 2020/21.[footnote 25] ITV Studios is the largest commercial producer in the UK with a combined content library of over 46,000 hours. It achieved total production and distribution revenue of almost £1.4 billion in 2020 despite production delays caused by COVID-19.[footnote 26] Advertising revenue accounted for more than 90% of C4C’s revenue in 2020. Removing C4C’s publisher-broadcaster restriction would create a level playing field for C4C, allowing it the ability to establish its own production division, should it wish to, facilitating a new revenue stream, reducing reliance on the linear TV advertising market.

5. Access to capital

29. Under public ownership, C4C has limited access to debt financing and no ability to raise equity capital by issuing shares to fund investment. C4C’s reserves and other financial resources are relatively low when compared to the content budgets and financial resources of global competitors. For instance, Netflix pledged to invest $17 billion on content in 2021.[footnote 27] Whilst the government is not proposing C4C needs to look to become Netflix, we recognise the ability of large global media and streaming groups to deploy investment at such scale has radically changed the markets in which C4C operates. To ensure C4C’s long-term sustainability in the face of competition for content, talent and audiences from well-funded global organisations such as Amazon, Netflix and YouTube, it is the government’s view that C4C requires greater access to capital to innovate and adapt more rapidly to respond to changing market conditions, and needs the ability to be more agile in its investment decisions to enable it to benefit from potential strategic partnerships, expansion opportunities and technological advancements.

30. To date, Parliament has restricted C4C’s borrowing to £200 million. Given it has no shares under its existing ownership model, C4C does not have the option to raise capital by issuing equity to third party investors. As a public corporation, C4C’s borrowing is accounted for as public sector borrowing and scores against total public sector net debt. New ownership would afford C4C the opportunity to access capital at scale and reap the associated benefits without increasing UK national debt.

Options considered

31. DCMS considered a wide range of different ownership and operating model options, including working with the C4C management team to examine the scope to address the market changes C4C is experiencing, and is likely to continue to experience in the future, under continuing public ownership.

32. There are two broad routes for expanding C4C’s access to capital without a change in ownership. We could explore raising C4C’s borrowing limit from the current £200 million via secondary legislation. Raising C4C’s borrowing limit would expand its ability to raise debt to invest in generating additional revenue to support long term sustainability (for example funding investment in technology and/or in-house production). C4C’s borrowing counts towards public sector net debt and, to date, C4C has only sought to use up to £75 million of its existing limit. C4C does not currently generate enough cash flow to service significant levels of additional debt, so any significant borrowing undertaken by C4C on a standalone basis could require a short term reduction in operational expenditure (potentially including content spend) to fund. In the event C4C could not service and/or repay any debt, the ultimate downside risk would rest with the government.

33. Alternatively, or in addition, we could allow C4C to establish a commercial subsidiary, joint venture, or other investment fund. This could create a means for C4C to access equity investment as well as debt financing, for example to support additional investment in content. There may be a range of ways to set up such a commercial structure and it could be a joint venture with other investors or strategic partners. In all cases, the extent of C4C control of the subsidiary, joint venture or fund would be critical to determining how much it could contribute to diversifying C4C’s revenues and safeguarding its sustainability. There would be a very high likelihood that any entity controlled by C4C would come onto the government’s balance sheet, together with any associated debt. In practice, the issues associated with raising C4C’s borrowing limit could therefore also apply and it is not clear there is an easy route to create a structure that would not impact on the public finances.

34. Given the challenges described above of increasing C4C’s access to capital under public ownership, a number of approaches to introducing private sector ownership and investment were also considered. This could be implemented via the sale of either a minority, majority or 100% interest in C4C. A 100% sale was concluded to be the best approach to meet policy objectives in a timely and value for money manner. This approach has a number of benefits including leaving no residual downside exposure for the taxpayer, and imposing no requirements for any new owner to agree ongoing shareholder arrangements with the government. The government maintaining a shareholding in C4C alongside a new owner could raise a range of additional complications including requirements to match new planned investment by that new owner in order to avoid dilution and how to manage that ongoing interest without the government becoming involved in the day-to-day affairs of C4C.

35. To improve C4C’s ability to diversify its revenue, the publisher-broadcaster restriction was also reviewed. The publisher-broadcaster restriction constrains C4C’s ability to achieve meaningful revenue diversification, noting that diversifying into content production and ownership has been a key strategy adopted by most broadcasters. The government concluded the best option is to rescind the publisher-broadcaster restriction and set C4C’s independent production quota in line with other PSBs. This will enable C4C to develop in-house production capability and own more IP, therefore enabling it to diversify its income meaningfully away from linear TV advertising. A weakening of the publisher-broadcaster restriction was also examined. Whilst this improves the scope for revenue diversification, it does not allow C4C the same degree of flexibility in how it can benefit from IP ownership as rescinding the publisher-broadcaster restriction would, and therefore provides for less scope for meaningful revenue diversification to support long sustainability and success. It would also leave C4C at a competitive disadvantage to other commercial broadcasters. Given the independent production sector is flourishing and less dependent on PSB commissions, on balance, the government considers rescinding the publisher-broadcaster restriction to be the best approach.

Impact of a change of ownership

36. The government believes that moving C4C into private ownership is the best approach to allow it to address challenges and to secure its long-term sustainability. It would enable C4C the improved access to capital that it needs and, when accompanied by the removal of the publisher broadcaster restriction, would enable it to make content and diversify its income streams without the potentially material increase in risk for the taxpayer and public sector finances associated with this happening under public ownership.

Impact on C4C sustainability

37. Under private ownership, C4C is expected to benefit from increased access to investment and growth, accelerated revenue diversification and an increased reach. This could include C4C accelerating its digital transition, whereby increased investment in technology and data analytics could create a platform that competes even more effectively with the larger well-funded streaming services. With greater access to capital, C4C may also be able to pursue higher budget projects and accelerate its international expansion.

38. By enabling C4C to invest in IP ownership through the removal of the publisher broadcaster restriction, this could facilitate greater revenue diversification, and hence increase resilience. It could enable C4C to compete and champion British content globally; Claire Enders has highlighted the ‘huge impetus on ownership of IP, which is manifesting in the rising share prices of companies that exploit it successfully in digital at scale.’[footnote 28] Maintaining a meaningful level of IP ownership will require significant access to capital and investment over time, with Mark Oliver suggesting that ‘if [C4C] wants to do anything significant, it needs more capital’[footnote 29] and this could be achieved under private ownership.

39. If C4C is acquired by an existing media company or an investor that owns other media businesses, there may also be scope to benefit from efficiencies without impacting on commissioning strategies. Potential efficiency savings may come from shared Board/oversight, central and back-office functions; from shared technology investment; from accessing parent-company digital platforms; from new content deals with parent company and/or third parties. This could translate into more spend to deploy into content and technology. There will also be scope to grow revenues, for example via new international distribution, new platform deals or strategic partnerships to access new markets and audiences. New lines of business, increased scope for investment and new strategic opportunities would also bring new opportunities for C4C’s employees, providing more development opportunities and potentially enabling C4C to further broaden its skills and training offer to existing and new employees.

40. These new opportunities for C4C under private ownership to expand its access to capital, grow and diversify its revenue base, access new markets and achieve potential efficiency savings will allow it to compete more effectively for talent, content and audiences with well-funded global players than it can under its existing ownership and operating model. As such, C4C will be better positioned to adapt to changes in the dynamic broadcasting market, which is likely to increase its long term sustainability.

Impact on remit delivery

41. C4C is, and will remain, a public service broadcaster, just like other successful public service broadcasters — ITV, STV and Channel 5 — that are already privately-owned. C4C delivers its remit through commercially successful content that appeals to young and valuable audiences, and underpins its distinctive brand.

42. The government therefore does not believe that the delivery of the public service remit is at odds with a profit-driven model, nor that a private owner would seek to make C4C a less trusted broadcaster with reduced public awareness. C4C’s distinctive public contribution and social value, informed in part by its remit, is fundamental to its brand and market positioning. The government expects C4C’s distinctiveness to be a large part of what makes it attractive to potential buyers. Supporting this with ongoing commitments through C4C’s remit and licence, and as part of the sale process, should see C4C’s public contribution continue to be nurtured and developed under new ownership. It is not just about protecting the downside; a more profitable and growing C4C, facilitated by greater access to capital, could make greater public value contributions, especially when underpinned by a continuing public service broadcasting remit.

43. C4C’s remit was extended in 2010, adding requirements including investment in film-making, skills and talent development. This is monitored by Ofcom through annual performance reporting. To date, C4C has operationalised the delivery of outcomes set out in its remit to the benefit of its brand and audience attraction strategy, creating a successful commercial model. This includes the risk-taking and alternative content it shows, and the process that goes into creating its content, including its role in supporting skills and talent in the creative economy. Whilst it is difficult to predict the impact of removing this extended remit requirement, we would expect buyers to see the value in making decisions that continue to deliver outcomes to the benefit of its brand and audience attraction strategy. Privately owned networks including Sky, A+E Networks UK, Discovery UK and Channel 5 are all signatories to the ScreenSkills Unscripted TV Skills Fund, suggesting that investment in training and skills is not limited to publicly owned broadcasters.[footnote 30] We also expect that Film4’s distinctive brand, and track record of delivering successful Academy Award-winning films would be seen as an asset by buyers.

44. The precise impact of a change of C4C’s ownership on diversity and inclusion, both on and off screen, will ultimately be dependent on its strategy under private ownership. However the government considers that C4C’s ability to speak to a diverse range of viewers and its distinctively different content is a central facet of its brand. There is both cultural and commercial value in this brand which a potential buyer would likely want to nurture and develop. A sustainable C4C is likely to be the best means to ensure the needs of the communities it serves continue to be met for years to come. The government will mitigate any potential risks to audiences through retaining C4C’s obligation to appeal to a culturally diverse society, accountable to the independent regulator, Ofcom.

45. In terms of potential risks to off-screen diversity, we understand that C4C has an extensive network of relationships with new, often untested talent which has, in turn, afforded it a certain creative energy and distinctiveness. Some stakeholders have expressed concerns that removing the publisher-broadcaster restriction will, over time, reduce the overall number of external commissioning opportunities, including for minority cultural practitioners in its value chain, with knock-on consequences for whose stories ultimately get told on TV and how. There is, however, clear demand for the types of differentiated content that C4C has become known for - programming that says new things, in new ways. We do not therefore consider that a new owner would make sweeping changes to C4C’s content strategy in ways that would undermine the channel’s distinctive positioning. C4C’s network of relationships with minority cultural practitioners, who have otherwise been forced to operate at the margins of the creative industries, could be a valuable asset to a potential buyer. Again, this is not just about downside protection: a bigger, more well-funded, C4C could increase the opportunities available, both in terms of the number and value of external commissions, and the number of internal jobs as C4C begins to grow its own in-house production capabilities.

Impact on production

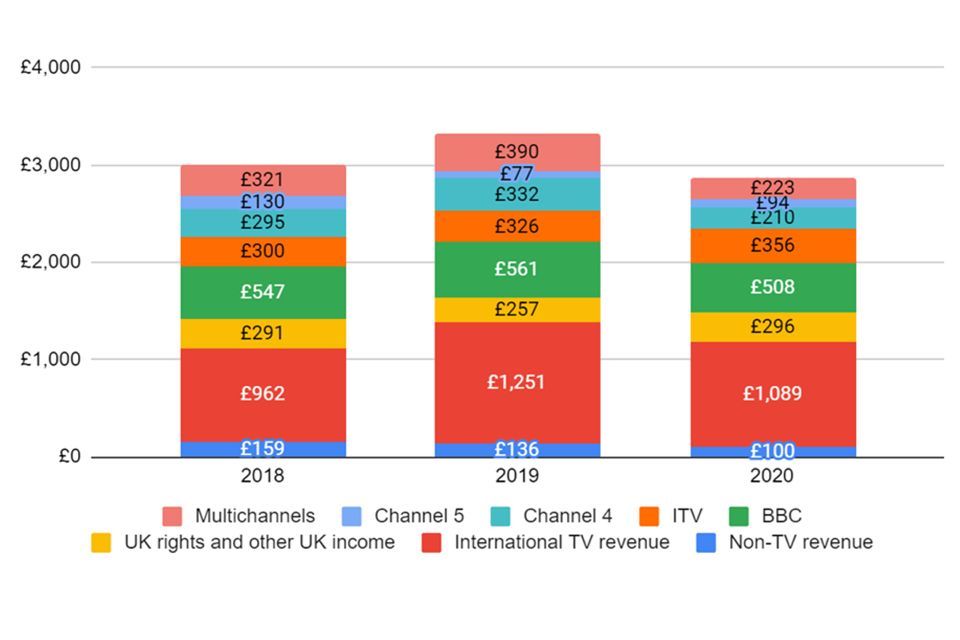

46. The independent production sector is flourishing. Sector revenues have grown from £500 million in 1995,[footnote 31] reaching £2.9 billion in 2020 with revenues from international commissions exceeding £1 billion. [footnote 32] Meanwhile between 2010 and 2020, the contribution of PSB commissions to sector revenue fell from 58% to 41%.[footnote 33] Of the £2.9 billion sector revenues in 2020, PSBs accounted for £1.2 billion, with C4C spending £210 million on external commissions, accounting for 7% of total independent production sector revenue, less than the BBC’s £508 million and ITV’s £356 million; though both the BBC and ITV have their own in-house production arms.[footnote 34] Meanwhile, Netflix spent £779 million on UK original productions.[footnote 35] Given the strong demand for independent production, and the now relatively small proportion of total spend represented by C4C commissions (Figure 4) the government believes that the independent production sector can continue to thrive without the publisher-broadcaster restriction, particularly as the Terms of Trade will be preserved, which ensure that independent producers retain the underlying copyright and intellectual property rights to their content, which they can sell internationally.

Figure 4: Total production sector revenues by source

47. Whilst the independent production sector has expressed concern at the removal of the publisher-broadcaster restriction, the government believes that in the long run the UK production ecosystem will benefit from a more sustainable C4C. Depending on its future strategic direction, a more diversified, growing C4C with improved access to capital has the potential to increase investment in independent productions in absolute terms, with those that continue to receive investment from C4C potentially seeing an increase in average revenue from C4C commissions in the future.

48. PACT have posited that if C4C were privatised and the publisher-broadcaster restriction removed, an estimated £80 million of content spending would be lost to an in-house production arm in the first year, with the cumulative impact estimated to reach c.£400 million after three years, as further programmes are brought in-house.[footnote 36] However, the government notes that Channel 5’s overall content budget increased following its acquisition by Viacom in 2014, with first-run spending up by an average of 7% per year between 2014 and 2018.[footnote 37] As stated above, C4C with improved access to capital under private ownership and greater scope to grow and diversify revenues should be able to increase its absolute investment in content over time, and any move towards in-house production is likely to take time to develop given commissioning spend is allocated multiple years ahead, enabling mitigating action to be explored if necessary.

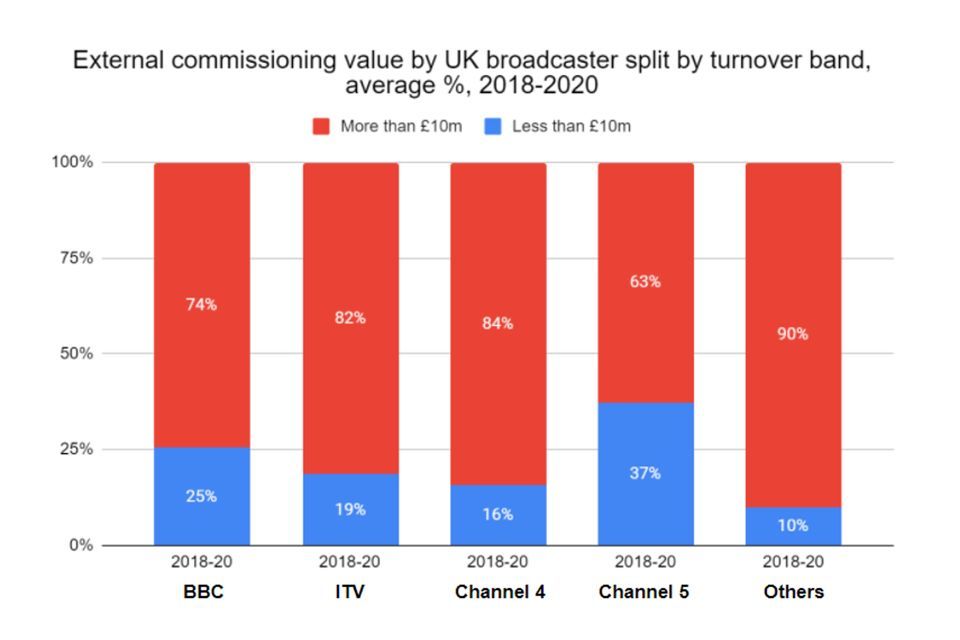

49. The government expects the buyer of C4C will recognise and value the strong local relationships C4C has with the independent production sector, and therefore is likely to wish to maintain and nurture these as a key driver of growth and differentiation. EY analysis, commissioned by C4C, suggests that ending the publisher-broadcaster model may result in a reduction in revenues from primary commissions for small and medium producers by up to 16%.[footnote 38] The government disagrees with this assessment in terms of investment in SMEs - only 16% of C4C’s average external commissioning spend between 2018 and 2020 was with producers with turnover up to £10m (Figure 5), less than the BBC, ITV and Channel 5,[footnote 39] suggesting that private ownership does not necessarily lead to decreased investment in SME companies. There may be some individual firms that lose out under private ownership if C4C narrows the pool of producers it works with, but those continuing to receive investment may benefit if C4C increases its investment in absolute terms.

Figure 5: External commissioning value by UK broadcaster split by turnover band[footnote 40]

50. Some concern has been raised that a C4C under private ownership could have less of an incentive to continue to invest in the nations and regions. We do not believe this will be the case. Taking the production sector as a whole, both ITV and C4C significantly exceed their regional production spend quota of 35%. Over the last 10 years, an average of 45.2% of ITV’s spend was outside M25, compared with 42.9% from C4C, suggesting private ownership does not lead to reduced spend outside London. Though it is on an improving path, C4C currently spends less on commissions in Northern England as a percentage of its total production spend, only 19.3% in 2020, compared with 22.9% for the PSB sector, and significantly behind privately owned ITV’s 30.4%. At the same time, Channel 5 has significantly increased spend on qualifying indies outside London since Viacom bought it, demonstrating potential for increased investment following a change in ownership.[footnote 41]

51. Taking a broader view, demand for the independent production sector is predicted to remain strong, and many existing producers find they are capacity - not demand - constrained (with per-hour prices for key genres like drama and natural history rising, and high budgets for programmes with international investment). Ultimately, the precise impact for the independent production sector will be determined by any new owner’s strategy for the business, but we would expect any impacts to be gradual, which would allow for mitigating actions to be implemented in parallel if necessary.

52. Whilst there might be some adjustments in the way C4C commissions work, it is our considered assessment that the benefits to C4C and the wider creative economy of removing the publisher-broadcaster restriction, coupled with the opportunities for further investment in the sector that a private owner able to provide increased access to capital would bring, are likely to outweigh the costs of allowing C4C scope to establish an in-house production arm.

Monitoring and evaluation plan

53. The economic and social impacts of the C4C sale are likely to be primarily driven by the decisions taken by the new owner and C4C management team. The government will continue to monitor the performance of the PSB system as a whole, including C4C, to ensure the system continues to deliver for the British people and on its public service remit.

54. In addition, Ofcom will monitor the performance of C4C through its reporting requirements in relation to the PSB system. Under sections 264 and 264A of the 2003 Act, Ofcom must report regularly (at least every 5 years) as to the achievement of the PSB remit in the UK and make such recommendations as it considers appropriate. It also has powers to consider the contribution of individual PSBs, under s.270 (for licensed PSBs).

Conclusion

55. Despite C4C’s recent strong financial performance, the ongoing challenges presented by the radical changes to the broadcasting landscape as it has evolved, and will continue to evolve, are likely to make it increasingly difficult for C4C to remain competitive over the long term given the constraints of its existing ownership and operating model. Under private ownership it could access and deploy additional capital, increasing investment and growing its revenue, whilst removing the publisher-broadcaster restriction will enable C4C to diversify its income and decrease its dependence on linear advertising. These changes will help to ensure its long term economic, social and cultural contributions to the UK.

-

C4C Annual Report 2020, 2020. ↩

-

C4C, Channel 4 response to DCMS consultation on a potential change of ownership of Channel Four Television Corporation, 2021. ↩

-

C4C, C4C Annual Report 2020, 2020. ↩

-

Ofcom, Media Nations 2021, 2021. ↩

-

C4C, C4C Annual Report 2020, 2020. ↩

-

Ofcom, Media Nations 2021, 2021. ↩

-

C4C, C4C Annual Report 2020, 2020. ↩

-

Ofcom, Media Nations 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Ofcom Media Nations 2021, 2021. ↩

-

BARB, BARB Establishment Survey Q2 2021, 2021 ↩

-

Ofcom Media Nations 2021, analysis of Ampere Analysis Analytics – SVoD Data, 2021 ↩

-

Ofcom Media Nations: UK 2021, analysis of data from different sources ↩

-

British Screen Forum: High-end Television Drama Investment: An Update, 2021. ↩

-

Ofcom Media Nations 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Ofcom Media Nations 2021, analysis of AA/WARC Expenditure Report and IAB UK/PwC Digital Adspend Study, 2021. ↩

-

AA/WARC Expenditure Report 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Ofcom Media Nations 2021, 2021. ↩

-

House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee, The future of Channel 4, 2021. ↩

-

C4C, Supplementary written evidence from C4C to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee: The future of C4C, 2021. ↩

-

C4C, C4C Annual Report 2020, 2020 ↩

-

C4C, C4C Annual Report 2020, 2020 ↩

-

C4C, C4C Annual Report 2020, 2020 ↩

-

Enders Analysis, Written evidence from Enders Analysis to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee: The future of C4C, 2021 ↩

-

ITV, ITV PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2020, 2020. ↩

-

BBC Group, BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2020/21, 2021. ↩

-

ITV, ITV PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2020, 2020. ↩

-

Netflix, Netflix Q1 2021 Quarterly Earnings, Letter to Shareholders, 2021. ↩

-

Claire Enders, Oral evidence from Claire Enders, Founder of Enders Analysis, to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee: The future of C4C, 2021. ↩

-

Mark Oliver, Oral evidence from Mark Oliver, Chair and Co-Founder, Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates, to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee: The future of C4C, 2021. ↩

-

ScreenSkills, Written evidence from ScreenSkills to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee: The future of Channel 4, 2021. ↩

-

Mediatique, TV production sector evolution and impact on PSBs, 2015 ↩

-

Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates/PACT UK, Television Census 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates/PACT UK, Television Census 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates/PACT UK, Television Census 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Ofcom Media Nations 2021, 2021. ↩

-

PACT, Written evidence from PACT to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee: The future of Channel 4, 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Ofcom Small Screen: Big Debate — a five-year review of Public Service Broadcasting (2014-18), 2020. ↩

-

EY, Assessing the impact of a change of ownership of Channel 4, 2021. ↩

-

Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates/PACT UK, Television Census 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Oliver & Ohlbaum Associates/PACT UK, Television Census 2021, 2021. ↩

-

Ofcom, Public Service Broadcasting Annual Report 2021, 2021. ↩